Abstract

Free full text

Epigenetic inactivation of SLIT3 and SLIT1 genes in human cancers

Abstract

In Drosophila, the Slit gene product, a secreted glycoprotein, acts as a midline repellent to guide axonal development during embryogenesis. Three human Slit gene orthologues have been characterised and recently we reported frequent promoter region hypermethylation and transcriptional silencing of SLIT2 in lung, breast, colorectal and glioma cell lines and primary tumours. Furthermore, re-expression of SLIT2 inhibited the growth of cancer cell lines so that SLIT2 appears to function as a novel tumour suppressor gene (TSG). We analysed the expression of SLIT3 (5q35–34) and SLIT1 (1q23.3–q24) genes in 20 normal human tissues. Similar to SLIT2 expression profile, SLIT3 is expressed strongly in many tissues, while SLIT1 expression is neuronal specific. We analysed the 5′ CpG island of SLIT3 and SLIT1 genes in tumour cell lines and primary tumours for hypermethylation. SLIT3 was found to be methylated in 12 out of 29 (41%) of breast, one out of 15 (6.7%) lung, two out of six (33%) colorectal and in two out of (29%) glioma tumour cell lines. In tumour cell lines, silenced SLIT3 associated with hypermethylation and was re-expressed after treatment with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. In primary tumours, SLIT3 was methylated in 16% of primary breast tumours, 35% of gliomas and 38% of colorectal tumours. Direct sequencing of bisulphite-modified DNA from methylated tumour cell lines and primary tumours demonstrated that majority of the CpG sites analysed were heavily methylated. Thus, both SLIT2 and SLIT3 are frequently methylated in gliomas and colorectal cancers, but the frequency of SLIT3 methylation in lung and breast cancer is significantly less than that for SLIT2. We also demonstrated SLIT1 promoter region hypermethylation in glioma tumour lines (five out of six; 83%), the methylation frequency in glioma tumours was much lower (two out of 20; 10%). Hence, evidence is accumulating for the involvement of members of the guidance cues molecules and their receptors in tumour development.

Epigenetic inactivation of tumour suppressor genes (TSGs) by promoter region CpG island hypermethylation is now well documented and several TSGs have been demonstrated to be inactivated by this mechanism (reviewed in Jones and Baylin, 2002; Herman and Baylin, 2003). In more recent years, a novel class of TSGs has been identified where epigenetic inactivation plays the predominant role, while somatic mutations are rare. This class of genes is exemplified by the 3p21.3 TSG, Ras association domain family 1A gene (RASSF1A) (Dammann et al, 2000; Lerman and Minna, 2000; Agathanggelou et al, 2001; Burbee et al, 2001). The CpG island in the promoter region of isoform A is frequently and heavily methylated in many types of cancers, including lung, breast, kidney, NPC, gastric, bladder, neuroblastoma, testicular, etc. (reviewed in Pfeifer et al, 2002; Dammann et al, 2003), while somatic inactivating mutations are absent or rare.

SLITs, ROBOs and Semaphorins belong to families of proteins that play important roles in axon guidance and cell migration in Drosophila and vertebrates (reviewed in Brose and Tessier-Lavigne, 2000; Wong et al, 2002). These proteins are widely expressed in mammalian tissues and the expression is not confined to neurons. Hence, they may have other yet unidentified roles. Slits are secreted proteins that are ligands for the Robo receptors (Brose et al, 1999; Kidd et al, 1999; Li et al, 1999). Recently, Slit was shown to inhibit leucocyte chemotaxis, this inhibition appears to be mediated by Robo (Wu et al, 2001). In mammals, four Robo genes have so far been identified, Robo1, Robo2, Rig-1 (Robo3) and magic Robo (Robo4) (Kidd et al, 1998; Sundaresan et al, 1998; Yuan et al, 1999; Huminiecki et al, 2002). In humans, ROBO1 is located at 3p12 within a critical region of overlapping homozygous deletions in lung and breast cancers (Sundaresan et al, 1998). This region also demonstrated a high frequency of allele loss in lung, kidney and breast cancers. Majority of mice with deletion of exon 2 of Robo1 die at birth because of delayed lung maturation, the surviving mice develop bronchial hyperplasia (Xian et al, 2001). In an earlier study, we demonstrated that there were no inactivating somatic mutations in ROBO1 in lung and breast cancers, but a CpG island in the 5′ region of ROBO1 was hypermethylated in breast and kidney tumours (Dallol et al, 2002b). We went on to analyse the ligand SLIT2 located at 4p15.2 for genetic/epigenetic inactivation in tumours. The 4p15.2 region shows frequent allele loss in lung, breast, colorectal and head and neck cancers. SLIT2 promoter region CpG island was found to be frequently hypermethylated in lung, breast, colorectal and glioma tumours, while somatic mutations were not found (Dallol et al, 2002a, 2003a, 2003b). Furthermore, we demonstrated in vitro growth suppression when SLIT2 was expressed in tumour cell lines that had no endogenous SLIT2 expression due to methylation. A recent paper demonstrated that in mice slit2 homozygous deficiency was lethal (Plump et al, 2002).

In this report, we analysed the methylation status of 5′ CpGs islands for the remaining SLIT gene family members (SLIT3 and SLIT1) in human cancers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and samples

A total of 60 glioma samples, plus seven glioma tumour cell lines (T17, U87-MG, A172, U343, HS683, U373, H4) were analysed for methylation. Among the glioma samples, 40 were classified as gliomblastoma multiforme. The remaining gliomas were collected randomly and consisted of all grades. In addition, 32 colorectal cancer samples and their matching histologically normal mucosa, six colorectal tumour cell lines (SW48, HCT116, LS411, LS174T, DLD1, LoVo), 15 lung tumor cell lines, 32 invasive ductal breast carcinoma plus 29 breast tumour cell lines were also analysed for methylation. These have been described previously (Dallol et al, 2002a, 2003a, 2003b)

Bisulphite modification and methylation analysis

Bisulphite DNA sequencing was performed as described previously (Agathanggelou et al, 2001). Briefly, 0.5–1.0 μg of genomic DNA was denatured in 0.3

μg of genomic DNA was denatured in 0.3 M NaOH for 15

M NaOH for 15 min at 37°C. Unmethylated cytosine residues were then sulphonated by incubation in 3.12

min at 37°C. Unmethylated cytosine residues were then sulphonated by incubation in 3.12 M sodium bisulphite (pH 5.0) (Sigma, Dorset, UK) and 5

M sodium bisulphite (pH 5.0) (Sigma, Dorset, UK) and 5 mM hydroquinone (Sigma) in a thermocycler (Hybaid) for 15

mM hydroquinone (Sigma) in a thermocycler (Hybaid) for 15 s at 99°C and 15

s at 99°C and 15 min at 50°C for 20 cycles. Sulphonated DNA was then recovered using the Wizard DNA cleanup system (Promega, Southampton, UK) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The DNA was desulphonated by addition of 0.3

min at 50°C for 20 cycles. Sulphonated DNA was then recovered using the Wizard DNA cleanup system (Promega, Southampton, UK) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The DNA was desulphonated by addition of 0.3 M NaOH for 10

M NaOH for 10 min at room temperature. The converted DNA was then ethanol precipitated and resuspended in water.

min at room temperature. The converted DNA was then ethanol precipitated and resuspended in water.

Combined bisulphite restriction analysis (COBRA) and sequencing

All reactions were performed on a thermocylcer (Hybaid) and with HotStar Taq Polymerase (Quiagen, West Sussex, UK). The promoter methylation status of SLIT3 and SLIT1 were determined using the COBRA method followed by sequencing to confirm methylation and ascertain the extent of methylation. The cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation for 10 min at 95°C, followed by 25–35 cycles of 1

min at 95°C, followed by 25–35 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1

min at 95°C, 1 min at annealing temperature and 2

min at annealing temperature and 2 min at 74°C with a final extension for 5

min at 74°C with a final extension for 5 min at 74°C using the forward and reverse primers. The reaction volume of 20

min at 74°C using the forward and reverse primers. The reaction volume of 20 μl contained 40

μl contained 40 ng bisulphate-modified DNA, 1 × PCR Buffer containing 1.5

ng bisulphate-modified DNA, 1 × PCR Buffer containing 1.5 mM MgCl2 (Quiagen), 0.2

mM MgCl2 (Quiagen), 0.2 M dNTPs, 0.4

M dNTPs, 0.4 μM each primer and 0.5

μM each primer and 0.5 U HotStar Taq (Qiagen). Then, 1

U HotStar Taq (Qiagen). Then, 1 μl of this reaction was used in a seminested PCR reaction (50

μl of this reaction was used in a seminested PCR reaction (50 μl) using forward and reverse nested primers in the case of SLIT3 and reverse and forward nested primers for SLIT1. The same PCR programme and concentration of reagents were used as before. The annealing temperature, MgCl2 concentration and sequences for the gene primers are listed in Table 1

(Y=C or T and R=A or G). All PCR products were assayed for methylation by incubation with BstUI at 60°C or TaqαI at 65°C for 2

μl) using forward and reverse nested primers in the case of SLIT3 and reverse and forward nested primers for SLIT1. The same PCR programme and concentration of reagents were used as before. The annealing temperature, MgCl2 concentration and sequences for the gene primers are listed in Table 1

(Y=C or T and R=A or G). All PCR products were assayed for methylation by incubation with BstUI at 60°C or TaqαI at 65°C for 2 h before visualisation on a 2% agarose gel with added ethidium bromide. The CpG island methylation status for SLIT3 was determined by cloning PCR products into pGEM T-Easy vector (Promega – according to manufacturers’ instructions). At least five clones from each PCR product were then prepared for sequencing. SLIT3 Colony PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Columns (Quiagen – according to manufacturers’ instructions) and then reamplified using ABI BigDye Cycle Sequencing Kit (Perkin-Elmer, Warrington, UK) with the reverse nested primer (as shown in Figure 2A). The SLIT1 COBRA PCR products were purified and then sequenced directly as described above, but with the reverse primer. The reactions were then analysed using an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin–Elmer).

h before visualisation on a 2% agarose gel with added ethidium bromide. The CpG island methylation status for SLIT3 was determined by cloning PCR products into pGEM T-Easy vector (Promega – according to manufacturers’ instructions). At least five clones from each PCR product were then prepared for sequencing. SLIT3 Colony PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Columns (Quiagen – according to manufacturers’ instructions) and then reamplified using ABI BigDye Cycle Sequencing Kit (Perkin-Elmer, Warrington, UK) with the reverse nested primer (as shown in Figure 2A). The SLIT1 COBRA PCR products were purified and then sequenced directly as described above, but with the reverse primer. The reactions were then analysed using an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin–Elmer).

Table 1

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) | Annealing temp. for PCR (°C) | MgCl2 conc. (mM) | Predicted product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLIT3 COBRA F | GGT-TAG-TTT-ATT-YGG-TYG-TTT-YGT-G TT-TTA-GT | 55 | 1.5 | 394 |

| SLIT3 COBRA R | TAC-CCA-CCC-RAA-AAC-CAT-AAT-ATA-CAA-AA | |||

| SLIT3 COBRA RN | CCA-CTC-CTA-AAA-AAA-ACT-ACC-TCT-A | |||

| SLIT1 COBRA F | GTT-TAT-TTT-TTT-TTT-YGT-AGT-AGT-TAG-TTG-GGA-GT | 57 | 1.5 | 370 |

| SLIT1 COBRA R | TAA-CAA-TCC-ACC-RTA-ATT-CCR-ATA-CAA-ATA-CAA-AAA | |||

| SLIT1 COBRA FN | GGY-GAA-AYG-GTA-GAG-GAG-TYG-AGT-TTT-T | |||

| GAPDH expression F | TGA-AGT-TCG-GAG-TCA-ACG-GAT-TTG-GT | 60 | 1.5 | 982 |

| GAPDH expression R | CAT-GTG-GGC-CAT-GAG-GTC-CAC-CAC | |||

| SLST3 expression F | CAA-GTG-TGC-CGA-GGG-CTA-TGG-AG | 65 | 1.5 | 419 |

| SLIT3 expression R | ACG-GG C-TTA-GGA-ACA-CGC-GAG-G | |||

| SLIT1 expression F | GTG-ACA-ACT-GCA-GTG-AGA-AC | 55 | 1.5 | 422 |

| SLIT 1 expression R | GTA-CAG-CTC-AAC-TGC-AAT-GT |

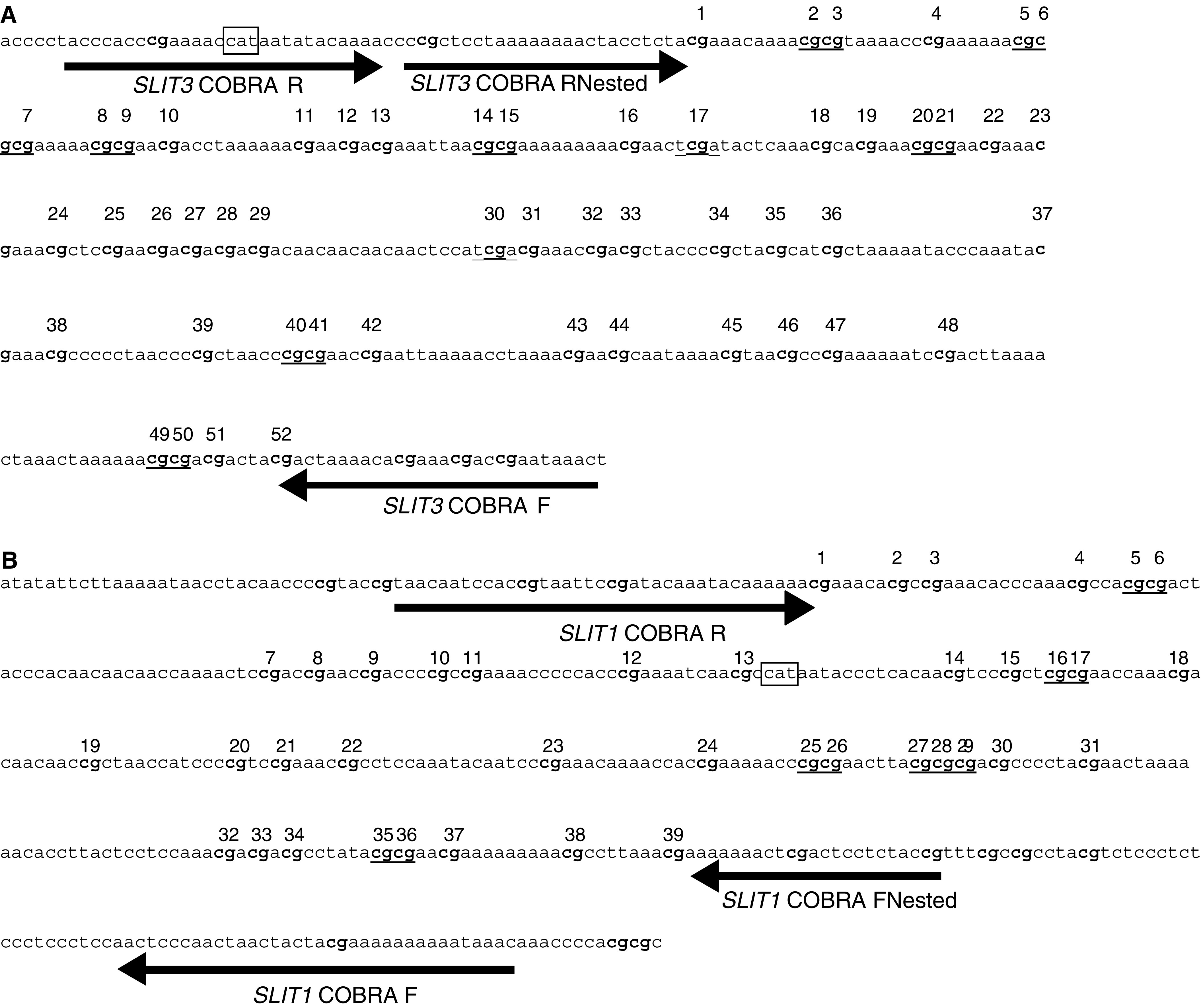

(A) Sequence of the reverse bisulphate-modified SLIT3 promoter region CpG island fragment. Arrows indicate the position of the primers for COBRA. CG dinucleotides within the amplification region are numbered 1–52 and sequences underlined are BstUI and TaqI sites used to detect methylation. The expected amplicon size from SLIT3 COBRA F to SLIT3 COBRA RNested is 394 bp. The box represents the transcriptional start site of SLIT3. (B) Sequence of the reverse bisulphate-modified SLIT1 promoter region CpG island fragment. Arrows indicate the position of the primers for COBRA. CG dinucleotides within the amplification region are numbered 1–39 and sequences underlined are BstUI sites used to detect methylation. The expected amplicon size for SLIT1 FNested to SLIT1 R is 370

bp. The box represents the transcriptional start site of SLIT3. (B) Sequence of the reverse bisulphate-modified SLIT1 promoter region CpG island fragment. Arrows indicate the position of the primers for COBRA. CG dinucleotides within the amplification region are numbered 1–39 and sequences underlined are BstUI sites used to detect methylation. The expected amplicon size for SLIT1 FNested to SLIT1 R is 370 bp. The box represents the transcriptional start site of SLIT1.

bp. The box represents the transcriptional start site of SLIT1.

Real-time RT–PCR

The theoretical and practical aspects of real-time quantitative RT–PCR using the ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (Perkin–Elmer) have been described in detail elsewhere (Dallol et al, 2002a). Briefly, total RNA was reverse transcribed before real-time PCR amplification. Quantitative values were obtained from the threshold cycle (Ct) number at which the increase in the signal associated with exponential growth of PCR products begins to be detected using the PE Biosystems analysis software, according to the manufacturers’ manuals. The precise amount of total RNA added to each reaction mix and the quality was difficult to assess. We therefore also quantified transcripts of the gene RPLPO (also known as 36B4) encoding human acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein PO as the endogenous RNA control, and each sample was normalised on the basis of its RPLPO content. Results, expressed as N-fold differences in target gene expression relative to the RPLPO gene, termed ‘Ntarget’, were determined by the formula: Ntarget=2ΔCtsample, where ΔCt value of the sample was determined by subtracting the Ct value of the target gene from the Ct value of the RPLPO gene. The nucleotide sequences of the primers used for PCR amplification were the following: SLIT1-U (5′-CTGGATGGCTTGAGGACCCTAAT-3′) and SLIT1-L (5′-GCCCGTGAAGCTGTCGTTGT-3′) with a SLIT1-specific product size of 72 bp, SLIT3-U (5′-GAATATGTCACCGACCTGCGACT-3′) and SLIT3-L (5′-GCAGGTTGGGCAACTTCTTGA-3′) with a SLIT3-specific product size of 85

bp, SLIT3-U (5′-GAATATGTCACCGACCTGCGACT-3′) and SLIT3-L (5′-GCAGGTTGGGCAACTTCTTGA-3′) with a SLIT3-specific product size of 85 bp, and RPLPO-U (5′-GGCGACCTGGAAGTCCAACT-3′) and RPLPO-L (5′-CCATCAGCACCACAGCCTTC-3′) with a RPLPO-specific product size of 149

bp, and RPLPO-U (5′-GGCGACCTGGAAGTCCAACT-3′) and RPLPO-L (5′-CCATCAGCACCACAGCCTTC-3′) with a RPLPO-specific product size of 149 bp. PCR was performed using the SYBR® Green PCR Core Reagents kit (Perkin–Elmer). To avoid amplification of contaminated genomic DNA, one of the two primers was placed at the junction between two exons. The thermal cycling conditions comprised of an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 10

bp. PCR was performed using the SYBR® Green PCR Core Reagents kit (Perkin–Elmer). To avoid amplification of contaminated genomic DNA, one of the two primers was placed at the junction between two exons. The thermal cycling conditions comprised of an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min and 50 cycles of 95°C for 15

min and 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 65°C for 1

s and 65°C for 1 min.

min.

Cell lines and 5-aza-2′ deoxycytidine treatment

Breast, colorectal and glioma tumour cell lines were routinely maintained in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% FCS at 37°C, 5% CO2. 5–10 × 105 cells were plated and allowed 24 h growth before addition of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Sigma). The medium was changed 24

h growth before addition of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Sigma). The medium was changed 24 h after treatment and then every 3 days. RNA was prepared at 5 and 7 days after treatment using the Rneasy kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturers’ instructions.

h after treatment and then every 3 days. RNA was prepared at 5 and 7 days after treatment using the Rneasy kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturers’ instructions.

Expression analysis

Breast, colorectal and glioma cell line were treated with 5 μM demethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine freshly prepared in ddH2O and filter-sterilised. Extracted RNA (1

μM demethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine freshly prepared in ddH2O and filter-sterilised. Extracted RNA (1 μg) was used as a template for cDNA synthesis using SuperScript™ III RNase H− Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen – according to the manufacturers’ instructions). In total, 2

μg) was used as a template for cDNA synthesis using SuperScript™ III RNase H− Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen – according to the manufacturers’ instructions). In total, 2 μl (10%) of the first strand reaction was used for PCR (Invitrogen – according to the manufacturers’ instructions). Primers used for SLIT1, SLIT3 and GAPDH RT–PCR are described in Table 1. The PCR theromocycle (Hybaid) consisted of an initial denaturation of 10

μl (10%) of the first strand reaction was used for PCR (Invitrogen – according to the manufacturers’ instructions). Primers used for SLIT1, SLIT3 and GAPDH RT–PCR are described in Table 1. The PCR theromocycle (Hybaid) consisted of an initial denaturation of 10 min at 95°C followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30

min at 95°C followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, annealing temperature for 30

s, annealing temperature for 30 s, 72°C for 30

s, 72°C for 30 s and a final extension of 5

s and a final extension of 5 min at 72°C. PCR products were visualised on a 2% agarose gel with added ethidium bromide.

min at 72°C. PCR products were visualised on a 2% agarose gel with added ethidium bromide.

RESULTS

SLIT1 and SLIT3 expression analysis in normal tissues using quantitative real-time RT–PCR

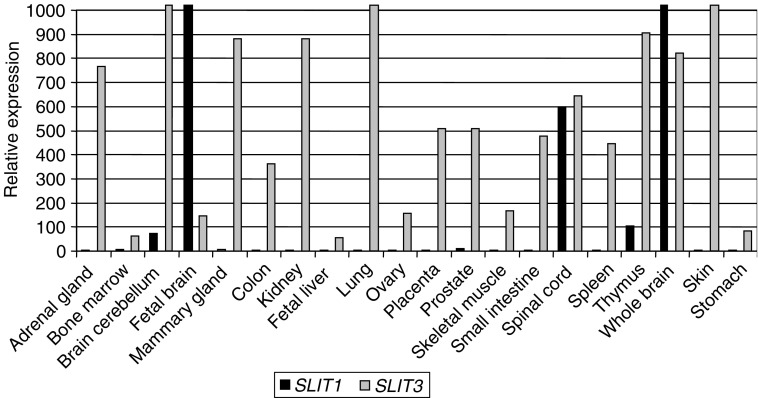

We investigated the expression pattern of SLIT1 and SLIT3 genes in a wide range of normal human tissues using quantitative real-time RT–PCR (see Materials and Methods). SLIT3 was expressed in majority of tissues analysed, with the highest expression in skin, brain cerebellum and lung and lowest expression in fetal liver, bone marrow and stomach. While, SLIT1 expression was much more restricted (brain and nervous system) (Figure 1).

Epigenetic inactivation of the SLIT3 gene in tumour cell lines

The SLIT3 putative promoter region was predicted by Promoter Inspector software (http://www.genomatrix.de). This region is from −576 to +9 relative to the translation start site. This region fulfilled the criteria of a CpG island with a GC content of 77% and an observed :

: expected CpG ratio of 0.86 (CpG plot programme at

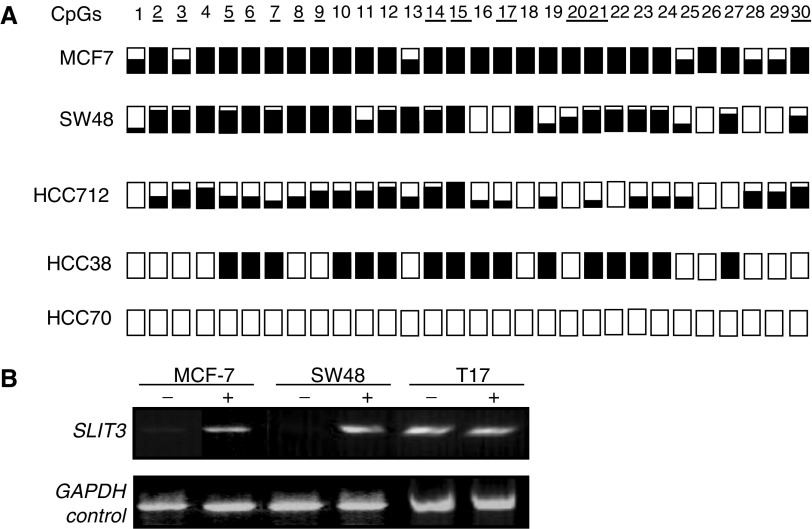

http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/). We investigated the methylation status of this 5′ CpG island associated with the SLIT3 gene in various human tumour cell lines. For this analysis, we utilised the COBRA assay on bisulphite-modified DNA. Figure 2A shows the sequence of the region analysed and the primers used (sequence shown is reverse strand bisulphite modified and all CG methylated), TaqI and BstUI sites are underlined. This CpG island was found to be hypermethylated in 12 out of 29 (41%) breast, one out of three (33%) NSCLC, zero out of 12 (0%) SCLC, two out of six (33.3) colorectal and in two out of seven (29%) glioma tumour cell lines. The COBRA PCR products were cloned and several clones of each tumour cell line were sequenced to determine the pattern and extent of methylation. As seen in Figure 3A, majority of the 30 CG dinucleotides were hypermethylated for MCF-7, HCC712 and HCC38 (breast tumour lines) and SW48 (colorectal tumour line), while breast tumour cell line HCC70 was unmethylated. SLIT3 expression was restored in tumour lines that were heavily methylated (MCF-7 and SW48) by treating the cell lines with 5aza-2-deocycytidine (Figure 3B), while the unmethylated glioma tumour cell line T17 did not show any change in expression.

expected CpG ratio of 0.86 (CpG plot programme at

http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/). We investigated the methylation status of this 5′ CpG island associated with the SLIT3 gene in various human tumour cell lines. For this analysis, we utilised the COBRA assay on bisulphite-modified DNA. Figure 2A shows the sequence of the region analysed and the primers used (sequence shown is reverse strand bisulphite modified and all CG methylated), TaqI and BstUI sites are underlined. This CpG island was found to be hypermethylated in 12 out of 29 (41%) breast, one out of three (33%) NSCLC, zero out of 12 (0%) SCLC, two out of six (33.3) colorectal and in two out of seven (29%) glioma tumour cell lines. The COBRA PCR products were cloned and several clones of each tumour cell line were sequenced to determine the pattern and extent of methylation. As seen in Figure 3A, majority of the 30 CG dinucleotides were hypermethylated for MCF-7, HCC712 and HCC38 (breast tumour lines) and SW48 (colorectal tumour line), while breast tumour cell line HCC70 was unmethylated. SLIT3 expression was restored in tumour lines that were heavily methylated (MCF-7 and SW48) by treating the cell lines with 5aza-2-deocycytidine (Figure 3B), while the unmethylated glioma tumour cell line T17 did not show any change in expression.

(A) SLIT3 CpG island COBRA PCR products were cloned and sequenced from breast (MCF7, HCC712, HCC38 and HCC70) and colorectal (SW48) tumour cell lines. For each tumour cell line, several clones were sequenced and the methylation status for the first 30 CpGs is shown. White and black squares represent unmethylated and methylated CpGs, respectively. Partially filled squares represent partially methylated CpGs. (B) Expression of SLIT3 in methylated breast (MCF7) and colorectal (SW48) cell lines before and after treatment with the demethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-aza dC). Gene expression was restored by 5-aza-dC (+) in methylated cell lines that lacked SLIT3 expression. GAPDH and the unmethylated glioma cell line T17 were used as positive controls to ensure RNA integrity and equal loading.

Epigenetic inactivation of the SLIT3 gene in primary tumours

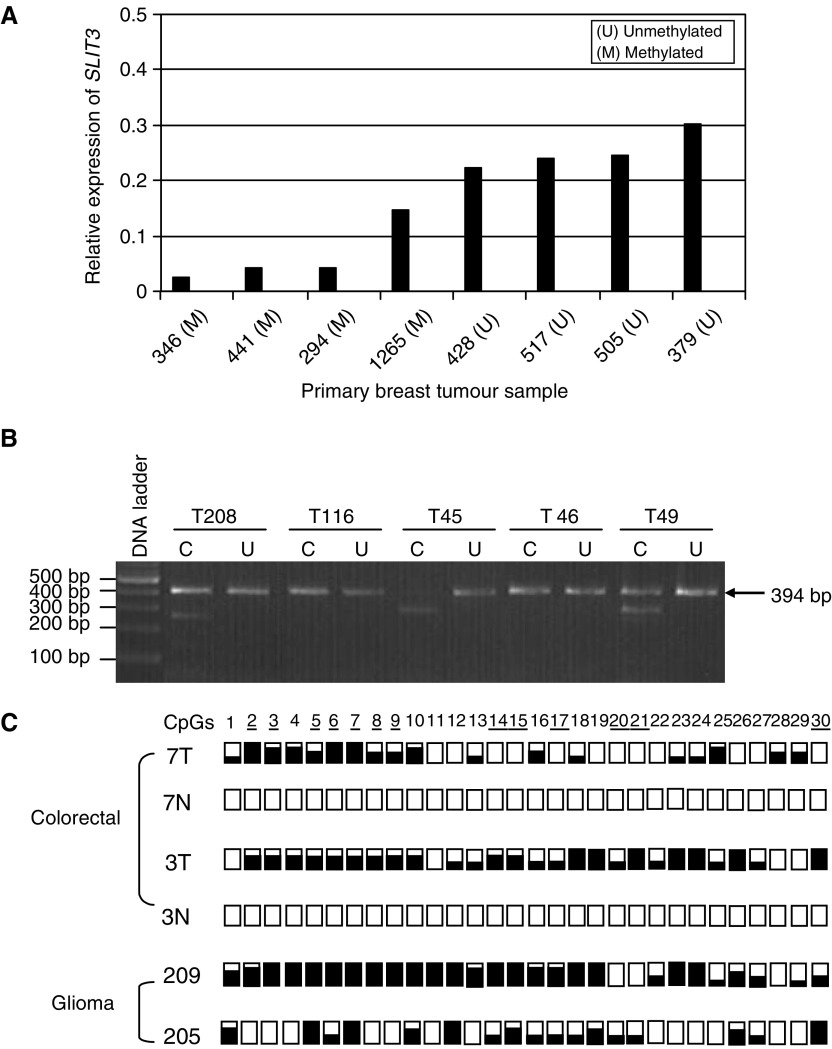

We then analysed the methylation status of the above CpG island in primary tumours using COBRA analysis followed by sequencing of the cloned PCR products. Five out of 32 (16%) breast tumours were found to be methylated for SLIT3. Using real-time RT–PCR, we demonstrated that the SLIT3 methylation in breast tumours correlated with reduced SLIT3 expression as compared to unmethylated breast tumours (Figure 4A). SLIT3 5′ CpG island was also hypermethylated in 12 out of 32 (37.5%) colorectal tumours and in 21 out of 60 (35%) glioma primary tumours. Since the tumour samples used in this study were not microdissected, in majority of the primary tumors unmethylated bands were also detected. No methylation was found in corresponding normal tissues from the colorectal or glioma patients or in the DNA isolated from normal brains. Similar to the tumour cell line data, sequencing of cloned PCR products confirmed that majority of the 30 CG dinculeotides analysed were methylated in primary tumours (Figure 4B, C).

(A) Relative expression of SLIT3 gene in methylated (M) and unmethylated (U) breast tumours using real-time RT–PCR as described in Materials and Methods (B) BstUI digest of SLIT3 CpG island COBRA PCR products from glioma (T208, T116, T45) and colorectal (T46, T49) primary tumours. (C) COBRA PCR products from glioma and colorectal primary tumours were cloned and sequenced. For each tumour, several clones were sequenced and the methylation status for the first 30 CpGs is shown. White and black squares represent unmethylated and methylated CpGs, resepectively. Partially filled squares represent partially methylated CpGs. 7T and 3T represent colorectal tumours, 7N and 3N represent corresponding normal colon samples. 209T and 205T represent glioma tumours.

Epigenetic inactivation of SLIT1 gene in gliomas

The SLIT1 CpG island was predicted to be from −574 to +192 and had a GC content of 71% and had an observed :

: expected CpG ratio of 0.81 (CpG plot programme at

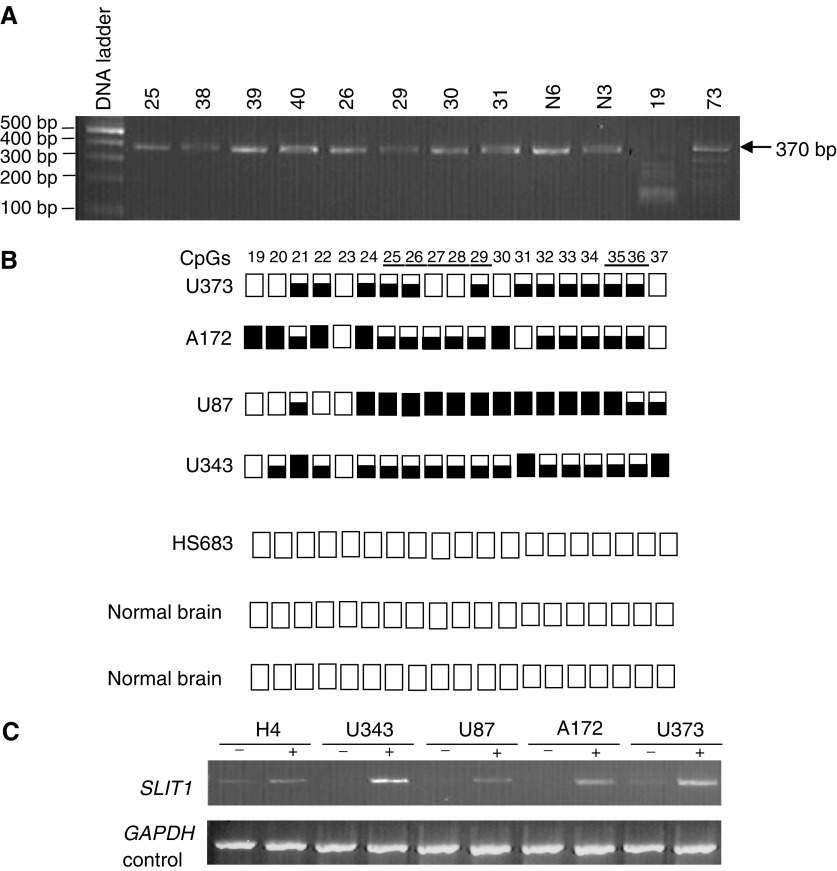

http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/). This region overlapped with the SLIT1 putative promoter region predicted by Promoter Inspector software (http://www.genomatrix.de). Since SLIT1 expression is neuronal specific, we analysed the methylation status of the 5′ CpG island of the SLIT1 gene in glioma tumour cell lines and primary tumours by COBRA and direct sequencing of bisulphite-modified DNA (Figure 2B). Five out of six (83%) glioma tumour lines were methylated, while only two of 20 (10%) glioma tumours demonstrated SLIT1 methylation (Figure 5A, B). No methylation was found in DNA isolated from normal brains. SLIT1 expression was restored/upregulated in five glioma tumour lines (methylated for SLIT1) by treatment with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Figure 5C).

expected CpG ratio of 0.81 (CpG plot programme at

http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/). This region overlapped with the SLIT1 putative promoter region predicted by Promoter Inspector software (http://www.genomatrix.de). Since SLIT1 expression is neuronal specific, we analysed the methylation status of the 5′ CpG island of the SLIT1 gene in glioma tumour cell lines and primary tumours by COBRA and direct sequencing of bisulphite-modified DNA (Figure 2B). Five out of six (83%) glioma tumour lines were methylated, while only two of 20 (10%) glioma tumours demonstrated SLIT1 methylation (Figure 5A, B). No methylation was found in DNA isolated from normal brains. SLIT1 expression was restored/upregulated in five glioma tumour lines (methylated for SLIT1) by treatment with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Figure 5C).

(A) BstUI digest of SLIT1 COBRA PCR products from glioma grade IV tumours and normal brain (N6 and N3) which were included as negative controls for methylation. Tumours 19 and 73 show digestion with BstUI. (B) SLIT1 COBRA PCR products were directly sequenced from glioma tumour cell lines and normal brain. The methylation status from CpG 19–37 is shown. White and black squares represent unmethylated and methylated CpGs, respectively. Partially filled squares represent partially methylated CpGs. Glioma tumour cell line Hs683 is unmethylated for SLIT1 (C) Expression of SLIT1 in glioma tumour cell lines before and after treatment with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. GAPDH was used as positive control to ensure RNA integrity and equal loading.

DISCUSSION

The Slit genes encode ligands for the roundabout (robo) receptors. The Slit–Robo interactions mediate the repulsive cues on axons and growth cones during neural development. The Slit family comprises of large extracellular matrix-secreted and membrane-associated glycoproteins with multiple functional domains (reviewed in Brose and Tessier-Lavigne, 2000). Slit genes have been identified in Drosophila, Caenorhabditis elegans, Xenopus, chickens, mice, rats and humans. There are three known mammalian SLIT genes (SLIT1, SLIT2, SLIT3) located on chromosome 10q23.3–q24, 4p15.2 and 5q35–q34, respectively. slit2 and slit3 genes are expressed in neuronal as well as nonneuronal tissues, while slit1 expression is specific to the brain (Wu et al, 2001 and this report). Slit2 homozygous deficiency in mice is lethal, while Slit1 and Slit3 homozygous mice are viable (Plump et al, 2002; Yuan et al., 2003).

In our earlier studies, we demonstrated that the ligand (SLIT2) for robo1 receptor was frequently methylated in lung, breast, colorectal and glioma tumours and that the methylation correlated with loss of SLIT2 expression. More recently, we demonstrated SLIT2 methylation in neuroblastoma, Wilms’ tumour and renal cell carcinoma (Astuti et al, 2004). Furthermore, in in vitro assays, SLIT2 suppressed tumour growth (Dallol et al, 2002a, 2003a, 2003b).

SLIT3 is located at 5q35-q34, which is a frequent region of allelic loss in colorectal and lung cancers (Girard et al, 2000; Goel et al, 2003). We have now demonstrated that SLIT3 5′ CpG island similar to SLIT2 is frequently hypermethylated in colorectal and glioma tumours and less so in breast tumours. And loss of SLIT3 expression can be reversed by treatment with a demethylating agent. While SLIT1 gene is frequently methylated in glioma tumour lines but at low frequencies in glioma tumours, hence SLIT1 may play a role in late gliomagenesis.

Slits, netrins, semaphorins and the ephrins constitute conserved families of axonal guidance cues that have prominent developmental effects. Recently, SEMA3B was also demonstrated to be inactivated in lung cancer by promoter region hypermethylation (Tomizawa et al, 2001; Kuroki et al, 2003). Re-expression of SEMA3B inhibited lung cancer cell growth and induced apoptosis.

The finding of epigenetic inactivation in various human cancers of ROBO1, SEMA3B, SLIT2 and now SLIT3 and to a lesser extent SLIT1, all of which are involved in axon and cell migration in Drosophila and vertebrates, suggests a novel, and common underlying theme for these molecules in tumour suppression.

Acknowledgments

This work was in part supported by Breast Cancer Campaign and Cancer Research UK.

References

- Agathanggelou A, Honorio S, Macartney DP, Martinez A, Dallol A, Rader J, Fullwood P, Chauhan A, Walker R, Shaw JA, Hosoe S, Lerman MI, Minna JD, Maher ER, Latif F (2001) Methylation associated inactivation of RASSF1A from region 3p21.3 in lung, breast and ovarian tumours. Oncogene 20: 1509–1518 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Astuti D, Da Silva NF, Dallol A, Gentle D, Martinsson T, Kogner P, Grundy R, Kishida T, Yao M, Latif F, Maher ER (2004) SLIT2 promoter methylation analysis in neuroblastoma, Wilms’ tumour and renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 90: 515–521 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Brose K, Bland KS, Wang KH, Arnott D, Henzel W, Goodman CS, Tessier-Lavigne M, Kidd T (1999) Slit proteins bind Robo receptors and have an evolutionarily conserved role in repulsive axon guidance. Cell 96: 795–806 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Brose K, Tessier-Lavigne M (2000) Slit proteins: key regulators of axon guidance, axonal branching, and cell migration. Curr Opin Neurobiol 10: 95–102 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Burbee DG, Forgacs E, Zöchbauer-Müller S, Shivakumar L, Gao B, Randle D, Virmani A, Bader S, Sekido Y, Latif F, Fong K, Gazdar AF, Lerman MI, White M, Minna JD (2001) Epigenetic inactivation of RASSF1A in lung and breast cancers and malignant phenotype suppression. J Natl Cancer Inst 93: 691–699 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Dallol A, Da Silva NF, Viacava P, Minna JD, Maher ER, Latif F (2002a) SLIT2, a human homologue of the Drosophila Slit2 gene, has tumor suppressor activity and is frequently inactivated in lung and breast cancers. Cancer Res 62: 5874–5880 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Dallol A, Forgacs E, Martinez A, Sekido Y, Walker R, Kishida T, Rabbitts P, Maher ER, Latif F (2002b) Tumour specific promoter region methylation of the human homologue of the Drosophila Roundabout gene DUTT1 (ROBO1) in human cancers. Oncogene 21: 3020–3028 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Dallol A, Krex D, Hesson L, Eng C, Maher ER, Latif F (2003a) Frequent epigenetic inactivation of the SLIT2 gene in gliomas. Oncogene 22: 4611–4616 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Dallol A, Morton D, Maher ER, Latif F (2003b) SLIT2 axon guidance molecule is frequently inactivated in colorectal cancer and suppresses growth of colorectal carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 63: 1054–1058 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Dammann R, Li C, Yoon JH, Chin PL, Bates S, Pfeifer GP (2000) Epigenetic inactivation of a RAS association domain family protein from the lung tumour suppressor locus 3p21.3. Nat Genet 25: 315–319 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Dammann R, Schagdarsurengin U, Strunnikova M, Rastetter M, Seidel C, Liu L, Tommasi S, Pfeifer GP (2003) Epigenetic inactivation of the Ras-association domain family 1 (RASSF1A) gene and its function in human carcinogenesis. Histol Histopathol 18: 665–677 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Girard L, Zochbauer-Muller S, Virmani AK, Gazdar AF, Minna JD (2000) Genome-wide allelotyping of lung cancer identifies new regions of allelic loss, differences between small cell lung cancer and non-small cell lung cancer, and loci clustering. Cancer Res 60: 4894–4906 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Goel A, Arnold CN, Niedzwiecki D, Chang DK, Ricciardiello L, Carethers JM, Dowell JM, Wasserman L, Compton C, Mayer RJ, Bertagnolli MM, Boland CR (2003) Characterization of sporadic colon cancer by patterns of genomic instability. Cancer Res 63: 1608–1614 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JG, Baylin SB (2003) Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation. N Engl J Med 349: 2042–2054 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Huminiecki L, Gorn M, Suchting S, Poulsom R, Bicknell R (2002) Magic roundabout is a new member of the roundabout receptor family that is endothelial specific and expressed at sites of active angiogenesis. Genomics 79: 547–552 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA, Baylin SB (2002) The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet 3: 415–428 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd T, Bland KS, Goodman CS (1999) Slit is the midline repellent for the robo receptor in Drosophila. Cell 96: 785–794 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd T, Brose K, Mitchell KJ, Fetter RD, Tessier-Lavigne M, Goodman CS, Tear G (1998) Roundabout controls axon crossing of the CNS midline and defines a novel subfamily of evolutionarily conserved guidance receptors. Cell 92: 205–215 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki T, Trapasso F, Yendamuri S, Matsuyama A, Alder H, Williams NN, Kaiser LR, Croce CM (2003) Allelic loss on chromosome 3p21.3 and promoter hypermethylation of Semaphorin 3B in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res 63: 3352–3355 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman MI, Minna JD (2000) The 630-kb lung cancer homozygous deletion region on human chromosome 3p21.3: identification and evaluation of the resident candidate tumor suppressor genes. The International Lung Cancer Chromosome 3p21.3 Tumor Suppressor Gene Consortium. Cancer Res 60: 6116–6133 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Li HS, Chen JH, Wu W, Fagaly T, Zhou L, Yuan W, Dupuis S, Jiang ZH, Nash W, Gick C, Ornitz DM, Wu JY, Rao Y (1999) Vertebrate slit, a secreted ligand for the transmembrane protein roundabout, is a repellent for olfactory bulb axons. Cell 96: 807–818 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer GP, Yoon JH, Liu L, Tommasi S, Wilczynski SP, Dammann R (2002) Methylation of the RASSF1A gene in human cancers. Biol Chem 383: 907–914 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Plump AS, Erskine L, Sabatier C, Brose K, Epstein CJ, Goodman CS, Mason CA, Tessier-Lavigne M (2002) Slit1 and Slit2 cooperate to prevent premature midline crossing of retinal axons in the mouse visual system. Neuron 33: 219–232 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaresan V, Chung G, Heppell-Parton A, Xiong J, Grundy C, Roberts I, James L, Cahn A, Bench A, Douglas J, Minna J, Sekido Y, Lerman M, Latif F, Bergh J, Li H, Lowe N, Ogilvie D, Rabbitts P (1998) Homozygous deletions at 3p12 in breast and lung cancer. Oncogene 17: 1723–1729 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tomizawa Y, Sekido Y, Kondo M, Gao B, Yokota J, Roche J, Drabkin H, Lerman MI, Gazdar AF, Minna JD (2001) Inhibition of lung cancer cell growth and induction of apoptosis after reexpression of 3p21.3 candidate tumor suppressor gene SEMA3B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 13954–13959 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wong K, Park HT, Wu JY, Rao Y (2002) Slit proteins: molecular guidance cues for cells ranging from neurons to leukocytes. Curr Opin Genet Dev 12: 583–591 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JY, Feng L, Park HT, Havlioglu N, Wen L, Tang H, Bacon KB, Jiang Zh, Zhang Xc, Rao Y (2001) The neuronal repellent Slit inhibits leukocyte chemotaxis induced by chemotactic factors. Nature 410: 948–952 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Xian J, Clark KJ, Fordham R, Pannell R, Rabbitts TH, Rabbitts PH (2001) Inadequate lung development and bronchial hyperplasia in mice with a targeted deletion in the Dutt1/Robo1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 15062–15066 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan SS, Cox LA, Dasika GK, Lee EY (1999) Cloning and functional studies of a novel gene aberrantly expressed in RB-deficient embryos. Dev Biol 207: 62–75 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan W, Rao Y, Babiuk RP, Greer JJ, Wu JY, Ornitz DM (2003) A genetic model for a central (septum transversum) congenital diaphragmatic hernia in mice lacking Slit3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 5217–5222 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Articles from British Journal of Cancer are provided here courtesy of Cancer Research UK

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602222

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.nature.com/articles/6602222.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602222

Article citations

SLIT3 deficiency promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression by modulating UBE2C/WNT signaling.

Open Life Sci, 19(1):20220956, 29 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39479352 | PMCID: PMC11524389

Clinical and Genetic Analysis of A Father-Son Duo with Monomelic Amyotrophy: Case Report.

Ann Indian Acad Neurol, 26(6):983-988, 27 Sep 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38229655 | PMCID: PMC10789418

GREM1 signaling in cancer: tumor promotor and suppressor?

J Cell Commun Signal, 17(4):1517-1526, 24 Aug 2023

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 37615860 | PMCID: PMC10713512

Perineural invasion in colorectal cancer: mechanisms of action and clinical relevance.

Cell Oncol (Dordr), 47(1):1-17, 23 Aug 2023

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 37610689 | PMCID: PMC10899381

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Role of the SLIT-ROBO signaling pathway in renal pathophysiology and various renal diseases.

Front Physiol, 14:1226341, 11 Jul 2023

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 37497439

Review

Go to all (107) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Frequent epigenetic inactivation of the SLIT2 gene in gliomas.

Oncogene, 22(29):4611-4616, 01 Jul 2003

Cited by: 96 articles | PMID: 12881718

[Analysis of the expression of Slit/Robo genes and the methylation status of their promoters in the hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines].

Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi, 17(3):198-202, 01 Mar 2009

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 19335983

Frequent epigenetic inactivation of the SLIT2 gene in chronic and acute lymphocytic leukemia.

Epigenetics, 4(4):265-269, 01 May 2009

Cited by: 36 articles | PMID: 19550140

Slits and their receptors.

Adv Exp Med Biol, 621:65-80, 01 Jan 2007

Cited by: 55 articles | PMID: 18269211

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Breast Cancer Now (1)

Role of ROBO1 (DUTT1) a candidate tumour supressor gene at 3p12 and its ligands the SLIT genes in breast cancer development.

Professor Farida Latif, University of Birmingham

Grant ID: 2001:183