Abstract

Free full text

Pharmacometric Models for Characterizing the Pharmacokinetics of Orally Inhaled Drugs

Abstract

During the last decades, the importance of modeling and simulation in clinical drug development, with the goal to qualitatively and quantitatively assess and understand mechanisms of pharmacokinetic processes, has strongly increased. However, this increase could not equally be observed for orally inhaled drugs. The objectives of this review are to understand the reasons for this gap and to demonstrate the opportunities that mathematical modeling of pharmacokinetics of orally inhaled drugs offers. To achieve these objectives, this review (i) discusses pulmonary physiological processes and their impact on the pharmacokinetics after drug inhalation, (ii) provides a comprehensive overview of published pharmacokinetic models, (iii) categorizes these models into physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) and (clinical data-derived) empirical models, (iv) explores both their (mechanistic) plausibility, and (v) addresses critical aspects of different pharmacometric approaches pertinent for drug inhalation. In summary, pulmonary deposition, dissolution, and absorption are highly complex processes and may represent the major challenge for modeling and simulation of PK after oral drug inhalation. Challenges in relating systemic pharmacokinetics with pulmonary efficacy may be another factor contributing to the limited number of existing pharmacokinetic models for orally inhaled drugs. Investigations comprising in vitro experiments, clinical studies, and more sophisticated mathematical approaches are considered to be necessary for elucidating these highly complex pulmonary processes. With this additional knowledge, the PBPK approach might gain additional attractiveness. Currently, (semi-)mechanistic modeling offers an alternative to generate and investigate hypotheses and to more mechanistically understand the pulmonary and systemic pharmacokinetics after oral drug inhalation including the impact of pulmonary diseases.

INTRODUCTION

The role of mathematical modeling to assess and understand pharmacokinetics (PK) in clinical drug development and therapeutic use has gained more recognition and importance over the last decades (1–3). However, the number of models characterizing the systemic and pulmonary PK of orally inhaled drugs is limited compared with other routes of administration, e.g., intravenous (IV) or oral. To understand the reasons for this gap and to demonstrate the opportunities that mathematical modeling of PK of inhaled drugs offers, this review provides a comprehensive overview of published PK models, categorizes the PK models into physiologically based PK (PBPK; PK parameters derived from physico-chemical characteristics of the inhaled drug and physiological characteristics) and empirical models (PK parameters estimated based on clinical data), and explores their (mechanistic) plausibility. To achieve these aims, firstly relevant physiological and anatomical characteristics of the lung as well as mechanistic aspects of oral drug inhalation were summarized. Secondly, a comprehensive literature review for modeling approaches describing the pulmonary and systemic PK after inhalation was performed; pulmonary PK refers to lung-specific kinetics before drug is being absorbed into the systemic circulation, such as pulmonary dissolution and pulmonary absorption, or mucociliary clearance, whereas systemic PK refers to the PK processes after drug is absorbed from the lung into the systemic circulation. Throughout this review, a clear distinction is made between PBPK models (often called bottom-up approach) and empirical PK models (often called top-down approach). Finally, the reviewed PK models were systematically evaluated in the context of physiological plausibility and critical issues pertinent to drug inhalation were discussed. It should be noted that this article and a recently published book chapter by Kandala and Hochhaus on “applied pharmacometrics in pulmonary diseases” (4) partially overlap in their scopes but overall can be considered complementary. The book chapter focuses on specific examples in pharmacokinetics and also expands to (systemic) pharmacodynamics (PD) after drug inhalation. This review article gives a comprehensive overview and categorization of published pharmacokinetic models after drug inhalation and does not include any pharmacodynamics.

The Lung As Target for Drug Administration

The lung is the organ that represents the barrier between air and blood. During oral inhalation, air is passing through the mouth, throat (oropharyngeal region), and subsequently the conducting airways until air is available for gas exchange in the alveolar space. The (conducting) airways can be differentiated into central and peripheral airways or characterized with specific airway generation numbers. Delivering drugs directly to the lung is utilized to either administer drugs to achieve efficacy by distribution to the target via systemic circulation or more frequently for local treatment of pulmonary diseases, such as asthma bronchiale or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (5, 6). When a drug is inhaled with the focus of local treatment, unbound pulmonary and systemic drug concentrations are associated with efficacy and systemic safety, respectively; thus, the goal is to maximize pulmonary and to minimize systemic (unbound) drug concentrations (7). To achieve the same pulmonary drug concentrations after IV or oral drug administration, higher oral and IV doses would typically be required compared with inhalation. Higher oral and IV doses, however, would result in higher plasma concentrations associated with a higher probability of systemic adverse drug reactions (8, 9), since drug deposited in the lung is typically not instantaneously absorbed to systemic circulation. Hence, for drugs without instantaneous pulmonary absorption, oral drug inhalation typically results in a favorable benefit/(systemic) risk ratio (10).

In contrast, when the purpose of drug inhalation is systemic treatment, plasma drug concentrations are associated with both efficacy and safety. Nonetheless, pulmonary drug concentrations might be important to evaluate pulmonary adverse drug reactions, e.g., for inhaled insulin (11).

Inhalation and Pulmonary Pharmacokinetic Processes

To understand both the pulmonary and the systemic PK after drug inhalation, a thorough understanding of the different (PK) processes in the lung is crucial. When a drug is inhaled, only a certain fraction of the dose will reach the target site in the lung. Further fractions will be deposited in the inhalation device or the mouth–throat region. From the latter, deposited particles may subsequently be swallowed and absorbed in the GI tract, leading to potential parallel absorption processes to the systemic circulation (Fig. 1).

Schematic representation of kinetic processes after drug inhalation. The three regions oropharyngeal, conducting airways, and alveolar space are kinetically distinct. Orange boxes, particle/droplet deposition compartments; light blue boxes, absorption compartments; red boxes, blood/plasma compartments; green area, processes associated with pulmonary PK; blue area, processes associated with the systemic PK. Here, the pulmonary absorption is represented as two-step absorption to the tissue, followed by absorption to systemic compartments; however, this process is often represented as a single step

After being deposited in the lung drug particles have to dissolve, before pulmonary absorption into the systemic/pulmonary circulation can take place. Besides absorption of dissolved drug, two competing pulmonary drug clearance processes may need consideration: pulmonary (metabolic) clearance, and pulmonary clearance processes consisting of mucociliary and macrophage clearance (12). Pulmonary dissolution, pulmonary absorption, and the lung-specific clearance processes (mucociliary and macrophage clearance) will be illustrated in the following sections and schematically in Fig. 1.

Pulmonary Drug Dissolution

Before absorption through the pulmonary epithelia can take place, inhaled drug particles that have been deposited in the conducting airways or the alveolar space of the lung have to dissolve in the pulmonary surface lining fluids. Pulmonary dissolution will be dependent on various drug (formulation) and physiological characteristics, e.g., lipophilicity or surface area of the inhaled drug/drug formulation, solubility of the drug in the airway lining fluids, and their volume and composition. Qualitatively and quantitatively, different compositions and volumes of the alveolar and the conducting airway lining fluids, as well as a thin fluid layer in the alveolar space (and in the peripheral conducting airways of the lung) might reason different dissolution characteristics dependent on where drug particles are deposited. However, it remains to be elucidated whether drug dissolution is faster in the peripheal or the central parts of the lung (13). Up to date quantitative characterization of the in vivo interplay of all contributing factors either with in vitro assays or with in silico methods is difficult. Especially for lipophilic drugs, pulmonary dissolution can represent the rate-limiting process and systemic exposure after drug inhalation is discussed to depend on the pulmonary drug dissolution characteristics (see below). A book chapter by Olsson et al. provides an excellent overview on pulmonary dissolution processes (13).

Pulmonary Absorption of Dissolved Drug

Drug inhalation is widely associated in literature with fast absorption of dissolved drug (14, 15). However, this often made association does not represent a generally applicable assumption. It is discussed that multiple absorption processes with different absorption rates might better represent pulmonary drug absorption. These absorption rates might differ for drug particles/droplets in different areas of the lung, e.g., between the alveolar space and the conducting airways. In the conducting airways, absorption of dissolved drug is often assumed to be slower compared with the alveolar space, due to less perfusion (16) and thicker airway walls (17). Conversely, absorption of dissolved drug in the alveolar space is often assumed to be fast due to a high local perfusion, a large absorption surface area (100 m2), and a thin diffusion barrier (12). In vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo animal assays have provided evidence for the proposed faster drug absorption in the alveolar space (18–20) compared with conducting airways.

Pulmonary Mucociliary/Macrophage Clearance

Drug clearance of drug particles/droplets from the lung depends on whether particles are deposited in the central or in the peripheral part of the lung as mucociliary clearance in the conducting airways is faster compared with the slow macrophage clearance (21, 22) in the alveolar space (23). In addition, particles deposited in the central conducting airways are cleared faster than particles deposited in the peripheral conducting airways, as mucociliary clearance increases from peripheral (small bronchi) to central conducting airways (trachea). Mucociliary clearance clears particles in these airways to the mouth–throat region, where drug may subsequently be swallowed and absorbed from the GI tract (24). These pulmonary clearance processes are more relevant for undissolved drug particles (25), i.e., slowly dissolving drug formulations will be more susceptible than rapidly dissolving formulations or solutions. Consequently, the mucociliary clearance reduces pulmonary bioavailability of inhaled drugs. If oral bioavailability is lower compared with pulmonary bioavailability, mucociliary clearance also reduces the total bioavailability of inhaled drugs.

Pulmonary Particle/Droplet Deposition Patterns

The pulmonary deposition patterns describe the drug particle/droplet deposition in different areas of the lung (e.g., more pronounced drug deposition in the peripheral parts of the lungs or on a more detailed level more pronounced drug deposition in the alveolar space of the lungs) and might depend on multiple factors (see below). As outlined, these pulmonary particle deposition patterns are assumed to be relevant for both the pulmonary and systemic PK of inhaled drugs. Technological (e.g., formulation, device characteristics) and physiological aspects (e.g., airway geometry) as well as breathing patterns have been demonstrated to influence the deposition patterns and to be relevant for the PK of inhaled drugs; e.g., a larger aerodynamic particle diameter increases both the fraction deposited in the mouth–throat region and the fraction deposited in the central conducting airways (26). A more detailed review on the influence of particle size and the physical background on particle deposition has recently been published by Isaacs et al. (27); other technological aspects, e.g., the effect of drug formulations or different inhalers on pulmonary deposition, were reviewed by Labiris and Dolovich (28). Patient-specific factors such as age (29, 30), height (30), and sex (31) have also been demonstrated to influence particle deposition patterns and/or the PK after drug inhalation. Airway diseases (e.g., asthma bronchiale or COPD) and even different disease stages altered the particle deposition patterns (32): The total bioavailability of fluticasone propionate (33–35) was decreased in patients with more severe asthma bronchiale and COPD. Similarly, maximum plasma concentrations and the exposure were decreased for inhaled fluticasone propionate and budesonide after provoking bronchoconstriction (decreased forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)) in asthma patients (36). It was discussed that narrowed airways in patients (or after bronchoprovocation) would cause a more central pulmonary particle deposition compared with healthy volunteers (or before bronchoconstriction) and in combination with the more efficient mucociliary clearance in these central parts of the lung (see above) would result in a more efficient drug removal from the lungs. Finally, the handling of an inhalation device by the patient or even the capability of a patient to use the inhaler correctly (e.g., if reduced inhalation flow) and to hold the breath for a sufficient time span may impact the pulmonary deposition (37).

Even though the impact of technological, (patho-)physiological, and/or administration aspects on the (pulmonary) PK are qualitatively described in literature, a wide knowledge gap regarding the quantitative description of these relations remains. In particular, quantitative relationships between the pulmonary particle deposition patterns, the pulmonary absorption processes, and the drug clearance from the lung are (yet) lacking. Application of mathematical modeling approaches may offer opportunities for closing this knowledge gap.

COMPREHENSIVE OVERVIEW ON MODELING APPROACHES FOR INHALED DRUGS

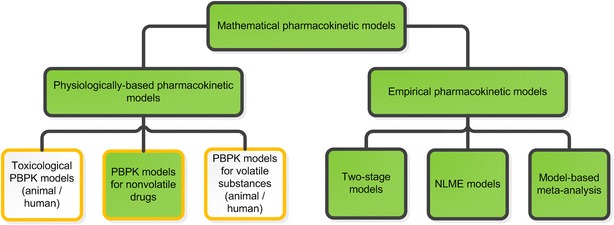

Published modeling approaches describing the systemic (and pulmonary) PK of orally inhaled drugs can be categorized into two main groups: On the one hand, PBPK approaches, for which PK parameters are not estimated based on clinical data but derived from physico-chemical characteristics of the inhaled drug and on anatomical/physiological characteristics. On the other hand, data-derived empirical PK approaches, for which PK parameters were estimated based on clinical PK data. Even if an empirical model contains a physiology-motivated model structure, these approaches will be referred to as empirical approaches, if all PK parameters were estimated based on clinical data. Both approaches can be further divided into several subcategories (Fig. 2). PK models, which cannot be categorized based on the above-described procedure, are considered as semi-empirical models.

Classification of mathematical PK models describing the pulmonary or systemic PK after substance/drug inhalation and model characteristics. Black boxes describe the type of mathematical approach; whereas orange boxes illustrate different aspects of the PK models. The filled boxes are further described and discussed in this review. NLME nonlinear mixed-effects, PBPK physiologically based pharmacokinetic, PK pharmacokinetic

Technical Background of PBPK Models

PBPK modeling is a mechanistic approach for predicting concentration-time profiles derived from the pulmonary PK (e.g., dissolution, absorption) and the systemic PK characteristics (e.g., distribution, excretion) by incorporating various anatomical and physiological aspects (e.g., organ perfusion rates or absorption surface areas) and drug/formulation characteristics (e.g., solubility, pKa values, partition coefficients, dissolution rates). In principle, a PBPK model is developed based on these predefined parameters without clinical data (bottom-up). To increase credibility and evaluate the descriptive performance of the PK model, an iterative process (learning and confirming) with predicting of and comparing with clinical data is recommended (38). PBPK models are often complex as they constitute a large system of (ordinary) differential equations containing all prior information and relevant mass transfer processes on a very detailed level (39).

Technical Background of Empirical (Data-Derived) Models

Compared with the PBPK approach, the empirical approach relies less on anatomical and physiological information but largely on clinical data (top-down). Pharmacostatistical methods and plausibility grounds (e.g., different pulmonary absorption rates based on physiological characteristics of the lung, see above) are determinants for developing a compartmental model that best describes the data. Empirical models are often less complex than PBPK models, typically have less mechanistic rationale and their PK parameters might be more difficult to interpret. Nonetheless, empirical models might also have a semi-mechanistic character, if prior information of the body (“system”) or parts are included. Empirical modeling can be used to quantify the impact of individual characteristics (covariates) on PK parameters. Model evaluation may be performed with clinical data used for model building (internal evaluation) or additional clinical data (external evaluation) (40).

Two different empirical population data analysis approaches, the two-stage approach and the nonlinear mixed-effects modeling (NLME) approach, have been used to describe the PK after drug inhalation. In the two-stage approach, the PK model parameters are first estimated for each individual separately. In the second stage, summary statistics of the individual PK parameter estimates are calculated (40). In the NLME approach, all data is simultaneously analyzed, i.e., all population parameters including interindividual variability in these parameters are estimated in one step (40). Aside from these approaches, compartmental models have been reported being fitted to average plasma concentration-time profiles extracted from literature (model-based meta-analysis) (41, 42). Non-compartmental approaches will not be addressed in this review.

Comprehensive Overview on PBPK Models

Published PBPK models describing the systemic/pulmonary PK after inhalation of vapors were mostly used to assess the PK of inhaled anesthetics and other volatile substances (e.g., inhaled diacetyl (43)). A review about those PBPK models was published by Morris (44); underlying assumptions were homogeneous drug concentrations in the air and passive inhalation. However, these do not hold true for drug administration via an inhalation device representing an inhalation process with non-constant inhalation flow and non-uniform drug concentration in the inhaled air. Hence, these aspects should be considered in PBPK models of inhaled drug aerosols/powders. Compared with the “vast mathematical descriptions of inhaled vapor disposition” (44), fewer PBPK models describing the human PK of orally inhaled drugs administered with an inhalation device have been published. These PBPK approaches will be reviewed in the following chapter categorized as drug-specific and generic (adaptable) approaches.

Drug-Specific PBPK Models

Gaz et al. published a theoretical study (not based on or evaluated with clinical PK data), in which a PBPK model was developed for predicting both the PK and PD of an inhaled bronchodilator (45). The nominal dose was divided into three fractions representing drug that was deposited inside the spacer/inhalation device, in the mouth–throat region, and in the lung. The absorption process of the drug subsequently swallowed from the mouth–throat region was modeled as a separate absorption process from the GI tract into the systemic circulation. The pulmonary fraction was further differentiated into 17 fractions representing different airway generations (generation 0 represents the trachea, generation 16 the respiratory bronchioles). The locally deposited fractions were calculated by two mathematical functions: one described the deposition patterns of fine particles with pronounced deposition in airways, the other described the pronounced deposition of coarse particles in the mouth–throat region. These two functions were evaluated by comparison with simulated deposition patterns of inhaled particles calculated with the Multiple-Path Particle Dosimetry (MPPD; see Discussion) software program (46) showing an overall good agreement. A pulmonary dissolution process was not incorporated in the model as a droplet formulation was administered. After deposition in the lung, drug was quickly absorbed from the bronchial surface to the muscle compartments. The absorption rate constants of each airway generation to the specific muscle compartment and the transfer rate constant from the muscle to the plasma compartment were calculated for each of the 17 airway generations. The simulated PK results were not evaluated based on clinical PK data, but on PD predictions. Therefore, although PD is not the focus here, it is of high interest to shortly summarize, as the final PBPK model was evaluated based on efficacy predictions. For this purpose, bronchodilation in different airway generations was calculated based on drug amount in the corresponding muscle compartment of the airway generation, also assuming predefined airway obstruction patterns in asthma patients before drug inhalation. In a second step, the treatment-related lower airway obstructions were used to calculate the total airway resistance of all airways. Finally, the total airway resistance was used to calculate FEV1 over time and compare the result to reported FEV1 profiles (47). Even though this model has only been evaluated for one bronchodilator, Gaz et al. underlined that this model might be adapted for different bronchodilators or drug formulations, e.g., for different inhaled particle sizes.

Generic PBPK Models

Generic PBPK models for inhalation have recently been presented being implemented in software programs. Hence, they can only be outlined in the context of the software tools: For GastroPlus™, the Additional Dosage Routes Module (ADRM™) expands the classical implemented PBPK model to the specific characteristics of drug absorption after inhalation (48). Pfizer’s developed in-house model has been embedded into the PulmoSim™ software (49). These two models will be referred to as ‘model GP’ and ‘model PS’, respectively.

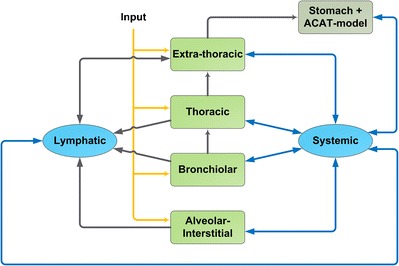

Model GP uses an approach analogous to that by Gaz et al. (45). As a first step, the pulmonary deposition patterns of particles have to be specified by choosing between the two following options: If prior information on pulmonary particle deposition patterns is available, the deposition patterns can be defined manually. Alternatively, if deposition patterns are unknown, the software allows their calculation by means of an embedded particle deposition model published by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP 66 model) (17). Both the model GP and the ICRP 66 model divide the airways into four different pulmonary compartments (Fig. 3), namely the extra-thoracic, thoracic, bronchiolar, and alveolar-interstitial compartment (17). Particles deposited in the extra-thoracic compartment are swallowed and GI absorption is calculated with an Advanced Compartmental Absorption and Transit (ACAT) absorption model (50). The dissolution process of particles that are deposited in one of the three remaining pulmonary compartments is calculated with e.g., the Noyes–Whitney function (51) including various particle and mucus characteristics (e.g., pH value).

PBPK absorption model for inhaled drugs (Additional Dosage Routes Module implemented in the GastroPlus™ software). Yellow arrows, drug input to the lung compartments; light green boxes, lung compartments; dark green box, GI tract compartment (stomach, Advanced Compartmental Absorption and Transit model); blue boxes, systemic disposition compartments; black arrows, transport processes to/from the lung; blue arrows, systemic distribution processes, adapted and modified with permission from (48)

Pulmonary absorption to the plasma of dissolved drug is considered as a passive process that is specifically calculated for each of the three pulmonary absorption compartments by accounting for both human pulmonary anatomical and physiological parameters (e.g., surface area, thickness and volume for mucus and pulmonary cells) and drug-dependent input parameters (e.g., pulmonary permeability) (48). Other aspects of drug inhalation such as different mucociliary clearances depending on the specific pulmonary compartment, pulmonary metabolism, or mucus binding of the drug are included in the model GP. However, as an adequate distribution of metabolizing enzymes or transporters and their transformation kinetics are rarely found in literature, the model GP may still need adaption for each specific research question. The PBPK model was evaluated by simulating and comparing the plasma concentration-time profiles of inhaled drugs with clinical data, e.g., morphine (52), triamcinolone acetonide (53), budesonide (54), and tobramycin (55). While some PK parameters were fitted based on clinical data, it was emphasized that concentrations for inhaled budesonide were simulated without fitting parameters to measured concentrations. It was concluded in that article that the predictions provided a “very reasonable agreement” (54) to observed concentrations.

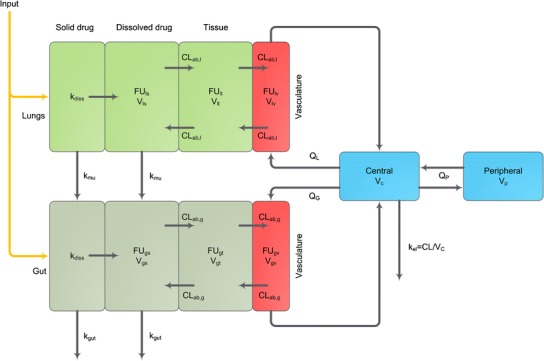

The second generic PBPK model for inhaled drugs, namely model PS, differentiates the inhaled drug into two separate fractions to adequately predict the absorption characteristics (Fig. 4) (49). One fraction is deposited in the lung, whereas the remaining fraction is absorbed in the GI tract. Particles in the lung may dissolve and dissolved drug is either absorbed to lung tissue or cleared by the mucociliary clearance to the gut compartment before absorption takes place. Both undissolved and dissolved drug is cleared unless it has been absorbed into lung tissue. Absorption of drug from the pulmonary tissue to plasma is dependent on the unbound fraction of the drug in the lung meaning that a high tissue affinity of drug in the lung results in both high pulmonary retention/transition times and slow pulmonary absorption to plasma. Unfortunately, to this date, there has been no publication using this PBPK model so that it is not possible to give more detailed information on this model and, more importantly, to assess its performance.

PBPK model for inhaled drugs (PulmoSim™). Subscripts: l lung, g gut, s solution, t tissue, v vasculature; parameters: k diss dissolution rate constant, k mu mucociliary rate constant, k gut elimination rate constant from the gut, k el elimination rate constant from the central compartment, FU fraction unbound, CL ab absorptive clearance across tissue, V physiological distribution volumes, Q G flow rate to the gut vasculature, Q L flow rate to the pulmonary vasculature, Q P intercompartmental clearance; light green boxes, pulmonary compartments; dark green boxes, gut compartments; red boxes, vasculature compartments in the specific organs; blue boxes, systemic disposition compartments

Aside from these models, other generic PBPK models are available; however, (yet) without a specific submodel to account for the absorption characteristics of oral drug inhalation, e.g., the SimCyp Simulator™ describes the pulmonary absorption of drug with a single first-order absorption process (56). These PBPK models will not be further discussed here.

Comprehensive Overview on Empirical (Data-Derived) PK Models

Compared with the previously discussed PBPK approaches, more publications described the systemic PK after drug inhalation with empirical models. A full list of empirical models and the corresponding model structure can be found in Table I.

Table I

Empirical Models Which Describe the (Systemic) PK After Oral Drug Inhalation with an Inhalation Device

| Drug | Inhalation device | Trial population | Data | Data analysis methoda | Systemic disposition model | Absorption model | Oral BAb | Safety/efficacy assessment | Model type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active metabolite of ciclesonide | pMDI | Healthy volunteers, AB patients (adults and pediatrics), patients with liver cirrhosis | Inhalation data | NLME approach | 1 CMT body model | First-order absorption process | Negligible | Safety | I | (61) |

| Active metabolite of ciclesonide | pMDI | Healthy volunteers, AB patients | Inhalation data | NLME approach | 1 CMT body model | First-order absorption process (absorption rate constant could not be estimated and was fixed to a high value) | Negligible | Safety | I | (62) |

| Active metabolite of ciclesonide, fluticasone propionate | pMDI | AB patients | Inhalation data | NLME approach | Ciclesonide metabolite: 2 CMT body model; fluticasone propionate: 1 CMT body model | Ciclesonide metabolite: first-order absorption process, fluticasone propionate: first-order absorption process | Negligible | Safety | I | (63) |

| Albuterol (R) and (S) enantiomer | Nebulizer (PARI LC PLUS®, DURA-NEB® 3000) | 4- to 11-year-old patients with mild to moderate AB | Inhalation data | NLME approach | 2 CMT body model (R), 1 CMT body model (S) | Zero-order absorption process (R and S) | (R): 18%, (S): 68% | n.r. | I | (69) |

| Albuterol (R) and (S) enantiomer | MDI (Proventil®, Schering Corp.) + + spacer (Aerochamber™) spacer (Aerochamber™) | Healthy volunteers (males and females) | Inhalation data | 2-stage approach | 2 CMT body model | First-order absorption process | 40–50% | n.r. | I | (68) |

| Amikacin (liposomal) | Pari LC® Star jet™ nebulizer | Cystic fibrosis patients | Inhalation (plasma and urine data) | NLME approach | 1 CMT body model | First-order absorption process | n.r. | Efficacy (correlation between AUC and pulmonary efficacy tested) | I | (98) |

| Budesonide (epimeric), fluticasone propionate | pMDI | Healthy volunteers | Inhalation data | NLME approach (exploratory 2-stage approach) | Budesonide: 1 or 2 CMT body model, fluticas1 propionate: 1 CMT body model | Budesonide: first-order absorption process Fluticasone propionate: first-order absorption process | Budesonide: 10%, fluticasone propionate: 1% | n.r. | I | (64) |

| Budesonide, flunisolide, fluticasone proprionate, triamcinolone acetonide | Not predefined | Healthy volunteers | Inhalation and IV data | Semi-mechanistic empirical modeling | Budesonide, flunisolide, fluticasone propionate: 2 CMT body model, triamcinolone acetonide: one CMT body model | 3 first-order absorption processes (2 for pulmonary absorption, 1 for absorption from the GI tract), also accounting for pulmonary dissolution processes | Budesonide: 11%, flunisolide: 20%, fluticasone proprionate: <1%, triamcinolone acetonide: 23% | n.r. | II | (81) |

| Budesonide/fluticasone propionate | Turbohaler® (budesonide), Diskus® (fluticasone propionate) | Healthy volunteers | Inhalation Data | NLME approach (exploratory 2-stage approach) | Budesonide: 1 CMT body model, fluticasone propionate: 2 CMT body model | Budesonide: first-order absorption process (absorption rate constant fixed to high value), fluticasone propionate: first-order absorption process | Budesonide: 10%, Fluticasone propionate: 1% | Safety | I | (65) |

| Ciprofloxacin | T-326 DPI | Healthy volunteers | Inhalation, IV, and oral data | 2-stage approach | “Previously validated simulated concentration-time profile” | Instantaneous bolus input, absorption from the GI tract CMT (not further specified), additional transit CMT to the GI tract | n.r. | Safety | II-b | (80) |

| Fenoterol | pMDI | AB patients | Oral and nasal inhalation, IV bolus, and IV infusion data | 2-stage approach | 3 CMT body model | First-order absorption process | 1.5% | Safety | I | (94) |

| Fluticasone propionate | DPI (Diskus® dry powder device) | Healthy volunteers | Inhalation data | 2-stage approach | 2 CMT body model | First-order absorption process | Negligible | n.r. | I | (66) |

| Fluticasone Propionate | pMDI attached to AeroChamber Plus® with Facemask or Babyhaler® | 1- to 4-year-old AB patients | Inhalation data | NLME approach | 1 CMT body model | Zero-order absorption process | Negligible (<1%) | n.r. | I | (67) |

| Formoterol | pMDI | Healthy volunteers | Inhalation data | 2-stage approach | 2 CMT body model | 2 first-order absorption processes from GI tract (+lag time) and lung | “Significant” (68)—included in the model | Safety | II | (70) |

| GLP-1 | DPI (MedTone® Inhaler) | Healthy volunteers, DM type 2 patients | Inhalation data | NLME approach | Healthy volunteers: 2 CMT body model, type 2 DM: 1 CMT body model | First-order absorption process | n.r. | Systemic efficacy | I | (75) |

| Glycopyrronium bromide | DPI (Breezhaler® Device) | Healthy volunteers | Inhalation (with and without charcoal treatment) and IV data | NLME approach | 3 CMT body model | 3 first-order pulmonary absorption processes (fastest: instantaneous input), 1 first-order GI tract absorption process | 8.2% | n.r. | II | (59) |

| HMR1031 (VLA-4 antagonist | DPI (Ultrahaler®) | Healthy volunteers (males) | Inhalation data | NLME approach | 1 CMT body model | First-order absorption process | 5% (preclinical data) | n.r. | I | (77) |

| Indacaterol | Single-dose DPI | COPD patients (Asian and Caucasian populations), AB patients | Inhalation data | NLME approach | 2 CMT body model | Instantaneous input | n.r. | n.r. | I | (71) |

| Insulin | Soft mist inhaler (AERx® IDMs), DPI (Spiros™ blisterdisk® inhaler) | DM type 1 patients, healthy volunteers (male and female) | Inhalation and subcutaneous data | Model-based meta-analysis | 1 CMT body model (developed with SC data with assumption: 100% subcutaneous bioavailability) | First-order absorption process | n.r. | Systemic efficacy | I | (41) |

| Insulin/Insulin lispro | Nebulizer, DPI, AERx®, Exubera® | Healthy volunteers (smoker and non-smoker), DM type 1 and type 2 patients | Inhalation and IV data | Model-based meta-analysis | 2 CMT body model (rate constants estimated and volume of distribution fixed to literature value) | First-order absorption and first-order non-absorption loss | n.r. | n.r. | I-b | (42) |

| Insulin (human recombinant DNA origin) | DPI (Model M, Boehringer Ingelheim and Model Alpha, MannKind Corporation) | Healthy volunteers (non-smoking male and female) | Inhalation, subcutaneous and IV data | NLME approach | 2 CMT body model | First-order absorption process | n.r. | n.r. | I | (79) |

| Laninamivir octanoate (prodrug), Laninamivir | “prototype” and “commercial” | Healthy volunteers, adults with renal impairment, patients with influenza virus infection (adult and pediatric) | Inhalation data | NLME approach | Laninamivir octanoate: 2 CMT body model, laninamivir: 1 CMT body model | Laninamivir octanoate: instantaneous input, laninamivir: first-order absorption process | Laninamivir octanoate: 0.3%, Laninamivir: 3.5% | n.r. | I | (74) |

| Morphine | Soft mist inhaler (AERx® system) | Healthy volunteers | Inhalation and IV data (arterial sampling) | NLME approach | 3 CMT body model with lag time for IV dosing | 2 CMT absorption model | 25% | Safety | II | (60) |

| Olodaterol | Soft mist inhaler (Respimat®) | Healthy volunteers | Inhalation and IV data | NLME approach | 3 CMT body model | 3 parallel first-order absorption processes | Negligible | n.r. | II | (57) |

| PF-00610355 | DPI (MIAT) DPI (CRC-749) | Healthy volunteers, AB patients, and COPD patients | Inhalation data | NLME approach | 3 CMT body model | First-order absorption with 1 transit CMT | 28-36%c | n.r. | I-a | (72) |

| Pitrakinra | DPI (RS01 Dry Powder Inhaler-Model 7), Nebulizer (PARI LC® Plus Turbo nebulizer) | AB patients, eczema patients | Inhalation and subcutaneous data | NLME approach | 1 CMT body model | Single-dose: first-order absorption process with lag time, multiple dose: first-order absorption process without lag time | n.r. | Correlation between systemic PK and efficacy tested but not significant | I | (99) |

| Prochlor-perazine | Single-dose delivery system (Staccato® system delivery platform) | Healthy volunteers | Inhalation and IV data | NLME approach | 2 CMT body model | 3 parallel absorption processes with transit CMTs (relevant for both inhalation and IV administration) | Low (78) | n.r. | II-a | (78) |

| Tiotropium | Soft mist inhaler (Respimat®) | Healthy volunteers | Inhalation and IV data (both urine and plasma) | NLME approach | 4 CMT body model (with Michaelis–Menten non-renal elimination and Michaelis–Menten peripheral binding) | 2 parallel first-order absorption processes | Negligible | n.r. | II | (58) |

| Tobramycin | TOBI® Podhaler® | Cystic fibrosis patients | Inhalation data | NLME approach | 2 CMT body model | First-order absorption process | n.r. | n.r. | I | (76) |

| Zanamivir | DPI | Healthy volunteers, influenza-like illness patients | Oral and nasal inhalation data | NLME approach | 1 CMT body model | First-order absorption process | n.r. | n.r. | I | (73) |

AB asthma bronchiale, BA bioavailability, CMT compartment, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, DM diabetes mellitus, DPI dry powder inhaler, GI gastrointestinal, IV intravenous, NLME nonlinear mixed-effects, n.r. not reported, (p)MDI (pressurized) metered dose inhaler, SC subcutaneous

aSome data evaluations also contained non-compartmental analyses. These approaches are not listed here as they are not part of the review

bValues for oral bioavailability are from the specific publication

cValue not representing oral bioavailability but contribution of the orally absorbed fraction to the total systemic exposure

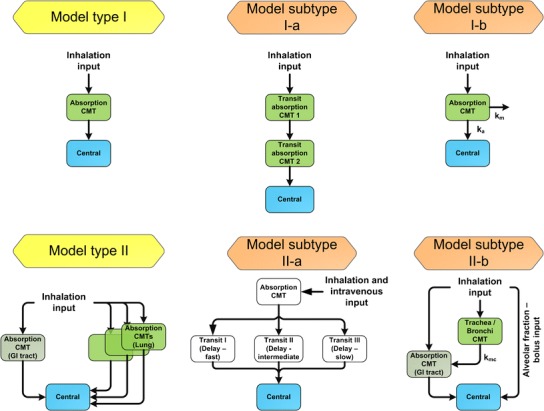

The structure of most absorption models in literature was comparable and can be attributed to one of the two main absorption model types, model type I and model type II, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The majority of empirical PK models was based on inhalation data alone and described the systemic PK by a one or two compartment systemic disposition model with a single absorption process (model type I, Fig. 5). When additional data was available (e.g., IV, subcutaneous (SC), oral), the absorption models tended to increase in complexity. These more complex PK models often described the absorption with parallel absorption processes describing pulmonary and GI tract absorption processes (model type II, Fig. 5). In general, if drug was bioavailable after swallowing, the absorption from the GI tract was described by a single absorption process, whereas pulmonary absorption was described with multiple absorption processes (57–60). Integration of additional aspects in the model types (e.g., pulmonary clearance processes) led to the model subtypes presented in Fig. 5.

Absorption model types (yellow boxes) and model subtypes (orange boxes) used for empirical PK modeling. Only structural models that were published and applied for modeling of plasma concentration-time profiles after oral drug inhalation are presented. Model type I, single absorption compartment linked to a systemic disposition model; model subtype I-a, absorption with a transit compartment model; model subtype I-b, absorption with parallel pulmonary metabolism; model type II, multiple absorption compartments linked to a systemic disposition model; model subtype II-a, absorption with three parallel transit absorption compartment models; model subtype II-b, absorption model with different absorption processes: absorption in the alveolar space treated as pulmonary bolus input (instantaneous absorption), transit absorption compartment (trachea/bronchi), and GI tract absorption. k a absorption rate constant, k m metabolism rate constant, k mc mucociliary rate constant; light green boxes, pulmonary compartments; dark green boxes, GI tract compartments; blue boxes, systemic disposition model. For convenience, the systemic disposition model is simplified to a single central compartment

Empirical PK Models Based on Inhalation Data Only

When no IV or other additional data was available for model development, the model type I was preferentially used to describe the PK of inhaled drugs. For instance, empirical models describing the PK of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), namely ciclesonide (and its active metabolite) (61–63), budesonide (64, 65), fluticasone proprionate (63, 65–67) implemented a single absorption process. Other models based only on inhalation data described the PK of albuterol (68, 69), formoterol (70), indacaterol (71), PF-00610355, β2-adrenoceptor agonist, (72), zanamivir (73), laninamivir octanoate, prodrug transformed in the lung, and its active form laninamivir (74), GLP-1 (75), tobramycin (76), and HMR1031, VLA-4 antagonist (77) characterized the absorption by the same models. The single absorption process was implemented as a first-order (62–66, 68, 73–77) or a zero-order absorption process (67, 69). Variations of model type I included the absorption process being implemented as an IV bolus input or as a fixed high first-order absorption rate constant (62, 65), as the available PK data did not allow estimating the high absorption rate constant (71, 74). Alternatively, the use of a transit absorption model was described (model subtype I-a, Fig. 5) (72). Even though only inhalation data was available, PK after formoterol inhalation was characterized more detailed by model type II (70) with one pulmonary and one absorption process from the GI tract due to a measurable double peak in the plasma concentration-time profile and assuming significant oral bioavailability based on prior information.

Empirical PK Models Based on Inhalation and Additional Data

When IV data was additionally available for model development, the complexity of the resulting PK models increased. Especially the absorption model tended to be more detailed, whereas the majority of the systemic disposition models remained the same. For instance, the absorption process of morphine was described by a two compartment absorption model (60), whereas the absorption of olodaterol (57) and glycopyrronium (59) was described by three parallel pulmonary absorption processes characterized with different absorption rate constants (see model type II, Fig. 5). GI tract absorption was either negligible or modeled separately from pulmonary absorption. However, for this purpose additional oral data or inhalation data with charcoal was necessary. By administering charcoal in addition to inhaled glycopyrronium to prevent GI tract absorption of swallowed drug, Bartels et al. (59) were able to differentiate between pulmonary and GI tract absorption. An even more complex version of model type II was identified for prochlorperazine, as the absorption from an absorption compartment was characterized with three parallel transit compartments. However, differing from the other models for drug inhalation, the inhaled dose as well as the IV dose were administered into the absorption compartments (model subtype II-a, Fig. 5) (78).

Moreover, by including IV or subcutaneous data into the empirical analysis, three groups characterized the PK of insulin with a first-order absorption process (model type I, Fig. 5) (41, 42, 79), whereas Sakagami described the first-order absorption process parallel to a pulmonary first-order loss that was discussed to represent the pulmonary metabolic degradation of insulin (model subtype I-b, Fig. 5) (42).

Semi-Empirical Models

Besides the discussed empirical approaches, Stass et al. presented a more mechanistic modeling approach to describe the PK of ciprofloxacin (80) and Weber et al. published an approach in which the PK parameters were not estimated based on clinical data, but derived from literature (81). To describe the PK of ciprofloxacin, the model was based on prior knowledge about the PK of inhaled drugs (model subtype II-b, Fig. 5). It was assumed that the fraction deposited in the alveolar space (FAl) was instantaneously absorbed to the plasma, whereas the fraction deposited in the mouth–throat (FMT) was completely swallowed and absorbed in the GI tract. No absorption in the trachea and bronchi was “allowed” so that drug deposited in the trachea/bronchi (FTB) was assumed to be completely transported by the mucociliary clearance (characterized with kMC) to the mouth–throat and subsequently swallowed. However, the PK parameters describing the absorption (FAl, FMT, FTB, kMC) were not based on, e.g., prior deposition information but estimated by a two-stage approach. Hence, this PK model is considered as an empirical model.

The PK model by Weber et al. was developed on the basis of a previously published “theoretical PK/PD model” (10). This PK/PD model was extended with PK parameter estimates from the literature (e.g., the PK parameters of the systemic disposition model) for inhaled corticosteroids (81). PK parameters not available from literature, such as for absorption characteristics had to be assumed (absorption rate constants, pulmonary deposition patterns). The mouth–throat fraction was assumed to be swallowed and dependent on the defined oral bioavailability, might be absorbed in the GI tract. The pulmonary dose (drug deposited in the lung) was further differentiated into two kinetically differently absorbed fractions (central/peripheral). In addition, mucociliary clearance and dissolution rate estimates were derived from literature and included in the PK model. Simulations performed with the PK model were compared with the PK results of four studies and indicated a satisfactory predictive performance of the PK model.

Covariates in Empirical PK Models

Besides the structural part of empirical PK models, which describes the typical behavior in absorption and systemic disposition after drug inhalation (see Fig. 5), covariates (patient-specific characteristics) were often implemented in the PK models to explain variability in the PK parameters between different individuals or population subgroups. Covariates identified to explain interindividual variability of absorption parameters (absorption rate constants, pulmonary bioavailability, etc.) were (i) cigarette smoking and (ii) deeper inhalation; both predictors increased the pulmonary absorption rate constant and the pulmonary non-absorptive loss of insulin (42), (iii) a higher inhaled insulin dose that was demonstrated to decrease the pulmonary bioavailability, but increase the pulmonary absorption rate constant (41), (iv) the disease status: diabetes mellitus type 2 increased the pulmonary absorption rate constants (75), whereas asthma patients had a higher pulmonary absorption rate constant and a lower relative bioavailability (72), and (v) different inhalation devices (72).

DISCUSSION

Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling

Depending on drug-specific characteristics, different aspects might need consideration in the modeling approach; e.g., if a particle formulation is administered and the drug/drug formulation is slowly dissolving in airway fluids, literature suggests that both the dissolution process and the pulmonary clearance processes are of kinetic relevance for modeling both the systemic and pulmonary PK. The PK predictions of the PBPK model do not only depend on the choice of implemented aspects (e.g., if a pulmonary drug dissolution is implemented into the model), but also on their way of inclusion in the model (e.g., how pulmonary dissolution is characterized). The main aspects that were implemented in the PBPK models will therefore be discussed in the following sections; however, not as a complete list of all possibly relevant aspects—additional aspects such as pulmonary metabolism may additionally need consideration.

Pulmonary Drug Deposition Patterns

Both Gaz et al. (45) and the model GP (48) identified the pulmonary particle deposition patterns as a relevant factor contributing to both the pulmonary and systemic PK. The model GP implemented the ICRP66 model to predict pulmonary drug deposition, whereas Gaz et al. evaluated the deposition patterns with the MPPD model. Both the MPPD and the ICRP 66 deposition models originate from the toxicology area and were developed with healthy volunteer data (17); these deposition models, therefore, only partly reflect deposition characteristics after drug inhalation with an inhalation device. Thus, using the ICRP 66 model for predicting deposition patterns (in patients) after drug inhalation with a metered dose inhaler (MDI) or dry powder inhaler (DPI) led to overprediction of the pulmonary dose and underprediction of the mouth–throat fraction (82). Possible explanations for the constantly overpredicted pulmonary dose might be an inhaler spray momentum (ballistic effect; high aerosol velocity produced) of MDIs (83), turbulent inhaler jet effects (84), or coarse effects (particle deagglomeration dependent on inhalation flow) of DPIs (28, 85). The lung deposition of a nebulizer without a strong ballistic or coarse effect was accurately predicted (82).

Computational Fluid Dynamics models (reviewed by Longest and Holbrook) (86) could offer a solution to overcome the illustrated drawbacks of currently used particle deposition models. To this date, they are however computationally too intensive (86) for applying them for standard PBPK analyses.

Dissolution and Pulmonary Clearance Processes

The model by Gaz et al. (45) did not include any dissolution step. Therefore it is not adaptable to situations in which pulmonary dissolution is of importance. This might be relevant even for inhaled solutions as drug may still deposit (after evaporation processes and crystallization of the drug) in form of solid drug particles. Currently, little quantitative information is available about pulmonary drug dissolution. Additional knowledge is necessary for realistically including pulmonary dissolution in a PBPK model, e.g., how to quantify pulmonary dissolution in different areas of the lung, as differences in both composition and volume of the airways lining fluid exist dependent on where drug is deposited (12, 13). A non-uniform pulmonary deposition of particles may theoretically further impact the dissolution process, e.g., particle agglomerates at airway bifurcations might dissolve more slowly compared with single uniformly deposited particles. This example underlines importance of in vitro assays that adequately represent pulmonary specific dissolution characteristics. In general, in vitro in vivo correlations (IVIVC) need to be demonstrated before PBPK approaches can be used to predict reasonably both pulmonary (regional) and systemic PK of inhaled drugs.

An adequate characterization of the pulmonary dissolution process might even be more important, as undissolved particles are cleared by the pulmonary clearance processes. Both model PS and the model GP account for mucociliary clearance processes that “back-transport” the drug to the mouth–throat region. A second, slower process that may represent the macrophage clearance from the alveolar space was not included. However, this simplification may be appropriate as this clearance process with a half-life of at least ~35 or ~115 days (reported by ICRP (17) and NCRP (87), respectively) should not be relevant for drug particles administered by inhalation.

Pulmonary Tissue Affinity of Drugs

Model PS additionally underlined the importance of pulmonary (subcompartmental) tissue affinity for some inhaled drugs. For many drugs, especially weakly basic amines, a high affinity to the lung tissue was discussed, possibly due to lysosomal trapping (88). Alternatively, binding effects, such as target binding to the receptor (89) or exosite binding (binding to a location near the receptor that allows the drug to angle on and off the receptor, discussed for salmeterol (90)) were discussed to explain either a long pulmonary residence time of a drug or/and the long efficacy of inhaled drugs. Both slow drug-receptor dissociation as well as binding to an exosite as rate-limiting processes might delay absorption to systemic disposition and therefore can contribute to long lasting efficacy after drug inhalation. As mentioned for pulmonary dissolution and pulmonary absorption of dissolved drug the impact of these “distribution effects” may depend on the inhaled drug characteristics. If kinetically relevant these effects will be important to consider as they might represent the reason for apparent flip-flop kinetics after drug inhalation. It should also be emphasized that pulmonary distribution processes are relevant after both IV and inhalational drug administration. Redistribution from the systemic drug disposition to the specific model compartments, which represent these “distribution processes,” should be accounted for (see Model PS, Fig. 4).

Summary

In summary, different PBPK approaches have been reviewed, concerning how to mechanistically model and thus simulate the PK of inhaled drugs. Depending on the purpose of the PBPK model (generic or drug-specific), pulmonary dissolution was included in the PBPK model. Other potentially relevant pulmonary PK characteristics were not covered, even by the generic PBPK models, e.g., enzyme or transporter distribution across the lung and their activity or the influence of smoking on the airway characteristics. Therefore, individual airway characteristics in healthy volunteers (or even more pronounced in patients) and the resulting impact on the systemic (and pulmonary) PK may not have been adequately captured by these PBPK models. To account for those limitations, a sound understanding on all above-described relevant PK aspects, such as particle deposition, pulmonary dissolution, absorption of dissolved drug and the interplay of these processes is crucial. As a first step, demonstrating IVIVC or in silico in vivo correlation is necessary before reasonable implementation into (generic) PBPK models. Implementing in vitro data as input for the PBPK models (after demonstrating IVIVC) might also enable to implement population characteristics, e.g., predict the impact of different inhalation flows on lung deposition (example of IVIVC demonstration by Olsson et al. (91)), even in disease populations such as patients with asthma bronchiale or COPD. After demonstration of IVIVC and implementation of the above described aspects will be accomplished, more model evaluation will be necessary with additional clinical PK data of inhaled drugs to demonstrate adequateness of model-based simulations.

Empirical (Data-Derived) PK Modeling

The availability and quality of clinical data are crucial aspects for building an appropriate PK model after oral drug inhalation. Without the availability of IV data (which is frequently not—publicly—available), it is impossible to determine the actual systemic clearance and volume of distribution parameter value (i.e., both can only be determined as apparent parameters, i.e., as a function of the systemic bioavailability). Moreover, drawing conclusions based on inhalation data alone about absorption or dissolution characteristics of the inhaled drug, i.e., the occurrence of the often mentioned flip-flop kinetics after drug inhalation (42, 66, 92) is not feasible. These identifiability issues are also relevant for orally administered solid dosage forms. For inhaled drugs, however, the situation is even more pronounced as the drug can reach the systemic circulation via both routes, the lung and GI tract. Thus, data after IV and oral administration as well as inhalation is highly desirable to allow determination of all PK parameters and specifying the pulmonary drug absorption appropriately. The challenge of flip-flop kinetics after drug inhalation has been discussed in more detail in (66).

Data Below the Lower Limit of Quantification

Even though the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of assays measuring drug concentrations have decreased over the last decades, another data-specific issue after drug inhalation might be the occurrence of plasma concentrations below the LLOQ, as a result of low administered doses for inhaled drugs. Ting et al. discussed this topic for tobramycin, but concluded that for their analysis the low fraction of values below the LLOQ (6.8%) in their dataset could be ignored during model development (76). However, this should not be a general rule, and it is recommended to consider data below the LLOQ in the modeling approach, especially if the censored concentrations represent a considerable fraction in the dataset (93). For tiotropium (58) with a high fraction of data below the LLOQ, urine data were additionally evaluated to adequately characterize the terminal phase. In comparison with plasma data, concentrations in urine might be above the LLOQ for a longer time span (if the drug is renally excreted). Hence, urine data might provide a good alternative or addition to accounting for plasma data below the LLOQ.

Empirical PK Models Based on Inhalation Data Only

Estimation of absorption rate constants was often not feasible. Alternatively, characterizing the absorption as zero-order or bolus input accounted for the lack of data in the absorption phase. It might be emphasized that a first-order absorption rate constant is physiologically more plausible, as a pulmonary zero-order absorption rate constant would only be justified if drug is constantly administered over time (e.g., constant drug nebulization). Dependent on the purpose of the PK analysis (e.g., assessing systemic pharmacodynamics), a single absorption rate constant might be sufficient to describe the (systemic) PK after drug inhalation. However, a more detailed characterization of the absorption processes would be desirable if the purpose of the analysis is to extrapolate to unstudied settings, to increase the mechanistic understanding or to assess local pulmonary efficacy. Compared with oral dosing, the pulmonary absorption process may start directly after drug inhalation (without a lag time); without an adapted sampling scheme the first measured concentration may already represent the Cmax. More extensive sampling in the absorption phase could accommodate this issue. Thereby, it might be possible to differentiate oral from pulmonary absorption, even without IV data (due to a second Cmax, see formoterol example (70)).

Empirical PK Models Based on Inhalation and Additional Data

Additional data of different administration routes allowed investigation of the absorption specific aspects independent of systemic drug disposition. For instance, Bartels et al. were able to identify a very slow pulmonary absorption process for glycopyrronium (59): Systemic PK parameters (e.g., CL, V) had been estimated with empirical modeling of IV data beforehand and were treated as fixed parameters during further model development. Otherwise, the very long terminal half-life and the accumulation of the drug could also have been explained by an additional body compartment with very slow drug kinetics. However, by fixing the systemic disposition parameters it was (reasonably) assumed, that the healthy individuals in both trials (IV and inhalation trial) were comparable. Nonetheless, most IV data is only available in healthy volunteers, and the population characteristics (age, creatinine clearance, etc.) between (elderly) COPD patients and healthy volunteers typically differ. This may be one hurdle for developing empirical models in diseased populations (only one publication provided fenoterol IV data of asthma bronchiale patients) (94). Nevertheless, the approach of fixing the systemic disposition parameters still seems to be the most reasonable method and was extensively used if IV data was available (42, 57, 59, 60). Alternatively, Potocka et al. (79) and Avram et al. (78) estimated the systemic disposition and inhalation PK parameters simultaneously. This approach may have the disadvantage, that an inappropriate absorption model could bias the systemic PK parameters and vice versa. However, further investigation by direct comparison of the results of both approaches is advocated.

Even though the PK models based on both inhalation and IV data tended to support more complex characterizations of the absorption processes, one single absorption process was also demonstrated to appropriately describe the PK of some inhaled drugs. One explanation might be that while the absorption processes through the different barriers of the different airways may differentiate, the dissolution of the drug particles at different sites in the lung may not. Hence, in addition to the slower dissolution process, the more lipophilic character of, e.g., inhaled corticosteroids compared with other drugs, may result in a faster diffusion through the epithelial barriers of the lung (95). A slow dissolution process in the pulmonary fluids in combination with a fast absorption process of the dissolved drug to the plasma might then appear as a single absorption process. Based on clinical data alone, it might not be possible to differentiate between the dissolution and the absorption process, and to this date including information from in vitro dissolution assays may not be trivial as no versatile in vitro dissolution assay representing pulmonary dissolution processes has been established (95–97). Another physiologically plausible explanation for only a single absorption process might be relevant for insulin. Insulin is only negligibly bioavailable after oral dosing and the models implemented pulmonary metabolism of insulin (41, 42). This feature could explain why no slower absorption process of insulin was apparent and only one absorption process was identified that might represent absorption in the alveolar space.

Most empirical PK models developed on both inhalation and IV data indicated at least two absorption processes differing in their absorption half-lives and the corresponding fractions absorbed necessary to describe the data adequately (57, 59, 60, 78, 80). While the fastest absorption processes may physiologically correspond to (dissolution and) absorption in the alveolar space due to the previously mentioned physiological characteristics, the slower absorption processes may either represent GI absorption of swallowed drug (deposited in the mouth–throat region/transported to the mouth–throat region after mucociliary clearance) or pulmonary (dissolution and) absorption of drug deposited in the more central airways. However, to differentiate between slower pulmonary absorption processes and absorption processes in the GI tract, either a charcoal trial needs to be performed (59) or the oral bioavailability needs to be negligible (57).

Another model structure was presented for inhaled prochlorperazine (model subtype II-a, see Fig. 5) (78). From a physiological point of view, the shared absorption (transit) compartments for both IV and inhalational drug administration might be difficult to interpret. If the absorption compartments represent pulmonary distribution processes delaying pulmonary absorption (see discussion “Pulmonary Tissue Affinity of Drugs” above), these compartments might coincide with systemic disposition compartments. However, a model structure without redistribution from the systemic central compartment to the absorption (transit) compartments was identified (model subtype II-a).

General Aspects of Empirical PK Modeling

One important aspect of empirical modeling might be the opportunity to investigate hypotheses to explain PK characteristics after drug inhalation. Unfortunately, rarely presented in literature, the values of the parameter estimates are not discussed: for instance, one advanced approach would be correlating the absorption characteristics (e.g., fast absorbed fraction) to pulmonary deposition patterns. This approach may increase the ability to demonstrate a fast absorption process in the alveolar space or may indicate a quantitative link between the pulmonary particle deposition and the different absorbed fractions. By establishing this quantitative link, using prior mechanistic information (e.g., particle deposition patterns simulated with CFD, or particle size distribution determined with in vitro assays that demonstrated IVIVC) to develop more mechanistic empirical PK models may become feasible. These could in turn be utilized to predict the systemic PK and the absorption processes of various what-if scenarios. Given the data gaps for a comprehensive PBPK model, these semi-mechanistic models might be a very suitable alternative to PBPK approaches for answering important drug development questions, e.g., in optimizing drug formulations, devices used for drug administration, or even predict the PK of different patient populations, e.g., the prediction of the impact of a higher central deposited fraction on absorption processes after inhalation (slowly absorbed) in patients compared with healthy volunteers (32) or a higher peripheral fraction (fast absorbed) if a drug formulation with a higher fine particle fraction (particles <5 μm aerodynamic diameter) is inhaled.

Another challenge that might be addressed by empirical modeling is to establish a quantitative link between the (systemic) PK and the efficacy of an inhaled drug. Even though on a theoretical level, the relationship between PK parameters and efficacy has been evaluated (7), to this date not a single empirical PK/PD model has been published capable to demonstrate a relation between efficacy of a locally acting inhaled drug to systemic PK, whereas several approaches accounted for the systemic safety of inhaled drugs (see Table I). A likely explanation is that the lung as the target organ is localized before absorption to plasma, where drug concentrations are typically measured. Moreover, drug absorbed from either the lungs or the GI tract differently contributes to pulmonary efficacy, even though both absorption processes might similarly contribute to systemic exposure. Another challenge might be to use empirical models of the systemic PK to accurately characterize the pulmonary absorption processes and gain information on the pulmonary PK itself. Pulmonary PK may than contain more valuable information, which might be used for efficacy assessment.

Empirical models developed with both IV and inhalation data might also enable to differentiate between covariate effects specific for aspects of drug inhalation and systemic disposition. Some possibly relevant covariates for the inhalation parameters might be smoking, an airway disease, age, etc. By including covariates, it might be possible to further increase the understanding about the PK of inhaled drugs.

Summary

In summary, the following fundamental recommendations should be considered for empirical modeling the PK of inhaled drugs: (i) IV data is crucial to determine the total and pulmonary bioavailability and to determine if flip-flop kinetics is present, (ii) a charcoal trial or data after oral administration is necessary to differentiate between pulmonary and GI tract absorption, (iii) the impact of accounting for a high fraction of data below the LLOQ should be considered as a result of low doses administered by inhalation, (iv) the sampling scheme should be adapted to the specific characteristics of inhaled drugs (start of PK sampling directly after drug inhalation as no lag time for pulmonary absorption is expected), (v) different absorption models with, e.g., different numbers of parallel absorption processes should be investigated to increase the understanding about the pulmonary processes, and (vi) the PK model should be used to develop and test hypotheses about the physiological/mechanistic background of both systemic and pulmonary PK of inhaled drugs, i.e., to test if the pulmonary particle deposition patterns are in agreement with the model.

CONCLUSIONS

Pulmonary deposition, dissolution, and absorption are highly complex processes influencing the pulmonary and systemic PK after oral drug inhalation. These highly complex processes and still missing/incomplete or imprecise mechanistic information may represent the major challenges for building appropriate PBPK models. Both factors also increase the difficulty in interpreting the outcomes of empirical PK modeling. In addition, the challenge in linking systemic PK with pulmonary efficacy may be another factor contributing to the limited number of existing PK models for orally inhaled drugs.

Additional investigations comprising in vitro experiments, clinical studies, and more sophisticated mathematical approaches are necessary for elucidating the highly complex pulmonary deposition, dissolution, and absorption processes. With this additional knowledge, the PBPK approach might gain additional attractiveness. (Semi-)mechanistic modeling offers an alternative to generate and investigate hypotheses and to understand the pulmonary and systemic PK after drug inhalation.

References

Articles from The AAPS Journal are provided here courtesy of American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-015-9760-6

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1208/s12248-015-9760-6.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/168709229

Article citations

The efficacy of nebulized budesonide and ambroxol hydrochloride in treating pediatric community-acquired pneumonia and their impact on clinical characteristics and inflammatory markers.

J Health Popul Nutr, 43(1):132, 27 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39192358 | PMCID: PMC11348777

An in-silico modeling approach to separate exogenous and endogenous plasma insulin appearance, with application to inhaled insulin.

Sci Rep, 14(1):10936, 13 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38740832 | PMCID: PMC11091049

Pulmonary inhalation for disease treatment: Basic research and clinical translations.

Mater Today Bio, 25:100966, 22 Jan 2024

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 38318475 | PMCID: PMC10840005

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Inhalable Bottlebrush Polymer Bioconjugates as Vectors for Efficient Pulmonary Delivery of Oligonucleotides.

ACS Nano, 18(1):592-599, 26 Dec 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38147573 | PMCID: PMC10786149

Development of a Predictive Statistical Pharmacological Model for Local Anesthetic Agent Effects with Bayesian Hierarchical Model Parameter Estimation.

Medicines (Basel), 10(11):61, 15 Nov 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37999201 | PMCID: PMC10672774

Go to all (35) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

A mechanistic framework for a priori pharmacokinetic predictions of orally inhaled drugs.

PLoS Comput Biol, 16(12):e1008466, 15 Dec 2020

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 33320846 | PMCID: PMC7771877

Searching for physiologically relevant in vitro dissolution techniques for orally inhaled drugs.

Int J Pharm, 556:45-56, 07 Dec 2018

Cited by: 15 articles | PMID: 30529665

Review

Advances in experimental and mechanistic computational models to understand pulmonary exposure to inhaled drugs.

Eur J Pharm Sci, 113:41-52, 25 Oct 2017

Cited by: 22 articles | PMID: 29079338

Review

A Partial Differential Equation Approach to Inhalation Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling.

CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol, 7(10):638-646, 04 Sep 2018

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 30084547 | PMCID: PMC6202470