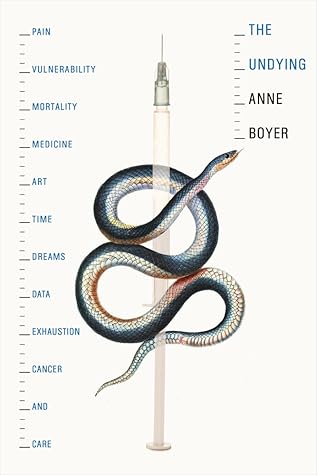

Navya's Reviews > The Undying

The Undying

by

by

“Disease is never neutral. Treatment never not ideological. Mortality never without its politics.”

This book (by one of my favorite writers) has been called a memoir, but could also be described as a poem, a series of essays, a history, or a Marxist feminist manifesto on breast cancer. I think I could write a hundred reviews of this book, each from a different perspective. I could write a review that approaches this book from the perspective of spirituality and dreams. I could write a review that approaches this book from the perspective of poetry and storytelling. But as I read this book, I kept wishing I had gotten the chance to read it for class, back when I got to spend every day discussing illness and capitalism with my classmates and professors. So I’ll write my review as a student.

As other reviews have noted, this is not a hopeful book; Boyer pushes hard against narratives of medical progress. Cancer treatment may be increasingly high-tech and expensive, but as she notes, many patients still go without “adequate pain control… physical therapy… time off work… a hospital bed to recover in or rehabilitation for the cognitive damage incurred during their treatment.” Why are our notions of progress so bound up in the romance of biotechnology, rather than these most basic and desperate needs of the sick? In Boyer’s writing, the shadow of capitalism is heavy on the clinic floor.

Boyer points out that modern science and medicine, for all their trappings of post-Enlightenment rationality, make their own assumptions and carry their own demands of faith. And she insists upon recognizing oncology’s internal debates and ambiguities, including the uncertainty of cancer’s very definition. “‘Cancer’ is a historically specific, socially constructed imprecision and not an empirically established monolith. This whole time I’ve been writing about cancer, I’ve been writing about something that scientists agree doesn’t quite exist, at least not as one unified thing.” Like schizophrenia, the diagnostic criteria for which have changed over the decades to reinforce social control, and like symptoms of nervos, which present with cultural specificity in Brazil, cancer is historically contingent and socially constructed. And while this very argument forms the basis of much work in medical anthropology and history of science, this is my first time encountering it in a patient narrative--which is just one of the many things which makes this book so special.

A significant part of the book is dedicated to the discussion of pain. Almost as soon as she introduces the subject, Boyer references Elaine Scarry’s famous claim that pain “destroys language,” and that this resistance to language makes pain a completely isolating and private experience. Boyer’s response is that “the claims about pain’s ineffability are historically specific and ideological, that pain is widely declared inarticulate for the reason that we are not supposed to share a language for how we really feel,” and that pain could have a language: it just requires the work of producing one. Although this initial argument feels perhaps a little unfair to Scarry, who does engage with a few attempts (in both medicine and art) to produce a new lexicon of pain, and who is concerned above all with the political consequences of suppressing pain’s expression, Boyer goes on to provide rebuttals I find more convincing, particularly by noting that pain is sometimes so vivid in its expression that it provokes sympathetic discomfort, and that sometimes that discomfort is so strong that it provokes continued violence.

Scarry’s work has received its fair share of arguments since it was published in 1985, and her response echoes many of these. Like Byron Good, Boyer emphasizes that pain can actually inspire a great degree of articulate expression, and like Julie Livingston, she argues that it is a lie to say “that we are always alone in pain,” which can be a social experience. Again, however, the fact that this is also a patient narrative adds another layer to the argument. Her eloquence in describing pain functions itself as evidence against the idea that pain destroys language. If Scarry herself were to read Boyer’s writing on the experience of pain, surely she would have to be convinced.

One of the most powerful things about this book is Boyer’s thorough refusal to embody the role of the idealized cancer patient, or the idealized sufferer more generally. She is incredibly intentional about this, writing of her fear that with this memoir she might “turn the pain into a product,” or tell “a lie in service of the way things are,” or “propagandize for the world as it is.” This review is getting super long, so suffice it to say that this book could never be accused of doing those things. It is deeply honest, anti-commercial, and at odds with both ease and power every step of the way (as she writes at one point, a beautiful book against beauty). It is defiant of and angry at the expectations that patients manage their disease with positivity and deference to the healthy, that they make normality their goal or standard, that they sacrifice their autonomy and self-respect, that they ally themselves with the living at the expense of the dead.

Gonna close with this quote that I want to tattoo on my forehead:

“What a relief to have not been protected, I decided, to not be a subtle or delicate person whose inner experience is made only of taste and polite feeling; what a relief not to collect tiny wounds as if they are the greatest injuries while all the rest of the world always, really, actually bleeds. It’s yet another error in perception that those with social protection can look at those who have at times lacked it, and imagine that weakness is in the bleeder, not those who have never bled. Those who diminish the beauty and luxury of survival must do so because they have been so rarely almost dead.”

This book (by one of my favorite writers) has been called a memoir, but could also be described as a poem, a series of essays, a history, or a Marxist feminist manifesto on breast cancer. I think I could write a hundred reviews of this book, each from a different perspective. I could write a review that approaches this book from the perspective of spirituality and dreams. I could write a review that approaches this book from the perspective of poetry and storytelling. But as I read this book, I kept wishing I had gotten the chance to read it for class, back when I got to spend every day discussing illness and capitalism with my classmates and professors. So I’ll write my review as a student.

As other reviews have noted, this is not a hopeful book; Boyer pushes hard against narratives of medical progress. Cancer treatment may be increasingly high-tech and expensive, but as she notes, many patients still go without “adequate pain control… physical therapy… time off work… a hospital bed to recover in or rehabilitation for the cognitive damage incurred during their treatment.” Why are our notions of progress so bound up in the romance of biotechnology, rather than these most basic and desperate needs of the sick? In Boyer’s writing, the shadow of capitalism is heavy on the clinic floor.

Boyer points out that modern science and medicine, for all their trappings of post-Enlightenment rationality, make their own assumptions and carry their own demands of faith. And she insists upon recognizing oncology’s internal debates and ambiguities, including the uncertainty of cancer’s very definition. “‘Cancer’ is a historically specific, socially constructed imprecision and not an empirically established monolith. This whole time I’ve been writing about cancer, I’ve been writing about something that scientists agree doesn’t quite exist, at least not as one unified thing.” Like schizophrenia, the diagnostic criteria for which have changed over the decades to reinforce social control, and like symptoms of nervos, which present with cultural specificity in Brazil, cancer is historically contingent and socially constructed. And while this very argument forms the basis of much work in medical anthropology and history of science, this is my first time encountering it in a patient narrative--which is just one of the many things which makes this book so special.

A significant part of the book is dedicated to the discussion of pain. Almost as soon as she introduces the subject, Boyer references Elaine Scarry’s famous claim that pain “destroys language,” and that this resistance to language makes pain a completely isolating and private experience. Boyer’s response is that “the claims about pain’s ineffability are historically specific and ideological, that pain is widely declared inarticulate for the reason that we are not supposed to share a language for how we really feel,” and that pain could have a language: it just requires the work of producing one. Although this initial argument feels perhaps a little unfair to Scarry, who does engage with a few attempts (in both medicine and art) to produce a new lexicon of pain, and who is concerned above all with the political consequences of suppressing pain’s expression, Boyer goes on to provide rebuttals I find more convincing, particularly by noting that pain is sometimes so vivid in its expression that it provokes sympathetic discomfort, and that sometimes that discomfort is so strong that it provokes continued violence.

Scarry’s work has received its fair share of arguments since it was published in 1985, and her response echoes many of these. Like Byron Good, Boyer emphasizes that pain can actually inspire a great degree of articulate expression, and like Julie Livingston, she argues that it is a lie to say “that we are always alone in pain,” which can be a social experience. Again, however, the fact that this is also a patient narrative adds another layer to the argument. Her eloquence in describing pain functions itself as evidence against the idea that pain destroys language. If Scarry herself were to read Boyer’s writing on the experience of pain, surely she would have to be convinced.

One of the most powerful things about this book is Boyer’s thorough refusal to embody the role of the idealized cancer patient, or the idealized sufferer more generally. She is incredibly intentional about this, writing of her fear that with this memoir she might “turn the pain into a product,” or tell “a lie in service of the way things are,” or “propagandize for the world as it is.” This review is getting super long, so suffice it to say that this book could never be accused of doing those things. It is deeply honest, anti-commercial, and at odds with both ease and power every step of the way (as she writes at one point, a beautiful book against beauty). It is defiant of and angry at the expectations that patients manage their disease with positivity and deference to the healthy, that they make normality their goal or standard, that they sacrifice their autonomy and self-respect, that they ally themselves with the living at the expense of the dead.

Gonna close with this quote that I want to tattoo on my forehead:

“What a relief to have not been protected, I decided, to not be a subtle or delicate person whose inner experience is made only of taste and polite feeling; what a relief not to collect tiny wounds as if they are the greatest injuries while all the rest of the world always, really, actually bleeds. It’s yet another error in perception that those with social protection can look at those who have at times lacked it, and imagine that weakness is in the bleeder, not those who have never bled. Those who diminish the beauty and luxury of survival must do so because they have been so rarely almost dead.”

Sign into Goodreads to see if any of your friends have read

The Undying.

Sign In »

Reading Progress

Started Reading

July 6, 2020

–

Finished Reading

July 7, 2020

– Shelved