Abstract

Free full text

A new model for random X chromosome inactivation

Summary

X chromosome inactivation (XCI) reduces the number of actively transcribed X chromosomes to one per diploid set of autosomes, allowing for dosage equality between the sexes. In eutherians, the inactive X chromosome in XX females is randomly selected. The mechanisms for determining both how many X chromosomes are present and which to inactivate are unknown. To understand these mechanisms, researchers have created X chromosome mutations and transgenes. Here, we introduce a new model of X chromosome inactivation that aims to account for the findings in recent studies, to promote a re-interpretation of existing data and to direct future experiments.

Introduction

X chromosome inactivation (XCI) is a process by which mammals reduce the number of active X chromosomes to one per diploid set of autosomes, thereby allowing for dosage equality between the sexes. Normal female cells, with two X chromosomes, are where XCI is most commonly observed. However, it can take place in any cell, male or female, that has more than one X chromosome. During mouse embryogenesis, female cells undergo two separate XCI events. The first, imprinted XCI, is characterized by the inactivation of the paternal X chromosome (Xp) in all cells. In the late blastocyst, cells within the inner cell mass (ICM) reactivate the Xp before a second round of inactivation occurs, called random XCI (Mak et al., 2004; Okamoto et al., 2004). In random XCI, either the Xp or the maternal X chromosome (Xm) is subject to inactivation, and this stochastic choice appears to be made independently in each cell (Lyon, 1961). Once complete, the inactive chromosome is maintained as such throughout the cell lineage (Lyon, 1961). Thus, cells derived from progenitors with an inactive Xp will have an inactive Xp, and those derived from a cell that has an inactive Xm will maintain an inactive Xm. Because gene silencing that occurs from XCI is so stable, it is used as a paradigm for epigenetic gene regulation.

Random XCI can be thought of as occurring in four stages: initiation, spreading, maintenance and reactivation. During initiation, a cell determines how many X chromosomes need to be inactivated to achieve a ratio of one active X chromosome per diploid set of autosomes and identifies which specific chromosomes to inactivate. These processes are called counting and choice (see Glossary in Box 1 for more information). Once a chromosome is designated for inactivation, transcriptional silencing spreads, reducing the expression of almost all of its genes. The inactive status of an X chromosome is then maintained throughout the cell lineage with the exception of the primordial germ cells (PGCs), where it is reactivated by embryonic day (E) 12.5 (Chuva de Sousa Lopes et al., 2008; Kratzer and Chapman, 1981; Monk and McLaren, 1981). In these cells, the epigenetic marks established during XCI are erased and formerly inactivated genes are re-expressed.

Since random XCI was first postulated in 1961, researchers have struggled to identify the mechanisms for counting and choice. The earliest information came from observations of X aneuploid cells and polyploid cells. Because cells with different autosomal ploidies had different numbers of active X chromosomes, the autosomes have been implicated in the counting process. For example, diploid cells almost always have a single active X chromosome, whereas tetraploid cells maintain two active X chromosomes. This led to the notion that a cell maintains one active X chromosome per diploid set of autosomes.

More recent information about how cells count and choose active X chromosomes comes from studies in which sequences within the X inactivation center (XIC) were modified (see Glossary in Box 1). Most of the modifications affected expression of the non-coding RNAs Xist (Borsani et al., 1991; Brockdorff et al., 1991; Brown et al., 1991a) and Tsix (see Box 2 for more information) (Lee et al., 1999a). The Xist and Tsix genes are antisense to each other and are transcribed at low levels prior to XCI. However, during the initiation stage of XCI, Xist and Tsix assume opposite fates on the X chromosomes. Xist is upregulated and its RNA transcripts coat the entire inactive X (Xi) chromosome (Panning et al., 1997; Sheardown et al., 1997), while Tsix is repressed (Lee et al., 1999a). By contrast, increased levels of Tsix transcription repress Xist on the active X (Xa) chromosome (Lee et al., 1999a; Luikenhuis et al., 2001; Shibata and Lee, 2004).

Mutations within the XIC, in the form of large deletions or directed modifications to Xist or Tsix, can pre-determine which X chromosome is to be inactivated or can prevent XCI entirely. Thus, these mutations either directly affect counting and choice mechanisms or override them. Most experimental mutations are performed using mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells, which, when induced to differentiate, are thought to recreate random XCI, as seen in the developing embryo. Mutations in the XIC that either disrupt or bypass counting cause the X chromosome in male cells to be inactivated or prevent XCI in otherwise normal female cells. Mutations that only disrupt or bypass choice do not cause ectopic inactivation in male cells but, in cells with multiple X chromosomes, they ensure the inactivation of either the mutated X chromosome in all cells or the wild-type X chromosome in all cells.

In this Hypothesis article, we review the observations and experiments that shed light on the underlying mechanisms for counting and choice. We then describe the models of XCI that have been developed to interpret these data (Figs (Figs1, 1, ,2)2) and discuss experimental results that they do not account for. Finally, we present our own model, which aims to also account for a number of published experimental results that are not incorporated into these other models. It is our hope that this new model will inspire a re-interpretation of XCI data, as well as future experiments and additional models.

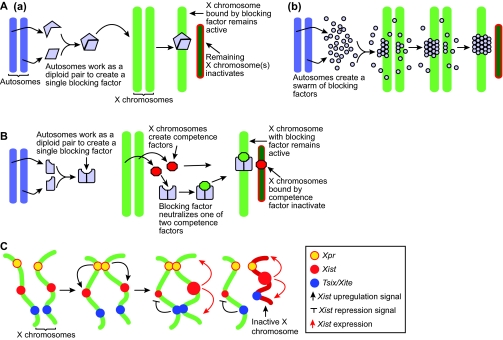

Three models of X chromosome inactivation. (A) The blocking factor model. (a) Diploid autosomes work together to create a single blocking factor (blue shape), which can bind to only one X chromosome, preventing it from inactivating. (b) Nicodemi and Prisco used computer simulations to show that if the autosomes produce a swarm of blocking factors (blue dots) that can bind to each other and to the X chromosome, then all of the blocking factor molecules will accumulate on a single X. (B) The two factor model. Autosomes produce blocking factors and X chromosomes produce transacting competence factors (red shape). Blocking factors bind to competence factors with a two to one stoichiometry and then bind to one X chromosome; the remaining competence factor binds to the other X, which inactivates. (C) The sensing and choice model. After cells start to differentiate, the two Xpr regions (yellow) pair and upregulate Xist (red) on both X chromosmes. The Tsix/Xite region (blue) pairs and chooses which chromosome to inactivate, and represses Xist on the other. The X chromosome that represses Xist remains active (green), and the other becomes inactive (red).

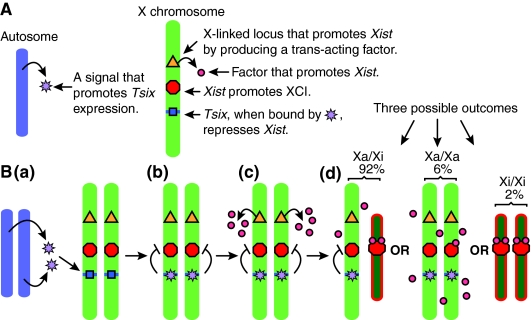

Stochastic model of X chromosome inactivation. (A) The various components of the stochastic model. (B,a) Prior to cell differentiation, the stochastic model proposes that the autosomes produce a trans-acting factor (purple stars) that induces Tsix expression on both X chromosomes (blue shape). (b) Tsix, when bound by autosomal trans-acting factors, represses Xist transcription (red shape). (c) After differentiation, an X-linked locus (yellow triangle) produces a trans-acting factor (red circles) that attempts to upregulate Xist. (d) Competition between Tsix- and Xist-promoting factors creates a probability for each X chromosome to inactivate. Cells that do not inactivate either X chromosome will continue to produce the factor that promotes Xist upregulation in subsequent cell cycles. Cells that inactivate both X chromosomes will either die, or reactivate one. The percentages shown here reflect the proportions of each XCI configuration observed 7 days after differentiation. Xa, active X chromosome; Xi, inactive X chromosome.

What we know about counting, choice and the loci involved

Early evidence of the occurrence of counting during random XCI indicated that autosomes play a role in this process (Lyon, 1972). This conclusion came from the number of Xa chromosomes that are observed in cells with different autosomal ploidies (see Table 1). In general, the more sets of autosomes that are present in a cell, the more Xa chromosomes it will contain. For example, diploid mouse cells maintain one active X chromosome after random XCI, whereas tetraploid cells maintain two active X chromosomes. The difference in the number of Xa chromosomes between diploid, triploid and tetraploid cells indicates that the autosomal ploidy affects counting. Human diploid cells can inactivate up to four X chromosomes in order to create a ratio of one active X chromosome per diploid set of autosomes (Gartler et al., 2006; Grumbach et al., 1963). Although it is not known how autosomes influence counting, one common idea is that they produce trans-acting signals that interact with the X chromosomes.

Table 1.

Counting observed in mouse cells

| Sex chromosomes | Total number of Xs |

Active Xs (number of cells examined)

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | References | ||

| Diploid | |||||||

| XY | 1 | 0% (0) | 100% (229) | - | - | - | Webb et al., 1992 |

| XX | 2 | 0% (0) | 87.8% (547) | 12.2% (76) | - | - | Webb et al., 1992 |

| XX | 2 | 0% (0) | 85.9% (691) | 14.1% (113) | - | - | Speirs et al., 1990 |

| XX | 2 | 2% (3) | 92% (154) | 6% (10) | - | - | Monkhorst et al., 2008 |

| Triploid | |||||||

| XXY | 2 | 0% (0) | 66.5% (123) | 33.5% (62) | - | - | Endo et al., 1982 |

| XXY | 2 | 0% (0) | 82.9% (485) | 17.1% (100) | - | - | Speirs et al., 1990 |

| XXX | 3 | 0% (0) | 70.6% (332) | 29.4% (138) | 0% (0) | - | Endo et al., 1982 |

| XXX | 3 | 0% (0) | 91.7% (676) | 4.1% (30) | 4.2% (31) | - | Speirs et al., 1990 |

| Tetraploid | |||||||

| XXYY | 2 | 0% (0) | 1.8% (2) | 98.2% (110) | - | - | Webb et al., 1992 |

| XXYY | 2 | 0% (0) | 0.4% (3) | 99.6% (672) | - | - | Monkhorst et al., 2008 |

| XXXY | 3 | 0.5% (3) | 6.6% (39) | 84.7% (502) | 8.3% (49) | - | Monkhorst et al., 2008 |

| XXXX | 4 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 90.7% (97) | 2.8% (3) | 6.5% (7) | Webb et al., 1992 |

| XXXX | 4 | 1.3% (8) | 10.5% (63) | 63.6% (383) | 20.3% (122) | 4.3% (26) | Monkhorst et al., 2008 |

Except for the data from Monkhorst et al. (Monkhorst et al., 2008), which uses ES cells, data are taken from embryonic mouse cells after random XCI. The data from Monkhorst et al. (Monkhorst et al., 2008) are taken 7 days after induced differentiation. Summed percentages that exceed 100 are due to rounding.

-, not applicable.

When considering the data presented in Table 1, it is important to understand that secondary cell selection can affect these results and their interpretation. For example, it is possible that a subpopulation of cells in the embryo fail to execute XCI properly and inactivate too many or too few X chromosomes. These cells would be selected against, making them difficult to detect. Takagi and colleagues have shown that cell selection is a significant force in the long-term phenotype of mouse embryos following random XCI (Takagi et al., 2002). Data from Monkhorst et al. also support this conclusion (Monkhorst et al., 2008). They examined diploid XX mouse ES cells 3, 5 and 7 days after the induction of differentiation, and observed all possible XCI combinations, from no Xa chromosome to two Xa chromosomes being present, at all time points. However, the percentage of cells with unconventional XCI patterns decreased over time, demonstrating that these cells were selected against or had modified their inactivation pattern.

It is generally accepted that random XCI initiates from a single region on the X chromosome rather than from multiple regions. Intuitively, this was thought to be the case because XCI is not heterogeneous in the sense of one X chromosome having a mosaic pattern of active and inactive regions that are complementary to the other X chromosome (Gartler and Riggs, 1983). This was later confirmed by translocation studies in both mice and humans (Brown et al., 1991b; Rastan, 1983). The single region on the X chromosome that is responsible for initiating random XCI is called the X chromosome inactivation center (XIC; see Glossary, Box 1). Since the identification of the XIC, there have been many deletion and sequence replacement studies that have aimed to identify the internal elements that directly affect counting or choice (Fig. 3; Tables Tables2, 2, ,33).

Table 2.

Deletions within the mouse X chromosome inactivation center and their influence on random X chromosome inactivation

| Mutant genotype | Observed counting | Observed choice | Tsix/Xite pairing | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XΔ65kb:X | Normal | Skewed | Failed | Clerc and Avner, 1998; Bacher et al., 2006 |

| XΔ65kb:0 | Failed | - | - | Clerc and Avner, 1998 |

| XΔ65kb:Y | Failed | - | - | Morey et al., 2004 |

| XΔ65kb+16kb:X | Normal | Skewed | Normal | Morey et al., 2001; Bacher et al., 2006 |

| XΔ65kb+37kb:0 | Normal | - | - | Morey et al., 2004 |

| XΔDXPas34:Y | Failed (in a small percentage of cells) | - | - | Vigneau et al., 2006 |

| XTsixΔmajor:Y | Failed | - | - | Vigneau et al., 2006 |

| XΔXite:X | Normal | Skewed | Normal | Ogawa and Lee, 2003; Xu et al., 2006 |

| XΔXTX:X | Normal | Skewed | - | Monkhorst et al., 2008 |

| XΔXTX:Y | Normal | - | - | Monkhorst et al., 2008 |

-, not applicable (choice) or not determined (pairing).

Table 3.

Sequence replacements within the mouse X chromosome inactivation center and their affects on random X chromosome inactivation

| Mutant genotype | Observed counting | Observed choice | Tsix/Xite pairing | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XXistΔpromoter:X | Normal | Skewed | - | Penny et al., 1996 |

| XXistΔ1-5:X | Normal | Skewed | - | Marahrens et al., 1997 |

| XXistΔ1-5:0 | Normal | - | - | Marahrens et al., 1997 |

| XXistΔ1-5:Y | Normal | - | - | Marahrens et al., 1997 |

| XTsixΔCpG:X | Normal | Skewed | Normal | Lee and Lu, 1999; Xu et al., 2006 |

| XTsixΔCpG:0 | Normal | - | - | Lee, 2005 |

| XTsixΔCpG:Y | Normal | - | - | Lee and Lu, 1999; Lee, 2005 |

| XTsixΔCpG:XTsixΔCpG | Chaotic | - | Failed | Lee, 2005; Xu et al., 2006 |

| XTsixΔE1:X | Normal | Normal | - | Sado et al., 2001 |

| XTsixΔE1:Y | Normal | - | - | Sado et al., 2001 |

| XTsix IRESβgeo:X | Normal | Skewed | - | Sado et al., 2001; Ohhata et al., 2006 |

| XTsix IRESβgeo:Y | Normal | - | - | Sado et al., 2001; Ohhata et al., 2006 |

| XTsix stop:X | Normal | Skewed | - | Luikenhuis et al., 2001 |

| XTsix stop:Y | Failed | - | - | Luikenhuis et al., 2001; Vigneau et al., 2006 |

-, not applicable (choice) or not determined (pairing).

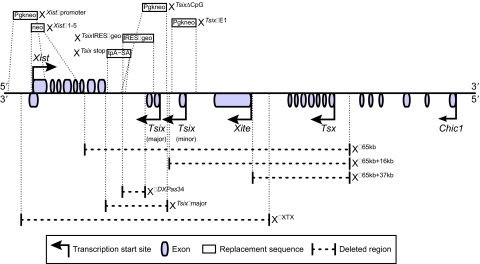

Part of the mouse X chromosome inactivation center and sequence replacements and deletions within it. Sequences used to replace portions of the XIC are shown above the diagram, which shows their relative locations. The effects of these replacements are listed in Table 3. Below the diagram, the dotted lines show XIC regions that have been deleted. The effects of these deletions are listed in Table 2.

In one of the earliest X chromosome deletions, XΔ65kb (del-pBA X) (Clerc and Avner, 1998; Morey et al., 2004), a region from the 3′ Xist exons to the 3′ end of Chic1, was removed (see Fig. 3). All X chromosomes with this deletion, including those in XΔ65kb:X, XΔ65kb:0 (X0; see Glossary, Box 1), and XΔ65kb:Y ES cells, become inactivated after differentiation. The inactivation of the XΔ65kb chromosome in XΔ65kb:X and XΔ65kb:Y ES cells was assessed by the appearance of Xist coating and by the failure for RNA-FISH (fluorescent in situ hybridization) probes to bind to Mecp2 (methyl CpG binding protein 2) and Chic1 (cysteine-rich hydrophobic domain 1) transcripts, both X-linked genes. This indicates that the XΔ65kb deletion disrupts or bypasses counting, as the single X chromosome was inactivated in XΔ65kb:0 and XΔ65kb:Y cells, and disrupts choice, because XΔ65kb:X cells always inactivate the mutant chromosome. The results from the XΔ65kb:0 and XΔ65kb:Y cells suggest that this region contains elements that prevent or repress ectopic XCI.

To refine the XIC region that affects counting and choice, researchers systematically re-introduced genomic fragments into the 65-kb deletion. The first modification, XΔ65kb+16kb, returned 16 kb, including the 3′ Xist exons and Tsix, but not Xite, to the XΔ65kb deletion (see Fig. 3) (Morey et al., 2001). XΔ65kb+16kb:X ES cells preferentially inactivate the mutant chromosomes, indicating that choice remains disrupted in these cells. Because only XΔ65kb+16kb:X cells were examined, it is not clear whether this insertion restores counting. However, once 37 kb was added back to the original deletion, XΔ65kb+37kb (Morey et al., 2004), returning both Tsix and Xite to the mutant X chromosome (see Fig. 3), normal counting was observed in XΔ65kb+37kb:0 ES cells. These results indicate that the 37-kb region between the 3′ Xist exons and the start of the Xite gene contains elements that prevent ectopic XCI.

There is controversy over whether eliminating antisense Tsix transcription through the Xist locus influences or bypasses counting. For example, one mutation, XTsix stop (Ma2L), which inserts a transcriptional stop signal into Tsix before it overlaps with Xist (see Fig. 3), has been reported to cause both low (Luikenhuis et al., 2001) and high (Vigneau et al., 2006) levels of ectopic XCI in male ES cells. Furthermore, Vigneau and colleagues published results from two additional XIC modifications, XΔDXPas34 (Δ34) and XTsixΔmajor (ΔAV) (see Fig. 3), which reduce or eliminate Tsix transcription before the RNA polymerase enters the 3′ Xist exon on the antisense strand. The XΔDXPas34 deletion removes the DXPas34 fragment, a 1.6-kb CG-rich tandem repeat within Tsix. The XTsixΔmajor deletion removes the DXPas34 fragment and the major promoter of Tsix. Vigneau et al. reported that mutant X chromosomes that carry either deletion in male ES cells inactivated after differentiation (Vigneau et al., 2006). In contrast to these experiments, there are two separate Tsix mutations that prevent or severely reduce transcription across Xist, but do not affect counting. Neither the XTsix IRESβgeo mutant (TsixAA2Δ1.7, ΔTsix) (Ohhata et al., 2006; Sado et al., 2001), which replaces the second exon of Tsix after the major promoter with an IRESβgeo cassette (see Fig. 3), nor the XTsixΔCpG mutant (Lee, 2005; Lee and Lu, 1999), which replaces the major promoter of Tsix, the following exon, and the DXPas34 region with a Pgk-neo cassette (see Fig. 3), caused inactivation in male embryos. The results of Ohhata et al. are particularly compelling because they were derived from embryos that carried the Tsix mutation. However, more work needs to be done to resolve this issue.

Some of the most interesting data has come from Jeanie Lee's homozygous XTsixΔCpG ES cells (see Fig. 3) (Lee, 2005). After differentiation, XTsixΔCpG:XTsixΔCpG cells appear to assume one of three XCI patterns. Some cells execute XCI normally and have one active X chromosome; the remaining cells either inactivate both X chromosomes or have two active chromosomes. The cells with one inactive X chromosome appear to undergo random XCI with unbiased choice.

There have also been several mutations within the XIC that affect Xist transcription. Penny and colleagues created XXistΔpromoter mutant chromosomes (see Fig. 3) by replacing the Xist promoter sequence with a Pgk-neo gene (Penny et al., 1996), which prevented all Xist transcription. In XXistΔpromoter:X ES and chimeric embryonic cells only the wild-type X chromosome is inactivated. In order to compare the role of the Xist promoter sequence with that of Xist transcription in promoting gene silencing, Marahrens et al. created XXistΔ1-5, in which the first five Xist exons were replaced with a neo gene while the promoter sequence was left intact and functional (see Fig. 3) (Marahrens et al., 1997). In XXistΔ1-5:X mice, only the wild-type X chromosome inactivates, and in XXistΔ1-5:Y and XXistΔ1-5:0 mice, ectopic XCI is not observed. Most recently, Monkhorst and colleagues removed Xist, Tsix and Xite from the X chromosome, producing the XΔXTX mutation (see Fig. 3) (Monkhorst et al., 2008). They then examined the influence of this mutation in XΔXTX:X ES cells, as well as in XΔXTX:X and XΔXTX:Y mice. In all cells examined, the mutant remained active and the wild-type X chromosome became inactive after random XCI, showing that choice is either disrupted or bypassed by this deletion.

In addition to the XIC mutations that aim to eliminate Xist, Tsix and Xite transcription, there have also been experiments that have increased the expression or dosage of these genes. Mutations that increase Xist transcription cause the X chromosomes with these mutations to be preferentially inactivated (Nesterova et al., 2003). By contrast, mutations that increase Tsix transcription prevent XCI on the mutant chromosome (Luikenhuis et al., 2001). Using a multicopy transgene approach, Lee performed experiments to increase the dosage of Tsix and of Xite. The 5′ end of Tsix, or a large Xite fragment, when present on an autosome in multiple copies could prevent XCI (Lee, 2005); in female ES cells, both X chromosomes remained active after differentiation. Because these transgenes were inserted into autosomes, it is possible that they titrate trans-acting XCI signals.

Recent publications have described that pairing between X chromosomes takes place before XCI (Augui et al., 2007; Bacher et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2006). Pairing between the Tsix/Xite region was observed first (Bacher et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2006), followed by the identification of a region that is 200-kb upstream from Xist, called Xpr (see Box 2), which pairs slightly earlier, after ES cells begin to differentiate (Augui et al., 2007). X chromosome pairing at the Tsix/Xite region is not observed in XΔ65kb:X or in XTsixΔCpG:XTsixΔCpG ES cells (Bacher et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2006). Interestingly, XTsixΔCpG:X and XΔXite:X ES cells show pairing at the Tsix/Xite region (Xu et al., 2006), as do XΔ65kb+16kb:X ES cells. Although it is not known how XTsixΔCpG:X pair when XTsixΔCpG:XTsixΔCpG do not pair, the differences in pairing amongst XTsixΔCpG:XTsixΔCpG, XΔ65kb+16kb:X and XΔ65kb:X cells suggest pairing elements exist within and upstream of Tsix. Xu et al. suggest that Ctcf (CCCTC-binding factor) binding to sites within Tsix and Xite mediate pairing by attracting the Ctcf DNA-binding protein, and additional unknown binding proteins, to the region. The Xpr region has been shown recently to pair as an ectopic, single-copy transgene (Augui et al., 2007). Xu et al. and Augui et al. speculate that pairing at the Tsix/Xite region is part of the mechanism for choice. Augui et al. have also hypothesized that Xpr pairing is involved in determining the total number of X chromosomes in the cell.

Current models for XCI counting and choice

Blocking factor models

Blocking factor models consist of a single signal molecule, or blocking factor (BF), that can prevent XCI on one X chromosome by stabilizing it in a transcriptionally active state (Fig. 1A) (Lyon, 1971). Any remaining X chromosomes inactivate because their active state degrades. BF is thought to be synthesized jointly by the autosomes because of the observation that autosome ploidy affects the number of X chromosomes that remain active.

Recently, Nicodemin and Prisco published a theory on how autosomes could produce a single BF in a way that was resilient to stochastic fluctuations in gene expression (Nicodemi and Prisco, 2007a; Nicodemi and Prisco, 2007b) (Fig. 1A, part b). Instead of hypothesizing that a single molecule acts as a BF, Nicodemi and Prisco proposed that numerous molecules, which can bind both to each other and to certain regions within the XIC, form a compound BF. By binding to each other, the molecules transition from a diffuse cluster to a single compound molecule. This model relies on X chromosome pairing (Bacher et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2006) in order for the diffuse molecules to form the BF within the amount of time required for XCI.

Blocking factor models, however, do not account for the normal counting that is seen in the following transgenic ES cell lines and mice: XXistΔ1-5:X, XXistΔpromoter:X and XΔXTX:X. The XXistΔ1-5, XXistΔpromoter and XΔXTX mutations, which prevent the mutant X chromosome from inactivating, only eliminate possible binding sites for BF, they do not increase their number. Given these mutations, one would expect the BF to bind to the wild-type X chromosome in at least 50% of the cells. Thus, at least half of the cells should maintain two active X chromosomes, the wild-type X chromosome, which stays active because it was bound by BF, and the mutant X chromosome, because it lacks Xist transcription and does not inactivate, but this is not observed (Marahrens et al., 1997; Monkhorst et al., 2008; Penny et al., 1996).

The two-factor model

The two-factor model (Fig. 1B) was originally proposed by Gartler and Riggs (Gartler and Riggs, 1983) and later adopted by Lee to interpret XCI experiments (Lee, 2005; Lee and Lu, 1999). This model relies on a BF that prevents XCI, as well as on a competence factor, C, that initiates XCI. Cells start with two competence factors, produced by the X chromosomes, that function in trans. One C, however, is neutralized by the BF. According to this model, each X chromosome binds either BF, to remain active, or C, to initiate XCI, in a mutually exclusive way (Lee, 2005). Mutually exclusive binding is proposed to be mediated by pairing in the Tsix/Xite region, and mutations that disrupt this pairing are thought to allow both BF and C to bind to the same chromosome (Lee, 2005; Xu et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2006).

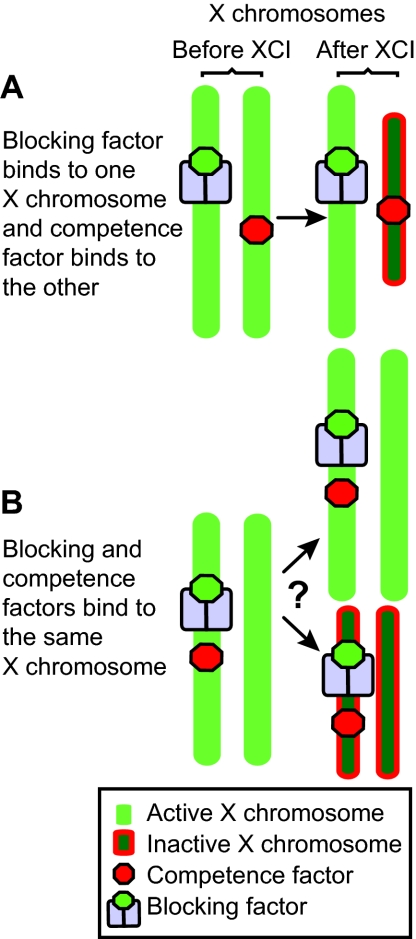

One problem with this model is that it does not account for the XTsixΔCpG:XTsixΔCpG ES cell data in which antisense Tsix transcription across Xist is severely reduced on both X chromosomes. XTsixΔCpG:XTsixΔCpG mutants produce three different cell populations: one with normal XCI, a second in which both X chromosomes remain active, and a third in which both X chromosomes become inactive. The two-factor model, however, can only predict two of the three outcomes. In an XTsixΔCpG:XTsixΔCpG cell, one possibility is that BF binds to one X chromosome and C binds to the other, just like in a wild-type cell. This would result in normal XCI, and this is seen in a fraction of the mutant ES cells after differentiation. The other possibility is that both BF and C bind to the same X chromosome and nothing binds to the other. In this case, both chromosomes may remain active, or both may inactivate, but the model cannot account for the two different outcomes occurring simultaneously, as is seen in Fig. 4.

A problem with the two factor model. After XCI, XTsixΔCpG:XTsixΔCpG ES cells make three cell populations: one with a single active X (Xa) chromosome and a single inactive X (Xi) chromosome; one with two Xa chromosomes; and one with two Xi chromosomes. (A) Cells with normal XCI result from blocking factor (BF) binding to one X chromosome and the competence factor (C) binding to the other. (B) Cells with two Xa chromosomes and two Xi chromosomes result from BF and C binding to the same X chromosome. However, it is not clear how having both BF and C bound to a single X chromosome results in these two different populations of cells.

The two-factor model needs to provide more details about how BF and C bind to X chromosomes. Without knowing how BF and C bind to X chromosomes, it is unclear how this model accounts for the XTsixΔCpG:X ES cell data. In these cells, the chromosomes pair and the mutant X chromosome is always chosen for inactivation (Lee and Lu, 1999; Xu et al., 2006). With pairing, the two-factor model predicts that the BF will bind to one X chromosome and C will to bind to the other, but it is currently unknown why C would never bind to and inactivate the wild-type X chromosome, even though it contains all of the necessary binding sites.

The two-factor model also needs to explain how BF and C are produced in quantities that prevent stochastic variations in their levels from resulting in ectopic XCI in XY and X0 cells, or a lack of XCI in XX cells. Small and biologically plausible fluctuations in either BF or C concentrations could cause XY and X0 cells to have more C than BF, increasing the likelihood of ectopic XCI occurring, similar to that seen in XΔ65kb:0 and XΔ65kb:Y ES cells. Likewise, XX cells might produce only one C molecule, which is then neutralized by BF, and then fail to undergo XCI entirely. The two-factor model also needs to explain why, in XY and X0 cells, C is always neutralized by BF before it binds to the X chromosome. One would expect the transformation of C into BF to fail from time to time, resulting in ectopic XCI.

The sensing and choice model

Because XIC transgene experiments have not identified a region that could affect XCI when only a single copy was present, Augui and colleagues searched for elements other than Xist, Tsix and Xite that were crucial for XIC function. They identified a region 200-kb upstream from Xist that paired in ES cells very early after they started to differentiate. Augui et al. named this region the X-pairing region, Xpr, and showed that a single ectopic copy could pair with the endogenous region on the X chromosome (Augui et al., 2007). They also observed a significant proportion of XX+Xpr transgene cells in which more Xist accumulated around the X chromosomes prior to differentiation and at a higher frequency after differentiation than in the parental cell line without the transgene, indicating that it may have a role in initiating XCI. Furthermore, Augui et al. were unable to create an XY cell line with the Xpr transgene stably integrated, and they suggest that this is due to ectopic XCI and to selection against these cells. In order to account for their findings, Augui and colleagues developed the sensing and choice model.

In the sensing and choice model (Fig. 1C), ordered interactions are proposed to occur between the Xpr loci and the Tsix/Xite loci to regulate the opposing Xist expression patterns on the X chromosomes. In the first step of this model, called sensing (defined as counting the number of X chromosomes in the cell), the Xpr regions pair and upregulate Xist on both X chromosomes. Counting and choice are established in the second step, when Tsix/Xite loci pair and repress one of the two Xist genes. Tsix/Xite pairing is considered to be crucial for the repression of Xist, and without it, as would be the case in an XY cell that contains the Xpr transgene, Augui et al. suggest that ectopic XCI would occur.

The sensing and choice model is unique in that it takes advantage of an additional pairing step not used in any other model to explain the underlying mechanisms for XCI initiation. However, this model has difficulty explaining the results from XΔ65kb:X cells. In these cells, the Tsix/Xite locus is missing from the mutant X chromosome and, thus, cannot pair with the wild-type X chromosome. The sensing and choice model predicts that both the XΔ65kb and wild-type X chromosomes would inactivate for the same reasons that it predicts inactivation in XY+Xpr transgene cells. This is because the single Tsix/Xite locus on the wild-type X chromosome would not pair and extinguish Xist. This is in contrast to the data, which show that only the XΔ65kb chromosome accumulates Xist and inactivates, while the wild-type X chromosome remains active.

The stochastic model

Monkhorst and colleagues proposed the stochastic model (Fig. 2) in order to account for the various XCI patterns that they and others observed in cells with different autosomal ploidies (see Table 1) (Monkhorst et al., 2008). Although there are clear trends in the data that support the rule of one active X chromosome per diploid set of autosomes, diploid and tetraploid cells occasionally deviate from it by inactivating too many or too few X chromosomes. Monkhorst et al. suggest that the deviations in observed counting result from each X chromosome having an independent probability to initiate XCI within a certain timeframe.

The stochastic model starts with a trans-acting factor created by the autosomes that promotes Tsix expression (Fig. 2A). Once the cells begin to differentiate, an unknown X-linked gene produces a trans-acting factor that promotes Xist. The probability for XCI to initiate then depends on the nuclear concentration of the factors that promote Xist and Tsix transcription, through the stochastic initiation of Xist and Tsix transcription, respectively. If the concentration of the Xist-promoting factor is sufficient, cells create a chance for Xist to accumulate and initiate XCI, thereby silencing Tsix and X-linked genes in cis (including the Xist-promoting factor).

Although the stochastic model accounts for variation in XCI patterns in wild-type cells and for the data gathered from a large number of the XCI mutations, it does not account for the results from transgenic XTsixΔCpG:Y, XTsixΔCpG:0 (Lee, 2005) and XTsix IRESβgeo:Y (Ohhata et al., 2006) ES cells and mice. Experiments with these cells report that drastically reduced amounts of Tsix transcription across Xist occur. Under these conditions, the stochastic model predicts that the probability of initiating XCI would be increased, as has been found for other Tsix truncations or deletions (Luikenhuis et al., 2001; Vigneau et al., 2006). However, the results from these experiments show that Tsix may not be the only repressor of Xist because mutant X chromosomes do not initiate XCI any more often than do wild-type XY and X0 cells.

A novel feedback model

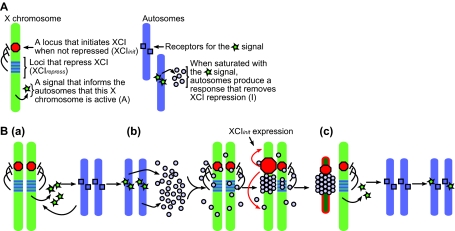

We have developed a novel model, called the feedback model, which combines aspects of older models and takes into account implications of recent XCI data. Our intention is to develop a model that can account for the results of experiments that have studied XCI in XΔXTX:X, XΔ65kb:X, XTsixΔCpG:XTsixΔCpG, XTsixΔCpG:Y, XTsixΔCpG:0 and XTsix IRESβgeo:Y ES cells and mice, because no one model has accomplished this as yet. The feedback model consists of three major components (Fig. 5): a signaling feedback loop, a mechanism for choice, and a description of X-linked loci that directly affect XCI initiation.

The feedback model of X chromosome inactivation. (A) A description of the components required for the model. (B,a) The active X chromosomes produce a trans-acting signal, A, that saturates specific sites on the autosomes. (b) Once saturated, the autosomes produce a swarm of inactivation signals, I. These signals bind to each other and to XCI inhibitors on the X chromosomes. Once all of the XCI inhibitors on an X chromosome are sufficiently bound by I, the XCI initiator induces inactivation. (c) With only one active X chromosome producing A, the autosomes are no longer saturated with A and stop producing I.

A signaling feedback loop

The first component of the model is a signaling feedback loop between the autosomes and the X chromosomes, which allows the cell to iteratively inactivate the appropriate number of X chromosomes. Lyon first described this type of feedback loop in 1971 (Lyon, 1971; Lyon, 1972). It begins with X chromosomes producing a trans-acting signal that indicates that they are active, called A (Fig. 5A,B part a). After receptors or binding sites on the autosomes are saturated by A, they respond by producing transacting signals, I, that promote the inactivation of one of the two X chromosomes (Fig. 5A,B parts b,c). Once one X chromosome is inactivated, the level of A is reduced by half and can no longer saturate the binding sites on the autosomes, shutting off the production of I and leaving the remaining X chromosome in an active state (Fig. 5B part c). Evidence for the existence of the I signal comes from the observation that autosomal ploidy affects counting. Furthermore, studies of aneuploid cells in humans indicate that the autosomal component in any XCI model is likely to be derived from more than one type of autosome (Migeon et al., 2008). This implies that A may be made of several factors or non-coding RNAs.

Both Monkhorst et al. and Augui et al. have provided indirect evidence for the A signal. Monkhorst et al. observed the speed at which XCI takes place correlates with the number of X chromosomes in a cell, and that there is a decrease in the probability of XCI occurring in cells with fewer X chromosomes (Monkhorst et al., 2008). Both observations could be interpreted as being the result of modulating the concentration of A. With more X chromosomes, the concentration of A is increased, which in turn will ensure that the autosomes will be saturated by this signal and produce I; with fewer X chromosomes, the production of I is lowered because of a reduction in A. Additionally, when the Xpr is inserted into an autosome as an ectopic single-copy transgene, it can increase the rate of XCI and cause ectopic increases in Xist expression and Xist accumulation on the X chromosome in male cells (Augui et al., 2007). These hallmarks of random XCI indicate that two copies of this region can promote inactivation in a way that is postulated by the A signal.

A mechanism for choice

The second component uses Nicodemi and Prisco's theory (Nicodemi and Prisco, 2007a; Nicodemi and Prisco, 2007b) to determine how I binds to one of two X chromosomes. However, instead of a diffuse signal that forms a compound BF, we propose that it induces XCI. Thus, I begins as a swarm of molecules that can bind to each other and to key sites on the X chromosomes (Fig. 5B). By pairing together, the X chromosomes concentrate I, allowing a critical mass to bind to a single X chromosome in a sufficiently short amount of time. Once a binding threshold is met, cooperative-like binding causes all of the remaining I to bind to the same X chromosome. The result is that one X chromosome binds all of the I signal and the other does not bind any of it.

X-linked loci that directly influence XCI initiation

The third component of the feedback model consists of specifying, in general terms, at least one locus within the XIC that initiates X inactivation, XCIinit, and several loci that repress the activity of the XCIinit locus, XCIrepress (Fig. 5A). One candidate for the XCIinit locus is Xist because it is expressed early during XCI initiation and coats the entire X chromosome that becomes inactivated. Reasonable candidate XCIrepress loci are both Tsix and Xite (Lee, 2005; Lee et al., 1999a; Lee and Lu, 1999; Ogawa and Lee, 2003; Sado et al., 2001). In XY ES cells and male mice, deleting Tsix (Lee and Lu, 1999) or Xite (Ogawa and Lee, 2003) does not result in XCI; however, the single X chromosome undergoes XCI when both Tsix and Xite are removed (Clerc and Avner, 1998). Furthermore, the overexpression of Tsix (Luikenhuis et al., 2001; Stavropoulos et al., 2005) inhibits XCI, as do multicopy transgenes that contain Tsix and Xite (Lee, 2005).

In the feedback model, an X chromosome inactivates when the effects of all the XCIrepress loci over the XCIinit locus are removed (Fig. 6). This can be due to XCIrepress loci being bound by the I signal, or to deletions that remove XCIrepress loci or other mutations that prevent XCIrepress from functioning normally. Because the model assumes that there are multiple XCIrepress loci in each XIC, the deletion or mutation of only one will predispose that X chromosome to inactivation, as it would require less I signal to inhibit the remaining XCIrepress loci, but would not cause ectopic XCI. The deletion or mutation of all XCIrepress loci in a single XIC would ensure the inactivation of that X chromosome, even in cells with only one X chromosome.

Three different paths to X inactivation. (A) In a normal X chromosome, all of the XCIrepress loci must be turned off by I. (B) In a mutant X chromosome where some of the XCIrepress loci have been removed, only a small amount of I is required to initiate XCI. Because these chromosomes have a lower threshold to overcome before initiating XCI, there is a higher probability that they will inactivate. (C) In a mutant X chromosome where all of the XCIrepress loci have been removed, XCI will initiate without any I.

The feedback loop between X chromosomes and autosomes can reproduce the counting that takes place in normal cells, and in cells with unusual numbers of X chromosomes and autosome ploidy. Male cells, for example, with only one X chromosome cannot create enough of the initial A signal to invoke inactivation. In diploid cells with more than two X chromosomes, the signaling feedback loop inactivates all but one X chromosome because the autosomes would continue to be saturated with A until only one X chromosome remained active. In polyploid cells, the additional autosomes would require more A before producing I in sufficient quantities to inactivate an X chromosome, thereby allowing more Xs to remain active. Thus, the feedback model can reproduce the counting that takes place in normal, X chromosome aneuploid and polyploid cells.

The feedback model explains the results from the XΔ65kb, XΔ65kb+16kb, and XΔ65kb+37kb deletions. The XΔ65kb deletion, which removes both Tsix and Xite and causes the mutant X chromosome to inactivate in all cells, potentially removes all of the XCIrepress loci. Thus, one would expect the XCIinit locus to act in an uninhibited way and to inactivate the X chromosome, regardless of the number of other active or inactive X chromosomes present in the cell (Fig. 6). The XΔ65kb+16kb deletion, which removes only one XCIrepress locus, Xite, but not Tsix, does not cause a failure in counting, but does cause the mutant X chromosome to inactivate in XΔ65kb+16kb:X ES cells. Under the feedback model, removing only one XCIrepress locus from the mutant X chromosome would only skew choice towards inactivating the mutant, it would leave counting unchanged (Fig. 6). This is because at least one other XCIrepress locus would inhibit ectopic XCI, allowing for proper counting, but the reduction of overall repression would limit the amount of the I signal required to inactivate the mutant X chromosome. The XΔ65kb+37kb deletion, which does not remove either Tsix or Xite from the mutant X chromosome, does not disrupt counting or choice. The feedback model would interpret these results as suggesting that the XΔ65kb+37kb deletion leaves all XCIrepress loci intact.

The feedback model can also explain the chaotic counting that is observed in XTsixΔCpG:XTsixΔCpG ES cells. In mutant cells in which both X chromosomes remain active, neither X is bound by sufficient quantities of the I signal to inactivate because the X chromosomes did not pair. Cells with one or two inactive X chromosomes result from the reduction of Tsix transcription across Xist. Because Tsix transcription can repress Xist transcription, it is one of several potential XCIrepress loci. With one fewer XCIrepress locus, XTsixΔCpG chromosomes would require less I to initiate inactivation than would wild-type X chromosomes. In these cases, smaller clusters of I could bind to one or both Xs, even in conditions that prevented the formation of a single, large macromolecule.

The results from the XΔXTX deletion are also easily understood with the feedback model. By removing Xist, and thus the XCIinit locus, from an X chromosome, the mutant would not inactivate, but would still be able to produce the A signal. Thus, normal counting should take place in heterozygous cells, but choice should be skewed; the mutant X chromosome should remain active in all cells.

It is possible that the Xpr pairing is the signal to synthesize A, and that the gene that encodes A is in this region. However, it is more likely that A is the product of more than one locus. Although the locus in the Xpr may be relatively dominant, because a single ectopic copy is sufficient to drive XCI in XY cells, transgenes that include Xist (Herzing et al., 1997; Lee et al., 1999b; Lee et al., 1996) but that do not include the Xpr can also induce ectopic XCI, but multiple copies need to be present. Perhaps these transgenes contain weaker A-producing loci that need to be present in sufficient numbers in order to drive XCI without an additional Xpr region. Thus, given a large number of Xist-containing transgenes, an XY cell might generate enough of the A signal to generate the I signal. The cell's response to the I signal, however, would depend on the structure of the transgene. Transgenes that also contain XCIrepress loci would probably bind the I signal because of the large number of binding sites they would provide. This idea is supported by Lee's transgene experiments with a multicopy transgene that contains Tsix and Xist, which prevented XCI in XX cells (Lee, 2005). Transgenes that contain Xist but not XCIrepress loci might not bind the I signal, thereby allowing the I signal to bind to the wild-type X chromosome at levels that depend upon the presence or absence of Tsix/Xist pairing: with pairing, one would expect a high level of binding; without pairing, one would expect a relatively low level of binding.

Limitations of the feedback model

It is currently unclear if researchers should favor the results from XTsixΔCpG:Y, XTsixΔCpG:0 and XTsix IRESβgeo:Y ES cells and mice over those derived from XTsix stop:Y and XTsixΔmajor:Y ES cells. For all of these mutant ES cells and mice, researchers have reported drastically reduced levels of Tsix expression across Xist. The effects of this reduction, however, are different in the two groups of cells. In the first group, Xist is not upregulated and the cells do not show ectopic XCI. In the second group, Xist is upregulated and the cells inactivate the single X chromosome. Until researchers can determine why these cells initiate XCI differently, it will be impossible to know whether one should use the feedback model or the stochastic model to interpret these data.

Conclusions

Since random XCI was first proposed in 1961 as the means for ensuring that only one X chromosome is active per diploid set of autosomes, scientists have used models to try to understand their experimental results. Here, we present the feedback model, which was designed to maximize the number of experimental results that it could account for. Because it incorporates Lyon's inter-chromosomal feedback signaling, we hope that there will be a renewed interest in searching for trans-acting signals that might originate from the X chromosomes and that might be received by autosomes prior to the initiation of XCI. Our model also suggests that multiple loci are involved in repressing the initiation of XCI, and not a single locus. This concept allows the model to reconcile data from different laboratories that would otherwise be contradictory. It is our hope that the feedback model provides a clearer picture of how X chromosome mutation and deletion data should be interpreted, and that it will encourage researchers to develop hypotheses for future experiments.

Notes

The authors would like to thank A. Fedoriw and M. Calabrese for thoughtful feedback and suggestions. T.M. is supported by the NIH and J.S. is supported by the NIEHS. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

References

- Augui, S., Filion, G. J., Huart, S., Nora, E., Guggiari, M., Maresca, M., Stewart, A. F. and Heard, E. (2007). Sensing X chromosome pairs before X inactivation via a novel X-pairing region of the Xic. Science 318, 1632-1636. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Bacher, C. P., Guggiari, M., Brors, B., Augui, S., Clerc, P., Avner, P., Eils, R. and Heard, E. (2006). Transient colocalization of X-inactivation centres accompanies the initiation of X inactivation. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 293-299. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Borsani, G., Tonlorenzi, R., Simmler, M. C., Dandolo, L., Arnaud, D., Capra, V., Grompe, M., Pizzuti, A., Muzny, D., Lawrence, C. et al. (1991). Characterization of a murine gene expressed from the inactive X chromosome. Nature 351, 325-329. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Brockdorff, N., Ashworth, A., Kay, G. F., Cooper, P., Smith, S., McCabe, V. M., Norris, D. P., Penny, G. D., Patel, D. and Rastan, S. (1991). Conservation of position and exclusive expression of mouse Xist from the inactive X chromosome. Nature 351, 329-331. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C. J., Ballabio, A., Rupert, J. L., Lafreniere, R. G., Grompe, M., Tonlorenzi, R. and Willard, H. F. (1991a). A gene from the region of the human X inactivation centre is expressed exclusively from the inactive X chromosome. Nature 349, 38-44. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C. J., Lafreniere, R. G., Powers, V. E., Sebastio, G., Ballabio, A., Pettigrew, A. L., Ledbetter, D. H., Levy, E., Craig, I. W. and Willard, H. F. (1991b). Localization of the X inactivation centre on the human X chromosome in Xq13. Nature 349, 82-84. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Chureau, C., Prissette, M., Bourdet, A., Barbe, V., Cattolico, L., Jones, L., Eggen, A., Avner, P. and Duret, L. (2002). Comparative sequence analysis of the X-inactivation center region in mouse, human, and bovine. Genome Res. 12, 894-908. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Chuva de Sousa Lopes, S. M., Hayashi, K., Shovlin, T. C., Mifsud, W., Surani, M. A. and McLaren, A. (2008). X chromosome activity in mouse XX primordial germ cells. PLoS Genet. 4, e30. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Clerc, P. and Avner, P. (1998). Role of the region 3′ to Xist exon 6 in the counting process of X-chromosome inactivation. Nat. Genet. 19, 249-253. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Endo, S., Takagi, N. and Sasaki, M. (1982). The late-replicating X chromosome in digynous mouse triploid embryos. Dev. Genet. 3, 165-176. [Google Scholar]

- Gartler, S. M. and Riggs, A. D. (1983). Mammalian X-chromosome inactivation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 17, 155-190. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Gartler, S. M., Varadarajan, K. R., Luo, P., Norwood, T. H., Canfield, T. K. and Hansen, R. S. (2006). Abnormal X: autosome ratio, but normal X chromosome inactivation in human triploid cultures. BMC Genet. 7, 41. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Grumbach, M. M., Morishima, A. and Taylor, J. H. (1963). Human sex chromosome abnormalities in relation to DNA replication and heterochromatinization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 49, 581-589. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Heard, E., Kress, C., Mongelard, F., Courtier, B., Rougeulle, C., Ashworth, A., Vourc'h, C., Babinet, C. and Avner, P. (1996). Transgenic mice carrying an Xist-containing YAC. Hum. Mol. Genet. 5, 441-450. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Heard, E., Mongelard, F., Arnaud, D. and Avner, P. (1999). Xist yeast artificial chromosome transgenes function as X-inactivation centers only in multicopy arrays and not as single copies. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 3156-3166. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Herzing, L. B., Romer, J. T., Horn, J. M. and Ashworth, A. (1997). Xist has properties of the X-chromosome inactivation centre. Nature 386, 272-275. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kratzer, P. G. and Chapman, V. M. (1981). X chromosome reactivation in oocytes of Mus caroli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78, 3093-3097. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. T. (2005). Regulation of X-chromosome counting by Tsix and Xite sequences. Science 309, 768-771. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. T. and Lu, N. (1999). Targeted mutagenesis of Tsix leads to nonrandom X inactivation. Cell 99, 47-57. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. T., Strauss, W. M., Dausman, J. A. and Jaenisch, R. (1996). A 450 kb transgene displays properties of the mammalian X-inactivation center. Cell 86, 83-94. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. T., Davidow, L. S. and Warshawsky, D. (1999a). Tsix, a gene antisense to Xist at the X-inactivation centre. Nat. Genet. 21, 400-404. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. T., Lu, N. and Han, Y. (1999b). Genetic analysis of the mouse X inactivation center defines an 80-kb multifunction domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 3836-3841. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Luikenhuis, S., Wutz, A. and Jaenisch, R. (2001). Antisense transcription through the Xist locus mediates Tsix function in embryonic stem cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 8512-8520. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, M. F. (1961). Gene action in the X-chromosome of the mouse (Mus musculus L.). Nature 190, 372-373. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, M. F. (1971). Possible mechanisms of X chromosome inactivation. Nature New Biol. 232, 229-232. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, M. F. (1972). X-chromosome inactivation and developmental patterns in mammals. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 47, 1-35. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Mak, W., Nesterova, T. B., de Napoles, M., Appanah, R., Yamanaka, S., Otte, A. P. and Brockdorff, N. (2004). Reactivation of the paternal X chromosome in early mouse embryos. Science 303, 666-669. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Marahrens, Y., Panning, B., Dausman, J., Strauss, W. and Jaenisch, R. (1997). Xist-deficient mice are defective in dosage compensation but not spermatogenesis. Genes Dev. 11, 156-166. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Migeon, B. R., Pappas, K., Stetten, G., Trunca, C. and Jacobs, P. A. (2008). X inactivation in triploidy and trisomy: the search for autosomal transfactors that choose the active X. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 16, 153-162. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Monk, M. and McLaren, A. (1981). X-chromosome activity in foetal germ cells of the mouse. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 63, 75-84. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Monkhorst, K., Jonkers, I., Rentmeester, E., Grosveld, F. and Gribnau, J. (2008). X inactivation counting and choice is a stochastic process: evidence for involvement of an X-linked activator. Cell 132, 410-421. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Morey, C., Arnaud, D., Avner, P. and Clerc, P. (2001). Tsix-mediated repression of Xist accumulation is not sufficient for normal random X inactivation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 1403-1411. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Morey, C., Navarro, P., Debrand, E., Avner, P., Rougeulle, C. and Clerc, P. (2004). The region 3′ to Xist mediates X chromosome counting and H3 Lys-4 dimethylation within the Xist gene. EMBO J. 23, 594-604. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Nesterova, T. B., Johnston, C. M., Appanah, R., Newall, A. E., Godwin, J., Alexiou, M. and Brockdorff, N. (2003). Skewing X chromosome choice by modulating sense transcription across the Xist locus. Genes Dev. 17, 2177-2190. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Nicodemi, M. and Prisco, A. (2007a). Self-assembly and DNA binding of the blocking factor in X chromosome inactivation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 3, e210. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Nicodemi, M. and Prisco, A. (2007b). Symmetry-breaking model for X-chromosome inactivation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 108104. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, Y. and Lee, J. T. (2003). Xite, X-inactivation intergenic transcription elements that regulate the probability of choice. Mol. Cell 11, 731-743. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ohhata, T., Hoki, Y., Sasaki, H. and Sado, T. (2006). Tsix-deficient X chromosome does not undergo inactivation in the embryonic lineage in males: implications for Tsix-independent silencing of Xist. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 113, 345-349. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, I., Otte, A. P., Allis, C. D., Reinberg, D. and Heard, E. (2004). Epigenetic dynamics of imprinted X inactivation during early mouse development. Science 303, 644-649. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Panning, B., Dausman, J. and Jaenisch, R. (1997). X chromosome inactivation is mediated by Xist RNA stabilization. Cell 90, 907-916. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Penny, G. D., Kay, G. F., Sheardown, S. A., Rastan, S. and Brockdorff, N. (1996). Requirement for Xist in X chromosome inactivation. Nature 379, 131-137. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Rastan, S. (1983). Non-random X-chromosome inactivation in mouse X-autosome translocation embryos-location of the inactivation centre. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 78, 1-22. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, L. B. (1963). Mammalian X-chromosome action: inactivation limited in spread and region of origin. Science 140, 976-978. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sado, T., Wang, Z., Sasaki, H. and Li, E. (2001). Regulation of imprinted X-chromosome inactivation in mice by Tsix. Development 128, 1275-1286. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sheardown, S. A., Duthie, S. M., Johnston, C. M., Newall, A. E., Formstone, E. J., Arkell, R. M., Nesterova, T. B., Alghisi, G. C., Rastan, S. and Brockdorff, N. (1997). Stabilization of Xist RNA mediates initiation of X chromosome inactivation. Cell 91, 99-107. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata, S. and Lee, J. T. (2004). Tsix transcription-versus RNA-based mechanisms in Xist repression and epigenetic choice. Curr. Biol. 14, 1747-1754. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Speirs, S., Cross, J. M. and Kaufman, M. H. (1990). The pattern of X-chromosome inactivation in the embryonic and extra-embryonic tissues of postimplantation digynic triploid LT/Sv strain mouse embryos. Genet. Res. 56, 107-114. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Stavropoulos, N., Rowntree, R. K. and Lee, J. T. (2005). Identification of developmentally specific enhancers for Tsix in the regulation of X chromosome inactivation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 2757-2769. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi, N., Sugimoto, M., Yamaguchi, S., Ito, M., Tan, S. S. and Okabe, M. (2002). Nonrandom X chromosome inactivation in mouse embryos carrying Searle's T(X;16)16H translocation visualized using X-linked LACZ and GFP transgenes. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 99, 52-58. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C. L., Rowntree, R. K., Cohen, D. E. and Lee, J. T. (2008). Higher order chromatin structure at the X-inactivation center via looping DNA. Dev. Biol. 319, 416-425. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Vigneau, S., Augui, S., Navarro, P., Avner, P. and Clerc, P. (2006). An essential role for the DXPas34 tandem repeat and Tsix transcription in the counting process of X chromosome inactivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 7390-7395. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Webb, S., de Vries, T. J. and Kaufman, M. H. (1992). The differential staining pattern of the X chromosome in the embryonic and extraembryonic tissues of postimplantation homozygous tetraploid mouse embryos. Genet. Res. 59, 205-214. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, N., Donohoe, M. E., Silva, S. S. and Lee, J. T. (2007). Evidence that homologous X-chromosome pairing requires transcription and Ctcf protein. Nat. Genet. 39, 1390-1396. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, N., Tsai, C. L. and Lee, J. T. (2006). Transient homologous chromosome pairing marks the onset of X inactivation. Science 311, 1149-1152. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Articles from Development (Cambridge, England) are provided here courtesy of Company of Biologists

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.025908

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://dev.biologists.org/content/develop/136/1/1.full.pdf

Free to read at dev.biologists.org

http://dev.biologists.org/cgi/content/abstract/136/1/1

Free after 6 months at dev.biologists.org

http://dev.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/136/1/1

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1242/dev.025908

Article citations

A Comparative Analysis of Mouse Imprinted and Random X-Chromosome Inactivation.

Epigenomes, 8(1):8, 10 Feb 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38390899 | PMCID: PMC10885068

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Targeting RNA with small molecules: lessons learned from Xist RNA.

RNA, 29(4):463-472, 01 Feb 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 36725318 | PMCID: PMC10019374

Jpx RNA regulates CTCF anchor site selection and formation of chromosome loops.

Cell, 184(25):6157-6173.e24, 01 Dec 2021

Cited by: 37 articles | PMID: 34856126 | PMCID: PMC8671370

Selective Xi reactivation and alternative methods to restore MECP2 function in Rett syndrome.

Trends Genet, 38(9):920-943, 02 Mar 2022

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 35248405 | PMCID: PMC9915138

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

RIF1 and KAP1 differentially regulate the choice of inactive versus active X chromosomes.

EMBO J, 40(24):e105862, 17 Nov 2021

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 34786738 | PMCID: PMC8672179

Go to all (62) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Developmental regulation of X-chromosome inactivation.

Semin Cell Dev Biol, 56:88-99, 22 Apr 2016

Cited by: 25 articles | PMID: 27112543

Review

X inactivation Xplained.

Curr Opin Genet Dev, 17(5):387-393, 14 Sep 2007

Cited by: 100 articles | PMID: 17869504

Review

Escape Artists of the X Chromosome.

Trends Genet, 32(6):348-359, 18 Apr 2016

Cited by: 93 articles | PMID: 27103486

Review

X-changing information on X inactivation.

Exp Cell Res, 316(5):679-687, 18 Jan 2010

Cited by: 32 articles | PMID: 20083102

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCRR NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: U42 RR014817-09

Grant ID: U42 RR014817

NICHD NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: R37 HD024462

Grant ID: R37 HD024462-21