Abstract

Free full text

Down-regulation of Rap1 activity is involved in ephrinB1-induced cell contraction

Abstract

Ephrins are cell surface ligands that activate Eph receptor tyrosine kinases. This ligand–receptor interaction plays a central role in the sorting of cells. We have previously shown that the ephrinB–EphB signalling pathway is also involved in the migration of intestinal precursor cells along the crypts. Using the colon cell line DLD1 expressing the EphB2 receptor, we showed that stimulation of these cells with soluble ephrinB1 results in a rapid retraction of cell extensions and a detachment of cells. On ephrinB1 stimulation, the small GTPases Rho and Ras are activated and Rap1 is inactivated. Importantly, when a constitutively active Rap1 mutant was introduced into these cells, ephrinB1-induced retraction was inhibited. From these results, we conclude that down-regulation of Rap1 is a prerequisite for ephrin-induced cell retraction in colon cells.

INTRODUCTION

Eph receptor tyrosine kinases and their membrane-bound ephrin ligands are key regulators of cell movement during development. Their interaction leads to the activation of bidirectional signalling pathways in ligand- and receptor-expressing cells. Both ligand- and receptor-mediated signals mediate repulsion, adhesion and deadhesion mechanisms involved in the motility of adherent cells [1,2]. Particularly, cell repulsion by the ephrin–Eph system plays an important role in the sorting of cells and in axon path finding. The mechanism of repulsion is only partly understood and may vary between cell types and the ephrin–Eph complex. It comprises several steps, including the disruption of cell–cell attachment mediated by the high affinity ligand–receptor complex, deadhesion of cells from the cell matrix and retraction of cell extensions. Disruption of the ephrinA–EphA cell–cell attachment involves proteolytic cleavage of ephrinA, whereas disruption of the ephrinB–EphB cell–cell attachment involves endocytosis of the entire ephrin–Eph complex [3]. Detachment requires most likely the inactivation of integrins. For instance, activation of both EphA2 and EphB2 results in the inhibition of integrin-mediated cell adhesion [4,5]. Finally, retraction is mediated by the actin cytoskeleton, which is regulated by Rho GTPases [6]. For instance, EphA-mediated cell repulsion requires Rho and its effector ROCK (Rho-associated kinase) [7]. Eph-mediated cell repulsion is linked to Rac and Cdc42, as well as to Rho [3]. Also Ras-like small GTPases are involved in ephrin-Eph signalling and may play a role in the regulation of integrins. In several cell types, both EphA- and EphB-mediated signalling resulted in the down-regulation of Ras-GTP levels [4,8], and for neuronal cells it was shown that down-regulation of Ras is required for the retraction of cell extensions presumably through the inactivation of integrins [8]. For other cell types, it was shown that phosphorylation and inactivation of R-Ras was involved in Eph-mediated inactivation of integrins [5]. Finally, it was reported that ephrinB1 stimulation results in the activation of Rap1 in HAECs (human aortic endothelial cells) [9]. Rap1 is critically involved in the regulation of integrins and strikingly, the activation of Rap1 correlated with increased adhesion, rather than repulsion. Finally, SHEP1, a protein containing an SH2-domain and a domain homologous to guanine exchange factors for Ras-like small GTPases, was found to interact with both the activated EphB2 receptor and R-Ras and Rap1 [10]. However, the biological function of this interaction is currently unclear.

We have demonstrated recently that reverse gradients of EphB receptors and ephrin ligands restrict bidirectional migration of intestinal precursor cells along the crypt–villus axis, indicating that also in colon cells the Eph-ephrin system plays an important role in cell sorting [11]. To study ephrin-Eph signalling in these cells in further detail, we have generated a colon cell line overexpressing the EphB2 receptor. Stimulation of this cell line with ephrinB1 resulted in a rapid retraction of cell extensions followed by detachment. This retraction requires the activation of RhoA and surprisingly the inactivation of Rap1. Indeed, expression of constitutively active Rap1 inhibited ephrinB1-induced cell retraction. Down-regulation of Rap1 is most likely required to inactivate integrins to inhibit integrin-mediated cell adhesion.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Reagents

EphrinB1, laminin and the EphB2 specific antibodies were obtained from R & D Systems (Wiesbaden, Germany). The ROCK-inhibitor Y-27632 and cytochalasin D were obtained from Calbiochem (Bad Soden, Germany). Alexa-568-conjugated phalloidin was obtained from Molecular Probes (Europe BV, Leiden, The Netherlands). The Rap1 specific antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Heidelberg, Germany). RhoA and Ras specific antibodies were obtained from BD Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY, U.S.A.). Polyclonal phospho-p44/42 MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase; Thr202/Tyr204) antibody was from Transduction Laboratories. PY-20 monoclonal antibody was obtained from BD Transduction Laboratories. PVDF membranes and ECL® (enhanced chemiluminescence) were from Amersham Biosciences. G418 (Geneticin) was obtained from Sigma (München, Germany). All cell culture reagents were obtained from Invitrogen.

Cells, plasmids and transfections

Plasmids encoding Rap1V12, RapGAP (where GAP stands for GTPase-activating protein), GFP (green fluorescent protein) and luciferase have been described previously [16]. DLD1 cells stably transfected with a cDNA encoding full-length EphB2 receptor were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen), supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated (30 min at 56 °C) foetal bovine serum and 0.05% glutamine in the presence of penicillin, streptomycin and 500 μg/ml G418. Cells were split every 2–3 days. LS174T cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum and 0.05% glutamine in the presence of penicillin and streptomycin. For transfections, the cells were freshly seeded on laminin-coated (2 μg/cm2) glass coverslips and transfected with the designated cDNAs and either GFP or a luciferase construct driven by a CMV (cytomegalovirus) promoter in the ratio of 10:1. Transfections were performed using Fugene (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Cells were analysed 24 or 48 h after transfection.

Rap1-, RhoA-, Ras- and EphB2-activity determination

The activity of Rap1 was determined as described previously [12]. Briefly, cells were seeded on laminin-coated (2 μg/cm2) 10 cm dishes and grown until they reached a confluency of 60–70%. The cells were then stimulated with 2 μg/ml of aggregated Fc-ephrinB1 for the indicated time points and harvested without a washing step in lysis buffer containing 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1% Nonidet P40, 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 μM leupeptin, 0.1 μM aprotinin and 0.1 μM PMSF. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at maximal speed in an Eppendorf centrifuge for 5 min at 4 °C. The GTP-bound form of Rap1 was isolated using GST–RalGDS-RBD (where GST stands for glutathione S-transferase) as an activation-specific probe and subsequently quantified by Western blotting using anti-Rap1 antibody. To determine the activity of the EphB2 receptor, the receptor was immunoprecipitated from the same lysates that had been used before to determine Rap1 activity and analysed for tyrosine phosphorylation using PY-20 in a Western-blot experiment.

Ras activity was determined using GST–Raf-RBD as an activation-specific probe and was described previously [12]. RhoA activity was determined as described previously [13] using GST–Rhotekin-RBD as an activation-specific probe. Briefly, cells were lysed on ice in RIPA buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM NaF, 1 μg/ml leupeptin and 1 mM PMSF. Lysates were centrifuged for 2 min at maximal speed. Cleared lysates were incubated for 45 min at 4 °C with GST–Rhotekin coupled to glutathione–Sepharose beads to precipitate GTP-bound RhoA. The precipitated complexes were washed with RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% Nonidet P40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 10 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 1 μM leupeptin and 0.1 μM aprotinin) and boiled in SDS sample buffer. The total lysates and precipitates were analysed on a Western blot using antibodies against RhoA.

Contraction and deadhesion assays

To examine the effect of ephrinB1 on cell deadhesion, cells were seeded on laminin-coated 24-well plates and transfected with the indicated DNA constructs together with a luciferase construct driven by a CMV promoter [14] in the ratio of 10:1 and grown in serum-containing medium at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After 24 h, cells were stimulated with 2 μg/ml Fc-ephrinB1 for 1 h and the plates were washed three times with TSM buffer (20 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2 and 2 mM MgCl2) to remove non-adherent cells. Adherent cells were lysed in luciferase lysis buffer (15% glycerol, 25 mM Tris-phosphate, pH 7.8, 1% Triton X-100, 8 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM dithiothreitol) at 4 °C for 30 min, and units of luciferase activity were quantified with the addition of an equal volume of luciferase assay buffer (25 mM Tris-phosphate, pH 7.8, 8 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM ATP and 1 mM luciferin) using a luminometer (Lumat LB9507; Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany). Deadhesion was determined by the reduction in luciferase counts of stimulated wells in comparison with unstimulated wells and differences are expressed as percentages. The experiment was performed three times in triplicates.

For the contraction assays, cells were seeded on laminin-coated glass coverslips and co-transfected with a plasmid encoding GFP in the ratio of 10:1. Cells were grown for 24 h in serum-containing medium before stimulation. After stimulation for 1 h with ephrinB1, the coverslips were washed carefully once with PBS and cells were fixed with 4% (v/v) formaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature (22 °C). Cells were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 min and then filamentous actin was stained with Alexa-568-conjugated phalloidin for 1 h. Coverslips were then mounted on glass slides using ImmunoMount (ThermoShandon, Pittsburgh, PA, U.S.A.). Transfected cells (identified by fluorescence of co-transfected GFP) were analysed for morphological changes and 50 cells were counted for each transfection. Assays were performed three times in triplicates.

RESULTS

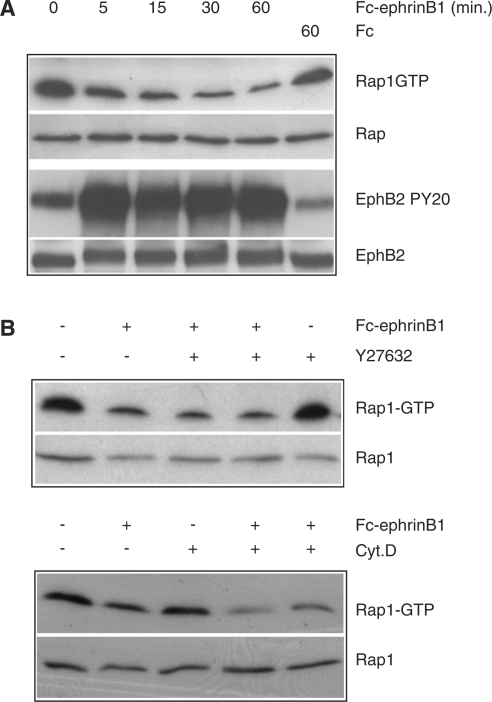

To investigate which signalling pathways may be involved in EphB2-mediated cell sorting in colon cells, we generated DLD1 colon carcinoma cells stably expressing the EphB2 receptor. After stimulation with soluble ephrinB1, this cell line undergoes significant morphological changes. Within 5–10 min of ephrinB1 stimulation, cells start to retract their cell extensions (Figure 1A) and reorganize their actin cytoskeleton (results not shown). This process culminates 30 min after ligand addition with the acquisition of a round and retracted morphology, strikingly different from the original spread morphology. We first investigated the involvement of Rho in this process. As shown in Figure 1(B), Rho is rapidly activated after ephrinB1 stimulation of the EphB2- expressing DLD-1 cells (Figure 1B). Importantly, addition of 10 μM Y-27632, a specific inhibitor of the Rho effector ROCK, inhibited ephrinB1-induced contraction (results not shown), confirming the critical role of Rho-ROCK signalling in ephrin-induced cell contraction [7]. In keeping with the notion that downregulation of the Ras-MAPK pathway has been shown to be required for ephrin-induced retraction of cell extensions in neuronal cells stably expressing the EphB2 receptor, we investigated the effect of ephrin stimulation on the Ras-ERK (where ERK stands for extracellular-signal-regulated kinase) pathway in our cells. Interestingly, we observed an increase in Ras-GTP and phospho-ERK levels (Figure 1C) after ephrinB1 stimulation. From these results, we conclude that EphB2 may use a different pathway for cell retraction in colon cells compared with neuronal cells. Finally, we measured the activity of Rap1 and observed that ephrinB1 stimulation resulted in the down-regulation of Rap1 (Figure 2A, upper panel). This down-regulation rapidly follows activation of the EphB2 receptor (Figure 2A, lower panel), suggesting a direct response of EphB2 receptor activation. To exclude that the down-regulation of Rap1 is a consequence of cell retraction, we treated the cells with the ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 and with the actin polymerization inhibitor cytochalasin D, which both inhibit ephrinB1-induced contraction. However, we found that Rap1-GTP loading was down-regulated to the same extent as in non-treated ephrinB1 stimulated cells (Figure 2B). Thus, down-regulation of Rap1 after EphB2 stimulation occurred independently of cell contraction.

(A) DLD1 cells were stimulated with 2 μg/ml of Fc-ephrinB1 and visualized by phalloidin staining before and after 30 min of Fc-ephrinB1 stimulation. (B) DLD1 cells were stimulated for the indicated time points with Fc-ephrinB1, and the activity of RhoA was determined using GST–Rhotekin-RBD as an activation-specific probe and subsequently quantified by Western blotting using anti-Rho antibody. To ensure that equal amounts of protein was analysed, Rho levels were determined in whole cell lysates. This result is a representative of three independent experiments with equal results. (C) DLD1 cells were stimulated for the indicated time points with Fc-ephrinB1, and the activity of Ras was determined using GST–Raf-RBD as an activation-specific probe and subsequently quantified by Western blotting using an anti-Ras antibody. Equal amounts of cell lysates were analysed for MAPK activation using a phospho-specific MAPK antibody.

(A) DLD1 cells were stimulated for the indicated time points with Fc-ephrinB1 (or with Fc alone) and the activity of Rap1 was determined using RalGDS-RBD as an activation-specific probe and subsequently quantified by Western blotting using anti-Rap1 antibody. To ensure that equal amounts of protein were analysed, Rap1 levels were determined in whole cell lysates. As a control for the activation of the EphB2 receptor, the receptor was immunoprecipitated from the same lysates that had been used before to determine Rap1 activity and analysed for tyrosine phosphorylation in a Western-blot experiment using a PY-20 monoclonal antibody. This result is representative of three independent experiments with similar results. (B) To test whether the observed down-regulation of Rap1 was an indirect effect, cells were stimulated for 30 min with Fc-ephrinB1 in the presence or absence of 10 μM Y-27632 (upper panel) or 5 μM cytochalasin D (lower panel) and the activity of Rap1 was determined as described in the text. To ensure that equal amounts of protein were analysed, Rap1 levels were determined in whole cell lysates. Pretreatment of cells with Y-27632 and cytochalasin D was for 1 h.

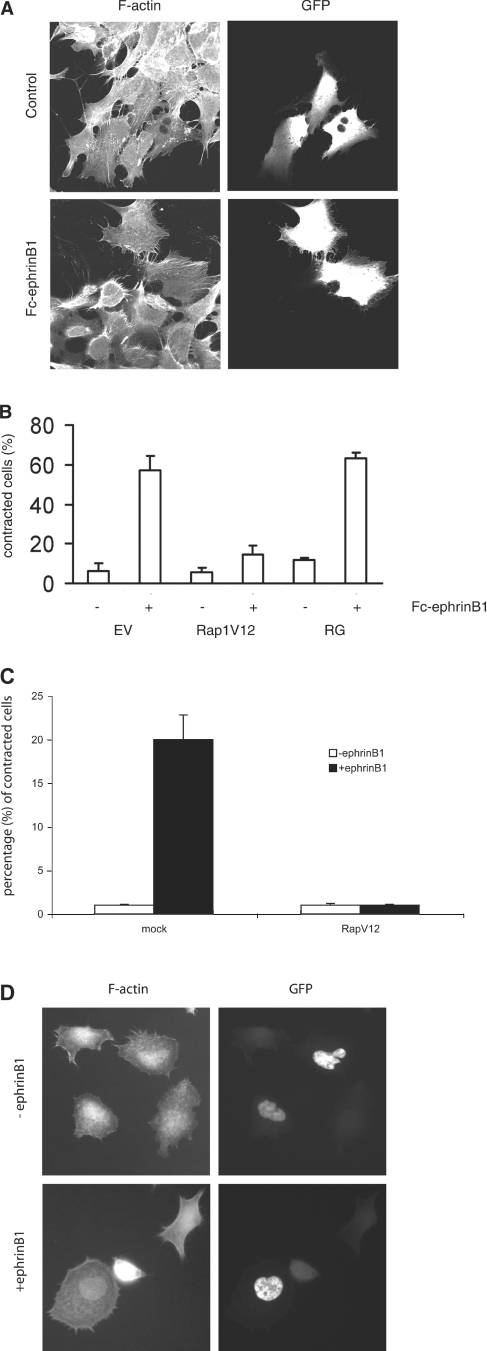

We next investigated whether down-regulation of Rap1 GTP levels was necessary for any of the morphological changes observed in DLD1 cells on stimulation of EphB2 receptor activity. For this, EphB2-expressing DLD1 cells were transfected with a constitutively active variant of Rap1 (Rap1V12) together with GFP. Transfected cells were stimulated with ephrinB1 and analysed under a fluorescence microscope for their morphology. As shown in Figure 3(A), cells transfected with Rap1V12 retained their spread morphology despite EphB2 activation, whereas untransfected cells had completely lost their extensions and displayed a rounded, retracted morphology on addition of ephrinB1. To quantify the effect of Rap1V12 on cell rounding, cells were transfected either with the empty vector, Rap1V12 or RapGAP, in combination with GFP, followed by ephrinB1 stimulation. Overexpression of Rap1V12 reduced the number of contracted cells five times, i.e. 12% of contracted cells compared with 60% in cells transfected with the empty vector. Overexpression of RapGAP did not affect the number of contracted cells after ephrinB1 stimulation when compared with vector-transfected cells. Significantly, inhibition of Rap by expression of RapGAP failed to induce cell contraction in the absence of ephrinB1. From these results, we conclude that down-regulation of Rap1 activity is required, but it is not sufficient for EphB2-mediated contraction in DLD1 cells. In addition, in LS174T cells, which express the EphB2 receptor at an endogenous level, transfection of Rap1V12 also blocked the ephrinB1-induced retraction (Figures 3C and and33D).

(A) DLD1 cells were co-transfected with the indicated cDNAs and GFP and stimulated 24 h later with Fc-ephrinB1 for 1 h. Cells were washed once with PBS, fixed, permeabilized and subsequently visualized under a fluorescence microscope. A representative section of Rap1V12-transfected cells is shown. The non-transfected, surrounding cells had completely rounded up the Rap1V12-transfected cells, as indicated by fluorescence of GFP, attached and spread. (B) Quantification of (A). Fluorescent cells were analysed for their morphology and categorized into round or spread cells. In each slide, 50 cells were counted. Experiments were performed in triplicate and representative data are shown. Error bars represent S.D. The experiments were repeated at least four times with similar results. EV, empty vector and RG, RapGAP. (C) LS174T cells were seeded at low density on laminin-coated plates and transfected with Rap1V12 in combination with a GFP marker in the ratio 10:1. Two days after transfection, the cells were stimulated with the ephrinB1 ligand for 5 min. A total of 100 cells of both the transfected and untransfected populations were counted and analysed for their retracted phenotype by phalloidin staining for immunofluorescence. (D) Representative picture of (C).

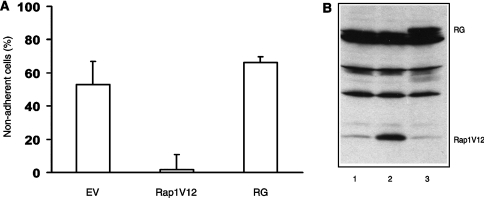

One of the main functions of Rap1 is the regulation of integrin activity, and thus Rap1-GTP down-regulation may result in a decreased integrin-mediated cell adhesion. We therefore tested whether overexpression of Rap1V12 could inhibit the loss of integrin-mediated cell adhesion induced by ephrinB1 stimulation. Cells were seeded on laminin-coated plates and transfected with either empty vector, Rap1V12 or RapGAP. As shown in Figure 4(A), after stimulation with ephrinB1 only approx. 50% of the control cell remained attached, whereas virtually all Rap1V12 expressing cells remained adherent. Overexpression of RapGAP did not affect the amount of non-adherent cells after ephrinB1 stimulation when compared with empty vector-transfected cells. This result suggests that one of the Rap effects in ephrin-induced cell retraction is Rap1-mediated inactivation of integrins.

(A) DLD1 cells were co-transfected with the indicated cDNAs and a CMV-luciferase plasmid. Cells were stimulated 24 h after transfection, for 1 h with 2 μg/ml of Fc-ephrinB1, washed three times with PBS and deadhesion of the cells was quantified. The percentage of adherent cells was plotted relative to unstimulated cells for each condition. Experiments were performed in triplicate and representative data are shown. Error bars represent S.D. The experiments were repeated at least three times with identical results. (B) Expression blot of empty vector (lane 1), Rap1V12 (lane 2) and RapGAP (lane 3) transfected cells.

DISCUSSION

We showed previously that the Eph-ephrin signalling pathway has a role in the migration of intestinal precursor cells along the crypt–villus axis [11]. We now report that stimulation of colon cells overexpressing the EphB2 receptor with ephrinB1, results in a rapid retraction of cell extensions and the appearance of a rounded phenotype. Further analysis revealed that the small GTPase Rho plays an essential role in this process. EphrinB1 stimulation results in the activation of Rho, and inhibition of the Rho effector ROCK inhibits the morphological effect of ephrinB1 stimulation. This is consistent with previous results showing the requirement of Rho in cell contraction [7]. Interestingly, ephrinB1 stimulation results in the down-regulation of the Ras-like small GTPase Rap1. Rap1 was first identified as a protein capable of reverting Ras transformation, and more recent results showed that Rap1 is a critical mediator in the control of integrin activation [15–17]. The mechanism by which Rap1 regulates integrins is currently only partly understood and may include the binding of Rap1 to RAPL (regulator of cell adhesion and polarization enriched in lymphoid tissues), a protein that also interacts with integrins [18]. The critical role of Rap1 in ephrinB1-induced cell retraction, at least for our model colon cell system, was shown by the introduction of a constitutively active RapV12 construct. Expression of RapV12 completely abolished ephrinB1-induced cell retraction. However, inactivation of Rap1 is not sufficient for the retraction of cell extensions since expression of RapGAP, which inhibits Rap1, did not induce cell retraction. From these results, we conclude that Rap1 is required but not sufficient for the induction of cell retraction.

Previously, Rap1 has been implicated in ephrin-Eph signalling. For HAE cells, it was shown that ephrinB1 stimulation results in the activation of Rap1. However, in these cells, ephrinB1 promotes the spreading rather than contraction and detachment of the cells [9]. In neuroepithelial cells, it was shown that Rap1 but not Ras is activated after ephrinA stimulation [19].

The mechanism by which EphB2 down-regulates Rap1 is currently unclear, but it could be mediated by SHEP1. This protein directly binds to tyrosine-phosphorylated EphB2 through its SH2 domain. In addition, SHEP1 contains a region homologous to guanine exchange factors for Ras-like small GTPases. Significantly, SHEP1 can interact with Rap1, but does not seem to catalyse nucleotide exchange. As suggested by Dodelet et al. [10], SHEP1 may be a negative regulator of Rap1 by preventing other GEFs (guanine nucleotide-exchange factors) from activating Rap1. Alternatively, EphB2 may activate Rap1-specific GAPs or modulate GEFs. Further studies are required to solve this issue. From our results, we propose a model by which the contraction of cells occurs through a two-step mechanism: loss of adhesion that is mediated by the down-regulation of Rap1 GTP levels followed by the contraction of the cell body, mediated by the activation of Rho. Our results suggest that the down-regulation of Rap1 might be an essential prerequisite for the Rho-mediated cell contraction, because most of the cells that overexpress Rap1V12 do not show obvious actin rearrangements or morphological changes on EphB2-receptor activation.

One of the remaining questions is the observation that, in neuronal cells ephrin-induced retraction of cell extensions is mediated by a down-regulation of Ras-GTP, whereas in colon cells Ras-GTP levels are up-regulated. In contrast, Rap1 is down-regulated in colon cells. However, it should be noted that a role of Rap1 in ephrin-induced neuronal cell retraction has not been studied yet.

Considering the critical role of Rap1 in the regulation of inside-out signalling to integrins, it is plausible that one of the effects of Rap1 down-regulation is the inhibition of integrin-mediated cell adhesion. Recently, it was shown that Rap1 also regulates adhesion to laminin and that this is mediated by α3β1, but not α6β4 integrins [20]. Indeed, when we measure cell adhesion to laminin, which is mediated by, among others, integrin α3β1, we observe a significant decrease in adhesion after Eph stimulation, which is inhibited by the introduction of a constitutive active version of Rap1. These results are in keeping with the notion that ephrin-Eph signalling regulates integrins. For instance, in PC-3, it has been shown that activation of EphA2 inhibits integrin-mediated adhesion and causes dephosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase in a ligand-dependent manner [4]. Furthermore, it was shown that activation of EphA3 induces rounding and deadhesion in 293T and melanoma cells [21,22]. Also, EphB2 signalling has been shown to regulate integrin activity through phosphorylation and inactivation of R-Ras [5]. Finally, signalling by ephrinB1 and Eph kinases in platelets promotes Rap1 activation and platelet adhesion and aggregation [22].

It should be noted that several Eph receptors and ephrins are overexpressed in a variety of tumours. This up-regulation may contribute to tumour progression and invasiveness by modulating the adhesive properties of the cells [21,23]. Our finding that Rap1 plays a critical role in Eph-induced cell retraction indicates a further function for this, once so elusive, small GTPase.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of our laboratories for support and stimulating discussions. J. A. R. was supported by a grant from the Centre for Biomedical Genetics. D. T. B. and L. S. P. were supported by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF Kankerbestrijding, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). E. B. was supported by a Marie Curie Fellowship.

References

Articles from Biochemical Journal are provided here courtesy of The Biochemical Society

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1042/bj20050048

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc1175124?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Article citations

Exploring the key genes and pathways of osteosarcoma with pulmonary metastasis using a gene expression microarray.

Mol Med Rep, 16(5):7423-7431, 21 Sep 2017

Cited by: 19 articles | PMID: 28944885 | PMCID: PMC5865874

Myosin 1b functions as an effector of EphB signaling to control cell repulsion.

J Cell Biol, 210(2):347-361, 01 Jul 2015

Cited by: 20 articles | PMID: 26195670 | PMCID: PMC4508888

Rap1 signaling in endothelial barrier control.

Cell Adh Migr, 8(2):100-107, 01 Mar 2014

Cited by: 38 articles | PMID: 24714377 | PMCID: PMC4049856

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Small GTPases of the Ras superfamily regulate intestinal epithelial homeostasis and barrier function via common and unique mechanisms.

Tissue Barriers, 1(5):e26938, 25 Oct 2013

Cited by: 50 articles | PMID: 24868497 | PMCID: PMC3942330

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Eph receptor signaling and ephrins.

Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 5(9):a009159, 01 Sep 2013

Cited by: 225 articles | PMID: 24003208 | PMCID: PMC3753714

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (12) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Downregulation of the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by the EphB2 receptor tyrosine kinase is required for ephrin-induced neurite retraction.

Mol Cell Biol, 21(21):7429-7441, 01 Nov 2001

Cited by: 117 articles | PMID: 11585923 | PMCID: PMC99915

Signaling by ephrinB1 and Eph kinases in platelets promotes Rap1 activation, platelet adhesion, and aggregation via effector pathways that do not require phosphorylation of ephrinB1.

Blood, 103(4):1348-1355, 23 Oct 2003

Cited by: 44 articles | PMID: 14576067

EphB-EphrinB interaction controls odontogenic/osteogenic differentiation with calcium hydroxide.

J Endod, 39(10):1256-1260, 27 Aug 2013

Cited by: 10 articles | PMID: 24041387

Regulation of lymphocyte adhesion and migration by the small GTPase Rap1 and its effector molecule, RAPL.

Immunol Lett, 93(1):1-5, 01 Apr 2004

Cited by: 61 articles | PMID: 15134891

Review

†,3

†,3