Abstract

Free full text

Outbreak of Zika Virus Infections, Dominica, 2016

Abstract

In February 2016, the World Health Organization declared the pandemic of Zika virus a public health emergency. On March 4, 2016, Dominica reported its first autochthonous Zika virus disease case; subsequently, 1,263 cases were reported. We describe the outbreak through November 2016, when the last known case was reported.

Zika virus is a flavivirus transmitted primarily by Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes. The rapid spread of Zika virus from Brazil throughout the Americas, and the associated emergence of Zika congenital syndrome, which causes microcephaly and other birth defects, has posed an unprecedented challenge to global health (1,2). Zika virus spread through the Caribbean region early in the pandemic. In epidemiologic week 19 of 2015, Brazil reported its first confirmed locally acquired cases. Autochthonous transmission in Martinique was first reported in epidemiologic week 51 of 2015, and the first case originating in Puerto Rico was reported in week 52 of 2015 (3). Many other islands began reporting cases of Zika virus infection early in 2016. However, case data from several Caribbean countries has yet to be consolidated and described outside of reports by the Pan American Health Organization.

We defined suspected Zika virus disease cases in the Commonwealth of Dominica, on the eastern sector of the Caribbean Sea, by using guidelines provided by the Pan American Health Organization (4). Active surveillance of cases (suspected and confirmed) among persons who visited health clinics started as early as January 2016; however, the first laboratory-confirmed autochthonous case of Zika virus disease was identified in March 2016. We collected data from records in the Ministry of Health and Environment, Dominica, describing patients’ age, sex, residence, date of illness onset, clinical features, laboratory diagnoses, and travel history.

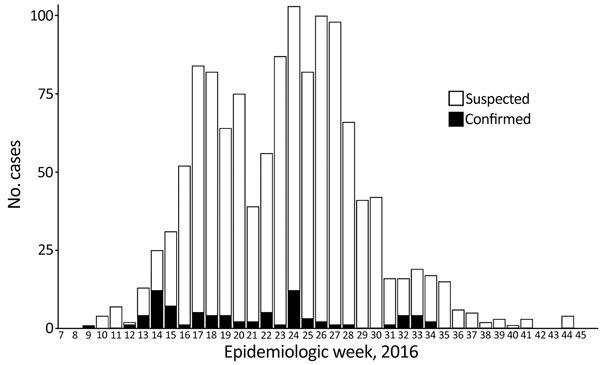

The first case of laboratory-confirmed Zika virus disease in Dominica was reported on March 4, 2016 (during epidemiologic week 9), in a 28-year-old woman. New cases (suspected and confirmed) were reported that year through November 6 (Figure). The last cases in 2016 were reported in epidemiologic week 44. A total of 1,263 suspected cases of Zika virus disease were reported in Dominica in 2016, of which 79 (6.25%) were confirmed by using reverse transcription PCR. Of these, only 1 specimen tested negative but was classified as a suspected case.

Sex was reported for 1,255 (99.3%) of 1,263 case-patients. Approximately twice as many case-patients were female (863, 68.8%) than male (392, 31.2%), which is consistent with a female bias found in other reports on Zika virus disease outbreaks (5).

Age was reported for 1,245 (98.6%) of 1,263 case-patients. Mean age was 28 years (median 27, range <1–94 years). Of those, 217 (17.4%) case-patients were children <10 years of age and 756 were of reproductive age (15–49 years); 555 (73.4%) of reproductive age case-patients were women.

Of the 1,240 case-patients for whom age and sex were reported, 555 (44.8%) were women of childbearing age. Pregnancy status was only reported for 54 (6.3%) of 863 female case-patients; of those, 16 (29.6%) were pregnant. Of the 16 pregnant women, 11 were confirmed case-patients, and disease was suspected in 5.

Of the 1,263 total case-patients, clinic visit dates were recorded for 1,123 (88.9%), and 27 (2.1%) reported hospitalizations. The average number of days between the onset of symptoms and initial clinic visit was 1.96 (n = 1,109; 5%, 95% quantiles = 0, 5); the average number of days between a recorded clinic visit and case reporting was 0.5 (n = 1,096; 5%, 95% quantiles = 0, 10). Of the 27 (15 female/11 male/1 unknown) hospitalizations, 2 were for women reported to be pregnant, and 6 were for children <10 years of age.

Aedes spp. mosquitoes are widespread throughout the Caribbean and are associated with Zika, dengue, and now chikungunya viruses, which are endemic to many islands. As part of the broader pandemic in the Americas, the Zika virus disease outbreak in Dominica highlights that the presence of Aedes spp. can be predictive of outbreaks. Dominica has a population of ≈72,000, on an island of 750 km2, and ≈1.67% of the population were reported to have suspected or confirmed cases of Zika virus disease in 2016.

We found a bias toward infection in women, including a substantial number of women of childbearing age, highlighting the potential vulnerability of pregnant women and unborn children. As was seen during the recent epidemic of chikungunya in Dominica (6), the rapid proliferation of Zika virus disease cases emphasizes the need to strengthen local capacities for targeted vector control and global efforts to support development of effective vaccines, in addition to a better understanding of the role of sexual transmission and the heightened risk to vulnerable populations such as pregnant women.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible by a partnership between the Caribbean Institute of Meteorology and Hydrology (CIMH) and an international team of investigators examining the eco-epidemiology and climate drivers of dengue fever, chikungunya, and Zika virus disease in the Caribbean. This project was undertaken through the United States Agency for International Development’s Programme for Building Regional Climate Capacity in the Caribbean Programme, executed by the World Meteorological Organization, and implemented by CIMH. This initiative has brought together the national and regional health and climate sectors (Dominica Ministry of Health, Dominica Meteorological Service, Caribbean Public Health Agency, Pan American Health Organization, CIMH). We are grateful for this partnership and cooperation.

This study was solicited by the Caribbean Institute for Meteorology and Hydrology through the United States Agency for International Development’s Programme for Building Regional Climate Capacity in the Caribbean Programme; funding was made possible by the generous support of the American people.

Biography

Dr. Ryan is an associate professor of medical geography in the Department of Geography and the Emerging Pathogens Institute at the University of Florida; her research focuses on quantitative spatial ecology at the human interface and its implications for disease, conservation, and management. Mr. Carlson is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, & Management at the University of California, Berkeley; his research focuses on the ecology of disease at the human–wildlife interface and the role of climate change in disease emergence.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Ryan SJ, Carlson CJ, Stewart-Ibarra AM, Borbor-Cordova MJ, Romero MM, Cox SA, et al. Outbreak of Zika virus infections, Dominica, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017 Nov [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2311.171140

1These authors contributed equally to this article.

References

Articles from Emerging Infectious Diseases are provided here courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2311.171140

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/23/11/pdfs/17-1140.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Prevalence of Mosquito Populations in the Caribbean Region of Colombia with Important Public Health Implications.

Trop Med Infect Dis, 8(1):11, 25 Dec 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 36668918 | PMCID: PMC9867490

Clinical Laboratory Biosafety Gaps: Lessons Learned from Past Outbreaks Reveal a Path to a Safer Future.

Clin Microbiol Rev, 34(3):e0012618, 09 Jun 2021

Cited by: 7 articles | PMID: 34105993 | PMCID: PMC8262806

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Clinical manifestations and health outcomes associated with Zika virus infections in adults: A systematic review.

PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 15(7):e0009516, 12 Jul 2021

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 34252102 | PMCID: PMC8297931

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Coordination among neighbors improves the efficacy of Zika control despite economic costs.

PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 14(6):e0007870, 22 Jun 2020

Cited by: 7 articles | PMID: 32569323 | PMCID: PMC7332071

Identifying high risk areas of Zika virus infection by meteorological factors in Colombia.

BMC Infect Dis, 19(1):888, 24 Oct 2019

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 31651247 | PMCID: PMC6814059

Go to all (9) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Travel-Associated Zika Cases and Threat of Local Transmission during Global Outbreak, California, USA.

Emerg Infect Dis, 24(9):1626-1632, 01 Sep 2018

Cited by: 11 articles | PMID: 30124194 | PMCID: PMC6106427

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Update: Ongoing Zika Virus Transmission - Puerto Rico, November 1, 2015-April 14, 2016.

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 65(17):451-455, 06 May 2016

Cited by: 28 articles | PMID: 27149205

Update: Ongoing Zika Virus Transmission - Puerto Rico, November 1, 2015-July 7, 2016.

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 65(30):774-779, 05 Aug 2016

Cited by: 45 articles | PMID: 27490087

Preparedness of public health-care system for Zika virus outbreak: An Indian perspective.

J Infect Public Health, 13(7):949-955, 25 Apr 2020

Cited by: 6 articles | PMID: 32340832

Review

1

1