Abstract

Free full text

EFFECT OF TRANSLOCATION DEFECTIVE REVERSE TRANSCRIPTASE INHIBITORS ON THE ACTIVITY OF N348I, A CONNECTION SUBDOMAIN DRUG RESISTANT HIV-1 REVERSE TRANSCRIPTASE MUTANT

Abstract

4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine (EFdA) is a highly potent inhibitor of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT). We have previously shown that its exceptional antiviral activity stems from a unique mechanism of action that is based primarily on blocking translocation of RT; therefore we named EFdA a Translocation Defective RT Inhibitor (TDRTI). The N348I mutation at the connection subdomain (CS) of HIV-1 RT confers clinically significant resistance to both nucleoside (NRTIs) and non-nucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTIs). In this study we tested EFdA-triphosphate (TP) together with a related compound, ENdA-TP (4′-ethynyl-2-amino-2′-deoxyadenosine triphosphate) against HIV-1 RTs that carry clinically relevant drug resistance mutations: N348I, D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F, D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F/N348I, and A62V/V75I/F77L/F116Y/Q151M. We demonstrate that these enzymes remain susceptible to TDRTIs. Similar to WT RT, the N348I RT is inhibited by EFdA mainly at the point of incorporation through decreased translocation. In addition, the N348I substitution decreases the RNase H cleavage of DNA terminated with EFdA-MP (T/PEFdA-MP). Moreover, N348I RT unblocks EFdA-terminated primers with similar efficiency as the WT enzyme, and further enhances EFdA unblocking in the background of AZT-resistance mutations. This study provides biochemical insights into the mechanism of inhibition of N348I RT by TDRTIs and highlights the excellent efficacy of this class of inhibitors against WT and drug-resistant HIV-1 RTs.

INTRODUCTION

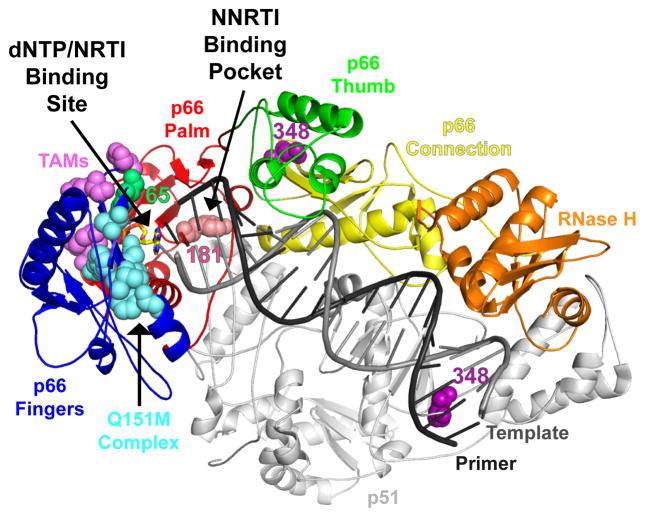

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase (HIV-1 RT) is a key enzyme that converts single-stranded genomic RNA into double-stranded DNA, which in turn is transported to the nucleus and integrated into the host cell genome. The HIV-1 RT catalyzes both the RNA- and DNA-dependent DNA polymerase, and RNase H activities (11). The functional form of HIV-1 RT is a heterodimer consisting of p66 and p51 polypeptides (16). The p66 subunit has both enzymatic activities and includes the polymerase and the RNase H domains. The polymerase domain consists of the fingers, palm and thumb subdomains which are analogous to a right hand connected to the RNase H domain through the connection subdomain (42) (Fig. 1).

The RT color scheme is as follows: fingers in blue, palm in red, thumb in green, connection in yellow, RNase H in orange, and p51 in gray. The Q151M complex is shown in cyan, TAMs in magenta, and 348 residue in purple. The RT coordinates are from PDB ID 1T05. The figure was made using PyMOL.

The p51 subunit lacks the RNase H domain and has been proposed to play a structural role (42), although recent work from our laboratory has also shown that mutations in the p51 subunit affect the polymerase and RNase H enzymatic functions of RT (38).

Highly active antiretroviral therapies (HAART) have been very effective in suppressing viral loads and having a significant impact on the life expectancy of HIV patients. Key components of HAART are drugs that target HIV RT. The two classes of RT inhibitors currently used in the clinic are nucleoside/nucleotide RT inhibitors (NRTI) and non-nucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTI). NRTIs inhibit RT by acting as chain-terminators after they are incorporated into the nascent DNA chain. NNRTIs act non-competitively by binding to a hydrophobic pocket adjacent to, but distinct from the polymerase active site of RT and by imposing rigidity to the movements of thumb subdomain required for efficient polymerase function (20, 22, 35, 37, 39, 41).

Despite the phenomenal success of HAART regimens, continuous use of antivirals leads to the emergence of viruses that are resistant to all known anti-AIDS drugs. The mutations associated with NNRTI resistance are generally located at the NNRTI binding pocket (NNIBP). However, the mutations that cause resistance to NRTIs have been noted to be scattered in the polymerase domain (22, 39). While most NNRTI and NRTI resistance mutations are at the palm and fingers subdomains of HIV-1 RT, it has recently been shown that some mutations associated with NNRTI and NRTI resistance are at the connection and RNase H regions of RT (6, 8, 13, 15, 17, 29, 43). The most significant of these mutations is N348I, which confers moderate resistance to both NRTIs and NNRTIs, and is present in a significant number of clinical isolates, especially in the presence of other NRTI mutations.

In light of the new emerging drug resistance mutations, it is essential to identify inhibitors that are very potent and effective against viral strains that are resistant to all approved therapeutics. One such inhibitor is 4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine triphosphate (EFdA-TP) (18, 19). We have recently reported the mechanism of HIV inhibition by EFdA (26). In contrast to other approved NRTIs, which have a modification at 3′OH, EFdA contains a 3′OH moiety and blocks DNA synthesis by locking the primer terminus at the pre-translocation site of HIV-1 RT. In addition to EFdA, we have recently shown that ENdA also inhibits HIV RT potently acting as a TDRTI (data not shown).

Recently, using transient-state kinetic experiments we established the mechanism of NNRTI resistance of HIV-1 RT containing the N348I mutation at the connection subdomain of the enzyme (38). We showed that the resistance to the NNRTI nevirapine (NEV) is primarily the result of changes distant from the NNRTI binding pocket, which decrease inhibitor binding (increase Kd-NVP) by primarily decreasing the association rate of the inhibitor (kon-NVP). Moreover, the N348I mutation increased nucleic acid binding affinity, enhanced processivity and lowered the catalytic turnover rate of the natural substrate. In this study we determine the ability of TDRTIs to block reverse transcription by the multi-drug resistant N348I HIV-1 RT as well as other NRTI resistant RTs, D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F (resistant to AZT by the excision mechanism) D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F/N348I, and A62V/V75I/F77L/F116Y/Q151M (multidrug resistant to AZT and dideoxynucleotide RT inhibitors).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Enzymes and Nucleic acids

The RT genes coding for p66 and p51 subunits of BH10 HIV-1 were cloned in the pETDuet-1 vector (Novagen) using restriction sites NcoI and SacI for the p51 subunit, and SacII and AvrII for the p66 subunit (2, 38). The sequences coding for a hexa-histidine tag and the 3C protease recognition sequence were added at the N-terminus of the p51 subunit. RT was expressed in BL21 (Invitrogen) and purified by nickel affinity chromatography and monoQ anion exchange chromatography (33). Oligonucleotides used in this study were chemically synthesized and purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Sequences of the DNA substrates are shown in Table 1. Deoxynucleotide triphosphates and dideoxynucleotide triphosphates were purchased from Fermentas (Glen Burnie, MD). EFdA and ENdA were synthesized by Yamasa Corporation (Chiba, Japan) as described before (30). Using EFdA and ENdA as starting material the triphosphate forms EFdA-TP and ENdA-TP were synthesized by TriLink BioTechnologies (San Diego, CA). Concentrations of nucleotides, EFdA-TP and ENdA-TP were calculated spectrophotometrically on the basis of absorption at 260 nm and their extinction coefficients. All nucleotides were treated with inorganic pyrophosphatase (Roche Diagnostics) as described previously (24) to remove traces of PPi contamination that might interfere with the rescue assay.

Table 1

DNA and RNA sequences used in this study.

| Polymerization experiments | |

|

| |

| Td31 | 5′-CCA TAG ATA GCA TTG GTG CTC GAA CAG TGA C |

| Tr31 | 5′-CCA UAG AUA GCA UUG GUG CUC GAA CAG UGA C |

| Pd18 | 5′-Cy3-GTC ACT GTT CGA GCA CCA |

|

| |

| Footprinting experiments | |

|

| |

| Td43 | 5′-Cy3-CCA TAG ATA GCA TTG GTG CTC GAA CAG TGA CAA TCA GTG TAGA |

| Pd30 | 5′-TCT ACA CTG ATT GTC ACT GTT CGA GCA CCA |

|

| |

| RNase H experiments | |

|

| |

| Tr35 | 5′-Cy3-GGA AAU CUC UAG CAG UGG CGC CCG AAC AGG GAC CU |

| Pd25 | 5′-AGG TCC CTG TTC GGG CGC CAC TGC T |

Primer extension assays

Inhibition of HIV-1 RT by TDRTIs

DNA template (Td31) was annealed to 5′-Cy3 labeled DNA primer (Pd18). To monitor primer extension, the Td31/5′Cy3-Pd18 hybrid (20 nM) was incubated at 37°C with WT or drug-resistant HIV-1 RTs (20 nM) in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.8) and 50 mM NaCl (RT buffer). Varying amounts of EFdA-TP or ENdA-TP were added and the reactions were initiated by the addition of 6 mM MgCl2 to a final volume of 20 μl. All dNTPs were present at a final concentration of 1 μM. The reactions were terminated after 15 minutes by adding equal volume of 100% formamide containing traces of bromophenol blue. The products were resolved on a 15% polyacrylamide 7 M urea gel. In this and in subsequent assays, the gels were scanned with a PhosphorImager (FujiFilm FLA 5000), the bands for fully extended product were quantified using Multi Gauge (FujiFilm) and results were plotted using one site competition equation on GraphPad Prism 4 to determine the IC50 for EFdA-TP and ENdA-TP.

Site-specific Fe2+ Footprinting Assay

Site-specific Fe2+ footprints were monitored on 5′-Cy3-labeled DNA templates. 100 nM of 5′Cy3-Td43/Pd20 was incubated with 600 nM WT or N348I RT in a buffer containing 120 mM sodium cacodylate (pH 7), 20 mM NaCl, 6 mM MgCl2, and either of 5 μM ddATP or 1 μM EFdA-TP, to allow quantitative chain-termination. Prior to the treatment with Fe2+, complexes were pre-incubated for 7 min with increasing concentrations of the next incoming nucleotide (dTTP). The complexes were treated with ammonium iron sulfate (1 mM) as previously described (21). This reaction relies on autoxidation of Fe2+ (3) to create a local concentration of hydroxyl radical which cleaves the DNA at the nucleotide closest to the Fe2+ specifically bound to the RNase H active site.

ATP-dependent Excision and Rescue assay

20 nM of purified Td31/Pd18-EFdA-MP or Tr31/Pd18-EFdA-MP were incubated with 60 nM WT, N348I, D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F or D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F/N348I RT in the presence of 3.5 mM ATP, 100 μM dATP, 0.5 μM dTTP, and 10 μM ddGTP in RT buffer and 10 mM MgCl2. Aliquots of the reaction were stopped at different time points (0–90 min) and analyzed as described above.

RNase H Assays

RNase H assays were performed by incubating the RNA/DNA duplex5′Cy3-Tr35/Pd25 or 5′Cy3-Tr35/Pd25-ddAMP or 5′Cy3-Tr35/Pd25-EFdA-MP (50 nM) with WT or N348I RT (50 nM) in RT buffer at 37 °C with MgCl2 (6 mM). Reactions were quenched after incubation (1–5 min) with equal volumes of formamide containing trace amounts of bromophenol blue. Reaction products were analyzed as before. The primary RNase H cleavage product is mainly 18 nucleotides from the 3′-end of the DNA primer (18 nucleotides), and the secondary cleavage product is mainly 12 nucleotides from the 3′-end of the primer (12 nucleotides) as reported previously (10, 12, 38).

RESULTS

The inhibitors used here to characterize the susceptibility of N348I to various drugs are adenosine analogs. The structures of these analogs are shown in Fig. 2. The normal deoxynucleotide dA is shown in Fig. 2A. EFdA and ENdA are shown in Figs. 2B and 2C, respectively. It can be seen in these figures that unlike other anti-HIV NRTIs both EFdA and ENdA have a 3′OH. These compounds also contain an ethynyl group at the 4′ position. EFdA and ENdA differ in their substitutions at the 2 position of the purine ring. EFdA at this position has fluorine whereas ENdA has an amino group.

Inhibition of WT and N348I mutant of HIV-1 RT

The inhibition of WT, N348I, D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F, D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F/N348I mutants of HIV-1 RT by EFdA-TP and ENdA-TP was assessed by a primer extension assay. As shown in Fig. 3A–3D, EFdA-TP and ENdA-TP suppressed RT-catalyzed DNA synthesis in a dose-dependent manner. The IC50 values for both analogs are shown in Table 2. N348I, D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F and D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F/N348I RTs were inhibited by EFdA-TP and ENdA-TP with similar efficiency compared to the WT enzyme. In addition, another mutant HIV-1 RT (A62V/V75I/F77L/F116Y/Q151M) was included in drug susceptibility assays (Fig. 3E).

(A) Td31/Pd18 was incubated with various HIV-1 RTs for 15 minutes in the presence of 1μM dNTPs, MgCl2 and increasing concentrations of EFdA-TP or ENdA-TP. The products synthesized by HIV-1 RT were quantified and plotted against increasing concentrations of the inhibitors. The IC50 values of the nucleotide analogs were determined by quantifying the percent of full extension and fitting the data points to GraphPad Prism 4 using one-site competition nonlinear regression (shown in Table 2). Arrows indicate the positions where dATP or dATP analogs are expected to be incorporated.

Table 2

IC50 values of EFdA-TP and ENdA-TP against WT and drug-resistant HIV-1 RTs

| Inhibitor/Enzyme | WT | N348I | D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F | D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F/N348I | A62V/V75I/F77L/F116Y/Q151M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| EFdA-TP (nM) | 130 | 122 | 157 | 217 | 121 |

| ENdA-TP (nM) | 71 | 54 | 98 | 110 | 85 |

We have previously shown that EFdA inhibits DNA synthesis at the point of incorporation. Thus, we examined here the stopping patterns after incorporation products of the primer extension assay for the stopping patterns (Fig. 3). The primer synthesis shown in Fig. 3 clearly demonstrates that the stopping pattern follows the incorporation of adenosine analogs. Three distinct bands at positions 1, 6 and 10 indicate that both analogs inhibit RT mainly at the point of incorporation. Therefore, these compounds act primarily as obligate chain terminators. There is also an additional band at position 7, suggesting that in some instances EFdA may allow addition of one nucleotide after its incorporation, thus acting as a delayed chain terminator (Fig. 3). This type of inhibition is far less common and is sequence-dependent. These finding agrees with our previous studies on WT RT (26).

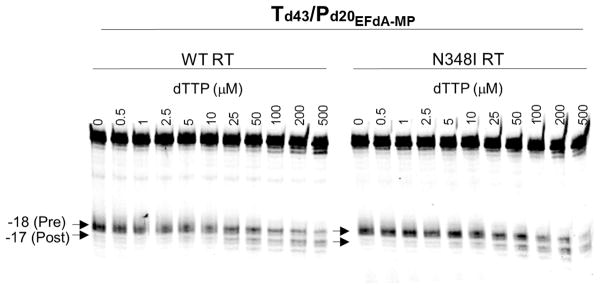

Effect of EFdA-MP on Translocation of WT and N348I mutant of HIV-1 RT

The connection subdomain mutation N348I has been related to the altered DNA binding affinity and processivity of the mutant enzyme compared to the WT RT (4, 38). Since EFdA is a TDRTI and its incorporation is assumed to affect the translocation and thereby DNA binding and processivity, we investigated the translocation of EFdA-containing template-primers using the hydroxyl radical site-specific footprinting assay (21). The results of the footprinting assay shown in Fig. 4 demonstrate that the presence of EFdA-MP at the 3′ end of the DNA primer blocks translocation and prevents incorporation of the next incoming dNTP. Therefore, similar to WT RT, the mutant N348I RT is also inhibited by EFdA-TP via the same mechanism.

The translocation state of RT after EFdA-MP incorporation was determined using site-specific Fe2+footprinting. Td43/P20-EFdA-MP (100 nM) with 5′-Cy3 label on the DNA template was incubated with HIV-1 RT (600 nM) and various concentrations of the next incoming nucleotide (dTTP). The complexes were treated for 5 min with ammonium iron sulfate (1 mM) and resolved on a polyacrylamide 7 M urea gel. An excision at position -18 indicates a pre-translocation complex, whereas the excision at position -17 represents a post-translocation complex. In both WT and N348I RT EFdA-MP prevents translocation with similar efficiency.

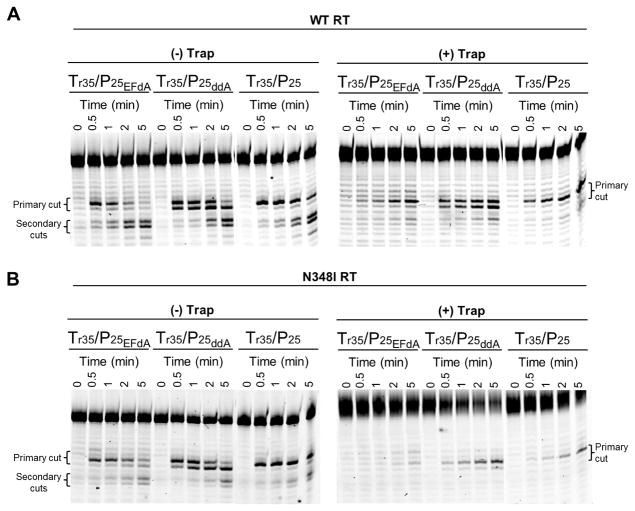

Effect of EFdA-MP on RNase H activity of WT and N348I RTs

The template/primers containing EFdA-MP, ddAMP, or without inhibitor incorporated at the 3′ end of the primer were used in RNase H assays with WT and N348I RTs in a time dependent manner. As previously noted, Fig. 5 shows that N348I mutant RT has decreased RNase H activity for all substrates used in this assay. The RNase H assays carried out in presence of T/P trap showed the disappearance of the secondary cuts for both enzymes used here. This is likely due to a defect in translocation that EFdA imposes on the enzyme. Interestingly, the primary cut of EFdA-terminated primers is a single band when the T/P has EFdA, but not ddA at the 3′ primer terminus. Moreover, the RNA cleavage of Tr35/Pd25 – EFdA-MP was less than that of Tr35/Pd25-ddAMP or Tr35/Pd25 possibly because of less favorable positioning at the RNase H of T/P with EFdA at the 3′ terminus.

50 nM Cy3-Tr35/Pd25 – EFdA-MP or Cy3-Tr35/Pd25-ddAMP or Cy3-Tr35/Pd25 was incubated with 50 nM WT (A) or N348I (B) HIV-1 RT for varying times (0–5 minutes) at 37°C in RT buffer. The experiment was carried out in the presence or absence of non-labeled Td35/Pd25 trap (25 μM). Reactions were initiated with the addition of MgCl2 and stopped with formamide. The primary and secondary cuts are indicated in the gel images.

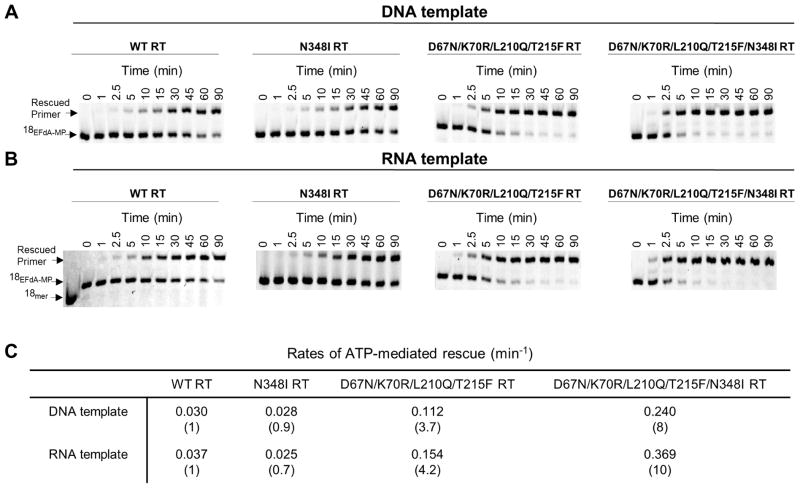

ATP-dependent unblocking of EFdA-MP terminated primers by WT and N348I RTs

Since EFdA-MP-terminated primers bind predominantly in a pre-translocation mode we expected that EFdA-MP will be efficiently unblocked by both WT and N348I RTs. The ATP-dependent excision and subsequent rescue of EFdA-MP primers is shown in Fig. 6. The bands marked as ‘Rescued Primer” have comparable product for the WT and N348I mutant enzyme for both DNA (Fig. 6A) and RNA (Fig. 6B) templates suggesting that resistance mutant N348I does not have any significant effect on the unblocking of EFdA-MP containing primers (RNA vs. DNA) (Fig. 6). However, the N348I mutation in the background of AZT resistance mutations D67N, K70R, L210Q and T215F showed a 2-fold increase in unblocking EFdA-MP containing primers both with DNA and RNA templates (Fig. 6).

ATP-dependent unblocking of EFdA-MP terminated primers. ATP-dependent rescue of Td31/Pd18-EFdA-MP (A) and Tr31/Pd18-EFdA-MP (B). Purified T/PEFdA-MP was incubated with WT, N348I, D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F or D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F/N348I HIV-1 RT in the presence of ATP (3.5 mM), dATP (100 μM), dTTP (0.5 μM), ddGTP (10 μM) and 10 mM MgCl2 at 37 °C. Aliquots of the reaction were stopped at the indicated time points (0–90 min). (C) The rates of the ATP-dependent rescue of EFdA-MP terminated primers were calculated after quantifying the rescued products and plotting to the burst equation in GraphPad Prism 4.

DISCUSSION

There are currently more than 20 antiretrovirals that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HIV infection. They fall into four categories, targeting HIV RT, protease, integrase, the entry step, and the fusion of the viral and cell membranes. RT inhibitors are either NRTIs or NNRTIs. The NRTIs such zidovudine (AZT) and lamivudine compete with the natural substrates and get incorporated into the nascent DNA chain, blocking further polymerization because they lack a 3′OH group required for DNA synthesis. NNRTIs such as nevirapine and efavirenz inhibit the polymerase activity of RT by binding at a hydrophobic pocket nearly 10 Å away from the polymerase active site (Fig. 1). This pocket is created after the binding of NNRTIs. The highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) introduced in the mid-90s contains the combination of antivirals (generally a protease inhibitor and two NRTIs or an NNRTI and two NRTIs) targets the replication of the resistant virus.

Extended or incomplete treatments with antiretrovirals result in the emergence of drug resistance mutations. In the case of drugs that target RT, most of the resistance mutations were found to be present in the polymerase domain of RT. These resistance mutations against NRTIs function primarily with two mechanisms: (i) they reduce the binding affinity/incorporation of NRTI (34, 40) or (ii) enhance the selective excision of incorporated NRTI from a chain-terminated primer terminus (9, 23–25, 36). The resistance against NNRTIs is primarily through the mutations that reduce the binding affinity of NNRTIs (7, 31, 32, 35).

Recent studies showed that connection subdomain mutations can confer resistance to NRTIs. Nikolenko et al. suggested that some of these mutations increase AZT resistance by reducing template RNA degradation, thereby preserving the RNA template and providing additional time for RT to excise AZT monophosphate (27, 28). Hachiya et al., (13) as well as another research group (43) identified a clinical isolate with phenotypic resistance to nevirapine (NVP) in the absence of known NNRTI mutations. This resistance was shown to be caused by N348I, a mutation at the connection subdomain of HIV-1 RT. This mutation is not a polymorphism, as it exists in more than 10% of drug-treated, but not drug-naïve HIV patients. The connection subdomain mutation N348I has been related to the altered DNA binding affinity and processivity of the mutant enzyme compared to the WT RT (4, 38). Ehteshami et al. showed that N348I enhances resistance to AZT through both RNase H-dependent and -independent mechanisms (10). Since EFdA is a TDRTI and its incorporation is assumed to affect the translocation and thereby DNA binding and processivity, we investigated the susceptibility of two highly potent antiretrovirals EFdA and ENdA.

We report that both EFdA-TP and ENdA-TP are very potent inhibitors of N348I, D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F, D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F/N348I, and A62V/V75I/F77L/F116Y/Q151M RTs. They inhibit RT primarily at the point of incorporation and since they prevent enzyme translocation they both belong to the TDRTI class of NRTIs. The D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F set of mutations are the classical thymidine-associated mutations (TAMs), which are known to cause resistance to AZT by enhancing excision of AZT-terminated primers (1, 5, 23). The A62V/V75I/F77L/F116Y/Q151M set of mutations is known as the “Q151M” complex RT, and has been known as a multidrug-resistance mutation, since the latter mutations are known to be involved in resistant variants with reduced susceptibility to dideoxynucleotides and to AZT. Unlike D67N/K70R/L210Q/T215F RT, the Q151M complex decreases susceptibility to NRTIs by decreasing incorporation efficiency of the inhibitors rather than increasing excision and unblocking of chain-terminated primers (14). Finally, N348I is known to cause resistance to both NRTIs and NNRTIs. Hence, collectively, these mutants represent all mechanisms by which RT becomes resistant to available antivirals. Importantly, we find that they are all susceptible to the EFdA and ENdA TDRTIs. Hence, this new class of RT inhibitors should be able to efficiently block viruses that carry clinically relevant mutations, including the new connection domain mutation N348I.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Knowledge and Economy, Bilateral International Collaborative Research and Development Program, Republic of Korea, National Institutes of Health Grants AI076119, AI074389, and AI100890 (to S. G. S.) and AI079801 (to M.A.P.).

Abbreviations

| EFdA | 4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine |

| ENdA | 4′-ethynyl-2-amino-2′-deoxyadenosine |

| NRTI | Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor |

| RT | Reverse transcriptase |

| T/PEFdA | Template/Primer terminated with 4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine |

| TDRTI | Translocation defective reverse transcriptase inhibitor |

| WT | wild-type |

References

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Article citations

EFdA efficiently suppresses HIV replication in the male genital tract and prevents penile HIV acquisition.

mBio, 14(4):e0222422, 12 Jun 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37306625 | PMCID: PMC10470584

Derivatives of mesoxalic acid block translocation of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase.

J Biol Chem, 290(3):1474-1484, 29 Oct 2014

Cited by: 7 articles | PMID: 25355312 | PMCID: PMC4340395

Drug resistance in non-B subtype HIV-1: impact of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors.

Viruses, 6(9):3535-3562, 24 Sep 2014

Cited by: 22 articles | PMID: 25254383 | PMCID: PMC4189038

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

SAMHD1 has differential impact on the efficacies of HIV nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors.

Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 58(8):4915-4919, 27 May 2014

Cited by: 21 articles | PMID: 24867973 | PMCID: PMC4136039

4'-Ethynyl-2-fluoro-2'-deoxyadenosine (EFdA) inhibits HIV-1 reverse transcriptase with multiple mechanisms.

J Biol Chem, 289(35):24533-24548, 26 Jun 2014

Cited by: 49 articles | PMID: 24970894 | PMCID: PMC4148878

Go to all (8) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Protein structures in PDBe

-

(1 citation)

PDBe - 1T05View structure

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Mechanism of inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by 4'-Ethynyl-2-fluoro-2'-deoxyadenosine triphosphate, a translocation-defective reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

J Biol Chem, 284(51):35681-35691, 01 Dec 2009

Cited by: 82 articles | PMID: 19837673 | PMCID: PMC2790999

Development of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Resistance to 4'-Ethynyl-2-Fluoro-2'-Deoxyadenosine Starting with Wild-Type or Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor-Resistant Strains.

Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 65(12):e0116721, 13 Sep 2021

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 34516245 | PMCID: PMC8597736

4'-Ethynyl-2-fluoro-2'-deoxyadenosine (EFdA) inhibits HIV-1 reverse transcriptase with multiple mechanisms.

J Biol Chem, 289(35):24533-24548, 26 Jun 2014

Cited by: 49 articles | PMID: 24970894 | PMCID: PMC4148878

HIV-1 reverse transcriptase connection subdomain mutations involved in resistance to approved non-nucleoside inhibitors.

Antiviral Res, 92(2):139-149, 28 Aug 2011

Cited by: 24 articles | PMID: 21896288

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIAID NIH HHS (10)

Grant ID: AI076119

Grant ID: R37 AI076119

Grant ID: R33 AI079801

Grant ID: AI100890

Grant ID: AI074389

Grant ID: AI079801

Grant ID: R01 AI074389

Grant ID: R21 AI079801

Grant ID: R01 AI076119

Grant ID: R01 AI100890