Abstract

Free full text

Lateral microtubule bundles promote chromosome alignment during acentrosomal oocyte meiosis

Abstract

Although centrosomes serve to organize microtubules in most cell types, oocyte spindles form and mediate meiotic chromosome segregation in their absence. Here, we use high-resolution imaging of both bipolar and experimentally-generated monopolar spindles in C. elegans to reveal a surprising organization of microtubules and chromosomes within acentrosomal structures. We find that homologous chromosome pairs (bivalents) are surrounded by microtubule bundles running along their sides, whereas microtubule density is extremely low at chromosome ends despite a concentration of kinetochore proteins on those regions. Further, we find that the chromokinesin KLP-19 is targeted to a ring around the center of each bivalent and provides a polar ejection force required for congression. Together, these observations create a new picture of chromosome/microtubule association in acentrosomal spindles and reveal a mechanism by which metaphase alignment can be achieved utilizing this organization. Specifically, we propose that: 1) Ensheathment by lateral microtubule bundles places spatial constraints on the chromosomes, thereby promoting biorientation, and 2) Localized motors mediate movement along these bundles, thereby promoting alignment.

In mitotically-dividing cells, duplicated centrosomes are used as structural cues to define and organize the spindle poles. These centrosomes nucleate microtubules that capture the sister kinetochores of each chromosome, facilitating chromosome biorientation and congression1. In contrast, during meiosis in female animals the centrosomes are degraded prior to the meiotic divisions, and therefore oocyte spindles form in their absence. How these spindles are organized and the mechanisms by which chromosomes become bioriented and align are poorly understood. We are using C. elegans oocyte meiosis as an in vivo model for investigating these mechanisms.

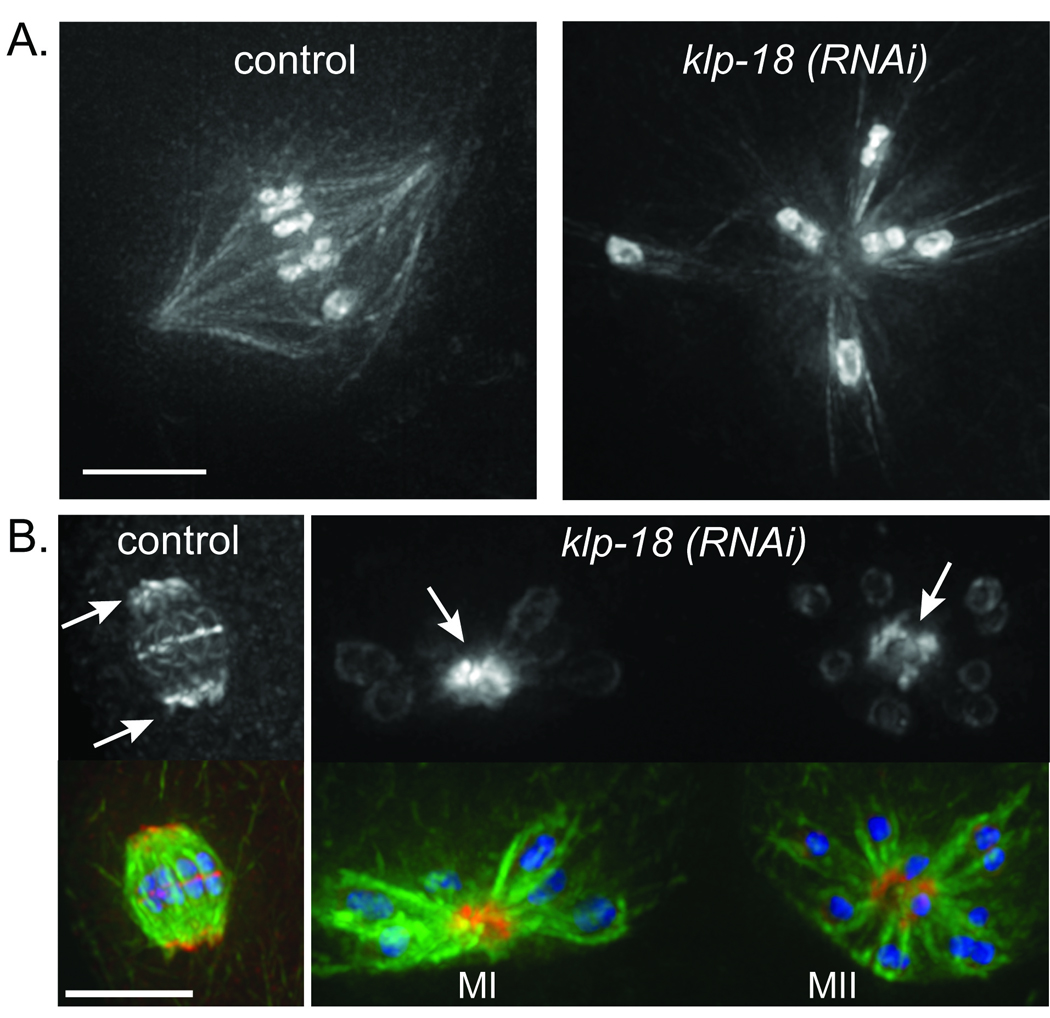

In the course of an RNAi screen designed to identify factors involved in the assembly of the oocyte spindle (Fig. S1 and Supplementary Information), we identified two proteins required for acentrosomal spindle bipolarity. Depletion of either KLP-18 (Kinesin-12 family) or a novel protein, C28C12.2 (which we named meiotic spindle 1, or MESP-1), resulted in the formation of aster-like microtubule arrays (Fig. 1A, ,2A);2A); we demonstrated that these asters were monopolar spindles using an antibody against ASPM-1 as a pole marker (Fig. 1B, S2). The ability to induce monopolar acentrosomal spindles in vivo represents a powerful experimental tool, as analogous approaches have proven valuable for investigating the function of centrosome-containing spindles2–4. In the present study, we have exploited this tool to probe acentrosomal spindle organization.

KLP-18 and MESP-1 are required for the bipolarity of acentrosomal oocyte meiotic spindles. (a) Microtubule arrays formed in live worms expressing GFP::tubulin and GFP::histone. Left, a bipolar spindle formed during oocyte meiosis in a control worm. Right, an astral microtubule array formed in a klp-18(RNAi) embryo. (b) Images of fixed oocyte spindles stained for tubulin (green), DNA (blue) and the spindle pole marker ASPM-1 (red). ASPM-1 (top row) concentrates at the poles of the control oocyte spindle (arrows, left image) and marks the centers of the microtubule asters formed following klp-18(RNAi) (arrows, right image) in both MI and MII. (Additional signal from the ASPM-1 antibody is also seen associated with chromosomes, but this staining is not depleted by aspm-1(RNAi); Fig. S2). Scale bars, 5 µm.

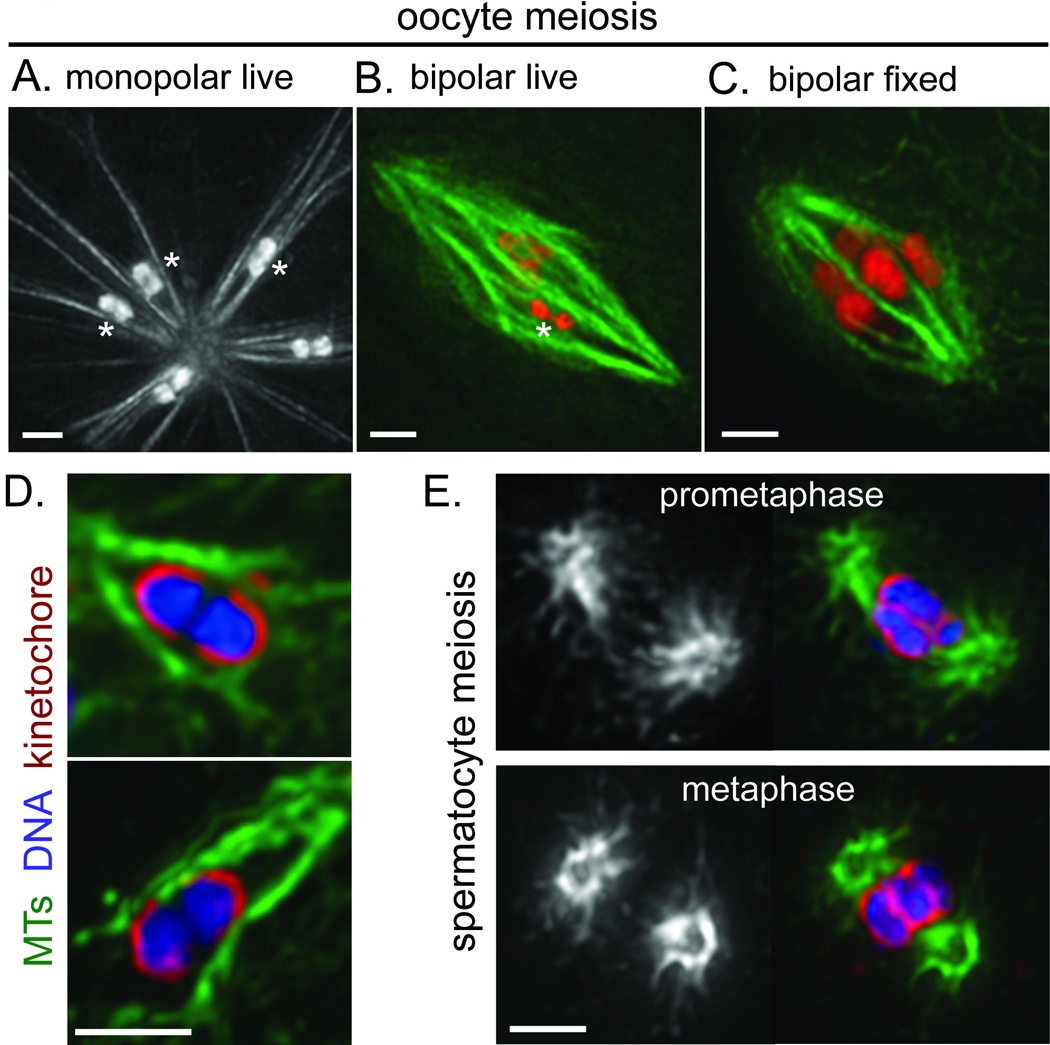

Chromosomes are ensheathed by lateral microtubule bundles in acentrosomal spindles. Images in a–c are partial projections of 3D stacks that highlight the nature of the interactions between microtubules and individual bivalents: specifically, microtubule bundles associate laterally with the bivalents, and microtubule density is low near bivalent ends. When multiple chromosomes are displayed in the same image, asterisks mark bivalents where this organization is most evident in the image frames chosen. (a) Monopolar spindle formed following mesp-1(RNAi), imaged in a live worm expressing GFP::tubulin and GFP::histone. (b) Live image of a bipolar oocyte meiotic spindle in a worm expressing GFP::tubulin (green) and mCherry::histone (red). (c) Image of a bipolar oocyte spindle fixed and stained for DNA (Hoechst; Red) and tubulin (green). (d) Close-up images of bivalents in monopolar spindles formed following klp-18(RNAi), stained for tubulin (green), DNA (blue), and the kinetochore protein KNL-3 (red). Kinetochore proteins form cup-like structures around the bivalents7,8. Microtubule density is low at the ends of the bivalents, despite a concentration of kinetochore proteins in those regions. (e) Prometaphase (top) and metaphase (bottom) centrosome-containing spindles formed during spermatocyte meiosis. Images on the right show DNA (Hoechst; blue), tubulin (green) and KNL-3 (red); tubulin alone is shown on the left. In contrast to oocyte meiosis, high microtubule density is observed adjacent to kinetochores at chromosome ends, and microtubule density is low at the centers of the spindles. Scale bars, 2 µm.

High-resolution imaging of monopolar oocyte spindles uncovered a striking and unexpected feature of chromosome/microtubule organization. Specifically, live imaging of GFP::tubulin and GFP::histone revealed that robust microtubule bundles run along the sides of and surround each of the 6 bivalents, whereas microtubule density is extremely low at the ends of the chromosomes (Fig. 2A). This organization is especially evident when examining a Z-stack of images and focusing on the focal planes immediately surrounding each bivalent (Movie S1). While it is possible that a relatively small number of microtubules contact the bivalent ends, by quantifying pixel intensities we measured up to a 60-fold higher density in the ensheathing microtubule bundles compared to the intervening region adjacent to the bivalent end (Fig. S3). This striking difference indicates that lateral microtubule bundles ensheathing the chromosomes are a predominant feature of acentrosomal spindle organization. The same organization was observed in meiosis II monopolar spindles, which contain 12 individual chromosomes since homologues separate in MI but a polar body does not form5 (Fig. 1B). Importantly, chromosomes on monopolar spindles were oriented such that their long axes were parallel to the microtubule bundles (Fig. S4A). This organization results in an arrangement in which homologues (in MI) or sister chromatids (in MII) are pointed in opposite directions, apparently constrained by the microtubule bundles that ensheath them.

While these features of spindle organization were first detected in monopolar spindles, they were also observed in bipolar oocyte spindles. Prometaphase and metaphase spindles were imaged live using a strain expressing GFP::tubulin and mCherry::histone (Fig. 2B, Movie S2), and also in fixed embryos (Fig. 2C). In both cases, we observed microtubule bundles ensheathing the chromosomes and a dearth of microtubule density at chromosome ends. These findings indicate that lateral associations of microtubules with chromosomes predominate in C. elegans acentrosomal oocyte spindles during prometaphase and metaphase. Interestingly, parallel microtubule bundles also surrounded the chromosomes at earlier stages, before a bipolar spindle was apparent (data not shown). This observation indicates that ensheathment by microtubule bundles can constrain chromosome orientation as spindles are forming, so that when bundles align in the plane of the spindle to establish bipolarity, the chromosomes will naturally biorient. (In this context, biorientation refers to an arrangement in which chromosomes are oriented axially on the spindle such that the homologues (MI) or sister chromatids (MII) are pointing towards opposite spindle poles6.) Thus, laterally-associated microtubule bundles could serve both as a major mode of chromosome association with the spindle and as a mechanism for placing spatial constraints on the chromosomes that facilitate biorientation.

Imaging of C. elegans holocentric kinetochores during oocyte meiosis revealed an abundance of kinetochore proteins surrounding the ends of the bivalents7, 8 in regions where microtubule density was very low (Fig. 2D). In contrast, centrosome-containing male meiotic spindles had regions of high microtubule density immediately adjacent to the kinetochores at chromosome ends during prometaphase and metaphase (Fig. 2E, S5), suggesting that kinetochore/microtubule end interactions are abundant during these stages in spermatocyte meiosis. Further, whereas oocyte spindles have regions of high microtubule density extending across their centers (23/23 spindles analyzed), we find a paucity of microtubule density at the centers of spermatocyte spindles (Fig. 2E, S5; 27/28 spindles analyzed) that is consistent with a substantial fraction of microtubules terminating at the chromosomes. These contrasts suggest that acentrosomal and centrosome-containing meiotic spindles differ with respect to the predominant mode of chromosome association with spindle microtubules. Further, the striking difference in microtubule density adjacent to kinetochores suggests that a substantial portion of the kinetochore material on oocyte bivalents may not support microtubule attachments during chromosome congression.

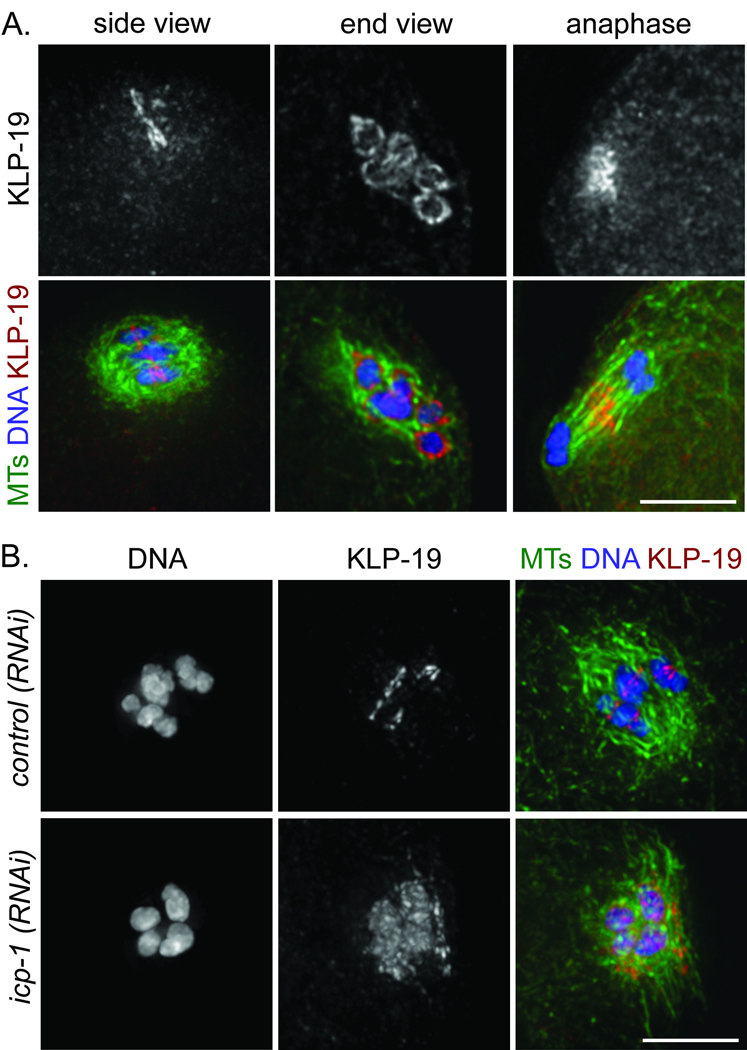

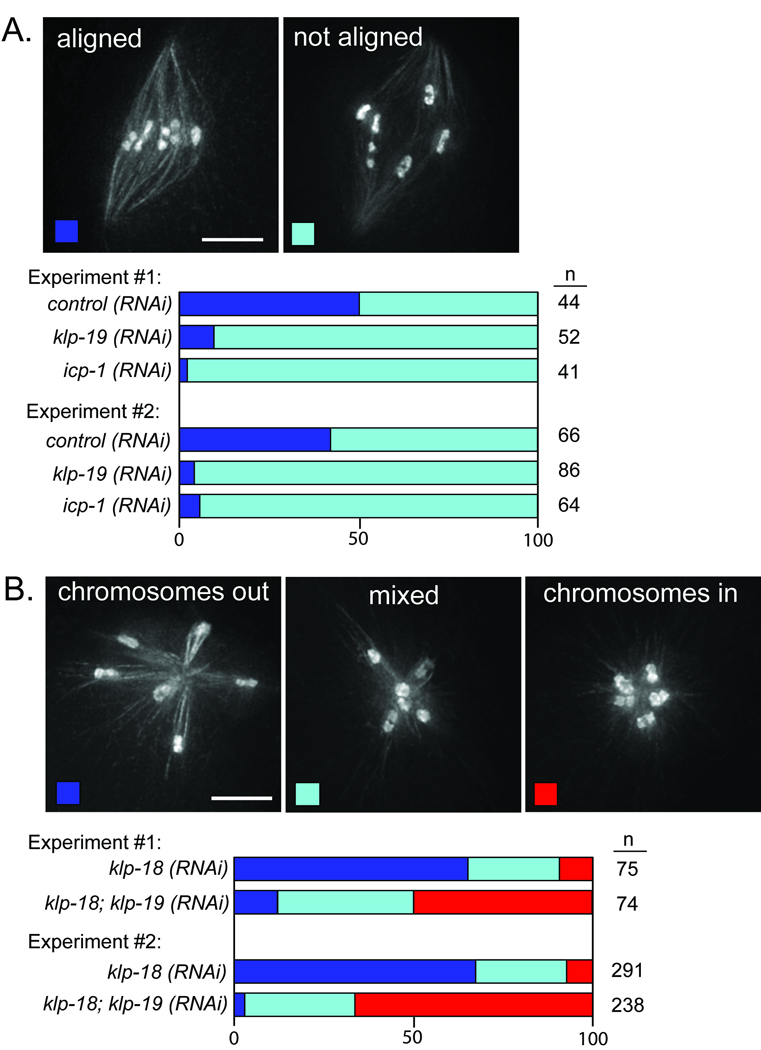

These findings raised the question of how chromosomes align on acentrosomal spindles, since classic models of congression emphasize a contribution from forces provided by dynamic microtubules embedded in kinetochores1. Given the low density of microtubules at chromosome ends, we hypothesized that chromokinesins (which also contribute to congression during mitosis9,) might provide a driving force to move chromosomes along lateral microtubule bundles. We focused on KLP-19, as it provides a polar ejection force to push chromosomes towards the metaphase plate during mitosis and localizes to the mid-bivalent (where homologues are connected by chiasmata) during meiosis I10. High-resolution imaging of KLP-19 on prometaphase/metaphase oocyte spindles revealed that it forms a ring around the center of each bivalent (in MI) and around the sister chromatid interface (in MII) (Fig. 3A and data not shown). Since these domains ultimately align at the metaphase plate, localization of KLP-19 to a ring around these regions makes it a good candidate to promote congression through interaction with the microtubule bundles surrounding the chromosomes. To assess affects on chromosome alignment we utilized a strain containing a temperature-sensitive mutation affecting the anaphase promoting complex (APC) to enrich for metaphase I spindles. Although KLP-19 depletion did not prevent ensheathment of bivalents by microtubule bundles or cause chromosome orientation defects (Fig. S4B), we observed severe defects in metaphase alignment (Fig. 4A), indicating a role for this chromokinesin in congression. Further, depletion of KLP-19 on monopolar oocyte spindles (generated by KLP-18 depletion) caused the bivalents to be found closer to the center of each aster (Fig. 4B), indicating that KLP-19 provides a polar ejection force to move chromosomes towards microtubule plus ends. These findings support the hypothesis that KLP-19 contributes to congression on acentrosomal spindles by providing a polar ejection force to move chromosomes along lateral microtubule bundles towards the metaphase plate.

Localization of the chromokinesin KLP-19 in a ring at the mid-bivalent is regulated by the chromosome passenger complex. All images show oocyte spindles stained for tubulin (green), DNA (blue), and KLP-19 (red). (a) Imaging of KLP-19 localization during wildtype oocyte meiosis. Left, side view of a metaphase I spindle, showing that KLP-19 is concentrated at the mid-bivalent. Middle, end view of a prometaphase I spindle, showing that KLP-19 forms rings around the chromosomes. Right, side view of an anaphase I spindle, showing that KLP-19 is no longer associated with chromosomes and instead is localized to the central spindle. (b) KLP-19 localization is disrupted following depletion of the chromosome passenger complex component ICP-1. Whereas KLP-19 is concentrated at the mid-bivalent following control(RNAi), KLP-19 spreads all over the chromosomes and partially onto the spindle following icp-1(RNAi). Scale bars, 5 µm.

KLP-19 provides a polar ejection force to position meiotic chromosomes. (a) Chromosome alignment was quantified in worms expressing GFP::tubulin; GFP::histone and arrested at metaphase of meiosis I. Images show examples of oocyte spindles with aligned (left) and unaligned (right) chromosomes; stacked bar graphs depict the percentages of bipolar spindles examined that had the indicated configuration of chromosomes. klp-19(RNAi) and icp-1(RNAi) cause an increase in spindles with unaligned chromosomes (p>0.0001 using Fisher exact test). (b) The positions of chromosomes on monopolar spindles were quantified in worms expressing GFP::tubulin; GFP::histone and arrested at metaphase of meiosis I. Images show examples of monopolar spindles with all of the chromosomes out (left), all in (right), or with a mixed population (middle); stacked bar graphs depict percentages of monopolar spindles with the indicated configuration of chromosomes. KLP-19 depletion results in an increase in structures where the chromosomes are found closer to the center of the asters (p>0.0001 using Chi Square test). Scale bars, 5 µm.

Given that chromokinesins associate broadly with non-kinetochore chromatin during mitosis9,10, our finding that KLP-19 is concentrated in a mid-bivalent ring during meiosis led us to speculate that targeting of KLP-19 to this location may be important for its activity or regulation. Since the chromosome passenger complex (CPC) was previously shown to localize to the mid-bivalent (MI) and at the sister chromatid interface (MII)11–15, we assessed the relationship between this complex and KLP-19. The CPC consists of AIR-2 (Aurora B), ICP-1 (INCENP), BIR-1 and CSC-1. Similar to KLP-19, CPC proteins localize to a ring around the center of the chromosomes during prometaphase/metaphase of meiosis I and II (Fig. S6A,B; M. Schvarzstein and A.M.V. unpublished data). Moreover, KLP-19 relocalized to the central spindle during anaphase I and II (Fig. 3A and data not shown), as was previously shown for the CPC. To determine whether KLP-19 localization is CPC-dependent, we depleted ICP-1 by RNAi, which causes removal of AIR-216 (Fig. S6C) and other CPC components15 from chromosomes. Under these conditions, KLP-19 spread all over the chromosomes and partially onto the spindle (Fig. 3B) and we observed severe chromosome congression defects, similar to those elicited by klp-19(RNAi) (Fig. 4A). These results indicate that the CPC is required to restrict KLP-19 to the rings around meiotic chromosomes. Further, although it is possible that the CPC contributes to chromosome alignment in other ways, these findings are consistent with the hypothesis that concentration of KLP-19 into this ring configuration is required for proper congression.

Taken together, our data support a model in which chromosome congression on the C. elegans acentrosomal oocyte spindle is driven primarily by movement of chromosomes along laterally-associated microtubule bundles. In this model (Fig. 5), ensheathment of chromosomes by microtubule bundles imposes spatial constraints that result in biorientation. Further, plus-end directed motors targeted to the mid-bivalent during MI (or to the sister-chromatid interface during MII) interact with antiparallel microtubule bundles in the spindle. In principle, metaphase alignment could be achieved in this context primarily by attaining a balance of anti-poleward forces driving chromosomes towards the plus ends of these overlapping bundles. However, it is likely that opposing poleward forces also operate at this stage, since chromosomes are not ejected from monopolar spindles (where microtubule plus ends are oriented towards the outside). Given the predominance of lateral microtubule/chromosome associations in acentrosomal spindles, we suggest that such poleward forces may also be mediated through lateral interactions.

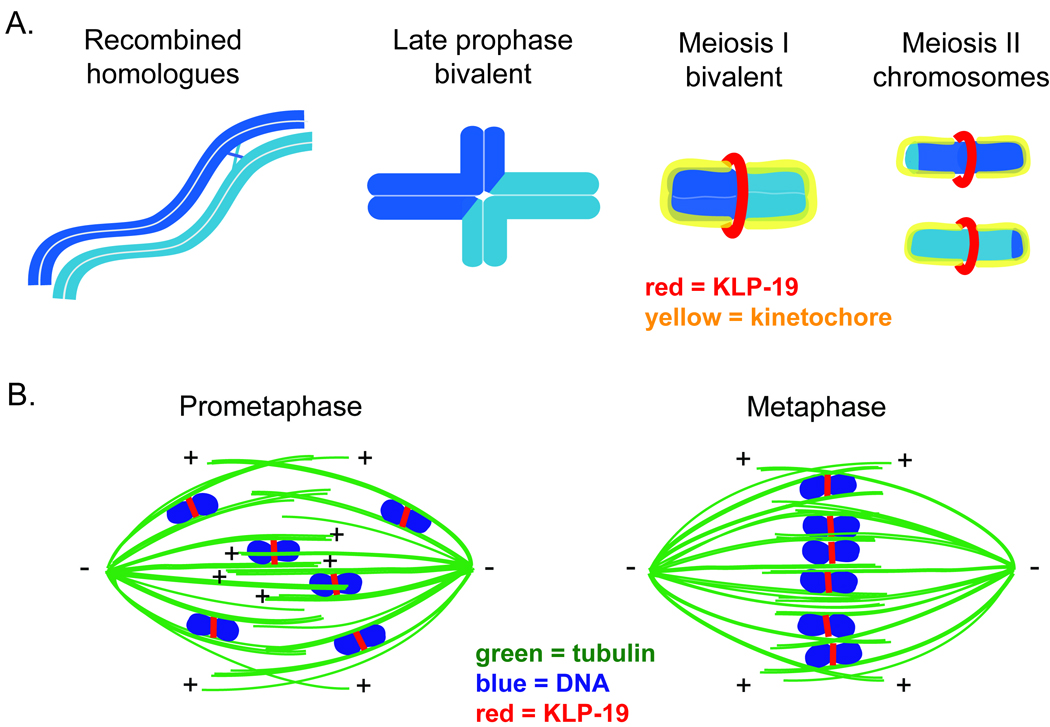

Model. (a) Schematic of chromosome organization during C. elegans meiosis. A pair of homologous chromosomes is depicted in light and dark blue. During mid-prophase, a single crossover recombination event occurs between parallel-aligned homologues (far left). During late prophase, the chromosomes condense and reorganize into a cruciform bivalent structure in which the homologues are linked by a chiasma, a structure resulting from the crossover in combination with sister chromatid cohesion (middle-left); since the crossover usually occurs at an off-center position, the bivalent contains long and short arms. Prior to the initiation of the meiotic divisions, the bivalent condenses further (making the short arms difficult to distinguish) and the holocentric kinetochore (depicted in yellow) forms around each half of the bivalent (middle-right). By prometaphase, KLP-19 (depicted in red) forms a ring around the center of the bivalent. In Meiosis II, the homologues are separate (far right). The kinetochore forms around each sister chromatid, and KLP-19 forms a ring at the interface between the sisters. (b) Model of chromosome congression on acentrosomal spindles. Parallel microtubule bundles ensheath meiotic chromosomes, promoting biorientation. KLP-19 (red) forms a ring around these chromosomes and provides a force to move them along lateral microtubule bundles towards microtubule plus ends. Chromosomes align at the metaphase plate by achieving a balance of forces resulting from lateral associations of chromosomes with overlapping antiparallel microtubule bundles associated with opposite spindle poles. The regions of the chromosomes around which KLP-19 forms a ring during prometaphase and metaphase are the domains where sister chromatid cohesion will be released at the corresponding meiotic division. This localization of congression-promoting motors ensures that these chromosomal domains will be aligned on the metaphase plate, thereby promoting homologue segregation (at anaphase I) or sister chromatid segregation (at anaphase II).

Several features of the proposed mechanisms by which lateral microtubule interactions promote chromosome alignment during oocyte meiosis are quite distinct from the ways in which lateral associations aid biorientation and congression during mitosis. During mitotic prometaphase in yeast17 and vertebrate cells18–20, kinetochores initially associate with the lateral surfaces of microtubules and these associations can then be converted into end-on attachments. Additionally, when a chromosome is mono-oriented in mammalian cells, movement of the chromosome towards the metaphase plate along the sides of microtubules can promote capture of the unattached kinetochore by microtubules emanating from the opposite pole, resulting in biorientation21. In contrast, acentrosomal spindles form and must achieve biorientation and congression in the absence of pre-defined spindle poles and therefore a “search and capture” strategy is not thought to be employed1. Instead, we propose that lateral associations play several roles that together promote chromosome alignment. First, ensheathment of chromosomes between parallel microtubule bundles promotes biorientation by constraining the orientation of meiotic chromosomes such that homologous chromosomes (MI) or sister chromatids (MII) point in opposite directions, even in the context of monopolar spindles (where bipolar tension is not applied to the bivalents). Further, targeting of motors involved in congression to the domains where cohesion will be released during the meiotic divisions ensures that these regions will be aligned on the metaphase plate, thereby promoting accurate chromosome segregation. An important feature of this model that distinguishes it from models involving centrosome-containing spindles is that it does not require either capture of kinetochores by microtubule ends or forces generated by microtubules associated with chromosome ends to achieve chromosome biorientation or congression.

Although our model provides a mechanism by which chromosomes can orient and align without a requirement for kinetochore/microtubule end attachments, it is possible that kinetochore proteins located on the sides of the bivalent do contribute to the ensheathment of chromosomes by lateral microtubule bundles. Consistent with this possibility, depletion of kinetochore components during oocyte meiosis causes defects in bivalent orientation (J. Dumont and A. Desai, personal communication). A potential involvement of kinetochore proteins in mediating lateral associations is compatible with our model, however, as such interactions could promote chromosome ensheathment and orientation even in the absence of spindle bipolarity.

The view of chromosome/microtubule organization that has emerged from our analysis of C. elegans oocyte meiosis is likely to be relevant for acentrosomal spindles in general. Images of wildtype and mutant oocyte spindles in Drosophila are consistent with the possibility that their bivalents are also encased by laterally-associated microtubule bundles22–25. Moreover, features of our model may help explain the previous intriguing observation that in mouse oocytes, both substantial congression and biorientation of bivalents occur several hours before establishment of detectable end-on microtubule/kinetochore associations26, 27. Although it has been assumed that biorientation in this context was mediated by unstable microtubule associations in the vicinity of kinetochores, in light of our current findings we suggest an alternative view. Specifically, we envision that bivalents in mouse oocytes may be similarly ensheathed by lateral microtubule bundles, and that this ensheathment may enable congression and biorientation of bivalents (without requiring kinetochore/microtubule end attachments) by the model we have described (Fig. 5).

During meiosis in mouse oocytes, kinetochores eventually interact with microtubule ends and form kinetochore fibers just prior to the metaphase to anaphase transition26. It is possible that such end-on interactions are also established in C. elegans oocytes and could provide a poleward force to drive anaphase A. Alternatively, chromosome segregation could be accomplished by chromosome movement along laterally-associated microtubule bundles, utilizing the proposed poleward force that opposes KLP-19 during prometaphase. Under either scenario, we suggest that removal of KLP-19 (and regulatory factors such as the CPC) from chromosomes at anaphase may contribute to their separation to the spindle poles by relieving forces pushing them to the metaphase plate.

In addition to providing a new view of how chromosome congression is achieved on acentrosomal spindles, our studies identified two proteins (KLP-18 and MESP-1) required for spindle bipolarity. Although the Kinesin-12 family motor KLP-18 was known to be required for oocyte spindle assembly5, our high-resolution analysis allowed us to ascribe a specific role for this protein in the establishment and/or maintenance of bipolarity. This finding is intriguing given previous work in Xenopus egg extracts. While addition of a dominant negative form of Xenopus Kinesin-12 to extracts caused bipolarity defects28, immunodepletion did not significantly affect spindle assembly29, 30, leading to confusion about the function of this motor. In light of our findings, we speculate that Kinesin-12 motors may play a conserved role in promoting bipolarity, but their contributions may be masked in some organisms by Kinesin-5 (which functions in bipolarity establishment and maintenance31). Intriguingly, recent Xenopus experiments have revealed conditions where spindle bipolarity can be achieved in the absence of Kinesin-5 function32, 33; it will be interesting to test whether Kinesin-12 provides this activity. Thus, analysis of spindle assembly in C. elegans (an organism where Kinesin-5 does not dominate34) provided an opportunity to reveal new factors promoting bipolarity and we expect that future studies of these proteins will shed light on how bipolarity is established in the absence of centrosomes. Moreover, the ability to induce the formation of monopolar acentrosomal spindles will be valuable as a tool for future studies of chromosome dynamics during oocyte meiosis.

Methods

Strains

In this study, “wild-type” refers to N2 (Bristol) worms, while the term “control” refers to control(RNAi) worms. For most experiments, integrated lines expressing GFP::tubulin; GFP::histone (strain EU1067, gift of Bruce Bowerman) or GFP::tubulin; mCherry::histone (strain OD57, gift of Jon Audhya)35 were used. emb-27(g48) worms obtained from the C. elegans Genetics Center were crossed with EU1067 to create strain AV335 (emb-27(g48)II; unc-119(ed3) ruIs32[unc-119(+) pie-1::GFP::H2B]III; ruIs57[unc-119(+) pie-1::GFP::tubulin]); these worms were used for all experiments requiring an APC-arrest. Metaphase I arrest was achieved by shifting adult AV335 worms from 20°C to 25°C for 5–7 hours before imaging.

RNAi

Individual RNAi clones picked from an RNAi feeding library36, 37 were used to inoculate overnight LB/100 µg/ml Amp cultures. These saturated cultures were used to seed NGM plates containing 100 µg/ml Amp and 1 mM IPTG; plates were left at room temperature overnight to induce dsRNA formation. The next day, L1 worms synchronized by bleaching were put on the plates, and the worms were grown to adulthood by placing the plates at 15°C for 5 days. Control plates were seeded with bacteria containing empty feeding library vector (L4440).

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was performed as previously described8, 38, using a fixation time of 30 minutes in −20°C methanol. Primary antibodies used were mouse anti-α-tubulin (DM1α, Sigma) at 1:500, rabbit anti-KLP-1910 at 1:4000, rabbit anti-AIR-211 at 1:250, rabbit anti-KNL-339 at 1:4000, rat anti-HIM-107 at 1:500 and rabbit anti-ASPM-1 at 1:4000. Anti-ASPM-1 antibody (a gift from Arshad Desai) was raised and affinity purified against amino acids 9–165. Secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse and Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated goat anti-rabbit, both at 1:400.

High-resolution imaging

For live imaging, GFP- or mCherry-expressing worms were mounted on MP Multitest slides. Worms were picked into a drop of M9 containing 0.1% Tricaine, 0.01% Tetramisole40, a coverslip was laid on top and the slide was imaged immediately. Deltavision deconvolution microscopy with a 100× objective was used for both live and fixed imaging. Image stacks were obtained at 0.2 µm Z steps for fixed samples and 0.3 µm for live imaging, deconvolved and projected for presentation. Except where noted, images are full projections of data stacks encompassing the entire meiotic spindle. In some cases partial projections are displayed to highlight particular features of spindle organization. Movies show individual z-sections, displayed at 2 sections per second. Control and RNAi worms were processed in parallel and image exposure times were kept constant within each experiment.

To quantitatively compare the fluorescence intensities of microtubules ensheathing the chromosomes with fluorescence adjacent to the bivalent ends, individual pixel intensities within a 4 pixel by 33–34 pixel area spanning the ensheathing microtubule bundles in the vicinity of the bivalent ends were determined and graphed using softWoRx (Applied Precision) software (Fig. S3). Pixel intensities in the domains outside the ensheathing microtubule bundles were averaged for each image, and these average values were then subtracted from the dataset. These subtracted values were used to calculate ratios between the peak intensity of each ensheathing bundle and the region of minimum intensity between the bundles.

Quantification

For quantification of bivalent orientation, worms expressing GFP::histone and GFP::tubulin were ethanol-fixed by picking worms onto a slide and adding 100% ethanol and letting it evaporate (this ethanol step was performed three times before adding mounting media). This fixation preserved GFP fluorescence and allowed high-resolution images to be acquired. For monopolar spindles (generated by klp-18 RNAi), chromosome orientation was determined by tracing a line from the center of each aster through the midpoint of each bivalent. A second line was then drawn mirroring the long axis of each bivalent, and the angle between the two lines was measured (Fig. S4). For bipolar spindles, bivalents were classified either as oriented or not oriented; bivalents were considered to be oriented if their long axes were parallel with the spindle axis.

For quantification of RNAi phenotypes, APC-arrested worms expressing GFP::histone and GFP::tubulin were mounted live and visualized using a 63× objective on a Zeiss Axioplan II microscope. Although the APC arrest conditions yield a row of embryos arrested at metaphase I, only the most recently fertilized embryo from each gonad arm (the +1 embryo, next to the spermatheca) was analyzed to avoid the possibility of problems introduced by prolonged arrest. For quantitation of chromosome congression, only embryos that had assembled bipolar spindles were considered. A subset of +1 embryos in both control and experimental worms had disorganized microtubule arrays, presumably reflecting earlier stages of spindle assembly. For klp-19(RNAi), the fractions of embryos in this excluded class were similar to control worms in both experiments (Experiment 1: control 51.1%, klp-19(RNAi) 48%, p=0.77. Experiment 2: control 29%, klp-19(RNAi) 25.9%, p=0.64). However, icp-1(RNAi) embryos had an increase in disorganized arrays, possibly reflecting additional roles for ICP-1 (Experiment 1: control 51.1%, icp-1(RNAi) 61.7%, p=0.15. Experiment 2: control 29%, icp-1(RNAi) 52.9 %, p=0.0004). In experiments assessing chromosome positions on monopolar spindles, all +1 embryos in both control (klp-18(RNAi)) and experimental (klp-18(RNAi); klp-19(RNAi)) worms exhibited clear aster-like monopolar spindles, suggesting that monopolar spindles form immediately following initiation of the meiotic divisions.

Supplementary Material

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Villeneuve lab for support and discussions, Rebecca Heald, Vahan Indjeian and Mara Schvarzstein for comments on the manuscript, Joost Monen, Paul Maddox, and members of the Desai and Oegema labs for technical advice, Julien Dumont and Arshad Desai for sharing data prior to publication, and Jon Audhya, Bruce Bowerman, Arshad Desai, Barbara Meyer, Jim Powers, and Jill Schumacher for reagents. Additionally, some strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). This work was supported by NIH RO1 GM53804 to A.M.V.; S.M.W. was a Damon Runyon Fellow supported by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (DRG-#1827-04) and is currently a Special Fellow of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb1891

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc2760407?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1038/ncb1891

Article citations

The doublecortin-family kinase ZYG-8DCLK1 regulates microtubule dynamics and motor-driven forces to promote the stability of C. elegans acentrosomal spindles.

PLoS Genet, 20(9):e1011373, 03 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39226307 | PMCID: PMC11398696

Meiosis-specific functions of kinetochore protein SPC105R required for chromosome segregation in Drosophila oocytes.

Mol Biol Cell, 35(8):ar105, 12 Jun 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38865189 | PMCID: PMC11321039

Microtubule length correlates with spindle length in C. elegans meiosis.

Cytoskeleton (Hoboken), 81(8):356-368, 07 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38450962

Auxin-induced degradation of the aurora A kinase, AIR-1, in C. elegans does not prevent assembly of bipolar meiotic spindles.

MicroPubl Biol, 2024, 31 Jan 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38362120 | PMCID: PMC10867633

Redundant microtubule crosslinkers prevent meiotic spindle bending to ensure diploid offspring in C. elegans.

PLoS Genet, 19(12):e1011090, 27 Dec 2023

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 38150489 | PMCID: PMC10775986

Go to all (109) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Multiple motors cooperate to establish and maintain acentrosomal spindle bipolarity in C. elegans oocyte meiosis.

Elife, 11:e72872, 11 Feb 2022

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 35147496 | PMCID: PMC8963883

A Switch in Microtubule Orientation during C. elegans Meiosis.

Curr Biol, 28(18):2991-2997.e2, 06 Sep 2018

Cited by: 20 articles | PMID: 30197085

Assembly of Caenorhabditis elegans acentrosomal spindles occurs without evident microtubule-organizing centers and requires microtubule sorting by KLP-18/kinesin-12 and MESP-1.

Mol Biol Cell, 27(20):3122-3131, 24 Aug 2016

Cited by: 34 articles | PMID: 27559133 | PMCID: PMC5063619

The chromosomal basis of meiotic acentrosomal spindle assembly and function in oocytes.

Chromosoma, 126(3):351-364, 11 Nov 2016

Cited by: 25 articles | PMID: 27837282 | PMCID: PMC5426991

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIGMS NIH HHS (7)

Grant ID: R01 GM053804-10

Grant ID: R01 GM053804-13

Grant ID: R01 GM053804

Grant ID: R01 GM53804

Grant ID: R01 GM053804-14

Grant ID: R01 GM053804-12

Grant ID: R01 GM053804-11