Abstract

Free full text

DNAJC13 mutations in Parkinson disease

Associated Data

Abstract

A Saskatchewan multi-incident family was clinically characterized with Parkinson disease (PD) and Lewy body pathology. PD segregates as an autosomal-dominant trait, which could not be ascribed to any known mutation. DNA from three affected members was subjected to exome sequencing. Genome alignment, variant annotation and comparative analyses were used to identify shared coding mutations. Sanger sequencing was performed within the extended family and ethnically matched controls. Subsequent genotyping was performed in a multi-ethnic case–control series consisting of 2928 patients and 2676 control subjects from Canada, Norway, Taiwan, Tunisia, and the USA. A novel mutation in receptor-mediated endocytosis 8/RME-8 (DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser) was found to segregate with disease. Screening of cases and controls identified four additional patients with the mutation, of which two had familial parkinsonism. All carriers shared an ancestral DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser haplotype and claimed Dutch–German–Russian Mennonite heritage. DNAJC13 regulates the dynamics of clathrin coats on early endosomes. Cellular analysis shows that the mutation confers a toxic gain-of-function and impairs endosomal transport. DNAJC13 immunoreactivity was also noted within Lewy body inclusions. In late-onset disease which is most reminiscent of idiopathic PD subtle deficits in endosomal receptor-sorting/recycling are highlighted by the discovery of pathogenic mutations VPS35, LRRK2 and now DNAJC13. With this latest discovery, and from a neuronal perspective, a temporal and functional ecology is emerging that connects synaptic exo- and endocytosis, vesicular trafficking, endosomal recycling and the endo-lysosomal degradative pathway. Molecular deficits in these processes are genetically linked to the phenotypic spectrum of parkinsonism associated with Lewy body pathology.

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson disease (PD) (OMIM 168600) is a common neurological disease affecting 1% of the population over the age of 65. It is clinically characterized by resting tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity and postural instability (1). To date, mutations in SNCA, LRRK2, EIF4G1 and VPS35 have been implicated in autosomal dominant, late-onset, Lewy body (LB) PD (2–8), whereas mutations in PRKN/PARK2, PINK1 and DJ-1/PARK7 have been observed in autosomal recessive early onset parkinsonism (9–11). Although Mendelian forms of parkinsonism are uncommon, their characterization has elucidated molecular mechanisms for disease and driven the creation of etiologic in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo models in which to test and develop novel therapeutics. To further our knowledge of the molecular etiology of disease, we have applied exome sequencing in multi-incident families with PD to identify additional genes and mutations (6).

We identified a Mennonite family of Dutch–German–Russian ancestry in which 13 family members have been diagnosed with PD (Fig. 1; SK1). This Mennonite deme originated in the Netherlands in the sixteenth century and migrated to German-speaking Prussia and southern Russia in the following centuries, before settling in Canada in the late-nineteenth century. DNA samples from affected family members were used to exclude all known mutations and copy number variants previously implicated in monogenic parkinsonism (2–11).

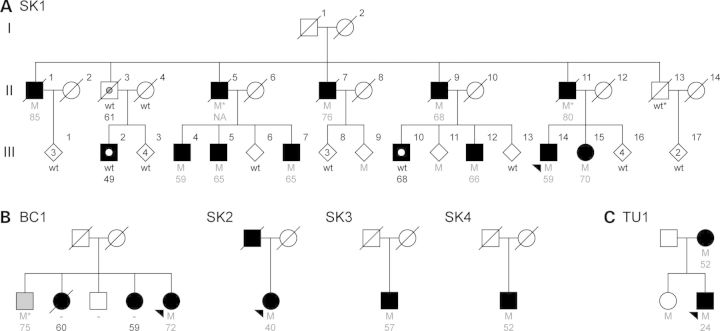

Pedigrees with DNAJC13 mutations. Individual pedigrees are labeled and numbered according to their geographic origin (SK, Saskatchewan, Canada; BC, British Columbia, Canada; TU, Tunisia). (A) Original family used for exome sequencing and identification of DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser. (B) Additional kindreds presenting DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser mutations. (C) Pedigree presenting the p.Arg2115Leu variant. Black-filled symbols indicate individuals diagnosed with PD, phenocopies are highlighted with a white circle, gray filled symbols indicate dementia, and gray circle indicates progressive supranuclear palsy. Heterozygote mutation carriers (M) with corresponding age at disease onset are indicated in gray and wild-type (wt) genotypes in black. An asterisk indicates an inferred mutation carrier.

This family consisted of 118 individuals over four generations, with DNA samples available from 57 family members, including 11 individuals diagnosed with PD and one with progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) (OMIM 601104). A simplified pedigree omitting those for whom DNA was not available, some spouses and the youngest generation is presented in Figure 1A. Disease transmission follows an autsomal-dominant inheritance pattern with a male predominance. The mean age of onset was 67.0 ± 9.5 years (SD). Death occurred after an average of 13.2 ± 4.1 years (SD), although one patient is still alive after 20 years of disease duration. The patients displayed slowly progressive, late-onset asymmetric parkinsonism with a combination of tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia and a good response to levodopa where tried. Detailed clinical description is provided in Supplementary Material, Table S1. Three patients presented pathology consistent with brainstem or transitional LB disease, and one patient presented tauopathy consistent with PSP. To identify the cause of disease in this family, we performed exome sequencing in three affected family members (SK1 II-7, III-4 and III-14). We identified disease-segregating variants and genotyped them in five large multi-ethnic case–control series including control subjects of Mennonite descent.

RESULTS

Exome analysis in three affected family members from SK1 (II-7, III-4 and III-14) identified sixteen novel missense and nonsense mutations common to all three individuals (Supplementary Material, Table S2). Sequencing of the amplicons containing these sixteen variants in the other nine family members diagnosed with PD or PSP and 117 unrelated healthy Mennonite controls from Canada resulted in the exclusion of fourteen variants. These were either identified in controls with a frequency over 2%, or were not deemed to cosegregate with disease, defined as more than two family members diagnosed with PD not carrying the variant. The remaining two variants, c.2564A > G (p.Asn855Ser) in DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily C, member 13 (DNAJC13; NM_015268.3) and c.791G > A (p.Arg264Gln) in zinc finger and BTB domain containing 38 (ZBTB38; NM_001080412.2), were present in all family members diagnosed with PD with the exception of SK1 III-2 and III-10 (Fig. 1). These two variants are separated by 9 Mb and were found to cosegregate in all family members. Two-point linkage analysis assuming a fully penetrant disease without phenocopies resulted in a logarithm of odds (LOD) score of 4.79 (θ = 0.05), adding a 10% phenocopy rate to the disease model increased the LOD score to 5.29 (θ = 0) thus, highlighting the high level of co-segregation with disease, strongly suggesting this region as the disease locus for this family despite not being shared by two affected family members.

Both variants were subsequently genotyped in a multi-ethnic case–control series consisting of 2928 cases and 2676 controls. This analysis did not identify additional patients with ZBTB38 p.Arg264Gln; however, two familial probands (BC1 and SK2) and two sporadic cases (SK3 and SK4) with DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser were found (Fig. 1B); neither mutation was observed in healthy controls. Segregation analysis in BC1 inferred one additional DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser carrier who had been diagnosed with dementia.

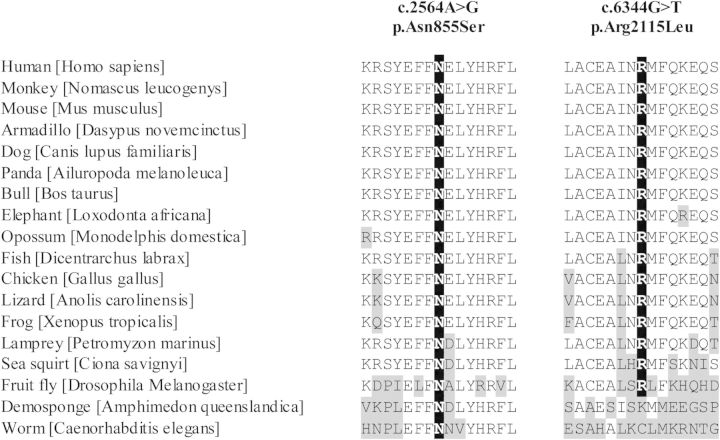

Haplotype analysis of DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser was performed with an Illumina OmniExpress 730k array and microsatellite markers between D3S3606 and D3S3684 (Table 1). Although phase could only be determined for SK1 and BC1, all mutation carriers were found to share several rare alleles across the disease haplotype, indicating that they are likely to descend from a common ancestor in whom the mutation originated. This is additionally supported by the Dutch–German–Russian Mennonite ancestry reported by all patients with the DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser mutation. To ensure that no other mutations in this haplotype were overlooked, any exons not examined by NGS were analyzed by Sanger sequencing; no further mutations were identified. These analyses indicate that DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser is a pathogenic mutation, whereas ZBTB38 p.Arg264Gln is a rare variant. Additional support of pathogenicity for DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser is provided by the high level of conservation from humans to worm observed at this position (Fig. 2); in contrast, ZBTB38 p.Arg264Gln is not evolutionarily conserved.

Table 1.

Chromosome 3q21.3-q22.2 haplotypes of kindreds with the DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser mutation

| Marker | Position | SK1 | BC1 | SK2 | SK3 | SK4 | CEPH/CEU frequency | Mennonite frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D3S3606 | 127 200 206 | 173 | 173 | 171/173 | 173/179 | 173/175 | 0.19 | 0.33 |

| D3S3607 | 127 272 891 | 144 | 144 | 144/154 | 144/160 | 144/164 | 0.11 | 0.07 |

| rs7629791 | 128 218 410 | G | G | G/A | A | G | 0.53 | – |

| D3S1587 | 130 798 818 | 215 | 215 | 215/217 | 215/223 | 215/223 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| D3S3514 | 131 580 046 | 260 | 260 | 260 | 260/266 | 258/260 | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| D3S1292 | 131 630 309 | 154 | 154 | 152/154 | 154/156 | 144/154 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| DNAJC13-Asn855Ser | 132 196 839 | G | G | G | G | G | – | – |

| D3S1273 | 132 826,238 | 118 | 118 | 112/118 | 116/118 | 114/118 | 0.11 | 0.07 |

| D3S1290 | 132 990 918 | 222 | 222 | 214/222 | 222 | 210/222 | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| D3S3657 | 133 425 958 | 261 | 261 | 261/263 | 261 | 261 | 0.34 | 0.47 |

| D3S3684 | 133 923 266 | 164 | 164 | 164/170 | 164/176 | 164/170 | 0.32 | 0.20 |

| rs9874260 | 134 659 551 | G | G/A | A | G/A | G/A | 0.32 | – |

Microsatellite allele sizes are given in base pairs consistent with Centre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH) standards. Markers are shown with their physical locations (NCBI Build 37.1). Shared haplotypes alleles are indicated in bold. For markers with an unknown phase both alleles are given. The frequency of disease-associated alleles were obtained from the CEU population for SNPs, the CEPH database and unrelated individuals of Dutch–German–Russian Mennonite ancestry (n = 30 chromosomes) for microsatellites.

DNAJC13 mutations and cross-species conservation. Protein orthologs were aligned via ClustalW. Amino acid positions for DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser and p.Arg2115Leu are highlighted in black. Protein orthologs with amino acid positions differing from those of the human sequence are indicated in gray. RefSeq accession numbers: Homo sapiens, NP_056083.3; Nomascus leucogenys, XP_003265273.1; Mus musculus, NP_001156498.1; Dasypus novemcinctus, ENSDNOP00000006627; Canis lupus familiaris, XP_542783.3; Ailuropoda melanoleuca, XP_002926293.1; Bos taurus, DAA33060.1; Loxodonta africana, XP_003420956.1; Monodelphis domestica, ENSMODP00000014684; Dicentrarchus labrax, CBN82117.1; Gallus gallus, ENSGALP00000019064; Anolis carolinensis, ENSACAG00000000850; Xenopus tropicalis, ENSXETG00000001850; Petromyzon marinus, ENSPMAP00000010330; Ciona savignyi, SINCSAVP00000001383; Drosophila melanogaster, NP_610467.1; Amphimedon queenslandica, XP_003383293.1; Caenorhabditis elegans, NP_492222.

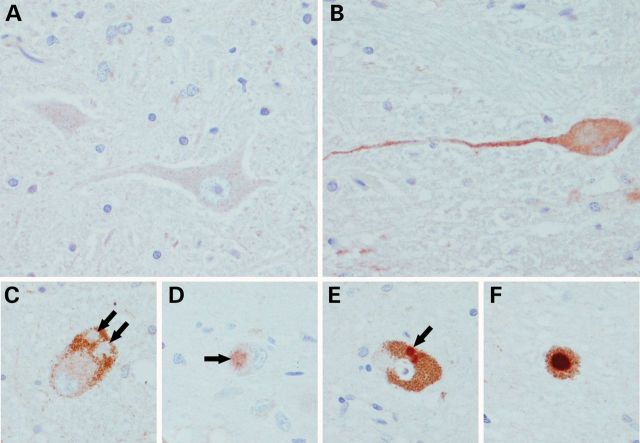

Disease onset for DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser mutation carriers in SK1 ranges between 59 and 85 years with an average age of 69.3 ± 8.6 years (SD). Six asymptomatic carriers were observed, four were at least 16 years younger than the average age at disease onset (data not shown) and two at the average onset age (70 and 71 years). Pathological examination for SK1 II-1, II-7 and II-9 was consistent with brainstem or transitional LB disease (data not shown). Immunological staining against DNAJC13 revealed finely granular cytoplasmic immunoreactivity in a subset of neurons in the dorsal motor nucleus of vagus, raphe nuclei, oculomotor nucleus and, to a lesser extent, the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus. Although fewer than 50% of LBs were labeled, staining appeared to be region specific; a lack of staining was observed for LBs in neurons of the locus coeruleus, weak staining in the dorsal motor nucleus and strong LB immunoreactivity in the substantia nigra (Fig. 3). SK1 II-3 did not present immunoreactivity in neuronal or glial tau-immunoreactive lesions characteristic of PSP, including neurons in the oculomotor nucleus. Normal control brains presented weak immunoreactivity to DNAJC13 antibody (data not shown).

Immunological staining of DNAJC13 in brain sections from p.Asn855Ser mutation carriers SK1 II-7 (A–C) and SK1 II-9 (D–F). (A) Negative staining in hypoglossal motor neurons. (B) Finely granular cytoplasmic immunoreactivity in dorsal motor nucleus of vagus. A subset of Lewy bodies (<50%) were positively labeled (arrows). Some Lewy bodies were completely unstained (C) two in a locus coeruleus neuron; others had weak staining (D) dorsal motor nucleus and some had dark immunoreactivity (E and F) substantia nigra.

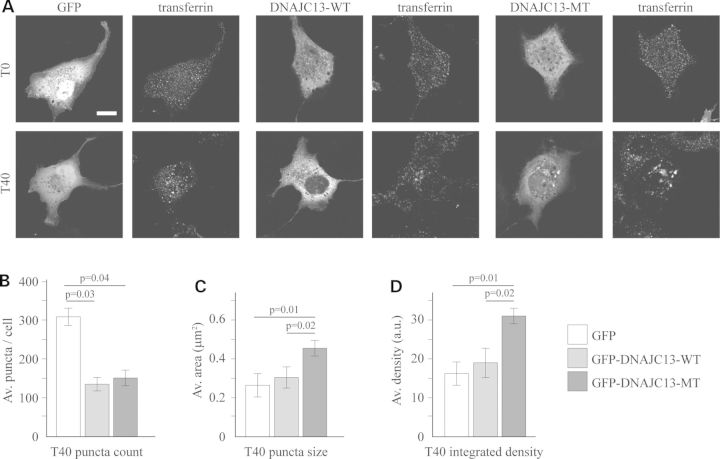

To investigate the physiological consequence of the DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser mutation, we assessed the uptake of transferrin (TF), a membrane receptor ligand that is constitutively internalized and recycled through the endosome pathway (12,13). COS7 cells expressing a GFP control, wild-type (WT) or mutant DNAJC13 were exposed to 568-conjugated TF for 1 h at 4°C and either fixed immediately (T0) or after a 40 min incubation at 37°C (T40). There were no differences in the TF signal at T0 in either DNAJC13 condition, relative to GFP alone (Fig. 4A), indicating that surface levels of TF were similar between groups. After 40 min of chase at 37°C, TF accumulated in perinuclear punctae in the GFP transfected control cells. In comparison, cells overexpressing WT DNAJC13 had fewer perinuclear TF clusters (0.55-fold; ANOVA P = 0.05, F2,6 = 5.20; Fisher's P = 0.03); potentially indicative of impaired endocytosis or more likely enhanced trafficking of TF out of the endosomes (Fig. 4). In cells overexpressing DNAJC13 mutant, there were also fewer clusters (0.59-fold) compared with GFP control (Fisher's P = 0.04), but those remaining were significantly brighter, that is the clusters covered a larger area (1.71-fold; ANOVA P = 0.02, F2,6 = 8.64; Fisher's P = 0.01) and had enhanced density (1.94-fold; ANOVA P = 0.02, F2,6 = 8.19; Fisher's P = 0.01) compared with GFP or GFP-DNAJC13-WT, as a result of increased size or density, indicative of increased endocytosis or more likely decreased trafficking out of the TF-labeled endosomes (12). The exact mechanism of mutant-induced alterations to endosomal trafficking will be the focus of future studies; however, it appears that the p.Asn855Ser mutation in DNAJC13 alters its cellular activity and the regulation of endosomal membrane trafficking.

Transferrin uptake in cells over expressing wild-type and mutant DNAJC13 protein. (A) COS7 cells were transiently transfected with either GFP, wild-type DNAJC13 (GFP-DNAJC13-WT) or DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser (GFP-DNAJC13-MT). Transferrin uptake assay was performed and cells imaged at T0 (prior to uptake) or T40 (40 min after chase). (B) Average number of transferrin positive puncta, (C) positive puncta size and (D) mean integrated density of puncta per cell 40 min after uptake. Statistically significant Fisher's LSD post hoc values are provided.

To identify if additional pathogenic mutations in DNAJC13 exist, we sequenced all 55 coding exons in 235 multi-ethnic familial probands from Canada, Norway, Taiwan and Tunisia. This analysis identified four novel silent (p.Ala283Ala, c.849G > A; p.Thr391Thr, c.1173A > T; Leu1038Leu, c.3112C > T; p.Pro1117Pro, c.3351C > T) and two missense variants (p.Thr1082Ile, c.3245C > T; p.Arg2115Leu, c.6344G > T) (Supplementary Material, Table S3; p.Thr1082Ile has been recently described in dbSNP; rs202127368). Both novel DNAJC13 missense variants were genotyped in the multi-ethnic case–control series identifying three PD patients and three controls with the p.Thr1082Ile variant, indicating this variant is rare and most probably benign. No additional carriers of p.Arg2115Leu were identified. Segregation analysis in the Tunisian kindred with p.Arg2115Leu identified two additional mutation carriers; however, only one diagnosed with PD (Fig. 1C). This kindred presents a very disparate age at disease onset, while the proband developed symptoms at age 24 his mother was healthy until age 52. The unaffected sister with the p.Arg2115Leu mutation, at age 46, had not been diagnosed with PD. Although the p.Arg2115Leu variant is very highly conserved (Fig. 2) and was not identified in controls, additional proof for pathogenicity is needed.

DISCUSSION

Exome sequencing analysis in a family of Dutch–German–Russian Mennonite ancestry presenting autosomal-dominant PD led to the identification of DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser mutations segregating with disease, with significant evidence for linkage. This mutation was not identified in 2676 control subjects, including 117 of Mennonite descent, nor in any public variant databases (14,15). DNAJC13 parkinsonism and idiopathic PD appear to be clinically and pathologically similar.

Two symptomatic family members (SK1 III-2 and III-10) did not carry the DNAJC13 mutation. The clinical presentation of disease in SK1 III-2 is somewhat distinct from all other affected carriers in the family. The age at disease onset for this patient (49 years) is >2 SD below the mean age at onset for p.Asn855Ser carriers. He presented with bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor and postural instability; additional clinical features include dystonia (left foot) and severe dyskinesias, and markedly dysarthric speech. A history of hesitancy, depression and REM behavior disorder were also present. After 20 years of disease, there are no signs of dementia or abnormal extraocular movements, and his level of disability fluctuates between stage 2 and 5. The disease symptoms are typical for advanced PD of long disease duration. His father, SK1 II-3, presented all cardinal signs of PD and in addition had pseudo bulbar affect, dysphagia, dementia and only a moderate response to levodopa. Clinical diagnosis of PSP was pathologically confirmed at autopsy. These findings suggest a different etiology for disease in this branch of the family. Clinical features for SK1 III-10 include right arm bradykinesia and rigidity, without signs of postural or resting tremor or significant functional impairment. Additional features include mild hypomimia and hypophonia providing an overall clinical diagnosis of early PD without need for treatment.

The pathogenicity of DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser is strongly supported by segregation with disease, the identification of five additional patients harboring the mutation, lack of healthy controls with the mutation and the high level of conservation across species. However, the presence of two phenocopies suggests other pathogenic mutations cannot be entirely excluded. Phenocopies in large pedigrees with PD are expected, and typically observed in 18–20% of autosomal-dominant families (16). To address this possibility, we sequenced the entire coding region of 115 genes known to be implicated in neurological disorders in SK1 II-3, III-2 and III-10 using a targeted capture panel. Despite this effort, none of the variants identified could account for disease in these patents; coding variants with a minor allele frequency under 5% are presented in Supplementary Material, Table S4.

DNAJC13, also known as RME-8, is a DNAJ-domain-bearing protein that localizes to the membranes of the endosomal system where it binds through its DNAJ-domain to the molecular chaperone heat shock cognate 70 (Hsc70) (HSPA8) (13). HSPA8 is a clathrin uncoating ATPase that has been most extensively studied for its role in the dissociation of clathrin from clathrin-coated vesicles (CCVs) (17). HSPA8 is also recruited to CCVs through interactions with the DNAJ-domain cofactor proteins auxilin (DNAJC6) or its homologue cyclin G-associated kinase (GAK) (17). It is interesting to note that mutations in DNAJC6 have been recently identified in juvenile parkinsonism (18), and genome-wide association studies have identified susceptibility alleles for PD at chromosome 4p16 spanning the GAK/DGKQ locus (19). Interestingly, DNAJC13 has also been shown to interact with the retromer component sorting nexin 1 (20). The retromer generates clathrin-independent carriers that mediate retrograde targeting of selective cargo from endosomes to the trans-Golgi network (21). DNAJC13 is thus thought to function by coordinating retromer with endosomal clathrin coats, either by regulating clathrin dynamics to allow for the sorting of cargo from clathrin subdomains into the retrograde vesicles or by creating clathrin-free patches on endosomal membranes allowing for sites of retromer-mediated vesicle formation (12,20). Preliminary functional analysis indicates that the expression of DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser in COS7 cells leads to accumulation of TF in endosomal compartments, suggesting interference with endosomal compartmentalization or trafficking as the pathological mechanism of disease. The importance of DNAJC13 function in endosomal trafficking is evident from several studies showing alterations in trafficking of well-known retromer cargos when its function is perturbed (13,20). The function of retromer itself is linked to PD through the observation that mutations in another retromer subunit, VPS35, can cause familial parkinsonism (6,7). Immunofluorescence and co-immunoprecipitation studies show endogenous VPS35 co-localizes with DNAJC13 in mouse primary cortical neuron cultures (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). Interestingly, LRRK2, in which mutations have been linked to late-onset PD (3,8), also co-immunoprecipitates with VPS35 (22). LRRK2 has a major role in autophagy (23), and genetic linkage and biological data have recently converged to nominate lysosomal impairment as a unifying molecular theme in early onset parkinsonism with LB pathology (24). However, in neurons LRRK2 plays a role in trans-Golgi protein sorting (25), morphogenesis (22) and synaptic endocytosis (26). Genetic variability in SNCA and MAPT are most commonly associated with familial and sporadic PD (27). In neurons, SNCA predominantly localizes to presynaptic terminals and is involved in the generation and maintenance of vesicle pools, chaperoning SNARE complex assembly and in synaptic vesicle recycling upon neuronal stimulation (28–31). Levels of SNCA and endophilin A1 are functionally related, and with LRRK2, likely contribute to synaptic exo- and endocytosis (26,32). The role of MAPT through the stabilization of microtubules plays a critical role in regulating axonal-dendritic transport, vesicle dynamics and plasticity (axonal growth and dendritic spine dynamics) (33). Thus, the discovery of a pathogenic mutation in DNAJC13, a component of the endosomal recycling system, also helps tether and unify past observations to emphasize the role of endosomal recycling rather than endolysosomal protein degradation in the biology of late-onset PD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and procedures

A large multi-incident family with PD and five independent PD patient control series consisting of 2928 cases and 2676 control subjects from Canada (including 117 of Mennonite descent), Norway, Taiwan, Tunisia and the USA were included. The demographics for each series are presented in Supplementary Material, Table S5. All patients were examined and observed longitudinally by a movement disorders neurologist and diagnosed with PD according to published criteria (34). Dementia was evaluated using mini-mental state examination (MMSE). Unrelated controls of identical ethnicity, without evidence of neurological disease, were consecutively sampled. The ethical review boards at each institution approved the study, and all participants provided informed consent.

Exome sequencing

Exonic regions were captured using Agilent SureSelect 38Mb Human All Exon Kit and subsequently sequenced in an Illumina Genome Analyzer by 76 bp paired-end reads with a minimum average coverage of 30 reads per base. Short reads were mapped to NCBI Build 37.1 reference genome using firstly Bowtie 12.70 and secondly Burrows-Wheeler Aligner 0.5.9 for unaligned reads (35,36). Reads presenting multiple alignments were discarded to avoid false-positive variant prediction. Local realignment around insertions and deletions was performed via GATK (37). Sequences with a mapping Phred quality score under 20 were excluded from further analysis. SAMtools was used to call variations relative to the human genome reference (38); variants observed with fewer than two reads or having quality score under 30 were omitted. Exclusion of frequently observed variants (minor allele frequency >1%) was achieved by comparison with publicly available and proprietary databases of variants. Rare and novel variants were analyzed by SIFT to identify those resulting in missense and nonsense substitutions (39).

Sequencing and genotyping analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes using standard protocols. Primer pairs were used to sequence amplicons containing novel variants and all 55 coding exons and exon–intron boundaries of DNAJC13 (NM_015268.3) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Supplementary Material, Table S6). PCR products were purified from unincorporated nucleotides using Agencourt bead technology (Beverly, MA, USA) with Biomek FX automation (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). Sequence analysis was performed as previously described (40). All novel variants were examined for disease segregation in affected and unaffected family members by additional sequencing. Evidence for segregation with disease was assessed using parametric linkage analysis, as previously described (2). All potentially pathogenic mutations were genotyped in case–control series using TaqMan probes; and mutations carriers confirmed by direct sequencing. Novel variants from exome and sequencing analysis have been submitted to the dbSNP-polymorphism repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/).

Haplotype analysis

Microsatellite markers were chosen to span the DNAJC13 locus between D3S3606 and D3S3684 (Table 1). One primer of each pair was labeled with a fluorescent tag and PCR reactions were performed under standard conditions. Products were run on an ABI 3730 genetic analyzer, and the results were analyzed using GeneMapper 4.0 (Applied Biosystems). Marker sizes were normalized to those reported in the CEPH database.

Construct design, cell culture and transfection

A cDNA clone encoding a GFP-fused human DNAJC13 was a gift from Dr Sekiguchi (Osaka University, Japan) (12). The p.Asn855Ser mutation was inserted by site-directed mutagenesis (primers available on request). GFP-DNAJC13 was then subcloned into a TOPO vector (Addgene) and restriction digestion with BamHI and EcoRV was used to replace GFP in CAG-AAV-GFP with WT or mutant GFP-DNAJC13. COS7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells were plated on coverslips for 24 h prior to transfection with GFP, WT or mutant DNAJC13 using TurboFect (Fermentas) according to manufacturer's instructions.

Transferrin uptake assay, imaging and analysis

Cells were incubated in serum-free DMEM + 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma) for 45 min at 37°C with 5% CO2 prior to incubation with 30 µg/ml transferrin Alexa Fluor® 568 (Invitrogen) in serum-free DMEM + 0.1% BSA for 1 h at 4°C. Cells were then either fixed immediately in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min or placed at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 40 min prior to fixation. Images were acquired with fixed settings on a Fluoview1000 confocal microscope (Olympus Inc., 60 × /1.4 Oil Plan-Apochromat). Cells were masked using the GFP channel and transferrin integrated density (product of cluster area and mean intensity) was quantified by an experimenter blinded to conditions. Statistical analyses were performed in Graphpad Prism 5 using ANOVA and Fisher's Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc test.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Canada Excellence Research Chairs program; Leading Edge Endowment Funds from the Province of British Columbia, LifeLabs; Genome BC support the Dr. Donald Rix BC Leadership Chair (M.J.F.); the Cundhill Foundation (A.J.S. and M.J.F.); Canada Research Chair program (C.V.-G.); Regina Curling Classic for Parkinson Research and Greystone Golf Classic for Parkinson's and Royal University Hospital Foundation (A.R., A.H.R.); the Pacific Parkinson's Research Institute (S.A.C.); Canadian Institutes of Health Research (M.J.F. and A.J.S.) and the Pacific Alzheimer Research Foundation (A.J.S. and S.A.C.). Clinicogenetic studies in Tunisia were funded in part by the Institute of Neurology, Tunis, and the Michael J. Fox Foundation. GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) funded and provided a subset of the Tunisian case control samples and associated phenotypic data. Mayo Clinic Florida is partially supported by the Morris K. Udall Center of Excellence for Parkinson's Disease Research (NIDNS P50NS072187 to D.W.D., O.A.R. and Z.K.W.).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our special thanks go to the many patients and families who took part, for their humanitarian gift.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

Articles from Human Molecular Genetics are provided here courtesy of Oxford University Press

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddt570

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc3999380?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1093/hmg/ddt570

Article citations

Parkinson's disease gene, Synaptojanin1, dysregulates the surface maintenance of the dopamine transporter.

NPJ Parkinsons Dis, 10(1):148, 08 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39117637 | PMCID: PMC11310474

Parkinson's Disease Gene Screening in Familial Cases from Central and South America.

Mov Disord, 39(10):1843-1855, 25 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39051491

Emerging perspectives on precision therapy for Parkinson's disease: multidimensional evidence leading to a new breakthrough in personalized medicine.

Front Aging Neurosci, 16:1417515, 04 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39026991 | PMCID: PMC11254646

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Diverse Functions of Parkin in Midbrain Dopaminergic Neurons.

Mov Disord, 39(8):1282-1288, 10 Jun 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38858837

Review

Dysregulation of SNX1-retromer axis in pharmacogenetic models of Parkinson's disease.

Cell Death Discov, 10(1):290, 17 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38886344 | PMCID: PMC11183211

Go to all (166) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Diseases (2)

- (1 citation) OMIM - 168600

- (1 citation) OMIM - 601104

Ensembl Genome Browser (Showing 6 of 6)

- (1 citation) Ensembl - ENSXETG00000001850

- (1 citation) Ensembl - ENSDNOP00000006627

- (1 citation) Ensembl - ENSMODP00000014684

- (1 citation) Ensembl - ENSPMAP00000010330

- (1 citation) Ensembl - ENSGALP00000019064

- (1 citation) Ensembl - ENSACAG00000000850

Show less

Nucleotide Sequences (2)

- (1 citation) ENA - DAA33060

- (1 citation) ENA - CBN82117

RefSeq - NCBI Reference Sequence Database

- (1 citation) RefSeq - NM_015268.3

SNPs (3)

- (1 citation) dbSNP - rs9874260

- (1 citation) dbSNP - rs202127368

- (1 citation) dbSNP - rs7629791

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser mutation screening in Parkinson's disease and pathologically confirmed Lewy body disease patients.

Eur J Neurol, 22(9):1323-1325, 01 Sep 2015

Cited by: 15 articles | PMID: 26278106 | PMCID: PMC4542017

DNAJC13 mutation screening in patients with Parkinson's disease from South Italy.

Parkinsonism Relat Disord, 55:134-137, 04 Jun 2018

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 29887357

DNAJC13 p.Asn855Ser, implicated in familial parkinsonism, alters membrane dynamics of sorting nexin 1.

Neurosci Lett, 706:114-122, 11 May 2019

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 31082451

LRRK2: a common pathway for parkinsonism, pathogenesis and prevention?

Trends Mol Med, 12(2):76-82, 10 Jan 2006

Cited by: 65 articles | PMID: 16406842

Review