Abstract

Free full text

Early detection and management of pulmonary arterial hypertension

Abstract

The long-term prognosis for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) remains poor, despite advances in treatment options that have been made in the past few decades. Recent evidence suggests that World Health Organization functional class I or II patients have significantly better long-term survival rates than patients in higher functional classes, thus providing a rationale for earlier diagnosis and treatment of PAH. However, early diagnosis is challenging and there is frequently a delay between symptom onset and diagnosis. Screening programmes play an important role in PAH detection and expert opinion favours echocardiographic screening of asymptomatic patients who may be predisposed to the development of PAH (i.e. those with systemic sclerosis or sickle cell disease), although current guidelines only recommend annual echocardiographic screening in symptomatic patients. This article reviews the currently available screening programmes, including their limitations, and describes alternative screening approaches that may identify more effectively those patients who require right heart catheterisation for a definitive PAH diagnosis.

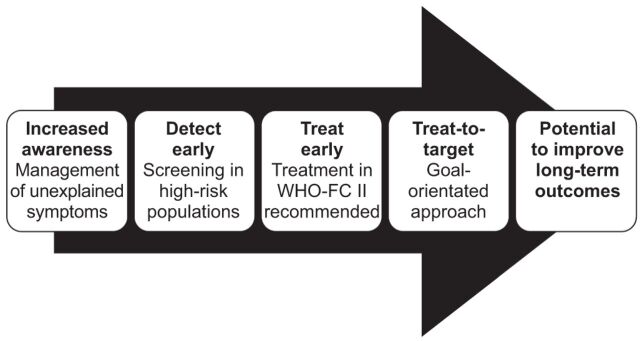

Despite updated guidelines and advances in treatment, the long-term prognosis for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) remains poor. Even in the modern management era, 1-yr mortality is estimated to be 8–15% in patients with idiopathic, familial/heritable or anorexigen-associated PAH [1, 2] and is ~30% in PAH associated with connective tissue disease [3]. Current guidance suggests that an early diagnosis of PAH and early therapeutic intervention may result in an improvement in long-term outcomes [1, 4–6]. The French Network on Pulmonary Hypertension registry enrolled patients with PAH who presented at 17 university pulmonary vascular centres in France between October 2002 and October 2003. The patients were followed up for 3 yrs. A study was conducted with the aim of assessing mortality in a prospective cohort of patients diagnosed with idiopathic, familial/heritable or anorexigen-associated PAH. The results demonstrated that PAH patients in World Health Organization functional class (WHO-FC) I/II had significantly better long-term survival than those patients in WHO-FC III/IV [1]. Additional evidence is provided by a retrospective, non-randomised, single-centre study of patients with Eisenmenger's syndrome that demonstrated that the 5-yr cumulative mortality rate in WHO-FC III/IV patients is significantly higher than the rate in WHO-FC I/II patients (32.2% versus 14.1%, p=0.006) [6]. In addition, data from a UK national registry demonstrated that treated patients with PAH-associated with systemic sclerosis (SSc), who were classified as WHO-FC III/IV, had twice the mortality risk compared with patients classified as WHO-FC I/II (p=0.002) [5]. Recent evidence demonstrates that PAH screening programmes in SSc are able to identify patients with milder forms of the disease, thereby allowing earlier therapeutic intervention and better survival [7]. These findings provide a strong rationale to support the early diagnosis and subsequent early management of PAH (fig. 1) recommended by current guidance [1, 2, 4, 5, 8].

The pathway to improving long-term outcomes in pulmonary arterial hypertension. WHO-FC: World Health Organization functional class.

However, the timely diagnosis of PAH is challenging for a number of reasons. Initially, the symptoms of PAH are usually very mild and non-specific, which is why it is so difficult to identify patients at this stage. As the disease progresses, non-specific symptoms such as breathlessness or fatigue develop. Consequently, the diagnosis of PAH is challenging and other conditions such as asthma, chronic heart failure, or even lack of fitness or depression are often considered before PAH [9]. In patients with SSc, co-existing musculoskeletal features and interstitial lung disease make PAH diagnosis even more of a challenge. This frequently results in a considerable delay between the onset of symptoms and PAH diagnosis. On average, the delay between symptom onset and diagnosis is ≥2 yrs [10], which is not substantially different from 25 yrs ago [11]. This means that PAH is rarely suspected until it has reached an advanced stage and prognosis is poor [9]. Although noninvasive detection options are expanding, a definitive diagnosis of PAH still requires right heart catheterisation (RHC).

SCREENING FOR PAH

Screening is defined as the systematic testing of asymptomatic individuals for pre-clinical disease. The purpose of screening and early detection is to identify mildly symptomatic patients, as well as those with pre-clinical disease in order to prevent or delay progression of disease through early treatment [12]. Screening programmes play an important part in the detection of PAH in certain at-risk populations and may enable patients to be identified at an earlier stage than in routine clinical practice [13]. The current European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines recommend annual echocardiographic screening in symptomatic (i.e. breathlessness, fatigue, weakness, angina, syncope and abdominal distension) patients. Furthermore, the guidelines state that annual echocardiographic screening “may be considered” in asymptomatic patients; a suggestion that is not substantiated by clinical data, but rather, by expert opinion [8]. Certain medical conditions and genetic susceptibilities are recognised as predisposing a person to the development of PAH. These include, but are not limited to, bone morphogenic protein receptor (BMPR)2 mutations, a first-degree relative with BMPR2 mutation, HIV infection, congenital heart disease with shunt, SSc, sickle cell disease and recent acute pulmonary embolism [14]. Risk factors for PAH and associated screening guidelines from the current American Consensus Document of the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF)/American Heart Association (AHA) are presented in table 1. The ACCF/AHA guidelines recommend that patients at sufficient risk for the development of PAH to warrant periodic screening include those with a known BMPR2 mutation, those with sickle cell disease, SSc patients and patients with portal hypertension who are undergoing evaluation for liver transplantation.

Table 1.

| Substrate | Further assessment |

| BMPR2 mutation | Echocardiogram yearly; RHC if echocardiogram demonstrates evidence of PAH (high right ventricular systolic pressure estimates or right heart chambers enlargement) |

| First-degree relative of patient with BMPR2 mutation or within pedigree of two or more patients with a diagnosis of PAH | Genetic counselling and recommendation for BMPR2 genotyping; proceed as above if positive |

| Systemic sclerosis | Echocardiogram yearly; RHC if echocardiogram demonstrates evidence of PAH (high right ventricular systolic pressure estimates or right heart chambers enlargement) |

| HIV infection | Echocardiogram if symptoms or signs suggestive of PAH; RHC if echocardiogram demonstrates evidence of PAH (high right ventricular systolic pressure estimates or right heart chambers enlargement) |

| Portal hypertension | Echocardiogram if OLT considered or if symptoms or signs suggestive of PAH; RHC if echocardiogram demonstrates evidence of PAH (high right ventricular systolic pressure estimates or right heart chambers enlargement) |

| Prior appetite suppression use (fenfluramaine) | Echocardiogram only if symptomatic |

| Congenital heart disease with shunt | Echocardiogram and RHC at time of diagnosis; consider repair of defect |

| Recent acute pulmonary embolism | V′/Q′ scintigraphy 3 months after event if symptomatic; consider echocardiogram, RHC and pulmonary angiogram if positive |

| Sickle cell disease | Echocardiogram yearly; RHC if echocardiogram demonstrates evidence of PAH (high right ventricular systolic pressure estimates or right heart chambers enlargement) |

BMPR2: bone morphogenic protein receptor; RHC: right heart catheterisation; OLT: orthotopic liver transplantation; V′/Q′: ventilation/perfusion ratio. Reproduced from [14] with permission from the publisher.

PAH is responsible for almost 30% of SSc-related deaths [3]. The value of screening for PAH in patients with SSc has been highlighted by the recent work of Humbert et al. [7]. In this prospective study, 16 SSc patients whose PAH was detected in a screening/early detection programme were compared with 16 SSc patients whose PAH was diagnosed during routine clinical practice. At the time of PAH diagnosis patients detected by screening had less advanced pulmonary vascular disease than patients identified in routine daily practice, as demonstrated by their lower mean pulmonary artery pressure, lower pulmonary vascular resistance and higher cardiac output [7]. At diagnosis, 6% of patients detected by screening were in WHO-FC I, 44% were in WHO-FC II, 50% were in WHO FC-III and none was in WHO-FC IV (fig. 2a and b). These results contrast sharply with those from the patients diagnosed in routine practice, in which the majority of patients were already in WHO-FC III or IV at the time of diagnosis (69% and 18.5%, respectively). Furthermore, none of the patients diagnosed with PAH during routine practice were in WHO-FC I at the time of diagnosis. Earlier detection of PAH in patients with SSc and earlier therapeutic intervention may have a major impact on long-term outcomes. PAH-SSc patients identified in the screening programme had significantly higher Kaplan–Meier survival estimates at 8 yrs than patients identified by routine daily practice (64% versus 17%; p=0.0037) (fig. 2c). These data highlight the importance of early detection and presumably early intervention on the long-term outcomes of patients with PAH-SSc.

Proportion of patients in each World Health Organization functional class (WHO-FC) at the time of pulmonary arterial hypertension-associated systemic sclerosis (PAH-SSc) in a) routine practice (n=16) and b) when detected as part of a screening programme (n=16). p=0.036 routine versus detected patients. c) Prognosis for PAH-SSc patients detected in routine practice (n=16) or via a screening programme (n=16). p=0.0037; HR 4.15 (95% CI 1.47–11.71). Reproduced from [7] with permission from the publisher.

LIMITATIONS OF EXISTING SCREENING REGIMENS

Screening for PAH, although warranted, is not without its challenges. Despite the recommendations by consensus groups and guidelines for annual screening in those at risk, there is limited evidence to support this directive. A number of unanswered questions remain. Which populations should be screened and how often? Which tools should be used? Can these tools be effectively combined to better predict the risk of PAH? The biggest problem with any test is how to calibrate the screening tool. If a screening test with a high specificity is used, this will ensure that the majority of patients identified do, indeed, have PAH. However, high specificity often comes at the expense of low sensitivity, more patients with PAH are likely to be missed. For instance, in the ItinérAIR-Sclérodermie screening study, the algorithm specificity was 97%. 33 out of 570 patients screened by Doppler echocardiography were referred for RHC (tricuspid regurgitation peak velocity (TRV) >3.0 m·s−1 or >2.5 to ≤3.0 m·s−1 with dyspnoea not attributable to other causes). PAH was confirmed in 14 patients (prevalence of 2.5%). This still represents a substantial rate of false positives (patients who underwent unnecessary RHC) and it is likely that many patients with PAH were missed [13]. If the screening test is recalibrated to a lower specificity, more individuals with PAH will be found, but at the expense of a greater number of false positives as more patients will undergo unnecessary RHC. Achieving the right balance between the number of RHC referrals and the rate of missed PAH diagnoses is a clinical, and possibly financial, dilemma for all of those involved. As a result, other means of screening, complementary to echocardiography, are being developed. In PAH-SSc for example, these include a simple scoring system, based on routine clinical observations [15] and a risk stratification formula for determining pulmonary function [16]; both of which can help to improve the selection of SSc patients for RHC.

Current screening programmes using only Doppler echocardiography have limitations. The ItinérAIR-Sclérodermie study demonstrated that echocardiography is less dependable as an indicator of PAH in patients with a TRV between 2.5 and 2.8 m·s−1 (i.e. patients with milder disease) [17]. Furthermore, in a recent study that investigated the sensitivity and specificity of TRV for detecting asymptomatic pulmonary hypertension (PH) in adults with sickle cell disease, raising the TRV threshold from ≥2.5 to ≥2.9 m·s−1 increased the positive predictive value from 25% to 64%; however, the number of false negative diagnoses was at least 42% [18]. Therefore, for asymptomatic patients with a TRV between 2.5 and 2.8 m·s−1, the use of echocardiography alone may be insufficient to screen for PH and the use of additional screening tools may be warranted.

Another issue to be considered is the performance of any screening test across disparate patient populations; prevalence of PAH in at-risk groups greatly influences the predictive value of the test. Table 2 presents a hypothetical example of an optimal screening tool that assumes a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 80%. In this example, 2.5 RHCs would need to be performed for every one SSc patient found to have confirmed PAH; a ratio that most clinicians would find acceptable. However, in the systemic lupus erythematosus population, 41 RHCs would be required to achieve one positive diagnosis of PAH and in idiopathic PAH, 101 RHCs would be required; a ratio that is unacceptable to most, both from a clinical and financial perspective. This example, although hypothetical, highlights the importance of calibrating the screening algorithm for the patient population being evaluated. In addition, screening tools perform differently in various populations, for example reduced diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DL,CO) appears particularly discriminatory in PAH-SSc, but has no relevance in idiopathic PAH. In the recent French study in patients with sickle cell disease-associated PH, 6-min walk distance (6MWD) appeared to have discriminatory value, whereas this tool has not been shown to be relevant in SSc populations [18]. Despite reports claiming that echocardiography has high sensitivity and specificity, such claims are not evidence based; sensitivity cannot be accurately estimated when the actual number of cases in the population being studied is unknown, and the true positive rate has been addressed in only one screening population [17] and was found to be <50% based on the current definition of PAH. Estimates of specificity in other studies have not focused on screening populations, and echocardiography is known to be more accurate in patients with advanced disease.

Table 2.

| Population | Prevalence¶ % | Accuracy % | PPV % | Screening tests/diagnosis | RHC/100 | RHC/diagnosis |

| PAH-SSc | 12.5 | 82 | 41 | 8.3 | 30 | 2.5 |

| PortoPH | 4 | 81 | 17 | 26.3 | 23 | 6.1 |

| PAH-SCD | 0.5 | 80 | 7 | 71.4 | 22 | 15.1 |

| PAH-SLE | 0.5 | 80 | 2 | 200 | 20 | 41 |

| Idiopathic PAH | 80 | 1 | 500 | 0.2 | 101 |

PPV: positive predictive value; RHC/100: number of right heart catheterisations required per 100 of population screened; RHC/diagnosis: number of right heart catheterisations performed for every patient diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH); PAH-SSc: PAH associated with systemic sclerosis; PortoPH: portopulmonary pulmonary hypertension; PAH-SCD: PAH associated with sickle cell disease; PAH-SLE: PAH associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. #: assumptions: 96% sensitivity; 80% specificity. ¶: assumed for each population based on available literature and may be underestimates.

ALTERNATIVE SCREENING REGIMENS

The suboptimal sensitivity and specificity of current screening strategies for high-risk populations emphasises the need for alternative approaches to improve the selection of patients for referral for RHC and definitive diagnosis. Screening tools currently available include Doppler echocardiography, assessment of dyspnoea, pulmonary function tests (PFTs) and serum biomarkers, such as N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) [15, 16, 19]. These tests screen for PAH using different biological mechanisms. It is unclear, at present, whether a combination of two or more of these tools may improve the specificity or sensitivity of screening analyses. In the ItinérAIR-Sclérodermie screening study, 195 patients had symptoms consistent with PAH. Gas transfer analyses determined that DL,CO was ≤60% predicted in 162 patients, of whom 13 (8%) had PAH. DL,CO was >60% pred in 404 patients of whom five (1.2%) had confirmed PAH [13]. This suggests that a combination of echocardiography and gas transfer analysis might be used to enrich the screening population.

Biomarkers may also have utility in screening for PAH. The findings of Allanore et al. [20] suggest that using a combination of PFTs and measurement of NT-proBNP may be a useful means of assessing patients for the presence or absence of PAH. It appears that, in the future, clinicians will be using a combination of clinical, serological and echocardiographic markers, as well as some novel indices (e.g. fractal dimensions of pulmonary vessels) to screen patients for PAH.

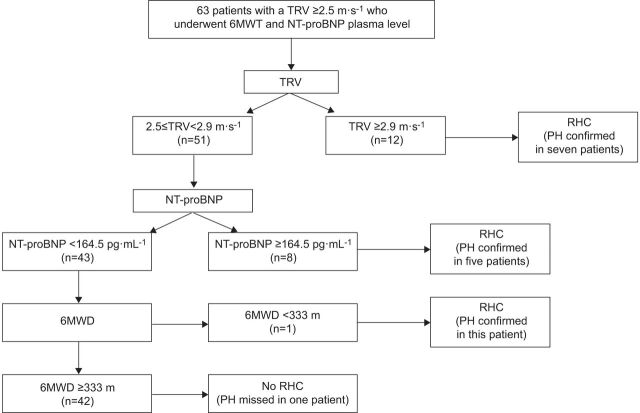

In a recent study of sickle cell disease patients with suspected PH, classification and regression tree (CART) analysis (using a sequential combination of echocardiographic parameters, NT-proBNP and 6MWD) was tested to determine whether patients should undergo RHC. For example, patients with a TRV ≥2.5 and <2.9 m·s−1 were categorised using NT-proBNP measurements; patients with an NT-proBNP ≥164.5 pg·mL−1 underwent RHC, whereas those with NT-proBNP <164.5 pg·mL−1 were further characterised by 6MWD. In the patients with a 6MWD <333 m, RHC would be performed [18]. On the basis of this approach, the positive predictive value of this method to detect PH was 62%, but the rate of false negatives was at least 7% (fig. 3).

Results of classification and regression tree analysis in patients with pulmonary hypertension-sickle cell disease. TRV: tricuspid regurgitant velocity; 6MWT: 6-min walk test; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; RHC: right heart catheterisation; PH: pulmonary hypertension; 6MWD: 6-min walk distance. Reproduced from [18] with permission from the publisher.

The rate of missed PAH diagnoses cannot be determined in any of the screening studies described previously because no study to date has conducted systematic RHC in the entire patient cohort. The DETECT study, conducted in SSc patients (with DL,CO<60% pred) is the first prospective study to evaluate the ability of a broad range of variables to predict PAH in SSc patients who underwent systematic RHC. Given the limitations of echocardiography, on which current screening recommendations are based, this study represents an important initiative, with the potential to provide valuable information on the value of different tools in the early detection of PAH [21]. To take advantage of any tool that allows early detection of PAH, however, it is first necessary to increase awareness among primary care physicians to achieve timely referral to specialist centres.

EARLY THERAPEUTIC INTERVENTION

Early identification of patients with PAH through effective screening programmes is vital since there is a growing body of evidence to support the role of early therapeutic intervention in this patient population. The importance of treating early is reflected in the current ESC/ERS guidelines, in which the evidence-based treatment includes specific recommendations for therapeutic intervention in WHO-FC II patients [8]. The results from a number of pivotal clinical trials add weight to this growing evidence base. For instance, SUPER (Sildenafil Use in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension)-2, the uncontrolled, open-label extension trial of SUPER-1, demonstrated that the majority of patients (60%) who entered SUPER-1 improved or maintained their functional status, and 46% maintained or improved 6MWD over the 3-yr study period [22]. The majority of patients who entered SUPER-1 were in WHO-FC II (39%) or III (58%), that is, patients with “mild” to “moderate” disease who, thereafter, derived significant benefit from early and prolonged treatment with sildenafil. The PHIRST (Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and Response to Tadalafil) trial showed that treatment with tadalafil (an orally administered, once daily, selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase type-5) improved exercise capacity and quality of life measures and reduced clinical worsening for patients with PAH, the majority of whom were WHO-FC II or III [23].

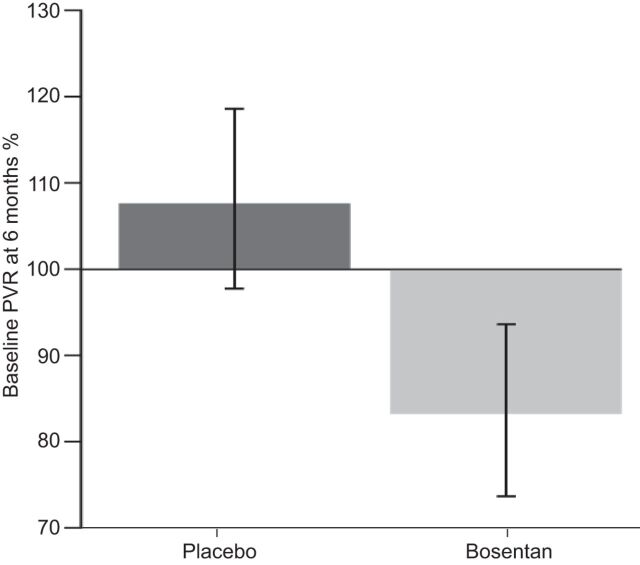

The impact of early therapeutic management was clearly demonstrated in the EARLY (Endothelial Antagonist Trial in Mildly Symptomatic Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Patients) study [24]. Prior to the EARLY study, the majority of clinical research with endothelin receptor antagonists (ERAs) and other PAH-specific therapies was carried out in patients in WHO-FC III or IV. EARLY was ground breaking because it recruited mildly symptomatic PAH patients in WHO-FC II. This randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study was designed to assess the effect of bosentan (an orally active, dual ERA) over a 6-month period in WHO-FC II PAH patients. The results demonstrated that at 6 months, geometric mean pulmonary vascular resistance was 83.2% (95% CI 73.8–93.7%) of the baseline value in the bosentan group and 107.5% (95% CI 97.6–118.4%) of the baseline value in the placebo group (treatment effect -22.6%, 95% CI -33.5– -10.0%; p<0.0001) (fig. 4). In addition, mean 6MWD increased from baseline in the bosentan group (11.2 m, 95% CI -4.6–27.0 m) and decreased in the placebo group (-7.9 m, 95% CI -24.3–8.5 m), with a mean treatment effect of 19.1 m (95% CI 3.6–41.8 m; p=0.0758). One of the key take-home messages from EARLY was that, despite the study being designed to encourage the enrolment of less compromised patients, deterioration was still seen in the haemodynamic, hormonal and clinical variables in the placebo group over 6 months [24]. Thus illustrating that PAH is a rapidly progressing disease even in the less advanced stages.

Effect of placebo (n=88) and bosentan (n=80) on the co-primary end-point pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) in the EARLY (Endothelial Antagonist Trial in Mildly Symptomatic Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Patients) study. Treatment effect= -22.6%, p<0.0001. Reproduced from [24] with permission from the publisher.

At the end of the 6-month period of the EARLY study, patients were permitted to enter an open-label extension study. The mean exposure to bosentan was 3.6±1.8 yrs, with 73% and 62% of patients being exposed to bosentan for ≥3 yrs and ≥4 yrs, respectively [25]. By the end of year 4, ~30% of patients were receiving additional medication for PAH. At the start of the extension phase, 94% of patients were in WHO-FC II. At the end of the study, WHO-FC was maintained in the majority of patients: 17.1% improved from WHO-FC II to WHO-FC I, 56.3% were maintained at WHO-FC II and 20.9% worsened to WHO-FC III/IV. Additionally, 6MWD remained stable in most patients throughout the duration of the study. At baseline, mean 6MWD was 443±90.5 m and at the end of the extension study was 439±119.7 m. In summary, the EARLY study demonstrated that PAH patients in WHO-FC II rapidly deteriorate without treatment and suggests that drugs such as bosentan will delay disease progression. The open-label extension study showed that the majority of patients remained in WHO-FC I/II during long-term treatment with bosentan alone or with additional medication for PAH.

Early therapeutic intervention is important for long-term prognosis. In a recent prospective analysis of 49 patients with PAH-SSc, patients previously treated with bosentan for 4 months, who were in WHO-FC I/II at month 4, had a much better prognosis than those patients in WHO-FC III or IV at month 4 [26]. The Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated that the overall survival estimates at 1, 2 and 3 yrs were 100%, 100% and 86%, respectively, in patients in WHO-FC I/II, and 78%, 38% and 38%, respectively, in patients in WHO-FC III/IV after 4 months of first-line bosentan therapy (p=0.007). It should be noted, however, that the benefits seen cannot be attributed to bosentan monotherapy alone, but are due to a combination therapy approach, with first-line monotherapy with bosentan and a prostanoid or sildenafil added if clinicians judged it to be necessary. It is therefore not possible to attribute outcome to any specific therapeutic agent. Moreover, this study had several limitations, including its open-label design, which means that the results need to be interpreted with caution. However, this study does underline the importance of performing a haemodynamic evaluation 4 months after the start of treatment as this may provide an indication of long-term prognosis.

Evidently early diagnosis and treatment of PAH is vital, especially in high-risk populations such as asymptomatic carriers of BMPR2 mutations. It is estimated that ~10–20% of patients with BMPR2 mutations will develop PAH. The DELPHI-2 study (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT01600898) is a 3-yr, prospective, follow-up of a cohort of asymptomatic carriers of the BMPR2 mutation. The objectives of the study are to: 1) assess the predictive factors of PAH development; 2) monitor clinical, functional, biological, echocardiographic and haemodynamic characteristics; 3) estimate the risk of occurrence of PAH; and 4) screen patients with PAH at an early stage of disease and hence to offer them early therapeutic intervention. The results of this trial are eagerly anticipated.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

In summary, although advances are being made, there is still a clear and unmet need for improvements in the diagnosis, characterisation and management of patients with PAH. An initial definitive diagnosis is often delayed for as long as 2 yrs from symptom onset and remains a significant challenge. Convincing evidence exists that screening for PAH in high-risk populations will allow early diagnosis and that early detection and intervention offer a promising opportunity to improve patient outcomes. However, the screening methods used routinely in clinical practice have limitations and it may be that a combination of screening tools or parameters will be required to improve the sensitivity and selectivity of current screening programmes. PAH is a rapidly progressing disease, even in patients with mild symptoms, and timely therapeutic intervention is essential to impact on the long-term prognosis for patients with PAH.

Acknowledgments

We received editorial assistance from L. Quine (Elements Communications Ltd, Westerham, UK) supported by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd (Allschwil, Switzerland).

Footnotes

Provenance

Publication of this peer-reviewed article was supported by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Switzerland (principal sponsor, European Respiratory Review issue 126).

Statement of Interest

M. Humbert has relationships with drug companies including Actelion, Aires, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GSK, Merck, Novartis, Nycomed, Pfizer, Stallergènes, TEVA and United Therapeutics. In addition to being an investigator in trials involving these companies, relationships include consultancy service and membership of scientific advisory boards. J.G. Coghlan has received support for consultancy work, lectures, conference attendance, staff posts and research from Actelion, Pfizer, GSK, Lilly, Novartis and United Therapeutics. D. Khanna has received consulting fees from Actelion, Genentech, Gilead, Pfizer, Intermune and United Therapeutics. He serves on the speaker bureaus of Actelion and United Therapeutics. He has received funding for research from Actelion, Gilead, the Scleroderma Foundation and United Therapeutics.

REFERENCES

Articles from European Respiratory Review are provided here courtesy of European Respiratory Society

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1183/09059180.00005112

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9487225

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Early detection of pulmonary arterial hypertension through [18F] positron emission tomography imaging with a vascular endothelial receptor small molecule.

Pulm Circ, 14(3):e12393, 26 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39072304 | PMCID: PMC11273098

Attitudes and barriers to pulmonary arterial hypertension screening in systemic sclerosis patients: A survey of UK-based rheumatologists.

J Scleroderma Relat Disord, 9(2):99-109, 13 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38910595

Treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with connective tissue diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Intern Emerg Med, 19(3):731-743, 20 Feb 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38378970 | PMCID: PMC11039558

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

International trends in pulmonary hypertension mortality between 2001 and 2019: Retrospective analysis of the WHO mortality database.

Heliyon, 10(4):e26139, 09 Feb 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38384545 | PMCID: PMC10879023

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia - associated pulmonary hypertension: An updated review.

Semin Perinatol, 47(6):151817, 09 Sep 2023

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 37783579 | PMCID: PMC10843293

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (79) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

Clinical Trials

- (1 citation) ClinicalTrials.gov - NCT01600898

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

[Pulmonary arterial hypertension and systemic sclerosis].

Presse Med, 35(12 pt 2):1929-1937, 01 Dec 2006

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 17159719

Review

Screening for pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with scleroderma--a New Zealand perspective.

N Z Med J, 127(1400):30-38, 15 Aug 2014

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 25145365

Addition of sildenafil to bosentan monotherapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Eur Respir J, 29(3):469-475, 01 Nov 2006

Cited by: 90 articles | PMID: 17079256

[Treatment with sildenafil, bosentan, or both in children and young people with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension and Eisenmenger's syndrome].

Rev Esp Cardiol, 60(4):366-372, 01 Apr 2007

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 17521545