Abstract

Free full text

Prevalence and Correlates of Psychological Distress among Retired Elite Athletes: A Systematic Review

Abstract

This article presents results of a systematic review of the literature (2000–2017) examining the prevalence and correlates of psychological distress among retired elite athletes. Forty articles were selected and included. Our review suggests the prevalence of psychological distress among retired athletes is similar to that found in the general population. However, subgroups reporting medical comorbidities, significant pain, a greater number of concussions, less social support, and adverse psychosocial factors were at greater risk for psychological distress. Additionally, athletes experiencing psychological distress in retirement often do not seek treatment for their distress. Based on the existing literature, there is a need for greater standardization and use of reliable measures, as well as use of diagnostic interviews in order to assess the most accurate prevalence of psychological distress among these athletes. Longitudinal designs, matched control groups, more heterogeneous samples, and use of multivariate analyses would also help to more accurately determine the prevalence and risk factors of psychological distress in this population. This review suggests a number of different clinical implications and highlights directions for future research to enhance our understanding of the long-term psychological health of former elite athletes.

Introduction

Career termination can have a behavioral and emotional impact on the lives of retired elite athletes, consequently impairing future occupational and social functioning in these individuals (Ogilvie & Taylor, 1993; Stephan, 2003; Taylor & Ogilvie, 1994). Athletic retirement is defined as ‘the process from transition from participation in competitive sport to another activity or set of activities’ (Coakley, 1983). Retirement from elite sports is a revelatory event accompanied by a process of physical, social, and occupational transitions (Kim & Moen, 2001; Lavallee, Gordon, & Grove, 1997). Completing one’s career and starting anew transforms an individual’s previously established roles to new roles that are less familiar. Consequently, the transformation of athletes during the process following retirement from sports may negatively affect how they perceive themselves, their attributes, and their quality of life (Werthner & Orlick, 1986). Athletic goals are set throughout an athlete’s career, and accomplishing these goals influences how they view themselves (Stambulova, 2001; Werthner & Orlick, 1986). At the end of their careers, athletic-based goals are no longer necessary, and the transition becomes difficult because sports achievement has, in many cases, contributed to their feelings of subjective well-being during most of their life (Kim & Moen, 2001).

Retiring athletes’ experiences when transitioning out of competitive sports vary. Retirement transition types have been previously grouped into two clusters, normative and non-normative (Schlossberg, 1995). Normative transitions describe anticipated retirement, which can be influenced by factors such as graduation, older age, and gradual decline in performance. However, non-normative transitions are often the result of unexpected or forced retirement. In elite athletics, this frequently results from events such as a career-ending injury. These non-normative factors have been associated with worse post-career outcomes for retired elite athletes (Brown et al., 2017).

Taylor and Ogilvie (1994) proposed the Conceptual Model of Adaption to career transition, which provides a theoretical framework for the transition process of elite athletes. Taylor and Ogilvie noted that reasons for retirement, factors related to the quality of the transition, quality of the resources available for transitioning athletes, and the interventions used to assist athletes during their transition period are all associated with an athlete’s subjective well-being following retirement. Coakley (2006) reviewed this conceptual model in a sample of retiring National Football League (NFL) players, and noted that many of these athletes experienced negative subjective well-being during their retirement transition. A systematic review by Park, Lavallee, & Tod (2013) found that 16% of transitioning athletes experienced adjustment difficulties following career termination, including negative emotions such as grief and distress, as well as loss of identity.

The acute post-retirement phase can be stressful for many athletes, but studies have reported significant positive relationships between the length of time following retirement and the quality of subjective well-being in former athletes. Five studies utilizing longitudinal designs have shown that retired athletes tend to report higher life satisfaction over time (Douglas & Carless, 2009; Lally, 2007; McKenna & Thomas, 2007; Stephan, 2003; Wippert & Wippert, 2008). Former athletes reported significantly less life stress three months after retirement compared to ten days post retirement (Wippert & Wippert, 2008). Improved subjective well-being was also reported eighteen months after retiring (Douglas & Carless, 2009; McKenna & Thomas, 2007), indicating the negative effects of retirement may not persist indefinitely in all retirees. Similarly, in a study examining the retirement distress of 36 Olympic athletes, Stephan (2003) reported that athletes begin to develop new roles and identities approximately one year after sports termination. Within this process, four distinct periods of subjective well-being during transition were identified: 1) an initial decrease immediately following retirement, 2) an increase five months after retirement, 3) stabilization after eight months, and 4) a final increase in subjective well-being one year after retirement (Stephan, 2003). However, more recent investigations have identified influential predictors and modifiers of psychological functioning among retired elite athletes. Specifically, factors related to a career in competitive sports may influence psychological function in later adulthood. Thus, psychological distress may ultimately manifest later in retirement and not necessarily follow the described linear transition paths as evidenced by the aforementioned studies.

Current Study

Despite a wealth of literature examining various aspects of the retirement process in elite athletes, the proportion of this population who experience psychological distress (i.e., elevated unpleasant feelings or emotions related to conditions such as depression, anxiety, and substance misuse that impact physical, social, or occupational functioning) later in life remains unclear. Over the last decade, multiple peer-reviewed articles have shed light on the prevalence and correlates of psychological distress among former elite athletes. However, to the author’s knowledge, a review has yet to synthesize this body of literature and clarify the scientific findings. Therefore, the purpose of this review is two-fold: 1) describe the prevalence of psychological distress amongst retired elite athletes, and 2) identify correlates and risk factors of psychological distress in later adulthood.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature examining the prevalence and correlates of psychological distress among former elite athletes was conducted adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). The term “elite” has been previously used to describe athletes participating at varying levels of sports competition (Swann, Moran, & Piggott, 2015). This particular review relied on the definition of elite athletes provided by the Dictionary of Modern Medicine: “a person who is currently or has previously competed as a varsity player (individual or team), or a professional player or national team/international level player” (Segen, 2012). Thus, we examined the prevalence and correlates of psychological distress in former athletes that participated in organized sports at either the collegiate or professional level for at least one year. In order to help identify the potential antecedents of late-life psychological distress, this review included studies examining the psychological functioning of athletes beyond the proposed time of transition from athletic career to life without competitive sports (Douglas & Carless, 2009; Lally, 2007; McKenna & Thomas, 2007; Stephan, 2003; Wippert & Wippert, 2008, 2010). To further clarify, studies assessing psychological functioning of former elite athletes who have been retired for an average of at least two years were reviewed. If studies did not report the average number of years of retirement, studies examining the psychological functioning of samples with an average age of 40 and older were also included in the review (Arthur, 2016; Hadavi, 2011).

Search Method and Article Criteria

The search included empirical studies published through May, 2017 that reported on the prevalence and correlates of psychological distress in former elite athletes. Searches were performed by an experienced medical librarian and search strategies were reviewed for appropriateness and comprehensiveness by librarian colleagues. Multiple bibliographic databases were searched in order to cover medical, psychological, behavioral science, and sports medicine literature. A total of four databases were searched: PsycINFO® (1887-), PubMed/MEDLINE® (late 1940’s-), SPORTDiscus™ with Full Text (1930-), and Web of Science™ (1864-). Key search terms included: “retired athlete”, “former athlete” “mood disorders”, “depression”, “anxiety disorders”, “panic attacks”, “panic disorder”, “substance-related disorders”, “substance abuse”, “alcoholism”, and “post-traumatic stress disorder.” Relevant terms from controlled vocabularies were used where available, such as MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) for PubMed, and Thesaurus terms for PsycINFO and SPORTDiscus. In addition to subject headings, combinations of text words (i.e., keywords) were used and supplemented with relevant search features including phrase searching and truncation. A sample search for PubMed was:

(“Substance-Related Disorders”[Mesh]) OR (“Anxiety Disorders”[Mesh]) OR (“Mood Disorders”[Mesh]) OR (“Trauma and Stressor Related Disorders”[Mesh]) OR (“Disruptive, Impulse Control, and Conduct Disorders”[Mesh] OR depression OR anxiety OR “anxiety disorder” OR “post-traumatic stress disorder” OR PTSD OR panic OR “panic attack*” OR “panic disorder*” OR “substance abuse” OR “substance misuse” OR “substance addiction” OR alcoholism OR “alcohol addiction” OR addiction) AND (“retired athletes” OR “retired athlete” OR “former athlete” OR “former athletes”)

Results from each database were combined and duplicate references were removed prior to the initial abstract level screening. Abstracts were included in the full-text review if they reported on the prevalence or correlates of psychological distress among retired athletes. Once non-relevant articles were removed at the abstract level screening, the full text of each article was reviewed by two authors to ensure it met criteria based on evaluation using various traditional markers of study rigor. Evaluation criteria included: 1) English language, 2) published in peer-reviewed journals, and 3) quantitative studies. The authors chose the exclusive use of quantitative studies to best assess for prevalence of psychological distress. Including only quantitative studies allowed us to include investigations using statistical analyses to assess for correlates of psychological distress, as well as to interpret strengths and limitations of findings based on the described analytical methods. Articles were further specified to only include validated measures, such that they were empirically supported screeners or diagnostic measures of psychological functioning. In instances of non-agreement, the two authors discussed the article and either delivered a mutually agreed-upon decision or sought out a third author to break the tie. These authors also examined the references of each paper for any additional manuscripts that may have been overlooked by the original search. Once the results were compiled, the lead authors and senior author met to evaluate the findings and assess the thoroughness of the reported results.

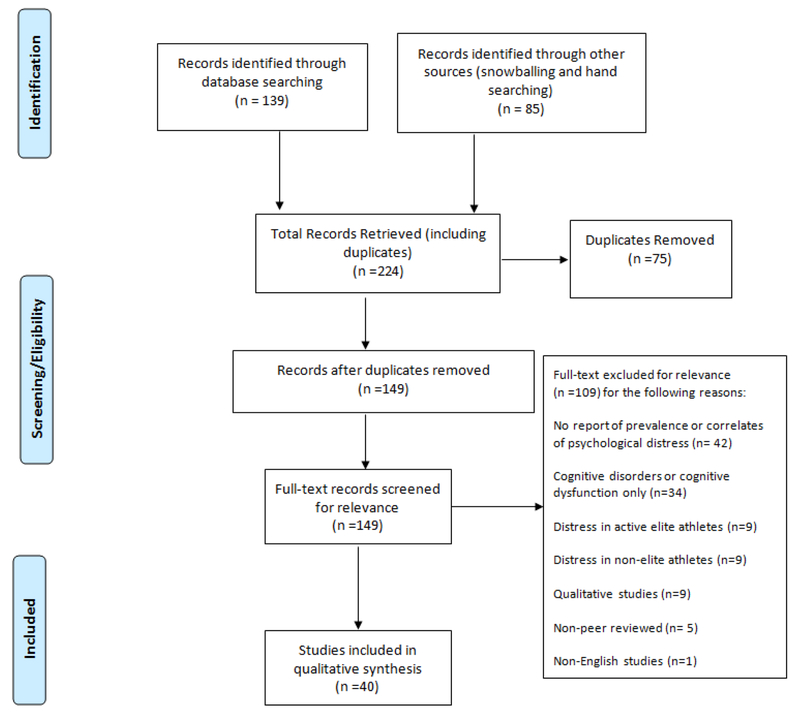

This review focuses on the correlates and prevalence of psychological distress within the scope of: 1) mood symptomatology (e.g., symptoms related to Major Depressive Disorder), 2) anxious symptomatology, and 3) substance use/misuse. Studies examining cognitive impairment exclusively were not included in this review. In total, an initial list of 149 articles was compiled, and upon further review, 40 of these were included. Studies were removed due to the following reasons: non-peer reviewed studies (dissertations, press releases, & news articles n= 5); studies not reporting the prevalence or correlates of psychological distress (i.e., mortality/life expectancy, medical symptoms, healthcare utilization, policy changes, & personality profiles n=42); studies examining psychological distress in active elite athletes n=9; and non-elite athletes n= 9; qualitative studies n=9; non-English studies n=1; and studies discussing findings exclusive to cognitive disorders or cognitive dysfunction n=34 (Figure 1).

Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

Two authors independently evaluated the risk of bias and quality of evidence among the included non-randomized quantitative studies using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 11, a 4-item nominal scale checklist (Pluye et el., 2011). Study quality was based on external validity (i.e., representativeness of sample), validity of measurement, control of confounding factors, and outcome reporting, resulting in a total score ranging from 25% (one criterion met) to 100% (all four criteria met). The MMAT is an effective tool for measuring study quality and has been recently utilized in systematic reviews assessing the quality of evidence of sports and exercise psychology literature (Gayman et al., 2017; Gröpel & Mesagno, 2017; Souto et al., 2015).

Results

Study Characteristics

In total, 40 articles were identified that assessed the prevalence of psychological distress associated with depression, anxiety, and substance use/misuse, or provided statistical evidence that identified important correlates of distress in later adulthood. Twenty-one studies were conducted in the United States, including fifteen examining psychological distress in a professional sport. The additional six studies conducted in the United States examined psychological functioning in samples of athletes from collegiate sports. In the collegiate studies, four of the samples were stratified into collision, contact, and limited-contact sports, and the majority of the samples consisted of former collegiate American football players (Kerr, DeFreese, & Marshall, 2014; Kerr, Evenson, et al., 2014; Simon & Docherty, 2016; Sorenson et al., 2016; Weigand, Cohen, & Merenstein, 2013). Nineteen studies were conducted outside of the United States, and represented geographically heterogeneous samples. These studies included participants from Australia, Finland, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Ireland, France, South Africa, Germany, Belgium, Japan, Switzerland, Norway, France, Chile, Paraguay, Peru, and Spain. Six studies examined psychological distress in retired soccer players, three in rugby populations, and ten in populations of a conglomerate of sports. The majority of articles examined the prevalence of depression only, seventeen studied substance use/misuse, six measured anxiety (Amen et al., 2016; Bäckmand et al., 2001; Bäckmand et al., 2003; Bäckmand et al., 2006; Bäckmand et al., 2009; Kerr, DeFreese, & Marshall, 2014), 10 used a measure that examined a combined construct of anxiety and depression (Brown et al., 2017; Gardner et al., 2017; Gouttebarge et al., 2016; Gouttebarge et al., 2016b; Gouttebarge, Aoki, & Kerkhoffs, 2015; Gouttebarge, Frings-Dresen,& Sluiter, 2015; Gouttebarge, Kerkhoffs, & Lambert 2016; Schuring et al., 2016; Turner, Barlow, & Heathcote-Elliot, 2000; van Ramele et al., 2017), and four studied general mental health (Guskiewicz et al., 2005; Nicholas, et al., 2007; Simon & Docherty, 2016; Sorensen et al., 2016). Please refer to Table 1 for additional information regarding utilized measures, as well as pertinent demographic and psychosocial information.

Table 1.

List of reviewed articles including quality assessment rating, prevalence, primary findings, and additional pertinent information

| Author; Quality Assessment Rating (QA) | Type of Distress | Distress Measure | Prevalence or Measured Score of Distress | Average Years of Age (SD) | Average Years of Play (SD) | Average Years Since Play (SD) | Gender | Country; Sport | Main Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Amen et al., 2016; QA=3 | Depression & Anxiety | Unspecified questionnaire based on DSM-IV criteria; interview by board certified study psychiatrist | Depression: 29.0% Anxiety: 22.0% | 52.0 (14.2) | ≥1 Year | n/a | Men | United States; National Football League | Twenty-nine percent and 22.0% of former NFL players were classified as having depression or anxiety respectively. | ||

| 2. Bäckmand et al., 2001; QA=3 | Depression & Anxiety | BSI-53a | Endurance sports Anxiety: 2.45 Depression: 2.34 Power sports/Combat Anxiety: 2.77 Depression: 3.03 Power sports/Individual Anxiety: 2.73 Depression: 3.01 Team sports Anxiety: 2.67 Depression: 2.46 Shooting Anxiety:2.57 Depression: 2.64 Referents Anxiety:3.17 Depression: 3.57 | 62.5 | n/a | n/a | Men | Finland; international and inter-country athletes in endurance sports, combat sports, power sports, team sports, & shooting | Endurance athletes (cross country skiing & long distance running) and team sport athletes (soccer, ice hockey, & basketball) evidenced significantly less mean depressive scores than non-athlete controls at 10-year follow-up. No significant differences were observed between retired athletes and controls on mean anxiety scores. | ||

| 3. Bäckmand et al., 2003; QA=4 | Depression, Anxiety, & Alcohol Misuse | BSI-53a | Depression: 2.69 Anxiety: 2.66 Heavy drinking: 15.5% | 64.6 | n/a | n/a | Men | Finland; international and inter-country athletes | Decreased physical activity, neuroticism, marital status, life events, and social class were all associated with depression at a 10-year follow-up. Physical activity decreased the risk of depression by 8.0 % from baseline to follow-up. | ||

| 4. Bäckmand et al., 2006; QA=4 | Depression, Anxiety, & Cigarette Smoking | BSI-53a | Depression: Retired Athletes: 2.69 Controls: 3.57 Anxiety: Retired Athletes: 2.66 Controls: 3.17 Current Cigarette Smoking: Retired Athletes: 14.4% Controls: 24.0% | 64.4 | n/a | n/a | Men | Finland; international and inter-country athletes in endurance sports, combat sports, power sports, team sports, & shooting | Retired athletes reported significantly less mean scores on anxiety and depression measures compared to non-athlete controls. Current smoking was less likely among retired athletes than controls. Low levels of physical activity, older age, depression, and anxiety were associated with increased risk of poor physical functioning at 10-year follow-up. Participation in power sports (weight lifting & track and field throwers) and team sports (soccer, ice hockey, and basketball) evidenced a protective effect against poor psychological functioning at follow up. | ||

| 5. Bäckmand et al., 2009; QA=4 | Depression & Anxiety | BSI-53 a | Age 50-59 Depression: 9.2% Anxiety: 9.2% Age 60-69 Depression: 6.6% Anxiety: 8.4% Age ≥70 Depression: 11.2% Anxiety: 10.8% | 68.6 | n/a | n/a | Men | Finland; international and inter-country athletes | There was a 3× increased risk for onset of depression among those retired combat sport athletes. An increase in physical activity protected against onset of anxiety. | ||

| 6. Bäckmand et al., 2010; QA=4 | Alcohol Misuse | Self-report (more than two drinks per day) | Endurance Athletes: 4.7% Power Athletes: 6.4% Team Athletes: 18.2% Non Athletes: 9.0% | 68.6 | n/a | n/a | Men | Finland; international and inter-country athletes in endurance sports, combat sports, power sports, team sports, & shooting | Retired team athletes had the highest prevalence of alcohol misuse compared to non-athletes and retired athletes of other sports. | ||

| 7. Bagge et al., 2017; QA=3 | Lifetime anabolic androgenic steroid use (AAS) & lifetime treatment seeking for psychological distress (i.e., depression & anxiety) | Self-report questionnaire | AAS Abuse: 21.0% | 57.0 (10.0) | n/a | n/a | Men | Sweden; wrestlers, Olympic lifters, powerlifters, and throwers in track and field in the top 10 national ranking lists during any of the years 1960–1979 | Lifetime prevalence of AAS abuse was 21.0%. Previous AAS abuse was associated with higher self-reported lifetime prevalence of seeking professional help for depression and anxiety. | ||

| 8. Brown et al., 2017; QA= 2 | Depression/Anxiety & Adverse Alcohol Use | GHQ-12e, AUDIT-Cf | Voluntary retirement: Depression/Anxiety: 26.1% Adverse Alcohol Use: 21.9% Forced retirement: Depression/Anxiety: 32.7% Adverse Alcohol Use: 34.5% | Voluntary retirement: 39.0 (5.0) Forced retirement: 37.0 (5.0) | Voluntary retirement: 9.2 (3.8) Forced retirement: 8.4 (3.7) | Voluntary retirement: 7.6 (4.5) Forced retirement: 7.2 (4.3) | Men | Ireland, France, & South Africa; Rugby Union | No significant differences between groups on prevalence of depression/anxiety and adverse alcohol use. The prevalence of anxiety/depression was similar to that of the general population, while alcohol misuse was lower in retired rugby athletes as compared to the general population. | ||

| 9. Casson et al., 2014; QA=2 | Depression | BDIb, PHQc | BDI: Mild depression: 20% Moderate depression: 6.7% Severe Depression: 6.7% PHQ: Depressed: 20.0% | 45.6 (8.9) | 6.8 (3.2) | n/a | Men | United States; National Football League | The prevalence of depression was comparable to that of the general population. | ||

| 10. Cottler et al., 2011; QA=3 | Opioid Misuse | Survey of Retired NFL Football Players | 7.0% currently used opioids | 48.3 (9.24) | 7.6 (3.8) | 17.7 (8.47) | Men | United States; National Football League | Players who misused opioids during their NFL career were more likely to misuse in retirement compared to those whom did not misuse. Current misuse was associated with increased pain, undiagnosed concussions, and heavy drinking. | ||

| 11. Didehbani et al., 2013; QA=2 | Depression | BDI-IIn | Mild depression: 20.0% Moderate depression: 20.0% | 58.6 (10.33) | 9.17 (3.11) | n/a | Men | United States; National Football League | NFL players endorsed a greater number of depressive symptoms on affective, cognitive, and somatic domains compared with matched controls. Greater number of experienced concussions during playing career may be related to cognitive (e.g., sadness, guilt, critical self-evaluations) symptoms of depression in retirement. | ||

| 12. Esopenko et al., 2017; QA=3 | Alcohol Dependence, Non-alcohol related Substance Dependence & Major Depressive Disorder | SCID-IVm | Alcohol Dependence: Current: 5.2% Past: 31.5% Non-alcohol related substance dependence: Current: 0% Past: 5.2% MDD: Current: 21.0% Past: 21.0% | 54.3 (10.4) | n/a | n/a | Men | United States & Canada; National Hockey League | According to the SCID-IV, approximately 59.0% of retired hockey athletes met criteria for current or past psychiatric diagnoses. There was a significant difference between retired hockey players and aged-matched control participants on number of participants meeting criteria for a psychiatric disorder χ2(1, N=48)= 7.09, p=0.008. | ||

| 13. Ford, Giovanello, & Guskiewicz, 2013; QA=2 | Depression | GDSd | Low concussion: 5.5 (4.6) High Concussion 8.8 (7.2) | 63.4 (5.9) | n/a | n/a | Men | United States; National Football League | The “high” concussion group scored higher on the GDS than the low concussion group. The mean scores of each group indicated a “normal” score. | ||

| 14. Gardner et al., 2017; QA=3 | Depression/Anxiety & Adverse Alcohol Use | DASS-21k AUDIT-Cf | n/a | 38.3 (4.6) | n/a | 6.9 | Men | England; Professional Rugby League | There were no significant differences in DASS depression, anxiety, or stress scores between retired athletes and controls. Retired athletes scored higher than controls on the AUDIT with 10 retired athletes and only two controls reporting at least hazardous drinking behavior. | ||

| 15. Gouttebarge, Aoki, & Kerkhoffs, 2015; QA=3 | Depression/Anxiety, Tobacco Smoking, & Adverse Alcohol Use | GHQ-12e, AUDIT-Cf | Depression/Anxiety: 35.30% Cigarette Tobacco Smoking: 11.4% Adverse Alcohol Use: 24.6% | 35.0 | 12.0 | 4.0 | Men | Belgium, Chile, Finland, France, Japan, Norway, Paraguay, Peru, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland; World Footballers’ Union (FIFPro) | Greater number of adverse life events in the past six months was positively associated with distress, anxiety/depression, and sleep disturbance. | ||

| 16. Gouttebarge, Kerkhoffs, & Lambert, 2016; QA=2 | Depression/Anxiety, Tobacco Smoking, & Adverse Alcohol Use | GHQ-12e, AUDIT-Cf | Depression/Anxiety: 28.4% Cigarette Smoking: 15.0% Adverse Alcohol Use: 23.8% | 38.0 | 9.0 | 8.0 | Men | Ireland, France, & South Africa; Rugby Union | Psychological distress was associated with greater negative life events and a higher level of Rugby Union career dissatisfaction. | ||

| 17. Gouttebarge, Aoki, et al., 2016; QA=3 | Depression/Anxiety & Adverse Alcohol Use | GHQ-12e, AUDIT-Cf | Depression/Anxiety: 35.0% Adverse Alcohol Use: 23.8% | 35.0 (6.4) | 11.6 (5.0) | 4.4 (3.6) | Men | Belgium, Chile, Finland, France, Japan, Norway, Paraguay, Peru, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland; World Footballers’ Union (FIFPro) | Employment status and higher number of working hours was negatively correlated with symptoms of anxiety/depression. | ||

| 18. Gouttebarge et al., 2016; QA=3 | Depression/Anxiety & Adverse Alcohol Use | GHQ-12e, AUDIT-Cf | Retired Athletes: Depression/Anxiety: 29.4 Adverse Alcohol Use: 23.2% Current Athletes: Depression/Anxiety: 44.7 Adverse Alcohol Use: 6.4% | Retired Athletes: 50.7 (15.1) Current Athletes: 27.3 (7.1) | Retired Athletes: 10.8 (5.2) Current Athletes: 7.5 (5.0) | Retired Athletes: 20.2 (15.4) Current Athletes: n/a | Men & Women | The Netherlands; Retired athletes and current members of the Netherlands Olympic Committee, & Netherlands Sports Confederation | Current athletes reported a higher prevalence of depression/anxiety compared to retired athletes while retired athletes reported a higher prevalence of adverse alcohol use. Retired athletes who reported a higher number of severe injuries, surgeries, recent adverse life events, higher level of career dissatisfaction and lower level of social support were significantly more likely to report symptoms of depression/anxiety. Career dissatisfaction was associated with a decreased likelihood of reporting adverse alcohol use. | ||

| 19. Gouttebarge, Frings-Dresen, & Sluiter, 2015; QA=2 | Depression/Anxiety, Tobacco Smoking, & Adverse Alcohol Use | GHQ-12e, AUDIT-Cf, | Depression/Anxiety: 39% Tobacco Smoking: 12.0% Adverse Alcohol Use: 39% | 36.5 | 12.0 | n/a | Men | Australia, Ireland, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Scotland and the United States; World Footballers’ Union (FIFPro) | There is a higher prevalence of psychological distress among retired athletes compared to current athletes. Retired athletes with previous operations were nearly twice as likely to smoke compared with those with no previous operations. Recent negative life events and low supervisor support were associated with increased odds of experiencing psychological distress. | ||

| 20. Guskiewicz et al., 2005; QA=3 | General Mental Health | SF-36g | Concussions 0= 54.35 (8.50) 1= 52.63 (9.47) 2=52.97 (9.22) 3+=50.31 (11.26) | 53.8 (13.4) | 6.6 (3.6) | n/a | Men | United States; National Football League | Mental Component Scale (MCS) scores on the SF-36 were similar between retired athletes and population-based normative values for all age groups. Retired athletes with a history of concussions scored worse on the MCS than those without a history of concussions. | ||

| 21. Guskiewicz et al., 2007; QA=4 | Depression | n/a | Depression (Clinically Diagnosed): 11.1% | 53.8 (13.4) | 6.6 (3.6) | 24.7 (13.7) | Men | United States; National Football League | Prevalence of depression increased with previous concussions. Depressed retirees reported lower mental and physical component scores compared with former NFL players not previously diagnosed with depression. Retirees reporting 3+ concussions were 3× more likely to endorse receiving a previous depressive diagnosis. | ||

| 22. Hart et al., 2013; QA=2 | Depression | n/a | Depression (Clinically Diagnosed): 23.5% | 61.8 | 9.7 | n/a | Men | United States; National Football League | Depression is more common in retired NFL athletes as compared to the general population. | ||

| 23. Horn, Gregory, & Guskiewicz, 2009; QA=3 | Depression | n/a | Depression (Clinically Diagnosed): Steroid Users: 21.0% Non Users: 10.3% | 53.8 (13.4) | 6.6 (3.6) | n/a | Men | United States; National Football League | Steroid use was significantly related to depression. | ||

| 24. Kerr, DeFreese, & Marshall, 2014; QA=2 | Depression, Anxiety, & Alcohol Dependence | VR-12h | Anxiety: 16.2% Depression: 10.4% Alcohol dependence: 5.8% | 25–44 years: 79.4% | 10.7 | 14.5 | Men & Women | United States; College, Division 1: Collision, contact, limited contact | Former collegiate athletes scored similarly on items of mental and physical health as compared to non-athletes. Lower physical health scores were associated with sustaining at least three concussions and sustaining a career-ending injury. There was no association between reported concussions and total mental health scores. | ||

| 25. Kerr et al., 2014; QA=3 | Depression | PHQ-9c | Minimal-Mild: 95.3% Moderate-Severe: 4.7% | >44: 84.8% <45: 15.2% | 10.5 (5.7) | 14.5 (7.41) | Men & Women | United States; College, Division 1: Collision, contact, limited contact | Retired athletes sustaining at least three concussions during their playing career were 2.4 times more likely to be categorized as depressed compared to those reporting no prior concussions. | ||

| 26. Kerr et al., 2012; QA=4 | Depression | n/a | Depression (Clinically Diagnosed): 10.2% | n/a | n/a | n/a | Men | United States; National Football League | 9-year risk of depression showed a linear relationship with increasing numbers of self-reported concussions such that 3.0% were classified as depressed in the “no concussions” group while 26.8% were classified as depressed in the “10+” concussion group. The association between concussions and depression was independent of the relationship between depression and decreased physical health. | ||

| 27. Kontro et al., 2017; QA=3 | Alcohol related disease or death | National Discharge Register based on hospital admittance and corresponding ICD-8, ICD-9, and ICD-10 codes | Alcohol-related disease, Retired athletes: 6.2% Controls: 7.1% | 74.7 (7.2) | n/a | n/a | Men | Finland; Olympians, European or World champions, or international contestants in track and field, weightlifting, combat sports, team sports, & shooting | There was no significant difference in the risk of any alcohol-related disease or death between all former athletes and controls. The risk of alcohol-related disease or death was higher among both combat sports athletes and weightlifters compared with endurance sports athletes, shooters or jumpers, and hurdlers. Team sports athletes consumed significantly more alcohol compared with other athletes and controls. Athletes who were not engaged in leisure-time sports after their active sports career consumed more alcohol than those who were engaged in leisure-time sports or physical activities. | ||

| 28. Kuhn et al., 2017; QA=2 | Depression | BDI-IIm PHQc | BDI-II: 9.71 (9.6) PHQ: 26.5 (19.9) | 46.7 (9.1) | n/a | n/a | Men | United States; National Football League | The average depression score among all retired NFL players was indicative of minimal depressive symptoms according to the BDI-II. | ||

| 29. Lindqvist et al., 2013; QA=3 | Anabolic Androgenic steroid use (AAS), Lifetime illicit drug use, & Lifetime treatment seeking for psychological distress (i.e., depression & anxiety) | Self-report questionnaire | Depression: Former AAS Users: 13.0% Lifetime Nonusers: 5.0% Anxiety: Former AAS Users: 13.0% Lifetime Nonusers: 6.0% Lifetime Illicit Drug Use: Former AAS Users: 18.0% Lifetime Nonusers: 4.0% | 57.0 (10.0) | n/a | n/a | Men | Sweden; Wrestlers, Olympic lifters, Powerlifters, and the throwers in track and field top 10 national ranking lists | At least 20% of retired athletes reported previous AAS use. Former AAS-users had a significantly higher lifetime prevalence concerning seeking professional expertise for mental-health problems like depression, anxiety, melancholy, concentration deficit and worry for mental health compared with those not having used AAS. However, the former AAS-users had more often used illicit drugs, and the non-AAS-users were presently more addicted to tobacco. | ||

| 30. Nicholas et al., 2007; QE=3 | General Mental Health | SF-36g | Arthritis: 53.1 Chronic back pain: 51.7 | 62.0 (3.0) | 8.3 (3.8) | 32.0 (3.0) | Men | United States; National Football League | Average physical and mental health scores were not significantly different from average scores in the general population. | ||

| 31. Prinz, Dvořák, & Junge, 2016; QA=3 | Depression | PHQ-2c | Depressed: 8.50% | 33.0 (6.25) | 8.65 (5.13) | 6.48 (3.56) | Women | Germany; German First Soccer League | Retired athletes with more injuries and higher depression scores during their career had higher scores of depression after they retired. Injuries, feeling down, and having too much spare time were commonly reported problems following career. | ||

| 32. Schwenk et al., 2007; QA=2 | Depression | PHQ-9c | Moderate to Severe Depression: 14.7% | 53.4 (14.5) | 7.1 (3.6) | 25.0 | Men | United States; National Football League | Pain increases the likelihood of moderate to severe depression. Depression and pain were associated with difficulties with sleep, finances, social relationships, exercise, and fitness. | ||

| 33. Schuring et al., 2016; QA=2 | Depression/Anxiety & Adverse alcohol use | GHQ-12e, AUDIT-Cf | Anxiety/Depression: OAl: 30.8% No OA: 25.30% Adverse Alcohol Use OA: 33.8% No OA: 22.5% | 37.0 (6.0) | 10.0 (5.0) | 65.0 | Men | Finland, France, Ireland, Norway, South Africa, Spain, Sweden and/or Switzerland; Rugby, soccer, ice hockey, Gaelic sports, and cricket | OA was associated with distress, sleep disturbance, and adverse alcohol use. OA and associated pain may be seen as a risk factor for the occurrence of symptoms of psychological distress. | ||

| 34. Simon & Docherty, 2016; QA=3 | General Mental Health | SF36v2g | Collision Athletes: T ≈ 48 Contact Athletes: T ≈ 51 Limited Contact Athletes T ≈ 57 | Collision athletes: 52.29 (7.36) Contact athletes: 52.92 (7.37) Limited-contact athletes: 51.79 (7.83) | Competed for four years: 75% Competed for 2, 3, or 5 years: <10% Competed between 1 and 10 years: 30% | n/a | Men & Women | United States; College, Division 1: Collision, contact, limited contact | The collision athletes, mostly former Division I football players, scored worse on the physical functioning, bodily pain, and mental health scales compared to the contact athletes, limited-contact athletes, and the general US population. Both the contact and limited-contact athlete groups scored better than the general population on mental health subscales. | ||

| 35. Simon & Docherty, 2013; QA=2 | Depression | PROMISI | Athletes: T ≈ 53 Nonathletes: T ≈ 45 | 53.36 (7.11) | Competed for 3–4 years: 77.0% Competed for 5 years: 12.0% Competed for 2 years: 22.0% 1–7 years competing in pro. athletics: 22.0% | n/a | Men & Women | United States; College: Division 1, Unspecified | Former Division I athletes had decreased health compared with non-athletes as it relates to depression, fatigue, physical functioning, sleep disturbance, and pain. There were no significant differences between athletes and non-athletes on average anxiety scores. | ||

| 36. Sorenson et al., 2014; QA=4 | General Mental Health | VR-12h | n/a | 45.6 (16.2) | n/a | n/a | Men & Women | United States; College: Division 1, Football, Basketball, Track & Field, Tennis, Golf, Rowing, Cross Country, Swimming & Diving, Water polo | Mental health composite scores were similar between retired student athletes and alumni non-athletes. | ||

| 37. Strain et al., 2013; QA=2 | Depression | BDI-IIb, confirmatory clinical diagnosis provided via diagnostic interview by trained psychologists | Depression: 19.2% | 57.8 (11.3) | 8.62 (3.75) | n/a | Men | United States; National Football League | All retired athletes classified as depressed reported at least three concussions. Four of the five retired athletes classified as depressed reported symptom onset occurrence following retirement from the NFL and one reported depression symptoms immediately following a concussion. Only 2 participants were currently undergoing treatment for depression. | ||

| 38. Turner, Barlow, & Heathcote-Elliot, 2000; QA=2 | Depression/Anxiety | EQ-5Dj | OA: 37% Non-OA: 19% | 56.1 (11.8) | 13.5 (5.3) | 23.8 | Men | United Kingdom: Premier League and International Soccer competitors | Players with osteoarthritis were at an increased likelihood of endorsing symptoms of depression/anxiety. A career in professional soccer is associated with chronic health problems in later life. | ||

| 39. Van Ramele et al., 2017; QA=2 | Depression/Anxiety & Adverse Alcohol Use | GHQ-12e, AUDIT-Cf | Depression/Anxiety: 29.0% Adverse Alcohol Use: 15.0% | 35.0 | 12.0 | 4.0 | Men | Soccer, Footballers’ Union (FIFPro) | Retired athletes may experience greater amounts of psychological distress as compared to non-athletes. Approximately 83% or retired athletes reported receiving insufficient medical care in retirement, while 43% reported that psychological distress has an influence on their quality of life. | ||

| 40. Weigand, Cohen, & Merenstein, 2013; QA=2 | Depression | Wakefield Depression Scale | Depressed: 8.03% | 21–23: 59% >23: 52% | n/a | <2 years | Men & Women | United States; College, Division 1: Collision, contact, limited contact | Depression was more prevalent in current college athletes compared to former athletes. |

Quality of Evidence

Using MMAT scoring, 7 studies met 100% of quality criteria, 17 met 75%, and the remaining articles (n=16) met 50%. Methodological quality score for each study are included in Table 1.

Of the 40 studies included in this review, sample size ranged from 26– 2675 participants, with epidemiological studies comprising larger samples and studies utilizing neurocognitive testing and brain imaging including smaller numbers of participants (Bäckmand et al., 2001; Strain et al., 2013). Twenty-nine studies included least 100 participants, of which 82% had 200 participants or more. Over half (62%) of the included studies did not include information related to age, average years of play, or average years of retirement, all factors that can influence the trajectory and prevalence of psychological distress. Additionally, only 6 studies examined the prevalence of psychological distress utilizing a mental healthcare professional (i.e., psychologist or psychiatrist) while all other studies (85%) relied on self-report measures of distress (Amen et al., 2016; Guskiewicz et al., 2007; Hart et al., 2013; Horn, Gregory, & Guskiewicz, 2009; Kerr et al., 2012; Strain et al., 2013). In the studies utilizing self-report screeners, 20 different measures of psychological distress were used. In regard to demographics, seven studies included women, though only one study examined the prevalence of psychological distress among a sample comprised of all women (Prinz, Dvořák, & Junge, 2016). Additionally, only eight studies reported on the racial/ethnic background of their sample, and no studies examined how and risk factors differed by race.

Ten studies reported on a combined construct of anxiety/depression (i.e., General Health Questionnaire) in samples of retired rugby and soccer players, limiting the ability to assess for more comprehensive symptoms of distress and validate current prevalence of distress in these athlete populations. Only 17.5% (n=7) of studies incorporated longitudinal designs (Bäckmand et al., 2001; Bäckmand et al., 2003; Bäckmand et al., 2006; Bäckmand et al., 2010; Bäckmand et al., 2009; Kerr et al., 2012; Kontro et al., 2017). Also, only 13 of the 40 studies compared prevalence rates to a matched, non-athlete control group. In regard to analytical approach, 60% (n=24) of studies utilized univariate or bivariate analyses.

Prevalence

Depression

In the 21 studies examining the prevalence of depression, there were 16 variations of depression classification. Prevalence ranged from 4.7% to 29.0% in sample populations. Among former NFL players, five studies assessed depression through utilizing a postcareer clinical diagnosis, of which, more often resulted in a higher prevalence of depression compared to studies utilizing a self-report measure of depressive distress (Amen et al., 2016; Guskiewicz et al., 2007; Hart et al., 2013; Horn et al., 2009; Kerr et al., 2012). Though only 10%–21% of participants endorsed receiving a depression diagnosis prior to study enrollment, studies utilizing a psychologist or psychiatrist to assess current depressive symptomatology resulted in the highest prevalence, with up to 29% reporting significant depression, and none of these studies demonstrating less than a 20% prevalence rate (Amen et al., 2016). Additionally, assessment of Major Depressive Disorder utilizing the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCIDIV) among retired National Hockey League (NHL) athletes yielded a prevalence rate greater than 20% (Esopenko et al., 2017). Date of depression onset, duration of depressive episode, first reported lifetime depressive episode, and number of lifetime depressive episodes were not reported in the aforementioned studies. The additional studies examining the prevalence of depression in NFL players utilized self-report measures; in these studies participants classified as depressed ranged from 4.7% to 20.0%, rates generally lower than studies utilizing a clinical assessment or structured interview (Casson et al., 2014; Didehbani et al., 2013; Kerr, DeFreese et al., 2014; Kerr, Evenson et al., 2014; Kuhn et al., 2017; Schwenk et al., 2007; Strain et al., 2013). In sports alternative to football and hockey, studies suggested lower prevalence rates of depression, particularly among retired soccer athletes (8.5%) and former collegiate athletes (10.4%; Kerr, DeFreese et al., 2014; Prinz et al., 2016).

Anxiety

Six studies measured anxiety exclusively. Similar to depression, the highest prevalence of anxiety was observed in a study assessing current distress through utilization of a board certified psychiatrist, with 22.0% of retired NFL players classified as anxious (Amen et al., 2016).

Prevalence of retired athletes reporting significant anxious distress ranged from 8.4%−16.2% in the five studies utilizing self-report measures. The prevalence of anxiety was lowest among former Finnish athletes aged 60–69 (8.4%) and highest among former Division 1 collegiate athletes, with 16.2% reporting anxiety based on responses from the Veterans Rand 12-Item Health Survey (Bäckmand et al., 2009; Kerr, DeFreese, & Marshall, 2014).

Depression/Anxiety

Ten studies examined the prevalence of anxiety and depression in totality using the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ). Depression and anxiety were prevalent among international soccer and rugby athletes (39.0% and 28.0% respectively; Gouttebarge, Frings-Dresen, & Sluiter, 2015; Gouttebarge, Kerkhoffs, & Lambert, 2016).

In studies examining the influence of physician diagnosed osteoarthritis on psychological distress, the prevalence of anxiety/depression in former soccer players from the United Kingdom was 37.0% among athletes with osteoarthritis, compared to 19.0% of players without osteoarthritis, indicating a potential modifying effect of osteoarthritis on experiencing anxiety or depressive symptoms in this group (Turner et al., 2000). Similarly, 30.80% of younger (Mean age= 37.0) rugby, soccer, ice hockey, and cricket retirees with physician-diagnosed osteoarthritis screened positive for anxiety/depression, compared to just 25.3% among retired athletes not diagnosed with osteoarthritis (Schuring et al., 2016).

Substance Use/Misuse

In the four studies examining tobacco use, prevalence was similar across studies of retired athletes from different sports, ranging from 11.4% in a group of retired soccer players to 15.0% in retired rugby players (Gouttebarge, Kerkhoffs, & Lambert, 2016; Gouttebarge et al., 2016).

Contrastingly, it appeared that sports where athletes are more prone to injury and resultant medical comorbidities demonstrated the highest prevalence of substance misuse. Specifically, former soccer, rugby, hockey, and NFL athletes were at greatest risk of alcohol misuse and opioid use/misuse in retirement compared to international athletes, endurance athletes, and samples comprising athletes of different sports (Kontro et al., 2017). In the fourteen studies assessing alcohol misuse, the prevalence of misuse ranged from 5.8% in a sample of former American college athletes to 39% among retired soccer players (Kerr, DeFreese, & Marshall, 2014; Van Ramele et al., 2017). Additionally, 34.5% former rugby players who experienced “forced retirement” were classified as “adverse alcohol” drinkers based on AUDIT-C criteria (Brown et al., 2017). Retired rugby players also scored higher than controls on the AUDIT, with ten retired athletes and only two controls reporting at least hazardous drinking behavior (Gardner et al., 2017). In the one study that assessed for symptoms via structured interview, 31.5% of retired hockey athletes reported previously meeting criteria for alcohol dependence (Esopenko et al., 2017). Physician diagnosed osteoarthritis also appeared to have a moderating effect on alcohol consumption behaviors, with 33.8% of retired soccer players with osteoarthritis reporting adverse alcohol use compared to only 22.5% of those without osteoarthritis (Schuring et al., 2016).

Three studies examined illicit substance use among retired elite athletes, concluding that opioid use/misuse was a salient problem across different sports. Among former NFL players, 7.0% were currently using opioids, a prevalence three times higher than the general population, and 15.0% of those who misused during their NFL career were currently misusing (Cottler et al., 2011). Among retired NHL athletes, 12.0% continued to report opioid use after retirement (Esopenko et al., 2017).

Correlates

Concussions

The relationship between concussion history and depressive distress was primarily examined in studies of retired NFL players. Several studies showed a nonsignificant relationship between concussion history during playing career and psychological distress in adulthood (Casson, et al., 2014; Esopenko et al., 2017; Kerr, DeFreese, & Marshall, 2014). Similarly, though NFL players endorsed more symptoms on cognitive, somatic, and affective domains of depression on the BDI-II than none NFL players, only the cognitive factor was significantly correlated with the number of concussions, which included feelings of sadness, guilt, and self-criticism (Didehbani et al., 2013). However, most studies demonstrated a significant relationship between reported undiagnosed/diagnosed concussions and psychological distress, including depression and opioid misuse (Cottler et al., 2011). Experiencing 3 or more concussions placed retired athletes at greater risk of reporting depressive distress, with only retired NFL athletes experiencing at least three concussions during playing career reporting a depression diagnosis (Strain et al, 2013). Similarly, 20% of retired NFL players who reported 3+ concussions had been previously diagnosed with depression, compared to 9.7% and 6.5% in the 1 or 2, and 0 concussion group respectively (Guskiewicz et al., 2007). Several additional studies also showed a dose response relationship between concussions and greater likelihood of experiencing depressive distress among both retired NFL and former collegiate athletes (Didehbani et al., 2013; Guskiewicz et al., 2007; Kerr et al., 2014). In the one longitudinal study examining the relationship between concussion and clinical depression among retired NFL players, Kerr and colleagues (2012) found that the 9-year risk of depression showed a linear relationship with an increasing number of self-reported concussions such that 3.0% were classified as depressed in the “no concussions” group while 26.8% were classified as depressed in the “10+” concussion group. The association between concussions and depression was significantly confounded by years since retirement and lower rated physical health in multivariate analyses, though concussion history remained a significant risk factor for diagnosed depression (Kerr et al., 2012).

In sports alternative to football, the literature yielded mixed results. Former Division I collision athletes (i.e., football and diving) had lower mental health functioning compared with limited contact athletes (i.e., baseball, cross-country, softball, tennis, track & field, & swimming; Simon & Docherty, 2016). However, when collision athletes were compared to that of the general population, composite mental health scores did not differ significantly. Several studies showed that concussion history was not associated with psychological distress. Composite mental health scores were not significantly different between groups of collegiate athletes reporting 0, 1–2, or ≥3 concussions (Kerr, DeFreese, & Marshall, 2014). Additionally, concussion history was not significantly associated with psychological distress among former NHL athletes, leading authors to postulate that alternative factors may have contributed to the disproportionally higher prevalence of psychological distress among retired hockey players compared to matched controls (Esopenko et al., 2017). The relationship between concussion history and psychological distress was not examined in samples comprised exclusively of soccer and rugby athletes, sports where prevalence of concussion is high.

Pain, Injury, and Osteoarthritis (OA)

Similar to concussions, the reviewed articles demonstrated a robust relationship between pain, injury, OA, and later-life psychological distress. NFL retirees had the most significant pain, with 93% reporting pain and 70% of athletes perceiving their pain to be moderate or severe (Cottler et al., 2011). Greater pain was associated with current opioid misuse (Cottler et al., 2011). Additionally, Schwenk and colleagues (2007) noted that retired professional football players experienced depression severity comparable to that of the general population, but more severe self-reported pain exacerbated symptoms of depression. The combination of depression and pain was significantly associated with difficulties with sleep, finances, social relationships, exercise, and fitness. Former collegiate collision athletes also scored significantly worse than age-matched population controls on a bodily pain score, and former Division I athletes had lower health related QOL compared with non-athletes as it relates to physical functioning and pain (Simon & Docherty, 2013; Simon & Docherty, 2016). Physical complaints (pain, discomfort, impairments) were hypothesized to be a risk factor for the onset and greater severity of symptoms associated with psychological distress (Schuring et al., 2016; Turner et al., 2000).

Several studies also examined the moderating effect of pain, injury, and OA on post-career psychological distress. Among female soccer players, players with more injuries during their career reported higher scores on a depression screener after their career compared to their less injured counterparts (Prinz et al., 2016). Former players with previous surgical operations were also twice as likely to use tobacco compared to those with no surgical history (Gouttebarge et al., 2015). OA also increased the risk of reporting symptoms of depression/anxiety (Turner et al., 2000). Turner and colleagues (2000) concluded that injuries sustained during a playing career may be associated with chronic mental health problems in later adulthood.

Physical Activity

Greater physical activity decreased the risk of depression by 8.0% and acted as a protective factor against anxiety onset, while less physical activity led to a threefold increase in the odds of being classified as depressed at ten-year follow-up (Bäckmand et al., 2003; Bäckmand et al., 2009). Pain, injury, and depression may be risk factors of less engagement in physical activity, as former NFL players who scored as moderate to severely depressed were more likely to report a loss of fitness and lack of exercise, while former intercollegiate athletes reported significantly greater physical activity limitations compared to age-matched non-athlete controls (Simon & Docherty; 2013; Schwenk et al., 2007).

Psychosocial Factors

A multitude of psychosocial factors were associated with psychological distress in retirement. Less social support, being unmarried, financial instability, and a difficult retirement transition were associated with greater depressive distress (Bäckmand et al., 2003; Guskiewicz et al., 2007; Prinz et al., 2016; Schwenk et al., 2007). Additionally, career dissatisfaction, adverse life events, low supervisor/coach support, having too much spare time, having no or vague future plans following athletic career, and higher depression scores during playing career were associated with current depression severity (Gouttebarge, Frings-Dresen et al., 2015; Gouttebarge, Jonkers et al., 2016; Gouttebarge, Kerkhoffs et al., 2016; Prinz et al., 2016). Conversely, being employed, having a greater number of working hours, and a longer duration of retirement from sport were negatively associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety (Gouttebarge, Aoki et al., 2016; Kerr et al., 2012).

Discussion

Prevalence of Psychological Distress

To the author’s knowledge, this is the first review examining the prevalence of psychological distress among retired elite athletes. Forty articles assessed the prevalence of psychological distress associated with symptomatology related to depressed mood, anxiety, and substance use/misuse. Of these articles, the prevalence of psychological distress ranged from 4.8% (depression) to 39.0% (depression/anxiety). This review indicated that prevalence of psychological distress among retired elite athletes was similar to that of the general population. However, psychological distress was more common in specific subgroups experiencing comorbid difficulties. For example, NFL players reporting greater pain, higher concussion incidence, and substance misuse during their career were more likely to report distress related to depression and substance misuse after they retired. Additionally, former athletes who experienced more injuries during their career and reported an OA diagnosis also reported significantly higher prevalence of depression/anxiety and alcohol misuse compared to their unaffected counterparts (Schuring et al., 2016; Turner et al., 2000).

Much like in former NFL players, pain and injury is commonplace in high-contact international sports such as rugby and soccer (King et al., 2013; Orchard & Seward, 2002; Targett, 1998). Despite increased risk of experiencing adverse physical heath sequelae, the review yielded only three studies examining psychological distress in rugby players exclusively. Among the present studies examining psychological distress in sports alternative to football and conducted outside of the United States, similar prevalence rates of psychological distress associated with depression, anxiety, and substance misuse were identified. To this point, additional studies are needed to examine the prevalence of psychological distress among retired professional athletes of sports alternative to the ones already in the literature, specifically those at higher risk for the experiencing painful medical conditions during playing career such as college or professional baseball, basketball, and tennis, as well as contact/collision sports such as boxing, wrestling, and mixed martial arts. Similar to the National Football League and World Rugby Organization, the National Hockey League (NHL) has faced recent legal scrutiny, as more than 100 players have filed class-action lawsuits for detrimental health effects resulting from sustained concussions during their playing career (Kilgore, 2015). Unlike the recent research focus on the potential detrimental mental health consequences following a career in the NFL, only one recent quantitative study has been conducted examining the prevalence of psychological distress following the career of elite hockey players despite high concussion incidence (Benson et al., 2011; Wennberg & Tator, 2008). In this study, Esopenko et al., noted that 59% of retired NHL athletes experienced current or past psychological distress, compared to just 19% of matched controls. These findings indicate a need for additional studies examining the prevalence and risk factors of psychological distress among elite hockey players.

Substance use and misuse was apparent in the reviewed literature. Athletes of contact sports and sports demonstrating higher rates of injury reported a higher prevalence of alcohol misuse in retirement. Specifically, up to 34.5% of athletes reported alcohol misuse in samples of retired rugby, soccer, and hockey players (Brown et al., 2017; Esopenko et al., 2017; Gardner et al., 2017; Gouttebarge, Frings-Dresen, & Sluiter, 2015; Schuring et al., 2016). Heavy drinking (i.e., 14 or more drinks over seven days) was also associated with opioid use in this population (Cottler et al., 2011). Additionally, Cottler and colleagues (2011) reported that 71.0% of former NFL players misused opioids during their playing career, and 7% reported sustained misuse following retirement, while 12.0% of retired hockey players continued to report opioid use after their career had ended (Esopenko et al., 2017). These were the only two studies in this review that examined the use of illicit substances both during and following the career of former elite athletes. Additionally, two studies demonstrated that lifetime prevalence of AAS abuse was approximately 21.0%, and these athletes had a greater likelihood of using other illicit substances as well as seeking professional help for depression and anxiety in retirement as compared to non-AAS users (Bagge et al., 2017; Lindqvist et al., 2013). Based on the prevalence of substance use/misuse among retired athletes observed in these studies, additional policies that monitor and manage drug use during the post-career phase of retired elite athletes are needed.

Correlates of Psychological Distress

Several correlates of psychological distress were identified from this review. Concussions, pain, injury, osteoarthritis, physical inactivity, and psychosocial factors were associated with psychological distress among retired elite athletes. Though the studies comprising this review demonstrated psychological distress comparable to the general population, former athletes with these risk factors exhibited higher rates of psychological distress.

Among elite football players, there is evidence showing a significant association between sustained concussions and depressive symptomatology. This review found evidence for this pattern and identified a multitude of other factors associated with psychological distress. A number of articles in our review found null and attenuated relationships between concussions and psychological distress, with several additional studies demonstrating no significant differences in prevalence of psychological distress between retirees of collision/contact sports compared to non-athletes. The findings presented in these articles may support the complexity of the interplay of factors associated with psychological distress in later adulthood, and speak to the importance of studying correlates of psychological distress beyond repetitive head trauma (Asken et al., 2016).

The relationship between pain and psychological distress was robust across former athletes from many sports. Those with painful medical conditions such as osteoarthritis were at greater risk for reporting symptoms of depression and anxiety, as well as substance misuse following retirement. The relationship between concussions, pain, and depression is complex, and no study in this review analyzed interacting effects. In one study that controlled for pain and tried delineating the effects of pain versus concussions, pain and years of retirement were significant confounders in the relationship between concussions and depression, while several other studies did not include pain in multivariate models (Kerr et al., 2012). Mainwaring and colleagues (2010) noted that athletes experiencing an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury reported more significant depressive symptoms for a longer duration following injury as compared to athletes who experienced a concussion. Emotional distress following serious orthopedic injury may vary from that of a concussion, and thus may contribute to future variable psychological distress depending on the experienced injury. Unanticipated severe orthopedic injuries also frequently reduce career longevity or lead to premature, unplanned retirement. Given the inconclusive nature of the relationship between pain, concussions, psychosocial risks, and depression, examining the effects of these factors together in future studies may help identify their relative influence on psychological functioning.

Though athletes experience a multitude of psychosocial stressors that can impact their psychological functioning, a prominent psychosocial stressor amongst retired athletes and one identified by this review was financial instability. In regard to NFL players, many former athletes file for bankruptcy within the first twelve years of their retirement (Carlson, Kim, Lusardi, & Camerer, 2015). It is estimated that approximately 78.0% of NFL players file for bankruptcy or are under financial stress as soon as two years following their career, while 60.0% of National Basketball Association (NBA) players file for bankruptcy within the first five years of retirement (Torre, 2009). Indebtedness has a myriad of well-documented physical and psychological health consequences (Turunen & Hiilamo, 2014). Unpredictable adverse life events can aggregate, further compounding possible psychological distress experienced as a result of the physical consequences from a career in elite athletics.

The majority of reviewed studies investigated factors associated with later-life psychological distress, while few examined potential protective factors against distress. Continued physical activity after sports career was identified as a protective factor against anxiety and depression (Bäckmand et al., 2003; Bäckmand et al., 2009). Exercise has been shown to have therapeutic effects cognitively and emotionally, of which former players experiencing high levels of pain may not be able to achieve due to their difficulty with mobility (Ang & Gomez-Pinilla, 2007; Schwenk et al., 2007). Future studies examining potential protective factors of psychological distress of former elite athletes will help inform relevant clinical resources for this population.

Clinical Implications

Multiple studies highlighted the lack of care that was currently being received by former athletes (Guskiewicz et al., 2007; Hart et al., 2013; Kerr et al., 2012; Schwenk et al., 2007; van Ramele et al., 2017). Kerr and colleagues (2012) reported that of those previously diagnosed, 64% of players were still suffering from their depression. In one study of former NFL players, 75% of players who received a prior major depressive disorder diagnosis had not had treatment for their depression (Hart et al., 2013). Didehbani and colleagues (2013) also noted that of the 40% of former NFL players that were classified as mildly or moderately depressed; only 17% had received assessment or treatment for their depression.

As mentioned, higher self-reported pain and painful medical conditions experienced by athletes was associated with increased risk of experiencing psychological distress in retirement. Approximately 50% of people with chronic pain suffer from depression (Bair, Robinson, Katon, & Kroenke, 2003). Cognitive behavioral therapies (CBTs) have been shown to be effective treatments for depression and chronic pain, as well as associated substance use disorders (Hoffman, Papas, Chatkoff, & Kerns, 2007; Jhanjee, 2014; Ostelo et al., 2005). Research has highlighted the importance of assessing psychological variables when assessing injuries and considering treatment options (Bailey et al., 2010). Monitoring athlete-experienced pain, depressive symptoms, and substance misuse during playing career would enhance the ability to make recommendations for evidenced-based treatments in retirement.

Critical Appraisal and Directions for Future Research

Due to the fact that the majority of the current data in this review is cross-sectional, future studies should include a longitudinal design. Given the findings that the onset of mental health conditions occurs most commonly in adolescents and young adulthood, additional studies are needed for monitoring athlete’s psychological functioning from early adolescence before a pursued career in competitive sports, to late adulthood following sports retirement (Jones, 2013). Studies examining the temporality of psychological distress offered mixed results. Several studies demonstrated that younger age was significantly associated with psychological distress (Bäckmand et al., 2009; Esopenko et al., 2017; Kerr et al., 2012). A cross-sectional analysis indicated that a mental health composite score differed significantly by age, with mental health improving from the 24-and-under to the 35-to-44 group, and then decreasing in the 45-and-over group of former male and female intercollegiate athletes (Kerr, DeFreese, & Marshall, 2014). Contrastingly, Kerr and colleagues (2012) noted that among retired NFL players, a 9-year risk of a depression diagnosis decreased by 17% for every 10-year increase in the number of years retired from professional football, potentially highlighting an inverse relationship between psychological distress and years removed from sport. Additionally, three cohorts stratified by age (≤59 years, 60–69 years, ≥70 years) demonstrated a significant linear decrease in psychological distress with age, such that the ≤59 year old group reported significantly higher depressive distress than the two older cohorts (Bäckmand et al., 2009). As such, it is difficult to assess the temporality of psychological distress, including how factors related to sport, age, years involved in professional athletics, and years of retirement influence the trajectory of symptoms. Longitudinal studies would also help elucidate whether career termination and the factors associated with psychological distress presented in this review caused psychological distress in adulthood, or whether this distress is more likely attributable to predisposition to mental health conditions preceding a career in elite sports.

Further, future studies would benefit from more rigorous designs (e.g., using matched-control groups) and the use of reliable and valid measures of psychological functioning beyond several item screeners. More comprehensive measures will allow for a more accurate assessment of psychological distress as it pertains to Diagnostic and Statistical Manuel of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) criteria. The studies comprised in this review utilized 20 different measures of psychological distress. Greater consistency and uniformity amongst chosen outcome measures would help to more accurately assess the prevalence of psychological distress in studied populations. Current instruments used to measure psychological distress utilize differing screening criteria and rely on timing of assessment administration. Differences in employed measures have generated concerns with regard to the assessment criteria used to evaluate psychopathology, in addition to the use of diagnostic measures that may not be screening the same intended construct. Thus, results are difficult to compare across studies, and may lead to variable estimates of psychological distress (Sakakibara, Miller, Orenczuk, & Wolfe, 2009). In order to overcome the self-report and recall bias associated with the self-report measures of psychological distress, several studies utilized a self-report measure assessing for clinically diagnosed depression preceding study participation. Though examining diagnoses is a useful way to overcome bias, relying on questions assessing mental healthcare utilization prior to study conduction may have pitfalls due to the lack of help seeking identified in other articles. In the few studies that utilized a diagnostic interview administered by a licensed mental-healthcare professional, the prevalence of psychological distress was generally higher compared to assessing distress through other methods. Future studies may benefit from use of a study psychologist or psychiatrist to determine a more accurate prevalence of mental health distress amongst the study population.

Additionally, though several studies examined psychological distress in women, only one study was exclusively women, and the majority of the studies that comprised both men and women had a higher concentration of men. We strongly emphasize the importance of investigating psychological distress in populations of female athletes, or conducting studies examining the sex differences of psychological functioning in former athletes of similar sport, particularly due to the high likelihood of female athletes experiencing concussions. Psychological distress in childhood and adolescence, adverse life events, coping skills, psychological resilience, and protective factors may also affect the prevalence and correlates of such disorders (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001; Piccinelli & Wilkinson, 2000). In a study examining gender differences in a sample of current elite French athletes, Schaal and colleagues (2011) found that women were more likely to have at least one psychopathology, including higher prevalence of depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and sleep difficulties. These findings lend credence to the need of additional research examining retired women, as they may be more likely than their male counterparts to experience psychological distress in retirement.

Many of the studies examining psychological functioning in this population have examined the prevalence and correlates of depression only. Given the potentially debilitating nature of psychological distress, and the high prevalence of distress related to anxiety, depression, and substance misuse observed in the reviewed studies, additional research is needed to assess the severity of such conditions. Additionally, adjustment disorder is characterized as a group of symptoms such as stress, feeling sad or hopeless, and physical symptoms that can occur after an individual experiences a stressful event (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Given the robust literature demonstrating the difficult adjustment confronting athletes during the retirement transition process, studies assessing for clinically significant adjustment disorder during this period and after may help elucidate a more exact length of time that athletes cope with termination from sport, and estimate a more accurate duration for which adjustment problems may impact future psychological, occupational, and social functioning. Additionally, Wippert and Wippert (2008) found that approximately 20% of the former German National Ski Team reported clinical traumatic stress at 3 and 8 months retirement. Therefore, studies assessing for psychological distress in older elite athletes should consider evaluating symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Potential bias is also a concern in the literature examining determinants to psychological distress in retired elite athletes (Manley et al., 2017). Notably, studies evidencing null-relationships between examined risk factors and psychological outcomes are less likely to be published, leading to publication bias. Additionally, a recent systematic review by Manley and colleagues (2017) noted that one of the major limitations of published studies examining psychological outcomes among elite athletes is that many do not consider modifying factors, or the mediating/moderating effects of a third variable when assessing the relationship between adverse health events (i.e., concussions) and psychological distress. Though many studies controlled for important sociodemographic variables, this review evidenced potential factors that are often unaccounted for in multivariate models, such as pain, substance use/misuse, marital status, employment, financial status, social support, career satisfaction, retirement transition experience, relationships with players and coaches, and other medical conditions that may influence a retired athlete’s psychological functioning in late-adulthood.

Limitations

This systematic review has several limitations. First, the considerable diversity across study populations and measures made it difficult to use meta-analytic methods to aggregate data. Additionally, a lack of heterogeneity in studies examining psychological distress among retired elite athletes prohibited us from reviewing articles consisting of sports alternative to the one’s presented in this review. Furthermore, only English-language articles were included which may have influenced our results. However, sample populations were drawn from 17 different countries, resulting in geographically diverse samples. Additionally, because the primary aim of the study was to investigate prevalence and correlates of psychological distress among retired elite athletes, search criteria were limited to this terminology. Utilizing these specific criteria may have inhibited our ability to identify studies with mixed samples of current and retired athletes. Also, though our search criteria included a multitude of symptoms and conditions that comprise psychological distress, our search potentially limited our ability to identify articles examining alternative forms of distress among retired elite athletes. Lastly, though we identified consistent correlates of psychological distress, additional factors both observed less frequently in the review and others beyond the scope of this review may influence an athlete’s psychological functioning in later adulthood. Despite limitations, this review highlights the multifaceted nature of the sources of psychological functioning in retired elite athletes.

Conclusion

Though risk factors associated with psychological distress may be a function of a career in elite athletics, many studies suggested that the prevalence of distress among retired elite athletes was similar to that of the general population. Although differences in population, sport, and outcome measures make it difficult to generalize findings, it can be concluded that former elite athletes who experience adverse health consequences during their playing career may be at greater risk for experiencing psychological distress in retirement, while those who retire relatively unaffected from adverse health events go on to experience healthy lives with minimal psychological effects (Bäckmand et al., 2006; Brown et al., 2017; Casson et al., 2014; Gardner et al., 2017; Kuhn et al., 2017; Nicholas et al., 2007).

Results indicate that the prevalence of psychological distress ranged from 4.8% (depression) to 39.0% (depression/anxiety), with prevalence rates generally higher among athletes assessed by a study psychologist or other mental health professional. Psychological distress was associated with concussion history, more severe pain, greater prevalence of sustained injuries and osteoarthritis, psychological distress during career, and psychosocial difficulties in retirement. Continued physical activity into later adulthood may protect against psychological distress.

The association between brain trauma history and mood symptoms later in life was frequently discussed. Available data on retired athletes would suggest an association between concussion history and psychological distress (i.e., depressive symptoms); however, this finding was not universal and was at times a weaker predictor of psychological distress than other comorbid medical conditions and psychosocial factors. Additionally, these relationships have thus far been largely determined without consideration of other risk factors unrelated to brain trauma that are disproportionately prevalent in athlete populations. From a treatment standpoint, this is critically important. Specifically, chronic pain, sleep problems, substance use, physical inactivity, and poor adjustment to retirement, among other influences, are indeed treatable and represent important targets for intervention. The direct neurobiological effects of a history of brain trauma, repetitive or isolated, may no longer be “reversible” or modifiable at the point of retirement. We certainly encourage continued prevention and risk-mitigation efforts as they relate to sport-related brain injury, but also emphasize a focus on treating what can be treated after retirement via pharmacologic, psychotherapeutic, and lifestyle interventions. This requires multidisciplinary involvement and a coordinated plan of care that considers the many neurobiological and psychosocial influences of psychological function in retired athletes.