Abstract

Free full text

Characterization of non-typhoidal Salmonella isolates from children with acute gastroenteritis, Kolkata, India, during 2000–2016

Abstract

Non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) is an important cause of acute gastroenteritis in children. The study was undertaken to determine the isolation rate, serovar prevalence, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) profiles, and molecular subtypes of NTS from a hospital-based diarrheal disease surveillance in Kolkata, India. Rectal swabs were collected from children (< 5 years of age) with acute gastroenteritis from 2000 to 2016. Samples were processed following standard procedures for identification of NTS. The isolates were tested for antimicrobial susceptibility, AMR genes, plasmid profiles, multilocus sequence typing (MLST), and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) subtypes. A total of 99 (1.0%) Salmonella isolates were recovered from 9957 samples processed. Of the 17 Salmonella serovars identified, S. Worthington (33%) was predominant followed by S. Enteritidis (13%), S. Typhimurium (12%), and others. The isolates showed high resistance towards nalidixic acid (43%), ampicillin (34%), third-generation cephalosporins (32%), and azithromycin (25%), while low resistance was observed for fluoroquinolones (2%). Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production (blaCTX-M-15 and blaSHV-12 genes) and azithromycin resistance (mphA gene) were common in S. Worthington, while fluoroquinolone resistance (gyrA and parC mutations) was found in S. Kentucky. Diverse plasmid profiles were observed among the isolates. PFGE analysis identified genetically related strains of each serovar in circulation. MLST also revealed phylogenetically clonal isolates of which S. Worthington ST592 and ciprofloxacin-resistant S. Kentucky ST198 were not reported earlier from India. NTS resistant to current drugs of choice poses a potential public health problem. Continuous monitoring of AMR profiles and molecular subtypes of NTS serovars is recommended for controlling the spread of resistant organisms.

5 years of age) with acute gastroenteritis from 2000 to 2016. Samples were processed following standard procedures for identification of NTS. The isolates were tested for antimicrobial susceptibility, AMR genes, plasmid profiles, multilocus sequence typing (MLST), and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) subtypes. A total of 99 (1.0%) Salmonella isolates were recovered from 9957 samples processed. Of the 17 Salmonella serovars identified, S. Worthington (33%) was predominant followed by S. Enteritidis (13%), S. Typhimurium (12%), and others. The isolates showed high resistance towards nalidixic acid (43%), ampicillin (34%), third-generation cephalosporins (32%), and azithromycin (25%), while low resistance was observed for fluoroquinolones (2%). Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production (blaCTX-M-15 and blaSHV-12 genes) and azithromycin resistance (mphA gene) were common in S. Worthington, while fluoroquinolone resistance (gyrA and parC mutations) was found in S. Kentucky. Diverse plasmid profiles were observed among the isolates. PFGE analysis identified genetically related strains of each serovar in circulation. MLST also revealed phylogenetically clonal isolates of which S. Worthington ST592 and ciprofloxacin-resistant S. Kentucky ST198 were not reported earlier from India. NTS resistant to current drugs of choice poses a potential public health problem. Continuous monitoring of AMR profiles and molecular subtypes of NTS serovars is recommended for controlling the spread of resistant organisms.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s42770-019-00213-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Gastroenteritis is one of the leading causes of morbidity among the children throughout the world, especially in developing countries with an estimated 1.87 million deaths annually in children < 5 years of age [1]. In India, diarrhea is third leading cause of childhood mortality and responsible for 13% of all deaths per year in children under 5 years [2]. Among the bacterial etiology of diarrhea, non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) is one of the major zoonotic pathogens reported in children, transmitted by ingestion of contaminated food or water and by contact with animals or poultry [3–5]. Among more than 2500 Salmonella serovars, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) and S. Enteritidis are two most common serotypes associated with NTS gastroenteritis in children across the globe [5–13]. Low immunity, immature endogenous bowel flora, and gastric hypoacidity in children predispose to NTS infection [5, 13, 14]. NTS gastroenteritis is usually self-limiting and may be accompanied by fever, abdominal cramps, nausea, and vomiting. Hospitalization may be required for severe cases [5]. The global burden of NTS gastroenteritis is high with around 93.8 million cases and 155,000 deaths reported each year [5, 13]. Bacteremia, meningitis, osteomyelitis, and pneumonia are the most common systemic complications reported in 2–47% children with NTS gastroenteritis. Chronic carriage (excretion of NTS >

5 years of age [1]. In India, diarrhea is third leading cause of childhood mortality and responsible for 13% of all deaths per year in children under 5 years [2]. Among the bacterial etiology of diarrhea, non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) is one of the major zoonotic pathogens reported in children, transmitted by ingestion of contaminated food or water and by contact with animals or poultry [3–5]. Among more than 2500 Salmonella serovars, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) and S. Enteritidis are two most common serotypes associated with NTS gastroenteritis in children across the globe [5–13]. Low immunity, immature endogenous bowel flora, and gastric hypoacidity in children predispose to NTS infection [5, 13, 14]. NTS gastroenteritis is usually self-limiting and may be accompanied by fever, abdominal cramps, nausea, and vomiting. Hospitalization may be required for severe cases [5]. The global burden of NTS gastroenteritis is high with around 93.8 million cases and 155,000 deaths reported each year [5, 13]. Bacteremia, meningitis, osteomyelitis, and pneumonia are the most common systemic complications reported in 2–47% children with NTS gastroenteritis. Chronic carriage (excretion of NTS > 1 year) is common in children <

1 year) is common in children < 5 years which play an important role in spread of the organism in the community and maintain a reservoir of infection [5, 14]. Several foodborne and nosocomial outbreaks of gastroenteritis have been reported among children [15–18].

5 years which play an important role in spread of the organism in the community and maintain a reservoir of infection [5, 14]. Several foodborne and nosocomial outbreaks of gastroenteritis have been reported among children [15–18].

Antimicrobial therapy is indicated only for severe or invasive salmonellosis. Indiscriminate use of antimicrobials in both humans and veterinary has led to emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) to both conventional (ampicillin, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and co-trimoxazole) and newer (third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and azithromycin) drugs in NTS, which is a global concern [4, 6–13, 19–23]. Since the resistance rate in NTS varies with different serotypes and in various geographical regions, knowledge on prevalent serovars and their AMR profiles is useful in formulating appropriate treatment (empirical) guidelines and controlling spread of the organisms in the community. Mobile genetic elements like plasmids and integrons harboring resistance genes play an important role in AMR dissemination. Among these, Class 1 integron is the common type found in antibiotic-resistant NTS and reported from different countries [24–27].

Molecular subtyping of bacteria is an invaluable tool for determining relatedness among the bacterial isolates in epidemiological surveillance and in outbreak investigation [28, 29]. Plasmid profiling is a common typing method used for discriminating Salmonella serovars and subtypes within the serovars. It is also useful in tracking the transmission of AMR genes among bacteria. However, the method has low reproducibility and is not suitable for typing plasmid-less bacteria [9, 28]. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) is considered as gold standard for Salmonella subtyping but standardization of protocol is necessary to ensure reproducibility. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) is a DNA sequence–based method using several housekeeping genes which is more suitable in studying the evolutionary relationships among the isolates. The MLST data is unambiguous, stable, and easily comparable among various labs [28–30].

Epidemiology of NTS gastroenteritis in children is far less documented in India due to lack of an effective surveillance in place and lack of suitable diagnostics. In view of the importance of NTS in childhood diarrhea, this study was undertaken to determine the isolation rate, predominant serotypes, AMR patterns, plasmid profiles, and molecular subtypes by MLST and PFGE of NTS isolates from hospital-attending children < 5 years of age with acute gastroenteritis in Kolkata, India, during 2000–2016.

5 years of age with acute gastroenteritis in Kolkata, India, during 2000–2016.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Rectal swabs were collected from children < 5 years of age, attending the diarrheal treatment unit (DTU) at the OPD of Dr. B.C Roy Post Graduate Institute of Paediatric Sciences (a government pediatric hospital in West Bengal), Kolkata, India, from January 2000 to December 2016. Patients with acute diarrhea (defined as passage of 3 or more loose or liquid stools per day or more frequently than is normal for the individual as per World Health Organization guidelines) [31], and without prior antibiotic treatment were eligible for inclusion in the study. Samples were collected from every fifth patient from Monday to Friday (except government holidays) between 10.00 am to 1.00 pm. On enrollment, a detailed clinical history regarding the nature, frequency, and duration of diarrhea, frequency of vomiting, abdominal pain, pyrexia, and degree of dehydration were recorded in a standard pro forma. Rectal swabs were collected in Cary Blair’s transport medium and submitted to the Bacteriology division of ICMR-National Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases (NICED) within 2 h of collection for isolation of enteric bacterial pathogens including Salmonella spp.

5 years of age, attending the diarrheal treatment unit (DTU) at the OPD of Dr. B.C Roy Post Graduate Institute of Paediatric Sciences (a government pediatric hospital in West Bengal), Kolkata, India, from January 2000 to December 2016. Patients with acute diarrhea (defined as passage of 3 or more loose or liquid stools per day or more frequently than is normal for the individual as per World Health Organization guidelines) [31], and without prior antibiotic treatment were eligible for inclusion in the study. Samples were collected from every fifth patient from Monday to Friday (except government holidays) between 10.00 am to 1.00 pm. On enrollment, a detailed clinical history regarding the nature, frequency, and duration of diarrhea, frequency of vomiting, abdominal pain, pyrexia, and degree of dehydration were recorded in a standard pro forma. Rectal swabs were collected in Cary Blair’s transport medium and submitted to the Bacteriology division of ICMR-National Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases (NICED) within 2 h of collection for isolation of enteric bacterial pathogens including Salmonella spp.

Sample processing and identification of Salmonella spp.

The isolation and identification of Salmonella spp. was done following standard microbiological methods [32]. Briefly, the rectal swab were inoculated onto two different selective media, namely, MacConkey Agar (MAC) and Hektoen Enteric Agar (HEA) (Difco, MD, USA) both directly as primary culture and following growth in Selenite F enrichment broth (for 12 h at 37 °C). Both primary and secondary culture plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18–24 h.

The presumptive identification of Salmonella spp. was based on colony morphology and standard biochemical tests [33]. Strain identification was confirmed by serotyping using Salmonella poly- and monovalent O and H antisera (Denka Seiken Pvt. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The Salmonella serotype was determined following White-Kauffmann-Le Minor scheme [34]. All Salmonella isolates were preserved at − 80 °C in sterile Trypticase soy broth with 50% glycerol for further studies.

80 °C in sterile Trypticase soy broth with 50% glycerol for further studies.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility test of the studied isolates was done following Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method on Mueller Hinton agar (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) using 17 antibiotic discs (BD BBL™, Maryland, USA): ampicillin (Amp), chloramphenicol (Chl), tetracycline (Tet), co-trimoxazole (Sxt), nalidixic acid (Na), ciprofloxacin (Cip), norfloxacin (Nor), ofloxacin (Ofx), gentamicin (Gm), amikacin (An), streptomycin (Str), cefotaxime (Ctx), ceftazidime (Caz), ceftriaxone (Cro), aztreonam (Atm), azithromycin (Azm), and amoxycillin-clavulanic acid (Amc). Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of the antimicrobials for the resistant isolates were determined by E-test (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden). Results were interpreted following Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (CLSI) [35]. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as control. No Azm MIC breakpoint has been defined for NTS by CLSI. However, researchers have proposed 16 μg/ml as “epidemiological cutoff” value for wild type Salmonella spp. [22, 36]. Phenotypic detection of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) was done by cephalosporin/clavulanate combination disc test [37].

Determination of AMR genes, integrons, and their transferability

The studied isolates were screened by PCR for presence of AMR genes like catA and cmlA (chloramphenicol resistance); tetA and tetB (tetracycline resistance); dfrIa, dfrVII, dfrXII, sul1, sul2, and sul3 (co-trimoxazole resistance); strA, strB, and aadA (streptomycin resistance); aac(6′)-Ib, aadB, and grm for other aminoglycosides like amikacin and gentamicin; blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, and blaOXA (for ESBLs); and mphA and mphB (azithromycin resistance). Quinolone-resistant isolates were tested for any chromosomal mutations in the gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes of quinolone-resistance-determining regions (QRDRs) and for presence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR) genes qnrA, qnrB, qnrS, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and qepA. Presence of class 1 integron (int1) along with gene cassettes was also determined using published primer sequences and PCR conditions [37–41]. Each PCR was followed by direct sequencing of the PCR product using 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Sequences obtained were analyzed by comparison with the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database sequences using BLAST program.

Conjugation experiment was attempted by broth mating procedure in Tryptic soy broth (Difco), using sodium azide–resistant E. coli J53 as the recipient strain and resistant Salmonella strains as donors [42]. Transconjugants were selected as lactose-fermenting colonies of E. coli on MacConkey agar supplemented with sodium azide (100 μg/ml) and one of the following antibiotics: chloramphenicol (16 μg/ml) or cefotaxime (4 μg/ml). The transfer of AMR in transconjugants was checked by disc diffusion, MIC by E-test, and presence of respective resistance genes by PCR.

Plasmid isolation and incompatibility typing

Plasmid DNA was isolated from the studied isolates and transconjugants following Kado and Liu method [43]. Plasmids were electrophoretically separated on 0.8% agarose gel at 70 V for 3 h in Tris-acetic acid-EDTA buffer and visualized after staining with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) solution. The plasmid size was determined by Quantity One software version 4.5 (Bio-Rad) using E. coli V517 and/or Shigella flexneri YSH6000 strains as molecular weight markers. The incompatibility types of the plasmids were determined by PCR using published suitable primers [44].

MLST

MLST was performed by PCR amplification followed by sequencing of the seven housekeeping genes: aroC, dnaN, hemD, hisD, purE, sucA, and thrA as described earlier [30]. The sequence type (ST) for each isolate was obtained on the basis of the sequences of the alleles of aforesaid genes (https://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/species/senterica/allele_st_search).

PFGE

PFGE of XbaI-digested genomic DNA of the studied isolates was performed according to the PulseNet standard protocol using CHEF DRIII apparatus (Bio-Rad) [45]. S. Braenderup H9812 was used as reference strain. The PFGE profiles were analyzed using FP Quest™ software version 4.5 (Bio-Rad). Similarity analysis was determined by Dice coefficient and clustering of bands was done by unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA). The isolates with identical PFGE patterns (100% similarity) were described as clonal. Considering that the strains included in this study were sporadic in nature and isolated over a long period of time from 2000 to 2016, the isolates with PFGE patterns differing by three or less bands (≥ 80% similarity) were designated as closely related or probably (possibly) related; isolates differing by four or more bands (<

80% similarity) were designated as closely related or probably (possibly) related; isolates differing by four or more bands (< 80%) in PFGE profiles were considered as unrelated [46].

80%) in PFGE profiles were considered as unrelated [46].

The dendogram obtained in PFGE was further validated statistically by maximum likelihood (ML) algorithm. The PFGE data set of 82 isolates were compiled into character matrix and subjected to ML analysis available in PAUP* (phylogentic analysis using parsimony) version 4.0a166 (http://phylosolutions.com/paup-test). The resulting tree was subjected to 100 bootstrap replicates [47].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were done using Epi Info™ software for Windows (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA). Pearson’s chi-squared test (χ2) was used to evaluate possible correlation between NTS isolation and seasons; NTS isolation and demographic & clinical characteristics of patients; and NTS serotypes and AMR. All statistical tests in this study were two-sided and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Isolation rate and seasonal variation of Salmonella gastroenteritis

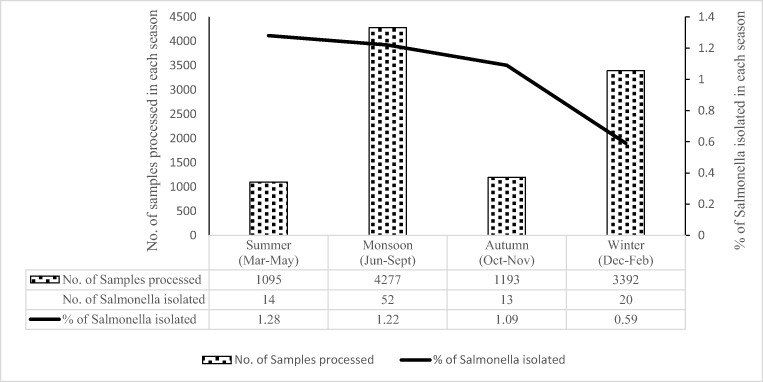

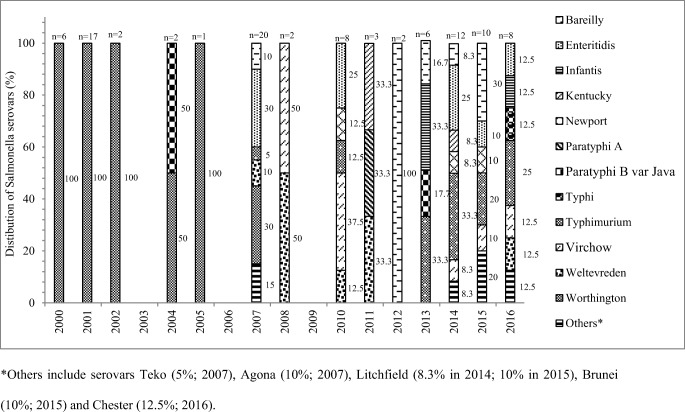

A total of 9957 rectal swabs were collected from children < 5 years of age with acute diarrhea during 17 years period from January 2000 to December 2016 and processed. A total of 99 (0.99%) Salmonella isolates were recovered. These included 97 NTS isolates and one isolate each of S. Typhi and S.Paratyphi A. The isolation rate of Salmonella spp. over the period of 17 years is shown in Fig. 1. Salmonella isolation was significantly (p

5 years of age with acute diarrhea during 17 years period from January 2000 to December 2016 and processed. A total of 99 (0.99%) Salmonella isolates were recovered. These included 97 NTS isolates and one isolate each of S. Typhi and S.Paratyphi A. The isolation rate of Salmonella spp. over the period of 17 years is shown in Fig. 1. Salmonella isolation was significantly (p =

= 0.01) associated with the summer (Mar–May) (n

0.01) associated with the summer (Mar–May) (n =

= 14/1095; 1.28%) and monsoon (June–Sept) (n

14/1095; 1.28%) and monsoon (June–Sept) (n =

= 52/4277; 1.22%) months as compared to autumn (Oct–Nov) (n

52/4277; 1.22%) months as compared to autumn (Oct–Nov) (n =

= 13/1193; 1.09%) and winter (Dec–Feb) (n

13/1193; 1.09%) and winter (Dec–Feb) (n =

= 20/3392; 0.59%) months (Fig. 2).

20/3392; 0.59%) months (Fig. 2).

Year-wise distribution (%) of Salmonella enterica isolated from rectal swabs of children with acute diarrhea in Kolkata, India, from 2000 to 2016

Clinical features of patients with Salmonella gastroenteritis

The demographic and clinical characterization data of patients with acute diarrhea enrolled in this study is shown in Table Table1.1. Children aged 12–23 months (n =

= 30/2210; 1.36%) showed significantly (p

30/2210; 1.36%) showed significantly (p <

< 0.01) higher isolation of Salmonella spp. than children aged 0–11 months (n

0.01) higher isolation of Salmonella spp. than children aged 0–11 months (n =

= 49/4350; 1.13%) and 24–59 months (n

49/4350; 1.13%) and 24–59 months (n =

= 20/3397; 0.59%). Male children (n

20/3397; 0.59%). Male children (n =

= 55/5054; 1.08%) were affected marginally more than the female children (n

55/5054; 1.08%) were affected marginally more than the female children (n =

= 44/4903; 0.89%), (p

44/4903; 0.89%), (p >

> 0.05).The most common type of diarrhea observed in patients with Salmonella infection was watery diarrhea (n

0.05).The most common type of diarrhea observed in patients with Salmonella infection was watery diarrhea (n =

= 54/99, 54.5%) followed by diarrhea containing mucus (24.2%) and diarrhea with blood-mucus (21.2%). The frequency of stool passage on an average was 6 times per day. Majority of the patients had no dehydration (71.7%), abdominal pain (83.8%), fever (62.6%), or vomiting (75.8%).

54/99, 54.5%) followed by diarrhea containing mucus (24.2%) and diarrhea with blood-mucus (21.2%). The frequency of stool passage on an average was 6 times per day. Majority of the patients had no dehydration (71.7%), abdominal pain (83.8%), fever (62.6%), or vomiting (75.8%).

Table 1

Demographic and clinical characterization data of patients (n =

= 9957) with acute diarrhea enrolled in this study

9957) with acute diarrhea enrolled in this study

| Sl. no. | Factors | Total | No. (%) of Salmonella positives | χ2 | p valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. | Demographic characteristics | ||||

| 1. | Age | ||||

| 0–11 months | 4350 | 49 (1.13) | |||

| 12–23 months | 2210 | 30 (1.36) | 9.41 | < 0.01 (S) 0.01 (S) | |

| 24–59 months | 3397 | 20 (0.59) | |||

| 2. | Gender | ||||

| Male | 5054 | 55(1.08) | 0.92 | > 0.05 (NS) 0.05 (NS) | |

| Female | 4903 | 44 (0.89) | |||

| 3. | Family income (Rs) | ||||

< < 3000 3000 | 578 | 10 (1.73) | 4.9 | > 0.05 (NS) 0.05 (NS) | |

| 3001–5000 | 4903 | 51 (1.04) | |||

| 5001–10,000 | 3761 | 34 (0.90) | |||

> > 10,000 10,000 | 715 | 4 (0.56) | |||

| B. | Clinical characteristics | ||||

| 1. | Type of diarrhea | ||||

| Watery diarrhea | 3431 | 54 (1.57) | 17.95 | < 0.001 (S) 0.001 (S) | |

| Diarrhea with mucus | 3310 | 24 (0.73) | |||

| Diarrhea with blood-mucus | 3216 | 21 (0.65) | |||

| 2. | Frequency of stool passage per day | ||||

| 3–4 times | 3297 | 21 (0.64) | |||

| 5–6 times | 4289 | 60 (1.39) | 12.74 | 0.0017 (S) | |

> > 6times 6times | 2371 | 18 (0.76) | |||

| 3. | Degree of dehydration | ||||

| No | 4952 | 71 (1.43) | 26.53 | < 0.0001 (S) 0.0001 (S) | |

| Some | 2796 | 25 (0.89) | |||

| Severe | 2209 | 3 (0.14) | |||

| 4. | Fever | ||||

| Present | 4862 | 37 (0.76) | |||

| Absent | 5095 | 62 (1.22) | 5.25 | 0.021 (S) | |

| 5. | Abdominal pain | ||||

| Present | 5628 | 16 (0.28) | |||

| Absent | 4329 | 83 (1.92) | 66.28 | < 0.0001 (S) 0.0001 (S) | |

| 6. | Vomiting | ||||

| Present | 4225 | 24 (0.56) | |||

| Absent | 5732 | 75 (1.31) | 13.54 | 0.00023 (S) | |

aS significant, NS not significant

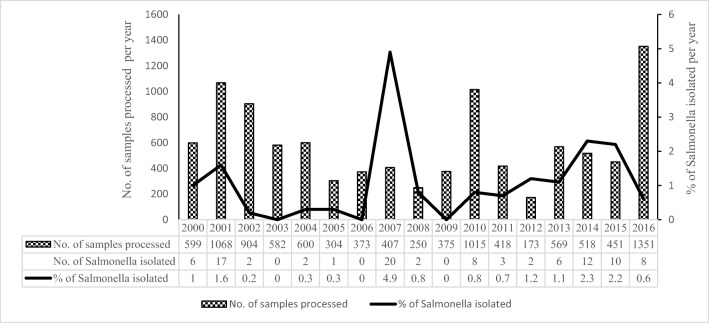

Salmonella serotypes

A total of 17 serovars belonging to eight serogroups were identified among the 99 isolates (Table S1). S. Worthington (n =

= 33; 33%) was the predominant, followed by S. Enteritidis (n

33; 33%) was the predominant, followed by S. Enteritidis (n =

= 13; 13%), S. Typhimurium (n

13; 13%), S. Typhimurium (n =

= 12; 12%), S. Bareilly (n

12; 12%), S. Bareilly (n =

= 9; 9%), S. Virchow (n

9; 9%), S. Virchow (n =

= 7; 7%), S. Weltevreden (n

7; 7%), S. Weltevreden (n =

= 6; 6%), S. Infantis, S. Newport (n

6; 6%), S. Infantis, S. Newport (n =

= 3; 3% each), S. Agona, S. Kentucky, S. Litchfield, S. Paratyphi B var. Java (n

3; 3% each), S. Agona, S. Kentucky, S. Litchfield, S. Paratyphi B var. Java (n =

= 2, 2% each), S. Brunei, S. Chester, S. Paratyphi A, S. Teko, and S. Typhi (n

2, 2% each), S. Brunei, S. Chester, S. Paratyphi A, S. Teko, and S. Typhi (n =

= 1, 1% each). The stack bar diagram shows the percentage distribution of Salmonella enterica serovars in every year (Fig. 3).

1, 1% each). The stack bar diagram shows the percentage distribution of Salmonella enterica serovars in every year (Fig. 3).

Antimicrobial resistance and MIC

The percentage of AMR in Salmonella fecal isolates and MIC towards the antibiotics is given in Table Table2.2. Overall 55.6% of the isolates were pansusceptible (defined as susceptible to all 17 antimicrobials tested in this study), while 44.4% isolates showed resistance to at least one antimicrobial (Table (Table2).2). The common antimicrobial to which most of the isolates of Salmonella spp. showed resistance was Na (43.4%). Resistance to first-line drugs used for treatment of salmonellosis were 34.3%, 7.1%, 6.1%, and 1.0% respectively towards Amp, Sxt, Tet, and Chl. Among the current choice of drugs, high resistance of 32.3% and 25.3% was observed against third-generation cephalosporins (3GCs; Caz, Ctx, and Cro) and Azm respectively, while low resistance of 2% was observed against fluoroquinolones (FQs; Cip, Ofx, and Nor). All (100%) isolates were susceptible to Amc. Multidrug resistance (resistance to ≥ 3 antimicrobial classes) was observed among 37.4% isolates spanning over five serovars S. Worthington (n

3 antimicrobial classes) was observed among 37.4% isolates spanning over five serovars S. Worthington (n =

= 32, 86.5%), S. Kentucky (n

32, 86.5%), S. Kentucky (n =

= 2, 5.4%), S. Typhimurium, S. Infantis, and S. Virchow (n

2, 5.4%), S. Typhimurium, S. Infantis, and S. Virchow (n =

= 1, 2.7% each). Among all serotypes, AMR was significantly associated with S. Worthington (p

1, 2.7% each). Among all serotypes, AMR was significantly associated with S. Worthington (p <

< 0.001) (Table (Table22).

0.001) (Table (Table22).

Table 2

Percentage of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) range of antimicrobials in Salmonella enterica fecal isolates (n =

= 99)* from children in Kolkata (2000–2016)

99)* from children in Kolkata (2000–2016)

| Antimicrobials (disc potency in μg)a | MIC (μg/ml) | Total no. (%) of AMR | Distribution of AMR in Salmonella enterica serovars |

|---|---|---|---|

| Na (30) | > 256 256 | 43 (43.4) | Worthington (n = = 33); Infantis (n 33); Infantis (n = = 3); Kentucky (n 3); Kentucky (n = = 2); Typhimurium (n 2); Typhimurium (n = = 2); Paratyphi A (n 2); Paratyphi A (n = = 1); Typhi (n 1); Typhi (n = = 1); Virchow (n 1); Virchow (n = = 1) 1) |

| Amp (10) | > 256 256 | 34 (34.3) | Worthington (n = = 32); Kentucky (n 32); Kentucky (n = = 2) 2) |

| Caz (30) | 16–256 | 32 (32.3) | Worthington (n = = 32) 32) |

| Ctx (30) | > 32 32 | 32 (32.3) | Worthington (n = = 32) 32) |

| Cro (30) | > 256 256 | 32 (32.3) | Worthington (n = = 32) 32) |

| Atm (30) | > 256 256 | 32 (32.3) | Worthington (n = = 32) 32) |

| Str (10) | 64–128 | 30 (30.3) | Worthington (n = = 26); S. Kentucky (n 26); S. Kentucky (n = = 2); S. Infantis (n 2); S. Infantis (n = = 1); S. Typhimurium (n 1); S. Typhimurium (n = = 1) 1) |

| An (30) | 64–128 | 27 (27.3) | Worthington (n = = 27) 27) |

| Azm (15) | 32–128 | 25 (25.3) | Worthington (n = = 24); Paratyphi A (n 24); Paratyphi A (n = = 1) 1) |

| Sxt (25) | > 32 32 | 7 (7.1) | Infantis (n = = 2); Kentucky (n 2); Kentucky (n = = 2); Virchow (n 2); Virchow (n = = 2); Typhimurium (n 2); Typhimurium (n = = 1) 1) |

| Tet (30) | 48–> 256 256 | 6 (6.1) | Kentucky (n = 2); Virchow (n 2); Virchow (n = = 2); Infantis (n 2); Infantis (n = = 1); Typhimurium (n 1); Typhimurium (n = = 1) 1) |

| Cip (5) | 8 | 2 (2.0) | Kentucky (n = = 2) 2) |

| Nor (10) | 16 | 2 (2.0) | Kentucky (n = = 2) 2) |

| Ofx (5) | 32 | 2 (2.0) | Kentucky (n = = 2) 2) |

| Gm (10) | 16 | 2 (2.0) | Kentucky (n = = 2) 2) |

| Chl (30) | > 256 256 | 1 (1.0) | Typhimurium (n = = 1) 1) |

| Resistance to 0 antimicrobial (pansusceptible) | 55 (55.6) | Enteritidis (n = = 13); Typhimurium (n 13); Typhimurium (n = = 10); Bareilly (n 10); Bareilly (n = = 9); Weltevreden (n 9); Weltevreden (n = = 6); Virchow (n 6); Virchow (n = = 5); Newport (n 5); Newport (n = = 3); Agona (n 3); Agona (n = = 2), Litchfield (n 2), Litchfield (n = = 2); Paratyphi B var. Java (n 2); Paratyphi B var. Java (n = = 2); Brunei (n 2); Brunei (n = = 1); Chester (n 1); Chester (n = = 1); Teko (n 1); Teko (n = = 1) 1) | |

| Resistance to 1 antimicrobial | – | 4 (4.0) | Infantis (n = = 1); Typhimurium (n 1); Typhimurium (n = = 1); Virchow (n 1); Virchow (n = = 1); Worthington (n 1); Worthington (n = = 1) 1) |

| Resistance to 2 antimicrobials | – | 3 (3.0) | Infantis (n = = 1); Paratyphi A (n 1); Paratyphi A (n = = 1); Virchow (n 1); Virchow (n = = 1) 1) |

Resistance to ≥ 3 antimicrobials 3 antimicrobials | – | 37 (37.4) | Worthington (n = = 32); Kentucky (n 32); Kentucky (n = = 2); Infantis (n = 2); Infantis (n = 1); Virchow (n 1); Virchow (n = = 1); Typhimurium (n 1); Typhimurium (n = = 1) 1) |

*Fifty-five (55.6%) isolates were pansusceptible (susceptible to all 17 antimicrobials tested in the study) while 44 (44.4%) isolates showed resistance to one or more above tested antimicrobials

aAmp ampicillin, An amikacin, Atm aztreonam, Azm azithromycin, Caz ceftazidime, Chl chloramphenicol, Cip ciprofloxacin, Cro ceftriaxone, Ctx cefotaxime, Gm gentamicin, Na nalidixic acid, Nor norfloxacin, Ofx ofloxacin, Str streptomycin, Sxt co-trimoxazole, Tet tetracycline

Antimicrobial resistance profiles and genes mediating antimicrobial resistance

Twelve AMR-profiles (I-XII) were observed among resistant Salmonella studied isolates (Table (Table3).3). The profile V (NaR) was common among S. Worthington, S. Typhimurium, S. Infantis, and S. Typhi (n =

= 1 each). Presence of AMR genes, chromosomal mutations associated with Na resistance, and class 1 integron found among the studied isolates is shown in Table Table33.

1 each). Presence of AMR genes, chromosomal mutations associated with Na resistance, and class 1 integron found among the studied isolates is shown in Table Table33.

Table 3

Phenotypic and genetic profiles of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) of Salmonella enterica fecal isolates (n =

= 44)* from Kolkata during 2000–2016

44)* from Kolkata during 2000–2016

| Serotype | AMR profile (n)a | Detection of AMR genes | Mutations in QRDRb | Class 1 integron | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amp | Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm | Azm | Str | An | Gm | Chl | Tet | Sxt | gyrA | parC | Approximate size of gene cassette | Gene cassette array | |||

| S. Worthington | I | Na, Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm, An, Str, Azm (24) | blaTEM-1 | blaCTX-M-15,blaSHV-12 | mphA | aadA1 | aac(6′)-Ib | – | – | – | – | S83Y [TCC | – | – | – |

| II | Na, Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm, An, Str (2) | blaTEM-1 | blaCTX-M-15 | – | aadA1 | aac(6′)-Ib | – | – | – | – | S83Y [TCC | – | – | – | |

| III | Na, Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm, An (1) | blaTEM-1 | blaCTX-M-15,blaSHV-12 | – | – | aac(6′)-Ib | – | – | – | – | S83Y [TCC | – | – | – | |

| IV | Na, Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm (5) | blaTEM-1 | blaCTX-M-15, blaSHV-12 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | S83Y [TCC | – | – | – | |

| V | Na (1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | S83Y [TCC | – | – | – | |

| S. Infantis | VI | Tet, Sxt, Str, Na (1) | – | – | – | aadA1 | – | – | – | tetA | sul1 | D87Y [GAC | – | 1.0 kb | aadA1 |

| VII | Sxt, Na (1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | dfrA1, sul1 | D87Y [GAC | – | 1.2 kb | dfrA1-orfC | |

| V | Na (1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | D87Y [GAC → → TAC] TAC] | – | – | – | |

| S. Kentucky | VIII | Amp, Tet, Sxt, Str, Gm, Na, Cip, Nor, Ofx (2) | blaTEM-1 | – | – | aadA7 | – | aac(3′)-Id | tetA | sul1 | S83F [TCC D87Y [GAC | S80I [AGC | 1.5 kb | aac(3′)-Id - aadA7 | |

| S. Typhimurium | IX | Chl, Tet, Sxt, Str, Na (1) | – | – | – | aadA1, aadA2 | – | – | cmlA1 | tetA | dfrA12, sul3 | D87Y [GAC | – | 7 kb | dfrA12-orfF-aadA2-cmlA1-aadA1 |

| V | Na (1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | D87Y [GAC | – | – | – | |

| S. Virchow | X | Tet, Sxt, Na (1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | tetA | sul1, dfrA5 | S83Y [TCC | – | 0.7 kb | dfrA5 |

| XI | Tet, Sxt (1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | tetA | sul1, dfrA5 | – | – | 0.7 kb | dfrA5 | |

| S. Paratyphi A | XII | Azm, Na (1) | – | – | mphA | – | – | – | – | – | – | S83 L [TCC | – | – | – |

| S. Typhi | V | Na (1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | D87N [GAC | – | – | – |

*Remaining Salmonella enterica isolates (n =

= 55) were pansusceptible

55) were pansusceptible

aAmp ampicillin, An amikacin, Atm aztreonam, Azm azithromycin, Caz ceftazidime, Chl chloramphenicol, Cip ciprofloxacin, Cro ceftriaxone, Ctx cefotaxime, Gm gentamicin, Na nalidixic acid, Nor norfloxacin, Ofx ofloxacin, Str streptomycin, Sxt co-trimoxazole, Tet tetracycline

bQRDR quinolone-resistance-determining region, S serine, Y tyrosine, F phenylalanine, D aspartate, L leucine, N asparagine

Plasmid characterization

One or more plasmids of molecular size ranging from 4 to 254 kb were found in 65 (65.7%) studied isolates (Table (Table4).4). Diversity in plasmid profiles was found both across the serovars and within each serovar, with a total of 31 plasmid profiles (P1–P31). No correlation between plasmid profiles and AMR profiles was observed. Plasmids were present in both resistant (n =

= 36/65, 55.4%) and pansusceptible (n

36/65, 55.4%) and pansusceptible (n =

= 29/65; 44.6%) isolates. Among plasmid-less isolates (n

29/65; 44.6%) isolates. Among plasmid-less isolates (n =

= 34), 26 were pansusceptible and eight [S. Infantis (n

34), 26 were pansusceptible and eight [S. Infantis (n =

= 3), S. Kentucky (n

3), S. Kentucky (n =

= 2), S. Virchow (n

2), S. Virchow (n =

= 2), and S. Typhi (n

2), and S. Typhi (n =

= 1)] were resistant.

1)] were resistant.

Table 4

Attributes of plasmids in non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica fecal isolates (n =

= 65) from children in Kolkata (2000–2016)

65) from children in Kolkata (2000–2016)

| Serotype | Plasmid profiles (kb) | Plasmid type | No. of isolates | AMR-profilea | Transconjugant | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid profile | Plasmid type | AMR-profile | AMR genes | ||||||

| S. Worthington | P1 | 79.4, 68.2, 50.8, 4.9 | FIA, FIB, I1 | 1 | III | 79.4, 68.2 | I1 | Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm | blaTEM-1,blaCTX-M-15 |

| P2 | 76.4, 68.2, 50.8, 4.9 | FIA, FIB, I1 | 2 | IV | 76.4, 68.2 | I1 | Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm | blaTEM-1,blaCTX-M-15 | |

| 8 | I | ||||||||

| P3 | 76.4, 68.2, 50.8 | FIA, FIB, I1 | 1 | I | 76.4, 68.2 | I1 | Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm | blaTEM-1,blaCTX-M-15 | |

| P4 | 76.4, 68.2, 4.9 | FIA, FIB, I1 | 1 | I | 76.4, 68.2 | I1 | Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm | blaTEM-1,blaCTX-M-15 | |

| P5 | 76.4, 50.8, 4.9 | FIA, FIB, I1 | 1 | II | 76.4 | I1 | Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm | blaTEM-1,blaCTX-M-15 | |

| P6 | 70.8, 68.2, 50.8, 4.9 | FIA, FIB, I1 | 3 | I | 70.8, 68.2 | I1 | Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm | blaTEM-1,blaCTX-M-15 | |

| P7 | 68.2, 62.5, 50.8, 4.9 | FIA, FIB, I1 | 1 | IV | 68.2 | I1 | Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm | blaTEM-1,blaCTX-M-15 | |

| P8 | 68.2, 50.8, 4.9 | FIA, FIB, I1 | 1 | IV | 68.2 | I1 | Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm | blaTEM-1,blaCTX-M-15 | |

| 1 | II | ||||||||

| 10 | I | ||||||||

| P9 | 68.2, 4.9 | I1 | 1 | I | 68.2 | I1 | Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm | blaTEM-1,blaCTX-M-15 | |

| P10 | 68.2 | I1 | 1 | IV | 68.2 | I1 | Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm | blaTEM-1,blaCTX-M-15 | |

| P11 | 50.8 | FIA,FIB | 1 | V | – | – | – | – | |

| S. Typhimurium | P12 | 254, 130 | FIIS, FIB | 1 | IX | 254 | FIIS, FIB | Chl, Tet, Sxt, Str | cmlA1, tetA, dfrA12, sul3, aadA1, aadA2, int1 |

| P13 | 180, 98.5 | FIIS | 2 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – | |

| P14 | 130 | FIIS, FIB | 1 | V | – | – | – | – | |

| P15 | 108.4 | FIIS, FIB | 2 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – | |

| P16 | 98.5 | FIIS | 2 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – | |

| S. Enteritidis | P17 | 98.8 | FIIS, FIB | 4 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – |

| P18 | 60.4, 52.4, 22.1 | FIIS, FIB | 1 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – | |

| P19 | 60.4, 45.4 | FIIS, FIB | 1 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – | |

| P20 | 60.4, 2.6 | FIIS, FIB | 1 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – | |

| P21 | 60.4 | FIIS, FIB | 6 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – | |

| S. Weltevreden | P22 | 121.4 | FIIS | 2 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – |

| P23 | 97.4, 47.5 | FIIS | 1 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – | |

| P24 | 97.4 | FIIS | 1 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – | |

| P25 | 83.6, 2.8 | FIIS | 1 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – | |

| P26 | 83.6 | FIIS | 1 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – | |

| S. Agona | P27 | 5.6 | Untypable | 1 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – |

| S. Paratyphi A | P28 | 96.2, 4.9 | FIIA, FIIS, FIB | 1 | XII | – | – | – | – |

| S. Brunei | P29 | 54.8 | FIIS | 1 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – |

| S. Litchfield | P30 | 4.0 | Untypable | 1 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – |

| S. Teko | P31 | 197.8, 97.5 | FIIS | 1 | Pansusceptible | – | – | – | – |

aI, resistant to Na, Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm, An, Str, Azm; II, resistant to Na, Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm, An, Str; III, resistant to Na, Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm, An; IV, resistant to Na, Amp, Caz, Ctx, Cro, Atm; V, resistant to Na; IX, resistant to Chl, Tet, Sxt, Str, Na

Amp ampicillin, An amikacin, Atm aztreonam, Azm azithromycin, Caz ceftazidime, Chl chloramphenicol, Cip ciprofloxacin, Cro ceftriaxone, Ctx cefotaxime, Na nalidixic acid, Str streptomycin, Sxt co-trimoxazole, Tet tetracycline

The plasmid incompatibility typing revealed presence of IncFIB (n =

= 49, 75.4%), IncI1 (n

49, 75.4%), IncI1 (n =

= 32, 49.2%), IncFIA (n

32, 49.2%), IncFIA (n =

= 31, 47.7%), IncFIIS (n

31, 47.7%), IncFIIS (n =

= 30, 46.2%), and IncFIIA (n

30, 46.2%), and IncFIIA (n =

= 1, 1.5%) types among 65 studied isolates (Table (Table4).4). In two isolates, plasmids were untypable. IncFIA and IncI1 type plasmids were found only in S. Worthington isolates, whereas IncFIIS type plasmid was found in all serovars except S. Worthington.

1, 1.5%) types among 65 studied isolates (Table (Table4).4). In two isolates, plasmids were untypable. IncFIA and IncI1 type plasmids were found only in S. Worthington isolates, whereas IncFIIS type plasmid was found in all serovars except S. Worthington.

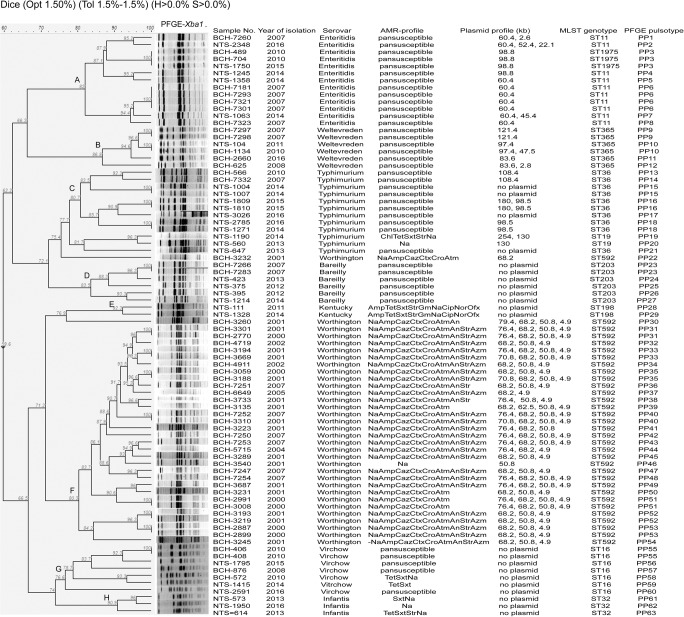

MLST and PFGE analysis

MLST and PFGE were performed for 85 isolates comprising eight important serovars. The S. Worthington, S. Bareilly, S. Virchow, S. Weltevreden, S. Infantis, and S. Kentucky isolates were assigned to sequence types ST592, ST203, ST16, ST365, ST32, and ST198 respectively. ST36 and ST19 were found in S. Typhimurium and ST11 and ST1975 types were common in S. Enteritidis isolates (Fig. 4). Sequence type (ST592) of S. Worthington was not reported earlier from India.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) profiles of XbaI-digested DNA of non-typhoidal Salmonella isolates (n =

= 82) from children with acute gastroenteritis, India, 2000–2016. Band comparison was performed using Dice coefficient with 1.50% optimization (Opt) and 1.5% position tolerance (Tol). H minimum height, S minimum surface, Amp ampicillin, An amikacin, Atm aztreonam, Azm azithromycin, Caz ceftazidime, Chl chloramphenicol, Cip ciprofloxacin, Cro ceftriaxone, Ctx cefotaxime, Gm gentamicin, Na nalidixic acid, Nor norfloxacin, Ofx ofloxacin, Str streptomycin, Sxt co-trimoxazole, Tet tetracycline

82) from children with acute gastroenteritis, India, 2000–2016. Band comparison was performed using Dice coefficient with 1.50% optimization (Opt) and 1.5% position tolerance (Tol). H minimum height, S minimum surface, Amp ampicillin, An amikacin, Atm aztreonam, Azm azithromycin, Caz ceftazidime, Chl chloramphenicol, Cip ciprofloxacin, Cro ceftriaxone, Ctx cefotaxime, Gm gentamicin, Na nalidixic acid, Nor norfloxacin, Ofx ofloxacin, Str streptomycin, Sxt co-trimoxazole, Tet tetracycline

PFGE generated 63 pulsotypes (PP) and grouped Salmonella isolates into eight distinct clusters A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H which were serovar-specific and represented Enteritidis (n =

= 13), Weltevreden (n

13), Weltevreden (n =

= 6), Typhimurium (n

6), Typhimurium (n =

= 12), Bareilly (n

12), Bareilly (n =

= 6), Kentucky (n

6), Kentucky (n =

= 2), Worthington (n

2), Worthington (n =

= 31), Virchow (n

31), Virchow (n =

= 7), and Infantis (n

7), and Infantis (n =

= 3) respectively. However, two S. Worthington isolates (pulsotypes PP22 and PP30) did not belong to cluster F. Three S. Bareilly isolates remained untypable by XbaI enzyme. With the exception of S. Virchow, strains belonging to seovars Enteritidis, Weltevreden, Typhimurium, Bareilly, Kentucky, Worthington, and Infantis were found to be closely related or probably related (>

3) respectively. However, two S. Worthington isolates (pulsotypes PP22 and PP30) did not belong to cluster F. Three S. Bareilly isolates remained untypable by XbaI enzyme. With the exception of S. Virchow, strains belonging to seovars Enteritidis, Weltevreden, Typhimurium, Bareilly, Kentucky, Worthington, and Infantis were found to be closely related or probably related (> 80% similarity coefficient). Some of the strains within each cluster were found to be clonal in nature (100% similarity coefficient) indicating origin from same source. The S. Virchow strains although found to be genetically unrelated (76.6% similarity coefficient), yet few clonal or closely related strains (PP55, PP56, PP58, PP59) were also found within the cluster G (Fig. (Fig.4).4). The different PFGE clusters specific for different serovars suggested the presence of diverse reservoirs of NTS infection in Kolkata. However, the circulation of closely related or probably related strains of each serotype within each cluster speculated towards diversification of serotype-specific strains from a common reservoir of infection over a long period of time.

80% similarity coefficient). Some of the strains within each cluster were found to be clonal in nature (100% similarity coefficient) indicating origin from same source. The S. Virchow strains although found to be genetically unrelated (76.6% similarity coefficient), yet few clonal or closely related strains (PP55, PP56, PP58, PP59) were also found within the cluster G (Fig. (Fig.4).4). The different PFGE clusters specific for different serovars suggested the presence of diverse reservoirs of NTS infection in Kolkata. However, the circulation of closely related or probably related strains of each serotype within each cluster speculated towards diversification of serotype-specific strains from a common reservoir of infection over a long period of time.

Maximum likelihood analysis of the PFGE profiles of NTS isolates also showed serovar-specific clustering (Fig. S1). The designation of the clusters (A–H) representing serovars Enteritidis, Weltevreden, Typhimurium, Bareilly, Kentucky, Worthington, Virchow, and Infantis respectively has been retained as in Fig. Fig.44 for easy understanding. Except for the subtle positional change in clustering of C (S. Typhimurium) and D (S. Bareilly) & G (S. Virchow) and H (S. Infantis), the overall clustering of strains by ML method did not change. Thus, phylogenetic analysis by PFGE showed genetically related strains in circulation among children in Kolkata, India.

The characteristics of S. Typhimurium fecal isolates described in this study were partially published in our earlier study [42].

Discussion

In the present study, the rate of isolation of Salmonella in children < 5 years of age with acute diarrhea in and around Kolkata over 17 years (2000–2016) was found to be 1%, which was considerably less compared to an earlier study (15.3%) from Kolkata (1993–1996) in children ≤

5 years of age with acute diarrhea in and around Kolkata over 17 years (2000–2016) was found to be 1%, which was considerably less compared to an earlier study (15.3%) from Kolkata (1993–1996) in children ≤ 2 years of age [6]. During the studied period, the isolation rate of Salmonella in the year 2007 was found to be unusually high (4.9%) in comparison with other years (Fig. (Fig.1).1). This could be due to the disastrous rainfall and flood that severely affected areas in and around Kolkata during 2007 [48]. A decrease in isolation of Salmonella spp. from 3.9% (1994–1998) to 1% (2002–2010) was also noted and reported among gastroenteritis patients of all age group from North India [49]. The reason behind the decline in isolation rate of NTS in recent years was not obvious, but could be due to the awareness development campaign by the Government of India for access to safe and clean potable water, for improved sanitation, and hygiene practice. The prevalence rate of Salmonella in stool samples of under 5 years children as reported from different countries was 1.9% (Nepal), 4.3–17.2% (China), 5.4% (Vietnam), 10.3% (Iraq), and 2.5–25.5% (African countries) [4, 10–14, 50–54]. The wide variation in isolation rate of enteric Salmonella strains may be attributable to difference in local geography, socioeconomic conditions, season, and duration of sampling as well as access to medical facility and laboratory testing.

2 years of age [6]. During the studied period, the isolation rate of Salmonella in the year 2007 was found to be unusually high (4.9%) in comparison with other years (Fig. (Fig.1).1). This could be due to the disastrous rainfall and flood that severely affected areas in and around Kolkata during 2007 [48]. A decrease in isolation of Salmonella spp. from 3.9% (1994–1998) to 1% (2002–2010) was also noted and reported among gastroenteritis patients of all age group from North India [49]. The reason behind the decline in isolation rate of NTS in recent years was not obvious, but could be due to the awareness development campaign by the Government of India for access to safe and clean potable water, for improved sanitation, and hygiene practice. The prevalence rate of Salmonella in stool samples of under 5 years children as reported from different countries was 1.9% (Nepal), 4.3–17.2% (China), 5.4% (Vietnam), 10.3% (Iraq), and 2.5–25.5% (African countries) [4, 10–14, 50–54]. The wide variation in isolation rate of enteric Salmonella strains may be attributable to difference in local geography, socioeconomic conditions, season, and duration of sampling as well as access to medical facility and laboratory testing.

In this study, cases of Salmonella gastroenteritis peaked in the summer and monsoon months (Mar–Sept) (p =

= 0.01) (Fig. (Fig.2),2), which was consistent with earlier studies from China, India, Iraq, and Vietnam [4, 6, 13, 14]. Hot and humid conditions facilitate microbial replication leading to food contamination and transmission of pathogens causing foodborne diseases.

0.01) (Fig. (Fig.2),2), which was consistent with earlier studies from China, India, Iraq, and Vietnam [4, 6, 13, 14]. Hot and humid conditions facilitate microbial replication leading to food contamination and transmission of pathogens causing foodborne diseases.

Children aged 12–23 months (p <

< 0.01) were found to be significantly more susceptible to Salmonella gastrointestinal (GI) infection. Similar results were reported from China, Iraq, and Zambia [4, 13, 54]. This age group is more vulnerable to GI infection due to reduced protective immunity caused by switch from breast to bottle feeding, habits of crawling, and tendency to put fingers or fomites inside the mouth. Regarding clinical manifestation, half of the studied children (54.5%) presented with watery diarrhea which was consistent with reports from Iraq (75.8%) and Vietnam (54%) [13, 14]. Unlike other studies [13, 14], abdominal pain and fever were not reported to be the cardinal features of Salmonella gastroenteritis in the current study.

0.01) were found to be significantly more susceptible to Salmonella gastrointestinal (GI) infection. Similar results were reported from China, Iraq, and Zambia [4, 13, 54]. This age group is more vulnerable to GI infection due to reduced protective immunity caused by switch from breast to bottle feeding, habits of crawling, and tendency to put fingers or fomites inside the mouth. Regarding clinical manifestation, half of the studied children (54.5%) presented with watery diarrhea which was consistent with reports from Iraq (75.8%) and Vietnam (54%) [13, 14]. Unlike other studies [13, 14], abdominal pain and fever were not reported to be the cardinal features of Salmonella gastroenteritis in the current study.

In this study, S. Worthington, S. Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium, S. Bareilly, S. Virchow, and S. Weltevreden were the frequently isolated serovars. The WHO Global Foodborne Infections Network’s report on NTS surveillance from both developed and developing countries showed S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium to be the predominant serovars isolated from humans [55]. S. Virchow was ranked among the top 15 serovars in Asia and Europe. Serovars like S. Worthington, S. Weltevreden, and S. Bareilly were commonly reported from South Asian countries including India [55, 56]. Presence of a local animal reservoir or food greatly contributed towards dominance of certain serotypes in particular regions [55]. Interestingly, Salmonella serotype distribution at one place may vary over a course of time. In this study, S. Worthington dominated during 2000–2005 and was then gradually replaced by other serovars since 2007 and S. Typhimurium emerged as the most prevalent serovar during 2013–2016 (Fig. (Fig.3).3). The serovar shift from S. Typhimurium (1994–1998) to S. Senftenberg (2002–2010) was reported in North India [49]. Bassal et al. reported predominance of S. Infantis over S. Enteritidis (1999–2008) in Israel post 2008 [57]. The shift from S. Enteritidis (2010) to S. Typhimurium (2011–2015) as the predominant serovar among humans was also reported from southern Brazil [58]. Changes in meteorology, human food habits, international travel, and trade have been associated with the temporal dominance of certain serotypes followed by a decline and replacement with another [52, 57].

Antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella is a growing public health problem. Resistance to first-line drugs (Amp, Chl, Tet, and Sxt) was found to be considerably lower (1–34%) (Table (Table2)2) in comparison with those reported by Saha et al. (71–99%) in the past (1993–1996) [6]. A decline in resistance to these drugs suggested that these still might be useful choice for empiric treatment. Unlike this study, high resistance rates towards first-line drugs were reported in NTS from countries like China (16–67%), Iraq (50–70%), Nepal (10–70%), Africa (17–100%), and Brazil (15–44%) during the same period [4, 8, 10–13, 50–54, 58, 59]. Among the current choice of drugs, resistance to 3GCs was found in 32% studied isolates, which was not very encouraging as 3GCs are the current drugs of choice for treatment of salmonellosis in children. Although FQ resistance was observed in only 2% of studied isolates, intermediate susceptibility to Cip (MIC 0.125–0.5 μg/ml) and Ofx (MIC 0.25–0.75 μg/ml) were found in 41% studied isolates, which was alarming as it has been associated with increased treatment failures with ciprofloxacin in invasive salmonellosis. The rate of resistance to 3GCs (28–42%) and FQs (14–58%) was found to be higher in enteric NTS isolates from children in Asian countries [4, 11–13, 50], than those isolated from children in African countries (0–13% for 3GCs and 0–11% for FQs) [8, 10, 49–52]. Resistance to Azm was found to be 25% in the studied isolates. Although it was lower than those reported from China (44%) and Iraq (67%) [12, 13], judicial use of this drug antimicrobial is recommended as it is reserved as an alternative antimicrobial for treatment of enteric fever and invasive NTS infections.

With respect to AMR in different serovars, 71.4% S. Virchow, 83.3% S. Typhimurium, and 100% S. Enteritidis studied isolates were pansusceptible, which was in sharp contrast to multiple resistances reported in these serovars worldwide [4, 7–9, 11, 13, 21, 52, 57–59]. All studied isolates of S. Worthington, S. Infantis and S. Kentucky showed resistance to one or more antimicrobial tested (Table (Table2).2). High drug resistance was common in these serovars and reported from various countries in the past [10, 23, 49, 52, 60, 61]. ESBL production and FQ resistance were exclusively observed in S. Worthington and S. Kentucky MDR studied isolates respectively (Table (Table33).

A single-point mutation (Ser83-Tyr/Leu or Asp87-Tyr/Asn) in gyrA gene was found in all Na-resistant isolates of this study. The CipRS. Kentucky isolates (n =

= 2) possessed double gyrA (Ser83-Phe, Asp87Tyr) and a single parC (Ser80-Ile) mutation. Similar mutations were reported in various Salmonella serovars in the past [23, 27, 38]. The amino acids substitutions at codon 83 or 87 of gyrA varied with the serovar (Table (Table3),3), which corroborated with the earlier findings of Eaves et al. [38]. ESBL production in S. Worthington isolates was mediated by blaCTX-M-15 (n

2) possessed double gyrA (Ser83-Phe, Asp87Tyr) and a single parC (Ser80-Ile) mutation. Similar mutations were reported in various Salmonella serovars in the past [23, 27, 38]. The amino acids substitutions at codon 83 or 87 of gyrA varied with the serovar (Table (Table3),3), which corroborated with the earlier findings of Eaves et al. [38]. ESBL production in S. Worthington isolates was mediated by blaCTX-M-15 (n =

= 32/32; 100%) and blaSHV-12 (n

32/32; 100%) and blaSHV-12 (n =

= 18/32; 56.3%) genes leading to resistance against 3GCs and Atm. Earlier studies from India have documented the presence of blaCTX-M-15, blaSHV-12, and blaSHV-5 ESBL genes in NTS [27, 49]. The blaTEM ESBL genes were not identified in this study, although it was reported from other countries [20]. High-level resistance to Azm in S. Worthington (MIC 32-64 μg/ml) and S. Paratyphi A (MIC 128 μg/ml) in this study was attributed to the presence of mphA gene, which was not reported earlier very frequently. In 2016, Nair et al. from UK showed that mphA gene was associated with Azm resistance (MIC

18/32; 56.3%) genes leading to resistance against 3GCs and Atm. Earlier studies from India have documented the presence of blaCTX-M-15, blaSHV-12, and blaSHV-5 ESBL genes in NTS [27, 49]. The blaTEM ESBL genes were not identified in this study, although it was reported from other countries [20]. High-level resistance to Azm in S. Worthington (MIC 32-64 μg/ml) and S. Paratyphi A (MIC 128 μg/ml) in this study was attributed to the presence of mphA gene, which was not reported earlier very frequently. In 2016, Nair et al. from UK showed that mphA gene was associated with Azm resistance (MIC ≥

≥ 16 μg/ml) in NTS serovars [22]. Class 1 integron was found in seven (7.1%) isolates (Table (Table3),3), of which five were MDR further aggravating the possibility of dissemination of multiple AMR. The gene cassette, found in this study, was widely reported in Salmonella serovars from different countries [24–27].

16 μg/ml) in NTS serovars [22]. Class 1 integron was found in seven (7.1%) isolates (Table (Table3),3), of which five were MDR further aggravating the possibility of dissemination of multiple AMR. The gene cassette, found in this study, was widely reported in Salmonella serovars from different countries [24–27].

Plasmid analysis was useful in studying the diversity of plasmid profiles within serovars and also to determine the role of plasmid in transmission of AMR to other pathogens. Ten plasmid profiles (P1–P10) were observed in MDR S. Worthington, of which P8 and P2 were most common (> 60%) (Table (Table4).4). Plasmid of IncI1 type (79.4, 76.4, 70.8, and 68.2 kb size) was transferable to E.coli J53 by conjugation, which carried blaTEM-1 and blaCTX-M-15 genes. Plasmids of incompatibility type I1, FIA, FIB, B/O, FIIS, and FIIA harboring blaCTX-M-15 gene have been reported in many Salmonella serovars [27, 62, 63]. Genes like blaSHV-12 and mphA found in S. Worthington–studied isolates were not transferable, suggesting co-localization of the genes on chromosome or on non-conjugative plasmid. The role of plasmids in pansusceptible isolates needs further exploration.

60%) (Table (Table4).4). Plasmid of IncI1 type (79.4, 76.4, 70.8, and 68.2 kb size) was transferable to E.coli J53 by conjugation, which carried blaTEM-1 and blaCTX-M-15 genes. Plasmids of incompatibility type I1, FIA, FIB, B/O, FIIS, and FIIA harboring blaCTX-M-15 gene have been reported in many Salmonella serovars [27, 62, 63]. Genes like blaSHV-12 and mphA found in S. Worthington–studied isolates were not transferable, suggesting co-localization of the genes on chromosome or on non-conjugative plasmid. The role of plasmids in pansusceptible isolates needs further exploration.

MLST of the studied isolates revealed only one ST for serovars like S. Worthington (ST592), S. Bareilly (ST203), S. Virchow (ST16), S. Weltevreden (ST365), S. Infantis (ST32), and S. Kentucky (ST198), and two STs for serovars S. Typhimurium (ST36 and ST19) and S. Enteritidis (ST11 and ST1975). Phylogenetic clonal serovars by MLST as observed in this study was also reported in studies from other countries [29, 30, 61]. All STs reported in this study were the common STs generally found in the specific Salmonella serovars globally as evidenced in the MLST database (enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/species/senterica/search_strains). Isolation of CipRS. Kentucky ST198 MDR strains from children is alarming due to its association with the epidemic clone. The epidemic S. Kentucky ST198 clone, resistant to first-line antimicrobials and ciprofloxacin, originated in Egypt in 2002, and since then has spread rapidly through Africa, Middle-east, Asia, and Europe [23]. MLST showed good correlation between different Salmonella serovars and their STs may be used as an alternative to cumbersome serotyping for determining serovars, as was suggested by earlier researchers [29, 64]. However, MLST was less discriminatory than PFGE for epidemiological Salmonella surveillance. PFGE analysis could identify multiple pulsotypes among isolates having same STs (Fig. (Fig.4).4). No significant correlation among PFGE profiles, sequence types, AMR profiles, and plasmid profiles were found among the studied isolates. Although, genetically related strains (> 80% similarity coefficient) of each serovar were found in circulation, the presence of different serovar-specific PFGE clusters suggested the presence of multiple reservoirs of NTS in the environment and hence multiple sources for infection in children. An integrative study involving NTS isolated from humans, animals, and environmental samples would help to track the source of infection and subsequently prevent its spread among humans.

80% similarity coefficient) of each serovar were found in circulation, the presence of different serovar-specific PFGE clusters suggested the presence of multiple reservoirs of NTS in the environment and hence multiple sources for infection in children. An integrative study involving NTS isolated from humans, animals, and environmental samples would help to track the source of infection and subsequently prevent its spread among humans.

Most cases of NTS diarrhea remain unreported due to their self-limiting nature of infection and therefore this hospital-based surveillance study may not truly reflect the magnitude of Salmonella specific diarrheal disease in the community. However, the high level of resistance to 3GCs, FQs, and Azm observed in some serovars of NTS is a cause of concern and public health threat. Unnecessary antibiotic use for treatment of NTS gut infection should be avoided. The isolation of MDR isolates carrying transferable resistance genes on plasmids and integrons is worrisome and reinforces the importance of surveillance for monitoring Salmonella serovars and their AMR profiles to control the spread of resistant isolates. Prevention of infection in children by disseminating proper hand hygiene practice is also strongly recommended.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor R. Bonnet, CHU Clermont-Ferrand, France, for providing CTX-M control strains. We acknowledge the help of Dr. B. Manna, ex-Scientist F from ICMR-NICED, in statistical calculation. The help of NICED staffs in sample collection and transport is also gratefully acknowledged.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Shanta Dutta. Methodology: Priyanka Jain, Sriparna Samajpati, Arindam Ganai, Surajit Basak. Data curation: Priyanka Jain, Goutam Chowdhury, Surajit Basak, Sandip Samanta. Formal analysis and investigation: Priyanka Jain, Surajit Basak, Asish K. Mukhopadhyay, Keinosuke Okamoto. Resources: Goutam Chowdhury, Sandip Samanta, Asish K. Mukhopadhyay, Keinosuke Okamoto. Supervision: Shanta Duta. Writing-original draft preparation: Priyanka Jain, Shanta Dutta. Writing-review and editing: Goutam Chowdhury, Sriparna Samajpati, Surajit Basak, Arindam Ganai, Sandip Samanta, Keinosuke Okamoto, Asish K. Mukhopadhyay.

Funding information

The study was supported in part by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New-Delhi intramural fund and Japan Initiative for Global Research Network on Infectious Diseases (J-GRID) of the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under grant number JP18fm0108002. ICMR senior research fellowship to P. Jain and S. Samajpati are received.

Compliance with ethical standards

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

The present study was reviewed and approved (no. C-48/2011-T & E) by the Institutional Ethical Committee (IEC) of ICMR-National Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases (NICED), Kolkata.

Informed consents were obtained from the parents or guardians of each patient enrolled in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Articles from Brazilian Journal of Microbiology are provided here courtesy of Brazilian Society of Microbiology

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42770-019-00213-z

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc7203375?pdf=render

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1007/s42770-019-00213-z

Article citations

Characterization of Virulence Genotypes, Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns, and Biofilm Synthesis in Salmonella spp Isolated from Foodborne Outbreaks.

Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol, 2024:4805228, 20 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39346023 | PMCID: PMC11436275

The genomic diversity and antimicrobial resistance of Non-typhoidal Salmonella in humans and food animals in Northern India.

One Health, 19:100892, 12 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39345727 | PMCID: PMC11439553

Salmonella enterica serovars linked with poultry in India: antibiotic resistance profiles and carriage of virulence genes.

Braz J Microbiol, 55(1):969-979, 17 Jan 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 38233640

A comprehensive investigation of the medicinal efficacy of antimicrobial fusion peptides expressed in probiotic bacteria for the treatment of pan drug-resistant (PDR) infections.

Arch Microbiol, 206(3):93, 08 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38329629

The Rise of Non-typhoidal Salmonella Infections in India: Causes, Symptoms, and Prevention.

Cureus, 15(10):e46699, 08 Oct 2023

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 38021876 | PMCID: PMC10630329

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Go to all (21) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

The phenotypic and molecular characteristics of antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium in Henan Province, China.

BMC Infect Dis, 20(1):511, 15 Jul 2020

Cited by: 16 articles | PMID: 32669095 | PMCID: PMC7362628

Emergence and serovar profiling of non-typhoidal Salmonellae (NTS) isolated from gastroenteritis cases-A study from South India.

Infect Dis (Lond), 48(11-12):847-851, 14 Jun 2016

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 27300440

Antimicrobial resistance, plasmid, virulence, multilocus sequence typing and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profiles of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium clinical and environmental isolates from India.

PLoS One, 13(12):e0207954, 12 Dec 2018

Cited by: 13 articles | PMID: 30540810 | PMCID: PMC6291080

Characteristics of nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis in Taiwanese children: A 9-year period retrospective medical record review.

J Infect Public Health, 10(5):518-521, 13 Feb 2017

Cited by: 18 articles | PMID: 28209468

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Japan Initiative for Global Research Network on Infectious Diseases (J-GRID) of the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under grant number JP18fm0108002 (1)

Grant ID: JP18fm0108002

1

1