Abstract

Free full text

The Neurodevelopmental Hypothesis of Schizophrenia, Revisited

Abstract

While multiple theories have been put forth regarding the origin of schizophrenia, by far the vast majority of evidence points to the neurodevelopmental model in which developmental insults as early as late first or early second trimester lead to the activation of pathologic neural circuits during adolescence or young adulthood leading to the emergence of positive or negative symptoms. In this report, we examine the evidence from brain pathology (enlargement of the cerebroventricular system, changes in gray and white matters, and abnormal laminar organization), genetics (changes in the normal expression of proteins that are involved in early migration of neurons and glia, cell proliferation, axonal outgrowth, synaptogenesis, and apoptosis), environmental factors (increased frequency of obstetric complications and increased rates of schizophrenic births due to prenatal viral or bacterial infections), and gene-environmental interactions (a disproportionate number of schizophrenia candidate genes are regulated by hypoxia, microdeletions and microduplications, the overrepresentation of pathogen-related genes among schizophrenia candidate genes) in support of the neurodevelopmental model. We relate the neurodevelopmental model to a number of findings about schizophrenia. Finally, we also examine alternate explanations of the origin of schizophrenia including the neurodegenerative model.

The Neurodevelopmental Theory of Schizophrenia and Supportive Evidence

Schizophrenia is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects youth in puberty and is manifested by a disruption in cognition and emotion along with negative (ie, avolition, alogia, apathy, poor or nonexistent social functioning) and positive (presence of hallucinations, delusions) symptoms. According to the neurodevelopmental hypothesis, the etiology of schizophrenia may involve pathologic processes, caused by both genetic and environmental factors, that begin before the brain approaches its adult anatomical state in adolescence.1 These neurodevelopmental abnormalities, developing in utero as early as late first or early second trimester2 for some and thereafter for others, have been suggested to lead to the activation of pathologic neural circuits during adolescence or young adulthood (sometimes owing to severe stress), which leads to the emergence of positive or negative symptoms or both.2,3,4

Earlier neuropathologic work indicated that some cases of schizophrenia result from embryologic maldevelopment.5 E. Slater also referred to maldevelopmental similarities between temporal lobe epilepsy and schizophrenia and stressed their possible neuropathologic basis.6 The emergence of evidence for cortical maldevelopment in schizophrenia and the development of several plausible animal models of schizophrenia,7 which are based on various paradigms that produce behavioral abnormalities or altered sensitivity to dopaminergic drugs only in adolescent or adult animals, have strengthened the link between maldevelopment and schizophrenia. The concept of schizophrenia as a neurodevelopmental disorder is also consistent with other epidemiologic and clinical lines of evidence, discussed in the following sections.

A “2-hit” model proposed by Keshavan8,9 works within the framework of the neurodevelopmental theory in which maldevelopment during 2 critical time points (early brain development and adolescence) combines to produce the symptoms associated with schizophrenia. According to this model, early developmental insults may lead to dysfunction of specific neural networks that would account for premorbid signs and symptoms observed in individuals that later develop schizophrenia.8 At adolescence, excessive elimination of synapses and loss of plasticity may account for the emergence of symptoms.8,9

Congenital Abnormalities

Multiple markers of congenital anomalies indicative of neurodevelopmental insults have been found in schizophrenia.10,11 Such anomalies include agenesis of corpus callosum, stenosis of sylvian aqueduct, cerebral hamartomas, and cavum septum pellucidum. Presence of low-set ears, epicanthal eye folds, and wide spaces between the first and second toes are suggestive of first trimester anomalies.10,11 There is, however, support for abnormal dermatoglyphics in patients with schizophrenia indicating a second trimester event.12,13 Multiple reports indicate the presence of premorbid neurologic soft signs in children who later develop schizophrenia.14–16 Slight posturing of hands and transient choreoathetoid movements have been observed during the first 2 years of life in children who later developed schizophrenia.15,17 Additionally, poor performance on tests of attention and neuromotor performance, mood and social impairment, and excessive anxiety have been reported to occur more frequently in high-risk children with a schizophrenic parent.18,19 All these findings are consistent with schizophrenia as a syndrome of abnormal brain development.

Environmental Factors

There is a large body of epidemiologic research showing an increased frequency of obstetric and perinatal complications in schizophrenic patients.20 The complications observed include periventicular hemorrhages, hypoxia, and ischemic injuries.10,21 There is also a robust collection of reports indicating that environmental factors, especially viral infections, can increase the risk for development of schizophrenia.22,23 Hare et al24 and Machon et al25 reported on excess of schizophrenic patients being born during late winter and spring as indicators of potential influenza infections being responsible for these cases. Indeed, the majority of nearly 50 studies performed in the intervening years indicate that 5%–15% excess schizophrenic births in the northern hemisphere occur during the months of January and March.26–28 This excess winter birth has not been shown to be due to unusual patterns of conception in mothers or to a methodological artifact.26,29 Machon et al25 and Mednick et al30 showed that the risk of schizophrenia was increased by 50% in Finnish individuals whose mothers had been exposed to the 1957 A2 influenza during the second trimester of pregnancy. Later, 9 out of 15 studies performed replicated Mednick's findings of a positive association between prenatal influenza exposure and schizophrenia.2 These association studies showed that exposure during the 4th–7th months of gestation affords a window of opportunity for influenza virus to cause its teratogenic effects on the embryonic brain.4 Additionally, 3 out of 5 cohort and case-control studies support a positive association between schizophrenia and maternal exposure to influenza prenatally.31–33 Subsequent studies have now shown that other viruses such as rubella34 may also increase the risk for development of schizophrenia in the affected progeny of exposed mothers.26,34 A review by Brown35 summarized that (1) there was a 10- to 20-fold risk of developing schizophrenia following prenatal exposure to rubella; (2) prenatal exposure to influenza in the first trimester increased 7-fold, and infection in early to midgestation increased risk 3-fold; and (3) presence of maternal antibodies against Toxoplasma gondii lead to 2.5-fold increased risk.35 By far, the most exciting evidence linking viral exposure to development of schizophrenia was published by Karlsson et al,23 who provided data suggestive of a possible role for retroviruses in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia.22 Karlsson et al23 identified nucleotide sequences homologous to retroviral polymerase genes in the cerebrospinal fluid of 28.6% of subjects with schizophrenia of recent origin and in 5% of subjects with chronic schizophrenia. In contrast, such retroviral sequences were not found in any individuals with noninflammatory neurological illnesses or in normal subjects.22,23 More recently, Perron et al.220 using an immunoassay to quantify serum levels of human endogenous retrovirus type W family GAG and envelope (ENV) proteins in subjects with schizophrenia and matched controls. Positive antigenemia for ENV was found in 23 of 49 (47%) and for GAG in 24 of 49 (49%) of patients with schizophrenia. In contrast, for control subjects only 1 of 30 (3%) for ENV and 2 of 49 (4%) for GAG were positive in blood donors (p < .01 for ENV; p < .001 for GAG), providing further evidence of an association between retroviruses and schizophrenia.220 The upshot of these studies and previous epidemiological reports is that schizophrenia may represent the shared phenotype of a group of disorders whose etiopathogenesis involves the interaction between genetic influences and environmental risks, such as viruses operating on brain maturational processes.22 Moreover, identification of potential environmental risk factors, such as influenza virus or retroviruses such as endogenous retroviral-9 family and the human endogenous retrovirus-W species observed by Karlsson et al,23 will help in targeting early interventions at repressing the expression of these transcripts. An alternate approach would be to vaccinate against influenza thus influencing the course and outcome of schizophrenia in the susceptible individuals.22

There are at least 2 mechanisms that may be responsible for transmission of viral effects from the mother to the fetus. (1) Via direct viral infection: There are clinical, as well as direct experimental, reports36–39 showing that human influenza A viral infection of a pregnant mother may cause transplacental passage of viral load to the fetus. In a series of reports, Aronsson and colleagues used human influenza virus (A/WSN/33, a neurotropic strain of influenza A virus) on day 14 of pregnancy, to infect pregnant C57BL/6 mice intranasally. Viral RNA and nucleoprotein were detected in fetal brains, and viral RNA persisted in the brains of exposed offspring for at least 90 days of postnatal life thus showing evidence for transplacental passage of influenza virus in mice and the persistence of viral components in the brains of progeny into young adulthood.38 Additionally, Aronsson et al38 have demonstrated that 10–17 months after injection of the human influenza A virus into olfactory bulbs of TAP1 mutant mice, viral RNA encoding the nonstructural NS1 protein was detected in midbrain of the exposed mice. The product of NS1 gene is known to play a regulatory role in the host cell metabolisms.40 Several in vitro studies have also shown the ability of human influenza A virus to infect Schwann cells,41 astrocytes, microglial cells and neurons,36 and hippocampal GABAergic cells,42,43 selectively causing persistent infection of target cells in the brain. (2) Via induction of cytokine production: Multiple clinical and experimental reports show the ability of human influenza infection to induce production of systemic cytokines by the maternal immune system, the placenta, or even the fetus itself.44–48 New reports show presence of serologic evidence of maternal exposure to influenza as causing increased risk of schizophrenia in offspring.4 Offspring of mothers with elevated immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin M levels, as well as antibodies to herpes simplex virus type 2, during pregnancy have an increased risk for schizophrenia.49 Cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) are elevated in the pregnant mothers after maternal infection44,45,48 and after infection in animal models.47,48 All these cytokines are known to regulate normal brain development and have been implicated in abnormal corticogenesis.50–52 Additionally, expression of messenger RNAs (mRNAs) for cytokines in the central nervous system (CNS) is developmentally regulated both in man and in mouse,53–57 emphasizing the significant role that cytokines play during neurodevelopment. IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α cross the placenta and are synthesized by mother,58 by the placenta,59 and by the fetus.59 Maternal levels of TNF-α and IL-8 have been shown to be elevated in human pregnancies in which the offspring goes on to develop schizophrenia.4,59 A more relevant series of studies in different animal models for schizophrenia show that maternal infection with human influenza mimic poly I:C, a synthetic double-stranded RNA that stimulates a cytokine response in mice, can cause abnormalities in prepulse inhibition (PPI)60 or, after maternal exposure to E. coli cell wall endotoxin lipopolysaccharide, cause disruption of sensorimotor gating in the offspring.61 Finally, maternal exposure to poly I:C also causes disrupted latent inhibition in rat.62 All these models suggest that direct stimulation of cytokine production by infections or immunogenic agents cause disruptions in various brain structural or behavioral indices of relevance to schizophrenia. Other factors associated with increased schizophrenic births include famine during pregnancy,63,64 Rh factor incompatibility,65 and autoimmunity due to infectious agents.66

A number of animal models are currently in use to study schizophrenia and identify potential new therapies (reviewed by Carpenter and Koenig7). Our laboratory has studied the effects of prenatal human influenza viral infection on day 9 of pregnancy in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice and their offspring. These studies showed the deleterious effects of influenza on growing brains of exposed offspring. Briefly, embryonic day 9 (E9) pregnant BALB/c mice were exposed to influenza A/NWS/33 (H1N1) or vehicle, following determination of viral dosage, causing sublethal lung and upper respiratory infection. Pregnant mice were allowed to deliver pups. The day of delivery was considered day 0. Prenatally infected murine brains from postnatal day 0 showed significant reductions in reelin-positive cell counts in layer I of neocortex and other cortical layers (P <

< .0001) when compared with controls.67 Whereas layer I Cajal-Retzius cells produced significantly less reelin in infected animals, the same cells showed normal production of calretinin and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) when compared with control brains.67 This work has recently been confirmed by Meyer et al68 who also observed a decrease in reelin-positive cells in medial prefrontal cortex (PFC) following poly I:C exposure on E9 and E17.

.0001) when compared with controls.67 Whereas layer I Cajal-Retzius cells produced significantly less reelin in infected animals, the same cells showed normal production of calretinin and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) when compared with control brains.67 This work has recently been confirmed by Meyer et al68 who also observed a decrease in reelin-positive cells in medial prefrontal cortex (PFC) following poly I:C exposure on E9 and E17.

Additionally, prenatal viral infection on E9 resulted in various behavioral abnormalities.60 These included abnormal exploratory behavior, reflecting difficulty handling stress, similar to what is observed in schizophrenia. The offspring of exposed mice showed significantly less time exploring their environment vs control mice.60 Moreover, the offspring of exposed mice contacted each other less frequently than the control mice, suggesting altered social behavior.60 Finally, the offspring of exposed mice displayed an abnormal acoustic startle response,60 similar to PPI deficits in untreated schizophrenic subjects.69 Administration of antipsychotic agents chlorpromazine (a typical agent) and clozapine (an atypical agent), agents which treat schizophrenic symptoms and correct PPI deficits in patients, caused significant increases in PPI in the exposed mice vs controls, correcting the PPI deficits.60 The response by offspring of exposed mice to both antipsychotics shows that our animal model has predictive validity for positive symptoms of schizophrenia.60

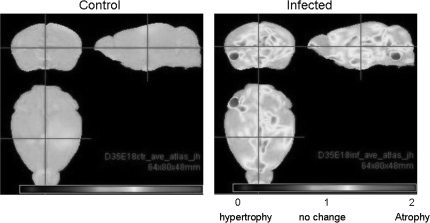

Our laboratory has previously shown that infection of BALB/c mice at E9 has deleterious effects on brain morphology67,70 (figure 1). Prenatally infected brains from P0 displayed decreases in neocortical and hippocampal thickness.67 Moreover, brains at P0 displayed increased pyramidal cell density and significantly reduced pyramidal cell nuclear size.70 By adulthood (P98), there continued to be an increase in pyramidal cell density and nonpyramidal cell density and a significant reduction in pyramidal cell nuclear size.70 Taken together, these data suggest that prenatal viral infection at E9 (late first trimester) causes persistent deleterious changes in brain morphology. Morphometric analysis of brain also revealed numerous defects following infection of C57BL/6 mice at E18 (late second trimester). Analysis of brain and lateral ventricular volume areas in postnatal brains showed significant atrophy of the brain volume by approximately equal to 4% (P <

< .05) in P35 offspring of exposed mice.71 There were significant reductions in volume for the cerebellum (P

.05) in P35 offspring of exposed mice.71 There were significant reductions in volume for the cerebellum (P <

< .001) and hippocampus (P

.001) and hippocampus (P <

< .00005) at P35.71 Fractional anisotropy of corpus callosum revealed white matter atrophy on P35 offspring (P

.00005) at P35.71 Fractional anisotropy of corpus callosum revealed white matter atrophy on P35 offspring (P <

< .0082) of exposed mice.71

.0082) of exposed mice.71

Brain gene expression also changes in response to prenatal viral infection.71–73 Gene expression data showed a significant (P <

< .05) at least 1.5-fold up- or downregulation of genes in frontal (43 upregulated and 29 downregulated at P0, 16 upregulated and 17 downregulated at P14, and 86 upregulated and 24 downregulated at P56), hippocampal (129 upregulated and 46 downregulated at P0, 9 upregulated and 12 downregulated at P14, and 45 upregulated and 17 downregulated at P56), and cerebellar (120 upregulated and 37 downregulated at P0, 11 upregulated and 5 downregulated at P14, and 74 upregulated and 22 downregulated at P56) areas of mouse offspring.71 Several genes, which have been previously implicated in etiopathology of schizophrenia, were shown to be affected significantly (P

.05) at least 1.5-fold up- or downregulation of genes in frontal (43 upregulated and 29 downregulated at P0, 16 upregulated and 17 downregulated at P14, and 86 upregulated and 24 downregulated at P56), hippocampal (129 upregulated and 46 downregulated at P0, 9 upregulated and 12 downregulated at P14, and 45 upregulated and 17 downregulated at P56), and cerebellar (120 upregulated and 37 downregulated at P0, 11 upregulated and 5 downregulated at P14, and 74 upregulated and 22 downregulated at P56) areas of mouse offspring.71 Several genes, which have been previously implicated in etiopathology of schizophrenia, were shown to be affected significantly (P <

< .05) in the same direction and the magnitude of change was validated by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)71 (table 1). There were also several genes that were known to be involved in influenza-mediated RNA processing and that were upregulated in all 3 brain areas and continued to be present at P0, eg, NS1 influenza–binding protein and aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator genes.71

.05) in the same direction and the magnitude of change was validated by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)71 (table 1). There were also several genes that were known to be involved in influenza-mediated RNA processing and that were upregulated in all 3 brain areas and continued to be present at P0, eg, NS1 influenza–binding protein and aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator genes.71

Table 1.

Microarray and qRT-PCR Results for Selected Affected Genes in E18 Infected Mice

| Gene | Symbol | Area | PD | Microarray Fold Change | Microarray P Value | Gene Relative to Normalizer (qRT-PCR) | qRT-PCR P Value |

| Cdc42 guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 9 (Collybistin) | Arhgef | PFC | P0 | 2.79 | .023 | 1.25 | .026 |

| Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator | Arnt | Cer | P0 | * | * | 1.51 | .024 |

| Hipp | P0 | * | * | 2.08 | .021 | ||

| PFC | P0 | * | * | 1.45 | .006 | ||

| Death-associated protein kinase 1 | Dapk1 | Cer | P0 | 2.18 | .0051 | 1.22 | .013 |

| DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 3, Y-linked | Dby | Cer | P56 | 4.00 | .044 | 6.71 | .005 |

| Ephrin B2 | Efnb2 | Hipp | P0 | 2.33 | .035 | 2.41 | .021 |

| V-erb-a erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 4 (avian) | Erbb4 | Hipp | P0 | 3.43 | .0055 | 2.10 | .048 |

| Influenza virus NS1A–binding protein | Ivns1abp | Cer | P0 | * | * | 1.22 | .0004 |

| Hipp | P0 | * | * | 1.91 | .079 | ||

| PFC | P0 | * | * | 1.02 | .86 | ||

| Myelin transcription factor 1–like | Myt1l | Hipp | P0 | 2.36 | .039 | 2.03 | .051 |

| Neurexophilin | Nxph2 | Hipp | P0 | 4.15 | .0006 | 3.50 | .010 |

| Sema domain, immunoglobulin domain, short basic domain, secreted, (semaphorin) 3A | Sema3a | Hipp | P0 | 3.52 | .018 | 3.49 | .013 |

| SRY-box–containing gene 2 | Sox2 | Cer | P0 | 2.16 | .008 | 1.30 | .010 |

| Transferrin receptor | Trfr2 | Cer | P0 | 2.27 | .045 | 1.57 | .026 |

| Ubiquitously transcribed tetratricopeptide repeat gene, Y chromosome | Uty | Cer | P56 | 3.68 | .033 | 5.35 | .018 |

Note: Data taken from Fatemi et al.71 E, embryonic; PD, postnatal date; PFC, prefrontal cotex; Cer, cerebellum; Hipp, hippocampus; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; *, not changed in microarray; bold values, p < 0.05.

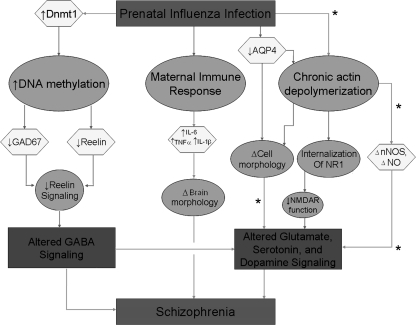

Prenatal viral infection may lead to the development of schizophrenia in multiple ways (figure 2). One way is via an epigenetic mechanism in which hypermethylation of promoters by molecules such as DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) results in altered expression of schizophrenia candidate genes. DNMT1 mRNA has been shown to be increased in brains of subjects with schizophrenia.74 Activation of DNMT1, in turn, hypermethylates promoters for reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD)67-kDa protein genes resulting in decreased levels of these molecules.75 These changes contribute to abnormal brain development and altered γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) signaling and subsequent genesis of schizophrenia. Maternal infection may also lead to activation of the maternal immune response leading to altered levels of cytokines including IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α that regulate normal brain development and are altered following maternal infection.44,45,48 Changes may lead to abnormal cortical development50–52 and, ultimately, schizophrenia. Prenatal viral expression may also lead to altered expression of genes that are involved in cell-cell communication and changes in cell structure due to chronic actin depolymerization (S.H. Fatemi and M. Peoples, unpublished observations, 2007). Aquaporin 4 is localized to astrocytes and ependymal cells in brain and is involved with water transport.76,77 Aquaporin 4 protein expression is significantly decreased at postnatal day 35 in neocortex in BALB/c mice following infection at E978 possibly resulting in altered cell morphology. Similarly, chronic actin depolymerization may alter gene expression in schizophrenia (S.H. Fatemi and M. Peoples, unpublished observations, 2007). nNOS, which is associated with F-actin, displays altered expression following prenatal viral infection at E9 and may show altered expression following actin disruption. Actin depolymerization (with cytochalasin D) causes internalization of NR1 subunit of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and therefore decreased NMDA currents leading to altered signaling, but it is unknown whether this occurs in schizophrenia. Our laboratory has observed significant increase in nNOS at P35 and a significant decrease at P56 that may lead to altered synaptogenesis and excitotoxicity in neonatal brains.79

A Hypothesis of How Prenatal Viral Infection Could Contribute to the Development of Schizophrenia. Prenatal viral infection may lead to (1) activation of DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) that in turn changes methylation of promoters for a variety of genes leading to altered levels of molecules such as glutamic acid decarboxylase 67-kDa protein (GAD67) and reelin (S.H. Fatemi, unpublished observations).74,75 These changes may result in abnormal development and altered γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) signaling and subsequent genesis of schizophrenia; (2) activation of the maternal immune response leading to altered levels of cytokines including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α)44,45,48 that regulate normal brain development.50–52 Changes may lead to abnormal cortical development and, ultimately, schizophrenia; and (3) altered expression of genes that are involved in cell-cell communication and changes in cell structure due to chronic actin depolymerization (S.H. Fatemi and M. Peoples, unpublished observations, 2007) may lead to dysregulation of multiple signaling systems that have been observed in schizophrenia. *, Pathways that require more substantial support.

Genetics

The mode of transmission in schizophrenia is unknown and most likely complex and non-Mendelian.10,80 Chromosomal abnormalities show evidence for involvement of a balanced reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 1q42 and 11q14.3, with disruption of disrupted in schizophrenia 1 and 2 (DISC1 and DISC2) genes on 1q42, being associated with schizophrenia.80,81 Additionally, an association between a deletion on 22q11, schizophrenia, and velocardiofacial syndrome has been reported.82 Mice with similar deletions exhibit sensorimotor gating abnormalities.83

Linkage and association studies80,84,85 show 12 chromosomal regions containing 2181 known genes84 and 9 specific genes80 as being involved in etiology of schizophrenia.80 Variations/polymorphisms in 9 genes including neuregulin 1 (NRG1), dystrobrevin-binding protein 1 (DTNBP1), G72 and G30, regulator of G-protein signaling 4 (RGS4), catechol-O-methytransferase (COMT), proline dehydrogenase (PRODH), DISC1 and DISC2, serotonin 2A receptor, and dopamine receptor D3 (DRD3) have been associated with schizophrenia (table 2). However, of the various candidate genes, there is no single gene whose genetic association to schizophrenia has been replicated in every study.86

Table 2.

Risk Genes for Schizophrenia

| Gene | Abbreviation | Locus |

| Neuregulin | NRG1 | 8p12–p21 |

| Dysbindin | DTNBP1 | 6p22 |

| G72 | G72 | 13q34 |

| D-amino acid oxidase | DAAO | 12q24 |

| RGS4 | RGS4 | 1q21–22 |

| Catechol-O-methyltransferase | COMT | 22q11 |

| Proline dehydrogenase | PRODH | 22q11 |

| Reelin | RELN | 7q22 |

Another means of studying the genetic basis of schizophrenia uses the technique of DNA microarray.87,88 These studies are based on discovering genes either repressed or stimulated significantly in well-characterized postmortem brain tissues from subjects with schizophrenia and matched healthy controls and peripheral lymphocytes obtained from schizophrenic and matched healthy controls and antipsychotic-treated brains of rodents (table 3). Genes involved in drug response or in etiopathogenesis of schizophrenia can be compared and studied to better understand the mechanisms responsible for this illness.87

Table 3.

Candidate Genes: Postmortem Studies and Animal Models

| Gene | Abbreviation | Postmortem | Animal model |

| Adenosine A2A receptor | ADORA2A | + | + |

| Apolipoprotein D | APOD | + | + |

| CDC42 guanine nucleotide exchange factor 9 | ARHGEF9 | + | + |

| Complexin 2 | CPLX2 | + | + |

| Distal-less homeobox 1 | DLX1 | + | — |

| Dopamine receptor D1 | DRD1 | + | — |

| Dopamine receptor D2 | DRD2 | + | + |

| GABAA receptor, subunit A1 | GABRA1 | + | — |

| GABAA receptor, subunit A5 | GABRA5 | + | + |

| GABAB receptor 1 | GABBR1 | + | — |

| Glutamic acid decarboxylase 2 | GAD2 | + | — |

| Glial fibrillary acidic protein | GFAP | + | + |

| Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA1 | GRIA1 | + | — |

| Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA2 | GRIA2 | + | — |

| Myelin and lymphocyte protein | MAL | + | — |

| Myelin basic protein | MBP | + | + |

| Neuronal PAS domain protein 1 | NPAS1 | + | + |

| Proteolipid protein | PLP1 | + | — |

| Reelin | RELN | + | + |

| Regulator of G-protein signaling 4 | RGS4 | + | — |

| Short stature homeobox 2 | SHOX2 | + | — |

| Synapsin II | SYN2 | + | — |

Biological markers consistent with prenatal occurrence of neurodevelopmental insults in schizophrenia include changes in the normal expression of proteins that are involved in early migration of neurons and glia, cell proliferation, axonal outgrowth, synaptogenesis, and apoptosis. Some of these markers have been investigated in studies of various prenatal insults in potential animal models for schizophrenia thus helpful in deciphering the molecular mechanisms for genesis of schizophrenia.7

Several recent reports implicate various gene families as being involved in pathology of schizophrenia using DNA microarray technology, ie, genes involved in signal transduction,89–98 cell growth and migration,91 myelination,89,99 regulation of presynaptic membrane function,92,93 and γ-aminobutyric acid–mediated (GABAergic) function.89,94 By far, the most well-studied and replicated data deal with genes involved in oligodendrocyte- and myelin-related functions. Hakak et al89 using mostly elderly schizophrenic and matched control dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) homogenates showed downregulation of 5 genes whose expression is enriched in myelin-forming oligodendrocytes, which have been implicated in the formation and maintenance of myelin sheaths. Later, Tkachev et al99 using area 9 homogenates from Stanley Brain Collection showed significant downregulation in several myelin- and oligodendrocyte-related genes such as proteolipid protein 1,96 myelin-associated glycoprotein, oligodendrocyte-specific protein CLDN11, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein, myelin basic protein, neuroregulin receptor v-erb-a erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 3 (ERBB3), transferrin, olig 1, olig 2, and SRY Box 10. 99 Mirnics et al92 showed downregulation of genes involved in presynaptic function in the PFC such as methylmaleimide-sensitive factor, synapsin II, synaptojanin 1, and synaptotagmin 5. Vawter et al93 showed downregulation of histidine triad nucleotide–binding protein and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2N. Another important family of genes involved in schizophrenia are genes involved in glutamate and GABAergic function220,221. Hakak et al89 showed an upregulation of several genes involved in GABA transmission, such as GAD65- and 67-kDa protein genes. However, several reports have shown decreases in these proteins in schizophrenia.97,98,100 Hashimoto et al94 showed a downregulation of parvalbumin gene, and Vawter et al93 showed downregulation of glutamate receptor α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazoleproprionate (AMPA). Another gene family of import in schizophrenia deals with signal transduction. Hakak et al89 showed upregulation of several postsynaptic signal transduction pathways known to be regulated by dopamine, consistent with the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia95,101 such as cAMP-dependent protein kinase subunit RII-β and nel-related protein 2. In a similar vein, Mirnics and Lewisl90 also showed downregulation of RGS4 gene in PFC of schizophrenia. Recently in a study of temporal gyrus, Bowden et al,102 found that a number of genes related to neurotransmission (GRIN2B, GRIP2, SYT7), neurodevelopment (DAB1, SEMA5A), and intracellular signaling (PIK3R1, CACNG2) were significantly altered.102 Chung et al91 showed upregulation of heat shock 70 gene in schizophrenic brain.91 A number of schizophrenia candidate genes have been found to change in PFC over the course of the life span in brain samples from control subjects via microarray: (1) RGS4 and glutamate receptor metabotropic 3 (GRM3) expression decreased across the age range, (2) PRODH and DARPP32 expression increased with age, and (3) NRG1, ERBB3, and nerve growth factor receptor showed altered expression during the years of greatest risk for the development of schizophrenia.103

Interaction Between Genes and Environment

Genetic risk factors may also interact with obstetric complications to increase risk of schizophrenia,104–106 and it has been suggested known susceptibility genes for schizophrenia were more likely than randomly selected genes to be regulated by hypoxia/ischemia.107 Nicodemus et al108 recently tested whether a set of 13 schizophrenia susceptibility genes thought to be regulated in part by hypoxia statistically interact with obstetric complications. Four genes: v-AKT murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, DTNBP1, and GRM3 showed significant interactions,76 and all 4 have been shown to have neuroprotective roles.107

In a study of schizophrenia candidate genes, Schmidt-Kastner et al107 found that at least 50% were regulated by hypoxia and/or were expressed in the vasculature.107 These genes included CHRNA7, COMT, GAD1, NRG1, RELN, and RGS4.107 The authors proposed that the interaction of genes and “internal” environmental factors, in this case hypoxia, result in developmental perturbations leading to a predisposition to schizophrenia.107 However, additional external factors would have to come into play postnatally for the full development of schizophrenia.107

Another approach to studying the genetic contribution is to examine rare structural variants including microduplications and microdeletions. These have previously been shown to underlie illnesses including neurological and neurodevelopmental syndromes.109 Two recent reports by Walsh et al110 and the International Schizophrenia Consortium111 have used this approach in subjects with schizophrenia. Walsh et al110 found that novel deletions and duplications of genes were present in 5% of controls compared with 15% of subjects with schizophrenia (P < .0008) and 25% of subjects with early-onset schizophrenia (P < .0001). The majority of genes identified were disproportionately associated with pathways important for brain development, including synaptic long-term transmission, NRG signaling, axonal guidance, and integrin signaling.110 A large-scale genome-wide survey of copy number variants (CNVs) performed by the International Schizophrenia Consortium111 revealed that subjects with schizophrenia were 1.15 times more likely to have a higher rate of CNVs than controls.111 Associations with schizophrenia were found for large deletions of regions on chromosomes 1, 15, and 22 impacting a number of genes.111

Interestingly, 19 of the genes impacted in both articles have also been significantly upregulated or downregulated following prenatal viral infection at embryonic days 9, 16, and 18 with our animal model (table 4) providing further convergence between our model and human genetic data. Two genes, v-erb-a erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 4 (Erbb4) and solute carrier family 1 (glial high-affinity glutamate transporter), member 3 (Slc1a3), have been previously associated with schizophrenia.112,113 Erbb4 gene codes for a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor for NRG1. This gene is involved in neuron and glial proliferation, differentiation, and migration processes. Binding of Erbb4 and NRG1 leads to NMDA receptor current propagation, a process that is apparently defective in schizophrenia.112 A recent report shows that polymorphisms in NRG1 are associated with gray and white matter alterations in childhood-onset schizophrenia,114 a striking similarity seen in our viral model of schizophrenia, where brain atrophy also occurs in puberty in the exposed mice.71 The significant increase in Erbb4 mRNA we have observed may be due to decreases in levels of NRG1 in the exposed mice.71 Erbb4 also interacts with 2 other genes common to both lists: discs, large homolog 2115 and membrane-associated guanylate kinase, inverted 2 at neuronal synapses.116

Table 4.

Novel Structural Variants in Genomic DNA That Delete or Duplicate Genes in Subjects With Schizophrenia and Controls Similar to Genes Significantly Altered Following Prenatal Viral Infection

| Chromosomal Abnormality in Subjects with Schizophrenia | Microarray of Virally Infected Mice | |||||||

| Name | Gene | Chr | Dup/Del | Disease | Area | Inf Date | PD | Regulation |

| Ankyrin repeat domain 35110 | Ankrd35 | 1 | Del | Cer | E9 | P56 | Up | |

| Cer | E16 | P56 | Down | |||||

| Hipp | E16 | P56 | Up | |||||

| B-cell CLL/lymphoma 9110 | Bcl-9 | 1 | Del | Hipp | E16 | P0 | Up | |

| Lix1-like111 | Lix1l | 1 | Del | Hipp | E16 | P0 | Up | |

| v-erb-a erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 4 (avian) 111 | Erbb4 | 2 | Del | Scz | Cer | E16 | P14 | Up |

| Hipp | E16 | P0 | Up | |||||

| PFC | E16 | P56 | Up | |||||

| Cer | E18 | P56 | Up | |||||

| Hipp | E18 | P0 | Up | |||||

| S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (p45)111 | Skp2 | 5 | Del | Cer | E16 | P56 | Up | |

| Solute carrier family 1 (glial high-affinity glutamate transporter), member 3 (aka EAAT1)111 | Slc1a3 | 5 | Del | Scz | Cer | E16 | P56 | Up |

| Hipp | E16 | P0 | Up | |||||

| PFC | E16 | P14 | Up | |||||

| Cation-chloride cotransporter–interacting protein-1 (Solute carrier family 12 [potassium/chloride transporters], member 9)111 | Slc12a9 | 7 | Dup | PFC | E18 | P14 | Down | |

| Membrane-associated guanylate kinase, inverted 2111 | Magi2 | 7 | Dup | Hipp | E16 | P0 | Up | |

| Myeloid/lymphoid or mixed-lineage leukemia 3111 | Mll3 | 7 | Dup | Cer | E16 | P56 | Up | |

| Putative homeodomain transcription factor 2111 | Phtf2 | 7 | Dup | Hipp | E18 | P14 | Up | |

| PTK2 protein tyrosine kinase 2111 | Ptk2 | 8 | Dup | Hipp | E16 | P0 | Up | |

| SWI/SNF–related, matrix-associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a, member 2111 | Smarca2 | 9 | Dup | Cer | E16 | P56 | Up | |

| Hipp | E16 | P0 | Up | |||||

| Cer | E18 | P56 | Up | |||||

| Discs, large homolog 2 (Drosophila)111 | Dlg2 | 11 | Del | Hipp | E16 | P0 | Up | |

| Kruppel-like factor 13111 | Klf13 | 15 | Del | Cer | E18 | P0 | Up | |

| Myotubularin-related protein 10110 | Mtmr10 | 15 | Del | Cer | E16 | P56 | Down | |

| Apoptosis-inducing factor, mitochondrion-associated 3110 | Aifm3 | 22 | Del | PFC | E16 | P14 | Up | |

| Goosecoid-like110 | Gsc1 | 22 | Del | Cer | E9 | P56 | Up | |

| HpaII tiny fragments locus 9c110 | Ht9c | 22 | Del | Cer | E16 | P56 | Up | |

| Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carrier, citrate transporter), member 1110 | Slc25a1 | 22 | Del | Cer | E16 | P14 | Up | |

Note: Data taken from Walsh et al,110 Stone et al,111 and S.H. Fatemi, unpublished observations, 2008; Chr, chromosome; Dup, duplication; Del, deletion; Inf, infected; PD, postnatal date; Cer, cerebellum; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; Hipp, hippocampus; PFC, prefrontal cortex; Scz, schizophrenia; E, embryonic.

Slc1a3 codes for a glutamate transporter found on glial cells that functions to regulate neurotransmitter concentrations at excitatory glutamatergic synapses.117,118 Slc1a3 has been shown to be elevated in thalamus of subjects with schizophrenia.113 We have also observed elevated levels of Slc1a3 mRNA following prenatal viral infection at E16 in cerebellum at P56, in hippocampus at P0, and in PFC at P14 (S.H.F., unpublished observations, 2008). The 506-kb deletion that disrupts Slc1a3 also disrupts S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (Skp2), which suppresses apoptosis mediated by DNA damage,118 and leads to the formation of a chimeric transcript.110 Interestingly, Skp2 mRNA is similarly elevated in cerebellum at P56 following prenatal viral infection at E16 (S.H. Fatemi, unpublished observations, 2008).

Further analysis of some of the virally regulated brain genes in the exposed progeny that were also similarly disrupted in subjects with schizophrenia by microdeletions or microduplications included (1) HpaII tiny fragments locus 9c, which is involved in nucleic acid metabolism, has recently been shown to be associated with a deficit in sustained attention within schizophrenia in a Taiwanese cohort119; (2) protein tyrosine kinase 2, also known as focal adhesion kinase, which is involved in axonal outgrowth120; and (3) SWI/SNF–related, matrix-associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a, member 2, which is involved in cell differentiation and may be involved in the conversion of oligodendrocyte precursor cells to neural stem cells.121

A recent study by Carter122 has demonstrated the importance of the interaction of genes related to the life cycles of pathogens and schizophrenia. Carter examined 245 schizophrenia candidate genes and found that 21% interact with influenza virus, 22% interact with herpes simplex virus 1, 18% interact with cytomegalovirus, 12.6% interact with rubella, and 16% interact with Toxoplasma gondii.122 These percentages suggest a general overrepresentation of pathogen-related genes in the set of schizophrenia candidate genes. These genes code for ligand-activated receptors (fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 [FGFR1]), adhesion molecules (neuronal cell adhesion molecule 1 [NCAM1]), molecules involved with intracellular traffic (DISC1), among others.122 Carter122 suggests that the variability observed in gene association studies may be partly explained by presence/absence of the pathogen that would affect the strength of association.

Brain Pathology

A consistent observation in schizophrenia is the enlargement of the cerebroventricular system. The abnormalities are present at onset of disease, progress slowly,1 and are unrelated to the duration of illness or treatment regimen.10 Additionally, cerebroventicular enlargement distinguishes affected from unaffected discordant monozygotic (MZ) twins. A large number of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies indicate lateral and third ventricular enlargement and widening of cortical fissures and sulci.123 Furthermore, gross brain abnormalities have been identified in DLPFC, hippocampus, cingulate cortex, and superior temporal gyrus.10,124 Some reports also indicate presence of brain structural abnormalities in individuals at high risk for development of schizophrenia and in unaffected first-degree relatives of subjects with schizophrenia.125 More recently, studies of white matter tracts show evidence of disorganization and lack of alignment in white fiber bundles in frontal and temporoparietal brain regions in schizophrenia.126

Numerous reports have documented the presence of various neuropathologic findings in postmortem brains of patients with schizophrenia.127 These findings consist of cortical atrophy, ventricular enlargement, reduced volume of amygdala and parahippocampal gyrus, and cell loss and volume reduction in thalamus.127,128 Several cytoarchitectural studies give credence to the idea of early abnormal laminar organization and orientation of neurons in subjects with schizophrenia including (1) decreased entorhinal cellularity in superficial layers I and II, incomplete clustering of neurons in layer II, and the presence of clusters in deeper layers where they are normally not found129; (2) findings similar to those in the entorhinal cortices in PFC and cingulate cortex127,130,131; and (3) reduced nicotinamide alanine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-diaphorase (NOS)–positive cells (remnants of the embryonic subplate zone) in cortical layers I and II and increased density in deep layers (subcortical white layer or the putative vestigial subplate zone) in DLPFC and hippocampal and lateral temporal cortices.132 Specific regions of the frontal cortex are associated with schizophrenia, most notably the DLPFC (for a review see Bunney and Bunney130) as well as the orbitofrontal cortex, medial PFC, and ventromedial PFC.133–135 Changes in the frontal cortex include abnormal translocation of NADPH-diaphorase–positive cells132 and reduced gray matter volume.136 Hippocampal abnormalities include disturbed cytoarchitecture, abnormal translocation of NADPH-diaphorase–positive cells, and an overall reduction in volume.132,137 A greater prevalence of hippocampal shape anomaly, characterized by a rounded shape, medial location, and a deep collateral sulcus, has been found in familial schizophrenia patients.138 There is also evidence of irregular arrangement of neurons in the entorhinal cortex and disoriented pyramidal cells in CA1–CA3 subfields in subjects with schizophrenia when compared with controls.139,140 Moreover, there is evidence of biochemical changes, including glutamatergic and GABAergic dysfunction in the hippocampus of subjects with schizophrenia.141,220,221 In cerebellum, reduced cell size in Purkinje cells have been observed.127 Structural MRI studies have shown cerebellar atrophy associated with schizophrenia.142–144 More recently, however, a study has shown an increase in cerebellar volume in subjects with schizophrenia.145 Additionally, functional MRI investigations using cognitive tests have demonstrated decreased activation in cerebellum of schizophrenic patients.146–148

Several recent reports using MRI and diffusion tensor imaging have shown reduced white and gray matter diffusion anisotropy in patients with schizophrenia.149–151 In brain white matter, water diffusion is highly anisotropic, with greater diffusion in the direction parallel to axonal tracts. Thus, reduced anisotropy of water diffusion has been proposed to reflect compromised white matter integrity.150 Reductions in white matter anisotropy reflect disrupted white matter connections, which is consistent with the disconnection model of schizophrenia.152 Reduced white matter diffusion anisotropy has been observed in prefrontal, parietooccipital, splenium of corpus callosum, arcuate and uncinate fasiculus corpus callosum, parahippocampal gyri, and deep frontal perigenual regions of schizophrenic patients.150,153–157 It is conceivable that downregulation of genes affecting production of myelin-related proteins, as well as other components of axons, may lay the foundation for white matter abnormalities that develop later in life in subjects who become schizophrenic.98,99 Recently, the dysregulation of white matter metabolites have been observed in elderly patients with schizophrenia.158 Compared with healthy subjects, patients with schizophrenia displayed lower N-acetyl compounds, lower myoinosotol, and higher glutamate and glutamine in white matter regions.158 The authors suggest lower N-acetyl compounds may indicate reduced neuronal content, lower myoinosotol may suggest decreased glial content or dysfunction, while the elevated glutamate and glutamine could be due to excess neuronal release of glutamate or glial dysfunction in glutamate reuptake.149 A more recent study by the same group found that elderly patients with schizophrenia with elevated levels of glutamate and glutamine in white matter had lower negative positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) scores but greater deficits in executive function.159 Table 5 summarizes the findings of selected research articles on brain abnormalities observed in subjects with schizophrenia.

Table 5.

Summary of Selected Brain Abnormalities Observed in Subjects With Schizophrenia

| Study | Brain Region | Method | Pathological Change |

| Northoff et al123 | Ventricles and cerebral cortex | CT | Lateral and third ventricular enlargement and widening of cortical fissures and sulci |

| Davis et al126 | Frontal and temporoparietal regions | MRI | Disorganization and lack of alignment in white fiber bundles |

| Akbarian et al132 | Frontal lobe, DLPFC, hippocampus, and lateral and temporal cortices | Histochemical staining | Abnormal translocation of NADPH-diaphorase–positive cells in DLPFC and hippocampal and lateral temporal cortices |

| Wolf et al136 | Frontal cortex | VBM | Reduced gray matter volume |

| Glantz and Lewis,173 Pierri et al174 | DLPFC | Histochemical staining | Reduction in pyramidal cell spine density and somal volume |

| Weiss et al137 | Hippocampus | MRI | Reduced hippocampal volume |

| Connor et al138 | Hippocampus | MRI | Altered hippocampal shape |

| Arnold et al,139 Luts et al140 | Hippocampus | Histochemical staining | Disoriented pyramidal cells in CA1–CA3 subfields |

| Arnold129 | Entorhinal cortex | Histochemical staining | Decreased cellularity and incomplete or abnormal clustering |

| Arnold and Trojanowski127 | Cerebellum | Histochemical staining | Reduced Purkinje cell size |

| Uematsu et al,142 DeLisi et al,143 Nopoulos et al144 | Cerebellum | MRI | Cerebellar atrophy |

| Goldman et al145 | Cerebellum | MRI | Increased cerebellar volume |

| Ardekani et al150 | Corpus callosum, left superior temporal gyrus, parahippocampal gyri, middle temporal gyri, inferior parietal gyri, medial occipital lobe, and the deep frontal perigenual region | MRI | Reduced fractional anisotropy |

| Kubicki et al151 | Cingulate fasciculus | DTI | Reduced area and fractional anisotropy |

| Buchsbaum et al153 | Prefrontal cortex | MRI | Reduced fractional anisotropy |

| Lim and Helpern149 | Prefrontal cortex and right parietal-occipital region | DTI | Reduced fractional anisotropy |

| Foong et al155 | Corpus callosum | DTI | Reduced fractional anisotropy |

| Agartz et al156 | Splenium of the corpus callosum | DTI | Reduced fractional anisotropy |

| Burns et al157 | Left uncinate fasciculus and left arcuate fasciculus | DTI | Reduced fractional anisotropy |

Note: CT, computed tomagraphy; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; VBM, voxel-based morphometry; DTI, diffusion tensor imaging.

Explanatory Capacity of the Neurodevelopmental Model of Schizophrenia

Epidemiology of Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia affects 1% of the adult population in the world.160 The point prevalence of schizophrenia is about 5/1000 population,161 and the incidence is about 0.2/1000 per year.161 This incidence rate was reported to be comparable in most societies162; however, recent studies suggest greater variability.161 Schizophrenia has an earlier onset in males with mean ages of onset of 20 and 25 years in males and females, respectively.10,161 Reports have indicated, however, that there are no sex differences in the lifetime risk of developing schizophrenia.163 However, a meta-analysis by Aleman et al164 of studies of the incidence of schizophrenia found that overall there was evidence for a sex difference in the risk of developing schizophrenia. Interestingly, in countries with a medium development index, the sex difference was not apparent.164 The authors suggest that factors related to industrialization may play a role.164 While age of first psychotic episode is generally during adolescence, 23.5% of patients with schizophrenia experience their first episode after age 40 years.165–167 The prevalence of early adult onset, following extensive remodeling of the brain circuitry during adolescence, rather than onset evenly distributed by age, lends credence to the neurodevelopmental model.

Heritability of Schizophrenia

Emerging evidence points to schizophrenia as a familial disorder with a complex mode of inheritance and variable expression.10,80,168 While single-gene disorders like Huntington disease have homogenous etiologies, complex-trait disorders like schizophrenia have heterogeneous etiologies emanating from interactions between multiple genes and various environmental insults.80 Twin studies of schizophrenia suggest concordance rates of 45% for MZ twins and 14% for dizygotic twins.10,169 Consistent with this, a recent meta-analytic study showed a heritability of 81% for schizophrenia.169 Despite this high genetic predisposition, an 11% point estimate was suggested for the effects of environmental factors on liability to schizophrenia.80,169 The interaction of genes and the environment (as discussed in “The Neurodevelopmental Theory of Schizophrenia and Supportive Evidence”), particularly in utero is likely to be very important. Additionally, adoption studies show a lifetime prevalence of 9.4% in the adopted-away offspring of schizophrenic parents vs 1.2% in control adoptees.170 The adoption studies also clearly show that postnatal environmental factors do not play a major role in etiology of schizophrenia.80 However, this issue remains controversial and needs to be interpreted carefully in view of the ample support for effects of environment on schizophrenia development.

Drug Abuse and the Development of Schizophrenia

Drug abuse has also been linked to the development of schizophrenia. It has been demonstrated that administration of D-amphetamine (which acts on the dopaminergic tracts) to healthy volunteers leads to production of psychotic symptoms and worsens psychosis in schizophrenic subjects.10 Moreover, heavy cannabis use in adolescence may lead to the development of later schizophrenia and that this is mediated by dopamine.171 However, hallucinogens like lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) or psilocybin (acting on serotonin system) or dissociative anesthetics like ketamine or phencyclidine (acting on glutamate system) also cause psychotic symptoms10,172 suggesting that alterations of the dopaminergic system alone are not solely responsible for the development of schizophrenia.

Pyramidal Cell Abnormalities and Schizophrenia

As mentioned in “The Neurodevelopmental Theory of Schizophrenia and Supportive Evidence,” there are numerous neuroanatomical deficits in the brains of schizophrenic subjects. Glantz and Lewis173 observed that pyramidal cells located in layer III of the DLPFC of subjects with schizophrenia exhibited a 23% reduction in spine density when compared with normal controls suggesting a decrease in excitatory inputs to these cells.173 These same cells also exhibit a 9.2% reduction in somal volume.174 Taken together, the authors conclude that these findings indicate disruption of the thalamocortical and corticocortical circuits.174 As with other alterations including reduced fractional anisotropy of the white matter or altered hippocampal volume or shape, these changes in pyramidal cells suggest neurodevelopmental dysfunction.222

The Role of the Reelin and GABAergic Signaling Systems in Schizophrenia

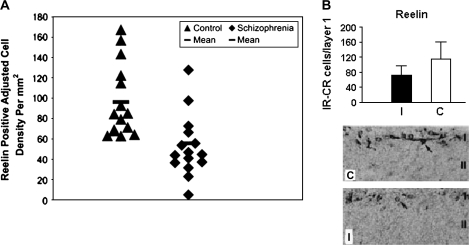

Several studies now implicate the pathological involvement of RELN gene or its protein product in schizophrenia. Reelin helps in normal lamination of the brain during embryogenesis and affects synaptic plasticity in adulthood.5,175,176 Impagnatiello et al177 used northern and western blotting and immunocytochemistry to show reductions in reelin mRNA and protein in cerebellar, hippocampal, and frontal cortices of patients with schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder. Reduction in reelin was associated with significant decreases in GAD67-kDa protein in the same postmortem brains.178 A later immunocytochemical report179 showed significant reductions in reelin immunoreactivity in schizophrenic and bipolar patients. However, these authors detected similar decreases in hippocampal reelin protein levels in nonpsychotic bipolar and depressed subjects, suggesting that reelin deficiency may not be limited to subjects with psychosis alone.179,223 Fatemi et al98 subsequently demonstrated significant reductions in Reelin, as well as GAD65-kDa and GAD 67-kDa proteins, in cerebella of subjects with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression98,180 as well as in mice following prenatal viral infection (figure 3). Further confirmatory data relating to Reelin abnormalities in brains of schizophrenic patients were demonstrated by Eastwood et al,181 who showed a trend for reduction in Reelin mRNA in cerebella of schizophrenic subjects; these reductions in Reelin mRNA correlated negatively with semaphorin 3A. The authors suggested that these findings were consistent with an early neurodevelopmental origin for schizophrenia and that the reciprocal changes in Reelin and semaphorin 3A may be indicative of a mechanism that affects the balance between inhibitory and trophic factors regulating synaptogenesis.181

Reelin is Reduced in Hippocampus of Individuals With Schizophrenia and in Cerebral Cortex Following Prenatal Viral Infection. A. The values expressed on the y-axis are reelin-positive adjusted cell densities per square millimeter localized to hippocampal CA4 areas in control and schizophrenic subjects. The number of brains used is 15 (control) and 15 (schizophrenic). Each point is the mean for 2–4 sections analyzed per brain. A crossbar localized over each scatter plot represents mean Reelin-positive adjusted cell density value per group. Mean values for schizophrenic subjects are significantly reduced when compared with control values (analysis of variance, P < .05). B. The top panel shows a graph depicting the hemispheric Reelin-positive Cajal-Retzius (CR) cell counts in layer I of the cortex of prenatally infected (I) and sham-infected control (C) animals. The number of Reelin-positive CR cells was significantly reduced in infected brains compared with control brains (P < .0001). The lower panel shows light micrographs of layer I–II in coronal sections of prenatally infected and sham-infected cortex. Originally published in Fatemi et al.67,179

Effects of Various Antipsychotics on Brain Genes Involved in Neurodevelopment of Schizophrenia

Pharmacotherapy is the primary mode of treatment for the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia. All drugs currently used to treat schizophrenia mediate their actions through the dopamine D2 receptor.182 With the exception of aripiprazole, which acts as a partial agonist, both typical and atypical antipsychotics are antagonists of the D2 receptor.183–185 Dopamine hyperactivity may contribute to psychotic symptoms and that dopamine antagonists like chlorpromazine treat the psychotic symptoms.10

Clozapine is a dibenzodiazepine and the prototype for most of atypical antipsychotics (agents that may treat positive, negative, or cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia have decreased liability for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and tardive dyskinesia [TD], may be effective for a proportion of treatment-nonresponsive patients and exhibit greater 5HT2 over D2 receptor antagonism and do not cause hyperprolactinema).186,187 Clozapine has been shown to be effective in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.188 Thus, clozapine remains the only antipsychotic agent to date that is Food and Drug Administration approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.189 Additionally, other studies have shown superiority of clozapine vs typical agents in treatment of total psychopathology, EPS, and TD and categorical response to treatment.124 Clozapine reduces positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia without causation of EPS, TD, or hyperprolactinemia.10 Additionally, clozapine has been shown to reduce depression and suicidality.10,124

The time course over which antipsychotic agents take effect is variable. In an analysis of studies measuring antipsychotic response during the first 4 weeks of treatment, Agid et al190 found that there was a reduction in total scores of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) of 13.8% during week 1, 8.1% during week 2, 4.2% during week 3, and 4.7% during week 4. The authors hold that these results reject the “delayed onset” model of antipsychotic action; rather, antipsychotic response begins within the first week and accumulates over time.190 However, Emsley et al,191 using a benchmark of a 20% improvement in total score on the PANSS for clinical response, found that 22.5% of subjects with first-episode schizophrenia did not achieve clinical response until 4 weeks of treatment or later. Taken together, these studies demonstrate the variability of time to antipsychotic response.

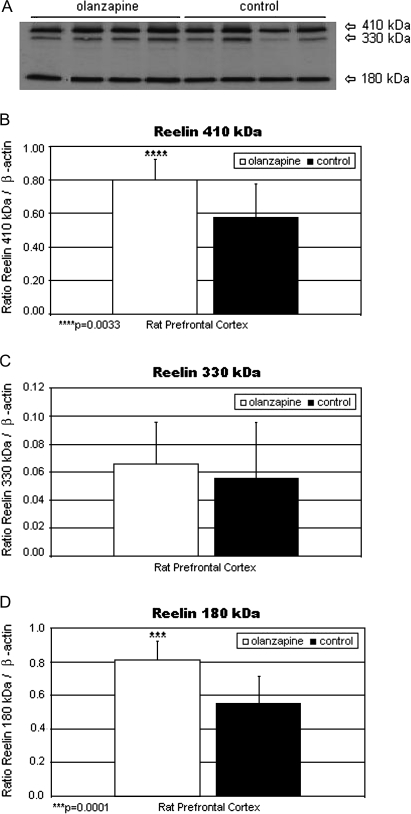

It has been hypothesized that antipsychotic agents affect various brain genes, leading to changes in synaptic structure and function that may underlie clinical response.192 Olanzapine is a second-generation antipsychotic agent that, like clozapine, exhibits greater 5HT2A than D2 antagonism193 but does not share clozapine's propensity for agranulocytosis. One of the important genes upregulated by chronic olanzapine treatment is Reln88 (figure 4). Recent reports show that Reelin receptor, apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2), interacts with and alters, the conformation of NMDA receptors, NR2A and NR2B.175 Additionally, Reelin induces tyrosine phosphorylation of NR2A and NR2B receptors in hippocampal tissue,175 thus modulating NMDA receptor activity and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Supporting evidence for the potential role of olanzapine in enhancing neuroplasticity was recently shown by Lieberman et al,194 who demonstrated a cessation of brain gray matter loss in brains of patients with schizophrenia that were treated with olanzapine for 12 weeks and not in those treated for the same time period with haloperidol. Additionally, Wang and Deutch195 have also shown that olanzapine prevented decreases in spine density of basilar dendrites on layers II, III, and IV of PFC pyramidal neurons in rats lesioned with 6-hydroxydopamine. Finally, olanzapine, but not haloperidol, increased expression of the polysialilated form of neural cell adhesion molecule in rat PFC, suggesting a possible role for this molecule in the efficacy of olanzapine.196 NCAM appears early in development and is important during brain morphogenesis.

(A) Reelin Bands of 410, 330, and 180 kDa From the Prefrontal Cortex Homogenates (70 μg protein per lane) of Representative Olanzapine-Treated and Control Rats Are Shown. Mean Reelin 410 (B), 330 (C), and 180 (D) kDa/β-actin ratios for olanzapine-treated (filled histogram bars) and control rats (unfilled histogram bars) are shown. Levels of Reelin 410 kDa/β-actin (B) and Reelin 180 kDa/β-actin (D) were significantly increased vs controls (P = .0033 and .0001, respectively). Reelin 330 kDa/β-actin (C) was nonsignificantly increased vs controls. Origianlly published in Fatemi et al.88

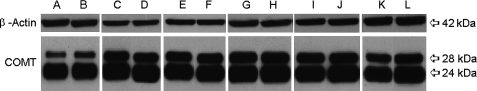

In recent years, COMT has drawn much interest as a modulator of PFC function, cognitive abilities, and the genetic disposition toward schizophrenia. COMT metabolizes catecholamines197 and is known to modulate dopamine levels in the PFC.198,199 Recently, our laboratory200 conducted experiments testing a number of atypical antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and antidepressants (clozapine, fluoxetine, haloperidol, lithium, olanzapine, and valproic acid [VPA]) to investigate which genes and proteins were affected by chronic treatment of the above agents. Rats were randomly assigned to 1 of the 6 drug groups or sterile saline and administered drug or diluent for 21 days. Microarray results showed a significant (P <

< .05), 2-fold decrease in COMT in PFC in all drug-treatment groups (except for olanzapine) when compared with controls. Protein levels for the 28-kDa membrane-bound isoform of COMT were significantly downregulated in VPA-treated PFC (P = .0073)200 (figure 5). Protein levels for the 240kDa cytosolic isoform of COMT were significantly downregulated in PFC by clozapine (P = .014), lithium (P = .0006), olanzapine (P = .046), and VPA (P = .0073) and were significantly upregulated by fluoxetine (P = .0063) 200 (figure 5). In summary, as is evident (vide supra), various antipsychotics exert their clinical actions not only through classical neurotransmitters but also via numerous brain genes that may explain the variable course of clinical response. Some of these genes may also be involved in etiology of schizophrenia (e.g. Reelin).

.05), 2-fold decrease in COMT in PFC in all drug-treatment groups (except for olanzapine) when compared with controls. Protein levels for the 28-kDa membrane-bound isoform of COMT were significantly downregulated in VPA-treated PFC (P = .0073)200 (figure 5). Protein levels for the 240kDa cytosolic isoform of COMT were significantly downregulated in PFC by clozapine (P = .014), lithium (P = .0006), olanzapine (P = .046), and VPA (P = .0073) and were significantly upregulated by fluoxetine (P = .0063) 200 (figure 5). In summary, as is evident (vide supra), various antipsychotics exert their clinical actions not only through classical neurotransmitters but also via numerous brain genes that may explain the variable course of clinical response. Some of these genes may also be involved in etiology of schizophrenia (e.g. Reelin).

Effects of Psychotropic Agents on Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (COMT) Expression in Rat Frontal Cortex. A, C, E, G, I, and K correspond to protein levels from frontal cortices of clozapine-, fluoxetine-, haloperidol-, lithium-, olanzapine-, and sodium valproate–treated rat brains, respectively. B, D, F, H, J, and L correspond to protein levels from frontal cortices of saline-treated rat brains, respectively. Originally published in Fatemi and Folsom200.

Evidence in Support of Other Models of Schizophrenia

In addition to the neurodevelopmental model, there are alternative models that have been used to explain the etiology of schizophrenia. It is likely that due to the heterogeneous nature of schizophrenia that multiple factors interact to produce the disease state such as disruptions in the dopaminergic, serotonergic, and glutamatergic systems as well as neurodegenerative changes. With regard to epidemiology, a number of social factors have been shown to increase the risk of schizophrenia including urban birth and upbringing,201 quality of maternal-child relationship,202,203 and migration204, a risk that increases when the immigrant group is a small minority indicating that isolation and lack of support may be important factors. An alternative explanation, however, may be that urban birth and migration may well be consistent with the neurodevelopmental hypothesis in that these represent, respectively, an environment in which one is exposed to more pathogens and an environment in which one may have not developed native antibodies or other resistances to pathogens. Abuse of drugs that affect the dopaminergic (amphetamine, cannabis), glutamatergic (PCP), or serotonergic (LSD) systems also may lead to psychotic symptoms and the development of schizophrenia. While many brain imaging and postmortem studies have yielded structural differences between subjects with schizophrenia and healthy controls, there are other reports showing no differences between schizophrenic patients and controls.205 Moreover, there is debate as to whether the observed changes represent developmental or neurodegenerative changes or the result of antipsychotic medications.206

Critics of the neurodevelopmental model claim that it does not fully account for a number of features of schizophrenia, including the long gap between neurodevelopmental insult and the development of symptoms, the progressive clinical deterioration observed in some patients, and evidence of progressive changes in certain ventricular and cortical brain structures.1,207–209 Longitudinal studies have demonstrated evidence of an increase in ventricular volume over a period of 2–4 years among first-episode patients.143,210 Moreover, a decline in frontal lobe volume and posterior superior temporal gray matter volume over a period of 4 years has been reported in patients with chronic schizophrenia.211 A mechanism to explain the progressive elements of schizophrenia is apoptosis, or programmed cell death (reviewed by Jarskog et al212), especially synaptic apoptosis in which apoptosis is localized to distal neurites without inducing immediate neuronal death.213 In a series of studies of postmortem temporal cortex, Jarskog et al214 found reduced expression of Bcl-2, a molecule that protects against apoptosis, in schizophrenic brains. A further study showed that the ratio of proapoptotic molecule Bax to Bcl-2 was increased in the same region, suggesting that these neurons were receptive to apoptotic stimuli.215 Interestingly, caspase 3, the caspase molecule most associated with apoptosis in the CNS215 is not upregulated in temporal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia,216 suggesting that chronic apoptosis is not taking place, in contrast to classic neurodegenerative disorders.216 The vulnerability of neurons to proapoptotic insults such as oxidative stress and glutamate excitotoxicity could lead to selective dendritic and synaptic losses observed with schizophrenia.212,222 However, the neurodegenerative model has been critiqued by Weinberger and McClure.206 The authors point out that there is a lack of expression of genes involved with DNA fragmentation and response to injury from postmortem studies.206 Moreover, longitudinal studies of cognitive function, which would serve as a measure of cortical neuronal system integrity, do not support a progression of loss of function that would be expected by the neurodegenerative hypothesis.218

A means to test for alternate theories to the neurodevelopmental model is through our animal model of prenatal viral infection. Longitudinal studies, in which animals are infected at specific gestational periods and then followed through late adulthood, with brains collected at specific postnatal time points, could help establish whether alternate models are valid. If important genes that have been linked to schizophrenia are not affected at early time points such as birth, childhood, adolescence, or early adulthood but are only turned on or off in mid-late adulthood, it would provide evidence against the neurodevelopmental model. Brain imaging experiments on animals from the same studies could help establish whether there is analagous progressive changes in ventricular or cortical structures observed in subjects with schizophrenia, providing evidence for the neurodegenerative model.

Conclusions

The vast majority of evidence supports a neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia genesis. Evidence from genetic studies suggest a high degree of heritability of schizophrenia and point to a number of potential candidate genes that may be perturbed early in development leading ultimately to the development of psychotic symptoms. Genes involved with cell migration, cell proliferation, axonal outgrowth, myelination, synaptogenesis, and apoptosis are affected in subjects with schizophrenia, pointing to neurodevelopmental insults. Imaging studies have shown differences between the brains of subjects with schizophrenia and normal controls in a number of brain regions including the PFC, cerebellum, hippocampus, and amygdala. There is strong evidence from epidemiological studies and animal models that viral infection during pregnancy increases the risk for schizophrenia in the offspring. The presence of neurological soft signs in children who later develop schizophrenia also points to a neurodevelopmental etiology of schizophrenia.

Funding

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5R01-HD046589-04 to S.H.F.); Stanley Medical Research Institute (02R-232 to S.H.F.).

References

Articles from Schizophrenia Bulletin are provided here courtesy of Oxford University Press

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbn187

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://academic.oup.com/schizophreniabulletin/article-pdf/35/3/528/5293097/sbn187.pdf

Free after 12 months at schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org

http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/35/3/528

Free after 12 months at schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org

http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/35/3/528.pdf

Free to read at schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org

http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/35/3/528

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1093/schbul/sbn187

Article citations

Developmental Predictors of Suicidality in Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review.

Brain Sci, 14(10):995, 30 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39452009 | PMCID: PMC11506348

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Deep Learning-based Brain Age Prediction in Patients With Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders.

Schizophr Bull, 50(4):804-814, 01 Jul 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38085061

Natural Language Processing and Schizophrenia: A Scoping Review of Uses and Challenges.

J Pers Med, 14(7):744, 12 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39063998 | PMCID: PMC11278236

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

A novel blood-based epigenetic biosignature in first-episode schizophrenia patients through automated machine learning.

Transl Psychiatry, 14(1):257, 17 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38886359 | PMCID: PMC11183091

Mutual effects of gestational diabetes and schizophrenia: how can one promote the other?: A review.

Medicine (Baltimore), 103(25):e38677, 01 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38905391 | PMCID: PMC11191934

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (419) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: version III--the final common pathway.

Schizophr Bull, 35(3):549-562, 26 Mar 2009

Cited by: 1310 articles | PMID: 19325164 | PMCID: PMC2669582

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

[Schizophrenia and cognition: a neurodevelopmental approach].

Encephale, 37 Suppl 2:S133-6, 01 Dec 2011

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 22212843

Review

The neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: update 2005.

Mol Psychiatry, 10(5):434-449, 01 May 2005

Cited by: 510 articles | PMID: 15700048

Review

[Neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia].

Encephale, 32(5 pt 4):S879-82; discussion S883, 01 Oct 2006

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 17119493

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NICHD NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: 5R01-HD046589-04