What do you think?

Rate this book

336 pages, Paperback

First published November 1, 1994

She felt like everything good. She felt like the first warm gust of spring and Saturday afternoons when you’re ten years old and early summer evenings on the beach when the sand is cool and the waves are colored scotch. Her grip was fierce, her body full and soft, and her heart beat rapidly against my bare chest. I could smell her shampoo and feel the downy nape of her neck against my chin.Oh, and speaking of burning the world, Patrick and Angie have a sociopathic, "violence junkie" named Bubba (that’s right, Bubba) who does “dirty work” for them when they need it and hates everyone and everything, except the two of them. “The world according to Bubba is simple - if it aggravates you, stop it. By whatever means necessary.” Bubba doesn't get much page time in this novel but I have it from a reliable source (i.e., Kemper), that Bubba plays a major role in future stories. I can't wait.

“L.A. burns, and so many other cities smolder, waiting for the hose that will flood gasoline over the coals, and we listen to politicians who fuel our hate and our narrow views and tell us it's simply a matter of getting back to basics while they sit in their beachfront properties and listen to the surf so they won't have to hear the screams of the drowning.”Throughout the book, Lehane worked the gamut of my emotions, from anger to laughter, from outrage to compassion, from papa bear protectiveness to vengeance-seeking “kill 'em all and let the bodies fall where they may."

As I grew, so did the fires, it seemed, until recently L.A. burned, and the child in me wondered what would happen to the fallout, if the ashes and smoke would drift northeast, settle here in Boston, contaminate the air. Last summer, it seemed to. Hate came in a maelstrom, and we called it several things—racism, pedophilia, justice, righteousness—but all those words were just ribbons and wrapping paper on a soiled gift that no one wanted to open.If you haven’t checked out Lehane before, I think you should. I'm shocked I waited this long to read him, but at least I now have a whole host of his other works to enjoy.

"Once that ugliness has been forced into you, it becomes part of your blood, dilutes it, race through your heart and back out again, staining everything as it goes. The ugliness never goes away, never comes out, no matter what you do. Anyone who thinks otherwise is naive. All you can hope to do is control it, to force it all into one tight ball in one tight place and keep it there, a constant weight."

My father, a fireman, often woke me at night so I could watch the latest news footage of fires he’d fought. I could smell the smoke and soot on him, the clogging odors of gasoline and grease, and they were pleasant smells to me as I sat on his lap in the old armchair. He’d point himself out as he ran past the camera, a hazy shadow backlit by raging reds and shimmering yellows

And then there was Roland taking all that hate and ugliness and depravity that had been shoved into him since childhood at every turn, and spinning around and spewing it back at the world. Waging war against his father and telling himself that once it was done, he’d be at peace. But he wouldn’t. It never works that way. Once that ugliness has been forced into you, it becomes part of your blood, dilutes it, races through your heart and back out again, staining everything as it goes.

When I wrote my first novel, A Drink Before the War, I started with a character. That's all I had. And the character in my head was not Patrick Kenzie, the protagonist of the novel; it was his deceased father, Edgar, aka "The Hero;' a man who was, in Irish-American vernacular, a "street angel/house devil"

I created a man who was a hero fireman and, later in life, a beloved city councilor, cherished by all except his family whom he abused and tortured and generally treated in a very, very bad manner. Yet, as I wrote about him, I found myself slipping into the first-person point of view, which told me the character I was really writing about was his son. And so, in the best biblical sense, Patrick was begot by Edgar.

So, now I had this guy, a private investigator whose father was evil, yet loved by the general public. What kind of man would the son be? He'd hate hypocrisy, for one. He'd have a mistrust of politicians. He'd have a keen sense of injustice and an identification with those who are abused--by families, by government, by society in general. He would also, logic told me, have his father's temper. And maybe, I told myself, he'd be a bit self-righteous; he'd have a lot of anger, and anger often turns into self-righteousness.

OK. I had my character. What kind of case would explicate him?

He gets hired by politicians to find a cleaning woman who, it turns out, is being sought for far different reasons than the ones Patrick was given. When she dies, he realizes he's been used not only to find her but also to lead her to the spot of her assassination.

He also discovers she has an abused son, who's grown into a feared gang leader locked in a death struggle with his father, who's in bed with the politicians. And because Patrick is white and caught in the middle of a black-on-black gang war, he also has to (involuntarily) confront his own racism. And the result isn't one he'd have necessarily hoped for.

The process of defining my main character ultimately led me into the core of what my novel was about: race warfare as class warfare; violence as a multigenerational disease; white-collar crime as a far more insidious transgression than blue-collar crime; child abuse as a hamster wheel from which no one-victim or victimizer--can vacate once they've stepped on and started pedaling.

And all of this--along with some hopefully whizz-bang shoot-outs, car chases, betrayals and unmaskings-stemmed from one character. Who begot another. Who begot another.

His slim hands twitched constantly by his sides, as if grasping for the trigger of a gun. He was wearing a simple black suit with white shirt and black tie, but it was expensive material silk, I guessed.

The boys behind him were dressed exactly the same, their suits of varying quality, deteriorating steadily the farther back they stood from Socia and the grave. There were at least forty of them, the whole group in a taut, structured formation behind its leader. A conspicuous air of Spartan devotion. None of them, except Socia, looked much over seventeen, and some didn’t look old enough to have had an erection yet. They all started beyond the grave in the same direction as Socia, their eyes devoid of youth or movement or emotion, flat and clear and focused.

Once that ugliness has been forced into you, it becomes part of your blood, dilutes it, races through your heart and back out again, staining everything as it goes. The ugliness never goes away, never comes out, no matter what you do. Anyone who thinks otherwise is naive.

I looked at the grenades. Didn't have a clue what to do with them. I had the feeling that if I left the house, they'd roll off the bed, take out the entire building. I picked them up, gingerly, and put them in the fridge. Anyone broke in to steal my beer, they'd know I meant business.

Vanity and dishonesty may be vices, but they're also the first forms of protection I ever knew.

I'd been a punching bag for my father for eighteen years, and I'd never hit back. I kept believing, kept telling myself, it'll change; he'll get better. It's hard to close the door on optimistic expectations when you love someone.

I ran my hands through my hair, felt the grit and oil from the last day, smelled the trash and waste on my fingers. At that moment, I truly hated the world and everything in it.

L.A. burns, and so many other cities smolder, waiting for the hose that will flood gasoline over the coals, and we listen to politicians who fuel our hate and our narrow views and tell us it's simply a matter of getting back to basics while they sit in their beachfront properties and listen to the surf so they won't have to hear the screams of the drowning.

My gun is, as Angie would say, "not a fuck-around thing." It's a .44 magnum automatic-an "automag," they call it gleefully in Soldier of Fortune and like publications-and I didn't purchase it out of penis envy or Eastwood envy or because I wanted to own the goddamned biggest gun on the block. I bought it for one simple reason: I'm a lousy shot.

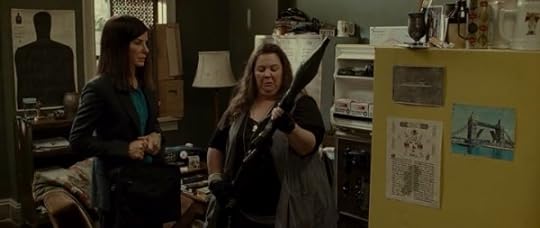

I looked at Angie again. I wasn't worried about her; I was considering what would happen to my business if my partner shot the dicks off a barful of people in Lansington. I wasn't sure, but I didn't think we'd be able to keep that office in the church.

Angie once said, "Maybe that's what love is-counting the bandages until someone says, 'Enough.'"

Maybe so.