Abstract

Free full text

Current Epidemiology and Growing Resistance of Gram-Negative Pathogens

Abstract

In the 1980s, Gram-negative pathogens appeared to have been beaten by oxyimino-cephalosporins, carbapenems, and fluoroquinolones. Yet these pathogens have fought back, aided by their membrane organization, which promotes the exclusion and efflux of antibiotics, and by a remarkable propensity to recruit, transfer, and modify the expression of resistance genes, including those for extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), carbapenemases, aminoglycoside-blocking 16S rRNA methylases, and even a quinolone-modifying variant of an aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme. Gram-negative isolates -both fermenters and non-fermenters-susceptible only to colistin and, more variably, fosfomycin and tigecycline, are encountered with increasing frequency, including in Korea. Some ESBLs and carbapenemases have become associated with strains that have great epidemic potential, spreading across countries and continents; examples include Escherichia coli sequence type (ST)131 with CTX-M-15 ESBL and Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 with KPC carbapenemases. Both of these high-risk lineages have reached Korea. In other cases, notably New Delhi Metallo carbapenemase, the relevant gene is carried by promiscuous plasmids that readily transfer among strains and species. Unless antibiotic stewardship is reinforced, microbiological diagnosis accelerated, and antibiotic development reinvigorated, there is a real prospect that the antibiotic revolution of the 20th century will crumble.

INTRODUCTION

The ability to treat bacterial infection is critical to modern medicine, from abdominal surgery to transplants to cancer management. Without antibiotics, these procedures would be unthinkable owing to the infection risk. Yet this ability to beat infection has existed for only a brief fraction of human history, beginning with the introduction of sulfonamides in the 1930s. The 'antibiotic revolution' gathered pace from the late 1940s to the 1960s, with a golden age of natural product discovery. This period was followed by two decades of repeated successes in modifying natural antibiotics to enhance their activity. Subsequently, the flow of new antibiotics has dwindled, with diminishing numbers licensed in the 1990s and the first decade of this century [1,2]. The reasons are threefold: first, the technical difficulty of discovering new antibiotics, especially those able to penetrate Gram-negative bacteria [3,4]; second, the regulatory hurdles to new antibiotics which have become increasingly complex [5]; and, third, the brutal fact that antibiotics, as short-course treatments, are less lucrative for the pharmaceutical industry than are long-term therapies for chronic conditions [6,7].

The lack of new antibiotics is critically important, given the continued accumulation of resistance favored by Darwinian selection, which erodes the utility of existing antibiotics. Once a pathogen has been cultured some antibiotic retaining activity can usually be identified, at least in vitro. The greater problem is for empirical therapy, where growing resistance increases the risk that the antibiotic used will prove inactive. In severely ill patients, this ineffectiveness leads to increased mortality, length of hospital stay, and cost [8,9].

This review considers the extent of emerging and proliferating resistance in Gram-negative bacteria-where the problem is most acute-and discusses strategies that may be deployed to counter the threat.

GRAM-NEGATIVE BACTERIA

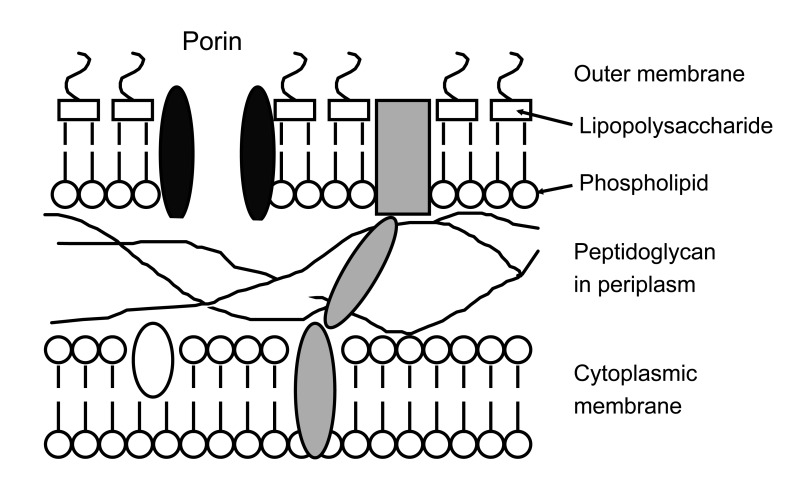

The defining feature of Gram-negative bacteria, distinguishing them from Gram-positive species, is a double membrane wall (Fig. 1). The outer membrane excludes large or hydrophobic molecules, including glycopeptides, daptomycin, and rifampicin, and slows the entry of drugs that can cross it, augmenting the effectiveness of the next line of defense. These defenses include periplasmic-β-lactamases and cytoplasmic membrane efflux pumps, which scavenge amphipathic molecules-including antibiotics-that enter the membrane, pumping them back out of the cell [10]. The combination of impermeability and clearance explains why Gram-negative bacteria are inherently more resistant than Gram-positive species, and why new antibiotics active against them are harder to find [3]. Efflux is especially important in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which has multiple pumps that render it resistant to many drug families active against other Gram-negative species [11,12].

Outer layers of the Gram-negative cell. To reach its target, the antibiotic must diffuse across the outer membrane, normally via porins, which form water-filled channels and exclude large or hydrophobic molecules. The drug must then evade periplasmic β-lactamases and efflux pumps; depending on its target, it may also need to cross the cytoplasmic membrane, often by energy-dependent uptake.

Both Enterobacteriaceae (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter spp., Proteus spp., Serratia spp.) and non-fermenters (Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, and related genera) are important opportunist pathogens. E. coli is-by a large margin-the most common agent of community and hospital urinary tract infections and the main aerobic component of the mixed flora in intra-abdominal infections. P. aeruginosa, Klebsiella, and Enterobacter are important in nosocomial pneumonia, especially in patients with prolonged hospitalization. Acinetobacter baumannii is less pathogenic, but notoriously causes outbreaks in the most vulnerable patients in intensive care units (ICUs). Gram-negative pathogens account for around half of all bacteremias, most of which arise due to bacterial overspill from other primary infection sites. In the UK, E. coli is the most common agent of bacteremia, causing 30% of all cases, whereas P. aeruginosa, Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter spp., and Proteeae each account for 4-8% of cases [13]. A few Gram-negative species are important classical pathogens; those remaining important in developed countries include Salmonella spp., Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Neisseria meningitidis, and N. gonorrhoeae. Others ranging from Vibrio cholenzae, to Burkholderia pseudomallei remain important in developing countries, but lie beyond the scope of this review.

ANTI-GRAM-NEGATIVE ANTIBIOTICS

The first anti-Gram-negative antibiotics were sulfonamides, introduced in the 1930s; tetracyclines, first-generation aminoglycosides, and chloramphenicol then became available in the late 1940s and early 1950s, respectively. Two quantum leaps followed. The first delivered semi-synthetic penicillins and first-generation cephalosporins in the early 1960s, along with more potent and less toxic aminoglycosides such as gentamicin and amikacin. The second, in the 1980s, led to the development of third- and fourth-generation oxyimino-cephalosporins, β-lactamase-inhibitor combinations, carbapenems, and fluoroquinolones. These drug families are now standard therapies for severe Gram-negative infections, but growing resistance has created the present problem, as few new agents have been developed to replace them.

Resistance in Enterobacteriaceae, internationally and in Korea

At launch, third-generation cephalosporins were almost universally active against Enterobacteriaceae; ceftazidime was also active against P. aeruginosa and, often, A. baumannii. Resistance emerged first in Enterobacter spp. (especially), Citrobacter freundii, and Serratia spp., all of which have inducibly-expressed chromosomal AmpC β-lactamases. Third-generation cephalosporins are labile to these enzymes but are weak inducers of their synthesis. The result is that cephalosporins kill the AmpC-inducible cells but confer an advantage upon spontaneous 'derepressed' variants that express AmpC activity without induction [14]. These variants arise by spontaneous mutation in inducible (i.e., normal) strains, and the likelihood of their selection during therapy, with consequent treatment failure, is as high as 20-30% when third-generation cephalosporin is used to treat an Enterobacter bacteraemia [15]. Selection is associated with a doubling of mortality and a 50% increase in hospital stay and doubling of cost for survivors (Table 1) [16]. Piperacillin-tazobactam is also compromised, but seems to be less often associated with selection than are third-generation cephalosporins, although the reasons for this difference remain uncertain and one analysis did find similar selectivity [17]. Fourth-generation cephalosporins (cefepime and cefpirome) and carbapenems are more stable and less selective (Table 2).

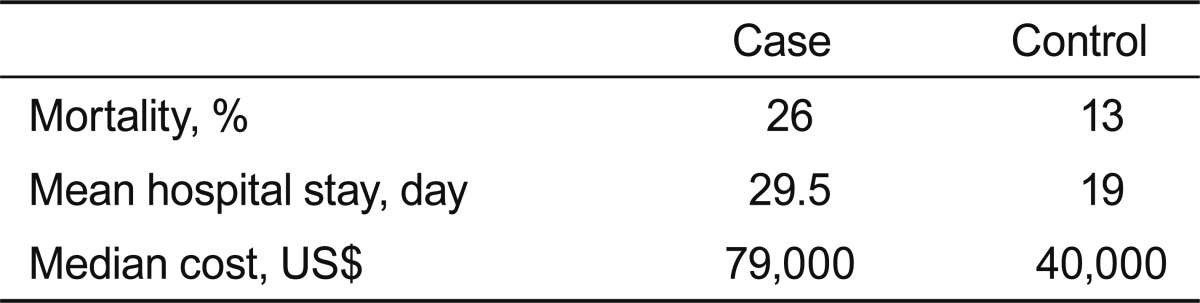

Table 1

Consequences of selection of AmpC-derepressed mutants during cephalosporin treatment of Enterobacter infections

Cases exhibited selection of AmpC-derepressed mutants during cephalosporin treatment of Enterobacter infections; controls are those in whom cephalosporins were used successfully, without selection of resistance [16].

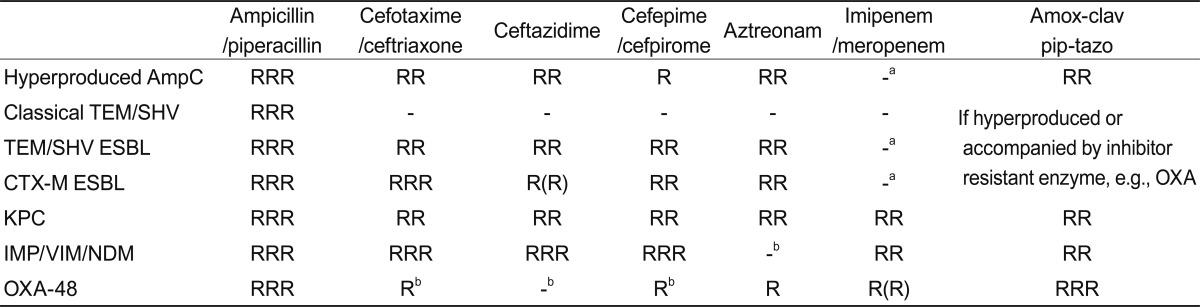

Table 2

Ability of β-lactamases to confer resistance

RRR, high-level resistance always seen; RR, resistance usually clear; R, MICs raised but may or may not exceed breakpoint; -, resistance not normally seen.

ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase.

aResistance arises if combined with impermeability.

bResistance widespread as producers often also have ESBLs.

Genes encoding AmpC β-lactamases have escaped from the chromosomes of Citrobacter and other genera to plasmids and are now circulating in E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae [18]. The enzymes they encode are variously called CMY, FOX, MOX and MIR types or, more usefully, 'plasmid AmpC.' Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) represent the second and greater plasmid-mediated threat to oxyimino-cephalosporins, affecting fourth- as well as third-generation analogues (Table 2). The earliest ESBLs, first identified in the 1980s, were mutants of the plasmid-borne TEM and SHV penicillinases that had disseminated in E. coli and other Enterobacteriaceae in the 1960s and 1970s [19]. Although third-generation cephalosporins are stable to classical TEM and SHV enzymes, over 200 ESBL mutants have been identified, with sequence changes that expand the active site, allowing attack on oxyimino-cephalosporins (see http://www.lahey.org/studies for a list). Many variants have been described only once or twice, but SHV-2, -5, -11, and -12 and TEM-3, -10, -26, -52, and -116 are widespread in many countries [20,21].

TEM and SHV ESBLs spread during the 1980s and 1990s, largely in Klebsiella spp. and particularly in ICUs [19,22]. Some strains caused major outbreaks, but did not substantially penetrate E. coli strains or spread in the community. This is surprising because E. coli strains with the progenitor TEM-1 enzyme are frequent in the human gut and must have been exposed to huge amounts of ceftriaxone, which was long the most widely used injectable antibiotic and has biliary excretion. These ESBLs may thus present a burden to E. coli, but this aspect remains to be properly explored.

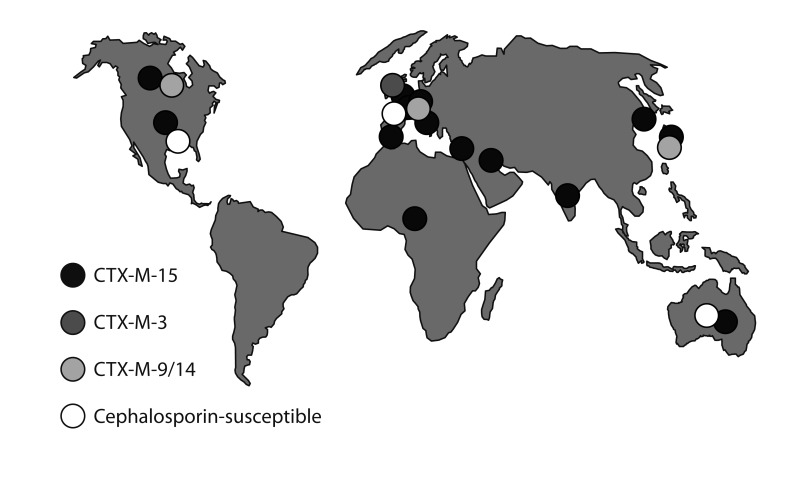

A massive shift in the distribution of ESBLs has occurred since 2000 with the spread of CTX-M types-a decade earlier in Argentina [23]. Unlike TEM and SHV variants, these ESBLS are not mutants of old plasmid-mediated penicillinases. Rather, their genes originated in the chromosomes of Kluyvera spp., a genus of no direct clinical importance, and were mobilized to plasmids by insertion sequences, notably ISEcp1 [24,25]. Plasmids encoding these CTX-M enzymes then reached human opportunists, where they have proliferated in community E. coli and hospital Klebsiella spp. Gene escape has occurred repeatedly, with five CTX-M families (groups 1, 2, 8, 9, and 25) circulating. Different CTX-M families dominate in different places: CTX-M-15 (group 1) is predominant in most of Europe, North America, the Middle East, and India, but CTX-M-14 (group 9) is most common in China, Southeast Asia, and Spain, and CTX-M-2 (group 2) is predominant in Argentina, Israel, and Japan [20,22].

The prevalence of ESBLs (CTX-M and other types) differs among patient groups and clinical and geographic settings. In the UK, around 10% of E. coli from bacteremias now have ESBLs -90% of them CTX-M types [26]- and producers are frequent in urinary isolates from geriatric patients, although denominators are poor, precluding accurate prevalence estimates. By contrast, their prevalence is ≤ 1% in community cystitis. Gut carriage of ESBL E. coli was seen in 40% of nursing home residents in Belfast (Northern Ireland), providing a reservoir for future urinary or intra-abdominal infections-which are frequent in these vulnerable patients-but in only 1-2% of other outpatients whose stools were examined by the clinical laboratory [27]. Many studies have shown that community infections with ESBL E. coli predominantly affect older (> 65 years) patients with recent hospitalization and antimicrobial treatment, especially with cephalosporins or quinolones [28]. Travel in high-prevalence countries is a risk factor for gut colonization by ESBL E. coli, with travel-associated-strains sometimes causing later urinary infections [29].

The variability in ESBL rates among population groups should prompt caution when viewing national prevalence rates; these benchmark values are of less clinical importance than local rates in different patient groups. Despite this caveat, a rough international picture can be drawn. Multiple surveys have shown that the highest ESBL rates for E. coli and Klebsiella spp. occur in India (≥ 80%) and China (≥ 60%), [30-32], with rates ≥ 30% elsewhere in East and Southeast Asia, Latin America, and southern Europe vs. 5-10% in Australasia, northern Europe, and North America [30]. Some studies have suggested that ESBL prevalence in India is equally high in community and hospital E. coli isolates [31], probably reflecting unregulated antibiotic use coupled with recycling of gut bacteria by an overloaded sewage infrastructure [33,34]. In Hong Kong, ESBLs were found in 7.3% of E. coli from uncomplicated community cystitis, including in 11/219 isolates from women aged 18-35 years, a much younger age group than typically affected by ESBL E. coli elsewhere [35]. A growing number of ESBL outbreaks has also been reported in neonatal units, likely due to the transfer of E. coli from the gut flora of one mother to her infant at birth, followed by spread among other infants in the unit [36,37].

The epidemiology of CTX-M ESBLs involves both plasmid dissemination and clonal success. CTX-M-15-the most prevalent enzyme-is most often encoded by IncF plasmids that are prone to multiple rearrangements [38]. In the case of K. pneumoniae, these plasmids are carried by diverse strains; some strains cause local outbreaks but none has achieved wider success [39]. In E. coli, however, CTX-M-15-encoding IncF plasmids are strongly associated with a sequence type (ST)131 lineage, now widespread globally [25,40] (Fig. 2). It remains unclear whether a progenitor ST131 strain acquired an original IncF-CTX-M-15 plasmid and then spread while diversifying, or whether ST131-a lineage that dates back to the 1980s-has repeatedly acquired IncF-CTX-M-15 plasmids at different times in different places, perhaps with considerable exchange to and from Klebsiella. E. coli ST131 occasionally hosts other ESBLs besides CTX-M-15: in Belfast (Northern Ireland, UK) it often has the IncI1 plasmid, pEK203, encoding CTX-M-3. CTX-M-3 differs from CTX-M-15 by only a single amino acid change and the two enzymes can interconvert by mutation: nevertheless, the sequences flanking blaCTX-M-3 in pEK203 differ from those flanking blaCTX-M-15 in its typical IncF plasmid hosts, e.g., pEK499 and pEK516 [41,42], showing that they reflect separate gene escapes from Kluyvera. CTX-M-14 ESBL, which dominates in the Far East, is not strongly associated with ST131 or other successful clones, and its accumulation largely entails plasmid spread among strains.

ESBLs achieved a high prevalence before 2000 in Korea; otherwise, the pattern appears similar to that elsewhere, with CTX-M ESBL types replacing TEM and SHV. In a review of studies published before 1998, Pai [43] estimated ESBL prevalence rates of 4.8-7.5% in E. coli and 22.5-22.8% in K. pneumoniae, with TEM-52 dominant in E. coli and SHV-2 and -12 in K. pneumoniae. Plasmid-mediated CMY-1 (AmpC) was estimated to occur in 15% of Enterobacteriaceae-an exceptionally high rate [43]. These results were broadly supported by a survey of 13 hospitals by Jeong et al. [44] in 2002, which found SHV-2a and -12 and TEM-19, -20, -52, and -116 to be the main ESBLs, although the prevalence of CMY-1 was much lower than Pai [43] had suggested. CTX-M ESBLs were first reported in Korea in 2005 [45] and are now predominant [46]: CTX-M-14 and -15 are both widespread [46,47]. As elsewhere, CTX-M-15 is strongly associated with E. coli ST131 [48], whereas CTX-M-14 is disseminated among strains [47]. Infection risk factors for ESBL producers resemble those found internationally, including prior healthcare and antibiotics [49,50]. More exceptional-but recapitulating the Hong Kong data [35]-is a 2006 multicenter survey finding of ESBLs in 11.8% of E. coli from uncomplicated cystitis [51]. A subsequent study of isolates collected in 2008-2009 found a lower (6.4%) rate of cephalosporin resistance in E. coli from cystitis, although the authors noted that ciprofloxacin resistance continued to increase from 15.2% in 2002 to 23.4% in 2006 and 24.8% in 2008-2009 [52].

Many ESBL producers in Korea and elsewhere are multiresistant to non-β-lactam antibiotics, including fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides [20,23,53]. The main factors in quinolone resistance are combinations of mutations affecting the chromosomal topoisomerase genes gyrA and parC. Resistance to other antibiotics, including trimethoprim, tetracyclines, sulfonamides, and chloramphenicol as well as aminoglycosides is often encoded by the same plasmids that determine the ESBL. IncF plasmids encoding CTX-M-15 ESBL often also determine AAC(6')-Ib-cr, which inactivates amikacin and tobramycin (not gentamicin) and also deactivates ciprofloxacin, augmenting resistance [54]. These plasmids also often encode OXA-1, an inhibitor-resistant penicillinase, conferring resistance to piperacillin-tazobactam and amoxicillin-clavulanate, even though these inhibitors inactivate CTX-M-15 [41,55].

Most aminoglycoside resistance among Enterobacteriaceae in the West is determined by aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes like AAC(6')-1b. These enzymes are also common in Asia, but wide circulation of the ArmA and RmtA-C 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) methylases is also found in Asia, unlike in Europe and the US [56-58]. These methylases modify bacterial ribosomes to block binding of all key aminoglycosides, including the new analogue ACHN-490 [59]. They are widespread in Korea and are commonly carried by plasmids that also encode SHV-12 and CTX-M-14 ESBLs, but have not been associated with CTX-M-15 or E. coli ST131 [60,61].

Carbapenem resistance

The growing prevalence of cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae is driving the directed and empirical use of carbapenems, as the only widely marketed β-lactams stable to ESBLs and AmpC enzymes (Table 2).

Carbapenems retained near-universal activity against Enterobacteriaceae for around 20 years after the introduction of imipenem in 1985, but resistance is now accumulating. It can evolve by porin loss, reducing drug entry in strains already containing high levels of AmpC or an ESBL [62]. This is a common source of low-level resistance to ertapenem, especially in Enterobacter and Klebsiella, with resistant variants sometimes selected during carbapenem therapy [63]. However, this problem is limited because these variants are often unstable and tend to revert to susceptibility, rarely spreading among patients [64,65]. Their porin deficiency likely impedes nutrition, reducing competitiveness.

Much more concerning is the gradual proliferation of carbapenemases, which are biochemically diverse and include members of three of the four β-lactamase classes (A, B, D).

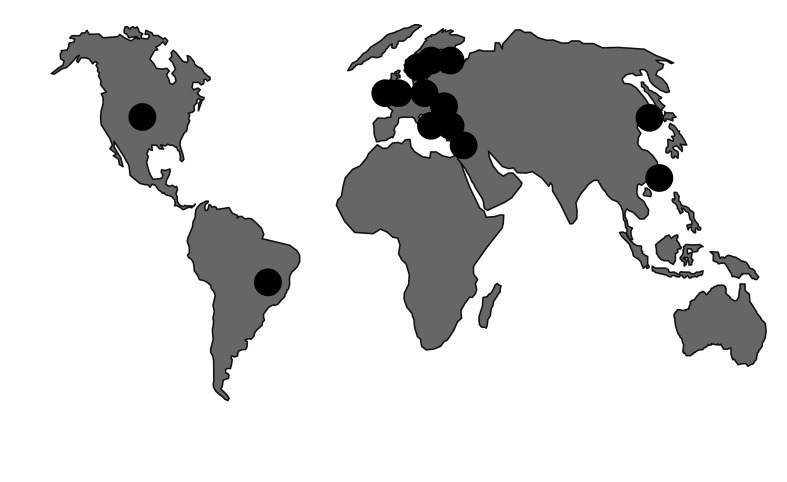

KPC enzymes (class A, non-metallo) are currently the predominant carbapenemases emerging in Enterobacteriaceae [66]. They were first recorded in North Carolina (USA) in 1997, with outbreaks in New York by 2005. Since 2006, KPC+ K. pneumoniae have spread across the USA and in Israel, Greece, and, latterly, Italy, with growing outbreaks in China, Brazil, and several European countries. The highest national prevalence rate (to 40%) is for K. pneumoniae from bacteremias in Greece [67]. Much of this spread reflects an association of KPC enzymes with a successful clone, K. pneumoniae, ST258 (Fig. 3) [68]. Members of this lineage are typically resistant to all antibiotics except colistin, tigecycline, and gentamicin. A colistin-resistant variant of ST258 is circulating in Greece [69], with cases also seen, possibly via import, in Hungary and the UK [70]. The reasons for the particular success of ST258 are uncertain, but its ability to spread swiftly is beyond dispute. In addition, KPC enzymes have spread considerably via plasmids among different K. pneumoniae strains and other Enterobacteriaceae, principally E. coli and Enterobacter spp.

Metallo-carbapenemases (class B) are biochemically very different from KPC, and include IMP, VIM, and New Delhi Metallo (NDM) enzymes, along with less frequently occurring families. IMP was recognized in Japan at the end of the 1980s [71] and has gradually spread worldwide, although it has not achieved great prevalence anywhere. VIM is more important; it was first recorded in P. aeruginosa in Verona (Italy) in 1997 [72] and then spread into Enterobacteriaceae, principally K. pneumoniae. By 2005, it was present in 40% of bloodstream K. pneumoniae from Greece, where it has subsequently been partly displaced by KPC enzymes [73].

Clusters of K. pneumoniae with VIM carbapenemases are increasingly being reported worldwide, although they are less numerous than isolates with KPC enzymes. A further distinction is that VIM enzymes are not associated with any particular clone, whereas KPC enzymes are associated with ST258 K. pneumoniae. Although local outbreaks occur, the larger issue is the dissemination of blaVIM among K. pneumoniae, largely by IncN plasmids [73,74].

NDM-the most publicized metallo-carbapenemase-is epicentered in India, where it occurs in 2-8% of Enterobacteriaceae at teaching hospitals [75,76], and in Pakistan, where 27% of inpatients at two military hospitals were carriers. blaNDM-1, encoding the enzyme, is wide-spread in surface-water bacteria in New Delhi, implying community circulation. Enterobacteriaceae (and occasionally Acinetobacter spp.) with NDM carbapenemase have repeatedly been imported into Europe, Asia, North America, and Australasia by those who have travelled or been hospitalized in the Indian subcontinent [77]. As with VIM metallo-carbapenemases, spread is largely by plasmid transfer, not clonal dissemination [77].

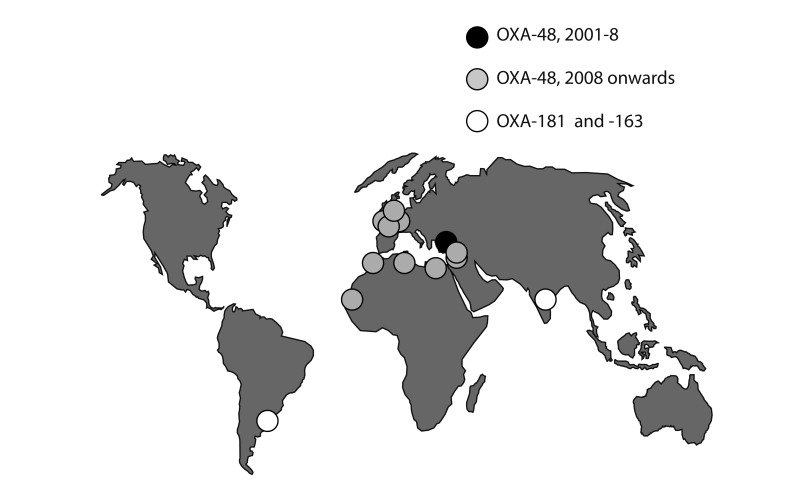

The final and very different-emerging carbapenemase of Enterobacteriaceae is OXA-48, reported in Turkey since 2001, mostly in K. pneumoniae. It has disseminated in the Middle East and North Africa since 2007-2008, with repeated import into Europe; outbreaks have occurred in the UK, Belgium, Ireland, France, Spain, and The Netherlands (Fig. 4) [78,79]. The main factor in its spread is dissemination of 50- and 70-kb plasmids carrying the blaOXA-48 transposon Tn1999 among Klebsiella strains [80]. A related enzyme, OXA-181, is circulating in India, where it seems less frequent than NDM-1 [81]. OXA-48 and -181 originated by separate mobilizations of chromosomal β-lactamase genes from Shewenella, a genus otherwise lacking clinical importance [79].

Spread of OXA-48 and related carbapenemases. Until 2007-2008, the OXA-48 enzyme was confined to Turkey. Carried by 50- and 70-kb plasmids, it has since spread to North Africa, the Middle East, and, increasingly Europe. A related enzyme, OXA-181, is circulating in India, but is rarer than the NDM-1 metallo-carbapenemase. These enzymes have not yet reached Korea.

To date, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae have shown little circulation in Korea, although C. freundii and S. marcescens with VIM-2 [82] and K. pneumoniae [83] with KPC enzymes have been reported, and a very recent report described an outbreak cluster of K. pneumoniae with the NDM-1 enzyme [84]. Unusually, an S. marcescens strain with AmpC and impermeability caused an outbreak involving nine patients at a hospital in Seoul [65]. Most disturbing is the recent appearance of KPC+ K. pneumoniae ST258. Only one producer has been reported to date [85], from a urinary infection in Seoul, but this development should raise concern, given the strain's dramatic success elsewhere.

KPC carbapenemases inactivate all β-lactams. Aztreonam is stable to the IMP, VIM, and NDM types, but these are often accompanied by aztreonam-hydrolyzing ESBLs. Similarly, although OXA-48 spares ceftazidime, it is often accompanied by ceftazidime-hydrolyzing ESBLs (Table 2). Resistance to non-β-lactams is variable, but many carbapenemase producers are susceptible only to colistin, tigecycline, and/or fosfomycin, none of which is an 'ideal' antibiotic. NDM carbapenemases are often accompanied by the 16S rRNA methylases mentioned earlier, compromising the widest range of aminoglycosides [59,81].

Non-fermenters

The prevalence of resistance in P. aeruginosa varies widely among countries. In Europe, resistance rates to aminoglycosides, carbapenems, cephalosporins, and fluoroquinolones are lowest (< 10%) in the northwest, particularly in Scandinavia, and highest (25-50%) in the southeast, particularly in Greece [86]. Rates are high in Latin America and Southeast Asia, and intermediate in the US [87].

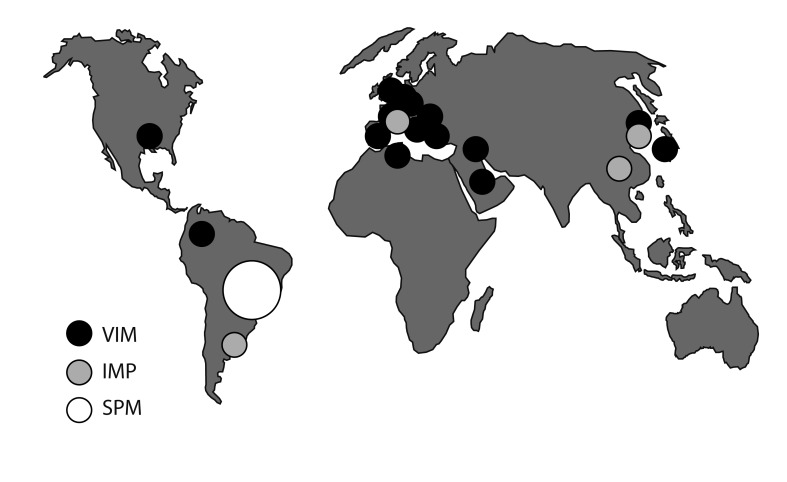

Most resistance among P. aeruginosa in Europe and North America involves mutations that restrict drug entry (the most common cause of carbapenem resistance), derepress chromosomal AmpC (as in Enterobacter, above) and up-regulate efflux [88,89]. Acquired mechanisms are more important in resistance in Asia and Latin America and include different ESBLs to those most prevalent in Enterobacteriaceae, notably PER-1, which is widespread in Turkey [90], and VEB-1, which first proliferated in Southeast Asia [91]. Metallo-β-lactamases are scattered and single-hospital outbreaks due to producers have occurred worldwide (Fig. 5) [92,93]. These outbreaks are often prolonged, with cases scattered over long periods, probably owing to persistence in the hospital structure, e.g., in sink traps. In Brazil, a clone with São Paolo Metallo (SPM)-β-lactamase has disseminated among hospitals, achieving national distribution [94]. Elsewhere, P. aeruginosa ST111, which corresponds to serotype O12 and 'burst group 4,' is now a common host to VIM metallo-carbapenemases [68]. This lineage has a long history of acquiring resistance -20 years ago it often carried the PSE-1 carbenicillinase [95]. ST235 (serotype 11) is also a successful accumulator of resistance, frequently hosting IMP and VIM carbapenemases [68].

Reported outbreaks due to metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Most carbapenem resistance in P. aeruginosa, including in Korea, is due to porin loss, but carbapenemase producers occur and may be strongly persistent in some hospitals. Korea has a particular concern regarding a nationally distributed strain that harbors the IMP-6 enzyme [97].

A 2005 survey of 23 hospitals in Korea found carbapenemases in 10% of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa, with VIM types 2.5-fold more common than IMP types [96]. The remaining 90% of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa were inferred to have impermeability-type resistance. Subsequently, an ST235 clone with the IMP-6 enzyme has disseminated nationally [97]. In a 2009 survey of 21 hospitals, this strain accounted for 30/386 (7.8%) isolates and was recovered in 14 sites. As with NDM-1 in Enterobacteriaceae, blaIMP-6 in Korean P. aeruginosa is often associated with the ArmA rRNA methylase [98].

The molecular epidemiology of A. baumannii, another important opportunistic non-fermenter, contrasts to that of P. aeruginosa, with resistance largely originating from the up-regulation of inherent chromosomal AmpC and carbapenemase (blaOXA-51) genes by insertion sequences, critically ISAba1, which migrate within the chromosome [99,100]. The insertion of ISAba1 in front of one of these β-lactamase genes provides an efficient promoter, allowing expression and resistance. Alternatively, resistance can be caused by acquired OXA-23, -40, and -58 carbapenemases [99]. OXA-23 originated as a chromosomal carbapenemase in Acinetobacter radioresistens [101], a species with no direct clinical importance.

OXA carbapenemases account for most carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii worldwide, including in Korea, where the resistant proportion reportedly grew from 13% in 2003 to 51% in 2008-2009, and where two carbapenemase-producing clones are in wide circulation among hospitals, one with OXA-23 and frequent colistin resistance, the other with up-regulated OXA-51 [102].

Metallo-carbapenemases also occur, with NDM recorded in A. baumannii (although not yet in Korea) and IMP in non-baumannii species, but these are extremely rare compared with OXA types [103]. A unique metallo-type, Seoul imipenemase (SIM-1), has been described from A. baumannii in Korea, but it has not disseminated [104].

As in Enterobacteriaceae, most resistance to non-β-lactams depends on acquired genes-not on mutation, as in P. aeruginosa. Acquired genes may be carried by plasmids or by massive 'resistance islands' inserted into the chromosome [105,106]. Colistin resistance, as in one of the prevalent Korean clones, can arise via changes to membrane phospholipids and lipopolysaccharides [107,108], and resistance to tigecycline by up-regulation of the chromosomal AdeB efflux pump is sometimes selected for during therapy [109].

Fastidious Gram-negative bacteria

A few N. meningitidis and H. influenzae isolates have low-level resistance to fluoroquinolones, whereas resistance to third-generation cephalosporins has not been seen in either species. N. meningitidis shows only slightly reduced susceptibility to penicillin, even after 70 years of use.

N. gonorrhoeae, by contrast, has sequentially developed resistance to low-level penicillin, high-level penicillin, and ciprofloxacin, with borderline non-susceptibility to cefixime (MICs, 0.12-0.5 mg/L) now proliferating [110], including in Korea [111,112]. This development is driving a treatment shift to high-dose ceftriaxone, sometimes (as in the UK) combined with azithromycin [113]. Few other options are available if substantial resistance to these treatments emerges and, disturbingly, two reports have described gonococci with resistance to ceftriaxone and cefixime: one from Japan [114] and the other from France [115]. The first patient developed an oropharyngeal infection and recovered-perhaps spontaneously-during a second course of ceftriaxone; the second developed a urethral infection that was cured with gentamicin.

THE FUTURE

The range of antibiotic options to treat Gram-positive infections, particularly those due to MRSA, has expanded in the past decade with the introduction of quinupristin-dalfopristin, linezolid, daptomycin, tigecycline, and, in some markets, telavancin and ceftaroline. Additional agents, including oritavancin, dalbavancin, and tedizolid (torezolid), are in phase III development and are anticipated in the next 2-3 years. Among these new anti-MRSA agents, only tigecycline shows any increase in in vitro anti-Gram-negative activity compared with previous members of its chemical family (tetracyclines), and its efficacy in severe infections is variable, with low serum levels and disappointing results in nosocomial pneumonia [116]. The only other anti-Gram-negative agent launched in the past decade is doripenem, which represents an incremental improvement over meropenem in anti-Pseudomonas activity, but is otherwise similar [117].

In short, little progress against Gram-negative bacteria has been made for a long time. Nevertheless, several new anti-Gram-negative agents are in phase III development and show promise. CXA-201, a cephalosorin (ceftolozane)-tazobactam combination, is four-fold more active than ceftazidime-still the best anti-pseudomonal cephalosporin-against P. aeruginosa [118,119]. Ceftazidime-avibactam, another new inhibitor combination, is active against strains with AmpC, ESBLs, and KPC or OXA-48 carbapenemases [120], and the neoglycoside plazomicin overcomes nearly all aminoglycoside-modifying-enzyme-mediated resistance [121].

Nevertheless, each of these agents has gaps in its spectrum, and none provides such complete coverage as ceftazidime, imipenem, and ciprofloxacin did when they were introduced 20-30 years ago. CXA-201 lacks activity against Enterobacteriaceae with metallo- and KPC carbapenemases and shows borderline activity against some ESBL and AmpC producers [122]; ceftazidime-avibactam lacks activity against strains with metallo-carbapenemases, such as VIM and NDM [120]; and plazomicin fails to overcome resistance mediated by ArmA and Rmt rRNA methylases [59].

Other antibiotics in earlier developmental stages may offer a more comprehensive solution. The most promising are 1) boron-based protein synthesis inhibitors (GSK-Anacor partnership) [123]-though their development was recently suspended, 2) fluorine-containing tetracyclines ('fluorocyclines,' Tetraphase) [124], and 3) novel protein synthesis inhibitors (RibX-Sanofi partnership). Aztreonam-avibactam shows the potential to overcome both metallo- and non-metallo-carbapenemases [120]; it is not yet under formal development but would be relatively easy to progress, following experience with ceftazidime-avibactam and ceftaroline-avibactam.

However, these drugs will only be available in the future, and licensing success is not guaranteed. Therefore, as much as possible must be done through good stewardship and infection control to prolong the life of existing antibiotics. Improvements in laboratory microbiology and its interaction with patient management are also critical. Currently, a 48-hour interval-at the very best-remains between the clinical diagnosis of a patient's infection and the clinician's acquisition of laboratory results indicating the isolate's susceptibility. During this interval the patient is treated empirically based on the likely pathogens and local resistance rates. Such treatment becomes more difficult as resistance increases, and multiple studies have shown that resistance to the empirical regimen leads to a near doubling of mortality in bacteremias [8]. One response is to start patients on the most powerful empirical antibiotic, typically a carbapenem combined with an anti-MRSA agent, and to 'de-escalate' once laboratory microbiology results are available [125,126]. Although this strategy improves initial coverage, which may benefit the patient [127], it has two pitfalls: first, hospitals frequently fail to enforce de-escalation when a susceptible pathogen is isolated; second, the approach does not specify the appropriate response when the patient still shows symptoms of infection but no pathogen is isolated. Both factors potentially lead to unnecessarily prolonged use of the broadest-spectrum agents, increasing the selection of resistance. The situation would be improved if microbiology could be accelerated, identifying pathogens and their resistances in hours rather than days, and without the need for culture [128]. Potential methods exist, including polymerase chain reaction or DNA arrays to seek species- and resistance-specific genes [129,130]. Nevertheless, great challenges remain, especially with non-sterile-site specimens, in which DNA extracted from the pathogen becomes mixed with that from commensals.

If these challenges can be overcome-perhaps first for blood and other sterile-site specimens-results can be delivered to the ward far more swiftly. Such development would reduce the conflict between the individual, who currently may benefit from receiving the most powerful antibiotics, and society, which benefits if they are conserved. This goal is surely worthwhile because the alternative is a world where high-tech medicine becomes ever more hazardous as-owing to proliferating resistance-it becomes increasingly more difficult to treat infection empirically.

References

Articles from The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine are provided here courtesy of Korean Association of Internal Medicine

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2012.27.2.128

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.kjim.org/upload/kjim-27-128.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.3904/kjim.2012.27.2.128

Article citations

Immunosenescence: How Aging Increases Susceptibility to Bacterial Infections and Virulence Factors.

Microorganisms, 12(10):2052, 11 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39458361 | PMCID: PMC11510421

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Assessment of antioxidant and antibacterial efficacy of some indigenous vegetables consumed by the Manipuri community in Sylhet, Bangladesh.

Heliyon, 10(18):e37750, 12 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39315213 | PMCID: PMC11417267

Fingolimod synergizes and reverses K. pneumoniae resistance to colistin.

Front Microbiol, 15:1396663, 30 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38873155

Genotypic and phenotypic mechanisms underlying antimicrobial resistance and synergistic efficacy of rifampicin-based combinations against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii.

Heliyon, 10(6):e27326, 06 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38524570 | PMCID: PMC10958224

Antimicrobial approach of abdominal post-surgical infections.

World J Gastrointest Surg, 15(12):2674-2692, 01 Dec 2023

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 38222012 | PMCID: PMC10784838

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (185) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Drug resistance phenotypes and genotypes in Mexico in representative gram-negative species: Results from the infivar network.

PLoS One, 16(3):e0248614, 17 Mar 2021

Cited by: 16 articles | PMID: 33730101 | PMCID: PMC7968647

Nationwide surveillance of antimicrobial resistance among clinically important Gram-negative bacteria, with an emphasis on carbapenems and colistin: Results from the Surveillance of Multicenter Antimicrobial Resistance in Taiwan (SMART) in 2018.

Int J Antimicrob Agents, 54(3):318-328, 14 Jun 2019

Cited by: 19 articles | PMID: 31202925

Cefiderocol: A Siderophore Cephalosporin with Activity Against Carbapenem-Resistant and Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli.

Drugs, 79(3):271-289, 01 Feb 2019

Cited by: 160 articles | PMID: 30712199

Review

An update on the management of urinary tract infections in the era of antimicrobial resistance.

Postgrad Med, 129(2):242-258, 21 Oct 2016

Cited by: 86 articles | PMID: 27712137

Review

1,2

1,2