Abstract

Introduction

Studies have shown reduced antiviral responses in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination, but data on post-vaccination alloimmune responses and antiviral responses against the Delta (B.1.617.2) variant are limited.

Materials and methods

To address this issue, we conducted a prospective, multi-center study of 58 adult KTRs receiving mRNA-BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273 vaccines. We used multiple complementary non-invasive biomarkers for rejection monitoring including serum creatinine, proteinuria, donor-derived cell-free DNA, peripheral blood gene expression profile (PBGEP), urinary CXCL9 mRNA and de novo donor-specific antibodies (DSA). Secondary outcomes included development of anti-viral immune responses against the wild-type and Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2.

Results

At a median of 85 days, no KTRs developed de novo DSAs and only one patient developed acute rejection following recent conversion to belatacept, which was associated with increased creatinine and urinary CXCL9 levels. During follow-up, there were no significant changes in proteinuria, donor-derived cell-free DNA levels or PBGEP. 36% of KTRs in our cohort developed anti-wild-type spike antibodies, 75% and 55% of whom had neutralizing responses against wild-type and Delta variants respectively. A cellular response against wild-type S1, measured by interferon-γ-ELISpot assay, developed in 38% of KTRs. Cellular responses did not differ in KTRs with or without antibody responses.

Conclusions

SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in KTRs did not elicit a significant alloimmune response. About half of KTRs who develop anti-wild-type spike antibodies after two mRNA vaccine doses have neutralizing responses against the Delta variant. There was no association between anti-viral humoral and cellular responses.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, kidney transplant, vaccine, rejection, monitoring

Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory virus coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is associated with increased mortality in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) compared to non-transplant patients (1). Despite studies showing a blunted antibody response (2–4), SARS-CoV-2 vaccination has been associated with reduced incidence of COVID-19 and reduced case-fatality rate in KTRs (5–7). Reports of anti-viral humoral and cellular responses in KTRs following SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccination have been published (2–4, 8–10), but they were focused on Wild-type SARS-CoV-2 with very little data on antiviral responses against the Delta (B.1.617.2) variant (11), which accounts for most infections at this time in the United States (12).

Furthermore, data about the monitoring of alloimmune responses and graft function in KTRs following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination remain limited (13–16). Concerns about the use of mRNA vaccines in KTRs include their excessive activation of the immune system and their potential for triggering allograft rejection (17–19). The concern stems at least partially from that SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines have been shown to elicit a strong cytokine response in CD4+ T-cells from immunocompetent individuals, including IL-2 and TNF-α (20). Furthermore, kidney allograft rejection has been reported following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination (14). Assessment of alloimmune responses to these vaccines is crucial to provide guidance regarding the need for more frequent monitoring for rejection following vaccination in KTRs. Therefore, it is of paramount importance to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of allograft status by complementary methods and assess alloimmune responses following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in KTRs.

The aim of this study was to comprehensively monitor allograft status using several non-invasive additional tools beyond what is routinely done clinically and what has been done in other studies. We also characterized the alloimmune and anti-viral responses after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in KTRs, including antiviral responses against the Delta variant.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patient Recruitment

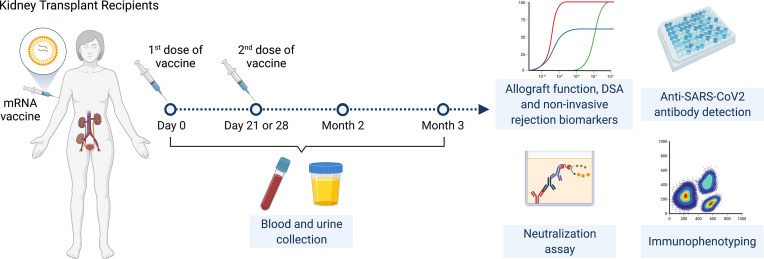

This is a prospective multicenter observational cohort study of the safety and efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines in adult KTRs ( Figure 1 ). Inclusion criteria were KTRs >3 months post-transplantation who were ≥18 years of age with stable allograft function (<20% variation in last two eGFR values at least one week apart) and no rejection in the prior six months. KTRs were enrolled consecutively by order of vaccination. Full exclusion criteria are listed in supplementary material and methods.

Figure 1.

Study design.

Enrolled KTRs received two doses of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines administered 28 days apart for the mRNA-1273 vaccine and 21 days apart for the BNT162b2 vaccine. Participants had a study visit at baseline (day 0, immediately prior to first vaccine dose) then had follow-up visits immediately prior to the second vaccine dose (day 21 or 28 depending on vaccine), at two months and at three months following initial vaccination. Baseline characteristics were reviewed at the initial visit and adverse events were reviewed at follow-up visits. Blood and urine samples were collected at all timepoints.

Study Approval

The study was approved by the institutional review board at Mass General Brigham (Protocol#: 2021P000043). All subjects signed written informed consent forms prior to inclusion in the study. The clinical and research activities being reported are in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and consistent with the Principles of the Declaration of Istanbul. Data are reported in accordance with the STROBE statement reporting guidelines.

Outcomes

The primary objective was non-invasive rejection detection using a combination of biomarkers including serum creatinine, urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR), de novo donor-specific antibodies (DSAs), donor-derived cell-free DNA (ddcfDNA), peripheral blood gene expression profile (PBGEP) and urinary CXCL9 mRNA. Secondary outcomes included 1) generation of anti- spike antibodies against wild-type and Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 (assessed by a Luminex-based multiplex assay and a surrogate virus neutralization test [SVNT]); 2) S1-specific cellular immunity against wild-type SARS-CoV-2 (assessed by an IFN-γ EliSPOT assay and immune phenotyping using flow cytometry), 3) development of any severe or grade 4 adverse events and 4) development of SARS-CoV-2 infection within three months of vaccination.

Sample Collection and Processing

Blood and urine samples were collected from KTRs at baseline, prior to the second vaccine dose, and at two- and three-months post-vaccination. Blood and urine samples were sent to the clinical lab (for serum creatinine and urine protein-to-creatinine ratio quantification), our research laboratories (for DSA, anti-spike antibody and cellular immune assays) and CareDx, Inc. (for ddcfDNA and PBGEP).

Serum and plasma were obtained from peripheral blood by centrifuging for 15 minutes at 2,500 RPM at room temperature then stored in cryogenic tubes at -80°C. PBMCs were isolated using SepMate™-50 tubes (Stemcell technologies) containing Lymphoprep™ solution (Stemcell technologies) then centrifuged at 1,200g for 10 minutes. The PBMC layer was then transferred to a new 50 mL conical tube and centrifuged at 300g for 8 minutes. The supernatant was discarded, and the pelleted cells were resuspended in 10ml of sterile PBS 1x then centrifuged again at 300g for 8 minutes. Pelleted cells were re-suspended in a solution of GemCell™ human serum (GeminiBio) with 10% of dimethyl sulfoxide (100μL for each 1 million PBMCs), aliquoted in cryogenic tubes then stored at -80°C for 1-3 days before being transferred to a liquid nitrogen freezer.

Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Assay

Circulating ddcfDNA levels were measured as per published AlloSure® protocol (CareDx, Inc., Brisbane, CA) (21, 22). Briefly, duplicate samples of venous blood were collected using Streck cell-free DNA BCT® tubes then shipped to CareDx, Inc. laboratories (Brisbane, CA), where plasma was separated by centrifugation then cell-free DNA was extracted using the circulating nucleic acid kit (Qiagen, cat no. 55114) following manufacturer’s instructions. Plasma ddcfDNA levels were measured using a next-generation sequencing assay utilizing 266 single nucleotide polymorphisms, which allows quantification of ddcfDNA without requiring genotyping of the donor or recipient. Results are reported as percentage of total circulating cell-free DNA. Percentages above 0.5-1.0% are associated with an increased risk of allograft rejection (22, 23). Fifty one out of fifty eight patients had Streck cell-free DNA BCT® tubes collected for ddcfDNA measurement.

Peripheral Blood Gene Expression Profile (PBGEP) Assay

PBGEP assay was performed and PBGEP score calculated as per AlloMAP protocol (CareDx, Inc., Brisbane, CA) (24). As described previously (24), peripheral blood was collected in PAXgene® RNA tubes then shipped to CareDx, Inc. laboratories (Brisbane, CA) where RNA was extracted using the QIASymphony PAXgene Blood RNA kit (Qiagen, Cat no. 762635) following manufacturer’s instructions. QIASymphony spectrophotometry system (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used to determine the concentration and purity of RNA. Quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was run in triplicates for purified RNA samples and the mean CT for each determined as described previously (25). The mean CT for the five candidate genes (DCAF12, MARCH8, FLT3, IL1R2, and PDCD1) derived from previous studies in heart transplantation (26), was normalized to six reference genes (24). A multivariate model that integrates reference-normalized expression of the five genes computes a PBGEP (AlloMAP-Kidney) score (range 0-20) to differentiate immune quiescence from rejection with higher scores associated with rejection. Median (IQR) scores of 12.43 (11.12-14.29) and 10.19 (7.64-12.09) were seen in patients with and without kidney allograft rejection respectively (24). Fifty-one out of fifty-eight patients had PAXgene® RNA tubes collected for PBGEP scoring.

Anti-Human Leukocyte Antigen Antibody Assays

Screening for anti-human leukocyte antigen (HLA) antibodies was performed at 3 months post-vaccination using mixed class I & II kit (One Lambda, catalog no. LSM12). Briefly, patient sera and negative control sera (One Lambda, catalog no. LS-NC) were added to HLA-coated beads and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. After washing, PE-conjugated goat anti-human IgG secondary antibody (One Lambda, catalog no. LS-AB2) was added then incubated for 30 minutes. The results were read using LABScan™ 100 (Luminex, Austin, TX) and analyzed using HLA Fusion™ software (One Lambda). A sample to negative control serum mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) ratio >3.5 was considered positive per our histocompatibility lab’s standards. Patients with a positive anti-HLA antibody screen at month 3 then had anti-HLA antibody class I and II testing using single-antigen beads (LABScreen™ Single Antigen Class I – Combi, catalog no. LS1A04 and Class II – Group 1, catalog no. LS2A01, One Lambda) with an identical protocol to determine which anti-HLA antibodies were present to determine if they were donor-specific. Baseline (pre-vaccination) sera were then tested to determine if DSAs had been present prior to vaccination or were de novo (defined as new DSAs with MFI >1,000). In patients with pre-existing DSAs, we also evaluated increases in the MFIs of pre-existing DSAs following vaccination, which we defined as a 50% increase in MFI from pre-vaccination baseline.

Urinary CXCL9 mRNA Measurement by CRISPR-Cas13 Platform

Urinary CXCL9 measurement was performed in 26 KTRs recruited at one of the transplant sites, where urine pellets had been processed prior to and following vaccination. Briefly, 45ml of urine were collected from patients then centrifuged at 2,000g for 30 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, the pellet was washed in 1ml of PBS and then centrifuged in a microcentrifuge tube at 10,000g for 5 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded and 200μL of RNAlater® (QIAGEN, cat no. 76163) were added and stored at -80°C. RNA was isolated using RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, catalog no. 55114) following manufacturer instructions. Recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) and Cas-13 reactions were performed in duplicates as previously described by our group (27). The reaction was read using SpectraMax iD3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA). Net relative fluorescent units (RFU) values were determined by subtraction from background values. A cut-off of 100 background-subtracted RFUs was considered positive.

Specific-Antibody Quantification and Neutralization Capacity

Total anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (IgM, IgA and IgG) against the spike protein trimer, S1 region, receptor-binding domain (RBD) region and nucleocapsid (NC) protein from baseline and month two after vaccination samples were measured using the Coronavirus Ig Total Human 11-Plex ProcartaPlex™ Panel (Invitrogen™, catalog no. EPX110-16000-901). Capture beads were added to each well and then controls and samples (in a 1:1,000 dilution) were added. The plate was incubated for 2 hours at room temperature, then washed and detection antibody was added to each well. After a 30-minute incubation at room temperature, the plate was read using MAGPIX system (Luminex, Austin, TX) and the data was analyzed using xPONENT software (Luminex, Austin, TX). As indicated by the manufacturer, a positive result was defined as a sample to low-control MFI ratio above 1.3. An indeterminate result was defined as an MFI ratio between 1.0 and 1.3, while a MFI ratio <1.0 was defined as a negative result.

In patients who had a positive or indeterminate anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody result, we evaluated the neutralizing function of antibodies against both wild-type and Delta (B.1.617.2) variant of SARS-CoV-2 using a surrogate virus neutralization test (GenScript cPass kit, catalog no. L00847-A). Patient sera (diluted 1:10) were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated recombinant SARS-CoV-2 RBD fragments (HRP-RBD) in a 1:1 ratio. The mix of sera and HRP-RBD (Delta RBD-HRP with L452R and T478K mutations, GenScript catalog no. Z03614-20) was added to each well of a capture plate pre-coated with human angiotensin converting enzyme 2 protein (ACE2) then incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes. Neutralizing antibodies form complexes with HRP-RBD that remain in the supernatant are removed with washing, while non-neutralizing antibodies-HRP-RBD complexes and unbound HRP-RBD bind to ACE2 and are captured on the plate. After washing, 3,3’,5,5’-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) solution was added, and the plate was incubated in the dark for 15 minutes at room temperature. Finally, a stop solution was added, and the plate was read at 450nm using SpectraMax iD3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA). The absorbance of the sample is inversely related to the concentration of neutralizing antibody. As indicated by the manufacturer, inhibition of ≥30% was considered a positive result. The concentration of neutralizing antibody was determined using a neutralizing antibody standard curve (GenScript, catalog no. A02087).

ELISpot for IFN-γ Quantification

IFN-γ ELISPOT was performed as described previously (28). Briefly, frozen PBMCs were thawed, washed and 0.5 million cells were added to ELISpotPLUS plates pre-coated with anti-IFN-γ antibodies (Mabtech, catalog no. 3420-4AST-P1-1). The cells were stimulated with SARS-CoV-2 peptides from the S1 region of the spike protein at a concentration of 2 μg/mL along with CD28-stimulating antibody at a concentration of 0.1 μg/mL for 48 hours in a humidified incubator (37°C with 5% of CO2). Monoclonal CD3-stimulating antibody was used as a positive control and unstimulated PBMCs were used as negative controls. The detection antibody (7-B6-1-Biotin) was then added and the plate and incubated for two hours at room temperature. Afterwards, Streptavidin-ALP and then its substrate solution (BCIP/NBT-plus) were added. The reaction was left to develop until distinct spots appeared, after which it was stopped by extensive washing with tap water. After air drying, the plate was read using KS ELISpot reader (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with software version KS ELISpot 4.9.16 (29). Results are reported as spots per 106 PBMCs. An increase of ≥32 spots per 106 PBMCs from baseline was defined as a positive result. The cut-off was determined as an increase of 3 standard deviations of the negative controls as was done in previous studies (13).

Immune Phenotyping With Flow Cytometry

Frozen PBMCs were thawed, and one million cells were added per well in a U-bottom 96 well plate and incubated for 4 hours in a humidified incubator (37°C, 5% CO2). After this incubation, the cells were transferred to a V-bottom 96 well plate for the staining. One plate was used for B-cell marker staining, and the other plate was used for T-cell markers staining. B-cell antibodies used were CD19 (PE, clone 4G7, BioLegend), IgM (BUV395, clone G20-127, BD Bioscience), IgD (PerCP/Cyanine5.5, clone IgD, BioLegend), IgG (FITC, clone G18-145, BD Bioscience), CD22 (BV421™, clone S-HCL-1, BioLegend), CD24 (APC/Cyanine7, clone SN3 A5-SH10, BioLegend), CD27 (APC, clone O323, BioLegend), CD138 (BUV737, clone MI15, BD Biosciences), CD3 (BV605™, clone OKT3, BioLegend), CD5 (BV711™, clone UCHT2, BioLegend), HLA-DR (BV650™, clone L243, BioLegend), CD274/PD-L1 (BV786, clone MIH1, BD Biosciences), CD279/PD-1 (Alexa Fluor®, clone EH12.2H7, BioLegend), CD25 (PE/Dazzle™ 594, clone M-A251, BioLegend) and CD38 (PE/Cyanine7, clone HIT2, BioLegend).

T-cell antibodies used were anti-CD8 (BUV737, clone SK1, BD Biosciences), CD4 (BUV395, clone SK3, BD Biosciences), CD3 (BV605™, clone OKT3, BioLegend), CD25 (PE, clone M-A251, BioLegend), CD185/CXCR5 (BV711™, clone J252D4, BioLegend) CD45RA (APC, clone HI100, BioLegend), CD279/PD-1 (Alexa Fluor®, clone EH12.2H7, BioLegend), HLA-DR (APC/Cyanine7, clone L243, BioLegend), CD197/CCR7 (PE/Dazzle™ 594, clone G043H7, BioLegend), CD196/CCR6 (PE/Cyanine7, clone G034E3, BioLegend), CD127 (PerCP/Cyanine5.5, clone A019D5, BioLegend) and CXCR3 (FITC, clone G025H7, BioLegend). Samples were read using BD LSRFortessa™ X-20 cell analyzer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and the data was analyzed using FlowJo 10 (FlowJo, Ashland, OR). The gating strategy can be found in Figures S1 and S2 .

Statistics

Continuous variables are presented as means ( ± standard deviation) or medians (with interquartile ranges) depending on normality of distribution. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. For continuous variables, differences between unpaired samples were assessed using an unpaired t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test depending on distribution. Differences between two paired samples were assessed using a paired t-test or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test as appropriate. Differences between paired samples at multiple follow-up timepoints were assessed using one-way repeated measures analysis of variance, Friedman test or mixed-effects model as appropriate. For tests that reached statistical significance, pairwise testing was performed to determine significant differences between the groups, using Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple pairwise comparisons. For categorical variables, differences in proportions were calculated using Pearson’s Chi squared test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. The odds of developing an outcome based on an exposure variable were expressed as an odds ratio. Multivariable logistic regression was used to adjust for potential confounding co-variates in determining the odds of developing outcomes based on an exposure variable. Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficient were calculated to evaluate correlations between continuous variables as appropriate. All tests used were two-sided and a two-sided α-level of 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. SPSS v24 (Chicago, IL) and GraphPad Prism v9.1.2 (San Diego, CA) were used for statistical analysis and creation of figures.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Fifty-eight KTRs were enrolled in the study. Baseline characteristics of KTRs are shown in Table 1 . Median age was 62 years, 41% were female, median time post-transplantation was 47 months (range 4-401) and 9% had DSAs at the time of vaccination ( Table S1 ). Fifty-six (97%) patients received the BNT162b2 vaccine. Patients were followed for a median of 85 days (IQR 81-88).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of kidney transplant recipients.

| Baseline characteristic | n = 58 |

|---|---|

| Age at enrollment (years), median (IQR) | 62 (51-70) |

| Time from transplantation (months), median (range) | 47 (4-401) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 24 (41) |

| Previous kidney transplant, n (%) | |

| None | 52 (90) |

| One | 4 (7) |

| Two | 2 (3) |

| Cause of ESKD, n (%) | |

| Glomerular disease | 21 (36) |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 10 (17) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 9 (16) |

| Genetic kidney disease | 5 (9) |

| Obstructive uropathy | 2 (3) |

| Lithium toxicity | 2 (3) |

| Other or unknown | 9 (16) |

| Pre-transplant RRT, n (%) | |

| None | 24 (41) |

| Hemodialysis | 28 (48) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 6 (10) |

| Donor source, n (%) | |

| Living related | 11 (19) |

| Living unrelated | 24 (41) |

| Deceased | 23 (40) |

| Cold ischemia time (hours), median (IQR) | 8.0 (1.0-14.0) |

| KDPI (%), median (IQR) | 46 (31-69) |

| HLA ABDR mismatches, median (IQR) | 3 (4-5) |

| Class I PRA (%), median (range) | 0 (0-69) |

| Class II PRA (%), median (range) | 0 (0-97) |

| Pre-transplant DSA, n (%) | 3 (5) |

| DSA at the time of vaccination, n (%) | 5 (9) |

| Induction immunosuppression, n (%) | _ |

| Anti-thymocyte globulin | 26 (45) |

| Basiliximab | 25 (43) |

| Data not available | 7 (12) |

| Maintenance immunosuppression, n (%) | _ |

| Calcineurin inhibitor | _ |

| Tacrolimus | 36 (62) |

| Trough level in ng/mL, median (IQR) | 5.9 (4.6-7.2) |

| mTOR inhibitor | _ |

| Everolimus | 5 (9) |

| Sirolimus | 4 (7) |

| Belatacept | 16 (28) |

| Mycophenolate | 45 (78) |

| Total daily dose in mg, median (IQR) | 1,000 (1,000-1,000) |

| Azathioprine | 5 (9) |

| Prednisone | 43 (74) |

| Total daily dose in mg, median (IQR) | 5 (5-5) |

| Rituximab (within 12 months) | 1 (2) |

| CMV serostatus, n (%) | |

| D+/R+ | 4 (7) |

| D+/R- | 11 (19) |

| D-/R+ | 10 (17) |

| D-/R- | 24 (41) |

| Not available | 9 (16) |

| EBV serostatus, n (%) | |

| D+/R+ | 39 (67) |

| D+/R- | 5 (9) |

| D-/R+ | 1 (2) |

| D-/R- | 1 (2) |

| Not available | 12 (21) |

| Delayed graft function, n (%) | 12 (24) |

| History of allograft rejection, n (%) | 14 (24) |

| Months since most recent rejection, median (IQR) | 37.7 (15.9-54.3) |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 1.22 (1.06-1.66) |

| Estimated GFR (ml/min/1.73 m2), median (IQR) | 57.0 (42.3-70.8) |

| Urine protein to creatinine ratio (g/g), median (IQR) | 0.13 (0.09-0.27) |

| Donor-derived cell free DNA (%), median (IQR) | 0.15 (0.00-0.24) |

| Previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, n (%) | 2 (3) |

| mRNA vaccine received, n (%) | |

| mRNA-BNT162b2 | 56 (97) |

| mRNA-1273 | 2 (3) |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB use, n (%) | 15 (26) |

ACE, Angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB, Angiotensin receptor blocker; CMV, Cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; KDPI, kidney donor profile index; mTOR, Mammalian target of rapamycin; PRA, panel reactive antibodies; RRT, renal replacement therapy;

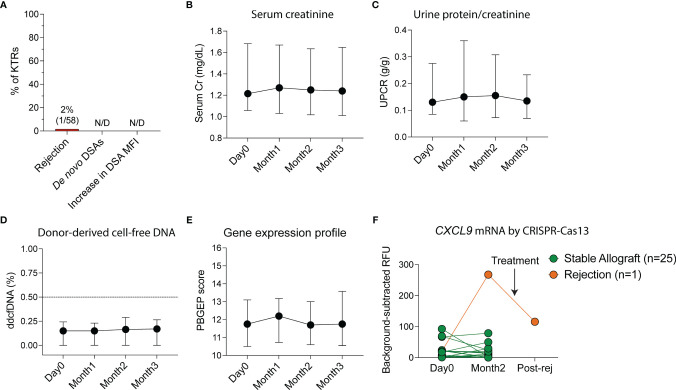

Allograft Rejection, Non-Invasive Rejection Monitoring and De Novo DSA Generation

To monitor for rejection non-invasively, we measured serum creatinine, UPCR, de novo DSAs by single-antigen bead assay, ddcfDNA as a marker of graft injury (22), 5-gene rejection PBGEP (24), and urinary CXCL9 mRNA levels using a CRISPR-Cas13 platform (27). No patients developed de novo DSAs or a significant increase in pre-vaccination DSA mean fluorescent intensities (MFIs) at three months post-vaccination ( Figure 2A ). Only one patient developed acute cellular rejection 40 days following initial vaccination ( Figures 2A and S3 ) in the setting of conversion from tacrolimus to belatacept two days pre-vaccination. He presented with a rise in creatinine concomitant with a rise in urinary CXCL9 mRNA, without de novo DSAs and with stable proteinuria, ddcfDNA levels and PBGEP score. The remaining patients had stable serum creatinine, proteinuria, ddcfDNA levels and PBGEP scores during follow-up ( Figures 2B-E ). At two months post-vaccination, only the patient with rejection had elevated urinary CXCL9 mRNA levels, which decreased with rejection treatment ( Figure 2F ).

Figure 2.

Non-invasive monitoring of allografts in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. (A) Incidence of rejection, de novo donor-specific antibody (DSA) generation and increase in DSA mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) following vaccination (n=58). (B) Non-invasive monitoring for allograft rejection in KTRs with serum creatinine (Cr, n=58, p=0.292) (C) urine protein-creatinine ratio (UPCR, n=58, p=0.428), (D) donor-derived cell-free DNA (ddcfDNA, n=51, p=0.114) and (E) peripheral blood gene expression profile (PBGEP, n=51, p=0.393) score following vaccination. (F) Urine CXCL9 mRNA relative fluorescent units (RFUs) detected by CRISPR-Cas13 in KTRs prior to and following vaccination at 4 weeks after second dose of the vaccine (n=26). (B-E) Medians and IQRs are shown. Statistics by mixed-effect analysis. Post-rej: post-rejection.

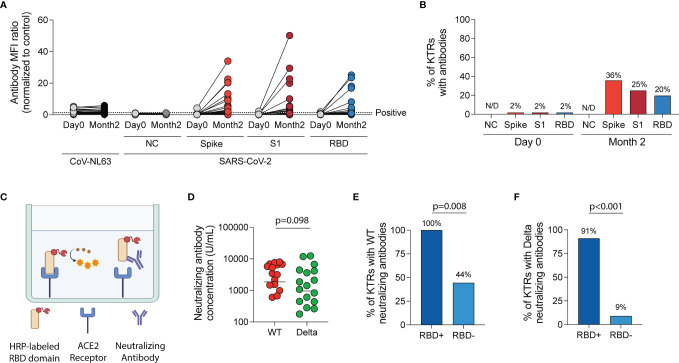

Antibody-Mediated Viral Immunity

After vaccination, there was a significant increase in MFI ratios of antibodies directed against the spike trimer, S1 and RBD domains of wild-type SARS-CoV-2 (p<0.001 for all, Figure 3A ) but no change in MFI ratios for antibodies directed against the nucleocapsid (NC) protein of wild-type SARS-CoV-2 (p=0.309) or against a control virus, CoV-NL63 (p=0.135). Using the positivity threshold recommended by the manufacturer, one patient (2%) had antibodies against the wild-type spike trimer, S1 and RBD regions of the spike protein prior to vaccination. This patient was one of two KTRs with documented prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. At the two-month timepoint after vaccination (median 55 days post-first vaccine, IQR 49-58), no KTRs had anti-NC antibodies but 36%, 25% and 20% had a positive result for antibodies against the spike trimer, S1 and RBD regions of wild-type SARS-CoV-2, respectively ( Figure 3B ).

Figure 3.

Humoral immune response following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs). (A) Anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike antibody and anti-CoV-NL63 antibody MFI ratios (normalized to control) in KTRs pre- and post-vaccination by Luminex-based multiplex assay (n=57). (B) The percentage of KTRs with antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 antigens prior to and following vaccination (n=57). (C) Surrogate virus neutralization test diagram. (D) Concentration of neutralizing antibodies against Wild-type (WT) and Delta (B.1.617.2) variant of SARS-CoV-2 in KTRs with anti-spike antibodies following vaccination (horizontal line at median concentration, n=20). (E) Percentage of anti-spike antibody positive KTRs with neutralizing antibodies against WT and (F) Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 stratified by anti-RBD antibody status (n=20). (A, D) Statistic by Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. (E, F) Statistic by Fisher’s exact test. ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; MFI, median fluorescent intensity; NC, nucleocapsid; RBD, receptor-binding domain.

In KTRs with a positive anti-wild-type spike antibody result, surrogate virus neutralization assay ( Figure 3C ) showed neutralizing responses in 75% and 55% against wild-type and the Delta variant, respectively (p=0.185). The median concentration of neutralizing antibodies was 2,179 U/mL (IQR 638-6,116 U/mL) against wild-type SARS-CoV-2 and 955 U/mL (IQR 278-3,750 U/mL) against the Delta variant (p=0.098, Figure 3D ). KTRs who had both anti-spike and anti-RBD antibodies were more likely to have a neutralizing response against wild-type (RR=2.3 [95% CI:1.1-4.7], Figure 3E ) and Delta variant (RR=9.8 [95% CI: 2.2-55.3], Figure 3F ) of SARS-CoV-2 compared to KTRs who had anti-spike but not anti-RBD antibodies.

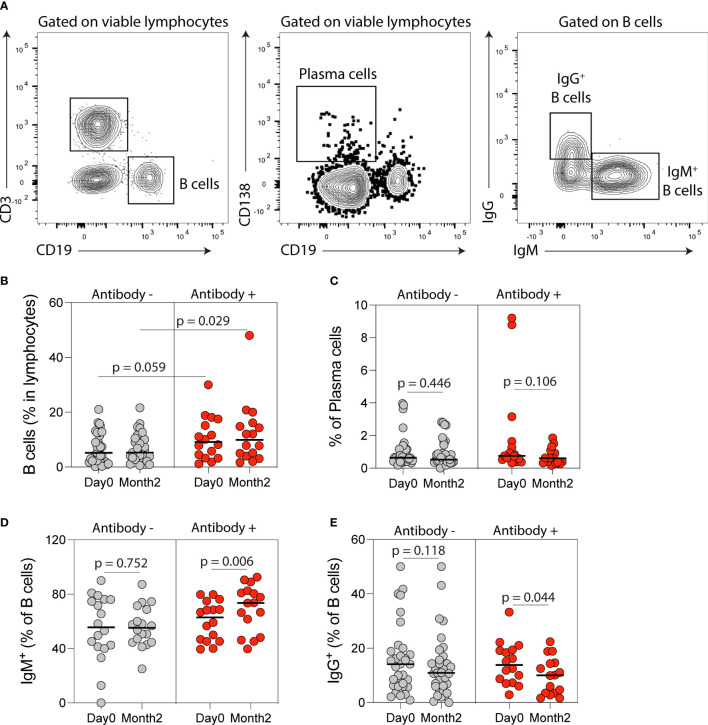

Flow cytometry analysis of circulating B-cell populations ( Figures 4A and S1 ) showed an increase in the percentage of IgM+ B-cells and a decrease in the percentage of IgG+ B-cells post-vaccination ( Figures S4A-N ). When analysis was stratified by anti-spike antibody response post-vaccination, the percentage of B-cells was higher at month two in antibody-positive compared to antibody-negative KTRs (p=0.029, Figure 4B ) and there was a trend towards a higher B-cell percentage at baseline in antibody-positive KTRs (p=0.059, Figure 4B ). There was no difference in the percentage of plasma cells in antibody-positive compared to antibody-negative KTRs pre- or post-vaccination ( Figure 4C ). There was a significant increase in the percentage of IgM+ B-cells (p=0.006, Figure 4D ) and a decrease in the percentage of IgG+ B-cells post-vaccination in antibody-positive KTRs (p=0.044, Figure 4E ). There was also a significant increase in the percentage of IgM+ plasma cells in antibody-positive KTRs post-vaccination (p=0.008, Figure S4O ) but no change in the percentage of IgG+ plasma cells post-vaccination in either group ( Figure S4P ).

Figure 4.

B cell immune phenotyping following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs). (A) Flow cytometry gating strategy of B-cells, plasma, IgM- and IgG-producing B-cells. Percentages of circulating (B) B-cells, (C) plasma cells, (D) IgM+ B-cells and (E) IgG+ B-cells after vaccination in KTRs who developed anti-spike antibodies (Antibody+) compared to KTRs who did not develop anti-spike antibodies (Antibody-) (n=49). (B) Statistic by unpaired t test. (C-E) Statistics by paired t test. Horizontal lines represent mean values.

Cellular Immune Response Following SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination

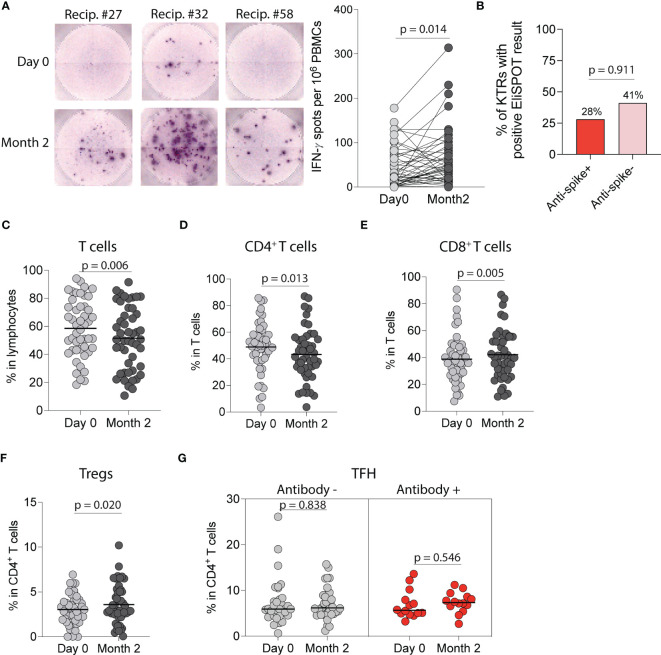

We next characterized anti-SARS-CoV-2 cellular responses by using an EliSPOT that quantifies IFN-γ following wild-type SARS-CoV-2 S1-peptide stimulation of PBMCs. There was a significant increase in IFN-γ spots per 106 PBMCs incubated with S1-peptides at two months compared to pre-vaccination (p=0.014, Figure 5A ) with 38% of KTRs developing an IFN-γ cellular response. When stratified by anti-spike antibody status, there was no difference in the probability of developing a cellular response in antibody-positive vs antibody-negative KTRs (28% vs 41%, p=0.911, Figure 5B ). We also found no difference in the number of IFN-γ spots per 106 PBMCs post-vaccination in antibody-positive vs antibody-negative KTRs (p=0.841), and no correlation between IFN-γ spots post-vaccination and anti-wild-type spike antibody MFIs, (r=0.106, Figure S5A ) anti-S1 antibody MFIs (r=0.115, Figure S5B ), anti-RBD antibody MFIs (r=0.092, Figure S5C ) or anti-wild-type neutralizing antibody concentrations (r=0.222, Figure S5D ).

Figure 5.

Cellular immune response following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs). (A) EliSPOT assay for IFN-γ production by PBMCs from KTRs incubated with SARS-CoV-2 S1 peptides following vaccination (n=53). (B) Percentage of ELISpot response in KTRs stratified by anti-spike antibody status (n=53). Percentage of circulating (C) T-cells, (D) CD4+ T-cells, (E) CD8+ T-cells, and (F) CD4+ regulatory T-cells (Tregs) in KTRs following vaccination (n=49). (G) Percentage of circulating T follicular helper (TFH) cells in KTRs with and without anti-spike antibodies (Antibody + and -, respectively) following vaccination (n=49). (A, C-G) Statistic by Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. Horizontal lines represent median values.

Flow cytometry analysis of circulating T-cell subsets in all KTRs ( Figure S2 ) showed a decrease in the percentage of total T-cells (p=0.006, Figure 5C ) and CD4+ T-cells (p=0.013, Figure 5D ) but an increase in the percentage of CD8+ T-cells (p=0.005, Figure 5E ). Analysis of CD4+ T-cell subsets showed an increase in the percentage of regulatory T cells post-vaccination (p=0.020, Figure 5F ), but no change in the percentage of T follicular helper (p=0.999, Figure S6A ), T follicular regulatory (p=0.132, Figure S6B ), CD4+ naïve (p=0.426, Figure S6C ), CD4+effector memory (p=0.357, Figure S6D ), CD4+central memory (p=0.092, Figure S6E ) or CD4+effector memory RA (TEMRA) T-cells (p=0.054, Figure S6F ) post-vaccination. Stratified analysis of CD4+ T-cell subsets by anti-spike antibody status showed no change in the percentage of T-follicular helper cells in either group ( Figure 5G ) but showed an increase in the percentage of T-follicular regulatory cells in antibody-negative KTRs (p=0.049, Figure S6G ). Analysis of CD8+ T-cell subsets showed a decrease in the percentage of CD8+ naïve T-cells (p=0.021, Figure S6H ) and an increase in the percentage of CD8+ effector memory T-cells (p=0.027, Figure S6I ), but no changes in the percentages of CD8+ central memory (p=0.931, Figure S6J ) or CD8+ TEMRA T-cells (p=0.302, Figure S6K ).

Characteristics Associated With Developing Antibody and Cellular Immune Responses

When evaluating factors associated with antiviral antibody responses, univariate analysis showed that female gender, non-mycophenolate-containing regimens, and steroid-free maintenance regimens were associated with higher odds of developing anti-spike antibodies post-vaccination. After adjustment for age, gender, months post-transplantation, mycophenolate and steroid use in a multivariable logistic regression model, only non-mycophenolate-based regimens and steroid-free regimens remained associated with higher odds of developing anti-spike antibodies ( Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of characteristics associated with the development of anti-spike antibodies following vaccination in kidney transplant recipients.

| Independent variables | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Female vs male | 4.22 (1.36-14.15) | 3.50 (0.97-13.63) |

| Age ≥60 vs <60 years | 0.85 (0.28-2.66) | 0.44 (0.10-1.82) |

| Deceased vs living donor | 0.38 (0.12-1.17) | – |

| Months from transplant: <48 vs ≥48 | 0.75 (0.23-2.31) | 0.72 (0.18-2.75) |

| Basiliximab vs ATG induction | 1.49 (0.43-5.37) | – |

| Belatacept-based vs tacrolimus-based regimen | 0.36 (0.07-1.38) | – |

| Steroid-free vs steroid-maintenance regimen | 5.07 (1.44-19.82) | 4.84 (1.13-23.52) |

| Non-MMF-based vs MMF-based regimen | 4.13 (1.15-16.21) | 5.38 (1.10-30.69) |

| MMF daily dose: >1 g vs ≤1 g | 0.58 (0.08-2.83) | – |

| Tacrolimus trough: ≥6 vs <6 ng/mL | 0.36 (0.07-1.38) | – |

ATG, Antithymocyte globulin; MMF, mycophenolate.

When evaluating factors associated with cellular immune responses, we found no correlation between change in IFN-γ spots from baseline to month two and tacrolimus trough levels (r=0.041), mycophenolate dose (r=-0.230), age (r=0.077) or months post-transplantation (r=0.013). There was also no significant difference in the change in IFN-γ spots from baseline to month two between patients on tacrolimus vs belatacept (p=0.844), mycophenolate-based vs non-mycophenolate-based regimens (p=0.294) and steroid-maintenance vs steroid-free regimens (p=0.140).

Adverse Events and SARS-CoV-2 Infections Following Vaccination

No patients experienced severe adverse events post-vaccination. Two patients developed SARS-CoV-2 infection during follow-up, both of whom were on belatacept and neither of whom had anti-spike antibodies post-vaccination prior to infection ( Table S2 ).

Discussion

In this study, we comprehensively evaluate allograft function, alloimmune and anti-viral responses after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in KTRs. Since serum creatinine (30–32) and proteinuria (33) are not sensitive enough to exclude allograft rejection, we performed additional non-invasive monitoring for rejection using de novo DSAs by single-antigen bead platform, ddcfDNA, 5-gene PGBEP and urinary CXCL9 mRNA by CRISPR-Cas13 platform.

No KTRs in our cohort developed de novo DSAs or an increase in pre-existing DSA MFIs post-vaccination. There was only one episode of rejection in a high-risk patient with a previous history of rejection and recent conversion to belatacept. The patient did not develop de novo DSAs, anti-spike antibodies or an increase in IFN-γ spots post-vaccination, suggesting that the rejection episode was likely unrelated to vaccination. The low risk of clinical rejection is consistent with what has been described prior in a study of 136 KTRs, none of whom developed clinical rejection after SAR-CoV-2 vaccination, although no specific monitoring for rejection was reported in the study beyond what is routinely done clinically (15). In addition, a study of 741 solid organ transplant recipients that surveyed patients 7 days after the second vaccine dose reported only one episode of rejection, but this data was collected by patient report and at a short follow-up duration (16). Another study of 148 KTRs who received two doses of mRNA-1273 found that there were no development of DSA two weeks after the second vaccine dose (13). While consistent with our findings, our study adds to the literature by having a predominantly BNT162b2-vaccinated KTR cohort, longitudinal monitoring for rejection, longer follow-up than prior studies and DSA measurement at a longer follow-up period of 3 months.

The rejection event in our cohort was detected by an elevation in serum creatinine and urinary CXCL9 mRNA levels. CXCL9 is a major chemokine that attracts immune cells to allografts during rejection and has been shown in a multicenter study to be an important non-invasive urinary biomarker of rejection (34). A recent study showed that elevated urinary CXCL9 mRNA levels detected by CRISPR-Cas13 platform had 93% sensitivity for allograft rejection in KTRs (27). However, our study was underpowered to evaluate the utility of urinary CXCL9 mRNA levels as a rejection marker and we did not perform surveillance biopsies to evaluate if urinary CXCL9 mRNA levels are able to detect subclinical rejection.

Plasma ddcfDNA levels, expressed as a percentage of total cell-free DNA, have been shown to be a sensitive marker of alloantibody-mediated rejection, in KTRs (22). However, ddcfDNA levels may be less sensitive for the detection of T-cell mediated rejection (22), which is likely the reason it was not elevated in the patient who developed cellular rejection. The PBGEP (AlloMAP-Kidney) score derived from the expression of five candidate genes has been recently described as a marker of immune quiescence in KTRs (24). For discrimination between rejection and immune quiescence, it has an area under receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.78 and 0.89 as a standalone test and when combined with ddcfDNA, respectively (24). The PBGEP score remained stable following vaccination in our cohort, including in the patient who developed cellular rejection. Further studies are needed to validate the PBGEP score in KTRs including potentially adding other genes to the panel to improve its sensitivity.

This very low rate of clinical acute rejection, in combination with lack of de novo DSA development and stable levels of creatinine, proteinuria, and ddcfDNA levels suggests that SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination is not associated with significant alloimmune responses in KTRs within three months of vaccination. We cannot, however, rule out the occurrence of subclinical rejection since surveillance biopsies were not performed.

In terms of anti-viral responses, we confirmed the low percentage of KTRs who develop anti-spike antibodies post-vaccination described previously (2–4, 8–10, 13, 15, 35–39). We then assessed antibody neutralization capacity using a SVNT, the results of which have been shown to be highly correlated with that of conventional live virus neutralization test (R2 = 0.8591) (40). We found that after two mRNA vaccine doses, there was a trend towards a lower proportion of KTRs having neutralizing responses against the Delta variant compared to wild-type SARS-CoV-2, but this did not meet statistical significance. An important limitation of SVNT is that it only measures RBD-ACE2 interactions, neutralizing antibodies directed against non-RBD regions of the spike protein may not be detected using this assay.

We found that KTRs on mycophenolate-containing regimens were less likely to develop anti-spike antibodies post-vaccination, similar to previous reports in KTRs following influenza (41, 42) and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (2, 15, 37, 38, 43, 44). This is consistent with mycophenolate’s known effect of reducing antibody production in response to foreign antigens mediated by inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase inhibition resulting in diminished B-cell proliferation (45, 46). KTRs on steroid-maintenance regimens were also less likely to develop anti-spike antibodies post-vaccination, similar to previous reports (15, 37).

We found that 38% of KTRs had a cellular immune response by IFN-γ EliSPOT post-vaccination, which is similar to the 30-58% cellular response rates reported in other studies (8, 10, 13, 47). In combination with seroconversion data discussed above, this suggests that KTRs have reduced responses to mRNA vaccination in both B and T-cell arms of the adaptive immune system. Interestingly, we did not find a correlation between immunosuppression regimen characteristics and the magnitude of IFN-γ EliSPOT response in KTRs. While other studies have reported similar findings (9, 10) one study reported that diabetes mellitus, lymphopenia and an eGFR of <60 ml/min/1.73m2 were associated with lower probability of developing a cellular response (13). Importantly, we also found no correlation between the development of anti-spike antibodies and IFN-γ EliSPOT cellular responses, as has been reported previously (10, 13). This suggests that the presence or absence of antibody responses post-vaccination cannot be used to predict whether KTRs have developed cellular responses or not. Both antibody and cellular responses should be measured to fully evaluate anti-viral responses in this high-risk population.

Immunophenotyping of circulating lymphocytes showed a significant increase in the percentage of IgM+ B-cells and IgM+ plasma cells after vaccination in anti-spike antibody positive KTRs. The percentage of T follicular regulatory cells increased after vaccination in anti-spike antibody negative KTRs post-vaccination, consistent with their function in regulating antibody responses (48). We also found a decrease in the percentage of CD8+ naïve T cells and an increase in the percentage of CD8+ effector memory T cells after vaccination, suggesting a possible effect of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination on effector T cell function in KTRs (49, 50). Despite these changes, using immune phenotyping of circulating lymphocytes alone is insufficient to distinguish KTRs who will or will not develop anti-spike antibodies following vaccination. A limitation of our immunophenotyping is that the changes noted (e.g. increase in the percentage of IgM+ B-cells) were for the total pool of the analyzed immune cells, and not antigen-specific cells from each subset. Assessment of germinal center responses in the draining lymph nodes of vaccinated KTRs is likely to be more informative compared to immunophenotyping of circulating lymphocytes with regards to predicting antibody responses to vaccination (51).

Only two patients (3%) developed symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections during follow-up. This rate of breakthrough infection is similar to what has been reported previously in KTRs (15, 39, 52, 53), but is higher than what has been reported in healthy individuals of 0.08-0.4% (54, 55). Neither of the two patients had anti-spike antibodies prior to infection. This is similar to what has been reported in other studies of breakthrough infections in KTRs (53, 56), and may suggest a potentially increased susceptibility to infection in KTRs who do not develop antibodies post-vaccination. The effect of antibody and cellular immune responses on the risk and severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection in KTRs needs to be explored in future studies.

Our study has several limitations including the relatively small sample size, predominantly BNT162b2-vaccinated cohort, the lack of a matched unvaccinated KTR control group for comparison, and inability to diagnose subclinical rejection since no surveillance biopsies were performed. Despite these limitations, we were able to perform a detailed and granular characterization of both anti-viral and alloimmune responses post-vaccination.

In summary, we found that SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in KTRs was safe and not associated with significant alloimmune risks or decline in allograft function. Despite diminished anti-viral antibody and cellular responses, we found that the absolute risk of developing symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection post-vaccination was higher, albeit with very small numbers, than previously reported in immunocompetent individuals (54, 55). Further studies are needed to determine the degree of clinical protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection gained by the cellular and antibody immune responses generated and the long-term efficacy of mRNA vaccines in KTRs to inform future vaccination strategies, including higher doses of vaccines, additional booster doses of the same vaccine or a combination of vaccines (43, 57–61).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board (Protocol#: 2021P000043). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AAJ, RG, TB, OE, AA, JC, CK, JA, and LR. Data curation, AAJ, FH, PP, and MM. Formal analysis, AAJ, RG, TB, ZS, FH, IL, OE, BB, VP, IR, PC, and LR. Funding acquisition, AAJ, JA, and LR. Investigation, AAJ, RG, TB, ZS, IL, BB, PC, CK, and LR. Methodology, AAJ, RG, TB, IL, OE, PP, JC, BB, VP, PC, CK, JA, and LR. Project administration, AAJ, ZS, FH, IL, OE, AA, PP, MM, VP, JA, and LR. Validation, AAJ and IL. Visualization, AAJ, TB, and IR. Supervision, IL, AA, PP, JC, MM, BB, and LR. Writing-original draft, AAJ and IR. Writing-review and editing, AAJ, RG, TB, ZS, IL, VP, PC, CK, JA, and LR. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The study was funded by CareDx, Inc. (Brisbane, CA) grant number 2021A008053 to LR and JA. The study was also supported in part by the Harold and Ellen Danser Endowed/Distinguished Chair in Transplantation at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA, USA). This was an investigator-initiated research project where the design and conduct of the study was determined by the investigator without influence from the funders.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff of the transplant clinic for their assistance in conducting this study.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.838985/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1. Caillard S, Chavarot N, Francois H, Matignon M, Greze C, Kamar N, et al. Is COVID-19 Infection More Severe in Kidney Transplant Recipients? Am J Transplant (2021) 21:1295–303. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boyarsky BJ, Werbel WA, Avery RK, Tobian AAR, Massie AB, Segev DL, et al. Antibody Response to 2-Dose SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine Series in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. JAMA (2021) 325:2204–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benotmane I, Gautier-Vargas G, Cognard N, Olagne J, Heibel F, Braun-Parvez L, et al. Low Immunization Rates Among Kidney Transplant Recipients Who Received 2 Doses of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. Kidney Int (2021) 99:1498–500. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rincon-Arevalo H, Choi M, Stefanski A, Halleck F, Weber U, Szelinski F, et al. Impaired Humoral Immunity to SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 Vaccine in Kidney Transplant Recipients and Dialysis Patients. Sci Immunol (2021) 6:1–15. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abj1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Qin CX, Moore LW, Anjan S, Rahamimov R, Sifri CD, Ali NM, et al. Risk of Breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 Infections in Adult Transplant Recipients. Transplantation (2021) 105:e265–6. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ravanan R, Mumford L, Ushiro-Lumb I, Callaghan C, Pettigrew G, Thorburn D, et al. Two Doses of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines Reduce Risk of Death Due to COVID-19 in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: Preliminary Outcomes From a UK Registry Linkage Analysis. Transplantation (2021) 105:e263–4. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Malinis M, Cohen E, Azar MM. Effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in Fully Vaccinated Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Am J Transplant (2021) 21:2916–8. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chavarot N, Ouedrani A, Marion O, Leruez-Ville M, Villain E, Baaziz M, et al. Poor Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Humoral and T-Cell Responses After 2 Injections of mRNA Vaccine in Kidney Transplant Recipients Treated With Belatacept. Transplantation (2021) 105:e94–5. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sattler A, Schrezenmeier E, Weber UA, Potekhin A, Bachmann F, Straub-Hohenbleicher H, et al. Impaired Humoral and Cellular Immunity After SARS-CoV2 BNT162b2 (Tozinameran) Prime-Boost Vaccination in Kidney Transplant Recipients. J Clin Invest (2021) 131:e1–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI150175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bertrand D, Hamzaoui M, Lemée V, Lamulle J, Hanoy M, Laurent C, et al. Antibody and T Cell Response to SARS-CoV-2 Messenger RNA BNT162b2 Vaccine in Kidney Transplant Recipients and Hemodialysis Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol (2021) 32:2147–52. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2021040480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kumar D, Ferreira VH, Hall VG, Hu Q, Samson R, Ku T, et al. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Variants in Transplant Recipients After Two and Three Doses of mRNA-1273 Vaccine : Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med (2021) 175:226–33. doi: 10.7326/M21-3480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. CDC: Variant Proportions (2021). Available at: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions (Accessed August 12, 2021).

- 13. Cucchiari D, Egri N, Bodro M, Herrera S, Del Risco-Zevallos J, Casals-Urquiza J, et al. Cellular and Humoral Response After mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Am J Transplant (2021) 21:2727–39. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Del Bello A, Marion O, Delas A, Congy-Jolivet N, Colombat M, Kamar N. Acute Rejection After Anti-SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccination in a Patient Who Underwent a Kidney Transplant. Kidney Int (2021) 100:238–9. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grupper A, Rabinowich L, Schwartz D, Schwartz IF, Ben-Yehoyada M, Shashar M, et al. Reduced Humoral Response to mRNA SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 Vaccine in Kidney Transplant Recipients Without Prior Exposure to the Virus. Am J Transplant (2021) 121:2719–26. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ou MT, Boyarsky BJ, Motter JD, Greenberg RS, Teles AT, Ruddy JA, et al. Safety and Reactogenicity of 2 Doses of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Transplantation (2021) 105:2170–4. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wadhwa A, Aljabbari A, Lokras A, Foged C, Thakur A. Opportunities and Challenges in the Delivery of mRNA-Based Vaccines. Pharmaceutics (2020) 12:e1–27. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12020102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pardi N, Hogan MJ, Weissman D. Recent Advances in mRNA Vaccine Technology. Curr Opin Immunol (2020) 65:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2020.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Houseley J, Tollervey D. The Many Pathways of RNA Degradation. Cell (2009) 136:763–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Roberts PC, Makhene M, Coler RN, et al. An mRNA Vaccine Against SARS-CoV-2 - Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med (2020) 383:1920–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wong L, Scott S, Grskovic M, Dholakia S, Woodward Robert N. Medical Diagnostic Methods The Evolution and Innovation of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Testing in Transplantation. J Med Diagn Meth (2020) 9:e1–5. doi: 10.35248/2168-9784.2020.9.302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bloom RD, Bromberg JS, Poggio ED, Bunnapradist S, Langone AJ, Sood P, et al. Cell-Free DNA and Active Rejection in Kidney Allografts. J Am Soc Nephrol (2017) 28:2221–32. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016091034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stites E, Kumar D, Olaitan O, John Swanson S, Leca N, Weir M, et al. High Levels of dd-cfDNA Identify Patients With TCMR 1A and Borderline Allograft Rejection at Elevated Risk of Graft Injury. Am J Transplant (2020) 20:2491–8. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Akalin E, Weir MR, Bunnapradist S, Brennan DC, Delos Santos R, Langone A, et al. Clinical Validation of an Immune Quiescence Gene Expression Signature in Kidney Transplantation. Kidney (2021) 360:1998–2009. doi: 10.34067/KID.0005062021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Deng MC, Eisen HJ, Mehra MR, Billingham M, Marboe CC, Berry G, et al. Noninvasive Discrimination of Rejection in Cardiac Allograft Recipients Using Gene Expression Profiling. Am J Transplant (2006) 6:150–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01175.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Christakoudi S, Runglall M, Mobillo P, Tsui T-L, Duff C, Domingo-Vila C, et al. Development of a Multivariable Gene-Expression Signature Targeting T-Cell-Mediated Rejection in Peripheral Blood of Kidney Transplant Recipients Validated in Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Samples. EBioMedicine (2019) 41:571–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.01.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kaminski MM, Alcantar MA, Lape IT, Greensmith R, Huske AC, Valeri JA, et al. A CRISPR-Based Assay for the Detection of Opportunistic Infections Post-Transplantation and for the Monitoring of Transplant Rejection. Nat BioMed Eng (2020) 4:601–9. doi: 10.1038/s41551-020-0546-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ni L, Ye F, Cheng M-L, Feng Y, Deng Y-Q, Zhao H, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2-Specific Humoral and Cellular Immunity in COVID-19 Convalescent Individuals. Immunity (2020) 52:971–977.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Janetzki S, Price L, Schroeder H, Britten CM, Welters MJP, Hoos A. Guidelines for the Automated Evaluation of Elispot Assays. Nat Protoc (2015) 10:1098–115. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rush DN, Henry SF, Jeffery JR, Schroeder TJ, Gough J. Histological Findings in Early Routine Biopsies of Stable Renal Allograft Recipients. Transplantation (1994) 57:208–11. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199401001-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shapiro R, Jordan ML, Scantlebury VP, Vivas CA, Jain A, McCauley J, et al. Renal Allograft Rejection With Normal Renal Function in Simultaneous Kidney/Pancreas Recipients: Does Dissynchronous Rejection Really Exist? Transplantation (2000) 69:440–1. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200002150-00024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Roberts ISD, Reddy S, Russell C, Davies DR, Friend PJ, Handa AI, et al. Subclinical Rejection and Borderline Changes in Early Protocol Biopsy Specimens After Renal Transplantation. Transplantation (2004) 77:1194–8. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000118905.98469.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Parajuli S, Reville PK, Ellis TM, Djamali A, Mandelbrot DA. Utility of Protocol Kidney Biopsies for De Novo Donor-Specific Antibodies. Am J Transplant (2017) 17:3210–8. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hricik DE, Nickerson P, Formica RN, Poggio ED, Rush D, Newell KA, et al. Multicenter Validation of Urinary CXCL9 as a Risk-Stratifying Biomarker for Kidney Transplant Injury. Am J Transplant (2013) 13:2634–44. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Husain SA, Tsapepas D, Paget KF, Chang J-H, Crew RJ, Dube GK, et al. Postvaccine Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Antibody Development in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Kidney Int Rep (2021) 6:1699–700. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Korth J, Jahn M, Dorsch O, Anastasiou OE, Sorge-Hädicke B, Eisenberger U, et al. Impaired Humoral Response in Renal Transplant Recipients to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination With BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech). Viruses (2021) 13:e1–6. doi: 10.3390/v13050756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Midtvedt K, Tran T, Parker K, Marti H-P, Stenehjem A-E, Gøransson LG, et al. Low Immunization Rate in Kidney Transplant Recipients Also After Dose 2 of the BNT162b2 Vaccine: Continue to Keep Your Guard Up! Transplantation (2021) 105:e80–1. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Marinaki S, Adamopoulos S, Degiannis D, Roussos S, Pavlopoulou ID, Hatzakis A, et al. Immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 Vaccine in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Am J Transplant (2021) 21:2913–5. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rozen-Zvi B, Yahav D, Agur T, Zingerman B, Ben-Zvi H, Atamna A, et al. Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine Among Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Prospective Cohort Study. Clin Microbiol Infect (2021) 27:e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tan CW, Chia WN, Qin X, Liu P, Chen MI-C, Tiu C, et al. A SARS-CoV-2 Surrogate Virus Neutralization Test Based on Antibody-Mediated Blockage of ACE2-Spike Protein-Protein Interaction. Nat Biotechnol (2020) 38:1073–8. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0631-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Salles MJC, Sens YAS, Boas LSV, Machado CM. Influenza Virus Vaccination in Kidney Transplant Recipients: Serum Antibody Response to Different Immunosuppressive Drugs. Clin Transplant (2010) 24:E17–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.01095.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mulley WR, Visvanathan K, Hurt AC, Brown FG, Polkinghorne KR, Mastorakos T, et al. Mycophenolate and Lower Graft Function Reduce the Seroresponse of Kidney Transplant Recipients to Pandemic H1N1 Vaccination. Kidney Int (2012) 82:212–9. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Del Bello A, Abravanel F, Marion O, Couat C, Esposito L, Lavayssière L, et al. Efficiency of a Boost With a Third Dose of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Messenger RNA-Based Vaccines in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Am J Transplant (2021) 22:322–3. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kantauskaite M, Müller L, Kolb T, Fischer S, Hillebrandt J, Ivens K, et al. Intensity of Mycophenolate Mofetil Treatment is Associated With an Impaired Immune Response to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Am J Transplant (2021) 22:634–9. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Eugui EM, Mirkovich A, Allison AC. Lymphocyte-Selective Antiproliferative and Immunosuppressive Effects of Mycophenolic Acid in Mice. Scand J Immunol (1991) 33:175–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1991.tb03747.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eugui EM, Almquist SJ, Muller CD, Allison AC. Lymphocyte-Selective Cytostatic and Immunosuppressive Effects of Mycophenolic Acid In Vitro: Role of Deoxyguanosine Nucleotide Depletion. Scand J Immunol (1991) 33:161–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1991.tb03746.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Miele M, Busà R, Russelli G, Sorrentino MC, Di Bella M, Timoneri F, et al. Impaired Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Humoral and Cellular Immune Response Induced by Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA Vaccine in Solid Organ Transplanted Patients. Am J Transplant (2021) 21:2919–21. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Linterman MA, Pierson W, Lee SK, Kallies A, Kawamoto S, Rayner TF, et al. Foxp3+ Follicular Regulatory T Cells Control the Germinal Center Response. Nat Med (2011) 17:975–82. doi: 10.1038/nm.2425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Oberhardt V, Luxenburger H, Kemming J, Schulien I, Ciminski K, Giese S, et al. Rapid and Stable Mobilization of CD8+ T Cells by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine. Nature (2021) 597:268–73. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03841-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chen Y, Yin S, Tong X, Tao Y, Ni J, Pan J, et al. Dynamic SARS-CoV-2-Specific B-Cell and T-Cell Responses Following Immunization With an Inactivated COVID-19 Vaccine. Clin Microbiol Infect (2021) 28:e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lederer K, Bettini E, Parvathaneni K, Painter MM, Agarwal D, Lundgreen KA, et al. Germinal Center Responses to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccines in Healthy and Immunocompromised Individuals. Cell (2022). doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tsapepas D, Paget K, Mohan S, Cohen DJ, Husain SA. Clinically Significant COVID-19 Following SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Am J Kidney Dis (2021) 78:314–7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Song CC, Christensen J, Kumar D, Vissichelli N, Morales M, Gupta G. Early Experience With SARs-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine Breakthrough Among Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transpl Infect Dis (2021) 23:e13654. doi: 10.1111/tid.13654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med (2021) 384:403–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med (2020) 383:2603–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Caillard S, Chavarot N, Bertrand D, Kamar N, Thaunat O, Moal V, et al. Occurrence of Severe COVID-19 in Vaccinated Transplant Patients. Kidney Int (2021) 100:477–9. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Woodle ES, Gebel HM, Montgomery RA, Maltzman JS. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination, Immune Responses, and Antibody Testing in Immunosuppressed Populations: Tip of the Iceberg. Transplantation (2021) 105:1911–3. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kamar N, Abravanel F, Marion O, Couat C, Izopet J, Del Bello A. Three Doses of an mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in Solid-Organ Transplant Recipients. N Engl J Med (2021) 385:661–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2108861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Werbel WA, Boyarsky BJ, Ou MT, Massie AB, Tobian AAR, Garonzik-Wang JM, et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of a Third Dose of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: A Case Series. Ann Intern Med (2021) 174:1330–2. doi: 10.7326/L21-0282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hall VG, Ferreira VH, Ku T, Ierullo M, Majchrzak-Kita B, Chaparro C, et al. Randomized Trial of a Third Dose of mRNA-1273 Vaccine in Transplant Recipients. N Engl J Med (2021) 385:1244–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2111462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Benotmane I, Gautier G, Perrin P, Olagne J, Cognard N, Fafi-Kremer S, et al. Antibody Response After a Third Dose of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Kidney Transplant Recipients With Minimal Serologic Response to 2 Doses. JAMA (2021) 326:1063–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.12339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.