Abstract

Free full text

SPECIFIC LONG-TERM MEMORY TRACES IN PRIMARY AUDITORY CORTEX

Abstract

Learning and memory involve the storage of specific sensory experiences. However, until recently the idea that the primary sensory cortices could store specific memory traces had received little attention. Converging evidence obtained using techniques from sensory physiology and the neurobiology of learning and memory supports the idea that the primary auditory cortex acquires and retains specific memory traces about the behavioural significance of selected sounds. The cholinergic system of the nucleus basalis, when properly engaged, is sufficient to induce both specific memory traces and specific behavioural memory. A contemporary view of the primary auditory cortex should incorporate its mnemonic and other cognitive functions.

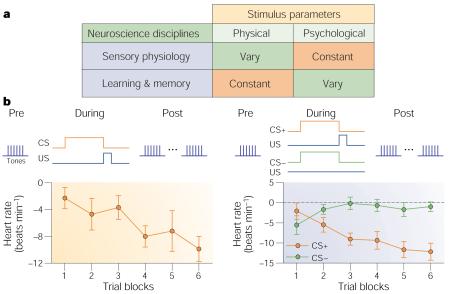

Identifying the neural substrates of learning and memory is a core problem in neuroscience. As memories involve the representation of past sensory events, they may be stored, in part, within sensory systems. Sensory systems have traditionally been viewed as ‘stimulus analysers’, with learning and memory assigned to ‘higher’ cortical regions. Nonetheless, neurophysiological studies have produced evidence for learning-induced plasticity in sensory cortices, and in particular the auditory cortex. Galambos and colleagues first implicated the primary auditory cortex (A1) in learning in 1956, observing that pairing an auditory conditioned stimulus (CS) with a weak shock (a mildly aversive unconditioned stimulus (US)) produced a significant increase in the amplitude of CS-elicited evoked field potentials in A1 of the cat1. Subsequently, these findings were extended to other tasks (such as discrimination), types of learning (including instrumental conditioning), motivations (for example, food) and types of recording (such as single and multiple unit discharges)2.

Although such results established associative plasticity in A1, neither they nor similar findings in other sensory cortices addressed the key issue of specificity of information storage. As memories have specific content, how could changes in the magnitude of sensory cortical responses adequately reflect the encoding of specific aspects of experiences? A solution was provided by the field of sensory neurophysiology, which focuses on stimulus specificity. Sensory physiology experiments use a wide range of stimulus values to determine how specific sensory stimuli are processed and coded. In fact, the basic paradigms of sensory physiology and learning are complementary (Box 1).

This article presents an overview of research that combines experimental designs from sensory physiology with those of learning and memory to search for specific memory traces in A1. A sign of a specific memory trace would be learning-induced physiological plasticity that has the key characteristics of behavioural memory and sufficient specificity to encode a canonical attribute of experience, such as a physical feature and its behavioural importance. Previous reviews have covered other aspects of learning-related plasticity in the auditory system3-8.

Learning-induced plasticity in A1

Converging evidence of highly specific learning-induced plasticity in A1 has been reported in studies of cortical metabolism, receptive field plasticity, tonotopic map plasticity and human imaging studies. We consider them in turn, with regard for important methodological criteria (Box 2).

Metabolic studies

In a seminal study, Gonzalez-Lima and Scheich9 exposed rats to frequency-modulated (FM) tone sweeps (4–5 kHz) paired with strong, aversive stimulation of the midbrain reticular formation. After first receiving the CS and US randomly, the animals were injected with 2-deoxy-2-fluoro-d-[14C](U)glucose (2-DG), and then received either training or a control treatment. Only the group in which the CS and US were paired developed behavioural conditioned bradycardia. Analysis of auto-radiographs indicated that the CS–US paired group exhibited the largest increase in 2-DG uptake and that it was confined to the locus of representation of the CS stimulus (4–5 kHz) in A1. No other group exhibited this pattern. So, the authors had discovered highly frequency-specific, associative plasticity in A1 of the rat; increased auditory cortical metabolic activity was found only in regions that encoded the frequency components of the conditioned stimulus.

Some evidence for specificity has also been reported in an appetitive task. Rats were trained in a maze to locate a 1-kHz tone from one of four speakers in order to obtain a food reward. The trained group exhibited increased 2-DG uptake in layer IV of A1 compared with control groups10. The site of the effect seems to be consistent with a 1-kHz locus, but lack of independent verification of its place in the tonotopic map limits conclusions.

Receptive field plasticity: tuning shifts

A complementary line of inquiry combined protocols from auditory physiology with those of learning and memory. Frequency receptive fields (RFs) were measured before and after a standard learning task, and were compared to detect the effects of the intervening learning experience.

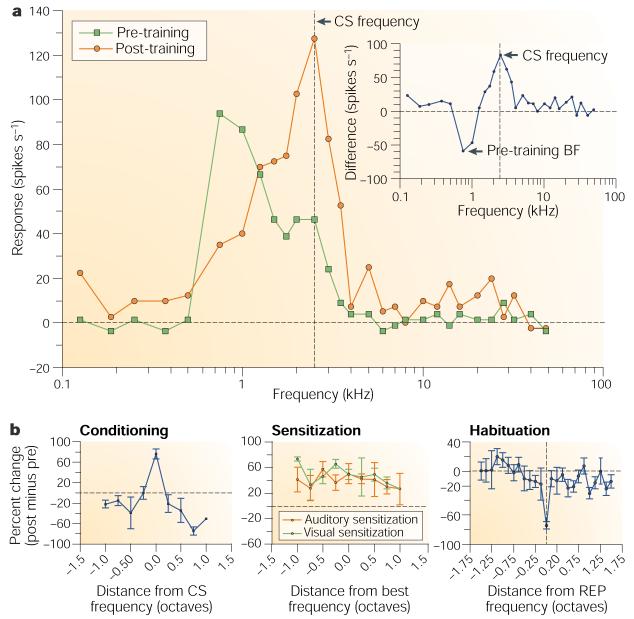

The first study of RF plasticity in A1 involved a single session of fear conditioning (tone–shock pairing) in the guinea pig11. (For earlier findings in non-primary auditory fields, see refs 12-14.) Subjects in the paired group (but not an unpaired sensitization control group) developed behavioural responses to the CS, such as freezing, that are consistent with fear conditioning. Importantly, the paired group alone developed CS-specific RF plasticity. Responses to the CS frequency increased, whereas responses to the pre-training best frequency (BF) of the neurons and to other frequencies decreased. These changes were sufficient to shift tuning towards or to the frequency of the conditioned stimulus, so that it became the new BF of the neurons (Fig. 1a). Tuning shifts were always towards the CS frequency, not away from it. The lack of tuning shifts in sensitization controls in this and a subsequent study15 shows that CS-specific RF plasticity is associative (Fig. 1b).

a | Receptive field plasticity of a single cell in auditory cortex, showing frequency tuning functions (70 dB) before and after tone-shock conditioning, and the resultant shift in tuning to the frequency of the conditioned stimulus (CS). The inset shows the difference in tuning (post minus pre), with the maximum increase in response at the frequency of the CS. Modified, with permission, from ref. 134 © (1997) Academic Press. b | Normalized group pre-post difference functions, showing change in response as a function of octave distance from the CS frequency. Conditioning (left) produces a specific increase in A1 response to the CS frequency with reduced responses at most frequency distances. Sensitization training produces a non-specific increase in response across all frequencies, both for auditory sensitization (tone-shock unpaired) and visual sensitization (light-shock unpaired), showing that this non-associative effect is transmodal. Repeated presentation of the same tone alone (habituation) produces a specific decreased response at that frequency. Reproduced, with permission, from ref. 135 © (1995) MIT Press. REP, repeated frequency.

Both behavioural learning and RF plasticity show discrimination between tones. Guinea pigs trained for only 30 trials with two randomly presented, differentially reinforced tones (CS+, tone was followed by shock; CS−, tone was followed by nothing) developed conditioned bradycardia to the CS+ only. RF analyses revealed that responses to the CS+ frequency increased whereas those to the CS− and to the pre-training BF decreased, again shifting tuning towards or to the CS frequency16. Similar findings were obtained in instrumental conditioning, in which guinea pigs rotated a wheel in response to a tone to avoid shock, for both single tone and two-tone discrimination17.

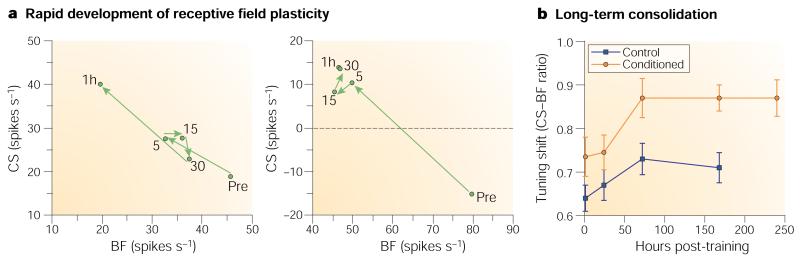

Associative learning can develop rapidly, particularly in the context of fear conditioning. During a single 30-trial training session, RFs were obtained after five, fifteen and thirty trials and after a one-hour retention period. Both the behavioural CR (bradycardia) and RF plasticity developed within five trials. RF plasticity was still present after one hour. The opposite changes in response to the CS frequency and the pre-training BF could be very large and even produce a reversal of response sign, that is, a CS frequency that was originally inhibitory became excitatory and vice versa for the pre-training BF18 (Fig. 2a).

a | Rapid induction (five trials) of RF plasticity, shown as vector diagrams of changes in response to the pre-training best frequency (BF) and the conditioned stimulus (CS) frequency, from suprathreshold (75 dB) responses for individual subjects. Left: after five trials, responses to the BF had decreased while those to the CS increased. Changes were maintained after 15 and 30 trials, but further change developed after one hour (consolidation), at which time the CS frequency became the new BF. Right: sign change in which the CS frequency was inhibitory before training but became excitatory after only five trials; the initial response to the CS was too weak for it to become the new BF or to exhibit consolidation in one hour. Reproduced, with permission, from ref. 18 © (1993) American Psychological Association. b | Long-term consolidation (group RF data) in which responses to the CS frequency increased relative to the pre-training BF over three days (72 hours) and then stabilized over ten days. The effects were significantly different from those for an unpaired group that was studied to seven days post-training22.

Long-term retention has been studied in guinea pigs that received a single session of tone–shock pairing while post-training RFs were obtained at various times up to eight weeks later. To investigate the physiological states under which RF plasticity can be expressed, animals were trained while awake but RFs were obtained while they were anaesthetized (sodium pentobarbital or ketamine). RF plasticity was retained for up to eight weeks19. The expression of plasticity under general anaesthesia ruled out possible arousal effects and showed that CS-specific RF plasticity can transfer across physiological states.

Memories are not fixed at the time of learning — rather, their strength increases as they become consolidated20. Neural consolidation of RF plasticity had been observed over one hour19. A more complete time course of neural consolidation was studied by training guinea pigs in a single, 30-trial session of tone–shock pairing and obtaining the RFs of local field potentials one hour and one, three, seven and ten days later. Pre-training tuning was stable, showing no drift over 14 days21. For the study of consolidation, both paired and unpaired groups were used. CS-specific RF plasticity developed only in the paired group and was retained for ten days, as expected19. More importantly, the plasticity that was evident one hour after training continued to grow in CS-specificity and magnitude for three days, at which time it reached asymptote22 (Fig. 2b). The rate of consolidation was directly related to the pre-training frequency distance (the magnitude of difference between the CS and best frequencies) and to the strength of response to the CS; cells that were tuned closer to the CS, and therefore were more responsive to it, completed their tuning changes within one hour, whereas cells that were tuned to more distant frequencies, and so were less responsive to the CS, required three days to complete their tuning shifts. These findings seem to be the first direct observation of long-term neural consolidation in memory.

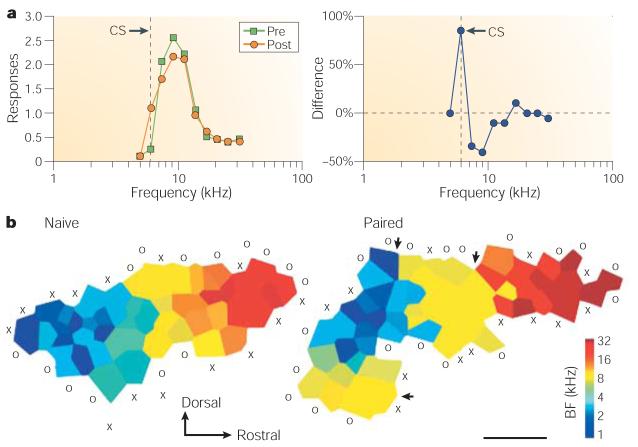

Specific memory traces in A1 have also been found in an appetitive situation in which brain stimulation serves as a proxy for normal reward. Kisley and Gerstein23 used stimulation of the medial forebrain bundle (MFB) in the lateral hypothalamus as positive reinforcement24. The stimulation was paired with a tone in a single session of 30 trials. Unit recordings from A1 revealed a shift of RF tuning towards or to the frequency of the CS that was maintained for the three-day period of the study. Tuning shifts developed only after the tone was paired with MFB stimulation, showing that the effects were due to association and were highly specific (Fig. 3a). Recordings of local field potentials instead of unit discharges produced the same findings.

a | Rats received a tone paired with electrical stimulation of positive reinforcement neurons in the medial forebrain bundle. After a single session (30 trials), single neurons in A1 exhibited CS-specific suprathreshold RF plasticity23. The graphs show an example of single unit RFs (left) and RF difference (post minus pre-training) (right) for a case in which tuning did not shift because the CS frequency initially elicited little excitation. However, conditioning produced an increased response only to the CS frequency. Left panel modified, with permission, from ref. 23 © (2001) Blackwell Publishing. b | Rats received a tone paired with electrical stimulation of ‘reward’ neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA). Shown are threshold maps of frequency representation for a naive and an experimental animal. Pairing produced a marked increase in the area of representation of the paired tone (yellow area). Modified, with permission, from ref. 38 © (2001) Macmillan Magazines Ltd.

Gao and Suga have reported CS-specific tuning shifts in the big brown bat25, although the experimental approach does not meet the criteria for associative learning. Bats received 60 trials of tone-shock pairing (one trial every 30 s); the unconditioned response to the shock was leg flexion and body movement. The authors reported that the CS tones elicited flexion and body movement during trials 40–60 in a paired group only. However, no behavioural data or learning functions were presented. In this study, tuning shifts towards or to the frequency of the CS persisted for around three hours.

Although the CS-specific cortical plasticity replicates previous findings from the guinea pig and rat, and extends them to the bat, it might not be due to associative conditioning. As no behavioural measurements were made, actual learning could not be established. Also, the body movements and limb flexion that were described as the conditioned response could result from non-associative factors such as restlessness26,27. In addition, the use of fixed, 30-s inter-trial intervals permits temporal conditioning, in which animals produce behavioural responses as a function of the time between trials, not to the presentation of the CS28 (Box 2).

Although RF studies have consistently reported specific increased responses to the CS frequency, Ohl and Scheich29,30 reported specific decreased responses at the CS frequency but specific increased responses at adjacent lower and higher frequencies. They concluded that learning about a specific frequency is encoded by enhancement of ‘spectral contrast’ sensitivity rather than by increased response and tuning shifts to the behaviourally important frequency. The disparity from other findings undoubtedly reflects their use of a different experimental design which, unfortunately, could yield no data to support the assumption of behavioural learning. In these studies, gerbils underwent fear conditioning training in which they received continual presentation of brief (250 ms) tone bursts of many (up to 30) semi-randomized frequencies at very short interstimulus (and inter-trial) intervals (250 ms to 3 s). The experiment was divided into three continuous phases: pre-training, training and post-training. During the training phase, one of the frequencies was paired with tail shock. The training phase therefore constituted a unique discrimination experiment in which one frequency was the CS+ and numerous other frequencies were CS− stimuli, all being presented at far shorter intertrial intervals than used in studies of conditioning31,32. However, there is no evidence that animals can learn such a complex discrimination. Although the authors recorded heart rate, the inter-trial intervals were too brief to yield changes in cardiac responses that could have validated conditioned discrimination between the CS+ and CS− frequencies16 (Box 2). So, although the effects were specific to the CS+ frequency, and therefore support the view that learning produces specific memory traces in A1, further understanding of the findings will have to await studies in which behavioural learning can be validated33.

Specific modification of tonotopic maps

Like the primary visual and somatosensory cortices, A1 has a systematic organization that reflects that of its sensory epithelium, the cochlea. As the best responses to various acoustic frequencies are systematically related to places within the cochlea, so too is there a ‘tonotopic map’ across the surface of A1. Such maps are obtained by determining the frequency to which cells are most sensitive. Tonotopic maps represent the distribution of the frequency RFs at threshold of cells across the cortex. When specific tuning shifts were found in A1, it was predicted that the effects of learning would be seen as an increase in the area of representation of behaviourally important frequencies in tonotopic maps34. Owl monkeys that performed increasingly difficult discriminations in specific frequency bands over many months showed an increase in the area of representation for those frequency bands35. This was the first finding that learning specifically alters the tonotopic map and supports the view that behaviourally important sounds successfully ‘capture’ the tuning of neurons. However, this effect was produced using thousands of training trials over many months, whereas RF plasticity can be induced in a few minutes18. Although perceptual learning increases acuity on the trained dimension36, it is not likely that subjects encode and retain particular information about a specific frequency, leaving open the question of whether specific map expansion develops rapidly as in associative learning. In addition, perceptual frequency learning has been shown in the cat without an accompanying change in the tonotopic map of the cortex37. So, not all types of perceptual learning lead to tonotopic map reorganization.

Specific changes in cortical maps also have been found in an associative situation. Rats received a tone followed by electrical stimulation of the ventral tegmental area (VTA)38 — part of a reward system that involves the release of dopamine — for 40 hours over a 20-day period. No behavioural measures were obtained to show that the rats had formed an association between the tone and the reward. Mapping revealed a specific increased area of response to the tone (9 kHz); there was also increased selectivity (reduced response bandwidth) and increased response to the tone in an adjacent auditory field (Fig. 3b). These effects were blocked by systemic administration of dopamine D1- and D2-receptor antagonists, supporting the idea that the effects require the activation of dopamine receptors in unknown locations. Although the authors emphasize potential direct effects of dopamine on the auditory cortex, the effects could be secondary to blocking the rewarding effects of stimulation subcortically. When VTA stimulation was preceded by a 4-kHz tone and followed by a 9-kHz tone, the expansion was limited to the former, whereas the representation for the latter was decreased, indicating that the selective increase in area is controlled by the positive relation of a tone to subsequent VTA stimulation.

In a follow-up study, ‘backward conditioning’ was used, consisting of VTA stimulation followed by a tone of a given frequency39. This treatment produces ‘inhibitory’ conditioning40, in which the tone signals the absence of reward, but there was no behavioural verification of learning. The treatment produced a frequency-specific decrease in the area of representation.

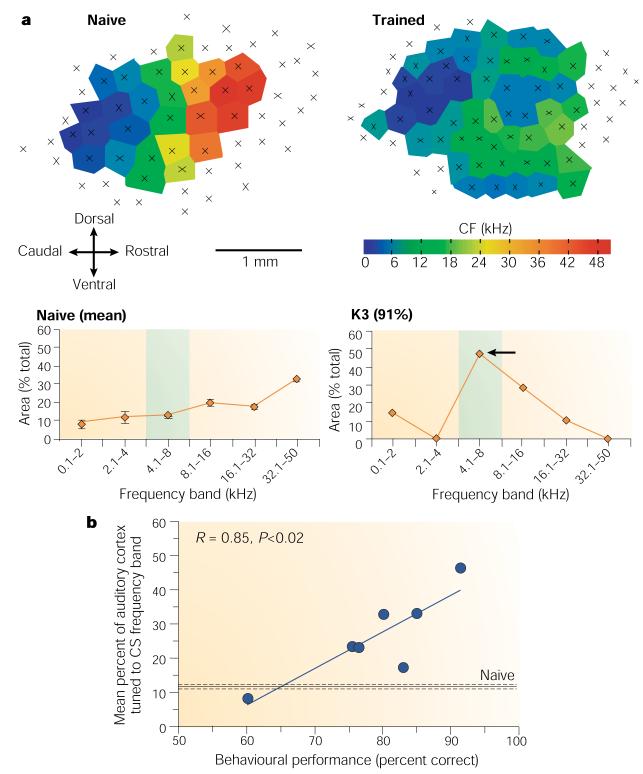

Normal reward, rather than brain stimulation, produces not only a specific expanded representation but one that reflects the magnitude of behavioural importance of the stimulus. Rutkowski et al. trained rats to associate a 6.0-kHz tone with the opportunity to press a bar and receive water41. The tone’s level of behavioural importance was controlled by the amount of supplemental water received in the home cages, so that asymptotic performance ranged across subjects from 60% to more than 90% correct. Controls received the same schedule of tone presentations but were rewarded only for responses in the presence of an illuminated lamp. Maps of A1 showed an expanded representation for the frequency band that was centred on 6.0 kHz (4–8-kHz band). Moreover, the percent of area tuned to the training frequency was significantly related to the level of behavioural importance, as indexed by the level of correct performance (rxy = 0.85) (Fig. 4). The control group showed no change in A1 organization.

a | Individual maps of naive (left) and trained subjects (right) and their respective area quantifications (below each); the naive function is the mean of five rats. The trained rat achieved a high level of 91% correct and an expansion of the octave centred on the 6-kHz signal tone from an average naive value of ~12% to ~45%. Shading denotes the CS frequency band. b | Across subjects, the higher the level of performance, the greater the area representing the training frequency. Modified, with permission, from ref. 42 © (2003) Academic Press. CF, characteristic (threshold) frequency.

The findings extend the specificity of learning-induced plasticity to appetitive instrumental learning and also indicate that the amount of representational area might be a ‘memory code’ for the level of behavioural significance of sound: the greater the importance, the larger the area tuned to that sound41-43. As the threshold area of representation increases at the expense of other frequencies, the latter probably suffer a decrease in sensitivity (higher thresholds) rather than elimination from processing. So, the memory code would allow a specific increase in the sensitivity of A1 to the most behaviourally important frequencies.

Imaging of human auditory cortex

The human auditory cortex also develops associative plasticity during aversive conditioning. Molchan et al. used positron emission tomography (PET) to assess regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) during eyeblink conditioning, in which a tone was paired with a corneal air puff to the right eye44. All subjects developed eyeblink conditioned responses. The rCBF in A1 increased significantly during the training period compared with the pre-training period, during which the tone was presented alone. In a follow-up study, more suitable control periods were used (tone and air puff unpaired) and CS-specific plasticity also developed in paired subjects only45. These studies implicated human A1 in associative learning but could not provide information on the degree of specificity of the plasticity.

Morris et al. determined the loci of plasticity within A1 using a two-tone discrimination design46. High (8-kHz) and low (0.4-kHz) tones constituted the CS+ and CS−, counterbalanced across subjects. The US was a noxious 100-dB burst of white noise. The authors measured the skin conductance response (SCR), which is a sensitive, rapidly developing conditioned response27. They used PET scanning and analysed more areas than in previous studies (see below). All subjects developed SCR discriminative responses, that is, CRs to the CS+ as compared with the CS−. Most importantly, cortical plasticity was specific to the locus of representation of the conditioned stimulus.

Summary of associative specificity

Metabolic, RF, cortical mapping and human imaging studies provide convergent evidence that A1 develops highly specific, associative plasticity during learning that has the characteristics of memory, including associativity, rapid development, consolidation and long-term retention. Furthermore, the plasticity has sufficient specificity to encode the acquired behavioural importance of a specific acoustic frequency, consistent with the view that A1 can develop and retain specific memory traces. The findings exhibit generality across tasks and types of learning, classes of motivation and reinforcement, and species.

Mechanisms and models

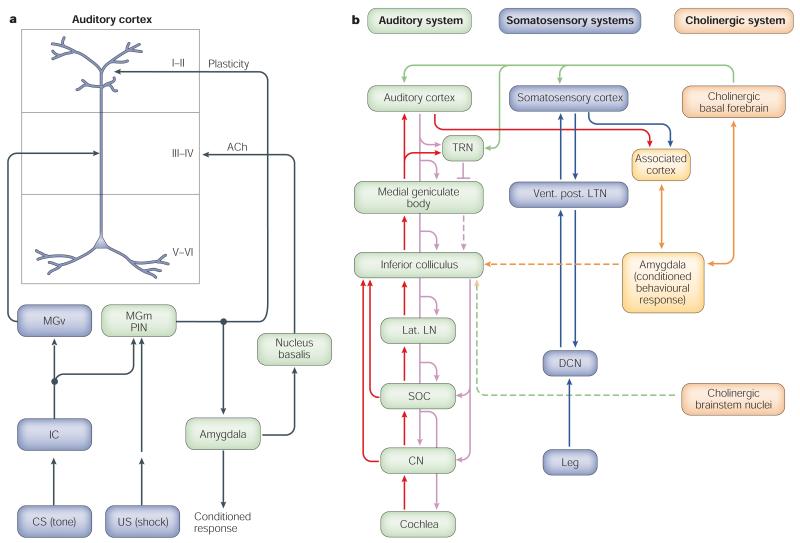

Investigation of mechanisms has focused on the loci of active plasticity and the role of neuromodulators, particularly acetylcholine (ACh). It will be helpful to start by considering the findings in the context of the models of Weinberger34,47 and Suga48, schematized in Fig. 5.

a | The model proposed by Weinberger et al.34,47. b | The model proposed by Suga and Ma48. ACh, acetylcholine; CS, conditioned stimulus; CN, cochlear nucleus; DCN, dorsal column nuclei; IC, inferior colliculus; MGm, medial geniculate body/posterior intralaminar complex; MGv, ventral medial geniculate body; lat. LN, lateral leminiscal nucleus; PIN, posterior intralaminar nucleus; SOC, superior olivary complex; TRN, thalamic reticular nucleus; US, unconditioned stimulus; vent. post. LTN, ventro-postero-lateral thalamic nucleus. See text for detailed discussion of the two models.

Loci of plasticity

In the Weinberger model (Fig. 5a), excitation caused by the tone and the direct or indirect effects of the shock converge at three loci. Tone information ascends the lemniscal auditory pathway from the cochlea through the ventral medial geniculate body (MGv) to reach A1. Tone information also reaches the non-lemniscal medial (magnocellular) division of the medial geniculate body/posterior intralaminar complex (MGm), where it converges with nociceptive information from the shock that ascends the spinothalamic pathway, facilitating the response of the MGm to the CS tone on subsequent trials. The MGm projects mainly to apical dendrites of pyramidal cells in layer I of A1, where its facilitated discharges converge with the excitatory effects of the immediately preceding tone on pyramidal cells. (It has recently been shown that transmission from MGm to A1 occurs through giant, rapidly conducting axons and therefore might increase pyramidal excitation before input from the MGv reaches A1 (ref. 49).) This convergence produces short-term RF plasticity that is sufficient for short-term memory but is too weak to induce enduring plasticity. However, the facilitated MGm response is also projected to the cholinergic nucleus basalis (NB), through the lateral and central nuclei of the amygdala, where it causes an increased release of ACh in the auditory cortex (and other areas). ACh, acting at muscarinic receptors in A1, converges with cortical excitation from the effects of the tone (through the direct MGv and indirect MGm paths), producing long-term plasticity. Responses to the CS tone are thereby strengthened, and increased responses to this frequency successfully compete with inputs from other frequencies, producing a shift in tuning (for further details, see refs 34,47,50).

This model was quickly shown to be wrong in its assumptions that transmission of CS information to the cortex involved no plasticity in the MGv. In fact, the MGv develops highly specific, but short-lasting, RF plasticity51. There has also been experimental support for the model. For example, in the human imaging study of Morris and colleagues46 summarized above, frequency-specific plasticity was found not only in A1 but also in the medialgeniculate nuclei (MGv and MGm could not be separated), amygdala, basal forebrain and orbitofrontal cortex. All of these loci of plasticity, except the orbitofrontal cortex, were predicted by the model. However, the purpose of this section is not to defend the model, which has been evaluated elsewhere50, but rather to use it as a point of departure in considering general findings and the recently formulated model of Suga and Ma.

Suga and colleagues have extended the domain of inquiry to the corticofugal system, specifically to the projections of the auditory cortex to the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus, and also to the somatosensory cortex, in the bat. Consequent to tone–shock pairing, they have reported CS-specific tuning shifts in both the auditory cortex and the inferior colliculus. Moreover, they report that collicular tuning shifts develop before auditory cortical shifts, although they disappear within about one hour whereas cortical shifts last at least 24 hours. Inactivation of the primary somatosensory cortex is reported to prevent cortical and collicular RF plasticity25,52. As reviewed above, the studies do not include validation of behavioural learning.

Suga’s model48 posits that first, the auditory and somatosensory cortices receive tone and shock (nociceptive) information, respectively. Then the CS and US information converge either in association cortex, which then projects to the amygdala, or in the amygdala itself, through separate relays in association cortex. The amygdala then effects the release of ACh into the cortex from the NB. Finally, the resultant auditory cortical plasticity produces tuning shifts in the colliculus and these enter into a positive feedback loop with A1 to strengthen what would otherwise be weak plasticity. (As noted above, the collicular shifts are reported to develop rapidly while the cortical shifts develop slowly25, which seems incompatible with the model’s principle that cortical plasticity induces collicular shifts.) Termination of the positive feedback loop, which ends the short-lived collicular plasticity, is hypothesized to be caused by inhibition from the thalamic reticular nucleus (TRS) (presumably at the level of the medial geniculate nucleus53,54), which receives cholinergic input from the NB (Fig. 5b). As the NB initiates and continues to promote plasticity in A1, it is not clear why its effect on the TRS should not simultaneously block ascending auditory input from the CS and break the positive feedback loop at the start of conditioning.

In considering active sites of plasticity, we begin with the auditory thalamus. As noted, the MGv does develop RF plasticity but it dissipates within an hour51, indicating that although the MGv could participate in the induction of cortical plasticity, it cannot be responsible for its consolidation or long-term retention. MGv plasticity is more consistent with Suga’s model of time-limited subcortical auditory plasticity. However, incompatible with the Suga view of slowly developing cortical plasticity is the fact that RF plasticity in A1 develops rapidly, within only five training trials18.

The MGm develops RF plasticity immediately after learning and for at least one hour (the longest period tested). However, it cannot simply project its plasticity to a ‘passive’ A1 because MGm RFs are much more complex, multipeaked and broadly tuned than those of auditory cortical cells55-57. Therefore, long-term, specific plasticity in A1 is not merely a reflection of plasticity in the subcortical auditory system but probably reflects processes in the cortex.

The Suga model ignores the MGm, its intrinsic associative plasticity and its influences on both A1 and the lateral amygdala (LA), but the following findings directly implicate the MGm: acoustic and nociceptive information converge directly in the MGm58,59; associative learning is accompanied by the development of plasticity in the MGm60-66, which is long-lasting63 and is evident as CS-specific RF plasticity after conditioning56,67; the MGm holds an associative memory trace after CS offset during conditioning68; analogues of learning show that stimulation of the MGm induces long-term potentiation in A1 (ref. 69) and tone paired with stimulation of the MGm induces heterosynaptic long-term potentiation in A1 (ref. 70) and behavioural conditioning71; lesions of the MGm interfere with auditory input to the amygdala during conditioning72-74; the MGm develops synaptic plasticity during conditioning and does so with a shorter latency than does the amygdala65; and fear conditioning produces increased presynaptic release of transmitter (glutamate) in MGm cells that project to the LA75. Selective lesions of the MGm should impair cortical RF plasticity, although this has not been tested.

The two models postulate very different roles for the amygdala. Suga’s model holds it to be either the first (and only) site of convergence of the CS and US, each relayed from separate association cortices, or the recipient of plasticity from one part of the association cortex that was the site of such convergence. The Weinberger model treats the amygdala as part of the associative machinery but not as the prime site of CS–US association. The evidence indicates that it would be premature to assign a primary function for learning to the amygdala76,77, particularly in light of the finding that destruction of the basolateral amygdala does not prevent fear conditioning77 but does impair unconditioned freezing, which is the behavioural assay on which the amygdala hypothesis is largely based78.

The relative roles of the MGm and the LA remain unresolved. For example, recent studies report that plasticity in the MGm is dependent on the amygdala, although there are no reciprocal geniculo-amygdala projections79,80. However, these studies inactivated the amygdala with muscimol, which has physiological effects for several millimetres around the injection site81. On the other hand, in an appetitive task, the MGm develops strong plasticity in waking and continues to express it during paradoxical sleep, whereas the basolateral amygdala (BLA) exhibits weaker plasticity and does not show plasticity during paradoxical sleep82. The authors conclude that the amygdala is more involved in strong emotional states, such as in aversive conditioning, whereas the MGm signals the importance of the CS for both aversive and appetitive conditioning. They also suggest that plasticity first develops in the MGm and then the results of this plasticity are sent to the lateral amygdala, which adds its own plasticity concerning the strength of motivation and/or the sign of emotion. This conception is compatible with the view that MGm plasticity affects A1 through its monosynaptic projections to the upper lamina. Given that RF and map plasticity develop in appetitive23,35,38 as well as aversive learning, the MGm might be more generally tied to cortical plasticity than is the amygdala.

The Suga model postulates that A1 is essential for fear conditioning because it provides auditory input to the amygdala. However, bilateral destruction of A1 does not impair fear conditioning to a tone83 and ablation of A1 does not prevent auditory stimuli from accessing the amygdala84. The Weinberger model hypothesizes that specific memory traces in A1 are not tied directly to immediate fear behaviours but serve a flexible function that can promote adaptive behaviour in unforeseen future situations.

The Suga model postulates that the somatosensory cortex is essential for the formation of both specific plasticity in A1 and behavioural fear conditioning, because it is claimed to provide nociceptive input to the amygdala, either directly or indirectly through association cortices (Fig. 5b). This conclusion is based on disruption of tone–shock tuning shifts following inactivation of the primary somatosensory cortex by muscimol. However, the adjacent A1 is well within the domain of diffusion of muscimol81. More importantly, complete decortication does not preclude tone-shock fear conditioning in the rat85, rabbit86 or cat87, or auditory–auditory associations in humans88. These findings also show that association cortices, which are hypothesized to be essential for fear conditioning as either direct or indirect conduits of tone and shock information to the amygdala, cannot fulfill that role.

Although the two models differ on a number of crucial points, the Suga model accepts the Weinberger model’s postulated role of the cholinergic NB, the system that we now address.

The NB cholinergic system

Several lines of research implicate ACh in learning-induced RF plasticity. However, other neuromodulators affect the function of A1. For example, noradrenaline alters tuning89,90, serotonin can regulate intensity-dependent response functions91 and its levels increase in A1 during initial stages of avoidance learning92, and dopamine is involved in the increased representation of a tone paired with stimulation of the VTA reward system38.

The NB is the main source of cortical ACh93,94 and there is extensive evidence for the importance of ACh and of the NB in particular in many aspects of learning (reviewed in ref. 33). Most relevant here, iontophoretic application of cholinergic agents to A1 acts through muscarinic receptors to produce long-lasting modification of frequency tuning 95,96; pairing a tone with ion-tophoretic application of muscarinic agonists induces pairing-specific, atropine-sensitive shifts of tuning97; and stimulation of the NB produces atropine-sensitive, persistent modification of evoked responses in A1 (refs 98,99) and facilitates the responses of A1 to tones100-102. Moreover, cells in the NB develop increased discharges to the CS+ during tone–shock conditioning before the development of neuronal plasticity in A1 (ref. 103). Stimulation of the NB or treatment with ACh promotes tone–shock pairing-induced tuning shifts in A1, whereas cholinergic antagonists or lesions of the NB have the opposite effect in animals104-106 and humans107. Finally, NB neurons that project to A1 selectively increase transcription of the gene for choline acetyltransferase, which synthesizes ACh, during tone–shock conditioning, indicating that acoustic learning engages specific cholinergic subcellular mechanisms108.

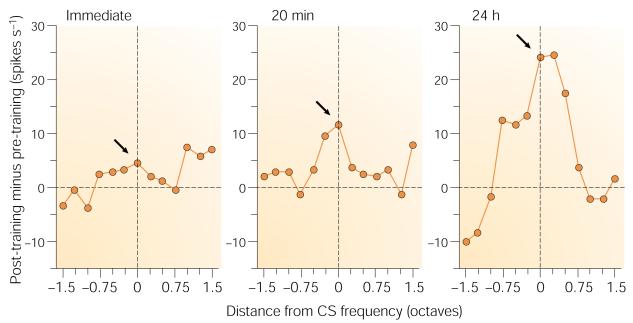

If learning-induced plasticity in A1 develops through engagement of the NB, then NB stimulation should be able to substitute for a standard reinforcer, such as food or shock, although no motivational reinforcement would be involved; NB stimulation itself is apparently not itself rewarding or punishing, as it is not part of any known motivational system109-111. It seems to act as an effective but neutral cortical activation mechanism112,113 that is ‘downstream’ of any motivational system. The NB cholinergic system can induce RF plasticity with the same characteristics as learning-induced RF plasticity. Pairing a tone with NB stimulation for only 30 trials induces CS-specific associative RF plasticity114, as does two-tone discrimination115, and this plasticity consolidates over 24 hours116 (Fig. 6). NB-induced RF plasticity depends on the engagement of muscarinic receptors in A1 (ref. 117). Also, the representation of a tone that is paired with NB stimulation is increased in the A1 threshold frequency map118,119.

Shown are group normalized difference tuning functions (post-training minus pre-training). Immediately after training, there was a small increase at the conditioned stimulus (CS) frequency (arrow) that became much larger and more specific 20 min later. Twenty-four hours later, this CS-specific effect had increased further116. So, properly timed activation of the NB is sufficient to induce associative, specific, long-lasting tuning plasticity that increases in strength in the absence of additional training (that is, develops consolidation). Modified, with permission, from ref. 116 © (1998) American Psychological Association.

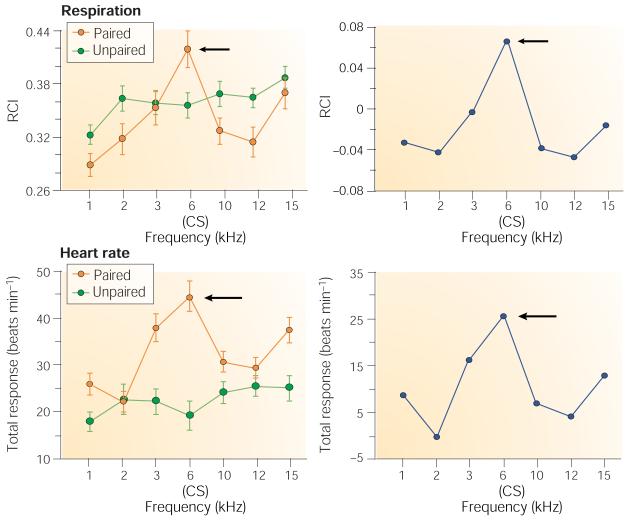

Although these findings show that the NB/ACh system can induce the same A1 plasticity that develops during learning, they do not speak directly to the issue of learning and memory. McLin et al.120,121 asked whether NB mechanisms are sufficient to produce a predicted specific behavioural memory. Rats received NB stimulation paired with a 6-kHz tone; a control group received unpaired stimulation. After training, they were tested in the absence of any NB stimulation. The specificity of behavioural effects was assessed by recording heart rate and respiration, using the well-established metric of the stimulus generalization gradient which is obtained when subjects trained with one stimulus are subsequently tested with many stimuli. If paired NB stimulation induces associative memory for the training tone, then this tone (6 kHz) should later elicit the largest behavioural responses of all tones tested.

Tone–NB pairing did induce CS-specific behavioural memory — the CS frequency of 6 kHz elicited the strongest cardiac and respiratory responses of any test frequency (Fig. 7). The subjects behaved as though they had learned that 6 kHz had acquired increased behavioural significance through a learning experience. The findings meet the dual criteria of associativity and specificity that have long been accepted as sufficient to allow memory to be inferred from behavioural change. Pairing induced another form of highly specific plasticity in A1, an increase in the power of high-frequency gamma waves in the electroencephalogram (EEG), which have been linked to memory formation122. These findings indicate that pairing a tone with NB stimulation not only can induce cortical plasticity but also is sufficient for the formation of specific auditory associative memory. Overall, the results of NB studies support the hypothesis that this system is sufficient to be normally engaged by sensory stimuli and to produce both specific memory traces in A1 and specific behavioural memory.

Rats received either a 6-kHz tone paired with NB stimulation or the two stimuli unpaired. Twenty-four hours after the end of training, behavioural generalization gradients were obtained by presenting the CS and several other frequencies. Left: both interruption of ongoing respiratory rhythm and change in heart rate were maximal at the CS frequency for the paired group. Right: differences between groups (paired minus unpaired) reveal the associative, specific behavioural effect at the CS frequency, indicating the induction of specific behavioural memory. Modified, with permission, from ref. 120 © (2002) National Academy of Sciences USA. RCI, respiration change index.

Conclusions

Converging findings from various experimental approaches show that the primary auditory cortex is directly implicated in the storage of specific information about auditory experiences. Physiological plasticity induced by associative processes is highly specific to acoustic frequencies that become behaviourally important, and this plasticity has the main features of associative memory: it can be rapidly acquired, become stronger in the absence of additional training (consolidates), and is retained for long periods of time. The mechanisms that underlie the induction of such long-term specific memory traces include the NB cholinergic system, which can induce the formation of both specific plasticity and specific behavioural memory. Of course, the storage of any given experience is probably multi-modal and multidimensional, so that A1 probably constitutes one component of a complex network of storage sites.

The emerging picture of A1 transcends the analysis of pure stimulus features because its role also includes the analysis and storage of the behavioural significance of those features. Beyond the associative processes reviewed here, current research is increasingly uncovering other cognitive functions of A1. These include slowly developing facilitated discrimination of various stimulus features by perceptual learning123,124, learning of complex tasks125, rapid ‘on-line’ adjustments to maximize attentive capture of stimulus elements126, the processing of abstract features such as acoustic objects127 and categories128, and even the encoding of acoustically dependent, planned behavioural acts129,130. It will be important to integrate the diversity of emerging cognitive functions with core sensory functions. Another important challenge is to formulate a broader functional conceptualization of the primary auditory cortex and perhaps of the primary cortices of other sensory modalities.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge support by research grants from the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders and from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Glossary

| receptive field | That limited domain of the sensory environment to which a given sensory neuron is responsive, for example, a limited frequency band in audition or a limited area of space in vision |

| tonotopic map | An area in the auditory system in which neighbouring cells are most sensitive to acoustic frequencies that are adjacent to their own preferred threshold frequencies |

| bradycardia | Slowing of heart rate. It is often a conditioned response to a stimulus that has been paired with a negative reinforcer |

| sensitization | An increased response to a neutral stimulus caused by an increase in general arousal or behavioural excitability, often produced by presentation of a noxious stimulus |

| best frequency | Within the receptive field for frequency of an auditory system neuron, the frequency that elicits the greatest cellular response |

| consolidation | A growth in the strength of memory across time after an experience, often inferred from increasing resistance to memory disruption with increasing time or directly measured as increasing strength of neural response over time |

| nucleus basalis | A group of neurons deep within the cerebral hemispheres that release acetylcholine (ACh) widely to the cerebral cortex |

| characteristic frequency | The acoustic frequency to which an auditory neuron is tuned at its threshold of response |

| frequency tuning shift | A change in the frequency tuning of an auditory neuron from its original best frequency to another frequency, often the result of increased behavioural importance of another frequency |

| reinforcer | A stimulus that is paired with and immediately follows presentation of a biologically neutral stimulus, such as a tone. Reinforcers are usually biologically important, such as food or shock |

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The author declares that he has no competing financial interests.

FURTHER INFORMATION

Norman Weinberger’s homepage: http://darwin.bio.uci.edu/neurobio/Faculty/Weinberger/weinberger.htm

The Music and Science Information Computer Archive: http://www.musica.uci.edu

Center for the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory: http://www.cnlm.uci.edu

Access to this interactive links box is free online.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1366

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3590000

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Functional diversities within neurons and astrocytes in the adult rat auditory cortex revealed by single-nucleus RNA sequencing.

Sci Rep, 14(1):25314, 25 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39455606 | PMCID: PMC11511993

Analyzing the transient response dynamics of long-term depression in the mouse auditory cortex in vitro through multielectrode-array-based spatiotemporal recordings.

Front Neurosci, 18:1448365, 12 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39328422 | PMCID: PMC11424455

Modeling short visual events through the BOLD moments video fMRI dataset and metadata.

Nat Commun, 15(1):6241, 24 Jul 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 39048577 | PMCID: PMC11269733

Auditory discrimination learning differentially modulates neural representation in auditory cortex subregions and inter-areal connectivity.

Cell Rep, 43(5):114172, 02 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38703366 | PMCID: PMC11450637

Emergence of Emotion Selectivity in Deep Neural Networks Trained to Recognize Visual Objects.

PLoS Comput Biol, 20(3):e1011943, 28 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38547053 | PMCID: PMC10977720

Go to all (344) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Physiological memory in primary auditory cortex: characteristics and mechanisms.

Neurobiol Learn Mem, 70(1-2):226-251, 01 Jul 1998

Cited by: 154 articles | PMID: 9753599

Review

The nucleus basalis and memory codes: auditory cortical plasticity and the induction of specific, associative behavioral memory.

Neurobiol Learn Mem, 80(3):268-284, 01 Nov 2003

Cited by: 110 articles | PMID: 14521869

Review

Associative representational plasticity in the auditory cortex: a synthesis of two disciplines.

Learn Mem, 14(1-2):1-16, 03 Jan 2007

Cited by: 135 articles | PMID: 17202426 | PMCID: PMC3601844

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Auditory associative memory and representational plasticity in the primary auditory cortex.

Hear Res, 229(1-2):54-68, 17 Jan 2007

Cited by: 105 articles | PMID: 17344002 | PMCID: PMC2693954

Review Free full text in Europe PMC