Abstract

Free full text

Postreceptor insulin resistance contributes to human dyslipidemia and hepatic steatosis

Associated Data

Abstract

Metabolic dyslipidemia is characterized by high circulating triglyceride (TG) and low HDL cholesterol levels and is frequently accompanied by hepatic steatosis. Increased hepatic lipogenesis contributes to both of these problems. Because insulin fails to suppress gluconeogenesis but continues to stimulate lipogenesis in both obese and lipodystrophic insulin-resistant mice, it has been proposed that a selective postreceptor defect in hepatic insulin action is central to the pathogenesis of fatty liver and hypertriglyceridemia in these mice. Here we show that humans with generalized insulin resistance caused by either mutations in the insulin receptor gene or inhibitory antibodies specific for the insulin receptor uniformly exhibited low serum TG and normal HDL cholesterol levels. This was due at least in part to surprisingly low rates of de novo lipogenesis and was associated with low liver fat content and the production of TG-depleted VLDL cholesterol particles. In contrast, humans with a selective postreceptor defect in AKT2 manifest increased lipogenesis, elevated liver fat content, TG-enriched VLDL, hypertriglyceridemia, and low HDL cholesterol levels. People with lipodystrophy, a disorder characterized by particularly severe insulin resistance and dyslipidemia, demonstrated similar abnormalities. Collectively these data from humans with molecularly characterized forms of insulin resistance suggest that partial postreceptor hepatic insulin resistance is a key element in the development of metabolic dyslipidemia and hepatic steatosis.

Introduction

The burgeoning pandemic of obesity is a critical health care concern because of the vast associated burden of premature morbidity and mortality. This is predominantly due to accelerated atherosclerosis, although the long-term consequences of hyperglycemia also exact a considerable toll in the subset of obese patients who develop diabetes mellitus. A key factor in the development of atherosclerosis in this setting is a characteristic pattern of dyslipidemia including high serum triglyceride (TG) and low HDL cholesterol levels, a pernicious combination that we refer to as “metabolic dyslipidemia.” This is tightly correlated both with hyperinsulinemia (even in the absence of diabetes; ref. 1) and nonalcoholic fatty liver (2). Teasing out the pathogenic sequence linking these phenomena is of critical importance in rational efforts to intervene against the harmful consequences of obesity.

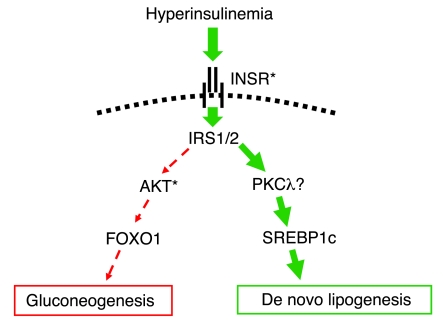

Hyperinsulinemia in the context of normal blood glucose is often taken to be synonymous with “insulin resistance.” However, while this is true with respect to glucose homeostasis, the possibility of partial insulin resistance selectively affecting only some of insulin’s pleiotropic effects has long been mooted (3, 4). Growing evidence from murine models now supports this idea. Specifically, the observation that insulin-resistant diabetic mice exhibit impaired insulin-stimulated suppression of hepatic gluconeogenesis but enhanced insulin-stimulated hepatic lipogenesis prompted Brown and Goldstein to propose a model featuring selective postreceptor hepatic insulin resistance (5, 6) (Figure (Figure1).1). According to this model, the canonical insulin signaling pathway through IRS/PI3K/protein kinase B/forkhead box O transcription factor 1 (IRS/PI3K/AKT/FOXO1) is selectively downregulated in the presence of hyperinsulinemia. In contrast, a parallel pathway linking activation of the insulin receptor to transcriptional upregulation of the critical lipogenic transcription factor SREBP1c remains fully functional and thus mediates enhanced lipogenesis in the presence of hyperinsulinemia. The molecular components of this signaling pathway have yet to be fully elucidated. Increased liver fat due to activation of the INSR-SREBP1c pathway is in turn associated with excess hepatic production of large TG-rich VLDL particles. Cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) exchanges cholesterol esters from HDL and LDL particles with TGs from VLDL, lowering HDL cholesterol levels and facilitating the accumulation of atherogenic small dense LDL particles (7).

In insulin-resistant states in mice, the ability of insulin to suppress hepatic gluconeogenesis is impaired (dashed red arrows), whereas insulin-stimulated de novo lipogenesis is increased (solid green arrows) (5). Only selected signaling intermediaries are shown. INSR, insulin receptor. Asterisks indicate signaling components in which human genetic defects have been reported to date.

The hypothesis that the prevalent form of insulin resistance is a specific and incomplete intracellular defect is supported in part by recent observations in liver insulin receptor knockout (LIRKO) mice (8). These animals manifest low liver and plasma TG levels despite being hyperglycemic and hyperinsulinemic, a finding in keeping with genetic deficiency of the first step in insulin signaling, which is common to the pathways leading to AKT and SREBP. However, despite low plasma TG levels, the LIRKO mice exhibited exaggerated atherosclerosis when put on an atherogenic diet, which was attributed to a shift toward cholesterol-rich, apoB-containing lipoproteins. Murine carbohydrate and lipid metabolism differs in several important respects from that of humans, with, for example, markedly different lipoprotein profiles and patterns of tissue-specific insulin-stimulated glucose uptake, complicating precise extrapolation from mouse models of metabolic disease to humans. We thus set out to test the hypothesis of selective postreceptor insulin resistance (referred to herein as “partial insulin resistance”) in humans with metabolic dyslipidemia by characterizing lipid metabolism in patients with primary defects in the insulin receptor (referred to herein as “generalized insulin resistance”) or in the downstream protein kinase AKT2 and comparing their lipid metabolism with that of people with primary lipodystrophy and severe dyslipidemia.

Results

Biochemical characteristics of patients with severe insulin resistance due to insulin receptor defects.

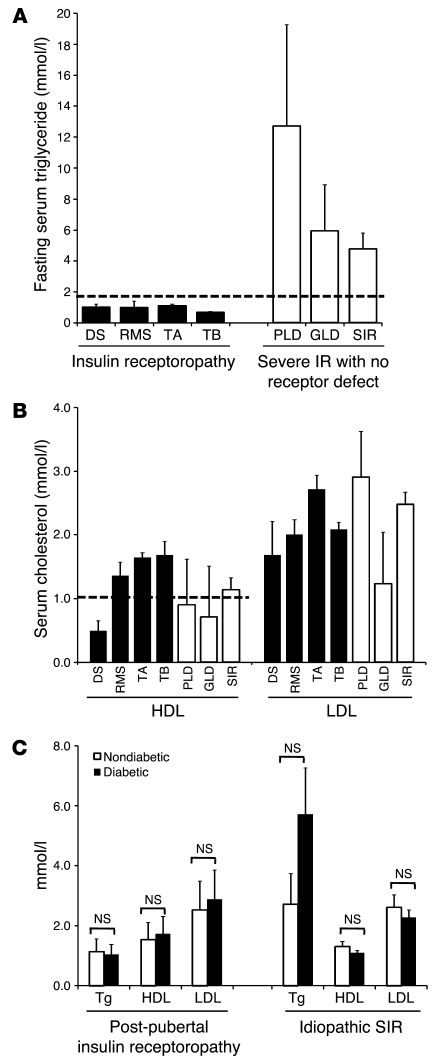

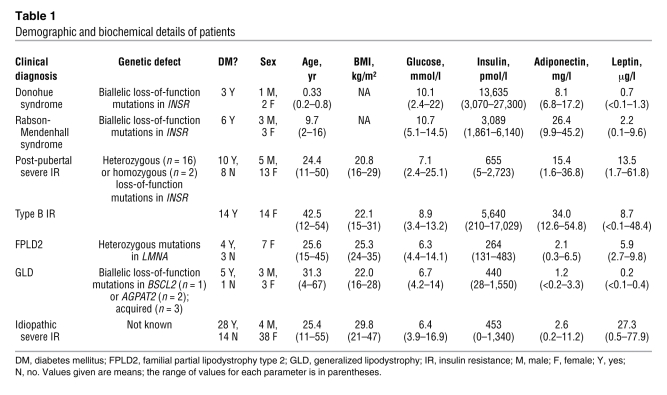

We studied 41 subjects with severe insulin resistance due to signaling defects at the level of the insulin receptor, and compared them with patients with severe insulin resistance associated with lipodystrophy (n = 13), or with severe insulin resistance of undefined molecular etiology (n = 42) (Table (Table1).1). Patients with genetic defects in the insulin receptor included 3 patients with Donohue syndrome and 6 with Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome, both resulting from homozygous or compound heterozygous INSR mutations, and 18 patients with severe insulin resistance presenting peripubertally or in adult life, predominantly caused by dominant-negative heterozygous INSR mutations. Patients with acquired insulin receptor defects (n = 14) all had type B insulin resistance due to inhibitory insulin receptor antibodies. As expected, patients with lipodystrophy or with severe insulin resistance of undefined etiology had an exaggerated form of the highly prevalent metabolic dyslipidemia, with high TG and low HDL cholesterol levels. However, in keeping with similar observations by Musso et al. (9), patients with either genetic or acquired insulin receptoropathy had strikingly normal lipid profiles despite extreme hyperinsulinemia (Table (Table11 and Figure Figure2,2, A and B). Furthermore, the presence of diabetes did not appear to perturb the normal lipid profile of postpubertal receptoropathy patients (Figure (Figure2C).2C). All patients with Donohue or Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome were overtly diabetic at presentation.

(A) Fasting serum TG and (B) cholesterol concentrations in patients with insulin receptoropathy, lipodystrophy, or idiopathic severe insulin resistance (IR). (C) Comparison of lipid profiles between diabetic and nondiabetic subjects with either genetic INSR defects presenting at or after puberty or severe insulin resistance of unknown, but likely genetic, etiology. No significant differences were detected by ANOVA. DS, Donohue syndrome; RMS, Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome; TA, post-pubertal severe insulin resistance due to genetic insulin receptor defects; TB, type B insulin resistance; PLD, familial partial lipodystrophy due to LMNA mutations; GLD, generalized lipodystrophy; SIR, severe insulin resistance. Dashed lines represent World Health Organization thresholds for the diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome for TG (>1.7 mmol/l) and HDL cholesterol (<1.0 mmol/l for females). Error bars represent SEM.

Table 1

Demographic and biochemical details of patients

Oral glucose tolerance, liver fat assessment, and de novo lipogenesis in patients with insulin receptor mutations.

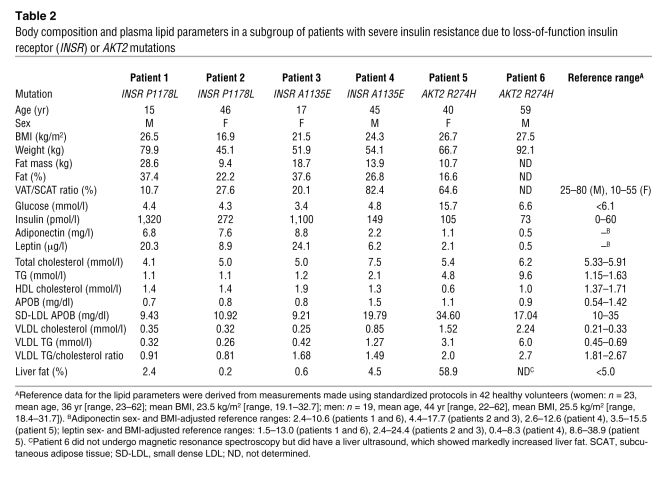

To explore further the mechanistic basis for the protection from dyslipidemia of patients with insulin receptoropathy, we selected 4 patients with genetic insulin receptor defects for further study. All 4 had severe insulin resistance due to heterozygosity for well-characterized dominant-negative missense mutations in the β subunit of the insulin receptor: P1178L (10–12) in a mother and son and A1135E (13) in a father and daughter (Table (Table2).2). Of specific note, none of these patients had yet decompensated to diabetes. Furthermore, although 3 of the 4 patients studied in detail had inappropriately preserved adiponectin levels, a hallmark of insulin receptor dysfunction (14), in these 3 patients the adiponectin levels were within the normal range derived from a non-diabetic volunteer population (Table (Table2).2). Total body fat and abdominal fat distribution were similar to previously reported reference ranges (15–17) (Table (Table2). 2).

Table 2

Body composition and plasma lipid parameters in a subgroup of patients with severe insulin resistance due to loss-of-function insulin receptor (INSR) or AKT2 mutations

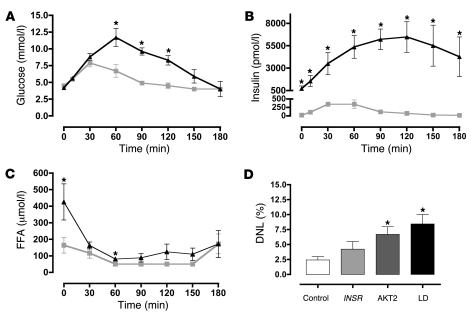

Insulin sensitivity was evaluated using a 3-hour oral glucose tolerance test. Whereas fasting glucose values were within the normal range, post-challenge values were significantly increased (1.5-fold increase in area under the curve) (Figure (Figure3A).3A). Insulin levels were massively increased throughout the test (~30-fold increase in area under the curve) (Figure (Figure3B).3B). Fasting FFA levels were higher than those of controls (P < 0.05) (although still within the conventional reference ranges of 280–920 μmol/l), and following glucose ingestion, FFA suppression was mildly impaired (Figure (Figure3C).3C). The total area under the FFA curve for the insulin receptor mutation carriers was 1.78-fold greater than that in healthy controls (P < 0.05). Despite these significant increases in glucose, insulin, and FFA levels, liver fat measurements were within normal limits (Table (Table2)2) and hepatic de novo lipogenesis was not significantly increased relative to healthy controls (Figure (Figure3D).3D). Analysis of the VLDL particle composition also revealed low VLDL TG/cholesterol ratios in all 4 patients (Table (Table2). 2).

(A–C) Plasma glucose (A), insulin (B), and non-esterified FFAs (C) before and after a 75-g oral glucose challenge in patients (n = 4) with type A insulin resistance due to insulin receptor mutations (filled triangles) and in healthy controls (n = 6; gray squares). (D) De novo lipogenesis (DNL) in healthy controls (n = 6; white bar) and in patients with severe insulin resistance due to mutations in the insulin receptor (INSR; n = 4; light gray bar), AKT2 (n = 2; dark gray bar) or partial lipodystrophy (LD; n = 3; black bar). All data represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus control.

Postreceptor insulin resistance due to AKT2 mutations.

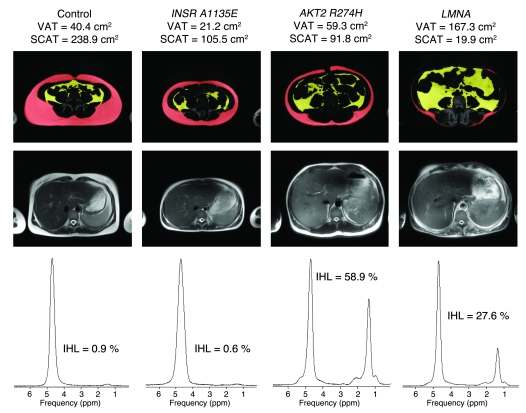

In contrast to the normal lipid parameters noted in patients with primary insulin receptor defects (generalized insulin resistance), 2 patients with severe insulin resistance due to a dominant-negative (R274H) AKT2 mutation (18) were found to manifest typical metabolic dyslipidemia with elevated fasting TGs, high VLDL TG/cholesterol ratios, low HDL cholesterol levels, and high small dense LDL levels (Table (Table2).2). De novo lipogenesis (Figure (Figure1D)1D) and liver fat (Figure (Figure44 and Table Table2)2) were also significantly elevated in these subjects.

Representative abdominal fat distribution (at the L4 vertebral level) (top row), together with T2-weighted HASTE transaxial images of the liver (middle row), and the corresponding liver fat spectra (bottom row) from 4 women. The control volunteer was a 38-year-old female (BMI, 24.2 kg/m2), INSR A1135E was a 17-year-old female (BMI, 21.5 kg/m2; patient 3 in Table Table2),2), AKT2 R274H was a 40-year-old female (BMI, 26.7 kg/m2; patient 5 in Table Table2),2), and LMNA was a 45-year-old woman (BMI, 25.0 kg/m2 with FPLD2; she was a compound heterozygote for LMNA S583L and T528M; ref. 40). VAT is shown in yellow. IHL, intrahepatic lipid as determined by magnetic resonance spectroscopy; SCAT, subcutaneous adipose tissue (red).

Insulin resistance resulting from lipodystrophy.

Fatty liver and metabolic dyslipidemia are common problems in patients with lipodystrophy (19). We studied in further detail 3 patients with different forms of partial lipodystrophy, all of whom manifested hypertriglyceridemia, low HDL cholesterol (data from these 3 subjects is included in the analysis reported in Table Table1),1), and fatty liver (Figure (Figure4).4). Importantly, fasting FFA levels were within normal limits in all 3 patients (data not shown), but de novo lipogenesis was significantly increased (Figure (Figure3D). 3D).

Discussion

Despite extreme insulin resistance, patients with primary defects at the level of the insulin receptor (generalized insulin resistance) did not manifest metabolic dyslipidemia. This was true in people with loss-of-function mutations in the insulin receptor and in those with severe insulin resistance due to inhibitory insulin receptor antibodies, effectively representing a naturally occurring model of acquired and reversible insulin receptor dysfunction in adult life. These data are consistent with similar observations by Musso et al. in a smaller number of patients (9). It even appears to be true in those patients in whom insulin receptor–mediated insulin resistance progresses to overt type 2 diabetes mellitus, where one might expect hyperglycemia to promote lipogenesis via carbohydrate response element binding protein (CHREBP) (20). Despite higher plasma FFA and glucose levels and massively increased plasma insulin levels, liver fat measurements were normal in the patients we studied with insulin receptor mutations. Theoretically, this could be a result of either reduced hepatic lipogenesis or increased oxidation or excretion of liver TGs. While it is not currently possible to measure hepatic fat oxidation directly in vivo in humans, plasma ketone levels were unremarkable in these patients (data not shown), and they are not prone to develop ketoacidosis in the prediabetic state. We did not measure VLDL turnover but did document surprisingly normal rates of de novo lipogenesis and low VLDL TG/cholesterol ratios in 4 patients with insulin receptor mutations. Although the data (Figure (Figure3D)3D) suggest that de novo lipogenesis may be modestly increased in patients with INSR mutations, the magnitude of this change (~2-fold) is still remarkably small in comparison with the huge increases in plasma insulin (~30-fold). A small increase in hepatic lipogenesis is consistent with a degree of residual insulin signaling capacity of the mutant insulin receptors. Collectively, these observations suggest that reduced liver fat synthesis plays a key role in the protection from dyslipidemia observed in patients with insulin receptoropathy.

These data are consistent with the concept of selective postreceptor hepatic insulin resistance (partial insulin resistance) in the highly prevalent form of insulin resistance (5). We were also able to extend these human observations by studying 2 patients with AKT2 mutations. We have previously demonstrated hepatic insulin resistance with respect to gluconeogenesis in one of these subjects (18), in whom we have now also demonstrated increased hepatic lipogenesis. One interpretation of these data is that the signaling pathway responsible for insulin activation of SREBP1c diverges from the insulin receptor/IRS/PI3K/AKT2/FOXO1 pathway proximal to AKT2 activation. Recently published observations in mice indicate that the specificity of insulin signaling in the liver lies downstream of IRS1 and IRS2 (21–23) and suggest that the insulin SREBP1c/lipogenic pathway diverges from the canonical pathway after IRS but before AKT2. This is consistent with the observations by Taniguchi et al. (24) in liver-specific PI3K knockout mice that reconstitution of the defect in these mice with an adenoviral construct expressing constitutively active PKCλ significantly increased SREBP1c expression (5- to 6-fold), whereas overexpression of a constitutively active Akt isoform had no discernible effect on SREBP1c expression. Alternatively, the lipogenic pathway might divert from the canonical pathway before IRS1/2. A caveat to this interpretation of our data is suggested by the observation that one of the patients with an AKT2 loss-of-function mutation had clinical evidence of femorogluteal lipodystrophy and had slightly more visceral adipose tissue (VAT) than her insulin receptoropathy counterparts (Table (Table22 and Figure Figure4).4). It remains possible, therefore, that altered AKT2 activity in adipose tissue contributes to the severe dyslipidemia in these patients.

Our observations concur with some of those of Biddinger et al. (8), who noted similar changes in liver TG and VLDL composition in LIRKO mice. However, those authors suggested that LIRKO mice were highly susceptible to hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerotic vascular disease when challenged with an atherogenic diet. “Atherogenic” mouse diets are similar to “Western” human diets, so one might expect patients with insulin receptor signaling defects to manifest similar abnormalities. Our data do not suggest that hypercholesterolemia is common in patients with insulin receptor defects. In our view this is in keeping with predominantly independent genetic and environmental regulation of cholesterol metabolism in humans.

It is also important to remember that our patients, unlike the LIRKO mice, have impaired insulin receptor function in all tissues and so may exhibit indirect hepatic effects of insulin receptor dysfunction in sites such as adipose tissue. For example, patients with insulin receptoropathy have significantly higher plasma adiponectin levels than is seen in other forms of severe insulin resistance, and indeed many have extreme hyperadiponectinemia (25). Adiponectin receptors are expressed in the liver, which is thought to be a key target for adiponectin action, and one recent study suggested that adiponectin lowers plasma TG levels by increasing VLDL catabolism, primarily in muscle (26). The possibility thus arises that high levels of adiponectin may contribute to the difference in lipid profile between patients with insulin receptoropathy and those with other forms of insulin resistance. While we cannot formally exclude this possibility, the 4 patients we studied in detail all had adiponectin levels within the healthy population range. Furthermore, we were able to show reduced hepatic lipogenesis and VLDL TG/ cholesterol levels in patients with insulin receptor mutations, implicating TG synthesis and thus VLDL production.

A significant body of work in vitro and a more limited number of in vivo observations have led to the suggestion that the dominant effect of insulin on VLDL synthesis and secretion is on APOB metabolism, with insulin suppressing VLDL production by enhancing APOB degradation (27, 28). If this were true in patients with primary insulin receptoropathy, one might expect these patients to manifest high VLDL production rates and a tendency toward hypertriglyceridemia, which is not what we have observed. This discrepancy probably reflects differences between the experimental paradigms used and the difficulty inherent in modeling a complex in vivo phenomenon. Interestingly, our findings are exactly in line with previous work in type 1 diabetes showing that VLDL TG content is lowered in well-controlled type 1 diabetes in euglycemic conditions (effectively a state of relative hepatic insulinopenia), with moreover no discernible difference in APOB kinetics in this situation (29). They are also consistent with data suggesting that VLDL production rates are strongly linked with liver fat content (30).

The level at which insulin signaling is impaired in pandemic insulin resistance remains unclear (31). While substantial heterogeneity is very likely, our observations suggest that the presence of metabolic dyslipidemia indicates that the signaling defect is, at least in the liver, at a postreceptor level. De novo lipogenesis is already known to be increased in obese patients with fatty liver (32) and in lean insulin-resistant diabetic offspring (1). Our observations in patients with partial lipodystrophy suggest that here too, the defect in insulin action probably occurs at a postreceptor level. Given the strong correlations between hypertriglyceridemia, fatty liver, and insulin resistance, we suggest that postreceptor hepatic insulin resistance (partial insulin resistance) is likely to be present in most forms of human insulin resistance.

In summary, by studying patients with rare, molecularly defined defects in the insulin signaling pathway, we provide human evidence supporting the notion that metabolic dyslipidemia and hepatic steatosis are the results of selective postreceptor hepatic insulin resistance in humans.

Methods

Participants.

Clinical studies were performed after approval of the National Health Service Research Ethics Committee United Kingdom. Each participant provided written informed consent, and all studies were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Genetically characterized patients were identified as part of a long-standing program of research into genetic and acquired forms of severe insulin resistance. Fasting blood samples were obtained from patients with severe insulin resistance caused by: (a) loss-of-function mutations in the insulin receptor, including patients with features of Donohue syndrome or Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome, and those with type A insulin resistance or the equivalent in male patients (9, 33); (b) inhibitory insulin receptor antibodies (acquired, or type B, insulin resistance) (34); (c) a dominant-negative loss-of-function mutation in AKT2 in 2 patients (18); and (d) different forms of lipodystrophy (35). Clinical and biochemical features of these participants are summarized in Table Table1.1. Healthy control volunteers were recruited by advertisement. All controls were nonsmokers with no medical conditions likely to influence energy balance and with no family history of diabetes (Supplemental Table 1; supplemental material available online with this article; 10.1172/JCI37432DS1). All subjects were euthyroid at the time of the study. Studies were conducted in the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility (WTCRF).

Biochemical assays.

Insulin, leptin, and adiponectin were measured using customized autoDELFIA immunoassays as previously described (25).

Oral glucose tolerance test.

Whole-body insulin sensitivity was assessed with a 3-hour, 75-g oral glucose tolerance test. After insertion of an antecubital intravenous line, blood samples were collected at –30, 0, 10, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 minutes for determination of plasma glucose, insulin, c-peptide, and FFAs.

Body composition and abdominal fat measurement.

Body composition was measured by Lunar Prodigy dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (GE Lunar). Abdominal fat distribution was measured using a Siemens 3T Tim Trio MR scanner to acquire a T1-weighted turbo spin echo, water-suppressed transaxial image through the abdomen at the L4 vertebral level. Slice thickness was 10 mm with an in-plane resolution of 1.25 × 1.25 mm (field of view, 400 × 400 mm; repetition time (TR) = 400 ms; echo time (TE) = 21 ms; 2 averages). Volumes of abdominal VAT and subcutaneous adipose tissue were calculated by using a semi-automated method, using a threshold map in combination with manual input to distinguish between the VAT and subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments.

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

Liver fat was measured using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy on a Siemens 3T Tim Trio MR scanner. A spectrum was obtained from a voxel, cube length 1.5 cm, located within the posterior aspect of the right lobe of the liver, using the point resolved selective spectroscopy (PRESS) sequence. During this measurement volunteers were given breathing instructions with a 7-s cycle, which was designed and gated such that participants were at the end of expiration during the localization and subsequent acquisition. Non-water suppressed data were acquired with TR = 7 s, TE = 35 ms, and 64 averages. The voxel was positioned to avoid blood vessels and the gall bladder using T2-weighted HASTE transaxial images that were also acquired in the same phase of respiration. The spectra were analyzed in jMRUI (36) and fitted using the AMARES (37) algorithm with prior knowledge. Liver fat was quantified by comparing the CH2 resonance at 1.3 ppm with water at 4.7 ppm.

De novo lipogenesis.

The incorporation of deuterium into plasma TG during administration of deuterium-labeled water was used to determine the fractional synthetic rate of fatty acids as described previously (1, 38). The energy requirement for each participant was predicted from estimates of basal metabolic rate scaled by a factor of 1.48, derived from energy expenditure levels in previous studies. Participants were provided with an energy balance meal of standard macronutrient composition at 7 pm on the evening prior to this measurement. Deuterium-labeled water (3 ml per kg of body water, 99.8% Cambridge Isotopes) was given at 8 pm and 10 pm in 2 portions of equal size. Blood was collected to assess de novo lipogenesis before the first loading dose of deuterium-labeled water and 12 hours (8 am) after the first loading dose. Deuterium enrichment of plasma water was determined by isotope ratio mass spectrometry of diluted samples (39) using a SIRA10 instrument (VG Isotopes Ltd.), and deuterium enrichment of plasma palmitate was determined by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (5973N GC/MS system; Agilent Technologies) of the methyl ester.

Calculations.

From the mass isotopomer distributions, the maximum number of deuterium molecules synthesized from plasma palmitate was 22 (38). When constant enrichment in the plasma water (precursor pool) was obtained, F was the fraction of palmitate synthesized during the time between the loading dose of the deuterium-labeled water and the collection time. When isotopic equilibrium in the product pool (palmitate) was obtained, F was constant. F = plasma palmitate enrichment/(22 × plasma deuterium enrichment). The percentage of de novo lipogenesis equalled F × 100%.

Statistics.

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Two-tailed Student’s t tests or 1-way ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni analyses were performed on data with a minimum P < 0.05 considered significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants and their referring physicians. We thank Marilena Leventi and Antony Wright for technical assistance with the measurement of de novo lipogenesis and the staff of the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, particularly Elaine Marriot, for assistance with clinical studies. We are grateful to the radiographers at the Wolfson Brain Imaging Centre, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, for their help in acquiring MRI and MRS data and to Fredrik Karpe for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust (to R.K. Semple: Intermediate Clinical Fellowship 080952/Z/06/Z; to S. O’Rahilly: Programme Grant 078986/Z/06/Z), GlaxoSmithKline (to D.B. Savage: GSK Clinical Fellowship), the United Kingdom NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, and the United Kingdom Medical Research Council Centre for Obesity and Related Metabolic Diseases.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: AKT2, protein kinase B; LIRKO, liver insulin receptor knockout; TG, triglyceride; VAT, visceral adipose tissue.

Citation for this article: J. Clin. Invest. 119:315–322 (2009). 10.1172/JCI37432

See the related Commentary beginning on page 249.

References

Articles from The Journal of Clinical Investigation are provided here courtesy of American Society for Clinical Investigation

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1172/jci37432

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

http://www.jci.org/articles/view/37432/files/pdf

Free to read at www.jci.org

http://www.jci.org/cgi/content/abstract/119/2/315

Free to read at www.jci.org

http://www.jci.org/cgi/content/full/119/2/315

Free to read at www.jci.org

http://www.jci.org/cgi/reprint/119/2/315.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1172/jci37432

Article citations

Dissociation between liver fat content and fasting metabolic markers of selective hepatic insulin resistance in humans.

Eur J Endocrinol, 191(4):463-472, 01 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39353069 | PMCID: PMC11497584

Case report: Glycaemic management and pregnancy outcomes in a woman with an insulin receptor mutation, p.Met1180Lys.

Clin Diabetes Endocrinol, 10(1):5, 10 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38461278 | PMCID: PMC10924971

Insulin resistance in NSCLC: unraveling the link between development, diagnosis, and treatment.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 15:1328960, 20 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38449844

Review

Insulin and aging - a disappointing relationship.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 14:1261298, 03 Oct 2023

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 37854186 | PMCID: PMC10579801

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Transcriptomics Reveals the Mechanism of Rosa roxburghii Tratt Ellagitannin in Improving Hepatic Lipid Metabolism Disorder in db/db Mice.

Nutrients, 15(19):4187, 28 Sep 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37836471 | PMCID: PMC10574348

Go to all (191) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Liver-specific inhibition of ChREBP improves hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in ob/ob mice.

Diabetes, 55(8):2159-2170, 01 Aug 2006

Cited by: 280 articles | PMID: 16873678

Multiple factors and pathways involved in hepatic very low density lipoprotein-apoB100 overproduction in Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty rats.

Atherosclerosis, 222(2):409-416, 11 Apr 2012

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 22546076

Mechanisms of hepatic very low-density lipoprotein overproduction in insulin resistance.

Trends Cardiovasc Med, 11(5):170-176, 01 Jul 2001

Cited by: 118 articles | PMID: 11597827

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Medical Research Council (5)

Targeting therapy to molecular mechanism of disease in obesity and related metabolic disorders

Prof Sir Stephen O'Rahilly, University of Cambridge

Grant ID: G0502115

WBIC acute brain injury collaborative grant

Professor John Pickard, University of Cambridge

Grant ID: G0600986

Developing the WTCRF in Cambridge: Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy and a Nutrition Resource & Appetite Laboratory

Prof Krishna Chatterjee, University of Cambridge

Grant ID: G0701532

Acute Brain Injury: herterogeneity of Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targets and Outcome Effects

Professor John Pickard, University of Cambridge

Grant ID: G9439390

Biomarkers for nutritional intake and health

Professor Dietrich Volmer, MRC Human Nutrition Research Group

Grant ID: MC_U105960396

Wellcome Trust (2)

Grant ID: 078986/Z/06/Z

Grant ID: 080952/Z/06/Z