Abstract

Free full text

Direct evidence for BBSome-associated intraflagellar transport reveals distinct properties of native mammalian cilia

Abstract

Cilia dysfunction underlies a class of human diseases with variable penetrance in different organ systems. Across eukaryotes, intraflagellar transport (IFT) facilitates cilia biogenesis and cargo trafficking, but our understanding of mammalian IFT is insufficient. Here we perform live analysis of cilia ultrastructure, composition and cargo transport in native mammalian tissue using olfactory sensory neurons. Proximal and distal axonemes of these neurons show no bias towards IFT kinesin-2 choice, and Kif17 homodimer is dispensable for distal segment IFT. We identify Bardet–Biedl syndrome proteins (BBSome) as bona fide constituents of IFT in olfactory sensory neurons, and show that they exist in 1:1 stoichiometry with IFT particles. Conversely, subpopulations of peripheral membrane proteins, as well as transmembrane olfactory signalling pathway components, are capable of IFT but with significantly less frequency and/or duration. Our results yield a model for IFT and cargo trafficking in native mammalian cilia and may explain the penetrance of specific ciliopathy phenotypes in olfactory neurons.

The cilium is a sensory organelle that serves specialized roles on diverse cell types throughout eukaryotes. Disruption of cilia in vertebrates gives rise to developmental patterning defects, progressive degenerative disorders and sensory deficits. Penetrance of congenic human ciliopathy disease phenotypes varies among different tissues and can be influenced by the gene that is disrupted, the nature of mutation and the genetic background of the individual1. The precise mechanisms of this variable penetrance are unclear, in particular when mutations affect ubiquitously expressed cilia genes. Across eukaryotes, cilia and flagella are built and maintained by intraflagellar transport (IFT), a process in which macromolecular protein ‘trains’ comprising IFT-A and IFT-B subcomplexes bidirectionally traverse the ciliary microtubule axoneme via association with kinesin and dynein motors2. Mutations in several human IFT genes are linked to a group of gestational skeletal disorders3,4,5,6 and, recently, one gene encoding a core IFT complex B protein was revealed as a disease locus for Bardet–Biedl syndrome (BBS)7. BBS is a heterogeneous pleiotropic ciliopathy that shows penetrance in a number of organs and clinically manifests in obesity, polydactyly, renal cyst formation, retinal cell death, male infertility and anosmia. Of note, only these latter two conditions are due to the absence of cilia structures8,9,10 and it is unclear why cilia in one cell type or tissue are lost but persist (or degenerate slowly) in other organs.

Work in lower eukaryotes, namely in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Caenorhabditis elegans, has demonstrated functional links between the IFT machinery and BBSome in cilia formation and maintenance and, moreover, currently accounts for the majority of our knowledge concerning IFT dynamics11,12. In mammals, IFT has been described in only a small number of studies on cultured cells13,14,15,16,17,18 and the fundamental questions of how the mammalian IFT machinery operates in native cilia or whether it associates with BBS proteins have not been addressed. These questions are particularly relevant in the context of IFT gene mutations causing BBS7 and BBS disease penetrance within the olfactory system where BBS protein disruption is detrimental to ciliation and odour detection9,10. Importantly, these unanswered questions can have significant implications for therapeutic strategies to treat ciliopathies in different organ systems.

IFT studies in vertebrates present a challenge, because most cilia of vertebrate tissues are inaccessible in the live animal. In contrast, olfactory cilia are uniquely amenable to live analysis due to their direct contact with the external environment via the nasal passage. This enables manipulation of live olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) without disrupting synaptic connections. Here we exploited adenovirus (AV)-mediated protein expression and live-cell time-lapse imaging to capture IFT and cargo-trafficking events within native mammalian olfactory cilia. We find that the IFT machinery in OSN cilia employs two kinesin motors (heterotrimeric kinesin-2 and homodimeric Kif17), but Kif17 is not required for IFT or OSN cilia maintenance. OSN IFT particle velocities vary stochastically among neurons, but velocities in different cilia of individual neurons are similar to one another. We reveal constituents of the core BBS protein complex as participants in OSN IFT that exist in 1:1 stoichiometry with IFT particles. In addition, peripheral membrane Arl proteins and polytopic transmembrane signalling proteins traffic with IFT in OSN cilia, but the transmembrane proteins do so much less frequency and/or duration. Overall, our findings provide framework for the first model of IFT in a native mammalian setting and implicate the relationship between IFT and the BBSome as a likely culprit in the penetrance of BBS mutations on ciliation in the olfactory epithelium (OE).

Results

Distinct properties of the OSN ciliary axoneme and membrane

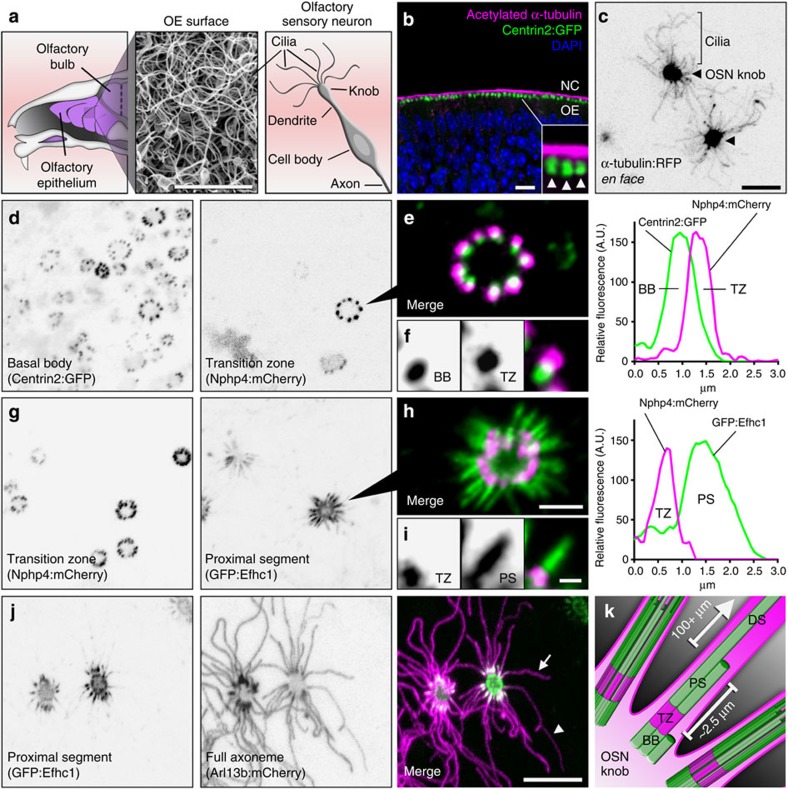

To properly dissect ciliary trafficking dynamics in native mammalian olfactory cilia, we first delineated the organization of OSN cilia architecture via molecular profiling in living mouse tissue. In addition to allowing measurement of cilia dynamics, live analysis of ultrastructural features enables accurate appraisal of cilia properties that can be lost with fixation. We used AV-mediated ectopic expression of fluorescent protein (FP)-tagged proteins that comprise various structural elements of the OSN cilium (Fig. 1). En face microscopic investigation of red FP-tagged α-tubulin revealed the microtubule backbones of the many cilia emanating from the dendritic knob of each AV-transduced OSN (Fig. 1c). OSN ciliary basal bodies and transition zones were identified using transgenic Centrin2:GFP mice ectopically expressing Nphp4:mCherry (Fig. 1d–f). Based on Nphp4:mCherry fluorescence, OSN ciliary transition zones measure 0.95±0.12 μm in length (n=72 cilia, 9 OSNs, 3 mice), similar to frog and nematode19,20. To visualize OSN axoneme microtubule organization, we used green FP (GFP)-tagged EF-hand domain containing 1 (GFP:Efhc1), which associates with interdoublet links connecting doublet microtubules21 and is highly enriched in OSNs22. GFP:Efhc1 was restricted specifically within the proximal-most region of OSN cilia, revealing the OSN doublet–singlet microtubule transition at 2.34±0.42

μm in length (n=72 cilia, 9 OSNs, 3 mice), similar to frog and nematode19,20. To visualize OSN axoneme microtubule organization, we used green FP (GFP)-tagged EF-hand domain containing 1 (GFP:Efhc1), which associates with interdoublet links connecting doublet microtubules21 and is highly enriched in OSNs22. GFP:Efhc1 was restricted specifically within the proximal-most region of OSN cilia, revealing the OSN doublet–singlet microtubule transition at 2.34±0.42 μm from the base of the transition zone (Fig. 1g–i, n=141 cilia, 11 OSNs, 3 mice). Finally, to differentiate the proximal versus distal segments of OSN cilia23, we co-expressed GFP:Efhc1 with mCherry-tagged ADP-ribosylation factor-like 13b (Arl13b:mCherry), which localizes along the full length of OSN cilia6 (Fig. 1j). Collectively, our data showing highly restricted localization patterns of FPs with strong correlation to previous electron microscopy data in rodent23 demonstrate that ectopic expression accurately delineates endogenous protein localization in cilia of live OSNs.

μm from the base of the transition zone (Fig. 1g–i, n=141 cilia, 11 OSNs, 3 mice). Finally, to differentiate the proximal versus distal segments of OSN cilia23, we co-expressed GFP:Efhc1 with mCherry-tagged ADP-ribosylation factor-like 13b (Arl13b:mCherry), which localizes along the full length of OSN cilia6 (Fig. 1j). Collectively, our data showing highly restricted localization patterns of FPs with strong correlation to previous electron microscopy data in rodent23 demonstrate that ectopic expression accurately delineates endogenous protein localization in cilia of live OSNs.

(a) (Left) Illustration depicting a sagittal view of the mouse OE. (Middle) Scanning electron micrograph of the OE surface showing a dense mat of olfactory cilia. (Right) Illustration depicting multiple cilia on an OSN. (b) Representative confocal image of a coronal OE section from a Centrin2:GFP transgenic mouse stained for acetylated α-tubulin to reveal cilia. NC, nasal cavity. (Arrowheads) Side-by-side dendritic knobs revealed by Centrin2:GFP signal. (c–j) Representative live en face confocal images of AV-transduced native OE expressing various cilia domain-specific marker proteins. (c) AV-α-tubulin:RFP expression reveals many individual OSN microtubule axonemes projecting from two OSN dendritic knobs (arrowheads) on the surface of the OE. (d) Centrin-2:GFP transgenic mouse transduced with AV-Nphp4:mCherry. From left: Centrin-2:GFP-labelled basal bodies (BBs) line the periphery of OSN knobs. Nphp-4:mCherry marks ciliary transition zones (TZ), distally associated with each BB as seen in e. (f) A single TZ/BB unit. Far right: representative line-scan intensity plot showing the fluorescence profile of a single BB/TZ. (g) Co-expression of AV-Nphp-4:mCherry and doublet microtubule marker AV-GFP:Efhc1. GFP:Efhc1 is restricted to the proximal segment (PS) of each OSN ciliary axoneme. (i) A single TZ/PS unit. Far right: representative line-scan intensity plot showing the fluorescence profile of a single TZ/PS. (j) Co-expression of AV-GFP:Efhc1 and cilia peripheral membrane marker AV-Arl13b:mCherry. Arl13b:mCherry reveals axonemes of variable length (compare arrow and arrowhead), each extending from proximal segments marked by GFP:Efhc1. (k) Illustration depicting the ultrastructure of an OSN cilium in which a basal body gives rise to a transition zone followed by a ~2.5 μm doublet microtubule proximal segment and finally a singlet microtubule distal segment (DS) of variable length, sometimes exceeding 100

μm doublet microtubule proximal segment and finally a singlet microtubule distal segment (DS) of variable length, sometimes exceeding 100 μm. Scale bars, 5

μm. Scale bars, 5 μm (a); 10

μm (a); 10 μm (b–d,g,j); 2.5

μm (b–d,g,j); 2.5 μm (e,h); 1.25

μm (e,h); 1.25 μm (f,i).

μm (f,i).

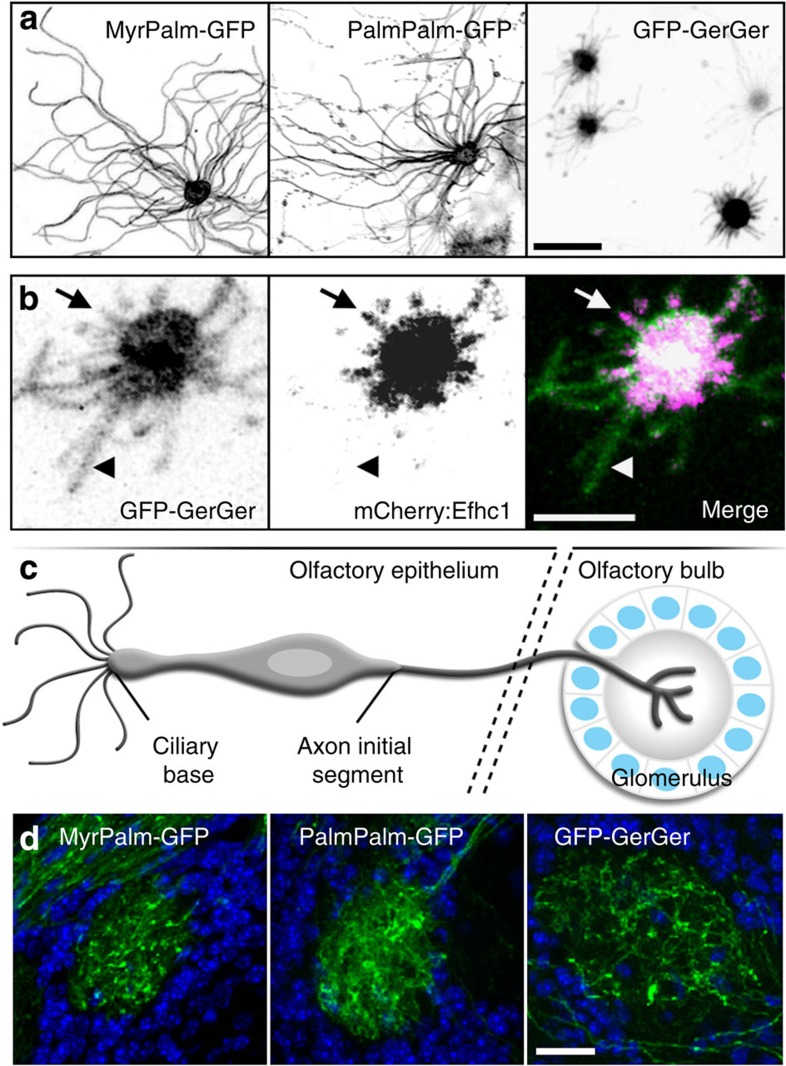

Specific lipid modifications are sufficient to sequester proteins in membrane microdomains of unique lipid composition or organization24. This is particularly relevant to ciliary membrane organization, given that loss of lipid modifications is detrimental to ciliary localization of Arl13b30, Retinitis Pigmentosa 2 (refs 25, 26), cystin27 and fibrocystin28. We compared the ability of myristoylation and palmitoylation (MyrPalm), dual palmitoylation (PalmPalm) and geranylgeranyl (GerGer) signals (which differentially partition into detergent-resistant membrane domains (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b, see Supplementary Methods)), to enrich GFP within the OSN ciliary membrane. MyrPalm-GFP and PalmPalm-GFP were present along the length of olfactory cilia (Fig. 2a); however, GFP-GerGer was constrained within the OSN ciliary proximal region (Fig. 2a). GFP-GerGer localization extended beyond mCherry:Efhc1 (Fig. 2b), indicating that the GerGer membrane microdomain is distinct from and more extensive than the membrane surrounding the OSN cilium proximal segment proper. In contrast to the differential lipid partitioning observed in OSN cilia, we found that OSN axons are equally permissive to each of the three lipid modifications as seen via GFP infiltration of olfactory bulbs (Fig. 2d). Although the axon initial segment29 and ciliary base30,31,32,33,34,35,36 both act as a filter for specific transmembrane or membrane-associated proteins, our data show both are permissive to the lateral enrichment of lipid modified proteins. However, beyond the ciliary base, there exists a differential partitioning of lipid anchors between the OSN proximal and distal segments.

(a) Representative confocal en face images captured from whole OE transduced with AV- (left) MyrPalm-GFP, (middle) PalmPalm-GFP or (right) GFP-GerGer. Whereas MyrPalm and PalmPalm are present throughout OSN ciliary membranes, GerGer is restricted to within the proximal regions of cilia near the OSN knobs. (b) GerGer-GFP ciliary membrane localization can extend beyond the proximal doublet microtubule segments as revealed by AV-mCherry:Efhc1 expression. Arrows highlight a cilium where GFP-GerGer localization is coincident with mCherry:Efhc1. Arrowheads point to a ciliary segment where GFP-GerGer localizes beyond mCherry:Efhc1. (c) Illustration of an OSN depicting the location of the axon initial segment and of synaptic termini in a glomerulus of the olfactory bulb. (d) Lipid-anchored GFPs freely access OSN axons. Representative confocal images of fixed sections through glomeruli of the olfactory bulb from mice expressing (left) MyrPalm-GFP, (middle) PalmPalm-GFP and (right) GFP-GerGer are shown. Empty circular regions surrounded by DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; blue)-labelled nuclei represent glomeruli where OSN axons terminate. Scale bars, 10 μm (a); 5

μm (a); 5 μm (b); 20

μm (b); 20 μm (d).

μm (d).

Finally, to measure OSN cilia number and length, we used MyrPalm-GFP as an inert marker. OSNs possessed 13±5 cilia (n=81 OSNs, 3 mice) with lengths ranging from 2.5 to 110 μm (22.0±12.8

μm (22.0±12.8 μm average, n=1,083 cilia, 3 mice; Supplementary Fig. 2a). We saw no correlation between the number and length of cilia on a given cell (Supplementary Fig. 2b; Pearson’s coefficient R2=0.04829) and cilia lengths were highly variable within cells, indicating that OSN cilia length varies stochastically.

μm average, n=1,083 cilia, 3 mice; Supplementary Fig. 2a). We saw no correlation between the number and length of cilia on a given cell (Supplementary Fig. 2b; Pearson’s coefficient R2=0.04829) and cilia lengths were highly variable within cells, indicating that OSN cilia length varies stochastically.

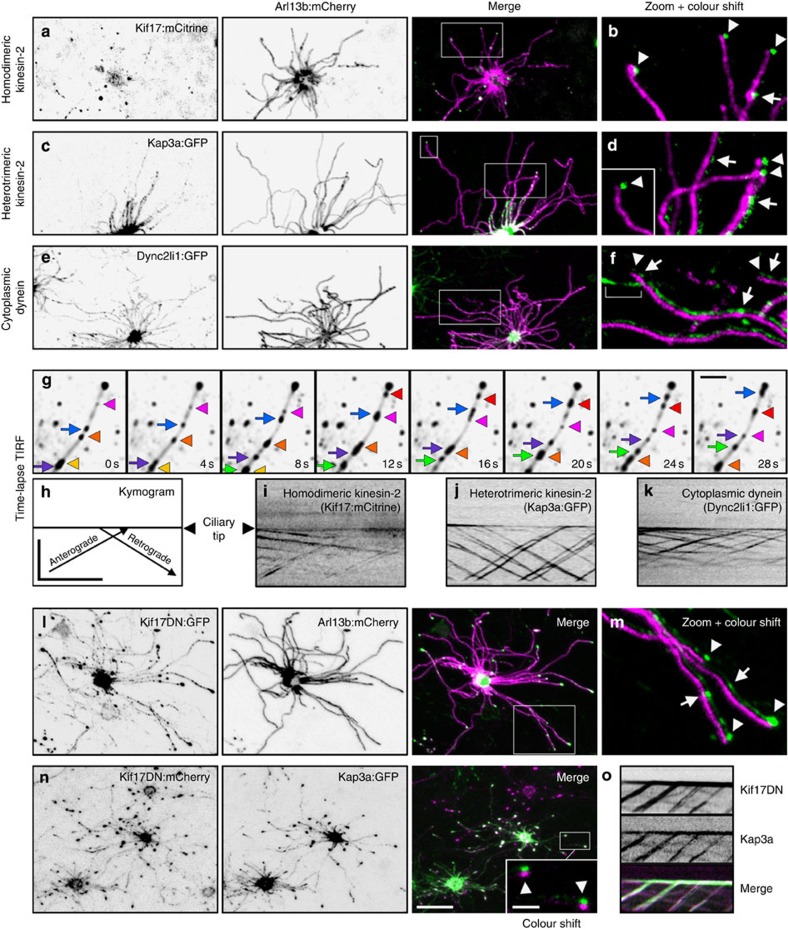

Multiple kinesin-2 subtypes traverse entire OSN axonemes

Our data highlight structural and membrane compositional aspects distinguishing specific subdomains of OSN cilia, but the mechanisms by which the proximal and distal segments are established remain unclear. In C. elegans amphid/phasmid channel sensory cilia, two kinesin motors function in coordination to build the proximal/middle and distal ciliary axoneme segments37. To examine whether multiple kinesin motors are used in OSN cilia, we expressed FP-tagged homodimeric Kif17 and a component of the heterotrimeric kinesin-2 (Kap3a). Both Kap3a and Kif17 localized in puncta along the full length of OSN axonemes and showed accumulations at ciliary tips (Fig. 3a–d). Thus, heterotrimeric kinesin-2 is not restricted to the proximal segment of OSN cilia as seen in nematode amphid/phasmid channel cilia. FP-tagged Dync2li1, a component of the ciliary retrograde dynein motor complex, showed similar localization (Fig. 3e,f). To assess ciliary movement of the motor complex proteins, we employed high contrast, rapid acquisition, total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFm) on OSNs expressing Kap3a:GFP, Kif17:mCitrine or Dync2li1:GFP. Strikingly, each protein showed robust, processive particle movement in both the anterograde and retrograde directions along the entire OSN cilia (Fig. 3g–k and Supplementary Movie 1). To our knowledge, this is the first capture of IFT in any native tissue of a vertebrate and/or mammalian system.

(a–c) Representative live en face confocal images of native OE ectopically expressing components of the IFT motor complexes. (a) Homodimeric kinesin-2 protein Kif17:mCitrine is present in cilia and at ciliary distal tips. (b) Accumulations of Kif17:mCitrine at distal tips (arrowheads) and in puncta along axonemes (arrow). (c) Heterotrimeric kinesin-2 component Kap3a:GFP is abundant along cilia axonemes. (d) Accumulations of Kap3a:GFP at ciliary distal tips (arrowheads) and distribution along axonemes (arrows). (e) Cytoplasmic dynein component Dync2li1:GFP is detectable along cilia axonemes. (f) Dync2li1:GFP is highly abundant along OSN cilia, detectable as discrete puncta (arrows), and is present at ciliary distal tips (arrowheads). Bracket indicates signal in a cilium from an OSN expressing only AV-Dync2li1:GFP. (g) TIRFm time-lapse capture of Kap3a:GFP particle movement in an OSN cilium. Exposures from different time points were overlayed onto an average intensity projection of the entire series to resolve individual particles in relation to the axoneme (ciliary tip is to the right, top). (Arrows) Anterograde particles. (Arrowheads) Retrograde particles. (h–k) Line-scan kymograms generated from single cilia of OSNs ectopically expressing the indicated motor component. (h) Orientation of particle movement in relation to the ciliary tip. Axes represent distance (μm) over time (s). (i) Kif17:mCitrine-, (j) Kap3a:GFP- and (k) Dync2li1:GFP-labelled particles moving in anterograde and retrograde directions. (l) Disruption of Kif17 is not detrimental to the maintenance of OSN axonemes. Representative live en face confocal image of an OSN co-expressing AV-Kif17DN:GFP and AV-Arl13b:mCherry. (m) The presence of Kif17DN:GFP at distal tips (arrowheads) and in puncta along axonemes (arrows). (n,o) Kif17DN is transported to distal tips in IFT particles containing Kap3a. (n) Representative live en face confocal image of an OSN co-expressing AV-Kif17DN:mCherry and AV-Kap3a:GFP shows their co-localization in cilia and at ciliary distal tips (arrowheads). (o) Kymogram generated from a cilium of an OSN expressing (top) AV-Kif17DN:GFP and (middle) AV-Kap3a:mCherry. Scale bars, 10 μm (a–e,l,n); 2.5

μm (a–e,l,n); 2.5 μm (zoomed panels); 2.5

μm (zoomed panels); 2.5 μm (g); 10

μm (g); 10 μm × 30

μm × 30 s (h–k,o).

s (h–k,o).

Our time-lapse data indicates that both heterotrimeric kinesin-2 and Kif17 participate in IFT along the entire OSN axonemes. We therefore reasoned that the presence of OSN cilia distal segments may not depend solely on the function of Kif17 as is seen with OSM-3 in C. elegans amphid/phasmid channel cilia37. To test this hypothesis, we used a truncated dominant-negative version of Kif17 (Kif17DN) lacking the motor domain. Expression of Kif17DN was not detrimental to OSN cilia formation (Fig. 3l,m), and Kif17DN showed mobility along the entire axonemes via association with IFT particles containing Kap3a (Fig. 3n,o and Supplementary Movie 2). These data indicate that distal segment formation and/or maintenance in OSN cilia is not dependent on Kif17 alone, and that heterotrimeric kinesin-2 is capable of IFT trafficking along the entire length of OSN axonemes when Kif17 is disrupted. Thus, we conclude that OSN cilia use a unique and heretofore undescribed programme featuring at least two types of kinesin motors for trafficking along distal singlet microtubules.

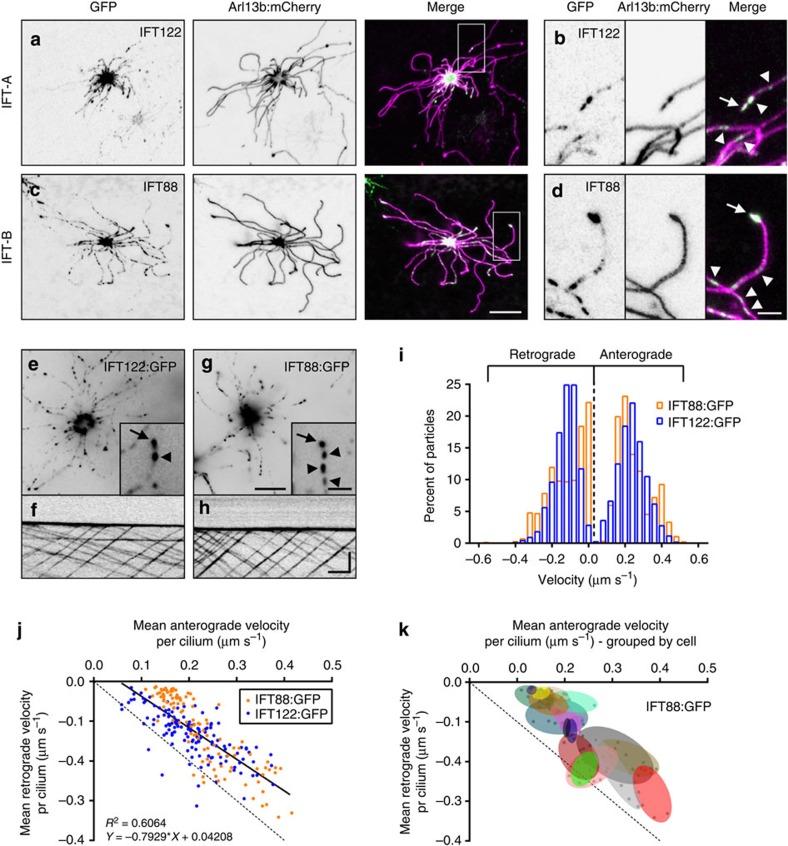

Stochastic variation in IFT velocities among OSNs

The basic mechanistic principles by which IFT trains enable cargo transport within cilia are well established from work in homogeneous age-synchronous cell populations or groups of cells derived from an invariant lineage, but we have no understanding about IFT dynamics in the complex setting of a native mammalian tissue or in multiciliated cells. As individual OSNs differ from each other on many levels including odourant receptor expression, basal stimulation/activation state, age and spatial distribution, the OE is well suited for analysis of IFT dynamics in a heterogeneous context. We measured IFT velocities using FP-tagged components of the IFT-A and IFT-B subcomplexes, which undergo robust bidirectional motility along the full length of OSN cilia (Fig. 4a–h and Supplementary Movie 3). To differentiate anterograde versus retrograde trajectories, only IFT particles travelling in clear view of the ciliary tip were included in our analysis and are representative of IFT velocities specifically on the OSN distal segment. Velocities of both anterograde and retrograde IFT particles ranged from nearly stationary to approaching 0.6 μm

μm s−1 (Fig. 4i), with anterograde and retrograde means of 0.22±0.08 and −0.14±0.08

s−1 (Fig. 4i), with anterograde and retrograde means of 0.22±0.08 and −0.14±0.08 μm

μm s−1, respectively (n=2,316 IFT122:GFP-labelled particles, 1,941 IFT88:GFP-labelled particles, 300 cilia, 55 OSNs and 9 mice). In addition, the magnitude of anterograde and retrograde mean particle velocities within individual OSN cilia strongly correlate (Fig. 4j, Pearson’s coefficient R2=0.6064). Notably, we saw stochastic variation in anterograde and retrograde velocities among neurons and the velocities measured in multiple cilia within individual cells were more similar to each other than to cilia on other cells (Fig. 4k; permutation test with 20,000 iterations, P<0.0001 for both anterograde and retrograde velocities, see Methods) (n=1,941 IFT88:GFP-labelled particles, 160 cilia, 25 OSNs and 5 mice). Thus, differential regulation of IFT velocity occurs across the OSN population and the velocities of IFT particles in the many cilia projecting from a single OSN are controlled together within each cell.

s−1, respectively (n=2,316 IFT122:GFP-labelled particles, 1,941 IFT88:GFP-labelled particles, 300 cilia, 55 OSNs and 9 mice). In addition, the magnitude of anterograde and retrograde mean particle velocities within individual OSN cilia strongly correlate (Fig. 4j, Pearson’s coefficient R2=0.6064). Notably, we saw stochastic variation in anterograde and retrograde velocities among neurons and the velocities measured in multiple cilia within individual cells were more similar to each other than to cilia on other cells (Fig. 4k; permutation test with 20,000 iterations, P<0.0001 for both anterograde and retrograde velocities, see Methods) (n=1,941 IFT88:GFP-labelled particles, 160 cilia, 25 OSNs and 5 mice). Thus, differential regulation of IFT velocity occurs across the OSN population and the velocities of IFT particles in the many cilia projecting from a single OSN are controlled together within each cell.

(a,c,e) Representative live en face confocal images of native OE ectopically expressing components of the IFT particle subcomplexes. Localization of (A) IFT-A subcomplex protein IFT122:GFP and (c) IFT-B subcomplex protein IFT88:GFP in the OSN knob and in puncta along the length of cilia as revealed by Arl13b:mCherry co-expression. Zoomed colour-shifted images show accumulation of (b) IFT122:GFP and (d) IFT88:GFP at the distal tips of cilia (arrow) and in puncta along axonemes (arrowheads). (e,g) Representative live en face TIRFm images captured from OSNs expressing IFT122:GFP or IFT88:GFP. Two-second exposures are shown. Insets show GFP puncta on OSN ciliary axonemes (arrowheads) and accumulations at ciliary distal tips (arrows). (f,h) Representative line-scan kymograms generated from single cilia of OSNs ectopically expressing the indicated IFT protein. (i) Histogram distribution of IFT122:GFP and IFT88:GFP particle velocities. IFT122:GFP, n=1,315 anterograde particles and 1,001 retrograde particles, 4 mice; IFT88:GFP, n=1,060 anterograde particles and 881 retrograde particles, 5 mice. (j) Plot of individual cilium mean anterograde versus retrograde velocities, showing a positive association between the magnitude of anterograde and retrograde velocities in a given cilium (Pearson’s coefficient R2=0.6064). Linear regression is shown. (k) Plot of individual cilium mean anterograde versus retrograde velocities, clustered by OSN (each group of points encapsulated by a coloured oval represents the cilia from a single cell). IFT88:GFP data set is shown. Scale bars, 10 μm (a,c); 2.5

μm (a,c); 2.5 μm (b,d); 10

μm (b,d); 10 μm, inset, 2.5

μm, inset, 2.5 μm (e,g); 5

μm (e,g); 5 μm × 10

μm × 10 s (f,h).

s (f,h).

Although the majority of IFT particles in OSN cilia moved with constant velocity, in some instances we observed non-processive particle trajectories (Supplementary Fig. 3). These included single-particle velocity changes (stalling/restarting and mid-cilium direction reversal), which may represent spatio-temporal events where IFT particles perform maintenance on the axoneme through delivery and/or pickup of cargo38. We also observed unidirectional particle interactions (fusions and fissions) and rare anterograde and retrograde particle collision/fusion events. These observations imply that individual microtubules may be simultaneously used by both unidirectional and opposing particles, and that particle remodelling is not strictly limited to events at the ciliary base and microtubule tips39. Finally, increased particle size was occasionally observed, which may reflect a form of IFT avalanching at the ciliary base or tip as described in C. reinhardtii40 and/or snowballing from multiple fusion events along the axoneme.

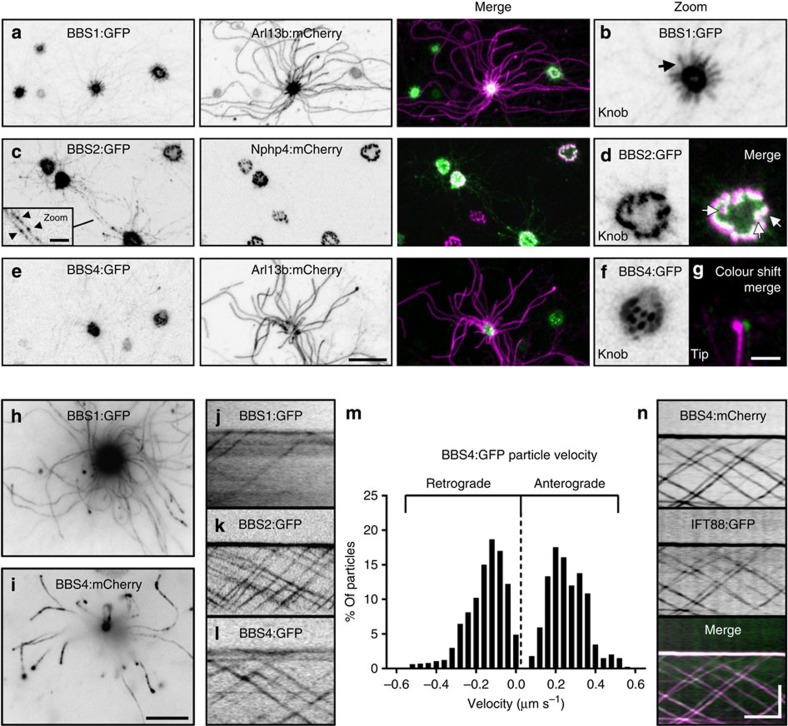

The BBSome is a constituent of the mammalian OSN IFT complex

Proteins homologous to those associated with human BBS participate in IFT in invertebrates41,42,43. Although various lines of evidence have implicated mammalian BBS proteins as being resident within pericentriolar satellites44, basal bodies45 and cilia46, no report has demonstrated that mammalian BBS proteins traffic with IFT. We examined constituents of the core BBSome46 via expression of FP-tagged BBS1, BBS2 and BBS4 in OSNs. Confocal microscopy revealed strong enrichment of BBSome proteins within OSN knobs (Fig. 5a–f), consistent with basal body localization. In addition, BBS2:GFP was readily detectable in puncta along OSN axonemes (Fig. 5c inset), whereas BBS1:GFP was discretely present in the proximal-most regions of OSN axonemes (Fig. 5b) and BBS4:GFP was occasionally detected at ciliary tips (Fig. 5g). Using TIRFm, we observed that each of the three BBSome fusion proteins undergo bidirectional particle movement along the length of OSN cilia (Fig. 5j–l and Supplementary Movie 4) and do so with velocities similar to FP-tagged IFT proteins (Fig. 5m and Table 1; n=2,881 BBS4:GFP-labelled particles, 143 cilia, 48 OSNs and 7 mice). We next co-expressed BBS4:mCherry and IFT88:GFP, and found that BBS4:mCherry was present in all observed IFT88:GFP-labelled particles (Fig. 5n and Supplementary Movie 5), verifying that the BBSome is in fact a constituent of the IFT particle in OSN cilia.

(a–f) Representative live en face confocal images of native OE ectopically expressing components of the BBSome. (a) Image of OE from animal transduced with AV-BBS1:GFP and AV-Arl13b:mCherry. BBS1:GFP concentrates strongly within the OSN knob and is distributed uniformly along the proximal-most segments (arrow) of OSN cilia as shown in the zoomed image (a). (c,d) Image of OE from animal transduced with AV-BBS2:GFP and AV-Nphp4:mCherry. (c) BBS2:GFP concentrates strongly within the OSN knob and is visible along ciliary axonemes in puncta (inset, arrowheads). (d) BBS2:GFP is enriched in basal bodies in the OSN knob. Merged panel shows BBS2:GFP basal body localization in close association with transition zones (arrows) as revealed by Nphp4:mCherry labelling. (e) Image of OE from animal transduced with AV-BBS4:GFP and AV-Arl13b:mCherry. BBS4:GFP concentrates strongly within the OSN knob. (f) Zoomed panel showing a transduced OSN knob where BBS4:GFP appears to localize at basal bodies. (g) Merged and zoomed panel shows accumulation of BBS4:GFP at the tip of an OSN cilium as revealed by Arl13b:mCherry labelling. (h–n) TIRFm uncovers BBSome protein association with IFT particles in OSN cilia. (h,i) Collapsed maximum intensity projection of TIRFm time-series images captured from OSNs ectopically expressing (h) AV-BBS1:GFP or (i) AV-BBS4:GFP. The collapsed time series show that both BBS1:GFP and BBS4:GFP are present in OSN cilia. (j–l) BBSome proteins show bidirectional particle movement in OSN cilia. Line-scan kymograms of cilia on OSNs ectopically expressing (j) AV-BBS1:GFP, (k) AV-BBS2:GFP or (l) AV-BBS4:GFP were generated from TIRF time-series acquisitions from native OE. (m) Histogram distribution of BBS4:GFP particle velocities. n=1,735 anterograde particles and 1,146 retrograde particles. (n) BBS4:mCherry associates with IFT particles. Representative kymogram was generated from a cilium of an OSN co-expressing AV-BBS4:mCherry and AV-IFT88:GFP. Scale bars, 10 μm (a,c,e); 2.5

μm (a,c,e); 2.5 μm (inset of c); 2.5

μm (inset of c); 2.5 μm (b,d,f,g); 10

μm (b,d,f,g); 10 μm (h,i); 5

μm (h,i); 5 μm × 10

μm × 10 s (j–l,n).

s (j–l,n).

Table 1

| Species/cell type | Marker | Length (μm) | Anterograde (μm s−1) s−1) | Retrograde (μm s−1) s−1) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. reinhardtii | DIC | 12 | 1.8 | 3.1 | Iomini et al.67 |

| C. reinhardtii | IFT20:GFP | 12 | 2.1 | 2.5 | Lechtreck et al.43 |

| C. reinhardtii | IFT27:GFP | 2–4 | ~1.6 | nd | Engel et al.68 |

| C. reinhardtii | IFT27:GFP | 6–8 | ~2.0 | nd | Engel et al.68 |

| C. reinhardtii | IFT27:GFP | 10+ | ~2.3 | nd | Engel et al.68 |

Trypanosoma brucei (27 °C) °C) | GFP:IFT52, GFP:DHC2.1 | 22.3 | 2.4 (1.5)* | 5.6 | Buisson et al.39 |

T. brucei (35 °C) °C) | GFP:IFT52, GFP:DHC2.1 | 22.3 | 3.2 (2.2)* | 7.4 | Buisson et al.39 |

| C. elegans/Amphid-middle | OSM-6:GFP | 4 | 0.68 | 1.2 | Snow et al.37 |

| C. elegans/Amphid-distal | OSM-6:GFP | 2.5 | 1.3 | 1.1 | Snow et al.37 |

| Mus musculus/LLC-PK1 | IFT20:GFP | ~6 | ~0.6 | ~0.7 | Follit et al.14 |

| M. musculus/IMCD3 | IFT88:YFP | 6 | 0.38 | 0.56 | Tran et al.13 |

| M. musculus/MEF | IFT88:GFP | ~3 | 1.09 | 0.72 | He et al.18 |

| M. musculus/OSN-distal | IFT122:GFP | 2.5–100+ | 0.22 | 0.14 | Current work |

| M. musculus/OSN-distal | IFT88:GFP | 2.5–100+ | 0.23 | 0.14 | Current work |

| M. musculus/OSN-distal | Kif17:mCitrine | 2.5–100+ | 0.23 | nd | Current work |

| M. musculus/OSN-distal | Kif17DN:GFP | 2.5–100+ | 0.23 | nd | Current work |

| M. musculus/OSN-distal | BBS4:GFP | 2.5–100+ | 0.24 | 0.17 | Current work |

Nd, not determined.

*Subset of slow particle velocities.

Assembly of the BBSome depends up the activity of a BBS–chaperonin complex containing BBS6, BBS10 and BBS12 (ref. 47). As BBS10 and BBS12 are present at or near basal bodies48 where the BBSome is most abundant in primary ciliated cells, we hypothesized that they may also associate with the BBSome during IFT in OSN cilia. Confocal analysis revealed BBS10:GFP localization almost exclusively in OSN knobs (Supplementary Fig. 4). Within the OSN knob, however, BBS10:GFP did not associate with all basal bodies as is typical for BBS proteins; instead, BBS10 accumulated as a single focus (Supplementary Fig. 4b–e). Remarkably, the BBS10:GFP focus was highly dynamic, displaying constant mobility (Supplementary Fig. 4f). It is enticing to speculate that BBS10 and other components of the BBS–chaperonin complex are resident within a single pericentriolar endosome that actively shuttles throughout the OSN knob to provide support to each olfactory cilium. Using TIRFm on OSNs co-expressing BBS10:GFP and BBS4:mCherry, we observed only rare, transient association of BBS10 with IFT particles (Supplementary Fig. 4g). Thus, we conclude that the major function of the BBS–chaperonin complex in BBSome assembly is performed outside of OSN cilia before incorporation of the BBSome into IFT particles.

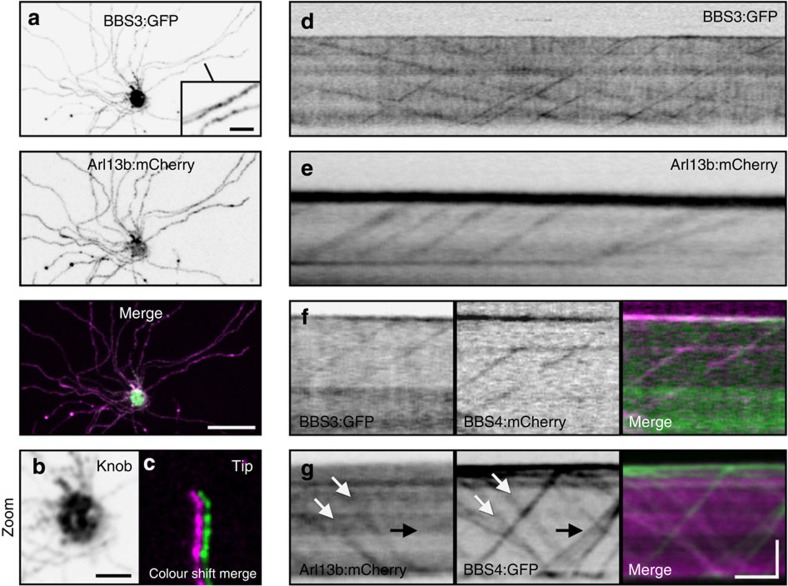

Peripheral membrane Arl proteins are OSN IFT cargoes

We next examined peripheral ciliary membrane Arl proteins. Arl6 (hereafter referred to as BBS3) is required for BBSome recruitment onto membranes in vitro49 and for localization of the BBSome within mammalian cilia on cultured cells50. In C. elegans, BBS3 and Arl13b homologues move bidirectionally within cilia, suggesting they associate with IFT41,51. Similar to Arl13b:mCherry, we observed BBS3:GFP throughout the full length of OSN axonemes (Fig. 6a,c). Remarkably, both BBS3:GFP and Arl13b:mCherry showed discrete bidirectional ciliary transport when imaged by TIRFm (Fig. 6d–g and Supplementary Movie 6). To assess the stoichiometry of BBS3 and Arl13b association with IFT particles, we co-expressed each protein with FP-tagged BBS4 and performed dual colour time-lapse TIRFm. Although BBS3:GFP appeared to co-localize with all BBS4:mCherry-labelled particles (Fig. 6f), Arl13b:mCherry was clearly absent from most (69.2%) BBS4:GFP particles (n=340) (Fig. 6g and Supplementary Movie 7), indicating that Arl13b is an intermittent IFT cargo and not a core constituent of the IFT machinery.

(a–c) Representative live en face confocal images of native OE ectopically co-expressing AV-BBS3:GFP and AV-Arl13b:mCherry. (a) BBS3:GFP is present along OSN ciliary axonemes. Inset shows zoomed image of two axonemes decorated with BBS3:GFP. (b) Zoomed image of the OSN knob showing BBS3:GFP accumulation. (c) Zoomed and colour-shifted image of an OSN ciliary distal tip showing co-localization of BBS3:GFP and Arl13b:mCherry. (d) Line-scan kymogram generated from a TIRFm time series of a BBS3:GFP AV-transduced OSN showing bidirectional movement of BBS3:GFP in an OSN cilium. (e) Line-scan kymogram generated from a TIRFm time series of an Arl13b:mCherry AV-transduced OSN showing particle movement of Arl13b:mCherry in an OSN cilium. (f) Line-scan kymogram of an OSN cilium co-expressing AV-BBS3:GFP and AV-BBS4:mCherry. (g) Line-scan kymogram of an OSN cilium co-expressing AV-Arl13b:mCherry and AV-BBS4:GFP. White arrows highlight a particle possessing both Arl13b:mCherry and BBS4:GFP. Black arrow indicates a group of particles that are labelled by BBS4:GFP but not Arl13b:mCherry. Scale bars, 10 μm (a); 2.5

μm (a); 2.5 μm (a (inset), b,c); 5

μm (a (inset), b,c); 5 μm × 10

μm × 10 s (d–g).

s (d–g).

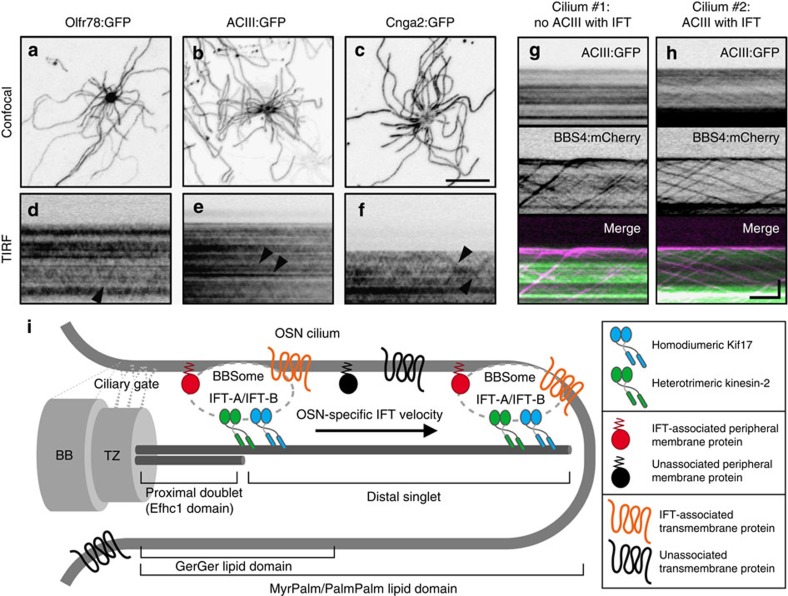

Polytopic signalling proteins rarely associate with OSN IFT

A major unanswered question is how olfactory receptors and other ciliary transmembrane proteins are trafficked within cilia. Evidence from invertebrates has demonstrated the capacity of transient receptor potential vanilloid channels to processively traffic with IFT52,53. By contrast, Ye et al.16 recently reported that in mammalian digitonin-permeablized cells, the G protein-coupled receptor SSTR3 and Smo only associate with IFT over short intervals and more often move by diffusion. To address whether mammalian transmembrane signalling proteins use IFT for ciliary trafficking within native OSNs, we expressed an FP-tagged odourant receptor, adenylate cyclase and a subunit of the olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel (Olfr78:GFP, ACIII:GFP and CNGA2:GFP, respectively). By confocal microscopy, each FP-tagged signalling protein showed distribution throughout OSN ciliary membranes (Fig. 7a–c). Through TIRFm, we discerned brief translocation events for each FP-tagged protein (Fig. 7d–f), reminiscent of disordered SSTR3 and Smo movement in cultured cell cilia16. To verify whether these movements correspond to IFT particles, we co-expressed ACIII:GFP and BBS4:mCherry, and found that ACIII:GFP movements were indeed coincident with IFT trafficking (Fig. 7h and Supplementary Movie 8). Interestingly, only a fraction of all IFT particles (14.4% of 479 particles captured from 60 cilia on 9 cells) were associated with ACIII and, moreover, only a fraction of all cilia (36.7%) showed any IFT-associated ACIII translocation during the given interval of data acquisition (Fig. 7g,h). Our data indicate that although transmembrane signalling proteins can use IFT for movement within OSN cilia, processive translocation events are rare at steady state, and we predict the function of these proteins is probably not dependent on constant association with IFT.

(a–c) Representative confocal images of AV-transduced OSNs expressing (a) Olfr78:GFP, (b) ACIII:GFP or (c) Cnga2:GFP. Each FP-tagged olfactory signalling protein was distributed along the full length of OSN cilia. (d–f) Representative time-lapse kymograms generated from cilia on AV-transduced OSNs expressing (d) Olfr78:GFP, (e) ACIII:GFP or (f) Cnga2:GFP. In each panel, occasional IFT-like translocation events are seen (arrowheads). (g,h) Representative time-lapse kymograms generated from two cilia on a single AV-transduced OSN co-expressing ACIII:GFP and BBS4:mCherry. In g, no association of ACIII with BBS4 is seen. In h, several BBS4-labelled IFT particles carry ACIII. Scale bars, 10 μm (a–c); 5

μm (a–c); 5 μm × 10

μm × 10 s (d–h). (i) Model of ciliary organization and IFT in OSNs. OSN cilia feature short (~2.5

s (d–h). (i) Model of ciliary organization and IFT in OSNs. OSN cilia feature short (~2.5 μm) doublet proximal microtubules that transition to singlets that can span more than 100

μm) doublet proximal microtubules that transition to singlets that can span more than 100 μm. The OSN ciliary membrane gate located at or near the basal body (BB)/transition zone (TZ) complex is permissive to the ciliary entry of prenylated and acylated proteins, which differentially partition once within the OSN ciliary membrane. The mammalian OSN IFT particle comprises IFT-A, IFT-B and BBSome particle subcomplexes, and associates with both homodimeric Kif17 and heterotrimeric kinesin-2 along the full axoneme length. OSN IFT particles intermittently carry both peripheral membrane-associated proteins and polytopic olfactory signalling proteins as cargoes.

μm. The OSN ciliary membrane gate located at or near the basal body (BB)/transition zone (TZ) complex is permissive to the ciliary entry of prenylated and acylated proteins, which differentially partition once within the OSN ciliary membrane. The mammalian OSN IFT particle comprises IFT-A, IFT-B and BBSome particle subcomplexes, and associates with both homodimeric Kif17 and heterotrimeric kinesin-2 along the full axoneme length. OSN IFT particles intermittently carry both peripheral membrane-associated proteins and polytopic olfactory signalling proteins as cargoes.

Discussion

Genetic anomalies disrupting IFT or BBS proteins manifest a wide array of variably penetrant disease pathologies that arise from dysfunction of cilia found on cells of various tissues. In general, the genetic loci underlying clinically distinct ciliopathies are coincident with biochemical data showing interactions between their encoded proteins and cooperation as a functional unit54. However, genetic and phenotypic overlap among ciliopathies predicts that some ciliary units functionally interact. In support of this notion, our data reveal for the first time the BBSome as a constituent of the mammalian olfactory IFT particle and implies that altered (but not ablated) IFT underlies BBS disease pathology. Interestingly, ciliation of the OE, but not ciliation in most other tissues, is dependent on normal BBSome function8,9,10, suggesting the precise role of BBS proteins in IFT will vary by cell type, thereby influencing disease penetrance in different tissues. This is reflected in lower eukaryotes where loss of BBS proteins has species-specific consequences. In C. elegans the BBSome is essential for IFT particle integrity and motor coordination37,55,56, but in C. reinhardtii BBS proteins are dispensable for IFT and flagellar biogenesis34. C. reinhardtii BBSome proteins associate with only a subset of IFT particles, whereas IFT particles in OSN cilia show a 1:1 ratio of BBS protein labelling. This 1:1 stoichiometry may represent a critical requirement specifically in OSNs for BBS proteins to facilitate assembly and/or maintenance of cilia via modulation of the IFT machinery. The mammalian BBSome may function similar to its role in C. elegans where the coupling of IFT-A and IFT-B into a complete unit is dependent on the presence of the BBS proteins. The inability of the A and B subcomplexes to form a fully functional unit would probably have major ramifications on their ability to properly maintain the remarkably long axonemes of OSN cilia. Alternatively, the BBSome itself may provide docking sites for IFT cargoes that are necessary for assembly/maintenance of OSN cilia. Although biochemical data is lacking, genetic disruption of a BBS protein combined with reduced IFT88 expression exacerbates ciliopathy phenotypes in mouse57 and IFT27 mutations give rise to BBS phenotypes in humans7, together demonstrating a potential functional link between the mammalian BBSome and IFT. Direct analysis of IFT assembly in the context of BBS mutant OSNs should provide insight into the functional relationship between the mammalian BBSome and IFT in the future. In addition to alterations in IFT function, the loss of OSN cilia seen in BBS mutant animals may also occur as a consequence of compromised ciliary membrane delivery, a role in which the BBSome is implicated49. As OSN cilia require relatively large amounts of membrane to encapsulate their full length, ciliary membrane defects due to BBS mutations might have a greater adverse effect on the length of these cilia compared with cilia on other cell types.

The current model of proximal–distal kinesin-based axoneme assembly, generated from studies in C. elegans amphid/phasmid channel sensory cilia, states that two motor complexes cooperate to build distinct compartments of the cilium; the Kif17 homologue OSM-3 is solely responsible for distal singlet microtubule biogenesis and heterotrimeric kinesin-2 mediates IFT in cooperation with OSM-3 only along the proximal segment20,37. This model is incompatible with our data showing that Kap3a travels throughout OSN cilia. Interestingly, in C. elegans dyf-5 MAP kinase loss-of-function mutants, the heterotrimeric kinesin-2 motor abnormally gains access to the distal segment, suggesting that the underlying microtubule architecture itself does not dictate kinesin usage58. Thus, a divergent phosphorylation programme may be responsible for the differential localization of heterotrimeric kinesin-2 in OSN cilia versus C. elegans amphid/phasmid channel cilia. We also find that Kif17 is dispensable for both OSN distal segment formation/maintenance (Fig. 3) and for sustaining anterograde velocity (Table 1). Although this data is in contrast with the ciliogenic role of OSM-3 in C. elegans amphid/phasmid channel cilia distal segments, it is consistent with the dispensability of OSM-3 in amphid wing `C' cell ciliogenesis59 and in the formation of amphid wing `B' (AWB) cell distal segments60. However, in AWB cilia the heterotrimeric kinesin-2 is nevertheless restricted from distal segments, highlighting a divergence between AWB and OSN cilia as well60. In support of our findings, disruption of Kif17 in cultured cells affects ciliary cargo trafficking without having an essential function in ciliogenesis61, and genetic ablation of Kif17 is apparently not inhibitory to ciliation in mice62. Instead, formation of OSN ciliary distal segments is probably facilitated by one or more other kinesins and our data points to heterotrimeric kinesin-2, which distinctively participates in IFT along the full length of OSN axonemes. Indeed, heterotrimeric kinesin-2 is solely responsible for proximal and distal segment formation in the cilia of Drosophila olfactory receptor neurons63. Overall, our data uncovers a unique collaboration between the heterotrimeric and homodimeric kinesin-2 motors in OSN cilia and further demonstrates how kinesin usage is diversified in different organisms and cell types.

IFT velocities significantly vary among neighbouring OSNs. This is not surprising, considering the extent of heterogeneity that defines the OE. Each OSN within the olfactory system predominantly expresses one of ~1,000 odourant receptors64,65; the OE therefore comprises subpopulations of cells that are differentially activated by various stimuli. As changing intracellular cyclic AMP and calcium influences IFT velocity17, we hypothesize that differential basal stimulation through environmental odours could have downstream effects to produce the cell-by-cell variation in IFT dynamics we observed. Similarly, the stochastic variation may be influenced by spatial distribution of individual OSNs within the OE or their age/maturation state.

Delineating the mechanisms of ciliary cargo trafficking, and membrane protein trafficking in particular, remains a key area of ongoing research interest. Recent data from single-molecule imaging in cultured cells suggests that individual ciliary membrane signalling receptors dynamically switch between short bursts of active transport by IFT and longer intervals of passive diffusion16. Likewise, clusters of flagellar membrane glycoproteins transiently associate with moving IFT particles in C. reinhardtii66. However, previous ensemble imaging has shown that populations of certain membrane proteins can associate with IFT particles over comparatively longer distances52,53. Our ensemble data showing peripheral membrane Arl proteins and transmembrane olfactory signalling proteins undergoing bouts of processive translocation in OSN cilia clearly demonstrates a capacity for these cargoes to use IFT in their trafficking in a native mammalian setting. However, the associations between IFT and the cargo proteins analysed here are intermittent and infrequent among OSN cilia and particles within cilia, suggesting that continuous association between cargo and particle is not essential to the normal function of these proteins.

Overall, from this work we have deconstructed mammalian OSN cilia axoneme and membrane organization, the composition and dynamic properties of OSN IFT and the degree to which IFT contributes to peripheral and transmembrane protein trafficking. Our data establish for the first time BBS protein participation in vertebrate IFT and provide novel insight into how kinesin motors are used in OSN cilia (Fig. 7i). Although invertebrate studies have informed our understanding of the players involved in ciliary transport, our findings highlight divergent qualities of mammalian IFT. In addition, the unique aspects of OSN IFT versus other mammalian cell types (Table 1) underscores the necessity to ascertain how cellular specification of the IFT machinery affects tissue-specific ciliopathy disease penetrance.

Methods

Mice

CD1 and GFP-CETN2 (Jackson Laboratory) mice were housed at the University of Florida. All procedures were approved by the University Committee for the Use and Care of Animals. Unless otherwise stated, two to three mice were used in each experimental condition.

Scanning electron microscopy

After deep anaesthesia and transcardial perfusion with 2% glutaraldehyde, 0.15 M cacodylate in water, olfactory tissue was processed using the OTOTO protocol. Analysis was performed on an Amray (Drogheda, Ireland) 1910FE field emission scanning electron microscope at 5

M cacodylate in water, olfactory tissue was processed using the OTOTO protocol. Analysis was performed on an Amray (Drogheda, Ireland) 1910FE field emission scanning electron microscope at 5 kV and recorded digitally with Semicaps software.

kV and recorded digitally with Semicaps software.

Constructs

Plasmids containing complementary DNA inserts used in this study were generously provided as follows: Nphp4:mCherry and IFT88 (B.K.Y., UAB); GFP:Efhc1 (K.Y., RIKEN); Arl13b (T.C., Emory); IFT122:GFP (J.E., UGA); Kap3a (T.S., Johns Hopkins); Olfr78 (J.P., Johns Hopkins); ACIII (R.R., Johns Hopkins); BBS1 (V.C.S., Iowa); and BBS2, BBS3, BBS4 and BBS10 (K.M., Ohio State). Dync2li1 was amplified from cDNA generated from mouse whole eye RNA. Lipid-anchored GFP constructs were generated by annealing oligonucleotides encoding the 13 amino-terminal residues from Lyn kinase (MyrPalm), the 20 N-terminal residues from GAP43 (PalmPalm) and the 9 carboxy-terminal residues from the guanine triphosphatase Rho (GerGer) into the KpnI and AgeI sites of pEGFP-N1 (Clontech). All cloning primer sequences are available on request.

Analysis of ectopic expression in mouse OSNs

For expression in native tissue, recombinant GFP-, mCherry- or mCitrine-flanked cDNAs were inserted into the adenoviral vector pAD/V5/−dest and virus was propagated using the ViraPower protocol (Invitrogen). AV particles were isolated with the Virapur Adenovirus mini purification Virakit (Virapur, San Diego, CA) and dialysed in 2.5% glycerol, 25 mM NaCl and 20

mM NaCl and 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. Twenty-microlitre volumes of AV-containing constructs of interest were intranasally administered to the OE of pups at P7, P8 and P9. Transduced animals were killed for analysis on or after day P19.

mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. Twenty-microlitre volumes of AV-containing constructs of interest were intranasally administered to the OE of pups at P7, P8 and P9. Transduced animals were killed for analysis on or after day P19.

For immunostaining, mice were deeply anaesthetized and then cardiac perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde. The lower jaw, teeth and hair were removed from snouts before postfixation in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 h at 4

h at 4 °C. Snouts were then decalcified in 0.5

°C. Snouts were then decalcified in 0.5 M EDTA/ × PBS overnight, cryoprotected in 10%, 20% and 30% sucrose for 1

M EDTA/ × PBS overnight, cryoprotected in 10%, 20% and 30% sucrose for 1 h, 1

h, 1 h and overnight, respectively, at 4

h and overnight, respectively, at 4 °C, and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Tissue-Tek). Coronal cryosections were sliced at a thickness of 10–12

°C, and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Tissue-Tek). Coronal cryosections were sliced at a thickness of 10–12 μm and mounted onto Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific). For immunostaining, cryosections were permeabilized and blocked with 0.3% Triton X-100 and 2% goat serum in PBS for 30

μm and mounted onto Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific). For immunostaining, cryosections were permeabilized and blocked with 0.3% Triton X-100 and 2% goat serum in PBS for 30 min. Samples were incubated with acetylated α-tubulin antibody (clone 6–11 B-1, Sigma T6793) diluted 1:1,000 in 2% goat serum in PBS for 1

min. Samples were incubated with acetylated α-tubulin antibody (clone 6–11 B-1, Sigma T6793) diluted 1:1,000 in 2% goat serum in PBS for 1 h at room temperature and washed three times with PBS. Cryosections were incubated in fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1

h at room temperature and washed three times with PBS. Cryosections were incubated in fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h, washed three times with PBS and mounted using Prolong Gold (Invitrogen). Fixed tissue imaging was performed on an Olympus Fluoview 500 confocal microscope equipped with a 405-nm laser diode with a 430- to 460-nm band-pass filter, a 488-nm laser with a 505- to 525-nm band-pass filter, a 543-nm laser with a 560-nm long-pass filter and a 633-nm laser with a 660-nm long-pass filter; original magnification × 60, 1.40 numerical aperture (NA) or × 100,1.35 NA oil objectives were used.

h, washed three times with PBS and mounted using Prolong Gold (Invitrogen). Fixed tissue imaging was performed on an Olympus Fluoview 500 confocal microscope equipped with a 405-nm laser diode with a 430- to 460-nm band-pass filter, a 488-nm laser with a 505- to 525-nm band-pass filter, a 543-nm laser with a 560-nm long-pass filter and a 633-nm laser with a 660-nm long-pass filter; original magnification × 60, 1.40 numerical aperture (NA) or × 100,1.35 NA oil objectives were used.

For confocal en face imaging of transduced OSNs, animals were anaesthetized with CO2, rapidly decapitated, split along the cranial midline and the OE was dissected out in PBS. Turbinates were placed in a tissue chamber and imaged on a Nikon TiE-PFS-A1R confocal microscope equipped with a 488-nm laser diode with a 510- to 560-nm band-pass filter and 561 laser with a 575- to 625-nm band-pass filter. A CFI Apo Lamda S × 60, 1.4 NA objective was used.

For en face TIRFm imaging of transduced OSNs, animals were anaesthetized with CO2, rapidly decapitated, split along the cranial midline and further prepared in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (124 mM NaCl, 3

mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 1

mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2

mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 1.25

mM CaCl2, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 26

mM NaH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 25

mM NaHCO3, 25 mM glucose) bubbled with 5% CO2/95% O2 for 10

mM glucose) bubbled with 5% CO2/95% O2 for 10 min before use. The rostral- and caudal-most portions of one hemisphere were removed, leaving the OE and olfactory bulb intact in the skull. The tissue was placed face down in the imaging chamber, bathed in 35

min before use. The rostral- and caudal-most portions of one hemisphere were removed, leaving the OE and olfactory bulb intact in the skull. The tissue was placed face down in the imaging chamber, bathed in 35 °C artificial cerebrospinal fluid and held in place with mesh netting. TIRFm time series were captured at 200

°C artificial cerebrospinal fluid and held in place with mesh netting. TIRFm time series were captured at 200 ms exposure for 2–3

ms exposure for 2–3 min on a Nikon Eclipse Ti-E/B inverted microscope equipped with a × 100 CFI APO TIRF 1.49 NA, × 1.5 tube lens, ZT488/561rpc dichroic, ZET488/561 × excitation filter, ZET488/561m-TRF emission filter (Chroma Technology) and an electron-multiplying charge-coupled device camera (iXon X3 DU897, Andor Technology). The 488-nm line of a fibre-coupled diode laser at incident power of 2

min on a Nikon Eclipse Ti-E/B inverted microscope equipped with a × 100 CFI APO TIRF 1.49 NA, × 1.5 tube lens, ZT488/561rpc dichroic, ZET488/561 × excitation filter, ZET488/561m-TRF emission filter (Chroma Technology) and an electron-multiplying charge-coupled device camera (iXon X3 DU897, Andor Technology). The 488-nm line of a fibre-coupled diode laser at incident power of 2 mw was used to illuminate a circular region of ~60

mw was used to illuminate a circular region of ~60 μm in diameter for capturing video sequences at 5–10

μm in diameter for capturing video sequences at 5–10 Hz. ImageJ was used to generate line-scan kymograms for measuring particle velocities from imported time series. Velocity was calculated with the following formula: tan(α*π/180)*b/c where α is angle, b is calibration in μm per pixel and c is exposure time per frame.

Hz. ImageJ was used to generate line-scan kymograms for measuring particle velocities from imported time series. Velocity was calculated with the following formula: tan(α*π/180)*b/c where α is angle, b is calibration in μm per pixel and c is exposure time per frame.

Statistical analysis

As our IFT velocity data set significantly violated the constant variance assumption of analysis of variance, we employed a non-parametric permutation test to assess the variability of IFT rates on the cell and population level using the following formula, to obtain test statistics:

The numerator reflects the variance between the cells and the denominator reflects the variance within the cells (that is, between the cilia); i is the cell index, j is the cilia index. The designating observations are denoted by yijk where k is the IFT particle index. The notations yij., yi.. and y... denote the average values of observations in a cilium, in a cell or in the entire population, respectively. Number of observations in a cilium were given as nij and number of observations in a cell were given as mi. Calculation of anterograde and retrograde observations gave statistics of 14.23 and 10.12, respectively. Next, the anterograde and retrograde observations were permuted and randomly shuffled across cells 20,000 times and the test statistics were calculated for each permutation. The P-values were calculated to be the percentages of the test statistics obtained from permutated data sets falling below the test statistics obtained from the observed data. For both the anterograde and retrograde data, the P-values were <0.0001, demonstrating that variations in IFT velocities among cells are significantly greater than variations among cilia in each cell.

Author contributions

C.L.W, J.C.M., P.M.J. and J.R.M. designed experiments. C.L.W., J.C.M., S.R.N. and P.M.J. performed experiments. C.L.W., J.C.M., P.M.J. and L.Z. generated reagents. Q.P. performed biostatistical analysis. K.V. provided equipment and reagents. C.L.W. and J.R.M. wrote the manuscript, with all authors providing input. C.L.W. made illustrations and generated figures. J.R.M. directed the project.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Williams, C. L. et al. Direct evidence for BBSome-associated intraflagellar transport reveals distinct properties of native mammalian cilia. Nat. Commun. 5:5813 10.1038/ncomms6813 (2014).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-4 and Supplementary Methods

Processive bidirectional trafficking of kinesin and dynein complex proteins in olfactory sensory cilia.

Disruption of Kif17 does not affect kinesin-2 trafficking to distal tips of olfactory sensory cilia.

Processive bidirectional trafficking of IFT-A and IFT-B subcomplex proteins in olfactory sensory cilia.

Processive bidirectional trafficking of BBSome proteins in olfactory sensory cilia.

Co-movement of BBS4 and IFT88 in olfactory sensory cilia.

Processive bidirectional trafficking of peripheral membrane-associated Arl proteins in olfactory sensory cilia

Co-movement of Arl13b and BBS4 in olfactory sensory cilia.

Co-movement of ACIII and BBS4 in olfactory sensory cilia

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Beyer and members of the University of Michigan Microscopy and Image Analysis Laboratory for assistance with scanning electron microscopy. We thank H.L. Kee, J. Pieczynski and additional members of the Martens and Verhey labs for valuable discussions and technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grants R01DC009606 (to J.R.M.), RO1070862 (to K.V.), T32DC00011 (to C.L.W.) and K99DC013555 (to J.C.M.).

References

- Ware S. M., Aygun M. G. & Hildebrandt F. Spectrum of clinical diseases caused by disorders of primary cilia. Proc. Am. Thoracic Soc. 8, 444–450 (2011). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Taschner M., Bhogaraju S. & Lorentzen E. Architecture and function of IFT complex proteins in ciliogenesis. Differentiation 83, S12–S22 (2012). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Halbritter J. et al.. Defects in the IFT-B component IFT172 cause Jeune and Mainzer-Saldino syndromes in humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 93, 915–925 (2013). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Huber C. & Cormier-Daire V. Ciliary disorder of the skeleton. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 160C, 165–174 (2012). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Perrault I. et al.. Mainzer-Saldino syndrome is a ciliopathy caused by IFT140 mutations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90, 864–870 (2012). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre J. C. et al.. Gene therapy rescues cilia defects and restores olfactory function in a mammalian ciliopathy model. Nat. Med. 18, 1423–1428 (2012). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Aldahmesh M. A. et al.. IFT27, encoding a small GTPase component of IFT particles, is mutated in a consanguineous family with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 3307–3315 (2014). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Mykytyn K. et al.. Bardet-Biedl syndrome type 4 (BBS4)-null mice implicate Bbs4 in flagella formation but not global cilia assembly. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 8664–8669 (2004). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tadenev A. L. et al.. Loss of Bardet-Biedl syndrome protein-8 (BBS8) perturbs olfactory function, protein localization, and axon targeting. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 10320–10325 (2011). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kulaga H. M. et al.. Loss of BBS proteins causes anosmia in humans and defects in olfactory cilia structure and function in the mouse. Nat. Genet. 36, 994–998 (2004). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum J. Intraflagellar transport. Curr. Biol. 12, R125 (2002). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis P. N., Ou G., Leroux M. R. & Scholey J. M. The sensory cilia of Caenorhabditis elegans. http://dx.doi.org/10.1895/wormbook.1.126.2 (2007). [Abstract]

- Tran P. V. et al.. THM1 negatively modulates mouse sonic hedgehog signal transduction and affects retrograde intraflagellar transport in cilia. Nat. Genet. 40, 403–410 (2008). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Follit J. A., Tuft R. A., Fogarty K. E. & Pazour G. J. The intraflagellar transport protein IFT20 is associated with the Golgi complex and is required for cilia assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 3781–3792 (2006). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Besschetnova T. Y., Roy B. & Shah J. V. Imaging intraflagellar transport in mammalian primary cilia. Methods Cell Biol. 93, 331–346 (2009). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ye F. et al.. Single molecule imaging reveals a major role for diffusion in the exploration of ciliary space by signaling receptors. Elife 2, e00654 (2013). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Besschetnova T. Y. et al.. Identification of signaling pathways regulating primary cilium length and flow-mediated adaptation. Curr. Biol. 20, 182–187 (2010). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- He M. et al.. The kinesin-4 protein Kif7 regulates mammalian Hedgehog signalling by organizing the cilium tip compartment. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 663–672 (2014). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Reese T. S. Olfactory cilia in the frog. J. Cell Biol. 25, 209–230 (1965). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins L. A., Hedgecock E. M., Thomson J. N. & Culotti J. G. Mutant sensory cilia in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 117, 456–487 (1986). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K. et al.. Rib72, a conserved protein associated with the ribbon compartment of flagellar A-microtubules and potentially involved in the linkage between outer doublet microtubules. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7725–7734 (2003). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sammeta N., Yu T. T., Bose S. C. & McClintock T. S. Mouse olfactory sensory neurons express 10,000 genes. J. Comp. Neurol. 502, 1138–1156 (2007). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Menco B. P. Ciliated and microvillous structures of rat olfactory and nasal respiratory epithelia. A study using ultra-rapid cryo-fixation followed by freeze-substitution or freeze-etching. Cell Tissue Res. 235, 225–241 (1984). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharias D. A., Violin J. D., Newton A. C. & Tsien R. Y. Partitioning of lipid-modified monomeric GFPs into membrane microdomains of live cells. Science 296, 913–916 (2002). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd T. et al.. The retinitis pigmentosa protein RP2 interacts with polycystin 2 and regulates cilia-mediated vertebrate development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 4330–4344 (2010). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Evans R. J. et al.. The retinitis pigmentosa protein RP2 links pericentriolar vesicle transport between the Golgi and the primary cilium. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 1358–1367 (2010). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tao B. et al.. Cystin localizes to primary cilia via membrane microdomains and a targeting motif. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20, 2570–2580 (2009). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Follit J. A., Li L., Vucica Y. & Pazour G. J. The cytoplasmic tail of fibrocystin contains a ciliary targeting sequence. J. Cell Biol. 188, 21–28 (2010). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Winckler B., Forscher P. & Mellman I. A diffusion barrier maintains distribution of membrane proteins in polarized neurons. Nature 397, 698–701 (1999). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gonzalo F. R. et al.. A transition zone complex regulates mammalian ciliogenesis and ciliary membrane composition. Nat. Genet. 43, 776–784 (2011). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C. L. et al.. MKS and NPHP modules cooperate to establish basal body/transition zone membrane associations and ciliary gate function during ciliogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 192, 1023–1041 (2011). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Craige B. et al.. CEP290 tethers flagellar transition zone microtubules to the membrane and regulates flagellar protein content. J. Cell Biol. 190, 927–940 (2010). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sang L. et al.. Mapping the NPHP-JBTS-MKS protein network reveals ciliopathy disease genes and pathways. Cell 145, 513–528 (2011). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q. et al.. A septin diffusion barrier at the base of the primary cilium maintains ciliary membrane protein distribution. Science 329, 436–439 (2010). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kee H. L. et al.. A size-exclusion permeability barrier and nucleoporins characterize a ciliary pore complex that regulates transport into cilia. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 431–437 (2012). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Dishinger J. F. et al.. Ciliary entry of the kinesin-2 motor KIF17 is regulated by importin-beta2 and RanGTP. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 703–710 (2010). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Snow J. J. et al.. Two anterograde intraflagellar transport motors cooperate to build sensory cilia on C. elegans neurons. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 1109–1113 (2004). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wren K. N. et al.. A differential cargo-loading model of ciliary length regulation by IFT. Curr. Biol. 23, 2463–2471 (2013). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Buisson J. et al.. Intraflagellar transport proteins cycle between the flagellum and its base. J. Cell Sci. 126, 327–338 (2013). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ludington W. B., Wemmer K. A., Lechtreck K. F., Witman G. B. & Marshall W. F. Avalanche-like behavior in ciliary import. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 3925–3930 (2013). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y. et al.. Mutations in a member of the Ras superfamily of small GTP-binding proteins causes Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nat. Genet. 36, 989–993 (2004). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Blacque O. E. et al.. Loss of C. elegans BBS-7 and BBS-8 protein function results in cilia defects and compromised intraflagellar transport. Genes Dev. 18, 1630–1642 (2004). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lechtreck K. F. et al.. The Chlamydomonas reinhardtii BBSome is an IFT cargo required for export of specific signaling proteins from flagella. J. Cell Biol. 187, 1117–1132 (2009). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. C. et al.. The Bardet-Biedl protein BBS4 targets cargo to the pericentriolar region and is required for microtubule anchoring and cell cycle progression. Nat. Genet. 36, 462–470 (2004). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ansley S. J. et al.. Basal body dysfunction is a likely cause of pleiotropic Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nature 425, 628–633 (2003). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Nachury M. V. et al.. A core complex of BBS proteins cooperates with the GTPase Rab8 to promote ciliary membrane biogenesis. Cell 129, 1201–1213 (2007). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Seo S. et al.. BBS6, BBS10, and BBS12 form a complex with CCT/TRiC family chaperonins and mediate BBSome assembly. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1488–1493 (2010). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Marion V. et al.. Transient ciliogenesis involving Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins is a fundamental characteristic of adipogenic differentiation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 1820–1825 (2009). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H. et al.. The conserved Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins assemble a coat that traffics membrane proteins to cilia. Cell 141, 1208–1219 (2010). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Yu D., Seo S., Stone E. M. & Sheffield V. C. Intrinsic protein-protein interaction-mediated and chaperonin-assisted sequential assembly of stable bardet-biedl syndrome protein complex, the BBSome. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 20625–20635 (2012). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Cevik S. et al.. Active transport and diffusion barriers restrict Joubert Syndrome-associated ARL13B/ARL-13 to an Inv-like ciliary membrane subdomain. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003977 (2013). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H. et al.. Intraflagellar transport is required for the vectorial movement of TRPV channels in the ciliary membrane. Curr. Biol. 15, 1695–1699 (2005). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K. et al.. Function and dynamics of PKD2 in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii flagella. J. Cell Biol. 179, 501–514 (2007). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- van Reeuwijk J., Arts H. H. & Roepman R. Scrutinizing ciliopathies by unraveling ciliary interaction networks. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, R149–R157 (2011). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ou G., Blacque O. E., Snow J. J., Leroux M. R. & Scholey J. M. Functional coordination of intraflagellar transport motors. Nature 436, 583–587 (2005). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Q. et al.. The BBSome controls IFT assembly and turnaround in cilia. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 950–957 (2012). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Seo S., Bugge K., Stone E. M. & Sheffield V. C. BBS proteins interact genetically with the IFT pathway to influence SHH-related phenotypes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 1945–1953 (2012). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Burghoorn J. et al.. Mutation of the MAP kinase DYF-5 affects docking and undocking of kinesin-2 motors and reduces their speed in the cilia of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 7157–7162 (2007). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J. E. et al.. Functional modulation of IFT kinesins extends the sensory repertoire of ciliated neurons in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Biol. 172, 663–669 (2006). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay S. et al.. Distinct IFT mechanisms contribute to the generation of ciliary structural diversity in C. elegans. EMBO J. 26, 2966–2980 (2007). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins P. M. et al.. Ciliary targeting of olfactory CNG channels requires the CNGB1b subunit and the kinesin-2 motor protein, KIF17. Curr. Biol. 16, 1211–1216 (2006). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X., Takei Y., Kido M. A. & Hirokawa N. Molecular motor KIF17 is fundamental for memory and learning via differential support of synaptic NR2A/2B levels. Neuron 70, 310–325 (2011). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Jana S. C., Girotra M. & Ray K. Heterotrimeric kinesin-II is necessary and sufficient to promote different stepwise assembly of morphologically distinct bipartite cilia in Drosophila antenna. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 769–781 (2011). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ressler K. J., Sullivan S. L. & Buck L. B. A zonal organization of odorant receptor gene expression in the olfactory epithelium. Cell 73, 597–609 (1993). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Vassar R., Ngai J. & Axel R. Spatial segregation of odorant receptor expression in the mammalian olfactory epithelium. Cell 74, 309–318 (1993). [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Shih S. M. et al.. Intraflagellar transport drives flagellar surface motility. Elife 2, e00744 (2013). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Iomini C., Babaev-Khaimov V., Sassaroli M. & Piperno G. Protein particles in Chlamydomonas flagella undergo a transport cycle consisting of four phases. J. Cell Biol. 153, 13–24 (2001). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Engel B. D., Ludington W. B. & Marshall W. F. Intraflagellar transport particle size scales inversely with flagellar length: revisiting the balance-point length control model. J. Cell Biol. 187, 81–89 (2009). [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6813

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms6813.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1038/ncomms6813

Article citations

The intraflagellar transport cycle.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 13 Nov 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39537792

Review

Ccrk-Mak/Ick signaling is a ciliary transport regulator essential for retinal photoreceptor survival.

Life Sci Alliance, 7(11):e202402880, 18 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39293864 | PMCID: PMC11412320

Evolutionary trajectory for nuclear functions of ciliary transport complex proteins.

Microbiol Mol Biol Rev, 88(3):e0000624, 12 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38995044

Review

The forkhead transcription factor Foxj1 controls vertebrate olfactory cilia biogenesis and sensory neuron differentiation.

PLoS Biol, 22(1):e3002468, 25 Jan 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 38271330 | PMCID: PMC10810531

Go to all (103) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

A global analysis of IFT-A function reveals specialization for transport of membrane-associated proteins into cilia.

J Cell Sci, 132(3):jcs220749, 11 Feb 2019

Cited by: 38 articles | PMID: 30659111 | PMCID: PMC6382014

Analysis of intraflagellar transport in C. elegans sensory cilia.

Methods Cell Biol, 93:235-266, 04 Dec 2009

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 20409821

Intraflagellar transport: mechanisms of motor action, cooperation, and cargo delivery.

FEBS J, 284(18):2905-2931, 18 Apr 2017

Cited by: 103 articles | PMID: 28342295 | PMCID: PMC5603355

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Measuring rates of intraflagellar transport along Caenorhabditis elegans sensory cilia using fluorescence microscopy.

Methods Enzymol, 524:285-304, 01 Jan 2013

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 23498746

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIDCD NIH HHS (7)

Grant ID: K99 DC013555

Grant ID: T32 DC000011

Grant ID: R01 DC009606

Grant ID: K99DC013555

Grant ID: R00 DC013555

Grant ID: R01DC009606

Grant ID: T32DC00011

PHS HHS (1)

Grant ID: R01070862