Abstract

Free full text

Regulation of p73-mediated apoptosis by c-Jun N-terminal kinase

Abstract

The JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase)/mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathway is a major mediator of stress responses in cells, including the response to DNA damage. DNA damage also causes the stabilization and activation of p73, a member of the p53 family of transcription factors. p73, like p53, can mediate apoptosis by up-regulating the expression of pro-apoptotic genes, including Bax (Bcl2-associated X protein) and PUMA (p53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis). Changes in p73 expression have been linked to tumour progression, particularly in neuroblastomas, whereas in tumours that feature inactivated p53 there is evidence that p73 may mediate the apoptotic response to chemotherapeutic agents. In the present study, we demonstrate a novel link between the JNK signalling pathway and p73. We use pharmacological and genetic approaches to show that JNK is required for p73-mediated apoptosis induced by the DNA damaging agent cisplatin. JNK forms a complex with p73 and phosphorylates it at several serine and threonine residues. The mutation of JNK phosphorylation sites in p73 abrogates cisplatin-induced stabilization of p73 protein, leading to a reduction in p73 transcriptional activity and reduced p73-mediated apoptosis. Our results demonstrate that the JNK pathway is an important regulator of DNA damage-induced apoptosis mediated by p73.

INTRODUCTION

Checkpoint mechanisms exist in cells to allow the repair of damaged DNA prior to cell division, or if the damage cannot be repaired, to trigger apoptosis. Defective checkpoint and apoptotic signalling cascades can lead to inappropriate survival of cells carrying gene abnormalities, thereby increasing the predisposition to cancer. The transcription factor p53 is frequently mutated in human cancers and is part of a family that also includes p63 and p73 [1–4]. p53 plays an important role in DNA-damage-induced apoptosis by up-regulating the expression of pro-apoptotic genes including Bax (Bcl2-associated X protein), PUMA (p53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis), NOXA and p53AIP1 (p53-regulated apoptosis-inducing protein-1) and down-regulating the expression of genes that promote cell survival [1,2].

The less well-characterized p53 family member, p73, is also proposed to be important for DNA-damage-induced responses [3–5]. Indeed, there is collaboration between p53 family members in apoptotic signalling. Both p63 and p73 are required for the p53 response to DNA-damage in MEFs (mouse embryonic fibroblasts) and in the central nervous system [6]. p73 also mediates p53-independent apoptosis in response to specific chemotherapeutic agents [7,8], whereas the ectopic expression of p73 is sufficient to induce apoptosis of cells [9,10]. Since p53 is frequently inactivated in tumours, these studies suggest that p73 status may be important in determining the cellular response to chemotherapeutic agents [7,8]. The mechanism of p73-mediated apoptosis involves the expression of certain p53 target genes [3–5,10]. For example, p73 regulates the expression of PUMA, a BH3-only protein, which promotes the activation and relocalization of Bax to the mitochondrial membrane, resulting in the release of cytochrome c and apoptosis [10].

Understanding the role of p73 in cells is complicated by the existence of multiple isoforms including truncated ΔNp73 (N-terminally truncated p73) isoforms, which lack the transcriptional activation domain [3–5]. The full-length and truncated p73 isoforms are expressed from different promoters [3–5]. ΔNp73 isoforms are anti-apoptotic and interfere with the pro-apoptotic functions of p73 and p53 [3–5]. The relative expression levels of full-length p73 compared with the ΔNp73 isoform may therefore be crucial for determining cell fate.

Compared with p53, the regulation of p73 activity is less well understood, but is likely to be as complex. DNA damaging agents cause the stabilisation of p73 protein levels and increased transcriptional activity mediated by the phosphorylation of p73 by the tyrosine kinase c-Abl [11–13] and the serine/threonine kinase CHK1 (checkpoint kinase 1) [14]. Similar to p53, MAPKs (mitogen-activated protein kinases) may also regulate p73 function. The p38 MAPK is reported to mediate the phosphorylation of p73 [15–17], leading to its interaction with the proline isomerase Pin1 [16] and its recruitment to PML (promyelocytic leukaemia) nuclear bodies [17]. Both these events, in addition to c-Abl-mediated phosphorylation of p73, cause enhanced p300-mediated acetylation and transcriptional activation of p73 leading to the selective up-regulation of pro-apoptotic genes [16–18].

The JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) MAPK pathway is a major stress signalling pathway in cells that plays important roles in many cellular processes, including development, apoptosis, cell growth and immune responses [19,20]. c-Abl activates the JNK pathway in response to DNA damage, and JNK is involved in the apoptotic response to many genotoxic stresses [21–23]. JNK also plays an essential role in promoting c-Abl nuclear localization via the phosphorylation of 14-3-3 proteins that sequester c-Abl into the cytoplasm [24]. However, despite strong evidence that JNK is an important regulator of DNA-damage signalling and the proposed role of JNK in p53 regulation, it is unclear whether JNK has a role in p73 function.

In the present study, we have examined the regulation of p73 by the JNK signalling cascade. We find that active JNK associates with p73 and phosphorylates multiple serine and threonine residues. This leads to p73 protein stabilization, enhanced p300-mediated acetylation of p73 and increased p73-mediated transcriptional activity and apoptosis.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Cycloheximide, SP600125, SB253580, cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatinum), doxorubicin, camptothecin and anisomycin were purchased from Calbiochem.

Plasmids

pSRα-HA-JNK2α2, pcDNA3-HA-MLK3 (mixed lineage kinase 3), pGEX-cJun(1-79) have been described previously [25]. pcDNA3-HA-p73α, pRV-p300, pEBG-JNK2α2 and pEBG-JNK3α1, and GADD45- and Bax-promoter–Luciferase reporter constructs were provided by Dr G. Melino (University of Leicester, Leicester, U.K.) and Dr A. Sharrocks, Dr C. Tournier and Dr C. Demonacos (all from the University of Manchester, Manchester, U.K.) respectively. pRL-TK-Renilla was from Promega. pcDNA3-myc-p73α was constructed by inserting full-length p73α PCR product in between the EcoRI and NotI sites of pcDNA3-myc. All point mutants were generated using the Quikchange® site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and verified by DNA sequencing. Full-length p73α and deletion mutants were generated by PCR and inserted in between the BamHI and NotI sites of pGEX-4T1 (Amersham Biosciences).

Cell culture and transfections

Cos-7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle' medium supplemented with 5% (v/v) FBS (foetal bovine serum) (Invitrogen). U2OS cells were similarly maintained except 10% (v/v) FBS was used. Wild-type and JNK-deficient MEFs were cultured as described previously [26]. H1299/p73α cells [27] were a gift from Dr G. Blandino (University of Rome, Rome, Italy) and were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 400 μg/ml G418 and 100 μg/ml Zeocin (Invitrogen). p73α expression was induced by the addition of 5 μM Ponasterone A (Invitrogen) for 12 h. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine™ (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Human JNK1/2 siRNA (small interfering RNA) (5′-AAAGAAUGUCCUACCUUCUTT-3′) [28] and control siRNA (5′-AGGUAGUGUAAUCGCCUUGTT-3′) were from MWG and used at 50 nM.

Immunoprecipitations and GST (glutathione S-transferase) pull down

Cos-7 cells were washed with PBS and then lysed in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris/HCl (pH7.4), 137 mM NaCl, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 2 mM EDTA, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate and 5 μg/ml leupeptin. GST proteins were isolated by incubating lysates with glutathione–Sepharose 4B (Amersham Biosciences). HA(haemagglutinin)- and myc-tagged p73α were immunoprecipitated using the appropriate antibodies bound to Protein G–Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences). The beads were washed three times in lysis buffer and bound proteins were eluted in 6× SDS loading buffer [300 mM Tris/HCl, pH 6.8, 300 mM SDS, 600 mM dithiothreitol, 30% (v/v) glycerol and 0.1% (w/v) Bromophenol Blue].

Immunoblotting and immunofluorescence

Lysates of MEFs, H1299/p73α and U20S cells were prepared in RIPA buffer 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM PMSF and 5 μg/ml leupeptin]. Immunoblots were performed with antibodies against GST (Amersham Biosciences), HA (Cancer Research UK), myc (Santa Cruz), PUMA, acetyl-lysine and β-actin (all from Abcam), p73 (IMG-259, Imgenex; Ab-3, Oncogene Research Prod.), PARP [poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase] p85 and phospho-cJun (Ser73) (Cell Signaling Technology), JNK1/2 (Pharmingen), p300 (Upstate), phosphoserine and phosphothreonine (RDI and Zymed). Immune complexes were detected with HRP (horseradish peroxidase)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham Biosciences) and enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce). For immunofluorescence studies cells were grown on glass coverslips coated in poly-L-lysine (Sigma), fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (Sigma), and lysed in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. Myc–p73α was detected by indirect immunofluorescence using the anti-myc antibody and Alexa® Fluor594-conjugated secondary antibody (Molecular Probes). Nuclei were visualised by DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining (Molecular Probes).

MS

Cos-7 cells were transfected with constructs expressing HA–p73α with and without GST–JNK3. HA–p73α immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS/PAGE (10% gels). Bands corresponding to HA–p73α were excised from the gel and subjected to digestion with trypsin. Tandem MS analysis was performed using a QStar XL instrument (Applied Biosystems) and the data analysed using Analyst (Applied Biosystems) and Mascot (Matrix Science) software.

Protein kinase assays and luciferase reporter assays

In vitro protein kinase assays were performed as described previously [29]. Active JNK1 was from Upstate. Luciferase assays were performed using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega).

RESULTS

p73 is required for JNK-induced apoptosis in response to cisplatin

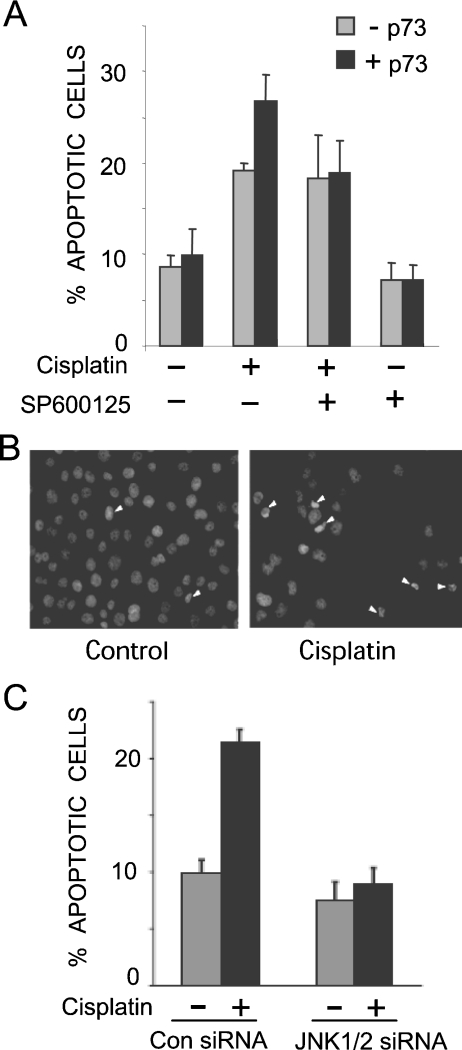

JNK mediates apoptosis in many cell types in response to a variety of stresses [19,20]. Several studies have implicated JNK signalling in the apoptotic response to genotoxins, including cisplatin [21–23], but its importance and the mechanisms involved remain unclear. To determine if JNK plays a role in cisplatin-induced apoptosis via p73, we utilized H1299 cells that feature the inducible expression of the p73α isoform [27]. These cells lack functional p53, so provide a good model for observing p73-dependent signalling events. In the absence of p73α induction, cisplatin induced the apoptosis of H1299 cells, as measured by counting condensed nuclei, whereas the addition of the JNK inhibitor SP600125 [30] did not affect the levels of apoptosis (Figures 1A and and1B).1B). Upon p73α induction, cisplatin treatment increased apoptosis levels, and this p73α-dependent increase was blocked by the JNK inhibitor (Figure 1A). SP600125 has been reported to affect other protein kinases in addition to JNK [31]; therefore, to confirm the role of JNK, we knocked down its expression by siRNA in the H1299/p73α cells, which also led to reduced cisplatin-induced apoptosis (Figure 1C). The effectiveness of the siRNA for reducing JNK expression was confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Figure 2C). These data indicate that JNK is important for p73α-induced apoptosis in H1299 cells.

SP600125 (A) and JNK siRNA (C) block p73α-mediated apoptosis induced by cisplatin. Cells were stained with DAPI and apoptotic cells were counted on the basis of condensed nuclei; for the example depicted in (B) the white arrows point to apoptotic cells. The data represent the means for three independent experiments in which at least 200 cells were counted per condition in a blind manner. (A) H1299/p73α cells were treated overnight with or without ponasterone A (5 μM) to induce p73α expression (−p73 and +p73). Cells were pre-treated with SP600125 (10 μM) for 1 h prior to treatment with cisplatin (25 μM) for 24 h. (C) H1299/p73α cells were transfected with either non-specific control siRNA or JNK1/2 specific siRNA. At 24 h post-transfection ponasterone A was added overnight to induce p73α expression. Cells were then treated with cisplatin (25 μM) for 24 h and analysed as in (A).

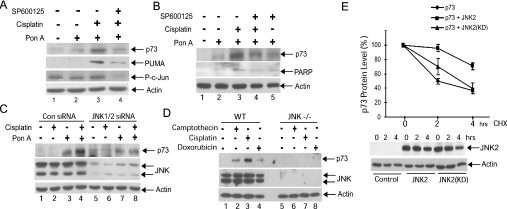

(A, B) The JNK inhibitor SP600125 blocks cisplatin-induced stabilization of p73α in H1299/p73α cells. p73α expression was induced with ponasterone A (Pon A; 5 μM). Cells were treated with 10 μM SP600125 for 30 min prior to treatment with cisplatin (25 μM) for 14 h. (A) Cell lysates were immunoblotted for p73α, PUMA, phospho-c-Jun(Ser73) (P-c-Jun) and β-actin. (B) Lysates were immunoblotted for p73α, PARP(p85) and actin. (C) H1299/p73α cells were transfected with either non-specific control siRNA (Con siRNA) or JNK1/2 specific siRNA. At 24 h post-transfection Ponasterone A (Pon A; 5 μM) was added overnight to induce p73α expression. Cells were then treated with cisplatin (25 μM) for 14 h. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for p73α, JNK1/2 and β-actin. (D) Loss of DNA damage-induced p73 stabilization in JNK−/− MEFs. Wild-type and JNK−/− MEFs were treated with camptothecin (10 μM), cisplatin (25 μM) or doxorubicin (1 μM) for 8 h and the cell lysates were immunoblotted for p73, JNK and β-actin. (E) JNK expression increases the half-life of p73α protein. U20S cells were transfected with constructs expressing HA–p73α together with HA–JNK2. As a control, a kinase-dead JNK2 mutant featuring the mutations K55A and K56A [JNK2(KD)], was used to demonstrate that the effect of JNK2 expression on p73α stability was dependent upon its protein kinase activity. Cells were treated with 10 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated times. p73α immunoblots were analysed by densitometry. The values in the absence of cycloheximide were normalized to 100% to allow direct comparison of p73α stability during the cycloheximide time course under the different conditions. The means for three independent experiments are presented. Representative control immunoblots for HA–JNK2 and β-actin levels are shown.

JNK induces stabilization of p73

To determine the mechanism by which JNK regulates p73 apoptotic activity, we examined whether JNK was required for increased p73 protein stability in response to cisplatin in the H1299/p73α cells. As reported previously [12], cisplatin increased p73α protein levels (Figures 2A, compare lanes 2 and 3; 3;2B,2B, compare lanes 2 and 3; and and2C,2C, compare lanes 3 and 4). Application of either the JNK inhibitor SP600125 or transfection of cells with JNK siRNA blocked the cisplatin-induced change in p73α stability (Figures 2A, compare lanes 3 and 4; and and2C,2C, compare lanes 4 and 8). The JNK inhibitor caused a loss of phosphorylation of the well-characterized JNK substrate c-Jun, demonstrating its effectiveness in these cells (Figure 2A). In addition, we noted that cisplatin caused an increase in the levels of cleaved PARP p85 fragment, a measure of cellular caspase activity, and this was reduced by JNK inhibition (Figure 2B). To determine whether JNK is required for cisplatin-induced stabilization of endogenous p73, we used JNK-deficient MEFs [26]. We found that p73 was stabilized by cisplatin in wild-type MEFs, but not in the JNK-deficient cells (Figure 2D, compare lanes 3 and 7). Furthermore, two other DNA-damaging agents, doxorubicin and camptothecin, both caused p73 stabilization in wild-type MEFs but not in the JNK-deficient cells (Figure 2D, compare lanes 2 and 4 with lanes 6 and 8). To further demonstrate that JNK could increase p73 stability, we measured the half-life of transfected p73α. U2OS cells expressing HA-tagged p73α and either wild-type JNK or a kinase-inactivated JNK were treated with cycloheximide to block new protein synthesis and the levels of p73α expression were measured. JNK expression significantly enhanced the stability of p73α, increasing the half-life of the protein from 2 h to over 4 h (Figure 2E). This did not occur with the inactivated JNK mutant, which suggests that JNK can increase p73 stability in a phosphorylation-dependent manner (Figure 2E). Taken together these data provide strong evidence that JNK activity is required for p73 stabilization in response to DNA damage.

p73α is a JNK substrate

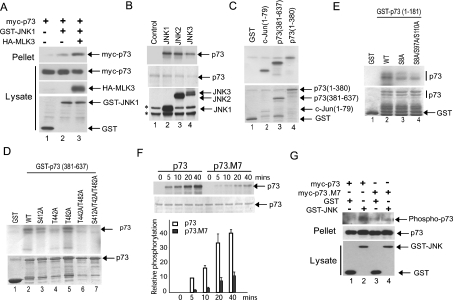

We next sought to determine whether JNK directly interacts with and phosphorylates p73. Co-expression studies in Cos-7 cells demonstrated that JNK1 co-precipitated with p73α, and the level of co-precipitation was increased in the presence of the MAPK kinase kinase MLK3, a potent JNK activator (Figure 3A). We next performed in vitro kinase assays on a GST–p73α fusion protein expressed in and purified from Escherichia coli. All of the JNK isoforms (JNK1, JNK2 and JNK3) directly phosphorylated full-length p73α (Figure 3B). In further protein kinase assays, we utilized a mammalian expression construct that expresses GST–JNK3. We find that this fusion protein displays a high level of JNK activity (E. V. Jones and A. J Whitmarsh, unpublished work), thereby removing the necessity to transfect upstream activating kinases or to treat the cells with external stresses. Using precipitates of GST–JNK3 we performed protein kinase assays on both N-terminal (amino acids 1–380) and C-terminal (amino acids 381–637) fragments of p73α and found both fragments were phosphorylated (Figure 3C, lanes 3 and 4). The primary sequence of human p73α contains 11 potential JNK phosphorylation sites (Ser/Thr-Pro). Previously the phosphorylation of three C-terminal sites (Ser412, Thr442 and Thr482) has been implicated in the binding to the proline isomerase Pin1 and was proposed to involve p38MAPK [16]. We mutated these three sites to alanine, individually and in combination, and performed in vitro kinase assays. Mutation of Thr442 significantly decreased phosphorylation of the p73α C-terminus, whereas mutation of Ser412 partially reduced phosphorylation (Figure 3D, compare lane 2 with lanes 3 and 4). Mutation of all three sites completely blocked phosphorylation of the p73α C-terminus (Figure 3D, lane 7). We identified a further site (Ser333) in the central region of p73α by MS analysis of immunoprecipitates from cells expressing p73α with GST–JNK3; however, mutation of this site alone had no significant effect on p73 phosphorylation in vitro (E. V. Jones and A. J Whitmarsh, unpublished work). To resolve the JNK phosphorylation sites within the N-terminus of p73α we performed further mutational analysis in combination with in vitro kinase assays. Mutation of Ser8 partially reduced phosphorylation of the N-terminus of p73α, with a small further decrease when combined with mutation of Ser97 and Ser110 (Figure 3E). We then mutated the seven potential JNK phosphorylation sites we identified in p73α (Ser8, Ser97, Ser110, Ser333, Ser412, Thr442 and Thr482) and this mutant (p73.M7) showed a significant decrease in JNK-dependent phosphorylation compared with wild-type p73α, although there was some residual phosphorylation of the mutant, indicating that there may be additional phosphorylation sites (Figure 3F). Taken together these data indicate that JNK can phosphorylate p73α in vitro at a number of serine/threonine residues located within both the N- and C-termini. To determine if p73α is phosphorylated in cells by JNK we co-expressed full-length p73α and GST–JNK3, and determined phosphorylation levels using phosphoserine- and phosphothreonine-specific antibodies. We detected increased phosphorylation of p73α in the presence of JNK (Figure 3G). The phosphorylation site mutant (p73.M7), as expected, displayed reduced phosphorylation compared with wild-type p73α (Figure 3G).

(A) Activated JNK binds to p73. Constructs expressing myc–p73α, GST–JNK1 and HA–MLK3 were introduced into Cos-7 cells. GST pull-downs (Pellet) were analysed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody. Expression levels were analysed by immunoblotting cell lysates with appropriate antibodies. (B) The JNK isoforms JNK1, JNK2 and JNK3 all phosphorylate p73α in vitro. In vitro kinase assays were performed using GST–p73α expressed in, and purified from, E. coli, and then incubated with HA-tagged JNK isoforms immunoprecipitated from transfected Cos-7 cells treated with anisomycin (5 μg/ml; 20 min) to activate the JNK isoforms. The products were resolved by SDS/PAGE and analysed by autoradiography. Images of the autoradiograph (upper panel), the Coomassie Blue-stained SDS/PAGE gels (middle panel), and the levels of expression of the HA–JNK isoforms in the Cos-7 cell lysates (lower panel) are shown. *Denotes non-specific bands recognized by the HA antibody in Cos-7 lysates. (C–E) JNK phosphorylates p73α in vitro at multiple sites. In vitro kinase assays were performed using the indicated GST–p73α fragments and phosphorylation site mutants that were expressed in, and purified from, E. coli, and then incubated with GST–JNK3 isolated from transfected Cos-7 cells. GST and GST–c-Jun(1–79) were included as negative and positive controls respectively. The products were resolved by SDS/PAGE and analysed by autoradiography. Images of the autoradiographs (upper panels) and Coomassie Blue-stained SDS/PAGE gels (lower panels) are shown. (F) Mutation of seven potential phosphorylation sites significantly reduces JNK phosphorylation of p73α. GST–p73α and GST–p73.M7 were incubated with recombinant JNK1 (Upstate) in an in vitro kinase assay for the indicated time course. The products were resolved by SDS/PAGE and analysed by autoradiography. Images of a representative autoradiograph (upper panel) and Coomassie Blue-stained SDS/PAGE gel (lower panel) are shown. The results from two independent experiments were quantified and the means are presented. (G) JNK phosphorylates p73α in cells. Constructs expressing myc–p73α or myc–p73.M7 were introduced into Cos-7 cells together with GST or GST–JNK3. Anti-Myc immunoprecipitates (Pellet) were analysed by immunoblotting for phosphorylated serine and threonine residues to detect phosphorylated p73α (Phospho-p73).

Mutation of JNK phosphorylation sites in p73 prevents cisplatininduced p73 stabilization, transcriptional activation and acetylation

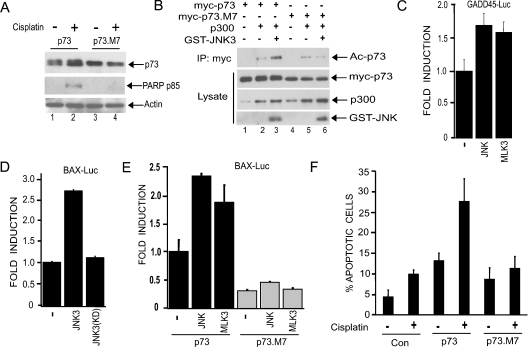

We next sought to determine if mutation of JNK phosphorylation sites in p73α had functional consequences. First, we examined the ability of the p73.M7 mutant to be stabilized by cisplatin. This mutant is not stabilized by cisplatin when compared with wild-type p73α (Figure 4A, compare lanes 2 and 4). Individual point mutations of the phosphorylation sites and various combinations of two or three mutations did not affect cisplatin-induced p73α stabilization (E. V. Jones and A. J Whitmarsh, unpublished work), suggesting that multiple sites on p73α need to be targeted by JNK in order to promote p73α stability in the presence of cisplatin. A previous report has demonstrated that acetylation of the C-terminus of p73α by p300 contributes to p73α activity [18]. To determine whether JNK phosphorylation of p73 regulates its acetylation, we co-expressed p73α or the phosphorylation-site mutant together with p300 in the presence or absence of JNK. JNK enhanced p300-mediated acetylation of p73α, but not that of the mutant, indicating that JNK phosphorylation of p73 is important for efficient acetylation of p73 by p300 (Figure 4B, compare lanes 3 and 6). To determine the effect JNK activity on p73-mediated transcription, we utilized luciferase reporter plasmids featuring the Bax and GADD45 promoters, which contain well-characterized p53/p73-responsive elements. Co-expression of p73α with JNK or the JNK activator MLK3 resulted in increased transcriptional activity from both reporter constructs (Figures 4C–4E). Co-expression of an inactivated mutant of JNK did not enhance p73α-mediated Bax reporter activity (Figure 4D), whereas neither JNK nor MLK3 expression could enhance the ability of the phosphorylation site mutant p73.M7 to activate the Bax reporter gene (Figure 4E). In the absence of p73 expression the JNK pathway components had no effect on reporter gene expression (E. V. Jones and A. J Whitmarsh, unpublished work). These data demonstrate that JNK phosphorylation of p73α can lead to increased transcriptional activity.

(A) U20S cells were transfected with constructs expressing either HA–p73 or the phosphorylation site mutant HA–p73.M7. Cells were treated with cisplatin (25 μM) for 24 h and immunoblots of the cell lysates were performed with antibodies against p73, PARP (p85) and β-actin. (B) JNK phosphorylation of p73 promotes its acetylation by p300. Cos-7 cells were transfected with constructs expressing GST–JNK3 and p300 together with either myc–p73 or the phosphorylation site mutant (myc–p73.M7). Cell lysates were subject to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Myc antibody, and complexes were analysed by immunoblotting with an anti-(acetyl-lysine) antibody in order to detect acetylated p73α (Ac-p73). Protein expression was analysed by immunoblotting lysates with the appropriate antibodies. We detected a band the size of p300 in lysates not transfected with the p300 expression construct, which we assume to be endogenous p300. (C–E) JNK regulates p73-mediated transcriptional activation of GADD45- and Bax-promoter–Luciferase reporter constructs. U20S cells were transfected with the reporter constructs together with either GST–JNK3, GST–JNK3(K93A) [kinase-dead mutant; JNK3(KD)], or HA–MLK3, along with HA–p73 or HA–p73.M7. Luciferase assays were performed and values normalized to the activity of the control reporter, pRL-TK-Renilla. Fold induction represents luciferase activity relative to the value of HA–p73 alone. All transfections were performed in triplicate and the results are shown as means±S.D. (F) JNK phosphorylation sites in p73 are required for cisplatin-induced apoptosis. U20S cells seeded onto coverslips were transfected with constructs expressing myc–p73, myc–p73.M7 or empty vector. Cells were treated with or without cisplatin (10 μM) for 24 h. The percentage of transfected cells (identified by immunofluorescence using an anti-Myc antibody) exhibiting condensed nuclei was calculated. The data represent the means for four independent experiments in which at least 100 cells were counted per condition in a blind manner.

JNK phosphorylation of p73 contributes to cisplatininduced apoptosis

Our data indicate that JNK plays a role in p73α-mediated apoptosis induced by cisplatin (Figure 1). Key apoptotic targets downstream of p73 include Bax and PUMA, which collaborate in the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria, leading to the activation of caspases [3–5,10]. We find that, in response to cisplatin, p73α-mediated PUMA expression is blocked by the JNK inhibitor SP600125, indicating that JNK is required for p73 to mediate the apoptotic cascade (Figure 2A). We would predict that p73α lacking JNK phosphorylation sites would be unable to efficiently induce apoptosis. Indeed, we could not detect cisplatin-induced PARP cleavage, a measure of cellular caspase activity, in the presence of the mutant (Figure 4A). In addition, when U2OS cells were transfected with constructs expressing wild-type or mutant p73α and treated with cisplatin, we observed that p73α expression alone increased apoptosis and this was further increased in the presence of cisplatin; however, cisplatin did not significantly increase apoptosis in the presence of the mutant p73α (Figure 4F). These data strongly support a critical role for the JNK pathway in mediating cisplatin-induced apoptosis via phosphorylation of p73 and regulation of its stability and transcriptional activity.

DISCUSSION

The JNK/MAPK pathway plays pivotal roles in regulating many cellular functions. In the present study, we uncovered a novel role for JNK in mediating DNA-damage-induced apoptosis via p73. JNK binds to p73 and phosphorylates it at multiple sites. We demonstrate that JNK phosphorylation of p73 in response to cisplatin promotes its stabilization, p300-mediated acetylation and transcriptional activity, which leads to PUMA expression and the activation of caspases (Figures 2 and and4).4). Interestingly, the JNK target c-Jun, a member of the AP-1 (activator protein-1) family of transcription factors, may also be involved in promoting p73 stability and activity [32]. Therefore, in addition to directly phosphorylating p73 to regulate its activity, JNK may be indirectly regulating p73 activity through its actions on c-Jun.

Previous reports indicate that the p38 MAPK pathway can regulate p73 [15–17], although the phosphorylation sites have not been mapped precisely. Mantovani et al. [16] implicate three C-terminal residues (Ser412, Thr442 and Thr482) as p38 targets, and propose that the phosphorylation of these sites is required for Pin1 binding and subsequent p300-mediated acetylation. It is also reported that p38 is required for p73 localization into PML bodies [17]. On the basis of the use of a pharmacological inhibitor of p38, we did not find a significant role for p38 in cisplatin-induced p73 stabilization in H1299 cells (E. V. Jones and A. J. Whitmarsh, unpublished work). It is possible that JNK and p38 may differentially regulate p73 according to the type and strength of genotoxic insult or the type of cell.

p53 and p73 target many of the same pro-apoptotic gene promoters, so p73-mediated apoptosis in response to chemotherapeutic agents may provide a way of killing tumour cells under conditions where p53 is frequently inactivated [7,8]. The regulation of p53 and p73 by JNK appears to have similarities, but also distinct differences. Under non-stressed conditions JNK binds to p53 and targets it for ubiquitination and degradation via the 26S proteosome [33]. We have not detected any obvious effect of inactive JNK on p73 stability and indeed, only detect weak binding of JNK to p73 in the absence of an activating signal (Figure 3A). In response to DNA damage, JNK phosphorylates and stabilizes both p53 and p73 (Figures 2 and and4)4) [34]. JNK phosphorylates p53 at a single threonine residue, whereas p73 is phosphorylated at multiple sites (Figure 3) [33]. In both cases additional phosphorylations by other kinases are likely to collaborate with JNK to fully regulate p53/p73 function in response to DNA damage [11–14,35]. For example, c-Abl directly phosphorylates p73 on tyrosine residues in response to DNA damage [11–13], but also activates the JNK pathway [21,22], which we demonstrate here phosphorylates serine and threonine residues on p73 (Figure 3). It will be of interest to determine how these c-Abl/JNK-mediated signalling events are integrated to regulate p73 function.

Overall our results provide strong evidence that the JNK signalling pathway is a critical regulator of p73-mediated apoptosis in response to cisplatin. This extends our knowledge of the diverse roles this signalling pathway can play in the response of cells to stress. In addition, our work furthers the understanding of the mechanisms underlying the apoptotic response to chemotherapeutic agents that are used to treat tumours.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr C. Tournier, Dr C. Demonacos, Dr G. Melino, Dr G. Blandino, Dr A. Sharrocks and Dr R. Davis for reagents. We thank Dr C. Tournier, Dr K. Gehmlich, Dr A. Sharrocks and Dr S.-H. Yang for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the BBSRC (Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council), the Wellcome Trust and a Lister Institute–Jenner Research Fellowship.

References

Articles from Biochemical Journal are provided here courtesy of The Biochemical Society

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1042/bj20061778

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc2267308?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1042/bj20061778

Article citations

Unveiling the Mechanism of Protective Effects of Tanshinone as a New Fighter Against Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review.

Cardiovasc Toxicol, 24(12):1467-1509, 22 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39306819

Review

An Overview of Altered Pathways Associated with Sensitivity to Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Neuroendocrine Tumors: Strengths and Prospects.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(16):8568, 06 Aug 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 39201255 | PMCID: PMC11354135

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

The Interplay between the DNA Damage Response (DDR) Network and the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Signaling Pathway in Multiple Myeloma.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(13):6991, 26 Jun 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 39000097

Review

Metal-Organic Frameworks for Cisplatin Delivery to Cancer Cells: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation.

ACS Omega, 9(17):19627-19636, 22 Apr 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38708264 | PMCID: PMC11064028

Targeting Colorectal Cancer: Unravelling the Transcriptomic Impact of Cisplatin and High-THC Cannabis Extract.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(8):4439, 18 Apr 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38674023 | PMCID: PMC11050262

Go to all (67) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

TAp73-mediated the activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase enhances cellular chemosensitivity to cisplatin in ovarian cancer cells.

PLoS One, 7(8):e42985, 10 Aug 2012

Cited by: 11 articles | PMID: 22900074 | PMCID: PMC3416758

Inhibitory role of Plk1 in the regulation of p73-dependent apoptosis through physical interaction and phosphorylation.

J Biol Chem, 283(13):8555-8563, 03 Jan 2008

Cited by: 40 articles | PMID: 18174154 | PMCID: PMC2417181

c-Jun regulates the stability and activity of the p53 homologue, p73.

J Biol Chem, 279(43):44713-44722, 09 Aug 2004

Cited by: 56 articles | PMID: 15302867

p73 induces apoptosis by different mechanisms.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 331(3):713-717, 01 Jun 2005

Cited by: 106 articles | PMID: 15865927

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (1)

Integration of the JNK and IKK signalling pathways by JIP scaffold proteins

Dr Alan Whitmarsh

Grant ID: C18835

Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (1)

Grant ID: EP/E036252/1

Medical Research Council (1)

Regulation of stress-signalling by proteolysis of JIP scaffold proteins

Dr Alan Whitmarsh, The University of Manchester

Grant ID: G0400620