Abstract

Free full text

Critical effects of long non-coding RNA on fibrosis diseases

Abstract

The expression or dysfunction of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) is closely related to various hereditary diseases, autoimmune diseases, metabolic diseases and tumors. LncRNAs were also recently recognized as functional regulators of fibrosis, which is a secondary process in many of these diseases and a primary pathology in fibrosis diseases. We review the latest findings on lncRNAs in fibrosis diseases of the liver, myocardium, kidney, lung and peritoneum. We also discuss the potential of disease-related lncRNAs as therapeutic targets for the clinical treatment of human fibrosis diseases.

Introduction

Fibrosis is the formation of excess fibrous connective tissue in an organ or tissue.1 This process may be reactive or reparative and benign or pathological. The effect of fibrosis when it occurs in response to injury is known as scarring, and the fibrotic mass is known as a fibroma when the fibrosis originates from a single cell. The physiological outcome of deposited connective tissue, particularly when excessive, may be an obliteration of the architecture and function of the underlying organ or tissue, which is a pathological state. The pathological accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins in fibrosis ultimately causes scarring and a thickening of the affected tissue, which involves stimulated fibroblasts laying down connective tissue, including collagen and glycosaminoglycans.2

The process of fibrosis is initiated when immune cells, such as macrophages, release soluble factors that stimulate fibroblasts. The most well-characterized pro-fibrotic mediator is tumor growth factor-beta (TGF-β), which is released by macrophages and any damaged tissue between interstitial surfaces. Other soluble mediators of fibrosis include connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and interleukin 4 (IL-4). These factors initiate signal transduction pathways, such as the AKT/mTOR3 and SMAD,4 which lead to the proliferation and activation of fibroblasts for the deposition of ECM into the surrounding connective tissue. This process of tissue repair is complex and requires tight regulation of ECM synthesis and degradation to ensure the maintenance of normal tissue architecture (and function). The entire process is necessary, but it may lead to a progressive irreversible fibrotic response if the tissue injury is severe or repetitive or the wound healing response itself becomes deregulated.2

Recent studies demonstrated that epigenetic mechanisms are also involved in the regulation of the fibrosis process.5, 6, 7 Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are RNA segments >200 nucleotides in length that lack protein-coding capacity.8, 9, 10 Some lncRNAs are regulators of fibrosis.11, 12, 13 LncRNAs mediate various normal biological processes and exhibit dose compensation effects in the epigenetic regulation of the cell cycle and cells.14, 15 The dysregulation of lncRNAs may produce serious detrimental effects on human health. These molecules are associated with the pathogenesis of various human diseases, such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders.16, 17, 18 LncRNAs are unlike microRNAs (miRNAs), which are RNA segments ~22

nucleotides in length that lack protein-coding capacity.8, 9, 10 Some lncRNAs are regulators of fibrosis.11, 12, 13 LncRNAs mediate various normal biological processes and exhibit dose compensation effects in the epigenetic regulation of the cell cycle and cells.14, 15 The dysregulation of lncRNAs may produce serious detrimental effects on human health. These molecules are associated with the pathogenesis of various human diseases, such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders.16, 17, 18 LncRNAs are unlike microRNAs (miRNAs), which are RNA segments ~22 nucleotides in length that regulate ~60% of human genes19 and function exclusively at the post-transcriptional level. LncRNAs participate in the transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of genes.

nucleotides in length that regulate ~60% of human genes19 and function exclusively at the post-transcriptional level. LncRNAs participate in the transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of genes.

The present review summarizes the latest advances in our understanding of lncRNA regulation of fibrosis and focuses on the mechanisms of fibrosis in the liver, myocardium, kidney, lung and peritoneum. We also discuss the potential of lncRNA-based therapies for these fibrosis diseases.

Liver fibrosis

A variety of inducers of chronic liver damage, including viral infection, chemical exposure, physical injury and autoimmune hepatitis, may cause liver fibrosis. The condition itself is characterized by an excessive accumulation of ECM and liver dysfunction. Sustained liver fibrosis is key to the development of a broad range of chronic liver diseases, from cirrhosis to cancer.18 The lncRNAs involved in liver fibrosis are discussed below.

Alu-mediated p21 transcriptional regulator and long intergenic non-coding RNA-p21 regulate the p21-mediated progression of liver fibrosis

Animal cells synthesize and secrete ECM, which is distributed along the cell surface or between cells. An array of primary and/or secondary causes of ECM synthesis and an imbalance between ECM synthesis and degradation may induce fibrosis. Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) are the predominant producers of ECM during liver fibrogenesis.20, 21 Current studies suggest that the activation of HSCs, such as by liver injury, and the subsequent secretion of ECM are key mechanisms in the initiation and progression of liver fibrosis.22, 23, 24 However, this process reverts to the original (non-fibrotic) state after removal of the liver damage stimulus.25, 26

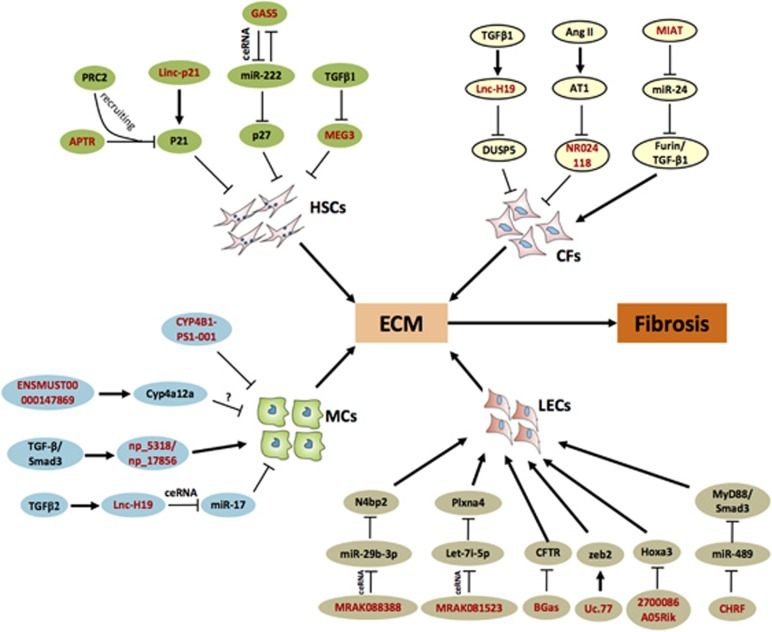

Collagen is the main constituent of a fibrotic scar, and TGF-β promotes its expression in HSC myofibroblasts.27, 28, 29 Negishi et al.30 recently performed a small-interfering (si)RNA screen of human lncRNAs to identify the molecules that contribute to cell proliferation. Alu-mediated p21 transcriptional regulator (APTR) was identified as an lncRNA target, and it acted in trans to repress the promoter of the CDKN1A/p21 tumor suppressor gene and promote cell proliferation independently of p53. A detailed molecular analysis revealed that APTR recruited polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) to repress the activity of the p21 promoter and inhibit p21 expression30 (Figure 1). Another study demonstrated increased APTR levels in serum and liver biopsy samples and activated HSCs from patients with liver cirrhosis.31 Knockdown of APTR inhibited HSC activation, mitigated the accumulation of collagen, and abrogated the TGF-β1-induced upregulation of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) in HSCs. However, treatment with p21 siRNA attenuated the inhibition of cell cycling and cell proliferation that occurred in primary HSCs following APTR knockdown.31

Schematic diagram of the effects and underlying mechanisms of lncRNAs in various fibroses. Green: LncRNAs involved in liver fibrosis. APTR promotes HSC activation via recruitment of the PRC2 complex to and subsequent inhibition of the p21 promoter. The inhibited expression of the tumor repressor gene p21 promotes ECM synthesis and liver fibrosis. LincRNA-p21 also promotes liver fibrosis via a direct decrease in p21 expression. MEG3 inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis, but TGF-β1 decreases MEG3 expression via mediation of the methylation of the MEG3 promoter, which induces liver fibrosis. MiRNA-222 is involved in liver fibrosis via targeting of the GAS5 gene. However, GAS5 is a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) that directly binds to miR-222 and increases the level of the tumor suppressor p27, which inhibits HSC activation and proliferation. GAS5 is downregulated in activated HSCs and fibrotic liver tissues. Yellow: LncRNAs involved in cardiac fibrosis. TGF-β1-induced upregulation of lncRNA H19 correlates with a gradual decrease in DUSP5 expression, which represses the DUSP5/ERK1/2 signaling pathway in primary rat cardiac fibroblasts. Ang II treatment decreases the levels of lncRNA-NR024118 and Cdkn1c in cardiac fibroblasts via its cognate receptor, Ang II receptor type I (AT1). MIAT functions as a ceRNA for miR-24 and upregulates TGF-β1 expression to induce the subsequent activation of CFs. Blue: LncRNAs involved in kidney fibrosis. H19 is upregulated in TGF-β2-induced HK-2 cell fibrosis via sponging of miR-17 (artificial miRNA decoy), and np_5318/np_17856 level is upregulated in TGF-β-induced cells, which promotes the fibrotic process. CYP4B1-PS1-001/ ENSMUST0000 0147869 is downregulated in kidney tissues from db/db mice and promotes the proliferation of MCs. Brown: LncRNAs involved in lung fibrosis. MRAK088388 may be regulated in lung myofibroblast growth and collagen deposition via sponging of miR-29, which binds to N4bp2. MRAK081523 may compete with the let-7i pool to regulate the expression of Plxna4. MiR-489 may function as an anti-fibrotic miRNA via targeting MyD88 and Smad3, and the lncRNA CHRF inhibits miR-489 expression. Upregulated uc.77 and 27000086A05Rik target Zeb2 and Hoxa3, respectively. Downexpression of BGas induces CFTR overexpression and results in LEC proliferation and ECM production. ‘T’ (blunt) ends of connectors represent negative regulation, and pointed (arrowhead) ends represent positive regulation. Red-colored bold font indicates lncRNAs. CFs, cardiac fibroblasts; ECM, extracellular matrix; HSCs, hepatic stellate cells; LECs, lung epithelial cells; MCs, mesangial cells.

Other reports indicated that long intergenic non-coding RNA (lincRNA)-p21 inhibited liver fibrosis via promotion of p21 expression.32 Studies demonstrated that lincRNA-p21 induced apoptosis in mouse cell models,31, 33 and its expression is decreased in tumors.34 Zheng et al.32 recently reported that the targeting the tumor suppressor gene p21 markedly reduced lincRNA-p21 expression in mouse liver fibrosis models and human cirrhotic liver (Figure 1). Liver cirrhosis patients, especially patients with decompensated cirrhosis, exhibited significantly lower serum lincRNA-p21 levels compared to healthy subjects. Overexpression of lincRNA-p21 in vitro upregulated p21 mRNA and protein levels, inhibited cell cycle progression and the proliferation of primary HSCs and reversed the activation of HSCs to their quiescent phenotype. Lentivirus-mediated lincRNA-p21 transfer into these mice decreased the severity of liver fibrosis.32 These studies collectively revealed a new biological role of APTR and lincRNA-p21 in liver fibrogenesis and suggest the potential of these molecules as biomarkers or therapeutic targets to clinically address liver fibrosis via the targeting of a common tumor suppressor gene, p2131, 32 (Figure 1; Table 1).

Table 1

| Organ | LncRNA | Effect on fibrosis | Mechanism | Levels in research models | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | LincRNA-p21 | ↓ | Promoting p21 expression | ↓ in mouse liver fibrosis models and human cirrhotic liver | 32 |

| APTR | ↑ | Recruiting PRC2 to the p21 promoter, inhibiting p21 expression | ↑ in serum and liver biopsy samples, and activated HSCs in patients with liver cirrhosis | 30, 31 | |

| MEG3 | ↓ | ND | ↓ in TGF-β1-treated LX-2 cells, CCl4-induced mouse liver fibrosis models and human fibrotic livers | 13 | |

| GAS5 | ↓ | Functioning as a ceRNA for miR-222, increasing p27 level | ↓ in mouse, rat and human fibrotic liver samples and activated HSCs | 44, 45 | |

| Heart | H19 | ↑ | Repressing DUSP5/ERK1/2, increasing p-ERK1/2 | ↑ in TGF-β1 treated rat cardiac fibroblasts | 10 |

| NR024118 | ↓ | ND | ↓ in Ang II treated cardiac fibroblasts | 70 | |

| MIAT | ↑ | Functioning as a ceRNA for miR-24, upregulating TGF-β1 expression | ↑ in mouse myocardial infarction model, and cardiac fibroblasts treated with serum or Ang II | 72 | |

| Kidney | CYP4B1-PS1-001 | ↓ | ND | ↓ in kidney tissue from db/db mice, and MMCs cultured in high glucose | 76 |

| ENSMUST00000147869 | ↓ | Unclear, but can recruit cyp4a12a | ↓ in kidney tissue from db/db mice, and MMCs cultured in high glucose | 77 | |

| np_5318/np_17856 | ↑ | Unclear, but is TGF/Smad3-dependent | ↑ in Smad3 knockout UUO mouse model and anti-GBM GN mouse model | 81 | |

| LncRNA-H19 | ↑ | Functioning as a ceRNA for miR-17 that targets fibronectin | ↑ in TGF-β2-induced fibrosis of HK-2 human proximal tubular epithelial cells and UUO-induced renal fibrosis in vivo | 88 | |

| Lung | MRAK088388, MRAK081523 | ↑ | Functioning as ceRNAs for miR-29b-3p and let-7i-5p, respectively, up-regulating N4bp2 and Plxna4 that are the targets of miR-29b-3p and let-7i-5p, respectively | ↑ in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis rat model | 93 |

| lncRNA CHRF | ↑ | Possible functioning as a ceRNA to suppress miR-489 that targets MyD88 and Smad3 | ↑ in lung tissues of a mouse model of silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis and macrophages exposed to silica and fibroblasts exposed to TGF-β1 | 96 | |

| BGas | ↓ | Functioning as a modulator of CFTR expression by tethering various structural and chromatin architectural modifying proteins to intron 11 of CFTR | ↑ in CFPAC cells and human airway epithelial 1HAEo- cells | 9 | |

| uc.77, 2700086A05Rik | ↑ | Promoting Zeb2 and decreasing Hoxa3 expression, respectively | ↑ in mouse model of interstitial fibrosis | 98 |

Abbreviations: Anti-GBM GN, immunologically induced anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis; ↓, Inhibition or decrease; MMCs, mouse mesangial cells; ND, not detected in the referred literature; ↑, Promotion or increase; UUO, Smad3 knockout mouse models of unilateral ureteral obstructive nephropathy.

Inhibitory effects of lncRNA MEG3 in liver fibrosis

Maternally expressed gene 3 (MEG3) is an imprinted gene located at 14q32 that encodes an lncRNA correlated with several human cancers.35 MEG3 does not encode any protein, and it functions at the RNA level.36, 37 A methylation-dependent downregulation of MEG3 was described in liver cancers.35 Braconi et al.38 reported that the forced expression of MEG3 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells significantly decreased anchorage-dependent and anchorage-independent cell growth and induced apoptosis. He et al.13 recently investigated the role of MEG3 in the development of liver fibrosis and TGF-β1-induced HSC activation. These authors demonstrated that MEG3 levels were remarkably decreased in carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced mouse liver fibrosis models and human fibrotic livers. MEG3 expression was downregulated in the human HSC line LX-2 in response to TGF-β1 stimulation, and this effect was dose- and time-dependent. This downregulation of MEG3 expression was likely mediated by hypermethylation of the MEG3 promoter, which was identified using methylation-specific PCR. Inhibition of methylation by treatment with 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine or siRNA targeted to DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) robustly increased MEG3 expression in TGF-β1-induced LX-2 cells, which activated p53, mediated cytochrome c release, and induced caspase-3-dependent apoptosis13 (Figure 1; Table 1).

Growth arrest-specific transcript 5 inhibits liver fibrogenesis

Growth arrest-specific transcript 5 (GAS5) is a crucial mediator of cell proliferation and growth in various cancer cells, including breast, gastric and prostate, and T cells.39, 40, 41, 42, 43 Yu et al.44 reported that GAS5 was a target of miR-222 and demonstrated that miR-222 inhibited GAS5 expression. MiR-222 is involved in liver fibrosis, and MiR-222 expression increases with the progression of liver fibrosis severity.45 The underlying mechanisms likely include the direct inhibition of miR-222 on tumor suppressor p27 gene expression,46 which was demonstrated in liver fibrosis and glioblastomas models.45, 47

Notably, Yu et al.44 also found that GAS5 increased p27 protein levels by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) for miR-222, which inhibited the activation and proliferation of HSCs. GAS5 overexpression further suppressed the activation of primary HSCs in vitro and alleviated the accumulation of collagen in fibrotic liver tissues in vivo. However, Yu et al. reported reduced GAS5 expression in mouse, rat and human fibrotic liver samples and activated HSCs, which supports the hypothesis of the pivotal inhibitory roles of GAS5 in liver fibrosis and reveals a new regulatory circuitry in liver fibrosis in which RNAs cross talk by competing for shared miRNAs44 (Figure 1; Table 1). These insights represent a potential new therapeutic strategy for the treatment of liver fibrosis.

Myocardial fibrosis

Cardiac fibrosis is a major factor in the progression of myocardial infarction and heart failure,48, 49, 50 which is characterized by an excessive deposition of ECM proteins that impair organ function.51, 52, 53 Cardiac fibroblasts (CFs) are primarily responsible for the homeostatic maintenance of tissue ECM, particularly healing after injury.54, 55, 56, 57 Activated fibroblasts exhibit increased protein synthesis, including collagens, other ECM proteins, certain cytokines and α-SMA (a contractile protein and marker of profibrogenic CF activation).58, 59 Numerous regulatory factors also exert substantial effects on fibrosis and may be responsible for the inter-organ variability of fibrotic manifestations.53, 60, 61 However, there is no therapy for this disease because of our limited understanding of the basic underlying mechanisms of cardiac fibrosis. Recent investigations demonstrated that the expression of distinct ncRNAs, including lncRNAs, strongly correlated with the genesis, progression and treatment of cardiac fibrosis.62

LncRNA H19 control of the dual-specificity phosphatase 5/ERK1/2 axis contributes to cardiac fibrosis

LncRNA H19 is a 3-kb ncRNA that is expressed in the nucleus and cytoplasm. H19 is activated in embryonic cells, and it is highly expressed during embryogenesis. H19 expression is significantly reduced after birth, but it may significantly increase in disease conditions.63 The primary function of H19 is the upregulation of cell activation.64 The downregulation of dual-specificity phosphatase 5 (DUSP5) increased cell proliferation,65 and this effect was mediated via epigenetic events involving lncRNA H19 in a human choriocarcinoma cell line.66 Tao et al.10 recently demonstrated the ability of H19 to negatively regulate DUSP5 gene expression in cardiac fibroblast and fibrosis tissues. These authors also demonstrated an upregulation of H19 expression in response to TGF-β1 treatment in freshly isolated rat cardiac fibroblasts, which correlated with the gradual decrease in DUSP5 expression. Decreased DUSP5 expression was the consequence of at least a partial repression of DUSP5/ERK1/2. H19 ectopic overexpression reduced DUSP5 abundance and increased the proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts, and H19 silencing induced opposite effects. Therefore, the collective literature suggests a broader perspective for H19 beyond its roles in tumor cells, with functional contributions to cardiac fibroblast proliferation and fibrosis (Figure 1; Table 1).

LncRNA-NR024118 and Cdkn1c in adult rat cardiac fibroblasts

Angiotensin II (Ang II) increases blood pressure via stimulation of the Gq protein in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), which activates an IP3-dependent mechanism to increase intracellular calcium levels, induce blood vessel contraction, and increase blood volume and pressure.67 Ang II also plays numerous roles in cardiac fibroblasts, including the stimulation of cardiac fibroblasts proliferation and ECM synthesis and the promotion of cytokine secretion, which eventually leads to cardiac fibrosis.68, 69

Recent research indicates that Ang II regulates specific lncRNAs in the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis. Jiang et al.70 analyzed the expression profile of lncRNAs in Ang II-treated cardiac fibroblasts using lncRNAs arrays to investigate the role of lncRNAs in cardiac fibrosis. These authors found that 282 of the 4376 detected lncRNAs exhibited a >2-fold differential expression in response to 24-h Ang II (100 nm) treatment. Twenty-two of the lncRNAs exhibited a greater than four-fold change. Ang II also induced broad expression changes in protein-coding genes in cardiac fibroblasts. Quantitative real-time PCR confirmed the changes of six lncRNAs (AF159100, BC086588, MRNR026574, MRAK134679, NR024118 and AX765700) and nine mRNAs (IL6, RGS2, PRG4, TIMP1, Cdkn1c, TIMP3, Col I, Col III and fibronectin) in cardiac fibroblasts. The Ang II-induced decrease in lncRNA-NR024118 and Cdkn1c was mediated by an Ang II receptor type I (AT1)-dependent pathway and not an AT2 receptor-dependent pathway, as demonstrated using AT1 and AT2 blockers, respectively70 (Figure 1; Table 1). These results provide a foundational understanding of the molecular mechanisms of Ang II receptors in adult rat cardiac fibroblasts.

nm) treatment. Twenty-two of the lncRNAs exhibited a greater than four-fold change. Ang II also induced broad expression changes in protein-coding genes in cardiac fibroblasts. Quantitative real-time PCR confirmed the changes of six lncRNAs (AF159100, BC086588, MRNR026574, MRAK134679, NR024118 and AX765700) and nine mRNAs (IL6, RGS2, PRG4, TIMP1, Cdkn1c, TIMP3, Col I, Col III and fibronectin) in cardiac fibroblasts. The Ang II-induced decrease in lncRNA-NR024118 and Cdkn1c was mediated by an Ang II receptor type I (AT1)-dependent pathway and not an AT2 receptor-dependent pathway, as demonstrated using AT1 and AT2 blockers, respectively70 (Figure 1; Table 1). These results provide a foundational understanding of the molecular mechanisms of Ang II receptors in adult rat cardiac fibroblasts.

Myocardial infarction-associated transcript is a pro-fibrotic lncRNA in cardiac fibrosis in post-infarct myocardium

Myocardial infarction-associated transcript (MIAT) confers a risk of myocardial infarction (MI).71 Qu et al.72 recently elucidated the pathophysiological role and the underlying mechanisms of MIAT in the regulation of cardiac fibrosis. MIAT was remarkably upregulated in a mouse model of MI and cardiac fibroblasts treated with serum or Ang II, and this upregulation was accompanied by cardiac interstitial fibrosis. MIAT upregulation in MI was accompanied by a deregulation of some fibrosis-related regulators, namely, miR-24 (downregulated) and furin and TGF-β1 (upregulated). However, siRNA-mediated knockdown of endogenous MIAT reduced the cardiac fibrosis and restored the deregulated expression of the fibrosis-related regulators. These changes in the expression of regulators promoted fibroblast proliferation and collagen accumulation, and the siRNA-mediated knockdown of MIAT or overexpression of miR-24 via delivery of its mimic abrogated the fibrogenesis.

Qu et al.72 also confirmed that MIAT absorbed miR-24 via its sponge-like action as a ceRNA. MiR-24 is a regulator of TGF-β1 activation,73 and the mechanism of miR-24 promotion of heart fibrosis may form a new fibrosis-regulatory modality in which the increased expression of MIAT will cause downregulation of miR-24 and ultimately induce cardiac fibrosis (Figure 1; Table 1). The Qu et al.72 study identified MIAT as the first profibrotic lncRNA in the heart and characterized the role of MIAT in the pathogenesis of MI. This mechanism may contribute to other cardiac pathological processes associated with fibrosis. These collective findings suggest the normalization of MIAT levels as a therapeutic option for the treatment of MI-induced cardiac fibrosis and the associated cardiac dysfunction.

Renal fibrosis

LncRNA protects mesangial cells from proliferation and fibrosis

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is an important microvascular complication of diabetes. The incidence of end-stage renal disease as a result of DN continues to increase annually.74, 75 DN is characterized by a series of abnormal characteristics, including glomerular hypertrophy, thickening of the glomerular basement membrane, mesangial expansion and the accumulation of ECM. Wang et al.76, 77 recently investigated the effects of lncRNAs on DN pathogenesis using lncRNA microarrays to detect altered expression in three cases of kidney tissue from db/db mice, which is a genetic model of early stage type 2 DN. A total of 1018 lncRNAs exhibited differential expression (>2 fold-change); 221 lncRNAs were upregulated, and 797 lncRNAs were downregulated compared to control (db/m) mice. CYP4B1-PS1-001 was significantly downregulated in early DN in the in vitro and in vivo model systems, and CYP4B1-PS1-001 overexpression inhibited mesangial cell (MC) proliferation and fibrosis.76

ENSMUST00000147869 and Cyp4a12a expression decreased in a dose-dependent manner in mouse MCs (MMCs) under different glucose conditions.77 Overexpression of ENSMUST00000147869 in MMCs impeded proliferation and fibrosis and reversed the proliferation rate of MMCs under high-glucose conditions. Cyp4a12a is a neighboring gene locus to ENSMUST00000147869, and it is a target gene for this lncRNA, which results in downregulation and recruitment during ENSMUST00000147869 overexpression. However, whether Cyp4a12a participates in proliferation and fibrosis of MMCs is not known. These preliminary data suggest potential roles for CYP4B1-PS1-001 and ENSMUST00000147869 in the proliferation and fibrosis of MCs, particularly MMCs. These two processes are prominent features during the early stage of DN (Figure 1; Table 1). These findings extend the relationship between lncRNAs and DN and suggest possible therapeutic targets and molecular biomarkers for this disease.

LncRNAs associate with TGF-β/Smad3-mediated renal fibrosis

TGF-β/Smad signaling plays a critical role in renal fibrosis and inflammation in chronic kidney diseases, and Smad3 is a key mediator of downstream TGF-β/Smad signaling, which mediates renal inflammation and fibrosis via several miRNAs.78, 79, 80 Zhou et al.81 recently identified the Smad3-dependent lncRNAs related to renal inflammation and fibrosis in Smad3 knockout mouse models of unilateral ureteral obstructive (UUO) nephropathy and immunologically induced anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis (anti-GBM GN). A total of 151 lncRNAs in UUO kidney and 413 lncRNAs in anti-GBM GN kidneys were significantly altered in the Smad3 knockout mice compared to wild-type mice. Twenty-one novel lncRNAs were co-expressed in both disease models. Twenty-one lncRNAs were upregulated in wild type but downregulated in Smad3 knockout mice. The kidneys in both disease models exhibited progressive renal inflammation and fibrosis and beneficial effects following Smad3 gene deletion or suppression. The pool of lncRNAs that are differentially expressed in the UUO kidney may be related to fibrogenesis because progressive renal fibrosis in the UUO kidney is Smad3-dependent.80, 82, 83 Real-time PCR confirmed these findings and revealed a functional link between the Smad3-dependent lncRNA np_5318/np_17856 and progressive kidney injury (Figure 1; Table 1). This study suggested that the identification and characterization of functional lncRNAs associated with kidney disease represent a promising research direction for renal disorders and may lead to the development of new lncRNA-based therapies.

LncRNA-H19 promotes renal fibrosis

Renal fibrosis is the final outcome of many renal diseases.84 Aberrant lncRNA expression is involved in renal development, renal cell carcinoma and renal inflammation.81, 85, 86 For example, H19 plays an important role in renal development.86, 87 Xie et al.88 recently demonstrated a significant upregulation of H19 expression in vivo, TGF-β2-induced fibrosis of HK-2 human proximal tubular epithelial cells and UUO-induced renal fibrosis. Knockdown of H19 significantly attenuated renal fibrosis in vitro and in vivo. A previous study had suggested that miR-17 retarded tissue growth and inhibited fibronectin expression.89 Xie et al. found that the increased H19 levels alleviated the miR-17 repressive effect and increased the expression of fibronectin, which is a target gene of miR-17. These results suggest that H19 functions as a ceRNA targeting miR-17.88 These authors also confirmed the upregulated H19 expression and downregulated miR-17 expression in early and advanced animal models of renal fibrosis.88 Therefore, lncRNA-H19, miR-17 and fibronectin form a ceRNA regulatory network that is involved in renal fibrosis, which indicates that H19 upregulation contributes to renal fibrosis, and H19 inhibition may represent a novel anti-fibrotic treatment in renal diseases (Figure 1; Table 1).

Pulmonary fibrosis

Pulmonary fibrosis is an age-related lung disease that was once regarded as simply a chronic inflammatory process with few treatment options. However, environmental triggers (behavioral and occupational) were identified, including cigarette smoke, various dust particles and hazardous chemicals.90, 91 Dysregulation of lncRNAs may play crucial roles in the presence of chronic lung infection and/or inflammation.92 The epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) of alveolar epithelial cell transformation is likely an important pathogenic mechanism of idiopathic fibrosis. Therefore, the lncRNAs involved in the development of EMT play a crucial role in the progression of pulmonary fibrosis, and several lncRNAs are involved in pulmonary fibrosis.

LncRNAs MRAK088388 and MRAK081523 as ceRNAs in pulmonary fibrosis

Song et al.93 evaluated the functions of lncRNAs in pulmonary fibrosis by searching portions of lncRNAs that were adjacent or homologous to protein-coding genes in the UCSC genome bioinformatics database (https://genome.ucsc.edu/). The authors selected two differentially expressed lncRNAs, MRAK088388 and MRAK081523, for detailed examination of their regulatory mechanisms. Both lncRNAs were analyzed as lincRNAs and identified as orthologues of mouse lncRNAs AK088388 and AK081523, respectively, which are significantly upregulated in the bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis mouse model, which was evidenced using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR and in situ hybridization assays. These authors also found that MRAK088388 and N4bp2 (a Bcl-3 binding protein) shared miRNA response elements for miR-200, miR-429, miR-29 and miR-30, and MRAK081523 and Plxna4 (a tumor-promoting protein) shared miRNA response elements for miR-218, miR-141, miR-98 and let-7.93 The expression levels of N4bp2 and Plxna4 increased significantly in fibrotic rats and highly correlated with MRAK088388 and MRAK081523 expression, respectively. MiR-29b-3p and let-7i-5p were decreased in the model group and negatively correlated with MRAK088388 and MRAK081523 expression, respectively. MRAK088388 and MRAK081523 regulate N4bp2 and Plxna4 expression via sponging miR-29b-3p and let-7i-5p, respectively, and exhibited regulatory functions as ceRNAs.93 The resulting insights of this study into the functional interactions of lncRNAs, miRNAs and mRNAs may lead to new theories on the pathogenesis and treatment of pulmonary fibrosis (Figure 1; Table 1).

LncRNA CHRF promotes silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis via targeting of miR-489

Silicosis is an incurable occupational disease associated with inflammation, fibroblast proliferation and an accumulation of ECM in lung tissues.94 Ji et al.95 reported decreased expression levels of miR-489 in lung tissues of silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis detected using miRNA microassay screening. Wu et al.96 examined the role of miR-489 in a mouse model of silicosis and found reduced miR-489 levels in silica-exposed macrophages and TGF-β1-exposed fibroblasts. The results of in vivo miR-489 overexpression were consistent with its anti-fibrotic role of attenuating inflammation and fibrotic progression. The underlying molecular mechanisms include miR-489 inhibition of silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis, which occurs primarily via repression of its target genes MyD88 and Smad3. However, upregulation of the lncRNA cardiac hypertrophy-related factor (CHRF) in the mouse model reversed the inhibitory effect of miR-489 on MyD88 and Smad3 to trigger the inflammation and fibrotic signaling pathways96 (Figure 1; Table 1). Therefore, the CHRF-miR-489-MyD88 Smad3 signaling axis appears to exert key functions in silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis and may represent a novel therapeutic target for silicosis.

LncRNA BGas regulates cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis is a lethal multisystem, autosomal recessive disorder, but the detailed mechanisms of this disease are not known. McKiernan et al.92 defined the expression profile of 30 586 lncRNAs using a microarray assessment of bronchial cells isolated from endobronchial brushings of cystic fibrosis and non-cystic fibrosis individuals. A total of 1063 lncRNAs exhibited differential expression, and gene ontology bioinformatics analysis highlighted that the numerous over-represented processes in the cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelium were related to inflammation. TLR8 natural antisense lncRNA (the 1349-bp TLR8-AS1 transcript) was downregulated in cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelium and exhibited low-level expression in three of the nine non-cystic fibrosis controls and only one of seven cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial samples (absent in all other samples). However, this study did not further examine how TLR8-AS1 contributed to the molecular pathogenic processes of cystic fibrosis.

586 lncRNAs using a microarray assessment of bronchial cells isolated from endobronchial brushings of cystic fibrosis and non-cystic fibrosis individuals. A total of 1063 lncRNAs exhibited differential expression, and gene ontology bioinformatics analysis highlighted that the numerous over-represented processes in the cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelium were related to inflammation. TLR8 natural antisense lncRNA (the 1349-bp TLR8-AS1 transcript) was downregulated in cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelium and exhibited low-level expression in three of the nine non-cystic fibrosis controls and only one of seven cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial samples (absent in all other samples). However, this study did not further examine how TLR8-AS1 contributed to the molecular pathogenic processes of cystic fibrosis.

The root cause of cystic fibrosis is heritable recessive mutations that affect the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene and the subsequent expression and activity of encoded ion channels at the cell surface.97 Saayman et al.9 confirmed that lncRNA BGas contributed to cystic fibrosis pathogenesis via regulation of CFTR gene expression. These authors demonstrated that CFTR was regulated transcriptionally by the actions of lncRNA BGas, which emanates from intron 11 of the CFTR gene and is expressed in the antisense orientation relative to the protein-coding sense strand.9 BGas functions in concert with several proteins, including HMGA1, HMGB1 and WIBG, to modulate the local chromatin and DNA architecture of intron 11 of the CFTR gene, which affects transcription. Suppression of BGas or its associated proteins results in a gain of CFTR expression and chloride ion function9 (Figure 1; Table 1). These observations highlighted the possible effects of certain lncRNAs on cystic fibrosis pathogenesis, such as the involvement of TLR8-AS1 in the chronic infection and inflammation that exist in the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis and the involvement of BGas in the normal function of ion channels. The collective data also suggest that these lncRNAs represent novel therapeutic targets for cystic fibrosis.

LncRNA uc.77 and 2700086A05Rik regulate EMT in pulmonary fibrosis

Sun et al.98 established a mouse model of pulmonary injury and progressive interstitial fibrosis using an intraperitoneal injection of paraquat, which is a widely used herbicide that causes pulmonary fibrosis in humans. These authors used transcriptome sequencing and microarray analysis to identify 513 upregulated and 204 downregulated lncRNAs in paraquat-induced fibrotic lung tissues. The evolutionally conserved target genes of two upregulated lncRNAs, uc.77 and 2700086A05Rik, as Zeb2 and Hoxa3, respectively, were identified, and both of these factors are important modulators of EMT. Overexpression of uc.77 in cells increased Zeb2 expression, and overexpression of 2700086A05RiK suppressed Hoxa3 in human lung epithelial cells. Zeb2 is an EMT-activating transcription factor, and Hoxa3 modulates tissue remodeling via coordinated changes in epithelial and endothelial cell gene expression and behavior during wound repair.99, 100 The overexpression of uc.77 or 2700086A05Rik in human lung epithelial cells consistently induced EMT, which was demonstrated as changes in gene and protein expression of various EMT markers and cell morphology.98 Collectively, these results revealed a crucial role for lncRNAs in the regulation of EMT during lung fibrosis and provide potential avenues for the discovery of novel molecular markers and therapeutic targets for interstitial pulmonary fibrosis (Figure 1; Table 1).

Peritoneal fibrosis

Liu et al.101 examined lncRNA, mRNA and miRNA expression profiles and their potential roles in the process of peritoneal fibrosis using normal control peritoneum and fibrotic peritoneum from a mouse model (peritoneal dialysis fluid induction). A total of 232 lncRNAs (127 upregulated and 105 downregulated), 154 mRNAs (87 upregulated and 67 downregulated) and 15 miRNAs (14 upregulated and 1 downregulated) were differentially expressed in the fibrotic peritoneum compared to the normal controls. Nine of the differentially expressed lncRNAs and five miRNAs were validated using real-time reverse-transcription PCR. Pathway analysis demonstrated that the Jak-STAT, TGF-β and MAPK signaling pathways were closely related to peritoneal fibrosis. Gene co-expression network analysis identified many genes, including JunB, HSP72 and Nedd9; lncRNAs, including AK089579, AK080622 and ENSMUST00000053838; and miRNAs, including miR-182 and miR-488. All of these species potentially play key roles in peritoneal fibrosis (Figure 1; Table 1). These results provide a foundation and an expansive view of the roles and mechanisms of ncRNAs in peritoneal dialysis fluid-induced peritoneal fibrosis, but the exact roles and the detailed mechanisms require further investigation to fully understand the contribution of ncRNAs, including lncRNAs, to peritoneal fibrosis.

Conclusion

This review summarized the mechanisms of fibrosis influenced by lncRNAs. The exact role and underlying mechanisms of most of the identified lncRNAs are not known, but the knowledge to date is key to understanding fibrosis diseases in its various forms. Thereafter, we could target and influence lncRNA changes using pharmacological or genetic interventions to treat the spectrum of pathogenic fibroses. Development of inhibitors for the treatment of fibrosis is promising, and systematic study of the clinical application of these inhibitors will lead to further insights into the overall disease processes and allow more effective and specific treatment strategies. LncRNA inhibitors will likely be effective, but the problem of targeting lncRNA effectively must be solved before this benefit may be realized. Combination therapies of lncRNA inhibitors and other chemotherapeutic drugs may also be useful. LncRNAs represent a heterogeneous class of transcripts that are incompletely annotated, and challenges in the investigation of these lncRNAs remain. Continued investigations that build on the existing knowledge presented herein will certainly overcome these challenges and significantly impact the field of human fibrosis diseases.

TGF-β also exhibits a wide potential influence on cell growth, differentiation, ECM aggregation and the immune response, and it is one of the most widespread and profound cytokines for various organ fibrosis in the body.102 TGF-β regulates the proliferation, migration and adhesion of cancer cells, and it creates a favorable environment for tumor development.103, 104 Hepatic fibrosis is characterized by the excessive deposition of ECM, and it is caused by chronic liver injury from various sources. Hepatic fibrosis is a necessary stage for the development of chronic liver disease to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, which suggests a link between fibrosis and carcinogenesis. Recent studies revealed that the pro-fibrosis roles of MEG3, MIAT, lnc-H19 and np_5318/np_17856 were related to TGF-β, which suggests that these lncRNAs also contribute to the related carcinogenesis. Therefore, the targeting of these lncRNAs would be beneficial to fibrosis and potentially helpful in the prevention of tumorigenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (no. 2013CB531503), the National Foundation of China (no. 81502728), the Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (no. 1408085MH149) and the Research Program of Foundation Science and Application Technology of Chongqing (nos. cstc2015jcyjA10105 and cstc2015jcyjA10119). The funders had no role in the study design, data analysis, or decision to publish.

References

- Birbrair A, Zhang T, Files DC, Mannava S, Smith T, Wang ZM et al. Type-1 pericytes accumulate after tissue injury and produce collagen in an organ-dependent manner. Stem Cell Res Ther 2014; 5: 122. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Neary R, Watson CJ, Baugh JA. Epigenetics and the overhealing wound: the role of DNA methylation in fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 2015; 8: 18. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra A, Luna JI, Marusina AI, Merleev A, Kundu-Raychaudhuri S, Fiorentino D et al. Dual mTOR inhibition is required to prevent TGF-beta-mediated fibrosis: implications for scleroderma. J Invest Dermatol 2015; 135: 2873–2876. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A, Abraham DJ. TGF-beta signaling and the fibrotic response. FASEB J 2004; 18: 816–827. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Kim Y, Friso S, Choi SW. Epigenetics in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Mol Aspects Med 2017; 54: 78–88. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi V, De Pascale MR, Zullo A, Soricelli A, Infante T, Mancini FP et al. Evidence of epigenetic tags in cardiac fibrosis. J Cardiol 2017; 69: 401–408. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly S. Epigenetics in fibrosis. Mol Aspects Med 2017; 54: 89–102. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Perry MM, Muntoni F. Noncoding RNAs and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Epigenomics 2016; 8: 1527–1537. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Saayman SM, Ackley A, Burdach J, Clemson M, Gruenert DC, Tachikawa K et al. Long non-coding RNA BGas regulates the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Mol Ther 2016; 24: 1351–1357. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tao H, Cao W, Yang JJ, Shi KH, Zhou X, Liu LP et al. Long noncoding RNA H19 controls DUSP5/ERK1/2 axis in cardiac fibroblast proliferation and fibrosis. Cardiovasc Pathol 2016; 25: 381–389. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Froberg JE, Lee JT. Long noncoding RNAs: fresh perspectives into the RNA world. Trends Biochem Sci 2014; 39: 35–43. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Batista PJ, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs: cellular address codes in development and disease. Cell 2013; 152: 1298–1307. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Wu YT, Huang C, Meng XM, Ma TT, Wu BM et al. Inhibitory effects of long noncoding RNA MEG3 on hepatic stellate cells activation and liver fibrogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014; 1842: 2204–2215. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano T, Fraser P. No-nonsense functions for long noncoding RNAs. Cell 2011; 145: 178–181. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JT. Epigenetic regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Science 2012; 338: 1435–1439. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wapinski O, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs and human disease. Trends Cell Biol 2011; 21: 354–361. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kapranov P, Cheng J, Dike S, Nix DA, Duttagupta R, Willingham AT et al. RNA maps reveal new RNA classes and a possible function for pervasive transcription. Science 2007; 316: 1484–1488. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Teng KY, Ghoshal K. Role of noncoding RNAs as biomarker and therapeutic targets for liver fibrosis. Gene Expr 2015; 16: 155–162. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- van Kouwenhove M, Kedde M, Agami R. MicroRNA regulation by RNA-binding proteins and its implications for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2011; 11: 644–656. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Page A, Paoli PP, Hill SJ, Howarth R, Wu R, Kweon SM et al. Alcohol directly stimulates epigenetic modifications in hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatol 2015; 62: 388–397. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ghazwani M, Zhang Y, Lu J, Fan J, Gandhi CR et al. miR-122 regulates collagen production via targeting hepatic stellate cells and suppressing P4HA1 expression. J Hepatol 2013; 58: 522–528. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SL, Rockey DC, McGuire RF, Maher JJ, Boyles JK, Yamasaki G. Isolated hepatic lipocytes and Kupffer cells from normal human liver: morphological and functional characteristics in primary culture. Hepatology 1992; 15: 234–243. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SL, Roll FJ, Boyles J, Bissell DM. Hepatic lipocytes: the principal collagen-producing cells of normal rat liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1985; 82: 8681–8685. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Mederacke I, Hsu CC, Troeger JS, Huebener P, Mu X, Dapito DH et al. Fate tracing reveals hepatic stellate cells as dominant contributors to liver fibrosis independent of its aetiology. Nat Commun 2013; 4: 2823. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kisseleva T, Cong M, Paik Y, Scholten D, Jiang C, Benner C et al. Myofibroblasts revert to an inactive phenotype during regression of liver fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: 9448–9453. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Troeger JS, Mederacke I, Gwak GY, Dapito DH, Mu X, Hsu CC et al. Deactivation of hepatic stellate cells during liver fibrosis resolution in mice. Gastroenterology 2012; 143: 1073–1083.e22. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ueberham E, Low R, Ueberham U, Schonig K, Bujard H, Gebhardt R. Conditional tetracycline-regulated expression of TGF-beta1 in liver of transgenic mice leads to reversible intermediary fibrosis. Hepatology 2003; 37: 1067–1078. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hellerbrand C, Stefanovic B, Giordano F, Burchardt ER, Brenner DA. The role of TGFbeta1 in initiating hepatic stellate cell activation in vivo. J Hepatol 1999; 30: 77–87. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzler S, Lohse AW, Keil A, Henninger J, Dienes HP, Schirmacher P et al. TGF-beta1 in liver fibrosis: an inducible transgenic mouse model to study liver fibrogenesis. Am J Physiol 1999; 276: G1059–G1068. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Negishi M, Wongpalee SP, Sarkar S, Park J, Lee KY, Shibata Y et al. A new lncRNA, APTR, associates with and represses the CDKN1A/p21 promoter by recruiting polycomb proteins. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e95216. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F, Zheng J, Mao Y, Dong P, Li G, Lu Z et al. Long non-coding RNA APTR promotes the activation of hepatic stellate cells and the progression of liver fibrosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015; 463: 679–685. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Dong P, Mao Y, Chen S, Wu X, Li G et al. lincRNA-p21 inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrogenesis via p21. FEBS J 2015; 282: 4810–4821. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tran UM, Rajarajacholan U, Soh J, Kim TS, Thalappilly S, Sensen CW et al. LincRNA-p21 acts as a mediator of ING1b-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Dis 2015; 6: e1668. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai H, Fesler A, Schee K, Fodstad O, Flatmark K, Ju J. Clinical significance of long intergenic noncoding RNA-p21 in colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2013; 12: 261–266. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Zhang X, Klibanski A. MEG3 noncoding RNA: a tumor suppressor. J Mol Endocrinol 2012; 48: R45–R53. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Rice K, Wang Y, Chen W, Zhong Y, Nakayama Y et al. Maternally expressed gene 3 (MEG3) noncoding ribonucleic acid: isoform structure, expression, and functions. Endocrinology 2010; 151: 939–947. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi N, Wagatsuma H, Wakana S, Shiroishi T, Nomura M, Aisaka K et al. Identification of an imprinted gene, Meg3/Gtl2 and its human homologue MEG3, first mapped on mouse distal chromosome 12 and human chromosome 14q. Genes Cells 2000; 5: 211–220. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Braconi C, Kogure T, Valeri N, Huang N, Nuovo G, Costinean S et al. microRNA-29 can regulate expression of the long non-coding RNA gene MEG3 in hepatocellular cancer. Oncogene 2011; 30: 4750–4756. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Mourtada-Maarabouni M, Pickard MR, Hedge VL, Farzaneh F, Williams GT. GAS5, a non-protein-coding RNA, controls apoptosis and is downregulated in breast cancer. Oncogene 2009; 28: 195–208. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M, Jin FY, Xia R, Kong R, Li JH, Xu TP et al. Decreased expression of long noncoding RNA GAS5 indicates a poor prognosis and promotes cell proliferation in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer 2014; 14: 319. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Yacqub-Usman K, Pickard MR, Williams GT. Reciprocal regulation of GAS5 lncRNA levels and mTOR inhibitor action in prostate cancer cells. Prostate 2015; 75: 693–705. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard MR, Mourtada-Maarabouni M, Williams GT. Long non-coding RNA GAS5 regulates apoptosis in prostate cancer cell lines. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013; 1832: 1613–1623. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Mourtada-Maarabouni M, Hedge VL, Kirkham L, Farzaneh F, Williams GT. Growth arrest in human T-cells is controlled by the non-coding RNA growth-arrest-specific transcript 5 (GAS5). J Cell Sci 2008; 121: 939–946. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F, Zheng J, Mao Y, Dong P, Lu Z, Li G et al. Long non-coding RNA growth arrest-specific transcript 5 (GAS5) inhibits liver fibrogenesis through a mechanism of competing endogenous RNA. J Biol Chem 2015; 290: 28286–28298. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T, Enomoto M, Fujii H, Sekiya Y, Yoshizato K, Ikeda K et al. MicroRNA-221/222 upregulation indicates the activation of stellate cells and the progression of liver fibrosis. Gut 2012; 61: 1600–1609. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Chu IM, Hengst L, Slingerland JM. The Cdk inhibitor p27 in human cancer: prognostic potential and relevance to anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2008; 8: 253–267. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- le Sage C, Nagel R, Egan DA, Schrier M, Mesman E, Mangiola A et al. Regulation of the p27(Kip1) tumor suppressor by miR-221 and miR-222 promotes cancer cell proliferation. EMBO J 2007; 26: 3699–3708. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CH, Han CK, Shibu MA, Pai PY, Ho TJ, Day CH et al. Lumbrokinase from earthworm extract ameliorates second-hand smoke-induced cardiac fibrosis. Environ Toxicol 2015; 30: 1216–1225. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 2005; 120: 15–20. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Mas J, Lax A, Asensio-Lopez MC, Fernandez-Del Palacio MJ, Caballero L, Garrido IP et al. Galectin-3 expression in cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2014; 172: e98–e101. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- de Haas HJ, Arbustini E, Fuster V, Kramer CM, Narula J. Molecular imaging of the cardiac extracellular matrix. Circ Res 2014; 114: 903–915. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspard GJ, MacLean J, Rioux D, Pasumarthi KB. A novel beta-adrenergic response element regulates both basal and agonist-induced expression of cyclin-dependent kinase 1 gene in cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2014; 306: C540–C550. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tao H, Shi KH, Yang JJ, Huang C, Zhan HY, Li J. Histone deacetylases in cardiac fibrosis: current perspectives for therapy. Cell Signal 2014; 26: 521–527. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Ishikawa Y, Arita M, Akishima-Fukasawa Y, Fujita K, Inomata N et al. Antifibrotic response of cardiac fibroblasts in hypertensive hearts through enhanced TIMP-1 expression by basic fibroblast growth factor. Cardiovasc Pathol 2014; 23: 92–100. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D, Aroonsakool N, Yokoyama U, Patel HH, Insel PA. Increase in cellular cyclic AMP concentrations reverses the profibrogenic phenotype of cardiac myofibroblasts: a novel therapeutic approach for cardiac fibrosis. Mol Pharmacol 2013; 84: 787–793. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Verma SK, Lal H, Golden HB, Gerilechaogetu F, Smith M, Guleria RS et al. Rac1 and RhoA differentially regulate angiotensinogen gene expression in stretched cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res 2011; 90: 88–96. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Li Y, Zhang C, A X, Wang Y, Cui W et al. S100a8/a9 released by CD11b+Gr1+ neutrophils activates cardiac fibroblasts to initiate angiotensin II-Induced cardiac inflammation and injury. Hypertension 2014; 63: 1241–1250. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Cavin S, Maric D, Diviani D. A-kinase anchoring protein-Lbc promotes pro-fibrotic signaling in cardiac fibroblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014; 1843: 335–345. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh AK, Nagpal V, Covington JW, Michaels MA, Vaughan DE. Molecular basis of cardiac endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT): differential expression of microRNAs during EndMT. Cell Signal 2012; 24: 1031–1036. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Braitsch CM, Kanisicak O, van Berlo JH, Molkentin JD, Yutzey KE. Differential expression of embryonic epicardial progenitor markers and localization of cardiac fibrosis in adult ischemic injury and hypertensive heart disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2013; 65: 108–119. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Vettori S, Gay S, Distler O. Role of microRNAs in fibrosis. Open Rheumatol J 2012; 6: 130–139. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Huang C, Lin X, Li J. MicroRNA-29 family, a crucial therapeutic target for fibrosis diseases. Biochimie 2013; 95: 1355–1359. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Matouk IJ, DeGroot N, Mezan S, Ayesh S, Abu-lail R, Hochberg A et al. The H19 non-coding RNA is essential for human tumor growth. PLoS ONE 2007; 2: e845. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Giovarelli M, Bucci G, Ramos A, Bordo D, Wilusz CJ, Chen CY et al. H19 long noncoding RNA controls the mRNA decay promoting function of KSRP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: E5023–E5028. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Moon SJ, Lim MA, Park JS, Byun JK, Kim SM, Park MK et al. Dual-specificity phosphatase 5 attenuates autoimmune arthritis in mice via reciprocal regulation of the Th17/Treg cell balance and inhibition of osteoclastogenesis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014; 66: 3083–3095. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Yu LL, Chang K, Lu LS, Zhao D, Han J, Zheng YR et al. Lentivirus-mediated RNA interference targeting the H19 gene inhibits cell proliferation and apoptosis in human choriocarcinoma cell line JAR. BMC Cell Biol 2013; 14: 26. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaide H, Ichiki T, Nishimura J, Hirano K. Cellular mechanism of vasoconstriction induced by angiotensin II: it remains to be determined. Circ Res 2003; 93: 1015–1017. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lijnen PJ, van Pelt JF, Fagard RH. Stimulation of reactive oxygen species and collagen synthesis by angiotensin II in cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Ther 2012; 30: e1–e8. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Su J, King ME, Maldonado AE, Park C, Mende U. Regulator of G protein signaling 2 is a functionally important negative regulator of angiotensin II-induced cardiac fibroblast responses. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011; 301: H147–H156. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Zhang F, Ning Q. Losartan reverses the down-expression of long noncoding RNA-NR024118 and Cdkn1c induced by angiotensin II in adult rat cardiac fibroblasts. Pathol Biol 2015; 63: 122–125. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii N, Ozaki K, Sato H, Mizuno H, Saito S, Takahashi A et al. Identification of a novel non-coding RNA, MIAT, that confers risk of myocardial infarction. J Hum Genet 2006; 51: 1087–1099. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X, Du Y, Shu Y, Gao M, Sun F, Luo S et al. MIAT is a pro-fibrotic long non-coding RNA governing cardiac fibrosis in post-infarct myocardium. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 42657. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Derrien T, Guigo R. [Long non-coding RNAs with enhancer-like function in human cells]. Med Sci (Paris) 2011; 27: 359–361. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Reutens AT, Atkins RC. Epidemiology of diabetic nephropathy. Contrib Nephrol 2011; 170: 1–7. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014; 103: 137–149. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Wang S, Yao D, Yan Q, Lu W. A novel long non-coding RNA CYP4B1-PS1-001 regulates proliferation and fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2016; 426: 136–145. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Yao D, Wang S, Yan Q, Lu W. Long non-coding RNA ENSMUST00000147869 protects mesangial cells from proliferation and fibrosis induced by diabetic nephropathy. Endocrine 2016; 54: 81–92. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Qin W, Chung AC, Huang XR, Meng XM, Hui DS, Yu CM et al. TGF-beta/Smad3 signaling promotes renal fibrosis by inhibiting miR-29. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 22: 1462–1474. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X, Chung AC, Chen HY, Meng XM, Lan HY. Smad3-mediated upregulation of miR-21 promotes renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 22: 1668–1681. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Chung AC, Huang XR, Meng X, Lan HY. miR-192 mediates TGF-beta/Smad3-driven renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 21: 1317–1325. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Chung AC, Huang XR, Dong Y, Yu X, Lan HY. Identification of novel long noncoding RNAs associated with TGF-beta/Smad3-mediated renal inflammation and fibrosis by RNA sequencing. Am J Pathol 2014; 184: 409–417. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman M, Rinn JL. Modular regulatory principles of large non-coding RNAs. Nature 2012; 482: 339–346. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 2009; 25: 1105–1111. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. Renal fibrosis: new insights into the pathogenesis and therapeutics. Kidney Int 2006; 69: 213–217. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Martens-Uzunova ES, Bottcher R, Croce CM, Jenster G, Visakorpi T, Calin GA. Long noncoding RNA in prostate, bladder, and kidney cancer. Eur Urol 2014; 65: 1140–1151. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwar YS, Pan X, Lin S, Kumar A, Wada J, Haas CS et al. Imprinted mesodermal specific transcript (MEST) and H19 genes in renal development and diabetes. Kidney Int 2003; 63: 1658–1670. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K, Morison IM, Taniguchi T, Reeve AE. Epigenetic changes at the insulin-like growth factor II/H19 locus in developing kidney is an early event in Wilms tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997; 94: 5367–5371. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Xue JD, Chao F, Jin YF, Fu Q. Long non-coding RNA-H19 antagonism protects against renal fibrosis. Oncotarget 2016; 7: 51473–51481. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Shan SW, Lee DY, Deng Z, Shatseva T, Jeyapalan Z, Du WW et al. MicroRNA MiR-17 retards tissue growth and represses fibronectin expression. Nat Cell Biol 2009; 11: 1031–1038. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez IE, Eickelberg O. New cellular and molecular mechanisms of lung injury and fibrosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet 2012; 380: 680–688. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- King TE Jr., Pardo A, Selman M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet 2011; 378: 1949–1961. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- McKiernan PJ, Molloy K, Cryan SA, McElvaney NG, Greene CM. Long noncoding RNA are aberrantly expressed in vivo in the cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelium. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2014; 52: 184–191. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Cao G, Jing L, Lin S, Wang X, Zhang J et al. Analysing the relationship between lncRNA and protein-coding gene and the role of lncRNA as ceRNA in pulmonary fibrosis. J Cell Mol Med 2014; 18: 991–1003. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MI, Waksman J, Curtis J. Silicosis: a review. Dis Mon 2007; 53: 394–416. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X, Wu B, Fan J, Han R, Luo C, Wang T et al. The anti-fibrotic effects and mechanisms of microRNA-486-5p in pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 14131. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Han L, Yan W, Ji X, Han R, Yang J et al. miR-489 inhibits silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis by targeting MyD88 and Smad3 and is negatively regulated by lncRNA CHRF. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 30921. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kerem B, Rommens JM, Buchanan JA, Markiewicz D, Cox TK, Chakravarti A et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: genetic analysis. Science 1989; 245: 1073–1080. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Chen J, Qian W, Kang J, Wang J, Jiang L et al. Integrated long non-coding RNA analyses identify novel regulators of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis. J Cell Mol Med 2016; 20: 1234–1246. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Weinberg RA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: at the crossroads of development and tumor metastasis. Dev Cell 2008; 14: 818–829. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Mace KA, Hansen SL, Myers C, Young DM, Boudreau N. HOXA3 induces cell migration in endothelial and epithelial cells promoting angiogenesis and wound repair. J Cell Sci 2005; 118: 2567–2577. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Guo R, Hao G, Xiao J, Bao Y, Zhou J et al. The expression profiling and ontology analysis of noncoding RNAs in peritoneal fibrosis induced by peritoneal dialysis fluid. Gene 2015; 564: 210–219. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyaz A, Attisano L, Wrana JL. Recent advances in understanding contextual TGFbeta signaling. F1000Res 2017; 6: 749. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang S, Zhu G, Ouyang L, Luo Y, Zhou R, Pan C et al. Bapx1 mediates transforming growth factor-beta- induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and promotes a malignancy phenotype of gastric cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017; 486: 285–292. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T, Wong N. Transforming growth factor-beta-induced long noncoding RNA promotes liver cancer metastasis via RNA-RNA crosstalk. Hepatology 2015; 61: 722–724. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Articles from Experimental & Molecular Medicine are provided here courtesy of Korean Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/emm.2017.223

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.nature.com/articles/emm2017223.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

MIAT promotes myofibroblastic activities and transformation in oral submucous fibrosis through sponging the miR-342-3p/SOX6 axis.

Aging (Albany NY), 16(19):12909-12927, 07 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39379100 | PMCID: PMC11501384

Emerging roles of noncoding RNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Cell Death Discov, 10(1):443, 21 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39433746 | PMCID: PMC11494106

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Decoding LncRNA in COPD: Unveiling Prognostic and Diagnostic Power and Their Driving Role in Lung Cancer Progression.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(16):9001, 19 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39201688 | PMCID: PMC11354875

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Epigenetic mechanisms of particulate matter exposure: air pollution and hazards on human health.

Front Genet, 14:1306600, 17 Jan 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38299096 | PMCID: PMC10829887

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Epigenetic Regulation of EMP/EMT-Dependent Fibrosis.

Int J Mol Sci, 25(5):2775, 28 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38474021 | PMCID: PMC10931844

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (22) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Long non-coding RNA LUCAT1 is associated with poor prognosis in human non-small lung cancer and regulates cell proliferation via epigenetically repressing p21 and p57 expression.

Oncotarget, 8(17):28297-28311, 01 Apr 2017

Cited by: 51 articles | PMID: 28423699 | PMCID: PMC5438651

Potential Roles of Long Noncoding RNAs as Therapeutic Targets in Renal Fibrosis.

Int J Mol Sci, 21(8):E2698, 13 Apr 2020

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 32295041 | PMCID: PMC7216020

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Long Noncoding RNA (lncRNA) n379519 Promotes Cardiac Fibrosis in Post-Infarct Myocardium by Targeting miR-30.

Med Sci Monit, 24:3958-3965, 11 Jun 2018

Cited by: 19 articles | PMID: 29889825 | PMCID: PMC6027256

Long noncoding RNA: a new contributor and potential therapeutic target in fibrosis.

Epigenomics, 9(9):1233-1241, 15 Aug 2017

Cited by: 21 articles | PMID: 28809130

Review