Introduction

Falling is a normal part of the way a child develops – learning to walk, climb, run, jump and explore the physical environment. Fortunately, most falls are of little consequence and most children fall many times in their lives without incurring damage, other than a few cuts and bruises. All the same, some falls are beyond both the resilience of the human body and the capacity of the contact surface to absorb the energy transferred. Falls are thus an important cause of childhood injuries, including those resulting in permanent disability or death. Falls of this degree of seriousness are not randomly distributed, either globally or within single countries. To understand why this should be one needs to examine the built environment and the social conditions in which children live.

This chapter focuses on the main ideas underlying the prevention of unintentional falls in childhood, using a public health approach. The extent and characteristics of the problem are first identified and after that the types of exposure that are linked to a risk of injury. Intervention strategies to prevent such injuries and their disabling consequences are examined for their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Finally, consideration is given as to how the most promising strategies can be successfully implemented on a wider scale.

Falls have been defined and recorded in sever always. This chapter adopts the World Health Organization’s definition, according to which falls are “an event which results in a person coming to rest inadvertently on the ground or floor or other lower level” (2). In the WHO database of injuries, fall-related deaths and non-fatal injuries exclude those due to assault and intentional self-harm. Injuries and deaths resulting from falls from animals, burning buildings and vehicles, as well as falls into water and machinery, are also not coded as falls. Instead, they are recorded, respectively, as injuries due to animals, fire, transport, submersion and machinery.

An expert group convened by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development defined falls as an external cause or type of exposure, the impact of which is “to come down by force of gravity suddenly; to tumble, topple, and forcibly lose balance” (3). The group listed the main factors relating to falls in childhood. These included:

- –

social and demographic factors, such as the child’s age, gender, ethnicity and socioeconomic status;

- –

the physical development of the child;

- –

activity taking place before the fall – such as running, walking or climbing;

- –

the location of the fall;

- –

the height from which the fall occurs;

- –

characteristics of the surfaces with which contact is made – such as texture, smoothness and deformability.

All this information, if available, taken together with information on risk factors, can provide valuable clues as to how and why fall-related injuries occur, and greatly help efforts to prevent them.

Epidemiology of falls

According to the WHO Global Burden of Disease project for 2004, an estimated 424 000 people of all ages died from falls worldwide. Although the majority of fall-related deaths were among adults, they ranked as the twelfth leading cause of death among 5 to 9-year-olds and 15 to 19-year-olds (see Table 1.1 in Chapter 1). Morbidity from falls is much more common and represents a significant burden on health-care facilities around the world. Among children under 15 years, non-fatal falls were the 13th leading cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost. In most countries, falls are the most common type of childhood injury seen in emergency departments, accounting for between 25% and 52% of assessments (4, 5).

The published literature on the incidence and patterns of fall-related injuries among children relates largely to high-income countries, where just 10% of the world’s children live. In many of these countries, deaths from all types of injury are estimated to have dropped by over 50% over the past three decades (6, 7).

A systematic review of the literature from mainly low-income and middle-income countries in Africa, Asia and Central and South America on the incidence of unintentional childhood falls resulting in death or needing medical care, found the following.

- In Africa, the median incidence of falls among children and youth aged less than 22 years was 41 per 100 000 population (8).

- In Asia, the median incidence was 170 per 100 000 population aged less than 18 years (43% of all injuries).

The UNICEF–TASC surveys have also found falls to be a leading cause of morbidity and disability in children, resulting in high social and economic costs (15).

The studies reviewed suggest a substantial variability in the incidence of falls between regions – and sometimes within regions. In the absence of a common methodology and standard definition, however, data from different studies and settings cannot be compared directly and are potentially misleading. Less than a fifth of the studies documented deaths due to falls, only 12% used standardized or formal definitions for falls, and none provided reliable data on the severity of injuries or consequent disability resulting.

Mortality

In 2004, nearly 47 000 children and youth under the age of 20 years died as a result of a fall. Fall-related mortality data compiled by WHO reveal important differences between regions, and between countries within regions (see Figure 5.1). High-income countries in the Americas, Europe and Western Pacific regions had average mortality rates of between 0.2 and 1.0 per 100 000 children aged less than 20 years. However, low-income and middle-income countries in the same regions reported rates up to three times higher. Low-income and middle-income countries in South-East Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean regions had the highest average rates – of 2.7 per 100 000 and 2.9 per 100 000, respectively. While it is quite possible that the levels are so much higher in some places, it is also possible that some misclassification of data has occurred. Child abuse, for instance, is sometimes wrongly classified in the category of falls (16, 17).

FIGURE 5.1

Fatal fall-related injury rates per 100 000 childrena by WHO region and country income level, 2004. a These data refer to those under 20 years of age. HIC = High-income countries; LMIC = low-income and middle-income countries.

Age

In high-income countries, the average fall mortality rates, by age, are similar over the first 20 years of life. However, in low-income and middle-income countries, infants less than one year of age have very high rates (see Figure 5.2).

FIGURE 5.2

Fatal fall-related injury rates per 100 000 children by age and country income level, World, 2004. HIC = High-income countries; LMIC = low-income and middle-income countries. Source: WHO (2008), Global Burden of Disease: 2004 update.

Community surveys conducted in Asia highlight the high incidence of fall deaths in the region. In Bangladesh, the overall fall mortality rate for the 0–17-year age group was 2.8 per 100 000 (1), and falls were the second leading cause of death through injury among infants aged less than one year (24.7 per 100 000 population). In Viet Nam, falls were the sixth leading cause of childhood death (4.7 per 100 000 aged 0–17 years) (18). In Jiangxi province in China, falls were the fourth leading cause of death (3.1 per 100 000 aged 0–17 years). Higher rates were reported in rural areas than in urban areas (19).

Falls are still an important cause of death in children in high-income countries, even though the incidence rates are considerably less than in low-income and middle-income countries. Falls are the fourth leading cause of trauma deaths in childhood in the United States (20) and the sixth leading external cause of death among Australian children aged 0–14 years (21).

Gender

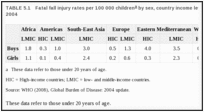

Boys are overrepresented in fall mortality statistics (see Table 5.1), with the male-to-female ratio varying from 1.2:1 (in low-income and middle-income countries in South-East Asia) to 12:1 (in high-income countries in the Eastern Mediterranean region).

TABLE 5.1

Fatal fall injury rates per 100 000 children by sex, country income level and WHO region, 2004.

Type of fall

Based on data from the Global Burden of Disease project, which includes the fourth ICD coding digit from 70 mainly middle-income and high-income Member States, 66% of fatal falls among children occurred from a height, while 8% resulted from falls on the same level. Unfortunately, the relevant information was unavailable for a quarter of the reported falls (22).

Morbidity

Extent of the problem

Global statistics on non-fatal injury are not readily available, though the incidence of non-fatal falls is clearly much higher than that of fatal cases. Data that are available indicate that falls are a leading, if not in fact the most common, type of injury resulting in hospitalization or emergency room attendance in most high-income countries (20, 23–28). Falls were also cited as the leading cause of injury among 13–15-year-olds in the Global School Health Survey, covering 26 countries (see Statistical Annex, Table A.3).

Most published studies of non-fatal injury in low-income and middle-income countries are hospital-based and may fail to capture data on children who are unable to access medical care (29, 30). Community-based studies suggest that there are many more significant fall-related injuries than just those seen at health-care facilities (14, 31).

The Asian community surveys recorded injury events that were serious enough to warrant seeking medical attention or that resulted in school days missed. Injuries not meeting these criteria were deemed insignificant in terms of health-care costs and social costs (29, 31). In the injury survey in Jiangxi province, China (19), for every one death due to a fall, there were 4 cases of permanent disability, 13 cases requiring hospitalization for 10 or more days, 24 cases requiring hospitalization for between 1 and 9 days, and 690 cases where care was sought or where at least 1 day of work or school was missed (see Figure 5.3). The survey highlighted the substantial cost of non-fatal injuries due to falls and the small proportion of cases seen in hospital settings – cases which, taken together, must contribute considerably to the overall cost of falls.

FIGURE 5.3

Inury pyramid for falls among children 0–17 years, Jiangxi province, China. Source: Reference .

Similar patterns of injury were observed in Uganda, where there were higher rates of falls among children in rural than in urban areas (32). Data from various countries in Latin America and from Pakistan also reveal that falls are a common cause of non-fatal injury among children (9, 33–36).

Globally, 50% of the total number of DALYs lost due to falls occur in children less than 15 years of age. However, the burden of childhood falls is largely explained by the morbidity and disabilities that may persist for life. The skewed distribution of this burden geographically and the relative scarcity of statistics on non-fatal injury events make it more difficult to describe and address the problem of childhood falls.

Severity of falls

The severity of a fall-related injury is determined by the anatomy of the human body and the impact force to which the body is subjected – in the absence of any special protection on the body or impact-absorbing materials in the landing or contact surfaces (37–41). The impact force itself depends, among other things, on the height from which the fall occurs. These relationships are well described in high-income countries in relation to falls from playground equipment (42–46) and from windows and roofs (47–49).

The proportions of injuries due to falls, as well as the patterns of injury from falls generally, can differ considerably in developing countries from those in developed countries (50). For instance, a recent study conducted in four low-income and middle-income countries found that falls were the leading cause of unintentional injury among children under the age of 12 years. The types of injuries sustained were largely cuts and scrapes, fractures of the upper and lower extremities and contusions. In half of all cases, the children were left with some form of disability – in 41% of cases with a temporary disability of less than six weeks (see Statistical Annex, Table C.1).

Generally, the greater the height from which a child falls, the more severe the injury (51). The Jiangxi survey found that about 18% of falls were from heights of five metres or more and two thirds involved heights of between one and five metres (19). The Jiangxi and Beijing surveys (19, 52) revealed that as children grew older, an increasing proportion of falls were from greater heights – such as trees and rooftops, frequently, in the case of adolescents. A Nigerian study, on the other hand, found that only 25% of falls in childhood leading to hospitalization were from heights, the remainder occurring at ground level (53).

Injuries from falls from heights of more than two storeys typically involve falls from windows, balconies and roofs (41, 51). Falls from stairs and trees are also common, as are falls into ditches, wells, shafts and other holes in the ground (19). Trees are particularly hazardous, especially in some tropical countries where children are employed to harvest high tree crops (50) (see Box 5.1).

In the United States, many of the fall fatalities among children involve falls from poor-quality housing in low-income urban areas, typically from the second floor or higher (51). Falls from greater heights tend to occur more in the summer months. This is presumably because windows – the usual site for falls of pre-school-age children – are more likely to be open at that time of year, and older children are more likely to be outdoors playing on fire escapes, roofs and balconies (47–49).

A case–control study from New Zealand has shown that the risk of injury in a fall from playground equipment increases dramatically for heights of over 1.5 metres (54). After adjusting for various factors such as the child’s age and weight and the presence of impact absorbing surfaces, children falling from over 1.5 metres were found to have four times the risk of injury compared to those falling from below that height. The risk of injury rose with increasing fall height, with children who fell from over 2.25 metres having 13 times the risk of injury compared to those who fell from 0.75 metres or below.

The extent to which falls from low heights result in life-threatening injuries, especially head injuries, has generated considerable controversy, largely in relation to suspected child abuse (55–57). What evidence there is on this does tend to point in the direction of possible abuse. Reported fatalities following short or minor falls are more common in situations where there are no unrelated witnesses who can confirm the history of events (55–57). When making clinical decisions, therefore, the height of a fall should not be the only criterion used to determine the threat to life that a particular injury poses (58).

Consequences of falls

Falls are the leading cause of traumatic brain injury, especially in young children, with a significant risk of long term consequences (20, 59–61). In the United States, about one third of the 1.4 million people suffering traumatic brain injuries are children aged 0 to 14 years, who have disproportionately high rates of falls compared with other age groups (62).

A Canadian study noted that 36% of infants aged less than one year presenting to an emergency department following a fall had significant head injuries, and that falls were responsible for 90% of all head injuries seen in the emergency department (20). Falls are also the most common cause of fatal and serious head injuries among children in France and the United Kingdom (63–65).

While the incidence of spinal-cord injuries following a fall is generally low, most spinal-cord injuries, resulting in quadriplegia or paraplegia, are attributed to falls (66–68). A case study from Nigeria describes the lifelong disability resulting from such injuries, often the result of falls from tall palm trees (69).

Children tend to use their arms to protect their heads when falling from a height. Limb fractures, particularly of the forearm, are therefore the most common type of fall-related injury in children beyond the age of infancy (37, 70–73). An analysis in Australia of children falling from playground equipment showed that fractures accounted for 85% of playground injuries (74). There have been suggestions that the incidence of upper limb fractures has increased in recent years, while that of serious head injuries has declined. This claim needs to be investigated further in relation to safety standards in playgrounds (75, 76).

Even after incurring open or complex fractures, children in low-income countries can make a good recovery if they receive proper care (77). All the same, permanent disfigurement and functional impairment from such fractures are frequently seen in poorer settings (5, 9, 78, 79). Growth-plate fractures are particularly liable to result in permanent disability (79). Abdominal and chest injuries are uncommon in falls from one or two storeys, but more frequent in falls from greater heights (47, 72, 80).

The UNICEF–TASC survey in Jiangxi province, China, found that falls were the leading cause of permanent disability in young people aged 0–17 years, primarily due to the long-term consequences of brain and cervical spine injury. Such disability was estimated to be 3.5 times more frequent in boys than in girls (19). A study in Nicaragua also found that falls were the leading cause of permanent disability in young people less than 15 years of age (33). In Thailand (81) and Viet Nam (18), falls accounted for 1% and 4% of the total burden of permanent disability, respectively. Permanent disability in these surveys referred to the loss of a physical sense – such as sight or hearing – loss of mobility or loss of the ability to speak. However, emotional, psychological and cognitive long term consequences were not included because of the difficulty in measuring them (19). As a result, the overall amount of permanent disability is likely to be considerably greater than the survey estimates suggest.

Cost of fall-related injury

In Canada, annual injuries from childhood falls were estimated in 1995 to cost 630 million Canadian dollars (82). Implementing strategies known to be effective is expected to result in a 20% reduction in the incidence of falls among children aged 0–9 years, 1500 fewer hospitalizations, 13 000 fewer non-hospitalized injuries, 54 fewer injuries leading to permanent disability and net savings of over C$ 126 million (US$ 120 million) every year (82).

In the United States, falls account for the largest share of the cost of deaths and injuries in children under 15 years of age – more than a quarter of all childhood unintentional injury-related costs, and costing almost US$ 95 billion in 2004 (83). For children aged 0–19 years, hospital data from 36 states suggest that the total expenditure for a case of acute care following a fall was second only to that of road traffic injury (84).

In Australia, the annual direct health-care cost of falls in children is estimated to be over 130 million Australian dollars, of which 28 million dollars is attributable to hospital inpatient care (21).

While sufficient data are not available from low-income and middle-income countries to obtain an estimate of the cost of fall-related injuries, it is clear that cost is substantial. In Lilongwe, Malawi, almost 10% of paediatric admissions were related to unintentional injuries, a third of which were as a result of fractures, generally from falls (85). An emergency department study in Turkey noted that falls accounted for 41% of injury admissions and contributed to a major part of the overall budget for paediatric trauma cases(86).The high risk of wounds becoming contaminated and of complications such as bone and joint infections, together with the scarcity of powerful antibiotics and microsurgical techniques, create significant problems for health-care services (77, 85, 87, 88). The length of paediatric hospital admissions involving osteomyelitis in a Gambian hospital, for instance, was found to be second only to that of admissions as a result of burns (88).

Limitations of data

Rates of fatalities resulting from falls are relatively low. Much of the estimated global burden of falls among children stems from subsequent disability. The lack of reliable data, in much of the world, on non-fatal outcomes is therefore a significant deficiency.

The mechanisms and patterns of fall-related injury among children are highly dependent on the context. Again, this information is generally not available for most low-income and middle-income countries – countries in which the burden of falls is the heaviest. In high-income countries, studies gathering data specifically related to the context and circumstances surrounding falls – and departing from the standard International Classification of Disease codes – have provided valuable information to help develop prevention measures.

Risk factors

As already mentioned, the incidence and patterns of fall injuries among children depend to a great extent on contextual factors. A systematic review of the published literature on risk factors for unintentional injuries due to falls in children identified age, sex and poverty as consistent independent risk factors (4). Other major risk factors influencing the incidence and severity of fall injuries were: the height of the fall; the type of surface; the mechanism (whether dropped, falling down stairs or falling using a baby walker); and the setting (whether day care or home care).

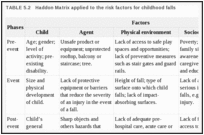

Drawing on these studies and other epidemiological findings, Table 5.2 shows the major factors influencing the incidence of unintentional childhood falls and their consequences.

TABLE 5.2

Haddon Matrix applied to the risk factors for childhood falls.

Child-related factors

Age and development

Children’s developmental stages – as well as the activities and environments associated with these stages – have a bearing on the incidence and characteristics of fall-related injuries (89, 90). Research into the ways that infants and small children learn to climb stairs (91) has found complex interactions between:

- –

their evolving motor and cognitive skills;

- –

the physical opportunities presented to them, such as access to stairs;

- –

their social opportunities or lack of them, such as strict supervision by caregivers.

Most of the falls young children have might be considered a normal part of their development and learning experience. However, their curiosity to explore their surroundings is generally not matched by their capacity to gauge or respond to danger (5, 92). As they become older and increasingly independent, they have access to a wider range of territory and are capable of a greater range of physical activity. They also often strive to perform more challenging and daring acts – a behaviour known as “risk-taking”.

In most high-income countries, children under one year of age are most likely to fall from furniture or car seats, or through being dropped. Between the ages of one and three years, children are most likely to fall from stairs or steps, baby walkers, furniture or play equipment. Older children typically fall from playground equipment or from being pushed (89, 93–95).

Evidence from low-income countries is less specific. However, a population-based study from Brazil, Chile, Cuba and Venezuela noted that falls involving young children occurred most commonly at home, though with older children, institutions, such as schools, and public places were the prime locations (9, 96). A study from three paediatric hospitals in Mexico found that falls from stairways and beds accounted for a high proportion of admissions of children under 10 years of age. The factors creating particular injury risks for these children were (34, 97): a lack of protective rails on beds (30%); unprotected staircases (48%); and easy access to roofs (40%). Falls from unprotected rooftops – on which children play as well as sleep – are common in countries such as Bangladesh, India and Turkey (98, 99).

Gender

Males outnumber females for fall-related injuries – and indeed most types of injury – among children and young people (6, 100). This is the case in most countries, and applies to both fatal and non-fatal falls (4, 37, 53, 101, 102).

The nature of childhood falls and injuries can be partly explained by patterns of child-rearing, socialization and role expectations. Risk-taking behaviour is also biologically determined. Irrespective of culture boys engage in rough play more frequently than do girls. Gender differences in the extent to which children are exposed to hazards are also common in most societies (29). Some researchers attribute proneness to injury in children to personality traits such as impulsiveness, hyperactivity, aggression and other behaviours more commonly ascribed to boys than girls (12, 103). While many psychological characteristics are indeed associated with increased risks of injury, a review of the literature suggests that the contribution of personality traits to childhood injuries is relatively small compared with that of environmental and social factors (104).

Differences in the way boys and girls are socialized by their parents were highlighted in a study examining the reactions of mothers to their child’s behaviour on the playground. The study showed that mothers responded less often and were slower to intervene in instances of risky behaviour on the part of a son than they did in the case of a daughter (105). Parental practices have also been found to foster greater exploratory behaviours among boys than among girls and to impose fewer restrictions on boys than on girls.

Poverty

A recent systematic review of risk factors for fall-related injuries among children found a strong relationship between social class and the incidence of childhood falls (4). The complex associations between social deprivation and increased risks of childhood injury have several underlying factors (5, 106–111), including:

- –

overcrowded housing conditions;

- –

hazardous environments;

- –

single-parenthood;

- –

unemployment;

- –

a relatively young maternal age;

- –

a relatively low level of maternal education;

- –

stress and mental health problems on the part of caregivers;

- –

lack of access to health care.

In some cases, poor-quality housing may be made more hazardous for falls as a result of its location. Examples of this are dwellings built on sloping sites in mountainous areas (112) and slum settlements constructed on rocky terrain (113, 114).

Underlying conditions

Despite the relative lack of data, there is evidence that children who are minimally mobile, but who are perceived by a caregiver as immobile on account of their disability, are at increased risk for falling from a bed or other elevated surface (92). The presence of mental disability can increase the risk of unintentional injury, including falls, by a factor of up to eight (115–117). An emergency-department study from Greece concluded that falls and concussion were more common among children with psychomotor or sensory disability than in children who were not disabled (118). Children in wheelchairs are particularly at risk, regardless of their cognitive ability, with falls estimated to account for 42% of the number of injuries among wheelchair users (92).

Agent factors

Consumer products

In surveys of product safety in high-income countries, falls – generally involving infants in the first year of life – are among the most common non-fatal injuries. Such falls are associated with pushchairs (known as strollers in North America), prams, baby walkers, high chairs, changing-tables, cots (excluding portable cots) and baby exercisers (119, 120). A study from the state of Victoria, Australia, suggests that baby bouncers (also called baby exercisers) are involved in the most severe non-fatal injuries related to products, with almost one in three injuries resulting in hospital admission. After baby bouncers, high chairs and pushchairs are the products linked to the most severe injuries from falls (120, 121).

A review of fall-related risk factors in the 0–6-year age group found that among children using bunk beds, the risk of a fall injury is greater for younger children, children from poorer families, children in newer beds, and children who fall onto non-carpeted floors (4, 122). Other reports suggest that while bunk beds and conventional beds may cause almost the same number of fall injuries among 5–9-year-olds, injuries from bunk bed falls are more severe than those from conventional bed falls as the fall is from a greater height (120).

Many products for leisure activities – such as skateboards, in-line skates, Heelys (a popular brand of shoes that convert from sports to roller shoes), ice-skates, swing ropes and trampolines – can result in fall-related injuries, particularly limb fractures, sprains and head injuries (123–129) (see Box 5.2). The European Union’s injury database has identified children’s bicycles, roller skates and swings as the three leading consumer products implicated in home and leisure activity injuries, most of which are from falls (130).

Despite the virtual absence of data on the issue, product safety is considered to be a significant problem for children in developing countries. In addition to product-related risks in occupational settings, globalization has led to the widespread use in developing countries of potentially dangerous products that are not always accompanied by the safety features or regulations generally found in developed countries. Heelys are one such case of increasing concern, as falls involving their use can result in significant head and limb fractures (124, 131, 132).

Playground equipment

Falls from playground equipment can lead to severe injuries and are commonly seen in hospital admission statistics in high-income countries (120, 133–135). A study from Victoria, Australia, found that falls from playground equipment accounted for 83% of emergency department admissions. Of these cases, 39% were related to falls from climbing equipment, 18% from slides and 14% from swings (120).

Several studies have discovered significant associations between certain structural features of playgrounds and fall injuries (45, 54, 136–139). A New Zealand study has shown that lowering the height of equipment to 1.5 metres could reduce the risk of children having to attend emergency departments following playground falls by 45% (42). Studies from Canada (45) and Greece (138) have found high risks of injury, particularly from falls, in playgrounds lacking the proper safety standards – such as having appropriate and sufficiently thick surface materials, and adequate handrails or guardrails.

Animals

Studies from several developing countries point to the increasing number of cases in recent years of children and young people presenting to hospital as a result of falling from a horse. This may be due to the growing popularity of horse riding as a recreational sport, as well as to larger numbers of children working on farms (143–145). While most injuries from falls from horses are minor ones, a study from the Netherlands estimated that up to 40% of children and adolescents treated in hospital after falling from a horse still suffered a disability four years later (146).

Animal racing also poses significant risks of childhood falls (147–150). Camel racing is a popular spectator sport, whose origins lie in the desert culture of West Asia and North Africa (150). Traditionally, race camels were ridden by young children from the family of the camel owner. In recent decades, though, migrant children as young as three or four years of age have performed as camel jockeys, sometimes trafficked for that purpose (150, 151). Falls are the commonest type of injury in camel racing, frequently resulting in head injuries, including fractures of the skull (148, 149).

Environmental factors

Physical environment

The “built environment” is a vital resource for the healthy development of children. At the same time, it is often the source for their fall-related injuries (152). Structural hazards in the built environment stem from the presence of dangerous or inappropriate features, or from the absence of protective features. Specifically, such factors include:

- –

a lack of building maintenance, particularly in low-income rented housing;

- –

design features in buildings and products that do not take account of the changing capabilities of young children such as a lack of window guards in high-rise buildings;

- –

poor lighting in buildings and in streets.

Socioeconomic environment

Inadequate adult supervision is often cited as a major contributor to childhood injuries (153, 154). The issues involved, however, are complex and cut across many of the problems facing the most vulnerable families. As described in Chapter 1, the relative developmental immaturity of children leads to their having limited ability to recognize danger and foresee the consequences of their actions if left unattended. It is therefore often regarded as axiomatic that caregivers should supervise children and know what type of injuries the children risk at different ages, so as to prevent them from incurring fall injuries (98). Parents, social workers and medical personnel are generally further agreed that pre-school-age children, in particular, should be supervised constantly to minimize the risk of injury – with any unsupervised period lasting no longer than five minutes (154).

However, despite these generally agreed “facts”, an over reliance on supervision as the only or primary approach to prevent falls among children is ill-advised, for several reasons, including the following (155–161):

- Falls can occur even with adult supervision, as has been shown in several studies in high-income countries on injuries from baby walkers.

- What a caregiver considers an adequate level of supervision may not be consistent with the epidemiological evidence.

- Economic conditions, such as poverty, unemployment and the disruption of social networks, may seriously affect the quality of supervision. In poor families, children may not only be left unsupervised, but find themselves acting as caregivers to younger siblings. Conditions in which caregivers are under stress and have conflicting demands placed on their attention are often the most hazardous. Other factors that increase children’s susceptibility to falls in poor households may include mental health problems affecting caregivers (5, 90, 160–164).

Illustrating the last point, a large urban slum in Rocinha, Brazil, was the site of a study of childhood injuries (90). Falls accounted for 66% of the injuries, an unsurprising finding given the steeply sloping terrain on which the settlement was constructed, its rocky outcrops and open drains, as well as the high levels of stress exhibited by the children’s mothers.

Several studies in high-income countries have suggested that day-care facilities may pose significant risks of injury (165, 166). A systematic review, though, found two studies that compared fall injuries in day care with those in home care. These studies showed that the risk of a fall injury among infants and young children in the home was twice the comparable risk in day-care settings (167, 168). Nonetheless, there exist great differences in conditions within day-care centres – as indeed there are within home care. A more sophisticated analysis is therefore called for, that goes beyond simple categorization of care arrangements into “home care” and “day care”.

Work environment

Child labour places children of both sexes at a significant risk of falls. This is partly because the demands placed on the children usually exceed their ability to cope, in terms of developmental skills, strength, stamina and size (169). Agriculture is also the most common setting for non-fatal serious falls resulting in disabling head and limb injuries. Particular dangers for children working in this sector include unprotected platforms; ladders and tall trees used for reaching high-growing crops; pits, wells and unlit shafts; and barns, silos and deep drainage ditches (50, 170).

Children and adolescents on farms are an important group at risk in high-income countries. Data from Canadian and United States registries found that falls accounted for 41% of injuries among children in this setting. In addition, 61% of falls from heights occurred among children who were not working but who lived on the farms (143, 171, 172).

Studies from various low-income countries suggest that falls are a common cause of serious injury for children working in the construction industry, with significant risks posed by open building sites (173–175).

Lack of treatment and rehabilitation

Community-based surveys in low-income and middle-income countries show that a significant proportion of children, including those with moderate to severe fall-related injuries, do not receive medical care. The reasons for this include: the distance to the hospital; prohibitive transport costs; and a lack of awareness on the part of the caregiver of the need for early attention (9, 19, 33, 66, 176).

The Jiangxi Injury Survey reported that many children sustaining fall injuries were either alone or with another child at the time of the injury – rather than with a caregiver. The survey also found that adult caregivers were generally unaware of basic first-aid procedures and did not know how to reach high-quality medical care (19). A Nigerian study noted that it was relatives or neighbours who managed most childhood injuries, and that less than 1% of injuries were seen by a health-care professional (177).

The risks of late recognition of intracranial haemorrhage, inadequate care of the airway, poor management of transfer between facilities, and inadequate acute trauma and rehabilitation care can profoundly influence the probabilities of survival and disability (34, 176, 178, 179). Rates of pre-hospital deaths are greater in places with less developed emergency medical services and longer periods of transfer to hospital (178). A study from the Islamic Republic of Iran found that 40% of fatalities following childhood falls occurred in pre-hospital settings, while 30% occurred in emergency departments and 30% in hospitals (66).

Interventions

The prevention of fall-related injuries among children is of paramount importance worldwide, given the large amount of resulting morbidity, the high costs of health care and the significant risk of death, particularly from head injuries. The measures employed must strike a careful balance between, on the one hand, promoting the healthy development of children – allowing them to play, explore and be physically active – and, on the other hand, recognizing the vulnerability of children living in environments designed primarily for adults.

The Child safety good practice guide (180) is one of several national or regional policy documents describing practical approaches for preventing fall-related injuries among children. The following section considers the most promising such interventions in a global context.

Engineering measures

Identifying, replacing or modifying unsafe products has been a leading strategy to prevent injuries from falls in many high-income countries. Major reductions in the incidence of childhood fall injuries have been achieved by removing or redesigning nursery furniture (see Box 5.3), playground equipment, sports and recreational equipment, and other items such as shopping carts and wheelchairs (180, 181). In some instances, a complete ban on a product has ensued. In other cases, there has been substantial modification of the original design – such as the introduction of a new braking mechanism for baby walkers (182). To be effective, such measures generally require continuous enforcement (180, 182, 183).

In some cases, sufficient evidence has accumulated from other situations for devices to be recommended to protect against fall-related injuries. Thus, despite a lack of intervention studies relating to horse riding, helmets are now recommended to reduce the risk of serious head injuries among young riders (144). All the same, studies from Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States suggest that rates of wearing helmets remain relatively low in these countries (184–186). Helmets and wrist guards are also strongly recommended for children engaging in ice skating, in-line skating and roller skating (126).

Environmental measures

Modifying the environment to make it more “child-friendly” is a passive intervention approach that benefits people of all ages. Major changes in the design and maintenance of playgrounds have substantially reduced the number of playground injuries in many high-income countries (180). Such modifications included laying rubber or bark ground surfacing of sufficient depth, and making equipment, such as slides, safer in terms of height and structure.

A community-based programme in the United States has demonstrated how modifying buildings can achieve substantial reductions in fall-related injuries among children. The “Children Can’t Fly” programme (49) (see Box 5.4), combining individual counselling and a mass media campaign with the free distribution and installation of window guards, has proved effective in cutting the incidence of falls from high-rise buildings in low-income areas. How this strategy might be transferred to other settings depends on the structure of dwellings, the resources available and other factors. However, the use of window guards in many parts of Africa and other developing regions (187) suggests that this approach might be useful, if implemented along with other measures, such as the enforcement of building regulations.

Laws and regulations

Laws can be powerful tools to reinforce the use of existing technology and influence behaviour. In New York City, following the passage of legislation requiring landlords to install window guards, a large decrease was observed in the number of fatal falls of young children from high-rise buildings (41). Since the introduction of both mandatory and voluntary standards for baby walkers in Canada and the United States, the tipping over of these items and structural failures in them appear to have become uncommon (51, 190).

Often, the potential effectiveness of promising regulatory approaches remains unclear. For example, the effectiveness of regulatory and enforcement procedures in day-care centres is still uncertain, largely because of methodological shortcomings in the evaluative studies conducted to date (139).

Even where the effectiveness of laws or regulations is clearly established, a lack of adequate enforcement may mean that a measure is not widely implemented. Despite the recognized benefits, for instance, of adopting standards for playgrounds, less than 5% of playgrounds surveyed in an Australian study were found to comply with the recommended guidelines on the depth of surface material (191).

Educational approaches

Educational and awareness-raising campaigns – particularly those conducted in isolation – have been criticized in several quarters (5, 105, 189). These criticisms have centred on the relative lack of evidence that these campaigns reduce injuries, the difficulty in changing human behaviour, and human weaknesses – such as inattention and the ability to be distracted – that undermine the potential effectiveness of “active” interventions. Critics have also pointed to the disproportionate burden of injury among poorer social groups, and the limited effect of health messages aimed at these groups.

Nevertheless, educating the parents of young children about falls is often regarded as an affordable and feasible intervention measure. An attraction of this strategy is the relative ease with which programmes can be updated with new information – such as new guidance on baby walkers (189, 192–194). An intensive community-wide programme in the United States to educate the general public and health-care workers about the dangers of infant walkers resulted in a 28% decline in the number of children presenting to emergency departments with injuries from falling down stairs related to the use of these walkers (195).

Educational campaigns, though, are generally regarded to be more beneficial when combined with other strategies, such as legislation or environmental modification. Such combined approaches often make the interventions easier to transfer to other settings, or indeed to implement in the original setting (196). A review in 2007 showed that education on safety in the home (with or without the provision of safety equipment) resulted in a 26% increase in the proportion of households with fitted stair gates. However, there was a lack of evidence that these interventions actually reduced injury rates (197). A more targeted study published in 2008 has now shown some modest reductions in fall rates (198).

In settings where the technology and resources exist, there is increasing interest in employing electronic communication to deliver safety messages, in the hope that such an approach will overcome the problems encountered by traditional methods of communication. One example was an early-childhood safety education programme delivered through a stall containing computers in a busy emergency department. This emergency department served a poor community with high levels of illiteracy. A randomized control trial suggested that the programme was successful in increasing knowledge and several types of safety behaviour. Its impact, however, on reducing injury rates is not as yet clear (199). An interesting finding was the observation that the benefits from more resource-intensive recommendations – such as to install child safety seats – depended on family income. As demonstrated in both developed and developing countries (200, 201), unless financial barriers and the particular situations of poor populations are addressed, “effective” interventions may increase, rather than decrease, disparities in the burden of injury, with the most vulnerable children being the least likely to benefit.

Combining strategies

Many intervention strategies combine several of the measures outlined above.

Home visitation programmes

Supportive home visitation programmes during early childhood have been used for a wide range of purposes. These include improvement of the home environment, family support and the prevention of behavioural problems in the children. A Cochrane review and other more recent studies have shown that home visits – including measures directed at poorer families – are effective in improving home safety and in reducing the risk of injury (202–206) and may result in modest reductions in injury rates (198, 202). More robust evaluation, though, is required in this area. The visits appear to be most effective when the information provided is targeted, age-appropriate and combined with the provision and installation of safety equipment (204–207).

Community interventions

The use of multiple strategies repeated in different forms and contexts is a powerful means to foster a culture of safety (208). The prevention of falls is commonly included among the goals of community-based programmes for reducing childhood injury (209). Measures found to be particularly effective in this context include the installation of window guards in high-rise buildings, making playgrounds safer and removing baby walkers. In the “Children Can’t Fly” programme in New York, important components were surveillance and follow-up, media campaigns and community education – as well as the provision to families with young children of free, easily-installable window guards (49).

Some programmes in developing countries have adopted the WHO Safe Communities model which includes safety audits of stairs and balcony rails, and campaigning for environmental improvements and safe recreational areas. However, good evaluations of the effectiveness of these programmes, particularly with regard to their impact on the incidence of childhood fall injuries, are still not available.

Adapting interventions

There is little evaluative evidence on interventions that can reduce the rate of falls and their consequences in developing countries (210). Many measures that have proved successful in reducing the incidence of fall injuries in developed countries are limited with regard to their feasibility and acceptability in developing countries. Nevertheless, the experience of intervention strategies in developed countries can suggest suitable programmes in poorer settings. There now exists a range of promising strategies to reduce the incidence of childhood falls in low-income and middle-income countries.

A recent overview of programmes in developed countries to prevent injuries from falls found that – other than general recommendations about greater supervision of children, interventions to reduce the height of playground equipment and appropriate ground surfacing in playgrounds – only one proven intervention was definitely transferable to developing countries (210). This was the “Children Can’t Fly” programme already mentioned, that was effective in reducing falls from high-rise buildings in a low-income community in New York City. While the materials used and the context may differ, more widespread use in developing countries of barriers (such as the window guards in the “Children Can’t Fly” programme) and safety equipment is likely not only to be effective but also affordable, feasible and sustainable. Specifically, it is reasonable to assume that reinforced construction and protective barriers around the periphery of roofs, as well as railings on stairs, can reduce the risk of falls among children. Furthermore, such measures can be strengthened by introducing and enforcing housing standards and building regulations (105, 189).

As already noted, the most effective interventions to prevent injuries related to falls from playground equipment have focused on the use of impact-absorbing materials, height restrictions on equipment and the overall design of playgrounds. While the materials may vary, the same principles apply in all countries. A study in a township in Johannesburg, South Africa, found that creating safer and improved recreational spaces and play areas for children was of prime importance for preventing injury, as well as violence, to children (211).

The effectiveness of home visitation programmes in early childhood in reducing the risk of falls and other injuries holds particular promise for low-income and middle-income countries. Many studies undertaken in high-income countries have focused on vulnerable families and used non-professional visitors (202). An exploratory study in Jordan of childhood injuries, including those from falls, has highlighted the promising nature of risk inventories prepared by health visitors (162).

Several studies from developing countries have considered the potential benefits of mass media and pamphlet campaigns (97). Others have examined home safety and injury prevention information targeted variously at parents, health-care workers, law enforcement officers, municipal officials, construction workers and policy-makers (106, 162, 212–214). Features of some of these promising programmes include:

- –

the inclusion of public safety messages that correspond to children’s cognitive and developmental stages and to their settings (97, 213);

As already noted, research has so far failed to provide convincing evidence that educational and awareness-raising campaigns, in isolation, are effective in reducing the incidence of childhood fall injuries. It is possible that this reflects inadequate data and limitations in the design of evaluations (197). On the other hand, the lack of evidence may be a result of the fact that changes in knowledge and attitudes do not necessarily create corresponding changes in injury rates. The Injury Prevention Project Safety Survey (TIPP-SS) of the American Academy of Pediatrics is a widely used educational programme in the United States that seeks to assess changes in behaviour. A recent study of TIPP-SS suggests that rather than behaviour, it is knowledge and attitudes that the survey actually measures (215). Before countries start to invest scarce resources, it is therefore important that educational campaigns that appear feasible are carefully evaluated for their ability to significantly reduce the rate of injuries.

Involving a range of sectors

It is always necessary to consider the broader social determinants that affect the incidence of childhood falls. Given the different settings and types of childhood fall, it is not surprising that prevention efforts cut across a range of sectors. For falls involving work in the agricultural sector, for example, groups involved in prevention include governmental and commercial bodies in that sector, landowners, farmers, manufacturers of equipment, occupational health workers, labour unions and community groups. Efforts to prevent falls in the home bring in municipal authorities, architects, builders, town planners, furniture designers, product manufacturers, health-care services, social services and nongovernmental organizations.

Children can incur injuries as a result of one or more of a range of factors relating to their caregivers. Such factors include poverty, ignorance, lack of control over the environment, fatigue, depression and malevolence. Agencies that might address some of these factors include those dealing with mental health and criminal justice, social service agencies, and community and nongovernmental organizations.

Conclusions and recommendations

Falls are the most common cause in many countries of injury-related hospital stays and emergency department visits involving children. Limb fractures and head injuries are common and traumatic brain injuries are most likely to result in lifelong disability. The predisposing factors and the types of fall vary considerably across different settings. Developing countries have a disproportionately high rate of fall-related injuries among children, and efforts to prevent these injuries are hampered by the lack of evaluative evidence of interventions that have been tried in these countries. Furthermore, although it is clear that the health-care sector has a pivotal role to play in preventing childhood injury, injury prevention in many countries often does not figure among the priorities for health.

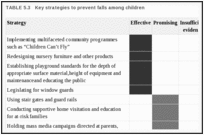

Table 5.3 summarizes the main approaches to addressing childhood falls. The most effective strategies, in all countries, are those that combine proven or promising measures.

TABLE 5.3

Key strategies to prevent falls among children.

Recommendations

From the discussion in this chapter, a number of recommendations stand out, including the following.

- Countries should, where possible, develop and promote locally manufactured, cheap and effective measures to protect against childhood falls – such as window guards, roof railings and stair gates.

- Where building regulations exist, home modifications – such as the installation of window guards – should be incorporated into the regulations and enforced.

- Local authorities should address structural hazards in the built environment that pose fall risks for children, such as open drains and wells.

- Local authorities should ensure that children have access to safe playgrounds and recreational spaces – thereby encouraging physical activity while at the same time reducing the risk of fall-related injury.

- Parental supervision is an important aspect of prevention, particularly when combined with other interventions.

- Acute care and rehabilitation should be available and devised appropriately for children, so as to minimize the long-term consequences of falls and prevent long term disability.

- Community-based injury surveys that extend beyond assessments at health-care facilities are needed to obtain epidemiological data on fall injuries in low-income and middle-income countries. Data on the characteristics of injuries and the associated risk factors are of special importance. This research should help identify, for a given setting, the five leading causes and types of childhood fall injuries and point to the most cost-effective prevention strategies.

- Large-scale evaluation studies of interventions for reducing the incidence of childhood fall injuries and their consequences urgently need to be undertaken in low-income and middle-income countries.

References

- 1.

- Rahman A, et al. Bangladesh health and injury survey report on children. Dhaka: Institute of Child and Mother Health; 2005.

- 2.

- Falls. Geneva: World Health Organization; [20 March 2008]. Violence and Injury Prevention and Disability Department. http://www

.who.int/violence _injury_prevention /other_injury/falls/en/index.html. - 3.

- Christoffel KK, et al. Standard definitions for childhood injury research: excerpts of a conference report. Pediatrics. 1992;89:1027–1034. [PubMed: 1594342]

- 4.

- Khambalia A, et al. Risk factors for unintentional injuries due to falls in children aged 0–6 years: a systematic review. Injury Prevention. 2006;12:378–385. [PMC free article: PMC2564414] [PubMed: 17170185]

- 5.

- Bartlett SN. The problem of children’s injuries in low-income countries: a review. Health Policy and Planning. 2002;17:1–13. [PubMed: 11861582]

- 6.

- Morrison A, Stone DH. Unintentional childhood injury mortalityin Europe 1984–93: are port from the EURORISC Working Group. Injury Prevention. 1999;5:171–176. [PMC free article: PMC1730528] [PubMed: 10518262]

- 7.

- A league table of child deaths by injury in rich countries. Florence: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre; 2001. [22 January 2008]. (Innocenti Report Card No. 2) http://www

.unicef-icdc .org/publications/pdf/repcard2e.pdf. - 8.

- Hyder AA, et al. Falls among children in the developing world: a gap in child health burden estimations? Acta Paediatrica. 2007;96:1394–1398. [PubMed: 17880412]

- 9.

- Bangdiwala SI, et al. The incidence of injuries in young people: I. Methodology and results of a collaborative study in Brazil, Chile, Cuba and Venezuela. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1990;19:115–124. [PubMed: 2351505]

- 10.

- Del Ciampo LA, et al. Incidence of childhood accidents determined in a study of home surveys. Annals of Tropical Paediatrics. 2001;21:239–243. [PubMed: 11579863]

- 11.

- Savitsky B, et al. Variability in pediatric injury patterns by age and ethnic groups in Israel. Ethnicity and Health. 2007;12:129–139. [PubMed: 17364898]

- 12.

- Bener A, Hyder AA, Schenk E. Trends in childhood injury mortality in a developing country: United Arab Emirates. Accident and Emergency Nursing. 2007;15:228–233. [PubMed: 17920269]

- 13.

- Evbuomwan I. Paediatric trauma admissions in the Sakaka Central Hospital, Al-Jouf Province, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 1994;15:435–437.

- 14.

- Bener A, et al. A retrospective descriptive study of pediatric trauma in a desert country. Indian Pediatrics. 1997;34:1111–1114. [PubMed: 9715557]

- 15.

- Linnan M, et al. Child mortality and injury in Asia: survey results and evidence. Florence: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre; 2007. [21 January 2008]. http://www

.unicef-irc .org/publications/pdf/iwp_2007_06.pdf. - 16.

- Overpeck MD, McLoughlin E. Did that injury happen on purpose? Does intent really matter? Injury Prevention. 1999;5:11–12. [PMC free article: PMC1730446] [PubMed: 10323563]

- 17.

- Cheng TL, et al. A new paradigm of injury intentionality. Injury Prevention. 1999;5:59–61. [PMC free article: PMC1730445] [PubMed: 10323572]

- 18.

- Linnan MJ, et al. Vietnam multicentre injury survey. Hanoi: Hanoi School of Public Health; 2003.

- 19.

- Jiangxi injury survey: child injury report. Jiangxi: Jiangxi Center for Disease Control, The Alliance for Safe Children, UNICEF–China, Jiangxi Provincial Health Bureau, Chinese Field Epidemiology Training Program; 2006.

- 20.

- Pickett W, et al. Injuries experienced by infant children: a population-based epidemiological analysis. Pediatrics. 2003;111:e365–370. [PubMed: 12671153]

- 21.

- Steenkamp M, Cripps R. Child injuries due to falls. Adelaide: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2001. (Injury Research and Statistics Series, No. 7).

- 22.

- WHO mortality database: tables. Geneva: World Health Organization; [21 April 2008]. http://www

.who.int/healthinfo /morttables/en/index.html. - 23.

- Pickett W, Hartling L, Brison RJ. A population-based study of hospitalized injuries in Kingston, Ontario, identified via the Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program. Chronic Diseases in Canada. 1997;18:61–69. [PubMed: 9268285]

- 24.

- Agran PF, et al. Rates of pediatric injuries by 3-month intervals for children 0 to 3 years of age. Pediatrics. 2003;111:e683–692. [PubMed: 12777586]

- 25.

- Lam LT, Ross FI, Cass DT. Children at play: the death and injury pattern in New South Wales, Australia, July 1990–June 1994. Journal of Paediatric Child Health. 1999;35:572–577. [PubMed: 10634986]

- 26.

- Warrington SA, Wright CM. ALSPAC Study Team. Accidents and resulting injuries in premobile infants. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2001;85:104–107. [PMC free article: PMC1718888] [PubMed: 11466183]

- 27.

- Potoka DA, Schall LC, Ford HR. Improved functional outcome for severely injured children treated at pediatric trauma centers. Journal of Trauma. 2001;51:824–834. [PubMed: 11706326]

- 28.

- Mo F, et al. Adolescent injuries in Canada: findings from the Canadian community health survey, 2000–2001. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2006;13:235–244. [PubMed: 17345722]

- 29.

- Linnan M, Peterson P. Child injury in Asia: time for action. Bangkok: The Alliance for Safe Children (TASC) and UNICEF East Asia and Pacific Regional Office; 2004. [20 March 2008]. http://www

.unicef.org /eapro/Child_injury_issue_paper.pdf. - 30.

- El-Chemaly SY, et al. Hospital admissions after paediatric trauma in a developing country: from falls to landmines. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2007;14:131–134. [PubMed: 17510852]

- 31.

- Linnan M, et al. Child mortality and injury in Asia: an overview. Florence, UNICEF: Innocenti Research Centre; 2007. [21 January 2008]. (Innocenti Working Paper 2007-04, Special Series on Child Injury No. 1). http://www

.unicef-irc .org/publications/pdf/iwp_2007_04.pdf. - 32.

- Kobusingye O, Guwatudde D, Lett R. Injury patterns in rural and urban Uganda. Injury Prevention. 2001;7:46–50. [PMC free article: PMC1730690] [PubMed: 11289535]

- 33.

- Tercero F, et al. The epidemiology of moderate and severe injuries in a Nicaraguan community: a household-based survey. Public Health. 2006;120:106–114. [PubMed: 16260010]

- 34.

- Hijar-Medina MC, et al. Accidentes en el hogar en niños menores de 10 años: causas y consecuencias. [Home accidents in children less than 10 years of age: causes and consequences]. Salud Pública de México. 1992;34:615–625. [PubMed: 1475697]

- 35.

- Fatmi Z, et al. Incidence, patterns and severity of reported unintentional injuries in Pakistan for persons five years and older: results of the National Health Survey of Pakistan 1990–94. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:152. [PMC free article: PMC1933417] [PubMed: 17623066]

- 36.

- Bachani A, et al. The burden of falls in Pakistan: the results of the 1st National Injury Survey. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University; 2007.

- 37.

- Garrettson LK, Gallagher SS. Falls in children and youth. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 1985;32:153–162. [PubMed: 3975085]

- 38.

- Mosenthal AC, et al. Falls: epidemiology and strategies for prevention. Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 1995;38:753–756. [PubMed: 7760404]

- 39.

- Buckman RF, Buckman PD. Vertical deceleration trauma: principles of management. Surgical Clinics of North America. 1991;71:331–344. [PubMed: 2003254]

- 40.

- Warner KG, Demling RH. The pathophysiology of free-fall injury. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1986;15:1088–1093. [PubMed: 3740599]

- 41.

- Barlow B, et al. Ten years of experience with falls from a height in children. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 1983;18:509–511. [PubMed: 6620098]

- 42.

- Chalmers DJ, et al. Height and surfacing as risk factors for injury in falls from playground equipment: a case-control study. Injury Prevention. 1996;2:98–104. [PMC free article: PMC1067669] [PubMed: 9346069]

- 43.

- Macarthur C, et al. Riskfactors forsevere injuries associated with falls from playground equipment. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2000;32:377–382. [PubMed: 10776854]

- 44.

- Mott A, et al. Safety of surfaces and equipment for children in playgrounds. The Lancet. 1997;349:1874–1876. [PubMed: 9217759]

- 45.

- Mowat DL, et al. A case-control study of risk factors for playground injuries among children in Kingston and area. Injury Prevention. 1998;4:39–43. [PMC free article: PMC1730314] [PubMed: 9595330]

- 46.

- Bertocci GE, et al. Influence of fall height and impact surface on biomechanics of feet-first free falls in children. Injury. 2004;35:417–424. [PubMed: 15037378]

- 47.

- Sieben RL, Leavitt JD, French JH. Falls as childhood accidents: an increasing urban risk. Pediatrics. 1971;47:886–892. [PubMed: 5573873]

- 48.

- Bergner L, Mayer S, Harris D. Falls from heights: a childhood epidemic in an urban area. American Journal of Public Health. 1971;61:90–96. [PMC free article: PMC1530622] [PubMed: 5539854]

- 49.

- Spiegel CN, Lindaman FC. Children can’t fly: a program to prevent childhood morbidity and mortality from window falls. American Journal of Public Health. 1977;67:1143–1147. [PMC free article: PMC1653830] [PubMed: 596496]

- 50.

- Barss P, et al. Injury prevention: an international perspective Epidemiology, surveillance and policy. London: Oxford University Press; 1998.

- 51.

- American Academy of Paediatrics. Falls from heights: windows, roofs and balconies. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1188–1191. [PubMed: 11331708]

- 52.

- Beijing injury survey: child injury report. Beijing: Chinese Field Epidemiology Training Program, The Alliance for Safe Children, UNICEF–China; 2003.

- 53.

- Adesunkanmi AR, Oseni SA, Badru OS. Severity and outcome of falls in children. West African Journal of Medicine. 1999;18:281–285. [PubMed: 10734792]

- 54.

- Chalmers DJ, Langley JD. Epidemiology of playground equipment injuries resulting in hospitalization. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 1990;26:329–334. [PubMed: 2073418]

- 55.

- Reiber GD. Fatal falls in childhood. How far must children fall to sustain fatal head injury? Report of cases and review of the literature. American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 1993;14:201–207. [PubMed: 8311050]

- 56.

- Chadwick DL, et al. Deaths from falls in children: how far is fatal? Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 1991;31:1353–1355. [PubMed: 1942142]

- 57.

- Williams RA. Injuries in infants and small children resulting from witnessed and corroborated free falls. Journal of Trauma. 1991;31:1350–1352. [PubMed: 1942141]

- 58.

- Goodacre S, et al. Can the distance fallen predict serious injury after a fall from a height? Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 1999;46:1055–1058. [PubMed: 10372624]

- 59.

- Abdullah J, et al. Persistence of cognitive deficits following paediatric head injury without professional rehabilitation in rural East Coast Malaysia. Asian Journal of Surgery. 2005;28:163–167. [PubMed: 16024307]

- 60.

- Hyder AA, et al. The impact of traumatic brain injuries: a global perspective. Neurorehabilitation. 2007;22:341. [PubMed: 18162698]

- 61.

- Ong L, et al. Outcome of closed head injury in Malaysian children: neurocognitive and behavioural sequelae. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 1998;34:363–368. [PubMed: 9727180]

- 62.

- Langlois JA, Rutland-Brown W, Thomas KE. Traumatic brain injury in the United States: emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2006.

- 63.

- Williamson LM, Morrison A, Stone DH. Trends in head injury mortality among 0–14 year olds in Scotland (1986–95). Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2002;56:285–288. [PMC free article: PMC1732128] [PubMed: 11896136]

- 64.

- Brookes M, et al. Head injuries in accident and emergency departments. How different are children from adults? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1990;44:147–151. [PMC free article: PMC1060624] [PubMed: 2370504]

- 65.

- Tiret L, et al. The epidemiology of head trauma in Aquitaine (France), 1986: a community-based study of hospital admissions and deaths. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1990;19:133–140. [PubMed: 2351508]

- 66.

- Zargar M, Khaji A, Karbakhsh M. Injuries caused by falls from trees in Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2005;11:235–239. [PubMed: 16532693]

- 67.

- Al-Jadid MS, Al-Asmari AK, Al-Moutaery KR. Quality of life in males with spinal cord injury in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 2004;25:1979–1985. [PubMed: 15711680]

- 68.

- Cirak B, et al. Spinal injuries in children. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2004;39:607–612. [PubMed: 15065038]

- 69.

- Okonkwo CA. Spinal cord injuries in Enugu, Nigeria: preventable accidents. Paraplegia. 1988;26:12–18. [PubMed: 3353121]

- 70.

- Kopjar B, Wickizer TM. Fractures among children: incidence and impact on daily activities. Injury Prevention. 1998;4:194–197. [PMC free article: PMC1730376] [PubMed: 9788089]

- 71.

- Rennie L, et al. The epidemiology of fractures in children. Injury. 2007;38:913–922. [PubMed: 17628559]

- 72.

- Smith MD, Burrington JD, Woolf AD. Injuries in children sustained in free falls: an analysis of 66 cases. Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 1975;15:987–991. [PubMed: 1195446]

- 73.

- Hansoti B, Beattie T. Can the height of a fall predict long bone fracture in children under 24 months? European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2005;12:285–286. [PubMed: 16276259]

- 74.

- Helps YLM, Pointer SC. Child injury due to falls from playground equipment, Australia 2002–04. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2006.

- 75.

- Ball DJ. Trends in fall injuries associated with children’s outdoor climbing frames. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2007;14:49–53. [PubMed: 17624011]

- 76.

- Mitchell R, et al. Falls from playground equipment: will the new Australian playground safety standard make a difference and how will we tell? Health Promotion Journal of Australia. 2007;18:98–104. [PubMed: 17663656]

- 77.

- Bach O, et al. Disability can be avoided after open fractures in Africa: results from Malawi. Injury. 2004;35:846–851. [PubMed: 15302235]

- 78.

- Mock CN. Injury in the developing world. Western Journal of Medicine. 2001;175:372–374. [PMC free article: PMC1275961] [PubMed: 11733420]

- 79.

- Dhillon KS, Sengupta S, Singh BJ. Delayed management of fracture of the lateral humeral condyle in children. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. 1988;59:419–424. [PubMed: 3421080]

- 80.

- Musemeche CA, et al. Pediatric falls from heights. Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 1991;31:1347–1349. [PubMed: 1942140]

- 81.

- Thailand injury survey: Child injury report. Bangkok: Institute for Health Research, Chulalongkorn University, The Alliance for Safe Children, UNICEF–Thailand; 2004.

- 82.

- The economic burden of unintentional injury in Canada. Toronto, ON, Smartrisk: Emergency Health Services Branch, Ministry of Health, Ontario; 1998.

- 83.

- Falls fact sheet. Washington, DC; National SAFE KIDS Campaign; 2004. [20 March 2008]. http://www

.usa.safekids .org/tier3_cd.cfm?folder_id =540&content_item_id =1050. - 84.

- Pressley JC, et al. National injury-related hospitalizations in children: public versus private expenditures across preventable injury mechanisms. Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 2007;63(Suppl):S10–S19. [PubMed: 17823577]

- 85.

- Simmons D. Accidents in Malawi. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1985;60:64–66. [PMC free article: PMC1777102] [PubMed: 3970574]

- 86.

- Gurses D, et al. Cost factors in pediatric trauma. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 2003;46:441–445. [PMC free article: PMC3211766] [PubMed: 14680351]

- 87.

- Bickler SW, Rode H. Surgical services for children in developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2002;80:829–835. [PMC free article: PMC2567648] [PubMed: 12471405]

- 88.

- Bickler SW, Sanno-Duanda B. Epidemiology of paediatric surgical admissions to a government referral hospital in the Gambia. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78:1330–1336. [PMC free article: PMC2560634] [PubMed: 11143193]

- 89.

- Flavin MP, et al. Stages of development and injury patterns in the early years: a population-based analysis. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:187. [PMC free article: PMC1569842] [PubMed: 16848890]

- 90.

- Towner E, et al. Accidental falls: fatalities and injuries: an examination of the data sources and review of the literature on preventive strategies. London: Department of Trade and Industry; 1999.

- 91.

- Berger SE, Theuring C, Adolph KE. How and when infants learn to climb stairs. Infant Behavior and Development. 2007;30:36–49. [PubMed: 17292778]

- 92.

- Matheny AP. Accidental injuries. In: Routh D, et al., editors. Handbook of pediatric psychology. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1988.

- 93.

- Needleman RD. Growth and development. In: Behrman RE, et al., editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 17th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2003. pp. 23–66.

- 94.

- Ozanne-Smith J, et al. Community based injury prevention evaluation report: Shire of Bulla Safe Living Program. Canberra: Monash University Accident Research Centre; 1994. (Report No. 6)

- 95.

- Schelp L, Ekman R, Fahl I. School accidents during a three school-year period in a Swedish municipality. Public Health. 1991;105:113–120. [PubMed: 2068234]

- 96.

- Bangdiwala SI, Anzola-Perez E. The incidence of injuries in young people: log-linear multivariable models for risk factors in a collaborative study in Brazil, Chile, Cuba and Venezuela. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1990;19:125–132. [PubMed: 2351507]

- 97.

- Hijar-Medina MC, et al. Factores de riesgo de accidentes en el hogar en niños. Estudio de casos y controles. [The risk factors for home accidents in children. A case-control study]. Boletín Médico del Hospital Infantil de México. 1993;50:463–474. [PubMed: 8363745]

- 98.

- Mohan D. Childhood injuries in India: extent of the problem and strategies for control. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 1986;53:607–615. [PubMed: 3817981]

- 99.

- Yagmur Y, et al. Falls from flat-roofed houses: a surgical experience of 1643 patients. Injury. 2004;35:425–428. [PubMed: 15037379]

- 100.

- Krug EG, Sharma GK, Lozano R. The global burden of injuries. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:523–526. [PMC free article: PMC1446200] [PubMed: 10754963]

- 101.

- Rivara FP, et al. Population-based study of fall injuries in children and adolescents resulting in hospitalization or death. Pediatrics. 1993;92:61–63. [PubMed: 8516086]

- 102.

- Roudsari BS, Shadman M, Ghodsi M. Childhood trauma fatality and resource allocation in injury control programs in a developing country. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:117. [PMC free article: PMC1471786] [PubMed: 16670023]

- 103.

- Iltus S. Parental ideologies in the home safety management of one to four year old children. New York, NY: Graduate School and University Center of the City University of New York; 1994.

- 104.

- Wazana A. Are there injury-prone children? A critical review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;42:602–610. [PubMed: 9288422]

- 105.

- Morrongiello BA, Dawber T. Mothers’ responses to sons and daughters engaging in injury-risk behaviors on a playground: implications for sex differences in injury rates. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2000;76:89–103. [PubMed: 10788304]

- 106.

- Reading R, et al. Accidents to preschool children: comparing family and neighbourhood risk factors. Social Science and Medicine. 1999;48:321–330. [PubMed: 10077280]

- 107.

- Engstrom K, Diderichsen F, Laflamme L. Socioeconomic differences in injury risks in childhood and adolescence: a nation-wide study of intentional and unintentional injuries in Sweden. Injury Prevention. 2002;8:137–142. [PMC free article: PMC1730860] [PubMed: 12120833]

- 108.

- Faelker T, Pickett W, Brison RJ. Socioeconomic differences in childhood injury: a population based epidemiologic study in Ontario, Canada. Injury Prevention. 2000;6:203–208. [PMC free article: PMC1730634] [PubMed: 11003186]

- 109.

- Pensola TH, Valkonen T. Mortality differences by parental social class from childhood to adulthood. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2000;54:525–529. [PMC free article: PMC1731712] [PubMed: 10846195]

- 110.

- Thanh NX, et al. Does the “Injury poverty trap” exist? A longitudinal study from Bavi, Vietnam. Health Policy. 2006;78:249–257. [PubMed: 16290127]

- 111.