Abstract

Free full text

Dopamine neurons create Pavlovian conditioned stimuli with circuit-defined motivational properties

Abstract

Environmental cues, through Pavlovian learning, become conditioned stimuli that guide animals towards the acquisition of “rewards” (i.e., food) that are necessary for survival. Here, we test the fundamental role of midbrain dopamine neurons in conferring predictive and motivational properties to cues, independent of external rewards. We demonstrate that brief phasic optogenetic excitation of dopamine neurons, when presented in temporal association with discrete sensory cues, is sufficient to instantiate those cues as conditioned stimuli that subsequently both evoke dopamine neuron activity on their own, and elicit cue-locked conditioned behavior. Critically, we identify highly parcellated functions for dopamine neuron subpopulations projecting to different regions of striatum, revealing dissociable dopamine systems for the generation of incentive value and conditioned movement invigoration. These results show that dopamine neurons orchestrate Pavlovian conditioning via functionally heterogeneous, circuit-specific motivational signals to create, gate, and shape cue-controlled behaviors.

The specific contributions of dopamine neurons to learning, motivation and reinforcement processes, as well as movement, are a longstanding subject of inquiry and debate. This is due in part to the prominent role dysfunction in dopamine signaling plays in both the motivational and motor aberrations that define addiction and Parkinson’s disease 1–3, but a major focus of this work is also on dopamine’s role in normal Pavlovian cue-reward learning. Manipulation of dopamine neurons can modify the learned value of reward-associated cues (conditioned stimuli, CSs) to alter reward-seeking behavior 4–6, and form contextual preferences 7. Despite the extensive research history on the subject it remains unknown if brief, phasic dopamine neuron activity, in the absence of physical reward, can directly assign conditioned properties to discrete sensory cues to make them CSs that elicit conditioned behaviors and, critically, how subpopulations of dopamine neurons 8 may differentially contribute to this process. Here we addressed this fundamental question using a Pavlovian cue conditioning procedure in which brief optogenetic activation of different groups of dopamine neurons was substituted for natural reward delivery. We find that most dopamine neurons instantiate conditioned stimulus properties in sensory cues, but the motivational value assigned to cues, and the corresponding behavioral consequences, depends on the specific dopamine circuit engaged.

RESULTS

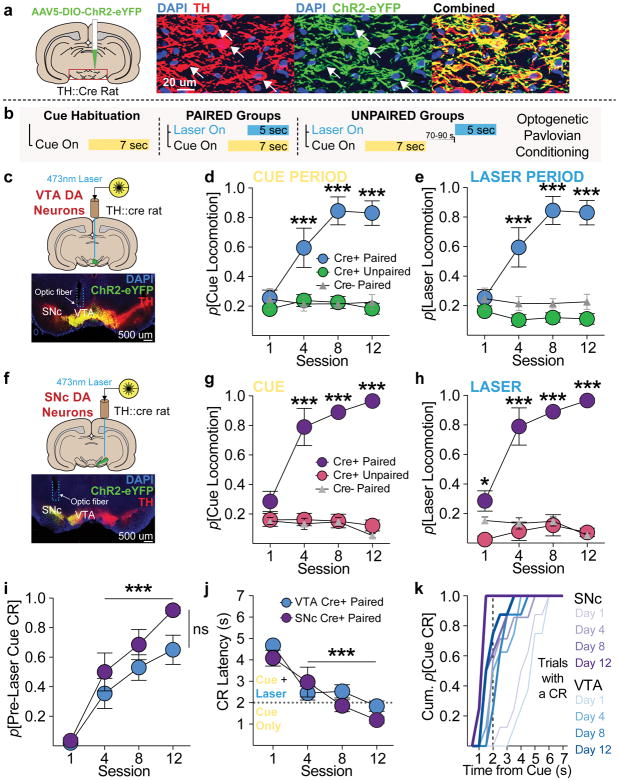

Dopamine neurons imbue environmental cues with conditioned stimulus properties

For selective manipulation of dopamine neurons, we expressed ChR2 in the ventral midbrain in tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-cre rats 9, which allowed for optogenetic targeting of TH+/dopamine neurons with ~97% specificity (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. 1). To compare the contribution of different dopamine neuronal subpopulations, optical fibers were implanted over ChR2-expressing dopamine neurons in either the ventral tegmental area (VTA) or substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) (Fig. 1c, f; Supplementary Fig. 2). To test the contribution of phasic dopamine neuron activity in the creation of conditioned stimuli, rats underwent optogenetic Pavlovian cue conditioning (Fig 1b). Rats in the paired groups received 25 overlapping cue (light+tone, 7-sec) and laser (473-nm; 5-sec at 20 Hz, delivered 2-sec after cue onset) presentations per session. The cue light was positioned on one wall of the chamber, within rearing height for an adult rat. To control for non-associative effects of repeated cues and optogenetic stimulation, separate rats were exposed to cue and laser presentations that never overlapped (unpaired groups). VTA and SNc cre+ paired groups both quickly learned conditioned responses (CRs), defined here simply as locomotion, during the 7-sec cue presentations, and these CRs emerged progressively earlier in the cue period across training for both groups (Fig. 1k; Supplementary Fig. 3). Cre+ unpaired and cre− controls did not learn CRs (Fig. 1d, g; Supplementary Fig. 3). The latency of CR onset in paired groups decreased across training, and, late in training, most CRs were initiated during the first 2-sec of each cue period, before laser onset, for both VTA and SNc cre+ paired groups (Fig. 1i–k). This indicates that behavior in paired subjects was a conditioned effect, elicited by cue presentations, rather than directly by laser stimulation. Further supporting this, optogenetic activation of dopamine neurons in cre+ unpaired groups failed to generate behavior statistically different from cre− controls, during either the cue or laser periods (Fig. 1e, h). These results show that, at least for the stimulation parameters used here, unsignalled phasic midbrain dopamine neuron activity in the VTA or SNc does not reliably act as an unconditioned or conditioned stimulus that can elicit behaviors. We conducted an additional experiment where rats received cue-laser paired conditioning similar to that described above, but optogenetic stimulation was limited to 1 sec per trial (20 5-ms pulses at 20 Hz, delivered in the final 1 sec of cue presentations). Here too, cue-evoked locomotion emerged, with the same probability as seen in the 5-sec laser conditioning groups (Supplementary Fig. 4). Together, our results suggest that the contiguous or contemporaneous occurrence of salient sensory cues at the time dopamine neurons are active serves as a critical gate on the ability of dopamine neurons to promote behavior. This provides important context to recent studies on the contribution of dopamine neurons to explicit unconditioned movements 10–12 and, broadly, associative learning.

(a) ChR2 was expressed in TH+ (dopamine) neurons in TH-cre rats (n=40). (b) Schematic of optogenetic Pavlovian conditioning task. After habituation to a novel, neutral cue, paired groups received cue and laser (473-nm) presentations that overlapped in time. Unpaired groups received cue and laser presentations separated in time by an average of 80 s. (c) Targeting ChR2-eYFP to TH+ neurons in the VTA (n=22). (d) Across training, conditioned responses (CRs; locomotion) emerged during the 7-s cue period for VTA cre+ paired rats (n=8), but not cre+ unpaired (n=8) or cre− paired (n=6) controls (p=probability; 2-way repeated measures (RM) ANOVA, session X group interaction, F(6,57)=11.85, p<0.0001; post hoc comparisons with Unpaired and cre− groups). (e) CRs did not emerge in unpaired (n=8) or cre− controls (n=6) during the 5-s laser period, compared to cre+ paired (n=8) rats (2-way RM ANOVA session X group interaction, F(6,57)=14.43, p<0.0001; post hoc comparisons with unpaired and cre− groups). (f) Targeting ChR2-eYFP to TH+ neurons in the SNc (n=18). (g) Cues evoked robust CRs in SNc cre+ cue-paired (n=8) rats, but not in unpaired (n=5) or cre− (n=5) controls (2-way RM ANOVA session X group interaction, F(6,48)=13.47, p<0.0001; post hoc comparisons with unpaired and cre− groups). (h) CRs did not emerge for SNc cre+ unpaired (n=5) or cre− controls (n=5) during the laser period, compared to cre+ paired rats (2-way RM ANOVA session X group interaction, F(6,48)=12.32, p<0.0001; post hoc comparisons with unpaired and cre− groups). (i,j) For VTA (n=8) and SNc cre+ (n=8) paired rats, across training, (i) the majority of CRs were initiated in the 2 s after cue onset but before laser onset (2-way RM ANOVA main effect of session, F(3,42)=53.16, p<0.0001; post hoc comparisons with day 1), indicating they were cue, rather than laser, evoked. (j) Accordingly, the latency of CR onset for cre+ paired (n=16) rats decreased across training (2-way RM ANOVA main effect of session F(3,42)=27.09, p<0.0001; post hoc comparisons with day 1). (k) On trials in which a CR occurred, the cumulative probability of CR occurrence at each second during the 7-sec cue presentations. CRs emerged earlier in the cue period across training for both VTA and SNc cre+ paired groups. Post hoc comparisons are Bonferroni corrected. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. *p< 0.05; ***p< 0.0001.

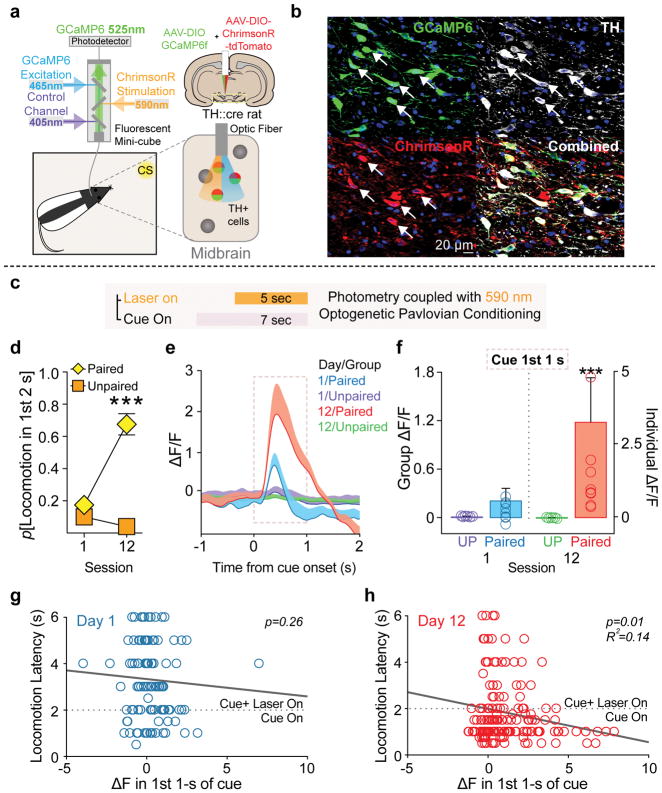

Dopamine neurons develop phasic increases in population-level activity to dopamine-predictive cues

Cues paired with natural reward evoke phasic activity in dopamine neurons, and dopamine release in striatal projection targets 13–16. Given that we found optogenetic stimulation of dopamine neurons induced conditioned behavior to discrete paired cues, we asked if dopamine neurons might acquire phasic neural responses to these paired cues, using fiber photometry 17. For simultaneous optogenetic stimulation and activity measurement in the same neurons, we co-transfected dopamine neurons with ChrimsonR, a red-shifted excitatory opsin, and the fluorescent calcium indicator GCaMP6f (Fig. 2a and b). This strategy led to a ~90% overlap of GCaMP6 and ChrimsonR expression in TH+ neurons below optic fiber placements in the midbrain (Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). Photoactivation of ChrimsonR (590-nm laser) led to rapid, stable increases in GCaMP6f fluorescence that tightly tracked the length of optogenetic stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 5d). To test the behavioral specificity of light activation of ChrimsonR, we confirmed that 590-nm activation of ChrimsonR-expressing dopamine neurons supported robust intracranial self-stimulation behavior (Supplementary Fig. 5e and f), which rapidly extinguished when the 590-nm laser was switched to a 473-nm laser (Supplementary Fig. 5f; session 3). We also recorded photometry signals as rats consumed 10μl of a 10% sucrose solution. This produced a multi-second calcium fluorescence increase that was similar to that evoked by a 5-sec laser train in the same animals (Supplementary Fig. 5g), indicating that, at least at the population level, the optogenetic conditioning procedure taps into innate reward mechanisms. We note, however, that optogenetic stimulation produces artificial neural activation patterns that do not fully mimic natural dopamine neuron activity.

(a) Schematic of fiber photometry system. Fiber photometry fluorescence measurements and optogenetic stimulation in the same dopamine neurons was achieved by co-transfecting TH+ neurons with DIO-GCaMP6f and DIO-ChrimsonR containing AAVs. (b) ChrimsonR and GCaMP6f co-expression in the same TH+ neurons in midbrain (n=13). (c) Fiber photometry measurements were made during optogenetic Pavlovian conditioning where neutral cues were paired with orange laser for activation of dopamine neurons. (d) Cues paired with optogenetic activation of dopamine neurons with ChrimsonR (n=8) develop conditioned stimulus properties to evoke locomotion, relative to unpaired (UP, n=5) controls (2-way RM ANOVA session by group interaction, F(1,12)=52.53, p<.0001; post hoc comparison between groups). (e) Phasic activity in dopamine neurons in response to dopamine-neuron-activation-paired cues developed across Pavlovian training, shown as ΔF/F of the normalized photometry signal. Shaded area represents analysis window. (f) Summary of mean normalized ΔF/F response during the 1st 1 s of cue presentations on the first and last session (2-way RM ANOVA session by group interaction, F(1,668)=48.30, p<.0001). (g) Scatterplot of the relationship between conditioned response latency on individual trials and change in fluorescence measured in the first 1 s after cue presentation, compared to the 1 s period before cue onset. A significant negative relationship emerged later in training, (h) where larger changes in fluorescence during the 1st 1-s of the cue occurred on trials where rats initiated conditioned locomotion faster (n= R2= 0.14, p=0.012). Data expressed as mean ± SEM. ***p< 0.0001.

To assess cue-evoked neural dynamics, we monitored dopamine neuron population fluorescence during optogenetic Pavlovian conditioning (Fig. 2c). As with the ChR2 experiments (Fig. 1), cues paired with ChrimsonR-mediated optogenetic activation of dopamine neurons came to reliably evoke conditioned behavior (Fig. 2d), relative to unpaired controls. In these cue-laser paired rats, we observed an increase in fluorescence at cue onset (preceding laser onset) that grew in magnitude across training (Fig. 2e & f), while no such cue-evoked signals emerged for unpaired control rats (Fig. 2e & f). A further trial-by-trial analysis revealed that, across training, on trials where a CR occurred, cue-evoked dopamine neuron activity became predictive of the latency of locomotion onset; larger magnitude cue-evoked fluorescence was associated with faster conditioned response initiation (Fig. 2g & h). These results show that dopamine neurons develop phasic activity to CSs they have directly established via their associated activation, in the absence of the constellation of sensory inputs that typically accompany seeking and consumption of natural rewards. Further, the magnitude of phasic cue-evoked population-level dopamine neuronal activity encodes the vigor of conditioned behavior.

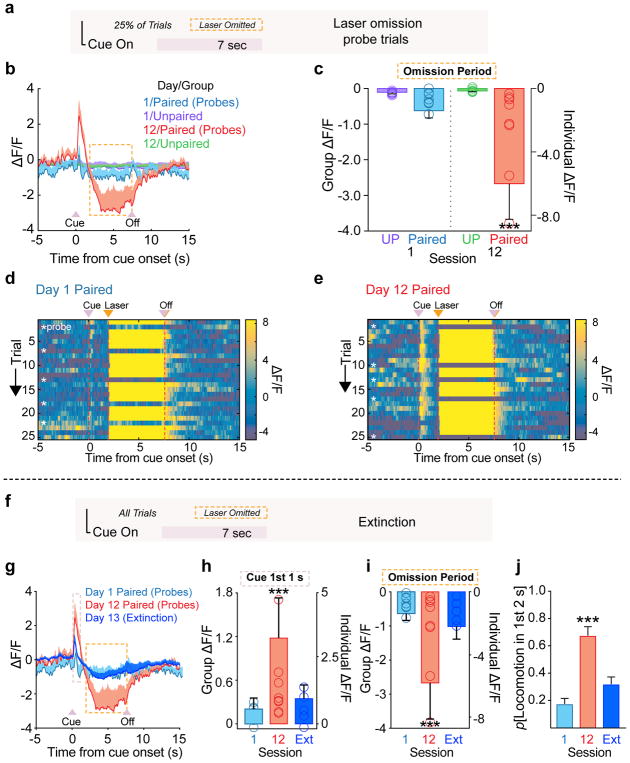

Cue-evoked dopamine neuron activity reflects expectation of dopamine neuron activity

On the first and last day of optogenetic conditioning, we included probe trials (Fig. 3a, 25% of the total) in which cues were delivered but laser was omitted. On these trials, dopamine neuron activity in paired rats decreased at the time laser would have been delivered (Fig. 3b). This omission-related decrease in fluorescence developed across conditioning, and was not seen in unpaired controls (Fig. 3b–e). These results parallel electrophysiological recordings of dopamine neurons demonstrating a pause in their firing during the omission of expected food or water 16, which is thought to be mediated by recruitment of local GABAergic neuron activity 18. Our data suggest that natural reward exposure is not necessary to engage such midbrain plasticity mechanisms in Pavlovian learning 19.

(a) On 25% of trials in the first and last training session, laser was omitted from the paired groups. (b) Photometry signal from probe trials in the paired groups, with unpaired control shown for comparison. On session 12 for the paired group, following the cue-evoked spike in activity, a corresponding dip in fluorescence occurs at the time when laser stimulation would have been delivered. (c) Summary of mean normalized ΔF/F response during the omission period (session by group interaction, F(1,108)=11.943, p=.0008). (d and e) Trial-by-trial heatmaps for a paired rat during Day 1 (d) and 12 (e) of conditioning. Cue, laser, and laser-omission related responses are evident on Day 12. (f) An extinction session occurred after training, where all cues were presented without laser stimulation. (g) The cue and omission-related fluorescence changes extinguishes rapidly, compared to the final day of paired conditioning. (h) Summary of mean normalized ΔF/F response during the 1st 1 s of cue presentations during extinction and the probe trials in session 1 and 12 (effect of session, F(2,459)=10.03, p=.0016). (i) Summary of mean normalized ΔF/F during the laser omission period across sessions (effect of session, F(2,179)=46.276, p<.0001). (j) Behavior evoked by the cue rapidly extinguished, compared to the final session of training (effect of session, F(2,18)=23.37, p<.0001). Data expressed as mean ± SEM. ***p< 0.0001.

We next conducted an extinction session, during which these rats received 25 cue presentations, but no laser stimulation was delivered (Fig 3f). This resulted in rapid reduction, to levels observed in session one, of the cue-evoked fluorescence spike (Fig. 3g,h) as well as the omission-related dip in fluorescence (Fig. 3i). Extinction of the neural signal tracked behavioral extinction, such that after one extinction session, behavior evoked by the cue diminished to a level comparable to the first training session (Fig. 3j). Thus, rapid adjustments in the population-level activity of dopamine neurons track extinction of stimulation-evoked learning. Together, the above findings demonstrate neural encoding of the predictive relationship between these cues and direct dopamine neuron activation.

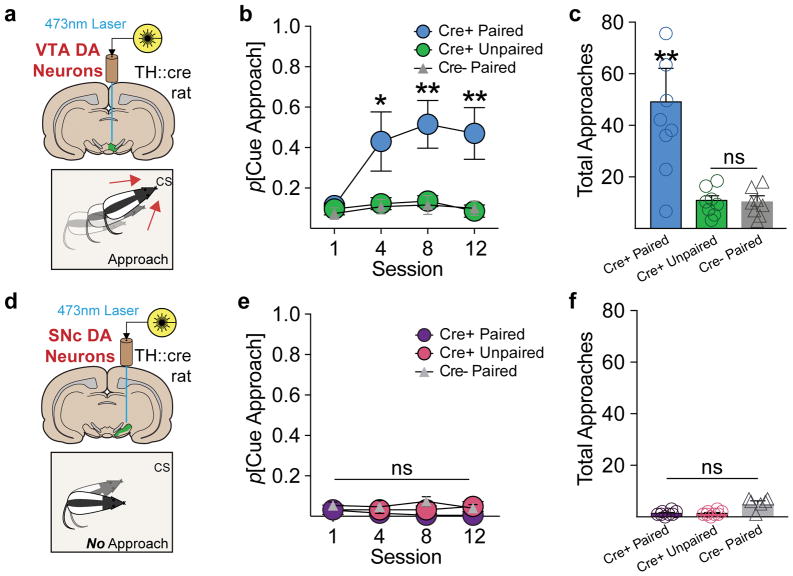

VTA and SNc dopamine neurons confer distinct motivational properties to cues

Reward-associated CSs direct actions not only by serving as reward predictors that come to evoke neural activity, but also by acquiring reward-like incentive value. ‘Incentive value’ here is defined as that property of cues that lends them motivational power to attract attention and become desirable in the absence of reward, an important process that may contribute to compulsive seeking in addiction 1. The acquisition of incentive value does not necessarily accompany the acquisition of predictive value 15, and so we next asked if VTA and SNc dopamine-associated CSs acquired incentive value. To do this, we examined the detailed structure of behavior during Pavlovian conditioning in ChR2-conditioned groups. In response to cue presentations, cre+ paired VTA rats (Fig. 4a) showed cue-directed approach behavior, moving to come into proximity (< 1 in) with the cue light while it was illuminated (Fig 4b, c; Supplementary Fig. 6; Video 1). This “attraction” conditioned response is a standard behavioral index of the attribution of incentive motivational value to a CS 15,20. Critically, cre+ paired SNc rats did not develop approach behavior (Fig. 4d–f). VTA approach probability did not relate to subjects’ proximity to the cue before cue onset (Supplementary Fig. 7), and was not observed in unpaired or cre− controls (Fig 4b, c; Supplementary Videos 2–5). These results suggest that VTA, but not SNc, dopamine neurons confer incentive value to CSs, and this process does not require typical reward-elicited neuronal processes other than dopamine neuron activation.

(a) VTA dopamine-paired cues support cue approach/interaction. (b) Approach and interaction with the visual cue associated with optogenetic stimulation developed for VTA cre+ paired rats, but not control groups (session X group interaction, F(6,57)=2.304, p<0.05; post hoc comparisons with unpaired and cre− groups). (c) VTA cre+ paired rats made significantly more total cue approaches across training, compared to controls (main effect of group, F(6,57)=8.394, p<0.001; post hoc comparisons with unpaired and cre− groups). (d) SNc dopamine-paired cues do no support approach. (e) In contrast to the VTA group, cue approach did not develop for cre+ paired SNc rats, relative to controls (no session X group interaction, F(6,48)=0.637, p=0.7). (f) SNc groups made almost zero total approaches across training. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. **p< 0.01.

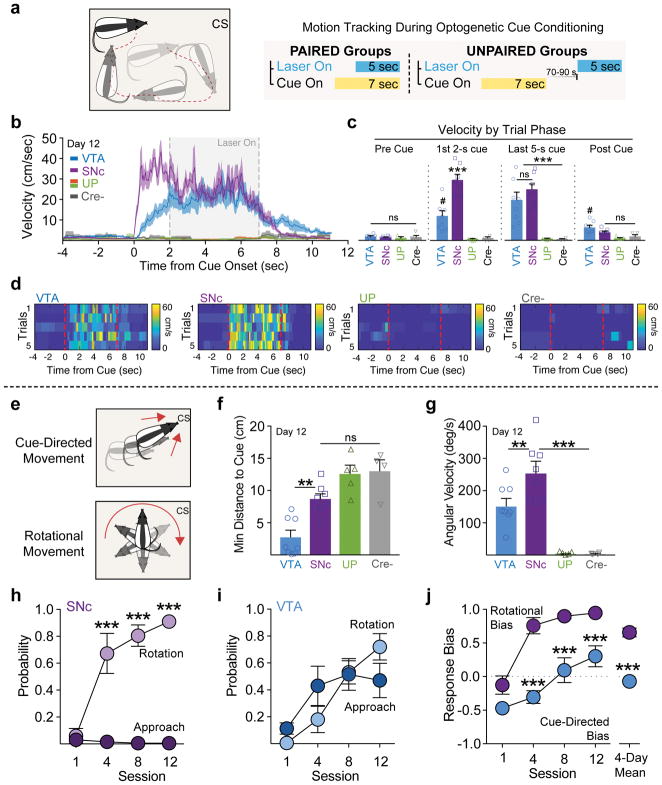

While SNc dopamine paired rats did not develop approach behavior, we observed vigorous locomotion in these rats during cue presentations, but which was not directed at the cue. To quantify this conditioned movement, and compare it to the other groups, we analyzed behavioral videos using motion tracking to interpolate rats’ positions in the experimental chamber in the periods before, during, and after cue presentations on the final day of conditioning (Fig. 5a). We used this position information to determine the frame-by frame velocity and the distance of the rats’ heads from the cue. This tracking revealed that, at cue onset, cre+ paired SNc rats initiated rapid movement, reaching peak velocity within ~1 sec (Fig. 5b). The timing of movement onset and mean velocity in the first 2-sec of the cue was significantly greater for SNc rats than for cre+ VTA paired rats. In this analysis, unpaired and cre− controls did not show cue or laser evoked movement (Fig. 5a–d), consistent with our earlier results. During the last 5-sec of cue presentations, corresponding to the laser stimulation period, SNc and VTA paired rats exhibited stable and similar movement speeds, and velocity quickly returned to low levels after cue offset (Fig. 5a–d). Together with our photometry data, the movement analysis suggests that Pavlovian conditioned dopamine neuron signals, in addition to spontaneous dopamine neuron signals 10,11, are involved in the generation of vigorous movements, and more so for SNc, compared to VTA, dopamine neurons.

(a) Rat position before, during, and after cue presentations was quantified with automated motion tracking software (b) This resulted in velocity (cm/s) traces and position information for each experimental animal. (c) Before cue onset, all rats were at rest, exhibiting low levels of movement (Pre-cue velocity, no effect of group, F(3,21)=1.165, p=.347). Cue onset elicited rapid, vigorous movement for SNc cue paired rats (n=8), relative to VTA paired (n=8) and unpaired (UP, n=13) and cre− (n=11) controls (1st 2-sec velocity, effect of group, F(3,21)=32.39, p<.0001; ***post hoc comparison vs VTA and UN, p<.0001; #post hoc comparison vs UN, p=.01). SNc and VTA paired rats exhibited similar sustained velocity during the rest of the cue and laser period, while UN and cre− controls remained immobile (Last 5-s cue, effect of group, F(3,21)=16.45, p<.0001; post hoc comparison to UP). (d) Heat maps depicting velocity on individual trials for a representative rat from each group. UP and cre− rats exhibit almost no movement. (e) Cue-directed movement (approach) and rotational movement on the final session were compared using the automated behavior tracking data. (f) VTA paired were biased toward cue-directed movement, reaching a significantly smaller minimum distance to the cue, compared to SNc and control groups, who did not differ (effect of group, F(3,21)=18.06, p<.0001, post hoc comparison between groups). (g) SNc paired rats showed a bias towards rotational movement, reaching a faster angular velocity compated to VTA rats (effect of group, F(3,21)=17.02, p<.0001, post hoc comparison between groups). (h) Directly comparing the likelihood of each type of movement, only cue-evoked rotational movement developed for SNc cre+ paired rats, which was expressed exclusively on nearly every trial by the end of training (interaction of conditioned response (CR) type x session, F(3,21)=30.88, p<.0001; post hoc comparison between CR types). (i) VTA paired rats showed cue-directed and rotational, which became intermixed across Pavlovian training (interaction of CR type x session, F(3,21)=4.341, p=0.016). (j) To quantify rats’ cue-directed/rotational bias, a CR Score was calculated, consisting of (X + Y)/2, where Response Bias, X, = (# of turns – # of approaches)/(# of turns + # of approaches), and Probability Difference, Y = (p[rotation] – p[approach]). VTA rats transitioned from an initial cue-directed bias to a mixed cue-directed/rotational score, while SNc rats showed an early and stable rotational bias (interaction of group x session, F(3,42)=3.933, p=0.015); post hoc comparison between groups; unpaired 2-tailed t test on 4-day mean, t14=7.287, p<0.0001). Data expressed as mean ± SEM. ***p< 0.0001.

During extended conditioned movements, rats turned in circles within the chamber, directed contralateral to the simulation hemisphere. We quantified this movement as “rotations” and compared their occurrence to cue-directed movement (Fig. 5e, Supplemental Fig. 8). In agreement with the experimenter-scored behavior data (Fig. 4), motion tracking analysis revealed a cue-directed movement bias for VTA paired rats, who, on average, came closer to the cue during its presentation, compared to SNc rats and controls (Fig. 5f, Supplemental Fig. 8). SNc paired rats, in contrast, showed a bias towards rotational movement, reaching a faster angular velocity, relative to VTA rats (Fig. 5g). While SNc rats showed an exclusive rotational movement phenotype throughout training (Fig. 5h & j), VTA paired rats also developed rotational movement as training progressed, resulting in a mixed cue-directed vs. rotational movement behavioral phenotype (Fig. 5i & j). The transition of VTA rats from purely linear, cue-directed movement to rotational movement could reflect the progressive recruitment of ascending serial midbrain-striatal circuits across extended training 21, culminating in cue-related dorsal striatal dopamine release and behavioral control 22,23, especially if more lateral VTA dopamine neurons, which may contribute more directly to movement 10, are engaged. Together these results show that VTA and SNc dopamine neurons contribute to conditioned cue attraction and conditioned movement invigoration in distinct ways, and on different timescales throughout the progression of Pavlovian learning.

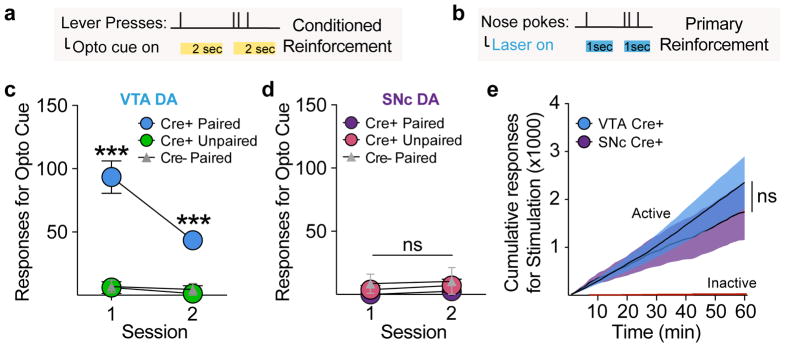

In addition to being attractive, cues with incentive value can also become desirable, in that they reinforce actions that lead to their procurement. This process is critical for durable reward-seeking behaviors when reward is not immediately available. Building on the results shown above (Fig. 4), we next asked if VTA and SNc dopamine optogenetically-conditioned CSs could subsequently serve as conditioned or “secondary” reinforcers, to support performance of a new action in the absence of optogenetic stimulation (Fig. 6a). Previously-conditioned Cre+ paired VTA (Fig. 6c), but not SNc (Fig. 6d) rats readily pressed a lever to receive conditioned cue presentations in absence of laser activation, indicating that the instantiation of conditioned reinforcement, a canonical test of incentive value properties of cues, is specific to VTA dopamine neurons. Furthermore, this shows that, while SNc-paired cues can generate vigorous movement (Fig. 5) the content of the signal conditioned through SNc dopamine neurons in Pavlovian learning is fundamentally distinct from VTA dopamine neurons.

(a) Conditioned reinforcement test, where lever presses produced the cue previously paired with dopamine neuron stimulation, but no laser. (c) VTA cre+ paired rats made instrumental responses for cue presentations in the absence of laser, relative to controls (2-way RM ANOVA, main effect of group, F(2,19)=27.18, p<0.0001; post hoc comparisons with unpaired and cre− groups). (d) SNc cre+ paired rats did not respond for cue presentations, relative to controls (2-way RM ANOVA, no effect of group, F(2,16)=1.407, p=0.274). (b) Primary reinforcement test, where nose poke responses produced optogenetic stimulation of dopamine neurons. (e) VTA (n=16) and SNc (n=13) cre+ rats made a similar number of instrumental responses for dopamine neuron activation (2-way RM ANOVA, no effect of group, F(1,27)=0.227, p=0.638). Data expressed as mean ± SEM. ***p< 0.0001.

Finally, we assessed the primary reinforcing value of dopamine neuron activation in an intracranial self-stimulation paradigm 9, where nose pokes resulted in a brief laser train delivery, with no associated cues (Fig. 6b). Unlike the anatomical dissociation in conditioned reinforcement, VTA and SNc dopamine neuron stimulation produced similar levels of primary reinforcement (Fig. 6e). Taken together, our results show that brief, phasic activity of VTA dopamine neurons is sufficient to apply incentive value to previously neutral environmental cues to promote attraction and create conditioned reinforcement. SNc dopamine neuron activity, alternatively, imbues cues with conditioned stimulus properties that promote movement invigoration more generally. Direct reinforcement of an instrumental action, in contrast to these divergent Pavlovian cue conditioning functions, is perhaps a common currency across VTA and SNc dopamine neurons 9,24.

Different striatal dopamine projections make unique contributions to Pavlovian learning

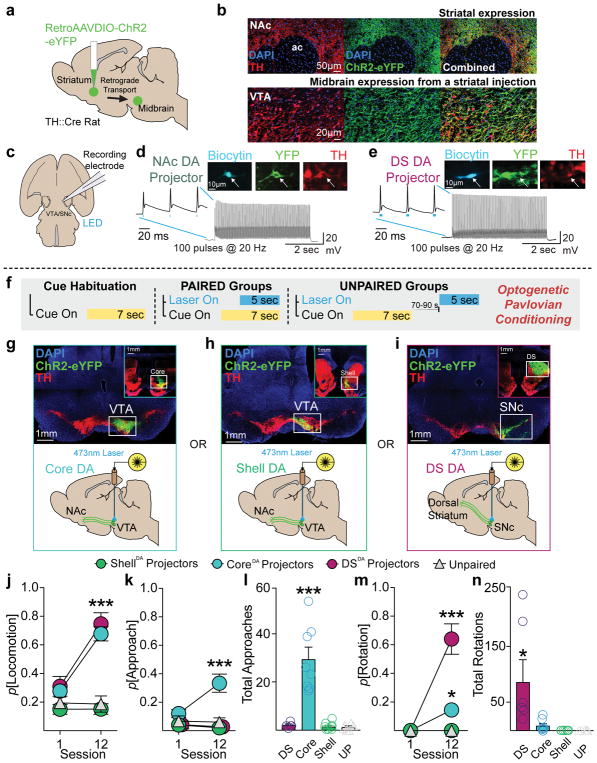

Dopamine signaling within distinct striatal compartments can modulate the value of reward-associated cues 25–28, but it is unknown if phasic activity from distinct dopamine projections to different striatal areas can support Pavlovian learning. Given this mesostriatal complexity, and that the VTA manipulations described above could impact dopamine projections to non-striatal targets 29, we next determined if dopamine neurons projecting into sub-regions of the striatum would assign conditioned stimulus and incentive properties to optogenetically-conditioned cues. We transfected the striatum of TH-cre+ rats with a retrogradely-transported AAV vector containing ChR2, which produced robust expression in dopamine neurons in the midbrain (Fig. 7a and b). Ex vivo electrophysiological recordings showed that ChR2-expressing dopamine neurons projecting to the ventral striatum/nucleus accumbens (NAc) and dorsal striatum (DS) reliably fired action potentials upon 20-Hz blue light stimulation (Fig. 7c–e; Supplementary Fig. 9). In separate groups of rats, we targeted injections to dopamine terminals in the NAc core, NAc medial shell, or DS, which resulted in projection-defined expression patterns among TH+ neurons in the midbrain (Supplementary Fig. 10). Cell bodies of dopamine projections to the shell were concentrated in the ventromedial VTA (Fig 7g; Supplementary Fig. 10), projections to the core were concentrated in the dorsolateral VTA (Fig. 7h; Supplementary Fig. 10), and DS projections occupied the medial-lateral extent of the SNc (Fig. 7i; Supplementary Fig. 10). We targeted optic fibers over the midbrain in these animals for projection-specific activation during optogenetic conditioning (Fig. 7f–i). Cues paired with VTA-CoreDA and SNc-DSDA, but not VTA-ShellDA projectors evoked conditioned behavior, relative to unpaired controls (Fig. 7j). Examining the detail of the behavioral responses in our projection-specific experiments, we found that only VTA-CoreDA neurons supported cue approach (Fig. 7k & l), while SNc-DSDA neurons preferentially promoted rotational movement during cue presentations (Fig. 7m & n).

(a) Viral strategy for targeting specific dopamine projections via retrograde AAV-DIO-ChR2 transport. (b) Transfection in striatum of TH-cre rats led to robust expression of ChR2-eYFP in TH+ cells in the midbrain. (c) Retrogradely-targeted neurons in the VTA and SNc were recorded in an ex vivo preparation. (d) Example ChR2 retrogradely-transfected nucleus accumbens-projecting dopamine neuron with high fidelity spike trains in response to a 5-s, 100-pulse, 20-Hz stimulation. (e) Example retrogradely-transfected DS-projecting dopamine neuron with high fidelity spike trains in response to blue LED pulses. (f) Rats underwent optogenetic Pavlovian cue conditioning of different dopamine neuron projections. (g) Retrograde AAV injections targeted to the NAc core resulted in expression in VTA, where optic fibers were placed. (h) Injections targeted to the NAc shell resulted in expression in the VTA. (i) Injections targeted to the DS resulted in expression in the SNc. (j) SNc-DSDA (n=6) and VTA-CoreDA (n=8), but not VTA-ShellDA (n=8) paired rats developed conditioned behavior (i.e., locomotion) in response to laser-paired cues, relative to Unpaired rats (2-way RM ANOVA, main effect of group F(3,24)=28.17, p<.0001; group by session interaction, F(3,24)=13.88, p<.0001; post hoc comparison relative to the Unpaired group). (k) Only VTA-CoreDA paired rats developed conditioned approach to the cue (main effect of group F(3,24)=19.54, p<.0001; group by session interaction, F(3,24)=5.127, p=.007; post hoc comparison relative to the Unpaired group). (l) Only VTA-CoreDA rats made a significant number of approaches across training (main effect of group, F(3,24)=24.55, p<.0001, post hoc comparison to Unpaired group). (m) SNc-DSDA rats preferentially developed conditioned rotation, reflecting vigorous movement, in response to the Pavlovian cue (main effect of group F(3,24)=33.09, p<.0001; group by session interaction, F(3,24)=33.09, p<.0001; post hoc comparison relative to the Unpaired group). (n) Only SNc-DSDA rats made a significant number of rotations across training, relative to unpaired controls (main effect of group F(3,24)=5.486, p=.005, post hoc comparison relative to the Unpaired group). Data expressed as mean ± SEM. ***p< 0.0001.

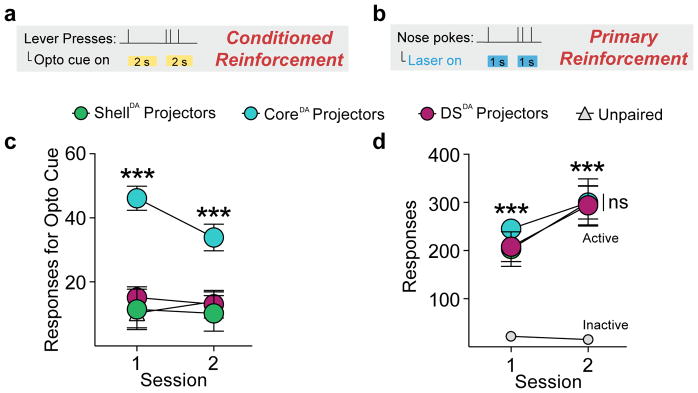

Finally, after dopamine projection-specific optogenetic conditioning (Fig. 8a), only VTA-CoreDA associated cues acted as conditioned reinforcers (Fig. 8b, d). Primary reinforcement, in contrast, was similar for all projection groups (Fig. 8c, e). Thus, dopamine neurons confer heterogeneous conditioned motivational signals about cues in a projection-defined manner, with the projection to the NAc core mediating the acquisition of incentive value.

(a) Optic fibers were implanted over the VTA or SNc for selective optogenetic stimulation of NAc core, NAc shell, or DS-projecting dopamine neurons. (b and d) In a test of conditioned reinforcement for an optogenetically-conditioned Pavlovian cue, VTA-CoreDA cre+ paired rats (n=9) responded robustly for cue presentations, relative to VTA-ShellDA cre+ paired (n=7) and SNc-DSDA cre+ paired rats (n=9), while VTA-ShellDA paired and SNc-DSDA paired rats were no different from unpaired (n=9) controls (2-way repeated measures ANOVA, main effect of group, F(3,30)=13.08, p<0.0001; post hoc comparisons between groups). (c and e) In a test of primary reinforcement, VTA-CoreDA (n=6), VTA-ShellDA (n=6), and SNc-DSDA (n=8) groups made a similar number of responses for optogenetic stimulation (2-way RM ANOVA, no effect of group, F(2,16)=0.142, p=0.869; post hoc comparison relative to inactive responses). Data expressed as mean ± SEM. ***p< 0.0001.

Discussion

Here we trained rats to associate sensory cues with optogenetic activation of dopamine neurons. We found that, by virtue of a temporal pairing, the cues acquired conditioned stimulus properties that allowed them to evoke conditioned behaviors and conditioned dopamine neuron activity. Critically, the topography of behavior evoked by conditioned cues varied according to which dopamine neuron subpopulation was targeted. These results demonstrate a fundamental dissociation in the function of dopamine neurons in Pavlovian conditioned motivation, where VTA-associated cues acquire incentive motivational value, and SNC-associated cues invigorate intense locomotion. We further found that the incentive value function was specific to NAc-core, but not shell, projecting dopamine neurons. Together, our studies reveal highly specialized functional isolation for mesostriatal dopamine circuits in distinct components of Pavlovian reward.

Dopamine neurons have heterogeneous motivational functions

Our results confirm a longstanding, fundamental assumption in reward neuroscience – that activity in dopamine neurons can create Pavlovian conditioned stimuli that elicit conditioned behaviors. While our activation can be seen as essentially mimicking the phasic activity proposed to act as a reward prediction error, we show that dopamine neurons do not merely update Pavlovian associations between cues and external rewards 4, they directly confer value and can do so in the absence of normal sensory inputs and the other corresponding brain processes that typically accompany natural reward exposure and consumption. We extend previous studies 7 by showing that discrete, transient cues become conditioned stimuli via association with relatively brief bursts (~1–5 sec) of dopamine neuron activity. Importantly, our results define the default behavioral responses conditioned by cue-paired phasic dopamine signals in relation to different dopamine neuron populations.

We demonstrate that conditioned stimulus instantiation is a function generally present in the major dopamine neuron output systems in the ventral midbrain, the VTA and SNc (Fig. 1). We found that these conditioned stimuli came to evoke population-level activity in dopamine neurons themselves (Fig. 2), in line with what has been previously demonstrated with single unit recordings during natural (i.e., food) cue conditioning 13,16,30. This cue-evoked dopamine neuron activity evinced a relationship with behavior as a consequence of Pavlovian conditioning, and fluctuations in this signal tracked a learned expectation of dopamine neuron activity (Fig. 3). Thus, a basic function of dopamine neurons in Pavlovian conditioning is to accumulate and signal predictive information about the probability of future dopamine neuron activity, a phenomenon that fundamentally does not require elaboration of further brain processes normally triggered by an external food reward beyond the elicitation of dopamine activity itself. Once learned, the phasic, cue-evoked dopamine neuron signals functionally represent the motivational value of cues that predict future dopamine neuron activity, which manifests as the vigor or intensity of conditioned behavior 5,31,32, the details of which depend on the dopamine projection engaged. Given the absence of an external reward, our studies do not reveal how dopamine neuron activation may contribute to associations among specific sensory/identity properties of external rewards and the cues that predict them. Dopamine can contribute to both a general and an outcome-specific form of learning in natural reward conditioning 33,34, suggesting that the sensory qualities and concomitant brain dynamics of the unconditioned stimulus that produces dopamine neuron activation are likely critical for determining the content of the association learned. Our experiments probed the function of dopamine systems absent outcome-specific information, revealing fundamental roles of dopamine neurons that may well be recruited in situations requiring more complex associations.

A primary finding here is that dopamine neurons in the VTA and SNc exhibited divergent conditioned motivational functions. VTA, but not SNc dopamine neurons conferred a signal that made those cues attractive and reinforcing on their own (Figs. 4 and and6),6), two properties demonstrating the incentive value of reward cues, and most likely the explanation for the behavioral patterns observed here. These results build on a large body of research implicating dopamine signaling in cue attraction and conditioned reinforcement 15,20,26,27,35,36, by showing that some dopamine neurons create these properties during Pavlovian conditioning, in the absence of reward receipt or consumption. We found that SNc dopamine neurons, alternatively, conferred a more general movement invigoration signal (Fig. 5); cues paired with their activation evoked vigorous movement not directed at the cue, and they failed to serve as conditioned reinforcers. Thus, distinct components of conditioned reward are represented and controlled by different dopamine output systems. While nigrostriatal dopamine neurons do not appear to instantiate incentive value per se in Pavlovian conditioned stimuli, they do confer their own important motivational properties, however, evidenced here by vigorous cue-evoked movement, perhaps akin to a learned “motor motivation” 37. In the absence of a VTA-mediated incentive component to orient and guide animals to a specific target, direct engagement of SNc-dopamine-mediated learning might manifest as a general increase in locomotion. Notably, dorsal striatal dopamine transmission is not required for the expression of approach to Pavlovian conditioned cues 38, but the dorsal striatum is necessary for the ability of Pavlovian conditioned cues to invigorate ongoing instrumental actions 39, which could be an expression of the conditioned movement invigoration reported here. Thus, in natural learning situations involving external rewards, motivation to engage in specific movements/actions, signaled by SNc dopamine, would be incorporated with motivation to achieve specific rewarding outcomes, signaled via VTA dopamine. Future work will be needed to explore the motivational content conferred by SNc dopamine neurons, how dorsomedial and dorsolateral projecting dopamine neurons may differ 40–42 and, critically, how VTA and SNc dopamine circuits interact across learning to fine-tune reward seeking.

Here we show that at least some types of movements reflect a conditioned state resulting from an association between dopamine neuron activity and the presentation of external sensory cues: un-cued dopamine neuron activation did not generate locomotion. This provides context for important recent work assessing the role of dopamine neuron activity during self-initiated or spontaneous movements 10–12. Our findings suggest that dopamine-mediated movements that are not self-generated are gated by the presence of salient sensory stimuli. Notably, movement patterning is dependent on sensory input 43 and conditioning with visual cues can improve movement deficits in Parkinson’s patients 44. Thus, external signals are critical for normal expression of movement, and our results suggest that dopamine neurons contribute to this process perhaps by assigning motivational value to cues, allowing them to draw attention and invigorate, shaping locomotion.

Dopamine circuit-specific functions in Pavlovian reward learning

Our results are among the first to isolate distinct conditioned motivational functions for phasic activity among specific dopamine projections (Figs. 7 and and8),8), providing an important step towards understanding how dopamine neurons orchestrate Pavlovian reward moment-to-moment at the circuit level. We found that NAc core and dorsal striatal projecting dopamine neurons created conditioned stimuli out of previously neutral sensory cues, and acquired motivational value to promote cue attraction and conditioned reinforcement 15,25,28, and movement invigoration, respectively. NAc medial shell dopamine neurons, however, did not confer conditioned stimulus properties, even though their optogenetic activation produced primary reinforcement comparable to the other dopamine projections. Many previous studies have implicated NAc shell dopamine signaling in reward learning and incentive motivation 27,45, but our results suggest that while medial shell dopamine release may be engaged during reward learning, phasic activity in shell-projecting dopamine neurons is not sufficient to drive cue learning per se. It is possible that medial shell dopamine actions in Pavlovian learning may functionally act on longer timescales during behavior, which are not captured in the current studies. Additionally, medial shell dopamine, and activity from shell medium spiny neurons (MSNs), may more directly control reward consumption and evaluation, rather than prediction 46–48.

Among dopamine neurons, there is considerable genetic, anatomical, and physiological diversity 8. While some properties of medial accumbens shell dopamine neurons have been compared to those projecting to the dorsal striatum, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala 49, less is known about how medial shell and core inputs differ. The medial shell may receive relatively more input from VTA neurons that co-release dopamine and glutamate that are concentrated in the medial VTA 8, and medial shell neurons have unique connectivity patterns in the VTA, compared to lateral accumbens neurons 50. In the rat, medial shell MSNs project most heavily back to the VTA, while lateral shell/core MSNs project more broadly, including to the SNc. This potentially broader circuit access may be permissive for rapid dopamine signaling in the NAc core, but not shell, to engage Pavlovian learning mechanisms that produce overt conditioned behaviors, as they do here.

Conclusions

In summary, we show that brief, phasic dopamine neuron activity can create a conditioned stimulus in the absence of external reward. Our studies provide important context to previous research suggesting a uniform contribution of dopamine neurons to stimulus-reward learning 30, and unconditioned dopamine signaling 10, by showing that considerable heterogeneity exists in the functional content of information induced by different dopamine neurons during conditioning 41. Circuit-defined dopamine neuron activity induced learning of cue-guided behavior by directing behavior towards cues themselves or by allowing cues to more nonspecifically invigorate movement. The combination of both forms of cue-guided behavior may be necessary for successful reward seeking under changing conditions and environments. Finally, because the animals in our studies never received a traditional food reward, yet developed the type of cue-evoked behaviors typically seen during conditioned reward seeking, our studies suggest that dopamine systems are specialized for supporting and engendering circuit-specific adaptations that promote the expression of discrete classes of motivated behavior in response to reward cues. While normally these sensory cues may signal opportunity for reward, actual commerce with an external reward is not required for the acquisition of cue-evoked behaviors, and, strikingly, the acquisition of conditioned incentive motivation by cues.

Data Availability

The data supporting these findings are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Methods

Subjects

Male and female Th-cre transgenic rats (on a Long-Evans background) were used in these studies. These rats express Cre recombinase under the control of the tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) promoter in over 60% of all TH+ neurons in the midbrain 9. Wild-type littermates (Th-cre-) were used as controls. After surgery rats were individually housed with ad libitum access to food and water on a 0700 to 1900 light/dark cycle (lights on at 0700). All rats weighed >250 g at the time of surgery and were 5–9 months old at the time of experimentation. Experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of California, San Francisco and at Johns Hopkins University and were carried out in accordance with the guidelines on animal care and use of the National Institutes of Health of the United States.

Viral Vectors

For optogenetic conditioning experiments, Cre-dependent expression of channelrhodopsin was achieved via injection of AAV5-Ef1α-DIO-ChR2-eYFP (titer 1.5–4e12 particles/mL, University of North Carolina) into the VTA or SNc. For projection-specific experiments, AAV2/5-Ef1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-eYFP-WPRE-hGH (1.5–4e12 particles/mL, University of Pennsylvania), which exhibits retrograde transport 51, was injected into the NAc core or dorsal striatum. For combined optogenetic stimulation and photometry experiments, a mixture of AAVDJ-Ef1α-DIO-GCaMP6f (titer 1.0–3.9e12, Stanford University) and AAV9-hSyn-FLEX-ChrimsonR-tdTomato (1.5–4e12 particles/mL, University of Pennsylvania) was injected into the VTA.

Surgical Procedures

Viral infusions and optic fiber implants were carried out as previously described 52. Rats were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and placed in a stereotaxic frame, after which anesthesia was maintained at 1–3%. Rats were administered saline, carprofen anesthetic, and cefazolin antibiotic intraperitoneally. The top of the skull was exposed and holes were made for viral infusion needles, optic fiber implants, and 5 skull screws. Viral injections were made using a microsyringe pump at a rate of 0.1μl/min. Injectors were left in place for 5 min, then raised 200 microns dorsal to the injection site, left in place for another 10 min, then removed slowly. Implants were secured to the skull with dental acrylic applied around skull screws and the base of the ferrule(s) containing the optic fiber. At the end of all surgeries, topical anesthetic and antibiotic ointment was applied to the surgical site, rats were removed to a heating pad and monitored until they were ambulatory. Rats were monitored daily for one week following surgery. Optogenetic manipulations commenced at least 4 weeks (6–8 weeks for photometry and projection-specific studies) after surgery.

Midbrain cell body targeting

AAV5-Ef1α-DIO-ChR2-eYFP was infused unilaterally (0.5 to 1 μl at each target site, for a total of 2–4 μl per rat) at the following coordinates from Bregma for targeting VTA cell bodies: posterior −6.2 and −5.4mm, lateral +0.7, ventral −8.4 and −7.4. For targeting SNc dopamine cell bodies: posterior −5.8 and −5.0, lateral +2.4, ventral −8.0 and −7.0. Custom-made optic fiber implants (300-micron glass diameter) were inserted unilaterally just above and between viral injection sites at the following coordinates. VTA: posterior −5.8, lateral +0.7, ventral −7.5. SNc: posterior −5.3, lateral +2.4, ventral −7.3.

Projection-specific ChR2 targeting

The retrogradely-traveling AAV2/5-Ef1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-eYFP-WPRE-hGH was infused unilaterally into the NAc core, shell, or dorsal striatum. Two injections of 0.5 μl each (1μl total per rat) were given along the anterior-posterior axis at these coordinates from Bregma. NAc core: anterior +2.2 and +1.6, lateral +1.6, ventral −7.0. NAc shell: anterior +1.8 and +1.2, lateral +0.75, ventral −7.5. Dorsal striatum: anterior +1.8 and +1.0, lateral +2.6, ventral −4.2. Optic fiber implants were inserted above the ipsilateral VTA (for NAc injections) or SNc (for dorsal striatal injections) at the coordinates listed above.

Photometry

A mixture of AAVDJ-Ef1α-DIO-GCaMP6f and AAV9-hSyn-FLEX-ChrimsonR-tdTomato (0.5–1 μl of each, for a total volume of 1–2 μl per rat) was injected into the VTA (posterior −5.8, lateral +0.7, ventral −8.0) or SNc (posterior −5.3, lateral +2.4, ventral −7.4). Low-auto-fluorescence optic fibers (400 micron, Doric) were inserted just dorsal to the injection site at the same coordinates as above.

Optogenetic Stimulation

ChR2 studies utilized 473-nm lasers and ChrimsonR studies utilized 590-nm lasers (OptoEngine), adjusted to read ~10–20mW from the end of the patch cable at constant illumination. Light output during individual 5-ms light pulses during experiments was estimated to be ~2 mW/mm2 at the tip of the intracranial fiber. Light power was measured before and after every behavioral session to ensure that all equipment was functioning properly. For all optogenetic studies, optic tethers connecting rats to the rotary joint were sheathed in a lightweight armored jacket to prevent cable breakage and block visible light transmission.

Habituation and Optogenetic Pavlovian Training

Rats were first acclimated to the behavioral chambers (Med Associates), conditioning cues, and optic cable tethering in a ~30-min habituation session. During this session, rats were tethered to a rotary joint and 20 cue presentations, with no other consequences, were presented on a 90-s average variable time (VT) schedule. In each of 12 subsequent conditioning sessions, rats in paired groups were presented with 25 cue (light + tone, 7 s) – laser stimulation (100 5ms pulses at 20 Hz; laser train initiated 2 s after cue onset) pairings delivered on a 200-sec VT schedule. These cues were never associated with another external stimulus (e.g., food or water). Rats in unpaired groups also received 25 cue presentations and 25 laser trains per session, but an average 70-sec VT schedule separated these events in time. The duration of laser stimulation was chosen to mimic the multi-second dopamine neuron activation we observed in vivo when these subjects consumed natural reward, such as sucrose (Supplementary Fig. 5). An additional group of rats was given the same optogenetic Pavlovian training procedure described above for paired groups, but each laser stimulation was only 1 second long (20 5-ms pulses at 20 Hz, Fig. S4), delivered during the final second of each cue presentation. This group was included to confirm that brief dopamine neuron activation was sufficient to promote cue conditioned behavior. We also confirmed ex vivo that dopamine neurons could follow this stimulation pattern with light-evoked action potentials (Fig. 7; Supplementary Fig. 9). In all groups, cue and laser delivery were never contingent on an animal’s behavior and all rats received the same number of cue and laser events.

Conditioned Reinforcement

After optogenetic Pavlovian conditioning, rats were returned to the same behavioral chambers and tethered as before. At session onset, two levers were extended into the chamber below the cue lights used in the Pavlovian conditioning phase, and remained extended through the duration of the session. During 2 90-min sessions, presses on an active lever resulted in a 2-s presentation of the cue light-tone stimulus compound rats had received during Pavlovian training (fixed-ratio 1 schedule, with a timeout during each 2-s cue presentation), but no laser stimulation, to assess the conditioned reinforcing value of the cues alone. Inactive lever presses were recorded, but had no consequences.

Intracranial Self-Stimulation (2 1-hr sessions)

Rats were again returned to the behavioral chambers and tethered. During these sessions, nose poke ports were positioned on the wall opposite of the cue lights and levers from previous phases. During 2 1-hr sessions, pokes in the active port resulted in a 1-s laser train (20 Hz, 20 5-ms pulses, fixed-ratio 1 schedule with a 1-s timeout during each train), but no other external cue events, to assess the reinforcing value of stimulation itself. Inactive nose pokes were recorded, but had no consequences.

Video Scoring

Behavior during Pavlovian conditioning sessions was video recorded (Media Recorder 4.0, Noldus) using cameras positioned a standardized distance behind each chamber. Videos from sessions 1, 4, 8 and 12 were scored offline by observers who were blind to the identity and anatomical target group of the rats. Each cue (7-sec, 25 per session) and laser (1 or 5-sec, 25 per session) event was scored for the occurrence and onset latency of the following behaviors. Locomotion: Defined as the rat moving all four feet in a forward direction (i.e., not simply lifting feet in place). Cue Approach: Defined as the rat’s nose coming within 1 in of the cue light (trials in which the rat’s nose was in front of the light when it was presented were not counted in the approach measure). Approach often involved the rat moving from another area of the chamber to come in physical contact with the cue light while it was illuminated. Rearing: Defined as the rat lifting its head and front feet off the chamber floor, either onto the side of the chamber, or into the air. Rotation: Defined as the rat making a complete 360-degree turn in one direction.

Automated Motion Tracking and Analysis

We supplemented experimenter scored video analysis with automated behavior tracking, to provide a detailed quantitative assessment of cue-evoked movement patterns. Behavioral videos from the final session of Pavlovian conditioning were analyzed using Noldus Ethovision XT software to automatically track the position of the rats’ heads. The frame by frame location of the head within the video was transformed into a position coordinate within the experimental chamber. These coordinates were used to determine velocity (cm/s) and distance from the cue (cm) during pre-cue, cue, laser, and post-cue periods (Figs. 5 & Supplementary Fig. 8).

Ex vivo electrophysiology

5–6 weeks following virus injection (described above), rats were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane, decapitated, and brains were removed. 200 μM horizontal slices of the midbrain were cut in ice cold aCSF, then maintained at 33°C for current clamp recording as in previous studies 53. ChR2-expressing neurons were identified with epiflourescence on the recording scope (AxioExaminer A1, also equipped with infrared and Dodt optics, Zeiss). ChR2 was activated by transmitting 470-nm light generated by an LED (XR-E XLamp LED; Cree) coupled to a 200 μm fiber optic pointed at the recorded cell and powered by an LED driver (Mightex Systems) and triggered by a Master 8. Cells were filled with biocytin during the recording, and when the recording was complete, the slice was fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 4 hr. Immunocytochemistry was completed as in previous studies 53.

Fiber Photometry

Fiber photometry allows for real time excitation and detection of bulk fluorescence from genetically encoded calcium indicators, through the same optic fiber, in a freely moving animal. We first assessed dopamine neuron activity, via GCaMP6f fluorescence, in response to sucrose consumption, in order to determine the duration of activity during a reward exposure event, which we mimicked with optogenetic conditioning parameters. Rats underwent Pavlovian training wherein an auditory cue was presented on a 45-sec variable time schedule. VTA dopamine neurons in TH-cre+ rats (n=5) were transfected with GCaMP6f and implanted with optic fibers for photometry. Rats first received magazine training during which sucrose was periodically delivered into a reward port. We then conducted photometry recordings during sessions where sucrose was delivered to the port on a 45-sec VT schedule. We observed a rapid increase in fluorescence as animals consumed sucrose, lasting several seconds. These data show that natural reward consumption produces multi-second activation of dopamine neurons, at a comparable magnitude and duration, as measured by calcium fluorescence, to the 5-sec laser stimulation train we employed in optogenetic conditioning studies (Fig. S5).

To assess dopamine neuron activity during optogenetic Pavlovian conditioning, we co-transfected dopamine neurons were with GCaMP6f and ChrimsonR, a red-shifted excitatory opsin 54. This approach allowed for simultaneous measurement of activity-dependent fluorescence, excited by low power blue light, and optogenetic activation using orange light, in the same neurons 55. The photometry system was constructed similar to previous studies 40. A fluorescence mini-cube (Doric Lenses) transmitted light streams from a 465-nm LED sinusoidally modulated at 211 Hz that passed through a GFP excitation filter, and a 405-nm LED modulated at 531 Hz that passed through a 405-nm bandpass filter. LED power was set at ~100 microwatts. The mini-cube also transmitted light from a 590-nm laser, for optogenetic activation of ChrimsonR through the same low-autofluorescence fiber cable (400nm, 0.48 NA), which was connected to the optic fiber implant on the rat. GCaMP6f fluorescence from neurons below the fiber tip in the brain was transmitted via this same cable back to the mini-cube, where it was passed through a GFP emission filter, amplified, and focused onto a high sensitivity photoreceiver (Newport, Model 2151). Demodulation of the brightness produced by the 465-nm excitation, which stimulates calcium-dependent GCaMP6f fluorescence, versus isosbestic 405-nm excitation, which stimulates GCaMP6f in a calcium-independent manner, allowed for correction for bleaching and movement artifacts. A real-time signal processor (RP2.1, Tucker-Davis Technologies) running OpenEx software modulated the output of each LED and recorded photometry signals, which were sampled from the photodetector at 6.1 kHz. The signals generated by the two LEDs were demodulated and decimated to 382 Hz for recording to disk. For analysis, both signals were then downsampled to 40 Hz, and a least-squares linear fit was applied to the 405-nm signal, to align it to the 465-nm signal. This fitted 405-nm signal was used to normalize the 465-nm signal, where ΔF/F = (465-nm signal – fitted 405-nm signal)/(fitted 405-nm signal). Task events (e.g., cue and laser presentations), were time stamped in the photometry data file via a signal from the Med-PC behavioral program, and behavior was video recorded as described above.

Photometry rats (Cue Paired group, n=8) underwent opto-Pavlovian conditioning, similar to that described above, but the intertrial interval for these experiments was halved to 100-sec VT, for a ~40-min session length. This was done to shorten the overall length of photometry measurement periods to minimize photobleaching of GCaMP-expressing cells. Photometry measurements were made on training sessions 1, 4, 8, and 12, during which both LED channels were modulated continuously, as described above. On these 4 sessions, 20% of trials (5/25), pseudo-randomly presented, were “probes”, where cues were presented without accompanying optogenetic stimulation. Unpaired rats (n=5) received 12 sessions of cue and laser presentations (25 each) separated by a 70-sec VT.

Following conditioning, a subset of paired animals (n=5) received one session of extinction training, during which cues were presented as before, but laser was omitted, while photometry measurements were made.

For baseline characterization of ChrimsonR-activated GCaMP6f signals, rats (n=5) were tethered to the photometry apparatus, and continuous photometry measurements were made during a series of 60 unsignalled 590-nm laser presentations (30 trials of 1-sec, 20 Hz stimulation trains, 30 trials of 5-sec, 20 Hz trains, counterbalanced), delivered on a 30-sec VT schedule.

ChrimsonR ICSS

Th-cre+ rats (n=7) were given the opportunity to respond for 590-nm laser pulses (1 s, 20 Hz), in 2 1-hr sessions, similar to above, to validate ChrimsonR support of dopamine-mediated primary reinforcement. On a third session, the laser was switched from orange to blue (473-nm), to verify that ChrimsonR activation necessary to support behavior is specific to red-shifted light.

Statistics, Data Collection, and Analysis

Rats were randomly assigned to conditioning groups (paired, unpaired) following surgery. Behavioral data from optogenetic conditioning experiments was automatically recorded with Med-PC software (Med Associates) and analyzed using Prism 6.0. Video of conditioning sessions was recorded using Noldus Media Recorder 4.0, and automated behavior tracking data was generated using Noldus Ethovision XT and analyzed in MATLAB. For manual video scoring, experimenters were blind to the anatomical and conditioning group identify. Experimenters were otherwise not blinded. Non-parametric tests were used when data distributions were non-normal. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA was used to analyze changes in behavior among the groups across training. Bonferroni-corrected post hoc comparisons were made to compare groups on individual sessions. No statistical tests were used to predetermine sample sizes, but our sample sizes were similar to previously published studies. Rats were included in optogenetic behavioral analyses if optic fiber tips were no more than ~500 microns dorsal to the target region (VTA or SNc). Photometry data were collected with TDT OpenEx and Synapse software and analyzed using MATLAB. To assess the change in fluorescence across training days we fit a linear mixed-effect model for ΔF/F during each period of interest (0–1 s post-cue and laser omission period), with fixed effects for day and random effects for subject. To assess the relationship between the magnitude of cue-evoked fluorescence and CR latency, we fit a linear mixed-effect model for latency with fixed effects for cue-evoked fluorescence magnitude and random effects for subject. All comparisons were two tailed. Data in figures are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Please see the Life Sciences Reporting Summary for additional information.

Histology

Rats were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and transcardially perfused with cold phosphate buffered saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for ~24 hours, then cryoprotected in a 25% sucrose solution for at least 48 hours. Sections were cut at 50 microns on a cryostat (Leica Microsystems). To confirm viral expression and optic fiber placements, brain sections containing the midbrain were mounted on microscope slides and coverslipped with Vectashield containing DAPI counterstain. Fluorescence from ChR2-eYFP and ChrimsonR-tdTomato as well as optic fiber damage location was then visualized. Tissue from cre− animals was examined for lack of viral expression and optic fiber placements. To verify localization of viral expression in dopamine neurons we performed immunohistochemistry for tyrosine hydroxylase and GFP/tdTomato. Sections were washed in PBS and incubated with bovine serum albumin (BSA) and Triton X-100 (each 0.2%) for 20 min. 10% normal donkey serum (NDS) was added for a 30-min incubation, before primary antibody incubation (mouse anti-GFP, 1:1500, Invitrogen; rabbit anti-TH, 1:500, Fisher Scientific) overnight at 4°C in PBS with BSA and Triton X-100 (each 0.2%). Sections were then washed and incubated with 2% NDS in PBS for 10 minutes and secondary antibodies were added (1:200 Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse, 594 donkey anti-rabbit or 647 chicken anti-rabbit) for 2 hours at room temperature. Sections were washed 2 times in PBS and mounted with Vectashield containing DAPI. Brain sections were imaged with a Zeiss Axio 2 microscope.

For cell counting to quantify targeting specificity in TH-cre rats (Supplementary Fig. 1), the Apotome microscope function was used to take 20x 3-channel images along the medial-lateral and anterior-posterior gradients of the midbrain, using equivalent exposure and threshold settings. With the TH channel turned off, YFP+ cells were first identified by a clear ring around DAPI-stained nuclei. The TH channel was then overlaid, and the proportion of YFP+ cells co-expressing TH was counted. Cell counting for quantification of ChrimsonR and GCaMP6f expression overlap (Supplementary Fig. 5) was done as above. GCaMP6f+, ChrimsonR+, and TH+ cells directly below optic fiber placements were counted to determine the overlap of these three markers.

For assessing retrograde AAV expression (Supplementary Fig. 10), sections containing the striatum and midbrain from brains with AAV2/5-Ef1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-eYFP-WPRE-hGH injections targeting the NAc core (n=4), shell (n=5), or dorsal striatum (n=5) were processed with immunohistochemistry for YFP and TH, as above. Tiled images of whole sections (6–10 sections per rat) containing the midbrain were then taken at three approximate anatomical levels: −5.0, −5.5, and −6.0 mm posterior to bregma based on the Paxinos and Watson rat brain atlas. The topography of retrograde expression was estimated by drawing regions of interest (ROIs) around the area within each brain section containing YFP+ cell bodies. Individual brain slices containing these ROIs were then overlaid in Adobe Illustrator and aligned to standardized atlas plates for visualization of average expression patterns according to projection.

Supplementary Material

1

Supplementary Figure 1. Highly specific targeting of ChR2-eYFP to TH+ neurons in TH-cre rats. (a) Injection of a cre-dependent ChR2-eYFP AAV vector resulted in targeting of ChR2-eYFP to TH+ neurons in the (b) SNc and (c) VTA. (d) Targeting specificity was high (96.9%; 1027 TH+/1060 eYFP+ neurons counted) across medial/lateral and anterior/posterior sections of the midbrain.

Supplementary Figure 2. Optic fiber placements. Coronal plates showing the location of optic fiber tips relative to Bregma for TH-cre+ and cre− control rats in the (a) ChR2 experiments, (b) fiber photometry experiments, (c) ChrimsonR intracranial self-stimulation, and (d) Projection-specific ChR2 experiments.

Supplementary Figure 3. Acquisition of Pavlovian conditioned responses. (a) VTA and SNc cre+ paired rats learned conditioned responses during the cue period at the same rate (2-way repeated measures ANOVA, no interaction, F(3,42)=0.691, p=0.563). (b) Neither VTA nor SNc cre+ unpaired rats developed conditioned responses during the laser period. (c) Learning curves for individual rats in all groups during the cue period. (d) Learning curves for individual rats in all groups during the laser period. (e) The average cumulative probability of CR occurrence for VTA and SNc paired rats within 7-sec cue periods across training. VTA and SNc rats acquire CRs rapidly, and CRs emerged earlier in the cue period as training progressed. Data expressed as mean ± SEM.

Supplementary Figure 4. One-second laser optogenetic Pavlovian conditioning. (a) TH-cre+ rats (n=5; 3 SNc targeted, 2 VTA targeted) underwent optogenetic Pavlovian conditioning where they received 1-sec long laser presentations, delivered during the final 1 sec of each 7-sec cue. (b) Across training, these rats developed conditioned behavior (i.e., locomotion) in response to cue presentations, relative to unpaired controls, that did not differ in likelihood when compared with 5-sec laser paired conditioning groups (2-way repeated measures (RM) ANOVA, session X group interaction, F(2,32)=66.44, p<0.0001; post hoc comparisons with paired and unpaired groups). (c) The onset latency of conditioned behavior during cue presentations decreased across training for 1 and 5-sec paired stimulation groups (main effect of session F(1,19)=60.96, p<0.0001; no effect of stimulation group, F(1,19)=.0446, p=.835). Data expressed as mean ± SEM. ***p< 0.0001.

Supplementary Figure 5. Fiber photometry validation and analysis. (a) AAVs containing cre-driven GCaMP6f and ChrimsonR were co-injected into the midbrain in TH-cre rats. (b and c) This led high GCaMP6/ChrimsonR co-expression and specificity to TH+ neurons within the recording area below optic fiber placements. (d) Delivery of 20 or 100 5-ms 590-nm laser light pulses resulted in rapid increases in GCaMP6f fluorescence (depicted as ΔF/F, the change in fluorescence during the stimulation period over baseline, n = 5 rats) that showed stable peak levels, and rapid offset. (e) Intracranial self-stimulation was used to assess the effectiveness of ChrimsonR activ ation to support behavior. (f) ChrimsonR activation via 590-nm laser delivery to dopamine neurons in the midbrain supported robust self-stimulation behavior (n=7), measured as nose pokes, that rapidly extinguished when a 473-nm laser was substituted (2-way repeated measures ANOVA, session X response type interaction, F(2,12)=37.27, p<0.0001; post hoc comparisons with inactive responses). (g) Optogenetic activation of dopamine neurons was compared to activation produced by sucrose (n=5). Delivery of 100 5-ms 590-nm laser pulses produced an overall pattern and duration of increased fluorescence that was similar to that produced by consumption of 0.1 ml of a 10% sucrose solution. (h) Example whole session trace of the demodulated 465-nm LED signal. (i) Example whole session trace of the demodulated 405-nm LED signal. (j) Trace shown in (i) after applying a least-squares fit. (k) Normalized 465 signal (ΔF/F) = (465-nm signal – fitted 405-nm signal)/(fitted 405-nm signal). Laser-evoked fluorescence is denoted by the orange bars. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. ***p< 0.0001.

Supplementary Figure 6. Acquisition of conditioned approach for individual rats. VTA cre+ paired rats developed (a) cue approach conditioned behavior, relative to cre+ unpaired and cre− control groups. (b) No SNc cre+ paired rats developed cue approach.

Supplementary Figure 7. Proximity to cue location at cue onset and stimulation hemisphere are not related to behavioral results. (a) The location of each rat in the experimental chamber was recorded at the onset of each cue presentation. The average location at cue onset across training was determined by assigning a value of “1” to a trial if the rat was located on the side of the chamber containing the cue light, or a value of “2” to a trial if the rat was located in the back half of the chamber at cue onset. (b) The average location at cue onset for cre+ paired VTA and SNC rats did not differ, nor did it change across training (2-way RM ANOVA, no effect of group, F(1,14)=3.178, p=0.0963; no interaction, F(3,42)=0.706, p=0.554). (c–f) The probability of locomotion, approach, and rotation during cue presentations did not differ across rats depending on the hemisphere in which they received optogenetic stimulation. Data expressed as mean ± SEM.

Supplementary Figure 8. Movement tracking Examples. (a) Behavioral videos were recorded during optogenetic Pavlovian conditioning. (b–e) Videos from the final day of conditioning were analyzed using Ethovision software to localize the frame-by-frame position of each rat’s head within the experimental chambers. Depicted are screenshots of an example rat from each experimental group, superimposed with the behavior tracking data for three cue-laser trials for that subject. Rats in the paired groups exhibited movement during the cue period (cue directed for the VTA rats, rotational for the SNc rats), while unpaired rats were immobile.

Supplementary Fig. 9. Similar light-evoked responses in ventral and dorsal striatal projecting dopamine neurons. (a) Among quiescent neurons, both NAc projectors and DS projectors showed high fidelity up to 50-Hz stimulation. Fidelity was observed in response to both 1-ms and 5-ms pulse trains. Each marker represents a cell, but some cells were tested with more than one frequency. (b) Summary of the locations of the recorded neurons in the horizontal slice. DS projectors were localized in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and NAc projectors were located in the VTA. (c) Example recording in a ChR2 expressing VTA neuron that was also firing spontaneously during recording. Although the LED light stimulation did increase the firing rate of the cell (lower panel), the increase in firing was not due to AP firing time-locked to the light pulses (upper panel). (d) Example spontaneous firing in the same cell, without light stimulation. (e) Summary of the impact of light pulses on spontaneously firing, ChR2 expressing neurons. While fidelity was moderate, stimulation did increase the firing rate in these cells.

Supplementary Figure 10. Retrograde targeting of dopamine neurons reveals projection-specific expression patterns in the midbrain. (a) Transfection in striatum of TH-cre rats with a retrogradely-transported DIO-ChR2-eYFP construct resulted in robust expression of ChR2-eYFP in TH+ cells in the midbrain, but the expression pattern varied according to striatal target. (b) Summary of expression patterns for NAc shell (n=5 rats, 6–10 slices per rat), NAc core (n=4), and dorsal striatum (n=5) projecting dopamine neurons. Shell projections were concentrated in the ventromedial VTA, while core projections were concentrated in the laterodorsal VTA. Projections to the dorsal striatum were localized throughout the SNc.

Supplementary Video 1 | Cue approach in a VTA cre+ paired rat. Red indicator light (Bottom of frame) signifies cue period. Yellow indicator light signifies laser period. Behavior is initiated after cue onset, but before laser onset.

Supplementary Video 2 | Cue presentation for a cre+ unpaired rat. Red indicator light (Bottom of frame) signifies cue period.

Supplementary Video 3 | Laser delivery for a cre+ unpaired rat. Yellow indicator light (bottom of frame) signifies laser period.

Supplementary Video 4 | Cue presentation for a cre− paired rat. Red indicator light (Bottom of frame) signifies cue period. Yellow indicator light signifies laser period.

Supplementary Video 5 | Cue-evoked rotation in an SNc cre+ paired rat. Red indicator light (Bottom of frame) signifies cue period. Yellow indicator light signifies laser period. Behavior is initiated after cue onset, but before laser onset.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Keiflin and all members of the Janak laboratory for discussion and comments on the manuscript; A. Haimbaugh, D. Acs, H. Pribut, K. Lineback, N. Pettas, B. Persaud, and L. Kinny for assistance with histology and behavioral video scoring; P. Fong for conducting surgical procedures for ex vivo physiology studies; K. Deisseroth (Stanford) for the ChR2 construct; E. Boyden (MIT) for the ChrimsonR construct; and the Janelia Research Campus GENIE Project and Stanford Gene Vector and Virus Core for the GCaMP6f construct. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DA036996 (BTS), DA042895 (BTS), AA022290 (JMR), AA025384 (JMR), DA030529 (EBM), and DA035943 (PHJ), as well as grants from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (BTS and JMR).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: BTS and PHJ designed the experiments. BTS collected and analyzed data from ChR2 experiments. BTS and JMR collected and analyzed the photometry data. EBM collected and analyzed the ex vivo physiology data. BTS and PHJ wrote the manuscript with input from all the authors.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Competing Interests: The authors have no conflicts to declare.

Code Availability: All MATLAB code used in analysis of these findings is available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Data Availability: The data supporting these findings are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0191-4

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc6082399?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Dopamine release plateau and outcome signals in dorsal striatum contrast with classic reinforcement learning formulations.

Nat Commun, 15(1):8856, 14 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39402067 | PMCID: PMC11473536

Dopamine neurons encode trial-by-trial subjective reward value in an auction-like task.

Nat Commun, 15(1):8138, 17 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39289338 | PMCID: PMC11408490

Dopamine Release in the Nucleus Accumbens Core Encodes the General Excitatory Components of Learning.

J Neurosci, 44(35):e0120242024, 28 Aug 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38969504

Distinct dynamics and intrinsic properties in ventral tegmental area populations mediate reward association and motivation.

Cell Rep, 43(9):114668, 27 Aug 2024

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 39207900 | PMCID: PMC11514737

Distinct cholinergic circuits underlie discrete effects of reward on attention.

Front Mol Neurosci, 17:1429316, 29 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39268248 | PMCID: PMC11390659

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (165) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Dopamine neurons drive spatiotemporally heterogeneous striatal dopamine signals during learning.

Curr Biol, 34(14):3086-3101.e4, 25 Jun 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38925117

Neurons of the Ventral Tegmental Area Encode Individual Differences in Motivational "Wanting" for Reward Cues.

J Neurosci, 40(46):8951-8963, 12 Oct 2020

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 33046552 | PMCID: PMC7659453

Cue and Reward Evoked Dopamine Activity Is Necessary for Maintaining Learned Pavlovian Associations.

J Neurosci, 41(23):5004-5014, 22 Apr 2021

Cited by: 10 articles | PMID: 33888609 | PMCID: PMC8197637

Dissecting the diversity of midbrain dopamine neurons.

Trends Neurosci, 36(6):336-342, 12 Apr 2013

Cited by: 214 articles | PMID: 23582338

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIAAA NIH HHS (4)

Grant ID: F32 AA022290

Grant ID: P50 AA017072

Grant ID: K99 AA025384