Abstract

Free full text

Enantioselective Synthesis of a Hydroxymethyl-cis-1,3-cyclopentenediol Building Block

Abstract

A brief, enantioselective synthesis of a hydroxymethyl-cis-1,3-cyclopentenediol building block is presented. This scaffold allows access to the cis-1,3-cyclopentanediol fragments found in a variety of biologically active natural and non-natural products. This rapid and efficient synthesis is highlighted by the utilization of the palladium-catalyzed enantioselective allylic alkylation of dioxanone substrates to prepare tertiary alcohols.

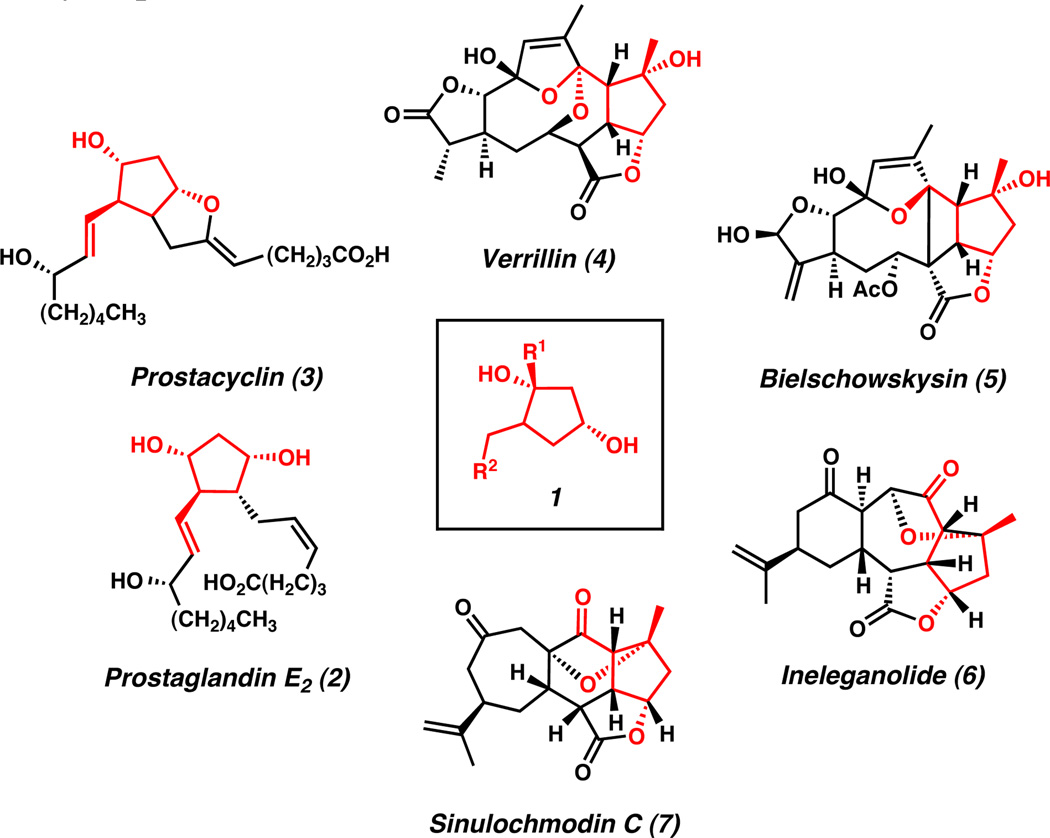

Functionalized cyclopentanol frameworks are an important structural motif in organic chemistry. Scaffolds of this type are found in many biologically active natural products,1 pharmaceuticals,2 and nucleoside analogs.3 In particular, cis-1,3-cyclopentanediols (1) have been extensively employed in the synthesis of medicinally relevant natural and non-natural compounds.3,4 For example, the biologically active prostaglandin (e.g., 2 and 3)2,5furanocembranoid diterpene (e.g., 4 and 5), and norcembranoid diterpene families of natural products (e.g., 6 and 7)1d,6 all contain the cis-1,3-cyclopentanediol motif (Figure 1).

Typically, enantioenriched carbocycles of this type have been accessed by kinetic enzymatic7 or classical8 resolutions. The utility of cis-1,3-cyclopentanediols which contain a tertiary alcohol is severely limited due to the challenges associated with the stereocontrolled formation of such chiral centers. Literature examples of the asymmetric synthesis of this moiety are limited to substrate-controlled diastereoselective alkylation4b or asymmetric oxidation of prochiral substrates.9 To the best of our knowledge, the enantioselective synthesis of the cis-1,3-cyclopentanediol scaffold has not been accomplished through asymmetric alkylation. As such, in concert with our research program dedicated to the development and application of the palladium-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation,10 we developed an efficient and general route for the enantioselective synthesis of cis-1,3-cyclopentanediol building block 1.

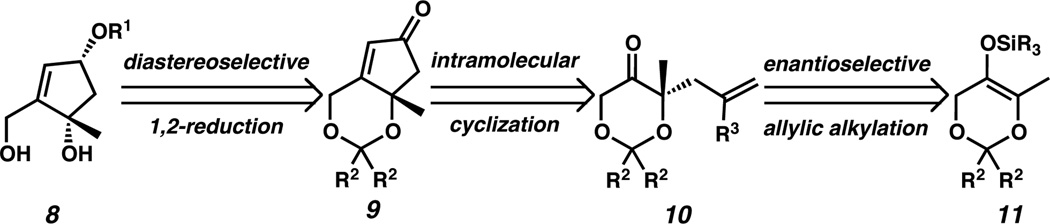

We envisioned that our asymmetric catalytic preparation of a cis-1,3-cyclopentanediol core (1) with additional functional handles would serve as an enabling technology for various total synthetic efforts. Specifically, we targeted diol 8, which can be synthesized from cyclopentenone 9 following diastereoselective reduction and ketal cleavage (Scheme 1). Intramolecular cyclization of dioxanone 10 would afford cyclopentenone 9. In turn, chiral dioxanone 10 would be prepared by palladium-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation of silyl enol ether 11.

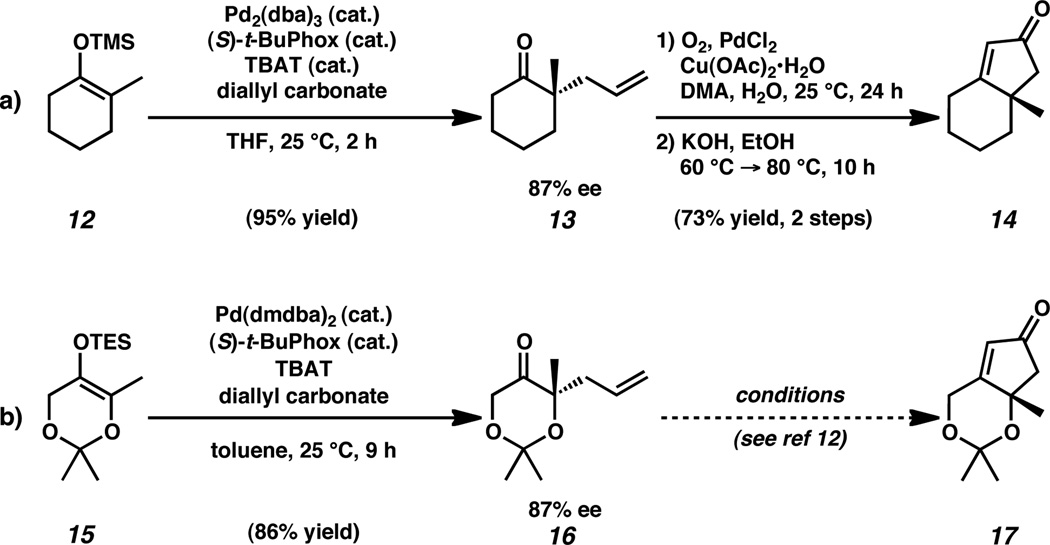

Our synthetic approach to cis-1,3-cyclopentenediol 8 was inspired by our previous report of the synthesis of related enone 14 (Scheme 2a).10a–b,10e The palladium-catalyzed asymmetric alkylation of enol ether 12 afforded allyl ketone 13 in 95% yield with 87% ee. Wacker oxidation of the allyl fragment to the intermediate methyl ketone followed by intramolecular aldol condensation generated cyclopentenone 14 in 73% yield over two steps from allylic alkylation product 13.

Enantioselective allylic alkylation and elaboration of cyclohexanone and dioxanone substrates. [TBAT = Bu4NPh3SiF2, DMA = N,N-Dimethylacetamide]

Similarly, dimethyl ketal 15 was converted to chiral ketal 16 in 86% yield and 87% ee through the enantioselective allylic alkylation procedure developed by our group (Scheme 2b).11 However, employment of the sequential Wacker oxidation–intramolecular aldol cyclization conditions were found to be ineffective, in preparing cyclopentenone ketal 17. Despite extensive exploration of alternative conditions for this transformation, formation of enone 17 was never observed.12

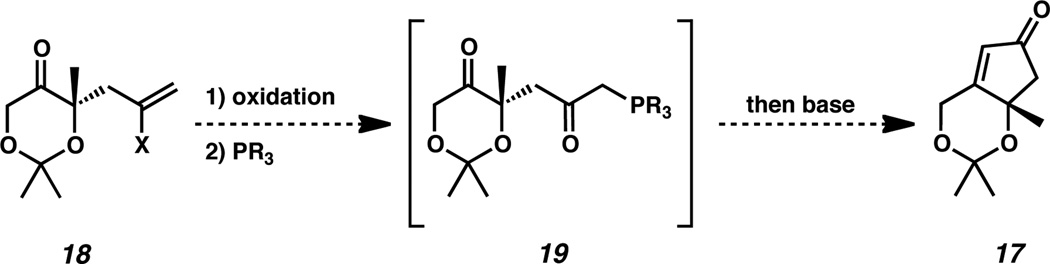

Faced with this challenge, we envisioned preparation of cyclopentenone 17 by an intramolecular Wittig cyclization (Scheme 3).13 The introduction of an oxidized allyl fragment during the alkylation event to generate ketone 18 could facilitate the olefinic oxidation. Subsequent nucleophilic substitution with a phosphine would generate Wittig precursor 19. Exposure to basic conditions could generate the phosphonium ylide, thus enabling an intramolecular Wittig cyclization to form cyclopentenone 17.

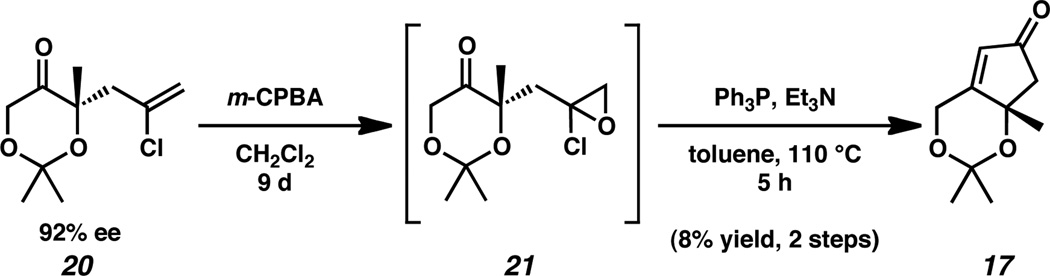

To explore this pathway, we began with chloroallylketone 20 which was prepared by palladium-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation in 59% yield and 92% ee by known procedure (Scheme 4).14 Epoxidation of ketone 20 with m-CPBA generated intermediate epoxide 21. Nucleophilic epoxide opening then formed the α-phosphinoketone in situ, enabling the construction of enone 17 by intramolecular Wittig cyclization. Although the yield for the two-step sequence was low and varied unpredictably, the desired cyclopentenone 17 could be isolated in small quantities.

Having accomplished proof of principle, we turned our attention to optimization. Despite screening a variety of epoxidation conditions,15 the synthesis of intermediate 21 proved difficult and remained low yielding. The Wittig cyclization had similar constraints, furnishing cyclopentenone 17 in variable, unsatisfactory yields.

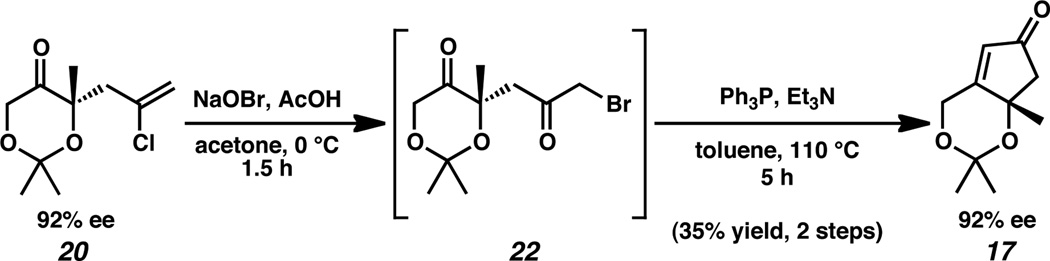

In spite of this failed optimization, we remained inspired by the successful isolation of the desired enone 17. As an alternative, we decided to explore the synthesis of other Wittig cyclization precursors. One appealing option was to target intermediate α-bromoketone 22 (Scheme 5).13 Oxidative bromination of vinyl chloride 20 with NaOBr in AcOH resulted in the formation of intermediate bromide 22. In situ displacement of the bromide by triphenylphosphine and subsequent intramolecular Wittig cyclization furnished cyclopentenone 17 with no erosion of enantiomeric excess, albeit in comparably unpredictable yields.

Synthetic advancement of dioxanone 20 through α-bromoketone 22 was plagued by vast inconsistencies and optimization proved difficult. The two-step sequence offered a range of yields from 0% to 82%. A variety of oxidative bromination conditions were attempted,15 yet consistent yields could not be achieved. Importantly, when intermediate 22 was successfully formed,16 conversion to cyclopentenone 17 could be reproducibly achieved with moderate success, indicating that the oxidative bromination was the problematic step in the sequence.

Upon closer inspection of the oxidative α-bromination procedure, we identified two possible sources of inconsistency. Firstly, we suspected that exposure of substrate 20 and intermediate 22 to acetic acid was causing the ketal cleavage of both compounds throughout the reaction, resulting in decomposition. Direct observation of this hypothesis was challenging, as the cleavage of the dimethyl ketal simply generated additional quantities of the reaction solvent, acetone. An additional source of variability arose as the scale of the reaction was increased. Over the lengthy time course of addition on greater scale (2 h), the NaOBr solution decomposes, lowering the reaction yield in the process.

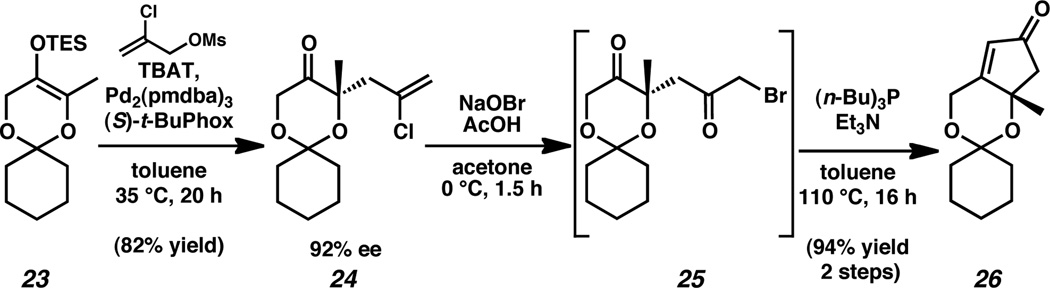

In order to address these concerns, we first sought to alter the ketal. The introduction of additional steric bulk was hypothesized to impart additional stability to the protecting group and thus its tolerance to the oxidative bromination conditions. Gratifyingly, the selection of the cyclohexyl ketal proved to have no deleterious effects on the asymmetric allylic alkylation of enol ether 23 (Scheme 6).17 Under optimized conditions,18 chloroallylketone 24 was generated in a greatly improved 82% yield and duplicated 92% ee in comparison to the dimethyl ketal allylic alkylation product 20.

Attempts to convert cyclohexyl ketal 24 to α-bromoketone 25 were met with consistent results and complete conversion could be reliably accomplished under optimized conditions,19 affording bromide 25 in nearly quantitative yield.20 As such, α-bromoketone was immediately advanced as a crude oil to cyclopentenone 26. Application of standard conditions for this transformation afforded enone 26, albeit in 35–40% yield.21 Modification of these conditions, including the use of (n-Bu)3P, enabled the conversion of bromide 25 to the desired cyclopentenone 26 in 94% yield over two steps from chloroallylketone 24.

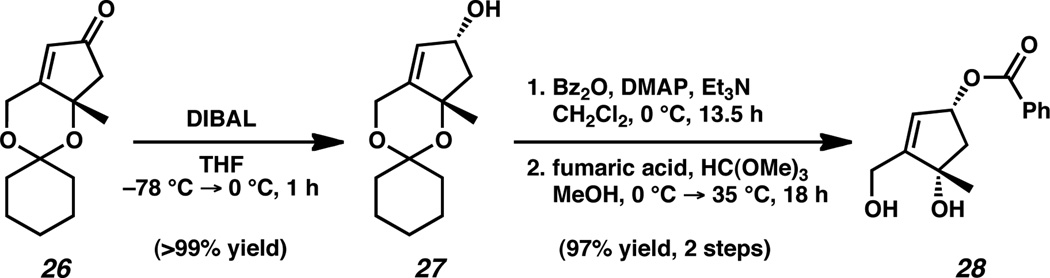

With the establishment of a scalable, reliable route for the production of cyclopentenone 26, we sought to advance toward the desired cis-1,3-cyclopentenediol 8. Diastereoselective 1,2-reduction of enone 26 with diisobutylaluminum hydride (DIBAL) cleanly furnished allylic alcohol 27 in excellent yield as a single diastereomer (Scheme 7).22 Sequential benzoylation of alcohol 27 and fumaric acid-mediated ketal cleavage yielded protected alcohol 28, a surrogate for the targeted cyclopentene 8. This three-step transformation from cyclopentenone 26 not only provided cis-1,3-cyclopentenediol building block 28 in 97% yield, but also proved to be scalable, allowing access the desired product in gram quantities.23

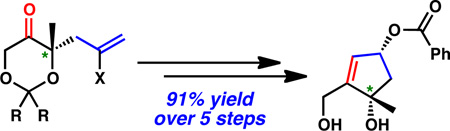

In summary, we have disclosed a highly efficient and scalable route for the construction of a cis-1,3-cyclopentenediol building block, enabling access to the cis-1,3-cyclopentanediol framework found in a variety of natural products and natural product analogs. The enantioselective palladium-catalyzed allylic alkylation has been used effectively to generate the desired chiral tertiary alcohol stereocenter. Judicious choice of the ketal protecting group allowed for successful optimization of the diastereoselective formation of the cis-1,3-diol framework, generating diol 28 in 91% yield over 5 steps from allylic alkylation product 24. Efforts are currently underway to employ this building block in the synthesis of members of the norcembranoid diterpene family of natural products.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank NIH-NIGMS (R01GM080269-01), the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program of the University of California, Grant Number 14DT-0004 (predoctoral fellowship to J.L.R.), Amgen, Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Caltech for financial support. Dr. Nathaniel Sherden, Dr. Masaki Seto, Dr. Pamela Tadross, Dr. Scott Virgil, Mr. Jeffery Holder, Mr. Corey Reeves, and Ms. Amanda Silberstein (Caltech) are thanked for helpful discussions and experimental support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental details and NMR spectra of all intermediates. These materials are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1021/ol3027297

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc3506031?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1021/ol3027297

Article citations

Total synthesis of (-)-scabrolide A and (-)-yonarolide.

Chem Sci, 14(18):4745-4758, 01 Apr 2023

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 37181769 | PMCID: PMC10173254

Recent Advances in Enantioselective Pd-Catalyzed Allylic Substitution: From Design to Applications.

Chem Rev, 121(8):4373-4505, 19 Mar 2021

Cited by: 53 articles | PMID: 33739109 | PMCID: PMC8576828

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

The Allylic Alkylation of Ketone Enolates.

ChemistryOpen, 9(9):929-952, 10 Sep 2020

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 32953384 | PMCID: PMC7482671

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Development of a Unified Enantioselective, Convergent Synthetic Approach Toward the Furanobutenolide-Derived Polycyclic Norcembranoid Diterpenes: Asymmetric Formation of the Polycyclic Norditerpenoid Carbocyclic Core by Tandem Annulation Cascade.

J Org Chem, 83(7):3467-3485, 19 Mar 2018

Cited by: 11 articles | PMID: 29464957 | PMCID: PMC5889334

Model Studies To Access the [6,7,5,5]-Core of Ineleganolide Using Tandem Translactonization-Cope or Cyclopropanation-Cope Rearrangements as Key Steps.

J Org Chem, 82(24):13051-13067, 21 Nov 2017

Cited by: 10 articles | PMID: 29111725 | PMCID: PMC5732049

Go to all (10) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation of barbituric acid derivatives: enantioselective syntheses of cyclopentobarbital and pentobarbital.

J Org Chem, 65(5):1569-1573, 01 Mar 2000

Cited by: 10 articles | PMID: 10814127

Palladium-Catalyzed Enantioselective Decarboxylative Allylic Alkylation of Cyclopentanones.

Org Lett, 17(21):5160-5163, 26 Oct 2015

Cited by: 13 articles | PMID: 26501770 | PMCID: PMC4640231

Enantioselective synthesis of 4-heterosubstituted cyclopentenones.

J Org Chem, 78(8):4202-4206, 01 Apr 2013

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 23544701

Enantioselective synthesis of α-quaternary Mannich adducts by palladium-catalyzed allylic alkylation: total synthesis of (+)-sibirinine.

J Am Chem Soc, 137(3):1040-1043, 20 Jan 2015

Cited by: 19 articles | PMID: 25578104 | PMCID: PMC4311947

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIGMS NIH HHS (3)

Grant ID: R01 GM080269

Grant ID: R01GM080269-01

Grant ID: F32GM082000