Abstract

Background

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines have been widely introduced in immunization programs worldwide, however, it is not accepted in mainland China. We aimed to investigate the awareness and knowledge about HPV vaccines and explore the acceptability of vaccination among the Chinese population.Methods

A meta-analysis was conducted across two English (PubMed, EMBASE) and three Chinese (China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wan Fang Database and VIP Database for Chinese Technical Periodicals) electronic databases in order to identify HPV vaccination studies conducted in mainland China. We conducted and reported the analysis in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.Results

Fifty-eight unique studies representing 19 provinces and municipalities in mainland China were assessed. The pooled awareness and knowledge rates about HPV vaccination were 15.95 % (95 % CI: 12.87-19.29, I (2) = 98.9 %) and 17.55 % (95 % CI: 12.38-24.88, I (2) = 99.8 %), respectively. The female population (17.39 %; 95 % CI: 13.06-22.20, I (2) = 98.8 %) and mixed population (18.55 %; 95 % CI: 14.14-23.42, I (2) = 98.8 %) exhibited higher HPV vaccine awareness than the male population (1.82 %; 95 % CI: 0.50-11.20, I (2) = 98.5 %). Populations of mixed ethnicity had lower HPV vaccine awareness (9.61 %; 95 % CI: 5.95-14.03, I (2) = 99.0 %) than the Han population (20.17 %; 95 % CI: 16.42-24.20, I (2) = 98.3 %). Among different regions, the HPV vaccine awareness was higher in EDA (17.57 %; 95 % CI: 13.36-22.21, I (2) = 98.0 %) and CLDA (17.78 %; 95 % CI: 12.18-24.19, I (2) = 97.6 %) than in WUDA (1.80 %; 95 % CI: 0.02-6.33, I (2) = 98.9 %). Furthermore, 67.25 % (95 % CI: 58.75-75.21, I (2) = 99.8 %) of participants were willing to be vaccinated, while this number was lower for their daughters (60.32 %; 95 % CI: 51.25-69.04, I (2) = 99.2 %). The general adult population (64.72 %; 95 % CI: 55.57-73.36, I (2) = 99.2 %) was more willing to vaccinate their daughters than the parent population (33.78 %; 95 % CI: 26.26-41.74, I (2) = 88.3 %). Safety (50.46 %; 95 % CI: 40.00-60.89, I (2) = 96.6 %) was the main concern about vaccination among the adult population whereas the safety and efficacy (68.19 %; 95 % CI: 53.13-81.52, I (2) = 98.6 %) were the main concerns for unwillingness to vaccinate their daughters.Conclusions

Low HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge was observed among the Chinese population. HPV vaccine awareness differed across sexes, ethnicities, and regions. Given the limited quality and number of studies included, further research with improved study designis necessary.Free full text

Awareness and knowledge about human papillomavirus vaccination and its acceptance in China: a meta-analysis of 58 observational studies

Abstract

Background

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines have been widely introduced in immunization programs worldwide, however, it is not accepted in mainland China. We aimed to investigate the awareness and knowledge about HPV vaccines and explore the acceptability of vaccination among the Chinese population.

Methods

A meta-analysis was conducted across two English (PubMed, EMBASE) and three Chinese (China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wan Fang Database and VIP Database for Chinese Technical Periodicals) electronic databases in order to identify HPV vaccination studies conducted in mainland China. We conducted and reported the analysis in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Results

Fifty-eight unique studies representing 19 provinces and municipalities in mainland China were assessed. The pooled awareness and knowledge rates about HPV vaccination were 15.95 % (95 % CI: 12.87–19.29, I2 =

= 98.9 %) and 17.55 % (95 % CI: 12.38–24.88, I2

98.9 %) and 17.55 % (95 % CI: 12.38–24.88, I2 =

= 99.8 %), respectively. The female population (17.39 %; 95 % CI: 13.06–22.20, I2

99.8 %), respectively. The female population (17.39 %; 95 % CI: 13.06–22.20, I2 =

= 98.8 %) and mixed population (18.55 %; 95 % CI: 14.14–23.42, I2

98.8 %) and mixed population (18.55 %; 95 % CI: 14.14–23.42, I2 =

= 98.8 %) exhibited higher HPV vaccine awareness than the male population (1.82 %; 95 % CI: 0.50–11.20, I2

98.8 %) exhibited higher HPV vaccine awareness than the male population (1.82 %; 95 % CI: 0.50–11.20, I2 =

= 98.5 %). Populations of mixed ethnicity had lower HPV vaccine awareness (9.61 %; 95 % CI: 5.95–14.03, I2

98.5 %). Populations of mixed ethnicity had lower HPV vaccine awareness (9.61 %; 95 % CI: 5.95–14.03, I2 =

= 99.0 %) than the Han population (20.17 %; 95 % CI: 16.42–24.20, I2

99.0 %) than the Han population (20.17 %; 95 % CI: 16.42–24.20, I2 =

= 98.3 %). Among different regions, the HPV vaccine awareness was higher in EDA (17.57 %; 95 % CI: 13.36–22.21, I2

98.3 %). Among different regions, the HPV vaccine awareness was higher in EDA (17.57 %; 95 % CI: 13.36–22.21, I2 =

= 98.0 %) and CLDA (17.78 %; 95 % CI: 12.18–24.19, I2

98.0 %) and CLDA (17.78 %; 95 % CI: 12.18–24.19, I2 =

= 97.6 %) than in WUDA (1.80 %; 95 % CI: 0.02–6.33, I2

97.6 %) than in WUDA (1.80 %; 95 % CI: 0.02–6.33, I2 =

= 98.9 %). Furthermore, 67.25 % (95 % CI: 58.75–75.21, I2

98.9 %). Furthermore, 67.25 % (95 % CI: 58.75–75.21, I2 =

= 99.8 %) of participants were willing to be vaccinated, while this number was lower for their daughters (60.32 %; 95 % CI: 51.25–69.04, I2

99.8 %) of participants were willing to be vaccinated, while this number was lower for their daughters (60.32 %; 95 % CI: 51.25–69.04, I2 =

= 99.2 %). The general adult population (64.72 %; 95 % CI: 55.57–73.36, I2

99.2 %). The general adult population (64.72 %; 95 % CI: 55.57–73.36, I2 =

= 99.2 %) was more willing to vaccinate their daughters than the parent population (33.78 %; 95 % CI: 26.26–41.74, I2

99.2 %) was more willing to vaccinate their daughters than the parent population (33.78 %; 95 % CI: 26.26–41.74, I2 =

= 88.3 %). Safety (50.46 %; 95 % CI: 40.00–60.89, I2

88.3 %). Safety (50.46 %; 95 % CI: 40.00–60.89, I2 =

= 96.6 %) was the main concern about vaccination among the adult population whereas the safety and efficacy (68.19 %; 95 % CI: 53.13–81.52, I2

96.6 %) was the main concern about vaccination among the adult population whereas the safety and efficacy (68.19 %; 95 % CI: 53.13–81.52, I2 =

= 98.6 %) were the main concerns for unwillingness to vaccinate their daughters.

98.6 %) were the main concerns for unwillingness to vaccinate their daughters.

Conclusions

Low HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge was observed among the Chinese population. HPV vaccine awareness differed across sexes, ethnicities, and regions. Given the limited quality and number of studies included, further research with improved study designis necessary.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12889-016-2873-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Background

Cervical cancer, one of the most common cancers observed in females [1], affects more than 529,000 annually around the world [2]. More than 85 % of the global cervical cancer burden occurs in developing countries [2], with 75,500 incidences reported annually in China. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the most important risk factor for cervical cancer [3]. Although a single HPV infection can easily be eliminated through the immune system, malignant transformation of cervical epithelial cells may be induced in a small proportion of women affected by persistent virus infection.

Vaccines have always been among the most effective interventions for infectious diseases [4]. Prophylactic vaccines of cervical cancer manufactured by Merck &Co. have been approved by FDA and have been commercially available since 2006 [5]. The approval of vaccines for the HPV increased the possibility of eradicating cervical cancer in the near future. However, it is noteworthy that awareness of HPV and the general attitude towards vaccination were crucial factors for acceptance of vaccination among the population. In addition, increasing number of studies addressing the hesitation to get vaccinated have been conducted in the recent years, portraying the challenging and dynamic period of indecisiveness concerning HPV vaccination [6].

The HPV vaccine has been widely introduced in the vaccination programs of Hong Kong, however, is not popularly accepted in Mainland China at present. In addition, despite the numerous published studies focusing on the topic of HPV and vaccination in recent years, there is no comprehensive information concerning the acceptance and obstacles associated with vaccination among the population of Mainland China. In order to develop a practical vaccination program in the future, it is imperative to assess the level of awareness and knowledge about HPV, and the general attitude towards HPV vaccination among the Chinese population, as they are important behavioral determinants that will ultimately affect the acceptance of vaccination among the Chinese population. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis in order to gain a better understanding of this issue that may help generate new ideas to make future generalization of HPV vaccination possible in China.

Methods

Search strategy

The meta-analysis was conducted in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [7]. The Chinese literature was searched using the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wan Fang Database and VIP Database for Chinese Technical Periodicals (VIP) using the keywords “HPV vaccine OR cervical vaccine”. The literature in English was searched using PubMed and EMBASE, and relevant studies were identified with the search terms “HPV OR cervical cancer” AND “vaccine OR vaccination OR immunization” AND “awareness OR knowledge OR acceptability OR acceptance OR willingness OR perception OR attitude OR recognition” AND “China OR Chinese.” The publication time was limited to 2006–2015, as HPV vaccine was introduced in the world in 2006. Data retrieval was supplemented by manually searching for the reference list of key reviews and references from retrieved studies. No language restriction was imposed.

Selection criteria

The inclusion criteria for the epidemiological studies were the following: (1)study involved at least one of the key terms “HPV vaccine awareness”, “knowledge”, and “acceptability”for any region of Mainland China (excluding studies conducted in Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macao due to differencesin socio-economic levels and health policies between these regions and Mainland China), (2) original data was available regardless of whether it was obtained directly from the article or traced from secondary data in the article. Studies that examining the effects of health educational interventions were excluded.

Data extraction

A data abstraction form was constructed after scanning the selected articles. For each included study, we extracted the following information: author, publication year, region, study instrument, study subject (age, sex and ethnicity), sampling method, sample size (N), the number of participants for the assessment of HPV vaccine awareness, knowledge, and acceptance, or the rate percentage proportions for these studied factors. We also extracted the reasons for unwillingness to be vaccinated if this information was available. The number of studied cases(n) and sample size(N) were the two necessary parameters for the calculation of the pooled rates of HPV vaccine awareness, knowledge, and acceptance of vaccination in the meta-analysis. In particular, the number of studied cases (n) was obtained directly from the original studies or by multiplying the sample sizes (N) with the proportions (%) associated with the investigated factors reported in the original studies.

Quality assessment

We employed a flexible appraisal scale suggested by Iain Crombie [8] for the assessment of the quality of cross-sectional studies. The scale contains seven indexes: (1) design is scientific, (2) data collection strategy is reasonable, (3) sample response rate is reported, (4) samples can represent the general population well, (5) the research purpose and method is reasonable, (6) the test efficiency is reported, (7) the statistical method is reasonable. For each index, the study was scored “1,” “0,”or “0.5” for “yes,” “no,”or “unclear,” respectively. The maximum score in the scale is 7 points, with scores of 6.0–7.0 points as grade A, scores of 4.0–5.5 points as grade B, and scores of less than 4.0 points as grade C.

Data analysis

We used “rate” to evaluate the studied items. The rate for HPV vaccine awareness was calculated by dividing the number of cases who were aware of HPV vaccine (n1) by the sample size (N); the rate for HPV vaccine knowledge was calculated by dividing the number of cases who knew the relationship between HPV (vaccine) and cervical cancer (n2) by the sample size (N); the rate for acceptance to be vaccinated was calculated by dividing the number of cases who were willing to get vaccinated (n3) by the sample size (N); the rate for acceptance of parents to vaccinate their daughters was calculated by dividing the number of cases who were willing to vaccinate their daughters (n4) by the sample size(N); the rate for reasons of unwillingness to be vaccinated was calculated by dividing the number of cases who gave a reason (n5) by the number of cases who were unwilling to be vaccinated (N-n3).

Meta-analysis was conducted using a random effects model. Given the requirement for normalization of single rate in meta-analysis, an arcsine transformation for the original rate was performed to meet the requirement [9]. Statistical heterogeneity among the studies was estimated by Chi-square test at the significance level of P <

< 0.10, and using the I-square (I2) statistic to quantify the heterogeneity of the results. Publication bias was detected by Egger’s test (P

0.10, and using the I-square (I2) statistic to quantify the heterogeneity of the results. Publication bias was detected by Egger’s test (P <

< 0.05 was considered statistically significant) [10]. R statistical software (Version 2.11.1) was used for all the calculations.

0.05 was considered statistically significant) [10]. R statistical software (Version 2.11.1) was used for all the calculations.

Consent statement

As this study was a meta-analysis, we did not include any humans and animals. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Results

Screening process

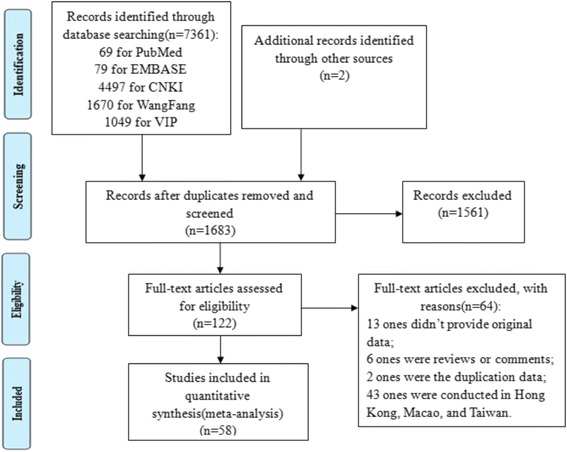

Our search returned 1683 articles. A flow diagram of the selection process is shown in Fig. 1. Of the original articles, 1561 articles that were not clearly relevant to the analysis were excluded. After diligently reading the full text of the remaining 122 studies, 64 studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Consequently, 58 observational studies [11–68] were included for the meta-analysis.

Study characteristics

We included 58 individual studies [11–68] representing 19 provinces and municipalities in Mainland China (Table 1). Eighty-three thousand, seven hundred and five participants were interviewed, the majority of which were females. Nearly all the studies were published after 2009, and 38 studies were published in the recent three years. A questionnaire survey was conducted for all the studies included in the analysis, 12 of which were interview-administered, while nine were self-administered questionnaires (Table 1). After conducting a quality assessment on the included studies, 51 studies were categorized as grade A, and seven as grade B (Table 2).

Table 1

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Regiona | Study instrumentb | N | Population (age) | F/(F + + M) M) | Sampling method | Ethnicity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range |

| Groupc | |||||||

| Huang He, 2013 [33] | CLDA | Q | 470 | NA | 20.09 ± ± 1.33 1.33 | CS | 0.504 | Randomized | Han |

| Ma Xiaojing, 2013 [12] | EDA | IAQ | 1451 | NA | 45.1 ± ± 10.8 10.8 | A | 1 | Convenience | Mixed |

| He Mei, 2011 [41] | CLDA | Q | 10,611 | 18–82 | 38.02 ± ± 9.57 9.57 | A | 1 | Convenience | Han |

| Cui Bo, 2010 [13] | EDA | IAQ | 1160 | 15–59 | 35.66 ± ± 11.72 11.72 | A | 1 | Randomized | Mixed |

| He Xin, 2010 [29] | NA | SAQ | 903 | 16–26 | 19.14 ± ± 1.01 1.01 | CS | 0.52 | Cluster | Han |

| Xu Jing, 2014 [11] | CLDA | Q | 353 | 18–24 | 20.96 | CS | 0.683 | Cluster | Han |

| Feng Suwen, 2010 [46] | EDA | Q | 1432 | 18–50 | 35.3 | A | 1 | Cluster | Han |

| Yan Jun, 2013 [43] | WUDA | IAQ | 1681 | 30–49 | NA | A | 1 | Cluster | Han |

| Long Xiange, 2011 [21] | EDA | Q | 286 | NA | 18.5 | CS | NA | Convenience | Han |

| Hu Haishan, 2014 [28] | EDA | Q | 542 | 31–60 | 41.57 ± ± 5.77 5.77 | P | 0.685 | Cluster | Mixed |

| Wu Ying, 2011 [25] | EDA | IAQ | 489 | 15–50 | NA | A | 1 | Randomized | Han |

| Li Juan, 2011 [14] | EDA | IAQ | 160 | NA | 36.55 ± ± 9.59 9.59 | A | 0.738 | Randomized | Mixed |

| Fan Baojian, 2009 [23] | EDA | Q | 962 | 19–72 | 43.38 ± ± 8.29 8.29 | A | 1 | Cluster | Mixed |

| Xiao Wei, 2009 [45] | NA | Q | 378 | 21–74 | 36.19 | A | 1 | Convenience | Han |

| Wang Xuemin, 2012 [15] | WUDA | IAQ | 2269 | 25–73 | 43.54 ± ± 7.67 7.67 | A | 1 | Cluster | Han |

| Shao Shujuan, 2013 [17] | EDA | Q | 594 | ≤60 | 36.02 ± ± 10.54 10.54 | A | 1 | Randomized | Han |

| Xu Wenyu, 2013 [18] | EDA | Q | 3000 | 20–30 | A | 1 | Convenience | Han | |

| Ma Dong, 2013 [40] | NA | Q | 258 | 17–24 | 19.23 ± ± 0.89 0.89 | CS | 0.55 | Cluster | Han |

| Zhou Lixia, 2011 [42] | EDA | IAQ | 752 | 16–55 | NA | A | 1 | Randomized | Han |

| Huang Yanhua, 2014 [39] | EDA | Q | 378 | 15–50 | NA | A | 0.5 | Randomized | Han |

| Wang Haiqiu, 2011 [31] | CLDA | Q | 257 | 20–53 | 33.6 ± ± 0.5 0.5 | A | 1 | Randomized | Han |

| Ma Dong, 2012 [30] | CLDA | Q | 198 | 20–54 | 31.8 ± ± 7.0 7.0 | A | 0.89 | Convenience | Han |

| Yao Chenglian, 2012 [19] | EDA | Q | 1198 | 16–65 | NA | A | 1 | Convenience | Han |

| Xamxinuer Ablimit, 2009 [26] | WUDA | Q | 245 | 23–85 | 48.8 | A | 1 | Convenience | Mixed |

| Xu Lina, 2013 [22] | NA | Q | 1666 | 15–59 | NA | A | 1 | Randomized | Han |

| Zhang Hui, 2014 [37] | CLDA | Q | 341 | 32–50 | 39.56 ± ± 3.47 3.47 | P | 0.63 | Cluster | Han |

| Yu Jing, 2013 [44] | CLDA | Q | 750 | 15–59 | 35.75 ± ± 9.4 9.4 | A | 1 | Randomized | Han |

| Guzalnur Abduxkur, 2012 [32] | WUDA | IAQ | 560 | NA | NA | A | 0 | Convenience | Mixed |

| Cai Jing, 2013 [24] | WUDA | Q | 648 | NA | NA | A | 0 | Randomized | Mixed |

| Li Li, 2010 [27] | WUDA | Q | 1989 | 16–59 | NA | A | 1 | Cluster | Mixed |

| Ying Wen, 2014 [35] | CLDA | Q | 1878 | 17–25 | NA | CS | 0.679 | Randomized | Mixed |

| Zhang Shaokai, 2013 [38] | NA | Q | 2895 | NA | 40.4 ± ± 4.68 4.68 | P | 0.628 | Cluster | Mixed |

| Wang Shaoming, 2014 [20] | NA | Q | 3368 | NA | 19.82 ± ± 1.31 1.31 | CS | 0.51 | Randomized | Mixed |

| Yan Hong, 2013 [16] | EDA | SAQ | 360 | 18–36 | 25.1 ± ± 3.5 3.5 | A | 1 | Convenience | Mixed |

| Li Jing, 2009 [34] | NA | Q | 6024 | 14–59 | 34.6 ± ± 1.7 1.7 | A | 1 | Cluster | Han |

| Zhao Fanghui, 2012 [36] | NA | Q | 11,681 | NA | 34 ± ± 11.8 11.8 | A | 0.705 | Randomized | Han |

Ayizuoremu · · mutailipu, 2015 [64] mutailipu, 2015 [64] | WUDA | Q | 1900 | 16–60 | NA | A | 1 | Cluster | Mixed |

| Zeng Xiaomin, 2015 [55] | EDA | SAQ | 2004 | NA | NA | C | 1 | Cluster | Han |

| Wang Ling, 2015 [49] | CLDA | Q | 125 | 18–23 | 20.5 | C | 1 | Convenience | Han |

| Liu Qiong, 2015 [57] | CLDA | Q | 590 | 14–20 | 15.34 ± ± 1.3 1.3 | C | 0.91 | Convenience | Han |

| She Qian, 2015 [59] | EDA | IAQ | 209 | 19–45 | NA | A | 1 | Randomized | Han |

| Chen Ling, 2015 [50] | NA | IAQ | 300 | 21–28 | 24 ± ± 0.8 0.8 | C | 1 | Randomized | Han |

| Cheng Lihong, 2015 [51] | EDA | Q | 1256 | 19–55 | NA | A | 1 | Convenience | Han |

| Zhu Qiaoyang, 2015 [58] | EDA | Q | 362 | 18–66 | 42.2 ± ± 6.3 6.3 | A | 1 | Convenience | Han |

| Lei Juhong, 2015 [61] | EDA | Q | 300 | 15–64 | NA | A | NA | Randomized | Han |

| Zhao Bixia, 2015 [63] | CLDA | Q | 138 | 25–50 | NA | A | NA | Convenience | Han |

| Xie Wenliu, 2015 [48] | CLDA | Q | 192 | 15–70 | NA | A | 0.51 | Convenience | Han |

| Zhou Yanqiu, 2015 [47] | EDA | SAQ | 600 | ≥21 | NA | A | NA | Convenience | Han |

| Meng Liping, 2015 [60] | EDA | SAQ | 1652 | 20–65 | 38.09 ± ± 8.21 8.21 | A | NA | Cluster | Han |

| Zou Huachun, 2015 [53] | EDA | SAQ | 368 | NA | NA | A | 0 | Convenience | Han |

| Zou Huachun, 2015 [52] | EDA | SAQ | 351 | 16–25 | NA | C | 0.524 | Cluster | Mixed |

| Gu Can, 2015 [62] | CLDA | Q | 117 | 19–23 | 20.8 ± ± 1 1 | C | 1 | Convenience | Han |

| Wang Wei, 2015 [56] | EDA | Q | 360 | NA | 41.77 ± ± 3.33 3.33 | P | 0.522 | Cluster | Mixed |

| Abida Abudukadeer, 2015 [65] | WUDA | IAQ | 5000 | 20–51 | NA | A | 1 | Convenience | Mixed |

| Zhang Shaokai, 2015 [54] | CLDA | Q | 2895 | NA | 40.4 ± ± 4.68 4.68 | P | 0.628 | Cluster | Mixed |

| Pan Xiongfei, 2015 [66] | CLDA | Q | 1878 | 17–25 | 20.8 ± ± 1.3 1.3 | C | 0.679 | Convenience | Mixed |

| Fu Chunjing, 2015 [67] | CLDA | SAQ | 605 | 18–26 | 21.6 ± ± 1 1 | C | 0.689 | Randomized | Mixed |

| Hu Shangying, 2105 [68] | EDA | IAQ | 316 | 18–25 | 23.2 ± ± 1.7 1.7 | C | 1 | Cluster | Han |

a EDA eastern developed areas, such as Beijing (city), Tianjin (city), Shanghai (city), Dalian (city), Shandong(province), Jinan(city), Zhejiang(province), Hangzhou(city), Ningbo(city), Jiangsu(province), Wuxi(city), Guangdong(province), Guangzhou(city), Shenzhen(city), Dongguan(city), Zhongshan(city), CLDA central less derdeveloped areas, such as Liaoning(province), Tangshan(city), Xi’an(city), Wuhan(city), Hunan(province), Hengyang(city), Chongqing(city), Chengdu(city), Yunnan(province), National, southwest China, WUDA western or undeveloped areas, such as Gansu, Xinjiang and Shanxi

b IAQ interview-administered questionnaire, SAQ self-administered questionnaire, N not specified questionnaire

c A adults, P parents, CS college students

NA not available

Table 2

Quality assessment of included studies

| Studies | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Scores | Grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang He, 2013 [33] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Ma Xiaojing, 2013 [12] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| He Mei, 2011 [41] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | B |

| Cui Bo, 2010 [13] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| He Xin, 2010 [29] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Xu Jing, 2014 [11] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Feng Suwen, 2010 [46] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Yan Jun, 2013 [43] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Long Xiange, 2011 [21] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | B |

| Hu Haishan, 2014 [28] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Wu Ying, 2011 [25] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Li Juan, 2011 [14] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Fan Baojian, 2009 [23] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Xiao Wei, 2009 [45] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | B |

| Wang Xuemin, 2012 [15] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Shao Shujuan, 2013 [17] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | B |

| Xu Wenyu, 2013 [18] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Ma Dong, 2013 [40] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Zhou Lixia, 2011 [42] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Huang Yanhua, 2014 [39] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Wang Haiqiu, 2011 [31] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Ma Dong, 2012 [30] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Yao Chenglian, 2012 [19] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | B |

| Xamxinuer Ablimit, 2009 [26] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | B |

| Xu Lina, 2013 [22] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Zhang Hui,2014 [37] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Yu Jing, 2013 [44] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Guzalnur Abduxkur, 2012 [32] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | B |

| Cai Jing, 2013 [24] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Li Li, 2010 [27] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Ying Wen, 2014 [35] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Zhang Shaokai, 2013 [38] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Wang Shaoming, 2014 [20] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Yan Hong, 2013 [16] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Li Jing, 2009 [34] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Zhao Fanghui, 2012 [36] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

Ayizuoremu · · mutailipu, 2015 [64] mutailipu, 2015 [64] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Zeng Xiaomin, 2015 [55] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Wang Ling, 2015 [49] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Liu Qiong, 2015 [57] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| She Qian, 2015 [59] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Chen Ling, 2015 [50] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Cheng Lihong, 2015 [51] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Zhu Qiaoyang, 2015 [58] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Lei Juhong, 2015 [61] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Zhao Bixia, 2015 [63] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Xie Wenliu, 2015 [48] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Zhou Yanqiu, 2015 [47] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Meng Liping, 2015 [60] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Zou Huachun, 2015 [53] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Zou Huachun, 2015 [52] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Gu Can, 2015 [62] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Wang Wei, 2015 [56] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Abida Abudukadeer, 2015 [65] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Zhang Shaokai, 2015 [54] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

| Pan Xiongfei, 2015 [66] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Fu Chunjing, 2015 [67] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | A |

| Hu Shangying, 2105 [68] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | A |

For the second index; “data collection strategy”, we considered the study as reasonable when it satisfied one of the following criteria: 1) study purpose and survey contents were explained to participants before the survey, 2) investigators reviewed the questionnaire in terms of the clarity of language and completeness of the questionnaire

For the fourth index, “representativeness of the sample,” we recognized the sample as a good representative when it met one of the following requirements: 1) specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were provided, 2) a reasonable sampling method was used

Awareness and knowledge of HPV vaccine

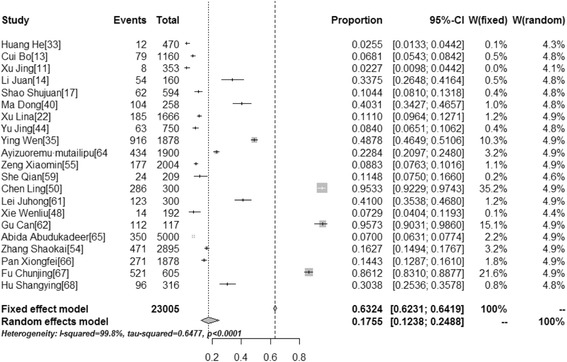

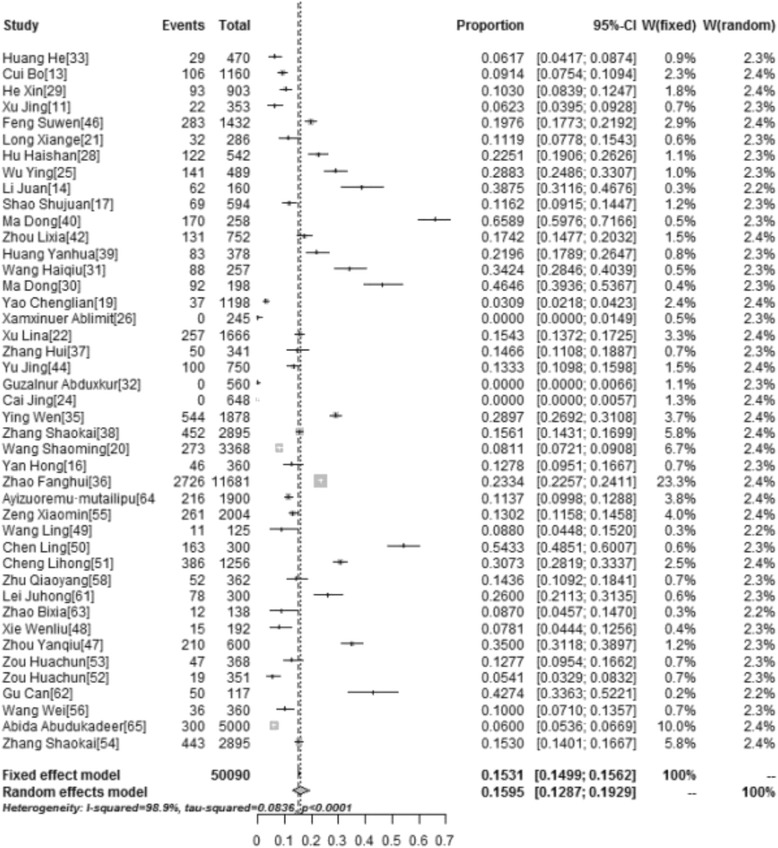

Awareness and knowledge of HPV vaccination among different populations were reported in 43 and 21 studies, respectively. The pooled awareness rate and knowledge rate concerning HPV vaccination was 15.95 % (95 % CI: 12.87–19.29, I2 =

= 98.9 %), and 17.55 % (95 % CI: 12.38–24.88, I2

98.9 %), and 17.55 % (95 % CI: 12.38–24.88, I2 =

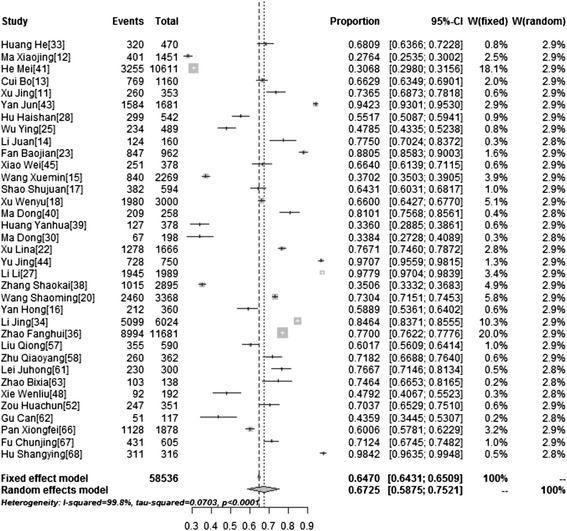

= 99.8 %), respectively (Table 3). Figures Figures22 and and33 show forest plots of meta-analysis for HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge in mainland China.

99.8 %), respectively (Table 3). Figures Figures22 and and33 show forest plots of meta-analysis for HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge in mainland China.

Table 3

The results of pooled rates of studied items (Supplementary Material: Additional file 1: "Availability of Data and Materials")

| Studied items | No. of studies | Pooled rates(95 % CI) | Heterogeneity (I 2,%) | Publication bias(P value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness | 43 | 15.95 (12.87–19.29) (12.87–19.29) | 98.9 | >0.05 |

| Knowledge | 21 | 17.55 (12.38–24.88) (12.38–24.88) | 99.8 | >0.05 |

| Acceptability | 35 | 67.25 (58.75–75.21) (58.75–75.21) | 99.8 | >0.05 |

| Reasons for unwillingness to be HPV vaccinated | ||||

Assumed low risk Assumed low risk | 14 | 33.63 (27.50–40.05) (27.50–40.05) | 97.2 | >0.05 |

Limited use to date Limited use to date | 14 | 36.31 (29.67–43.22) (29.67–43.22) | 97.7 | >0.05 |

Safety Safety | 10 | 50.46 (40.00–60.89) (40.00–60.89) | 96.6 | >0.05 |

Efficacy Efficacy | 14 | 30.18 (23.96–36.79) (23.96–36.79) | 97.3 | >0.05 |

Vaccine source Vaccine source | 11 | 32.17 (21.14–43.30) (21.14–43.30) | 99.2 | >0.05 |

High price High price | 6 | 23.72 (13.64–35.59) (13.64–35.59) | 98.2 | >0.05 |

| Acceptability (for daughters) | 12 | 60.32 (51.25–69.04) (51.25–69.04) | 99.2 | >0.05 |

| Reasons for unwillingness of parents to vaccinate their daughters | ||||

Limited use to date Limited use to date | 4 | 32.61 (22.03–44.18) (22.03–44.18) | 94.5 | >0.05 |

Safety and efficacy Safety and efficacy | 7 | 68.19 (53.13–81.52) (53.13–81.52) | 98.6 | >0.05 |

Vaccine source Vaccine source | 7 | 17.24 (13.87–20.90) (13.87–20.90) | 82.8 | >0.05 |

Too young to vaccinate Too young to vaccinate | 7 | 28.37 (13.69–45.90) (13.69–45.90) | 99 | >0.05 |

The pooled rate and 95 % CI are from random effects model

Forest Plot of meta-analysis for HPV vaccine awareness in mainland China, the pooled rate and 95 % CI in the article are from random effects model due to significant heterogeneity which was measured by I 2 statistics

Acceptability of HPV vaccination

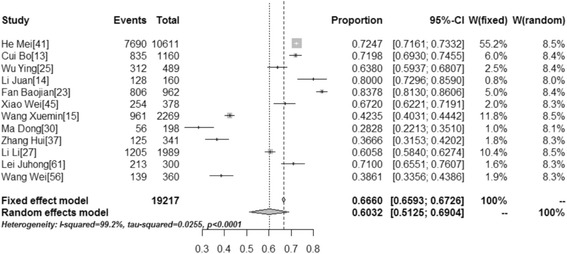

We explored the acceptability of HPV vaccination for individuals and their daughters. Thirty-five studies addressed participants’ willingness to be vaccinated, while 12 studies addressed the willingness of parents to get their daughters vaccinated. We found that the willingness of participants to be vaccinated was 67.25 % (95 % CI: 58.75–75.21, I2 =

= 99.8 %) while their willingness to get their daughters vaccinated was 60.32 % (95 % CI: 51.25–69.04, I2

99.8 %) while their willingness to get their daughters vaccinated was 60.32 % (95 % CI: 51.25–69.04, I2 =

= 99.2 %) (Table 3). Figures Figures44 and and55 show forest plots of meta-analysis for acceptability of HPV vaccination (for themselves and their daughters) in mainland China.

99.2 %) (Table 3). Figures Figures44 and and55 show forest plots of meta-analysis for acceptability of HPV vaccination (for themselves and their daughters) in mainland China.

Forest Plot of meta-analysis for acceptability of HPV vaccination(for themselves) in mainland China, the pooled rate and 95 % CI in the article are from random effects model due to significant heterogeneity which was measured by I 2 statistics

Reasons for unwillingness to be HPV vaccinated

Reasons for the unwillingness of individuals to be HPV vaccinated varied across studies. Nineteen studies explored reasons for participants’ reluctance to HPV vaccination. Among participants who were unwilling to be vaccinated, 33.63 % (95 % CI: 27.50–40.05, I2 =

= 97.2 %) respondents believed that they had a low risk of developing HPV infection, genital warts, or even cervical cancer. Other respondents were worried about the limited use of HPV vaccine in China (36.31 %; 95 % CI: 29.67–43.22, I2

97.2 %) respondents believed that they had a low risk of developing HPV infection, genital warts, or even cervical cancer. Other respondents were worried about the limited use of HPV vaccine in China (36.31 %; 95 % CI: 29.67–43.22, I2 =

= 97.7 %). Respondents who were concerned with the safety and the efficacy of HPV vaccination accounted for 50.46 % (95 % CI: 40.00–60.89, I2

97.7 %). Respondents who were concerned with the safety and the efficacy of HPV vaccination accounted for 50.46 % (95 % CI: 40.00–60.89, I2 =

= 96.6 %) and 30.18 % (95 % CI: 23.96–36.79, I2

96.6 %) and 30.18 % (95 % CI: 23.96–36.79, I2 =

= 97.3 %), respectively. Participants who questioned the source of the vaccine and communicated a concern regarding the high price of the vaccine were 32.17 % (95 % CI: 21.14–43.30, I2

97.3 %), respectively. Participants who questioned the source of the vaccine and communicated a concern regarding the high price of the vaccine were 32.17 % (95 % CI: 21.14–43.30, I2 =

= 99.2 %) and 23.72 % (95 % CI: 13.64–35.59, I2

99.2 %) and 23.72 % (95 % CI: 13.64–35.59, I2 =

= 98.2 %), respectively (Table 3).

98.2 %), respectively (Table 3).

Reasons for unwillingness of parents to vaccinate their daughters

Seven studies explored the reasons for participants’ reluctance to get their daughters HPV vaccinated. Among them, 32.61 % (95 % CI: 22.03–44.18, I2 =

= 94.5 %) respondents were concerned regarding the limited use of HPV vaccine in China to date. Some respondents (68.19 %; 95 % CI: 53.13–81.52, I2

94.5 %) respondents were concerned regarding the limited use of HPV vaccine in China to date. Some respondents (68.19 %; 95 % CI: 53.13–81.52, I2 =

= 98.6 %) doubted the safety and efficacy of the HPV vaccine. Only 17.24 % (95 % CI: 13.87–20.90, I2

98.6 %) doubted the safety and efficacy of the HPV vaccine. Only 17.24 % (95 % CI: 13.87–20.90, I2 =

= 82.8 %) of the respondents doubted the vaccine source. In addition, 28.37 % (95 % CI: 13.69–45.90, I2

82.8 %) of the respondents doubted the vaccine source. In addition, 28.37 % (95 % CI: 13.69–45.90, I2 =

= 99 %) of the respondents considered their children to be too young for vaccination (Table 3).

99 %) of the respondents considered their children to be too young for vaccination (Table 3).

Subgroup analysis and meta-regression

A subgroup analysis indicated that the awareness of HPV vaccine differed across sexes (P =

= 0.033), ethnicities (P

0.033), ethnicities (P =

= 0.017), and regions (P

0.017), and regions (P =

= 0.031). We observed a higher HPV vaccine awareness among the female population (17.39 %; 95 % CI: 13.06–22.20, I2

0.031). We observed a higher HPV vaccine awareness among the female population (17.39 %; 95 % CI: 13.06–22.20, I2 =

= 98.8 %) and mixed population (18.55 %; 95 % CI:14.14–23.42, I2

98.8 %) and mixed population (18.55 %; 95 % CI:14.14–23.42, I2 =

= 98.8 %) relative to the male population (1.82 %; 95 % CI: 0.50–11.20, I2

98.8 %) relative to the male population (1.82 %; 95 % CI: 0.50–11.20, I2 =

= 98.5 %). We also found that populations of mixed ethnicity have lower HPV vaccine awareness (9.61 %; 95 % CI: 5.95–14.03, I2

98.5 %). We also found that populations of mixed ethnicity have lower HPV vaccine awareness (9.61 %; 95 % CI: 5.95–14.03, I2 =

= 99.0 %) compared to population of Han (20.17 %; 95 % CI: 16.42–24.20, I2

99.0 %) compared to population of Han (20.17 %; 95 % CI: 16.42–24.20, I2 =

= 98.3 %). Among different regions, the HPV vaccine awareness was higher in EDA (17.57 %; 95 % CI: 13.36–22.21, I2

98.3 %). Among different regions, the HPV vaccine awareness was higher in EDA (17.57 %; 95 % CI: 13.36–22.21, I2 =

= 98.0 %) and CLDA (17.78 %; 95 % CI: 12.18–24.19, I2

98.0 %) and CLDA (17.78 %; 95 % CI: 12.18–24.19, I2 =

= 97.6 %) compared to WUDA (1.80 %; 95 % CI: 0.02–6.33, I2

97.6 %) compared to WUDA (1.80 %; 95 % CI: 0.02–6.33, I2 =

= 98.9 %). Subgroup analysis revealed that acceptability to be vaccinated varied among studies conducted using different sampling methods (P

98.9 %). Subgroup analysis revealed that acceptability to be vaccinated varied among studies conducted using different sampling methods (P =

= 0.022). The acceptability of vaccination among cluster-sampled population (72.45 %; 95 % CI: 52.22–88.76, I2

0.022). The acceptability of vaccination among cluster-sampled population (72.45 %; 95 % CI: 52.22–88.76, I2 =

= 99.9 %) was higher compared to the convenience-sampled population (53.53 %; 95 % CI: 41.95–64.92, I2

99.9 %) was higher compared to the convenience-sampled population (53.53 %; 95 % CI: 41.95–64.92, I2 =

= 99.5 %). The subgroup analysis showed that acceptability for parents to vaccinate their daughters differed across ages (P

99.5 %). The subgroup analysis showed that acceptability for parents to vaccinate their daughters differed across ages (P =

= 0.014) and sampling methods (P

0.014) and sampling methods (P =

= 0.038). General adult population (64.72 %; 95 % CI: 55.57–73.36, I2

0.038). General adult population (64.72 %; 95 % CI: 55.57–73.36, I2 =

= 99.2 %) was more willing to vaccinate their daughters than parent population (33.78 %; 95 % CI: 26.26–41.74, I2

99.2 %) was more willing to vaccinate their daughters than parent population (33.78 %; 95 % CI: 26.26–41.74, I2 =

= 88.3 %). Randomized sampling method showed a higher acceptability for vaccination of daughters (72.75 %; 95 % CI: 67.66–77.56, I2

88.3 %). Randomized sampling method showed a higher acceptability for vaccination of daughters (72.75 %; 95 % CI: 67.66–77.56, I2 =

= 92.9 %) compared to cluster sampling method (48.54 %; 32.37–64.88, I2

92.9 %) compared to cluster sampling method (48.54 %; 32.37–64.88, I2 =

= 99.4 %) (Table (Table4).4). Meta-regression analysis was also performed but failed to explain the source of heterogeneity.

99.4 %) (Table (Table4).4). Meta-regression analysis was also performed but failed to explain the source of heterogeneity.

Table 4

The results of subgroup analysis by characteristics of the population

| Subgroups | No. of studies | Incidence % (95 % CI) | I 2 (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness (all studies) | ||||

Age Age | 0.698 | |||

CS CS | 12 | 19.07 (11.72,27.71) (11.72,27.71) | 99.0 | |

A A | 27 | 15.14 (11.11,19.68) (11.11,19.68) | 99.1 | |

P P | 5 | 15.62 (13.13,18.28) (13.13,18.28) | 85.4 | |

Sex Sex | 0.033 | |||

Fa Fa

| 23 | 17.39 (13.06,22.20) (13.06,22.20) | 98.8 | |

F, Ma F, Ma

| 17 | 18.55 (14.14,23.42) (14.14,23.42) | 98.8 | |

Mb Mb

| 3 | 1.82 (0.50,11.20) (0.50,11.20) | 98.5 | |

Sample method Sample method | 0.504 | |||

Randomized Randomized | 16 | 18.88 (13.60,24.80) (13.60,24.80) | 99.0 | |

Cluster Cluster | 16 | 13.74 (7.66,21.24) (7.66,21.24) | 99.1 | |

Convenience Convenience | 12 | 16.03 (12.12,20.36) (12.12,20.36) | 97.7 | |

Ethnicity Ethnicity | 0.017 | |||

Han Han | 29 | 20.17 (16.42,24.20) (16.42,24.20) | 98.3 | |

Mixed Mixed | 15 | 9.61 (5.95,14.03) (5.95,14.03) | 99.0 | |

Region Region | 0.031 | |||

EDAa EDAa

| 20 | 17.57 (13.36,22.21) (13.36,22.21) | 98.0 | |

CLDAa CLDAa

| 12 | 17.78 (12.18,24.19) (12.18,24.19) | 97.6 | |

WUDAb WUDAb

| 5 | 1.80 (0.02,6.33) (0.02,6.33) | 98.9 | |

| Knowledge (all studies) | ||||

Age Age | 0.171 | |||

CS CS | 10 | 40.94 (20.11,63.64) (20.11,63.64) | 99.8 | |

A A | 11 | 15.52 (10.22,21.69) (10.22,21.69) | 98.7 | |

P P | 1 | 16.27 | ||

Sex Sex | 0.841 | |||

F F | 13 | 27.2 (17.56,38.07) (17.56,38.07) | 99.5 | |

F, M F, M | 9 | 24.51 (10.28,42.45) (10.28,42.45) | 99.7 | |

M M | 0 | |||

Sample method Sample method | 0.757 | |||

Randomized Randomized | 11 | 29.87 (13.02,50.19) (13.02,50.19) | 99.7 | |

Cluster Cluster | 7 | 19.16 (12.41,26.98) (12.41,26.98) | 98.7 | |

Convenience Convenience | 0 | |||

Ethnicity Ethnicity | 0.893 | |||

Han Han | 14 | 25.40 (14.41,38.28) (14.41,38.28) | 99.4 | |

Mixed Mixed | 8 | 27.46 (13.87,43.62) (13.87,43.62) | 99.8 | |

Region Region | 0.837 | |||

EDA EDA | 8 | 19.58 (11.76,28.82) (11.76,28.82) | 98.6 | |

CLDA CLDA | 9 | 27.80 (11.97,47.20) (11.97,47.20) | 99.7 | |

WUDA WUDA | 2 | 13.96 (2.44,32.70) (2.44,32.70) | 99.7 | |

| Acceptability (for themselves) | ||||

Age Age | 0.338 | |||

CS CS | 10 | 71.71 (64.06,78.77) (64.06,78.77) | 97.9 | |

A A | 24 | 64.82 (52.80,75.95) (52.80,75.95) | 99.9 | |

P P | 2 | 44.92 (26.00,64.63) (26.00,64.63) | 98.7 | |

Sex Sex | 0.208 | |||

F F | 21 | 68.50 (54.40,81.05) (54.40,81.05) | 99.9 | |

F, M F, M | 15 | 61.65 (52.47,70.43) (52.47,70.43) | 99.4 | |

M M | 0 | |||

Sample method Sample method | 0.022 | |||

Randomized Randomized | 12 | 70.42 (63.63,76.79) (63.63,76.79) | 98.8 | |

Clustera Clustera

| 12 | 72.45 (52.22,88.76) (52.22,88.76) | 99.9 | |

Convenienceb Convenienceb

| 12 | 53.53 (41.95,64.92) (41.95,64.92) | 99.5 | |

Ethnicity Ethnicity | 0.939 | |||

Han Han | 24 | 65.14 (53.62,75.83) (53.62,75.83) | 99.8 | |

Mixed Mixed | 12 | 66.76 (51.25,80.60) (51.25,80.60) | 99.7 | |

Region Region | 0.407 | |||

EDA EDA | 14 | 65.31 (54.68,75.21) (54.68,75.21) | 99.2 | |

CLDA CLDA | 12 | 64.10 (46.56,79.87) (46.56,79.87) | 99.7 | |

WUDA WUDA | 3 | 82.15 (35.87,99.68) (35.87,99.68) | 99.9 | |

| Acceptability (for daughters) | ||||

Age Age | 0.014 | |||

CS CS | 1 | 38.61 | ||

Aa Aa

| 10 | 64.72 (55.57,73.36) (55.57,73.36) | 99.2 | |

Pb Pb

| 3 | 33.78 (26.26,41.74) (26.26,41.74) | 88.3 | |

Sex Sex | 0.068 | |||

F F | 8 | 67.04 (57.46,75.96) (57.46,75.96) | 99.2 | |

F, M F, M | 4 | 46.06 (27.07,65.66) (27.07,65.66) | 97.6 | |

M M | 0 | |||

Sample method Sample method | 0.038 | |||

Randomizeda Randomizeda

| 5 | 72.75 (67.66,77.56) (67.66,77.56) | 92.9 | |

Clusterb Clusterb

| 6 | 48.54 (32.37,64.88) (32.37,64.88) | 99.4 | |

Convenience Convenience | 3 | 56.36 (34.63,76.88) (34.63,76.88) | 98.8 | |

Ethnicity Ethnicity | 0.253 | |||

Han Han | 8 | 57.84 (47.89,67.48) (47.89,67.48) | 99.5 | |

Mixed Mixed | 6 | 61.04 (44.36,76.50) (44.36,76.50) | 99.3 | |

Region Region | 0.689 | |||

EDA EDA | 6 | 59.03 (41.51,75.44) (41.51,75.44) | 98.9 | |

CLDA CLDA | 4 | 56.36 (37.18,74.60) (37.18,74.60) | 99.3 | |

WUDA WUDA | 2 | 51.49 (33.81,68.97) (33.81,68.97) | 99.3 | |

There were significant differences in groups with different letters (P <

< 0.05)

0.05)

The pooled rate and 95 % CI are from random effects model

A adults, P parents, CS college students

Publication bias

Egger’s test was performed to assess the publication bias. The results did not show evidence of publication bias (all P >

> 0.05) (Table 3).

0.05) (Table 3).

Discussion

This is the first meta-analysis study conducted for the assessment of HPV vaccine related awareness, knowledge and acceptability among the Chinese population. Our meta-analysis identified low awareness (15.95 %) and low knowledge (17.55 %) of HPV vaccine among the Chinese population. The rates were lower compared to many other countries. Studies conducted in Turkey showed that HPV vaccine awareness among undergraduate students in Turkey was 44.5 % [69], while 27.9 % of respondents knew that HPV vaccines can prevent cervical cancer [70]. In addition, the HPV vaccine awareness rates were found to be in the 67.1–71.3 % range in the USA, UK and Australia [71]. The higher awareness rate of HPV vaccine and related knowledge in these countries may be due to the intervention programs and increased media coverage [72–74]. The low level of HPV vaccine awareness may greatly influence its promotion in China. In subgroup analysis, the pooled rate of HPV vaccine awareness was higher among females (17.39 %) and mixed population (18.55 %) compared to the male population (1.82 %). In the Chinese tradition, males play an important role in decision-making in the family, the low awareness of HPV vaccine may influence the acceptability of vaccination for their daughters [53]. We also found that populations of mixed ethnicity have lower HPV vaccine awareness rates (9.61 %) compared to population of Han (20.17 %). In addition, a study in England showed that HPV vaccine awareness was lower among ethnic minority groups (6–18 %) compared to white women (39 %), and that ethnic minorities have lower uptake of vaccination [75, 76]. These findings suggest that potential ethnic inequalities and cultural barriers should be identified for the prevention of cervical cancer [76]. Among different regions, HPV vaccine awareness was higher in EDA (17.57 %) and CLDA (17.78 %) compared to WUDA (1.80 %). In fact, eastern and central areas benefit from abundant healthcare resources and strong economies compared to western or some undeveloped regions. The difference between different geographical areas in China revealed that socio-economic status is a factor that influences the HPV vaccine awareness.

In addition, we found a relative high acceptability of HPV vaccination (67.25 % for themselves and 60.32 % for daughters). However, this rate declines in the high-end of the level across the world (59 % to 100 %) [77–79]. In subgroup analysis, the acceptability to be vaccinated among cluster-sampled population (72.45 %) was higher than convenience-sampled population (53.53 %), and randomized sampling method (72.75 %) showed a higher acceptability for vaccination of daughters compared to cluster sampling method (48.54 %). This is an indication that acceptability of vaccination among the population may be higher if rigorous sampling methods, such as randomized sampling method, are used. Subgroup analysis showed that parental acceptability of vaccination (33.78 %) was lower compared to the general adult population (64.72 %). Moreover, the acceptability rate (33.78 %) was lower compared to similar studies conducted in other countries. A similar study in Sweden reported that 76 % of participated parents were willing to vaccinate their daughters [80]. In addition, studies in Africa showed that parents with good knowledge of HPV vaccine were more willing to vaccinate their children than those with poor knowledge [81]. Population’s attitude and acceptance toward HPV vaccination is an important determinant for the success of HPV vaccine promotion in China in the future, which necessitates, the identification of the main obstacles concerning the acceptability of vaccination among the Chinese population.

The primary obstacles concerning vaccination acceptability for responders were the safety and efficacy of the HPV vaccine. HPV vaccines have been proved safe and efficient against HPV infection [82, 83]. WHO recommended HPV vaccination for both young women and men before the onset of sexual activity [84]. In recent years, many studies have investigated HPV vaccine safety and adverse events. Both of the HPV vaccines are related to high rates of injection site reactions, such as pain, swelling and redness which maybe due to a possible VLP-related (VLP, Virus-like particles) inflammation process [85]. However, these outcomes are usually for a short duration and recovery is quick [86]. Most reported adverse events were mild or moderate in intensity [87–98], and serious vaccination-related adverse events, such as anaphylaxis, are rare [86]. Similarly, other studies reported that there were no vaccine related deaths in the included studies [99]. Furthermore, a review concluded that the prophylactic vaccines against HPV appear safe based on the assessment of reported adverse events by governmental databases and independent researchers [100].

Sufficient scientific evidence has clarified many of the misunderstandings related to vaccine safety, however, the concerns related to vaccination are still increasing [101]. Public confidence in vaccines is particularly important. If vaccination is not trusted, the hesitance to be vaccinated may lead to delay and refusal, resulting in the disintegration of related research and delivery programs, and may even result in disease outbreak [102, 103]. The segmented information from media may amplify vaccine related concerns, resulting in the circulation of anxiety among the public [104]. It is the responsibility of the healthcare providers to rectify the misconceptions related to vaccination among the population, while acknowledging parents' concerns, updating their knowledge on vaccine related health information by paying close attention to the latest scientific research, and allocating sufficient time to instruct the concerned population on vaccine safety [101].

Mainland China has not introduced HPV vaccination into the routine immune vaccination program, experiences from other countries that implemented HPV vaccination program can be taken as an example. In many counties, an organized vaccination program is recommended to increase the vaccination coverage. It is now widely believed that the most urgent public-health issue is to increase HPV vaccination coverage and improve completion of the vaccination schedule, especially among sexually active females [105]. Thus, many studies further explored means to boost vaccination rates. An analysis showed that HPV vaccination rate could not be increased solely by educational intervention. A research conducted in America showed that a provider-centered PICME (Performance Improvement Continuing Medical Education) intervention, which includes repeated communication, focused education, and individualized feedback, proved an effective measure for sustained improvement of vaccination rates [106]. Another study showed obvious differences between adopters and non-adopters via in-depth interviews, emphasizing that vaccinated women benefit from supportive social influences whereas unvaccinated women’s concerns regarding the safety and efficacy of short- and long-term vaccination was influenced by their interpersonal network [107].

Further research to perfect the existing HPV vaccines is needed. Moreover, as a measure of primary prevention, HPV vaccination should be performed alongside cervical screening (secondary prevention) as a clear strategy for the prevention of cervical cancer.

The strength of our analysis is that the evaluation of the recently published papers about HPV vaccination among the Chinese population allowed us to offer evidence-based advice for the implementation of HPV vaccination in Mainland China in future. However, there were some limitations in this study. Obvious heterogeneity existed in the meta-analysis. We tried to perform meta-regression analysis to explain the source of heterogeneity, however, significant heterogeneity remained unexplained after an exploration of the relative factors, such as sampling method and population characteristics. In fact, for observational studies that involve proportions, substantial heterogeneity is a common dilemma [108]. Although a theoretical framework was designed, it is difficult to ensure that all the original studies used rigorous testing and validation for the investigation as previously outlined in real circumstances. These variations and constraints may account, at least partly, towards the observed heterogeneity. In addition, measures of studied factors were inconsistent among studies, and it is difficult to clarify the inconsistencies due to the difference of measurements across included studies or true variability among the population [109].

Conclusions

In conclusion, this meta-analysis proved low HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge among the Chinese population. HPV vaccine awareness differed across sexes, ethnicities, and regions. However, given the limited quality and number of included studies, future studies with improved design are necessary for the verification of our findings.

Acknowledgements

We thank the contributions to this study made in various ways by members of the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics and Shenzhen Maternity and Child Health Hospital.

Abbreviations

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| EDA | Eastern developed areas |

| CLDA | Central less developed areas |

| WUDA | Western or undeveloped areas |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| I2 | I-square |

| VLP | Virus-like particles |

| PICME | Performance Improvement Continuing Medical Education |

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YZ conducted the meta-analysis and drafted the manuscript. YW conceived the study and edited the manuscript. LL made substantial contributions to revising the manuscript. YF performed the detailed quality framework. ZL carried out the literature search and coding of original studies. YYW was involved in reviewing the articles and statistical analyses. SN conceived and designed the experiments, and supervised the study in all phases. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yanru Zhang, Email: moc.qq@720407795.

Ying Wang, Email: moc.qq@029840174.

Li Liu, Email: moc.qq@55625962.

Yunzhou Fan, Email: moc.361@49288234531.

Zhihua Liu, Email: moc.qq@407183287.

Yueyun Wang, Email: moc.621@9403019002ry.

Shaofa Nie, Email: nc.ude.umjt.sliam@ein_fs.

References

·

· mutailipu, Sayipujiamali

mutailipu, Sayipujiamali ·

· mijiti. Lin GG. Investigation and analysis on cognition of cervical cancer,HPV and HPV vaccine among Uygur and Han women in Xinjiang. Mater Child Health Care China. 2015;30(3):434–7. [Google Scholar]

mijiti. Lin GG. Investigation and analysis on cognition of cervical cancer,HPV and HPV vaccine among Uygur and Han women in Xinjiang. Mater Child Health Care China. 2015;30(3):434–7. [Google Scholar]Articles from BMC Public Health are provided here courtesy of BMC

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2873-8

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12889-016-2873-8

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Article citations

Analysis of high-risk human papillomavirus infections and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: factors influencing awareness among women of childbearing age in southwest China.

Prim Health Care Res Dev, 25:e41, 07 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39370943 | PMCID: PMC11464798

Exploring the Impact of Knowledge about the Human Papillomavirus and Its Vaccine on Perceived Benefits and Barriers to Human Papillomavirus Vaccination among Adults in the Western Region of Saudi Arabia.

Healthcare (Basel), 12(14):1451, 20 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39057593 | PMCID: PMC11276567

Awareness of HPV vaccine and its socio-demographic determinants among the parents of eligible daughters in Bangladesh: A nationwide study.

Heliyon, 10(10):e30897, 08 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38778954 | PMCID: PMC11109798

Evidence of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Regarding Human Papilloma Virus Vaccination at the Community Level in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.

Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 25(3):793-800, 01 Mar 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38546062 | PMCID: PMC11152397

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Human papillomavirus vaccination uptake and determinant factors among adolescent schoolgirls in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Hum Vaccin Immunother, 20(1):2326295, 20 Mar 2024

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 38505959 | PMCID: PMC10956624

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (59) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Willingness to Accept Human Papillomavirus Vaccination and its Influencing Factors Using Information-Motivation-Behavior Skills Model: A Cross-Sectional Study of Female College Freshmen in Mainland China.

Cancer Control, 28:10732748211032899, 01 Jan 2021

Cited by: 10 articles | PMID: 34634207 | PMCID: PMC8516380

Global parental acceptance, attitudes, and knowledge regarding human papillomavirus vaccinations for their children: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis.

BMC Womens Health, 24(1):537, 27 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39334328 | PMCID: PMC11428909

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccine among parents of junior middle school students in Jinan, China.

Vaccine, 33(22):2570-2576, 14 Apr 2015

Cited by: 21 articles | PMID: 25887088

Knowledge of human papillomavirus and the human papillomavirus vaccine in European adolescents: a systematic review.

Sex Transm Infect, 92(6):474-479, 20 Jan 2016

Cited by: 43 articles | PMID: 26792088

Review

and

and