Abstract

Purpose

With the growing interest in advanced image-guidance for surgical robot systems, rapid integration and testing of robotic devices and medical image computing software are becoming essential in the research and development. Maximizing the use of existing engineering resources built on widely accepted platforms in different fields, such as Robot Operating System (ROS) in robotics and 3D Slicer in medical image computing could simplify these tasks. We propose a new open network bridge interface integrated in ROS to ensure seamless cross-platform data sharing.

Methods

A ROS node named ROS-IGTL-Bridge was implemented. It establishes a TCP/IP network connection between the ROS environment and external medical image computing software using the OpenIGTLink protocol. The node exports ROS messages to the external software over the network and vice versa simultaneously, allowing seamless and transparent data sharing between the ROS-based devices and the medical image computing platforms.

Results

Performance tests demonstrated that the bridge could stream transforms, strings, points, and images at 30 fps in both directions successfully. The data transfer latency was less than 1.2 ms for transforms, strings, and points, and 25.2 ms fo rcolor VGA images. A separate test also demonstrated that the bridge could achieve 900 fps for transforms. Additionally, the bridge was demonstrated in two representative systems: a mock image-guided surgical robot setup consisting of 3D Slicer, and Lego Mindstorms with ROS as a prototyping and educational platform for IGT research; and the smart tissue autonomous robot (STAR) surgical setup with 3D Slicer.

Conclusion

The study demonstrated that the bridge enabled cross-platform data sharing between ROS and medical image computing software. This will allow rapid and seamless integration of advanced image-based planning/navigation offered by the medical image computing software such as 3D Slicer into ROS-based surgical robot systems.

Keywords: ROS, OpenIGTLink, interface, surgical robot, image guided therapy

1 Introduction

The use of robotic systems in image guided therapy (IGT) has expanded in many medical fields leading to a continuous rise of technology in modern medicine [1]. Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery has become common in radical prostatectomies in the United States and other developed countries [2] and expanding its use in other procedures. Robotic catheter systems have been used for a wide variety of endovascular procedures [3] and cardiac arrhythmia procedures [4]. Robotic radiosurgery systems have been used to treat tumors of the lung, liver, pancreas, spine, kidney, head, and neck, and prostate [5].

While most of todays clinical robotic systems are designed to assist surgeons by following their commands and plans, there has been a growing interest in autonomous assistance, where robotic systems take over some of the surgeons routine tasks, such as cutting and suturing, to let the surgeons focus on high-level surgical decisions [6,7]. With this growing interest in autonomous technologies, researchers and surgeons face a vast variety of technology in the operating room. This growing interest motivates the medical robotics community to take advantage of a wide variety of features incorporated in the Robot-Operating-System (ROS) [8] , such as computer vision, sensing, kinematics, simulation, and motion planning. Robotic research systems including medical robots Raven II [9] and the da Vinci Research Kit (dVRK) [10] and the KUKA light weight robot (LWR) [11] have used ROS as a software platform.

However, the ROS platform is not an ideal environment to perform certain clinical tasks. Specifically, modern surgical planning and guidance heavily rely on medical images to identify and localize diseased areas and critical structures. Furthermore, such navigational information must be mapped onto the physical space in order to achieve safe and accurate treatment. While ROSs versatility allows researchers to implement such features by themselves, many of them have already been available in some research platforms that are specifically developed for medical image computing and image-guided therapy, such as 3D Slicer [12], IGSTK [13], MITK [14] or NifTK [15], OsiriX [16], the XIP-Builder [17], and MeVisLab [18]. Therefore, bridging a robotics research platform such as the ROS with medical image computing platforms is becoming important for the development of advanced medical robotics systems. By bringing popular platforms extensively developed in the two research fields together, researchers can take advantage of rich engineering resources from both fields.

Bridging a popular platform like ROS with medical image computing platforms would further benefit the medical robotics research. Because of the wide variety of robot hardware supported by ROS, ranging from hobby-oriented products to industry-grade high dexterity robots, one can switch hardware easily, or scale-up the system from a proof-of-concept prototype to a fully-functional system for animal and human studies, without significantly changing the software architecture. Therefore, the bridge will make the iteration of prototyping and testing easier and faster.

The goal of this study was to develop a new software interface that bridges ROS and popular medical image computing software, 3D Slicer, and provide a research and engineering tool that supports the development of image-guided and robot assisted surgery system. The two software platforms seamlessly share data and commands through a TCP/IP network using the open network communication protocol, OpenIGTLink [19].

In this paper, we describe the system architecture and its implementation, as well as a proof-of-concept scenario. The structure of the implemented bridge in ROS and the conversions between ROS and OpenIGTLink messages are explained in the Methods section. Subsequently, the results of network communication performance tests are presented in the Experiments section followed by the Use Cases section that provides an outlook on the capabilities of the network bridge. The experimental results and use cases are discussed in the Discussion section.

2 Methods

2.1 ROS-IGTL-Bridge node

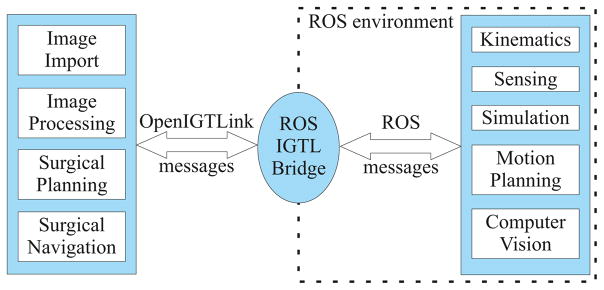

The core component of our software interface is a ROS-node named ROS-IGTL-Bridge. The ROS-IGTL-Bridge works as one of nodes in a ROS-based system, and establishes a TCP/IP socket connection with 3D Slicer or other external medical image computing software equipped with a socket interface. It can be configured to run either as a TCP/IP server or client. ROS provides a graph architecture consisting of multiple nodes that are connected by the peer-to-peer network and process data together. Nodes can publish a ROS message to a given topic, and other nodes can receive the message by subscribing to the topic. The ROS-IGTL-Bridge node translates a ROS message to an OpenIGTLink message and sends it to external software through the TCP/IP connection. It also receives an OpenIGTLink message, translates it to a ROS message, and publishes it in the ROS network (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The ROS-IGTL-Bridge works as a message interface between medical image computing software that supports image import, image processing, surgical planning and surgical navigation (left), and the ROS environment that offers kinematic calculations, sensing, simulation, motion planning and computer vision (right).

The interface supports data types commonly used in the context of image-guided and robot-assisted therapy. Supported data types are listed in the next section.

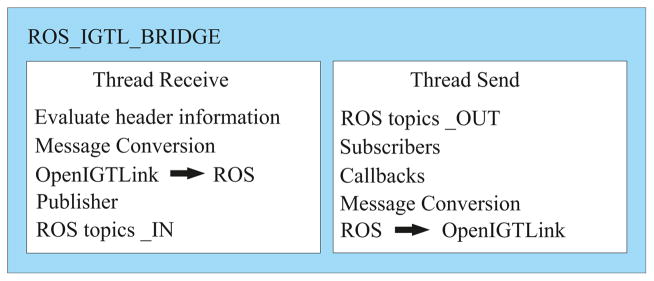

The ROS-IGTL-Bridge node process consists of two independent POSIX threads allowing simultaneous data sending and receiving (Fig. 2). Methods for message serialization and deserialization for the OpenIGTLink communication were implemented per message types as callback functions, and called by the two threads. Incoming messages received through the OpenIGTLink connection are evaluated by the header information of the message, and published to their corresponding ROS-Topic in the ROS network.

Fig. 2.

Data processing by the bridge consisting of two independent POSIX threads. The thread ”Receive” (left) handles incoming Open-IGTLink messages by evaluating the header information and execute message conversion to subsequently publish the data to the corresponding ROS topic. Simultaneously, the thread ”Send” sends outgoing messages after previously triggered callbacks on subscribed ROS topics (right).

The created topics in the ROS network are marked with OUT for outgoing data and IN for incoming data. The ROS-IGTL-Bridge node can easily be configured by using launch files and setting the parameter server IP, port and client/server flag. Furthermore, an autonomous testing node ROS-IGTL-Test can be used to evaluate the functionality by sending dummy data and visualizing received data on subscribed ROS-topics. During the test routine a random transform, a point, a pointcloud containing 20 points, a string and a sample vtkPolyData model are sent.

2.2 Message Types Supported in ROS-IGTL-Bridge

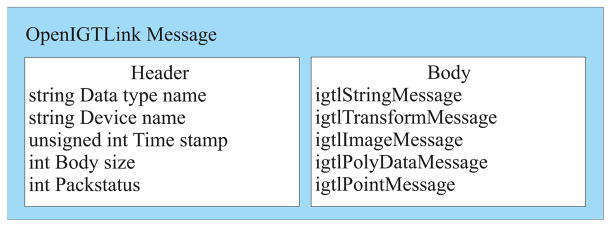

The ROS-IGTL-Bridge supports various types of data that are frequently used in IGT applications. Those supported types include string, transform, image, poly data, and point. The following paragraphs detail the supported OpenIGT-Link messages along with corresponding topics in ROS. To determine the conversion method from an OpenIGTLink message to a corresponding ROS message, the ROS-IGTL-Bridge uses the header section of an OpenIGTLink message, which provides meta-data including type name, device name, time stamp, body size and pack status (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The basic structure of an OpenIGTLink Message consists of generic header information including data type, name, time stamp, size and pack status and a data type specific body section.

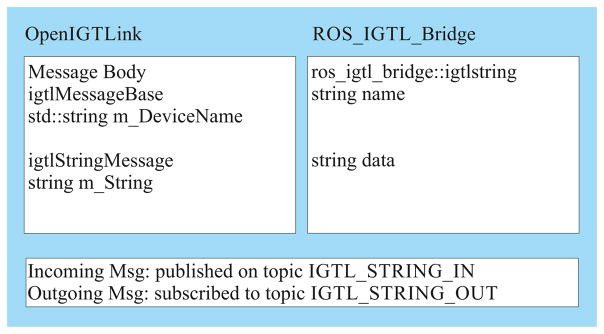

2.2.1 String

The exchange of string messages between the device and external image computing software allows sending and receiving commands or status updates. Thus, the graphical user interfaces of the external software can be extended to display information like acknowledgments about received data, or to give instructions for controlling used devices (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Corresponding data fields in string messages for OpenIGTLink and ROS-IGTL-Bridge.

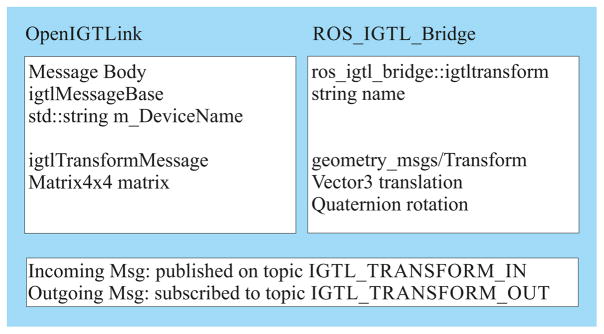

2.2.2 Transform

The transform messages can contain a linear transform representing the positions and orientations of devices, objects of interests, etc, measured by sensors connected to ROS, or generated on the external image computing software. The messages can be used to monitor the positions and orientations of tools, devices, and objects, or providing planning data to the devices. The OpenIGTLink igtlTransformMessage is represented by a 4 × 4 matrix and converted to the ROS message type geometry msgs/Transform containing a vector for translation and a quaternion for orientation (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Corresponding data fields in transform messages for Open-IGTLink and ROS-IGTL-Bridge. ROS standard data type geometry msgs/Transform contains translation as a 3-element vector and rotation as a quaternion.

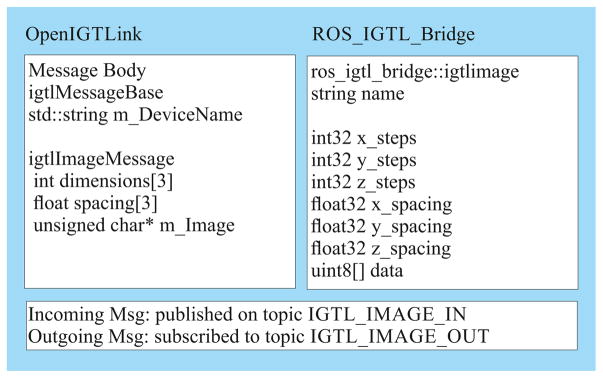

2.2.3 Image

Figure 6 shows the attributes of the corresponding image messages. An image consists of sizing and spacing parameters for each dimension in 3D space. The data is stored in an 8-bit array with the size of image dimensions. It is possible to send a 2D video stream from ROS using the IGTL VIDEO OUT topic which supports the common ROS message type sensor msgs/Image. Thus, camera data can directly be forwarded to the bridge and no additional message conversion is required.

Fig. 6.

Corresponding data fields in image messages for OpenIGTLink and ROS-IGTL-Bridge. The messages contain meta information of the volume including the size and spacings as well as the pixel data.

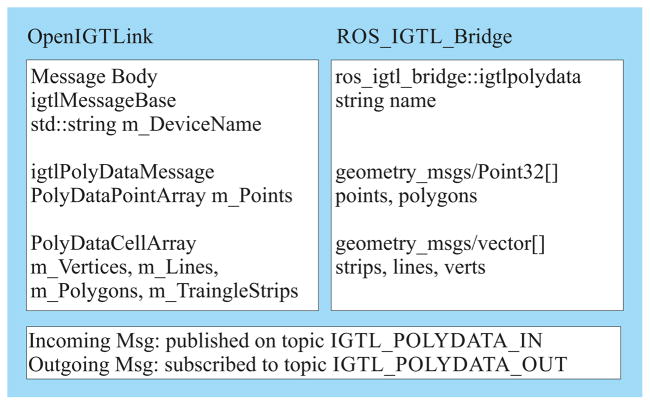

2.2.4 Poly Data

The poly data message allows the transfer of 3D models composed of points and additional surface information. Polygons, triangle strips, lines or vertices represent the structure of the mesh. Due to the lack of an explicit equivalent to the vtkPolyData message in ROS, methods for converting vtkPolyData to the ros igtl bridge::igtlpolydata message are provided.

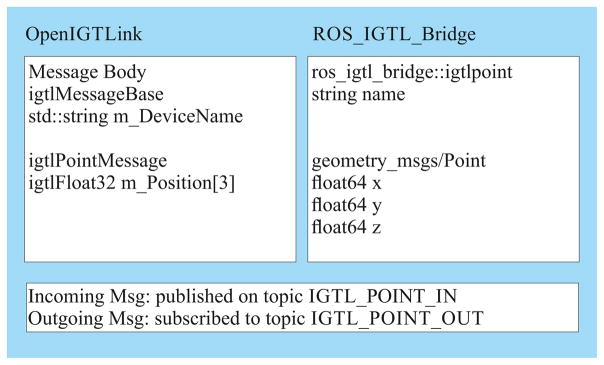

2.2.5 Point

The point message consists of 3D point data allowing to send and obtain target points as a robot’s movement destination, the manipulator’s position or landmark coordinates for registration purposes or moreover sensor data in the form of point clouds and point lists (Fig. 8). Additionally the bridge is able to send point clouds in the form of geometry msgs/Point published on the IGTL POINTCLOUD OUT topic.

Fig. 8.

Corresponding data fields in point messages for OpenIGTLink and ROS-IGTL-Bridge. geometry msgs/Point contains the x-, y-, and z- coordinates of the point.

2.3 System Configuration and Message Scheme

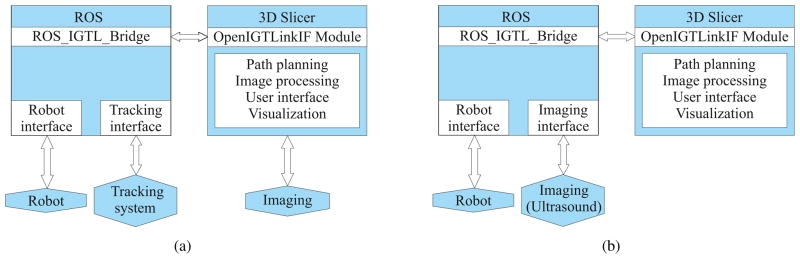

The use of different message types depends on the system configuration and the required message scheme to operate the IGT setup. Figure 10 shows two representative system configurations as example applications for using the ROS-IGTL-Bridge.

Fig. 10.

Example setups showing the capabilities of ROS-IGTL-Bridge. (a) Robot and tracking system are connected to ROS and controlled by 3D Slicer through the ROS-IGTL-Bridge. The imaging device is connected directly to 3D Slicer using the OpenIGTLink interface. (b) The robot and imaging device (Ultrasound) are connected to the robot operated by ROS and controlled by 3D Slicer through the ROS-IGTL-Bridge.

The first example IGT setup consists of robot and tracking systems both of which are operated by ROS using already existing ROS nodes. The tracking system is used to track the end-effector of the robot. An external imaging device, for instance optical coherence tomography (OCT), ultrasound, or MRI, is connected to a medical image computing platform like 3D Slicer that provides methods for processing and visualization of such medical data (Fig. 10a). By bridging the ROS message environment and the medical image computing platform the function sets can efficiently complement each other. Commands and status updates are exchanged using the string message conversion of the bridge, so the user interface of the surgical planning tool can be used to operate the system. The transformation message allows for getting continuously refreshed tracking data or to command a certain position in six degrees of freedom. Robot model data could be transferred as poly data model to be visualized in 3D Slicer. Raw point cloud or image data of the tracking device can be forwarded to the image processing platform in order to localize robot position or perform path planning.

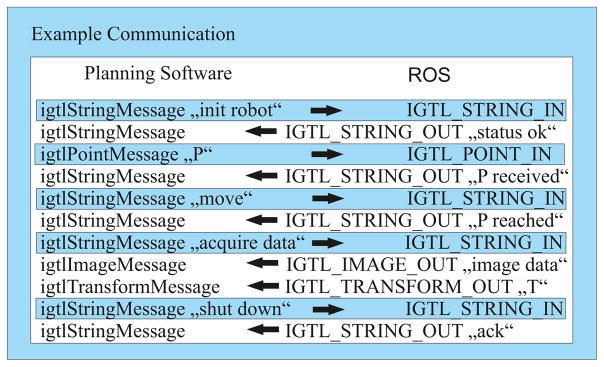

The second example represents a robot guided imaging device possibly an ultrasound probe attached to the robots end-effector (Fig. 10b). The robot as well as the imaging device are controlled by downloadable standard ROS-nodes allowing simple integration in the desired setup. To access or publish data in the resulting ROS message environment, the communication with an external surgical planning platform like 3D Slicer is established using the ROS-IGTL-Bridge node. Therefore, robot control as well as image device commands and responses can be transferred as string messages via the network bridge. Additionally, a positioning command as point or transformation message can be sent to the ROS environment. Acquired image data is forwarded to the planning software controlling the robot as image or point cloud messages and thus, the image processing and visualization methods can be used to compare intraoperative with preoperative data. Fig. 9 shows a possible communication protocol between the ROS environment and a surgical planning platform while performing image acquisition after being commanded to a specific point location.

Fig. 9.

Possible communication protocol between a surgical planning software and a ROS operated robot using the ROS IGTL Bridge as network interface. The robot is initialized, commanded to move to a point and acquire image data with additional transform information. Finally, the robot is shut down.

3 Experiments

We evaluated the performance of network communication between ROS and 3D Slicer using a mock image-guided surgical robot system. In addition, we demonstrated the feasibility of the software in two representative use-case scenarios: educational/rapid-prototype image-guided surgical navigation system based on Lego Mindstorms, and autonomous suturing robot.

3.1 Experimental Setup

The mock image-guided surgical robot system consists of two computers: a Linux-based computer (Precision M3800, Quad-Core Intel Core i7-4712HQ 2.3 GHz, 16 GB 1600MHz DDR3 memory, Ubuntu Linux 14.04LTS, Dell Inc., Round Rock, TX) that mimics a robot controller, and a Mac-based workstation (Mac Pro, Dual 6-Core Intel Xeon 2.66 GHz and 40 GB 1333 MHz DDR3 memory, Mac OS X 10.10, Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA) that mimics a workstation for surgical planning and navigation interface. The two computers are connected to a 8-port gigabit Ethernet switch (SG100D-08, Cisco Systems Inc., San Jose, CA) via Cat 5e cables. ROS Indigo was installed on the Linux-based computer with the ROS-IGTL-Bridge node. On the Mac workstation, 3D Slicer 4.6 was installed for visualizing data transferred from the ROS.

In order to evaluate the latency, the sender embedded the time of data generation in the message header based on the internal clock of the sender. Once the message is received by the receiver, the receiver extracts the time of data generation, and compare it with the internal clock of the receiver to calculate the time spent for data transfer between the two simulators. For accurate determination of the latency, the internal clocks of the two computers were synchronized using PTPd [20]. PTPd synchronizes the internal clock to the master clock through the network using the Precision Time Protocol (PTP) defined in the IEEE 1588-2008 standard. Unlike the widely-used Network Time Protocol (NTP) [21], PTP is designed for more accurate clock synchronization between computers connected to the local area network (LAN).

3.2 Evaluation of Data Transfer Performance

Using this setup, we evaluated the performance of data transfer for transforms, strings, points, and images. These data types are often used for real-time data sharing, such as tool tracking, video streaming, and status monitoring, and thus it is crucial to ensure the data delivery with appropriate frame rate and latency.

We deployed two custom software simulators, namely ROS Test Node and IGTL Test Server, on the Linux computer and Mac workstation respectively. ROS Test Node is a ROS node that communicates with the ROS-IGTL-Bridge through the ROS network, whereas IGT Test Server is a TCP/IP server that communicates with the ROS-IGTL-Bridge over the LAN using the OpenIGTLink protocol. IGTL Test Server simulates the behavior of 3D Slicer or any other surgical planning and navigation software. Both simulators work as either a sender or a receiver; when the sender role is assigned to one simulator, the receiver role is assigned to the other. The sender generates a random message with given type and message size, and sends it to the receiver via the ROS-IGTL-Bridge node. Two sets of tests were performed:

Qualitative Evaluation of Data Transfer Latency. We measured the data transfer latency while streaming the messages from the sender to the receiver at 30 frames per second (fps). Each transform message contains one linear transform that represents position and orientation. The size of each string message was fixed at 100 bytes, which is sufficient for commands for devices. For the point messages, multiple data sizes were used ranging from 1 point per message to 10000 points per message, considering different use-case scenarios including tool tracking, landmark tracing and point cloud transmission. For image messages, we consider 2D color image (RGB) in five image formats: VGA (640 × 480 pixels), SVGA (800×600 pixels), XGA (1024×768 pixels), HD (1280× 720 pixels), and Full HD (1920 × 1080 pixels).

Demonstration of High Frame Rate Data Transfer. Additionally, we tested high-frame-rate data transfer up to 1000 fps using the transform data type considering applications where sensory data (e.g. tracking sensors, encoders) are transferred between two computers over the local area network.

In both tests, the data were transferred from ROS Test Node to IGTL Test Server, and vice versa.

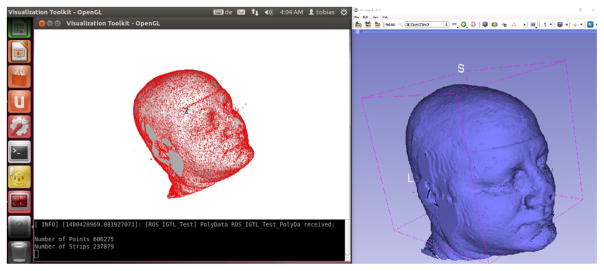

3.3 Demonstration of Polygon Data Sharing

Additionally, transfer of poly data was demonstrated using the set up. For this qualitative evaluation, a simulator program called the ROS-IGTL-Test node was used as a ROS node, whereas 3D Slicer was used as external software that generated a 3D poly data model based on MRI data. The ROS-IGTL-Test node comes with the ROS-IGTL-Bridge software for testing purposes with a 3D model of the human head. After setting up the connection parameters in the file test.launch, the ROS-IGTL-Bridge and the integrated Open-IGTLinkIF module in 3D Slicer established a connection and subsequently, exchanged the poly data message.

3.4 Results

The mean and standard deviation latency for 1000 frames were shown in Table 1. There were cases where some of the messages were not delivered because the data transfer latency is larger than the interval of message transfers. During the measurement, the clock offset between the two computers was maintained at 0.00 ± 0.28 milliseconds (mean ± SD).

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations (SD) of message transfer latency for transform, point, string, and image messages based on measurements in 1000 message transfers.

| Message Type | From ROS Test Node to IGTL Test Server (milliseconds) | From IGTL Test Server to ROS Test Node (milliseconds) |

|---|---|---|

| Transform | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.4 |

| String (100 bytes) | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.4 |

| Point (1 point) | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.4 |

| Point (10 points) | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.5 |

| Point (100 points) | 17.2 ± 12.6 | 3.8 ± 5.4 |

| Point (1000 points) | 24.8 ± 12.3 | 20.9 ± 26.7 |

| Image (VGA) | 25.2 ± 4.3 | 23.6 ± 3.5 |

| Image (SVGA) | 33.6 ± 4.6* | 33.6 ± 3.7* |

| Image (XGA) | 58.8 ± 10.6* | 58.5 ± 6.0* |

| Image (HD) | 76.3 ± 10.5* | 67.2 ± 6.1* |

| Image (Full HD) | NA* | 144.5 ± 12.2* |

The asterisks (*) indicate that some of the messages were not delivered to the recipient.

For the demonstration of High Frame Rate Data Transfer, the transform messages were transferred from the ROS Test Node to the IGTL Test Server at 1000 fps successfully. When the messages were transferred in the other direction, the data transfer was successful up to 900 fps.

In the additional demonstration of poly data transfer, the poly data model consisting of more than 600 thousand points and 230 thousand faces was successfully transferred from ROS to 3D Slicer and vice versa. The transferred poly data were successfully visualized in both environments (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Exchanged vtkPolyData model generated from sample data visualized in the vtkRenderWindow on the ROS side (left) and in comparison in the 3D Slicer scene (right).

4 Use Cases

4.1 Rapid Prototyping/Educational Platform for IGT

A proof-of-concept image-guided manipulator system was prototyped using 3D Slicer, ROS, and Lego Mindstorms EV3. Lego Mindstorms has been used for IGT-related projects in the context of education [22] as well as hardware/software testing platform [23]. The goal of this project was two-fold: (1) create a brainstorming tool for medical robotics with a scalable software system that facilitates the seamless conversion from prototypes into research- and commercial-grade systems ; and (2) create an educational tool for students, engineers, and scientists to learn image-guidance and medical robotics.

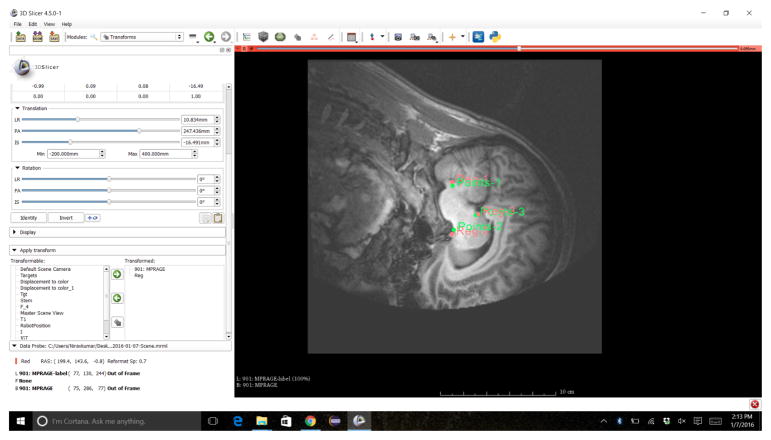

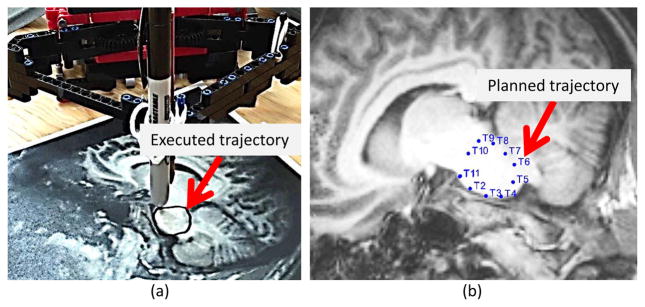

The system mimics a surgical robot that actuates its end-effector to follow a trajectory in the physical space defined on a 3D medical image (e.g. CT, MRI) on surgical navigation software. The process can be monitored through 3D graphics. The system consists of an active 3-degree-of-freedom (DoF) parallel-link manipulator, control brick, ROS master computer, and navigation computers that ran the ROS master server and navigation software, 3D Slicer. The control computer module (Lego EV3 Programmable Brick) communicates with the navigation software via a ROS master server over the wireless network. We performed a mock procedure using an MR image of the brain, and a 2D phantom created from the image. The manipulator was registered to the phantom by recording the coordinates of predefined landmarks by physically touching them with its end-effector, and match them with the corresponding points on the image (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12.

Matching defined and physical landmarks on the 2D sample data using point registration algorithm in 3D Slicer.

Afterwards the drawing process on the 2D phantom was executed (Fig. 13a) using previously defined trajectory points transferred to the control brick from 3D Slicer (Fig. 13b). This mock procedure demonstrated that this Lego-based system can be used to build a robotic system with research- or commercial-grade architecture and mimic a realistic clinical workflow, making it an ideal tool for rapid prototyping and education.

Fig. 13.

A robotic arm built with Lego Mindstorms is following a trajectory on the 2D phantom (a) that was previously planned in 3D Slicer (b) after a successful image-to-patient registration.

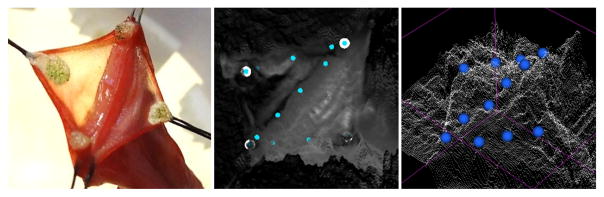

4.2 Autonomous Suturing with KUKA LWR

The goal was to test the feasibility of the ROS-IGTL-Bridge for planning and guiding autonomous surgical robots. Using the developed ROS-IGTL-Bridge, we started to improve the software system for the smart tissue autonomous robot (STAR), which uses the KUKA LWR robot. STAR consists of a robotic suturing tool based on a commercially available laparoscopic Endo360° (EndoEvolution, Raynham) tool, custom control implemented using ROS for graphical user interface (GUI) and camera integration, and open robot control software (OROCOS) for real-time control [11,24]. While we demonstrated superior consistency and burst pressure using STAR, 42.2% of all sutures required manual operator adjustments, leading to longer procedure times compared to manual and teleoperated robotic surgery [7]. Most missed suture placements requiring operator adjustments were caused by noisy point cloud data from the plenoptic camera, in particular along the depth axis, that was not apparent on the two dimensional suture plans provided by ROS. By upgrading STAR with the ROS-IGTL-Bridge we were able to transfer 3D point clouds from STAR to Slicer for point cloud visualization (Fig. 14). This could lead to improve the workflow for 3D planning of suture locations, greater autonomy and shorter procedure times.

Fig. 14.

Picture of porcine bowel staged for anastomosis (left), current STAR suture plan (middle), and suture plan using 3D Slicer enabling 3D adjustments (right).

5 Discussion

In this work a ROS-IGTL-Bridge node was implemented to extend ROS by a generic open network interface based on the OpenIGTLink protocol. This interface enabled seamless sharing of data frequently used in IGT applications, including strings, transforms, points, poly data, and images, between the ROS-based system and external medical image computing platforms. Conversion methods for the matching message types were generated to ensure compatibility. While the OpenIGTLink protocol provides two distinct message types for transmitting linear transforms, namely TRANSFORM and TDATA, we chose to use TRANSFORM in the current implementation because of its simplicity and generalness. A TRANSFORM message represents an affine transformation matrix, which can be easily converted to a ROSs geometry msgs/Transform message, and can be used for many purposes, from tool tracking to coordinate transformations. TDATA could be supported in the future, as it provides convenient features for tool tracking, such as transmission of multi-channel tracking. The created messages and conversions can be easily adapted or new message types can be additionally included to fulfill task-specific needs.

The performance of the data transfer using the ROS-IGTL-Bridge was sufficient for many real-time IGT applications. Our test demonstrated that the data transfer latency of incoming and outgoing messages at 30 frames per second was less than 1.2 ms for string, points and transform messages and 25.2 ms for images (VGA). Additionally, a high frame rate data transfer up to 900 fps was achieved for the transform message. Furthermore, large poly data models with more than 600 thousand points and 230 thousand faces were successfully exchanged. Transfer of images larger than the XGA format could not achieve full 30 fps. We are currently working on the extension of the OpenIGTLink protocol to provide video compression for better streaming performance.

The mock IGT system using 3D Slicer and Lego Mind-storm demonstrated that the ROS-IGTL-Bridge allowed building a prototype system and validate its functionality in a mock IGT procedure in a limited time. We were able to build this demo setup during the 22nd NA-MIC Winter Project Week 2016, a week-long hackathon event focused on open-source medical image computing software infrastructures [25]. The ROS-IGTL-Bridge was also demonstrated in an upscale IGT setup consisting of the industry-grade high dexterity robots with autonomous controlling system. The ROS-IGTL-Bridge’s ability to transfer point cloud data enabled incorporating advanced visualization and 3D planning of suture location offered by 3D Slicer into the system.

The study demonstrated that the ROS-IGTL-Bridge enabled cross-platform data sharing between ROS and image-guidance software with sufficient data transfer performance. The bridge benefits IGT setups by combining the specific methods such as robot control, motion planning and sensing within ROS with the image processing and visualization function set of surgical planning tools like 3D Slicer. This will allow rapid and seamless integration of advanced image-based planning/navigation offered by image-guidance software such as 3D Slicer into ROS-based surgical robot systems. By bridging two different software platforms, the researcher can benefit from state-of-the-art engineering resources developed in the different research fields, including robotics and medical image computing to develop advanced image-guided surgical robot systems.

The idea of using OpenIGTLink to bridge two research platforms has been demonstrated in several studies. In particular, OpenIGTLink has been extensively used to bridge data grabbing software and visualization/user interaction software for medical image computing research. Papademetris, Tokuda, et al used OpenIGTLink to bridge a commercial navigation system with external research platforms including 3D Slicer [19] and BioImage Suite [26]. The Image-Guided Surgery Toolkit (IGSTK) [27], an open software platform that provides connectivity with tracking and imaging devices, supported OpenIGTLink to export tracking and imaging data to other platforms such as 3D Slicer and MITK [28, 29]. More recently, Lasso et al used OpenIGTLink to bridge their data grabbing software, PLUS, with external visualization software to stream tracking and ultrasound image data [30]. Clarkson et al developed a messaging library, NiftyLink, based on OpenIGTLink to integrate data grabbing software and end-user application for visualization/user interaction [15]. Other open-source packages, such as CustusX [31], IBIS [32] and MeVisLab [18], have adapted to OpenIGTLink as well, to take advantage of existing software infrastructures available in the community.

OpenIGTLink has also been used to bridge platforms beyond the medical image computing field. A medical robotics platform, the CISST library, offers an OpenIGTLink bridge to integrate image visualization software into medical robotics applications [33]. OpenIGTLink is also used with ROS-based robotic system for laparoscopic interventions [34]. The ROS-IGTL-Bridge is a generalization of those prior works aiming to extend the successful model found in the medical image computing field, and has the potential to facilitate the sharing of engineering resource between the medical robotics and medical image computing.

The source code, instruction, and test program of the ROS-IGTL-Bridge is available as open-source software at GitHub [35]. The code can be compiled and installed with Catkin, a CMake-based build system.

Fig. 7.

Corresponding data fields in poly data messages for OpenIGT-Link and ROS-IGTL-Bridge. The considered attributes includename, points, polygons, strips, lines and vertices.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01EB020667, R01CA111288, R01EB020610, P41EB015898). The content of the material is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of these agencies. The authors thank Mr. Longquan Chen of Brigham and Women’s Hospital for his technical support. The authors also thank Ms. Christina Choi for evaluating the rapid prototyping platform with Lego Mindstorms.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

No animal or human study was performed in this study. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Tobias Frank, Institute of Mechatronic Systems, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Universität Hannover Appelstrasse 11 a, 30167 Hannover, Germany.

Axel Krieger, Sheikh Zayed Institute for Pediatric Surgical Innovation, Childrens National Health System, 111 Michigan Avenue Northwest, Washington, DC 20010, USA.

Simon Leonard, Department of Computer Science, Johns Hopkins University, 3400 North Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA.

Niravkumar A. Patel, Automation and Interventional Medicine(AIM) Laboratory, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, 100 Institute Road, Worcester, MA 01609, USA

Junichi Tokuda, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Womens Hospital and Harvard Medical School, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

References

- 1.Beasley Ryan A. Medical robots: Current systems and research directions. 2012:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trinh Quoc-Dien, Sammon Jesse, Sun Maxine, Ravi Praful, Ghani Khurshid R, Bianchi Marco, Jeong Wooju, Shariat Shahrokh F, Hansen Jens, Schmitges Jan, Jeldres Claudio, Rogers Craig G, Peabody James O, Montorsi Francesco, Menon Mani, Karakiewicz Pierre I. Perioperative outcomes of robot-assisted radical prostatectomy compared with open radical prostatectomy: results from the nationwide inpatient sample. Eur Urol. 2012 Apr;61(4):679–685. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shurrab Mohammed, Schilling Richard, Gang Eli, Khan Ejaz M, Crystal Eugene. Robotics in invasive cardiac electrophysiology. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2014 Jul;11(4):375–381. doi: 10.1586/17434440.2014.916207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Ruiter Quirina MB, Moll Frans L, van Herwaarden Joost A. Current state in tracking and robotic navigation systems for application in endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2015 Jan;61(1):256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dieterich Sonja, Gibbs Iris C. The CyberKnife in clinical use: current roles, future expectations. Front Radiat Ther Oncol. 2011 May 20;43:181–194. doi: 10.1159/000322423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moustris GP, Hiridis SC, Deliparaschos KM, Konstantinidis KM. Evolution of autonomous and semi-autonomous robotic surgical systems: a review of the literature. 7(4):375–392. doi: 10.1002/rcs.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shademan A, Decker RS, Opfermann JD, Leonard S, Krieger A, Kim PCW. Supervised autonomous robotic soft tissue surgery. 8(337):337ra64–337ra64. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad9398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quigley Morgan, Conley Ken, Gerkey Brian P, Faust Josh, Foote Tully, Leibs Jeremy, Wheeler Rob, Ng Andrew Y. Ros: an open-source robot operating system. ICRA Workshop on Open Source Software; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hannaford B, Rosen J, Friedman DW, King H, Roan P, Cheng Lei, Glozman D, Ma Ji, Kosari SN, White L. Raven-II: An open platform for surgical robotics research. 60(4):954–959. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2012.2228858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kazanzides Peter, Chen Zihan, Deguet Anton, Fischer Gregory S, Taylor Russell H, DiMaio Simon P. An open-source research kit for the da vinci® surgical system. 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); IEEE; 2014. pp. 6434–6439. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leonard Simon, Wu Kyle L, Kim Yonjae, Krieger Axel, Kim Peter CW. Smart tissue anastomosis robot (STAR): A vision-guided robotics system for laparoscopic suturing. Biomedical Engineering, IEEE Transactions on. 2014;61(4):1305–1317. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2014.2302385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fedorov Andriy, Beichel Reinhard, Kalpathy-Cramer Jayashree, Finet Julien, Fillion-Robin Jean-Christophe C, Pujol Sonia, Bauer Christian, Jennings Dominique, Fennessy Fiona, Sonka Milan, Buatti John, Aylward Stephen, Miller James V, Pieper Steve, Kikinis Ron. 3D slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative imaging network. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012 Nov;30(9):1323–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enquobahrie Andinet, Cheng Patrick, Gary Kevin, Ibanez Luis, Gobbi David, Lindseth Frank, Yaniv Ziv, Aylward Stephen, Jomier Julien, Cleary Kevin. The image-guided surgery toolkit IGSTK: an open source C++ software toolkit. Journal of digital imaging. 2007 Nov;20(Suppl 1):21–33. doi: 10.1007/s10278-007-9054-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nolden Marco, Zelzer Sascha, Seitel Alexander, Wald Diana, Müller Michael, Franz Alfred M, Maleike Daniel, Fangerau Markus, Baumhauer Matthias, Maier-Hein Lena, Maier-Hein Klaus H, Meinzer Hans Peter, Wolf Ivo. The medical imaging interaction toolkit: challenges and advances. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery. 2013;8(4):607–620. doi: 10.1007/s11548-013-0840-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarkson Matthew J, Zombori Gergely, Thompson Steve, Totz Johannes, Song Yi, Espak Miklos, Johnsen Stian, Hawkes David, Ourselin Sbastien. The NifTK software platform for image-guided interventions: platform overview and NiftyLink messaging. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery. 2015 Mar;10(3):301–316. doi: 10.1007/s11548-014-1124-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosset Antoine, Spadola Luca, Ratib Osman. OsiriX: an open-source software for navigating in multidimensional DICOM images. Journal of Digital Imaging. 2004 Sep;17(3):205–216. doi: 10.1007/s10278-004-1014-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paladini Gianluca, Azar Fred S. SPIE BiOS: Biomedical Optics. International Society for Optics and Photonics; 2009. An extensible imaging platform for optical imaging applications; pp. 717108–717108. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egger Jan, Tokuda Junichi, Chauvin Laurent, Freisleben Bernd, Nimsky Christopher, Kapur Tina, Wells William. Integration of the OpenIGTLink Network Protocol for image-guided therapy with the medical platform MeVisLab. Int J Med Robot. 2012 Sep;8(3):282–290. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tokuda Junichi, Fischer Gregory S, Papademetris Xenophon, Yaniv Ziv, Ibanez Luis, Cheng Patrick, Liu Haiying, Blevins Jack, Arata Jumpei, Golby Alexandra J, Kapur Tina, Pieper Steve, Burdette Everette C, Fichtinger Gabor, Tempany Clare M, Hata Nobuhiko. OpenIGTLink: an open network protocol for image-guided therapy environment. 5(4):423–434. doi: 10.1002/rcs.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Correll Kendall, Barendt Nick, Branicky Michael. Design considerations for software only implementations of the IEEE 1588 precision time protocol. Conference on IEEE 1588; 2005. pp. 11–15. repo.eecs.berkeley.edu. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mills David L. Internet time synchronization: the network time protocol. IEEE Transactions on communications. 1991;39(10):1482–1493. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pace D, Kikinis R, Hata N. An accessible, hands-on tutorial system for image-guided therapy and medical robotics using a robot and open-source software. 2007 Jul; [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jomier Julien, Ibanez Luis, Enquobahrie Andinet, Pace Danielle, Cleary Kevin. An open-source framework for testing tracking devices using lego mindstorms. SPIE Medical Imaging; International Society for Optics and Photonics; 2009. pp. 72612S–72612S. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leonard Simon, Shademan Azad, Kim Yonjae, Krieger Axel, Kim Peter CW. Smart tissue anastomosis robot (star): Accuracy evaluation for supervisory suturing using near-infrared fluorescent markers. Robotics and Automation, 2014. ICRA 2014. IEEE International Conference on; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.22nd NA-MIC Winter Project Week. 2016 Jan; http://www.na-mic.org/Wiki/index.php/2016_Winter_Project_Week.

- 26.Papademetris Xenophon, Jackowski Marcel P, Rajeevan Nallakkandi, DiStasio Marcello, Okuda Hirohito, Todd Constable R, Staib Lawrence H. BioImage Suite: An integrated medical image analysis suite: An update. The insight journal. 2006;2006:209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enquobahrie Andinet, Cheng Patrick, Gary Kevin, Ibanez Luis, Gobbi David, Lindseth Frank, Yaniv Ziv, Aylward Stephen, Jomier Julien, Cleary Kevin. The image-guided surgery toolkit IGSTK: an open source C++ software toolkit. Journal of Digital Imaging. 2007 Nov;20(Suppl 1):21–33. doi: 10.1007/s10278-007-9054-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu Tong, Liang Ping, Wu Wen-Bo, Xue Jin, Lei Cheng-Long, Li Yin-Yan, Sun Yun-Na, Liu Fang-Yi. Integration of the Image-Guided Surgery Toolkit (IGSTK) into the Medical Imaging Interaction Toolkit (MITK) Journal of Digital Imaging. 2012 Dec;25(6):729–737. doi: 10.1007/s10278-012-9477-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klemm Martin, Kirchner Thomas, Grhl Janek, Cheray Dominique, Nolden Marco, Seitel Alexander, Hoppe Harald, Maier-Hein Lena, Franz Alfred M. MITK-OpenIGTLink for combining open-source toolkits in real-time computer-assisted interventions. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery. 2017 Mar;12(3):351–361. doi: 10.1007/s11548-016-1488-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lasso Andras, Heffter Tamas, Rankin Adam, Pinter Csaba, Ungi Tamas, Fichtinger Gabor. PLUS: open-source toolkit for ultrasound-guided intervention systems. IEEE transactions on bio-medical engineering. 2014 Oct;61(10):2527–2537. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2014.2322864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Askeland Christian, Solberg Ole Vegard, Bakeng Janne Beate Lervik, Reinertsen Ingerid, Tangen Geir Arne, Hofstad Erlend Fagertun, Iversen Daniel Hyer, Vpenstad Cecilie, Selbekk Tormod, Lang Thomas, Nagelhus Hernes Toril A, Leira Hkon Olav, Unsgrd Geirmund, Lindseth Frank. CustusX: an open-source research platform for image-guided therapy. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery. 2016 Apr;11(4):505–519. doi: 10.1007/s11548-015-1292-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drouin Simon, Kochanowska Anna, Kersten-Oertel Marta, Gerard Ian J, Zelmann Rina, DeNigris Dante, Briault Silvain, Arbel Tal, Sirhan Denis, Sadikot Abbas F, Hall Jeffery A, Sinclair David S, Petrecca Kevin, Del Maestro Rolando F, Collins D Louis. IBIS: an OR ready open-source platform for image-guided neurosurgery. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery. 2017 Mar;12(3):363–378. doi: 10.1007/s11548-016-1478-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deguet Anton, Kumar Rajesh, Taylor Russell, Kazanzides Peter. The cisst libraries for computer assisted intervention systems. MICCAI Workshop on Systems and Arch. for Computer Assisted Interventions; Sep 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bihlmaier Andreas, Beyl Tim, Nicolai Philip, Kunze Mirko, Mintenbeck Julien, Schreiter Luzie, Brennecke Thorsten, Hutzl Jessica, Raczkowsky Jrg, Wrn Heinz. ROS-Based Cognitive Surgical Robotics. In: Koubaa Anis., editor. Robot Operating System (ROS), number 625 in Studies in Computational Intelligence. Springer International Publishing; 2016. pp. 317–342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frank Tobias. ROS-IGTL-Bridge source code GitHub repository. 2016 https://github.com/openigtlink/ros-igtl-bridge.