Abstract

Free full text

Wnt signaling arrests effector T cell differentiation and generates CD8+ memory stem cells

Associated Data

Abstract

Self-renewing cell populations such as hematopoietic stem cells and memory B and T lymphocytes might be regulated by shared signaling pathways1. Wnt/β-catenin is an evolutionarily conserved pathway that promotes hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and multipotency by limiting stem cell proliferation and differentiation2,3, but its role in the generation and maintenance of memory T cells is unknown. We found that the induction of Wnt/β-catenin signaling using inhibitors of glycogen-sythase-kinase-3β or the Wnt protein family member, Wnt3a, arrested CD8+ T cell development into effector cells. By blocking T-cell differentiation, Wnt signaling enabled the generation of CD44low, CD62Lhigh, Sca-1high, CD122high, Bcl-2high self-renewing, multipotent CD8+ memory stem cells with proliferative and anti-tumor capacities exceeding those of central and effector memory T cell subsets. These findings reveal a key role for Wnt signaling in the maintenance of stemness in mature memory CD8+ T cells and have important implications for the design of novel vaccination strategies and adoptive immunotherapies.

T cell factor (Tcf) 1 and lymphoid enhancer-binding factor (Lef) 1 are downstream transcription factors of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Tcf1 and Lef1 are required for normal thymic T cell development, but less is known about Wnt function in mature T cells2,4. Although experiments using multimerized TCF/LEF binding site reporter system have revealed that Wnt signaling is active in mature CD8+ T cells, the impact of this pathway to this cell population has yet to be fully elucidated5. At least three lines of evidence indicate that Wnt signaling might regulate the maturation of post-thymic T lymphocytes: i.) CD8+ T cells from Tcf7−/− mice, which are missing the gene that encodes for TCF1, display a more differentiated phenotype (CD44high and CD62Llow) than WT T cells6; ii.) expression of Lef1 and Tcf7, decreases with progressive differentiation of CD8+ T cells from naive (TN) → central memory (TCM) → effector memory (TEM) inhumans7 and mouse (Supplementary Fig. 1); and iii.) high levels of Ctnnb1 (which encodes β-catenin), Lef1, Tcf7 have been detected in T cells with increased potential to form memory in vivo8,9. Thus, triggering the activities of the Wnt signaling transcription factors TCF1 and LEF1 could promote stem-like self-renewal capacity in mature T cells.

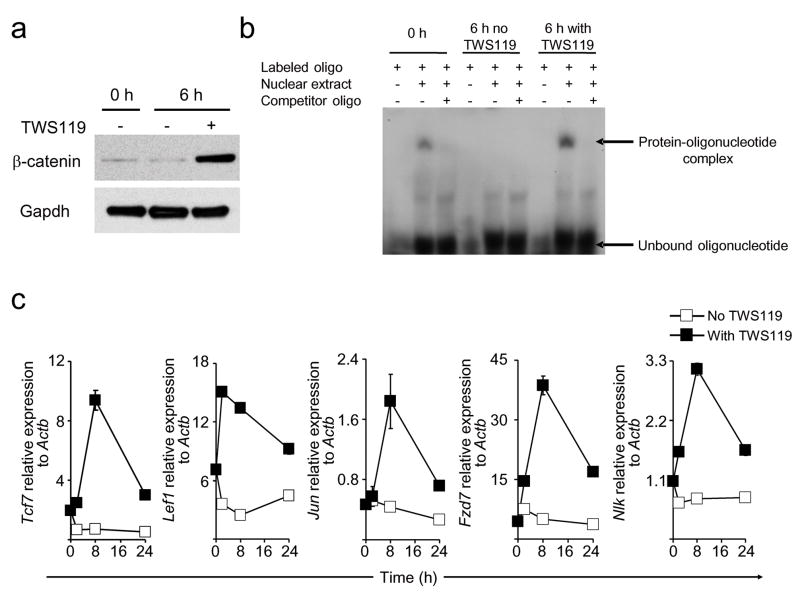

To test the impact of Wnt/β-catenin signaling on mature CD8+ T cells, we primed TN in the presence of the 4,6-disubstituted pyrrolopyrimidine TWS119, a potent inhibitor of the serine/threonine kinase glycogen-synthase-kinase-3β (Gsk-3β)10. Gsk-3β blockade mimics Wnt signaling by promoting the accumulation of β-catenin, the molecule that tethers the TCF and LEF transcription factors to targeted DNA2. TWS119 triggered a rapid accumulation of β-catenin (mean 6.8 +/− SD 1.7-fold increase by densitometry; p < 0.05) (Fig. 1a), augmented nuclear protein-TCF/LEF oligonucleotide interaction (Fig. 1b) and sharply up-regulated Tcf711, Lef112 and other Wnt target genes including Jun13, Frizzled7 (Fzd7)14, Nemo-like-kinase (Nlk)15 (Fig. 1c). By contrast, T cell activation in the absence of the Gsk-3β inhibitor resulted in the down-regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway at these steps of the signaling cascade (Fig. 1a–c). Thus, TWS119 activated the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in naive T cells and reversed the physiological down-regulation of Tcf7 and Lef1 induced by T cell activation7.

Naive CD8+ T cells were primed in vitro with anti-CD3 (2 μg ml−1) and anti-CD28 (1 μg ml−1) specific antibodies with or without 7 μM TWS119. a, Western blot analysis of β-catenin and Gapdh in CD8+ T cells treated with or without TWS119. b, Electrophoretic mobility shift assay of nuclear extract from CD8+ T cells treated with or without TWS119 using P32-labeled oligonucleotide probes designed from the TCF/LEF binding region of TCF1 target gene Fzd 7. Unlabeled oligonucleotide probes were used as competitor. c, Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the expression of Tcf7, Lef1, Jun, Fzd7, and Nlk in CD8+ T cells treated with or without TWS119. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. All data are representative of at least two independently performed experiments.

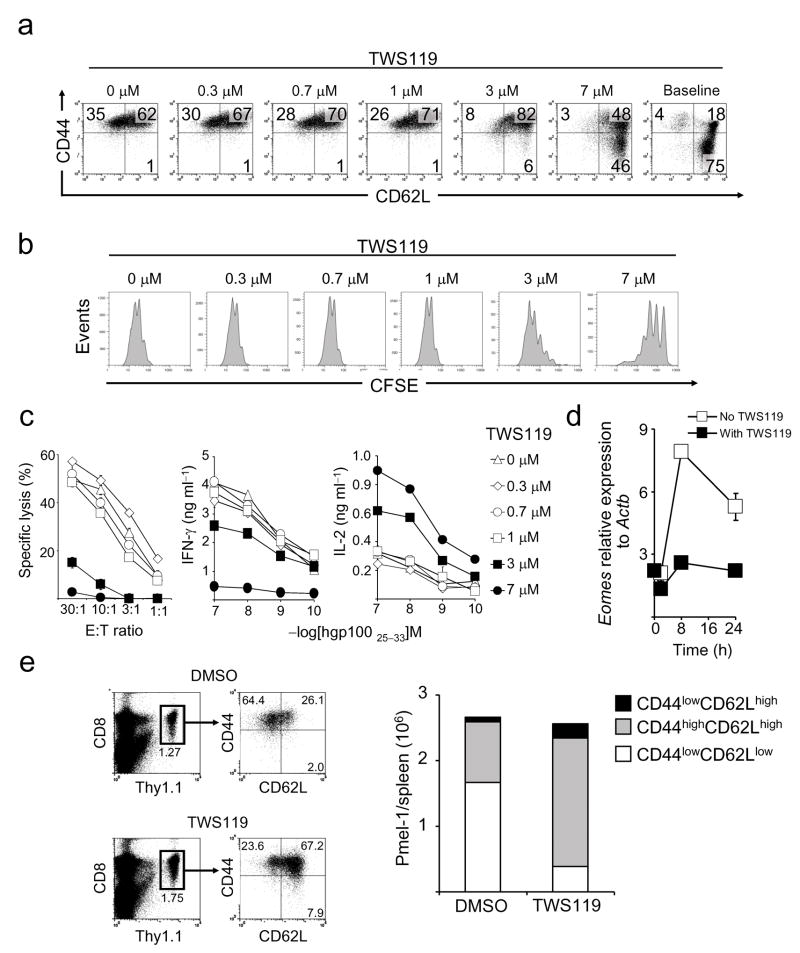

We sought to assess the effect of Wnt signaling on CD8+ T cell differentiation and proliferation. We stimulated CFSE-labeled CD8+ T cells from pmel-1 TCR transgenic mice16 with the cognate antigen, gp100, in the presence of titrated doses of TWS119 and analyzed them for the expression of the differentiation markers CD44 and CD62L. CD44 expression is known to increase with T cell differentiation while CD62L is progressively lost17. TWS119 increased the frequency of T cells that retained CD62L expression in a dose-dependent manner, indicating that it inhibited CD8+ T cell differentiation (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, 46% of CD8+ T cells cultured in the presence of the highest concentration of Gsk-3β inhibitor failed to up-regulate CD44, maintaining a “naive” CD44lowCD62Lhigh phenotype (Fig. 2a). Low doses of TWS119 (≤ 1 μM) preserved CD62L expression without affecting T cell proliferation, while higher drug concentrations promoted a dose-dependent inhibition of cell cycling (Fig. 2b). Arrested differentiation and proliferation of CD8+ T cells by TWS119 was not secondary to the impact of the drug on dendritic cells (DC), because we observed similar results stimulating purified CD8+ T cells in a DC-free system (Supplementary Fig. 2a,b). Similar to TWS119, we found that the structurally unrelated Gsk-3β inhibitor, 6-bromo-substituted indirubin, BIO18,19, inhibited T cell differentiation (Supplementary Fig. 3a) and induced the expression of the Wnt transcription factors Tcf7 and Lef1 (Supplementary Fig. 3b). The use of an analog, BIO-acetoxime19, with a greater Gsk-3β kinase inhibitory specificity, retained the observed activity while the use of N-methylated analog (Methyl-BIO)19, a kinase inactive control, had no effect (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b). These results are in contrast with those obtained using lithium chloride20 as a Gsk-3β inhibitor, which is less active and specific than the inhibitors used in the present study19. Because Gsk-3β regulates several signaling pathways other than Wnt, we sought to more directly test whether the impact of the pharmacological blockade of Gsk-3β was dependent on mimicking the downstream signals of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. We primed CD8+ T cells in the presence of Wnt3A, a Wnt protein that has been shown to promote stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency via β-catenin accumulation in the cell nucleus21. Like TWS119, we found that Wnt3A itself inhibited T cell differentiation and proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 4). Thus, T cell proliferation and differentiation could be restrained through the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by the naturally-occuring ligand, Wnt3A, and by the pharamcologic inhibition of Gsk-3β downstream. Neverthelss, our data did not rule out the possibility that Gsk-3β inhibitors were regulating T cell differentiation by affecting other pathways in addition to Wnt.

a–c,CFSE-labeled naive pmel-1 CD8+ T cells were primed in vitro with CD8+ T cell depleted splenocytes pulsed with 1 μM hgp10025–33, in conjunction with 10 ng ml−1 IL-2 and titrated doses of TWS119. Four days following T cell activation, phenotypic (a) CFSE dilution assays (b) and cytokine and 51Cr release assays (c) were performed. Data in panel c are represented as mean +/− SEM. d, Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the expression of Eomes in CD8+ T cells after priming with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 specific antibodies with or without 7 μM TWS119. Data are represented as mean +/−SEM. e, Flow cytometry and enumeration of T cell subsets six days after vaccination with or without TWS119. WT mice received adoptive transfer of 106 naive pmel-1 thy1.1+ CD8+ T cells in conjunction with recombinant fowlpox-based hgp100 vaccine. Mice received four daily doses of TWS119 (at 30 mg kg−1) from day 0 to day 3 or DMSO as control. All data are representative of at least two independently performed experiments.

We sought to evaluate whether the phenotypic differences of pmel-1 CD8+ T cells induced by TWS119 were associated with functional changes. It has been previously shown that differentiating CD8+ T cells lose the capacity to produce IL-2 as they acquire the ability to kill target cells and release high levels of IFN-γ17,22. We found that TWS119 induced a dose-dependent decrease in T cell-specific killing and IFN-γ release associated with a preservation in the ability to produce IL-2 (Fig. 2c). These functional data confirmed the phenotypic findings that TWS119 was a negative regulator of TEFF differentiation. We next assessed if the inhibition of TEFF development was associated with the suppression of eomesodermin (Eomes), a master regulator of CD8+ T-cell effector function23. We found that the exposure of cells to TWS119 abrogated the induced expression of Eomes that occurred within 8h after T cell priming, indicating that TWS119-mediated suppression of the effector program was an early event (Fig. 2d). Altogether, phenotypic, functional and molecular data indicated that induction of Wnt signaling during T cell priming resulted in an inhibition of CD8+ T cell differentiation into TEFF cells. Given our in vitro findings, we tested whether TWS119 could influence the qualities of adoptively transferred pmel-1 CD8+ T cells in response to fowlpox-based gp100 immunization and prevent the induction of highly differentiated, senescent T cells, a major pitfall of current T cell-based vaccines24. We found that there were no differences in frequency or numbers of pmel-1 T cells in spleens six days after vaccination, but the development of TEFF was inhibited (Fig. 2e). More importantly, TWS119 augmented the numbers of CD44high, CD62Lhigh TCM in responding CD8+ T cells in the post-vaccination setting(Fig. 2e). Although the present approach does not enable the dissection of the cellular mechanism of action in vivo, TWS119 effectively altered CD8+ T cell differentiation after immunization.

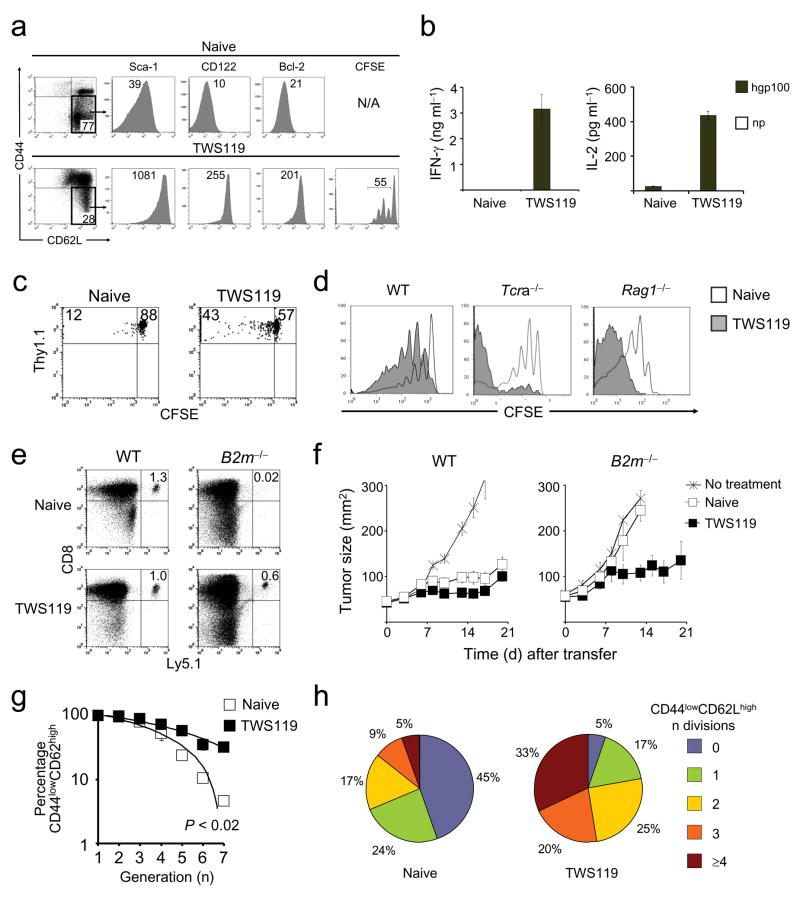

We observed a cell population that expressed low levels of CD44 and high levels of CD62Lwhen TWS119 was administered in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 2a,e) but it was unclear whether these cells remained naive after antigen encounter or had entered into a primordial memory state that retained some phenotypic traits of TN. Using a murine model of graft-versus-host disease, Zhang et al. have described population of CD44low CD62Lhigh memory CD8+ T cells that expressed high levels of stem cell antigen-1 (Sca-1), B-cell lymphoma protein 2 (Bcl-2), and common IL-2/IL-15 receptor β chain (CD122)25. Because these cells displayed robust self-renewal and the multipotent capacity to derive TCM, TEM, and TEFF they were designated “T memory stem cells” (TSCM)25. We sought to explore whether the CD44low CD62Lhigh pmel-1 T cells generated in vitro with TWS119 were TSCM. We found that TWS119-induced CD44low CD62Lhigh T cells had undergone up to four divisions as manifested by CFSE dilution, and uniformly expressed high levels of the core phenotypic traits of TSCM, namely Sca-1, CD122 and Bcl-2 (Fig. 3a). By contrast, TN expressed these markers at low levels (Fig. 3a). Similarly, Sca-1, CD122 and Bcl-2 were up-regulated in CD44low, CD62Lhigh pmel-1 T cells generated in vitro in the presence of BIO-acetoxime (Supplementary Fig. 5) or Wnt3A (Supplementary Fig. 6) and in vivo after specific-vaccination and TWS119 administration (Supplementary Fig. 7). These activation/memory T cell markers were not exclusively expressed by TSCM but instead only defined TSCM in the context of cells the were also CD44low CD62Lhigh (not shown). Antigen-experienced memory T cells can be distinguished from TN not only by phenotype but also by a number of functional properties: i.) rapid acquisition of effector functions upon antigen re-challenge26–28; ii.) pronounced cell cycling capacity29; iii.) robust homeostatic proliferation30; and iv.) independence of MHC class I for persistence31 and anti-tumor activity32. We found that, unlike TN, TWS119-induced CD44low, CD62Lhigh T cells rapidly released cytokines (IFN-γ and IL-2) upon antigen encounter (Fig. 3b), had undergone more cell division after adoptive transfer into a lymphoreplete host (Fig. 3c) or into sublethally irradiated or genetically lymphodepleted Tcra−/− (T cell-deficient) or Rag1−/− (T and B cell-deficient) hosts (Fig. 3d), and persisted and mediated tumor destruction (P < 0.05) in B2m−/− mice (which are MHC class I-deficient) (Fig. 3e,f). Altogether, these findings indicated that Wnt signaling induced the generation of a TSCM-like population that possessed the rapid recall ability, proliferative capacity and MHC class I independency that are distinct from naive T cells and characteristic of memory T cells.

CFSE-labeled, naive pmel-1 CD8+ T cells were primed in vitro with CD8+ T cell-depleted splenocytes pulsed with 1 μM hgp10025–33, in conjunction with 10 ng ml−1 IL-2 and 7 μM TWS119. a, Flow cytometry analysis of TWS119-treated and naive pmel-1 cells four days following T cell activation. b, Cytokine release assay of sorted CD44lowCD62Lhigh TWS119-treated and naive pmel-1 cells five days after antigenic stimulation. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. c and d, CFSE dilution of sorted CD44lowCD62Lhigh TWS119-treated and naive thy 1.1+ (c) or ly5.1+ (d) pmel-1 cells one month after transfer into WT (c) and sublethally-irradiated WT, or Tcra−/−, or Rag1−/− mice (d). Data are shown on thy 1.1+ (c) or ly5.1+ (d) CD8+ lymphocytes. e, Flow cytometry analysis of sorted TWS119-treated and naive ly5.1+ pmel-1 cells one month after transfer into WT or B2m−/− mice. Data are shown on ly5.1+, CD8+ lymphocytes. f, Tumor treatment of myeloablated WT or B2m−/− mice bearing B16 tumors established for 7 days. Mice received age-matched, lineage-depleted bone marrow cells. On the following day, 106 CD44lowCD62Lhigh TWS119-treated or naive pmel-1 cells were transferred in conjunction with exogenous IL-2.g and h, Flow cytometry analysis of CFSE-labeled, sorted CD44lowCD62Lhigh TWS119-treated and naive ly5.1+ pmel-1 cells one month after transfer into sublethally-irradiated WT mice. Data are represented as the percentage of CD44lowCD62Lhigh cells as a function of CFSE dilution of two independent experiments (g) and as fraction of cells with any given number of divisions (h). All data are representative of at least two independently performed experiments.

The concept of “stemness” encompasses the capability to both self-renew and generate more differentiated, specialized cells. We sought to determine the “stemness” of TWS119-generated CD44low, CD62Lhigh T cells by evaluating their fate after adoptive transfer cells into sublethally irradiated mice. Four weeks later, we found that high percentages of TWS119-generated cells preserved their original CD44low, CD62Lhigh phenotype even after multiple cell divisions, while TN rapidly acquired CD44 as a function of CFSE dilution (P < 0.02) (Fig. 3g,h). The differentiation of TWS119-induced CD44low, CD62Lhigh T cells was not arrested however, because they acquired CD44high expression, albeit at a slower pace. Unlike TN, TWS119-derived CD44low, CD62Lhigh, Sca-1high Tcells robustly proliferated (by 28 days, 95% had undergone cell division) (Fig. 3h), enabling their re-isolation and transfer to a secondary recipient (Supplementary Fig. 8). After four weeks, we found that the secondarily transferred CD44low, CD62Lhigh, Sca-1high Tcells had again regenerated all T cell subsets. Importantly, 43% of the cells retained the TSCM phenotype in spite of a second round of robust proliferation in vivo (Supplementary Figure 8). These findings indicated that Wnt signaling promoted the generation of self-renewing, multipotent TSCM.

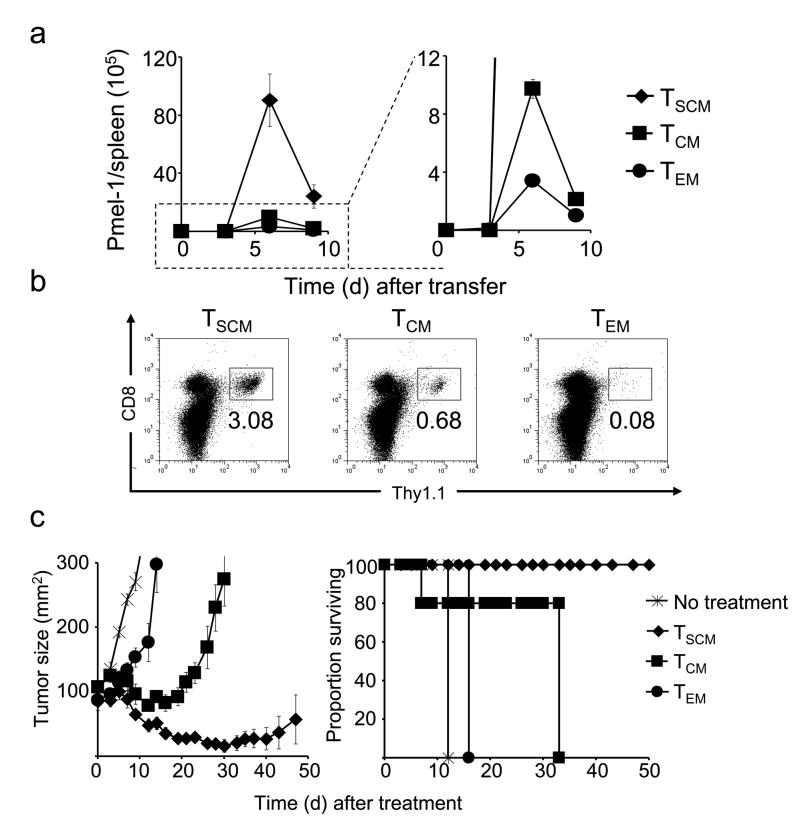

Having established that the CD44low, CD62Lhigh T cells generated in the presence of TWS119 were bona fide TSCM and not merely naive, we sought to compare them with the well defined memory T cell subsets, TCM and TEM, in secondary challenge experiments. Highly-purified pmel-1 thy1.1+ memory T cell subsets were adoptively transferred into sublethally-irradiated micein combination with recombinant vaccinia-based gp100 vaccine and IL-2. As previously reported by our group and others33,34, the in vivo recall responsesof TCM were greater than TEM (Fig. 4a). TSCM, however, robustly expanded by approximately 200-fold in the spleen alone. These levels were ≈ 10-times higher than TCM and ap; 30-times higher than TEM (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, TSCM exhibited an enhanced survival capacity as revealed by the frequencies of pmel-1 cells in the spleens of vaccinated mice one month after transfer (Fig. 4b). T cell proliferative and survival capacities have been correlated with tumor responses in mice and humans receiving adoptive T cell-based therapies35,36. To assess whether the enhanced replicative capability of TSCM would result in superior anti-tumor activity, we adoptively transferred limiting numbers of pmel-1 memory T cell subsets into sublethally-irradiated hosts bearing B16 tumors, in combination with gp100 vaccine and IL-2. As we previously reported33, TCM conferred superior anti-tumor immunity compared with TEM (tumor regression P < 0.01; overall survival P = 0.0644) (Fig. 4c). It was striking that minuscule numbers (4 × 104) of TSCM were able to trigger the destruction of bulky tumors (1 cm3 containing ap; 109 cells) and to improve survival (TSCM vs.TCM, P < 0.005; TSCM vs. TEM P < 0.005) (Fig. 4c). Thus, adoptive transfer of TSCM in combination with tumor-antigen vaccination and exogenous IL-2 produced a far more robust and therapeutically significant secondary response compared with the other memory T cell subsets.

Pmel-1 naive CD8+ T cells were primed in vitro with splenocytes pulsed with 1 μM hgp10025–33, in conjunction with 10 ng ml−1 IL-2 with or without 7 μM TWS119. Five days after antigenic stimulation, TSCM, TCM or TEM were sorted based on the phenotype. Sublethally-irradiated WT mice received 5 × 104 pmel-1 TSCM, TCM or TEM in conjunction with a recombinant vaccinia virus encoding hgp100 and exogenous IL-2. a, Absolute numbers of adoptively transferred pmel-1 cells (identified by CD8+ thy1.1+ lymphocytes) in the spleens of treated animals. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. b, Flow cytometry analysis for the expression of CD8 and thy1.1. c, Tumor treatment and survival of sublethally-irradiated WT mice bearing B16 tumors established for 10 days (n = 5 for all groups) receiving 4 × 104 pmel-1 TSCM, TCM or TEM in conjunction with a recombinant vaccinia virus encoding hgp100 and exogenous IL-2. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. All data shown are representative of at least two independently performed experiments.

Arrest of lymphocyte differentiation in order to maintain long-lived, self-renewing antigen-experienced T cells with the stem cell-like properties has been postulated as the basis of the continual generation of effector T cells37, but the transcription factors that regulate this process have not been fully elucidated. Although the physiologic role of Wnt signaling in post-thymic T cell development remains unknown, our data indicate that Wnt can regulate the “stemness” of CD8+ T cells by suppressing their differentiation into TEFF. In addition, other circumstantial evidence supports our findings. We recently reported that high levels of the Wnt transcription factors Tcf7 and Lef1 were expressed by T cells whose development into TEFF had been arrested using IL-218. Conversely, Tcf7−/− mice reportedly have an increased frequency of T cells displaying a CD44high, CD62Llow TEFF/TEM phenotype6. Paralleling our own observations in CD8+ T cells, expression of a stabilized form of β-catenin inhibited the proliferation and effector function of CD4+ T cells in a model of inflammatory bowel disease38. Furthermore, productive CD4+ T cell memory precursors overexpressed Ctnnb1 and Tcf7 as well as Bcl2 and Il2rb9. These factors were all implicated in the formation and maintenance of TSCM in the present study.

Our findings also have parallels in stem cell biology where Wnt signaling plays a pivotal role in promoting self-renewal while limiting proliferation and differentiation2,3. Using mice overexpressing the Wnt signaling inhibitor Dickkopf1 in the hematopoietic stem cell niche, Fleming et al., have found that hematopoietic stem cells exposed to a Wnt-inhibitory environment were less quiescent and had profound defects in their ability to reconstitute the host after serial transplants3. T cell lineage commitment to effector versus memory subsets has been recently linked to the asymmetric segregation and inheritance of proteins that control cell fate specification39. Although we do not know the role of Wnt in the asymmetric division of CD8+ T cells, unequal localization and activities of Wnt signaling component including β-catenin have been implicated in cell fate specification in Caenorhabditis elegans40.

The ability to pharmacologically induce TSCM has significant implications for the field of adoptive immunotherapy. The findings that small numbers of TSCM in conjunction with specific vaccination and IL-2 can cause the regression of large established vascularized tumors could reduce the cost and complexity of highly effective therapies based on the adoptive transfer of anti-tumor T cells35. Using existing technology36, it may be possible to genetically engineer the human counterpart of CD8+ TSCM to express T cell receptors or chimeric antigen receptors while pharamacologically mimicking Wnt signaling. This might ultimately allow for the widespread application of adoptive immunotherapy based on multipotent, highly proliferative, tumor-specific TSCM. Finally, the modulation of Wnt signaling to induce long-term T cell memory might be important for T cell-based vaccines designed to target intracellular pathogens. Increasing data indicate that protection against intracellular pathogens correlates with the induction and maintenance of TCM responses, but these responses have not been reproducibly obtained using current vaccination strategies24,28,34. In vivo administration of small molecule agonists of Wnt might be useful to consistently achieve this goal.

Methods

Mice and tumor lines

Pmel-1 TCR transgenic (Tg) mice (Jackson Laboratories) and pmel-1 ly5.1 double Tg mice and pmel-1 thy1.1 double Tg mice were previously described16,17. B16 (H-2b), a gp100+ murine melanoma, and the gp100− MCA-205 (National Cancer Institute Tumor Repository) were maintained in culture media.

Antibodies, flow cytometry and cell sorting

All antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences. Flow cytometry acquisition was performed on a BD FACSCanto™, or BD FACSCanto™ II Flow cytometer. Samples were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). Naive and T cell memory subsets were sorted using the BD FACSAria™ cell sorter.

Pharmacologic inhibitors of Gsk-3β and Wnt3A

TWS119, BIO, BIO-acetoxime, Methyl-BIO (EMD biosciences) and Wnt3a (R&D systems) were reconstituted according to the manufacturer’s instructions and used in experiments in vitro or in vivo at indicated doses.

In vitro activation of CD8+ T cells

Pmel-1 splenocytes were stimulated with 1 μM hgp10025–33 in a culture media containing 10 ng ml−1 of IL-2 (Chiron Corporation). Enriched CD8+ T cells from WT were activated on plate-bound anti-CD3 and 1 μg ml−1 soluble anti-CD28 antibody in a culture media containing 10 ng ml−1 of IL-2. Enriched CD8+ T cells were depleted of non-CD8+ T cells using a MACS negative selection column (Miltenyi Biotech, Inc).

Cytokine Release and Cytolytic Assays

MCA-205 (2.5 × 104) cells were pulsed with 1 μM hgp10025–33 or irrelevant influenza nucleoprotein peptide (np) and incubated overnight with T cells at 1:1 ratio at 37°C. Supernatants were analyzed by murine IFN-γ and murine IL-2 ELISA kits (Pierce-Endogen). For 51Cr release assays, MCA-205 target cells were pulsed with 1 μM hgp10025–33 or np and 100 μCi of 51Cr (Amersham Biosciences) for 2 h at 37°C. Labeled cells (103) were incubated with T cells at indicated ratios for 4 h at 37°C. Maximal and spontaneous 51Cr releases were determined by incubating 103 labeled targets in either 2% SDS or medium.

Adoptive cell transfer

Adoptive cell transfer, immunization with recombinant poxvirus-based vaccines and tumor experiments were performed as described16,17,32. C57BL/6, Tcra−/− and Rag1−/− (Jackson Laboratories), B2m−/− (Taconic) were used as recipients. All animal experiments were conducted with theapproval of the NCI Animal Use and Care Committee.

Enumeration of Adoptively Transferred Cells

At days indicated, mice were sacrificed. Spleens were harvested and homogenized into a single cell suspension using the rubber end of a 3cc syringe and a 40 μM filter cup. Samples were enumerated using trypan blue exclusion and were analyzed by flow cytometry for CD8 and thy.1 expression by cells. The absolute number of pmel-1 cells was calculated by multiplying the splenocyte count by the ratio CD8+ thy1.1+/lymphocyte.

CFSE proliferation assays

CD8+ T cells labeled with 1 μM CFSE (Molecular Probes) were used in adoptive experiments or stimulated in vitro as described above.

Real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

RNA was isolated using RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN). cDNA was generated by reverse transcription (Applied Biosystems). Real time-polymerase chain reaction was performed using commercially available probes and primers for the indicated genes (Applied Biosystems) and a Prism 7900HT (Applied Biosystems). The levels of gene expression were calculated relative to the housekeeping genes β-actin (Actb).

Detection of β-catenin by Western Blot analysis

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) with protease inhibitor. Protein concentration was quantified with Bio-Rad protein assay. 20 μg of total protein were separated on 4–12% SDS-PAGE gel followed by standard immunoblot with anti-β-catenin (BD Bioscience), anti-Gapdh (Chemicon international) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Nuclear extracts were isolated using the nuclear extract kit (Active Motif) and then incubated (5 μg protein) with poly-dI-dC (1 μg μl−1 in TE), 5X Binding Buffer (Promega) and γ32P-ATP labeled oligonucleotide probes (Sense: CACAGAGAAAACAAAGCGCGCTATT; Antisense: AATAGCGCGCTTTGTTTTCTCTGTG), containing the TCF/LEF binding motif AACAAAG. Unlabeled oligonucleotide probes were used as competitors. Samples were incubated 30 min at RT and loaded onto the gel (NuPAGE 4–12% or Bis-Tris Gel Invitrogen). Gel was blotted on a nitrocellulose membrane and exposed to the X-ray film.

Statistical analysis

Tumor slopes were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum test. Survival analyses andgraphs were performed using Kaplan–Meier methods.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. The authors have no conflicting financial interests. The authors would like to thank S.A. Rosenberg, C.A. Klebanoff and S. Kerkar for critical review of the manuscript, and A. Mixon and S. Farid of the Flow Cytometry Unit for Flow Cytometry analyses and sort.

Reference List

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.1982

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2707501

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1038/nm.1982

Article citations

Epigenetics behind CD8<sup>+</sup> T cell activation and exhaustion.

Genes Immun, 14 Nov 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39543311

Review

GPA33 expression in colorectal cancer can be induced by WNT inhibition and targeted by cellular therapy.

Oncogene, 29 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39472498

Deficiency of metabolic regulator PKM2 activates the pentose phosphate pathway and generates TCF1<sup>+</sup> progenitor CD8<sup>+</sup> T cells to improve immunotherapy.

Nat Immunol, 25(10):1884-1899, 26 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39327500

Phenotypic and spatial heterogeneity of CD8+ tumour infiltrating lymphocytes.

Mol Cancer, 23(1):193, 09 Sep 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 39251981 | PMCID: PMC11382426

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Influencing factors and solution strategies of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T) cell immunotherapy.

Oncol Res, 32(9):1479-1516, 23 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39220130 | PMCID: PMC11361912

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (652) article citations

Other citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Essential role of the Wnt pathway effector Tcf-1 for the establishment of functional CD8 T cell memory.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 107(21):9777-9782, 10 May 2010

Cited by: 235 articles | PMID: 20457902 | PMCID: PMC2906901

Constitutive activation of Wnt signaling favors generation of memory CD8 T cells.

J Immunol, 184(3):1191-1199, 21 Dec 2009

Cited by: 118 articles | PMID: 20026746 | PMCID: PMC2809813

Differences in the transduction of canonical Wnt signals demarcate effector and memory CD8 T cells with distinct recall proliferation capacity.

J Immunol, 193(6):2784-2791, 15 Aug 2014

Cited by: 23 articles | PMID: 25127860

The Transcription Factor TCF1 in T Cell Differentiation and Aging.

Int J Mol Sci, 21(18):E6497, 05 Sep 2020

Cited by: 36 articles | PMID: 32899486 | PMCID: PMC7554785

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Intramural NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: Z01 BC010763-02