Abstract

Objectives

Gynecologic malignancies are the leading cause of cancer death among women in Botswana. Twenty-five percent of cervical cancers present at a stage that could be surgically cured; however, there are no gynecologic oncologists to provide radical surgeries. A sustainable model for delivery of advanced surgery is essential to advance treatment for gynecologic malignancies.Methods/materials

A model was developed to provide gynecologic oncology surgery in Botswana, delivered by US-based gynecologic oncologists in four 2-week blocks per year. A pilot gynecologic oncology campaign was planned at a district hospital. Eligible patients were identified through the gynecologic oncology multidisciplinary clinic at the regional referral hospital, where gynecologic oncology treatment planning is provided. Local providers were invited to participate to build local surgical capacity.Results

One US-based gynecologic oncologist, 2 gynecologists, and 2 surgeons working in Botswana participated in the pilot campaign. Sixteen operations were performed over 7 days. Indications included cervical cancer (4), ovarian cancer (3), vulvar cancer (1), complex atypical hyperplasia (1), pre-invasive cervical disease (2), and benign disease (3), as well as 2 obstetric emergencies. The only gynecologic oncology complication was a case of bleeding requiring transfusion and postoperative intensive care unit admission. Follow-up care was coordinated through the gynecologic oncology multidisciplinary clinic.Conclusions

Periodic gynecologic oncology campaigns in settings otherwise lacking local capacity to perform advanced surgery are a feasible model to create access and build local capacity. Strong local collaboration is essential. Future strategies to increase impact include recruitment of more gynecologic oncologists to increase service and training availability.Free full text

Pilot of an International Collaboration to Build Capacity to Provide Gynecologic Oncology Surgery in Botswana

Abstract

Objectives

Gynecologic malignancies are the leading cause of cancer death among women in Botswana. Twenty-five percent of cervical cancers present at a stage that could be surgically cured; however, there are no gynecologic oncologists to provide radical surgeries. A sustainable model for delivery of advanced surgery is essential to advance treatment for gynecologic malignancies.

Methods/Materials

A model was developed to provide gynecologic oncology surgery in Botswana, delivered by US-based gynecologic oncologists in four 2-week blocks per year. A pilot gynecologic oncology campaign was planned at a district hospital. Eligible patients were identified through the gynecologic oncology multidisciplinary clinic at the regional referral hospital, where gynecologic oncology treatment planning is provided. Local providers were invited to participate to build local surgical capacity.

Results

One US-based gynecologic oncologist, 2 gynecologists, and 2 surgeons working in Botswana participated in the pilot campaign. Sixteen operations were performed over 7 days. Indications included cervical cancer (4), ovarian cancer (3), vulvar cancer (1), complex atypical hyperplasia (1), pre-invasive cervical disease (2), and benign disease (3), as well as 2 obstetric emergencies. The only gynecologic oncology complication was a case of bleeding requiring transfusion and postoperative intensive care unit admission. Follow-up care was coordinated through the gynecologic oncology multidisciplinary clinic.

Conclusions

Periodic gynecologic oncology campaigns in settings otherwise lacking local capacity to perform advanced surgery are a feasible model to create access and build local capacity. Strong local collaboration is essential. Future strategies to increase impact include recruitment of more gynecologic oncologists to increase service and training availability.

The global burden of gynecologic malignancies falls disproportionately on low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where dedicated resources and access to care are limited.1 Disparity in gynecologic malignancies is most profound for cervical cancer (CA); 85% of CA cases and deaths occur in LMICs.2,3 Although CA is the fourth leading cause of cancer in women worldwide, it is the leading cause of cancer death in women in sub-Saharan Africa.4 The same is true in Botswana, where the disease burden is impacted by the high prevalence of HIV (22% among people aged 15–49 years), a well-established risk factor for CA.5–7 The incidence of other gynecologic malignancies are increasingly being recognized. In Botswana, CA accounts for 25% of all female cancer cases, followed by vulvar, ovarian, and endometrial CA.8

Although advances in CA screening have been made possible in sub-Saharan Africa through public health programming, advances in management of established gynecologic malignancies have lagged.9 In recent years, growing data have revealed high rates of unmet surgical need throughout sub-Saharan Africa, particularly with regard to capacity to manage malignant conditions.10,11 Adequate management of gynecologic malignancies requires advanced surgical training. Data show that gynecologic oncologists performing surgery for gynecologic malignancies achieve better surgical outcomes and improved survival compared with gynecologists and general surgeons.12,13 Surgical training needs to be bolstered by infrastructural capacity to manage complex perioperative care, chemotherapy, and radiation.14

In Botswana, approximately 25% of women with CA present at a stage that could be cured by radical surgery alone yet there are no trained gynecologic oncologists to provide these surgeries. Chemotherapy and radiation are available as alternatives; however, these present additional challenges. Whereas both surgery and chemoradiation present risks, there are significant toxicities associated with chemoradiation especially in younger women.15 In addition, even in Botswana where citizens are provided free treatment, the logistics of transportation to radiotherapy centers, staff training, fidelity to treatment protocol, maintenance of equipment, and pipelines of chemotherapeutic agents are all challenges to completing treatment without delay.16,17

In Botswana, there are no gynecologic oncologists to provide radical hysterectomies and there is extremely limited access to advanced procedures to accurately stage vulvar, endometrial, and ovarian cancer, such as inguinal, pelvic, and para-aortic lymph node dissections. The primary goals of the collaboration were (1) to improve the surgical standard of care for treatment of gynecologic malignancies and (2) to help develop training programs locally and build local capacity in gynecological oncology. Here, we present an implementation pilot for a model of gynecologic oncology services and training in advanced surgical procedures of practitioners working locally.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

National Gynecologic Cancer Context

Gynecologic oncology care in Botswana is coordinated by a gynecologic oncology multidisciplinary team clinic (MDT) at Princess Marina Hospital (PMH), which is located in Gaborone, the capital of Botswana, and is the regional referral center for management of gynecologic malignancies. Patients are referred either preoperatively, for multidisciplinary planning of appropriate treatment, or postoperatively for further treatment planning of a surgically staged malignancy. Patients can be prescribed surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy from PMH MDT depending on the disease and stage of disease. Chemotherapy is available within the public health system in Botswana. Radiation is provided to all citizens without personal cost at a private hospital in Gaborone.

In terms of surgical services, general gynecologists are the sole providers of gynecologic oncology surgery in Botswana. There are very few providers capable of performing abdominopelvic and inguinal lymphadenectomy and no providers in the public sector who provide radical hysterectomies. There is currently no residency-training program in obstetrics and gynecology (OBGYN) in Botswana.

Pathology is available at the national health laboratory and all surgical specimens from the southern region in Botswana are sent for pathologic evaluation. Pathology review takes approximately 4 weeks.

Developing a Partnership

Working through the Botswana Harvard AIDS Initiative Partnership, the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston supports a full-time gynecologist at Scottish Livingstone Hospital (SLH), a district hospital in Molepolole, Botswana. Members of the Division of Gynecologic Oncology of BIDMC made 3 separate visits to evaluate the surgical and clinical capacity to provide advanced gynecologic surgery and meet with local partners.

In collaboration with the Ministry of Health and Wellness (MOHW), a model was developed to provide 8 weeks per year of gynecologic oncology services in Botswana, in four 2-week blocks, delivered by US-based gynecologic oncologists. A pilot 2-week gynecologic oncology campaign was planned at SLH, which has experience running surgical campaigns in other fields. The BIDMC’s Division of Gynecologic Oncology committed to fund costs related to international and in-country travel, as well as the faculty’s salary while working in Botswana. The MOHW committed to providing a clinical site for the campaign and procuring essential surgical equipment and supplies necessary for implementation of a successful campaign.

Site Preparation

Scottish Livingstone Hospital is a 350-bed district hospital approximately 1 hour from Gaborone. It has 2 functional operating rooms where general surgery and OBGYN operate on a daily basis. The hospital has a blood bank on site, preoperative cross-matching is performed, emergency cross-matching and release of blood usually take approximately 1 hour, and emergency noncross-matched blood can be released more quickly. There is a laboratory on site that can typically run urgent specimens within 2 hours, although arterial blood gas machines are available for quick estimates of hemoglobin and chemistries. There is an intensive care unit with 6 beds and 4 ventilators.

Coordinated weekly meetings were held during the 3 months before the campaign with involved hospital departments, including pharmacy, supplies, maintenance, biomedical engineering, nursing, anesthesia, theater, and intensive care, to ensure that essential equipment, supplies, medications, and staffing were prepared.

General gynecologists and surgeons working in Botswana were invited to participate in gynecologic oncology surgeries to build local surgical capacity.

Coordination of Care

Eligible patients were identified through PMH MDT. After identification by the referral hospital, all patients had preoperative evaluations by a general gynecologist at the district hospital. The operating gynecologic oncologist evaluated all surgical candidates on the first day of the campaign and surgery began the following day. The general gynecologist at the district hospital saw all patients at 2 and 6 weeks postoperatively and referred back to PMH MDT for chemotherapy and radiation as indicated.

RESULTS

The surgical campaign took place from August 14–24, 2017. One US-based gynecologic oncologist from BIDMC provided the surgical expertise. Two gynecologists and two surgeons working in Botswana participated in the pilot campaign.

Eight patients were referred from PMH MDT and 7 were deemed surgical candidates. One patient with CA was examined by the gynecologic oncologist and assessed as CA stage 1B2 disease, and the patient was referred back to PMH MDT for chemoradiation. Additional patients with preinvasive and benign disease were added to the surgical schedule so that the campaign would operate at full capacity. In addition, 2 emergency obstetric cases were done by the general gynecologist and assisted by the gynecologic oncologist. Sixteen operations were performed over 7 days. One day of operating was cancelled because of anesthesia equipment malfunctioning.

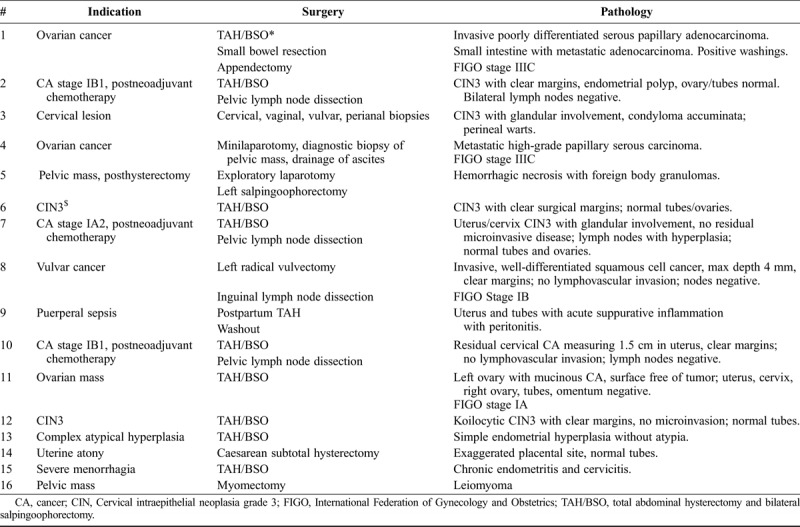

Indications for surgery included CA (4), ovarian cancer (3), vulvar cancer (1), complex atypical hyperplasia (1), preinvasive cervical disease (2), and benign disease (3), as well as 2 obstetric emergencies (Table (Table1).1). The only gynecologic oncology complication was a case of bleeding requiring transfusion and postoperative intensive care unit admission.

TABLE 1

Surgical case list for pilot gynecologic oncology campaign

Success of the campaign included: comprehensive coordination of care across institutions, development of systems for preoperative anesthesia evaluation, preoperative preparation of cross-matched blood, and institution of preoperative antibiotic administration. Challenges encountered included the following: equipment failure in the on-site intensive care unit resulting in transfer of a postoperative patient to an outside facility, lack of anesthetic gas causing 1 day of surgery to be cancelled, and lack of specialized equipment such as self-retaining abdominal retractors, acutely curved clamps, and vein retractors, which made fine dissections challenging.

DISCUSSION

Periodic gynecologic oncology campaigns in settings otherwise lacking local capacity to perform advanced gynecologic oncology surgery may be a feasible model to create access to standard-of-care treatment and build local capacity in LMICs otherwise lacking subspecialty care. Strong local collaboration is essential, particularly with the referral providers, hospital administration, and the MOHW. This pilot proved to be an effective way for women in Botswana to gain access to standard-of-care gynecologic oncology surgery, with minimal cost to the MOHW, albeit with financial contributions of other partners. Visiting gynecologic oncologists found the work rewarding, because it allowed them to meaningfully contribute to global cancer care in a sustainable way.

This type of partnership may be feasible in other, similarly resourced settings. It may be particularly impactful in places where there is already an OBGYN residency-training program. The larger goal of this particular collaboration is to contribute to the clinical capacitation of trainees and practitioners in Botswana. To that aim, a primary goal for the next campaign will be to increase participation of local gynecologists and surgeons to build existing capacity locally. Beyond this, however, we hope to have laid a foundation for an ongoing exchange of subspecialists into Botswana who can contribute to the development of an independent residency-training program in OBGYN in Botswana.

In 2016, the International Committee of the Society for Gynecologic Oncology called for their society members to take an active role in providing specialist service and education to resource-limited areas.18 Several partnerships exist to support training in radical surgery and several fellowships in gynecologic oncology have been started in LMICs.19–23 Existing collaborations have had similar emphases on curriculum and skill transfer, but each has developed in-line with its own resource context. The results of these training programs in terms of impact on care are starting to be demonstrated.24

We have, however, recognized several challenges during our pilot. The time lag between diagnosis of a gynecologic malignancy and periodic surgical campaigns remains an issue. Increasing the frequency of gynecologic oncology visits would allow advanced surgical planning to be incorporated into routine clinical services. For this to work, there needs to be commitments from partners, to increase recruitment of additional gynecologic oncology faculty and thus increase clinical service and training availability, and support from MOHW to provide facilities, supplies, and staffing to support the campaign. To this end, we have engaged gynecologic oncology professional societies to increase recruitment of faculty.

Another challenge is balancing the aggressiveness of surgery appropriate for the setting. For instance, we encountered delays in preparation of blood products for the 1 gynecologic oncology case requiring transfusion with multiple products, during which time the status of the patient was uncertain. Postoperatively with the same patient, we encountered equipment failures in our own intensive care unit and consequently the patient had to be transferred to an outside hospital for the duration of her intensive care unit stay. Although these were frustrating challenges requiring improvisation in the moment, the patient recovered quite rapidly and did very well postoperatively. This leaves us with the question of what risk is acceptable to provide extraordinary services in our setting? MD Anderson and their international collaboration in Latin America have described similar challenges.25 Ongoing research in alternative treatment methods and conservative therapy may provide evidence for alternative but equally effective treatment plans for LMICs.26,27

It seems obvious that increasing access to gynecologic oncology surgery will improve care and survival for the world’s most vulnerable women, but evaluating impact is a priority. To this end, a baseline evaluation of the unmet gynecologic oncology surgical need in Botswana is underway. Demonstration of the efficacy of our programming will allow limited funding to be allocated and used to its maximal benefit.

In summary, a gynecological oncology partnership through regular short campaigns is feasible with strong local collaboration to deliver quality surgical care in settings where no gynecological oncologists are available. This type of partnership may be feasible in other limited resource settings and could set the stage for building local surgical capacity.

HIGHLIGHTS

Gynecologic oncology campaigns may be a feasible model to create access to standard-of-care cancer treatment in LMICs

Periodic campaigns could strengthen local surgical capacity in LMICs otherwise lacking advanced training programs

Working through existing collaborations allows gynecologic oncologists to contribute to sustainable global cancer care

Footnotes

Gynecologic oncology campaigns may be a feasible model to create access to standard-of-care cancer treatment in low- and middle-income countries. Periodic campaigns could strengthen local surgical capacity in low- and middle-income countries otherwise lacking advanced training programs. Working through existing collaborations allows gynecologic oncologists to contribute to sustainable global cancer care.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1097/igc.0000000000001372

Article citations

Cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: a Lancet Oncology Commission.

Lancet Oncol, 23(6):e251-e312, 09 May 2022

Cited by: 77 articles | PMID: 35550267 | PMCID: PMC9393090

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and less invasive surgery for the management of early stage cervical cancer: A brief report from Botswana.

Gynecol Oncol Rep, 42:101032, 22 Jun 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 35782102 | PMCID: PMC9240358

Vulvar cancer in Botswana in women with and without HIV infection: patterns of treatment and survival outcomes.

Int J Gynecol Cancer, 31(10):1328-1334, 07 Sep 2021

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 34493586 | PMCID: PMC8675890

Gynecologic Oncology Sub-Specialty Training in Ghana: A Model for Sustainable Impact on Gynecologic Cancer Care in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Front Public Health, 8:603391, 03 Dec 2020

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 33344404 | PMCID: PMC7744480

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Maintaining surgical care delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparative cohort study at a tertiary gynecological cancer centre.

Gynecol Oncol, 160(3):649-654, 16 Dec 2020

Cited by: 14 articles | PMID: 33358197 | PMCID: PMC7831534

Perspectives of Gynecologic Oncologists on Minimally Invasive Surgery During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Turkish Society of Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Oncology (MIJOD) Survey.

Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 23(2):573-581, 01 Feb 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 35225470 | PMCID: PMC9272609

Mapping of Radiation Oncology and Gynecologic Oncology Services Available to Treat the Growing Burden of Cervical Cancer in Africa.

Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 118(3):595-604, 18 Nov 2023

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 37979709

Gynecologic Oncology Sub-Specialty Training in Ghana: A Model for Sustainable Impact on Gynecologic Cancer Care in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Front Public Health, 8:603391, 03 Dec 2020

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 33344404 | PMCID: PMC7744480

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

¶

¶