Abstract

Objective

To estimate the prevalence of HIV infection in persons released from Ontario prisons in 2010 using administrative health data, and to compare this observed prevalence with the expected prevalence based on the most recently available biological sampling data.Methods

We linked identifying data for all adults released from Ontario provincial prisons in 2010 with administrative health data, and applied a validated algorithm to determine the observed HIV prevalence. We calculated the expected HIV prevalence using 2003-2004 age stratum-specific data from a published study using salivary sampling. We calculated an indirect standardized prevalence ratio of the observed to expected prevalence and 95% confidence intervals. Finally, we conducted sensitivity analyses to adjust for the sensitivity of the algorithm to identify persons with HIV and for undiagnosed HIV infection.Results

Of 52,313 persons released from Ontario prisons in 2010, we identified 363 persons with HIV, for an observed prevalence of 0.69%. The expected prevalence was 2.38%. Standardized for age, we found a prevalence ratio of 0.29 (95% CI, 0.17-0.77). Sensitivity analyses adjusting for the algorithm's sensitivity and further adjusting for undiagnosed HIV infection produced standardized prevalence ratios of 0.30 and 0.38, respectively.Conclusion

Our findings suggest that a high proportion of persons with HIV recently released from provincial prisons either do not know they have HIV infection or do know about their infection but are not engaged in care. Interventions are required to screen people for HIV in prison and to link persons with care following release.Free full text

A comparison of the observed and expected prevalence of HIV in persons released from Ontario provincial prisons in 2010

Abstract

Objective

To estimate the prevalence of HIV infection in persons released from Ontario prisons in 2010 using administrative health data, and to compare this observed prevalence with the expected prevalence based on the most recently available biological sampling data.

Methods

We linked identifying data for all adults released from Ontario provincial prisons in 2010 with administrative health data, and applied a validated algorithm to determine the observed HIV prevalence. We calculated the expected HIV prevalence using 2003–2004 age stratum-specific data from a published study using salivary sampling. We calculated an indirect standardized prevalence ratio of the observed to expected prevalence and 95% confidence intervals. Finally, we conducted sensitivity analyses to adjust for the sensitivity of the algorithm to identify persons with HIV and for undiagnosed HIV infection.

Results

Of 52,313 persons released from Ontario prisons in 2010, we identified 363 persons with HIV, for an observed prevalence of 0.69%. The expected prevalence was 2.38%. Standardized for age, we found a prevalence ratio of 0.29 (95% CI, 0.17–0.77). Sensitivity analyses adjusting for the algorithm’s sensitivity and further adjusting for undiagnosed HIV infection produced standardized prevalence ratios of 0.30 and 0.38, respectively.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that a high proportion of persons with HIV recently released from provincial prisons either do not know they have HIV infection or do know about their infection but are not engaged in care. Interventions are required to screen people for HIV in prison and to link persons with care following release.

Résumé

Objectif

Estimer la prévalence des infections à VIH chez les personnes libérées de prison en Ontario en 2010 à l’aide de données administratives sur la santé, et comparer cette prévalence observée à la prévalence attendue d’après les données d’échantillonnage biologique les plus récentes.

Méthode

Nous avons jumelé les données d’identification de tous les adultes libérés des prisons ontariennes en 2010 avec les données administratives sur la santé et appliqué un algorithme validé pour déterminer la prévalence observée du VIH. Nous avons calculé la prévalence attendue du VIH à l’aide des données de 2003-2004 différenciées par strate d’âge tirées d’une étude publiée ayant utilisé des échantillons de salive. Nous avons calculé le ratio de prévalence standardisé indirect de la prévalence observée à la prévalence attendue et l’intervalle de confiance de 95 %. Enfin, nous avons mené des analyses de sensibilité pour tenir compte de la sensibilité de l’algorithme à repérer les personnes atteintes du VIH et les infections à VIH non diagnostiquées.

Résultats

Sur les 52 313 personnes libérées de prison en Ontario en 2010, nous avons trouvé 363 personnes atteintes du VIH, soit une prévalence observée de 0,69 %. La prévalence attendue était de 2,38 %. En standardisant les données selon l’âge, nous avons obtenu un ratio de prévalence de 0,29 (IC de 95 % : 0,17-0,77). Des analyses de sensibilité ajustées selon la sensibilité de l’algorithme, puis selon les infections à VIH non diagnostiquées ont produit des ratios de prévalence standardisés de 0,30 et de 0,38, respectivement.

Conclusion

Nos constatations indiquent qu’une proportion élevée de personnes atteintes du VIH récemment libérées des prisons provinciales ignorent qu’elles ont une infection à VIH ou savent qu’elles sont infectées, mais ne sont pas soignées. Des interventions sont nécessaires pour dépister le VIH en prison et pour diriger les personnes infectées vers les soins appropriés après leur libération.

Introduction

On an average day in Canada, there are about 140,000 adults under correctional supervision, with one third in prison and two thirds in a community program (Reitano 2017). The responsibility for the administration of adult correctional services is shared between federal and provincial and territorial governments. Provincial and territorial governments have jurisdiction over adults who are held in custody while awaiting trial or sentencing, sentenced to less than 2 years, or serving community sentences (Reitano 2017). Ontario has the highest count of adults in provincial prison, with about 8000 adults on an average day (Reitano 2017).

Risk behaviours for HIV are common among persons in prison in Canada. At the time of admission, most adults report recent drug use and about 10% report having injected drugs in the months before admission (Kouyoumdjian et al. 2016; Smith et al. 2013; Zakaria et al. 2010; A health care needs assessment of federal inmates in Burchell et al. 2003; Canada 2004; Courtemanche et al. 2018; Kouyoumdjian et al. 2014 Martin et al. 2005; Robinson & Mirabelli 1996; Wood et al. 2005). While in prison, sharing needles for injection drug use and sharing tattooing and piercing equipment present ongoing risks for the transmission of HIV (Kouyoumdjian et al. 2016; A health care needs assessment of federal inmates in Buxton et al. 2009; Canada 2004; Ford et al. 2000; Gagnon et al. 2007; Robinson & Mirabelli 1996; Thompson et al. 2011). While only a minority of persons report sexual activity while in prison, people commonly report sexual risk behaviours prior to admission, including a large number of lifetime sexual partners, sex with partners at increased risk of blood-borne infections (e.g., persons who inject drugs), inconsistent condom use and involvement in commercial sex (Burchell et al. 2003; Courtemanche et al. 2018; Dufour et al. 1996; Kouyoumdjian et al. 2016; Martin et al. 2005; Poulin et al. 2007; Robinson & Mirabelli 1996; Smith et al. 2013; Thompson et al. 2011; Zakaria et al. 2010).

These risk factors contribute to higher rates of HIV in persons in prison than in the overall Canadian population. Data from several sources demonstrate that the prevalence of HIV in people in jails and prisons in Canada is between five and over 25 times that of the general population (Bonnycastle & Villebrun 2011; Calzavara et al. 1995; Calzavara et al. 2007; Correctional Service Canada 2016; Courtemanche et al. 2018; De et al. 2004; Dufour et al. 1996; Ford et al. 1995; Poulin et al. 2007; Rothon et al. 1994) (Table (Table1),1), which was estimated as 0.18% in 2014. (Public Health Agency of Canada 2016; Statistics Canada 2014).

Table 1

Estimates from prior studies of HIV prevalence in Canadian federal or provincial prison populations

| Study | Year | Population | Proportion positive | Prevalence % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rothon et al. (1994) | 1992 | Adult men and women volunteers who anonymously tested positive for HIV antibodies in saliva from all provincial prisons in British Columbia | 28/2482 | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) |

| Calzavara et al. (1995) | 1993 | Adult men and women who anonymously tested positive for HIV antibodies in routinely collected urine samples in remand facilities in Ontario | 107/10,503 | 1.0 |

| Ford et al. (1995) | 1994 | Adult female volunteers who tested positive for HIV antibodies in blood at the federal Prison for Women, Kingston, Ontario | 1/113 | 0.9 |

| Dufour et al.(1996) | 1994 | Men and women volunteers who tested positive for HIV in saliva at the Quebec Detention Centre | 20/651 | 3.2 |

| De et al. (2004) | 2002 | Men and women volunteers who tested positive for HIV in serum in all 53 Canadian federal penitentiaries | 248/12,426 | 2.0 (1.8–2.3) |

| Bonnycastle and Villebrun (2011) | 2002 | Males who self-reported testing seropositive after an HIV test, out of all tested for HIV, in one federal prison | 8/169 | 4.7 |

| Poulin et al. (2007) | 2003 | Men and women who tested positive for HIV antibodies in saliva in 7 of the 17 provincial prisons in Quebec | 54/1607 | 3.4 |

| Calzavara et al. (2007) | 2003–2004 | Adult men and women who anonymously tested positive for HIV antibodies in saliva in 13 of the 28 remand facilities in Ontario | 31.1*/1528 | 2.0 (1.3–2.8) |

| Correctional Service Canada (2016) | 2005–2012 | Persons 17 and older with a positive serology result, on antiretroviral treatment, or self-reported positive status in the CSC Web-enabled Infectious Disease Surveillance System | 429/24,353 | 1.76 |

| Courtemanche et al. (2018) | 2014–2015 | Persons in provincial detention centres in Quebec | 26†/1565 | 1.64† |

*Weighted proportion

†Estimated based on percentages provided in the published manuscript (Courtemanche et al. 2018)

Understanding the prevalence of HIV in persons in prison is important for several reasons. First, achievement of the UNAIDS targets to eliminate HIV is predicated on 90% of persons with HIV infection being aware of their diagnosis (Public Health Agency of Canada 2016). Limited evidence indicates that a substantial proportion of people with HIV in prison are unaware of their infection. A 2015 systematic review of studies in Canada and the United States found that only 78−79% of people with HIV in jails and prisons were aware of their diagnosis (Iroh et al. 2015). In voluntary testing studies of people in provincial custody in Quebec, 20% of persons with HIV did not know about their infection in 2003, (Poulin et al. 2007), and in 2014 and 2015, 10.5% of people with HIV who injected drugs and 85.7% of people with HIV who did not inject drugs were unaware of their HIV infection (Courtemanche et al. 2018). We need an updated prevalence estimate for persons in prison in Ontario to assess current performance relative to this first UNAIDS target. Second, rates of linkage to and retention in HIV care are considerably lower among formerly imprisoned people with HIV relative to the general population of people with HIV (Iroh et al. 2015). Estimating the prevalence of HIV, as well as the subsequent steps of the HIV care cascade, is necessary for developing interventions to improve linkage to care in prison and post-release.

Prior to our research group’s current research (Khanna et al. 2018), the most recent HIV prevalence for persons in Ontario prisons was estimated in 2004 using biological sampling (Table (Table1)1) (Calzavara et al. 2007). The purpose of the current study is to compare the observed prevalence of HIV in this population using administrative health data with the expected prevalence based on the most recently available biological sampling data from 2004.

Methods

Study design and setting

Our study population included all persons released from provincial correctional facilities in Ontario, Canada, in 2010. Provincial correctional facilities in Canada house persons who are admitted to prison prior to sentencing, persons sentenced to less than 2 years in prison, persons sentenced to 2 years or longer prior to being transferred to a federal prison and those in temporary detention for other reasons (Reitano 2017). We use the term “provincial prison” or “Ontario prison” to represent all provincial facilities, including jails, detention centres and correctional centres in Ontario.

In Ontario, the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services oversees the administration and delivery of services in provincial prisons, including healthcare. Typically, a nurse conducts an initial assessment of each person at the time of admission, then people see a physician routinely within weeks of admission or sooner if medically indicated. Ongoing or episodic care is subsequently provided based on identified need by healthcare staff or through patient request. People who are released within a short period may not see a physician while in prison. Consistent with healthcare for Ontario residents in the community, hospitalizations and medically necessary physician services for persons in provincial prison are paid for through the public health insurance system (the Ontario Health Insurance Plan, or OHIP).

There is currently no universal HIV screening policy in provincial prison in Ontario. Practices may vary by institution, but in general, people can request testing at the time of admission or subsequently in encounters with physicians or other healthcare staff, or providers may recommend testing.

Study cohort

We used data from the Ontario Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services (MCSCS) on all adults released from provincial prison in 2010, which had been linked with administrative health data at ICES with a high linkage rate (97.4%) (Kouyoumdjian et al. 2018).

Data sources

Socio-demographic information: We accessed data on neighbourhood income quintile for each person using the postal code at the time of prison admission from the Registered Persons Database, a registry of all persons eligible for health insurance (OHIP) in Ontario.

Outcome: For observed HIV prevalence, we identified persons with HIV by applying a validated case-finding algorithm to administrative data at ICES (Antoniou et al. 2011), as reported in a related study on the healthcare utilization of people with HIV who were released from provincial prison in 2010 (Khanna et al. 2018). The algorithm classified persons as diagnosed with HIV if they had three or more physician OHIP claims for HIV-related visits over a 3-year period, with a sensitivity of 96.2% (95% CI, 95.2–97.9) and specificity of 99.6% (95% CI, 99.1–99.8) in the general population of persons with HIV infection. We applied the algorithm retrospectively from the date of initial release from provincial prison in 2010.

For expected HIV prevalence, we accessed published prevalence data from a study that was conducted by Calzavara et al. in 2003 and 2004 (Calzavara et al. 2007). In that study, investigators collected saliva samples from 1942 participants in 13 of 28 provincial prisons. The prison sites selected were representative of the population in provincial prison in terms of age, gender and geographic region, and the participation rate was 84.3%.

Analysis

We described socio-demographic characteristics of all adults released from provincial prison in 2010 by HIV status on the date of initial release in 2010.

We conducted indirect standardization of HIV prevalence. For the observed number of persons with HIV, we used the number of individuals with HIV infection released from Ontario provincial prisons in 2010 after applying the case-finding algorithm described above. We calculated the expected number of persons with HIV as the sum of the products of each age stratum-specific prevalence of HIV infection from the study by Calzavara et al. (2007) and the number of persons released from provincial prison in 2010. We defined the indirect standardized prevalence ratio as the ratio of the observed prevalence to the expected prevalence. We calculated 95% confidence intervals in Stata. We were not able to calculate sex-stratified standardized prevalence ratios since sex-specific HIV prevalence data were not available for age strata in the study by Calzavara et al. (2007).

We conducted two sensitivity analyses. First, we divided the observed estimate by the sensitivity of the case-finding algorithm (Antoniou et al. 2011) for identifying persons with HIV. Second, we adjusted the observed estimate for the algorithm’s sensitivity and for individuals who do not know they are infected with HIV, based on the PHAC estimate that 20% (range 13–27%) of people with HIV do not know their infection status (Public Health Agency of Canada 2016). These adjustments account for the algorithm’s less than 100% sensitivity and the assumption that individuals who do not know they have HIV infection would not seek HIV-related care, and so would not be detected by the algorithm, respectively.

Results

We achieved valid data linkage for 52,313 persons who were released from Ontario provincial prisons in 2010 (Table (Table2)2) (Kouyoumdjian et al. 2018). The majority of persons had been in provincial prison prior to the admission leading to the initial release in 2010, and the majority of persons spent 1 week or longer in provincial prison during the admission leading to the initial release in 2010.

Table 2

Demographic characteristics of individuals released from Ontario provincial prisons in 2010, by HIV status on initial release in 2010

| Characteristic | HIV-positive persons N  = = 363 363n (%) | HIV-negative persons N  = = 51,950 51,950n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15–29 | 57 (15.7) | 22,024 (42.4) |

| 30–39 | 121 (33.3) | 13,172 (25.4) | |

| 40–49 | 144 (39.7) | 11,062 (21.3) | |

≥ 50 50 | 41 (11.3) | 5692 (11.0) | |

| Sex | Female | 62 (17.1) | 6295 (12.1) |

| Male | 301 (82.9) | 45,655 (87.9) | |

| Neighbourhood income quintile | Missing | 9 (2.5) | 3186 (6.1) |

| 1 | 156 (43.0) | 19,017 (36.6) | |

| 2 | 75 (20.7) | 11,005 (21.2) | |

| 3 | 53 (14.6) | 8109 (15.6) | |

| 4 | 38 (10.5) | 6181 (11.9) | |

| 5 | 32 (8.8) | 4452 (8.6) | |

| Time in provincial prison, index admission* | < 1 week 1 week | 107 (29.5) | 21,036 (40.5) |

1 week to < 2 weeks 2 weeks | 59 (16.3) | 6515 (12.5) | |

2 weeks to < 4 weeks 4 weeks | 44 (12.1) | 5678 (10.9) | |

4 to < 12 weeks 12 weeks | 72 (19.8) | 8819 (17.0) | |

≥ 12 weeks 12 weeks | 81 (22.3) | 9902 (19.1) | |

| Number of admissions to provincial prison between 2005 and index admission* | 0 | 83 (22.9) | 22,885 (44.1) |

| 1 | 42 (11.6) | 8559 (16.5) | |

| 2 | 29 (8.0) | 5595 (10.8) | |

| 3 | 21 (5.8) | 3971 (7.6) | |

| 4 | 27 (7.4) | 2927 (5.6) | |

≥ 5 5 | 161 (44.4) | 8013 (15.4) | |

*Index admission is defined as the period in custody leading to initial release in 2010

Applying the validated algorithm to this population, we identified 363 persons with HIV infection, of whom 17.1% were women. The overall observed HIV prevalence was 0.69% (Table (Table3),3), and the prevalence was 0.65% in men and 0.98% in women. The total expected number of cases of HIV in the 2010 cohort after applying and summing age-stratum-specific prevalence percentages was 1244 (95% CI, 474–2132), equivalent to a prevalence of 2.38%. The indirect age-standardized prevalence ratio was 0.29 (95% CI, 0.17–0.77).

Table 3

Observed and expected cases of HIV in persons released from Ontario provincial prison in 2010 by age stratum and age-standardized prevalence ratio

| Age group (years) | Persons released from prison in 2010 | Observed* | Expected† | Age-standardized prevalence ratio‡ (95%CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Prevalence (%) | Cases (95% CI) | Prevalence (95% CI) | |||

≤ 29 29 | 22,081 | 57 | 0.26 | 44.2 (2.2–198.7) | 0.2 (0.01–0.9) | – |

| 30–39 | 13,293 | 121 | 0.91 | 358.9 (159.5–558.3) | 2.7 (1.2–4.2) | – |

| 40–49 | 11,206 | 144 | 1.29 | 336.2 (134.5–549.1) | 3.0 (1.2–4.9) | – |

≥ 50 50 | 5733 | 41 | 0.72 | 504.5 (177.7–825.6) | 8.8 (3.1–14.4) | – |

| Total | 52,313 | 363 | 0.69 | 1243.8 (473.9–2131.7) | 2.4 (1.3–2.8) | 0.29 (0.17–0.77) |

*Applying a validated algorithm to administrative health data at ICES (Antoniou et al. 2011)

†Data on prevalence from a biological sampling study by Calzavara et al. in 2003/2004 (Calzavara et al. 2007). Number of expected cases derived by multiplying age-specific prevalence rates from Calzavara et al. by the number of persons released from prison in 2010

‡For men and women combined

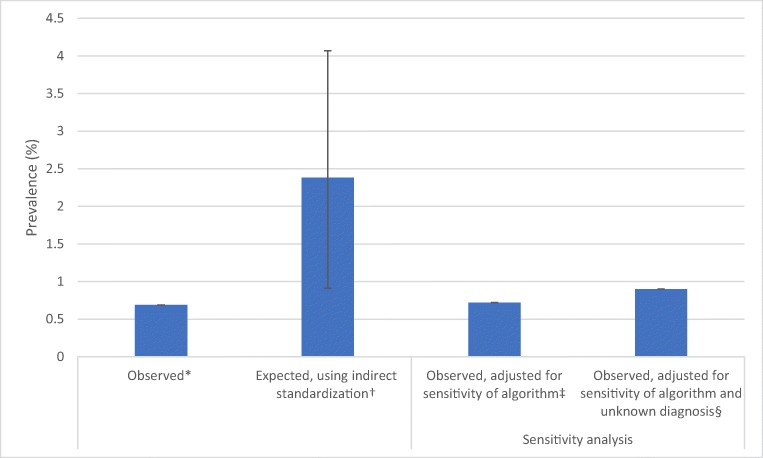

The observed HIV prevalence accounting for the sensitivity of the case-finding algorithm (i.e., 96.2%) was 0.72% (Fig. 1). Further adjustment for the expected number of individuals who do not know they are infected with HIV, which is estimated to be 20% (Public Health Agency of Canada 2016), increased the prevalence estimate to 0.90%. The indirect age-standardized prevalence ratios increased to 0.30 (95% CI, 0.27–0.34) and 0.38 (95% CI, 0.35–0.42), respectively, using the prevalences calculated from the sensitivity analyses.

Prevalence of HIV in adults released from Ontario prisons in 2010, according to method of generating estimate. *Applying a validated algorithm to administrative health data at ICES (Antoniou et al. 2011) †From a biological sampling study by Calzavara et al. (2007) in 2004. ‡Sensitivity of the algorithm was 96.2% (Antoniou et al. 2011) §PHAC estimates that 20% of persons infected with HIV do not know they have HIV infection (Public Health Agency of Canada 2016)

Discussion

Using administrative health data, we estimated that 0.69% of persons released from Ontario prisons in 2010 were living with HIV, substantially lower than the expected prevalence of 2.38%. Considering the HIV care cascade, our expected prevalence reflects the number of persons infected with HIV, and the observed prevalence reflects the number of persons diagnosed with HIV and successfully linked to care. We found an indirect standardized prevalence ratio of HIV infection of 0.29 (95% CI, 0.17–0.77), meaning a validated algorithm identified less than one third of the persons with HIV that we would expect to identify based on the most recent biological sampling study (Calzavara et al. 2007; Antoniou et al. 2011). Sensitivity analyses adjusting for the sensitivity of the case-finding algorithm (Antoniou et al. 2011) and for individuals who do not know they are infected with HIV did not substantially alter the standardized prevalence ratio. The observed HIV prevalence was substantially lower than any estimate from prior studies conducted in prisons in Canada (see Table Table1).1). The observed and expected HIV prevalences were higher than the prevalences in the general Canadian population by four and 13 times, respectively (Public Health Agency of Canada 2016; Statistics Canada 2014).

Our study has several strengths. The sample was large and population-based, as we included all adults released from provincial prison in 2010 and achieved high rates of linkage to administrative health data. To generate the observed cases, we used a validated, sensitive and specific case-finding algorithm for identifying individuals with HIV infection from Ontario administrative health data (Antoniou et al. 2011). For the expected prevalence, we used data from a representative study sample of persons in Ontario provincial prisons, such that the population was comparable to our study population (Calzavara et al. 2007). The use of indirect standardization enabled an appropriately age-adjusted comparison of the observed and expected HIV prevalences in our study cohort. We think that the finding of a substantially lower HIV prevalence identified in administrative health data compared with biological sampling is likely generalizable to other jurisdictions that have not implemented universal HIV screening in prison.

Our study has several potential limitations. The algorithm used to identify persons with HIV was validated in primary care settings with a high prevalence of HIV of 23.1% (Antoniou et al. 2011), which was higher than that observed in this or previous studies of HIV prevalence in federal or provincial prisons (Table (Table1).1). Applying the algorithm in a population with a lower prevalence may increase the number of false positives, leading to overestimating the prevalence and moving the standardized prevalence ratio closer to 1. Administrative health data would not identify certain people with HIV, including recent immigrants who have not accessed provincially funded care, people who had been in federal prison (during which time they would not have accessed provincially funded healthcare) and people who had been diagnosed with HIV but were not accessing care. In Ontario, anonymous diagnostic testing for HIV is available at select clinics in the community, but not in prisons, and persons who tested positive anonymously may not have gone on to have nominal HIV testing or have accessed care for HIV. Any of these issues would lead to misclassifying people with HIV as not having HIV in our study, which would lead to an underestimate of the observed prevalence and move the standardized prevalence ratio away from the null. Laboratory and public health reporting data would identify more people who had been diagnosed with HIV infection, but we did not have access to those data in this study.

The finding of a standardized HIV prevalence ratio of 0.29 can have several possible interpretations with important implications for public health professionals, clinicians and policymakers. First, the true prevalence in 2003−2004 could have been lower than the prevalence identified in the Calzavara et al. study. We think this is unlikely given the large, representative sample used and rigorous methods of that study, as well as the consistency of the study findings with previous Canadian studies of HIV prevalence. Second, it is possible that the true HIV prevalence in persons in provincial prison decreased between 2003−2004 and 2010. A recent study in provincial correctional facilities in Quebec found no significant difference in HIV prevalence in men between 2003 and 2014−2015, though there was a significant decrease in HIV prevalence in women (Courtemanche et al. 2018); we note that women represent only 12% of persons released from provincial prison in Ontario. We think it is unlikely that the HIV prevalence decreased substantially over this period in people in this population in Ontario in the absence of significant policy and program changes in provincial prison and considering trends in the general Canadian population (Public Health Agency of Canada 2014), and especially unlikely to explain a 71% decline in HIV prevalence. If we assume the Calzavara et al. prevalence was accurate and our expected prevalence closely approximates the true prevalence of HIV in persons in Ontario prisons, several other issues may explain the standardized prevalence ratio we found. One possible explanation is that biological sampling identifies individuals who do not know they are infected with HIV, who would not be identified in administrative health data. Adjusting our estimate for the algorithm’s sensitivity and the expected number of individuals who might not know they have HIV infection, however, only increased the standardized prevalence ratio to 0.38. This suggests that the enhanced detection of biological sampling is not the sole factor and that the proportion of persons released from provincial prisons with HIV infection who do not know their status could be much higher than that in the general population. Another possible explanation is that persons with HIV infection in provincial prisons who know their HIV status may be less likely than the general population to access care related to their HIV infection. This would decrease the sensitivity of administrative health data-based approaches to identifying persons with HIV. HIV cascade of care estimates in persons released from prisons in the US and Canada compared with the general population provide support for this interpretation (Iroh et al. 2015). In related research, we found no difference in the median time to accessing HIV-specific ambulatory care for people after prison release compared with people in the general population (Khanna et al. 2018), though those data would not include persons with HIV who did not meet the algorithm’s threshold for number of times accessing care for HIV within 3 years (Antoniou et al. 2011).

Conclusion

The prevalence of HIV infection continues to be higher in persons in prison in Ontario than in the general population. The findings of our study suggest that high proportions of persons with HIV recently released from provincial prisons either do not know they have HIV infection or know about their infection but are not engaged in care, and that these proportions are much higher than those in the general population. Our study has explored the first two steps of the HIV care cascade. Describing all steps of the HIV care cascade for persons in prison in Ontario will form a critical research foundation for understanding inequities in HIV care for this population and for evaluating the performance of interventions to close health equity gaps. Time spent in prison presents an important opportunity for diagnosing HIV, linking people with care, and implementing evidence-based interventions to support indicated care (Iroh et al. 2015; Rich et al. 2013; Kamarulzaman et al. 2016; Rich et al. 2016; World Health Organization 2016). Prevention strategies should be adapted to be accessible for people with short lengths of stay, which are common in provincial prison, for example, providing universal opt-out testing on admission with low barrier testing options such as point-of-care and dried blood spot testing (Kamarulzaman et al. 2016). Enhanced HIV diagnosis and better understanding of barriers to accessing HIV services for persons in provincial prison are needed in order to meet the UNAIDS targets for the HIV care cascade (Public Health Agency of Canada 2016).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

7/31/2019

The Acknowledgements section was inadvertently omitted from this article; it appears in its entirety below.

References

- A health care needs assessment of federal inmates in Canada. [Supplement] Canadian Journal of Public Health 2004; 95 Suppl 1, S9–63. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract]

- Antoniou T, Zagorski B, Loutfy MR, Strike C, Glazier RH. Validation of case-finding algorithms derived from administrative data for identifying adults living with human immunodeficiency virus infection. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21748. 10.1371/journal.pone.0021748. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnycastle KD, Villebrun C. Injecting risk into prison sentences: a quantitative analysis of a prisoner-driven survey to measure HCV/HIV seroprevalence, risk practices, and viral testing at one Canadian male federal prison. Prison Journal. 2011;91(3):325–346. 10.1177/0032885511409893. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Burchell AN, Calzavara LM, Myers T, et al. Voluntary HIV testing among inmates: sociodemographic, behavioral risk, and attitudinal correlates. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: JAIDS. 2003;32(5):534–541. 10.1097/00126334-200304150-00011. [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton JA, Rothon D, Durigon M, et al. Hepatitis C and HIV prevalence using oral mucosal transudate, and reported drug use and sexual behaviours of youth in custody in British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2009;100(2):121–124. 10.1007/BF03405520. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Calzavara LM, Major C, Myers T, et al. The prevalence of HIV-1 infection among inmates in Ontario, Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 1995;86(5):335–339. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Calzavara L, Ramuscak N, Burchell AN, et al. Prevalence of HIV and hepatitis C virus infections among inmates of Ontario remand facilities. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2007;177(3):257–261. 10.1503/cmaj.060416. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Correctional Service Canada. (2016). Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Age, Gender and Indigenous Ancestry. https://www.cscscc.gc.ca/publications/005007-3034-eng.shtml. (accessed September 24 2018).

- Courtemanche Y, Poulin C, Serhir B, Alary M. HIV and hepatitis C virus infections in Quebec’s provincial detention centres: comparing prevalence and related risky behaviours between 2003 and 2014-2015. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2018;109(3):353–361. 10.17269/s41997-018-0047-4. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- De P, Connor N, Bouchard F, Sutherland D. HIV and hepatitis C virus testing and seropositivity rates in Canadian federal penitentiaries: a critical opportunity for care and prevention. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology. 2004;15(4):221–225. 10.1155/2004/695483. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour A, Alary M, Poulin C, et al. Prevalence and risk behaviours for HIV infection among inmates of a provincial prison in Quebec City. AIDS. 1996;10(9):1009–1015. 10.1097/00002030-199610090-00012. [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ford PM, White C, Kaufmann H, et al. Voluntary anonymous linked study of the prevalence of HIV infection and hepatitis C among inmates in a Canadian federal penitentiary for women. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1995;153(11):1605–1609. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ford PM, Pearson M, Sankar-Mistry P, Stevenson T, Bell D, Austin J. HIV, hepatitis C and risk behaviour in a Canadian medium-security federal penitentiary. Queen’s University HIV Prison Study Group. Qjm. 2000;93(2):113–119. 10.1093/qjmed/93.2.113. [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon H, Godin G, Alary M, Lambert G, Lambert LD, Landry S. Prison inmates’ intention to demand that bleach be used for cleaning tattooing and piercing equipment. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2007;98(4):297–300. 10.1007/BF03405407. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Iroh, P. A., Mayo, H., & Nijhawan, A. E. (2015). The HIV care cascade before, during, and after incarceration: a systematic review and data synthesis. American Journal of Public Health, 105(7), e5–e16. [Abstract]

- Kamarulzaman A, Reid SE, Schwitters A, et al. Prevention of transmission of HIV, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis in prisoners. Lancet. 2016;388(10049):1115–1126. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30769-3. [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna S, Leah J, Fung K, Antoniou T, Kouyoumdjian F. (2019). Health care utilization by people with HIV on release from provincial prison in Ontario, Canada in 2010: a retrospective cohort study. AIDS Care, 31(7), 785-792. [Abstract]

- Kouyoumdjian F, Calzavara LM, Kiefer L, Main C, Bondy SJ. Drug use prior to incarceration and associated socio-behavioural factors among males in a provincial correctional facility in Ontario, Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2014;105(3):198–202. 10.17269/cjph.105.4193. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kouyoumdjian F, Schuler A, Matheson FI, Hwang SW. Health status of prisoners in Canada: narrative review. Canadian Family Physician. 2016;62(3):215–222. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kouyoumdjian FG, Cheng SY, Fung K, et al. The health care utilization of people in prison and after prison release: a population-based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0201592. 10.1371/journal.pone.0201592. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RE, Gold F, Murphy W, Remple V, Berkowitz J, Money D. Drug use and risk of bloodborne infections: a survey of female prisoners in British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2005;96(2):97–101. 10.1007/BF03403669. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin C, Alary M, Lambert G, et al. Prevalence of HIV and hepatitis C virus infections among inmates of Quebec provincial prisons. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2007;177(3):252–256. 10.1503/cmaj.060760. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada 2014. Summary: estimates of HIV incidence, prevalence and proportion undiagnosed in Canada. 2015. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/summary-estimates-hiv-incidence-prevalence-proportion-undiagnosed-canada-2014.html (accessed September 24 2018).

- Public Health Agency of Canada 2016. Summary: measuring Canada’s progress on the 90-90-90 HIV targets, 2016

- Reitano J. 2017. Adult correctional statistics in Canada, 2015/2016. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2017001/article/14700-eng.htm (accessed October 18 2018).

- Rich JD, DiClemente R, Levy J, et al. Correctional facilities as partners in reducing HIV disparities. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2013;63(Suppl 1):S49–S53. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318292fe4c. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rich JD, Beckwith CG, Macmadu A, et al. Clinical care of incarcerated people with HIV, viral hepatitis, or tuberculosis. Lancet. 2016;388(10049):1103–1114. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30379-8. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D, Mirabelli, L. 1996. Summary of findings of the 1995 CSC National Inmate Survey. http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/research/b14e-eng.shtml (accessed November 18 2014).

- Rothon DA, Mathias RG, Schechter MT. Prevalence of HIV infection in provincial prisons in British Columbia. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1994;151(6):781–787. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Cox K, Poon C, Stewart D 2013. McCreary Centre Society. Time Out III: a profile of BC youth in custody. http://www.mcs.bc.ca/pdf/Time_Out_III.pdf (accessed December 1 2014).

- Statistics Canada 2014. Canada’s population estimates: age and sex, 2014. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/140926/dq140926b-eng.htm (accessed October 18 2018).

- Thompson J, Zakaria D, Grant B 2011. Aboriginal men: a summary of the findings of the 2007 National Inmate Infectious Diseases and Risk-Behaviours Survey, R-237. http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/research/005008-0237-eng.shtml (accessed June 16 2014).

- Wood E, Li K, Small W, Montaner JS, Schechter WT, Kerr T. Recent incarceration independently associated with syringe sharing by injection drug users. Public Health Reports. 2005;120(2):150–156. 10.1177/003335490512000208. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization 2016. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations, updated version. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/246200/9789241511124-annexes-eng.pdf?sequence=5 (accessed September 24 2018). [Abstract]

- Zakaria D, Thompson JM, Jarvis A, Borgatta F. 2010. Summary of emerging findings from the 2007 National Inmate Infectious Diseases and Risk-Behaviours Survey. http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/005/008/092/005008-0211-01-eng.pdf (accessed June 16 2014).

Articles from Canadian Journal of Public Health = Revue Canadienne de Sant

Publique are provided here courtesy of Springer

Publique are provided here courtesy of SpringerFull text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-019-00233-0

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc6964370?pdf=render

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Health care utilization by people with HIV on release from provincial prison in Ontario, Canada in 2010: a retrospective cohort study.

AIDS Care, 31(7):785-792, 12 Dec 2018

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 30541330

90-90-90 for everyone?: Access to HIV care and treatment for people with HIV who experience imprisonment in Ontario, Canada.

AIDS Care, 32(9):1168-1176, 15 Oct 2019

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 31615271

Primary care utilization in people who experience imprisonment in Ontario, Canada: a retrospective cohort study.

BMC Health Serv Res, 18(1):845, 09 Nov 2018

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 30413165 | PMCID: PMC6234797

HIV in prison in low-income and middle-income countries.

Lancet Infect Dis, 7(1):32-41, 01 Jan 2007

Cited by: 145 articles | PMID: 17182342

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

2,9,10

2,9,10