Abstract

Purpose

The overactive bladder symptom score (OABSS) consists of 4 questions regarding OAB symptoms. The aim of this study was to develop Korean version of the OABSS from the original Japanese version, with subsequent linguistic validation.Methods

Between February and May 2008, the translation and linguistic validation process was performed as follows: a forward translation, reconciliation, backward translation, cognitive debriefing, and final proofreading.Results

A forward translation from the original version of the OABSS to the Korean language was carried out by 2 native Korean speakers, who were also fluent in Japanese. Reconciliation was made after review of both translations by a panel consisting of both translators and one of the authors. Another bilingual translator who had never seen the original version of the OABSS carried out a translation of the reconciled version back into Japanese, and the original and backward-translated versions were subsequently compared. After discussion of all discrepancies between both versions by the panel, a second Korean version was produced. During cognitive debriefing, 5 outpatients with OAB reported that each question of the Korean version was significant and appropriate for their symptoms. However, 2 patients said that some parts of the questions or instructions were not clear or were not easy to understand. According to the cognitive debriefing, some words and phrases were revised into more understandable expressions.Conclusions

A Korean version of the OABSS was developed and linguistic validation was performed. Further studies are needed to assess the reproducibility and validity of the questionnaire in Korean populations.Free full text

Korean Version of the Overactive Bladder Symptom Score Questionnaire: Translation and Linguistic Validation

Abstract

Purpose

The overactive bladder symptom score (OABSS) consists of 4 questions regarding OAB symptoms. The aim of this study was to develop Korean version of the OABSS from the original Japanese version, with subsequent linguistic validation.

Methods

Between February and May 2008, the translation and linguistic validation process was performed as follows: a forward translation, reconciliation, backward translation, cognitive debriefing, and final proofreading.

Results

A forward translation from the original version of the OABSS to the Korean language was carried out by 2 native Korean speakers, who were also fluent in Japanese. Reconciliation was made after review of both translations by a panel consisting of both translators and one of the authors. Another bilingual translator who had never seen the original version of the OABSS carried out a translation of the reconciled version back into Japanese, and the original and backward-translated versions were subsequently compared. After discussion of all discrepancies between both versions by the panel, a second Korean version was produced. During cognitive debriefing, 5 outpatients with OAB reported that each question of the Korean version was significant and appropriate for their symptoms. However, 2 patients said that some parts of the questions or instructions were not clear or were not easy to understand. According to the cognitive debriefing, some words and phrases were revised into more understandable expressions.

Conclusions

A Korean version of the OABSS was developed and linguistic validation was performed. Further studies are needed to assess the reproducibility and validity of the questionnaire in Korean populations.

INTRODUCTION

Overactive bladder (OAB) is characterized by a symptom syndrome of urinary urgency, with or without urgency incontinence, usually with urinary frequency and nocturia, in the absence of infection or other obvious pathologic features [1]. OAB is found at frequencies of 10.0 to 32.6% among community-dwelling men and women, although the prevalence of OAB varies according to the target population and definition of OAB. Using current International Continence Society (ICS) definitions of OAB [1], the prevalence of OAB symptoms at least "often" has been reported to be 15.8% and 32.6% for men and women aged ≥40 years, respectively, in the United States [2], whereas the overall prevalence was 10.0% and 14.3%, respectively, among Korean counterparts aged ≥18 years [3].

Because OAB is diagnosed on the basis of subjective symptoms, rather than objective criteria, the patient's perspective is important in the assessment and management of patients with OAB. Therefore, questionnaires that measure the severity of symptoms and their impact on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) play important roles in this disease entity. To date, several questionnaires for the measurement of patient-reported outcomes of OAB are available [4,5]. However, each questionnaire has specific weaknesses for application to real practice; namely, some measure the burden of OAB symptoms on daily life rather than the symptoms themselves, some require recording in a micturition diary, and some are not simple to perform in daily practice. The overactive bladder symptom score (OABSS), a new assessment tool for OAB symptoms, was developed and validated in Japanese populations in 2006 by Homma et al. [6]. The OABSS comprises only 4 questions regarding daytime frequency, nocturia, urgency, and urgency incontinence and evaluates relevant symptoms from the patient's viewpoint. At present, the OABSS has just been used in clinical practice, although the majority of patients were Japanese [7-10]. Performance of the OABSS is simple and quick, and a good agreement between OABSS items and the corresponding diary variables was found in a clinical trial with anticholinergics [11]. Therefore, this questionnaire appears to be attractive and beneficial for use in daily practice where a quick and brief estimation of OAB symptoms and its changes following treatments is required. It is comprised of only 4 questions regarding OAB symptoms, highly sensitive to treatment-related changes of OAB symptoms [8,9], and demonstrated a fairly good agreement with corresponding diary variables [11].

Objectives of the present study are to develop a Korean version of the OABSS from the original Japanese version, with subsequent linguistic validation in Korean patients with OAB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Original OABSS Questionnaire

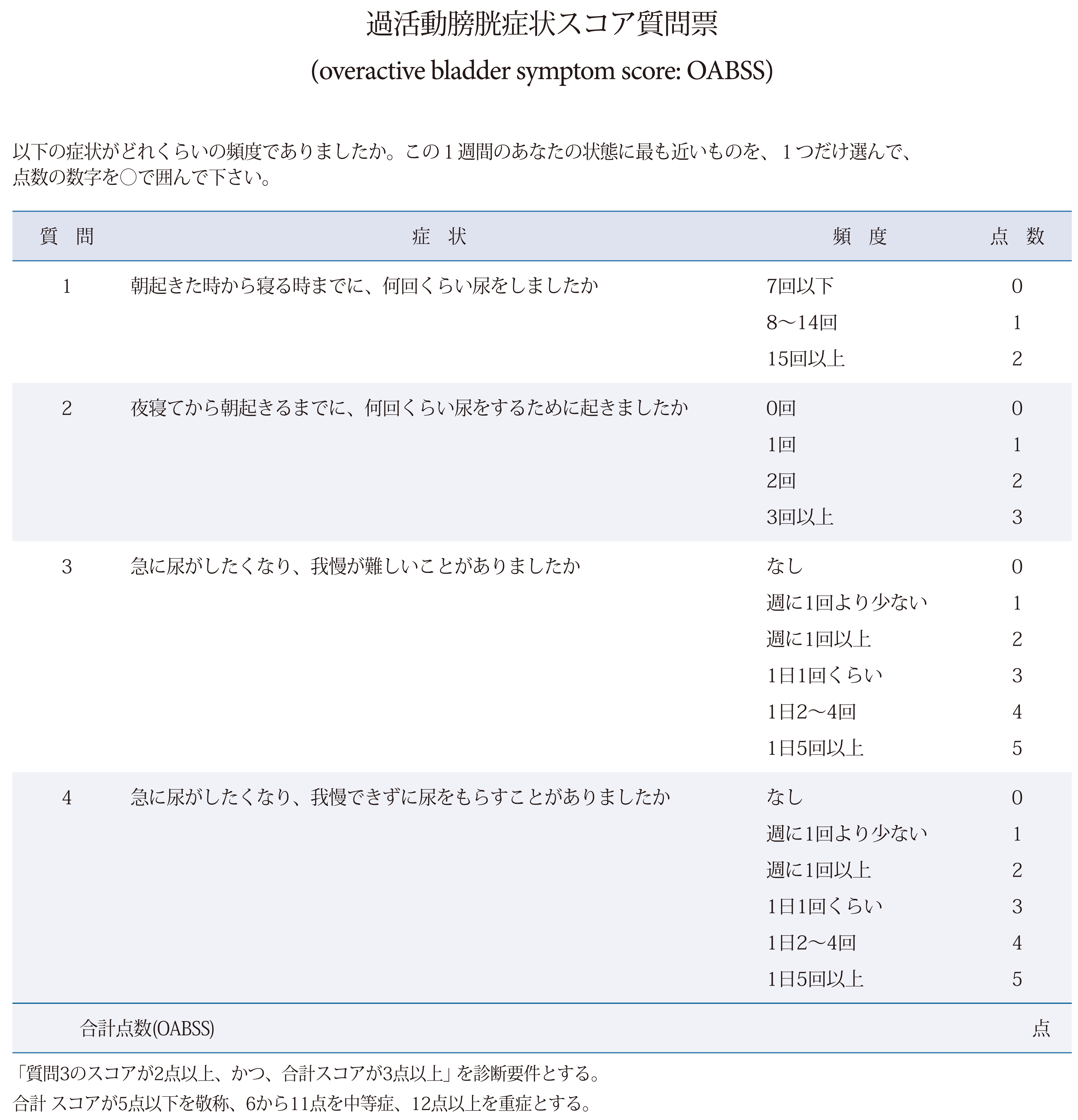

The original Japanese version of the OABSS consists of a total of 4 questions regarding daytime frequency, nocturia, urgency, and urgency incontinence (Appendix 1). Through the weighing of each symptom by use of the influence rate from the epidemiologic database on lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), which included 4,570 Japanese residents older than 40 years of age, the relative weight of the maximal score was designated to be 2:3:5:5 for daytime frequency, nocturia, urgency, and urgency incontinence, respectively [6]. The overall score is the sum of the 4 scores, and the diagnostic criteria for OAB are a total OABSS of 3 or more with an urgency score for Question 3 of 2 or more [12]. In the event that the OABSS is used as the standard for the assessment of the severity of OAB, it is recommended that a total score of 5 or less be defined as mild, a score of 6 to 11 as moderate, and a score of 12 or more as severe [13]. In this study, the original Japanese version of the OABSS was translated into Korean, but the English version [6] was used as a reference.

Methodology

Institutional Review Board approval was not applicable to this study and therefore approval was waived. During the translation, the corresponding author (SJO) directly controlled the overall process of the research. Translation and linguistic validation were carried out between February and May 2008. The overall process was similar to that for translation of the King's Health Questionnaire (KHQ) into Korean, which was performed by Oh et al. [14], with seven stages, as follows.

Permission for the translation and acquisition of the Japanese version of the OABSS

The corresponding author (SJO) contacted the owner of this questionnaire (Homma Y.) and obtained permission for the translation and the Japanese version of the OABSS by e-mailing.

Forward translation

Two translators (YHS [A] and CSY [B]) who did not know each other translated the original version into the Korean language (versions 1.0a and 1.0b, respectively) according to the instructions for forward translation supplied by the corresponding author. Each translator was a native Korean speaker but had lived in Japan for several years, and was therefore fluent in Japanese.

Reconciliation

On the basis of the two forward translations, reconciliation to form a single forward translation was made after two meetings of a panel consisting of the aforementioned translators and one (SJO) of the authors (version 1.1).

Backward translation

Another bilingual translator who had never seen the original version of the OABSS carried out a translation of the reconciled version back into the Japanese language, and the original and backward-translated Japanese versions were subsequently compared. When discrepancies between these versions regarding item concepts existed, a new forward translation for the incongruent words and sentences was done. Then, these forward translations were literally backward translated into Japanese. When the panel accepted the new translations, this process was completed and a second Korean version was produced (version 1.2).

Cognitive debriefing

Cognitive debriefing interviews with 5 outpatients with OAB were conducted to test the clarity, cultural adequacy, and comprehension of the wording of the translation and the appropriateness of the translated questions for the patients' symptoms. First, version 1.2 was presented to each patient and the time to complete the questionnaire was assessed. Then, each patient was interviewed in detail regarding what was asked by each question item. The patients provided feedback if they misunderstood the original concept of a question, if they had difficulty in understanding a question, or if a question was vague or not smooth. The authors analyzed the patients' feedback and discussed the expressions to be changed in the translation. A third Korean version (version 1.3) was produced with a report explaining the translation decisions.

Proofreading

The third version was proofread to check spelling, grammar, and formatting, and the final Korean version of the OABSS was completed (version 1.4).

RESULTS

Forward Translation and Reconciliation

"Sukoa Sitsumonhyo" in the Title was translated into "score query" and "jeom-su query" by translator A and translator B, respectively. This was finally reconciled as the "jeom-su questionnaire" in Korean. The "Hindo" in the original version was completely translated into "the number of times" instead of "frequency" because of the possibility of difficulty in understanding of the term "frequency." Another word in the instruction, "Keishou (敬称: a title of honor)," was translated into "mild symptom" because "Keishou (敬称)" was judged to be "Keishou (軽症: mild symptom)" according to the context, and "Keishou (敬称)" was thought to be a mistake in the original version.

Question 1 "Asa okita tokikara nerutoki madeni, nankai kurai nyo o simasitaka" in the original version was reconcilably translated into "How many times did you urinate from waking in the morning until sleeping?" It was thought that the addition of "at night" at the end of the sentence would enhance the understanding of the question. However, because the expression "at night" was not included in the original Japanese version, and backward translation would therefore result in a different version from the original, the panel decided not to add "at night" to the sentence. In the response option for question 1, "Kai" was translated into "times" by both translators. Although it was thought that "number" was easier to understand than "times," the panel decided to keep the term "times" in the reconciled version to maintain similarity to the expression of question 1. "Yoru netekara" in question 2 was translated into "in sleeping at night" and "through falling asleep at night" by translator A and translator B, respectively. The literal meaning of the original phrase was "from sleeping at night"; however, the panel decided to translate the phrase into "through falling asleep at night" for a more natural expression for Koreans. Question 3 "Kyuni nyoga sitakunari, gamanga mujukasii kotoga arimasitaka" was translated into "How often do you have a sudden desire to urinate, which is difficult to defer?" in the English version of this questionnaire [6]. However, the panel decided to follow the expression of the original Japanese version and translated this into "Have you had difficulty in deferring the urination due to sudden desire to urinate?" "Syuni itkaiyori sukunai" in the response option for Questions 3 and 4 was translated into "A smaller number than one per week" by both translators. The panel decided to use the term "less than" to improve the contrast against the next response option, "Syuni itkai ijou," which was reconciled to "More than once a week." Therefore, this phrase was reconciled to "Less than once a week." However, because it was possible for patients to have trouble understanding or to confuse the exact meaning of "less than," the panel decided to consider the patients' feedback on this phrase during the cognitive debriefing. "Nyo o morasu" in question 4 was literally translated into "get urine out" in the Korean language. Translator A and translator B translated this phrase into "urine leaks" and "let urine flow," respectively. Although the standard language in Korean for this phrase is "wet one's pants," the panel decided to translate it into "urine leaks" because patients may have trouble understanding the exact meaning of "wet one's pants."

Backward Translation

For most of the questionnaire, the Korean translation was accepted without certain objections because the original Japanese version and the backward translation were almost congruent. There were some differences in Japanese expression; however, the meaning of each sentence between both versions was judged to be almost identical.

Results of the Debriefing

The translation was tested by 5 outpatients with OAB. Their ages were diverse, between 30s and 70s, and their level of education was also various, from illiteracy to finishing a college course. Four were women and one was a man; two were employed in economic activities and three were housewives. The patients took an average of 122 seconds (range, 45 to 238 seconds) to complete the questionnaire. During the in-depth interviews, all of the patients suggested that the questionnaire was meaningful and relevant to their symptoms. Three patients reported that the instructions and questions were generally clear, easy to understand, and easy to complete on their own. One patient felt that the items were somewhat difficult to understand and one said that the items were not easy to understand.

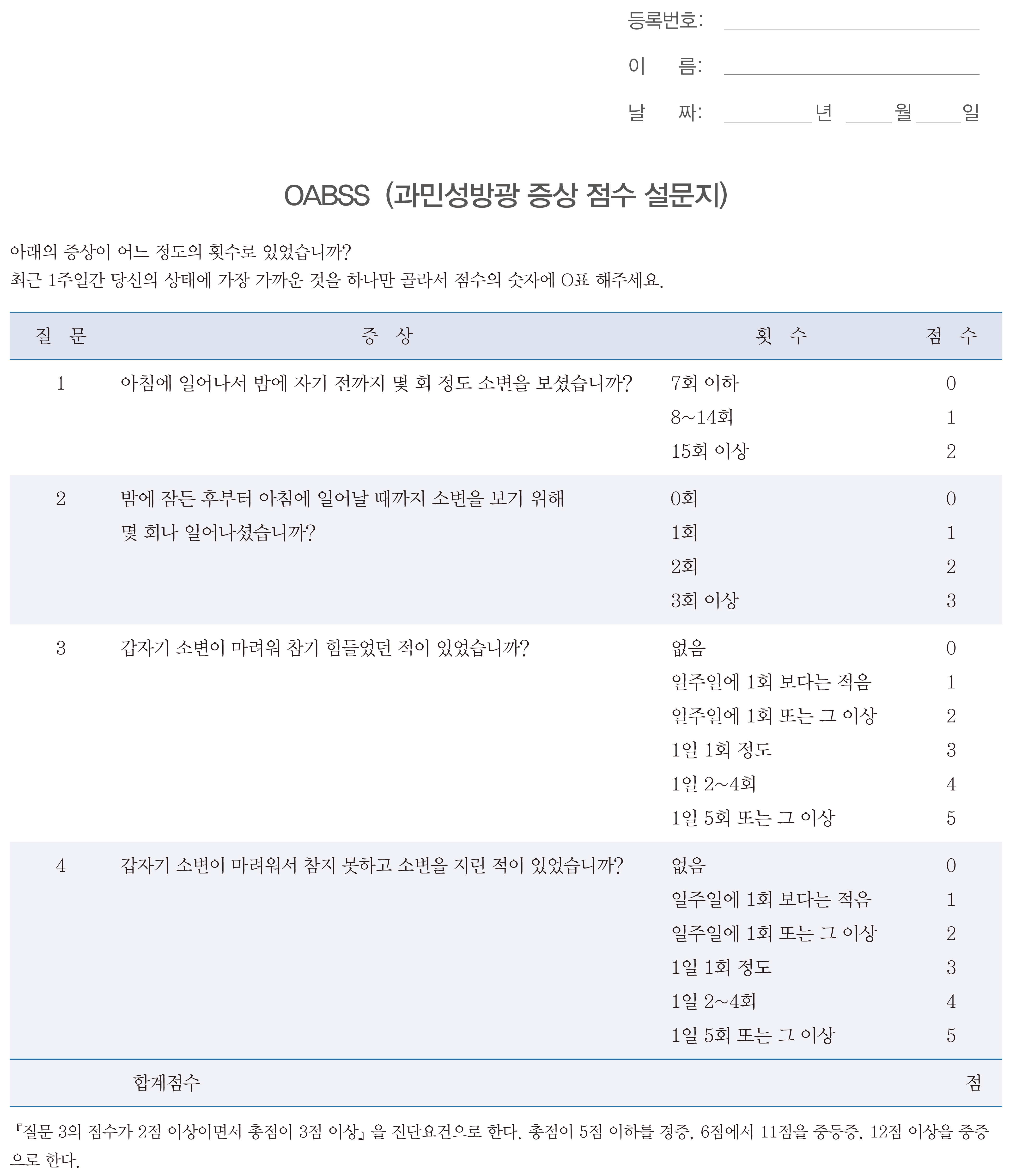

Most of the patients said the word "gwahwaldongsung bangkwang" in the title, which was translated from "Kakatsudou boukou" in the original version, was understandable but awkward in Korean expression. Therefore, this word was adjusted to the real diagnostic term "gwaminsung bangkwang," which is used in Korea. The word "ihaeui," which means "Ikano" in the instruction, was changed to "araeeui," according to a similar suggestion. For question 1, it was suggested that the expression "until sleeping" was vague in determining an exact point of time for patients. The panel decided to add the phrase "at night" to question 1 in order to make the meaning clearer and to enhance continuity with question 2. In question 2, "through falling asleep at night" was adjusted to "from sleeping at night" after cognitive debriefing for a more natural expression for Koreans. Some patients suggested that the severity of difficulty in deferring urination be added to the sentence in question 3. However, because the addition of an expression implying severity would result in limited response to the questionnaire, the panel did not accept this suggestion. In the response option for questions 3 and 4, most patients did not know the exact meaning of "less than" and "more than." Therefore, these expressions were judged to need some adjustment while the meanings in the original version were maintained: "Less than once a week" to "A smaller number than one per week," "More than once a week" to "Once a week or more," and "More than five times a day" to "Five times a day or more." In question 4, "urine leaks" was judged to be easy to understand by most of the patients; however, a difference from the original version regarding the subject of the sentence was pointed out during proofreading. That is, the subject in "urine leaks" was "urine," whereas the subject in the original Japanese version was a person. Therefore, this phrase was adjusted to "wet your pants" in order to adhere to the expression of the original version and Korean grammar. The reconciled translations were adjusted after cognitive debriefing and proofreading. The final Korean version of the OABSS was completed (Appendix 2).

DISCUSSION

OAB symptoms have a negative impact on the HRQOL of patients [15], sexual function [16], and sleep quality [7]. In particular, urgency and urge incontinence, key symptoms of OAB, increase the risk of falls in women aged 40 or older in the community [17]. Because OAB is defined as a symptom syndrome, it may be more useful to conduct a comprehensive assessment of various symptoms rather than an evaluation of individual symptoms. Most studies on clinical trials with OAB patients have assessed the symptom severity and efficacy of treatment according to counting episodes of urgency, incontinence, or frequency [18]. Nowadays, however, a growing concern has been raised regarding the appropriateness of simple counting of symptom episodes for reflecting patient perspectives and perceptions [19]. Therefore, many questionnaires have been developed to reflect the patient's perspective and are currently being used.

However, most of the available questionnaires [4] can be criticized for not evaluating OAB symptoms as they are, but rather evaluating the bother or effect on daily life resulting from the symptoms [6]. OAB symptoms can affect HRQOL, and, accordingly, evaluation of the impact on HRQOL, which reflects the patient's perspective, rather than the symptoms, may be important. However, a valid tool for describing the symptoms and their severity is also needed because OAB is a syndrome defined by various symptoms.

The OABSS is a questionnaire with a single total score for quantification of OAB symptoms, and has been reported to be highly sensitive to treatment-related changes in OAB symptoms in Japanese patients [11]. Previous studies found that the OABSS showed relatively close correlation with the patient perception of bladder condition (PPBC) and OAB-q subscales of HRQOL, with correlation coefficients of 0.36 to 0.57 [20]. In addition, fairly good agreement between OABSS items and the corresponding diary variables was identified at baseline and after an antimuscarinic medication, with particularly high correlations with urgency incontinence and nocturia [11]. From this, it may be possible to infer patient perceptions of OAB symptoms and their bother by the OABSS. Furthermore, owing to its simplicity and dependability, this questionnaire can be an alternative to a bladder diary for assessment of symptoms and efficacy in daily clinical practice. However, the OABSS may not be used for differentiating between OAB and other diseases causing similar LUTS because of its low specificity for OAB, like other questionnaires.

Still, the OABSS is recommended for use in Japanese populations at this time, because it was developed with the Japanese language and was validated on the basis of Japanese population data only. Use of the OABSS worldwide will require translation into the local language and validation with local data. We developed a Korean version of the OABSS from the original Japanese version, with subsequent linguistic validation in a Korean population with OAB. The authors have had some experience in translating foreign questionnaires for LUTS into the Korean language and validating them linguistically [14,21,22]. Translation of the Japanese version of the OABSS was not difficult because the questionnaire consists of only 4 questions, relevant response options, and instructions. In addition, the meanings of the terms used in the original version are generally easy for average people to understand. However, to improve the natural Korean expression, to better enhance understanding of the meaning, and to correct mistakes in wording or grammar, some adjustments of words or phrases were unavoidable during reconciliation of the forward translations and cognitive debriefing.

During the cognitive debriefing, the term "gwahwaldongsung bangkwang," which meant "OAB" in the original version, was adjusted to the real diagnostic term "gwaminsung bangkwang," that is used in Korea to improve the natural expression. In addition, the word "ihaeui," which means "following," in the instruction and the phrase "through falling asleep at night," which means "Yoru netekara," in question 2 were changed to "araeeui (following)" and "from sleeping at night" for the same reason. To enhance understanding of the meaning of the sentence, question 1 was adjusted with the addition of the phrase "at night" to make clearer to patients the point of time and to enhance continuity with question 2. In addition, the majority of patients suggested that the Korean word for "less than" and "more than" in the response option for questions 3 and 4 might not be easily understood; thus, some phrases were adjusted to make the meaning clearer. Finally, "urine leaks" in question 4 of the reconciled version was different from the original Japanese version regarding the subject of the sentence; thus, this was adjusted to "wet your pants" to adhere to the expression of the original version and Korean grammar.

In general, translation of a questionnaire into a version in another language is not straightforward, and differences in cultures and customs among the populations who use each language have to be considered during translation. The present study has demonstrated that the translation of the Japanese version of the OABSS into the Korean language and the cognitive debriefing process in 5 Korean OAB patients was performed without major translation difficulties. Adequate conceptual equivalents were demonstrated and accepted by the patients and physicians. However, it is essential to show that these language adaptation is reproducible, valid, and sensitive to treatment-related changes in the next psychometric performance to completely apply this questionnaire to Korean populations in clinical practice.

For more adequate verification of the Korean version, the authors are currently conducting studies on the reproducibility of the OABSS correlation with other measures of OAB symptoms, such as a 3-day micturition diary, International Prostatic Symptom Score, and PPBC and responsiveness to an anticholinergic medication in Korean populations. Information from these studies will be helpful to domestic researchers in their use of the Korean version of the OABSS as a tool for assessment of symptoms in research and clinical practice with domestic OAB patients.

References

Articles from International Neurourology Journal are provided here courtesy of Korean Continence Society

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.5213/inj.2011.15.3.135

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

http://www.einj.org/upload/pdf/inj-15-135.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.5213/inj.2011.15.3.135

Article citations

Efficacy and Safety of Urethral Catheter with Continuous Infusion of Ropivacaine after Urologic Surgery: A Pilot Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial.

J Pers Med, 14(8):835, 06 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39202026 | PMCID: PMC11355664

Retrospective Observational Study of Treatment Patterns and Efficacy of onabotulinumtoxinA Therapy in Patients with Refractory Overactive Bladder in Clinical Practice.

Toxins (Basel), 15(5):338, 15 May 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37235372 | PMCID: PMC10222470

Maximum Voided Volume Is a Better Clinical Parameter for Bladder Capacity Than Maximum Cystometric Capacity in Patients With Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms/Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: A Prospective Cohort Study.

Int Neurourol J, 26(4):317-324, 30 Dec 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 36599340 | PMCID: PMC9816439

Validation of acoustic voided volume measure: a pilot prospective study.

World J Urol, 41(2):509-514, 22 Dec 2022

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 36550234

Overactive bladder symptom score - translation and linguistic validation in Bengali.

J Family Med Prim Care, 11(1):79-83, 31 Jan 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 35309663 | PMCID: PMC8930147

Go to all (39) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Translation and Linguistic Validation of the Korean Version of the Treatment Satisfaction Visual Analogue Scale and the Overactive Bladder Satisfaction With Treatment Questionnaire.

Int Neurourol J, 21(4):309-319, 31 Dec 2017

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 29298470 | PMCID: PMC5756819

Korean Translation and Linguistic Validation of Urgency and Overactive Bladder Questionnaires.

Int Neurourol J, 24(1):66-76, 31 Mar 2020

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 32252188 | PMCID: PMC7136437

Korean Version of the Patient Perception of Study Medication Questionnaire: Translation and Linguistic Validation.

Int Neurourol J, 26(suppl 1):S47-56, 14 May 2021

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 34044482 | PMCID: PMC8896776

Translation and Linguistic Validation of the Korean Version of the "Benefit, Satisfaction, and Willingness to Continue" Questionnaire for Patients With Overactive Bladder.

Int Neurourol J, 20(3):255-259, 23 Sep 2016

Cited by: 7 articles | PMID: 27706015 | PMCID: PMC5083833

2

2