Abstract

Objective

This study investigated how well-suited the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision, for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics, (ICD-11 MMS) is for 2 morbidity use cases, patient safety and quality, examining the level of detail captured, and evaluating the necessity for the development of a US clinical modification (CM).

Materials and Methods

Utilizing the 5 NCVHS-specified perspectives plus the consumer perspective, a framework was created of International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) use cases. Analysis yielded candidate source criteria for use in case evaluation. Patient safety and quality were chosen because they are relevant across all perspectives.

Granularity differences and content coverage of ICD-11 MMS entities were assessed pre- and post-coordination to determine suitability for the 2 use cases. Pressure ulcers, a common condition across 3 patient safety applications, became the focus for comparing ICD-10-CM codes to ICD-11 MMS codes. For 3 electronic clinical quality measures (eCQMs), the evaluation centered on specified value sets for ischemic stroke, hypertension, and diabetes.

Results

For pressure ulcers, the ICD-11 MMS was found to exceed ICD-10-CM capabilities via post-coordinated extension codes. For the 3 eCQM value sets explored, the ICD-11 MMS fully represented the disease concepts when post-coordinated code clusters were used.

Conclusions

The examples from the patient safety and quality use cases evaluated in this study are appropriate for ICD-11 MMS. It captures greater detail than ICD-10-CM, and ICD-11 MMS specificity would benefit both use cases. The authors believe this preliminary study indicates the US should invest resources to explore adopting the WHO ICD-11 MMS and tooling and guidelines to implement post-coordination.

Keywords: International Classification of Diseases, ICD-11, ICD-10-CM, patient safety, clinical quality measures

INTRODUCTION

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) Nomenclature Regulations,1 the United States (US) as a member state is required to use the most current International Classification of Diseases (ICD) revision for mortality statistics. Adoption for morbidity is optional. In 2019, the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics (NCVHS), a statutory advisory body to the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) for health data standards, convened an ICD-11 Evaluation Expert Roundtable. One of its charges was to formulate the necessary research questions to aid in the evaluation of the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11) in order for the HHS to develop the US adoption strategy.

BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

The international disease classification has a long history dating back to 1893.2 With each revision improvements have been made to keep the classification current with medical knowledge and true to its intended purposes. On June 18, 2018 WHO released the ICD-11 signaling the next era for classifying diseases set to begin as early as January 1, 2022.3

ICD-11 consists of 2 main components. The Foundation Component comprises all of the medical entities such as diseases, disorders, injuries, signs, symptoms, and more. All of these are associated with attributes such as body site or body system. The Foundation allows an entity to have more than 1 parent, thereby supporting multiple hierarchies. A linearization (ie, a subset to address specific needs) is derived from the Foundation Component. For mortality and morbidity statistics, the WHO has developed the second main component, the ICD-11 Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (MMS) linearization.

Based on the results of the 2019 Expert Roundtable, the NCVHS submitted recommendations to the Secretary of HHS, stressing the need for research and evaluation of the ICD-11 to move forward now in order to provide a more informed decision-making process for governmental and industry stakeholders. Results from such research are expected to facilitate a smoother transition to ICD-11 than occurred with the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10).4

In addition, as ICD is an international standard, countries around the world have begun assessing ICD-11 in order to guide adoption and implementation. Key to establishing a country-specific plan and to determining whether ICD-11 MMS will be adopted or a need exists for a national extension, is a review and analysis of the current uses of ICD.5

OBJECTIVE

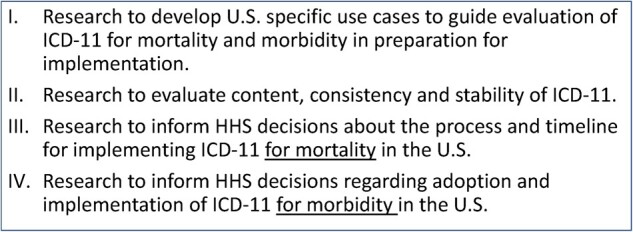

The 2019 Expert Roundtable decided on a number of research areas and questions for healthcare industry experts to explore when evaluating ICD-11 MMS. Figure 1 provides an overview of the 4 research areas identified.

Figure 1.

Overview of NCVHS ICD-11 research areas. Adapted from the December 2019 NCVHS Recommendation Letter “Prepare for Adoption of ICD-11 as a Mandated US Health Data Standard.”4

The authors selected questions from aspects of research areas I and IV to investigate, with a focus on morbidity. The questions deliberated by the authors included (1) Which uses are appropriate and which are not for ICD-11 MMS? [Area I] and (2) Is the use of ICD-11 MMS feasible for morbidity without a US clinical modification? [Area IV].4

The authors further sought to begin an investigation to inform how well-suited the ICD-11 MMS is for selected use cases by examining the following:

Whether ICD-11 MMS captures less, the same, or more level of detail than is captured in the ICD-10 Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) and, where the ICD-11 MMS offers greater specificity than ICD-10-CM, would this detail benefit the use case?

Whether ICD-11 MMS supports the use case, considering extensions and post-coordination features, without the development of a US clinical modification (CM) and, if not, what areas should be targeted in a CM?

With the exploration limited due to resource (time and money) constraints, only a small number of specific examples could be tested to address these objectives.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The NCVHS recommendations listed examples of important perspectives based on the anticipated impact of ICD-11 implementation.4 The perspectives identified in the letter were:

Health care delivery perspectives

Coverage and payment perspectives

Population health and public health perspectives

Safety perspectives

Research and evaluation perspectives

Dividing up the 5 perspectives among the authors, individual review of the current uses of ICD-10-CM was conducted by each author based on her experience and knowledge. Group discussion on the relevance of the use case to each perspective resulted in a grid listing 35 use cases and the addition of consumer perspectives to the 5 perspectives noted by NCVHS.

Next, the programs or applications for a given use case were identified independently and then discussed jointly to arrive at the pertinent source criteria to apply to a use case when determining the answers to the research questions included in this investigation. For example, in the patient safety use case, the National Quality Forum (NQF) program source criteria for serious reportable events (SREs) provide ICD-10-CM codes for adverse event reporting. For the quality use case, the Department of Health and Human Services’ electronic clinical quality measures (eCQMs) value sets provide ICD-10-CM codes for quality measures.

The matrix of the use cases and source criteria is available as a Supplementary Document. From the 6 use cases that were applicable across all 6 perspectives, 2 use cases, patient safety and quality, were chosen for more in-depth investigation to begin to evaluate how well-suited ICD-11 MMS is for these use cases. The relevant source criteria identified for these 2 use cases were used to evaluate the ICD-11 MMS as described below. Each use case was initially analyzed by 1 of the authors, with the output critically reviewed by the coauthors.

Patient safety use case

The significance of ICD-11 to quality and safety measurement was obvious from the start of its development with the formation of the Quality and Safety Topic Advisory Group (QS-TAG) and the establishment of its work plan.6 An international survey further confirmed the planned improvements to ICD-11 would meet the needs of stakeholders and result in ICD-11 being more useful for quality and safety applications.7

Recognizing the 11th revision of ICD is intended to allow for more clinical detail, the authors undertook a review of patient safety applications. This included the following:

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Hospital-Acquired Condition (HAC) Reduction Program Measures which includes Patient Safety Indicators (PSIs) and CMS Hospital-Acquired Conditions (HACs) with ties to the Present on Admission (POA) Indicator;

NQF Serious Reportable Events (SREs) (aka “Never Events”); and

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Patient Safety Component related to healthcare-associated infections (HAIs).

Definitions

The PSIs supply data that inform providers about potentially avoidable safety events where improvements in the delivery of care are possible.8 CMS defines a HAC as a condition that: (a) is high-cost or high-volume or both, (b) results in a Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) assignment with a higher payment when present as a secondary diagnosis, and (c) could reasonably have been prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines.9 NQF defines SREs as preventable events which cause or could cause significant patient harm.10 HAIs are infections that occur in a patient during the receipt of healthcare for another condition.11

Applicability of ICD-11 MMS to US patient safety applications

Each of these broad patient safety applications was analyzed in order to determine whether ICD-10-CM was used. This investigation revealed ICD-10-CM is not currently employed by the surveillance system to collect data about HAIs, but PSIs, HACs, and SREs utilize ICD-10-CM. Due to limited resources, a common disease category was sought among the PSIs, HACs, and SREs resulting in pressure ulcers being selected for detailed analysis.

Pressure ulcers, also called pressure injuries, were chosen for extensive review, as PSI 03 (Pressure Ulcer Rate), HAC 04 (Stage III and IV Pressure Ulcers), and SRE 4F (Any Stage 3, Stage 4, and unstageable pressure ulcers acquired after admission/presentation to a healthcare setting) address this condition. They are also 1 of the most common health conditions in the US and have relevance to multiple healthcare settings. More than 2.5 million individuals in the US develop pressure ulcers with about 60 000 deaths and an annual cost of $9.1–$11.6 billion per year.12 Pressure ulcers can also lead to complications, such as sepsis, cellulitis, and osteomyelitis, which result in longer hospitalizations, early mortality, and increased cost.

The ICD-10-CM codes and descriptions were extracted from PSI 03, HAC 04, and SRE 4F. PSI 0313 and SRE 4F14 include stage III or IV pressure ulcers or unstageable, and HAC 0415 includes only stage III and IV. Each code descriptor was analyzed and an ICD-11 MMS equivalent, where possible, was determined by consensus of the coauthors. A side-by-side comparison was used to pinpoint any differences from ICD-10-CM and evaluate the level of detail offered by ICD-11 MMS. The comparison was also used to gauge the level of ICD-11 MMS specificity over ICD-10-CM for potential use case benefits and to what degree extensions and post-coordination features are required. A preliminary assessment was made on whether ICD-11 MMS can support the patient safety use cases for pressure ulcers without the need to develop a US clinical modification (CM).

Quality use case

There is a growing use of eCQMs in the US to measure healthcare quality. For example, hospitals participating in the Hospital Inpatient Quality reporting (IQR) Program16 and the Medicare Promoting Interoperability Program (formerly the Meaningful Use Program)17 are required to report eCQMs. eCQMs are also used by CMS in the Quality Payment Program,18 where eligible providers must submit data for a specified number of quality measures to meet quality requirements to qualify for payment incentives and avoid penalties. A variety of other entities are using eCQMs for quality reporting, including, for example:

Accrediting bodies, such as The Joint Commission;

Commercial insurance payers in programs that reimburse providers based on quality reporting; and

Hospitals, professionals, and clinicians to provide feedback on their care systems and to help them identify opportunities for clinical quality improvement.

Definitions

In healthcare a quality measure provides a quantifiable method to evaluate the quality of care delivered by an organization or providers. “Measures are based on scientific evidence about processes, outcomes, perceptions, or systems that relate to high-quality care.”19 An electronic clinical quality measure (eCQM) is a particular type of quality measure defined specifically to use electronic data. This might include data from an electronic health record (EHR) or other type of health information technology system. An eCQM is designed to use data that is captured in a structured format during the process of patient care.20

Applicability of ICD-11 MMS to identify eCQM clinical concepts

Specifications are defined for each eCQM, describing the intent of the measure, populations included, logic, data elements, and value set identifiers.21 The value set for an eCQM specifies coded values that are allowed for the data elements within the eCQM. The value set includes a list of codes that are acceptable for a specific data element in the measure, descriptors of those codes, the code system from which the codes are derived, and the version of that code system. Today those code systems include, for example, SNOMED-CT and ICD-10-CM, among others.

To evaluate the applicability of the ICD-11 MMS for eCQMs in current use, the authors identified the conditions included in the value sets named in the specifications for select eCQMs. Due to limited resources, the authors focused on the value sets in the eCQMs included for FY2022 payment determinations in the Hospital IQR Program.22 From those included in this program, the authors selected 3 value sets that are used in multiple eCQMs and/or represent common diseases. The following 3 value sets were selected: principal diagnosis of ischemic stroke,23 diagnosis of hypertension,24 and diagnosis of diabetes.25 The conditions included in these defined value sets were then identified in ICD-11 MMS. The content coverage of ICD-11 MMS was explored to determine how using ICD-11 MMS might affect the usefulness or completeness of data captured for the eCQMs that incorporate the selected value sets. ICD-11 MMS codes for each value set were initially identified by 1 of the authors, with the results critically reviewed by the coauthors and the final relevant ICD-11 MMS codes for each value set determined by consensus after discussion.

RESULTS

The analysis of the use cases resulted in a preliminary inventory of programs utilizing ICD-10-CM. This approach enabled a basis for determining the source criteria for ascertaining whether the ICD-11 MMS is or isn’t sufficient for morbidity in the 4 comparisons examined in this limited study.

Comparison of ICD codes for patient safety initiatives

For pressure ulcers, the ICD-11 MMS with the use of post-coordination exceeds what ICD-10-CM is capable of capturing. Using a stage 3 pressure ulcer of the coccygeal region as a clinical condition, ICD-10-CM groups the coccyx and sacrum together by referring to the ‘sacral’ region. However, ICD-11 MMS has extensions for coccygeal area, sacral region, and sacrococcygeal region.

For PSI 03, HAC 04, and SRE 4F, Table 1 compares the detail found in ICD-10-CM with ICD-11 MMS and Table 2 shows how descriptors in ICD-10-CM for hip pressure ulcers compare to ICD-11 MMS. All pressure site results would be similar due to the structure of category EH90, that is, grade, site, and relevant laterality.

Table 1.

ICD-10-CM compared to ICD-11 MMS regarding pressure ulcers

| ICD-10-CM | ICD-11 MMS | |

|---|---|---|

| Terminology | Pressure ulcer stage | Pressure ulceration grade |

| Includes: bed sore, decubitus ulcer, plaster ulcer, pressure area, pressure sore | Includes: pressure injury, pressure ulcer, bedsore | |

| Description | No general description is provided but stages are explained | General and grade descriptions |

| Site | Pre-coordinated | Post-coordinated using extension |

| Broad categories | Narrow categories | |

| Laterality | Pre-coordinated | Post-coordinated using extension |

| Stage/Grade | Pre-coordinated | Pre-coordinated |

| Stage 1, 2, 3, 4 | Grade 1, 2, 3, 4 | |

| Pressure-induced deep tissue damage | Suspected deep pressure-induced tissue damage, depth unknown Ungradable | |

| Unstageable | Unspecified | |

| Unspecified stage | ||

| Diagnosis timing | Present on admission indicator | Post-coordinated using extension |

Table 2.

ICD-10-CM to ICD-11 MMS hip pressure ulcer comparison

| ICD-10-CM | ICD-10-CM descriptor | ICD-11 MMS | ICD-11 MMS descriptor |

|---|---|---|---|

| L89.200 | Pressure ulcer of unspecified hip, unstageable | EH90.5& XA4TQ2 | Pressure ulceration, ungradable, trochanteric region |

| L89.203 | Pressure ulcer of unspecified hip, stage 3 | EH90.2& XA4TQ2 | Pressure ulceration grade 3, trochanteric region |

| L89.204 | Pressure ulcer of unspecified hip, stage 4 | EH90.3& XA4TQ2 | Pressure ulceration grade 4, trochanteric region |

| L89.210 | Pressure ulcer of right hip, unstageable | EH90.5& XA4TQ2&XK9K | Pressure ulceration, ungradable, trochanteric region, right |

| L89.213 | Pressure ulcer of right hip, stage 3 | EH90.2& XA4TQ2&XK9K | Pressure ulceration grade 3, trochanteric region, right |

| L89.214 | Pressure ulcer of right hip, stage 4 | EH90.3& XA4TQ2&XK9K | Pressure ulceration grade 4, trochanteric region, right |

| L89.220 | Pressure ulcer of left hip, unstageable | EH90.5& XA4TQ2&XK8G | Pressure ulceration, ungradable, trochanteric region, left |

| L89.223 | Pressure ulcer of left hip, stage 3 | EH90.2& XA4TQ2&XK8G | Pressure ulceration grade 3, trochanteric region, left |

| L89.224 | Pressure ulcer of left hip, stage 4 | EH90.3& XA4TQ2&XK8G | Pressure ulceration grade 4, trochanteric region, left |

Comparison of ICD codes in eCQM value sets

In each of the 3 eCQM value sets explored (principal diagnosis of ischemic stroke, diagnosis of hypertension, and diagnosis of diabetes) the ICD-11 MMS was able to fully represent the disease concepts included in the value set. Interestingly, in many instances, fewer ICD-11 MMS codes are needed than ICD-10-CM codes. Also, the hierarchy within ICD-11 MMS appears to be particularly useful for the quality use case.

The defined value set for principal diagnosis of ischemic stroke contains concepts that represent patients who have had a stroke caused by ischemia, where the blood supply is restricted to an area of the brain by something like a thrombosis or an embolism. Eighty-seven of the 91 ICD-10-CM codes included in the defined value set are pre-coordinated “combination” codes that include both the cerebral infarction condition and the anatomical location (eg, the artery). For all of these codes, the pre-coordinated ICD-10-CM code would require the use of post-coordination to fully reflect the concepts in an ICD-11 MMS code cluster. Every ICD-11 MMS code would need extensions to reflect for example the anatomical location (which artery) and another extension code to reflect laterality (right, left, bilateral, unilateral, or unspecified). Notably, all of the ICD-11 MMS code clusters included a stem code from code category 8B11 (cerebral ischemic stroke).

The defined value set for diagnosis of hypertension contains concepts that indicate the patient has been diagnosed with hypertension. The ICD-10-CM codes included in the defined value set were compared to ICD-11 MMS entities with the use of post-coordination, with 2 exceptions: (1) ICD-10-CM code I27.29 (other secondary pulmonary hypertension) was not found in ICD-11 at this time; in ICD-11, there is no “other” option for secondary pulmonary hypertension. (2) Renovascular hypertension (I15.0) is also not explicitly classified as ICD-11 and does not provide an option for renal artery stenosis that is not congenital—the closest ICD-11 code is BA04.Y (other specified secondary hypertension).

As noted for ischemic strokes, ICD-10-CM has multiple pre-coordinated combination codes for hypertension that require the use of post-coordination in ICD-11 MMS to fully reflect the combined ICD-10-CM concepts. Twelve of the twenty-six ICD-10-CM codes included in the defined value set are pre-coordinated “combination” codes. Table 3 below presents a sample of ICD-10-CM codes from the diagnosis of hypertension value set and the ICD-11 MMS entities identified. In the examples of hypertensive heart disease with heart failure or with chronic kidney disease, 2 distinct ICD-11 MMS stem codes are needed to reflect both concepts.

Table 3.

ICD-10-CM and ICD-11 MMS hypertension comparison

| ICD-10-CM | ICD-10-CM descriptor | ICD-11 MMS | ICD-11 MMS descriptor |

|---|---|---|---|

| H35.031 | Hypertensive retinopathy, right eye | 9B71.1& XK9K/BA00.Z | Hypertensive retinopathy, right eye; essential hypertension unspecified |

| I10 | Essential (primary) hypertension | BA00.Z | Essential hypertension, unspecified |

| I11.0 | Hypertensive heart disease with heart failure | BA01/BD1Z | Hypertensive heart disease; heart failure, unspecified |

| I12.0 | Hypertensive chronic kidney disease with stage 5 chronic kidney disease or end stage renal disease | BA02/GB61.5 | Hypertensive renal disease; chronic kidney disease, stage 5 |

| I13.11 | Hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease without heart failure, with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, or end stage renal disease | BA01/BA02/GB61.5 | Hypertensive heart disease; Hypertensive renal disease; chronic kidney disease, stage 5 |

| I13.2 | Hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease with heart failure and with stage 5 chronic kidney disease, or end stage renal disease | BA01/BD1Z/BA02/GB61.5 | Hypertensive heart disease; heart failure, unspecified; Hypertensive renal disease; chronic kidney disease, stage 5 |

| I27.0 | Primary pulmonary hypertension | BB01.0 | Pulmonary arterial hypertension |

The defined value set for diabetes contains concepts that identify patients who have a diagnosis of diabetes. The value set includes only relevant concepts associated with identifying patients who have type 1 or type 2 diabetes and excludes patients who have gestational diabetes or steroid-induced diabetes. All but 3 of the 304 ICD-10-CM codes included in the defined value set are pre-coordinated “combination” codes that would require post-coordination in ICD-11 MMS with stem codes to reflect diabetic complications as well as extension codes to reflect laterality for example. The ICD-11 MMS greatly simplifies the effort to identify diabetes since mandatory post-coordination adds the stem code for type 1 diabetes mellitus (5A10) or type 2 diabetes mellitus (5A11) to any condition or complication associated with diabetes mellitus type 1 or 2. There is a specific ICD-11 MMS coding instruction to “always assign an additional code for diabetes mellitus.”

DISCUSSION

The comparisons of the utilization of ICD-10-CM with that of ICD 11 MMS for specific examples from the patient safety and quality use cases reveal that the ICD-11 MMS may have the necessary content and detail for use in the United States, particularly if post-coordination is applied as needed.

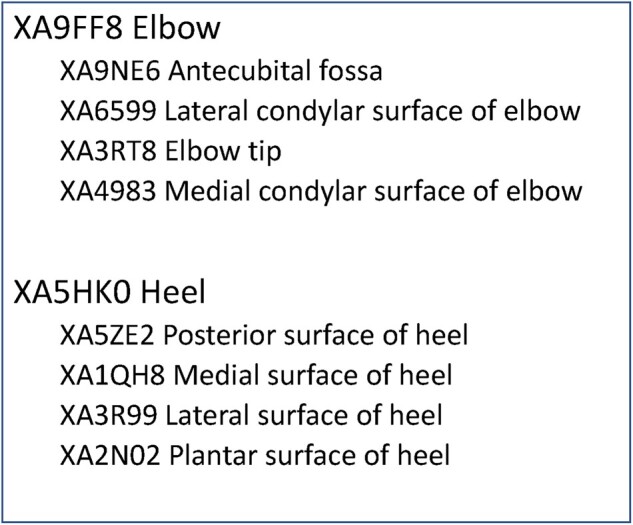

For the patient safety use case, while ICD-10-CM pre-coordinates site, laterality and stage, ICD-11 MMS pre-coordinates grade and provides greater specificity with extensions and post-coordination. For example, ICD-10-CM has limitations as only certain sites, such as elbow, back, hip, buttock, ankle, heel and head, can be described and general groupings exist (eg, sacral region includes coccyx and tailbone, upper back includes shoulder, and “other” category includes foot). ICD-10-CM’s lack of specificity may result in practitioners incorrectly labeling wound etiology which may cause problems with establishing proper care plans and increase the risk of reimbursement being withheld.26 ICD-11 MMS has greater granularity via post-coordination as many more locations are available with extensions. For example, a shoulder pressure ulcer can be specified to anterior surface, apex, or posterior surface. The ability to accurately describe location is an important element of wound assessment.26Table 4 demonstrates the outcome and supports the argument for adopting extensions through post-coordination.

Table 4.

ICD-11 MMS with and without post-coordination

| ICD-10-CM pre-coordinated term/code | ICD-11 MMS term/code with no post-coordination | ICD-11 MMS term/code with post-coordination |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure ulcer of right elbow, stage 3 | Pressure ulceration grade 3 | Pressure ulceration grade 3, elbow, right |

| L89.013 | EH90.2 | EH90.2&XA9FF8&XK9K |

| Pressure ulcer of right heel, stage 3 | Pressure ulceration grade 3 | Pressure ulceration grade 3, heel, right |

| L89.613 | EH90.2 | EH90.2&XA5HK0&XK9K |

| Pressure ulcer of right hip, stage 3 | Pressure ulceration grade 3 | Pressure ulceration grade 3, trochanteric region, right |

| L89.213 | EH90.2 | EH90.2&XA4TQ2&XK9K |

Extensions in ICD-11 MMS for elbow and heel provide for even greater specificity as to the site as represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

ICD-11 MMS extensions for elbow and heel.

For the quality use case, based on the 3 eCQM value sets investigated, the ICD-11 MMS can identify patients who have had a stroke caused by ischemia, patients diagnosed with hypertension, and patients with a diagnosis of diabetes, though not necessarily in the same manner as ICD-10-CM. Furthermore, the value set for the quality measure would be relatively easy to define with ICD-11 MMS by leveraging the hierarchy within the code system. For ischemic stroke for example, the value set could simply be defined to include all children of the ICD-11 MMS parent category (8B11) that are reported as principal diagnosis. For hypertension, the value set would include the following codes, along with any codes below them in the hierarchy: BA00, BA01, BA02, BA03, BA04. In comparison, ICD-10-CM hypertension codes are scattered in categories I11, I12, I13, I15, I27, and I67. In addition, the value set for a diagnosis of type 1 or 2 diabetes would include the ICD-11 MMS codes for type 1 diabetes (5A10) and type 2 diabetes (5A11) since these codes would be used for all patients.

In many instances, ICD-11 MMS extensions would be needed to fully reflect the concept now expressed in 1 combination code in ICD-10-CM, but for quality purposes, the extension isn’t necessarily needed. The ICD-11 MMS stem code, directly related to the condition in the value set, reflects the condition and makes it easier to capture all instances of a condition. Furthermore, this approach could simplify value set definition and maintenance via the uniform resource identifier (URI). Each ICD-11 concept has a URI that will remain stable over time and will support the use of ICD-11 APIs.

A significant problem with ICD-10-CM is that it is an administrative code set, designed in the US primarily for the billing and payment of healthcare claims.27,28 ICD-11 and the ICD-11 MMS is primarily designed to support the reporting of mortality and morbidity. ICD-10-CM is used, however, for a much broader array of purposes, beyond the reimbursement use case as our use cases show. Our analysis revealed for example, EHRs attempt to use ICD for point-of-care data capture for the patient problem list, assessments, and differential diagnoses, among others. It is also expected to enable public health surveillance for external causes of injury. However, since coding for external causes of injury are not required for payment, the codes for external causes of injury are often not reported. As an example, Makary and Daniel29 estimated that medical error was the third leading cause of death in the United States. They noted “The ICD-10 coding system has limited ability to capture most types of medical error.” It is essential the ICD system be used consistently across the world to capture all aspects of mortality and morbidity.

Fung and colleagues at the National Library of Medicine published a study in 2020 where they found that 60% of ICD-10-CM codes were represented by ICD-11 pre-coordinated codes or with post-coordination.30 The addition of a small number of extension codes was expected to result in even higher coverage. This is not necessarily surprising since ICD-10-CM is pre-coordinated. For example, the authors of this manuscript identified an estimated 15 600 ICD-10-CM codes created simply to identify laterality (right, left, bilateral, or unspecified). The authors have applied to multiple professional meetings attempting to set up workshops or discussion sessions to determine the impact on health care users. Specifically, they wish to solicit input from a variety of perspectives regarding whether and how the US regulatory and current EHR systems might need to be altered to utilize ICD-11 MMS, in particular post-coordination and the extensions.

The authors believe the previous studies, combined with their exploration of the use cases present an argument that the US should explore using the ICD-11 MMS. Furthermore, the US should investigate mechanisms to effectively use the ICD-11 MMS post-coordination feature. Should this linearization, in its current form, be found insufficient, the US should work within the WHO modification process to expand the linearization though the Foundation. Should the ICD-11 MMS linearization be inadequate for a given use case, the US could create a separate linearization. Whichever option the US decides to move forward with will result in implications for clinical, financial, and administrative applications, such as EHRs and coding tools. Other challenges include determining what constitutes consistent and accurate data and establishing the needed training.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE WORK

The limitations of this analysis include a partial examination of only 2 of the potential use cases. The analyses were conducted manually, using the WHO’s ICD-11 coding tool and browser,31 based on consensus of the authors, but have not been independently validated. Additional research should continue to more completely define the different use cases, potentially combine some areas, and refine them to identify additional criteria by which to evaluate ICD-11 MMS. More work is needed to describe the different ICD-10-CM use cases to determine the suitability of ICD-11 MMS, including more comprehensive testing of the ICD-11 MMS than was conducted for this manuscript.

CONCLUSION

The specific example from the patient safety use case reviewed here appears appropriate for ICD-11 MMS. ICD-11 MMS captures greater detail than in ICD-10-CM when post-coordination is used and the specificity of ICD-11 MMS would benefit the patient safety use case related to PSI 03, HAC 04, and SRE 4F. While only 1 condition was analyzed, the research showed a US clinical modification is unnecessary when the ICD-11 MMS extensions and post-coordination features are applied. However, post-coordination will introduce challenges for system applications, data consistency and accuracy, and training.

Similarly, the eCQMs reviewed in this use case are appropriate for ICD-11 MMS. ICD-11 MMS items uniquely identify clinical concepts, making it ideal for use in defined value sets. In contrast, the combination codes in ICD-10-CM make it more difficult to isolate clinical concepts for electronic reporting. In addition, the ICD-11 MMS hierarchical organizational schema and technical architecture, including URIs for example, facilitate identifying and maintaining comprehensive lists of codes for defined value sets.

The US should invest resources to more thoroughly explore the adoption of the WHO ICD-11 MMS linearization or a modified version of the linearization. Adopting the ICD-11 MMS or a linearization created in cooperation with WHO will have several benefits. First, ICD-11 MMS use will be more comparable across the world, an acknowledged high priority due to emerging diseases, such as COVID-19. Second, this option should be less expensive than developing a separate clinical modification. Third, by working within the WHO process for change and modification, the US will benefit from the WHO’s proposed update model, supporting a continuous evolution of the ICD over time rather than sudden changes resulting in longitudinal data discontinuities.

FUNDING

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors have all made significant contributions to the conception, design, analysis, and interpretation. They have participated in the writing and revision of the manuscript, including approving the final version.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Assembly 20. WHO nomenclature regulations 1967. 1967. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/89478 Accessed January 20, 2021.

- 2.Classification of Diseases (ICD). https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases Accessed January 20, 2021.

- 3.WHO releases new International Classification of Diseases (ICD 11). https://www.who.int/news/item/18-06-2018-who-releases-new-international-classification-of-diseases-(icd-11) Accessed January 20, 2021.

- 4.Recommendation-Letter-Preparing-for-Adoption-of-ICD-11-as-a-Mandated-US-Health-Data-Standard-final.pdf. https://ncvhs.hhs.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Recommendation-Letter-Preparing-for-Adoption-of-ICD-11-as-a-Mandated-US-Health-Data-Standard-final.pdf Accessed February 21, 2021.

- 5.IFHIMA. Whitepaper 2021 | https://ifhima.org/whitepaper-2021/Accessed February 21, 2021.

- 6. Ghali WA, Pincus HA, Southern DA, et al. ICD-11 for quality and safety: overview of the WHO Quality and Safety Topic Advisory Group. Int J Qual Health Care 2013; 25 (6): 621–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Southern DA, Hall M, White DE, et al. Opportunities and challenges for quality and safety applications in ICD-11: an international survey of users of coded health data. Int J Qual Health Care 2016; 28 (1): 129–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.AHRQ. Patient Safety Indicators (PSI) overview. https://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/Modules/psi_resources.aspx#techspecs Accessed January 21, 2021.

- 9.Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. Hospital-Acquired Conditions (Present on Admission Indicator) | CMS. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HospitalAcqCond Accessed January 21, 2021.

- 10.National Quality Forum. Phrasebook.pdf. http://public.qualityforum.org/NQFDocuments/Phrasebook.pdf Accessed February 21, 2021.

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services. Health Care-Associated Infections | health.gov. https://health.gov/our-work/health-care-quality/health-care-associated-infections Accessed January 21, 2021.

- 12.1. AHRQ. Are we ready for this change? http://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/settings/hospital/resource/pressureulcer/tool/pu1.html Accessed January 21, 2021.

- 13.Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. Patient Safety Indicators (PSI) Resources. https://qualitynet.cms.gov/inpatient/measures/psi/resources Accessed February 21, 2021.

- 14.National Quality Forum. List of SREs. https://www.qualityforum.org/Topics/SREs/List_of_SREs.aspx Accessed February 21, 2021.

- 15.Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. Statute Regulations Program Instructions | CMS. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HospitalAcqCond/Statute_Regulations_Program_Instructions Accessed February 21, 2021.

- 16.Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) program overview. https://qualitynet.cms.gov/inpatient/iqr Accessed February 21, 2021.

- 17.Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. Promoting Interoperability Programs | CMS. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms Accessed February 21, 2021.

- 18.Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. Quality Payment Program | CMS. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Payment-Program/Quality-Payment-Program Accessed February 21, 2021.

- 19.eCQI Resource Center. Glossary. https://ecqi.healthit.gov/glossary/quality-measures Accessed February 21, 2021.

- 20.eCQI Resource Center. Glossary https://ecqi.healthit.gov/glossary/e Accessed February 21, 2021.

- 21.eCQMs Resource Center. https://ecqi.healthit.gov/ecqms?qt-tabs_ecqm=3 Accessed February 21, 2021.

- 22.Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program Measures. https://qualitynet.cms.gov/inpatient/iqr/measures Accessed February 21, 2021.

- 23.US National Library of Medicine. Value Set Authority Center. https://vsac.nlm.nih.gov/valueset/2.16.840.1.113883.3.117.1.7.1.247/expansion/Latest Accessed April 24, 2020.

- 24.US National Library of Medicine. Value Set Authority Center. https://vsac.nlm.nih.gov/valueset/2.16.840.1.113883.3.600.263/expansion/Latest Accessed April 24, 2020.

- 25.US National Library of Medicine. Value Set Authority Center. https://vsac.nlm.nih.gov/valueset/2.16.840.1.113883.3.464.1003.103.12.1001/expansion/Latest Accessed April 24, 2020.

- 26.NursingCenter. Visual Guide for accurately designating the anatomic location of buttocks lesions. https://www.nursingcenter.com/journalarticle?Article_ID=3391273&Journal_ID=448075&Issue_ID=3390923 Accessed February 21, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Department of Health and Human Services. HIPAA Administrative Simplification: Modifications to Medical Data Code Set Standards To Adopt ICD-10-CM and ICD-10-PCS. 2009. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2009/01/16/E9-743/hipaa-administrative-simplification-modifications-to-medical-data-code-set-standards-to-adopt Accessed June 15, 2021.

- 28.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Code Sets Overview | CMS. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Administrative-Simplification/Code-Sets Accessed June 15, 2021.

- 29. Makary MA, Daniel M.. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ 2016; 353: i2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fung KW, Xu J, Bodenreider O.. The new International Classification of Diseases 11th edition: a comparative analysis with ICD-10 and ICD-10-CM. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020; 27 (5): 738–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.ICD-11. https://icd.who.int/en Accessed April 24, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.