Abstract

Free full text

Stillbirth During Infection With Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus

Abstract

We conducted an epidemiologic investigation among survivors of an outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection in Jordan. A second-trimester stillbirth occurred during the course of an acute respiratory illness that was attributed to MERS-CoV on the basis of exposure history and positive results of MERS-CoV serologic testing. This is the first occurrence of stillbirth during an infection with MERS-CoV and may have bearing upon the surveillance and management of pregnant women in settings of unexplained respiratory illness potentially due to MERS-CoV. Future prospective investigations of MERS-CoV should ascertain pregnancy status and obtain further pregnancy-related data, including biological specimens for confirmatory testing.

New cases and clusters of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infections continue to occur sporadically in the Middle East, Arabian Peninsula, and Europe [1]. MERS-CoV is a novel coronavirus known to cause acute respiratory illness typically associated with fever, which can progress rapidly to respiratory failure and, in some patients, renal failure. There has been no information yet published regarding the impact of MERS-CoV infections on pregnancy outcomes.

METHODS

In May 2013, epidemiologists from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) joined the Jordan Ministry of Health and regional partners to conduct a retrospective investigation of an April 2012 outbreak of respiratory illness, using newly developed serologic tests for detection of MERS-CoV antibodies. After the discovery of MERS-CoV, retrospective diagnoses of MERS-CoV infection were assigned to 2 individuals who died during this outbreak, based on findings of real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and were reported to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Serum specimens were collected and epidemiologic data were obtained from potentially exposed groups, including outbreak survivors and household contacts, through medical chart reviews and interviews. Household members were considered eligible for enrollment if they reported usually sleeping under the same roof as an outbreak member during the outbreak period, which lasted from February through April 2012. The initial outbreak case definition included “any case admitted [to the hospital] or their close contacts, who complained of fever and dry cough with radiological evidence of pneumonia during the period from 15 March to 30 April,” which identified 13 individuals, including the 2 fatal cases [2].

Interviews focused on a range of topics, including the history of illness, detailed contact history (with surviving outbreak group members, the household members of outbreak group members, visiting travelers, and animals), travel history, and occupation.

MERS-CoV antibody positivity was defined as a positive result of the HKU5.2N enzyme immunoassay (EIA) [plasmid provided by the University of Hong Kong, courtesy of Dr. Susanna Lau] and a correlated positive result of either the MERS-CoV immunofluorescence assay (IFA) or the MERS-CoV_(Hu/Jordan-N3/2012) microneutralization titer assay (MNt) developed at the CDC.

RESULTS

During the course of the MERS-CoV outbreak investigation in Zarqa, Jordan, we obtained data and specimens from 11 subjects in the initial outbreak group and from 26 subjects who resided in the same households as subjects in the initial outbreak group during the outbreak period. One household was lost to follow-up, and 1 did not consent for participation. Six of these 37 subjects (16%) were women aged 18–45 years. Three (50%) reported being pregnant during the outbreak period. Two of the pregnancies reportedly resulted in miscarriage, but both mothers tested negative for MERS-CoV antibody.

The third pregnant woman, aged 39 years, had a stillbirth at approximately 5 months of gestation, and her laboratory results were positive for MERS-CoV antibody by EIA (titer, 1:1600), IFA, and MNt (titer, 80). During the outbreak period, her acute respiratory symptoms (fever, rhinorrhea, fatigue, headache, and cough) occurred concurrently with vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain on the seventh day of illness, and she spontaneously delivered a stillborn infant.

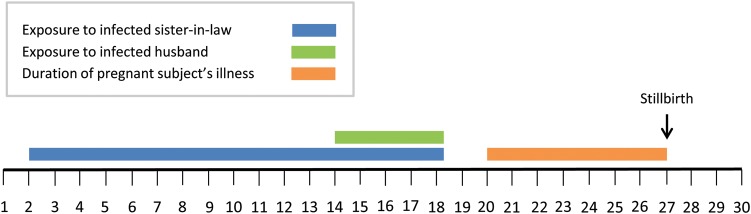

The pregnant subject's onset of respiratory symptoms occurred 7 days following the onset of her husband's symptomatic acute respiratory illness; he also tested positive for MERS-CoV antibodies by all 3 serologic tests (EIA titer, 1:400; IFA, MNt titer, 40). Additionally, she had another close relative who died of a MERS-CoV infection, confirmed by real-time RT-PCR, 1 day before the date of onset of the pregnant subject's symptoms. The pregnant subject reported having unprotected exposures to both of these family members during their symptomatic MERS-CoV illnesses (Figure (Figure11).

Timeline of events associated with a stillbirth attributable to Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection, 1–30 April 2012.

The pregnant subject refused medical care during her illness because of stated concerns about undergoing chest radiography and receiving medications during pregnancy. As is common in this region, fetal specimens were not retained and were not available for retrospective evaluation. Before her stillbirth, she received regular antenatal care with a physician and had no reported complications during pregnancy. Including the recent stillbirth, she had had 7 pregnancies, resulting in 6 full-term live births. The surviving 6 children tested negative for MERS-CoV antibodies.

DISCUSSION

We report a second trimester stillbirth in a pregnant subject who had a concurrent acute respiratory illness that met the WHO case definition for probable MERS-CoV infection [3]. Linked to the Jordanian outbreak of MERS-CoV infection, the illness in the pregnant subject began within 14 days following unprotected exposures to 2 individuals with MERS-CoV during their illnesses (her MERS-CoV antibody--positive husband and a real-time RT-PCR–positive relative). She was symptomatic but did not seek medical care because she wished to avoid chest radiography and medications during pregnancy.

With the currently limited knowledge about MERS-CoV epidemiology and pathophysiology, it is prudent to review observed associations between pregnancy outcomes and other severe respiratory pathogens. Complications such as maternal mortality and stillbirth have been reported among pregnant women with severe respiratory infections caused by SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) [4], influenza A virus subtype H1N1 [5, 6], and other viruses causing pneumonia [7]. Uncomplicated pregnancies lead to physiologic changes resulting in altered pulmonary and immunologic function [8, 9], including a 20% increase in maternal oxygen consumption, a 10%–25% decrease in functional residual capacity, and significantly increased forced vital capacity after 14–16 weeks gestation. Severe respiratory illness during pregnancy may further disrupt maternal tolerance to hypoxemia and reduce oxygen flow to the fetus. Of 12 pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV in South China during 1 January–31 July 2003, spontaneous miscarriages were reported from over half (59%) of those infected during their first trimesters [10]. Premature deliveries, thought to be related to poor fetal oxygenation, were experienced among 80% of those women during their second to third trimesters and were associated with intrauterine growth restriction.

Further investigations in other settings of MERS-CoV infection outbreaks may shed light on factors related to the risk of infection and adverse birth outcomes in pregnant women, including any temporal relationship between maternal infection and period of gestation, biomarkers of immune hyperactivity, decreased respiratory function, and evidence of tissue necrosis upon hospitalization, as was observed during the epidemic of SARS-CoV infection to indicate adverse prognoses [11, 12]. Further information regarding the risk of MERS-CoV–associated adverse consequences to mother and fetus during pregnancy, as well as the benefits and risks of possible therapies, is needed to better inform treatment decisions in pregnant women.

Although it is unclear whether cultural sensitivities restricted the full capture of information during our interviews, this was a joint investigation with the CDC and the Jordan Ministry of Health, and the interviewers included females from the region. All interviewers demonstrated an understanding of cultural sensitivities and spoke Arabic. A limitation of our report is that confirmation from seroepidemiologic evidence is difficult with any retrospective investigation, and associations between serologic evidence and a particular outcome can appear spurious. Indeed, the fetal loss rate from nonchromosomal and nonstructural causes at 20 weeks gestation is estimated to be 0.5% (95% confidence interval, .3%–.8%) [13] in developed countries, and other biological explanations for our observations are possible. Nonetheless, no other MERS-CoV infections were confirmed in Jordan around this brief outbreak period despite hundreds of specimens being tested via active surveillance [14]. On the basis of the exclusivity of the timing of the pregnant subject's unprotected MERS-CoV exposure history, concurrent respiratory illness and stillbirth, and positive results of subsequent MERS-CoV serologic tests, we describe a possible association between MERS-CoV infection and stillbirth.

We conclude that adverse maternal and birth outcomes observed during the SARS-CoV epidemic and influenza A(H1N1) pandemic are consistent with the possibility that MERS-CoV infection during pregnancy may pose serious health risks to both mother and fetus. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, where the majority of MERS-CoV cases have occurred, included pregnant women in its 2013 recommendation of groups that should “postpone the performance of Umrah and Hajj [in 2013]” [15]. Neither the CDC nor the WHO has issued evaluation or management strategy recommendations specifically for MERS-CoV infection among pregnant women. As indicated by our investigation, MERS-CoV infections could potentially remain undetected among pregnant women because of barriers to receiving appropriate diagnostic care. Future prospective investigations of MERS-CoV should ascertain pregnancy status, and further pregnancy-related data should be obtained, including results of confirmatory testing of biological specimens.

STUDY GROUP MEMBERS

Members of the Jordan MERS-CoV Investigation Team are as follows: Dr Nabil Sabri, Dr Mohammad Al Azhari, Dr Hala Khazali, Dr Mohammad Al Maayah, Dr Adel Bilbeisi, Dr Naim Dawood, and Dr Bilal Al Zubi (Jordan Ministry of Health); Dr Jawad Meflih (Eastern Mediterranean Public Health Network); Dr Tony Mounts, Dr Julia Fitzner, Dr Akram Eltom, and Dr Ali Mafi (WHO); Congrong Miao, Dr Hayat Caidi, Suvang Trivedi, Dr. Jennifer Harcourt, Dr. Azaibi Tamin, Shifaq Kamili, Dr Aron J. Hall, Aaron Curns, Jessica Moore, Huong Pham, and Dr Chris Zimmerman (National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC); Dr Eileen Farnon, Dr Genessa Giorgi, and Dr Russell Gerber (Center for Global Health, CDC); and Dr David Kuhar (National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC).

Notes

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial support. This work was supported by the US Global Disease Detection Operations Center Outbreak Response Contingency Fund.

This work was supported by the US Global Disease Detection Operations Center Outbreak Response Contingency Fund.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiu068

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://academic.oup.com/jid/article-pdf/209/12/1870/2398165/jiu068.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1093/infdis/jiu068

Article citations

Impact of COVID-19 on Maternal Health Service Uptake and Perinatal Outcomes in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review.

Int J Environ Res Public Health, 21(9):1188, 06 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39338071 | PMCID: PMC11431751

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

The perinatal health challenges of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases: A narrative review.

Front Public Health, 10:1039779, 05 Jan 2023

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 36684933 | PMCID: PMC9850110

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

COVID-19 and Pregnancy: A narrative review of maternal and perinatal outcomes.

Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J, 22(2):167-178, 26 May 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 35673299 | PMCID: PMC9155024

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Stillbirth after COVID-19 in Unvaccinated Mothers Can Result from SARS-CoV-2 Placentitis, Placental Insufficiency, and Hypoxic Ischemic Fetal Demise, Not Direct Fetal Infection: Potential Role of Maternal Vaccination in Pregnancy.

Viruses, 14(3):458, 23 Feb 2022

Cited by: 16 articles | PMID: 35336864 | PMCID: PMC8950737

A Comprehensive Review of the Management of Pregnant Women with COVID-19: Useful Information for Obstetricians.

Infect Drug Resist, 14:3363-3378, 24 Aug 2021

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 34466003 | PMCID: PMC8402981

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (58) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Active screening and surveillance in the United Kingdom for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in returning travellers and pilgrims from the Middle East: a prospective descriptive study for the period 2013-2015.

Int J Infect Dis, 47:10-14, 23 Apr 2016

Cited by: 29 articles | PMID: 27117200 | PMCID: PMC7110479

A family cluster of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus infections related to a likely unrecognized asymptomatic or mild case.

Int J Infect Dis, 17(9):e668-72, 02 Aug 2013

Cited by: 109 articles | PMID: 23916548 | PMCID: PMC7110537

Hospital-associated outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a serologic, epidemiologic, and clinical description.

Clin Infect Dis, 59(9):1225-1233, 14 May 2014

Cited by: 205 articles | PMID: 24829216 | PMCID: PMC4834865

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): challenges in identifying its source and controlling its spread.

Microbes Infect, 15(8-9):625-629, 19 Jun 2013

Cited by: 54 articles | PMID: 23791956 | PMCID: PMC7110483

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Intramural CDC HHS (1)

Grant ID: CC999999