Abstract

Free full text

Diagnosis of inflammatory demyelination in biopsy specimens: a practical approach

Abstract

Multiple sclerosis is the most frequent demyelinating disease in adults. It is characterized by demyelination, inflammation, gliosis and a variable loss of axons. Clinically and histologically, it shares features with other demyelinating and/or inflammatory CNS diseases. Diagnosis of an inflammatory demyelinating disease can be challenging, especially in small biopsy specimens. Here, we summarize the histological hallmarks and most important neuropathological differential diagnoses of early MS, and provide practical guidelines for the diagnosis of inflammatory demyelinating diseases.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most frequent demyelinating disease in humans. Worldwide, it affects approximately 1 million adults [7]. The annual costs are estimated to amount up to €72,000 per year per patient depending on the severity of the disease.

Due to the typical clinical symptoms, changes in CSF and MRI findings in MS patients, biopsies are only rarely required to establish the diagnosis. However, biopsies are occasionally performed to exclude other treatable diseases such as tumours, vasculitis or viral infections. The histological characteristics of chronic MS lesions are well known to neuropathologists, however diagnosing an inflammatory demyelinating process in biopsy specimens may be challenging since the specimens are frequently small and often represent only parts of a bigger lesion. Furthermore, the histopathological hallmarks of acute MS differ fundamentally from the well-known characteristics of chronic demyelinated plaques observed in autopsies. Here, we describe the histopathological characteristics and most important differential diagnoses of early MS lesions. Histopathologically, the differential diagnoses of multiple sclerosis includes other demyelinating diseases (Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), HURST, vanishing white matter disease, Alexander’s disease, X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) and central pontine myelinolysis (CPM)), inflammatory diseases (vasculitis, viral infections), sentinel lesions preceding lymphomas, tumours (lymphomas, astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas) and infarcts. In the last 3 years, we received about 100 biopsies from patients with MS. About 40 % of the MS lesions were actively demyelinating lesions in which a further classification in different histological patterns according to Lucchinetti, Lassmann and Brück [53] was possible. In our experience the most frequent differential diagnoses include vasculitis and encephalitis. Other disease entities, such as Alexander’s disease, vanishing white matter disease and PML are rare diseases and are even more rarely biopsied. However, at our institution, we have seen single examples of Alexander’s disease (n = 2), vanishing white matter disease (n = 1), few examples of PML (n = 2), ALD (n = 1), measles encephalitis (n = 2), Rassmussen encephalitis (n = 1), sentinel lesions (n = 4) or ADEM/HURST (n = 5) during the last 5 years. CPM and Marchiafavi-Bignami are relatively rare diseases that most likely will not be biopsied. We included them in our list of differential diagnoses since they belong to the spectrum of demyelinating diseases and can be found occasionally in autopsies.

In this review, we discuss the differential diagnoses and suggest practical guidelines for diagnosing inflammatory demyelination in biopsy specimens.

Demyelinating diseases

Multiple sclerosis

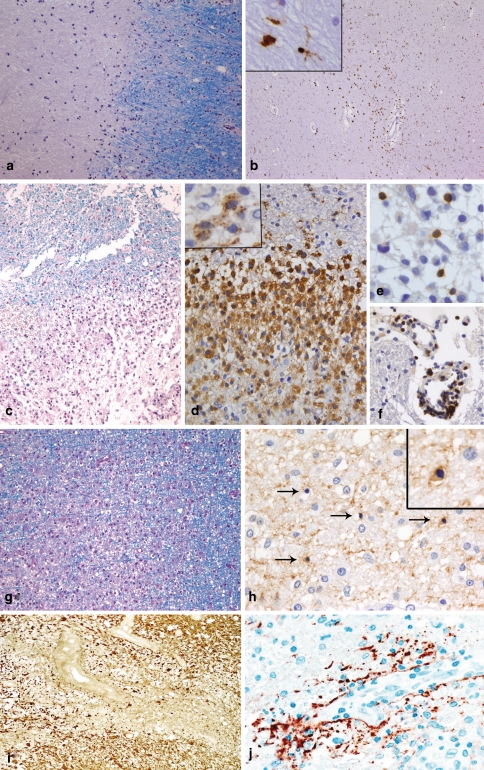

The key features of early MS lesions are demyelination, extensive macrophage invasion, perivascular and parenchymal T cell infiltrates as well as relative axonal preservation. Long-lasting chronic MS lesions (e.g. seen at autopsy) are characterized by a relatively uniform appearance of extensive primary demyelination (Fig. 1a) with variable axonal loss, gliosis and minor infiltration by lymphocytes and macrophages/microglia (Fig. 1b). Early MS lesions show a profound inflammatory reaction consisting of T cells, a variable but low number of B cells and massive infiltration by foamy macrophages at the sites of demyelination (Fig. 1c, d, e, f). A prominent reactive astrocytosis with formation of so-called gemistocytes is another key feature of early MS lesions. In addition, single dividing astrocytes (so-called Creutzfeldt-Peters cells) can be observed. Ongoing remyelinating areas as well as areas with active demyelination can often be seen next to each other [16]. In MS lesions with areas of ongoing myelin destruction, three different patterns based on the myelin protein loss, extent of oligodendrocyte preservation and composition of the inflammatory infiltrates can be distinguished [53]. Patterns I (Fig. 1c, d, e, f) and II share most of the histological characteristics. Both patterns are characterized by a sharp border to the normal appearing white matter and an even loss of all myelin proteins (MBP, CNP, PLP, MAG, MOG). Areas of active demyelination (defined by the presence of myelin degradation products, such as MOG or CNP within the cytoplasm of macrophages [18]; insert in Fig. 1d) are infiltrated by T lymphocytes, some plasma cells and numerous foamy macrophages. Macrophages represent the dominant cell population in MS lesions and easily outnumber T lymphocytes by a factor of 10 (Fig. 1d, e, f). The percentage of CD8-positive T cells varies by around 50–80 % of the T cell population. In contrast to pattern I lesions, pattern II lesions show deposition of activated complement (C9neo) on degenerating myelin sheaths and in macrophages. Pattern III MS lesions are characterized by an ill-defined lesion border (Fig. 1g) and a preferential loss of MAG, while other myelin proteins such as MBP, PLP or MOG are still present or even appear to be overexpressed in the lesion. Pattern III lesions demonstrate a marked oligodendroglial loss; in areas of active myelin degradation, and at the plaque border, oligodendrocytes with apoptotic morphology can be observed (Fig. 1h). The inflammatory infiltrates consist of T cells, activated microglia/macrophages and some plasma cells; complement deposits are not observed in pattern III lesions. A fourth pattern characterized by demyelination due to dying oligodendrocytes in the normal appearing white matter has been described in single autopsy specimens of MS patients with a primary-progressive disease course [53]. Since this pattern has been observed only post mortem in single patients, we do not describe it in more detail here.

Chronic and early MS lesions. Chronic MS lesions have a sharp border with the surrounding normal appearing white matter [NAWM; LFB-PAS staining; (a)]. Frequently, the demyelinated lesion centre is hypocellular while the lesion border and the normal appearing white matter show an increased number of macrophages and/or microglia (immunohistochemistry for the macrophage/microglial marker KiM1P (b) and insert). Early MS lesions with pattern I are characterized by a sharp border with the NAWM [LFB-PAS staining; (c)]. The inflammatory infiltrates are dominated by foamy macrophages [immunohistochemistry for KiM1P (d)], which may contain myelin degradation products in their cytoplasm (immunohistochemistry for the myelin protein MBP (insert in d)). T cells are diffusely distributed within the parenchyma of the lesion (e), but may also be found perivascularly in NAWM [immunohistochemistry for CD3; (f)]. Pattern III lesions show an ill-defined lesion border [LFB-PAS staining; (g)]. In areas of active demyelination and NAWM, numerous dying oligodendrocytes (arrows) with condensed nuclei are observed [immunohistochemistry for CNP; (h)]. The insert in h shows a higher magnification of a CNP-positive oligodendrocyte with a condensed nucleus. In NMO, a loss of astrocytes and glial fibres [immunohistochemistry for GFAP; (i)] as well as a perivascular deposition of complement is observed [immunohistochemistry for C9neo; (j)]

A special variant of inflammatory demyelinating lesions is seen in patients with Devic’s type of neuromyelitis optica. NMO lesions (Fig. 1i, j) [54], which do not necessarily have to be confined to the spinal cord and optic nerves, display necrotic changes in addition to primary demyelination. These lesions are infiltrated by a significant number of eosinophils and neutrophils, in addition to T cells and macrophages, and show prominent vascular fibrosis and hyalinization. Typical features are a profound loss of astrocytes (Fig. 1i) and in particular of the astrocytic protein aquaporin-4 [80]. Complement reactivity, which is found predominantly on astrocytes of the glia limitans, is seen in a rim or rosette-like pattern around vessels [54] (Fig. 1j). In the serum of NMO patients, a specific antibody reaction has recently been identified, which is directed against the astrocytic water channel aquaporin-4 [50], and which may help towards a final diagnosis in such patients.

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and acute haemorrhagic necrotizing leukoencephalitis

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) and acute haemorrhagic necrotizing leukoencephalitis (AHL or Hurst syndrome) are monophasic diseases, which most commonly affect children or young adults. The patients present with multifocal neurological symptoms often associated with a disturbed consciousness [35, 59, 78]. Recurrent disease courses have been suggested in single patients, making a clinical differentiation between ADEM and MS difficult [22, 76]. The clinical outcome of ADEM is typically favourable in contrast to its fulminant variant, Hurst syndrome. The pathophysiology of these diseases is unknown. An autoimmune response to a CNS antigen triggered by infection or vaccination has been discussed as the underlying disease mechanism, since ADEM and Hurst syndrome are often (but not always) associated with preceding infections of the upper respiratory tract or vaccinations [41, 71].

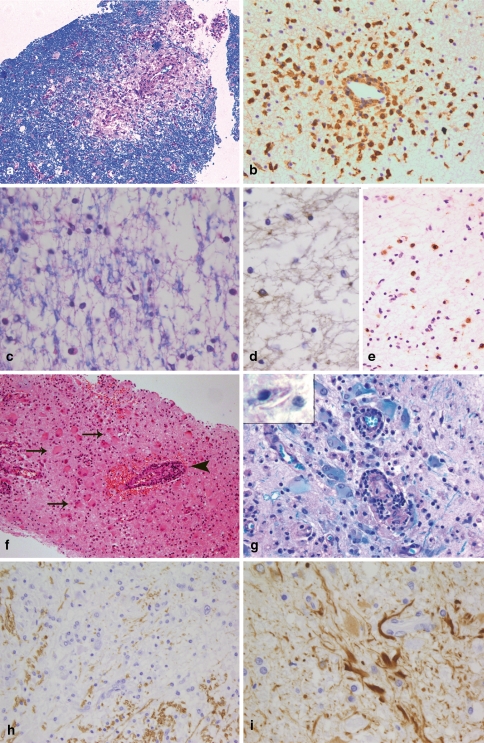

Histologically, ADEM is characterized by small perivascular demyelinating lesions (Fig. 2a), which may be confluent. The perivascular demyelinating “rim” is infiltrated by numerous foamy macrophages and a few lymphocytes (CD3- and CD8-positive T cells, B cells and plasma cells) (Fig. 2b). In general, demyelination is—in contrast to MS lesions—limited to perivascular areas with inflammatory infiltrates. Thus, in brain biopsies profound inflammation in the white matter, which is associated with perivascular demyelination only, is suggestive of ADEM. Having said this, however, it is nevertheless true that essentially similar tissue alterations can be seen in the vicinity of active MS lesions. It is therefore frequently not possible to definitely distinguish between ADEM and MS, in particular when only small biopsy specimens are available.

Different demyelinating diseases. ADEM is characterized by very limited perivascular demyelination [LFB-PAS; (a)] and perivascular infiltrates that consist mostly of foamy macrophages [immunohistochemistry for KiM1P; (b)]. In vanishing white matter, a diffuse loss of myelin is observed [LFB-PAS; (c)]. The number of oligodendrocytes in affected white matter areas is markedly reduced [immunohistochemistry for CNPase (d)]. In contrast to early MS lesions, the demyelinated lesions are infiltrated by relatively few macrophages [immunohistochemistry for KiM1P; (e)]. In X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy, numerous bizarre astrocytes can be found within the lesions (arrows in f) as well as lymphocytic perivascular infiltrates (arrowhead in f; haematoxylin and eosin staining). The lesion areas are completely demyelinated (g) and in macrophages needle-like inclusions may be found (insert in g). In Alexander’s disease large CNS areas with an almost complete loss of myelin are found [immunohistochemistry for MBP; (h)]. The histopathological characteristic of Alexander’s disease is numerous GFAP-positive Rosenthal fibres [immunohistochemistry for GFAP; (i)]

Hurst syndrome displays circular haemorrhages and fibrin deposits around smaller often necrotic vessels together with infiltrates consisting of neutrophils, lymphocytes and macrophages. Among the inflammatory cells, neutrophils are the dominant cell population. Similar to ADEM, the loss of myelin is limited to the area of inflammation. Frequently, the axon cylinders are severely affected resulting in necrotic foci rather than real demyelination [1, 34].

Central pontine myelinolysis

In 1959, Adams described for the first time a disease characterized by demyelinating symmetrically located central pontine lesions and therefore named it central pontine myelinolysis [2]. Subsequent studies revealed that such demyelinating lesions are not confined to the pons, but can be found in other regions of the brain that show a strong admixture of grey and white matter such as cerebellum or the extreme and external capsule [31, 64]. Central pontine myelinolysis (CPM) is a rare disease associated with conditions such as alcoholism, chronic malnutrition, cirrhotic liver disease and transplantation. CPM has been related to a rapid rise of serum sodium from a hyponatremic baseline and similar demyelinating lesions have been found experimentally such as electrolyte-induced myelinolysis in rats [44, 45, 62].

Histopathologically, these lesions are characterized by extensive, sharply demarcated demyelinating lesions. Oligodendrocytes are completely eliminated. The extent of axonal damage varies between patients [30]; older lesions may display cystic (necrotic) cavitations in the centre of the demyelinating lesion [60]. Neurons are well preserved. Within the lesions, numerous macrophages are observed. The number of macrophages as well as the presence of LFB-positive myelin degradation products within the cytoplasm of macrophages depends on the age of the lesion. In contrast to MS lesions, lymphocytic infiltrates are rare. In general, the diagnosis of CPM can be easily made due to the typical distribution of the lesions. Even in rare instances when extrapontine lesions are not accompanied by pontine lesions [31, 64], the lack of lymphocytic infiltrates in CPM lesions makes confusion with early MS unlikely.

A second demyelinating condition observed almost exclusively in alcoholics is Marchiafava-Bignami (MFB) disease. In MFB disease, lesions are mostly located in the corpus callosum, but they may also be found in the optic chiasm, anterior commissure and cortex [38]. The histopathological characteristics are very similar to the changes observed in CPM, indicating that these two conditions may share some pathogenic mechanisms. However, MFB and CPM are rarely observed in the same patient [29].

Vanishing white matter disease

Vanishing white matter (VWM) disease, also called myelinopathia centralis diffusa or childhood ataxia with diffuse central hypomyelination, has only recently been recognized as a disease entity caused by mutations in the EIF2B1 gene family [49, 86]. In the majority of cases, the disease begins neonatally or in early childhood after infections with fever or mild head injuries with an episodic or progressive neurological deterioration. The neurological symptoms include cerebellar ataxia, spasticity, optic atrophy and epilepsy. In addition to disease onset in childhood, adult cases are also described [12, 27, 73]. MRI reveals diffuse signal abnormalities and cystic changes in the cerebral white matter [73, 84, 85]. Due to its neurological characteristics, early disease onset and extensive MRI abnormalities, the disease would only rarely be considered as a differential diagnosis to MS in children. However, in adults the diagnosis of the disease may be difficult. Histopathologically, the disease is characterized by a widespread, diffuse loss of myelin and oligodendrocytes (Fig. 2c, d), accompanied by a significant reduction in axons, characteristics also found in MS lesions [17, 74, 88, 91]. In contrast to early MS lesions, only a moderate infiltration with macrophages/microglia is observed and T and B cells are absent (Fig. 2e) [15]. Although only moderate numbers of macrophages/microglial cells are seen in VWM disease, single macrophages containing myelin degradation products, such as MAG, CNP, etc. within their cytoplasm may be present in some VWM lesions, indicating an active ongoing demyelinating process. In the normal appearing white matter, the number of oligodendrocytes is significantly increased [15, 74]. A substantial number of oligodendrocytes display the morphological characteristics of apoptosis and express apoptosis-related proteins indicating that oligodendroglial cell loss is an early feature in the disease process [15, 88].

Adrenoleukodystrophy

X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy is characterized by adrenal insufficiency and CNS abnormalities. The disease is caused by mutations in the ABCD1 gene leading to the accumulation of very long chain fatty acids (VLCFA) [58]. In the majority of patients, the disease starts in the first or third/fourth decade; only in a subset of patients is the brain affected (cerebral variant of ALD) [57]. Measurement of VLCFA in plasma is the key diagnostic technique and mutation analysis will confirm the suspected diagnosis. Biopsies are needed only in exceptional situations, e.g. in patients in whom the diagnosis is unexpected due to an atypical clinical course. Histologically, cerebral ALD shares many features with MS lesions. Like MS lesions, they are characterized by demyelination, relative loss of axons and inflammation (Fig. 2f). Within the lesions, a diffuse loss of myelin proteins (MBP, CNP, MOG, MAG, PLP) is observed (Fig. 2g) and no sharp border between the lesions and the “normal appearing” white matter can be defined, similar to pattern III MS lesions. The number of oligodendrocytes is reduced within the lesion compared to the NAWM, but we observed only a few oligodendrocytes with an apoptotic or pycnotic morphology, similar to observations described by Ito et al. [36]. The number of axons is reduced and axonal spheroids can be observed. The perivascular and parenchymal infiltrates are composed of CD3- and CD8-positive T cells, plasma cells as well as macrophages, which may contain myelin degradation products within their cytoplasm. We did not see a deposition of complement in macrophages or on myelin, but this has been reported for a subset of patients in an earlier study [72]. Reactive and bizarrely formed astrocytes are scattered through the lesion (Fig. 2f). They are characterized by large, plump cell bodies resembling large gemistocytes. The detection of needle-like inclusions within macrophages is typical for ALD (insert in Fig. 2g). These inclusions can most readily be detected in the Luxol-Fast-Blue/PAS staining where they appear as small, colourless cavities.

Alexander’s disease

Alexander’s disease is caused by mutations in the GFAP gene [51] and was first described by WS Alexander [6] in 1949 and named after him in 1964 by Friede [25], who described six additional cases. An infantile, juvenile and adult variant can be distinguished. The infantile and juvenile type are often characterized by megalencephaly, hydrocephalus, seizures and developmental delay. Patients with an adult onset may show symptoms similar to those of MS patients [40]. MRI characteristics, such as extensive white matter changes with frontal predominance, a periventricular rim on T1, abnormalities in basal ganglia and brain stem and contrast enhancement of particular grey and white matter structures allow the diagnosis of Alexander’s disease in about 90% of patients [87]. The need for a biopsy is limited to unusual disease courses or MRI characteristics such as focal lesions, where the diagnosis of Alexander’s disease is unexpected. Histologically, the most prominent feature in patients with Alexander’s disease is the presence of numerous Rosenthal fibres, which often accumulate perivascularly (Fig. 2i). Although Rosenthal fibres can also be found in MS lesions, they are confined to old chronic lesions in patients with long-standing disease [61, 77]. Due to the extensive loss or pallor of myelin, the disease is regarded as a leukodystrophy (Fig. 2h). In children with classical Alexander’s disease, widespread destruction of myelin, sometimes to the extent of cavitation, can be observed. In contrast, in adults only a patchy pallor of myelin may be observed. Oligodendrocytes are absent or significantly reduced in the most severely affected lesion areas and dying oligodendrocytes with condensed or fragmented nuclei can be observed. The axonal degeneration is mild compared to the extensive loss of myelin. The demyelinated areas are infiltrated by numerous foamy macrophages, while only few lymphocytes are observed. T cells are mostly found perivascularly and most of the T cells are CD8 positive. In addition, a few B cells and plasma cells are seen in the perivascular infiltrates.

Viral infections associated with demyelination

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) was first described in 1958 by Aström, Mancall and Richardson [8]. PML is caused by an infection of oligodendrocytes by the JC virus and it affects patients who suffer from diseases compromising the immune system, such as tuberculosis, leukaemia and AIDS [23, 67, 93].

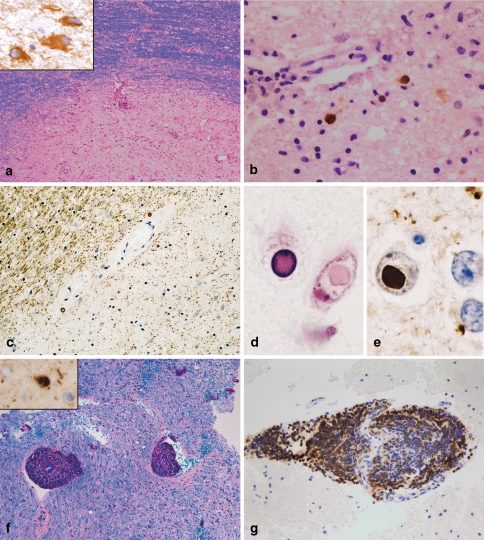

Histopathologically, PML is characterized by demyelinated lesions of different sizes, which may show necrotic areas at the centre of the lesion [46]. The lesions are located in all parts of the brain (hemisphere, brainstem, cerebellum). The borders of the lesions may be ill defined or clearly defined (Fig. 3a). The neuropathological hallmarks are bizarre giant astrocytes (Fig. 3a) and oligodendrocytes infected by JC virus showing enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei (Fig. 3b). The demyelinated areas are infiltrated by numerous foamy macrophages. Perivascular infiltrates consisting of T cells, macrophages and a few B cells may be observed, especially in AIDS-associated PML [46]. JC virus infection as the cause of demyelination can be proven by the detection of JC virus in oligodendrocytes and (more rarely) astrocytes; infected cells are more frequently found at the lesion border than in the demyelinated lesion centre.

PML, SSPE and viral encephalitis. PML lesions may be characterized by a sharp lesion border [LFB-PAS; (a)]. The histopathological hallmarks are bizarre astrocytes (immunohistochemistry for GFAP; insert in a) and viral inclusion bodies in oligodendrocytes and astrocytes [immunohistochemistry with antibodies recognizing JC antigens; (b)]. SSPE is characterized by demyelinated lesions often accompanied by extensive axonal loss [immunohistochemistry for MAG; (c)]. In oligodendroglial nuclei, viral inclusions can be found, which are intensively eosinophilic [haematoxylin and eosin; (d)]. Measles virus antigen can be identified by immunohistochemistry (e). In acute viral encephalitis, e.g. in acute measles encephalitis, marked perivascular infiltrates are observed while the myelin is not affected [LFB-PAS staining; (f)]. In this patient, measles virus antigen could be detected in oligodendroglial nuclei (insert in f). The perivascular infiltrates may be dominated by B cells [immunohistochemistry for the B cell marker CD20; (g)]

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is caused by a persistent measles virus infection. The onset of the disease, that affects mostly children, is insidious, and the outcome often fatal. With the introduction of measles vaccination, the incidence of SSPE has significantly decreased.

First, pathologic changes are observed in the white matter of the hemisphere [63]. The histopathological changes are relatively unspecific: widespread, but focal perivascular infiltrates in the white and grey matter associated with astrocytic proliferation as well as microglial nodules. These inflammatory reactions are accompanied by diffuse demyelination (Fig. 3c), which can be very limited in early disease stages. In neuronal or oligodendroglial nuclei, specific inclusions may be found, the so-called Cowdry type A inclusion bodies. The detection of measles virus antigen by immunohistochemistry leads to the definitive diagnosis of SSPE (Fig. 3d, e) [20].

Encephalitis without demyelination

Encephalitis may present with multifocal lesions in the grey and white matter and is therefore the basis for a possible diagnosis of multiple sclerosis in certain circumstances. Encephalitis without demyelination is most frequently caused by infectious pathogens or an autoimmune process.

Among the infectious pathogens, viral infections are the most important cause of encephalitis without demyelination. Necrotizing viral encephalitis, such as herpes, CMV or VZV, is easy to diagnose; the detection of the virus by immunohistochemistry permits the definitive diagnosis. Unfortunately, there are numerous additional viruses, which may cause encephalitis, but are more difficult to identify. Arboviruses (West Nile virus, Japanese encephalitis, St Louis encephalitis, Western and Eastern equine encephalitis, Central European tick-born encephalitis) and enteroviruses (echovirus, coxsackievirus) are some known examples that infect the CNS and result in encephalitis and/or meningitis. Viral encephalitis affects predominately the cortex. The histological characteristics consist of perivascular and parenchymal infiltrates (lymphocytes, macrophages, microglia; Fig. 3g), microglial nodules as well as dying nerve cells surrounded by microglial cells (neuronophagia; Fig. 3f). Neurons and granzyme B expressing CD8-positive T can be found in close proximity, suggesting a direct cytotoxic effect of CD8 T cells on neurons.

Autoimmune processes are a further cause for encephalitis without demyelination. In a subset of patients, autoimmune-mediated encephalitis is associated with malignancies (also called paraneoplastic encephalopathy or paraneoplastic encephalitis). Limbic encephalitis is the most frequent autoimmune encephalitis with 120 cases described in the literature (for review see [89]. Clinically, it is characterized by short-term memory impairment, temporal lobe seizures and psychiatric symptoms. The typical MRI findings consist of signal abnormalities in the mesial temporal lobes without contrast enhancement [10, 89]. In CSF and/or serum, autoantibodies to neuronal antigens (e.g. Voltage-gated potassium channels or intraneuronal antigens (such as anti-Hu, anti-Ma2)) [10] can be detected in the majority of patients. However, the pathogenesis of autoimmune encephalitis is still a matter of debate; autoantibody-mediated neuronal cell lysis as well as cellular immune mechanisms are discussed [3, 4, 70]. The histological CNS changes in patients with autoimmune encephalitis consist of perivascular T and B cell infiltrates, microglial activation, microglial nodules and gliosis [19, 90]. Rasmussen encephalitis is another rare syndrome in which an autoimmune reaction is the suspected underlying cause of the disease. It affects predominately children, but it can in rare instances also be seen in adults. It is characterized by a progressive destruction of one hemisphere. In early disease phases, the pathological changes consisting of focal and/or perivascular inflammatory infiltrates (with a prominent number of CD8 positive T cells), microglia activation, astrocytosis and single neuronophagia are limited to the superficial and deep cortical layers. Cytotoxic T cells are seen in close association with cortical neurons, suggesting a T cell-mediated mechanism of tissue injury [13]. In addition, profound loss and acute destruction of astrocytes is a characteristic feature of active lesions. In contrast, in late disease phases, extensive destruction with vacuolation of all cortical layers, massive loss of neurons and a prominent astrocytosis were found, while the lymphocytic infiltration was minimal or absent [13]. The subcortical white matter may be affected as well, displaying a diffuse pallor of myelin, loss of axons, foci of lymphocytic infiltrates and reactive astrocytic changes [11, 69].

Vasculitis

CNS vasculitis is a heterogeneous disease group, which represents either isolated vasculitis of the CNS or is part of a systemic vasculitis, such as Wegner’s granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss syndrome, polyarteritis nodosa or collagenoses associated with vasculitis (for review, see [37, 92].

CNS vasculitis mostly affects small- and medium-sized vessels. The histological hallmarks of CNS vasculitis are infiltration of the vessel wall with inflammatory cells (Fig. 4a) and a fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall. The inflammatory destruction of the vessels (Fig. 4b) results in thrombosis of the vessels causing strokes or haemorrhages. The inflammation within the vessel wall consists of macrophages, T cells and B cells, and occasionally giant cells are found as well. The vasculitis may be accompanied by mild to severe inflammatory infiltrates in the CNS parenchyma making the differentiation between MS and vasculitis occasionally difficult in the absence of a fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel walls or thrombotic vessels. In contrast to MS, no demyelination is observed.

In vasculitis, the infiltrates are localized within the vessel wall and consist mostly of T cells [immunohistochemistry for the T cell marker CD3; (a)]. Frequently, the vessel wall is destroyed [reticulin staining; (b)]. Noncaseating granulomas consisting of multinucleated giant cells and epitheloid cells surrounded by a lymphocytic wall are the histological hallmarks of neurosarcoidosis (c). In CNS lymphomas, a perivascular accumulation of neoplastic B cells is characteristic [haematoxylin and eosin; (d)]. The high proliferation index in lymphomas may help to distinguish lymphomas from vasculitis or viral encephalitis. However, occasionally also cases of vasculitis and encephalitis show a marked proliferation. The detection of a monoclonal B cell population by PCR confirms the suspected diagnosis of a B cell lymphoma [immunohistochemistry for the proliferation marker Ki67; (e)]

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a chronic relapsing inflammatory disease of unknown aetiology with variable clinical manifestations; the most common presentation of sarcoidosis is pulmonary involvement. The CNS is affected in 5–25 % of the patients [39, 55, 81]. Cranial MRI reveals the predilection of neurosarcoidosis for the leptomeninges and basal midline structures such as hypothalamus, optic chiasm and the pituitary gland, but also multiple hyperintense parenchymal and periventricular lesions are observed, which may be indistinguishable from MS lesions [56, 65, 83]. In the absence of a systemic disease, pathological evaluation of one of the CNS lesions is the only way to establish the diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis.

Histopathologically, neurosarcoidosis is characterized by non-caseating granulomas consisting of epitheloid histiocytes, lymphocytes, plasma cells and multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 4c). The nuclei in the giant cells are either arranged along the cell border or are randomly clustered in the cytoplasm. In rare instances, necrotizing granulomas can be found in patients with neurosarcoidosis [65]. Ziehl-Neelsen and auramine-rhodamine stainings (mycobactria), silver impregnation techniques (fungi) and examination with polarized light help to distinguish neurosarcoidosis from other granulomatous diseases such as tuberculosis, fungal infections (e.g. histoplasmosis, aspergillosis, cryptococcosis) or foreign body type granulomatous inflammation.

Hypoxic-ischaemic demyelination and necrosis

Multifocal ischaemic lesions may mimic the radiological findings of MS, especially in the early stages [68]. Histopathologically, hypoxia or ischaemia results in necrosis rather than demyelination. In contrast to demyelination, necrotic processes are characterized by loss of axons and myelin. Stainings, which identify myelin and axons will help to distinguish between necrotic and demyelinating diseases. Early stages of strokes, which show a diffuse myelin pallor and preserved axons also display marked neuronal cell death in the affected cortex areas and/or an invasion of granulocytes; neither finding is observed in MS lesions. Binswanger’s disease is characterized by diffuse perivascular demyelination. The atherosclerotic vessel changes and the absence of a marked inflammatory reaction lead to the unequivocal diagnosis of Binswanger’s disease.

Tumours

Sentinel lesions

Malignant lymphoma, which accounts for less than 1 % of all brain tumours, may be associated with or even preceded by demyelinating lesions. The underlying mechanism for developing sentinel lesions is unknown. A viral pathogenesis, malignant transformation of a chronic inflammatory process or demyelination due to anti-myelin antibodies secreted by the lymphoma cells are discussed [32]. The sentinel lesions show typical histological features of MS lesions, such as demyelination, extensive macrophage infiltration, lymphocytic infiltrates consisting of T cells (CD3 and CD8), B cells and plasma cells and a relative preservation of axons. These lesions are indistinguishable from MS lesions by histology [5, 14, 47, 48]. The diagnosis of sentinel lesions should be considered if patients with untypical age of onset of MS (>60 years) present with monofocal demyelinating lesions. MR spectroscopy may help to distinguish between demyelinating disease and lymphoma [47]. For pathology, complete serial sections of the respective biopsy may help to arrive at a definite diagnosis, since in such cases small perivascular angiocentric accumulations of neoplastic T or B cells can be found.

Lymphoma

Primary B cell lymphomas of the CNS (PCNSL) are relatively rare; they account for less than 1% of CNS tumours. Although lymphomas and MS lesions may cause similar MRI changes [52, 66], these two entities can be distinguished easily by histology. B cell lymphomas are easy to diagnose due to their high cellularity, angiocentric growth pattern (Fig. 4d), typical morphology, high proliferation (Fig. 4e), and immunopositivity for B cell markers. However, treatment of patients with steroids prior to biopsy may obscure the diagnosis of lymphoma. Treatment with steroids may lead to the almost complete elimination of the neoplastic B cell population resulting in astrogliosis and perivascular T cell infiltrates resembling vasculitis or encephalitic diseases [28]. Occasionally, B cell lymphomas are preceded by demyelinating lesions, undistinguishable from MS lesions, as described in detail above [5, 14, 47, 48].

A rare variant of PCNSL is the lymphomatosis cerebri that in contrast to the typical PCNSL does not form a cohesive mass, but infiltrates into the CNS diffusely and widely [9, 75]. The patients typically present with rapidly progressive dementia. As a result of the diffuse infiltration of lymphomatosis cerebri, MRI findings may mimic other white matter disorders, such as Binswanger disease, leukoencephalopathy, viral infection or infiltrating glioma [21, 26, 82]. Histopathologically, lymphomatosis cerebri is characterized by the infiltration of the white matter with individual CD20-positive lymphoid lymphoma cells without forming mass lesions [9, 42, 75]. Modest numbers of lymphoma cells together with reactive T cells can be found perivascularly. These histopathological changes may be associated with subtle myelin pallor. One case report describes the presence of focal necrosis [9].

It may be especially challenging to differentiate T cell lymphomas of the CNS from inflammatory entities, such as vasculitis. In a large series of PCNSL (n = 370), T cell origin has been described in 2% of the cases [24]. Primary T cell lymphomas of the CNS frequently show an angiocentric growth pattern. The morphology of the neoplastic T cells has been described as small, medium to large or pleomorphic [33, 79]. Parenchymal necroses as well as necrotic vessels may be present. Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells express CD3 as well as CD8 and perforin or granzyme B [33]. Proliferation is usually prominent. The detection of a clonal T cell receptor gene rearrangement by PCR helps to establish the diagnosis of a T cell lymphoma [33].

Other CNS tumours

Since early MS lesions are characterized by hypercellularity as well as extensive and prominent astrocytosis, they might be confused with astrocytic tumours, especially in small biopsy specimens. Furthermore, reactive astrocytes in MS lesions often display a marked pleomorphism and even astrocytes, with atypical mitotic figures (Creutzfeldt-Peters cells) being observed in MS lesions. Therefore, low-grade astrocytomas, especially those with a prominent gemistocytic component may lead to confusion in the differential diagnosis of demyelinating lesions.

The hypercellularity observed in early MS lesions is at least partly caused by macrophages. Cytologically, macrophages may resemble neoplastic oligodendrocytes. However, while neoplastic oligodendrocytes often have a clear cytoplasm as an artificial reaction to the embedding process, macrophages display a foamy and granular cytoplasm. The presence of demyelination and relative axonal preservation together with stainings identifying macrophages (e.g. CD68, KiM1P) will help to avoid misdiagnosis. Review of the clinical and radiological findings will further help towards a correct diagnosis.

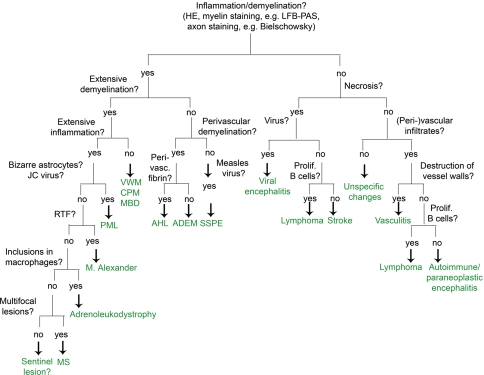

Practical guidelines for diagnosing MS

We recommend starting the diagnostic process with three basic stainings: HE, LFB-PAS myelin staining and a staining for the detection of axons (e.g. Bielschowsky’s silver impregnation). These three stainings are sufficient to determine the extent of inflammation, the localization of inflammatory infiltrates (perivascular versus diffuse in the parenchyma), the extent of demyelination (LFB-PAS) and the severity of axonal damage. Additional immunohistological stainings for macrophages, T cells, B cells, plasma cells, astrocytes and proliferation are sufficient to narrow down the differential diagnosis as described in Fig. 5. Having an additional myelin marker at hand might be helpful, especially because immunohistochemistry for myelin proteins is less time consuming than conventional myelin stainings, such as LFB. We recommend as immunohistochemical myelin markers anti-MBP or anti-CNP, which both reliably label myelin sheaths and, in the case of the latter one, also oligodendrocytes.

Flow chart for the diagnosis of MS and its most important differential diagnosis. ADEM acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, CPM central pontine myelinolysis, AHL acute haemorrhagic necrotizing leukoencephalitis; MBD Marchiafava-Bignami disease, MS multiple sclerosis, PML progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, RTF Rosenthal fibres, SSPE subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, VWM vanishing white matter disease

An important first step in the diagnostic process is to exclude a neoplasm. Stainings for myelin, axons and macrophages will help in distinguishing between MS and a glial tumour. Limited demyelination together with dense (peri-) vascular accumulation of T and/or B cells characterizes lymphomas and vascultits. Additional immunohistochemical stainings for identification of B cells (CD20, CD79a) and proliferation (Ki67) make it possible to differentiate between lymphoma and MS. The detection of a monoclonal B cell population by PCR leads to the unequivocal diagnosis of a B cell lymphoma of the CNS. Extensive demyelination is found in MS, sentinel lesions, PML and rare demyelinating diseases such as Alexander’s disease or leukodystrophies. Alexander’s disease and leukodystrophies can be easily distinguished from multiple sclerosis lesions by the presence of numerous Rosenthal fibres in the former and phagocytic inclusions in the latter. PML is characterized by bizarre astrocytes, and the suspected diagnosis can be proved if JC virus is detected within the oligodendrocytes and/or astrocytes. Other demyelinating diseases such as CPM and vanishing white matter show a very limited number of T and B cells in contrast to MS lesions. By combining a myelin staining with an axonal staining, a demyelinating process can be distinguished from a necrotic one. Necrosis is a very rare finding in MS lesions; except for fulminant MS disease courses, it is rarely observed in MS. When present, a differential diagnosis of NMO should be considered. The presence of necrosis strongly favours the diagnosis of either a necrotic encephalitis or an ischaemic lesion.

Once the diagnosis of an inflammatory demyelinating process is established, further stainings for different myelin proteins, apoptotic cells and the composition of the inflammatory reaction makes it possible to further distinguish one of the different MS patterns as described above [53]. This subclassification can only be performed in actively demyelinating lesions characterized by the presence of myelin degradation products, such as MOG, MAG or CNP within the cytoplasm of macrophages. Since the histological MS pattern may influence the treatment strategies [43], we recommend sending the MS biopsies to specialized centres for further classification.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the research program from the Faculty of Medicine, Georg-August-University Göttingen, the Hertie Foundation and 6th Framework of the European Union, NeuroproMiSe, LSHM-CT-2005-018637. We thank our colleagues from the Departments of Neuropathology from Bremen, Erlangen/Nürnberg, Ulm, Mainz, Greifswald, Department of Pathology and Dermatopathology, Diagnostic Centre, Berlin, the Montreal Neurological Institute, Montreal, Canada as well as our colleagues from the Department of Neurology from the University of Lodz, Poland for providing tissue specimens.

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

Articles from Acta Neuropathologica are provided here courtesy of Springer

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-007-0320-8

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs00401-007-0320-8.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Astroglial connexin 43 is a novel therapeutic target for chronic multiple sclerosis model.

Sci Rep, 14(1):10877, 13 May 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38740862 | PMCID: PMC11091090

Combined laser-activated SVF and PRP remodeled spinal sclerosis via activation of Olig-2, MBP, and neurotrophic factors and inhibition of BAX and GFAP.

Sci Rep, 14(1):3096, 07 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38326395 | PMCID: PMC10850074

Cross-reactivity between Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis 4027 peptide and Human IRF5 may contribute to Multiple Sclerosis in Iranian patients.

Heliyon, 9(11):e22137, 19 Nov 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38034802 | PMCID: PMC10686849

Cerebellar pathology in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: current status and future directions.

J Cent Nerv Syst Dis, 15:11795735231211508, 06 Nov 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37942276 | PMCID: PMC10629308

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Differential Diagnosis of Tumor-like Brain Lesions.

Neurol Clin Pract, 13(5):e200182, 30 Aug 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37664132 | PMCID: PMC10468256

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (66) article citations

Other citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Central nervous system inflammatory demyelinating disorders among Hong Kong Chinese.

J Neuroimmunol, 262(1-2):100-105, 06 Jul 2013

Cited by: 14 articles | PMID: 23838529

Progressive multiple sclerosis cerebrospinal fluid induces inflammatory demyelination, axonal loss, and astrogliosis in mice.

Exp Neurol, 261:620-632, 08 Aug 2014

Cited by: 20 articles | PMID: 25111532

Compartmentalization of inflammation in the CNS: a major mechanism driving progressive multiple sclerosis.

J Neurol Sci, 274(1-2):42-44, 19 Aug 2008

Cited by: 45 articles | PMID: 18715571

Review

The pathological spectrum of CNS inflammatory demyelinating diseases.

Semin Immunopathol, 31(4):439-453, 25 Sep 2009

Cited by: 74 articles | PMID: 19779719

Review

1

1