Abstract

Free full text

Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research Consortium: Accelerating Evidence-Based Practice of Genomic Medicine

Abstract

Despite rapid technical progress and demonstrable effectiveness for some types of diagnosis and therapy, much remains to be learned about clinical genome and exome sequencing (CGES) and its role within the practice of medicine. The Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research (CSER) consortium includes 18 extramural research projects, one National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) intramural project, and a coordinating center funded by the NHGRI and National Cancer Institute. The consortium is exploring analytic and clinical validity and utility, as well as the ethical, legal, and social implications of sequencing via multidisciplinary approaches; it has thus far recruited 5,577 participants across a spectrum of symptomatic and healthy children and adults by utilizing both germline and cancer sequencing. The CSER consortium is analyzing data and creating publically available procedures and tools related to participant preferences and consent, variant classification, disclosure and management of primary and secondary findings, health outcomes, and integration with electronic health records. Future research directions will refine measures of clinical utility of CGES in both germline and somatic testing, evaluate the use of CGES for screening in healthy individuals, explore the penetrance of pathogenic variants through extensive phenotyping, reduce discordances in public databases of genes and variants, examine social and ethnic disparities in the provision of genomics services, explore regulatory issues, and estimate the value and downstream costs of sequencing. The CSER consortium has established a shared community of research sites by using diverse approaches to pursue the evidence-based development of best practices in genomic medicine.

Introduction

With the rapid advances in sequencing technology and variant interpretation, the era of genomic medicine by clinical genome and exome sequencing (CGES) is underway,1, 2, 3 but there are substantial knowledge gaps in its application. In 2010 and 2012, the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) issued a request for applications (RFA) for a Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research (CSER) program focused on identifying and generating evidence to address key challenges in applying sequencing to the clinical care of individuals.4, 5 These challenges span a range of issues surrounding the generation, analysis, and interpretation of CGES data, as well as the translation of these data for the referring physician, communication to the participant and families, and examination of the clinical utility and broader ethical, legal, and social implications (ELSIs) of utilizing genomic data in the clinic.

Grant applications in response to this RFA employed a three-project structure. Project 1 addressed “one or more areas of medical investigation (i.e., disease or therapeutic approach) or a specific approach to the use of genotype-phenotype data within a clinical context (e.g., risk prediction modeling or cancer mutation profiling).” Project 2 addressed “the development of methods to analyze genomic sequence data for clinically actionable variants, as well as parsing these data into manageable components to translate the findings into formats that eased interpretation of the findings by the clinician.” Project 3 “investigated how patients understand, react to, and use individual genomic results when they are offered and returned … [and] investigate[d] the experiences of clinicians regarding the return of results.” Nine sites were funded by the NIH cooperative agreement or U-award mechanism. In addition, the NHGRI intramural ClinSeq study joined the CSER consortium as a tenth site in 2013. These sites, including ClinSeq, are collectively described as the U-award sites for convenience throughout the rest of this paper.

In 2013, the CSER consortium was expanded to incorporate a pre-existing consortium (formerly known as the ELSI Return of Results Consortium) that included nine previously awarded projects relating to the return of research results and management of secondary findings (also called incidental findings) in both research and clinical settings. These projects (some initiated by investigators and some funded under RFAs)6, 7 used the NIH regular research grant or R-award mechanism and are collectively termed R-award sites in this paper. The consolidation of these projects under the CSER consortium umbrella has fostered intensive interactions among a diverse collection of clinicians, genomic researchers, social scientists, biomedical informaticians, bioethicists, and legal scholars. A CSER coordinating center8 was funded in 2013 to facilitate collaborative efforts among the CSER investigators and to broadly disseminate information from the CSER consortium to the biomedical research community. Consortium investigators have collaborated to explore distinct but complementary approaches to utilizing CGES data in the practice of medicine. This report provides a high-level overview of the consortium, its accomplishments to date, and the community resources that have been generated. This report summarizes major steps that the CSER consortium has taken to improve the future of health care by beginning to develop clinical sequencing best practices and determining the effect of this technology on participants, providers, and the global health-care system. It also reviews steps that can be taken to further improve the clinical implementation of this developing technology and guide future health-care policies.

Overview of the CSER Consortium

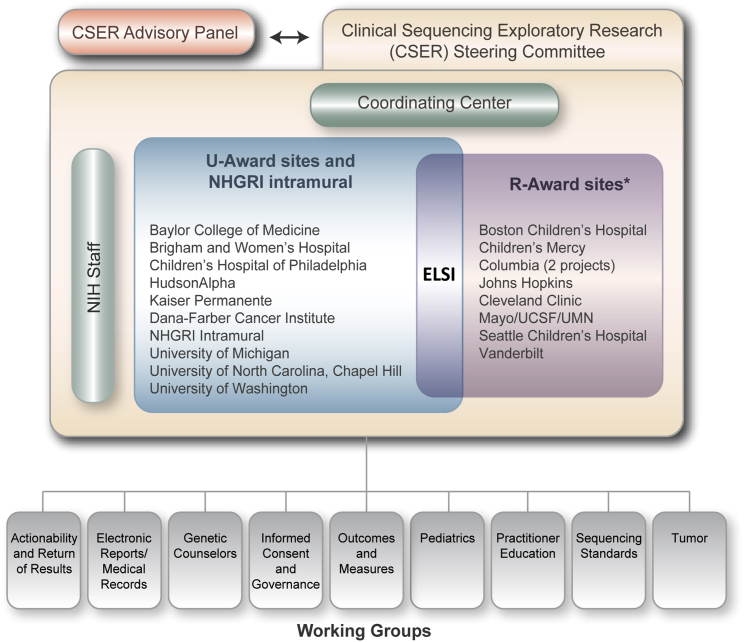

The organization of the consortium and description of the sites are depicted in Figure 1 and Table 1. Four of the projects are focused solely on participants diagnosed with cancer or at an increased risk of cancer, whereas the remainder focus on participants with other medical conditions or self-reported healthy participants seen in primary care. Across the projects, there are adult and/or pediatric participant cohorts, and the centers provide exome and/or genome sequencing (Table 1). The R-awards have considerable synergy with the ELSI components (project 3) of the U-award (Table 2). The ELSI projects utilize quantitative and qualitative empirical approaches, along with normative and legal analyses, in most cases by employing multiple methods. There are also nine cross-project, collaborative working groups (Table 3). Details of the U-award, the R-award, the consortium-wide working groups, and additional published and preliminary data are provided in the Supplemental Data.

Schematic of the Structure of the CSER Consortium

Grants funded under RFA-HG-11-003 and RFA- HG-11-004 have ended, but the investigators on those grants continue to participate in consortium activities. Along with ELSI investigators on the U-awards, they meet regularly to discuss ELSI issues relevant to CSER. Note: this figure was updated for the purposes of this publication and is reproduced with permission from the CSER consortium; it is now available on the CSER website (see Web Resources).

Table 1

CSER Consortium U-Awards

| Project Name | Institutionsa | Project Goal | Population | Tissue Type | Technique | Disease Status | Discloser of Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASIC3: Baylor Advancing Sequencing into Childhood Cancer Care | Baylor College of Medicine | incorporating CLIA-certified tumor and blood exome sequencing | pediatric | germline and solid tumors | exome sequencing | known disease | oncologist with a genetic counselor present for consult if needed |

| CanSeq: The Use of Whole-Exome Sequencing to Guide the Care of Cancer Patients | Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard | improving cancer outcomes by identifying biologically consequential tumor alterations with existing or emerging technologies | adult | germline and solid tumors | exome sequencing | known disease | oncologist with a referral to genetic counseling if needed |

| ClinSeq: A Large-Scale Sequencing Clinical Research Pilot Study | National Human Genome Research Institute | comparing identified genetic variants with individual and family-history information | adult | germline | exome sequencing | seemingly healthy | genetic counselor and/or medical geneticist |

| HudsonAlpha: Genomic Diagnosis for Children with Developmental Delay | HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, University of Louisville University of Louisville | identifying genetic variations causing developmental delay, intellectual disability, and related phenotypes, as well as medically relevant secondary findings | adult and pediatric | germline | exome and genome sequencing | known disease | medical geneticist and genetic counselor |

| MedSeq: Integration of Whole Genome Sequencing into Clinical Medicine | Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Duke University Baylor College of Medicine, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Duke University | integrating whole-genome sequencing into clinical medicine in healthy adults and adults with cardiomyopathy | adult | germline | genome sequencing | seemingly healthy and known disease | primary-care physician or cardiologist |

| MI-ONCOSEQ: Michigan Oncology Sequencing Center | University of Michigan, Johns Hopkins University Johns Hopkins University | implementing clinical sequencing for sarcomas and other rare cancers | adult and pediatric | germline and solid tumors | genome sequencing | known disease | oncologist with a referral to genetic counseling |

| NCGENES: North Carolina Clinical Genomic Evaluation by Next- Generation Exome Sequencing | University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill | investigating the use of whole-exome sequencing in individuals with hereditary cancer susceptibility, genetic heart disorders, neurogenetic disorders, and congenital malformations | adult and pediatric | germline | exome sequencing | known disease | medical geneticist and genetic counselor |

| NEXT Medicine: Clinical Sequencing in Cancer: Clinical, Ethical, and Technological Studies | University of Washington | studying the clinical implementation of whole-exome sequencing in participants with colorectal cancer or polyposis | adult | germline and tumor | exome sequencing | known disease | genetic counselor and/or medical geneticist |

| NextGen: Understanding the Impact of Genome Sequencing For Reproductive Decisions | Kaiser Permanente, Oregon Health & Sciences University, Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington Oregon Health & Sciences University, Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington | integrating whole-genome sequencing for preconception carrier status and secondary findings into clinical care | adult | germline | genome sequencing | seemingly healthy | genetic counselor |

| PediSeq: Applying Genomic Sequencing in Pediatrics | Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania University of Pennsylvania | examining the use of whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing in five heterogeneous disease cohorts: bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, intellectual disability, nuclear-encoded mitochondrial respiratory-chain disorders, platelet-function disorders, and sudden cardiac arrest and/or death | adult and pediatric | germline | exome and genome sequencing | known disease | genetic counselor and/or medical geneticist, cardiologist, hematologist, neurologist |

Table 2

CSER Consortium R-Awards

| Project Name | Institutionsa | Project Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Challenges of Informed Consent in Return of Data From Genomic Research | Columbia University | developing a menu of approaches to deal with the challenges of informed consent for genomic research |

| Disclosing Genomic Incidental Findings in a Cancer BioBank: An ELSI Experiment | Mayo Clinic, University of Minnesota, University of California, San Francisco University of Minnesota, University of California, San Francisco | determining how to manage return of results and secondary findings to family members, including after the death of the research participant |

| Impact of Return of Incidental Genetic Test Results to Research Participants in the Genomic Era | Columbia University | investigating preferences of participants enrolled in genomic research about the disclosure of incidental genetic test results and the psychosocial and behavioral impact of these disclosures |

| Innovative Approaches to Returning Results in Exome and Genome Sequencing Studies | Seattle Children’s Hospital | comparing traditional results-disclosure sessions (with a genetic counselor and over the phone) with an innovative web-based tool |

| Presenting Diagnostic Results from Large-Scale Clinical Mutation Testing | Cleveland Clinic, Mayo Clinic Mayo Clinic | examining participant and professional understandings of diagnostic results from large-scale clinical mutation testing and attitudes toward testing |

| Return of Research Results From Samples Obtained for Newborn Screening | Johns Hopkins University | evaluating current existing state policies regarding the storage of dried blood spots after newborn screening and associated research use to develop policy recommendations |

| Returning Research Results in Children: Parental Preferences and Expert Oversight | Boston Children’s Hospital | exploring research-participant preferences in the return of individual genomic research results and how this might be incorporated into registry and/or biobank research structure |

| Returning Research Results of Pediatric Genomic Research to Participants | Vanderbilt University, McGill University, Baylor College of Medicine, University of Chicago McGill University, Baylor College of Medicine, University of Chicago | exploring legal issues raised by the return of genomic research results in minors |

| The Presumptive Case Again Returning Individuals Results in BioBanking Research | Children’s Mercy Hospital | analyzing claims that the return of bio-repository results is morally obligatory or permissible in genomic research |

Table 3

Cross-Consortium Collaborative Working Groups

| Group Name | Project Goal | Significant Findings | Working-Group References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actionability and Return of Results (Act-ROR) | defining the principles and processes guiding the definition of “actionable gene” across the consortium, including outcomes and discrepancies; developing variant-classification consensus; developing best practices for analysis and communication of genomic results | defining an “actionable” gene by developing consensus regarding variant classification and developing decision support resources around actionability; developing guidance for classification of secondary findings | Amendola et al.,9 Berg et al.,10 Jarvik et al.11 |

| Electronic Health Records | understanding and facilitating collaboration related to the integration of genomic information into the EHR, decision support, and linkage to variant and knowledge databases | understanding and facilitating cross-site collaboration, EHR integration, decision support, and database linkage; analyzing the current state of the EHR among six CSER sites, as well as presenting genetic data within the EHR among eight sites; ascertaining current display of genetic information in EHRs; defining priorities for improvement | Shirts et al.,12 Tarczy-Hornoch et al.13 |

| Genetic Counseling | investigating current genetic-counseling topics related to whole-exome and -genome sequencing, including but not limited to recruitment and enrollment, obtaining informed consent, returning sequencing results, and interacting with participants and families in both research and clinical settings | analyzing CGES topics related to genetic counseling, including informed-consent best practices and lessons learned from returning results | Tomlinson et al.,14 Bernhardt et al.,15 Amendola et al.16 |

| Informed Consent and Governance | discussing emerging issues and developing new and creative approaches related to informed consent in the sequencing context; developing standardized consent language; analyzing experience with institutional governance of genomic data | analyzing CSER approaches to informed consent for the return of genomic research data; supporting the development of new and creative approaches to consent, including best practices and standardized language and protocols; compiling CSER experiences with institutional governance of genomic data | Henderson et al.,17 Appelbaum et al.,18 Koenig19 |

| Outcomes and Measures | identifying priority areas for investigating psychosocial, behavioral, and economic outcomes related to genome sequencing; coordinating measurement of key outcomes across CSER sites; identifying research strategies to generate evidence to inform health-care policies | examining participant outcomes to inform conversations regarding the efficacy and harms of sequencing, as well as the costs and impacts of genomic sequencing on the health-care system | Gray et al.20 |

| Practitioner Education | exploring the growing need for medical genetics education materials for health-care practitioners | newly formed workgroup aimed at exploring the unique educational needs of health-care providers; currently compiling and assessing available resources and looking for gaps and avenues for using expertise and shared experiences within CSER to aid in practitioner genomic education and application | – |

| Pediatrics | exploring and attempting to develop standardized approaches to address the unique ethical, legal, and practical challenges related to returning results in studies involving pediatric populations | deeply analyzing the issues related to childhood genomic sequencing, including comparing current guidelines and examining ethical responsibilities and recommendations for a future framework for genomic sequencing in children | Clayton et al.,21 Brothers et al.22 McCullough et al.23 |

| Sequencing Standards | developing and sharing technical standards for sequencing in the clinical context; developing best practices for genomic sequencing and variant validation | analyzing clinically relevant genomic regions that are poorly covered in CGES across ten CSER sites to learn more about target areas for future improvement; developing tools and processes to allow standardized analyses of poorly covered regions at other clinical sequencing centers | – |

| Tumor | exploring the unique technical, interpretive, and ethical challenges involved in sequencing somatic cancer genomes | educating the oncology community regarding the spectrum of potential tumor sequencing results, as well as secondary findings from germline sequencing and revelations of true germline findings from tumor sequencing | Parsons et al.,24 Raymond et al.25 |

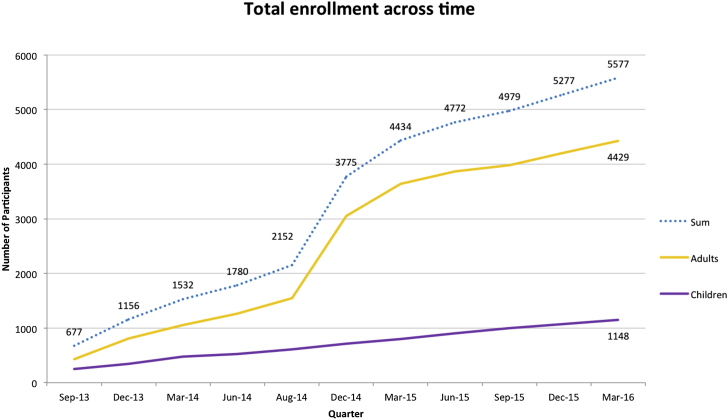

As shown in Figure 2, the U-award sites collectively have thus far recruited 5,577 participants to date (4,429 adults and 1,148 children) and anticipate the eventual recruitment of approximately 7,101 participants, 6,210 of whom are subjects undergoing CGES, when enrollment at each of the sites is completed. Table 4 shows a further breakdown of the indications for sequencing and the diagnostic yields obtained.

Cumulative Enrollment and Sequencing of Participants in the CSER U-Awards

These numbers reflect participant enrollment (including physician enrollment at some sites). Several sites (MedSeq, CanSeq, and NextMed) enrolled control participants (who were not sequenced) in a randomized trial.

Table 4

Yield of Variants Related to Phenotypes in Sequenced Symptomatic U-Award Participants

| Clinical Characteristics | Sample Sizea | Percentage of Participants with at Least One Finding (Median No. of Variants Reported) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P or LP | VUS | Single Recessiveb | Other | ||

| Germline cancer (all) | 1,142 | 6.2%(1) | 36% (1) | 2.4% (1) | 0.4% (1) |

| Syndromic ID or autism | 431 | 19% (1) | 13% (1) | 0.7% (1) | 1.2% (2) |

| Other DD and ID | 50 | 28% (1) | 28% (2) | 14% (1) | 0% |

| Cardiomyopathy | 104 | 27% (1) | 28% (1) | 0% | 1.0% (1) |

| Other cardiovascular | 274 | 5% (1) | 11% (2) | 0% | 0.4% (1) |

| Ophthalmology | 80 | 39% (1) | 16% (1) | 7.5% (1) | 0% |

| All other characteristics | 137 | 18% (1) | 28% (1) | 19% (1.5) | 2.2% (1) |

Abbreviations are as follows: DD, developmental delay; ID, intellectual disability; P, pathogenic; LP, likely pathogenic; and VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

Whereas each U-award project conforms to the tripartite requirements of the original RFA, the clinical studies include observational or interventional designs (including randomized trials). Some projects sequence only probands, whereas others sequence parent-child trios. In addition to performing exome and genome sequencing, one cancer project performs tumor RNA sequencing. Whereas some projects return results only from a list of known disease-associated genes, others return variants from any gene that has a potentially valid association. This variation in approach has resulted in differences among the studies in the diagnostic yield, defined as the percentage of participants with at least one plausible diagnostic genetic finding (Table 4). This variation also empowers creative analysis at the individual sites, enriches data available to the working groups, and provides opportunities to move toward increasingly evidence-based best practices for CGES. The goal of the various CSER working groups (Table 3) is to collaborate on common issues that arise in different ways across the sites to make collective recommendations. Many of the recommendations produced by these working groups will ultimately influence issues that will affect the clinical diagnostic yield of GCES. Although many of the individual studies have not yet completed their analyses, initial results from individual studies and cross-cutting collaborations are emerging, as highlighted below.

Sequencing Specifications and Variant Classification

Each U-award has developed and managed its own translational sequencing pipeline, including variant interpretation, that addresses the technical, analytic, and interpretive components of the clinical sequencing process.2, 26 The time between sample collection and the return of the interpreted report at the start of the CSER consortium projects was 16 weeks and is currently averaging about 13 weeks. Thus far, coverage of the sequenced target (exome or genome) has averaged 20× or greater over 89%–98% of the exome or genome. Average depth of coverage has ranged from 62× to 233× for germline exome sequencing, from 32× to 42× for germline genome sequencing, and from 166× to 250× for tumor exome sequencing. The Sequencing Standards working group is exploring the genome and exome coverage across the different platforms as defined by each site’s pipeline to move toward a more comprehensive approach to clinical sequencing. All results being returned to participants are generated or confirmed in laboratories certified by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA).

The CSER consortium has worked to improve participant care by exploring variant assessment26, 27 and by comparing approaches across the sites. Early efforts in CSER sites9 helped to inform the working group of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) in developing current annotation guidelines.28 To evaluate whether the published ACMG-AMP guidelines improve the consistency of variant classification across sites, a second exercise has focused on intra- and inter-laboratory differences by applying laboratory-specific and ACMG-AMP variant-classification criteria for 99 germline variants. Variant classification based on the ACMG-AMP guidelines was concordant with each site’s prior laboratory-specific variant classifications 79% of the time (intra-laboratory comparison); however, only 34% of the variant classifications were concordant in inter-laboratory classifications (see Amendola et al.29 in this issue of the American Journal of Human Genetics). For the inter-laboratory comparison, it made no difference whether the laboratories used their own prior criteria or the ACMG-AMP guidelines, suggesting subjectivity in the application of the ACMG-AMP guidelines; however, the guidelines were useful in providing a common framework for facilitating resolution of differences between sites. After consensus efforts, 70% concordance was achieved, and only 5% of variants had differences that might affect clinical care. These findings will contribute to future iterations in current ACMG-AMP guidelines and improve and standardize the classification of variant pathogenicity.

Comparison of sequenced variants classified as pathogenic and likely pathogenic by the different U-award sites is instructive, especially in light of the different sets of genes and variant-classification levels that each site selected in reporting their secondary findings. For example, some sites used only small and focused sets of genes that met actionability criteria in advance of sequencing, whereas other sites started with broader lists of thousands of genes and then reviewed the gene-level information alongside the variant-level information when a potentially pathogenic variant or novel loss-of-function variant was identified in the gene. As a result, among participants sequenced across the CSER consortium, comparisons of the rate of secondary findings at each site are difficult.10 Similarly, the decision to return any pharmacogenomic information or recessive carrier status also varied across sites by design (e.g., one site focused exclusively on the latter). As of the latest reported individual-level data, 3,296 participants have been sequenced and have received their sequencing results. Among sites disclosing any pharmacogenomic information (n = 4), 32.3%–100% of sequenced participants received information about one or more variant(s) related to pharmacogenomic response. 2%–92% of participants have received information about recessive carrier variants, and this wide range is due to differences in the number of genes considered for return at each site. When just the genes recommended by the ACMG for secondary result return were examined,30 68 of the 3,296 (2.1%) CSER research participants were reported to have a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in at least one of these genes unrelated to the primary test indication; site-specific percentages varied from 0.28% to 6.52%. This variation can be attributed to a variety of factors, including differences in variant-classification methods,29 small sample sizes at many of the sites, and the fact that some sites report only pathogenic findings, whereas others report pathogenic and likely pathogenic findings and even variants of uncertain significance. Also, some sites report only on a subset of the 56 ACMG genes, such as genes associated with cancer predisposition.

The variant-interpretation project described above is now helping to bring more consistency to the variant-classification process across sites. In addition, the CSER consortium is working with sites to submit all of their classified variants to ClinVar to improve variant-classification comparisons with other submitters and identify differences that can be resolved. As of the latest reporting, over 2,795 classified variants have been submitted to ClinVar by the CSER sites, making CSER one of the top 20 submitters to ClinVar. Additionally, individual-level datasets containing genotypes and phenotypes from over 2,401 individual-level datasets have been submitted to dbGaP.

Implementation of Clinical Sequencing in the CSER Consortium

Among the four CSER sites conducting sequencing in cancer participants, the BASIC3 trial has presented preliminary data showing that nearly 40% of pediatric participants with solid tumors have potentially actionable mutations when the results of tumor and germline exome sequencing are combined.31 CanSeq has focused on enrolling participants with advanced colorectal and lung cancer, of whom 88.4% were found to have actionable or potentially actionable somatic genome alterations, whereas the Michigan Oncology Sequencing Center (MI-ONCOSEQ) has identified clinically relevant results from tumor sequencing in 60% of adult and pediatric cancer participants.32 Both the CanSeq and MI-ONCOSEQ projects have implemented production-scale exome sequencing from archival tissue samples, and the latter program is pioneering an exome-capture transcriptome protocol that improves performance on degraded RNA.33 The NEXT Medicine study has incorporated exome germline sequencing through a randomized trial to examine care outcomes in participants with hereditary colorectal cancer and/or polyps.34

CGES has also been utilized in the diagnosis of numerous suspected genetic conditions. For six disease cohorts that have undergone exome sequencing in PediSeq, the diagnostic rates have varied from 6% in platelet disorders to 20% in sudden cardiac death to 50% in intellectual disability.35 PediSeq has also created phenotype and pedigree capture technologies, including the use of phenotypes to prioritize gene interpretation36 and the pedigree-drawing program Proband, an app with over 1,700 downloads to date. NCGENES and the HudsonAlpha sites both enroll children with intellectual disabilities and have both observed similar variations in diagnostic rates. NCGENES includes participants with a broad range of diseases; diagnostic rates range from 21% in familial cancer to 39% in children with dysmorphic features to 58% among individuals with retinopathy.37 The MedSeq project, one of three randomized trials within the CSER consortium, is exploring the potential advantages of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) in participants with cardiomyopathy and has found that WGS robustly confirms diagnoses previously made by next-generation cardiomyopathy panels and occasionally identifies previously undetected etiologic candidates in participants who were not diagnosed by panel testing.38

In an attempt to quantify the importance of secondary findings, the NCGENES site created a semiquantitative “binning” metric39, 40 (versions of which have been broadly adapted by other efforts).41, 42 NCGENES reports the frequency of discovering a medically actionable secondary finding to be 3.4%. NEXT Medicine, in conjunction with the Actionability and Return of Results working group,10 defined a large list of genes for medically actionable conditions and estimated that 0.8% of individuals of European ancestry and 0.5% of individuals of African-American ancestry would be expected to have a pathogenic variant returned as an incidental finding from exome sequencing.9 PediSeq reviews variants in a list of nearly 3,000 genes and returns secondary findings for risk of Mendelian disease in 10%–15% of participants and carrier findings in nearly 90% of participants. The MedSeq project worked collaboratively with Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen)26, 41 to apply a method for gene-disease validity classification to evaluate which of the approximately 4,500 disease-associated genes analyzed to date have sufficiently strong evidence for returning variants. The BASIC3 study utilizes the ACMG list of 56 genes plus additional actionable genes evaluated by the project 2 team and has an overall secondary-findings rate of 4.8%.2

Although secondary findings in the context of diagnostic sequencing represent a kind of “opportunistic screening,”3, 43, 44 several sites have explored the use of sequencing in persons without a suspected genetic condition, a model closer to actual population screening. ClinSeq, the NHGRI intramural program, has treated non-diagnostic sequencing as a hypothesis-generating methodology to report on the implications of secondary findings associated with heart disease,45 malignant hyperthermia,46 diabetes,47 a form of arrhythmia,48 and the discovery of a late-onset neurometabolic disorder.49 After identifying loss-of-function variants in genes for which haploinsufficiency is associated with disease, ClinSeq investigators followed up with in-depth phenotyping to reveal that roughly half of the population carrying such variants had subtle phenotypes of underlying genetic disease but were unaware of this.50 Similarly, the MedSeq project has returned pathogenic variants, likely pathogenic variants, and even suspicious variants of uncertain significance in healthy middle-aged adult volunteers to their primary-care physicians and cardiologists by using a single-page summary of whole-genome results.26, 51 This report categorizes risk variants for monogenic diseases (in genes associated with dominant disease or in genes associated with autosomal recessive disease and in which biallelic pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants have been identified), recessive carrier variants, pharmacogenomic variants, SNP-based risk scores for common cardiovascular conditions, and variants that characterize red blood cell and platelet antigens.26, 38, 51, 52, 53 BASIC3 and CanSeq are enrolling large teams of pediatric and adult oncologists who receive exome sequencing results and disclose them to families of pediatric cancer participants and adult cancer participants. The primary-care physicians in MedSeq and the oncologists in CanSeq do not have formal genetics training, but in the case of MedSeq, they have been given a brief training module to assist them in interpreting and acting on the genome reports.38, 51 In MedSeq, both providers and sequenced participants (along with control individuals who are not sequenced) are studied through surveys, interviews, and close monitoring of electronic health records (EHRs), yielding insights about physician preparedness for CGES.54, 55, 56, 57

Several U-award sites are returning carrier status in addition to monogenic secondary findings. For example, both the MedSeq project and the NCGENES study include carrier results as additional findings in adult participants. The NextGen study is a randomized trial directly investigating the implementation of carrier screening to aid reproductive decision making in adults not known to be a carrier of genetic disease. Focus groups exploring participant and clinician perspectives have shown that potential participants have differing degrees of interest in learning their carrier status,58 and of those enrolled so far, 71% have at least one carrier result, and 89% of participants are choosing to receive results in one of four optional categories (serious, moderate, adult-onset, and unpredictable). The ClinSeq study is also conducting a randomized trial comparing the return of carrier results through standard-of-care counseling and that through a web site to assess the impact of counseling approach on the cost of genomic health care.

Outcomes and ELSI Issues in Clinical Sequencing

The main results from many of the projects have not yet been analyzed or published because enrollment is still ongoing for some of the projects. However, the CSER consortium is already providing insights into medical, behavioral, psychosocial, and economic outcomes related to the growing use of genomic data in the clinic.20, 59, 60 The consortium’s Outcomes and Measures working group has identified common research priorities, developed instruments to facilitate data harmonization, and initiated cross-site aggregate and comparative analyses.20 The inclusion of investigators with expertise in normative and legal ELSI analyses provides additional assurance that best practices based upon CSER data will not only be based on evidence but also be ethically and legally sound.

A major focus to date has been the disclosure of secondary genomic findings to participants. Early findings, based on qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods research, suggest that participants and research participants queried during the informed-consent process are usually receptive to learning such findings but that preferences are influenced by the precise nature of the findings, how the offer is made, and a number of individual participant attributes.59, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 For example, in the NCGENES study, adult participants are randomized to either a “control” group or a “decision” group, participants in the latter of which are asked to decide whether they wish to receive any of the six categories of non-actionable secondary findings. Whereas the majority in the “decision” group initially stated an intention to request all secondary findings, fewer than one-third actually requested one or more, demonstrating a difference between hypothetical and real-world actions.

The CSER consortium’s empirical studies of clinicians’ and genomic researchers’ attitudes about disclosing secondary genomic findings show that although few have significant experience in returning such findings, most report that they are motivated to do so in at least some circumstances.55, 68, 69, 70 At the same time, CSER studies highlight the many complexities, both normative and practical, that invariably enter into decisions about whether, when, and how such findings should be made available.43, 69, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77

The CSER consortium has also addressed the challenges involved in obtaining informed consent for clinical sequencing, including tailoring approaches that are best suited to specific clinical contexts. The consortium has published an empirical analysis of the consent forms used at six U-award sites and three R-award sites, along with recommendations for ways in which consent forms can be improved.17 CSER investigators have defined four models of consent for the disclosure of secondary findings,18 identified seven discrete challenges representing gaps in genome sequencing knowledge and faced by genetic counselors,78 and provided illustrative case examples of practical issues involved in consent and disclosure decisions,79, 80 all suggesting an expanded future role for genetic counselors.14, 15, 16, 81, 82

Through its Pediatrics working group, CSER has focused considerable attention on genomic sequencing in children.21, 22, 23 Several site-specific publications have addressed the appropriate role of children in decision making,83, 84, 85 preferences of genetic professionals regarding the disclosure of findings in pediatrics,68, 70, 86 limitations in parents’ understanding of choices regarding receipt of their children’s findings,87 and certain unique features of informed consent in pediatric oncology.79

CSER investigators have also conducted important legal and regulatory analyses relevant to clinical sequencing, including the legal liability for disclosure or non-disclosure of findings to patients, research participants, and family members.88, 89, 90, 91 Other topics include the legal implications of incorporating genomic data into EHRs,92, 93 the limitations of current laws and the potential impact of recent changes to federal privacy and laboratory regulations on access to one’s genetic data,94, 95 and a comparison of US law and policy and that of other countries on family access to a proband’s genomic findings.96

Finally, early research has assessed the economic value and cost-effectiveness of returning secondary findings,97, 98 and additional efforts are underway. CSER investigators have highlighted the need for future research in behavioral economics by recognizing that provision of information does not necessarily lead to health benefits. This research will provide insights into participants’ and families’ responses to genomic information and downstream impacts on the utilization of health services, both positive and negative, providing strategies for maximizing positive uses of genomic information.99, 100

Additional Dissemination and Outreach Activities

The CSER consortium has established a shared, real-time community of research sites pursuing common goals in related yet distinct settings. Thus, the value of the consortium goes beyond the individual publications mentioned above. When CSER was initially funded in 2011, each site was challenged to implement clinical sequencing, standardize variant interpretation, reduce sequencing turn-around time, and develop reliable bioinformatics pipelines. Addressing these common challenges among sites has yielded insights that, when synthesized, are becoming relevant to the broader scientific community. For example, sites have adopted different approaches to the analysis of clinical sequencing data, best exemplified by the “diagnostic-gene-list” approach employed by some sites and the “variant-first” approach adopted by others. An ability to compare such analytical approaches continues to inform the entire field in its ongoing efforts to optimize interpretation. More generally, there have been vibrant discussions and sharing of approaches to informed consent, educational materials, and disclosure methods across many CSER sites. More recently, working groups have been exploring approaches to improve sequencing standards, coverage of clinically relevant genes, and variant annotation by using existing and newly adopted ACMG variant-classification guidelines. Looking ahead, CSER will continue to address questions that are best answered across multiple sites and in multiple settings. For example, projects related to the return of carrier status, re-interpretation of results, management of secondary findings, ethical approaches to combining research with clinical care, and downstream costs of genomic testing are underway.

CSER-related interactions often expand to related genome sequencing efforts. For example, CSER investigators are interacting or collaborating with other consortia in the areas of EHR-based phenotyping, genotyping, and integration of results into the EHR (Electronic Medical Records and Genomics [eMERGE]);101, 102, 103 community-based curation of genes and variants (ClinGen);41 undiagnosed diseases (Undiagnosed Disease Network [UDN]); implementation of genomic testing in diverse settings (Implementing Genomics in Practice [IGNITE]); newborn sequencing (Newborn Sequencing in Genomic Medicine and Public Health [NSIGHT]); ethics (Centers for Excellence in ELSI Research [CEERs]); prostate cancer (Stand Up 2 Cancer [SU2C] and Prostate Cancer Foundation [PCF] international dream team); trials of prospective precision medicine in cancer (National Cancer Institute and Children’s Oncology Group Pediatric MATCH study);104 and the evolving role of the clinical geneticist (Clinical Genetics Think Tank). These inter-consortium interactions vary in nature from informal consultations to resource sharing to joint meetings and publications.11, 12, 22, 105 CSER is also informing the development of professional guidelines28, 30, 106, 107 by sharing resources (e.g., gene lists) and serving as a “sandbox” in which early implementation can be assessed. Other dissemination activities include the release of open-source software,108 deposition of data into ClinVar and dbGaP, and being a part of high-profile sessions at national medical and bioethics meetings. Study-specific resources such as consent forms, study protocols, educational materials, and sample reports are made publicly available at the CSER Coordinating Center’s website (see Web Resources for links to these groups).

Efforts to facilitate outreach to individuals and communities outside academic medical centers have also been implemented. By initiating collaborations with rural and underserved populations, some sites are establishing broader availability of genome sequencing, extending its clinical reach outside of academia and facilitating robust participation by underserved minority groups. Sites interacting with state government agencies that serve families of special-needs children or comprising integrated delivery systems are using their CSER experience as a platform to educate the public and stakeholders who make coverage decisions.

Future Directions for the CSER Consortium

Through its combination of individual scientific enterprise, practitioner participation, and collective synergy, the CSER consortium is uniquely poised to fill some of the most important evidence gaps in the implementation of genomic medicine. Looking toward a future with widespread evidence-based and equitable availability of genomic medicine, there are critical challenges in terms of implementing technical refinements, including accessibility to individuals of diverse ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds and the attainment and demonstration of desired medical outcomes. In particular, CSER sites can be expected to further advance analyses of observed differences in variant interpretation in concert with ClinGen41 and to identify new approaches for calling structural variation from next-generation sequencing data. Finally, the genomics regulatory arena is very dynamic with evolving FDA oversight109, 110 and proposed changes to the Common Rule. The CSER consortium has and will continue to play an important role in evaluating and communicating the impact of this rapidly evolving area in topics such as consent and disclosure.

The CSER consortium, along with all genomics investigators, must also consider whether and how genomic medicine might exacerbate disparities in health and health-services utilization to ensure that the intended benefits of genomic medicine are justly distributed.111 There are several reasons why poor, rural, and racial and ethnic minority populations might be less likely to realize tangible health-related benefits as genomic medicine becomes more commonplace. Existing databases of disease-associated genes and variants are overwhelmingly drawn from individuals of European ancestry, and populations of non-European ancestry have patterns of genetic variation that are not yet well characterized in control populations. This lack of data complicates the interpretation of novel and rare variants. Also, historical and continuing social disparities in health-care access, health-insurance coverage, and community engagement and trust are heightened by issues raised in genomics. Without concerted intervention, these converging forces threaten to perpetuate and expand current health disparities in ways that might disadvantage members of racially and ethnically diverse communities for decades. A number of sites within the CSER consortium have begun expanding their enrollment of minority ethnicities to begin addressing these inequalities and will continue to identify relevant opportunities.

More formal studies in comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness are necessary for answering questions about whether and under what circumstances sequencing should be applied and for guiding third-party payment for clinically helpful genomic services. The degree to which the identification of secondary findings and the sequencing of asymptomatic individuals might lead to downstream health benefits and incur or offset downstream costs will be critical. Deeper phenotyping of apparently pathogenic variants in participants who do not show symptoms of an associated genetic condition will be required and will provide key information on the classification of variant pathogenicity, penetrance estimation, and the identification of modifying or protective factors that could provide important insights into future treatment of rare or even common conditions. But with iterative and more in-depth phenotyping and the use of tools ranging from wearable monitoring devices to microscopic processes in cell culture, there is an opportunity to define disease and diminished function in entirely new ways. As medicine enters an era where sequencing and other -omics can be applied routinely, the CSER consortium is helping to accelerate the realization of preventive and precision medicine.

Consortia

CSER Consortium investigators include Michelle Amaral, Laura Amendola, Paul S. Appelbaum, Samuel J. Aronson, Shubhangi Arora, Danielle R. Azzariti, Greg S. Barsh, E.M. Bebin, Barbara B. Biesecker, Leslie G. Biesecker, Sawona Biswas, Carrie L. Blout, Kevin M. Bowling, Kyle B. Brothers, Brian L. Brown, Amber A. Burt, Peter H. Byers, Charlisse F. Caga-anan, Muge G. Calikoglu, Sara J. Carlson, Nizar Chahin, Arul M. Chinnaiyan, Kurt D. Christensen, Wendy Chung, Allison L. Cirino, Ellen Clayton, Laura K. Conlin, Greg M. Cooper, David R. Crosslin, James V. Davis, Kelly Davis, Matthew A. Deardorff, Batsal Devkota, Raymond De Vries, Pamela Diamond, Michael O. Dorschner, Noreen P. Dugan, Dmitry Dukhovny, Matthew C. Dulik, Kelly M. East, Edgar A. Rivera-Munoz, Barbara Evans, Barbara, James P. Evans, Jessica Everett, Nicole Exe, Zheng Fan, Lindsay Z. Feuerman, Kelly Filipski, Candice R. Finnila, Kristen Fishler, Stephanie M. Fullerton, Bob Ghrundmeier, Karen Giles, Marian J. Gilmore, Zahra S. Girnary, Katrina Goddard, Steven Gonsalves, Adam S. Gordon, Michele C. Gornick, William M. Grady, David E. Gray, Stacy W. Gray, Robert Green, Robert S. Greenwood, Amanda M. Gutierrez, Paul Han, Ragan Hart, Patrick Heagerty, Gail E. Henderson, Naomi Hensman, Susan M. Hiatt, Patricia Himes, Lucia A. Hindorff, Fuki M. Hisama, Carolyn Y. Ho, Lily B. Hoffman-Andrews, Ingrid A. Holm, Celine Hong, Martha J. Horike-Pyne, Sara Hull, Carolyn M. Hutter, Seema Jamal, Gail P. Jarvik, Brian C. Jensen, Steve Joffe, Jennifer Johnston, Dean Karavite, Tia L. Kauffman, Dave Kaufman, Whitley Kelley, Jerry H. Kim, Christine Kirby, William Klein, Bartha Knoppers, Barbara A. Koenig, Sek Won Kong, Ian Krantz, Joel B. Krier, Neil E. Lamb, Michele P. Lambert, Lan Q. Le, Matthew S. Lebo, Alexander Lee, Kaitlyn B. Lee, Niall Lennon, Michael C. Leo, Kathleen A. Leppig, Katie Lewis, Michelle Lewis, Neal I. Lindeman, Nicole Lockhart, Bob Lonigro, Edward J. Lose, Philip J. Lupo, Laura Lyman Rodriguez, Frances Lynch, Kalotina Machini, Calum MacRae, Teri A. Manolio, Daniel S. Marchuk, Josue N. Martinez, Aaron Masino, Laurence McCullough, Jean McEwen, Amy McGuire, Heather M. McLaughlin, Carmit McMullen, Piotr A. Mieczkowski, Jeff Miller, Victoria A. Miller, Rajen Mody, Sean D. Mooney, Elizabeth G. Moore, Elissa Morris, Michael Murray, Donna Muzny, Richard M. Myers, David Ng, Deborah A. Nickerson, Nelly M. Oliver, Jeffrey Ou, Will Parsons, Donald L. Patrick, Jeffrey Pennington, Denise L. Perry, Gloria Petersen, Sharon Plon, Katie Porter, Bradford C. Powell, Sumit Punj, Carmen Radecki Breitkopf, Robin A. Raesz-Martinez, Wendy H. Raskind, Heidi L. Rehm, Dean A. Reigar, Jacob A. Reiss, Carla A. Rich, Carolyn Sue Richards, Christine Rini, Scott Roberts, Peggy D. Robertson, Dan Robinson, Jill O. Robinson, Marguerite E. Robinson, Myra I. Roche, Edward J. Romasko, Elisabeth A. Rosenthal, Joseph Salama, Maria I. Scarano, Jennifer Schneider, Sarah Scollon, Christine E. Seidman, Bryce A. Seifert, Richard R. Sharp, Brian H. Shirts, Lynette M. Sholl, Javed Siddiqui, Elian Silverman, Shirley Simmons, Janae V. Simons, Debra Skinner, Nancy B. Spinner, Elena Stoffel, Natasha T. Strande, Shamil Sunyaev, Virginia P. Sybert, Jennifer Taber, Holly K. Tabor, Peter Tarczy-Hornoch, Deanne M. Taylor, Christine R. Tilley, Ashley Tomlinson, Susan Trinidad, Ellen Tsai, Peter Ubel, Eliezer M. Van Allen, Jason L. Vassy, PankajVats, David L. Veenstra, Victoria L. Vetter, Raymond D. Vries, Nikhil Wagle, Sarah A. Walser, Rebecca C. Walsh, Karen Weck, Allison Werner-Lin, Jana Whittle, Ben Wilfond, Kirk C. Wilhelmsen, Susan M. Wolf, Julia Wynn, Yaping Yang, Carol Young, Joon-Ho Yu, and Brian J. Zikmund-Fisher.

Conflicts of Interest

R.C.G. has received compensation for advisory services or speaking from Invitae, Prudential, Illumina, AIA, Helix, and Roche. L.G.B. receives royalties from Genentech and Amgen Corporations and is an uncompensated advisor to Illumina. W.K.C. is a consultant for BioRefrence Laboratories. L.A.G. is a consultant for Foundation Medicine, Novartis, and Boehringer Ingelheim, is an equity holder in Foundation Medicine, and is a member of the scientific advisory board at Warp Drive. He receives sponsored research support from Novartis. D.M. and S.E.P. are employees of Baylor College of Medicine (BCM). BCM and Miraca Holdings Inc. have formed a joint venture, Baylor Miraca Genetics Laboratories, with shared ownership and governance of the clinical genetics diagnostic laboratories. S.E.P. is on the scientific advisory board of Baylor Miraca Genetics Laboratories. N.W. is a shareholder of Foundation Medicine.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Julia Fekecs of the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) for her technical assistance with Figure 1. The authors would like to thank all of the Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research (CSER) participants for their involvement in this research. The authors also thank the members of their CSER advisory panel: Katrina Armstrong, MD; Rex L. Chisholm, PhD; Mildred K. Cho, PhD; Chanita H. Halbert, PhD; Elaine Lyon, PhD; Kenneth Offit, MD; Dan Roden, MD; Pamela Sankar, PhD; and Alan Williamson, PhD. The research described in this report was funded by grants U01HG0006546, U01HG006485, U01HG006500, U01HG006492, UM1HG007301, UM1HG007292, UM1HG006508, U01HG006487, U01HG006507, U01HG007307, U01HG006379, U41HG006834, U54HG003273, R21HG006596, P20HG007243, R01HG006600, P50HG007257, R01HG006600, R01HG004500, R01CA154517, R01HG006618, R21HG006594, R01HG006615, R21HG006612, 5R21HG006613, R01HG007063, HG008685, UL1TR000423, UA01AG047109, and K99HG007076. ClinSeq is supported by the NHGRI Intramural Research Program. C.F.C.-A., L.A.H., C.M.H., D.K., T.A.M., and J.M. are members of the NIH CSER staff team, responsible for management of the CSER program.

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include three Supplemental Notes and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.04.011.

Web Resources

Centers for Excellence in ELSI Research (CEERs), http://www.genome.gov/27561666

Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research (CSER) consortium, https://cser-consortium.org

CSER organizational chart, https://cser-consortium.org/system/files/attachments/cser_organizational_chart.pdf

CSER research materials, https://cser-consortium.org/cser-research-materials

Implementing Genomics in Practice (IGNITE) Network, http://www.ignite-genomics.org

Newborn Sequencing in Genomic Medicine and Public Health (NSIGHT), http://www.genome.gov/27558493

Stand Up 2 Cancer (SU2C) and Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF) international dream team, https://www.standup2cancer.org/dream_teams/view/precision_therapy_for_advanced_prostate_cancer

Proband, http://probandapp.com

Undiagnosed Disease Network (UDN), http://www.genome.gov/27550959

Supplemental Data

References

Articles from American Journal of Human Genetics are provided here courtesy of American Society of Human Genetics

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.04.011

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

http://www.cell.com/article/S0002929716301069/pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.04.011

Article citations

The Surviving, Not Thriving, Photoreceptors in Patients with ABCA4 Stargardt Disease.

Diagnostics (Basel), 14(14):1545, 17 Jul 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39061682 | PMCID: PMC11275370

Diagnostic yield after next-generation sequencing in pediatric cardiovascular disease.

HGG Adv, 5(3):100286, 23 Mar 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38521975 | PMCID: PMC11024993

Parents' Perspectives on Secondary Genetic Ancestry Findings in Pediatric Genomic Medicine.

Clin Ther, 45(8):719-728, 11 Aug 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37573223 | PMCID: PMC11182349

Ethical, legal, and social implications (ELSI) and challenges in the design of a randomized controlled trial to test the online return of cancer genetic research results to U.S. Black women.

Contemp Clin Trials, 132:107309, 27 Jul 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37516165 | PMCID: PMC10544717

Return of Results in Genomic Research Using Large-Scale or Whole Genome Sequencing: Toward a New Normal.

Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet, 24:393-414, 13 Mar 2023

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 36913714 | PMCID: PMC10497726

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (94) article citations

Other citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

The Clinical Sequencing Evidence-Generating Research Consortium: Integrating Genomic Sequencing in Diverse and Medically Underserved Populations.

Am J Hum Genet, 103(3):319-327, 01 Sep 2018

Cited by: 101 articles | PMID: 30193136 | PMCID: PMC6128306

Performance of ACMG-AMP Variant-Interpretation Guidelines among Nine Laboratories in the Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research Consortium.

Am J Hum Genet, 98(6):1067-1076, 12 May 2016

Cited by: 253 articles | PMID: 27181684 | PMCID: PMC4908185

Consensus Genotyper for Exome Sequencing (CGES): improving the quality of exome variant genotypes.

Bioinformatics, 31(2):187-193, 29 Sep 2014

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 25270638 | PMCID: PMC4287941

Processes and preliminary outputs for identification of actionable genes as incidental findings in genomic sequence data in the Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research Consortium.

Genet Med, 15(11):860-867, 24 Oct 2013

Cited by: 83 articles | PMID: 24195999 | PMCID: PMC3935342

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NCATS NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: UL1 TR000423

Grant ID: UL1 TR002319

NCI NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: R01 CA154517

NHGRI NIH HHS (29)

Grant ID: U01 HG009599

Grant ID: UM1 HG006508

Grant ID: P20 HG007243

Grant ID: R01 HG007063

Grant ID: UM1 HG007301

Grant ID: R21 HG006612

Grant ID: R01 HG006600

Grant ID: U01 HG006379

Grant ID: U24 HG007307

Grant ID: UM1 HG007292

Grant ID: R21 HG006596

Grant ID: U01 HG006487

Grant ID: U01 HG006492

Grant ID: U01 HG008685

Grant ID: U54 HG003273

Grant ID: K99 HG007076

Grant ID: R21 HG006594

Grant ID: R21 HG006613

Grant ID: U01 HG007307

Grant ID: P50 HG007257

Grant ID: R01 HG004500

Grant ID: R01 HG006615

Grant ID: R01 HG006618

Grant ID: U01 HG006500

Grant ID: U01 HG006507

Grant ID: U01 HG006546

Grant ID: U01 HG007292

Grant ID: U41 HG006834

Grant ID: U01 HG006485

NIA NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: U01 AG047109

NIMH NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: R01 MH107205