Abstract

Free full text

Purinergic signaling in microglia in the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain

Abstract

Nerve injury often causes debilitating chronic pain, referred to as neuropathic pain, which is refractory to currently available analgesics including morphine. Many reports indicate that activated spinal microglia evoke neuropathic pain. The P2X4 receptor (P2X4R), a subtype of ionotropic ATP receptors, is upregulated in spinal microglia after nerve injury by several factors, including CC chemokine receptor CCR2, the extracellular matrix protein fibronectin in the spinal cord, interferon regulatory factor 8 (IRF8) and IRF5. Inhibition of P2X4R function suppresses neuropathic pain, indicating that microglial P2X4R play a key role in evoking neuropathic pain.

1. Introduction

Neuropathic pain is one of the most debilitating chronic pain states, and is evoked by nerve injury due to traumatic injury, infection, autoimmune diseases, diabetes mellitus or bone compression in cancer. Neuropathic pain is a heavy clinical burden because it is refractory to available medicines such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids.1) More than 20 million individuals worldwide suffer from the pain. In the past, almost many researchers believed that neuropathic pain after peripheral nerve injury was the direct result of alterations in neurons and neuronal functions in the peripheral and central nervous systems. Indeed, many studies have focused on neurons to understand the mechanism of neuropathic pain, which have suggested that neuropathic pain is a reflection of the aberrant excitability of the secondary sensory neurons in dorsal horn evoked by peripheral sensory inputs and anatomical reorganization of pain pathways of the peripheral and central nervous systems.1,2) As a result, most of the pharmacological tools aimed at treating this pain were directed against molecular targets in neurons; however, none did not produce optimal therapeutic effects in patients.3) The failure of these drugs targeted to neuron against neuropathic pain suggested that non-neuronal mechanisms are involved in neuropathic pain. Recently, there is a rapidly growing body of evidences showing that glial cells, including spinal microglia, activated in response to peripheral nerve injury (PNI) have important pathological roles in the modification of synaptic transmission of pain signaling.4–8)

It is thought that microglia derive from primitive macrophages in the yolk sac.9) In normal conditions, microglia are ubiquitously distributed in the spinal cord and brain, and have small cell bodies bearing branched and motile processes, which seem to monitor the local environment.10,11) In the pathophysiological condition after PNI, microglia are activated, change morphologically, increase in cell number, and alter the expression of genes, including neurotransmitter receptors, such as P2 purinergic receptors, in the spinal cord.5,12–14) Activated microglia express several subtypes of ionotropic (P2XRs) and metabotropic P2 receptors (P2YRs). Extracellular ATP stimulates microglial P2 receptors to evoke various cellular responses such as the production of cytokines and neurotrophic factors.15) We have reported that P2 receptors (especially P2X4Rs) play a key role in evoking and maintaining neuropathic pain,8,16,17) which was a breakthrough for the field.

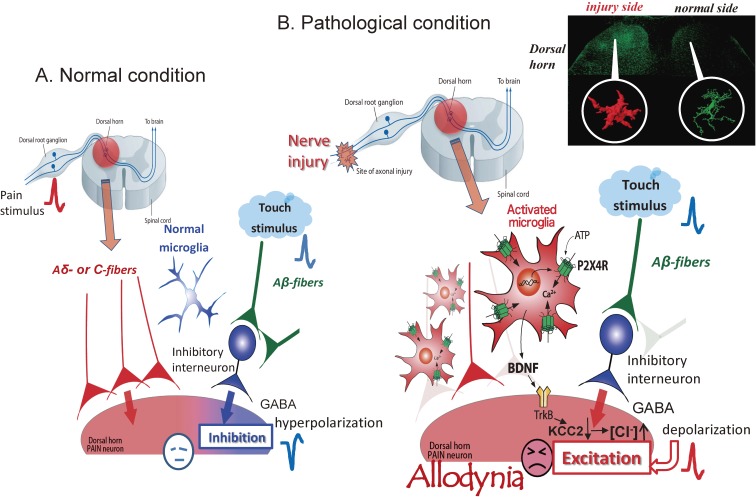

The symptoms of neuropathic pain include spontaneous pain, hyperalgesia and tactile allodynia (pain hypersensitivity to normally innocuous stimuli). Tactile allodynia is an interesting shift in sensation elicited by sensory inputs that is not seen in physiological conditions. In normal conditions, painful stimuli evoke action potentials in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons (C-fibers or Aδ fibers). These spikes transmit to lamina I secondary sensory neurons in dorsal horn, and finally to sensory cortex evoking a pain sensation. Touch stimuli evoke action potentials in Aβ fibers that transmit to sensory cortex, evoking a touch sensation. There is no overlap of these sensory inputs in the normal condition, thus the phenomenon of tactile allodynia is particularly interesting and important in clinical matter. In this paper, I describe recent advances in understanding the mechanism of evoking tactile allodynia in neuropathic pain through the functions of P2X4 receptors in spinal microglia after PNI.

2. Activation of microglia

Various lines of evidence proposing that the injured neurons themselves might trigger this activation of spinal microglia,18,19) however, it is currently not sure which factors are essential in activation of microglia. I present here data for the candidate of activation factors such as cytokine interferon (IFN)-γ and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) for evoking microglial activation.

It was reported that IFN-γ levels are increased in the spinal cord after nerve injury.20) And, we reported that in naive animals, spinal microglia express a receptor for IFN-γ (IFN-γR) in a cell-type specific manner and that stimulation of this receptor changes microglia into activated form and produces a long-lasting tactile allodynia.21) The treatment for ablating IFN-γR severely impairs nerve injury-evoked microglia activation and tactile allodynia. We also found that IFN-γ-stimulated spinal microglia show upregulation of Lyn tyrosine kinase and purinergic P2X4 receptor.21) These results suggest that IFN-γR is a key element in the activation of microglia resulting in neuropathic pain.

It also reported that PDGF expressed in dorsal horn neurons contributes to neuropathic pain after nerve injury,22) though how PDGF produces pain hypersensitivity remains unknown. We reported an involvement of spinal microglia in PDGF evoking tactile allodynia.23) A single intrathecal delivery of PDGF B-chain homodimer (PDGF-BB) to naive rats evoked a strong and long-lasting tactile allodynia in a dose-dependent manner. The immunofluorescence for phosphorylated PDGF β-receptor (p-PDGFRβ), an activated form, was markedly increased in the spinal dorsal horn by the administration of PDGF. It was noted that almost all p-PDGFRβ-positive cells were microglia. PDGF-stimulated microglia in vivo transformed into a modest activated state in terms of their cell number and morphology. Also, intrathecal administration of minocycline, which is known to inhibit microglia activation, inhibited PDGF-BB-induced tactile allodynia. These findings suggest that PDGF causes activation of spinal microglia resulting in tactile allodynia.

3. P2X4 receptors in activated microglia

We first observed by the behavioral pharmacological methods that tactile allodynia after PNI is reversed by a pharmacological blocker of P2X4Rs in the spinal cord.17) We have also shown by the immunohistochemical methods that expression of P2X4Rs in the spinal cord is upregulated exclusively in microglia after PNI. Furthermore, we and another group have reported by the behavioral pharmacological methods that animals with P2X4R knock-down or knock-out in the spinal cord are resistant to PNI-induced tactile allodynia.17,24,25) These results indicate that PNI-induced allodynia depends on signaling via microglial P2X4Rs.

Stimulation of microglial P2X4Rs evokes the synthesis and release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).24,26) We have shown that BDNF may cause downregulation of the chloride transporter KCC2 in a subpopulation of lamina I secondary sensory neurons in dorsal horn, which then causes a depolarizing shift in the anion reversal potential (Eanion).27) This shift inverts the polarity of currents activated by γ-amino butyric acid (GABA) and glycine, such that GABA and glycine cause depolarization, rather than hyperpolarization, in these secondary sensory neurons.27) ATP stimulation evokes the release of BDNF from microglia in vitro, and BDNF injection mimics the alteration in Eanion in vivo. Further, inhibition of the interaction between BDNF and the receptor TrkB reverses the allodynia and the Eanion shift that follows both nerve injury and ATP-stimulated microglia.27) These studies suggest that microglial P2X4Rs are central players in the pathogenesis of tactile allodynia in neuropathic pain (Fig. (Fig.11).

The hypothesis of evoking allodynia through P2 purinergic receptor P2X4R stimulation in activated microglia after peripheral nerve injury (PNI). (A) In normal conditions, painful stimuli evoke action potentials in dorsal root ganglion neurons (C-fibers or Aδ fibers). These spikes transmit to lamina I secondary sensory neurons in the dorsal horn (dorsal horn pain neurons), and finally to cortex. Touch stimuli evoke action potentials in Aβ fibers that partly transmit to inhibitory interneurons, resulting in the release of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). GABA acts as an inhibitory transmitter to lamina I secondary neurons, resulting in hyperpolarization and the inhibition of pain signaling. (B) Nerve injury activates dorsal horn microglia to overexpress P2X4Rs. ATP from dorsal horn neurons stimulates microglial P2X4Rs to cause the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF stimulates TrkB receptors of lamina I secondary sensory neurons in dorsal horn to cause down-regulation of the potassium-chloride transporter KCC2, resulting in an increase in intracellular [Cl−] and a depolarizing shift in the anion reversal potential (Eanion). This shift inverts the polarity of currents activated by GABA and glycine, such that GABA and glycine cause depolarization, rather than hyperpolarization, in these secondary sensory neurons. In this condition, touch stimulation causes GABA release from inhibitory interneurons. GABA opens Cl− channels of lamina I secondary neurons and leads to Cl− outflow, resulting in the depolarization of these neurons to evoke action potentials that reach cortex and evoke pain sensation. In this way, touch stimulation shifts to allodynia.

4. Regulation of P2X4R expression in activated microglia

We previously reported that the chemokine C-C motif ligand 21 (CCL21) is induced in injured DRG and is transported from DRG to the central terminals of dorsal horn neurons.28) In the same study, we also showed that the injection of a CCL21-neutralizing antibody attenuates microglial P2X4R upregulation and tactile allodynia in mice after PNI. The addition of CCL21 in vitro increases the expression of P2X4R in cultured microglia. Also, intrathecal injection of CCL21 causes tactile allodynia in CCL21-deficient mice after PNI. These findings suggest that CCL21 from injured DRG neurons contributes directly to P2X4R expression in microglia and neuropathic pain.28)

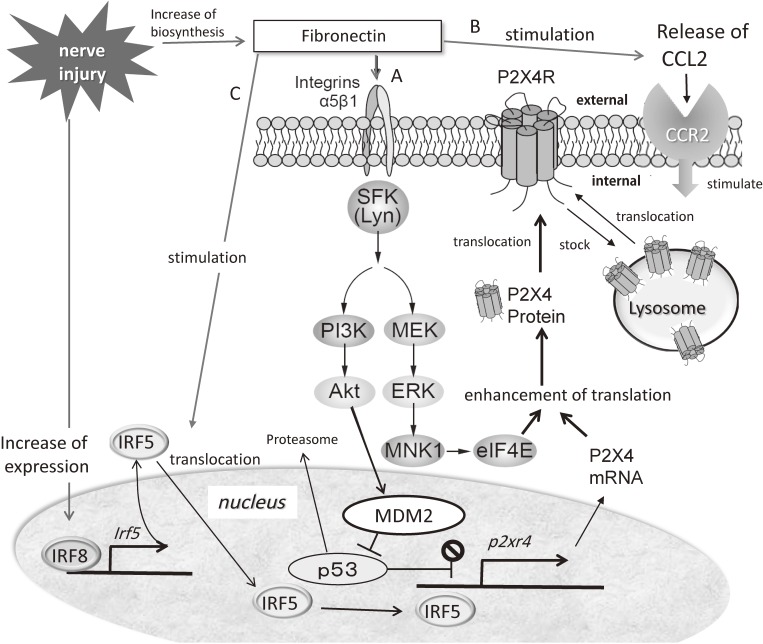

Because the functions of the blood–spinal cord barrier collapse after PNI,29,30) it is possible that proteins, including extracellular matrix protein fibronectin, from the blood might change the functions of microglia expressing P2X4R. We first reported that the protein level of fibronectin is elevated in the dorsal horn after PNI.31) Fibronectin also evokes an increase in mRNA and protein of P2X4R in primary cultured microglial cells.31) Moreover, we have reported that integrin blockers, which inhibit fibronectin/integrin signaling, reduce overexpression of P2X4R and tactile allodynia.32) Further, intrathecal administration of fibronectin produces tactile allodynia in naïve animals, but does not produce allodynia in P2X4R-deficient mice.32) Lyn tyrosine kinase, a member of Src-family kinases (SFKs), is an important molecule of fibronectin/integrin signaling in microglia, as microglial cells lacking Lyn fibronectin fail to cause the upregulation of P2X4R gene expression.33) Lyn is the main SFK in spinal microglia33) amongst the five members (Src, Fyn, Lck, Yes, and Lyn) that are expressed in the CNS.34) The expression of Lyn is highly restricted to microglia in the spinal cord, and the level of Lyn increases after PNI33) in an interferon-γ-dependent manner in vivo.13) In mice lacking Lyn, tactile allodynia and the upregulation of P2X4R are suppressed in spinal microglia after PNI.33)

We have also shown that two distinct intracellular signaling cascades are activated downstream of Lyn tyrosine kinase.35) One is a pathway through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt, and the other is through mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase (MEK)-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK).35) P2X4 gene expression is inhibited by p53. Activation of the PI3K-Akt pathway causes the degradation of p53 in a proteasome-dependent manner, which in turn leads an enhancement of P2X4 gene expression. Activated MEK-ERK signaling by fibronectin in microglia enhances eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) phosphorylation through the activation of MAPK-interacting protein kinase-1, which may play a role in regulating P2X4 expression. It has been reported that pharmacological inhibition of SFK effectively suppresses ERK activity in spinal microglia.36) Therefore, the Lyn-ERK signaling pathway appears to be active in spinal microglia after PNI. These results indicate that Lyn might be a key kinase in the upregulation of P2X4R in microglia (Fig. (Fig.22).

Increase of P2X4R expression through the actions of fibronectin in activated microglia after nerve injury. (A) Fibronectin increases after nerve injury and binds to α5β1 integrin on microglial cells, resulting in the activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK-ERK) signaling cascades through the action of the tyrosine kinase Lyn. Signaling through the PI3K-Akt pathway induces degradation of p53 via MDM2 and enhances P2X4R gene expression. Activated MEK-ERK signaling enhances eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) phosphorylation via activated MAPK-interacting protein kinase-1 (MNK1), which may lead to enhancement of P2X4R translation. Thus, fibronectin enhances the expression of functional P2X4Rs. (B) The subcellular localization of P2X4R is restricted to lysosomes and is translocated into the cell membrane by stimulation. Fibronectin increases the release of CCL2 from activated microglia and CCL2 stimulates the CC chemokine receptor CCR2, resulting in the stimulation of P2X4R trafficking to the cell surface from lysosomes of microglia. (C) Interferon 8 (IRF8) expression is markedly enhanced in microglia after PNI. IRF8 binds directly to the promoter loci of IRF5 and activates the transcription of IRF5, resulting in the increase of IRF5. Fibronectin activates IRF5 to translocate it from the cytosol to the nucleus. IRF5 induces de novo expression of P2X4R by binding directly to the promoter region of the P2rx4 gene. Altogether, fibronectin has a very important role for the expression of P2X4R after nerve injury.

A very interesting finding shows that the subcellular localization of P2X4R is restricted to lysosomes around the perinuclear region, and these P2X4 receptors are translocated into the cell membrane by stimulation.37) However, it was unclear on the type of stimulation needed to evoke such translocation. We have reported that stimulation by fibronectin increases the release of CCL2 from activated microglia, and CCL2 stimulates the CC chemokine receptor CCR2 of microglia resulting in the stimulation of P2X4R trafficking to the cell surface from lysosomes of microglia38) (Fig. (Fig.2).2). As mentioned above, fibronectin is a key regulator of P2X4R expression. It is well known that CCL2 or CCL21 is a member of CC chemokines. Chemokines are functionally divided into two groups, homeostatic and inflammatory one. This classification is not strict but basically homeostatic chemokines are constitutively produced in certain tissues and are responsible for migration of basal leukocyte. Inflammatory chemokines are formed under pathological conditions on pro-inflammatory stimuli and actively participate in the inflammatory response to attract immune cells to the inflammation site. CCL2 is an inflammatory chemokine and CCL21 is a homeostatic chemokine.

5. Transcriptional factors of microglia relating neuropathic pain

IRF8 is a member of the IRF family (IRF1–9) and is expressed in immune cells such as lymphocytes and dendritic cells.39) We and other groups have found that IRF8 is a transcription factor in microglia,40–43) and is critical for microglial activation and neuropathic pain.40) We have also found that IRF8 expression is markedly enhanced in microglia, but not in neurons or astrocytes, in the spinal cord after PNI.40) IRF8 expression is upregulated as early as day 1, peaks on day 3, and the upregulation persists for at least several weeks after PNI. PNI-induced tactile allodynia is prevented in IRF8-deficient mice without any change in basal mechanical sensitivity. Intrathecal injection of a small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting IRF8 in wild-type mice inhibits the upregulation of spinal IRF8 and allodynia after PNI. This indicates that activation of IRF8 is ongoing in spinal microglia after nerve injury. We have also revealed by in vitro and in vivo studies that IRF8 promotes the transcription of P2X4R and the innate immune response toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), chemokine receptor CX3CR1, interleukin-1β, cathepsin S, P2Y12R and BDNF that are involved in neuropathic pain.40)

We have shown that IRF5 directly controls the transcription of P2X4R in microglia after PNI.44) Importantly, IRF5 is an IRF8-regulated gene and increases in an IRF8-dependent manner in microglia after PNI. Further, fibronectin stimulates the translocation of IRF5 from the cytoplasm into the nucleus. Then, IRF5 binds directly to the promoter region of the P2rx4 gene in the nucleus and induces de novo expression of P2X4R in microglia. We have not found any upregulation of spinal P2X4R after PNI in mice lacking Irf5, and these mice do not show any pain hypersensitivity. These findings suggest that a transcriptional axis from IRF8 to IRF5 contributes to the tactile allodynia of neuropathic pain by the activation of spinal microglia with P2X4R overexpression after PNI (Fig. (Fig.22).

6. Where does ATP come from?

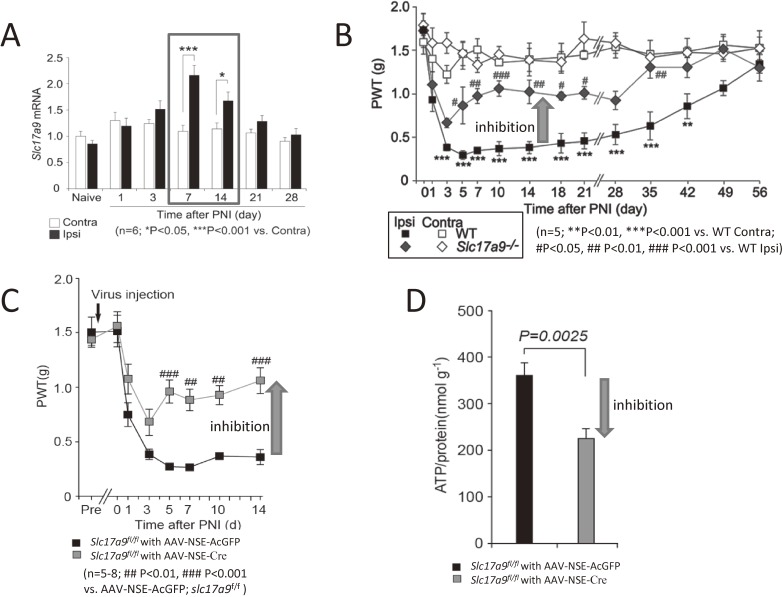

As discussed above, extracellular ATP in the spinal dorsal horn stimulates microglia to exert essential roles in neuropathic pain after PNI. However, the type of cells and the mechanism for ATP release within the spinal cord has remained a mystery for a long time. Very recently, we identified the vesicular nucleotide transporter (VNUT) in dorsal horn neurons as a key molecule for ATP release and neuropathic pain.45) The expression of VNUT (Fig. (Fig.3A),3A), extracellular ATP content ([ATP]e) within the spinal cord, and pain hypersensitivity all increase after PNI in wild-type mice.45) The increased [ATP]e is prevented in VNUT-deficient mice and inhibited by exocytosis inhibitors. Also, the tactile allodynia of neuropathic pain is prevented in VNUT-deficient mice (Fig. (Fig.3B).3B). The suppression of tactile allodynia and spinal [ATP]e is reproduced in mice with a specific deletion of VNUT in dorsal horn neurons (Fig. (Fig.3C,3C, D), but not in primary sensory neurons, microglia or astrocytes.45) Thus, the VNUT-dependent release of ATP from spinal dorsal horn neurons is likely important for the production of tactile allodynia in neuropathic pain.

ATP-vesicular nucleotide transporter (VNUT) in dorsal horn neurons is required for neuropathic pain. (A) PNI-induced upregulation of VNUT in the spinal cord. Real-time PCR analysis of Slc17a9 (VNUT) mRNA in total RNA extracted from spinal cord ipsilateral and contralateral to PNI before (naive) and after PNI. Values represent the relative ratio of Slc17a9 mRNA (normalized to the value for 18s mRNA) to the contralateral side of naive mice (n = 6; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni test). The expression of VNUT increased after PNI. (B) VNUT deficiency attenuates PNI-induced pain hypersensitivity. The paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) of Slc17a9−/− mice and WT littermates (Slc17a9+/+) before and after PNI (n = 5; ***P < 0.001 vs. the contralateral side of Slc17a9+/+ mice; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. the ipsilateral side of Slc17a9+/+ mice, two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni test). The tactile allodynia of neuropathic pain was inhibited in VNUT-deficient mice. (C) PWT of Slc17a9fl/fl mice intraspinally injected with AAV-NSE-AcGFP or an AAV-NSE-Cre viral vectors before and after PNI (n = 5–8; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. AAV-NSE-AcGFP; Slc17a9fl/fl, two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni test). The tactile allodynia was inhibited in mice with a specific deletion of VNUT in dorsal horn neurons. (D) Measurement of extracellular ATP content in the ACSF media of spinal cord slices isolated from Slc17a9fl/fl mice intraspinally injected with AAV-NSE-AcGFP or AAV-NSE-Cre viral vectors 7 days after PNI (n = 6, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test). Values are means ± s.e.m. The increase of spinal [ATP]e was inhibited in mice with a specific deletion of VNUT in dorsal horn neurons. All data in A-D was obtained by the method in Ref. 45.

7. P2X4 and clinical uses

The data on P2X4Rs discussed above indicate that P2X4R in activated microglia is a central player in evoking tactile allodynia of neuropathic pain, and a potential target of new treatments for neuropathic pain. Tactile allodynia is also observed in various diseases in humans including herpes zoster, Landry-Guillain-Barré syndrome, and multiple sclerosis. Indeed, we have shown strong activation of spinal microglia and overexpression of P2X4R in activated microglia in animal models of each of these diseases.46) This indicates that P2X4R inhibitors may also attenuate tactile allodynia in these diseases.

In modern medicine, morphine and other opiates are thought to be the most important analgesics. Morphine and opiates, however, can cause paradoxical hyperalgesia, eliciting strong pain in humans. It has recently been reported that P2X4R are essential for morphine-induced hyperalgesia (MIH) through a P2X4R-BDNF-KCC2 disinhibition cascade in microglia and dorsal horn neurons.47,48) It was found that downregulation of the K+-Cl− co-transporter KCC2 and impaired Cl− homeostasis in the dorsa horn lamina I neurons cause MIH.48) MIH is reversed without affecting tolerance when the anion equilibrium potential is restored or spinal microglia are ablated. It is very interesting that MIH requires µ-opioid receptor-dependent expression of P2X4Rs in microglia and µ-independent gating of the release of BDNF by P2X4Rs. MIH is inhibited by the treatment of BDNF-TrkB signaling blocker preserving Cl− homeostasis. It is also important that gene-targeted mice in which the Bdnf gene is deleted from microglia do not show MIH, but rather morphine antinociception.48) We have examined whether microglial BK channels are involved in the generation of MIH and antinociceptive tolerance, and showed that BK channels of microglia are responsible for the generation of MIH and antinociceptive tolerance, which are inhibited by pharmacological blockers or the genetic deletion of BK channels in microglia.49) After chronic stimulation of µ-opioid receptors by morphine, the concentration level of arachidonic acid (AA) or its metabolites increase through the activation of PLA2. Increased AA directly activates BK channels in microglia, resulting in increased efflux of K+ to cause the reduction of the intracellular cation concentration, which becomes the driving force of the Ca2+ influx via store operated calcium entry. An increase in intracellular Ca2+ facilitates the membrane translocation of P2X4Rs from lysosomes in microglia. The stimulation of functional P2X4Rs increases the synthesis and release of BDNF from microglia, resulting in MIH. Thus, BK channels in microglia may play a crucial role in evoking MIH. Altogether, the inhibitor of P2X4R may act as a treatment against MIH without affecting morphine analgesia.

8. Ending remarks

I described recent advances in the understanding of mechanisms of neuropathic pain, with a focus on the functions of P2X4 receptors in spinal microglia after PNI. Spinal microglia also express other purinergic receptors, including P2X7, P2Y12 and P2Y6, which show very interesting functions related to neuropathic pain. It was reported that P2Y12 is a key molecule inducing chemotaxis50) and is related to neuropathic pain,51,52) and P2Y6 is a key receptor to activate microglial phagocytosis.53) The role of purinergic signaling in microglia in the mechanisms of neuropathic pain provides exciting insights in its pathogenesis, and suggests potential strategies for developing new treatments for neuropathic pain.

Profile

Kazuhide Inoue was born in Fukuoka Prefecture in 1951 and graduated from Kyushu University in 1973. He worked as a researcher in the National Institute for Health Sciences and received Ph.D. degree in 1985 from Kyushu University. He became a Professor of the Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Science, Kyushu University in 2000. Since 2014, he has been serving as an Executive Vice-President of Kyushu University. He reported a new role of spinal microglia in evoking neuropathic pain through the function of P2X4 receptors, a subtype of ATP receptors. This paper was a breakthrough for the field and made new movement of the pain research. He continued research to reveal the functions of many ATP receptors expressed in microglia on the synaptic transmission resulting in strong pain and then received a Medal with Purple Ribbon from His Majesty the Japanese Emperor in 2014 for these findings. He also received a Medal from His Majesty the Spanish Emperor as a member of Royal Academy of Pharmacy in 2010.

References

Articles from Proceedings of the Japan Academy. Series B, Physical and Biological Sciences are provided here courtesy of The Japan Academy

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.93.011

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/pjab/93/4/93_PJA9304B-02/_pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Neuropathic pain in burn patients - A common problem with little literature: A systematic review.

Burns, 50(5):1053-1061, 28 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38472004

Review

Mechanism of IRF5-regulated CXCL13/CXCR5 Signaling Axis in CCI-induced Neuropathic Pain in Rats.

Curr Mol Med, 24(7):940-949, 01 Jan 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37622691

Research trends and hotspots of neuropathic pain in neurodegenerative diseases: a bibliometric analysis.

Front Immunol, 14:1182411, 12 Jul 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37503342 | PMCID: PMC10369061

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of microglia in maintenance of brain homeostasis and neurodegeneration.

Front Mol Neurosci, 15:1072046, 09 Jan 2023

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 36698776 | PMCID: PMC9870594

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Microglia activation in central nervous system disorders: A review of recent mechanistic investigations and development efforts.

Front Neurol, 14:1103416, 07 Mar 2023

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 36959826 | PMCID: PMC10027711

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (21) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Neuropharmacological Study of ATP Receptors, Especially in the Relationship between Glia and Pain.

Yakugaku Zasshi, 137(5):563-569, 01 Jan 2017

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 28458288

Review

Role of the P2X4 receptor in neuropathic pain.

Curr Opin Pharmacol, 47:33-39, 14 Mar 2019

Cited by: 25 articles | PMID: 30878800

Review

Transcription factor IRF5 drives P2X4R+-reactive microglia gating neuropathic pain.

Nat Commun, 5:3771, 13 May 2014

Cited by: 110 articles | PMID: 24818655 | PMCID: PMC4024744

[Mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain revealing by the role of glial cells].

Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi, 35(1):1-4, 01 Feb 2015

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 25816633

Review