Abstract

Free full text

Essential Genes Are More Evolutionarily Conserved Than Are Nonessential Genes in Bacteria

Abstract

The “knockout-rate” prediction holds that essential genes should be more evolutionarily conserved than are nonessential genes. This is because negative (purifying) selection acting on essential genes is expected to be more stringent than that for nonessential genes, which are more functionally dispensable and/or redundant. However, a recent survey of evolutionary distances between Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Caenorhabditis elegans proteins did not reveal any difference between the rates of evolution for essential and nonessential genes. An analysis of mouse and rat orthologous genes also found that essential and nonessential genes evolved at similar rates when genes thought to evolve under directional selection were excluded from the analysis. In the present study, we combine genomic sequence data with experimental knockout data to compare the rates of evolution and the levels of selection for essential versus nonessential bacterial genes. In contrast to the results obtained for eukaryotic genes, essential bacterial genes appear to be more conserved than are nonessential genes over both relatively short (microevolutionary) and longer (macroevolutionary) time scales.

Rates of evolution vary tremendously among protein-coding genes. Molecular evolutionary studies have revealed an ~1000-fold range of nonsynonymous substitution rates (Li and Graur 1991). The strength of negative (purifying) selection is thought to be the most important factor in determining the rate of evolution for the protein-coding regions of a gene (Kimura 1983; Ohta 1992; Li 1997). Consistent with this idea, Alan Wilson and colleagues (1997) proposed that essential genes should evolve more slowly than nonessential genes. This is the so-called “knockout-rate” prediction (Hurst and Smith 1999). “Essential” and “nonessential” are classic molecular genetic designations that relate to the functional significance of a gene with respect to its effect on organismic fitness. A gene is considered to be essential if a knock-out results in (conditional) lethality or infertility. On the other hand, nonessential genes are those for which knock-outs yield viable and fertile individuals. It was reasoned that purifying selection should be more intense for essential genes because they are, by definition, less functionally dispensable and/or redundant than are nonessential genes. Given the role of purifying selection in determining evolutionary rates, the greater levels of purifying selection on essential genes should be manifest as a lower rate of evolution relative to that of nonessential genes.

To systematically evaluate the relationship between the fitness effects of genes and their rates of evolution, a combination of a substantial amount of experimental knock-out data and sequence data from numerous genes is required. Only recently has enough data accumulated to allow for tests of the straightforward and seemingly intuitive knock-out rate prediction. However, examinations of sequence data with respect to this prediction have yielded equivocal results. For example, a survey of substitution rates for mouse and rat orthologous genes appeared to indicate a slower rate of evolution for essential genes. But when genes thought to evolve under directional selection were excluded from the analysis, essential and nonessential genes were found to evolve at similar rates (Hurst and Smith 1999). A more recent analysis of the evolutionary distances between Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Caenorhabditis elegans proteins did indicate that the fitness effect of a protein influences its rate of evolution (Hirsh and Fraser 2001). Nevertheless, this study (Hirsh and Fraser 2001) was also unable to reveal any difference between the rates of evolution for essential and nonessential genes.

The results from both of these studies were taken to indicate that the fitness differences between essential and nonessential genes do not influence evolutionary rates to the extent that was expected. However, the studies relied on the analyses of relatively few genes (n =

= 175 and n

175 and n =

= 287, respectively) and comparisons between species that diverged at least tens of millions of years ago. It might be the case that these results reflect a lack of power and sensitivity of the approaches that were used. The recent availability of complete genome sequences from different strains of the same bacterial species provides an opportunity to address the issue with an unprecedented level of resolution. In the present study, to test the knockout-rate prediction, the relationship between the fitness class of genes (essential versus nonessential) and their rate of evolution was assessed for three bacterial species: Escherichia coli, Helicobacter pylori, and Neisseria meningitidis, for each of which at lease two complete genome sequences are available.

287, respectively) and comparisons between species that diverged at least tens of millions of years ago. It might be the case that these results reflect a lack of power and sensitivity of the approaches that were used. The recent availability of complete genome sequences from different strains of the same bacterial species provides an opportunity to address the issue with an unprecedented level of resolution. In the present study, to test the knockout-rate prediction, the relationship between the fitness class of genes (essential versus nonessential) and their rate of evolution was assessed for three bacterial species: Escherichia coli, Helicobacter pylori, and Neisseria meningitidis, for each of which at lease two complete genome sequences are available.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The Profiling of the E. coli Genome (PEC) database (http://www.shigen.nig.ac.jp/ecoli/pec/) was used to characterize E. coli genes as essential, nonessential, or undetermined. E. coli genes in this database are characterized as essential or nonessential based largely on experimental (null mutations) evidence. In addition to the use of experimental evidence, a much smaller number of genes were designated as essential or nonessential based simply on their known function (see Methods). For example, the genes for ribosomal proteins were assumed to be essential, whereas genes involved in flagellation, motility, and chemotaxis were classified as nonessential. Comparisons between essential and nonessential E. coli genes were performed using all of the data available from the PEC database and with a reduced data set that contained only essential and nonessential genes for which experimental evidence existed. Sets of orthologous protein sequences and the corresponding nucleotide sequences shared by the two completely sequenced E. coli strains were identified and aligned, and nucleotide sequence alignments were used to calculate the synonymous (Ks) and nonsynonymous (Ka) substitution rates (see Methods). Values of Ks and Ka were compared for E. coli genes designated as either essential or nonessential. Analysis of these genes showed that the average Ks and Ka were significantly lower for essential genes than for nonessential genes (Table (Table1).1). This is the case for both the entire data set and the reduced set containing only experimentally characterized genes (Table (Table1).1). The reduction in Ka for essential genes indicates a reduction in the intraspecific rate of essential protein evolution, and the reduction in Ks is consistent with the positive correlation between Ks and Ka (Table (Table1).1). Such a correlation between Ks and Ka values has also been observed for several other species (Wolfe and Sharp 1993; Ohta and Ina 1995; Makalowski and Boguski 1998). This correlation could reflect a mechanistic bias in mutation or indicate that synonymous sites are also subject to some degree of selection (or both). However, the significantly lower value of Ka/Ks for essential genes (Table (Table1)1) indicates that the difference between the rates of evolution for the two gene classes is more pronounced for Ka than for Ks and is consistent with more stringent negative selection against amino acid replacements acting on essential genes. The undetermined genes, which were not included in either the essential or the nonessential class, had somewhat greater average Ka and Ka/Ks values than those of the nonessential genes (Table (Table1).1).

Table 1

The Rates of Synonymous (Ka) and Nonsynonymous (Ks) Nucleotide Substitutions for Essential Versus Nonessential Bacterial Genes

Genes

| Ks (±se)a | Ka (±se)b | rc | Ka/Ks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli—alld | 26.99 × × 10−3 10−3 | 1.11 × × 10−3 10−3 | 0.35 | 4.50 × × 10−2 10−2 |

Essential (n = 205) Essential (n = 205) | (±2.1 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.1 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.7 × × 10−2) 10−2) | |

Nonessential (n = 1794) Nonessential (n = 1794) | 51.0 × × 10−3 10−3 | 3.60 × × 10−3 10−3 | 0.44 | 8.40 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±1.0 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.2 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.2 × × 10−2) 10−2) | ||

Undetermined (n = 1107) Undetermined (n = 1107) | 48.6 × × 10−3 10−3 | 5.00 × × 10−3 10−3 | 0.47 | 11.67 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±1.3 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.3 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.5 × × 10−2) 10−2) | ||

Significance of the differencef Significance of the differencef | P = 0 | P = 5.6 × × 10−16 10−16 | na | P = 6.4 × × 10−6 10−6 |

| E. coli—experimentale | 35.33 × × 10−3 10−3 | 1.36 × × 10−3 10−3 | 0.33 | 4.73 × × 10−6 10−6 |

Essential (n = 150) Essential (n = 150) | (±2.5 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.2 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.7 × × 10−2) 10−2) | |

Nonessential (n = 1736) Nonessential (n = 1736) | 51.29 × × 10−3 10−3 | 3.60 × × 10−3 10−3 | 0.44 | 8.27 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±1.0 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.2 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.4 × × 10−2) 10−2) | ||

Significance of the differencef Significance of the differencef | P = 1.2 × × 10−7 10−7 | P = 1.2 × × 10−8 10−8 | na | P = 5.6 × × 10−4 10−4 |

| Helicobacter pylori | 111.33 × × 10−3 10−3 | 12.89 × × 10−3 10−3 | 0.43 | 11.32 × × 10−2 10−2 |

Essential (n = 98) Essential (n = 98) | (±4.1 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±1.1 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.9 × × 10−2) 10−2) | |

Nonessential (n = 130) Nonessential (n = 130) | 135.24 × × 10−3 10−3 | 21.64 × × 10−3 10−3 | 0.30 | 16.14 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±3.1 × × 10−2) 10−2) | (±1.4 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.8 × × 10−2) 10−2) | ||

Significance of the differencef Significance of the differencef | P = 3.5 × × 10−6 10−6 | P = 6.1 × × 10−7 10−7 | na | P = 6.1 × × 10−4 10−4 |

| Neisseria meningitidis | 65.37 × × 10−3 10−3 | 4.76 × × 10−3 10−3 | 0.68 | 7.32 × × 10−2 10−2 |

Essential (n = 98) Essential (n = 98) | (±6.9 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.7 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±1.0 × × 10−2) 10−2) | |

Nonessentials (n = 130) Nonessentials (n = 130) | 91.56 × × 10−3 10−3 | 9.60 × × 10−3 10−3 | 0.49 | 17.65 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±5.9 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.9 × × 10−3 10−3 | (±1.9 × × 10−2) 10−2) | ||

Significance of the differencef Significance of the differencef | P = 1.6 × × 10−4 10−4 | P = 1.0 × × 10−7 10−7 | na | P = 4.2 × × 10−5 10−5 |

It is a formal possibility that a relatively few genes with extreme values contributed disproportionately to the average Ka, Ks, and Ka/Ks and were thus largely responsible for the difference between these average values for essential and nonessential E. coli genes. The fact that we observed the significant difference between the essential and nonessential genes after the nonexperimentally assigned genes for ribosomal proteins were removed from the essential set (Table (Table1)1) argues against this possibility. Indeed, although the ribosomal protein genes are highly conserved and had substantially lower average values of Ka, Ks, and Ka/Ks than those for the rest of the essential genes (data not shown), these genes alone clearly did not account for the difference between the essential and nonessential set.

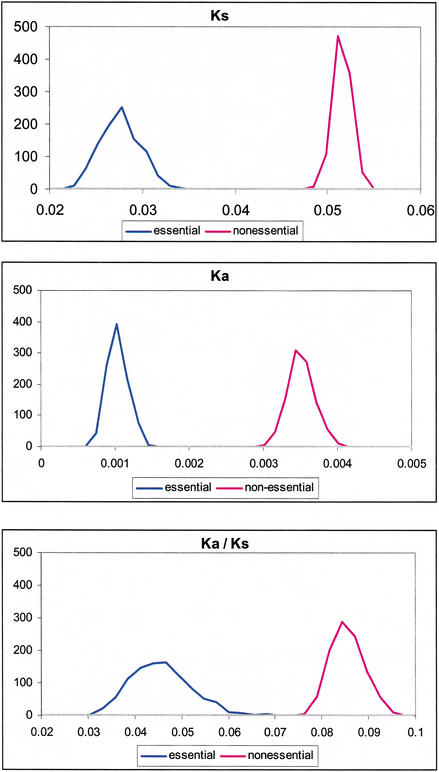

To further assess the effect of potential biases in the essential gene set on the observed differences in evolutionary rates, the values of Ka, Ks, and Ka/Ks for essential and nonessential E. coli genes were reanalyzed with a bootstrap test (Methods). The frequency distributions of bootstrapped average Ka, Ks, and Ka/Ks show clear distinctions between essential and nonessential genes (Fig. (Fig.1).1). In addition, for each bootstrap replicate, the average values of essential and nonessential genes were calculated, and the significance of the difference between the essential and nonessential average values was assessed. For Ka and Ks each, all 1000 replicates differed at the P <

< 0.01 level; for Ka/Ks, 968 replicates differed at the P

0.01 level; for Ka/Ks, 968 replicates differed at the P <

< 0.01 level. Thus, the results of the bootstrap analysis reject the possibility that the average values of Ka, Ks, and Ka/Ks for essential and/or nonessential genes are greatly influenced by a few genes with extreme values.

0.01 level. Thus, the results of the bootstrap analysis reject the possibility that the average values of Ka, Ks, and Ka/Ks for essential and/or nonessential genes are greatly influenced by a few genes with extreme values.

Bootstrap test of the average rates of synonymous (Ks), nonsynonymoys (Ka), and Ka/Ks for essential and nonessential Escherichia coli genes. Frequency distributions for the average values of Ka, Ks, and Ka/Ks for 1000 bootstrap replicates are shown.

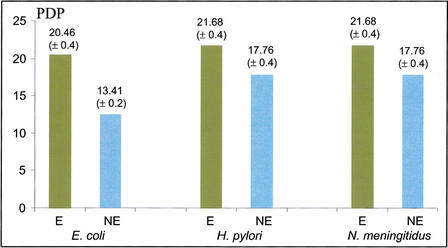

Evolutionary conservation over longer time scales was measured by calculating the phyletic distribution parameter of essential versus nonessential E. coli genes. This parameter indicates the extent to which orthologs of a gene are distributed among the 26 taxonomic groups in the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs) database (see Methods). Orthologs of essential E. coli genes are more broadly distributed (P <

< 10−10, Mann-Whitney U test) among bacterial and archaeal species than are orthologs of nonessential E. coli genes (Fig. (Fig.2).2).

10−10, Mann-Whitney U test) among bacterial and archaeal species than are orthologs of nonessential E. coli genes (Fig. (Fig.2).2).

Average phyletic distribution parameter values for essential (E) and nonessential (NE) genes in the three bacterial species surveyed. Average values (±SE) are shown above the bars. For the definition of the phyletic distribution parameter (PDP), see Methods.

Orthologs of essential and nonessential genes from E. coli (all genes in each category, without removing nonexperimentally characterized genes) were identified in H. pylori and N. meningitidis (see Methods). The classification of these orthologs as essential or nonessential in E. coli was taken as an approximation of their classification in H. pylori and N. meningitidis, and the same evolutionary comparisons were performed on them. For both species, the rates of Ks and Ka for 98 predicted essential genes were significantly lower than the rates for 130 predicted nonessential genes (Table (Table1).1). The differences among Ks and Ka values between all three species surveyed merely reflect the fact that for each species, the time to common ancestry for the two sequenced genomes, in all likelihood, differs significantly. Also like in the case of E. coli, the average Ka/Ks values are lower for the predicted essential genes (Table (Table1).1). Orthologs of predicted essential genes in these species were also more broadly phyletically distributed (P =

= 1.6×10−9 Mann-Whitney U test) than are orthologs of predicted nonessential genes (Fig. (Fig.2).2). An additional aspect of these comparisons was that N. meningitidis and particularly H. pylori had significantly greater values of Ks, Ka, and Ka/Ks than those for E. coli, such that, for example, even essential genes of H. pylori appeared to evolve faster than nonessential genes of E. coli (Table (Table1).1). A detailed examination of these differences is beyond the scope of the present work, but it seems interesting to speculate that they might reflect the parasitic lifestyle of N. meningitidis and H. pylori.

1.6×10−9 Mann-Whitney U test) than are orthologs of predicted nonessential genes (Fig. (Fig.2).2). An additional aspect of these comparisons was that N. meningitidis and particularly H. pylori had significantly greater values of Ks, Ka, and Ka/Ks than those for E. coli, such that, for example, even essential genes of H. pylori appeared to evolve faster than nonessential genes of E. coli (Table (Table1).1). A detailed examination of these differences is beyond the scope of the present work, but it seems interesting to speculate that they might reflect the parasitic lifestyle of N. meningitidis and H. pylori.

Finally, sets of interspecific (E. coli, H. pylori, and N. meningitidis) orthologous proteins were aligned, and the average pair-wise evolutionary distance for each set was calculated (see Methods). Essential proteins show a significantly lower (P =

= 6.3

6.3 ×

× 10−6 Mann-Whitney U test) average level of per site amino acid sequence variation (avgerage ± SE = 4.85 ± 0.25) among these three species than do nonessential genes (average

10−6 Mann-Whitney U test) average level of per site amino acid sequence variation (avgerage ± SE = 4.85 ± 0.25) among these three species than do nonessential genes (average ±SE

±SE =

= 6.83

6.83 ±

± 0.34).

0.34).

A previous comparison of the rates of evolution for essential versus nonessential genes in mammals initially revealed significantly lower rates of evolution for essential genes (Hurst and Smith 1999). However, when genes involved in the immune system, which are thought to evolve under diversifying (positive) selection, were removed from the analyzed data set, this difference disappeared. This result was attributed to substantial differences in the rates of evolution for different functional classes of genes. We sought to explore the potential contribution of this phenomenon to the observed difference between evolutionary rates of essential versus nonessential bacterial genes by breaking down the E. coli genes into four broad functional categories (see Methods): (1) information processing and storage, (2) cellular processes, (3) metabolism, and (4) poorly characterized. Not unexpectedly, comparison of the numbers of genes of each functional class that were designated as essential or nonessential revealed a nonrandom distribution (data not shown). For example, information storage and processing genes are vastly over-represented among essential genes, whereas there are far fewer poorly characterized genes than would be expected by chance in this same set. Notably, however, there were no significant differences in the evolutionary rates among information processing, cellular processes, and metabolic categories within the essential, nonessential, or undetermined sets; only the poorly characterized genes appeared to evolve significantly faster (Table (Table2).2). In three of the four functional classes, the essential genes had significantly lower values of Ka and tended to have significantly lower values of Ks and Ka/Ks than did the nonessential genes. In addition, in each of the classes, the undetermined genes were found to evolve even faster than nonessential ones, and this difference was significant on two occasions (Table (Table2).2). The only exception to this pattern was among the poorly characterized genes. Poorly characterized essential genes do have substantially lower rates of evolution than do nonessential genes, but the low number of these essential genes (n =

= 12) results in a statistical comparison that lacks power. Thus, the slower rate of evolution of essential genes compared with nonessential genes in bacteria appears to be a general phenomenon that is not limited to a particular functional category of genes.

12) results in a statistical comparison that lacks power. Thus, the slower rate of evolution of essential genes compared with nonessential genes in bacteria appears to be a general phenomenon that is not limited to a particular functional category of genes.

Table 2

The Rates of Synonymous (Ks) and Nonsynonymous (Ka) Nucleotide Substitutions among Different Functional Categories for Essential, Nonessential, and Undetermined Escherichia coli Genes

| Ks (±se)a | Ka (±se)b | Ka/Ks (±se) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information storage and processing | |||

Essential (n = 113) Essential (n = 113) | 19.42 × × 10−3 10−3 | 0.96 × × 10−3 10−3 | 3.89 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±2.3 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.2 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.8 × × 10−2) 10−2) | |

Nonessential (n = 222) Nonessential (n = 222) | 48.16 × × 10−3 10−3 | 3.50 × × 10−3 10−3 | 8.72 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±2.8 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.4 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±1.1 × × 10−2) 10−2) | |

Undetermined (n = 113) Undetermined (n = 113) | 52.31 × × 10−3 10−3 | 4.62 × × 10−3 10−3 | 11.69 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±4.4 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.6 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±1.8 × × 10−2) 10−2) | |

Significance of the differencec essential vs. nonessential Significance of the differencec essential vs. nonessential | P = 1.6 × × 10−15 10−15 | P = 1.6 × × 10−7 10−7 | P = 6.1 × × 10−3 10−3 |

Significance of the differencec essential vs. undetermined Significance of the differencec essential vs. undetermined | P = 3.2 × × 10−12 10−12 | P = 1.3 × × 10−10 10−10 | P = 1.3 × × 10−4 10−4 |

Significance of the differencec nonessential vs. undetermined Significance of the differencec nonessential vs. undetermined | NS | NS | NS |

| Cellular processes | |||

Essential (n = 46) Essential (n = 46) | 37.57 × × 10−3 10−3 | 1.32 × × 10−3 10−3 | 4.72 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±3.5 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.3 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±1.5 × × 10−2) 10−2) | |

Nonessential (n = 408) Nonessential (n = 408) | 47.17 × × 10−3 10−3 | 3.01 × × 10−3 10−3 | 7.86 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±1.9 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.3 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.7 × × 10−2) 10−2) | |

Undetermined (n = 154) Undetermined (n = 154) | 40.92 × × 10−3 10−3 | 4.10 × × 10−3 10−3 | 8.80 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±2.1 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.5 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.9 × × 10−2) 10−2) | |

Significance of the differencec essential vs. nonessential Significance of the differencec essential vs. nonessential | NS | P = 3.6 × × 10−2 10−2 | NS |

Significance of the differencec essential vs. undetermined Significance of the differencec essential vs. undetermined | NS | P = 2.0 × × 10−4 10−4 | P = 3.7 × × 10−4 10−4 |

Significance of the differencec nonessential vs. undetermined Significance of the differencec nonessential vs. undetermined | NS | P = 2.8 × × 10−3 10−3 | P = 3.2 × × 10−4 10−4 |

| Metabolism | |||

Essential (n = 34) Essential (n = 34) | 37.18 × × 10−3 10−3 | 1.09 × × 10−3 10−3 | 3.19 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±8.1 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.3 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±1.1 × × 10−2) 10−2) | |

Nonessential (n = 725) Nonessential (n = 725) | 54.76 × × 10−3 10−3 | 2.52 × × 10−3 10−3 | 5.92 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±1.5 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.1 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.4 × × 10−2) 10−2) | |

Undetermined (n = 241) Undetermined (n = 241) | 59.32 × × 10−3 10−3 | 4.50 × × 10−3 10−3 | 9.80 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±3.2 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.3 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.8 × × 10−2) 10−2) | |

Significance of the differencec essential vs. nonessential Significance of the differencec essential vs. nonessential | P = 1.2 × × 10−4 10−4 | P = 1.2 × × 10−3 10−3 | P = 2.7 × × 10−3 10−3 |

Significance of the differencec essential vs. undetermined Significance of the differencec essential vs. undetermined | P = 8.2 × × 10−5 10−5 | P = 4.9 × × 10−8 10−8 | P = 1.7 × × 10−6 10−6 |

Significance of the differencec nonessential vs. undetermined Significance of the differencec nonessential vs. undetermined | NS | P = 3.6 × × 10−13 10−13 | P = 8.2 × × 10−11 10−11 |

| Poorly Characterized | |||

Essential (n = 12) Essential (n = 12) | 28.75 × × 10−3 10−3 | 1.75 × × 10−3 10−3 | 11.20 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±6.0 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.3 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±4.2 × × 10−2) 10−2) | |

Nonessential (n = 439) Nonessential (n = 439) | 49.59 × × 10−3 10−3 | 5.93 × × 10−3 10−3 | 13.08 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±2.1 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.6 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.9 × × 10−2) 10−2) | |

Undetermined (n = 599) Undetermined (n = 599) | 45.51 × × 10−3 10−3 | 5.51 × × 10−3 10−3 | 12.60 × × 10−2 10−2 |

(±1.7 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.5 × × 10−3) 10−3) | (±0.8 × × 10−2) 10−2) | |

Significance of the differencec essential vs. nonessential Significance of the differencec essential vs. nonessential | NS | NS | NS |

Significance of the differencec essential vs. undetermined Significance of the differencec essential vs. undetermined | NS | NS | NS |

Significance of the differencec nonessential vs. undetermined Significance of the differencec nonessential vs. undetermined | NS | NS | NS |

Despite intense scrutiny of the factors that influence the rate of protein evolution, confirmation of the straightforward prediction that essential genes should be more evolutionarily conserved than are nonessential genes (Wilson et al. 1977) has proven elusive. A recent study of protein variation between S. cerevisiae and C. elegans did reveal a significant linear relationship between the protein's level of dispensability (fitness class as determined in S. cerevisiae) and their rate of evolution (Hirsh and Fraser 2001). This is consistent with the idea that the rate of the evolution of a gene depends on its contribution to the fitness of the organism. However, this same study did not find any difference between the rates of evolution of essential versus nonessential genes. This lack of difference was attributed to the fact that ablation of many of the nonessential genes may have enough of an effect on organismal fitness to render them evolutionarily equivalent to essential genes. However, in the present study, a dense sampling of orthologous genes, facilitated by the completion of multiple bacterial genome sequences, allowed us to show that essential genes in bacteria are more conserved than are nonessential genes. It is unclear whether the difference between the findings for eukaryotic and bacterial genes is merely an effect of the sampling or a reflection of a real distinction between the evolutionary modes of these two domains of life.

A similar survey of mouse and rat orthologous genes initially found a difference between the evolutionary rates of essential and nonessential genes, but when genes thought to evolve under directional selection were excluded from the analysis, this distinction disappeared (Hurst and Smith 1999). This raises the question of whether the differences between essential and nonessential genes reported here is because of positive selection being more prevalent in nonessential genes or to purifying selection being more stringent among essential genes. We did not find any evidence of positive selection (i.e., Ka/Ks >

> 1) in our comparisons. However, Ka/Ks

1) in our comparisons. However, Ka/Ks >

> 1 is an extremely conservative criterion, which will reveal only cases of strong positive selection acting on large portions of genes. Therefore, it remains a formal possibility that the differences described here could be owing in small part to differences between essential and nonessential genes in the frequency of positive selection. However, purifying selection is clearly the rule in protein evolution, as evidenced by the Ka/Ks values reported here and in numerous other studies. Thus, consistent with the knockout-rate prediction (Wilson et al. 1977), differences in levels of purifying selection have certainly had the decisive role in determining the different rates of evolution of essential and nonessential bacterial genes.

1 is an extremely conservative criterion, which will reveal only cases of strong positive selection acting on large portions of genes. Therefore, it remains a formal possibility that the differences described here could be owing in small part to differences between essential and nonessential genes in the frequency of positive selection. However, purifying selection is clearly the rule in protein evolution, as evidenced by the Ka/Ks values reported here and in numerous other studies. Thus, consistent with the knockout-rate prediction (Wilson et al. 1977), differences in levels of purifying selection have certainly had the decisive role in determining the different rates of evolution of essential and nonessential bacterial genes.

Until this time, attempts to verify the knockout-rate prediction by comparing the evolutionary rate of essential versus nonessential genes have yielded equivocal results. This has led to the speculation that the rate of evolution for a given gene is determined more by the proportion of amino acid residues in the encoded protein that are critical for maintaining function than by the magnitude of the selection coefficient against deleterious mutations in that gene (Brookfield 2000). However, these two factors, in reality, might not be independent. In light of the results reported here, it might be the case that at least for bacterial genes, the rate of protein evolution is determined by the proportion of sites in a protein that has a large selection coefficient against deleterious mutations.

METHODS

Classification of E. coli K12 genes as essential, nonessential, or undetermined was taken from the PEC database (http://www.shigen.nig.ac.jp/ecoli/pec/). The PEC database classifies genes as essential or nonessential on the basis of a combination of experimental evidence and general functional considerations. If a strain has a null mutation in a gene and is able to grow, the gene in question is considered to be nonessential. Genes for which conditional lethal mutants have been isolated (Chow and Berg 1988; Harris et al. 1992) are classified as essential. In addition to the experimentally characterized genes, a much smaller subset of E. coli K12 genes were classified as essential or nonessential based on their functional characteristics (in absence of the specific experimental data listed above). For example, ribosomal structural genes and genes encoding unique aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases are classified as essential. Conversely, genes involved in flagellation, chemotaxis, and mobility were classified as nonessential. Essential, nonessential, and undetermined genes were placed into four broad functional categories using the classification scheme used in the COGs database (Tatusov et al. 1997, 2000, 2001).

Proteobacterial species with more than one complete genome sequence available as of GenBank release 123.0 were analyzed here: E. coli K12 (Blattner et al. 1997), E. coli O157:H7 (Perna et al. 2001), H. pylori 26695 (Tomb et al. 1997), H. pylori J99 (Alm et al. 1999), N. meningitidis serogroup B strain MC58 (Tettelin et al. 2000), and N. meningitidis serogroup A strain Z2491 (Parkhill et al. 2000). Nucleotide sequences and protein sequences predicted from complete bacterial genomes were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) FTP server (ftp://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/genomes/bacteria).

Orthologous protein sequences encoded by complete intraspecific genomes were identified using an all-against-all BLAST (Altschul et al. 1990, 1997) procedure. The SEALS package (Walker and Koonin 1997) was used to implement multiple BLAST searches and to postprocess the results of these searches. For any two intraspecific genomes, two proteins were considered orthologs if they were symmetrical best hits in each reciprocal all-against-all BLAST search. BLAST searches were run with a bits-per-position cutoff of 0.7. Orthologous proteins were aligned using ClustalW (Thompson et al. 1994) with default options. Orthologous protein-encoding nucleotide sequences were obtained from the NCBI FTP server and aligned to correspond to the protein sequence alignments using SEALS. The number of synonymous nucleotide substitutions per synonymous site (Ks), and the number of nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions per nonsynonymous site (Ka) were estimated for the resulting orthologous nucleotide sequence alignments using the Pamilo-Bianchi-Li method (Li 1993; Pamilo and Bianchi 1993).

Orthologous protein sequences encoded by interspecific genomes (E. coli, H. pylori, and N. meningitidis) were identified using a similar all-against-all BLAST approach implemented with the SEALS package. Proteins that formed mutually consistent triangles of symmetrical best hits (Tatusov et al. 1997) were considered to be orthologs (hence an identical number of orthologs from each genome in this analysis). Orthologous protein sequences were aligned using ClustalW as described above, and the resulting sequence alignments were used to calculate evolutionary distances between orthologous proteins. Distances were calculated using the 3BRANCH program (Y.I. Wolf, unpubl.; available on request) that implements a distance correction for multiple hits based on the γ-distribution of site rate variation (Ota and Nei 1994; Grishin 1995) with an α-parameter of 1.0. Distances are expressed as the number of substitutions per position.

The phyletic distribution of orthologous proteins was determined using the COGs database (Tatusov et al. 1997, 2000, 2001). The COGs database at the time of this work included species that fell into 26 distinct taxonomic groups. For each orthologous protein, a phyletic distribution parameter, which is equal to the number of taxonomic groups represented in the corresponding COG, was calculated.

The bootstrap analysis was performed by resampling with replacement from the original sets of per gene values of Ka, Ks, and Ka/Ks for essential and nonessential genes (calculated as described above). For each of 1000 bootstrap replicates, a resampled set with the same number of values as the original set was constructed. The average values for these resampled sets were then calculated and the averages of the essential and nonessential sets were compared.

Levels of significance for the difference among average Ks, Ka, Ka/Ks, phyletic distribution parameter, and levels of protein sequence variation were determined using the Mann-Whitney U test.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

WEB SITE REFERNCES

ftp://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/genomes/bacteria; Bacterial genomes from the National Center for Biotechnology Information FTP server.

http://www.shigen.nig.ac.jp/ecoli/pec/; Profiling of the E. coli Genome database.

Footnotes

E-MAIL vog.hin.mln.ibcn@ninook; FAX (301) 435-7794.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.87702. Article published online before print in May 2002.

REFERENCES

- Alm RA, Ling LS, Moir DT, King BL, Brown ED, Doig PC, Smith DR, Noonan B, Guild BC, deJonge BL, et al. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1999;397:176–180. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Blattner FR, Plunkett G, III, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner JD, Rode CK, Mayhew GF, et al. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Brookfield JF. What determines the rate of sequence evolution? Curr Biol. 2000;10:R410–R411. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Chow WY, Berg DE. Tn5tac1, a derivative of transposon Tn5 that generates conditional mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:6468–6472. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Grishin NV. Estimation of the number of amino acid substitutions per site when the substitution rate varies among sites. J Mol Evol. 1995;41:675–679. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Harris SD, Cheng J, Pugh TA, Pringle JR. Molecular analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome, I: On the number of genes and the identification of essential genes using temperature-sensitive-lethal mutations. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:53–65. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh AE, Fraser HB. Protein dispensability and rate of evolution. Nature. 2001;411:1046–1049. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst LD, Smith NG. Do essential genes evolve slowly? Curr Biol. 1999;9:747–750. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. The neutral theory of molecular evolution. NewYork, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Li WH. Unbiased estimation of the rates of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution. J Mol Evol. 1993;36:96–99. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- ————— . Molecular evolution. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Li WH, Graur D. Fundamentals of molecular evolution. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Makalowski W, Boguski MS. Evolutionary parameters of the transcribed mammalian genome: An analysis of 2,820 orthologous rodent and human sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:9407–9412. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta T. The nearly neutral theory of molecular evolution. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1992;23:263–286. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta T, Ina Y. Variation in synonymous substitution rates among mammalian genes and the correlation between synonymous and nonsynonymous divergences. J Mol Evol. 1995;41:717–720. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ota T, Nei M. Estimation of the number of amino acid substitutions per site when the substitution rate varies among sites. J Mol Evol. 1994;38:642–643. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Pamilo P, Bianchi NO. Evolution of the Zfx and Zfy genes: Rates and interdependence between the genes. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10:271–281. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill J, Achtman M, James KD, Bentley SD, Churcher C, Klee SR, Morelli G, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, et al. Complete DNA sequence of a serogroup A strain of Neisseria meningitidis Z2491. Nature. 2000;404:502–506. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Perna NT, Plunkett G, III, Burland V, Mau B, Glasner JD, Rose DJ, Mayhew GF, Evans PS, Gregor J, Kirkpatrick HA, et al. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature. 2001;409:529–533. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science. 1997;278:631–637. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. The COG database: A tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:33–36. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov RL, Natale DA, Garkavtsev IV, Tatusova TA, Shankavaram UT, Rao BS, Kiryutin B, Galperin MY, Fedorova ND, Koonin EV. The COG database: New developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:22–28. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tettelin H, Saunders NJ, Heidelberg J, Jeffries AC, Nelson KE, Eisen JA, Ketchum KA, Hood DW, Peden JF, Dodson RJ, et al. Complete genome sequence of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B strain MC58. Science. 2000;287:1809–1815. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tomb JF, White O, Kerlavage AR, Clayton RA, Sutton GG, Fleischmann RD, Ketchum KA, Klenk HP, Gill S, Dougherty BA, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DR, Koonin EV. SEALS: A system for easy analysis of lots of sequences. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1997;5:333–339. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AC, Carlson SS, White TJ. Biochemical evolution. Annu Rev Biochem. 1977;46:573–639. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe KH, Sharp PM. Mammalian gene evolution: Nucleotide sequence divergence between mouse and rat. J Mol Evol. 1993;37:441–456. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Articles from Genome Research are provided here courtesy of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.87702

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

http://genome.cshlp.org/content/12/6/962.full.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

An open-access dashboard to interrogate the genetic diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates.

Sci Rep, 14(1):24792, 21 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39433543 | PMCID: PMC11494124

Are there conserved biosynthetic genes in lichens? Genome-wide assessment of terpene biosynthetic genes suggests ubiquitous distribution of the squalene synthase cluster.

BMC Genomics, 25(1):936, 07 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39375591 | PMCID: PMC11457338

GSearch: ultra-fast and scalable genome search by combining K-mer hashing with hierarchical navigable small world graphs.

Nucleic Acids Res, 52(16):e74, 01 Sep 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 39011878 | PMCID: PMC11381346

Differentially used codons among essential genes in bacteria identified by machine learning-based analysis.

Mol Genet Genomics, 299(1):72, 27 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39060647

Integrating bacterial molecular genetics with chemical biology for renewed antibacterial drug discovery.

Biochem J, 481(13):839-864, 01 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38958473 | PMCID: PMC11346456

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (351) article citations

Other citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Evolutionary conservation analysis between the essential and nonessential genes in bacterial genomes.

Sci Rep, 5:13210, 14 Aug 2015

Cited by: 44 articles | PMID: 26272053 | PMCID: PMC4536490

Microevolutionary genomics of bacteria.

Theor Popul Biol, 61(4):435-447, 01 Jun 2002

Cited by: 70 articles | PMID: 12167363

Review

How essential are nonessential genes?

Mol Biol Evol, 22(11):2147-2156, 13 Jul 2005

Cited by: 98 articles | PMID: 16014871

Origins and impact of constraints in evolution of gene families.

Genome Res, 16(12):1529-1536, 19 Oct 2006

Cited by: 37 articles | PMID: 17053091 | PMCID: PMC1665636