Abstract

Free full text

Disclosure of amyloid status is not a barrier to recruitment in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials

Abstract

Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) clinical trials may require participants to learn if they meet biomarker enrollment criteria to enroll. To examine whether this requirement will impact trial recruitment, we presented 132 older community volunteers who self-reported normal cognition with one of two hypothetical informed consent forms (ICF) describing an AD prevention clinical trial. Both ICFs described amyloid Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scans. One ICF stated that scan results would not be shared with the participants (blinded enrollment); the other stated that only persons with elevated amyloid would be eligible (transparent enrollment). Participants rated their likelihood of enrollment and completed an interview with a research assistant. We found no difference between the groups in willingness to participate. Study risks and the requirement of a study partner were reported as the most important factors in the decision whether to enroll. The requirement of biomarker disclosure may not slow recruitment to preclinical AD trials.

1. Introduction

Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are present years before a person has overt cognitive impairment (Bateman, et al., 2011, Lim, et al., 2014, Morris, et al., 2009, Pietrzak, et al., 2014, Price, et al., 2009), supporting the hypothesis that interventions initiated at these early “preclinical” stages, when neurodegeneration is minimal, may have the greatest likelihood of altering the natural history of AD (Sperling, et al., 2011b). To facilitate testing this hypothesis, a working group sponsored by the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association proposed research diagnostic criteria for a preclinical stage of AD (Sperling, et al., 2011a). In this stage, cognition remains normal or only subtly impaired, but biomarker evidence of AD is present.

Preclinical AD trials must implement one of two designs: blinded or transparent enrollment (Kim, et al., 2015). Blinded designs do not disclose biomarker results to participants. They enroll a proportion of participants who do not demonstrate AD biomarkers so that enrollment is not a de facto disclosure of biomarker status. These participants are non-randomly assigned to placebo, undergo all study procedures, and are followed for the duration of the study. With transparent enrollment, only those who demonstrate biomarker criteria are enrolled and randomized. Biomarker results are disclosed when an investigator informs a person whether he or she is eligible. Both designs have unique risks. For example, blinded enrollment trials may inadvertently disclose biomarker status to participants that do not wish to learn it (Hooper, et al., 2013, Kim, et al., 2015), while transparent enrollment trials bring unique challenges related to confidentiality and the social and psychological impact of learning biomarker results (Arias and Karlawish, 2014).

Which of these designs should researchers use? The answer to this question engages several considerations, including the use of limited resources, the need for timely progress, study feasibility, and the ethical implications of trial designs. The purpose of this study is to empirically inform one specific consideration: the impact on participant recruitment. It is unknown how these two designs will impact recruitment timelines. Also unknown are the factors that might explain why one design is more appealing than the other. Participants’ views cannot entirely settle the competing ethical, clinical and resource considerations, but they do provide an important perspective on how, on a person-by-person basis, they settle these issues. Absent empirical data, trialists, institutional review boards and funders can only speculate over how blinded versus transparent designs impact enrollment, or simply implement these designs and learn from the efforts.

Transparent enrollment preclinical AD trials require people to learn risk information for a disease for which no treatment exists, or may ever exist. But compared to blinded enrollment trials, these trials require fewer participants and closely approximate how clinicians will diagnose and treat sporadic preclinical AD (Burns and Klunk, 2012). If transparent enrollment trials suffer from slow recruitment, then, despite smaller overall sample sizes, these trials may be less efficient than those using blinded designs. Here, we test the hypothesis that a preclinical AD trial with transparent enrollment will have poorer recruitment than one with blinded enrollment. A secondary aim was to identify clinical and trial factors associated with willingness to enroll. We chose to study persons with interest in AD research because they approximate the kinds of persons who would be recruited for a preclinical AD trial.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and recruitment

Participants were required to be age 65 or older, able to complete the study in English, and to have shown interest in AD and AD prevention research, as evidenced by at least one of the following activities: attendance at community education events on AD; enrollment in the UCLA AD Research Center (ADRC) potential participants registry (Grill and Galvin, 2014) or another research registry; referral by a community liaison; self-referral by emailing the UCLA ADRC.

Exclusion criteria included a previous diagnosis of dementia, mild cognitive impairment, or another neurological disease; previous diagnosis of psychiatric disease; or auditory or visual impairments that prevented the conduct of the study interview. All criteria were assessed by self-report. Participants received a $25 gift card to a national retail store for their participation.

2.2. Study design

A research assistant completed a face-to-face interview with all participants. After being read a primer on AD, participants were given the choice of reading or having read to them an informed consent form (ICF) describing a hypothetical AD prevention clinical trial. Using a single sequence of random assignment based on computer-generated random numbers, participants were randomized to consider an ICF that described a trial that did (transparent enrollment design) or did not (blinded enrollment design) require disclosure of amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) results to learn trial eligibility and participate.

Both ICFs described the purpose of amyloid PET, based largely on the materials being used in an on-going preclinical AD trial (Sperling, et al., 2014): “this scan allows doctors to detect amyloid plaques in the brain of a living person;” “the scan tells whether amyloid level is elevated or not; people with Alzheimer’s disease have elevated amyloid levels;” “about 30% of people with normal memory and thinking have elevated amyloid levels.” The blinded enrollment ICF stated “the results of this scan will not be shared;” the transparent enrollment ICF stated “only persons who demonstrate elevated levels of beta amyloid in their brain on the amyloid PET scan will be eligible for this study.”

Both ICFs described a 36-month, double blind, 1:1 randomized study requiring visits at the medical center every 6-months. The aim of the study was to test an oral anti-amyloid therapy with risks including dizziness, headache, nausea, and vomiting, and in more rare occurrences bleeding in the stomach. Listed study procedures included blood draws, cognitive testing, five magnetic resonance imaging scans and three PET scans. The ICF stated that genetic testing for the apolipoprotein E genotype would be performed but that results would not be returned to the participant. The hypothetical trial design was based on preliminary data and intended to elicit an approximately 50% willingness to participate (Grill, et al., 2013).

The research assistant used a scripted interview guide to review the ICF. When discussing the screening process, one additional phrase was included for participants randomized to consider a transparent enrollment design: “Lastly, in this study, only persons who demonstrate elevated levels of beta amyloid in their brain on the amyloid PET scan will be eligible to participate.” Confirmatory questions ensured participant understanding. If a participant was unable to provide the correct answers, the research assistant re-reviewed the hypothetical ICF and confirmed their understanding. Additional questions that addressed the role of amyloid PET in determining eligibility were asked in the transparent enrollment arm, including: “Suppose you were to enroll in this study, would you want to learn your amyloid PET results?” The study materials can be obtained by emailing the corresponding author.

2.3. Measurements

Willingness to participate in a prevention trial

Willingness to participate was assessed with a single question: “How likely would you be to enroll in the described Alzheimer’s disease prevention trial?” Responses were provided using a 6-point Likert scale from “extremely unlikely” to “extremely likely.”

Factors associated with willingness

Importance of trial factors

Subjects used a 6-point Likert scale from “extremely unimportant” to “extremely important” to rate the importance of seven factors in the decision whether to enroll: frequency of visits, location of visits, length of the study, requirement of a study partner, study risks, likelihood of receiving placebo, and required procedures.

Incentives for participation

Participants rated six potential incentives as making them much less likely to enroll, somewhat less likely to enroll, no difference, somewhat more likely to enroll, or much more likely to enroll. The incentives included: receiving overall study results, reports of personal blood test results at each visit, personal genetic testing results, personal cognitive testing results at each visit, financial compensation at each visit, and personal estimates of risk for getting AD.

AD Knowledge Scale (ADKS)

This validated 30-item true or false questionnaire for assessing the level of understanding related to AD (Carpenter, et al., 2009).

Research Attitude Questionnaire (RAQ)

This validated 7-item, 5-point Likert scale survey (Range 7–35) used to assess community dwelling volunteers’ attitudes toward research (Rubright, et al., 2011). Higher scores represent a more favorable attitude toward research.

Risk for AD

This 5-item instrument uses a 5-point scale to assess participant agreement with a series of items pertaining to perceived concern for getting AD. The range is 5–25, with higher scores reflecting a greater perceived risk of AD (Roberts and Connell, 2000).

Cognitive Change Index (CCI)

This 20-item scale examines participants’ perceived cognitive decline, relative to their own level of function 5-years prior. Participants rate their level of ability on a scale of 1 (no change) to 5 (much worse) (Saykin, et al., 2006).

Demographics

A questionnaire assessed participant age, gender, race, ethnicity, education level, retirement status and flexibility in performing job requirements, caregiver status, family history of AD, perceived health status, and the distance from the participant’s home to the medical center.

2.4. Data analyses

We assessed the effectiveness of randomization by comparing the groups’ demographics and other covariates. We used two sample t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square (X2) tests or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and Cochran-Armitage trend tests for ordinal variables (e.g., self-rating of overall health).

We used univariate ordered logistic regression models to examine potential associations between each of the covariates and the outcome of willingness to participate, using the full range of scores on the Likert scale. In addition to the effect of group assignment, the pool of candidate variables included age, race (White vs. non-White), ethnicity (Latino vs. non-Latino), retirement status, family history of AD, distance from the medical center, RAQ score, ADKS score, Risk for AD score, and CCI score as predictors of willingness to participate. Covariates that were moderately associated (p<0.2) in univariate models were included in a multivariable ordered logistic regression model that examined the impact of group assignment when adjusting for other covariates.

We used Friedman tests to examine for overall differences among the importance factors and the incentives to enroll and Wilcoxon signed rank tests to perform post-hoc pairwise comparisons. We conducted these analyses separately for each group and for the combined data set.

All analyses were performed in SAS v.9.3 (Cary, NC). Results of statistical tests are reported with a significance level of 0.05.

2.5. Ethics

This UCLA Institutional Review Board approved the study. All participants signed an IRB-approved informed consent prior to participating.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

A total of 132 participants completed the study. Sixty-three participants attended community outreach events on AD and were enrolled into the UCLA ADRC potential participants registry; six were recruited from the Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative Registry (Reiman, et al., 2011). Twenty-two, mostly minority race, participants were referred by a community liaison; eleven were referred by another community member. Eight learned about the study on the ADRC website. Seven were control subjects in the ADRC longitudinal study. Four were caregivers participating in UCLA support services; UCLA clinicians referred three participants. For eight participants, the source of referral was not captured.

The majority of participants were female, White, and retired (Table 1). Participants were highly educated, had good knowledge of AD, and had favorable attitudes toward research. Eighty percent knew someone with AD but relatively few had a family history or were caregivers. Most rated their overall health as “very good” or “excellent,” but participants in the blinded design rated their health higher than those in the transparent design (p=0.03).

Table 1

Description of the sample.

| Transparent Design | Blinded Design | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 66 | 66 | 1 |

| Mean age, yrs ± SD (range) | 73.1 ± 6.1 (66–89) | 73.6 ± 6.2 (65–89) | 0.62 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 47 (71.2) | 46 (69.7) | 0.85 |

| Race | 0.21 | ||

| White, n (%) | 34 (51.5) | 44 (66.7) | |

| African American, n (%) | 28 (42.4) | 19 (28.8) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander, n (%) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | |

| Other | 3 (4.6) | 3 (4.6) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 6 (9.1) | 1 (1.5) | 0.12 |

| Mean Education, yrs ± SD (range) | 16.3 ± 2.7 (11–24) | 16.3 ± 2.4 (12–22) | 0.84 |

| Retired, n (%) | 53 (80.3) | 55 (83.3) | 0.65 |

| Job freedom | 0.05 | ||

| Never, n (%) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | |

| Rarely, n (%) | 4 (6.1) | 0 | |

| Frequently, n (%) | 11 (16.7) | 10 (15.2) | |

| Always, n (%) | 50 (75.8) | 56 (84.9) | |

| ADKS score, mean ± SD (range) | 23.2 ± 3.0 (16–29) | 23.6 ± 3.4 (15–29) | 0.45 |

| RAQ score, mean ± SD (range) | 29.6 ± 3.4 (22–35) | 29.4 ± 4.4 (7–35) | 0.81 |

| AD Caregivers, n (%) | 5 (7.6) | 5 (7.6) | 1 |

| Family History of AD, n (%) | 15 (23.1) | 17 (26.2) | 0.68 |

| Do you know someone with AD? | 56 (84.9) | 50 (75.8) | 0.19 |

| Risk for AD score, mean ± SD (range) | 16.8 ± 3.9 (8–24) | 16.1 ± 4.3 (5–24) | 0.29 |

| Rating of overall health | 0.03 | ||

| Excellent, n (%) | 9 (13.6) | 20 (30.3) | |

| Very good, n (%) | 33 (50.0) | 29 (43.9) | |

| Good, n (%) | 20 (30.3) | 15 (22.7) | |

| Fair, n (%) | 4 (6.1) | 2 (3.0) | |

| Poor, n (%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Distance to the medical center | 0.44 | ||

| 0–5 mi, n (%) | 23 (34.9) | 32 (48.5) | |

| 5–15 mi, n (%) | 29 (43.9) | 20 (30.3) | |

| 15–30 mi, n (%) | 10 (15.2) | 9 (13.6) | |

| >30 mi, n (%) | 4 (6.1) | 5 (7.6) |

3.2. Willingness to participate

Seventy percent (46/66) of participants in the transparent design and 61% (40/66) in the blinded design were likely to enroll (Table 2). In a univariate model, the effect of group assignment was not significant (OR=1.30; 95% CI:0.71–2.38; Table 3). When asked directly, 55 of 57 (96%) participants in the transparent design said that they would want to know the results of their amyloid PET scan. In univariate models, RAQ score, race (White greater than non-White), retirement status (non-retired greater than retired), and perceived risk for AD were significantly associated with willingness to participate (p<0.05; Table 3). ADKS score (p=0.11), CCI score (p=0.07), and distance from the medical center (p=0.10) were also included in the subsequent multivariable model. In the final multivariable model, only RAQ score (OR=1.12, 95% CI:1.03–1.21) and perceived risk for AD (OR=1.09, 95% CI:1.01–1.18) were significantly associated with willingness to participate. For every one point higher RAQ score, participants were 12% more willing to participate and for every one point higher perceived risk for AD score, participants were 9% more willing.

Table 2

Responses to the primary outcome question.

| Extremely unlikely | Very unlikely | Somewhat unlikely | Somewhat likely | Very likely | Extremely likely | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transparent design, n (%) | 4 (6.0) | 7 (10.6) | 9 (13.6) | 21 (31.8) | 15 (22.7) | 10 (15.2) |

| Blinded design, n (%) | 9 (13.6) | 7 (10.6) | 10 (15.2) | 17 (25.8) | 12 (18.2) | 11 (16.7) |

| Total, n (%) | 13 (9.8) | 14 (10.6) | 19 (14.3) | 38 (28.8) | 27 (20.5) | 21 (15.9) |

Table 3

Results of univariate models.

| Variable (reference group) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Experimental group (transparent design) | 1.30 (0.71–2.38) |

| Age | 0.98 (0.94–1.04) |

| RAQ score | 1.12 (1.03–1.21)* |

| ADKS score | 1.08 (0.98–1.19) |

| Race (non-white) | 2.08 (1.12–3.89)* |

| Ethnicity (non-Latino) | 1.08 (0.28–4.13) |

| Retirement status (non-retired) | 0.42 (0.19–0.94)* |

| Family history (negative) | 1.26 (0.62–2.55) |

| Risk for AD | 1.12 (1.04–1.21)* |

| Cognitive change index | 1.02 (0.99–1.06) |

| Distance from the medical center | 1.32 (0.94–1.86) |

3.3. Importance of trial factors

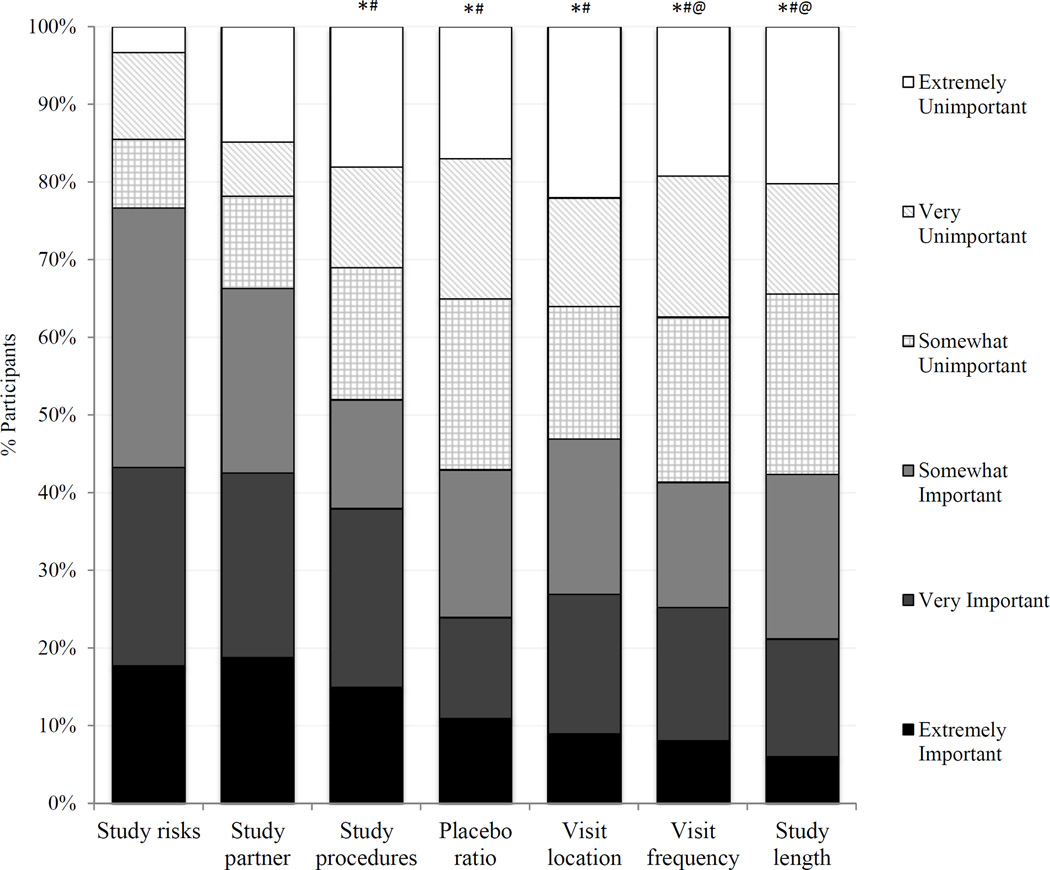

In both randomized groups and when combining data across groups, Friedman tests showed that participant ratings of importance differed among the seven trial factors (p<0.0001). In the transparent design, the ratings of study risks and the requirement of a study partner were significantly higher than every other factor (Wilcoxon signed rank test, p≤0.02). In the blinded design, study risks were rated higher than every other factor (p≤0.01); the requirement of study partner was rated higher than visit frequency and study length; and required procedures were rated higher than visit frequency, study length and visit location. When data were combined across groups, participants rated the study risks and the requirement of a study partner as more important than the remaining five factors (p<0.05 for all pairwise comparisons; Figure 1). Among the remaining factors, study procedures was deemed more important than study length and visit frequency (p<0.05).

3.4. Incentives for participation

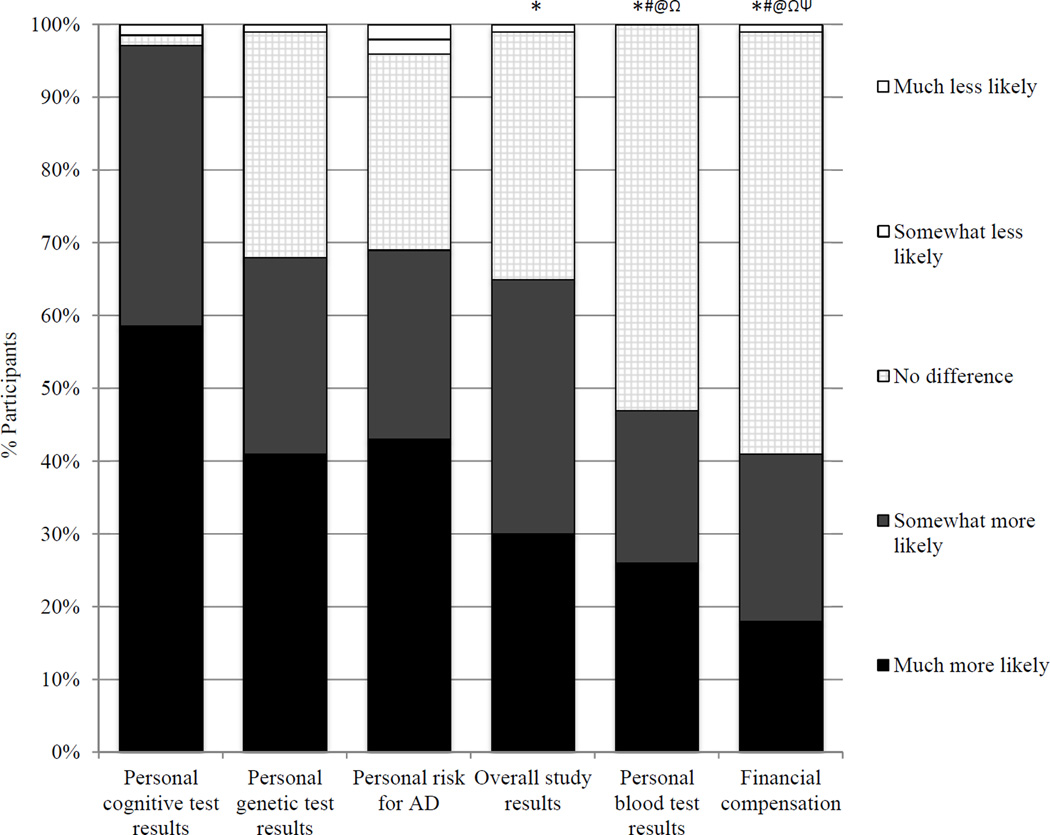

Within each group and in combined analyses, ratings differed among the six potential incentives (Friedman tests, p<0.0001). In both the transparent and blinded designs, receiving cognitive and genetic testing results were rated higher than blood test results and financial compensation (Wilcoxon signed rank test, p<0.05 for all comparisons). In the blinded design, receiving cognitive testing results was also rated higher than receiving overall study results (p=0.02). In both groups, receiving personal AD risk estimates was rated higher than blood test results or financial compensation (p<0.05 for all comparisons) and financial incentive was rated lower than receiving overall study results. In the blinded design, financial incentive also differed from blood test results (p=0.03).

When data were combined across groups, receiving cognitive testing results was rated higher than receiving overall study results, blood test results, and financial compensation (p<0.05 for all comparisons; Figure 2). Participants rated genetic testing results as greater incentive than blood test results and financial compensation (p<0.0001). Financial compensation was rated significantly lower than every other incentive assessed.

Participant ratings of potential incentives for participation. The proportions of participants providing each likert response are illustrated for each potential incentive. *p<0.05 vs cognitive testing results; #p<0.05 vs genetic test results; @p<0.05 vs personal AD risk estimates; Ωp<0.05 vs overall study results; Ψp<0.05 vs personal blood test results.

4. Discussion

This study found no difference in the willingness to participate in AD prevention trials that use blinded versus transparent enrollment. Our sample represents the kind of persons researchers will attempt to recruit to preclinical AD trials, as it was composed primarily of community members who demonstrated interest in AD research. Many had attended public lectures on AD and, in our study, they demonstrated good knowledge of AD and favorable attitudes toward research.

Though some participants did not wish to learn their amyloid status, the frequency of these individuals (<5%) was not sufficient to lower the overall recruitment rate for the transparent enrollment trial. In fact, willingness was numerically higher in the transparent enrollment design. These results suggest that transparent enrollment trials, in addition to offering reduced sample sizes and cost, may not suffer from slower recruitment than blinded enrollment trials. They may even recruit faster.

Other studies examining the desire of healthy individuals to learn their AD risk have had similar findings and may be pertinent to understanding the feasibility of transparent preclinical AD trials. In a telephone survey of Western European and American adults, 67% of respondents reported that they were likely to have a presymptomatic diagnostic test for AD, were one to become available. Desire to undergo testing was highest among those concerned about getting AD (Wikler, et al., 2013). Biomarkers do not offer the certainty of a diagnostic test, however. Neumann and colleagues found similar (70%) rates for desire to undergo predictive genetic testing for AD, but rates fell to 45% for a partially predictive test (Neumann, et al., 2001). Alternatively, these authors found that >70% of respondents in another study were interested in even an imperfect predictive blood test for AD (Neumann, et al., 2012) and a survey of Health and Retirement Study participants found that 60% were interested in learning their AD risk (Roberts, et al., 2014). Collectively, these results suggest that a sizeable proportion of the population may be interested in learning AD risk information and these individuals, especially those concerned about AD, may be most likely to participate in preclinical AD trials and facilitate transparent enrollment.

Our results add to the understanding of barriers to preclinical AD trial recruitment (Grill, et al., 2013). The most important barriers to enrollment were the risk of the study therapy and the requirement of identifying and securing a study partner, a factor deemed more important than the length of the study, number of visits, length of visits, or the procedures involved. Given that preclinical AD trials will recruit cognitively normal, functionally independent community-dwelling individuals, investigators may need to consider reducing study partner requirements by implementing or developing technologies to secure information typically provided through in-person informant-based scales (Mundt, et al., 2007, Sano, et al., 2013).

Measuring research attitudes may identify those likely to enroll and returning research results may incentivize participants. Participants valued receiving cognitive and genetic testing results, more so than blood test or overall study results. A majority of participants responded that financial compensation would not impact their decision whether to enroll (Figure 2), suggesting that the cost of financial incentives for participation may be better spent on teleconferences or in-person events to share study data (Chakradhar, 2015).

To be shared, genetic testing must be performed by a CLIA-certified laboratory and disclosure should be performed in partnership with a genetic counselor (2014). When these requirements are fulfilled, disclosure of genetic information may be safe (Green, et al., 2009) but also has the potential to bias study outcomes (Lineweaver, et al., 2013). Similarly, participants’ perceptions of their expected performance on cognitive tests, which might be impacted by the return of test results, could bias subsequent outcomes (Hess, et al., 2003, Steele and Aronson, 1995). Full consideration of these issues will require further study, but may provide important data to instruct trial design and conduct.

Our study has limitations. The extent to which hypothetical responses predict actual behaviors is not clear and the observed rates of willingness to participate (>60%) may exceed those of a real trial. This is in part due to the hypothetical trial description, which was designed to produce a 50% willingness rate to power examination of differences between the groups. Initial preclinical AD trials are testing infused amyloid-lowering therapies, which carry risks such as amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (Sperling, et al., 2012). The ecological validity of our results may be limited since our hypothetical trial investigated an oral therapy that lacked these risks. Since many trials face protracted recruitment, frequently requiring additional interventions to ultimately achieve study samples, our results may be most instructive to initial enrollment of highly motivated participants in preclinical AD trials. Finally, our data leave several questions unanswered. Transparent enrollment will require more elaborate disclosure processes than was implemented here (Harkins, et al., 2015), and these processes may impact willingness to participate. Furthermore, both blinded and transparent designs are associated with unique risks (see Introduction) and this study did not explore how those risks will impact willingness to participate.

In conclusion, these results suggest that preclinical AD trials implementing transparent enrollment will not suffer slower recruitment because of the requirement of biomarker disclosure. It is possible that some participants will view learning their amyloid PET status as an incentive to enrollment, though this will require further study. This study also suggests that other trial factors, in particular the risks of the intervention and the requirement of a study partner, may have greater impact than biomarker disclosure on recruitment and to overcome these barriers investigators should consider incentives such as providing research results. Although transparent designs are neither coercive nor do they offer undue influence (Kim, et al., 2015), these results may have important implications to the ethics of preclinical AD trials, given that they support the feasibility of this design. Additional research, including assessment of the ongoing preclinical AD trials, will be critical to instruct future trial designs and methods, especially as it relates to biomarker disclosure.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Alzheimer’s Association NIRG 12-242511. Drs. Grill, Zhou, and Elashoff were also supported by NIA AG016570. Dr. Grill is currently supported by NIA AG016573. Dr. Karlawish was supported by NIA P30-AG01024.

Author disclosures: JDG has served as site investigator for clinical trials sponsored by Avanir, Biogen Idec, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions: JDG secured the funding, designed and oversaw the study, drafted the manuscript, edited the manuscript for content, and approved the final draft. YZ and DE performed the statistical analyses, edited the manuscript for content, and approved the final draft. JK designed the study, edited the manuscript for content, and approved the final draft.

References

- Washington (DC): Workshop Summary; 2014. Issues in Returning Individual Results from Genome Research Using Population-Based Banked Specimens, with a Focus on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Arias JJ, Karlawish J. Confidentiality in preclinical Alzheimer disease studies: when research and medical records meet. Neurology. 2014;82(8):725–729. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman RJ, Aisen PS, De Strooper B, Fox NC, Lemere CA, Ringman JM, Salloway S, Sperling RA, Windisch M, Xiong C. Autosomal-dominant Alzheimer's disease: a review and proposal for the prevention of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's research & therapy. 2011;2(6):35. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JM, Klunk WE. Predicting positivity for a new era of Alzheimer disease prevention trials. Neurology. 2012;79(15):1530–1531. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter BD, Balsis S, Otilingam PG, Hanson PK, Gatz M. The Alzheimer's Disease Knowledge Scale: development and psychometric properties. The Gerontologist. 2009;49(2):236–247. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Chakradhar S. Many returns: Call-ins and breakfasts hand back results to study volunteers. Nature medicine. 2015;21(4):304–306. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Green RC, Roberts JS, Cupples LA, Relkin NR, Whitehouse PJ, Brown T, Eckert SL, Butson M, Sadovnick AD, Quaid KA, Chen C, Cook-Deegan R, Farrer LA. Disclosure of APOE genotype for risk of Alzheimer's disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361(3):245–254. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Grill JD, Galvin JE. Facilitating Alzheimer disease research recruitment. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2014;28(1):1–8. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Grill JD, Karlawish J, Elashoff D, Vickrey BG. Risk disclosure and preclinical Alzheimer's disease clinical trial enrollment. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2013;9(3):356–359. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Harkins K, Sankar P, Sperling R, Grill JD, Green RC, Johnson KA, Healy M, Karlawish J. Development of a process to disclose amyloid imaging results to cognitively normal older adult research participants. Alzheimer's research & therapy. 2015;7(1):26. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hess TM, Auman C, Colcombe SJ, Rahhal TA. The impact of stereotype threat on age differences in memory performance. The journals of gerontology Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2003;58(1):P3–P11. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper M, Grill JD, Rodriguez-Agudelo Y, Medina LD, Fox M, Alvarez-Retuerto AI, Wharton D, Brook J, Ringman JM. The impact of the availability of prevention studies on the desire to undergo predictive testing in persons at risk for autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease. Contemporary clinical trials. 2013;36(1):256–262. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Karlawish J, Berkman BE. Ethics of genetic and biomarker test disclosures in neurodegenerative disease prevention trials. Neurology. 2015 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YY, Maruff P, Pietrzak RH, Ellis KA, Darby D, Ames D, Harrington K, Martins RN, Masters CL, Szoeke C, Savage G, Villemagne VL, Rowe CC, Group AR. Abeta and cognitive change: Examining the preclinical and prodromal stages of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2014;10(6):743–751. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lineweaver TT, Bondi MW, Galasko D, Salmon DP. Effect of Knowledge of APOE Genotype on Subjective and Objective Memory Performance in Healthy Older Adults. The American journal of psychiatry. 2013 [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Roe CM, Grant EA, Head D, Storandt M, Goate AM, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA. Pittsburgh Compound B imaging and prediction of progression from cognitive normality to symptomatic Alzheimer disease. Archives of neurology. 2009;66(12):1469–1475. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt JC, Kinoshita LM, Hsu S, Yesavage JA, Greist JH. Telephonic Remote Evaluation of Neuropsychological Deficits (TREND): longitudinal monitoring of elderly community-dwelling volunteers using touch-tone telephones. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2007;21(3):218–224. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann PJ, Cohen JT, Hammitt JK, Concannon TW, Auerbach HR, Fang C, Kent DM. Willingness-to-pay for predictive tests with no immediate treatment implications: a survey of US residents. Health economics. 2012;21(3):238–251. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann PJ, Hammitt JK, Mueller C, Fillit HM, Hill J, Tetteh NA, Kosik KS. Public attitudes about genetic testing for Alzheimer's disease. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20(5):252–264. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Lim YY, Ames D, Harrington K, Restrepo C, Martins RN, Rembach A, Laws SM, Masters CL, Villemagne VL, Rowe CC, Maruff P, Australian Imaging B, Lifestyle Research G. Trajectories of memory decline in preclinical Alzheimer's disease: results from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle Flagship Study of Ageing. Neurobiology of aging. 2014 [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Price JL, McKeel DW, Jr, Buckles VD, Roe CM, Xiong C, Grundman M, Hansen LA, Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, Smith CD, Davis DG, Schmitt FA, Markesbery WR, Kaye J, Kurlan R, Hulette C, Kurland BF, Higdon R, Kukull W, Morris JC. Neuropathology of nondemented aging: presumptive evidence for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurobiology of aging. 2009;30(7):1026–1036. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Reiman EM, Langbaum JB, Fleisher AS, Caselli RJ, Chen K, Ayutyanont N, Quiroz YT, Kosik KS, Lopera F, Tariot PN. Alzheimer's Prevention Initiative: a plan to accelerate the evaluation of presymptomatic treatments. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD 26 Suppl. 2011;3:321–329. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JS, Connell CM. Illness representations among first-degree relatives of people with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2000;14(3):129–136. Discussion 7–8. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JS, McLaughlin SJ, Connell CM. Public beliefs and knowledge about risk and protective factors for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2014;10(5 Suppl):S381–S389. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Rubright JD, Cary MS, Karlawish JH, Kim SY. Measuring how people view biomedical research: Reliability and validity analysis of the Research Attitudes Questionnaire. Journal of empirical research on human research ethics : JERHRE. 2011;6(1):63–68. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sano M, Egelko S, Donohue M, Ferris S, Kaye J, Hayes TL, Mundt JC, Sun CK, Paparello S, Aisen PS Alzheimer Disease Cooperative Study, I. Developing dementia prevention trials: baseline report of the Home-Based Assessment study. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2013;27(4):356–362. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Saykin AJ, Wishart HA, Rabin LA, Santulli RB, Flashman LA, West JD, McHugh TL, Mamourian AC. Older adults with cognitive complaints show brain atrophy similar to that of amnestic MCI. Neurology. 2006;67(5):834–842. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling R, Salloway S, Brooks DJ, Tampieri D, Barakos J, Fox NC, Raskind M, Sabbagh M, Honig LS, Porsteinsson AP, Lieberburg I, Arrighi HM, Morris KA, Lu Y, Liu E, Gregg KM, Brashear HR, Kinney GG, Black R, Grundman M. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in patients with Alzheimer's disease treated with bapineuzumab: a retrospective analysis. Lancet neurology. 2012;11(3):241–249. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR, Jr, Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2011a;7(3):280–292. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Jack CR, Jr, Aisen PS. Testing the right target and right drug at the right stage. Science translational medicine. 2011b;3(111):111cm33. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Karlawish J, Donohue M, Salmon DP, Aisen P. The A4 study: stopping AD before symptoms begin? Science translational medicine. 2014;6(228):228fs13. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1995;69(5):797–811. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wikler EM, Blendon RJ, Benson JM. Would you want to know? Public attitudes on early diagnostic testing for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's research & therapy. 2013;5(5):43. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.11.007

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc4773920?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.11.007

Article citations

Comparing research attitudes in Down syndrome and non-Down syndrome research decision-makers.

Alzheimers Dement (N Y), 10(3):e12478, 31 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39086735 | PMCID: PMC11289724

Remote Evaluation of Sleep and Circadian Rhythms in Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: Protocol for a Feasibility and Acceptability Mixed Methods Study.

JMIR Res Protoc, 13:e52652, 22 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38517469 | PMCID: PMC10998181

The AlzMatch Pilot Study - Feasibility of Remote Blood Collection of Plasma Biomarkers for Preclinical Alzheimer's Disease Trials.

J Prev Alzheimers Dis, 11(5):1435-1444, 01 Jan 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39350391 | PMCID: PMC11436450

Perspectives From Black and White Participants and Care Partners on Return of Amyloid and Tau PET Imaging and Other Research Results.

Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord, 37(4):274-281, 30 Oct 2023

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 37890053 | PMCID: PMC10664783

Recruitment of pre-dementia participants: main enrollment barriers in a longitudinal amyloid-PET study.

Alzheimers Res Ther, 15(1):189, 02 Nov 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37919783 | PMCID: PMC10621165

Go to all (35) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Is Reluctance to Share Alzheimer's Disease Biomarker Status with a Study Partner a Barrier to Preclinical Trial Recruitment?

J Prev Alzheimers Dis, 8(1):52-58, 01 Jan 2021

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 33336225 | PMCID: PMC8112206

Risk disclosure and preclinical Alzheimer's disease clinical trial enrollment.

Alzheimers Dement, 9(3):356-359.e1, 08 Nov 2012

Cited by: 24 articles | PMID: 23141383 | PMCID: PMC3572336

Reactions to learning a "not elevated" amyloid PET result in a preclinical Alzheimer's disease trial.

Alzheimers Res Ther, 10(1):125, 22 Dec 2018

Cited by: 16 articles | PMID: 30579361 | PMCID: PMC6303934

Study partners should be required in preclinical Alzheimer's disease trials.

Alzheimers Res Ther, 9(1):93, 06 Dec 2017

Cited by: 21 articles | PMID: 29212555 | PMCID: PMC5719524

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Alzheimer's Association

NIA (3)

Grant ID: P30-AG01024

Grant ID: AG016570

Grant ID: AG016573

NIA NIH HHS (6)

Grant ID: P30-AG01024

Grant ID: P50 AG016573

Grant ID: AG016573

Grant ID: AG016570

Grant ID: P30 AG010124

Grant ID: P50 AG016570

NIRG (1)

Grant ID: 12-242511