Abstract

Free full text

RhoGDI: multiple functions in the regulation of Rho family GTPase activities

Abstract

RhoGDI (Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor) was identified as a down-regulator of Rho family GTPases typified by its ability to prevent nucleotide exchange and membrane association. Structural studies on GTPase–RhoGDI complexes, in combination with biochemical and cell biological results, have provided insight as to how RhoGDI exerts its effects on nucleotide binding, the membrane association–dissociation cycling of the GTPase and how these activities are controlled. Despite the initial negative roles attributed to RhoGDI, recent evidence has come to suggest that it may also act as a positive regulator necessary for the correct targeting and regulation of Rho activities by conferring cues for spatial restriction, guidance and availability to effectors. These potential functions are discussed in the context of RhoGDI-associated multimolecular complexes, the newly emerged shuttling capability and the importance of the particular membrane microenvironment that represents the site of action for GTPases. All these results point to a wider role for RhoGDI than initially perceived, making it a binding partner that can tightly control Rho GTPases, but which also allows them to reach their full spectrum of activities.

INTRODUCTION: RhoGTPases AND LEVELS OF REGULATION

Rho family GTPases play important roles in a variety of cellular functions. RhoA, Rac1 and Cdc42, the defining members of this family, were initially linked to changes in the filamentous actin system involving the formation of stress fibres, membrane ruffles/lamellipodia and filopodia respectively [1]. Now it is widely accepted that their roles extend beyond these initial observations and cover many aspects of cellular regulation including morphology and migration, gene transcription, cell cycle progression and cytokinesis, phagocytosis and vesicular traffic, as well as regulation of a range of enzymatic functions, e.g. NADPH oxidase [2].

Typically, Rho family GTPases act as molecular switches cycling between inactive (GDP-bound) and active (GTP-bound) forms. Post-translational modification with a C-terminal prenyl moiety allows them to associate with membranes where they can interact with, and activate, their effectors [3]. Because of their crucial roles, several levels of regulation tightly control their activation state and accessibility. Activation through exchange of GDP for GTP is catalysed by GEFs (guanine nucleotide-exchange factors) [4] and promotes downstream signalling; GAPs (GTPase-activating proteins) [5] accelerate the intrinsic GTPase activity to inactivate the protein and terminate the signal.

A third level of regulation also exists: RhoGDIs (Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitors). These function by extracting Rho family GTPases from membranes and solubilizing them in the cytosol. Moreover, both in vitro and in vivo they interact only with prenylated Rho proteins. They also inhibit nucleotide exchange and GTP hydrolysing activities on Rho proteins by interacting with their switch regions (see below) and probably restricting accessibility to GEFs and GAPs.

RhoGDI constitutes a family with three mammalian members: RhoGDIα, the ubiquitously expressed archetypal member of the family; Ly/D4-GDI or RhoGDIβ, which has haematopoietic tissue-specific expression, particularly in B- and T-lymphocytes; and RhoGDI-3 or -γ, which is membrane-anchored through an amphipathic helix and is preferentially expressed in brain, pancreas, lung, kidney and testis [6,7]. RhoGDIs have a long evolutionary history and are present in yeast [8], Caenorhabditis elegans [9], Dictyostelium [10,11], Arabidopsis [12] and Drosophila melanogaster. RhoGDI, along with PDEδ (δ subunit of the retinal rod cGMP phosphodiesterase) and the UNC-119/RG4 group of proteins from mammals, C. elegans, D. melanogaster and zebrafish (Danio rerio) may constitute a novel family of evolutionarily conserved proteins with common features of primary and tertiary structure, interacting with prenylated proteins to regulate their membrane association [13]. Binding selectivity of RhoGDIs to Rho GTPases remains a controversial issue with discrepancies existing between the potential binding partners in vitro and in vivo [7]. Thus, RhoGDIα can bind to RhoA, RhoB (but not to palmitoylated RhoB; [14]), Rac1, Rac2 and Cdc42 both in vitro and in vivo, but, whereas RhoGDIβ may bind several of these GTPases in vitro (albeit with lower affinities; e.g. [15]), not all of these complexes have been detected in vivo (e.g. [16]). For murine RhoGDIγ the spectrum of binding partners is limited to RhoB and RhoG [17], whereas the human equivalent binds RhoA, RhoB and Cdc42, but not Rac1 or Rac2 [18].

RhoGDI KNOCKOUTS

Disruption of the RhoGDIα gene (ARHGDIA) in mice results in age-dependent degeneration of kidney functions leading to renal failure and death, with additional defects in male reproductive systems and the post-implantation development of null embryos in null female mice [19]. Neither RhoGDIβ, with its haematopoietic distribution, nor RhoGDIγ can compensate for the loss of RhoGDIα. The subcellular localization of RhoGDIγ protein to Golgi membranes [20] and its reduced spectrum of binding partners may explain its inability to complement RhoGDIα, even though it is expressed in kidney and testis [17].

Knocking out RhoGDIβ gene (ARHGDIB) expression does not have such profound effects, indicating redundancy of function with RhoGDIα, perhaps due to its widespread expression. Embryonic stem cells deficient in ARHGDIB express RhoGDIα at normal levels and develop normally into progenitor and erythromyeloid populations, while macrophages have no apparent defects in phagocytosis, although superoxide generation is slightly impaired [21]. In mice with targeted disruption of ARHGDIB [22], embryonic development and immune system maturation are intact, the only phenotypic changes being some aspects of lymphocyte expansion and survival in vitro. A double knockout might be more useful in revealing the roles of these molecules in the immune system.

GDI1 deficiency in Dictyostelium leads to defects in cytokinesis [10,11], pinocytosis and the contractile vacuole system, with these effects being partially restored by overexpressing constitutively active forms of Rho GTPases [11]. Although actin polymerization does seem to be affected, chemotaxis and phagocytosis rates remain unaltered [11]. In yeast, disruption of RhoGDI expression yields no apparent phenotype, and Rho proteins maintain a cytosolic localization [23].

Overexpression of RhoA in mammalian cells to levels in excess of RhoGDIα still results in a cytosolic distribution, implying that proteins with functions similar to RhoGDI might also exist [14]. Indeed, GDI activities towards RhoA have been reported for p120 catenin [24], and ICAP-1 (integrin cytoplasmic domain-associated protein 1) performs similar functions for both Rac1 and Cdc42 [25]. Therefore, despite the presence of complementary and/or compensatory molecules, RhoGDIα is indispensable for normal kidney and reproductive organ function.

RhoGDI STRUCTURE AND CORRELATION WITH FUNCTION

RhoGDIα comprises two structurally distinct regions: an N-terminal flexible domain (residues 1–69) and a C-terminal folded domain (residues 70–204). Both domains contribute significantly to the binding and consequently the inhibitory actions of the molecule through protein–protein and protein–lipid interactions (see below and also Figures 1 and and22).

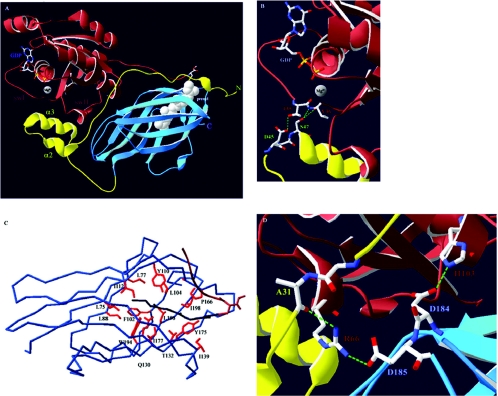

(A) Overview of the Cdc42–RhoGDIα complex. Cdc42 is shown in brown and its isoprenyl moiety in white space-fill (prenyl). The nucleotide (GDP) and the Mg2+ ion, as well as the switch I and II regions (swI and swII respectively), of Cdc42 are also indicated. The N-terminal domain of RhoGDIα is in yellow with the helix–loop–helix motif indicated through helices α2 and α3. The C-terminal immunoglobulin-like motif is in blue. (B) Nucleotide binding occurs through co-ordination of the Mg2+ ion by the main chain carbonyl group of Thr35(Cdc42). RhoGDIα stabilizes the GDP-bound form and prevents nucleotide dissociation through hydrogen bonds (dashed green lines) occurring between the carboxy oxygen of Asp45(RhoGDI) and the hydroxy group of Thr35(Cdc42) and between the hydroxy group of Ser47(RhoGDI) and the main chain amide and carbonyl groups of Val36(Cdc42). (C) Overview of the hydrophobic pocket of RhoGDIα. Shown is the α–carbon atom trace. Conserved hydrophobic amino acids (red) that form favourable van der Waals contacts along the length of the geranylgeranyl group (dark blue) line the pocket. Also indicated is the C-terminal hypervariable region of Cdc42 (brown). (D) Arg66(Cdc42) constitutes an important residue for the interaction with RhoGDIα as it can interact with amino acids from both the N- and C-terminal domains of RhoGDIα. The hydrogen bonds between the side chain of Arg66(Cdc42) and the main chain carbonyl group of Ala31(RhoGDI) and the side chain of Asp185(RhoGDI) are indicated. Also shown is the highly conserved interaction between Asp184(RhoGDI) and His103(Cdc42). Mutation of either of these residues on GTPases results in RhoGDI-binding deficiency [58–60,62,66].

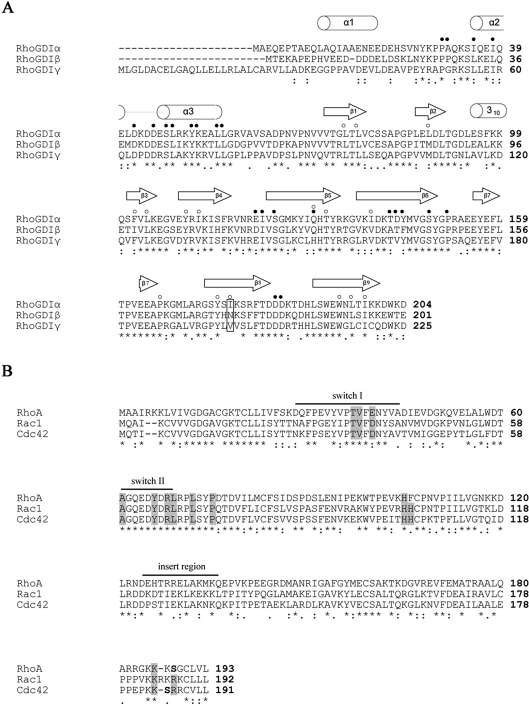

*, identical residues; :, conservation of homologous residues;·, strong conservation of groups. (A) Elements of secondary structure are indicated above the sequences according to Hoffman et al. [30], except for helix α1, assigned according to Golovanov et al. [28]. ● indicates residues important for the protein–protein interface, as determined from the three crystal structures [30–32]. ○ indicates residues lining the hydrophobic pocket as determined by Hoffman et al. [30]. The single amino acid difference between RhoGDIα and RhoGDIβ responsible for their difference in affinity towards Cdc42 [15] is boxed. (B) Residues of Rho GTPases contributing to the interactions with RhoGDIs as determined by the three crystal structures are found mostly in and proximal to the switch regions and the C-terminal hypervariable sequences and are boxed in grey. The insert region is also indicated. The serine residues on RhoA (Ser188) and Cdc42 (Ser185), shown in bold, are substrates for PKA and their phosphorylation contributes to enhanced association with RhoGDIα [36,37].

The N-terminal domain

Initial NMR studies indicated that the N-terminal domain of the free form of RhoGDIα is flexible in solution [26,27] with residues 9–20 and 36–58 forming transient helices [28]. Co-crystallization studies of RhoGDIα with GDP-bound RhoA [29], Cdc42 [30] and Rac1 [31], as well as that of RhoGDIβ with Rac2(GDP) [32], demonstrated that this domain becomes stable upon complex formation. Residues 34–57 adopt a well-ordered helix–loop–helix motif held through a series of hydrophobic interactions between the aliphatic portions of their amino acid side chains. Residues 5–25 form a poorly ordered extended loop in the complex, with a small helix at positions 10–15 in the Cdc42–RhoGDI complex [30] that is not visible in the other structures. The N-terminal part of the molecule comprises the ‘regulatory arm’ and is responsible for inhibition of both GDP dissociation and GTPase functions. Indeed, a number of residues in this domain, in particular those of the helix–loop–helix motif, form direct contacts with key amino acids in the switch regions of the GTPases that may be able to stabilize each nucleotide-bound state.

Highly conserved interactions in the switch I region of the GTPases are contributed to by Thr35 (Cdc42 numbering) with its adjacent Val36 forming hydrogen bonds with Asp45 and Ser47 respectively on RhoGDIα (Figure 1B). This threonine residue is conserved in every GTP-binding protein and is important for the co-ordination of Mg2+ that stabilizes the nucleotide. Interestingly, Thr35 is required for Dbl family GEF-catalysed nucleotide exchange [33], and RhoGDI could inhibit by competing with GEFs for this key residue. Extensive contacts, both polar and hydrophobic, are also formed between residues of the GTPase switch II region and the N-terminus of RhoGDI. These could affect Gln61, a residue important for GTP hydrolytic activity, which is correspondingly inhibited [30].

Deletion of the first 7 or 14 amino acids caused partial loss of GTPase inhibitory function of RhoGDIα on RhoA and Rac1, whereas removal of the first 20 or 30 amino acids resulted in complete loss without affecting inhibition of GDP dissociation [28]. Furthermore, the Δ20 mutant was able to extract the GDP-bound, but not the GTP-bound, form of Rac1 from biological membranes, unlike the wild-type molecule [28]. This region may not affect the binding to the GDP-bound form of the GTPase, but provides an additional surface for association with the GTP-bound forms of RhoA and Rac1. Elucidation of the structure of RhoGDI in complex with GTP–Rho proteins may reveal the function of this region. The inherent flexibility of the N-terminus of RhoGDI in the free state allows it to overcome unfavourable energetic transitions occurring upon binding, facilitating an association with both nucleotide states of the GTPases [28,34].

The C-terminal domain

The C-terminal part of RhoGDI adopts an immunoglobulin-like fold comprising nine β-strands in two antiparallel sheets and a two-turn 310 helix [26,27,29–31]. The two sheets create a hydrophobic cavity that can accommodate the isoprenyl group of the GTPase. Its base and inner walls are lined by conserved hydrophobic amino acid residues (Figure 1C), while in and near the cavity are regions of negative electrostatic potential that can interact with the hypervariable regions of the GTPases immediately upstream of the isoprenylated cysteine. Although all the amino acids lining the hydrophobic pocket are highly conserved in all three mammalian RhoGDIs, Ile177 is substituted by an asparagine in RhoGDIβ, resulting in significantly lower affinity for Cdc42 [15].

An important aspect of the GTPase–RhoGDI complex is the role of Arg66. By forming hydrogen bonds, and favourable hydrophobic interactions with residues from both the N- and the C-terminus of RhoGDI, it bridges these two domains and stabilizes the flexible N-terminal part against the more stable C-terminus (Figure 1D). Overall, however, the lack of extensive interactions of the C-terminus of RhoGDI with the switch regions of Rho GTPases may explain the inability of this part of the molecule to exhibit GDI activities [26,27].

RhoGDI may therefore have several distinct sites for interaction with Rho family GTPases, each one contributing to the binding and inhibitory activities. The N-terminal domain, by binding to the switch regions of the GTPases, affects the GDP–GTP cycling, whereas the C-terminal domain accommodates the isoprenyl moiety of the GTPase in its hydrophobic pocket, regulating cytosol/membrane partitioning. However, both domains are required for full functionality and contribute equally to the binding energy [34].

REGULATION OF RhoGDI

Complex formation and membrane extraction: mechanisms and regulation

Both X-ray crystallography and NMR studies have provided insight as to how RhoGDI binds Rho GTPases. On the basis of structural results and also kinetic studies [35], a two-step mechanism for the release of Cdc42 from membranes has been proposed [30]. In the first fast step the N-terminal domain of RhoGDI binds to the switch regions of Cdc42. This positions the mouth of the hydrophobic pocket against the membrane surface, allowing binding to the hypervariable region of the GTPase and insertion of the prenyl group. The second rate-limiting step corresponds to isomerization of the geranylgeranyl moiety and insertion into the hydrophobic pocket, resulting in release from the membrane.

Mechanisms regulating the formation of stable, cytosolic Rho–RhoGDI complexes remain largely unknown, although phosphorylation may play a major role in both membrane extraction and the stability of the cytosolic complex. PKA (protein kinase A) phosphorylated GTP–RhoA on Ser188, resulting in its release from lymphocyte membranes, probably through an enhanced association with RhoGDIα [36]. Indeed, PKA-mediated phosphorylation of RhoA and Cdc42 on Ser188 and Ser185 respectively increased their interactions with RhoGDIα in vitro [37]. Rac1 lacks a similar phosphorylation site and therefore its interaction with RhoGDI is not regulated by PKA. Furthermore, RhoA-dependent actin reorganization events could be antagonized by a RhoA S188E phosphomimetic mutant but not by the S188A mutant [38], pointing to the role of phosphorylation-dependent sequestration by RhoGDI as a means of terminating Rho-mediated signals.

Phosphorylation of Cdc42 on Tyr64 by the non-receptor tyrosine kinase Src can enhance the association between Cdc42 and RhoGDIα [39]. Acquisition of negative charge on this tyrosine residue might stabilize its interactions with Lys43 and Lys52 of RhoGDIα, which lie proximally in the three-dimensional structure [30,39]. Furthermore, RhoGDIα isolated from neutrophil cytosol, in complex with RhoA, is phosphorylated, although the site(s) and the kinase(s) involved have not been identified [40]. Phosphatase treatment of the complex resulted in its dissociation, whereas a recent analysis of phosphoprotein alterations in lymphoid cells expressing the BCR/ABL oncoprotein showed that RhoGDIα was hypophosphorylated, coinciding with enhanced RhoA activation levels [41]. Phosphorylation of RhoGDIα may therefore promote stable complexes with RhoA, but whether this represents a general regulatory mechanism of membrane extraction or stable complex formation awaits further investigation.

Mechanisms of dissociation: phosphorylation

Phosphorylation might also be a mechanism of release of GTPases from RhoGDI. Indeed, PKCα (protein kinase C)-dependent activation of RhoA in endothelial cells coincided with phosphorylation of RhoGDIα, whereas in vitro kinase assays indicated that RhoGDIα might be a substrate for this kinase [42]. Likewise, Rac1 activation and subsequent lamellipodia formation appears to involve phosphorylation of RhoGDIα by a calcium-dependent PKC isoform, such as PKCα [43]. It is therefore likely that PKCα phosphorylates RhoGDIα, whether in complex with RhoA or Rac1, and that this results in their activation through an as yet unknown mechanism.

RhoGDIα can be phosphorylated on two sites, Ser101 and Ser174, by PAK (p21-activated kinase) [44] leading to selective activation of Rac1, but not RhoA or Cdc42, both in vitro and in vivo. Crystallographic studies showed that these two serine residues are positioned close to each other and are proximal to the prenyl group of the GTPase [30,31]. Repulsive forces between the negatively charged phosphate groups may induce conformational changes in the prenyl-binding pocket, which in combination with the differences in sequence at the C-termini of the GTPases confer selectivity of release to Rac1 but not RhoA or Cdc42.

Mechanisms of dissociation: protein displacement factors

Protein–protein interactions are another mechanism for release of Rho proteins from complexes with RhoGDI. The ERM (ezrin/radixin/moesin) family of proteins are involved in cortical actin reorganization events [45]. In vitro, the FERM (band 4.1/ERM) domains of proteins are able to bind to RhoGDIα and displace it from all three GTPases, RhoA, Rac1 and Cdc42 [46]. However, microinjection of the radixin FERM domain in serum-starved Swiss 3T3 cells resulted in formation of stress fibres, but not filopodia or lamellipodia, implying the selective activation of RhoA, but not Cdc42 or Rac1 [46]. In vivo complexes between ERM and RhoGDI have been described in the case of the CD44–moesin membrane complex [47] and the CD43–ezrin complex in T-cells [48], which might perform distinct and more complex functions. In CD44–moesin complexes, the ERM protein localized and activated the GTPase (RhoA) at specific sites through its interaction with RhoGDIα [47]. In contrast, the CD43–ezrin complex may redirect RhoGDIα away from the site of action of the GTPase (the immunological synapse), presumably so as to prevent it from extracting the GTPase (probably Cdc42) once it has been released [48]. Interestingly, a C-terminally truncated mutant of RhoGDIβ (residues 166–201) was found to be constitutively membrane-anchored through ERM proteins, and associated with GTP-bound Rac1, contributing to enhanced metastatic potential [49]. However, that study [49] suggests the formation of a stable membrane-associated ternary complex, rather than the release of Rac1 at specific ERM-organized sites.

The neurotrophin receptor p75NTR can mediate the inhibitory effects of myelin-based growth inhibitors on axon outgrowth through activation of RhoA. The mechanism involves a direct interaction between the cytoplasmic domain of p75NTR and RhoGDIα, resulting in activation of RhoA [50]. In agreement with this, a cell-permeant synthetic peptide, specifically associating with the RhoGDI-binding site on p75NTR, efficiently blocked neuronal RhoA activation and reversed axon retraction [50]. None of these studies identified the binding site on RhoGDI, which could help to reveal the release mechanism. However, ERM proteins have sequences similar to the D65RLRP69 sequence in Rac1/Cdc42 shown to be important for interactions of GTPases with RhoGDI [51]. Similar to GTPases, therefore, ERM binding might be mediated by multiple regions of RhoGDI. Etk (a non-receptor tyrosine kinase) also releases RhoA from RhoGDIα, but does so by competing for binding sites on the GTPase, rather than on RhoGDIα [52]. Furthermore, this seems to be kinase-independent, as the pleckstrin-homology domain of Etk was sufficient to induce dissociation.

Mechanisms of dissociation: the role of phospholipids

Additional specificity of displacement mechanisms can be elicited by a localized increase in the concentration of specific phospholipids. The function of many Rho family GTPases requires phospholipid microenvironments, capable of concentrating signalling molecules and altering their activities and functions [53]. Effects of phospholipids, for example PtdIns(4,5)P2, can include localizing binding partners activating GEFs and kinases or a direct action on the Rho–RhoGDI complex. Cell-free assays demonstrated that arachidonic acid, phosphatidic acid and PtdIns(4,5)P2 could disrupt the cytosolic Rac1–RhoGDIα complex [54]. Furthermore, phosphatidic acid and some inositol phospholipids, but not fatty acids, were capable of inhibiting GDI functions in vitro at physiologically relevant concentrations. However, much higher concentrations were required to disrupt the purified complex, indicating that lipids do not act analogously to displacement factors such as ERM proteins and p75NTR. A second study also stressed the fact that phosphoinositides do not dissociate the complex, but partially disrupt it [55]. Moreover, pre-incubation with phosphoinositides favoured translocation of RhoA(GTP)–RhoGDIα to purified neutrophil membranes, interacting with specific (but as yet unknown) proteins [55]. Possibly, an elevated phosphoinositide concentration facilitates docking of the complex to membranes, with partial dissociation allowing competition with GEFs or effectors that will ultimately displace RhoGDI and propagate the signal. Furthermore, membrane lipid signals may act synergistically in the activation of GTPases by localizing and activating their respective GEFs through their pleckstrin-homology domains. Conversely, they may provide an alternative activation mechanism where the GEFs are inhibited by these lipids [4].

PtdIns(4,5)P2 may also operate indirectly through other proteins that subsequently act as displacement factors. For example, the unfolding and activation of ERM proteins occurs through several pathways but a common requirement is the presence of PtdIns(4,5)P2 [56,57]. Accordingly, full-length radixin does not interact with RhoGDI [46]. The prior unfolding of ERMs by PtdIns(4,5)P2 may promote association with RhoGDI and concomitant Rho GTPase release.

CELLULAR FUNCTIONS OF RhoGDI

Targeting to membranes and subcellular compartments

Mutants of Cdc42 [58,59] and Rac1 [60] defective in RhoGDIα binding (due to substitution of Arg66 with Glu) are nevertheless able to target to membranes and induce filopodia formation or membrane ruffling. Likewise, in null RhoGDIα mesangial cells, transfection of activated Cdc42 or Rac1 mutants [59,60] exhibited the same spectrum of actin reorganization events compared with wild-type cells. Therefore RhoGDI may not have an escort role for the delivery of nascent prenylated Rho proteins from sites of post-translational modification to resident compartments in a manner analogous to that of the Rab escort protein for the Rab GTPases [61]. This suggests that other molecules may assist in the solubilization of nascent Rho GTPases and that actin reorganization events mediated by Rac1 and Cdc42 do not rely on control by RhoGDI. However, these studies utilized overexpression of the respective GTPases, including use of activated mutants [59,60], so that these GTPases evaded control by GAPs. Therefore conclusions about actin reorganization effects in the absence of RhoGDI remain tentative. It appears that the C-terminal hypervariable regions of Rho family GTPases are sufficient to enable delivery to the various resident membrane compartments, rather than their binding to RhoGDIα [14]. However, RhoGDI does control the partitioning between the cytosol and membrane compartments and may facilitate the targeting of GTPases to appropriate signalling sites.

The R66A RhoGDI-binding-deficient mutant of Cdc42, when superimposed on the constitutively active, transformation-related F28L mutation, efficiently down-regulated its transforming potential [62]. Likewise, siRNA (small interfering RNA) knock-down of RhoGDIα had the same effect on NIH-3T3 cells stably transfected with the Cdc42(F28L) single mutant. While these mutants were competent in effector protein binding, immunofluorescence analysis revealed that, whereas the Cdc42(F28L) protein localized to both Golgi and plasma membranes, the Cdc42(F28L, R66A) protein was exclusively localized to the Golgi [62]. It was therefore proposed that the difference in transformation potential lay in the ability of RhoGDI to shuttle and target Cdc42 to different subcellular compartments. The shuttling potential of RhoGDI had previously been proposed as a means of integrating activation signals for Rho GTPases occurring at areas remote from sites of action [63].

RhoGDI and GTPase coupling to effectors

More complex roles for RhoGDI are suggested by studies of secretion [64], NADPH oxidase activation [65,66] and phospholipase Cβ2 activity [67]. These functions could be reconstituted in vitro by administration of a RhoGDI–Rho protein heterodimer, indicating that RhoGDI is capable of presenting Rho family GTPases to appropriate effectors or complexes in such a way that ensures initiation of enzymatic activity prior to release and membrane association of the GTPase.

On the other hand, stable multimolecular signalling complexes involving Rho–RhoGDI heterodimers have also been described. The first to be isolated was Rac1–RhoGDIα associated with phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase and diacylglycerol kinase [68]. Both Rac1 and RhoGDIα were linked to phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase and diacylglycerol kinase activities, although Rac1 associated directly with the kinases and probably mediated the interaction of RhoGDIα with the complex [68]. Although characterization of the lipid kinase complex was not carried out in vivo, it does suggest a role for RhoGDI, not by down-regulation of its enzymatic activity itself but in partitioning of GTPase-effector complexes away from their sites of action and targeting them when a stimulus is provided. Tripartite cytosolic complexes of Rac1 with both RhoGDIα and its effector PAK have been isolated by density gradient centrifugation from MDCK (Madin–Darby canine kidney) cells, implying that RhoGDIα–Rac1(GTP)–PAK complexes are readily formed in the cytosol of resting cells, while a stimulus promotes membrane translocation of the Rac1–PAK complex [69].

Collectively, these findings propose the existence of RhoGDI-regulated protein complexes of GTPases with effectors and enzymes. These complexes have the potential for rapid translocation to membranes and the initiation of a specific signalling cascade regulated by the GTPase. RhoGDI in these cases may expedite both the delivery and the extraction of the complex, contributing to fast signal termination.

RhoGDI and regulation at membrane domains

In contrast, active Rac1 in fibroblasts was found in a cytosolic complex with RhoGDIα, and uncoupled from its effector PAK, unless cells were stably adherent [70]. It was later shown in a FRET (fluorescence resonance energy transfer)-based assay that Rac1 release from RhoGDIα and effector binding was confined to regions of β1-integrin engagement [71]. These may be lipid rafts, specialized membrane domains rich in cholesterol, possibly organized and maintained at the cell surface by the β1-integrin receptors [72]. Indeed, the cholesterol-enriched membrane fraction from adherent cells could stimulate release of Rac1(GTP) from RhoGDIα, unlike the cholesterol-depleted fraction. Furthermore, liposomes with a composition mimicking the liquid-ordered state of endogenous lipid rafts were also capable of releasing Rac1(GTP) from RhoGDIα [72]. The composition and physical state of the membrane may therefore promote delivery and localized release of GTPases from RhoGDI.

RhoGDIα associates with the developing phagosomes of human neutrophils [73], suggesting a localized delivery and release of the GTPases required for Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis, Rac1 and Cdc42 [74]. RhoGDIα has also been identified as a component of the phagosome proteome [75], although whether it functions to deliver or extract GTPases during phagocytosis is uncertain. The presence of lipid raft proteins on phagosomes [75], and the similarity of the phagocytic process to cell adhesion [76], suggest an analogous scenario to that involving β1-integrin, where unique membrane compartments are able to deliver Rho GTPases through a RhoGDI-dependent mechanism.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

It is now evident that RhoGDI complexed to a RhoGTPase does not simply represent a ‘dormant’ inhibitory complex (Figure 3A) but a dynamic one. The fact that RhoGDI binding does not involve engagement of all the effector-binding regions on the GTPase [77] permits the formation of higher order complexes responsive to specific and localized signals, able to confer targeting to particular membrane microenvironments (Figure 3B). As RhoGDI seems to lack any special sequences that confer direct membrane association, targeting of RhoGTPases has to be approached through the identification of binding partners for the GTPase–RhoGDI complex.

(A) GDP-bound Rho is complexed to RhoGDI in the cytosol. A displacement factor or signal (e.g. ERM family members or a kinase such as PKCα or PAK) localizes the complex proximal to a membrane compartment (1) and releases the GTPase from RhoGDI (2). Exchange of GDP for GTP is catalysed by a GEF protein (3) and allows the GTPase to associate with effector proteins and propagate its signal (4). GTP hydrolysis facilitated by a GAP protein terminates the signal and allows membrane extraction by RhoGDI (5). (B) Once nucleotide exchange is performed (3), RhoGDI might extract the GTPase from the membrane in its GTP-bound form (6) to either terminate the signal prematurely (e.g. following phosphorylation by PKA) or to redirect the GTPase to a distinct membrane compartment within the cell (7). This might be achieved by prior association with an effector protein or a component of a larger protein complex (8,9) and through the assistance of specific localization signals inherent to the particular membrane domain (e.g. a specific membrane-lipid enrichment).

Although the contribution of RhoGEFs to specific activation of GTPases cannot be overlooked, it appears to be through RhoGDI-organized complexes that delivery of the correct GTPase is achieved. Indeed, release from RhoGDI appears to precede membrane-proximal, GEF-catalysed nucleotide exchange [78], highlighting the importance of correct targeting. On the other hand, numerous RhoGEFs and GAPs with unique subcellular distributions and substrate specificities are also regulated by appropriate signals ensuring a correct balance of GTPase activation and inactivation at the membrane. The interplay between RhoGDI, GEF and GAP proteins and their co-ordinate regulation are therefore aspects that have to be studied in a combined manner. Indeed, reports that RhoGDIβ can interact and act co-operatively with the GEF protein Vav [79], and that RhoA activation in endothelial cells involves PKCα-dependent phosphorylation of both RhoGDIα [42] and p115 RhoGEF [80], supports this notion.

Given the important regulatory roles elicited by RhoGDI, it is intriguing how defects associated with its loss in mice are observed in a tissue-specific and age-dependent manner [19]. The use of invertebrate genetic models, such as C. elegans and Drosophila, to study the functions of RhoGDI in vivo might be revealing. In C. elegans, only one RhoGDI molecule is currently known, yet it is tissue-restricted [9]; therefore this may be a useful system for the study of the effects of RhoGDI in the actin-dependent functions of epithelial and germ cells and might reveal evolutionarily conserved functions for RhoGDI.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yiannis Douridas for help with drawing Figure 2. The authors are supported by a Wellcome Trust Program Grant (number 065940).

References

Articles from Biochemical Journal are provided here courtesy of The Biochemical Society

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1042/bj20050104

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc1184558?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

A Novel Single-Color FRET Sensor for Rho-Kinase Reveals Calcium-Dependent Activation of RhoA and ROCK.

Sensors (Basel), 24(21):6869, 26 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39517770 | PMCID: PMC11548655

Proteomics Analysis of Proteotoxic Stress Response in In-Vitro Human Neuronal Models.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(12):6787, 20 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38928492

CoCoNuTs are a diverse subclass of Type IV restriction systems predicted to target RNA.

Elife, 13:RP94800, 13 May 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38739430 | PMCID: PMC11090510

PLK1 phosphorylates RhoGDI1 and promotes cancer cell migration and invasion.

Cancer Cell Int, 24(1):73, 14 Feb 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38355643 | PMCID: PMC10865702

Hyperglycemic Stress Induces Expression, Degradation, and Nuclear Association of Rho GDP Dissociation Inhibitor 2 (RhoGDIβ) in Pancreatic β-Cells.

Cells, 13(3):272, 01 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38334664 | PMCID: PMC10854874

Go to all (258) article citations

Other citations

Wikipedia

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

ExoS Rho GTPase-activating protein activity stimulates reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton through Rho GTPase guanine nucleotide disassociation inhibitor.

J Biol Chem, 279(41):42936-42944, 02 Aug 2004

Cited by: 23 articles | PMID: 15292224

A Complete Survey of RhoGDI Targets Reveals Novel Interactions with Atypical Small GTPases.

Biochemistry, 60(19):1533-1551, 29 Apr 2021

Cited by: 13 articles | PMID: 33913706 | PMCID: PMC8253491

Uncoupling of inhibitory and shuttling functions of rho GDP dissociation inhibitors.

J Biol Chem, 280(6):4674-4683, 28 Oct 2004

Cited by: 20 articles | PMID: 15513926

RhoGDI-3, a promising system to investigate the regulatory function of rhoGDIs: uncoupling of inhibitory and shuttling functions of rhoGDIs.

Biochem Soc Trans, 33(pt 4):623-626, 01 Aug 2005

Cited by: 7 articles | PMID: 16042558

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Wellcome Trust (1)

Regulation of adhesion through a cell surface proteoglycan.

Prof John Couchman, Imperial College London

Grant ID: 065940