Abstract

Free full text

The confusing tale of depression and distress in patients with diabetes: a call for greater clarity and precision

Abstract

Studies have identified significant linkages between depression and diabetes, with depression associated with poor self-management behaviour, poor clinical outcomes and high rates of mortality. However, findings are not consistent across studies, yielding confusing and contradictory results about these relationships. We suggest that there has been a failure to define and measure ‘depression’ in a consistent manner. Because the diagnosis of depression is symptom-based only, without reference to source or content, the context that diabetes is not considered when addressing the emotional distress experienced by individuals struggling with diabetes. To reduce this confusion, we suggest that an underlying construct of ‘emotional distress’ be considered as a core construct to link diabetes-related distress, subclinical depression, elevated depression symptoms and major depressive disorder. We view emotional distress as a single, continuous dimension that has two primary characteristics: content and severity; that the primary content of emotional distress among these individuals include diabetes and its management, other life stresses and other contributors; and that both the content and severity of distress be addressed directly in clinical care. We suggest further that all patients, even those whose emotional distress rises to the level of major depressive disorder or anxiety disorders, can benefit from consideration of the content of distress to direct care effectively, and we suggest strategies for integrating the emotional side of diabetes into regular diabetes care. This approach can reduce confusion between depression and distress so that appropriate and targeted patient-centred interventions can occur.

Introduction

An extensive literature has developed that explores the linkages between depression, self-care behaviour and glycaemic control among adults with diabetes. The reportedly high prevalence of depression in this population and its association with mortality, emergence of complications, increased hospitalizations and healthcare costs [1–3] have spurred widespread interest in assessment and treatment, and in more fully understanding the mechanisms that underlie these relationships [4].

A careful review of this literature, however, indicates widespread inconsistencies that cause us to question our understanding of the underlying relationship between depression and diabetes. These inconsistencies across studies fall into three general areas: (1) differences in the reported prevalence of depression, (2) in the association between depression and self-management and (3) in the association between depression and glycaemic control.

Regarding prevalence, although meta-analyses have demonstrated high levels of depression among individuals with diabetes [5], Nouwen et al. [6], Golden et al. [7] and Mezuk et al. [8] have shown that depression is elevated only among diagnosed patients and not among those with undiagnosed diabetes or impaired fasting glucose. Furthermore, both Pan et al. [9] and Li et al. [10] have shown that depression symptoms are highest among those treated with insulin, compared with those not on medications or on oral medications, and Pouwer et al. [11] have shown that depression is much more prevalent among those with co-morbid diseases and complications compared with those without. These studies suggest that the prevalence of depression among those with diabetes is not uniform: it is limited to those who have been formally diagnosed, and it is significantly higher among those with poorer health and those who have been prescribed more aggressive treatments, thus reflecting the burden of treatment, advancing disease or both.

In a meta-analytic review, Gonzalez et al. [12] reported that symptoms of depression are consistently associated with poorer diabetes self-management. However, the only study included in this review that used a gold-standard structured clinical interview to diagnose major depressive disorder (MDD) found no significant relationship between major depressive disorder and self-management [13]. Other studies have shown that the effect of depressive symptoms on poor self-management can be observed even if probable cases of major depressive disorder are excluded from analysis [14,15], calling into question the role of co-morbid major depressive disorder in explaining these relationships.

Finally, initial studies demonstrated that symptoms of depression are significantly related to poor glycaemic control among individuals with diabetes [16]. However, subsequent studies have failed to confirm earlier findings [17–19]. Moreover, interventions that successfully reduce depression among those with diabetes indicate no consistent corresponding improvement in glycaemic control or self-management [20,21]. How might we explain these inconsistent findings? We suggest that there has been a failure to appreciate the context that diabetes provides for understanding the source, reported content and severity of the ‘depression’ experienced by many patients struggling with this disease. In this report we discuss how consideration of the emotional burden of self-management, threats of complications and potential loss of functioning—called ‘diabetes distress’—may resolve some of this confusion and enhance our understanding of the potential mechanisms of their interaction. This discussion leads us to identify problems with the definition and measurement of both depression and diabetes distress and to observe areas of potential overlap. Throughout, we review implications for intervention.

Differences between definitions of depression and distress in diabetes

Major depressive disorder, the primary affective disorder in the diabetes literature, and diabetes distress have evolved from very different histories and theoretical perspectives, they have different definitions and they have very different implications for understanding aetiology and treatment [22,23]. Yet the terms have often been used without fully grasping how they reflect the very different conceptualizations of the phenomena they describe. We contrast these differences below.

Major depressive disorder

Major depressive disorder is a psychiatric disorder that emerges from a tradition of research in clinical diagnosis and psychopathology. Major depressive disorder, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-V), with linkages to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10), requires the presence of at least five of nine well-defined diverse symptoms that persist over at least 2 weeks. Symptoms must also cause significant emotional distress and/or impairment in functioning (Table 1). This operational definition of major depressive disorder raises two major problems. First, and perhaps most importantly, major depressive disorder is arguably among the very few diagnoses in the medical nomenclature that is not defined by aetiology: the diagnostic criteria are exclusively symptom-based, they do not specify a cause or a disease process, and they do not direct a choice among treatments [24]. Major depressive disorder is not content-related in so far that it does not describe pathology based on relevant causes, perturbations or contextual stressors [25]. Thus, major depressive disorder does not distinguish between what may be an expected reaction to a significant life stressor, such as reacting to a new diabetes complication, and what is pathological in any systematic or empirically supported way [26]. This is particularly problematic when considering that emotional distress is a non-specific indicator of most psychological problems [4] and there is a risk of considering something pathological when it could easily be an expected reaction to a challenging life problem, as in diabetes [22,26]. Second, major depressive disorder does not distinguish among the considerable heterogeneity of symptoms that can be experienced by patients who receive the same diagnosis [27]. This has led to an improved reliability of diagnosis, but at the expense of validity [28].

Table 1

A comparison among frequently used measures of depression*

| Symptoms | DSM-V | PHQ-9 | CES-D | HADS-D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressed mood |

|

|

| |

| Anhedonia |

|

|

| |

| Appetite |

|

|

| |

| Sleep |

|

|

| |

| Psychomotor changes |

|

|

| |

| Fatigue |

|

|

| |

| Guilt or worthlessness |

|

|

| |

| Impaired thinking, concentration or decision making |

|

|

| |

| Suicidality |

|

| ||

| Miscellaneous |

| |||

| Additional requirements |

| Item 10 inquires about functional impairment but is rarely used. | None | None |

| Time frame | Symptoms must be present during the same 2-week period | Prior 2 weeks | Past week | Past week |

| Response scale | N/A |

|

| Various indicators of frequency, with no reference to number of days. Some refer to prior states, others do not |

| Scoring | Must include either symptom 1 or 2, a total of five or more symptoms, and represent a change from previous functioning | Positive ≥ 10 | Positive ≥ 16 or ≥ 21 | Positive ≥ 8 |

N/A, xxxxxxxxx.

Diabetes distress

Diabetes distress refers to a far broader affective experience than major depressive disorder. It captures the worries, concerns and fears among individuals struggling with a progressive and demanding chronic disease such as diabetes [18]. Diabetes distress emerges from two very different theoretical traditions than major depressive disorder: research on stress and coping and research on emotional regulation in response to specific acute or chronic stressors. In both of these areas, emotions are understood as emerging from specific situational contexts. Specifically, emotional distress is an expected response to patient perceptions of health threats balanced against an appraisal of available coping resources. Diabetes distress is not therefore a proxy for clinical depression [29]; instead, diabetes distress reflects an emotional response to a demanding health-related condition.

Diabetes distress stands in contradistinction to major depressive disorder in four important ways. First, unlike major depressive disorder, diabetes distress implies aetiology. Rather than focusing on the presence or absence of specific symptoms irrespective of cause as in major depressive disorder, it includes a broad range of emotional experiences and is defined by the context of diabetes and its management. Second, whereas in major depressive disorder efforts have been placed on assessing and classifying patient symptoms, in diabetes distress, because it is content-related, emphasis focuses on distinguishing among the different sources of distress so that specific interventions can be initiated. Third, unlike major depressive disorder, diabetes distress does not assume psychopathology nor is diabetes distress necessarily considered a co-morbid psychiatric disorder. Because diabetes distress is linked to specific stressors, and because much of diabetes distress is an expected reaction to a serious and chronic health-related stressor, it is viewed as part of the spectrum of diabetes, not as a separate clinical condition indicating psychopathology [22,23,30]. Last, unlike major depressive disorder, because it is content-related, specific interventions can be easily linked to the source of diabetes distress.

Differences in the measurement of depression and distress in diabetes

Depression has been measured in a variety of ways in the diabetes literature. These include structured clinical interviews linked to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria for major depressive disorder, considered the gold standard for diagnosis [31]; diagnoses recorded in large-scale clinical databases without further validation; self-report screening scales based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) [32]; self-report depression symptom scales unrelated to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria; for example, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), [33] and single survey items in which patients are asked to indicate if they were ever told that they ‘had’ depression. Each of these approaches to measurement yields different rates of prevalence and incidence, and each demonstrates different levels of association with diabetes management and with glycaemic control [34] (Table 1).

The substantive differences among these approaches to the measurement of major depressive disorder and the high rate of false-positive cases resulting from screening are under appreciated in the diabetes literature. For example, one study from the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial [35] showed that more than half of those with positive PHQ-9 depression screens did not reach the requisite symptoms for a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. A recent review of self-report measures of depression for adults with diabetes underscores the problem further: 44–77% of positive screens for major depressive disorder in adults with diabetes were likely false positives [36]. In addition, most of the scales used in these studies contained items that reflect common symptoms of hyperglycaemia and many patients report endorsing symptoms of depression on these scales based on their stressful experience with diabetes, both of which lead to spuriously high prevalence rates of clinical depression [37,38]. Hence, the high rate of false positives inaccurately represents as a disease the distress experienced by many individuals as they struggle with the burdens of diabetes and its management. This adds to imprecision and confusion in the research literature and delays progress toward the development of appropriate approaches to treatment.

Because diabetes distress is context-specific, its measurement is relatively more uniform and straightforward; for example, Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) [39], Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS) [40]. Many standardized measures of diabetes distress, however, lack comprehensiveness in the assessment of sources of diabetes distress; for example, distress attributable to starting insulin, the emergence of a new complication, or the accumulated demands and burdens of self-care. These problems narrow our understanding of the clinical picture and limit our ability to select patient-centred interventions that have the greatest likelihood of being effective.

Nevertheless, the importance of diabetes distress as a missing consideration in the depression and diabetes literature becomes apparent when measures of major depressive disorder, depressive symptoms and diabetes distress are included in the same study. For example, the 3D Study was an 18-month, three-wave longitudinal observational study of 502 adults with Type 2 diabetes that included a structured Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-based psychiatric interview measure of major depressive disorder, a self-report measure of depressive symptoms (CES-D) and a self-report measure of diabetes distress (DDS), and measures of behavioural management and glycaemic control. Results indicated that diabetes distress displayed significantly greater prevalence and incidence than major depressive disorder [13,41] and that diabetes distress, and not major depressive disorder, displayed significant cross-sectional and longitudinal associations with glycaemic control, diet and non-HDL cholesterol [13,18]. Furthermore, associations between depressive symptom scores and diet, physical activity and glycaemic control were no longer significant when diabetes distress scores were added to the equations [13], suggesting that the elevated, exclusively symptom-based depressive symptom scores were most likely assessing the affective component of content-specific diabetes distress.

The 3D Study also showed that 84.1% of patients with moderate or high diabetes distress did not reach criteria for a diagnosis of major depressive disorder; and that 66.7% of patients who reached criteria for major depressive disorder also reported moderate or high diabetes distress. These findings suggest that over 80% of patients with Type 2 diabetes and high diabetes distress are not clinically depressed and that, among those who are clinically depressed, many of the depressive symptoms reported are related to diabetes [37]. The 3D Study also showed that only approximately one third of patients with diabetes who met criteria for major depressive disorder reported symptoms unrelated to their diabetes.

Where do we go from here?

The problems concerning the definition and measurement of major depressive disorder among patients with diabetes have caused considerable confusion in the literature. We argue that divorcing the symptoms of major depressive disorder from the context that explains them often leads to mistaking diabetes-related emotional distress for a psychiatric condition that can lead to inappropriate treatment.

We propose the following as a vehicle for addressing these problems in clinical care with patients with diabetes. First, we suggest that emotional distress be considered a common core construct that underlies diabetes distress, depressive symptoms, ‘subclinical depression’ and major depressive disorder. Second, given the significant incremental relationships between measures of depressive symptoms and measures of self-management [14,18], diabetes complications and mortality risk [1,42], emotional distress is best considered a continuous, scalable psychological characteristic rather than a discrete co-morbid clinical condition.

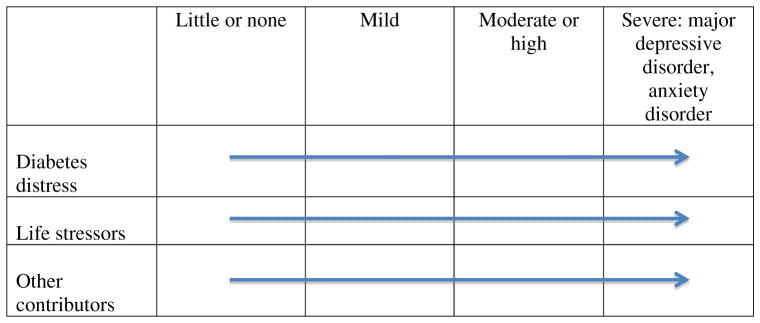

Third, we suggest that emotional distress can be caused by one or more of three inter-related stressors in this patient population (Fig. 1): distress resulting from diabetes and its management (e.g. fears of complications, diabetes burnout), distress resulting from life stressors unrelated to diabetes (e.g. family, work, financial) and distress resulting from other causes (e.g. personal characteristics, life history, genetics). As reviewed above, much of the distress experienced by individuals with diabetes is related to diabetes and its management. When discussing distress in this population, however, we urge a focus on both diabetes- and non-diabetes-related stressors, because other life problems and life history factors often exacerbate diabetes-related difficulties. This wider socio-ecological framework for observing the content of distress creates a logical explanatory model that acknowledges the interconnectedness of stressors in ways that enhance clinical decision making regarding intervention [4]. Furthermore, approximately one third of patients with diabetes who reach criteria for major depressive disorder do not display high diabetes distress [41], suggesting that diabetes may not be a central focus of their severe depressive symptoms. These may be chronically or acutely distressed patients who also may happen to have diabetes. Thus, identifying the content of the emotional distress helps focus intervention.

Considering these three propositions, we suggest that the effective management of emotional distress among people with diabetes requires a thorough assessment of two independent characteristics of emotional distress: the content of the life context factors that may explain the distress and the severity of the distress—balanced against the patient’s perceived resources to deal with the distress. As has been outlined, a focus on major depressive disorder alone, a symptom-based diagnosis that emphasizes severity, tells only a part of the story, because it does not incorporate content or cause. Likewise, a focus on diabetes distress alone, a primarily content-based construct, does not address severity directly. By addressing both content and severity within a single evaluative process, as illustrated in Fig. 1, issues that confuse the definitions of diabetes distress and major depressive disorder are reduced because severity and cause are deemed distinct and assessed separately; their potential for overlap is eliminated because they refer to different characteristics of the observed phenomenon; and directions for care are enhanced because both content and severity are necessary for an appropriate clinical intervention. For example, a person who reaches a level of severity of emotional whether from diabetes, life stressors or other contributors, that meets Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria for major depressive disorder (or anxiety disorders) should be treated following guidelines, regardless of cause. This reflects the severity characteristic of emotional distress. The treatment, however, should also target the source of the distress, such as assistance with diabetes management, a referral for marriage counselling, or a referral for skill-building because of lifelong problems managing relationships. This reflects the content of emotional distress. Other interventions with relevance to both content and severity can occur across the continuum of emotional distress, but both need to be assessed to inform the type and intensity of intervention.

Implications for care

As reviewed above, diabetes distress is part of the experience of diabetes for many patients over time; for example, 48% in the 3D Study met criteria for high distress over 18 months [41]. Furthermore, even at low levels, diabetes distress is significantly related to glycaemic control and behavioural management [18]. Consequently, we propose that attention to emotional distress be included as part of ongoing comprehensive care for all patients with diabetes and not addressed as a separate co-morbid ‘condition’ that is diagnosed and treated only when detected. Furthermore, there is no clear evidence to suggest that interventions that target improved self-management or diabetes education also reduce distress [43], suggesting that targeting distress directly, especially when distress is high, may yield the best outcomes [44].

We suggest three levels for grouping distress-related interventions in clinical care [22]. First, all patients with diabetes, even those with little or no current distress, can profit from the ongoing acknowledgement, education and support that considers distress an expected part of diabetes [4,45]. The high costs of intervention to reduce emotional distress and affective disorders, and the malleability of diabetes distress, especially when levels are low or moderate, argue for the early incorporation of diabetes distress into clinical care, especially at critical moments during the course of the disease; for example, starting insulin, emergence of complications. Findings from the Research Design and Methods (REDEEM) distress-reduction trial showed that even minimal, inexpensive interventions can lower levels of distress and improve disease management [44]. Approaches can include anticipating and acknowledging diabetes stressors over time, normalizing the experience of diabetes-related distress as part of the spectrum of diabetes, and recognizing how other life stressors can affect diabetes management. These can take place as part of traditional diabetes education or they can be addressed as part of a standard clinical encounter, a low-cost strategy that simply integrates the emotional and behavioural sides of diabetes.

If distress increases over time or is exacerbated in reaction to a specific diabetes-related or non-diabetes-related event, more focused interventions, such as structured problem solving or family interventions, may be helpful. Addressing moderate distress directly makes use of ongoing clinical relationships with staff that are the hallmark of good diabetes care [4].

At higher levels of emotional distress, more aggressive interventions may be warranted, including medications and psychotherapy. However, even for these individuals, treatment of their emotional distress may benefit from a consideration of diabetes context [46]. This approach emphasizes integrative, multidisciplinary care that combines the expertise of diabetes and mental health specialists with primary care providers to provide coordinated, comprehensive care [47,48].

Strengths and limitations

This approach to making sense of a confusing and inconsistent body of literature has several strengths. First, it anchors the high prevalence of emotional distress in the real world by placing symptoms in context and addressing those crucial patient beliefs, expectations and resources that form the foundation of distress management. Doing so frames the distress by what is causing it and how it is being responded to; helps decide if the distress needs extra clinical attention and, if so, what kind; links the content and severity of distress to treatment; and reduces the need to call an emotional experience pathological when what we observe is most often an integral part of a major chronic life stressor—diabetes. Second, it uses a single dimension to define the experience—emotional distress. By doing so, it eliminates the confusion caused by the application of different terms as if they refer to different so-called ‘conditions’ or ‘disorders.’ It also helps distinguish between these two very different but overlapping views of affective phenomena (diabetes distress, depression) without disqualifying either. Third, as emotional distress is a non-specific indicator of almost all psychological problems and as even low levels of diabetes distress are related to glycaemic control and disease management, in the real world of clinical care a single continuous dimension of severity that attends to the patient’s life context—including their experience with chronic disease, general life stress and other life factors—can more easily lead to practical, clinically sensible decision making.

These suggestions raise several challenges, however. First, they require integrating the emotional, behavioural and physiological aspects of diabetes throughout routine diabetes care and education. Second, they expand the range of intervention options to address diabetes-related life stressors that may impact diabetes management; for example, family and community involvement. Third, issues of professional training and comfort in dealing with emotional issues need to be addressed so that the emotional experience of diabetes can be incorporated into each component of the care process seamlessly. Despite these difficulties, we must move beyond the tendency to place an artificial divide between the emotional and the physical aspects of diabetes management that can lead to labelling the emotional aspects of diabetes a pathological condition. The two are so intertwined and interrelated that simply calling the emotional side a co-morbidity is counterproductive.

Conclusions

A lack of precision and clarity in definition and measurement has led to a literature on depression and diabetes that is confusing and often contradictory. To resolve this confusion, we suggest that the construct of emotional distress be considered as a core, continuous dimension that underlies diabetes-related distress, ‘subclinical’ depression, elevated depressive symptoms and major depressive disorder; that the primary source or content of emotional distress include diabetes and its management, other life stresses and other contributors; and that both the source and severity of distress be considered in clinical care. We suggest that all people with diabetes, even those whose diabetes-related emotional distress rises to the level of major depressive disorder, can benefit from consideration of the content of their emotional distress to direct care effectively. This approach can lead to more appropriate and targeted patient-centred interventions.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources

This article was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants DK061937 and DK094863.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12428

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc4065190?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1111/dme.12428

Article citations

Antidepressant prescribing inequalities in people with comorbid depression and type 2 diabetes: A UK primary care electronic health record study.

PLoS One, 19(11):e0309153, 05 Nov 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39499713 | PMCID: PMC11537397

The moderating role of diabetes distress on the effect of a randomized eHealth intervention on glycemic control in Black adolescents with type 1 diabetes.

J Pediatr Psychol, 49(8):538-546, 01 Aug 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38775162

Social support as perceived, provided and needed by family-members of migrants with type 2 diabetes - a qualitative study.

BMC Public Health, 24(1):1612, 17 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38886671 | PMCID: PMC11181519

Role of Psychosomatic Medicine in Complex Medical Cases: A Case Study of a Patient With Breast Cancer Who Refused Mastectomy.

Cureus, 16(5):e61343, 30 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38947634

Association between solar radiation and mood disorders among Gulf Coast residents.

J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol, 03 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38831020

Go to all (199) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Addressing diabetes distress in clinical care: a practical guide.

Diabet Med, 36(7):803-812, 07 May 2019

Cited by: 73 articles | PMID: 30985025

Review

Exploring the relationship between cognitive illness representations and poor emotional health and their combined association with diabetes self-care. A systematic review with meta-analysis.

J Psychosom Res, 76(4):265-274, 21 Feb 2014

Cited by: 34 articles | PMID: 24630175

Review

Differentiating symptoms of depression from diabetes-specific distress: relationships with self-care in type 2 diabetes.

Diabetologia, 51(10):1822-1825, 09 Aug 2008

Cited by: 63 articles | PMID: 18690422 | PMCID: PMC2678064

Telephone interventions for symptom management in adults with cancer.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 6:CD007568, 02 Jun 2020

Cited by: 39 articles | PMID: 32483832 | PMCID: PMC7264015

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIDDK NIH HHS (6)

Grant ID: DK061937

Grant ID: DK020541

Grant ID: DK094863

Grant ID: R01 DK061937

Grant ID: R01 DK094863

Grant ID: DK098742

National Institutes of Health (1)

Grant ID: DK094863