Abstract

Free full text

Enhancer-core-promoter specificity separates developmental and housekeeping gene regulation

Abstract

Gene transcription in animals involves the assembly of RNA polymerase II at core promoters and its cell type-specific activation by enhancers that can be located more distally1. However, how ubiquitous expression of housekeeping genes is achieved has remained less clear. In particular, it is unknown whether ubiquitously active enhancers exist and how developmental and housekeeping gene regulation is separated. An attractive hypothesis is that different core promoters might exhibit an intrinsic specificity towards certain enhancers2–6. This is conceivable as different core promoter sequence elements are differentially distributed between genes of different functions7, including elements that are predominantly at developmentally regulated or housekeeping genes, respectively8–10. Here, we show that thousands of enhancers in Drosophila melanogaster S2 cells and ovarian somatic cells (OSCs) exhibit a marked specificity towards one of two core promoters – one derived from a ubiquitously expressed ribosomal protein gene and another from a developmentally regulated transcription factor (TF) – and confirm the existence of these two classes for five additional core promoters from genes with diverse functions. Housekeeping enhancers are active across the two cell types, while developmental enhancers exhibit strong cell type specificity. Both enhancer classes differ in their genomic distribution, the functions of neighbouring genes, and these genes’ core promoter elements. In addition, we identify two TFs – DREF and Trl/GAGA – that bind and activate housekeeping versus developmental enhancers, respectively. Our results provide evidence for a sequence-encoded enhancer-core promoter specificity that separates developmental and housekeeping gene regulatory programs for thousands of enhancers and their target genes across the entire genome.

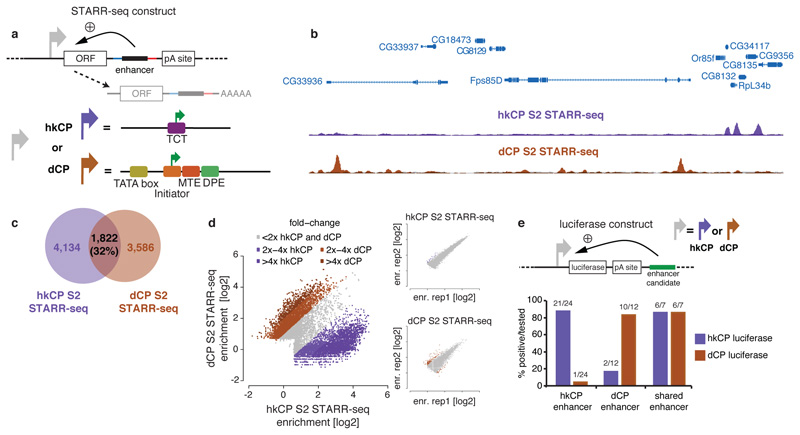

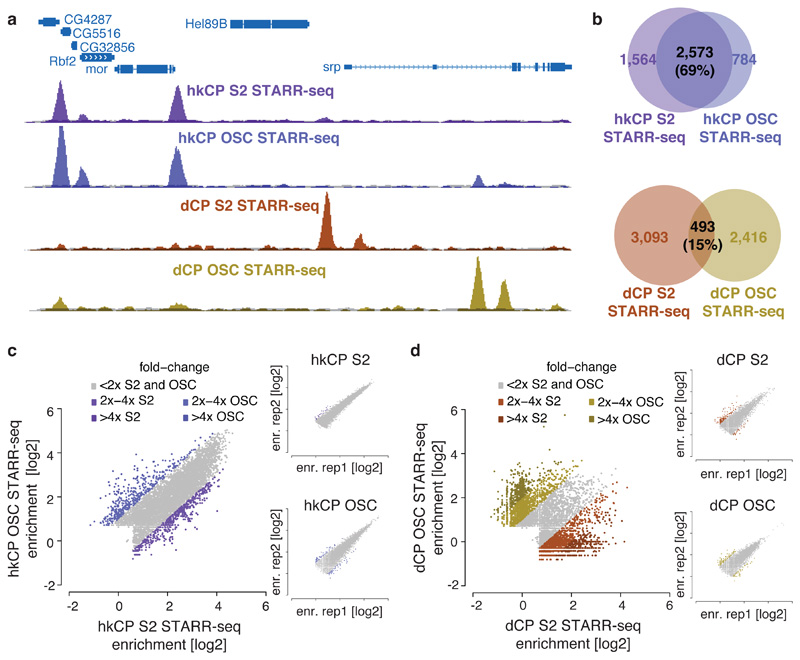

We chose the core promoter of Ribosomal protein gene 12 (RpS12) and a synthetic core promoter derived from the even-skipped TF11 as representative ‘housekeeping’ (hkCP) and ‘developmental’ (dCP) core promoters, respectively (Fig. 1a; Extended Data Figs 1 and and2)2) and tested the ability of all candidate enhancers genome-wide to activate transcription from these core promoters using Self-Transcribing Active Regulatory Region sequencing (STARR-seq)12 in Drosophila melanogaster S2 cells. This set-up allows the testing of all candidates in a defined sequence environment, which differs only in the core promoter sequences but is otherwise constant (see refs. 12,13).

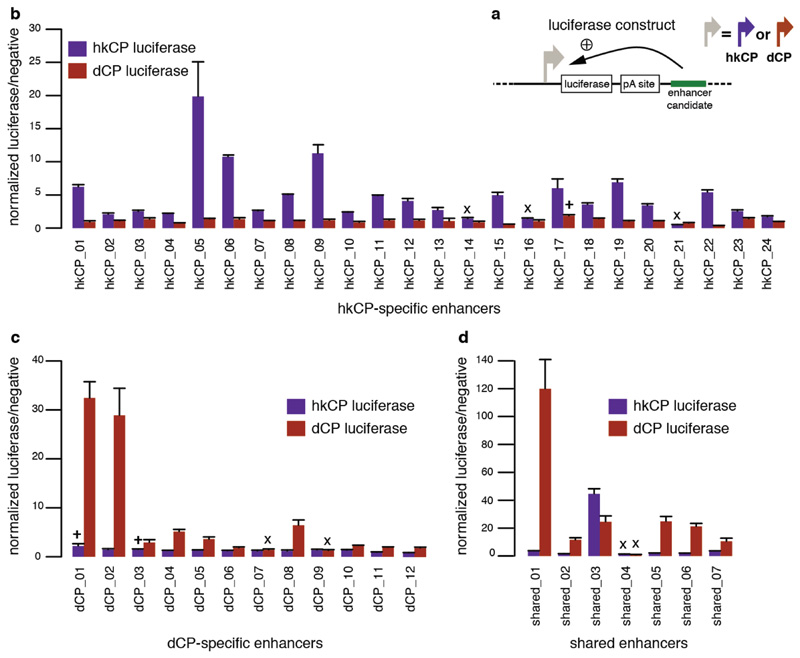

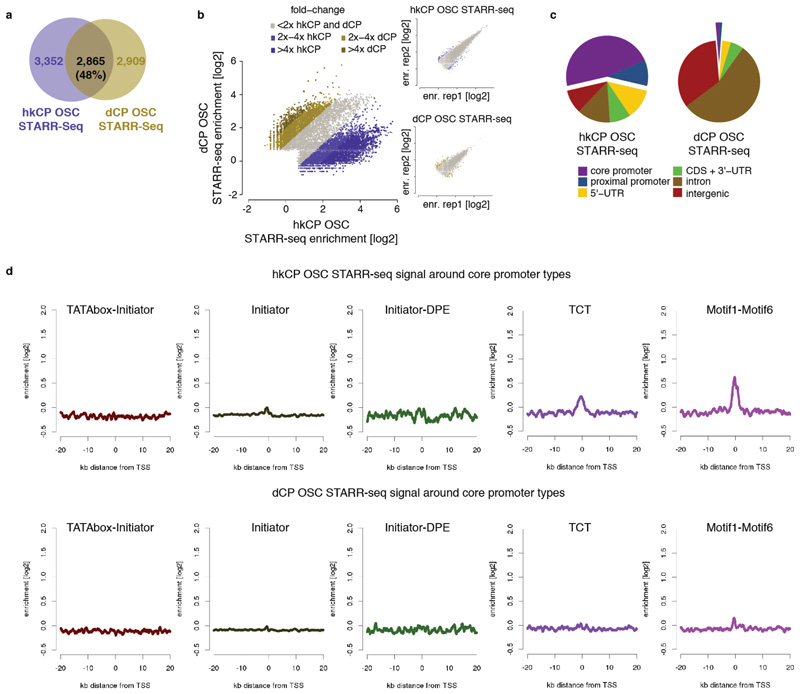

a, STARR-seq setup using the hkCP housekeeping (RpS12; purple) and dCP developmental core promoter (DSCP11; brown) b, Genome browser screenshot depicting STARR-seq tracks for both core promoters. c, Overlap of hkCP and dCP enhancers. d, hkCP versus dCP STARR-seq enrichments at enhancers (insets show replicates for hkCP and dCP; dCP data from ref. 12). e, hkCP, dCP, or shared enhancers that activate luciferase (>1.5-fold & P<0.05 [one-sided t-test]; n=3; Extended Data Figs 3 and and5)5) from hkCP (purple) or dCP (brown; numbers: positive/tested).

Two hkCP STARR-seq replicates were highly similar (genome-wide Pearson correlation coefficient [PCC] 0.98; Extended Data Fig. 1c) and yielded 5,956 enhancers, compared to 5,408 enhancers obtained for dCP data12 (Supplementary Table 1). Interestingly, the hkCP and dCP enhancers were largely non-overlapping (Fig. 1b,c) and the genome-wide enhancer activity profiles differed (PCC 0.38), as did the individual enhancer strengths: of the 11,364 enhancers, 8,144 (72%) activated one core promoter at least 2-fold more strongly than the other, a difference rarely seen in the replicate experiments for each of the core promoters (Fig. 1d). Indeed, 21 out of 24 hkCP-specific enhancers activated luciferase expression (>1.5-fold and t-test P<0.05) from the hkCP versus 1 from the dCP (Fig. 1e, Extended Data Fig. 3). Consistently, 10 out of 12 dCP-specific enhancers were positive with the dCP but only 2 with the hkCP, a highly significant difference (P=5.1x10-6, Fischer’s exact test) that confirms the enhancer–core promoter specificity observed for thousands of enhancers across the entire genome.

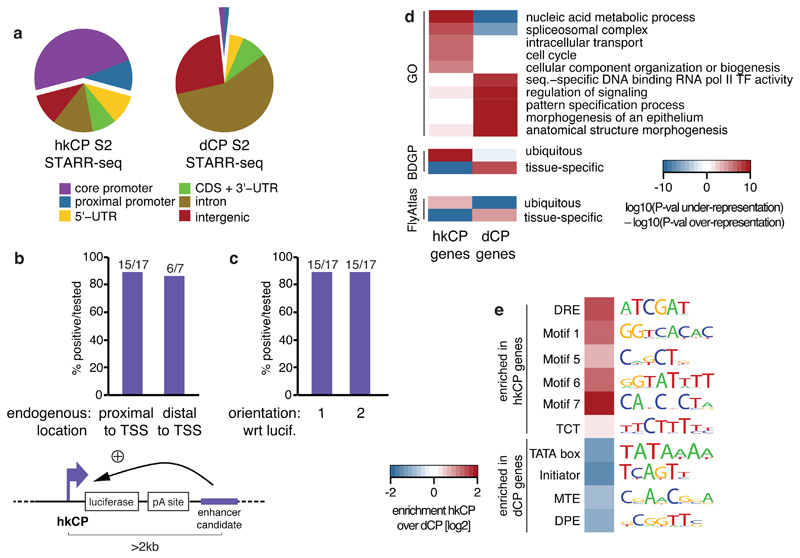

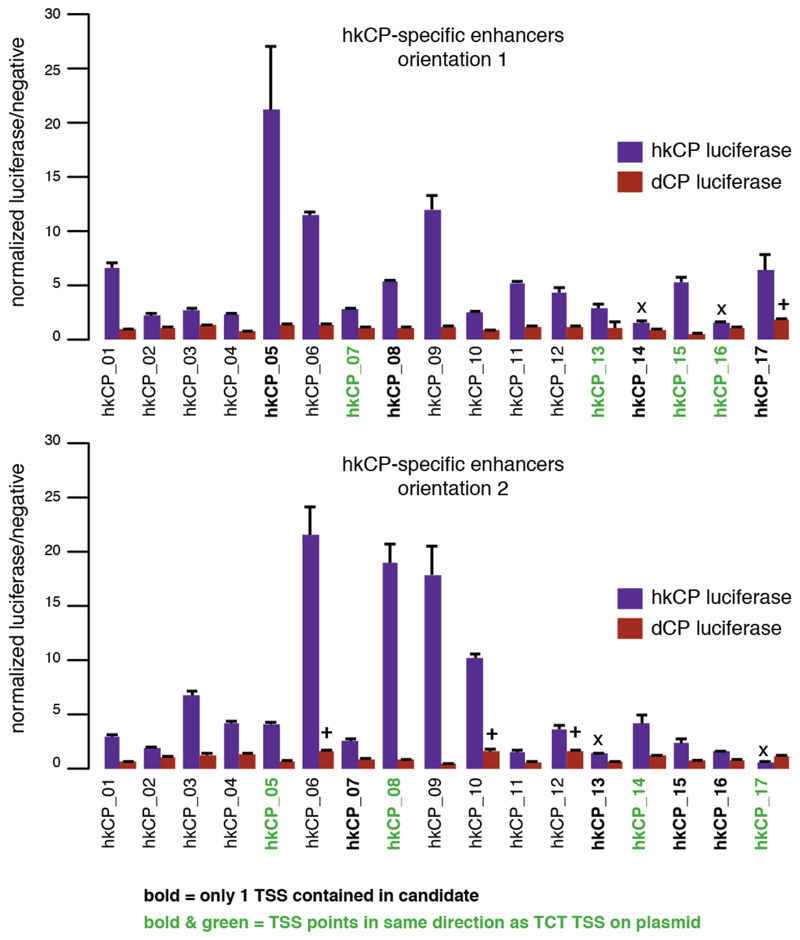

Enhancers that were specific towards either the hkCP or the dCP showed markedly different genomic distributions (Fig. 2a; Extended Data Fig. 4): while the majority (58.4%) of hkCP-specific enhancers overlapped with a TSS or was TSS-proximal (≤200bp upstream; Fig. 2a), dCP-specific enhancers located predominantly to introns (56.5%) and intergenic regions (26.9%; Fig. 2a and ref. 12). Importantly, despite the TSS-proximal location of most hkCP-specific enhancers, they activated transcription from a distal core promoter in STARR-seq (Fig. 1a; Extended Data Fig. 1a and and2). Luciferase2). Luciferase assays confirmed that they function from a distal position (>2kb from the TSS) downstream of the luciferase gene and independently of their orientation towards the luciferase TSS (Fig. 2b,c and Extended Data Figs 3 and and5).5). These results show that TSS-proximal sequences can act as bona fide enhancers14 and that developmental and housekeeping genes are both regulated through core promoters and enhancers yet that the fraction of TSS-proximal enhancers differs substantially (3.4% vs. 58.4%).

a, Genomic distribution of hkCP and dCP enhancers (CDS: coding sequence; UTR: untranslated region). b-c, hkCP enhancers function distally in luciferase assays independent of their genomic positions (b) and orientation towards the luciferase TSS (c; orientation 1 from (b); Extended Data Figs 3 and and5).5). d-e, GO (5 of the top 100 terms shown per column; Supplementary Table 11) and gene expression (terms curated from BDGP and FlyAtlas) analyses (d) and enrichment of core-promoter elements at TSSs (e) for genes next to hkCP and dCP enhancers.

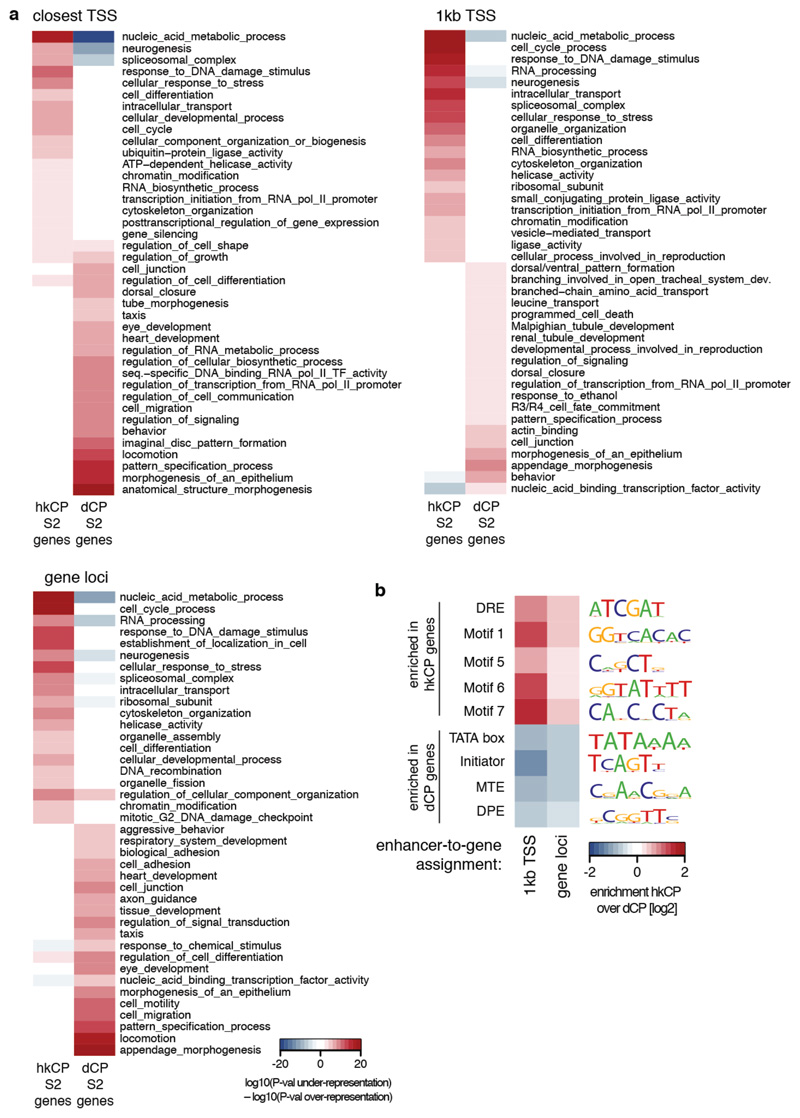

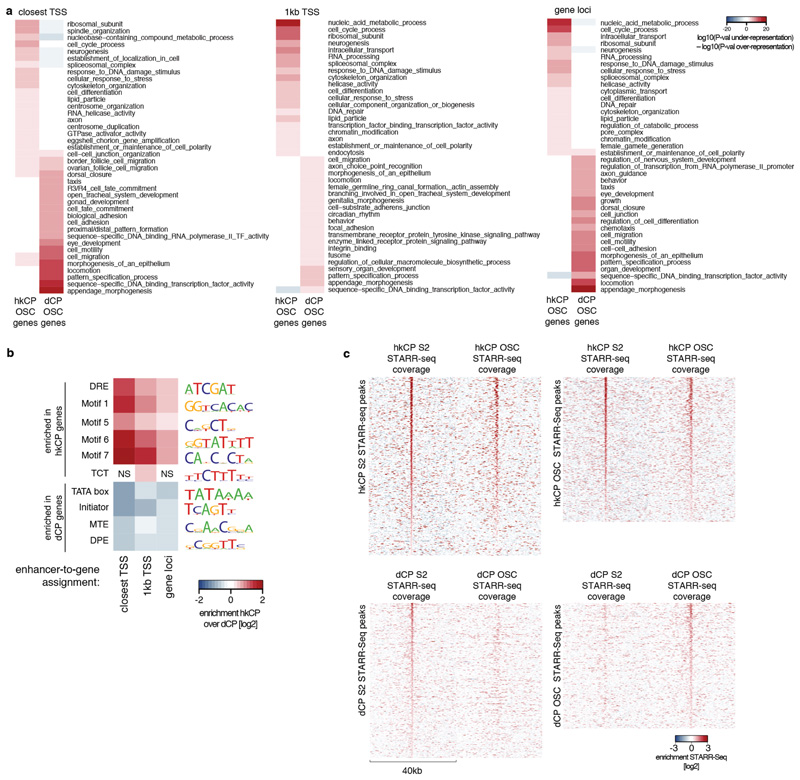

hkCP and dCP enhancers were also located next to functionally distinct classes of genes according to gene ontology (GO) analyses: genes next to hkCP enhancers were enriched in diverse housekeeping functions including metabolism, RNA processing, and cell cycle, while genes next to dCP enhancers were enriched for terms associated with developmental regulation and cell type-specific functions (Fig. 2d; Extended Data Fig. 6a and Supplementary Tables 2-4). Consistently, hkCP enhancers were preferentially near ubiquitously expressed genes and dCP enhancers near genes with tissue-specific expression (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 5).

The core promoters of the putative endogenous target genes of hkCP and dCP enhancers were also differentially enriched in known core promoter elements15 (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 6b): TSSs next to hkCP enhancers were enriched in Ohler Motifs16 1, 5, 6 and 7, consistent with the genes’ ubiquitous expression and housekeeping functions. In contrast, TSSs next to dCP enhancers were enriched in TATA, Initiator, MTE and DPE motifs, which are associated with cell type-specific gene expression7,15.

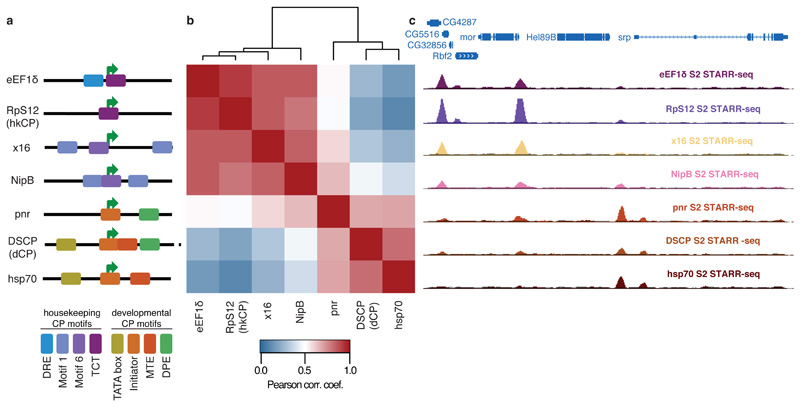

We next investigated whether the specificity that the hkCP and dCP display towards the two enhancer classes applies more generally. We selected three additional core promoters from housekeeping genes with different functions: from the eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 delta (eEF1delta), the putative splicing-factor x16, and the cohesin loader Nipped-B (NipB). Importantly, all three contained combinations of core promoter elements that differed from that of hkCP, namely TCT and DRE motifs (eEF1delta), and Ohler motifs 1 and 6 (x16 and NipB; Fig. 3a). In addition, we selected a DPE-containing core promoter of the TF pannier (pnr) and the TATA-box core promoter of Heat shock protein 70 (hsp70), which can be activated by tissue-specific enhancers (e.g. ref. 17), thus covering the two most prominent core promoter types of regulated genes9,16,18.

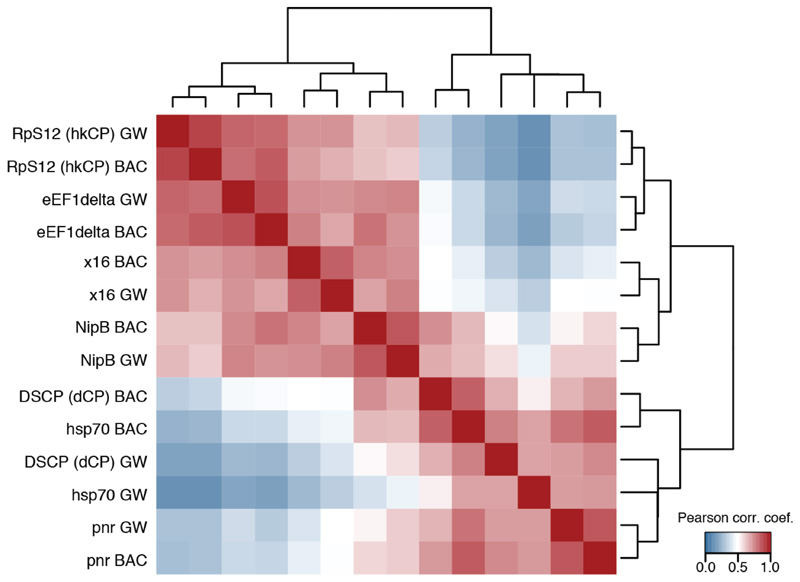

a, Different housekeeping (top 4) and developmental-like (bottom 3) core promoters and their motif content (schematic). b, Bi-clustered heatmap depicting pairwise similarities of STARR-seq signals ([PCCs] at peak summits). PCCs and dendrogram (top) show the separation between housekeeping and regulated core promoters. c, Genome browser screenshot depicting STARR-seq tracks for all 7 core promoters.

We performed STARR-seq for the five additional core promoters and grouped the genome-wide enhancer activity profiles of all seven core promoters by hierarchical clustering. This revealed two distinct clusters corresponding to the 4 housekeeping and the 3 developmental core promoters respectively (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 7 and Supplemental Tables 6 and 7), and the core promoters of both clusters indeed responded markedly differentially to individual genomic enhancers (Fig. 3c).

These results obtained for core promoters with diverse motif content and from genes with various functions suggest that the distinct enhancer preferences between hkCP and dCP apply more generally and that two broad classes of housekeeping and developmental (or regulated) core promoters exist. Differences within each class might correspond to differences in relative enhancer preferences of the core promoters2–6, while similarities between both classes could reflect enhancers that are shared (Fig. 1c-e) or core promoters that can be activated to different extents by enhancers from both classes (e.g. NipB; Fig. 3b,c). The latter might be important if broadly expressed housekeeping genes need to be further activated in specific tissues.

To test if hkCP enhancers function in different cell types, we performed STARR-seq using hkCP in ovarian somatic cells (OSCs), which differ strongly from S2 cells in gene expression and dCP enhancer activities12. Two hkCP STARR-seq replicates in OSCs were highly similar (PCC 0.97) and yielded 6,217 enhancers (Supplementary Table 1), compared to 5,774 enhancers obtained for dCP in OSCs12. The OSC data confirmed the differences between hkCP and dCP enhancers observed in S2 cells (Extended Data Figs 8 and and99 and Supplementary Tables 8-10). Strikingly, hkCP-specific enhancers in OSCs and S2 cells (3,357 and 4,137, respectively) were almost indistinguishable, while dCP-specific enhancers differed strongly between the two cell types12 and from the hkCP enhancers (Fig. 4a). The observation that hkCP showed similar activities in both cell types while dCP enhancers were cell-type specific was true genome-wide when comparing genomic locations (69% vs. 15% overlap) or enhancer strengths as measured by STARR-seq (PCC at peak summits 0.83 vs. 0.05; Fig. 4b-d and Extended Data Fig. 9c). Together, these results show that hkCP enhancers are shared between two different cell types, while dCP enhancers are cell type specific12, presumably representing ubiquitous housekeeping versus developmental and cell type-specific gene expression programs.

a, Genome browser screenshot showing tracks for hkCP (top) and dCP STARR-seq (bottom) in S2 cells and OSCs. b, Overlap of hkCP (top) and dCP (bottom) enhancers between S2 cells and OSCs. c-d, hkCP (c) and dCP (d) STARR-seq enrichments in S2 cells versus OSCs at hkCP- or dCP-specific enhancers (insets show replicates; dCP data from ref. 12).

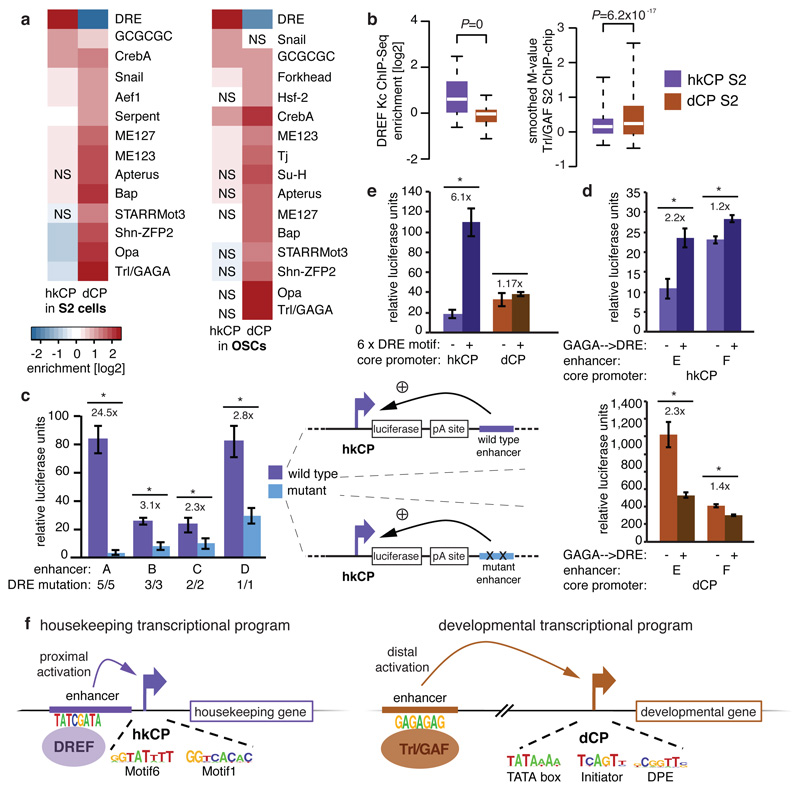

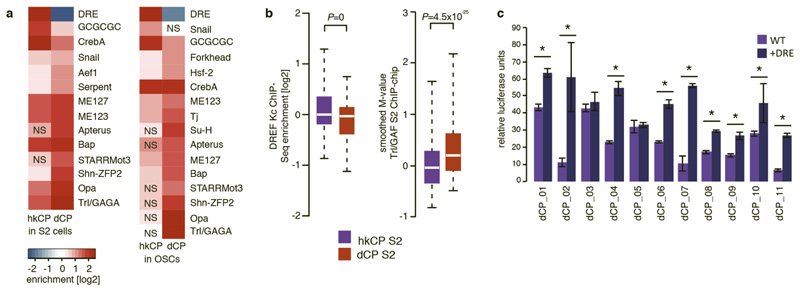

To assess if the marked core promoter specificities of the hkCP and dCP enhancers are encoded in their sequences, we analyzed the cis-regulatory motif content of both types of enhancers19. This revealed a strong enrichment of the DNA Replication-related Element (DRE) in hkCP enhancers (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Tables 11 and 12), while dCP enhancers were strongly enriched in the Trl/GAGA motif and other motifs previously described to be important for dCP enhancers20. Published genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) data21,22 confirmed that DREF (DRE-binding factor) bound significantly more strongly to hkCP enhancers than to dCP enhancers (Wilcoxon P=0; Fig. 5b), while the opposite was true for Trl/GAF (Trithorax-like/GAGA-factor; Wilcoxon P=6.2x10-17). Considering only distal enhancers (>500bp from the closest TSS) yielded the same results (Extended Data Fig. 10a and b, Supplementary Tables 13 and 14), suggesting that the differential occupancy is a property of both types of enhancers rather than a consequence of the different extents to which they overlap with TSS. Disrupting the DRE motifs in 4 different hkCP enhancers substantially reduced the enhancers’ activities as measured by luciferase assays in S2 cells (between 2.3 to 24.5-fold reduction; Fig. 5c), while dCP enhancers depend on Trl/GAGA motifs20. Adding DRE motifs to 11 different dCP enhancers significantly increased luciferase transcription from the hkCP for 9 (82%; Extended Data Fig. 10c), and changing the Trl/GAGA motifs of two dCP enhancers to DRE motifs significantly increased both enhancers’ activities towards the hkCP but decreased their activities towards the dCP (Fig. 5d). Further, an array of 6 DRE motifs was sufficient to activate luciferase transcription from the hkCP but not the dCP (Fig. 5e). Together, these results show that hkCP and dCP enhancers depend on DRE and Trl/GAGA motifs, respectively, and demonstrate that DRE motifs are required and sufficient for hkCP enhancer function.

a-b, Motif enrichment (a) and ChIP-signals for DREF and Trl/GAF (b) in hkCP and dCP enhancers (NS: not significant [FDR-corr. hypergeometric P>0.01]; boxes: median and interquartile range; whiskers: 5th and 95th percentiles; two-sided Wilcoxon-rank-sum P-values). c, Luciferase assays (LAs) for 4 wildtype and DRE-motif-mutant hkCP enhancers (numbers: mutated motifs; error-bars: s.d. [n=3]; * P<0.005 [one-sided t-test]). d, LAs for 2 dCP enhancers (-) and Trl/GAGA→DRE-mutant variants (+) with hkCP (top) and dCP (bottom; details as in c). e, LAs for 6 DRE motifs with hkCP and dCP (details as in c). f, Model: housekeeping genes contain Motifs 1,5,6,7 and/or TCT and are activated by TSS-proximal hkCP enhancers via DREF. Regulated genes contain TATA-box, Initiator, MTE and/or DPE and are activated by distal dCP enhancers via Trl/GAF.

Our results show that developmental and housekeeping gene regulation is separated genome-wide by sequence-encoded specificities of thousands of enhancers towards one of two types of core promoters, supporting the longstanding ‘enhancer-core promoter specificity’ hypothesis2–6,23. Our findings argue that these specificities are likely mediated by defined biochemical compatibilities24 between different trans-acting factors such as DREF versus Trl/GAF (at enhancers) and the different paralogs that exist for several components of the general transcription apparatus (at core promoters), presumably including the TATA box-binding protein-related factor 2 (TRF2) at housekeeping core promoters25,26. As such paralogs can have tissue-specific expression and stage-specific or promoter-selective functions27,28 (reviewed in refs. 29,30), sequence-encoded enhancer-core promoter specificities could be employed more widely to define and separate different transcriptional programs (Fig. 1f).

Methods

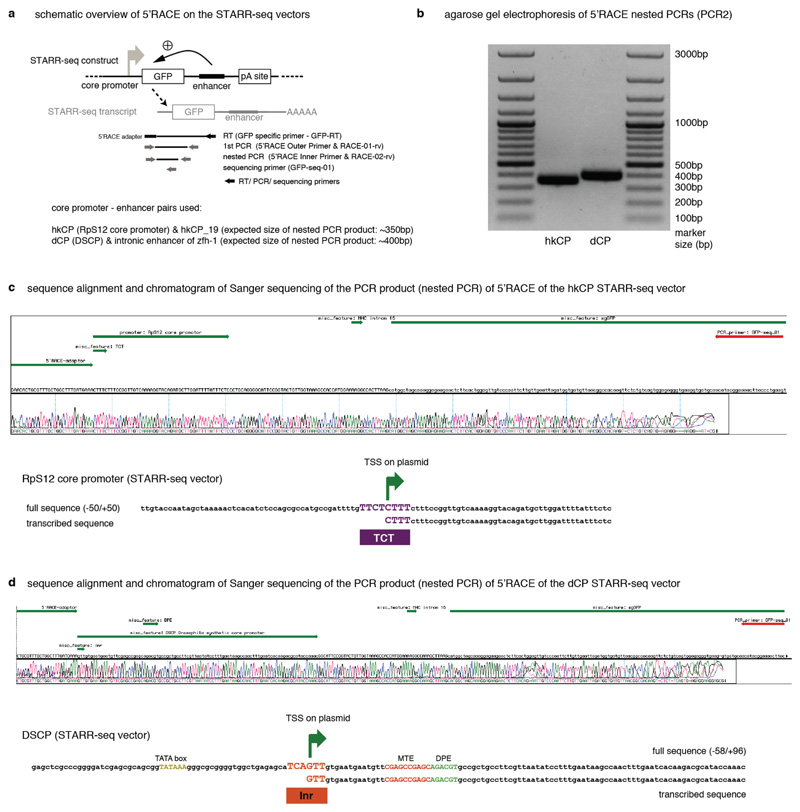

hkCP STARR-seq vector

We derived the hkCP STARR-seq vector from the original STARR-seq vector12 by replacing the DSCP sequence with the sequence of the RpS12 core promoter (-50 to +50 basepairs [bp] relative to the TSS; TTGTACCAATAGCTAAAAACTCACATCTCCAGCGCCATGCCGATTTTGTTCTCTTTCTTTCCGGTTGTCAAAAGGTACAGATGCTTGGATTTTATTTCTC). The STARR-seq vectors are available subject to a Material Transfer Agreement (MTA). For both STARR-seq vectors, we confirmed that transcription initiates from within the respective core promoters’ Initiator (DSCP) and TCT (RpS12) motifs by 5’ Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE; Extended Data Fig. 2). All other STARR-seq vectors were derived from the hkCP STARR-seq vector by replacing the 100bp sequence encompassing the RpS12 core promoter by the sequences indicated in Supplementary Table 16 using the BglII and SbfI restriction sites.

hkCP and dCP luciferase vectors

For the dCP luciferase vector, the SV40 promoter of the pGL3-Promoter Vector (Promega) was replaced by the DSCP11 and a Gateway®-cassette was inserted downstream of the luciferase gene and the SV40 polyA-signal into the AfeI restriction site, to allow Gateway® LR cloning of candidate sequences12. For the hkCP luciferase vector, the SV40 promoter and the sequence until the translation start codon of the luciferase gene was replaced by the sequence encompassing the TSS of RpS12 from -50 bp until its translation start codon.

(TTGTACCAATAGCTAAAAACTCACATCTCCAGCGCCATGCCGATTTTGTTCTCTTTCTTTCCGGTTGTCAAAAGGTACAGATGCTTGGATTTTATTTCTCCGAAATGAAGAGGTTTTCTTATCGAAAATGTAATAAATATGAACAATTAACTATCTTTTCCAGTGCAGTGCATCCTTAACCGCAGAACA). Constructs are available subject to an MTA.

Intrinsic activity of core promoters

All core promoters used in this study were cloned into the dCP luciferase vector (without the Gateway® cassette), replacing the DSCP between the BglII and SbfI restriction site with the respective core promoter. For each core promoter, the intrinsic (or basal) activity is presented as relative luciferase units, normalized to Renilla luciferase signals.

Genome-wide STARR-seq screens

STARR-seq enhancer screens using the core promoters of RpS12 (hkCP), NipB, x16, and eEF1delta (Supplementary Table 15) were performed in two biological replicates (independent transfections) per cell line as described previously12 with the following exceptions. (1) 1.6x109 S2 cells and OSCs31 were transfected per biological replicate. (2) First strand cDNA synthesis was performed in 30-60 reactions with the STARR-seq RT primer (CTCATCAATGTATCTTATCATGTCTG) as reverse transcription primer. (3) Next generation sequencing (NGS) was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 machine using multiplexing according to the manufacturer’s instructions. STARR-seq data using the DSCP (dCP STARR-seq) and hsp70 core promoters are from ref. 12, but were reanalyzed using the same pipeline as for hkCP STARR-seq.

Focused STARR-seq BAC screens

The DSCP is 137 nt long synthetic core promoter derived from the core promoter of even-skipped (eve)11. To assess the functional similarity of the DSCP, its 137 nt long wildtype counterpart from the eve locus, and a version defined identically to all other core promoter used here (-50 to +50 nt around the TSS), we performed STARR-seq screens with libraries derived from 29 different BACs containing a total of ~5MB of Drosophila melanogaster genomic DNA (Supplementary Table 16). For comparison, we also screened all other core promoters with this library. For library cloning, all BACs were grown in individual bacterial cultures and the cultures mixed equally according to measurements of their optical density (OD) prior to BAC DNA isolation to achieve an equal distribution of all BACs. BAC DNA extraction, sonication and adaptor ligation was performed as described12 and the same adaptor ligated and PCR amplified BAC DNA was used to clone all STARR-seq libraries. Per STARR-seq vector, 4 In-Fusion reactions were performed, which allowed 5 transformation reactions as described12 Each library was grown in 4 liter liquid culture (LB-medium) to an OD of 2.0-2.5. Each BAC library was screened as described above for the genome-wide screens; however, only 1x108 S2 cells were used, accounting for the less complex candidate library. Similarly, the number of reactions for all subsequent steps of the STARR-seq protocol was reduced by 4-fold.

Luciferase reporter assays

Luciferase assays were performed as described previously12 with the exception that the candidate enhancers were cloned downstream of the luciferase gene and the polyA-signal, more than 2kb away from the respective core promoter (RpS12 or DSCP). Candidate enhancers were selected manually based on different criteria to allow the systematic assessment of several aspects of this study, including enhancers that were (a) specific to one of the two different core promotes (24 hkCP and 12 dCP enhancers) or found in both screens (7 shared enhancers), (b) were located proximally (17) or distally (7) to the hkCP, and (c) were of different strengths according to STARR-seq (ranks 18 to 1044). We cloned all candidates as described12 (for their genomic coordinates and primer sequences see Supplementary Table 17), picking initially one orientation towards the luciferase TSS randomly. However, to test the influence of TSSs contained in the candidate sequences, we cloned and tested all TSS proximal candidates (hkCP_01 to hkCP_17) in both orientations using both core promoters. Candidate enhancers with DRE mutations were cloned from synthesized DNA fragments (GeneArt® Strings™; Supplementary Table 18). Candidates with DRE motifs that replace GAGA motifs were cloned similarly using synthesized DNA fragments (gBlocks®) obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT; Supplementary Table 19). We also added an array of 6xDRE motifs into the AfeI restriction site of the dCP and hkCP luciferase vectors and cloned dCP_01 – dCP_11 into the middle of the DRE motif array (using the AfeI blunt end cutter) of the hkCP luciferase vector, such that these sequences were each flanked by 3 DRE motifs (Supplementary Table 19).

Luciferase assay data analysis

For all luciferase assays, we calculated standard deviations and one-sided Student’s t-tests from 3 biological replicates (independent transfections). Core promoters have intrinsic (basal) activities that can differ between different core promoters. Therefore, when comparing enhancer activities for different core promoters, normalization to the core promoters’ intrinsic activities is required, which we assessed robustly with 3 different negative control fragments (9 biological replicates in total). For all measurements, we normalized FireFly luciferase values first to Renilla luciferase values (controlling for transfection efficiency) and then to the normalized luciferase values of the 3 negative control sequences. Candidates with a significant (P<0.05) enrichment greater than 1.5 fold over negative were considered as positive.

5’RACE of STARR-seq transcripts

To determine the exact TSS for the hkCP and dCP STARR-seq vectors we used one enhancer for each (an intergenic enhancer of TpnC41C [hkCP] for hkCP and an intronic enhancer of ZFH-1 [shared_01; from ref. 12, which we cloned with EcoRV at the position of the selection cassette used during library cloning. We transfected 3.2x107 cells with each of the constructs and isolated total RNA using the RNeasy mini prep kit (Qiagen; two columns per construct) followed by polyA+ RNA isolation using oligo-dT Dynabeads (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturers instructions. We then performed 5’RACE for both samples using the FirstChoice® RLM-RACE Kit (Ambion; cat.no. AM1700) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To reflect RNA processing of the STARR-seq pipeline, reverse transcription was however performed using SuperscriptIII (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and using GFP-RT (Supplementary Table 20) as gene specific primer (using RNA amounts according to the FirstChoice manual). The first PCR was performed with the manufacturer-provided 5' RACE Outer Primer and the transcript specific primer RACE-01-rv, using 2x KAPA Hifi Hot Start Ready Mix (98°C for 45seconds (s); followed by 35 cycles of 98°C for 15s, 69°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s) with 1ul of cDNA as template. The nested PCR was performed similarly (primer: 5' RACE Inner Primer & RACE-02-rv; 98°C for 45s; followed by 30 cycles of 98°C for 15s, 67°C for 30s, 72°C for 10s). The PCR products were visualized on a 1% agarose gel. The PCR products for both samples were Sanger sequenced using the primer GFP-seq-01 (for all primer sequences see Supplementary Table 20).

STARR-seq NGS data processing

Paired-end STARR-seq and input read processing was performed as described32. The NGS data for dCP (DSCP) and hsp70 were obtained from ref. 12 yet reanalyzed. In the same cell line, a hkCP peak is considered to be ‘specific’ if the 501 bp window centered at the peak summit does not overlap with any such window for dCP peaks, and vice versa (note that this is only applied within each cell type, such that comparisons across cell types are not influenced). For screens with the BAC-derived libraries, we considered only fragments that originated from the BACs used and determined the relative abundance of each BAC from the NGS data of the respective inputs only. Based on this, we then adjusted both inputs and STARR-seq NGS data such that all BACs were equally represented and analyzed the data as above.

Venn diagram/peak intersection

We used the same intersection method as above, and plotted the Venn diagrams with areas proportional to the number of peaks.

Scatter plots

We calculated the STARR-seq enrichment over input at the summit positions of both datasets that are to be compared, using a pseudo count of 1, and computed the log2 of corrected ratio as described12. This plots one data point for each enhancer – even for closely spaced ones – exactly at the enhancer’s summit position. For visualizing replicates, we called peaks on the merged datasets and plotted the values from both replicates at these peaks’ summits.

Enhancer-to-gene assignment

We performed three different strategies of enhancer-to-gene assignments: 1) ‘closest TSS’, an enhancer is assigned to the closest TSS of an annotated transcript 2) ‘1kb TSS’, an enhancer is assigned to all TSSs that are within 1kb, and 3) ‘gene loci’, an enhancer is assigned to a gene provided that it falls within 5kb upstream from the TSS, the gene body or 2kb downstream of the gene (multiple assigned gene are possible). In all cases we used annotation from Drosophila melanogaster Flybase release 5.50.

Genomic distribution

We assigned a unique annotation for each nucleotide in the genome by using the following priority order: coding sequence (CDS), core promoter (±50bp around TSS), 5’-UTR, 3’-UTR, first intron, intron, proximal promoter (200bp upstream of a TSS), intergenic region. We then assigned each peak to one of these categories by the annotation of the peak’s summit.

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis

We assessed whether genes assigned to hkCP or dCP enhancers were enriched for particular GO categories33, by calculating hypergeometric P-values for all categories, which we corrected for multiple comparisons (FDR-type correction in R). We then sorted all categories according to P-values of over-representation, selected the top 100 of either hkCP and dCP, and removed redundant categories manually. For each category, we calculated log10 (P-value under-representation) – log10 (P-value over-representation), and sorted the terms in a descending order of difference between hkCP and dCP values. The color intensity of the heat maps represents log10 (P-value underrepresentation) – log10 (P-value over-representation).

Gene expression analysis

We analyzed enrichment in ubiquitous versus tissue-specific gene expression sets as described for the GO analysis above. To define the gene sets based on and in situ hybridization dataset of fly embryos (BDGP34), we first removed maternal (stages 1 to 3) annotations, as well as genes with the annotation ‘no staining’ in all stages. We required each gene to have annotations for at least 3 stage groupings. We called a gene ‘tissue-specific’ if at most 1 of these annotations contains the word ‘ubiquitous’ and called it ‘ubiquitous’ if at least 60% of them contain word ‘ubiquitous’. We also defined gene sets based on microarray datasets from dissected fly tissues (FlyAtlas35). We defined genes to be ‘ubiquitous’, if their expression does not change by more than 2-fold compared to the whole fly for at least 15 out of 23 tissues. For this, we used the ratios and ‘change_direction’ calls from FlyAtlas directly and don’t consider cell lines and carcass. We similarly defined genes to be ‘tissue-specific’ if they change by more than 2-fold in at least 3 tissues. We do not consider genes with multiple conflicting entries as they can result from the use of multiple probes and removed genes that overlapped between the ‘ubiquitous’ and ‘tissue-specific’ gene sets from both sets.

TF motif and core promoter element enrichment analysis

We used previously employed position weight matrices (PWMs) for different TFs13 with a cutoff of 4-6=2.4x10-4. We selected control regions by controlling for genomic and chromosome distribution, and required that they did not overlap with any peak. We scored each motif for its enrichment in 401 bp windows centered on the peak summits by multiple testing (FDR) corrected hypergeometric P-values. We considered only motifs that showed log2 (confidence ratio of motif counts in peak windows / motif counts in random regions)>1 and P-value<0.01 in hkCP or dCP enhancers (or both) and reduced motif redundancy by removing highly similar motifs as in ref. 13 and references therein. We sorted the motifs in a descending order by difference in log2 (hkCP enrichment) - log2 (dCP enrichment). When assessing whether the observed motif distribution persisted for distal enhancers (Extended Data Fig. 10a), we kept the motifs and their order as in Fig. 5a and only re-evaluated their enrichment in distal enhancers only. The color intensity of the heat maps represents log2 (confidence ratio of motif counts in peak windows / motif counts in random regions). We used previously published nucleotide counts for TATA box, Initiator, MTE, DPE and Motifs16 1, 5, 6, 7 and the TCT element8 restricted to 8 bp and created log-odd matrices. We scanned for motif occurrences using MAST from the MEME suite36 (version 4.9.0) and parameters that ensured specificity and sensitivity for each motif (Supplementary Table 21). For assignment methods (1) and (2), we determined the presence of each core promoter element in the core promoter region of all genes uniquely assigned to either hkCP or dCP enhancers, respectively. For assignment method (3), we took the core promoter elements of the TSSs of the longest mRNA isoform. We assessed the differential distribution of each core promoter element between the core promoters assigned to hkCP or dCP enhancers by confidence ratios and hypergeometric P-values.

TF motif and core promoter element de novo discovery

We used MEME36 (version 4.9.0) to discover de novo motifs with lengths between 5 and 8 nucleotides in the enhancer regions we identified using STARR-seq and in the core promoter regions around the nearest annotated transcription starting site (TSS). We are providing all discovered motifs in Supplementary Dataset 1.

Core promoter similarity heatmap

For all pairs of core promoters, we computed pair-wise Pearson correlation coefficients (PCCs) between the respective STARR-seq fragment coverages at the summits of all peaks called in either of the two screens genome-wide. We performed hierarchical clustering (complete linkage) in R, directly using the computed PCC values as similarities.

STARR-seq enrichment heatmap

We computed the log2 of the corrected STARR-seq enrichment over input as above, yet for each nucleotide in a 20kb window around all reference peak summit positions, and down-sampled the data points 50-fold by calculating one average data point per 50 nucleotides (nts).

STARR-seq enrichment meta-profiles around transcription starting sites (TSSs)

We calculated corrected STARR-seq enrichments (log2) as for the heatmaps, yet for 20kb windows around TSSs, selected according to their core promoter motif content (see Extended Data Fig. 4 and and8),8), corrected for the TSSs’ orientation within the genomic sequence. We then calculated the average for each position along the X-axis.

Boxplot

For DREF ChIP-seq and input data obtained from ref. 21 (GSM977024 and GSM762849), we mapped the 36nts reads using bowtie37 (version 0.12.9) with the following parameters: -p 4 -q -v 3 -m 1 --best --strata –quiet. We extended the reads to 150bp, calculated the coverage for ChIP-seq and input at the STARRseq peak summit, normalized the value to the number of input fragments, added a pseudo count of 1, and computed the confidence ratio of ChIP-seq over input. For the Trl ChIP-chip data obtained from ref. 22, we used the signal of the chiparray probe at the peak summit if available or inferred the signal by linear extrapolation from the two nearest flanking probes (one on each side) provided that they were both within 10 nt of the peak summit. We calculated statistical significance via Wilcoxon’s paired rank tests.

Coordinate intersections

We performed genomic coordinate intersections using the BEDTools suite38 (version 2.17.0).

Statistics

We performed all statistical calculations and created graphical displays with R39.

Extended Data

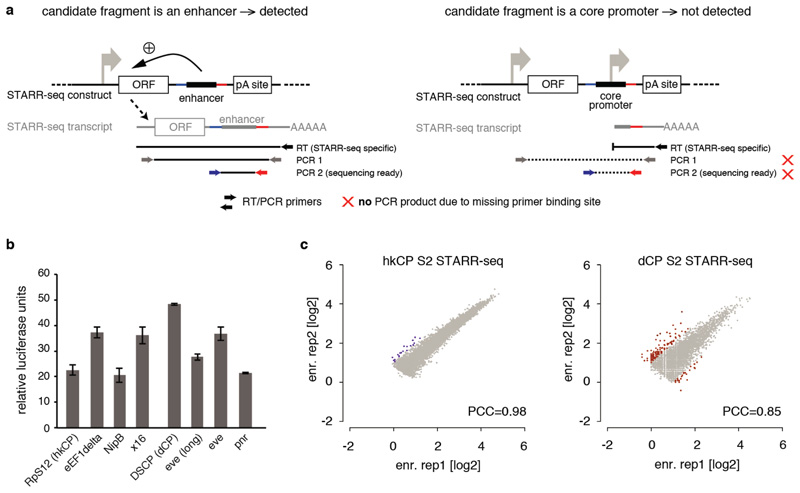

Extended Data Figure 1

a, STARR-seq detects enhancers but no promoters (after ref. 12). (Left) STARR-seq couples the enhancer activities of candidate fragments to the candidates’ sequences in cis by placing the candidates to a position within the reporter transcript. Enhancer activities can therefore be assessed by the presence of candidates among cellular mRNAs, which allows the parallel assessment of millions of candidates, enabling genome-wide screens. Sequences that activate transcription from the intended core promoter of the STARR-seq vector lead to a full-length reporter transcript and can be detected by STARR-seq. Shown are the RT and nested PCR steps of the STARR-seq reporter RNA processing protocol that ensure this. (Right) In contrast, STARR-seq does not detect truncated transcripts that result if a candidate fragment functions as a promoter to initiate transcription. Thus, core promoter-containing (i.e. TSS-overlapping) sequences that are detected by STARR-seq exhibit enhancer activity as they can activate transcription from a remote position, in addition to their ability to serve as core promoter endogenously12. b, Luciferase signals (Firefly/Renilla) assessing the intrinsic (or basal) activity of the core promoters used in this study in luciferase reporter setups that differ only in the respective core promoter sequences and do not contain any enhancer. The basal activities differ as expected, but do not differ consistently between housekeeping (RpS12, eEF1delta, NipB, x16) and developmental (DSCP, eve[long], eve and pnr) core promoters, nor between core promoters for which the STARR-seq screens appear most similar (e.g. RpS12 and eEF1delta; see Figure 3). Note that all luciferase assays and STARR-seq screens are corrected for differences in intrinsic activity. c, Reproducibility of hkCP and dCP STARR-seq in D. melanogaster S2 cells. The reproducibility of hkCP and dCP STARR-seq as assessed by the STARR-seq enrichments (replicate 1 vs. 2) at the summits of enhancer peaks called in the merged experiments (hkCP: 5,956; dCP: 5,408; scatter plots are enlarged versions of the insets in Figure 1d; PCC: Pearson correlation coefficient; enr. rep X: STARR-seq enrichment in replicate X). Note that the data for dCP are from ref. 12, but have been re-analyzed.

Extended Data Figure 2

5’ Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (5’ RACE) demonstrates that transcription initiates at the TCT and Initiator motifs within the hkCP and dCP, respectively. a, Setup of the 5’RACE experiment including the STARR-seq plasmid, used here with two defined enhancers, the STARR-seq transcript and location of all primers used to specifically amplify 5’-capped STARR-seq transcripts. b, 5’ RACE nested PCR products separated on a 1% agarose gel. c, Screenshot of Sanger sequencing results (chromatogram and called bases) compared with the template sequence. Annotations are shown in green, in the following order: 5’ RACE adapter, hkCP with TCT motif (only the part downstream of the transcription start is annotated, as the 5’ part is not present in the sequenced cDNA), spliced intron, GFP; the sequencing primer is shown in red (top). Also shown is a version that displays the template and Sanger sequencing results for the core promoter region only (zoom in). d, same as in (c) but for the dCP for which transcription initiates within the Initiator (Inr) motif.

Extended Data Figure 3

a, Luciferase reporter setup with the hkCP or dCP (see also Figure 1e). b, Luciferase signals of 24 hkCP-specific enhancers tested in a hkCP- (purple bars) as well as in a dCP-containing (brown bars) luciferase reporter. 21 out of 24 hkCP enhancers showed luciferase activity (>1.5 fold over negative, P<0.05 via one-sided unpaired Student’s t-test, n=3) with the hkCP, while only 1 out of 24 showed activity with the dCP (error bars are s.d. of three biological replicates, ‘x’ flags candidates that are not active with the correct core promoter, and ‘+’ flags candidates for which the activity with the wrong core promoter is above the threshold (note that the activity with the correct core promoter is still higher in all 3 cases). c, as in (b) but testing dCP-specific enhancers. 10 out of 12 are positive with the dCP while only 2 out of 12 are positive with the hkCP. d, as in (b and c) but testing shared enhancers that were found by STARR-seq with hkCP and dCP; 6 out of 7 are active with both core promoters. See Supplementary Table 17 for the genomic coordinates of the enhancers and the primers used to amplify them.

Extended Data Figure 4

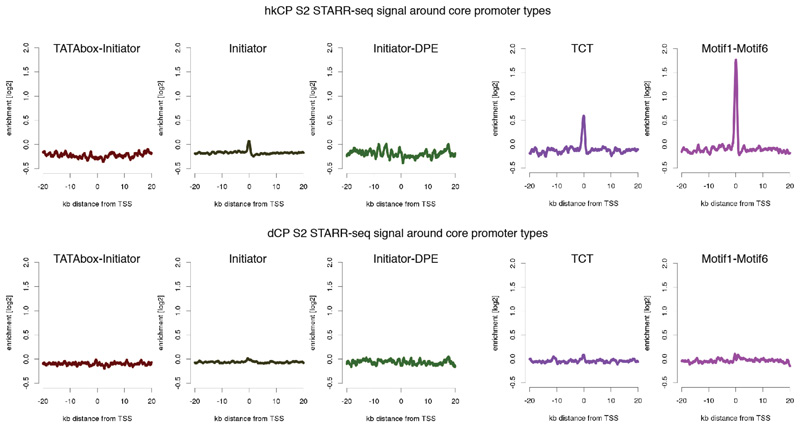

Average hkCP (top) and dCP (bottom) S2 STARR-seq enrichment in 40kb intervals around transcription starting sites (TSS) that contain different combinations of known core promoter motifs. Shown are (left to right) TATA-Initiator (179 TSSs), Initiator (that do not contain either TATA or DPE; 1901), Initiator-DPE (100), TCT (303) and Motif1-Motif6 (266). According to their motif contents, the first 3 are developmental-type core promoters and the last 2 are housekeeping-type core promoters. Indeed, only the housekeeping-type core promoters show a strong enrichment of hkCP S2 STARR-seq signals at the TSS, which is not seen for the dCP STARR-seq signal (due to enhancer–core promoter specificity) nor for the developmental-type core promoters (due to the dCP enhancers location at more distal sites).

Extended Data Figure 5

Luciferase signals for all 17 TSS-overlapping hkCP enhancers (i.e. containing 1 TSS or 2 divergent TSSs; see Supplementary Table 17) from Extended Data Figure 3 cloned in the second orientation with respect to the TSS of the luciferase gene (lower bar plot; the upper bar plot corresponds to the initial orientation as in Extended Data Figure 3 and is shown for comparison). In both orientations, 15 out of 17 enhancers showed activity towards the hkCP (details as in Extended Data Figure 3). These results together with the findings in Extended Data Figure 3 challenge the widespread notion that TSS-proximal sequences are promoters and even the concept of promoters more generally: sequences that autonomously activate gene expression – and are therefore often termed promoters – might in fact be the combination of a core promoter and a proximal enhancer. The TSS-proximal location of many housekeeping enhancers might be evolutionarily more ancient, consistent with regulatory mechanisms in simple eukaryotes such as yeast. In contrast, enhancers of genes with more complex regulation are typically located more distally, potentially simply because the several different cell type-specific enhancers of these genes would not all fit to positions near TSSs. Consistently, such genes frequently have larger intergenic and intragenic regions40 known to accommodate enhancers with diverse activity patterns41.

Extended Data Figure 6

a, Gene ontology (GO) analysis of genes next to hkCP and dCP-specific enhancers in S2 cells using different enhancer-to-gene assignment strategies (top-left: ‘closest TSS’ as in Figure 2, top-right: ‘1kb TSS’, bottom-left: ‘gene loci’; see Methods for details). Shown are 20 non-redundant GO categories selected from the 100 most significantly enriched categories associated with each enhancer class (see Supplementary Tables 11-13 for all categories). b, Enrichment of core promoter elements at genes next to hkCP and dCP-specific enhancers in S2 cells. Similar analysis as in Figure 2e, however using different enhancer-to-gene assignment strategies (see Methods for details). Consistent with Figure 2e, core promoters of genes assigned to hkCP-specific enhancers are enriched in Motifs 1, 5, 6, 7 and DRE, while core promoters of genes assigned to dCP-specific enhancers are enriched for TATA box, Initiator, MTE and DPE motifs, irrespective of the assignment strategy.

Extended Data Figure 7

As Figure 3b yet including biological replicates with an independently cloned BAC library covering around 5MB of genomic sequence (BAC) and assessing the Pearson correlation coefficient at each position along these regions (GW: genome-wide screens as in Figure 3b). The similarity observed for the TATA box and DPE containing core promoters (hsp70, pnr, and DSCP [dCP]) suggest that differences related to these core promoter elements might be more subtle or related to alternative mechanisms, including the potential preferences of more proximal or distal enhancers42 or Polymerase RNA polymerase II pausing and the dynamics versus stochasticity of initiation and elongation43,44,45.

Extended Data Figure 8

a-b, Different enhancers activate transcription from hkCP and dCP in OSCs. As Figures 1c and d but for OSCs rather than S2 cells. c, Genomic distribution of hkCP and dCP enhancers in OSCs. As Figure 2a but for OSCs rather than S2 cells. d, hkCP and dCP STARR-seq signal in OSCs around different core promoter types. As Extendend Data Figure 4 but for OSCs rather than S2 cells.

Extended Data Figure 9

a, Gene ontology (GO) analysis of genes next to hkCP and dCP-specific enhancers in OSCs. As Extended Data Figure 6a but for OSCs rather than S2 cells (see Supplementary Tables 15-17 for all categories). b, Enrichment of core promoter elements at genes next to hkCP and dCP-specific enhancers in OSCs. As Figure 2e and Extended Data Figure 6b but for OSCs rather than S2 cells (NS: non-significant [hypergeometric P>0.05]). c, Heat maps of hkCP (top) and dCP (bottom) STARR-seq enrichments in S2 cells and OSCs. Heat maps on the left and right are centered on the summits of core-promoter type-specific enhancers in S2 and OSCs, respectively.

Extended Data Figure 10

a, Differential motif enrichment in distally located hkCP and dCP-specific enhancers (as Fig. 5a but assessing enrichments of the same motif PWMs exclusively at distal enhancers >500bp away from the closest TSSs). Key motifs including DRE and Trl/GAGA are also differentially enriched in distal hkCP and dCP-specific enhancers (NS: non-significant [FDR-corrected hypergeometric P>0.01]; S2 cells: hkCP n=790, dCP n=3013; OSCs: hkCP n=556, dCP n=2555). b, Distal hkCP and dCP-specific enhancers are differentially bound by DREF and Trl/GAF, respectively. ChIP enrichments of DREF (left) and Trl/GAF (right) at S2 hkCP and dCP-specific enhancers that are distal (>500bp) from the closest TSSs. Equivalent to Figure 5b, but considering exclusively TSS-distal enhancers to exclude potentially confounding effects for TSS-proximal enhancers for which it is not possible to discern whether binding occurs due to the enhancer sequence or core promoter function. The differential binding between DREF and Trl/GAF to hkCP and dCP-specific enhancers respectively is also found in Kc cells, in which the DREF ChIP-seq experiment had been performed (data not shown). c, Addition of DRE motifs to dCP enhancers increases their activity towards hkCP. Relative luciferase activity values (Firefly/Renilla [FF/RL]) for 11 dCP enhancers without DRE motifs (WT, light purple) and with 3 DRE motifs flanking the enhancers on each side (+DRE, dark purple). Asterisks (*) indicate statistical significance (P<0.05 via one-sided unpaired Student’s t-test); error bars denote the s.d. of three biological replicates.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper.

Supplementary table legends

Supplementary tables

Acknowledgements

We thank Luisa Cochella and Oliver Bell for comments on the manuscript. Deep sequencing was performed at the CSF Next-Generation Sequencing Unit (http://csf.ac.at). M.A.Z. was supported by Austrian Science Fund (FWF, F4303-B09) and C.D.A., K.S., M.R., and O.F. by a European Research Council (ERC) Starting Grant (no. 242922) awarded to A.S. Basic research at the IMP is supported by Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH.

Footnotes

Author Contributions. M.A.Z., C.D.A. and A.S. conceived the project. C.D.A., K.S., M.P., M.R. and O.F. performed the experiments and M.A.Z. the computational analyses. M.A.Z., C.D.A. and A.S. wrote the manuscript.

Author Information. All deep sequencing data are available at www.starklab.org and are deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database under the accession numbers GSE40739 and GSE57876. Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. Readers are welcome to comment the online version of the paper.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13994

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc6795551?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1038/nature13994

Article citations

Large-scale analysis of the integration of enhancer-enhancer signals by promoters.

Elife, 12:RP91994, 28 Oct 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 39466837 | PMCID: PMC11517252

Developmental and housekeeping transcriptional programs display distinct modes of enhancer-enhancer cooperativity in Drosophila.

Nat Commun, 15(1):8584, 03 Oct 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 39362902 | PMCID: PMC11450171

A community effort to optimize sequence-based deep learning models of gene regulation.

Nat Biotechnol, 11 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39394483

Transcriptional repression and enhancer decommissioning silence cell cycle genes in postmitotic tissues.

G3 (Bethesda), 14(10):jkae203, 01 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39171889 | PMCID: PMC11457063

RNA polymerases reshape chromatin architecture and couple transcription on individual fibers.

Mol Cell, 84(17):3209-3222.e5, 26 Aug 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 39191261

Go to all (263) article citations

Other citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

GEO - Gene Expression Omnibus (2)

- (1 citation) GEO - GSE40739

- (1 citation) GEO - GSE57876

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Developmental and housekeeping transcriptional programs display distinct modes of enhancer-enhancer cooperativity in Drosophila.

Nat Commun, 15(1):8584, 03 Oct 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 39362902 | PMCID: PMC11450171

Enhancer trafficking: free throws and three-pointers.

Dev Cell, 32(2):135-137, 01 Jan 2015

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 25625204

Enhancers: holding out for the right promoter.

Curr Biol, 25(7):R290-3, 01 Mar 2015

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 25829016 | PMCID: PMC4824198

Regulatory Enhancer-Core-Promoter Communication via Transcription Factors and Cofactors.

Trends Genet, 32(12):801-814, 02 Nov 2016

Cited by: 106 articles | PMID: 27816209 | PMCID: PMC6795546

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Austrian Science Fund FWF (2)

RNA Biology

Univ.Prof. Dr. Andrea BARTA, Medical University of Vienna

Grant ID: W 1207

Unbiased identification of the RNAome and its regulation in the Drosophila female germline

Dr Alexander Stark, IMP - Research Institute of Molecular Pathology

Grant ID: F 4303

European Research Council (1)

Regulatory Genomics in Drosophila (Regulatory Genomics)

Dr Alexander Stark, Research Institute of Molecular Pathology GmbH - Vienna

Grant ID: 242922