Abstract

Free full text

β-Catenin stabilizes Cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA by interacting with AU-rich elements of 3′-UTR

Abstract

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) mRNA is induced in the majority of human colorectal carcinomas. Transcriptional regulation plays a key role in COX-2 expression in human colon carcinoma cells, but post-transcriptional regulation of its mRNA is also critical for tumorigenesis. Expression of COX-2 mRNA is regulated by various cytokines, growth factors and other signals. β-Catenin, a key transcription factor in the Wnt signal pathway, activates transcription of COX-2. Here we found that COX-2 mRNA was also substantially stabilized by activating β-catenin in NIH3T3 and 293T cells. We identified the β-catenin-responsive element in the proximal region of the COX-2 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) and showed that β-catenin interacted with AU-rich elements (ARE) of 3′-UTR in vitro and in vivo. Interestingly, β-catenin induced the cytoplasmic localization of the RNA stabilizing factor, HuR, which may bind to β-catenin in an RNA-mediated complex and facilitate β-catenin-dependent stabilization of COX-2 mRNA. Taken together, we provided evidences for β-catenin as an RNA-binding factor and a regulator of stabilization of COX-2 mRNA.

INTRODUCTION

Precise regulation of gene expression is important for normal cell functions; hence various steps of transcription and post-transcription may be coupled to coordinately express target genes (1,2). For example, activation of transcription and stabilization of mRNA may have similar impacts on upregulating specific target genes (3). These effects can be mediated by DNA–protein interactions on regulatory regions, and RNA–protein interactions on the UTRs of mRNAs. There are examples of dual-specificity nucleic acid binding proteins that are important to transcriptional as well as post-transcriptional regulations (4,5).

β-Catenin is a multifunctional protein that interacts with many proteins, including the sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor TCF and other proteins implicated in transcription and chromatin remodeling (6). Such promiscuous interactions suggest that β-catenin may be involved in diverse cellular functions (7). For example, it was originally identified as a cell adhesion protein but later recognized as a key transcriptional regulator of Wnt signaling. However, it is not clear at this point whether β-catenin is also involved in other cellular functions. One way of finding such novel functions is to identify new interaction partners for β-catenin.

The signal transduction pathway leading to β-catenin activation is as follows (8,9). The scaffolding proteins adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and Axin/Axin2 interact with β-catenin, and glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) subsequently phosphorylates β-catenin, which mediates ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of β-catenin (10,11). As β-catenin levels rise, it accumulates in the nucleus, where it activates the transcription of various oncogenic target genes such as cyclin D1, c-myc and MMP-7 (12–15). Significantly, mutations of β-catenin in cancer cells are associated with defects in proteosomal degradation, and the accumulated β-catenin is localized in the nucleus, especially in colon cancer cells (16,17). Therefore, since the nuclear functions of β-catenin may be critical, finding novel interactions could provide a clue to how it contributes to tumorigenesis.

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) is involved in regulating cellular proliferation, differentiation and tumorigenesis (18). It participates in the colorectal caricinogenesis pathway, in which mutation of APC tends to be the initial event (19). Transcription of COX-2 is induced by the Wnt and Ras signaling pathways (20). However, mRNA stabilization is thought to be the major mechanism up-regulating COX-2 expression in colon cancer cells (21). AU-rich elements (ARE) in the proximal region of the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of COX-2 are responsible for rapid decay of the mRNA and are recognized by a multimeric protein complex containing HuR and other RNA binding proteins (22,23). ARE binding proteins recruit exosome to degrade mRNA (24). Altered expression of the mRNA stabilizing factor HuR is believed to be critical for promoting COX-2 expression in colon cancer cells (25,26).

Here we report an unexpected mechanism by which β-catenin controls COX-2 gene expression at both the transcriptional and post-transcriptional level. COX-2 is a β-catenin target gene that is transcriptionally activated by Wnt signaling (20). We show here that activated β-catenin stabilizes COX-2 mRNA and binds to ARE in its 3′-UTR. Stabilization of COX-2 mRNA is likely to be mediated by the interaction between β-catenin and HuR. Since increasing mRNA stability has the same effect as upregulating transcription, we suggest that β-catenin-induced mRNA stabilization could also potentiate the oncogenic effect of β-catenin in cancer cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and reagents

The retroviral vector expressing human S37A β-catenin was kindly provided by Dr Jang-Soo Chun (Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology). Bacterial expression vectors for recombinant β-catenin and HuR proteins were obtained from Dr Tsutomu Nakamura (University of Tokyo) and Dr Yoshikuni Nagamine (Friedrich Miescher Institute), respectively. The bacterial expression vector for Arm 1-12 was constructed by inserting the armadillo repeat sequence into the BamHI–XhoI sites of the vector pGEX-5X (Pharmacia). The reporter plasmids for the transcriptional pulse assays, designated pBBBΔUTR and pBBBCOX-2 UTR, were a gift of Dr Jiahuai Han (Scripps Research Institute). Luciferase reporters containing COX-2 UTR were kindly donated by Dr Stephen M. Prescott (University of Utah) and have been described previously (21). The luciferase reporter for F1 AS was generated by subcloning the F1 fragment into pGL3 vector using the XbaI site. Anti-HuR monoclonal (3A2) antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz, and the anti-β-catenin monoclonal antibody from Transduction Laboratories. Lithium chloride (LiCl) and MG132 were obtained from Sigma.

Cell culture and transient transfection

Mouse NIH3T3 cells, human embryonic kidney 293T, colorectal adenocarcinoma HT-29 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and transfected using lipofectAMINE (Invitrogen). Luciferase activity was determined using the dual-luciferase assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's directions, and measured with a Turner Luminometer TD-20/20.

Preparation of RNA transcripts

To determine the β-catenin binding site, the full-length COX-2 3′-UTR served as template and was amplified by PCR using primers containing the T7 polymerase promoter. The primers for the F1 UTR were forward, 5′-AGTTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAAGTCTAATGATCATATT; reverse, 5′-AGTCTAGATCACAAGTATGACTCCTT. The primers of F2 UTR were forward, 5′-AGGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTATTAAGGTGGTGGAGCC; reverse, 5′-GGTCTAGATTGGTTATTGCTTTATGT. The primers of F3 UTR were forward, 5′-AGATAATACGACTCACTATAGGGATGACCTCATAAAATACC; reverse, 5′-GATCTAGAGTCTCTTAGCAAAATGGC. The oligonucleotides corresponding to F1-1, F1-2, F1-2 (MT) and F1-3 indicated in Figure 3A were synthesized by Bioneer (Korea). For in vitro synthesis of RNA transcripts, template DNA was incubated in a standard transcription reaction containing [α-32P]-UTP. All the labeled RNA transcripts were gel purified and quantified by liquid scintillation counting.

Analysis of mRNA decay

NIH3T3 cells transfected with the pBBB vectors were serum starved for 24 h, followed by stimulation with 20% fetal bovine serum. Total cytoplasmic RNA was extracted at intervals for the time-course experiments (27). An aliquot of 1–2 μg of the DNAse I-treated RNA was reverse transcribed with Superscript II Reverse transcriptase (Stratagene). Rabbit β-globin mRNA levels were measured by RT–PCR or real-time PCR. The primers for pBBBΔUTR were forward, 5′-TAGAATTCCTCCTGGGCAACGTGCTG-3′; reverse, 5′-CGTCTAGATCAGTGGTATTTGTGAGC-3′. The luciferase mRNA of pGL3 (Promega) was used in transient transfection experiments as an internal control and standard. Real-time PCR was performed with a LightCycler system (Roche). Reactions were amplified using an LC FastStart reaction mix SYBR Green I kit (Roche), and quantified with the LightCycler analysis software (Roche). Relative levels of β-globin mRNA are expressed as the ratio of Cp to the internal luciferase control. The primers for the degradation of endogenous COX-2 mRNA were forward, 5′-TTCAAATGAGATTGTGGAAAAAT-3′; reverse, 5′-AGATCATCTCTGCCTGAGTATCTT-3′. The in vitro decay assay was performed as described (28).

EMSAs and supershift analyses

Cytoplasmic extracts (10 μg) and radiolabeled RNA transcripts were incubated at room temperature for 15 min in a binding buffer containing 15 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM DTT and 5% glycerol. Subsequently, unbound RNA was digested for 15 min with 10 U of RNase T1 (Ambion) at 37°C. RNA–protein complexes were resolved on 6% native polyacrylamide gels. For supershift assays, 1 μg of antibody was incubated with each binding reaction for 30 min on ice before the complexes were resolved by electrophoresis. To test whether β-catenin binds directly to the UTR, the labeled RNA was incubated with GST-fusion proteins and assayed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) as described (29).

Immunoprecipitation assays

To confirm the RNA–β-catenin complex, NIH3T3 or HCT116 cells were transiently transfected with the various luciferase reporter plasmids, and incubated with 1% formaldehyde (30). Sonicated lysates were immunoprecipitated with either normal IgG, or anti-β-catenin antibody. Pellet materials were subsequently incubated at 70°C for 1 h to reverse the crosslinks, and the RNA was purified with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and subjected to RT–PCR. The primers for luciferase were forward, 5′-ACGGATTACCAGGGATTTCA; reverse. 5′-AGGCTCCTCAGAAACAGCTC. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were prepared as described previously (31) To test for the endogenous HuR–β-catenin complex in whole cell, cytoplasmic, or nuclear extracts, immunoprecipitation assays were performed after adding heparin (1 mg/ml) or RNases (RNase A, 5 μg/ml; RNase T1, 100 U/ml), or without further treatment. Bound proteins were examined by western blotting.

RESULTS

β-catenin is required for stabilization of COX-2 mRNA

There is much evidence that COX-2 mRNA is regulated by Wnt signaling and β-catenin overexpression (32–34). However, there is as yet no direct evidence that COX-2 mRNA expression is regulated by β-catenin at the post-transcriptional level. To see whether activated β-catenin affects COX-2 mRNA stability, we used a transcriptional pulsing system that allowed the determination of mRNA decay kinetics without the complication of adding transcriptional inhibitors (27,35). The pBBBCOX-2 UTR plasmid, encoding β-globin mRNA bearing the COX-2 mRNA 3′-UTR, was cotransfected into NIH3T3 cells with a plasmid expressing S37A β-catenin, a stabilized form of β-catenin, or with the empty vector as a control. The β-globin mRNA was transiently transcribed after serum induction of growth-arrested NIH3T3, and its level was measured by real-time PCR. A plasmid encoding luciferase mRNA was included to serve as internal standard. As shown in Figure 1A, β-catenin expression increased the stability of the β-globin mRNA, which was relatively unstable in the control vector-transfected cells. In contrast, β-catenin had little effect on the stability of the β-globin mRNA lacking the COX-2 mRNA 3′-UTR (pBBBΔUTR).

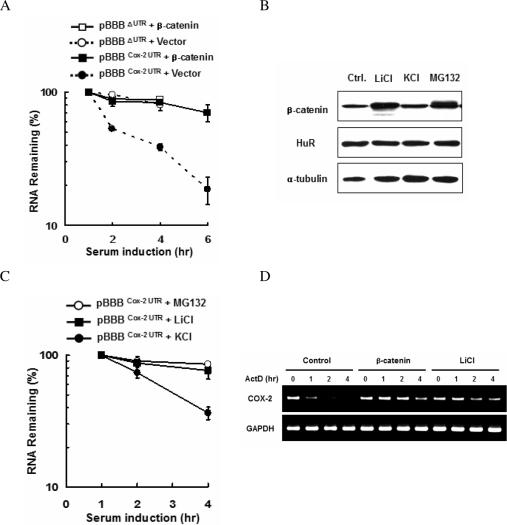

Stabilization of COX-2 mRNA by β-catenin. (A) Real-time PCR analysis of the COX-2 UTR. Cells were co-transfected with the pBBB vector containing β-globin fused to the 3′-UTR of COX-2 mRNA (pBBBCOX-2 UTR) and either empty vector or the S37A β-catenin expression vector. Gene expression was induced by 20% serum, and total cytoplasmic RNA was isolated at different times after serum addition. mRNA stability was determined by measuring β-globin mRNA levels by real-time PCR. (B) Western blot analysis. Cells were treated with KCl, LiCl (20 mM each) and MG132 (20 μM), respectively, and the expression of endogenous β-catenin and HuR was determined by western blotting. Alpha-tubulin served as a loading control. (C) The stabilities of pBBBΔUTR and pBBBCOX-2 UTR in cells as (B) were examined by real-time PCR. The data shown are means ± SE (n = 3), and are representative of three independent experiments. (D) RT–PCR analysis of the endogenous COX-2 mRNA. 293T cells were co-transfected with empty vector (Control), the S37A β-catenin expression vector or LiCl treatment. Actinomycin D (ActD, 10 μg/ml) was added to the culture medium at time 0, and total RNA was isolated at the indicated times, and the amount of COX-2 mRNA was analyzed by RT–PCR. GAPDH served as a loading control.

We next tested whether the accumulation of endogenous β-catenin leads to stabilize pBBBCOX-2 UTR transcripts. Exposure to LiCl, a GSK-3β inhibitor, or MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, increased cellular β-catenin (Figure 1B), and pBBBCOX-2 UTR transcripts were indeed stabilized (Figure 1C). To investigate whether β-catenin regulates the stability of endogenous COX-2 mRNA, 293T cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing S37A β-catenin or treated with LiCl. Transcription was stopped by actinomycin D, and the stability of COX-2 mRNA was analyzed by RT–PCR (Figure 1D). We found that both the expression of β-catenin and LiCl treatment drastically increased the half-life of endogenous COX-2 mRNA.

The proximal region of the 3′-UTR is critical for β-catenin-induced COX-2 mRNA stabilization

To map the regions of the COX-2 3′-UTR responsible for stabilization we utilized luciferase reporters containing the full-length COX-2 3′-UTR or various deletions (Figure 2A). LiCl treatment has no significant effect on luciferase activity in cells transfected with either the luciferase control (ΔUTR) or luciferase lacking the F1 region of the COX-2 3′-UTR (ΔF1). In contrast, it increased the luciferase activities derived from the full-length COX-2 3′-UTR (Full) or the F1 region (F1), suggesting that the F1 region is responsible for the β-catenin-mediated stabilization of COX-2 mRNA (Figure 2B).

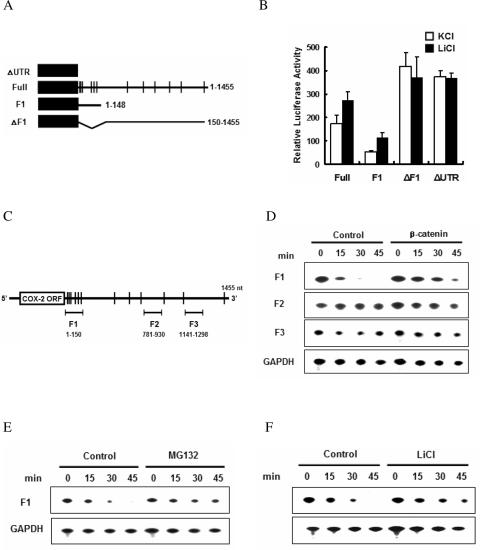

Requirement of the proximal region of COX-2 3′-UTR for β-catenin-dependent stabilization. (A) The reporter construct containing 1455 nt of the COX-2 3′-UTR (connecting line) together with the luciferase coding region (filled box). AU-rich elements are indicated as vertical lines. (B) Luciferase assay. Cells were transfected with various luciferase reporters. Luciferase activities were measured after treatment with LiCl or KCl for 24 h. Three independent experiments were performed. (C) Schematic representation of the locations of the F1, F2 and F3 regions. Vertical lines represent AREs. (D) In vitro RNA degradation assays to identify the β-catenin-responsive element in the COX-2 3′-UTR. [α-32P]-labeled RNA substrates were incubated with cytoplasmic extracts from either vector or β-catenin-expressing NIH3T3 cells, and the reactions were stopped by adding stop buffer at the indicated times. Processed RNA was resolved on a 7 M urea/5% acrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. (E) In vitro analysis of mRNA decay upon MG132 treatment. Labeled F1 mRNA was incubated with cytoplasmic extracts from either DMSO (Control) or MG132-treated NIH3T3 cells, and decay was analyzed as in (D). (F) Stabilization of the F1 UTR by LiCl treatment. Labeled F1 mRNA was incubated with cytoplasmic extracts from either KCl (Control) or LiCl-treated NIH3T3 cells, and degradation was examined as in (D).

There are multiple copies of the AU-rich sequence element (ARE) in the 1455 nt 3′-UTR of COX-2 mRNA. To identify the cis-acting sequences modulated by β-catenin, we examined a cell-free mRNA decay system that has proven useful in mammalian cells (24,28). We synthesized RNA substrates comprising three distinct regions of the COX-2 3′-UTR (F1, F2 and F3 in Figure 2C). Subsequently, the 32P-labeled RNA substrates were incubated with cytoplasmic extracts from either vector-transfected or β-catenin-transfected NIH3T3 cell, and their degradation was measured using denaturing polyacrylamide gels. As shown in Figure 2D, the F2 and F3 mRNA substrates, which do not contain the ARE region, were as stable as the GAPDH mRNA, and were not affected by β-catenin. On the other hand, the F1 mRNA which had a relatively short half-life was stabilized by cytoplasmic extracts containing overexpressed β-catenin. Stabilization of the COX-2 3′-UTR by β-catenin was confirmed using MG132- or LiCl-treated cytoplasmic extracts (Figure 2E and andF).F). These results show that the proximal region of the 3′-UTR is critical for β-catenin-induced COX-2 mRNA stabilization.

The class I AREs in proximal COX-2 UTR are the β-catenin-responsive element

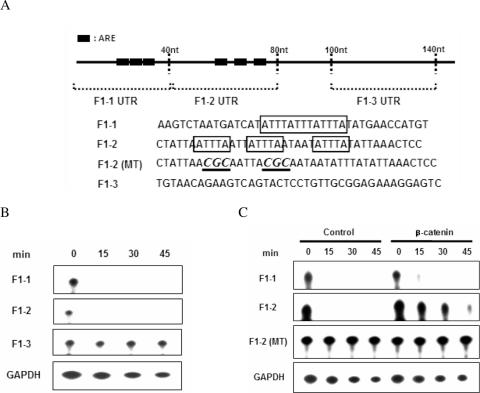

Since the F1 region of the COX-2 UTR contains multiple copies of ARE, we dissected the F1 sequence. AREs are classified into three groups according to features of their sequence and their RNA decay characteristics (36,37). The F1 region of the COX-2 3′-UTR contains both class I ARE with one to three scattered copies of the AUUUA motif and class II ARE with multiple overlapping copies of that motif. To further define the β-catenin-responsive sequences in the F1 region, we further divided the 145 nt of F1 into 40 nt fragments (Figure 3A) and evaluated their degradation rates. We found that both the F1-1 (class II) and F1-2 (class I) fragments were unstable, whereas the F1-3 (non-ARE) fragment was as stable as the control GAPDH mRNA (Figure 3B). We next tested which RNA substrates responded to β-catenin-induced stabilization. As shown in Figure 3C, strong expression of β-catenin stabilized F1-2 rather than F1-1. Furthermore, mutation of the UUU residues of AUUUA to CGC in F1-2 (F1-2 MT) completely abolished the ARE-induced instability. These in vitro decay data indicate that β-catenin is responsible for stabilization of the class I ARE region of the F1 UTR.

Mapping of the β-catenin-dependent stabilizing element in the F1 UTR. (A) Schematic representation of the different F1 UTR probes. ARE sequences are indicated as boxes and mutant sequences are shown by underlining and in italics. (B) RNA substrates were incubated with cytoplasmic extracts from NIH3T3 cells, and the reactions were stopped by adding stop buffer at the indicated times. Processed RNA was resolved on a 7 M urea/5% acrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. (C) RNA substrates were incubated with cytoplasmic extracts from either vector (control) or β-catenin-expressing NIH3T3 cells. mRNA degradation was examined as in (B).

β-Catenin binds to the F1 region of COX-2 3′-UTR

To stabilize COX-2 mRNA β-catenin could either directly interact with the ARE of COX-2 or indirectly affect other signaling proteins. To determine whether β-catenin binds to the COX-2 3′-UTR, RNA-EMSAs were performed with recombinant β-catenin and radiolabeled RNA probes. The β-catenin protein was able to complex labeled F1 RNA (Figure 2A), but did not interact with labeled F2 or F3 RNA (data not shown). The specificity of the RNA binding was also confirmed by competition with excess unlabeled F1 or non-specific NC RNA (38). To characterize the binding specificity of β-catenin to COX-2 3′-UTR, other recombinant proteins were incubated with labeled F1 RNA. The armadillo repeats (Arm 1-12) of β-catenin as well as the ARE-binding HuR protein (26) formed RNA–protein complexes, but the other proteins did not (Figure 4B). RNA-EMSAs also showed that the binding affinity (Kd) of Arm 1-12 for F1 RNA was ~25 nM (Figure 4C). As shown in Figure 4D, the specificity of the RNA binding was confirmed by competition with excess unlabeled F1 or a β-catenin-specific RNA aptamer (H. K. Lee et al., manuscript submitted). Moreover, we found that β-catenin bound to the minimal β-catenin-responsive element, F1-2, but not to mutant F1-2 (data not shown). We conclude that β-catenin associates directly with ARE located in the first 150 nt of the COX-2 3′-UTR.

Specific association of β-catenin with the F1 region of COX-2 mRNA. (A) Specificity of β-catenin binding to RNA. [α-32P]-labeled F1 RNA (80 pM) was co-incubated with recombinant β-catenin supplemented with unlabeled F1 RNA (F1) or non-specific NC RNA (10-, 50-, 200-fold each). Complexes are indicated as the arrow. (B) RNA-EMSAs. [α-32P]-labeled F1 RNA was incubated with C-terminal domain of β-catenin (CTD), HuR, Arm 1-12, T-cell factor (TCF), or GST (200 nM each). (C) The RNA-EMSAs were performed with recombinant Arm 1-12 protein (2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50, 75, 100 and 200 nM), and the complexes are labeled 1–3. The HuR–F1 complex as control is indicated by an open arrowhead. (D) Specificity of Arm 1-12 binding to RNA. Labeled F1 RNA was co-incubated with Arm 1-12 supplemented with unlabeled F1 RNA (F1), aptamer (Apt; 10-, 50-, 200-fold each) or F2 RNA (200-fold). Following incubation, RNA–protein complexes were resolved on 5% native gels and visualized by autoradiography. Input indicates RNA only.

Intracellular interaction of β-catenin with F1 RNA

Since we observed that β-catenin bound to COX-2 3′-UTR with high affinity in vitro, we tested for the interaction in vivo by RNA immunoprecipitation assays. LiCl-treated NIH3T3 cells were transfected with various luciferase reporters (Figure 2A and Antisense of F1, F1AS) and fixed with formaldehyde. Subsequently lysates were immunoprecipitated with either β-catenin or normal IgG, and bound RNA was purified and analyzed by RT–PCR. Only the luciferase mRNA with full-size and F1 UTR were found in the anti-β-catenin immunoprecipitates (Figure 5A). We obtained similar results in β-catenin-overexpressing HCT116 colon cancer cells (data not shown), showing that the F1 region in the proximal COX-2 3′-UTR is sufficient for interaction with cellular β-catenin.

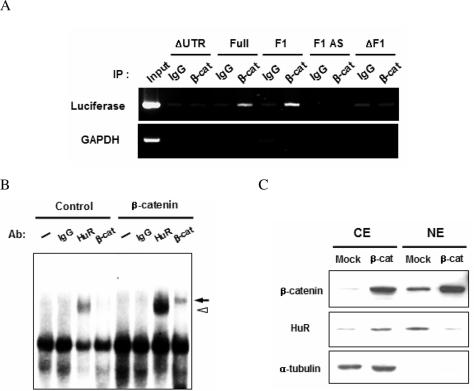

In vivo interaction of COX-2 mRNA with β-catenin. (A) RNA immunoprecipitation assay. NIH3T3 cells co-transfected with various reporters (ΔUTR, Full, F1, ΔF1 as in Figure 2A and Antisense of F1, F1 AS). After formaldehyde fixation, immunoprecipitations were performed with normal IgG or anti-β-catenin antibody. Bound RNA was extracted from the immune complexes and analyzed by RT–PCR. (B) Supershift assay. Labeled F1 RNA was incubated with cytoplasmic extracts of NIH3T3 cells containing either empty vector (control) or β-catenin expression in the presence of normal IgG, anti-HuR, or anti-β-catenin antibodies and analyzed by 5% native gels. The supershifted bands of β-catenin (arrow) as well as of HuR (open arrowhead) are indicated. (C) Cytoplasmic (CE) and nuclear (NE) extracts were prepared from either normal (Mock) or β-catenin-overexpressing (β-cat) NIH3T3 cells and analyzed by western blotting.

We also carried out supershift assays with cytoplasmic extracts prepared from vector- or β-catenin-expressing NIH3T3 cells. Figure 5B shows that RNA–protein complexes were readily detected with both of these cytoplasmic extracts. Control IgG had no effect on the migration of RNA–protein complex whereas a prominent slowly migrating band was detected with anti-HuR antibody, and the intensity of this supershifted band was stronger when a β-catenin-overexpressing cytoplasmic extract was used. Moreover, a supershifted band was also observed when we used anti-β-catenin antibody, demonstrating that β-catenin was present in this RNA–protein complex. Since overexpression of β-catenin promoted the interaction of HuR with F1 RNA but did not alter the level of HuR (Figure 1B), we tested whether HuR localization was affected by overexpressing β-catenin and found that it caused HuR to move from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (Figure 5C). These data indicate that overexpressed β-catenin associates with the COX-2 3′-UTR and induces HuR to translocate to the cytoplasm where it acts to stabilize COX-2 mRNA.

RNA-dependent interaction of β-catenin and HuR

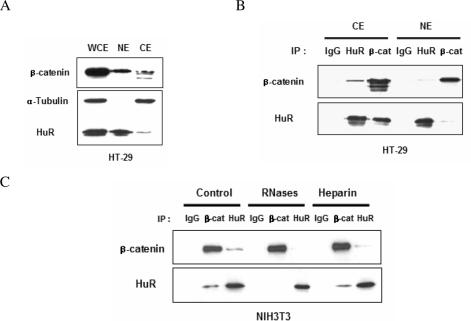

Since both recombinant β-catenin and HuR proteins bound to the F1 region of the COX-2 3′-UTR (Figure 4A), we reasoned that β-catenin and HuR might interact in vivo and this interaction could be related to their binding to COX-2 3′-UTR. To test this hypothesis, we first examined the cellular locations of β-catenin and HuR in HT-29 colon cancer cells. Both β-catenin and HuR were mostly located in the nucleus (Figure 6A). Next, the interaction of β-catenin and HuR was examined by co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments with different subcellular fractions from HT-29 cells. As shown in Figure 6B, co-IP with anti-β-catenin as well as anti-HuR precipitated large amounts of HuR and β-catenin proteins from the cytoplasmic extract, while these interactions were not readily detectable in nuclear extracts.

RNA-mediated interaction between β-catenin and HuR. (A) Whole cell (WCE), cytoplasmic (CE) and nuclear extracts (NE) were prepared from HT-29 colon cancer cells and the distributions of β-catenin and HuR were examined by western blotting. (B) Immunoprecipitation assays were carried out using cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts of HT-29 cells, and either normal IgG, or anti-HuR and anti-β-catenin antibodies, followed by western blotting with the indicated antibodies. (C) IP reactions on extracts of NIH3T3 cells were performed without further treatment (control), or in the presence of heparin or RNases. IP complexes were identified by western blotting.

We next tested whether the interaction between HuR and β-catenin was mediated by RNA. It has been reported that HuR binds to AUF1 in an RNA-dependent complex (31). When we performed IP experiment in the presence of heparin or RNases (Figure 6C) we observed specific disruption of the protein–protein interaction between HuR and β-catenin by the RNases but not by heparin. These results lead us to believe that the interaction between β-catenin and HuR occurs in a cytoplasmic RNA–protein complex that includes COX-2 mRNA.

DISCUSSION

Here we report novel function of β-catenin in the regulation of mRNA stability by direct interaction to mRNA. We have shown above that the transcriptional activator β-catenin binds to the COX-2 UTR and inhibits COX-2 mRNA degradation. Even though β-catenin is known to bind to many different proteins, this is, as far as we know, the first report of its direct binding to nucleic acids. The RNA–β-catenin interaction has many implications for nucleic acid metabolism. Since RNA binding proteins are important in various aspects of post-transcriptional regulation (39), β-catenin may regulate gene expression in various ways, including affecting mRNA stability as shown here.

The functional significance of β-catenin in carcinogenesis is not necessarily restricted to transcriptional activation of target gene expression. Stabilization of unstable mRNA by β-catenin could also have significant impact on the expression of target mRNAs in cancer cells. It was shown here that one of the crucial mRNAs, COX-2, was stabilized by S37A β-catenin in NIH3T3 and 293T cells. In fact, it has been suggested previously that β-catenin might directly or indirectly regulate mRNA stability. For example, recent reports showed that Pitx2, β-TrCP, c-myc and other unstable mRNAs are stabilized by the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and VEGF-D mRNA was destabilized by β-catenin (3,40,41). Significantly, we have now added COX-2 to the list of mRNAs stabilized by β-catenin.

Our results suggest multiple effects of β-catenin on COX-2 gene expression. Since transcription and post-transcriptional processes are coordinated (1,2), β-catenin may also be participate in other steps of gene expression. For example, it is possible that it modulates RNA splicing, and RNA export or translation in addition to mRNA stability. In fact, it was previously shown that β-catenin interacts with the FUS/TLS splicing regulator protein and act as a splicing regulator for estrogen receptor-β (42). Furthermore, since β-catenin regulates many transcripts, such post-transcriptional regulation could affect other mRNAs and provide new insights into the coordinated regulation of multiple target genes by a protein.

We showed that β-catenin binds to the AU-rich RNA sequences of the COX-2 UTR, and also interacts with the RNA binding protein HuR via RNA-mediated interactions. HuR regulates the turnover of many mRNAs. Since it binds to many oncogenic transcripts, altered expression of HuR may be an important factor in colon carcinogenesis (43). For example, HuR binds to many mRNAs and regulates cyclin A and cyclin B1 mRNA stabilization during proliferation (44). However the detailed mechanism of β-catenin- and HuR-mediated stabilization of COX-2 mRNA remains to be clarified. We showed here that β-catenin may coordinate transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation as part of a ribonucleoprotein complex. It points to the possible existence of a specific regulatory pathway that conveys a signal affecting both transcriptional and post-transcriptional changes of target genes.

Acknowledgments

The generous gifts of various DNA constructs from Drs Nakamura, Nagamine, Chun, Prescott and Han are greatly appreciated. This study was supported by grants from the Basic Science Research Fund of the Korea Research Foundation (2004-015-C00378), the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (R01-2006-000-10194-0 and 2005-01131). The Open Access publication charges for this article were waived by Oxford University Press.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

Articles from Nucleic Acids Research are provided here courtesy of Oxford University Press

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkl698

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://academic.oup.com/nar/article-pdf/34/19/5705/11216466/gkl698.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Article citations

3'UTR Diversity: Expanding Repertoire of RNA Alterations in Human mRNAs.

Mol Cells, 46(1):48-56, 20 Jan 2023

Cited by: 14 articles | PMID: 36697237 | PMCID: PMC9880603

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Wnt Signaling Pathway Collapse upon β-Catenin Destruction by a Novel Antimicrobial Peptide SKACP003: Unveiling the Molecular Mechanism and Genetic Activities Using Breast Cancer Cell Lines.

Molecules, 28(3):930, 17 Jan 2023

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 36770598 | PMCID: PMC9920962

Targeting β-catenin in acute myeloid leukaemia: past, present, and future perspectives.

Biosci Rep, 42(4):BSR20211841, 01 Apr 2022

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 35352805 | PMCID: PMC9069440

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Aspirin sensitivity of PIK3CA-mutated Colorectal Cancer: potential mechanisms revisited.

Cell Mol Life Sci, 79(7):393, 02 Jul 2022

Cited by: 10 articles | PMID: 35780223 | PMCID: PMC9250486

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Roles of Embryonic Lethal Abnormal Vision-Like RNA Binding Proteins in Cancer and Beyond.

Front Cell Dev Biol, 10:847761, 06 Apr 2022

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 35465324 | PMCID: PMC9019298

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (53) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Functional antagonism between RNA binding proteins HuR and CUGBP2 determines the fate of COX-2 mRNA translation.

Gastroenterology, 132(3):1055-1065, 19 Dec 2006

Cited by: 58 articles | PMID: 17383427

HuR, a RNA stability factor, is expressed in malignant brain tumors and binds to adenine- and uridine-rich elements within the 3' untranslated regions of cytokine and angiogenic factor mRNAs.

Cancer Res, 61(5):2154-2161, 01 Mar 2001

Cited by: 215 articles | PMID: 11280780

AU-rich elements and alternative splicing in the beta-catenin 3'UTR can influence the human beta-catenin mRNA stability.

Exp Cell Res, 312(12):2367-2378, 15 Apr 2006

Cited by: 32 articles | PMID: 16696969

Complexity of COX-2 gene regulation.

Biochem Soc Trans, 36(pt 3):543-545, 01 Jun 2008

Cited by: 75 articles | PMID: 18482003

Review