Abstract

Objective

To identify and measure recently described chemical mediators, termed specialized pro-resolving mediators that actively regulate the resolution of acute-inflammation, and correlate measurements with clinical outcomes.Design

Herein, deidentified plasma was collected from sepsis patients (n = 22 subjects) within 48 hours of admission to the ICU and on days 3 and 7 thereafter and subjected to lipid mediator profiling.Setting

Brigham and Women's Hospital Medical Intensive Care Unit.Subjects

Patients in the medical ICU with sepsis.Measurements and main results

In all patients, we identified more than 30 bioactive mediators and pathway markers in peripheral blood using established criteria for arachidonic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, and docosahexaenoic acid metabolomes. These included inflammation initiating mediators leukotriene B4 and prostaglandin E2 and pro-resolving mediators resolvin D1, resolvin D2, and protectin D1. In sepsis nonsurvivors, we found significantly higher inflammation-initiating mediators including prostaglandin F2α and leukotriene B4 and pro-resolving mediators, including resolvin E1, resolvin D5, and 17R-protectin D1 than was observed in surviving sepsis subjects. This signature was present at ICU admission and persisted for 7 days. Further analysis revealed increased respiratory failure in nonsurvivors. Higher inflammation-initiating mediators (including prostaglandin F2α) and select proresolving pathways were associated with the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome, whereas other traditional clinical indices were not predictive of acute respiratory distress syndrome development.Conclusions

These results provide peripheral blood lipid mediator profiles in sepsis that correlate with survival and acute respiratory distress syndrome development, thus suggesting plausible novel biomarkers and biologic targets for critical illness.Free full text

Human sepsis eicosanoid and pro-resolving lipid mediator temporal profiles: correlations with survival and clinical outcomes

Associated Data

Abstract

Introduction

Sepsis produces a major socio-economic burden with significant morbidity and mortality. Recently described chemical mediators, termed specialized pro-resolving mediators, actively regulate the resolution of acute-inflammation.

Design

Herein, de-identified plasma was collected from sepsis patients (n=22 subjects) within 48h of admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and on days 3 and 7 thereafter and subjected to lipid mediator (LM) profiling.

Measurements

In all patients, we identified > 30 bioactive mediators and pathway markers in peripheral blood using established criteria for arachidonic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, and docosahexaenoic acid metabolomes. These included inflammation initiating mediators leukotriene (LT)B4 and prostaglandin (PG)E2 and pro-resolving mediators resolvin (Rv) D1, RvD2, and protectin (PD)1.

Main Results

In sepsis non-survivors we found significantly higher inflammation-initiating mediators including PGF2α and LTB4 and pro-resolving mediators including RvE1, RvD5 and 17R-PD1 than was observed in surviving sepsis subjects. This signature was present at ICU admission and persisted for 7 days. Further analysis revealed increased respiratory failure in non-survivors. Higher inflammation-initiating mediators (including PGF2α) and select pro-resolving pathways were associated with the development of ARDS, while other traditional clinical indices were not predictive of ARDS development.

Conclusions

These results provide peripheral blood lipid mediator profiles in sepsis that correlate with survival and ARDS development, thus suggesting plausible novel biomarkers and biologic targets for critical illness.

Introduction

In response to infection the host mounts a self-limited inflammatory response that when successful produces containment and clearance of the pathogen and return to homeostasis (1–3). Severe sepsis occurs when microorganisms overwhelm the host leading to uncontrolled inflammation, producing organ dysfunction, shock, and death (3). Despite improved management of sepsis, there remains high mortality with no targeted treatments, nor universally agreed-upon biomarkers for survival and outcomes (4). Sepsis is a risk factor for the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), resulting in respiratory failure and increased morbidity and mortality. Similarly, there are neither targeted treatments nor clear predictors for sepsis-induced ARDS.

Co-ordination of the immune response relies on host and pathogen derived classical signals(1–3, 5–7). These include cytokines and chemokines(1, 5) and local chemical mediators, such as the potent leukocyte chemoattractant leukotriene B4, and prostaglandins that promote vascular leakage (6). When the inflammatory response is self-contained, these mediators are protective. In uncontrolled inflammation their production may become dysregulated, a phenomenon linked with many conditions including severe sepsis (3, 5–7).

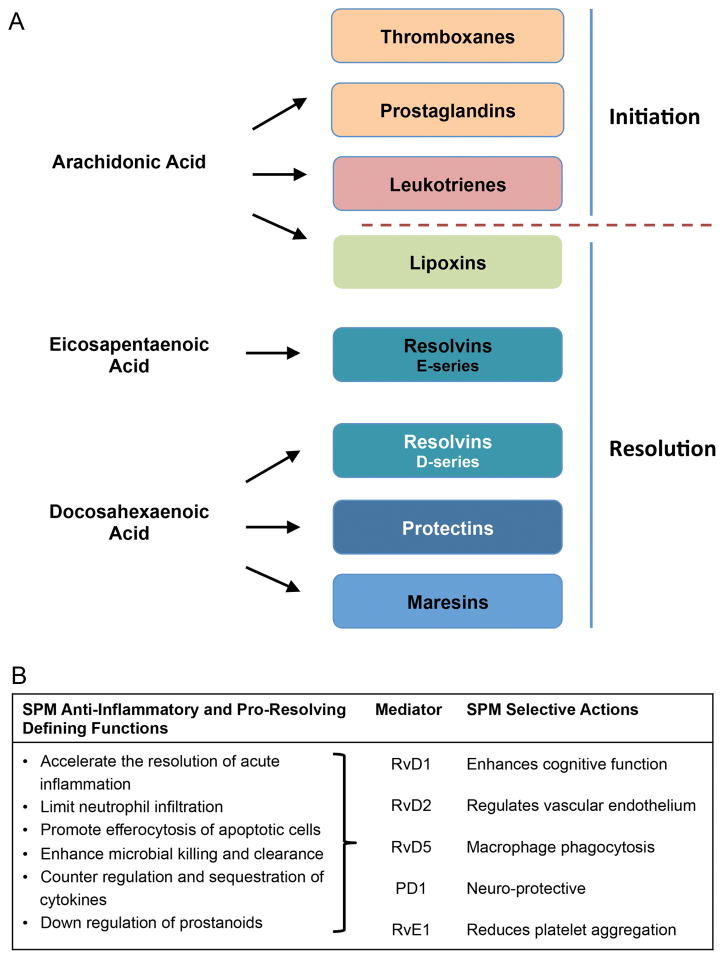

It is now appreciated that endogenous chemical signals are produced that orchestrate the host response to promote resolution of local inflammation (2, 7). These novel leukocyte derived mediators, coined specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPM), are produced via enzymatic conversion of omega-3 essential fatty acids and include structurally distinct chemical families such as the D- and E-series resolvins, protectins and maresins(2) (Figure 1). Biosynthesized in the resolution phase, SPM are agonists of resolution, as they actively counter-regulate pro-inflammatory mediators (i.e. formation and actions of cytokines and lipid mediators), promote phagocyte uptake and killing of bacteria (2, 7–10), enhance viral infection clearance (7, 11), control experimental endotoxemia (12) and bacterial infections (8, 10). Resolvins and lipoxins are also organ protective, reducing leukocyte mediated tissue damage (13) and fibrosis (14). Of note, local and systemic SPM levels become dysregulated during experimental pneumonia in non-human primates (15) and are present in human serum, breast milk, and urine(16, 17).

(A) Prostaglandins, thromboxanes and leukotrienes are initiators of the inflammatory response promoting vascular leak, leukocyte recruitment, thrombosis and smooth muscle contraction(6). The lipoxins, resolvins, protectins and maresins are agonists of resolution. They counter-regulate the formation and actions of inflammation-initiators, promote the clearance of apoptotic cells, uptake and killing of bacteria by phagocytes, tissue repair and regeneration. (B) Summary of the key biological actions of specific pro-resolving mediators.

Recent immunephenotying studies demonstrate that in addition to the classical appreciation that hyperinflammation may lead to a negative outcome in several diseases, immune hypo activation or suppression also leads to patient morbidity and death(18, 19). In order to obtain further insights into mechanisms that lead to a failure of the host response to resolve during the infections leading to sepsis and ultimately death in the present study, we investigated whether SPM were present in the peripheral blood of human sepsis subjects. We then assessed their temporal regulation after intensive care unit (ICU) admission and whether levels of specific SPMs correlated with mortality. We further stratified the clinical data to determine whether SPMs might better predict clinical outcomes than traditional biomarkers and furthermore whether correlation of SPMs with clinical outcomes might point toward new underlying mechanisms for development of critical illness.

Methods

Selection of Subjects for Analysis

This study was approved by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board. Sepsis subjects with plasma samples collected within 48h of ICU admission (termed Day 1) and Days 3 and 7 thereafter were obtained from the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Registry of Critical Illness (20, 21). Those surviving hospitalization (“survivors”) and non-survivors were randomly selected from those with plasma samples of at least 1 mL volume (to allow sufficient material for the assays) available at the three time points. Please see supplementary material for additional details.

Lipid mediator (LM) metabololipidomics; Statistical analysis

Please See Supplementary Material.

Results

Subjects with sepsis were selected from our Registry of Critical Illness (RoCI) medical ICU biorepository (20, 21)with the goal of examining lipid mediators (LM) over 7d in survivors and non-survivors (see Supplement for additional details). Baseline demographic characteristics of subjects stratified by survival are summarized (Table 1A). Non-survivors and survivors exhibited no significant differences, except that non-survivors had a higher acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE)-II clinical score upon admission. To rule out selection bias in selecting subjects for analysis, the 22 selected subjects were compared with a random sample of 30 non-selected patients (See Supplement for additional details) using 29 demographic variables and comorbidities. The occurrence of hematologic disorders was the only variable that differed significantly, with a higher occurrence among selected patients (45% vs. 17%, p=0.03).

Table 1

Age, APACHE II scores, and Glasgow coma scale (GCS) are expressed in medians [min, max, 95% CI]. All other values are expressedby % of total subjects and total number. ^Percentages in this category are calculated from total cancer patients in the cohort. # P<0.05 vs Survivor. Abbreviations: ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; GCS: Glasgow coma scale; CAD: coronary artery disease; CHF: congestive heart failure; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM: diabetes mellitus, CKD: chronic kidney disease, ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML: acute myeloid leukemia

| Table 1A. Patient demographics and clinical parameters – Survivors vs Non-Survivors

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Survivors (n=13) | Non-survivors (n=9) |

| Age (yr) | 60 [27,84] | 60 [36, 80] |

| Gender (male) | 62% (8) | 56% (5) |

| Race | ||

White White | 77% (10) | 89% (8) |

Black Black | 7% (1) | 0% (0) |

Hispanic Hispanic | 15% (2) | 11% (1) |

| Diagnosis | ||

SEPSIS SEPSIS | 77% (10) | 67% (6) |

SEPSIS/ARDS SEPSIS/ARDS | 23% (3) | 33% (3) |

| Positive cultures | 54% (7) | 67% (6) |

| Vasopressors within 24 hours admission | 31% (4) | 67% (6) |

| In-Hospital Mortality | 0% (0) | 100% (9) # |

| Cause of death | ||

| Respiratory Failure | 0% (0) | 78% (7) |

| Other | 0% (0) | 22% (2) |

| APACHE II score | 22 [14,38] | 31 [16,46] # |

| GCS within 24 hours admission | 12 [3,15] | 9 [3,15] |

| Transfusions within 24 hours admission | 15% (2) | 44% (4) |

| Comorbidities | ||

CAD CAD | 38% (5) | 0% (0) |

CHF CHF | 23% (3) | 11% (1) |

COPD COPD | 7% (1) | 22% (2) |

DM DM | 46% (6) | 11% (1) |

Liver disease Liver disease | 0% (0) | 33% (3) |

CKD CKD | 15% (2) | 22% (2) |

Cancer^ Cancer^ | 46% (6) | 89% (8) |

ALL ALL | 15% (2) | 22% (2) |

AML AML | 7% (1) | 33% (3) |

Solid tumor Solid tumor | 15% (2) | 33% (3) |

Bone marrow transplant Bone marrow transplant | 31% (4) | 44% (4) |

| Table 1B. Patient demographics and clinical parameters – Sepsis/ARDS vs Sepsis

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Sepsis/ARDS (n=6) | Sepsis (n=16) |

| Age (yr) | 64.5 [52,84] | 58.6 [27, 80] |

| Gender (male) | 50% (3) | 63% (10) |

| Race | ||

White White | 100% (6) | 75% (12) |

Black Black | 0% (0) | 6% (1) |

Hispanic Hispanic | 0% (0) | 19% (3) |

| Positive cultures | 67% (4) | 56% (9) |

| Vasopressors within 24 hours admission | 67% (4) | 38% (6) |

| In-Hospital Mortality | 50% (3) | 38% (6) |

| Cause of death | ||

| Respiratory failure | 33 % (2) | 31 % (5) |

| Other causes | 17 % (1) | 6 % (1) |

| APACHE II score | 31 [22,46] | 24 [14,43] |

| GCS within 24 hours admission | 7 [3,15] | 11 [3,15] # |

| Transfusions within 24 hours admission | 17% (1) | 0% (0) |

| Comorbidities | ||

CAD CAD | 17% (1) | 25% (4) |

CHF CHF | 0% (0) | 25% (4) |

COPD COPD | 0% (0) | 19% (3) |

DM DM | 33% (2) | 31% (5) |

Liver disease Liver disease | 33% (2) | 6% (1) |

CKD CKD | 17% (1) | 19% (3) |

Cancer^ Cancer^ | 50% (3) | 69% (11) |

ALL ALL | 50% (3) | 6% (1) # |

AML AML | 17% (1) | 19% (3) |

Solid tumor Solid tumor | 17% (1) | 25% (4) |

Bone marrow transplant Bone marrow transplant | 50% (3) | 31% (5) |

Abbreviations: ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; GCS: Glasgow coma scale; CAD: coronary artery disease; CHF: congestive heart failure; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM: diabetes mellitus, CKD: chronic kidney disease, ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML: acute myeloid leukemia

Abbreviations: ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; GCS: Glasgow coma scale; CAD: coronary artery disease; CHF: congestive heart failure; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM: diabetes mellitus, CKD: chronic kidney disease, ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML: acute myeloid leukemia

To assess presence of LM in peripheral blood, we employed a targeted LC-MS-MS approach permitting the identification and quantitation of > 50 specific LM and pathway markers of interest from the three major bioactive essential fatty acid metabolomes in a single sample. At Day 1, we identified mediators from the arachidonic acid metabolome including the classic eicosanoids prostaglandin (PG) E2 and D2, the docosahexaenoic acid metabolome including resolvin (Rv)D1, RvD5 and protectin (PD) D1, and the eicosapentaenoic acid metabolome including RvE1 and RvE2 (Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Each of these mediators was identified in accordance with established criteria (22) (Supplementary Figure 1). These profiles indicate that classic eicosanoid pathways were activated as determined by the presence of TxB2, PG and LTB4 (Supplementary Table 1). While pro-resolving mediators were described initially as local mediators, they were demonstrable in sepsis plasma, raising the feasibility of these mediators as novel biomarkers.

We next examined LM profiles from non-survivors versus survivors using partial least square discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). We found that LM profiles for 21 of 22 patients clustered within ~95% confidence region (white circle; Figure 2A), these gave R2 X = 0.3, R2 Y = 0.6, quality assessment (Q2) statistic of 0.3. LM profiles from 6 of 9 non-survivors gave distinct clusters compared with survivors, and LM in survivors produced a tighter cluster than in non-survivors. Assessment of loading plots from identified LM demonstrated an association between pro-resolving mediators RvE2, LXB4, RvD2 and 15epi-LXB4 in survivors that gave variable importance in projection scores > 1. The major human lipoxygenase(s) each predominantly insert oxygen in the S-configuration; R-stereochemistry can arise via either cytochrome P450 oxygenation(23) or from aspirin triggered mechanisms(24). There was also an association obtained for levels of inflammation initiating eicosanoids PGE2 and TxB2, the further inactive metabolite of the vasoactive TxA2(6) (Figure 2A), in survivors.

Plasma from sepsis patients was obtained within 48h of admission to the BWH MICU (Day 1), Day 3 and Day 7. Samples were profiled using lipid mediator metabololipidomics. Gray circle 95% confidence regions (A, C, E) 2-dimensional score plots of plasma from sepsis survivors and non-survivors. (B, D, F) 2-dimensional loading plots. Results represents n= 13 sepsis survivors and 9 non-survivors.

LM profiles for survivors on Day 3 gave greater separation compared with non-survivors (Figure 2B) with R2 X = 0.4, R2 Y = 0.7, Q2 = 0.5. Profiles from non-survivors on Day 3 produced tighter clusters than on Day 1. The loading plot demonstrated an association with variable importance in projection scores >1 for lipoxin RvD5, RvE1, 17-epi-PD1 and 17-epi-RvD1 with non-survivors (Figure 2B). We also found an association of TxB2 and PGD2 with survivors with variable importance in projection scores for these products of ~1. Profiles from Day 7 also gave distinct clusters in survivors and non-survivors with R2 X = 0.4, R2 Y = 0.7, Q2 = 0.4 (Figure 2C). We found an association of between 17-epi-RvD3, RvE2 and RvD5 with non-survivors and LXB4, and 15epi-LXB4 with survivors each giving a VIP score >1.

Day 1 pro-resolving mediators PD1 (0.7±0.5 vs 0.0±0.0 pg/ml; p<0.05) and RvE1 (2.2±0.9 vs 0.0±0.0 pg/ml; p<0.05) were significantly higher in non-survivors vs. survivors. In non-survivors we noted a significant increase in PGF2α (Supplementary Table I), a potent airway smooth muscle contractant. At Day 3 we found significant increases in pro-resolving mediators RvD5 (4.9±2.7 vs 0.2±0.2 pg/ml; p<0.05), RvE1 (1.7±0.9 vs 0.3±0.2 pg/ml; p<0.05), 17-epi-RvD1 (2.6±1.0 vs 0.2±0.1 pg/ml; p<0.05) and 17-epi-PD1 (1.8±0.7 vs 0.3±0.3 pg/ml; p<0.05) and significant increases in PGF2α (3.3±1.2 vs 53.6±29.0 pg/ml; p<0.05) in non-survivors vs. survivors (Supplementary Table I). Day 7 levels of RvD5 (6.8±2.7 vs 0.4±0.3 pg/ml; p<0.05) and RvE2 (171.6±58.9 vs 68.8±21.0 pg/ml; p<0.05) were significantly increased in sepsis non-survivors vs. survivors (Supplementary Table I). PGF2α (51.3±25.7 vs 4.7±1.6 pg/ml; p<0.05) levels were elevated in non-survivors vs. survivors at Day 7.

To determine whether SPMs correlate with mortality more reliably than clinical variables, we performed a comprehensive analysis of clinical variables and traditional cytokines. Selected variables stratified by survivors vs. nonsurvivors (Table 2A) show significant increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines in nonsurvivors (TNF-α at all 3 time points; IL-6 and IL-8 at Day 7), significant reduction in platelet count in non-survivors (Days 3, 7), increased partial thromboplastin time in non-survivors (Day 7), significant reduction in serum bicarbonate level in nonsurvivors (Days 1,3), significant increase in intubation rates in non-survivors at (Days 3, 7), and significantly lower PaO2 and pH at Day 1 in non-survivors. Additional variables measured include total bilirubin levels and pressors use (higher in non-survivors), and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores (lower in nonsurvivors at 3 time points). Other variables not significantly different between survivors and non-survivors include full chemistries and liver function tests; use of therapeutic heparin, propofol, and total parenteral nutrition (TPN); use of vasopressors; and administration of antibiotics. We systematically compared the association between SPMs and mortality with the association between APACHE II and mortality (see Supplemental methods for details). While some SPMs were significantly correlated with mortality, with small sample size and low power, they did not predict survival more reliably than traditional clinical variables, so we next determined whether there was a subset of patients in whom SPM better predict clinical outcomes than traditional clinical variables.

Table 2

Clinical parameters and laboratory values assessed at Days 1, 3, and 7 in (A) Survivors vs. Nonsurvivors and (B) Sepsis vs. Sepsis/ARDS subjects.Clinical and laboratory data was abstracted from the database at indicated time points, and plasma collected from subjects at Days 1, 3, and 7 was subjected to measurement of cytokines (interleukin [IL]-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α) using commercially available ELISA kits

| Table 2A. Survivors Vs Non Survivors | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day | IL-1β* | IL-6* | IL-8* | TNF-α* | WBC | Hct | Plt | PT | |

| Survivors | Day 0 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 112.7 ± 177.1 | 145.5 ± 196 | 23.9 ± 16.3 | 8.6 ± 7.5 | 31.2 ± 4.1 | 201.5 ± 227.1 | 19.9 ± 4.6 |

| Day 3 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 420.2 ± 1366.7 | 187.4 ± 320 | 27.7 ± 19.8 | 8.7 ± 8.7 | 30.5 ± 3.4 | 200.7 ± 171 | 18.4 ± 3.3 | |

| Day 7 | 2.8 ± 3.7 | 42.9 ± 83.3 | 35.8 ± 21.9 | 22.6 ± 12.1 | 8.8 ± 4.4 | 29.6 ± 3.6 | 196 ± 127.6 | 17.1 ± 2.89 | |

| Non-Survivors | Day 0 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 611 ± 1135 | 620.2 ± 846.3 | 48.3 ± 22.3 (#) | 11.1 ± 11.2 | 29.2 ± 3.74 | 117.1 ± 66.2 | 22.8 ± 7.7 |

| Day 3 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 220.7 ± 202.1 | 567.5 ± 742.4 | 52.5 ± 25 (#) | 9.5 ± 7.5 | 27.5 ± 4.9 | 97.4 ± 77.1 (#) | 21 ± 8.6 | |

| Day 7 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 114.1 ± 81.7 (#) | 343.8 ± 233.5 (#) | 52.1 ± 31.8 (#) | 12.2 ± 7.8 | 28.1 ± 3 | 91.3 ± 90.6 (#) | 19.1 ± 6.6 | |

| Day | INR | PTT | HCO3 | Cre | TBili | PaO2 | PaCO2 | pH | %Intubated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivors | Day 0 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 51.3 ± 29.5 | 22.5 ± 5 | 1.6 ± 1.7 | 6.1 ± 7.1 | 78 ± 13.8 | 39.4 ± 7.9 | 7.4 ± 0.05 | 15 |

| Day 3 | 1.5 ± 3.5 | 44.2 ± 13.4 | 23.3 ± 4.3 | 1.5 ± 1.5 | 6.9 ± 8.6 | 79.5 ± 29 | 38 ± 7.1 | 7.4 ± 0.04 | 7 | |

| Day 7 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 35.9 ± 5.83 | 25.2 ± 4.3 | 1.2 ± 1.1 | 8.3 ± 11.6 | 125.5 ±70 | 40 ± 1.4 | 7.5 ± 0.04 | 15 | |

| Non-Survivors | Day 0 | 2 ± 0.9 | 57.9 ± 23.5 | 19.1 ± 3.4 (#) | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 1.1 ± 1.3 | 56.8 ±25 (#) | 33.4 ± 7 | 7.3 ± 0.08 (#) | 77 |

| Day 3 | 1.8 ± 1 | 45.5 ± 12.1 | 20.2 ± 2.6(#) | 2.1 ± 1.7 | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 76.9 ± 20.1 | 33.1 ± 5.8 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 66 (#) | |

| Day 7 | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 45.3 ± 14.1 (#) | 23.6 ± 5.2 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 0.8 ± 0.9 (#) | 95.9 ± 83.3 | 38.5 ± 11.3 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 77 (#) |

| Table 2B. Sepsis/ARDS vs Sepsis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day | IL-1β* | IL-6* | IL-8* | TNF-α* | WBC | Hct | Plt | PT | |

| Sepsis ARDS | Day 0 | 2.08 ± 1.04 | 194.60 ± 248.1 | 262.38 ± 216.6 | 33.27 ± 19.2 | 9.59 ± 9.55 | 31.62 ± 5.12 | 132 ± 122.3 | 23.57 ± 6.84 |

| Day 3 | 2.32 ± 1.37 | 1019.51 ± 1949.1 | 494.15 ± 498.4 | 45.86 ± 31.6 | 6.69 ± 5.4 | 28.2 ± 4.5 | 118.67 ± 129.4 | 22.22 ± 8.41 | |

| Day 7 | 3.57 ± 5.4 | 108.9 ± 105.2 | 214.01 ± 224.9 | 47.24 ± 32.8 | 10.71 ± 6.27 | 29 ± 3.41 | 120 ± 143.3 | 21.1 ± 7.68 | |

| Sepsis | Day 0 | 1.32 ± 0.4 | 362.25 ± 878.7 | 368.72 ± 688.3 | 34.05 ± 23.8 | 9.69 ± 9.1 | 29.92 ± 3.6 | 180 ± 201.2 | 20.14 ± 5.73 |

| Day 3 | 1.51 ± 0.7 | 83.25 ± 93.6 | 286.16 ± 576 | 34.8 ± 22.3 | 9.95 ± 8.8 | 29.66 ± 4.2 | 173.37 ± 155 | 18.46 ± 4.8 | |

| Day 7 | 1.62 ± 1.1 | 58.19 ± 80.5 | 142.23 ± 211.6 | 29.97 ± 22.8 | 10.03 ± 6.2 | 28.96 ± 3.5 | 165.63 ± 117.7 | 16.74 ± 2.5 | |

| Day | INR | PTT | HCO3 | Cre | TBili | PaO2 | PaCO2 | pH | %Intubated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis ARDS | Day 0 | 2.1 ± 0.77 | 47.28 ± 9.7 | 20.5 ± 4.23 | 1.53 ± 1.5 | 6 ± 9.3 | 70 ± 12.2 | 33.5 ± 4.9 | 7.35 ± 0.1 | 50 |

| Day 3 | 43.47 ± 12.7 | 1.93 ± 1 | 21.67 ± 4.8 | 2.22 ± 2.1 | 9.23 ± 12.3 | 80.25 ± 17.5 | 33.5 ± 6.6 | 7.35 ± 0.1 | 66 (#) | |

| Day 7 | 1.82 ± 0.9 | 44.12 ± 12.7 | 24.83 ± 5.5 | 1.35 ± 0.8 | 11.48 ± 15.32 | 69.25 ± 12.9 | 34.5 ± 4.8 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 66 | |

| Sepsis | Day 0 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 56.56 ± 30.9 | 21.38 ± 5 | 1.62 ± 1.5 | 2.16 ± 3.1 | 64.44 ± 28.1 | 38.63 ± 9.2 | 7.41 ± 0.1 | 25 |

| Day 3 | 1.53 ± 0.53 | 45.22 ± 13 | 22.12 ± 3.7 | 1.52 ± 1.4 | 2.09 ± 2.6 | 75.5 ± 23.3 | 34.5 ± 6.2 | 7.41 ± 0.1 | 18 | |

| Day 7 | 1.34 ± 0.3 | 38.1 ± 10 | 24.38 ± 4.4 | 1.26 ± 1 | 1.78 ± 2.2 | 123.5 ± 97.2 | 41.67 ± 12 | 7.41 ± 0.1 | 31 |

Clinical and laboratory values were extracted from the database, and plasma levels of cytokines (Interleukin [IL]-1b, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-a) were measured by commercially available ELISA kits. Data presented are means ± SD.

Abbreviations: WBC: White Blood Cell; Hct: Hematocrit; Plt: Platelets; PT: Prothrombin Time; PTT: Partial Thromboplastin Time; INR: International Normalized Ration; HCO3: bicarbonate; Cre: Creatinine; TBili: Total Bilirubin; PaO2, PaCO2: Partial Pressure of Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide dissolved in arterial blood; pH measured from arterial blood

Clinical and laboratory values were extracted from the database, and plasma levels of cytokines (Interleukin [IL]-1b, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-a) were measured by commercially available ELISA kits. Data presented are means ± SD.

Abbreviations: WBC: White Blood Cell; Hct: Hematocrit; Plt: Platelets; PT: Prothrombin Time; PTT: Partial Thromboplastin Time; INR: International Normalized Ration; HCO3: bicarbonate; Cre: Creatinine; TBili: Total Bilirubin; PaO2, PaCO2: Partial Pressure of Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide dissolved in arterial blood; pH measured from arterial blood

The significant increase in incidence of mechanical ventilation and lower PaO2 and pH values in non-survivors pointed toward increased respiratory failure in non-survivors, despite the fact that there was no significant difference in the number of subjects with ARDS between survivors and non-survivors (Table 1B). Furthermore, causes of death in non-survivors largely reflected sequelae of respiratory failure. We therefore stratified subjects by ARDS presence as an indicator of antecedent respiratory failure (i.e. sepsis, n=16 vs. sepsis/ARDS, n=6) (Table 1B) and examined LM (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 2). LM profiles in ARDS patients demonstrated separation from sepsis patients on Day 1 (Figure 3A). Analysis of loading plots demonstrated association (VIP score >1) of PGF2α with ARDS profiles whereas 17epi-RvD1 and RvD2 were associated with sepsis profiles (Figure 3B). Day 3 LM profiles gave better separation between the two clusters with X = 0.5, R2 Y = 0.7, Q2 = 0.5 (Figure 3C). We also found strong correlation between sepsis patients and a select group of pro-resolving mediators including 17epi-RvD1 and RvD2 (Figure 3D). These characteristic LM profiles were also observed at Day 7 from these two patient groups, giving distinct clusters (Figure 3E–F). In contrast to the correlation of a number of clinical variables with nonsurvival (Table 2A), other than the higher incidence of respiratory failure in the sepsis/ARDS group (which is expected), there was no significant correlation of major clinical variables with the development of ARDS (Table 2B). We systematically compared the associations between SPMs and and ARDS with the associations between APACHE II and ARDS development (see Supplemental Methods for details). Interestingly, we found that Day 3 amount of 10S,17S-diHDHA (also known as PDX) was significantly correlated with ARDS (p<0.001) and was a significantly better predictor of ARDS development than APACHE II score (r = 0.79 vs. 0.35, p<0.01, one sided). Our results highlight the difficulty of predicting ARDS using clinical variables, even in at-risk subjects, making the significant differences in SPMs between sepsis and sepsis/ARDS groups that much more striking.

Plasma from sepsis patients without (“Sepsis”) and with ARDS was obtained within 48h of admission to the BWH MICU (Day 1), Day 3 and Day 7. Samples were profiled using lipid mediator metabololipidomics. Gray circle 95% confidence regions (A, C, E) 2-dimensional score plots of plasma from sepsis survivors and non-survivors. (B, D, F) 2-dimensional loading plots. Results represents n= 16 sepsis without ARDS and 6 sepsis with ARDS.

Discussion

We report identification of pro-resolving mediators in sepsis patients (Table I) and temporal relationships to classic pro-inflammatory and vaso-active eicosanoids. We found elevated plasma levels of LM-SPM in non-survivors and that peripheral blood lipid mediator (LM) profiles correlate with ARDS development in sepsis patients. These profiles were observed at ICU Day 1 and persisted to Day 7, suggesting early measurements of LM-SPMs might serve as biomarkers, especially given that PGF2α was found to be a strong predictor of mortality in sepsis patients (Supplementary Table 1). Interestingly, protectin D1 isomer 10S,17S-diHDHA correlated with ARDS development in sepsis patients, while traditional clinical variables were poor predictors of ARDS development (Table 2). These peripheral blood lipid mediator profiles additionally indicate that in septic patients the inflammatory response also includes the vascular system with an alteration of the peripheral blood lipid mediator profile, an increase in lipid mediator production, and a failure to engage pro-resolving mechanisms.

We investigated circulating levels of known physiologic mediators involved in onset of inflammation and thrombosis (leukotrienes, prostaglandins and thromboxanes) (6) and resolution of acute and chronic inflammation, (SPM) (2, 7, 8, 10, 25) in sepsis patients with a variety of underlying conditions (Table 1). Regulation of circulating levels of distinct clusters of mediators was different in survivors versus non-survivors with a signature present on Day 1 that persisted to Day 7 (Figure 2). At Day 7 10S, 17S-diHDHA was a better predictor of ARDS development than the clinical APACHE II score indicating that this protectin pathway marker represents a new early biomarker that may help stratify patients upon MICU admission. In addition, non-survivors had higher circulating cytokines, lower platelet counts, and higher respiratory failure and ventilator dependence, further suggesting that SPMs correlate with outcomes in a subset of critically ill patients with respiratory failure (Supplementary-Table 1).

Platelet activation is associated with sepsis severity and correlates with organ failure (26). Resolvins regulate platelet activation and reduce adhesion molecule expression on platelets, leukocytes and endothelial cells, thereby preventing homotypic and heterotypic aggregates and transcellular biosynthesis of inflammation-initiating mediators including LTC4 (23, 27, 28). Aberrant platelet activation is also associated with cardiovascular complications. Aspirin, which acetylates cyclooxygenases, inhibiting prostaglandin and TxA2 production, jumpstarts resolution via production of aspirin triggered longer acting epimers of the lipoxins, resolvins and protectins by acetylated cyclooxygenase-2 (2, 6, 24). Here we identified AT-RvD1, AT-RvD3, AT-PD1 and AT-LXB4 in sepsis plasma that likely reflect aspirin acetylation of cyclooxygenase-2 or cytochrome P450 initiated mechanisms(23). In sepsis non-survivors we found significant increases in PGF2α (Table 2) and LTB4, the potent leukocyte chemoattractant (6), as well as increases select pro-resolving mediators including RvE1 and RvD5 (Table 2). Resolvins regulate cyclooxygenase-2 expression(29), one of the enzymes responsible for PGF2α biosynthesis, as well as the subcellular localization of 5-lipoxygenase switching leading to a switch from leukotriene to lipoxin production (30). Given potent biological actions of SPM (2, 7, 8, 10, 23) the present results suggest that the observed increases in the peripheral blood levels of these potent mediators in both sepsis non survivors and ARDS patients may not be adequate to prevent and/or reverse the disease sequelae in these patients giving rise to as status of failed resolution. The failure of these pro-resolving to regulate the inflammatory response may arise due to a failure of these mediators to interact with their cognate receptors potentially due to a downregulation of these receptors as observed for other host protective receptors in sepsis, a hypothesis which will need to be investigated in future studies.

Despite decades of sepsis research, there are no targeted therapies that control the unbridled inflammatory response and organ failure (3, 4). Many of the drugs tested, including anti-TNF-α agents and glucocorticoids, antagonize inflammatory responses by blocking upstream targets that catalyze dysregulated immune responses. However, inhibition of many of these pro-inflammatory pathways has not proven effective, likely due to the heterogeneity of molecular pathways activated in different patients and conditions. Importantly, anti-inflammatory treatments can also produce immune suppression that can be detrimental in host defense (3, 4). Since the immune response is critical for clearance of microbial pathogens, new approaches are needed that spare the innate immune response.

Since there was increased incidence of respiratory failure in nonsurvivors (Table 2A), we stratified SPMs by ARDS presence or absence (Figure 3) and found that LM-SPM profiles from ARDS patients were distinct from sepsis at Day 1 and persisted to Day 7. Sub-stratification of critically ill patients and prediction of ARDS development in at-risk patients is particularly challenging. Especially given our small cohort and severity of illness, the correlation of SPMs with ARDS in the absence of clinical predictors of ARDS development (Table 2B) and the observation that the protectin pathway is better associated with ARDS development then APACHE II score further highlight the relevance of SPMs to critical illness and development of respiratory failure. PD1 was also significantly reduced in exhaled breath condensates from asthmatic patients(31) indicating that the protectin pathway may be a component in lung homeostasis.

SPM govern the inflammatory response without disrupting immune cell function in pre-clinical animal models and isolated phagocytes (2, 7, 8, 10). SPM, including the D-series resolvins (RvD1, RvD2, RvD5), protectins (PD1) and lipoxins (LXA4 and LXB4) are also produced in non-human primates (15) and mice (8) during bacterial infections at concentrations commensurate with their bioactive ranges; levels are decreased in non-resolving infections (8). SPM promote clearance of bacteria, reduce local and systemic pro-inflammatory mediator production (8, 10, 11, 32), and promote tissue repair and regeneration (2, 7). SPM, such as the protectins, promote viral clearance via regulation of host responses (32), a property shared with RvE1 in Herpes simplex eye infections (33), and by inhibiting viral replication (11). Thus, our identification of SPM in peripheral blood at levels (~1–500 pM) is commensurate with their bioactive concentrations (0.1pM–10nM), suggesting they reflect physiological role(s) in human sepsis. It is noteworthy, that mediators upregulated in sepsis non- survivors including RvE1, RvD1, RvD5 and PD1 lower antibiotic requirements (8) and protect against inflammation-associated cognitive decline (34) and age-associated inflammation (35, 36) in animal infections. In addition to a regulation of lipid mediators in the non-survivors we also found increased levels of inflammatory cytokines (Table 2). These results suggest that in non-survivors there is widespread systemic inflammation and a status of failed resolution, where although there is an increase in endogenous pro-resolving mediator production, their levels are not adequate to resolve the ongoing inflammation, ultimately resulting in death.

The primary objective of our study was to identify LM-SPM and validate their structures in peripheral blood of sepsis patients and secondarily, to correlate levels with clinical outcomes. Using a patient cohort of 22 subjects that were randomly selected from those with available samples at all 3 time points, we observed striking profiles that distinctly separated sepsis survivors from non-survivors on Day 1, with persistence to Day 7, as well as sepsis patients that develop ARDS from those that do not. The selection of subjects with samples available for analysis at all three time-points over a 7-day period suggests that the findings made in the present study may have been even more robust if we had made prospective measurements in all-comers. Differences in co-morbidities may also have an impact on the observed lipid mediator profiles (Supplementary Table III). Indeed we found significant associations between co-morbidities and select lipid mediators including RvD1 with hematologic malignancies. Future studies will be important for prospective identification and monitoring of SPM in a larger cohort of sepsis and control subjects that will allow confirmation of their roles as potential biomarkers predictive of clinical outcomes. Such studies will allow analysis of sepsis subgroups, as SPM might have additional predictive value in subjects with the highest severity of illness. In addition, recent studies also demonstrate that s-RAGE (37, 38) and vWF (38, 39) are predictive biomarkers of outcome in sepsis, and thus it would be of future interest to determine the correlation of these biomarkers with SPM profiles in predicting outcomes in sepsis. In addition, a combination of these novel biomarkers may assist in providing better patient stratification.

We also identified the correlation between peripheral blood LM and outcomes in sepsis with significant increases in specific host protective mediators (RvE1, RvD5, 17-epi-RvD1, 17-epi-PD1, PD1) and a distinct signature upon ICU admission. In non-survivors, we also found significant increases in a potent airway smooth muscle constrictor PGF2α as well as correlation of SPM profiles with ARDS development and respiratory failure. Our results indicate that LM profiling can reflect patient status in critically ill subjects and sets the stage for LM-SPM signature profiling of pathway markers as a novel approach for evaluating outcomes and modulating treatment responses in sepsis.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Data File _.doc_ .tif_ pdf_ etc.__1

Supplemental Data File _.doc_ .tif_ pdf_ etc.__2

Supplementary Figure 1: Lipid mediator profiles of human sepsis patients:Plasma was collected from sepsis patients within 48h of hospitalization and stored at −80 °C prior to LM extraction and profiling using lipid mediator metabololipidomics (see methods for details). (A) MRM of signature ion pairs was obtained using the precursor ion (Q1) and a characteristic product ion (Q3) for each LM. Bioactive LM, isomers, and pathway markers were identified in human plasma from docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) bioactive metabolome, including D-series resolvins, maresins, and protectins; eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) bioactive metabolome - E-series resolvins; and arachidonic acid (AA) bioactive metabolome, including AA-derived lipoxins, leukotrienes, and prostanoids. Cumulative levels for individual LM families are depicted as a function of color intensity, where color scales (eg, white to blue) are set from zero to 300 pg per ml plasma. (B) MS-MS spectra employed for identification. Results are representative of n = 22 patients.

Supplemental Data File _.doc_ .tif_ pdf_ etc.__3

Supplemental Data File _.doc_ .tif_ pdf_ etc.__4

Supplementary Table 1. LM-SPM time-course in sepsis patients:Plasma was collected within 48 h of admission (Day 1) then on days 3 and 7 from (A) survivors and (B) non-survivors. Lipid mediators (LM) and their pathway markers were profiled using LM-metabololipidomics (see methods for details). Q1, M-H (parent ion) and Q3, diagnostic ion in the MS-MS (daughter ion). Results are expressed as pg/mL; mean ± SEM, n = 13 for survivors and n = 9 for non- survivors for each time point. The detection limit was ~ 0.1 pg. *, Below limits of detection. Bold values denote p<0.05 vs survivors.

Supplemental Data File _.doc_ .tif_ pdf_ etc.__5

Supplementary Table 2. ARDS patients display a characteristic LM-SPM profile:Plasma was collected within 48 h of admission (Day 1) then on days 3 and 7 from (A) sepsis patients without ARDS (“Sepsis”) and (B) sepsis patients with ARDS (ARDS). Lipid mediators (LM) and their pathway markers were profiled using LM-metabololipidomics (see methods for details). Q1, M-H (parent ion) and Q3, diagnostic ion in the MS-MS (daughter ion). Results are expressed as pg/mL; mean ± SEM, represents n= 16 sepsis without ARDS and 6 sepsis with ARDS for each time point. The detection limit was ~ 0.1 pg. *, Below limits of detection. Bold values denote p<0.05 vs survivors.

Supplemental Data File _.doc_ .tif_ pdf_ etc.__6

Supplmentary Table 3: Spearman Correlation between lipid mediators and their precursors/pathway markers and Demographic/Clinical Variables:We assessed for the presence of correlations between lipid mediators, their precursors and pathway marker levels and 29 different demographic and clinical variables for 22 subjects at Days 1, 3, and 7, with Spearman Correlations as indicated. *p<0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants P01-HL108801. The authors are grateful to members of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Registry of Critical Illness (RoCI): Drs. Laura Fredenburgh, Joshua Englert, Paul Dieffenbach, and Samuel Ash.

Abbreviations

| RvD1 | Resolvin D1 (7S,8R,17S-trihydroxy-docosa-4Z,9E,11E,13Z,15E,19Z-hexaenoic acid) |

| RvD2 | Resolvin D2 (7S,16R,17S-trihydroxy-docosa-4Z,8E,10Z,12E,14E,19Z-hexaenoic acid) |

| RvD5 | Resolvin D5 (7S,17S-dihydroxy-docosa-4Z,8E,10Z,13Z,15E,19Z-hexaenoic acid) |

| PD1 | Protectin D1 (10R,17S-dihydroxy-docosa-4Z,7Z,11E,13E,15Z,19Z-hexaenoic acid), also known as neuroprotectin D1 (NPD1) |

| RvE1 | Resolvin E1 (5S,12R,18R-trihydroxy-eicosa-6Z,8E,10E,14Z,16E-pentaenoic acid) |

| SPM | Specialized pro-resolving mediators |

| LT | Leukotriene |

| PG | Prostaglandin |

Footnotes

Author contribution:

J.D., R.A.C, C.Q., D.B., collected and analyzed data; S.H. analyzed data; J.D., R.A.C., C.Q., D.B., S.H., B.D.L., A.M.C, C.N.S and R.M.B contributed to manuscript preparation. C.N.S. conceived overall research plan.Copyright form disclosures: Dr. Baron received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Quintana received support for article research from the NIH and disclosed other support (Funding granted to her PI through a PPG). Dr. Levy received support for article research from the NIH and received funding from Resolvyx Pharmaceuticals and Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Choi received support for article research from the NIH. Dr. Serhan disclosed other support (CNS is an inventor on patents [resolvins] assigned to BWH and licensed to Resolvyx Pharmaceuticals. CNS was a scientific founder of Resolvyx Pharmaceuticals and owns equity in the company of unknown value. CNS’ interests were reviewed and are managed by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Partners HealthCare in accordance with their conflict of interest policies) and received support for article research from the NIH. He received funding (Lecture honoria from Metagenics, AUB Medical Center cardiology department, and Ester Lauder Research. Consulted for Corbis and Solutex and SAB member); received support from the NIH board of scientific advisers NIH/NIAAA honorarium; and received support from Corbis and Solutex SAB member. His institution received funding from the NIH/NIHLBI. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000002014

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc5549882?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1097/ccm.0000000000002014

Article citations

Pharmacological effects of specialized pro-resolving mediators in sepsis-induced organ dysfunction: a narrative review.

Front Immunol, 15:1444740, 20 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39372413 | PMCID: PMC11451296

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

The Role of Serum Albumin and Secretory Phospholipase A2 in Sepsis.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(17):9413, 30 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39273360 | PMCID: PMC11395451

Prostacyclin synthase deficiency exacerbates systemic inflammatory responses in lipopolysaccharide-induced septic shock in mice.

Inflamm Res, 73(8):1349-1358, 04 Jun 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38832966

Lipid mediators in neutrophil biology: inflammation, resolution and beyond.

Curr Opin Hematol, 31(4):175-192, 07 May 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 38727155

Review

The shifting lipidomic landscape of blood monocytes and neutrophils during pneumonia.

JCI Insight, 9(4):e164400, 22 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38385743 | PMCID: PMC10967382

Go to all (104) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Quantitative profiling of inflammatory and pro-resolving lipid mediators in human adolescents and mouse plasma using UHPLC-MS/MS.

Clin Chem Lab Med, 59(11):1811-1823, 12 Jul 2021

Cited by: 18 articles | PMID: 34243224

Pro-resolving lipid mediators in sepsis and critical illness.

Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 23(2):76-81, 01 Mar 2020

Cited by: 10 articles | PMID: 31904604

Review

Gene Expression of Proresolving Lipid Mediator Pathways Is Associated With Clinical Outcomes in Trauma Patients.

Crit Care Med, 43(12):2642-2650, 01 Dec 2015

Cited by: 30 articles | PMID: 26488221 | PMCID: PMC4651815

Trypanosoma cruzi Produces the Specialized Proresolving Mediators Resolvin D1, Resolvin D5, and Resolvin E2.

Infect Immun, 86(4):e00688-17, 22 Mar 2018

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 29358332 | PMCID: PMC5865043

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NHLBI NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: P01 HL108801

Grant ID: R01 HL112747

NIAID NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: U24 AI118656

NIGMS NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: P01 GM095467