Abstract

Objective

To determine how gestational age relates to research-identified autism spectrum disorder (ASD-R) in the context of perinatal risk factors.Study design

This is a population-based cohort study using the 1994-2000 Olmsted County Birth Cohort. Children included were born and remained in Olmsted County after age 3 years. ASD-R status was determined from signs and symptoms abstracted from medical and educational records. Cox proportional hazards models were fit to identify associations between perinatal characteristics and ASD-R.Results

The incidence of preterm birth (<37 weeks' gestation) was 8.6% among 7876 children. The cumulative incidence of ASD-R was 3.8% (95% CI 3.3-4.2) at 21 years of age. Compared with children born at full term, the risk of ASD-R appeared to be increased for children born preterm with unadjusted hazard ratios (HRs) of 2.62 (95% CI 0.65-10.57), 1.68 (95% CI 0.54-5.29), and 1.60 (95% CI 1.06-2.40) for children born extremely preterm, very preterm, and moderate-to-late preterm, respectively. In a multivariable model adjusted for perinatal characteristics, the associations were attenuated with adjusted HRs of 1.75 (95% CI 0.41-7.40), 1.24 (95% CI 0.38-4.01), and 1.42 (95% CI 0.93-2.15), for children born extremely preterm, very preterm, and moderate-to-late preterm, respectively. Among children with maternal history available (N = 6851), maternal psychiatric disorder was associated with ASD-R (adjusted HR 1.73, 95% CI 1.24-2.42).Conclusions

The increased risk of ASD-R among children born preterm relative to children born full term was attenuated by infant and maternal characteristics.Free full text

Gestational Age, Perinatal Characteristics, and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Birth Cohort Study

Associated Data

Abstract

Objective:

To determine how gestational age relates to research-identified autism spectrum disorder (ASD-R) in the context of perinatal risk factors

Study design:

This is a population-based cohort study using the 1994–2000 Olmsted County Birth Cohort. Children included were born and remained in Olmsted County after age 3 years. ASD-R status was determined from signs and symptoms abstracted from medical and educational records. Cox proportional hazards models were fit to identify associations between perinatal characteristics and ASD-R.

Results:

The incidence of preterm birth (<37 weeks’ gestation) was 8.6% among 7876 children. The cumulative incidence of ASD-R was 3.8% (95% CI 3.3, 4.2) at 21 years of age. Compared with children born full term, the risk of ASD-R appeared to be increased for children born preterm with unadjusted hazard ratios (HR) of 2.62 (95% CI 0.65, 10.57), 1.68 (95% CI 0.54, 5.29), and 1.60 (95% CI 1.06, 2.40) for children born extremely preterm, very preterm, and moderate to late preterm, respectively. In a multivariable model adjusted for perinatal characteristics, the associations were attenuated with adjusted HRs of 1.75 (95% CI 0.41, 7.40), 1.24 (95% CI 0.38, 4.01), and 1.42 (95% CI 0.93, 2.15), for extremely preterm, very preterm, and moderate to late preterm children, respectively. Among children with maternal history available (N=6851), maternal psychiatric disorder was associated with ASD-R (aHR 1.73, 95% CI 1.24, 2.42).

Conclusions:

The increased risk of ASD-R among preterm children relative to full term children was attenuated by infant and maternal characteristics.

As infants born preterm survive into childhood and adulthood, the focus has shifted from mortality to the long-term morbidities associated with preterm birth (<37 weeks’ gestation). There is evidence that preterm birth itself is a risk factor for autism spectrum disorder (ASD).1–4 ASD refers to a brain-based neurodevelopmental condition characterized by impairments in social interaction and communication in the presence of restricted, repetitive behaviors or interests.5 The prevalence of ASD is at least 1.5% in developed countries.6 A prospective study using active screening and diagnostic assessments found a prevalence of 2.6% whereas parent surveys produced estimates of 3.9% and 2.8%.7–9 The incidence of ASD in extremely preterm (<28 weeks’ gestation) children has been reported to exceed the incidence in the general population.10,11 In a U.S. regional cohort of children with birth weight <2000 grams followed prospectively to age 21 years, the prevalence of ASD was 5%.12 In a Finnish population-based case-control cohort, very preterm children (<32 weeks’ gestation) were 2.5 times more likely to develop ASD (P = .009).13 In a retrospective cohort of children born ≥24 weeks’ gestation in California, the adjusted hazard ratio for ASD was 2.7 (95% CI 1.5–5.0) for children born at 24–26 week’ gestation, 1.4 (95% CI 1.1–1.8) for those born at 27–33 weeks’ gestation, and 1.3 (CI 1.1–1.4) for those born at 34–36 weeks’ gestation relative to children born at 37–41 weeks’ gestation.11

Low gestational age may reflect the vulnerability of the developing brain. Exposures associated with preterm birth, such as maternal and fetal inflammation, may be in one or more of the causal pathways for ASD.14 The multifactorial etiology of ASD has been investigated; however, we do not yet fully understand the complex pathophysiology. Causal pathways for ASD are difficult to elucidate due to etiologic and clinical heterogeneity. Additionally, ASD risk factors interact with genetic predisposition as well as the prenatal and postnatal environments. Preterm birth and ASD may share pathophysiology or perinatal risk factors, e.g. fetal growth deviance, inflammation, infection, malnutrition, hypoxia, and genetic susceptibility. With ASD a growing concern for parents and health care providers alike and with limited population-based data in the U.S., the objective of this study was to evaluate perinatal risk factors for ASD using a population-based cohort with a focus on gestational age at birth.

Methods

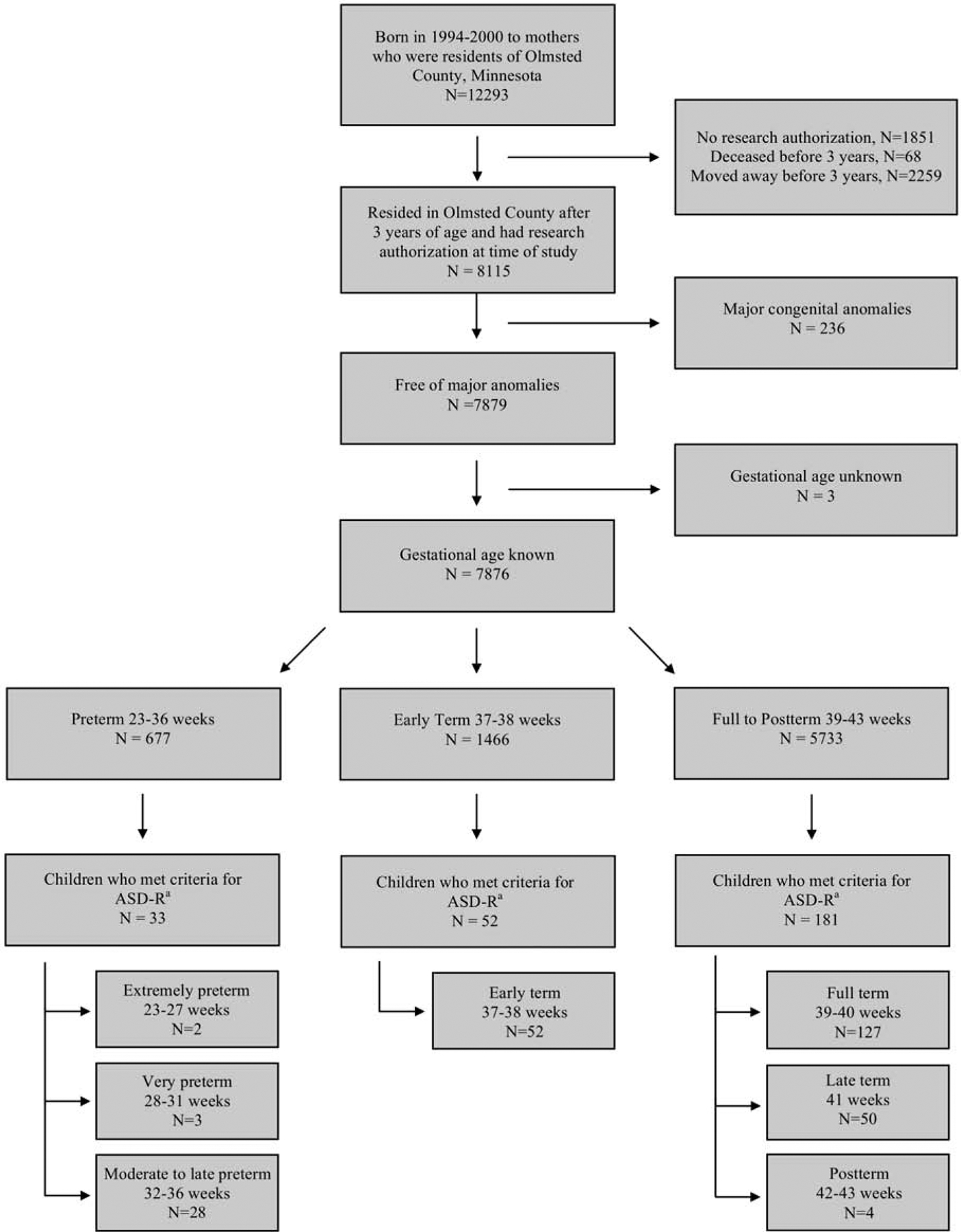

This is a population-based retrospective cohort study using the 1994–2000 Olmsted County Birth Cohort. Olmsted County is located in southeast Minnesota and is home to the Mayo Clinic. The cohort was identified using birth certificate data obtained from the Minnesota Department of Health and using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP). The REP is a medical records-linkage system that includes outpatient and inpatient records from providers in the community, including Mayo Clinic, Olmsted Medical Center, their affiliated hospitals, as well as smaller care providers.15–17 Children were included if they were born to mothers who were residents of Olmsted County at delivery, remained in Olmsted County after age 3 years, and had active research authorization to access their medical records at the initiation of this study. Children were excluded if gestational age was not available on the birth certificate or if they had major congenital anomalies that occurred during intrauterine life (Figure 1). The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center Institutional Review Boards.

Flow chart of subjects.

a ASD-R: research-identified autism spectrum disorder.

Of the 7876 individuals free of major anomalies and with known gestational age who resided in Olmsted County at 3 years of age, 266 met criteria for ASD-R in this retrospective study with passive follow-up to 21 years of age. The median age at which the 266 met criteria was 6.5 years (IQR, 4.3–9.2 years). The median duration of follow-up for the remaining 7610 subjects was 17.3 years (IQR, 15.2–19.2 years).

ASD-R Identification

We utilized an epidemiologic approach for identification of research-identified ASD (ASD-R) cases.18 First, we identified neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorder diagnostic codes from medical records and educational disability classification codes from school records. These codes represented conditions with signs and symptoms that overlap with the core social, communicative, and behavioral features of ASD. Next, among individuals with any of the aforementioned codes, we identified individuals with potential ASD. Medical and school records of individuals with potential ASD were manually reviewed to abstract data in a systematic, multi-staged process. The abstractors reviewed the records prior to 21 years of age to identify descriptive phrases that mapped to any of 58 ASD signs/symptoms contributing to the 12 core criteria for autistic disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR).19 Finally, the research team applied the DSM-IVTR-based criteria to the abstracted information to identify ASD-R cases. Likely false-positives were excluded by a manual review process that identified individuals whose signs and symptoms were attributed to other conditions, such as adolescent-onset psychosis, bipolar disorder, or major depression.

Perinatal Risk Factors

The perinatal characteristics were obtained from birth certificate data. Gestational age was divided into seven categories based on guidelines by the World Health Organization and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: extremely preterm (<28 weeks), very preterm (28–31 weeks), moderate to late preterm (32–36 weeks’ gestation), early term (37–38 weeks’ gestation), full term (39–40 weeks’ gestation), late term (41 weeks’ gestation) and postterm (42–43 weeks’ gestation).20,21 Size for gestational age was defined based on the Fenton growth chart for infants with gestational age 23–36 weeks and based on the World Health Organization growth chart for infants with gestational age 37–43 weeks.22,23 Weight gain during pregnancy was defined used a modification of the Institute of Medicine’s recommendations.24 For singleton gestations, weight gain was defined as inappropriately low (<11 pounds for singleton gestation, <25 pounds for multiple gestation), appropriate (11–40 pounds for singleton gestation, 25–54 pounds for multiple gestation), or inappropriately high (≥41 pounds for singleton gestation, ≥55 pounds for multiple gestation). Adequacy of prenatal care utilization index was based on the month prenatal care commenced and the number of visits adjusted for gestational age.25 Perinatal brain injuries and fetal growth restriction were identified through the REP using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis codes.

Additional Perinatal Risk Factor for Mothers with Active Research Authorization

For the subset of the cohort for whom mothers had active research authorization at the initiation of this study, the presence of maternal psychiatric disorders prior to delivery was determined. Clinical diagnoses available through the REP from January 1976 through December 2000 were coded using two different coding systems, ICD-9 and Hospital Adaption of the International Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision. For each of 19 different psychiatric disorders, mothers were classified as having a specific disorder if they had two or more visits greater than 30 days apart with diagnosis codes for that disorder.

Statistical Analyses

Perinatal characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics overall and for the seven gestational age categories identified earlier. The duration of follow-up was calculated from the date of birth to the date the child met the ASD-R criteria prior to 21 years of age. For children who did not meet ASD-R criteria, follow-up was censored at their last clinical visit prior to December 31, 2015 or their 21st birthday, whichever came first. The cumulative incidence of meeting criteria for ASD-R was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method ignoring competing risks. To evaluate the risk effect of gestational age on meeting criteria for ASD-R, a penalized smoothing spline was used to model a potentially nonlinear relationship with gestational age in a Cox proportional hazards model.26

For the remaining analyses, missing values for the perinatal characteristics were handled using multiple imputation. Ten multiple imputation datasets were created using fully conditional specification methods and the Rubin rules were used to combine the results from the Cox proportional hazards models fit using the multiple imputed datasets. Univariate Cox proportional hazards models were fit to evaluate the association between perinatal characteristics (i.e. male sex, gestational age, size for gestational age, 5-minute Apgar score, maternal age, marital status, education level, tobacco use during pregnancy, weight gain during pregnancy, parity, and delivery mode) and ASD-R; the strength of each association was summarized using the hazard ratio (HR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The variables considered in the analysis were identified from the literature as being associated with ASD.1,27–30 Subsequently, a full multivariable model was fit including all of the perinatal characteristics listed above. The univariate and multivariable analysis were repeated on the subset of the cohort for whom mothers had active research authorization at the initiation of this study in order to consider the presence of maternal psychiatric disorders among the risk factors. Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary, NC) and R version 3.4.2 (R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

This study evaluated data from 8,115 children in the 1994–2000 Olmsted County Birth Cohort who resided in Olmsted County at age 3 years (Figure 1). There were 7876 children included in the analysis after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The incidence of preterm birth (<37 weeks’ gestation) was 8.6% in this cohort, which was lower than the national average (11%) for the period.31,32 Moderate to late preterm birth (32–36 weeks’ gestation) accounted for the majority of premature births (N=586, 86.6%) and 7.4% of the entire cohort. The perinatal characteristics obtained from birth certificate data revealed that most of the mothers identified as white race, were married, had education beyond a high school degree, had adequate prenatal care, and did not smoke (Table 1; available at www.jpeds.com). Based on ICD-9 codes in the neonatal period, 44 children (0.6%) had a perinatal brain injury and 34 (0.4%) had fetal growth retardation. Children excluded from the analysis due to moving outside of the county before 3 years of age (N=2259) or due to lack of research authorization (N=1851) were more likely to have mothers who identified as non-white race (13.4% vs 8.4%, p<0.001), Hispanic ethnicity (3.5% vs. 2.3%, p<0.001), or mothers who were born outside of the United States of America (19.9% vs. 11.4%, p<0.001) compared with children included in the analysis (Table 2; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table 1.

Perinatal characteristics obtained from birth certificate data.

| Extremely Preterm 23–27 weeks (N=28) | Very Preterm 28–31 weeks (N=63) | Moderate to Late Preterm 32–36 weeks (N=586) | Early Term 37–38 weeks (N=1466) | Full Term 39–40 weeks (N=4318) | Late Term 41 weeks (N=1276) | Postterm 42–43 weeks (N=139) | Total (N=7876) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant characteristics at birth | ||||||||

| Male sex | 13 (46.4%) | 31 (49.2%) | 315 (53.8%) | 778 (53.1%) | 2168 (50.2%) | 631 (49.5%) | 72 (51.8%) | 4008 (50.9%) |

| Birth weight (grams), median (IQR) | 865 (695, 965) | 1400 (1105, 1620) | 2551 (2215, 2900) | 3232 (2948, 3520) | 3544 (3260, 3850) | 3700 (3402, 3996) | 3730 (3445, 4050) | 3460 (3120, 3799) |

| Size for gestational agea | ||||||||

Small for gestational age Small for gestational age | 2 (7.1%) | 5 (7.9%) | 19 (3.2%) | 19 (1.3%) | 57 (1.3%) | 24 (1.9%) | 11 (7.9%) | 137 (1.7%) |

Appropriate for gestational age Appropriate for gestational age | 22 (78.6%) | 53 (84.1%) | 495 (84.5%) | 730 (49.8%) | 3117 (72.2%) | 1073 (84.1%) | 126 (90.6%) | 5616 (71.3%) |

Large for gestational age Large for gestational age | 4 (14.3%) | 5 (7.9%) | 72 (12.3%) | 717 (48.9%) | 1144 (26.5%) | 179 (14.0%) | 2 (1.4%) | 2123 (27.0%) |

| APGAR score at 5 minutes | ||||||||

Less than 7 Less than 7 | 3 (10.7%) | 2 (3.2%) | 16 (2.7%) | 20 (1.4%) | 22 (0.5%) | 7 (0.5%) | 3 (2.2%) | 73 (0.9%) |

7 or greater 7 or greater | 22 (78.6%) | 60 (95.2%) | 566 (96.6%) | 1442 (98.4%) | 4281 (99.1%) | 1265 (99.1%) | 136 (97.8%) | 7772 (98.7%) |

Not recorded Not recorded | 3 (10.7%) | 1 (1.6%) | 4 (0.7%) | 4 (0.3%) | 15 (0.3%) | 4 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 31 (0.4%) |

| Maternal characteristics at delivery | ||||||||

| Maternal age (years) | ||||||||

Mean (SD) Mean (SD) | 26.6 (4.5) | 29.4 (4.6) | 29.7 (5.8) | 29.2 (5.8) | 28.8 (5.5) | 28.5 (5.3) | 28.2 (6.5) | 28.9 (5.6) |

Less than 20 years Less than 20 years | 1 (3.6%) | 5 (7.9%) | 33 (5.6%) | 80 (5.5%) | 278 (6.4%) | 92 (7.2%) | 14 (10.1%) | 503 (6.4%) |

20–34 years 20–34 years | 27 (96.4%) | 53 (84.1%) | 432 (73.7%) | 1122 (76.5%) | 3419 (79.2%) | 1023 (80.2%) | 100 (71.9%) | 6176 (78.4%) |

35 years and greater 35 years and greater | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (7.9%) | 121 (20.6%) | 264 (18.0%) | 621 (14.4%) | 161 (12.6%) | 25 (18.0%) | 1197 (15.2%) |

| Maternal race | ||||||||

White White | 25 (89.3%) | 59 (93.7%) | 551 (94.0%) | 1311 (89.4%) | 3940 (91.2%) | 1175 (92.1%) | 116 (83.5%) | 7177 (91.1%) |

Asian or Pacific Islander Asian or Pacific Islander | 1 (3.6%) | 2 (3.2%) | 16 (2.7%) | 97 (6.6%) | 231 (5.3%) | 49 (3.8%) | 6 (4.3%) | 402 (5.1%) |

Black or African American Black or African American | 2 (7.1%) | 2 (3.2%) | 14 (2.4%) | 47 (3.2%) | 119 (2.8%) | 47 (3.7%) | 17 (12.2%) | 248 (3.1%) |

American Indian or Alaskan Native American Indian or Alaskan Native | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.1%) | 9 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (0.2%) |

Not recorded Not recorded | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (0.7%) | 9 (0.6%) | 19 (0.4%) | 4 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 36 (0.5%) |

| Hispanic ethnicity of mother | ||||||||

No No | 27 (96.4%) | 62 (98.4%) | 572 (97.6%) | 1428 (97.4%) | 4218 (97.7%) | 1246 (97.6%) | 133 (95.7%) | 7686 (97.6%) |

Yes Yes | 1 (3.6%) | 1 (1.6%) | 13 (2.2%) | 36 (2.5%) | 97 (2.2%) | 27 (2.1%) | 5 (3.6%) | 180 (2.3%) |

Not recorded Not recorded | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.1%) | 3 (0.1%) | 3 (0.2%) | 1 (0.7%) | 10 (0.1%) |

| Nativity status of mother | ||||||||

US born US born | 26 (92.9%) | 58 (92.1%) | 536 (91.5%) | 1265 (86.3%) | 3833 (88.8%) | 1135 (88.9%) | 111 (79.9%) | 6964 (88.4%) |

US territory born US territory born | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | 9 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (0.2%) |

Foreign born Foreign born | 2 (7.1%) | 4 (6.3%) | 49 (8.4%) | 199 (13.6%) | 472 (10.9%) | 140 (11.0%) | 28 (20.1%) | 894 (11.4%) |

Not recorded Not recorded | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) | 4 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (0.1%) |

| Married status | 19 (67.9%) | 51 (81.0%) | 475 (81.1%) | 1210 (82.5%) | 3538 (81.9%) | 1050 (82.3%) | 104 (74.8%) | 6447 (81.9%) |

| Maternal education level | ||||||||

Less than high school Less than high school | 2 (7.1%) | 3 (4.8%) | 46 (7.8%) | 125 (8.5%) | 330 (7.6%) | 91 (7.1%) | 18 (12.9%) | 615 (7.8%) |

High school graduate High school graduate | 11 (39.3%) | 16 (25.4%) | 116 (19.8%) | 295 (20.1%) | 879 (20.4%) | 271 (21.2%) | 46 (33.1%) | 1634 (20.7%) |

1–3 years of college 1–3 years of college | 11 (39.3%) | 14 (22.2%) | 160 (27.3%) | 416 (28.4%) | 1130 (26.2%) | 346 (27.1%) | 28 (20.1%) | 2105 (26.7%) |

4 years or more of college 4 years or more of college | 3 (10.7%) | 28 (44.4%) | 253 (43.2%) | 593 (40.5%) | 1889 (43.7%) | 545 (42.7%) | 46 (33.1%) | 3357 (42.6%) |

Not recorded Not recorded | 1 (3.6%) | 2 (3.2%) | 11 (1.9%) | 37 (2.5%) | 90 (2.1%) | 23 (1.8%) | 1 (0.7%) | 165 (2.1%) |

| Alcohol use during pregnancy | ||||||||

No No | 28 (100.0%) | 62 (98.4%) | 566 (96.6%) | 1443 (98.4%) | 4233 (98.0%) | 1250 (98.0%) | 131 (94.2%) | 7713 (97.9%) |

Yes Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (1.9%) | 12 (0.8%) | 47 (1.1%) | 17 (1.3%) | 4 (2.9%) | 91 (1.2%) |

Not recorded Not recorded | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.6%) | 9 (1.5%) | 11 (0.8%) | 38 (0.9%) | 9 (0.7%) | 4 (2.9%) | 72 (0.9%) |

| Tobacco use during pregnancy | ||||||||

No No | 23 (82.1%) | 57 (90.5%) | 520 (88.7%) | 1319 (90.0%) | 3903 (90.4%) | 1152 (90.3%) | 119 (85.6%) | 7093 (90.1%) |

Yes Yes | 5 (17.9%) | 5 (7.9%) | 56 (9.6%) | 134 (9.1%) | 375 (8.7%) | 115 (9.0%) | 16 (11.5%) | 706 (9.0%) |

Not recorded Not recorded | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.6%) | 10 (1.7%) | 13 (0.9%) | 40 (0.9%) | 9 (0.7%) | 4 (2.9%) | 77 (1.0%) |

| Illicit drug use during pregnancy | ||||||||

No No | 26 (92.9%) | 61 (96.8%) | 571 (97.4%) | 1447 (98.7%) | 4262 (98.7%) | 1256 (98.4%) | 134 (96.4%) | 7757 (98.5%) |

Yes Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.5%) | 5 (0.3%) | 12 (0.3%) | 6 (0.5%) | 1 (0.7%) | 27 (0.3%) |

Not recorded Not recorded | 2 (7.1%) | 2 (3.2%) | 12 (2.0%) | 14 (1.0%) | 44 (1.0%) | 14 (1.1%) | 4 (2.9%) | 92 (1.2%) |

| Singleton or multiple gestation | ||||||||

Singleton Singleton | 17 (60.7%) | 27 (42.9%) | 426 (72.7%) | 1353 (92.3%) | 4293 (99.4%) | 1276 (100.0%) | 139 (100.0%) | 7531 (95.6%) |

Twins Twins | 8 (28.6%) | 23 (36.5%) | 133 (22.7%) | 112 (7.6%) | 24 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 300 (3.8%) |

Higher order multiples Higher order multiples | 3 (10.7%) | 13 (20.6%) | 27 (4.6%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 45 (0.6%) |

| Weight gain during pregnancyb | ||||||||

Inappropriately low Inappropriately low | 7 (25.0%) | 15 (23.8%) | 43 (7.3%) | 75 (5.1%) | 161 (3.7%) | 39 (3.1%) | 5 (3.6%) | 345 (4.4%) |

Appropriate Appropriate | 15 (53.6%) | 36 (57.1%) | 435 (74.2%) | 1130 (77.1%) | 3217 (74.5%) | 927 (72.6%) | 98 (70.5%) | 5858 (74.4%) |

Inappropriately high Inappropriately high | 1 (3.6%) | 1 (1.6%) | 56 (9.6%) | 136 (9.3%) | 623 (14.4%) | 222 (17.4%) | 25 (18.0%) | 1064 (13.5%) |

Not recorded Not recorded | 5 (17.9%) | 11 (17.5%) | 52 (8.9%) | 125 (8.5%) | 317 (7.3%) | 88 (6.9%) | 11 (7.9%) | 609 (7.7%) |

| Gravidac | ||||||||

0 0 | 10 (35.7%) | 19 (30.2%) | 183 (31.2%) | 433 (29.5%) | 1339 (31.0%) | 493 (38.6%) | 57 (41.0%) | 2534 (32.2%) |

1 1 | 5 (17.9%) | 17 (27.0%) | 166 (28.3%) | 438 (29.9%) | 1323 (30.6%) | 340 (26.6%) | 37 (26.6%) | 2326 (29.5%) |

2 2 | 5 (17.9%) | 13 (20.6%) | 108 (18.4%) | 259 (17.7%) | 827 (19.2%) | 240 (18.8%) | 17 (12.2%) | 1469 (18.7%) |

3+ 3+ | 8 (28.6%) | 13 (20.6%) | 123 (21.0%) | 319 (21.8%) | 801 (18.6%) | 196 (15.4%) | 28 (20.1%) | 1488 (18.9%) |

Not recorded Not recorded | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.6%) | 6 (1.0%) | 17 (1.2%) | 28 (0.6%) | 7 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 59 (0.7%) |

| Parityc | ||||||||

0 0 | 13 (46.4%) | 27 (42.9%) | 246 (42.0%) | 545 (37.2%) | 1669 (38.7%) | 584 (45.8%) | 68 (48.9%) | 3152 (40.0%) |

1 1 | 9 (32.1%) | 17 (27.0%) | 193 (32.9%) | 485 (33.1%) | 1494 (34.6%) | 377 (29.5%) | 34 (24.5%) | 2609 (33.1%) |

2 2 | 2 (7.1%) | 9 (14.3%) | 93 (15.9%) | 250 (17.1%) | 747 (17.3%) | 198 (15.5%) | 17 (12.2%) | 1316 (16.7%) |

3+ 3+ | 4 (14.3%) | 9 (14.3%) | 50 (8.5%) | 176 (12.0%) | 388 (9.0%) | 112 (8.8%) | 20 (14.4%) | 759 (9.6%) |

Not recorded Not recorded | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.6%) | 4 (0.7%) | 10 (0.7%) | 20 (0.5%) | 5 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 40 (0.5%) |

| Adequacy of prenatal cared | ||||||||

Inadequate Inadequate | 1 (3.6%) | 4 (6.3%) | 29 (4.9%) | 80 (5.5%) | 228 (5.3%) | 77 (6.0%) | 13 (9.4%) | 432 (5.5%) |

Intermediate Intermediate | 2 (7.1%) | 2 (3.2%) | 31 (5.3%) | 116 (7.9%) | 703 (16.3%) | 244 (19.1%) | 31 (22.3%) | 1129 (14.3%) |

Adequate Adequate | 6 (21.4%) | 14 (22.2%) | 120 (20.5%) | 573 (39.1%) | 2297 (53.2%) | 699 (54.8%) | 65 (46.8%) | 3774 (47.9%) |

Adequate plus Adequate plus | 13 (46.4%) | 34 (54.0%) | 328 (56.0%) | 505 (34.4%) | 568 (13.2%) | 108 (8.5%) | 8 (5.8%) | 1564 (19.9%) |

Incomplete information Incomplete information | 6 (21.4%) | 9 (14.3%) | 78 (13.3%) | 192 (13.1%) | 522 (12.1%) | 148 (11.6%) | 22 (15.8%) | 977 (12.4%) |

| Mode of delivery | ||||||||

Vaginal Vaginal | 11 (39.3%) | 17 (27.0%) | 404 (68.9%) | 1196 (81.6%) | 3707 (85.8%) | 1114 (87.3%) | 112 (80.6%) | 6561 (83.3%) |

Cesarean section Cesarean section | 17 (60.7%) | 46 (73.0%) | 178 (30.4%) | 261 (17.8%) | 591 (13.7%) | 155 (12.1%) | 26 (18.7%) | 1274 (16.2%) |

Not recorded Not recorded | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (0.7%) | 9 (0.6%) | 20 (0.5%) | 7 (0.5%) | 1 (0.7%) | 41 (0.5%) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles); SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Perinatal characteristics of children included versus not included in the primary analysis.

| Deceased before 3 years (N=68) | Included (N=7876) | Excluded | P-value Included vs. Excludeda | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excluded Total (N=4110) | Moved before 3 years (N=2259) | No research authorization (N=1851) | ||||

| Infant characteristics at birth | ||||||

| Gestational age | 0.93 | |||||

Extremely preterm (<27 weeks) Extremely preterm (<27 weeks) | 25 (36.8%) | 28 (0.4%) | 9 (0.2%) | 3 (0.1%) | 6 (0.3%) | |

Very preterm (28–31 weeks) Very preterm (28–31 weeks) | 7 (10.3%) | 63 (0.8%) | 24 (0.6%) | 13 (0.6%) | 11 (0.6%) | |

Moderate to late preterm (32–36 weeks) Moderate to late preterm (32–36 weeks) | 9 (13.2%) | 586 (7.4%) | 291 (7.1%) | 161 (7.1%) | 130 (7.0%) | |

Early term (37–38 weeks) Early term (37–38 weeks) | 6 (8.8%) | 1466 (18.6%) | 817 (19.9%) | 440 (19.5%) | 377 (20.4%) | |

Full term (39–40 weeks) Full term (39–40 weeks) | 15 (22.1%) | 4318 (54.8%) | 2192 (53.3%) | 1225 (54.2%) | 967 (52.2%) | |

Late term (41 weeks) Late term (41 weeks) | 4 (5.9%) | 1276 (16.2%) | 627 (15.3%) | 342 (15.1%) | 285 (15.4%) | |

Postterm (≥42 weeks) Postterm (≥42 weeks) | 0 (0.0%) | 139 (1.8%) | 112 (2.7%) | 56 (2.5%) | 56 (3.0%) | |

Not documented Not documented | 2 (2.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 38 (0.9%) | 19 (0.8%) | 19 (1.0%) | |

| Male sex | 33 (48.5%) | 4008 (50.9%) | 2123 (51.7%) | 1200 (53.1%) | 923 (49.9%) | 0.43 |

| Birth weight (grams), median (IQR) | 2080 (680, 3235) | 3460 (3120, 3799) | 3450 (3090, 3770) | 3445 (3095, 3770) | 3450 (3080, 3770) | 0.015 |

| Size for gestational ageb | 0.25 | |||||

Small for gestational age Small for gestational age | 5 (7.4%) | 137 (1.7%) | 88 (2.1%) | 43 (1.9%) | 45 (2.4%) | |

Appropriate for gestational age Appropriate for gestational age | 38 (55.9%) | 5616 (71.3%) | 2899 (70.5%) | 1602 (70.9%) | 1297 (70.1%) | |

Large for gestational age Large for gestational age | 9 (13.2%) | 2123 (27.0%) | 1079 (26.3%) | 590 (26.1%) | 489 (26.4%) | |

Not determined Not determined | 16 (23.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 44 (1.1%) | 24 (1.1%) | 20 (1.1%) | |

| APGAR score at 5 minutes | 0.52 | |||||

Less than 7 Less than 7 | 39 (57.4%) | 73 (0.9%) | 43 (1.0%) | 21 (0.9%) | 22 (1.2%) | |

7 or greater 7 or greater | 28 (41.2%) | 7772 (98.7%) | 4041 (98.3%) | 2225 (98.5%) | 1816 (98.1%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 1 (1.5%) | 31 (0.4%) | 26 (0.6%) | 13 (0.6%) | 13 (0.7%) | |

| Maternal characteristics at delivery | ||||||

Mean (SD) Mean (SD) | 27.1 (6.1) | 28.9 (5.6) | 28.7 (5.5) | 28.6 (5.2) | 28.8 (6.0) | 0.11 |

Less than 20 years Less than 20 years | 9 (13.2%) | 503 (6.4%) | 252 (6.1%) | 117 (5.2%) | 135 (7.3%) | |

20–34 years 20–34 years | 52 (76.5%) | 6176 (78.4%) | 3251 (79.1%) | 1869 (82.7%) | 1382 (74.7%) | |

35 years and greater 35 years and greater | 7 (10.3%) | 1197 (15.2%) | 606 (14.7%) | 272 (12.0%) | 334 (18.0%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.0%) | 1 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Maternal race | <0.001 | |||||

White White | 56 (82.4%) | 7177 (91.1%) | 3531 (85.9%) | 1886 (83.5%) | 1645 (88.9%) | |

Asian or Pacific Islander Asian or Pacific Islander | 5 (7.4%) | 402 (5.1%) | 353 (8.6%) | 233 (10.3%) | 120 (6.5%) | |

Black or African American Black or African American | 5 (7.4%) | 248 (3.1%) | 177 (4.3%) | 109 (4.8%) | 68 (3.7%) | |

American Indian or Alaskan Native American Indian or Alaskan Native | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (0.2%) | 19 (0.5%) | 10 (0.4%) | 9 (0.5%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 2 (2.9%) | 36 (0.5%) | 30 (0.7%) | 21 (0.9%) | 9 (0.5%) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity of mother | <0.001 | |||||

No No | 66 (97.1%) | 7686 (97.6%) | 3955 (96.2%) | 2152 (95.3%) | 1803 (97.4%) | |

Yes Yes | 1 (1.5%) | 180 (2.3%) | 143 (3.5%) | 100 (4.4%) | 43 (2.3%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 1 (1.5%) | 10 (0.1%) | 12 (0.3%) | 7 (0.3%) | 5 (0.3%) | |

| Nativity status of mother | <0.001 | |||||

US born US born | 60 (88.2%) | 6964 (88.4%) | 3283 (79.9%) | 1692 (74.9%) | 1591 (86.0%) | |

US territory born US territory born | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (0.2%) | 9 (0.2%) | 8 (0.4%) | 1 (0.1%) | |

Foreign born Foreign born | 8 (11.8%) | 894 (11.4%) | 816 (19.9%) | 557 (24.7%) | 259 (14.0%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (0.1%) | 2 (0.0%) | 2 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Married status | 49 (72.1%) | 6447 (81.9%) | 3343 (81.3%) | 1888 (83.6%) | 1455 (78.6%) | 0.49 |

| Maternal education level | 0.009 | |||||

Less than high school Less than high school | 5 (7.4%) | 615 (7.8%) | 350 (8.5%) | 175 (7.7%) | 175 (9.5%) | |

High school graduate High school graduate | 22 (32.4%) | 1634 (20.7%) | 783 (19.1%) | 371 (16.4%) | 412 (22.3%) | |

1–3 years of college 1–3 years of college | 22 (32.4%) | 2105 (26.7%) | 1024 (24.9%) | 452 (20.0%) | 572 (30.9%) | |

4 years or more of college 4 years or more of college | 15 (22.1%) | 3357 (42.6%) | 1837 (44.7%) | 1203 (53.3%) | 634 (34.3%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 4 (5.9%) | 165 (2.1%) | 116 (2.8%) | 58 (2.6%) | 58 (3.1%) | |

| Alcohol use during pregnancy | 0.33 | |||||

No No | 61 (89.7%) | 7713 (97.9%) | 4013 (97.6%) | 2206 (97.7%) | 1807 (97.6%) | |

Yes Yes | 5 (7.4%) | 91 (1.2%) | 56 (1.4%) | 32 (1.4%) | 24 (1.3%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 2 (2.9%) | 72 (0.9%) | 41 (1.0%) | 21 (0.9%) | 20 (1.1%) | |

| Tobacco use during pregnancy | 0.94 | |||||

No No | 56 (82.4%) | 7093 (90.1%) | 3705 (90.1%) | 2066 (91.5%) | 1639 (88.5%) | |

Yes Yes | 10 (14.7%) | 706 (9.0%) | 367 (8.9%) | 174 (7.7%) | 193 (10.4%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 2 (2.9%) | 77 (1.0%) | 38 (0.9%) | 19 (0.8%) | 19 (1.0%) | |

| Illicit drug use during pregnancy | <0.001 | |||||

No No | 66 (97.1%) | 7757 (98.5%) | 4018 (97.8%) | 2207 (97.7%) | 1811 (97.8%) | |

Yes Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 27 (0.3%) | 35 (0.9%) | 23 (1.0%) | 12 (0.6%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 2 (2.9%) | 92 (1.2%) | 57 (1.4%) | 29 (1.3%) | 28 (1.5%) | |

| Singleton or multiple gestation | 0.036 | |||||

Singleton Singleton | 56 (82.4%) | 7531 (95.6%) | 3970 (96.6%) | 2183 (96.6%) | 1787 (96.5%) | |

Twins Twins | 9 (13.2%) | 300 (3.8%) | 123 (3.0%) | 64 (2.8%) | 59 (3.2%) | |

Higher order multiples Higher order multiples | 3 (4.4%) | 45 (0.6%) | 17 (0.4%) | 12 (0.5%) | 5 (0.3%) | |

| Weight gain during pregnancyc | 0.34 | |||||

Inappropriately low Inappropriately low | 19 (27.9%) | 345 (4.4%) | 188 (4.6%) | 87 (3.9%) | 101 (5.5%) | |

Appropriate Appropriate | 30 (44.1%) | 5858 (74.4%) | 3112 (75.7%) | 1711 (75.7%) | 1401 (75.7%) | |

Inappropriately high Inappropriately high | 5 (7.4%) | 1064 (13.5%) | 521 (12.7%) | 296 (13.1%) | 225 (12.2%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 14 (20.6%) | 609 (7.7%) | 289 (7.0%) | 165 (7.3%) | 124 (6.7%) | |

| Gravidad | 0.94 | |||||

0 0 | 18 (26.5%) | 2534 (32.2%) | 1334 (32.5%) | 742 (32.8%) | 592 (32.0%) | |

1 1 | 18 (26.5%) | 2326 (29.5%) | 1218 (29.6%) | 645 (28.6%) | 573 (31.0%) | |

2 2 | 14 (20.6%) | 1469 (18.7%) | 763 (18.6%) | 422 (18.7%) | 341 (18.4%) | |

3+ 3+ | 17 (25.0%) | 1488 (18.9%) | 757 (18.4%) | 433 (19.2%) | 324 (17.5%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 1 (1.5%) | 59 (0.7%) | 38 (0.9%) | 17 (0.8%) | 21 (1.1%) | |

| Parityd | 0.53 | |||||

0 0 | 25 (36.8%) | 3152 (40.0%) | 1661 (40.4%) | 910 (40.3%) | 751 (40.6%) | |

1 1 | 20 (29.4%) | 2609 (33.1%) | 1360 (33.1%) | 742 (32.8%) | 618 (33.4%) | |

2 2 | 12 (17.6%) | 1316 (16.7%) | 647 (15.7%) | 355 (15.7%) | 292 (15.8%) | |

3+ 3+ | 10 (14.7%) | 759 (9.6%) | 415 (10.1%) | 241 (10.7%) | 174 (9.4%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 1 (1.5%) | 40 (0.5%) | 27 (0.7%) | 11 (0.5%) | 16 (0.9%) | |

| Adequacy of prenatal caree | <0.001 | |||||

Inadequate Inadequate | 5 (7.4%) | 432 (5.5%) | 318 (7.7%) | 219 (9.7%) | 99 (5.3%) | |

Intermediate Intermediate | 6 (8.8%) | 1129 (14.3%) | 643 (15.6%) | 380 (16.8%) | 263 (14.2%) | |

Adequate Adequate | 17 (25.0%) | 3774 (47.9%) | 1825 (44.4%) | 978 (43.3%) | 847 (45.8%) | |

Adequate plus Adequate plus | 32 (47.1%) | 1564 (19.9%) | 750 (18.2%) | 379 (16.8%) | 371 (20.0%) | |

Incomplete information Incomplete information | 8 (11.8%) | 977 (12.4%) | 574 (14.0%) | 303 (13.4%) | 271 (14.6%) | |

| Mode of delivery | 0.37 | |||||

Vaginal Vaginal | 48 (70.6%) | 6561 (83.3%) | 3392 (82.5%) | 1865 (82.6%) | 1527 (82.5%) | |

Cesarean section Cesarean section | 16 (23.5%) | 1274 (16.2%) | 690 (16.8%) | 381 (16.9%) | 309 (16.7%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 4 (5.9%) | 41 (0.5%) | 28 (0.7%) | 13 (0.6%) | 15 (0.8%) | |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles); SD, standard deviation.

Risk factors for ASD-R

Among the 7876 children, 266 met criteria for ASD-R in this retrospective study with passive follow-up. The median age at which children met ASD-R criteria was 6.5 years (IQR, 4.3–9.2 years). The median age at last follow-up for children who did not meet ASD-R criteria was 17.3 years (IQR, 15.2–19.2 years). The cumulative incidence of ASD-R was 1.1% (95% CI 0.9–1.4), 2.8% (95% CI 2.5 −3.2%), 3.5% (95% CI 3.1–3.9), and 3.8% (95% CI 3.3–4.2) at 5, 10, 15, and 21 years of age, respectively.

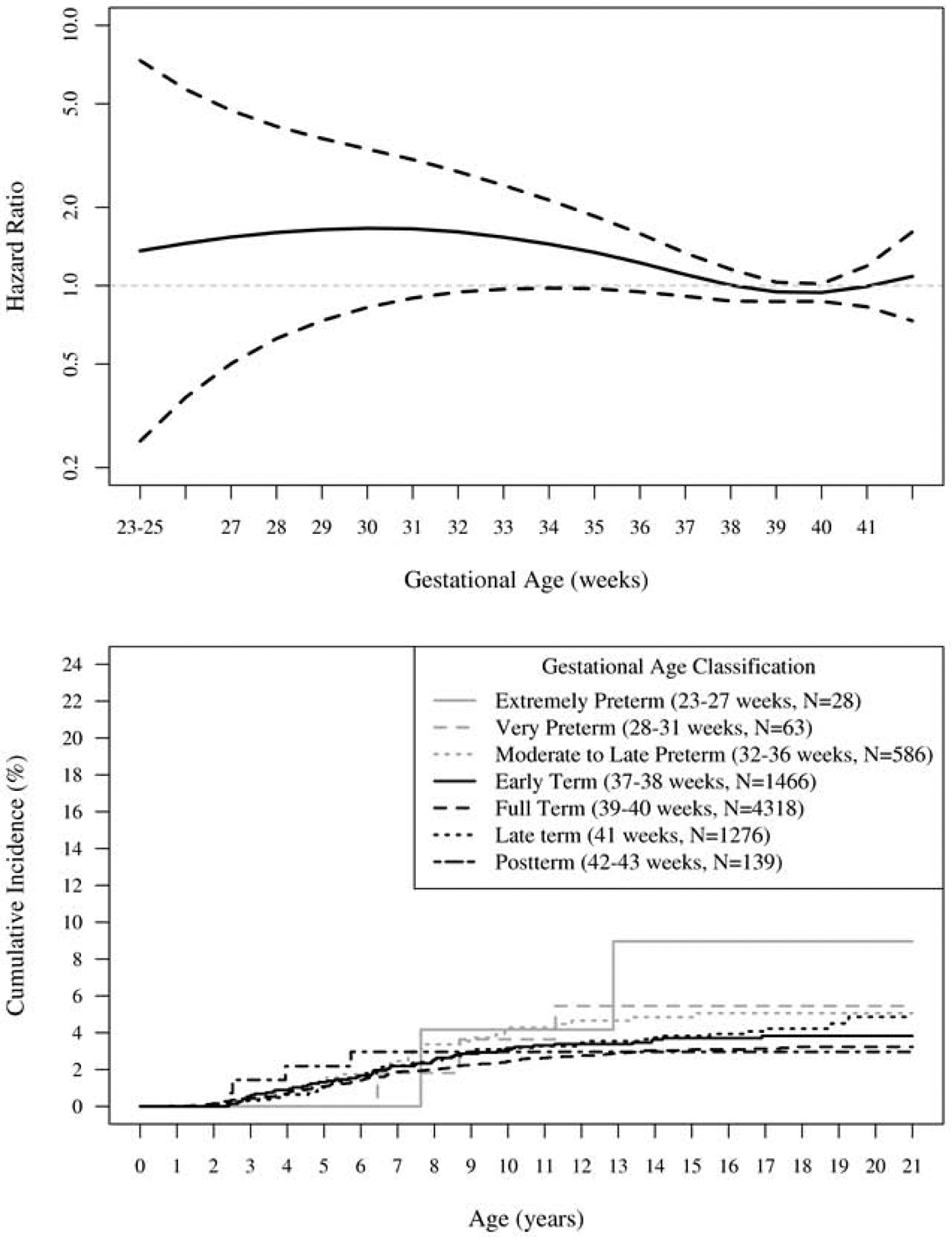

Figure 2, ,AA depicts the hazard ratio for meeting criteria for ASD-R across the range of gestational ages relative to 40 weeks’ gestation, which was set as the reference with a HR of 1.0. The risk of ASD-R was highest for children born at younger gestational ages, however the 95% confidence intervals (dashed lines) were wider for younger gestational ages given that only 1.2% (91/7876) of the cohort was born at <32 weeks’ gestation. Figure 2, ,BB presents the cumulative incidence of meeting criteria for ASD-R according to gestational age categories. Compared with children born full term, the risk of ASD-R appeared to be increased for children born preterm: extremely preterm HR 2.62 (95% CI 0.65, 10.57), very preterm HR 1.68 (95% CI 0.54, 5.29), and moderate to late preterm HR 1.60 (95% CI 1.06, 2.40). When the preterm categories were combined, the hazard ratio for preterm compared with full term was 1.64 (95% CI 1.12, 2.41).

Hazard ratio and cumulative incidence of ASD-R by gestational age.

A (top). Hazard ratio for ASD-R by gestational age. Full term (39–40 weeks) was set as the reference with a HR of 1.0.

B (bottom). Cumulative incidence of ASD-R by gestational age categories.

In addition to preterm birth, the univariate analysis revealed male sex, maternal unmarried status, maternal education level, tobacco use during pregnancy, and inappropriately low weight gain during pregnancy were associated with an increased risk of ASD-R (Table 3). In the multivariable analysis, the association between preterm birth and ASD-R was attenuated, with an adjusted HR (aHR) of 1.75 (95% CI 0.41, 7.40) for extremely preterm, 1.24 (95% CI 0.38, 4.01) for very preterm, and 1.42 (95% CI 0.93, 2.15) for children born moderate to late preterm compared with children born full term. When the preterm categories were combined, the aHR for preterm compared with full term was 1.42 (95% CI 0.95, 2.11). Male sex, maternal unmarried status, and tobacco use during pregnancy were significantly associated with an increased risk of ASD-R (Table 3). Conversely, maternal age <20 years was significantly associated with a decreased risk of ASD-R (aHR 0.55, 95% CI 0.31–0.97) compared with the reference maternal age of 20–34 years.

Table 3.

Analysis of perinatal characteristics for an association with ASD-R among individuals meeting inclusion criteria (N=7876).

| Characteristic | Total person- years prior to age 21 years | No. meeting criteria for ASD-R by age 21 years | Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | |||

| Infant characteristics | ||||||

| Sex | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

Male Male | 62,748 | 201 | 3.06 (2.31, 4.05) | 3.10 (2.35, 4.11) | ||

Female Female | 62,842 | 65 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Gestational age | 0.20 | 0.48 | ||||

Extremely preterm (23–27 weeks) Extremely preterm (23–27 weeks) | 404 | 2 | 2.62 (0.65, 10.57) | 1.75 (0.41, 7.40) | ||

Very preterm (28–31 weeks) Very preterm (28–31 weeks) | 966 | 3 | 1.68 (0.54, 5.29) | 1.24 (0.38, 4.01) | ||

Moderate to late preterm (32–36 weeks) Moderate to late preterm (32–36 weeks) | 9,524 | 28 | 1.60 (1.06, 2.40) | 1.42 (0.93, 2.15) | ||

Early term (37–38 weeks) Early term (37–38 weeks) | 23,516 | 52 | 1.20 (0.87, 1.66) | 1.16 (0.83, 1.62) | ||

Full term (39–40 weeks) Full term (39–40 weeks) | 68,984 | 127 | Referent | Referent | ||

Late term (41 weeks) Late term (41 weeks) | 20,104 | 50 | 1.34 (0.97, 1.86) | 1.35 (0.97, 1.88) | ||

Postterm (42–43 weeks) Postterm (42–43 weeks) | 2,091 | 4 | 1.02 (0.38, 2.76) | 0.84 (0.31, 2.29) | ||

| Size for gestational agea | 0.28 | 0.82 | ||||

Small for gestational age Small for gestational age | 2,171 | 7 | 1.48 (0.70, 3.15) | 1.16 (0.69, 1.96) | ||

Appropriate for gestational age Appropriate for gestational age | 89,393 | 196 | Referent | Referent | ||

Large for gestational age Large for gestational age | 34,025 | 63 | 0.85 (0.64, 1.13) | 0.92 (0.68, 1.25) | ||

| APGAR at 5 minutes | 0.34 | 0.73 | ||||

Less than 7 Less than 7 | 1,183 | 4 | 1.62 (0.60, 4.34) | 1.20 (0.43, 3.31) | ||

7 or greater 7 or greater | 124,406 | 262 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Maternal characteristics | ||||||

| Maternal age (years) | 0.92 | 0.035 | ||||

<20 <20 | 7,891 | 18 | 1.05 (0.76, 1.46) | 0.55 (0.31, 0.97) | ||

20–34 20–34 | 98,045 | 205 | Referent | Referent | ||

≥35+ ≥35+ | 19,653 | 43 | 1.07 (0.66, 1.74) | 1.33 (0.94, 1.88) | ||

| Married | <0.001 | 0.007 | ||||

No No | 22,258 | 76 | 1.82 (1.39, 2.37) | 1.57 (1.34, 2.19) | ||

Yes Yes | 103,331 | 190 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Maternal education level | 0.018 | 0.41 | ||||

Less than high school Less than high school | 9,464 | 27 | 1.64 (1.06, 2.54) | 1.40 (0.83, 2.37) | ||

High school graduate High school graduate | 26,689 | 70 | 1.57 (1.14, 2.15) | 1.32 (0.92, 1.88) | ||

1–3 years of college 1–3 years of college | 35,205 | 78 | 1.33 (0.98, 1.80) | 1.18 (0.86, 1.62) | ||

4 or more years of college 4 or more years of college | 54,231 | 91 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Tobacco use during pregnancy | <0.001 | 0.019 | ||||

No No | 114,117 | 222 | Referent | Referent | ||

Yes Yes | 11,472 | 44 | 1.97 (1.42, 2.72) | 1.53 (1.07, 2.18) | ||

| Weight gain during pregnancyb | 0.030 | 0.08 | ||||

Inappropriately low Inappropriately low | 5,676 | 22 | 1.85 (1.17, 2.93) | 1.69 (1.05, 2.71) | ||

Appropriate Appropriate | 101,330 | 206 | Referent | Referent | ||

Inappropriately high Inappropriately high | 18,583 | 38 | 1.02 (0.72, 1.44) | 0.93 (0.65, 1.34) | ||

| Parityc | 0.05 | 0.06 | ||||

0 0 | 49,983 | 129 | 1.37 (0.88, 2.13) | 1.63 (1.01, 2.62) | ||

1 1 | 42,083 | 75 | 0.95 (0.59, 1.51) | 1.17 (0.72, 1.91) | ||

2 2 | 21,350 | 39 | 0.98 (0.58, 1.63) | 1.16 (0.69, 1.96) | ||

3+ 3+ | 12,173 | 23 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Mode of delivery | 0.09 | 0.43 | ||||

Vaginal Vaginal | 105,418 | 213 | Referent | Referent | ||

Cesarean section Cesarean section | 20,171 | 53 | 1.30 (0.96, 1.75) | 1.13 (0.83, 1.55) | ||

Abbreviations: ASD-R, research-identified autism spectrum disorder; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio

Sub-cohort with Maternal Psychiatric History Available

For the subset of mothers with research authorization enabling medical record review for psychiatric disorders (N=6851 deliveries, 87% of the total cohort), the incidence of psychiatric disorders prior to delivery was associated with gestational age (Cochran-Armitage test for trend, p<0.001). In particular, the incidence ranged from 26.1% to 19.6% among the mothers of extremely preterm or moderate to late preterm infants, respectively, and from 12.4% to 8.5% among the mothers of full term or postterm infants (Table 4; available at www.jpeds.com). The most common maternal psychiatric disorders were adjustment disorder (6.1%), mood disorder (5.8%), substance abuse-related disorder (3.6%), and anxiety disorder (1.6%). Based on univariate analysis, the presence of a maternal psychiatric disorder prior to delivery was associated with an increased risk of ASD-R (HR 2.01, 95% CI 1.46–2.77). In the multivariable analysis, this association was slightly attenuated (aHR 1.73, 95% CI 1.24–2.42) but still statistically significant (Table 5). Preterm birth was not significantly associated with ASD-R in the multivariable analysis with adjusted HR ranging from 2.25 (95% CI 0.52, 9.82) for extremely preterm to 1.38 (95% CI 0.85, 2.23) for moderate to late preterm children compared with children born full term. When the preterm categories were combined for those with maternal psychiatric history available, the aHR for preterm compared with full term was 1.42 (95% CI 0.90, 2.23). Mothers with research authorization were older, more likely to identify as white, to be married, to have attained higher education, and to have adequate prenatal care and were less likely to be born outside of the United States of America and less likely to smoke or use alcohol during pregnancy than mothers without research authorization (Table 6; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table 4.

Maternal psychiatric disorders at the time of delivery by gestational age among individuals whose mothers had research authorization (N=6851).

| Maternal Psychiatric Disorder, N (%) | Gestational Age | Total (N=6851) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely Preterm 23–27 weeks (N=23) | Very Preterm 28–31 weeks (N=57) | Moderate to Late Preterm 34–36 weeks (N=509) | Early Term 37–38 weeks (N=1250) | Full Term 39–40 weeks (N=3778) | Late Term 41 weeks (N=1117) | Postterm 42–43 weeks (N=117) | ||

| Adjustment | 3 (13.0) | 5 (8.8) | 47 (9.2) | 76 (6.1) | 220 (5.8) | 64 (5.7) | 6 (5.1) | 421 (6.1) |

| Mood | 4 (17.4) | 8 (14.0) | 46 (9.0) | 86 (6.9) | 199 (5.3) | 48 (4.3) | 3 (2.6) | 394 (5.8) |

| Substance abuse-related | 3 (13.0) | 2 (3.5) | 20 (3.9) | 55 (4.4) | 132 (3.5) | 31 (2.8) | 3 (2.6) | 246 (3.6) |

| Anxiety | 1 (4.3) | 2 (3.5) | 14 (2.8) | 29 (2.3) | 53 (1.4) | 14 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 113 (1.6) |

| Personality | 1 (4.3) | 2 (3.5) | 8 (1.6) | 13 (1.0) | 28 (0.7) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 53 (0.8) |

| Eating | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.5) | 3 (0.6) | 18 (1.4) | 23 (0.6) | 6 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 52 (0.8) |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.8) | 6 (0.5) | 11 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 24 (0.4) |

| Post-traumatic stress | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.8) | 3 (0.2) | 7 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) | 1 (0.9) | 19 (0.3) |

| Phobic | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 15 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (0.3) |

| Obsessive-compulsive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.5) | 4 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (0.2) |

| Suicidal tendencies | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (0.1) |

| Somatoform | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.1) |

| Schizophrenia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.1) |

| Impulse control | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.1) |

| Psychoses | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.0) |

| Conduct | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.0) |

| Tic | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.0) |

| Oppositional | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

| Dissociative | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Any of the above | 6 (26.1%) | 11 (19.3%) | 100 (19.6%) | 185 (14.8) | 469 (12.4) | 121 (10.8) | 10 (8.5) | 902 (13.2) |

Table 5.

Analysis of perinatal characteristics for an association with ASD-R among individuals whose mothers had research authorization (N=6851).

| Characteristic | Total person-years prior to age 21 years | No. meeting criteria for ASD-R by age 21 years | Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | |||

| Infant characteristics | ||||||

| Sex | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

Male Male | 55,103 | 158 | 3.09 (2.25, 4.24) | 3.11 (2.26, 4.28) | ||

Female Female | 54,378 | 50 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Gestational age | 0.13 | 0.40 | ||||

Extremely preterm (23–27 weeks) Extremely preterm (23–27 weeks) | 324 | 2 | 3.69 (0.91, 14.97) | 2.25 (0.52, 9.82) | ||

Very preterm (28–31 weeks) Very preterm (28–31 weeks) | 863 | 3 | 2.16 (0.68, 6.81) | 1.45 (0.44, 4.82) | ||

Moderate to late preterm (32–36 weeks) Moderate to late preterm (32–36 weeks) | 8,291 | 21 | 1.58 (0.98, 2.53) | 1.38 (0.85, 2.23) | ||

Early term (37–38 weeks) Early term (37–38 weeks) | 20,208 | 41 | 1.27 (0.88, 1.82) | 1.22 (0.84, 1.77) | ||

Full term (39–40 weeks) Full term (39–40 weeks) | 60,431 | 97 | Referent | Referent | ||

Late term (41 weeks) Late term (41 weeks) | 17,584 | 41 | 1.45 (1.00, 2.08) | 1.47 (1.01, 2.12) | ||

Postterm (42–43 weeks) Postterm (42–43 weeks) | 1,780 | 3 | 1.03 (0.33, 3.26) | 0.84 (0.26, 2.69) | ||

| Size for gestational agea | 0.09 | 0.22 | ||||

Small for gestational age Small for gestational age | 1,802 | 7 | 2.02 (0.95, 4.31) | 1.64 (0.75, 3.56) | ||

Appropriate for gestational age Appropriate for gestational age | 77,392 | 151 | Referent | Referent | ||

Large for gestational age Large for gestational age | 30,287 | 50 | 0.85 (0.62, 1.17) | 0.93 (0.66, 1.30) | ||

| APGAR at 5 minutes | 0.15 | 0.43 | ||||

Less than Less than | 1,047 | 4 | 2.06 (0.77, 5.55) | 1.53 (0.54, 4.31) | ||

7 or greater 7 or greater | 108,433 | 204 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Maternal characteristics | ||||||

| Maternal age (years) | 0.85 | 0.10 | ||||

<20 <20 | 5,942 | 13 | 1.16 (0.66, 2.03) | 0.55 (0.28, 1.07) | ||

20–34 20–34 | 85,777 | 160 | Referent | Referent | ||

35+ 35+ | 17,762 | 35 | 1.06 (0.74, 1.53) | 1.26 (0.86, 1.86) | ||

| Married | <0.001 | 0.008 | ||||

No No | 17,517 | 57 | 1.94 (1.43, 2.64) | 1.67 (1.14, 2.44) | ||

Yes Yes | 91,964 | 151 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Maternal education level | 0.09 | 0.84 | ||||

Less than high school Less than high school | 6,877 | 17 | 1.48 (0.86, 2.54) | 1.13 (0.59, 2.17) | ||

High school graduate High school graduate | 21,559 | 53 | 1.54 (1.08, 2.20) | 1.17 (0.78, 1.76) | ||

1–3 years of college 1–3 years of college | 30,831 | 59 | 1.20 (0.86, 1.69) | 1.02 (0.72, 1.46) | ||

4 or more years of college 4 or more years of college | 50,214 | 80 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Tobacco use during pregnancy | <0.001 | 0.11 | ||||

No No | 100,198 | 176 | Referent | Referent | ||

Yes Yes | 9,283 | 32 | 1.96 (1.34, 2.86) | 1.41 (0.93, 2.14) | ||

| Weight gain during pregnancyb | 0.19 | 0.31 | ||||

Inappropriately low Inappropriately low | 4,917 | 15 | 1.65 (0.96, 2.82) | 1.50 (0.86, 2.63) | ||

Appropriate Appropriate | 88,470 | 163 | Referent | Referent | ||

Inappropriately high Inappropriately high | 16,093 | 30 | 1.03 (0.69, 1.54) | 0.94 (0.63, 1.42) | ||

| Parityc | 0.17 | 0.23 | ||||

0 0 | 43,258 | 98 | 1.39 (0.83, 2.33) | 1.58 (0.92, 2.74) | ||

1 1 | 36,843 | 61 | 1.01 (0.59, 1.74) | 1.22 (0.70, 2.13) | ||

2 2 | 18,943 | 32 | 1.04 (0.58, 1.88) | 1.21 (0.67, 2.19) | ||

3+ 3+ | 10,437 | 17 | Referent | Referent | ||

| Mode of delivery | 0.18 | 0.56 | ||||

Vaginal Vaginal | 92,142 | 168 | Referent | Referent | ||

Cesarean section Cesarean section | 17,339 | 40 | 1.27 (0.90, 1.79) | 1.11 (0.78, 1.59) | ||

| History of maternal psychiatric disorder | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||||

No No | 95,135 | 159 | Referent | Referent | ||

Yes Yes | 14,346 | 49 | 2.01 (1.46, 2.77) | 1.73 (1.24, 2.42) | ||

Abbreviations: ASD-R, research-identified autism spectrum disorder; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio

Table 6.

Perinatal characteristics of children included versus not included in the secondary analysis of the subset with maternal research authorization.

| Characteristic | Maternal Research Authorization | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N=6851) | No (N=1025) | ||

| Infant characteristics at birth | |||

| Male sex | 3500 (51.1%) | 508 (49.6%) | 0.36 |

| Gestational age | 0.20 | ||

Extremely preterm (23–27 weeks) Extremely preterm (23–27 weeks) | 23 (0.3%) | 5 (0.5%) | |

Very preterm (28–31 weeks) Very preterm (28–31 weeks) | 57 (0.8%) | 6 (0.6%) | |

Moderate or late preterm (32–36 weeks) Moderate or late preterm (32–36 weeks) | 509 (7.4%) | 77 (7.5%) | |

Early term (37–38 weeks) Early term (37–38 weeks) | 1250 (18.2%) | 216 (21.1%) | |

Full term (39–40 weeks) Full term (39–40 weeks) | 3778 (55.1%) | 540 (52.7%) | |

Late term (41 weeks) Late term (41 weeks) | 1117 (16.3%) | 159 (15.5%) | |

Postterm (42–43 weeks) Postterm (42–43 weeks) | 117 (1.7%) | 22 (2.1%) | |

| Birth weight (grams), median (IQR) | 3470 (3135, 3810) | 3415 (3060, 3745) | <0.001 |

| Size for gestational ageb | 0.023 | ||

Small for gestational age Small for gestational age | 113 (1.6%) | 24 (2.3%) | |

Appropriate for gestational age Appropriate for gestational age | 4860 (70.9%) | 756 (73.8%) | |

Large for gestational age Large for gestational age | 1878 (27.4%) | 245 (23.9%) | |

| APGAR score at 5 minutes | 0.85 | ||

Less than 7 Less than 7 | 63 (0.9%) | 10 (1.0%) | |

7 or greater 7 or greater | 6760 (98.7%) | 1012 (98.7%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 28 (0.4%) | 3 (0.3%) | |

| Maternal characteristics at delivery | |||

| Maternal age (years) | <0.001 | ||

Mean (SD) Mean (SD) | 29.1 (5.4) | 27.0 (6.0) | |

Less than 20 years Less than 20 years | 377 (5.5%) | 126 (12.3%) | |

20–34 years 20–34 years | 5394 (78.7%) | 782 (76.3%) | |

35 years and greater 35 years and greater | 1080 (15.8%) | 117 (11.4%) | |

| Maternal race | <0.001 | ||

White White | 6306 (92.0%) | 871 (85.0%) | |

Asian or Pacific Islander Asian or Pacific Islander | 315 (4.6%) | 87 (8.5%) | |

Black or African American Black or African American | 188 (2.7%) | 60 (5.9%) | |

American Indian or Alaskan Native American Indian or Alaskan Native | 11 (0.2%) | 2 (0.2%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 31 (0.5%) | 5 (0.5%) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity of mother | 0.20 | ||

No No | 6679 (97.5%) | 1007 (98.2%) | |

Yes Yes | 164 (2.4%) | 16 (1.6%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 8 (0.1%) | 2 (0.2%) | |

| Nativity status of mother | <0.001 | ||

US born US born | 6109 (89.2%) | 855 (83.4%) | |

US territory born US territory born | 13 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

Foreign born Foreign born | 725 (10.6%) | 169 (16.5%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 4 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Married status | 5730 (83.6%) | 717 (70.0%) | <0.001 |

| Maternal education level | <0.001 | ||

Less than high school Less than high school | 442 (6.5%) | 173 (16.9%) | |

High school graduate High school graduate | 1314 (19.2%) | 320 (31.2%) | |

1–3 years of college 1–3 years of college | 1837 (26.8%) | 268 (26.1%) | |

4 years or more of college 4 years or more of college | 3114 (45.5%) | 243 (23.7%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 144 (2.1%) | 21 (2.0%) | |

| Alcohol use during pregnancy | 0.002 | ||

No No | 6718 (98.1%) | 995 (97.1%) | |

Yes Yes | 68 (1.0%) | 23 (2.2%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 65 (0.9%) | 7 (0.7%) | |

| Tobacco use during pregnancy | <0.001 | ||

No No | 6215 (90.7%) | 878 (85.7%) | |

Yes Yes | 567 (8.3%) | 139 (13.6%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 69 (1.0%) | 8 (0.8%) | |

| Illicit drug use during pregnancy | 0.24 | ||

No No | 6747 (98.5%) | 1010 (98.5%) | |

Yes Yes | 21 (0.3%) | 6 (0.6%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 83 (1.2%) | 9 (0.9%) | |

| Singleton or multiple gestation | 0.15 | ||

Singleton Singleton | 6542 (95.5%) | 989 (96.5%) | |

Twins Twins | 266 (3.9%) | 34 (3.3%) | |

Higher order multiples Higher order multiples | 43 (0.6%) | 2 (0.2%) | |

| Weight gain during pregnancyc | 0.60 | ||

Inappropriately low Inappropriately low | 296 (4.3%) | 49 (4.8%) | |

Appropriate Appropriate | 5112 (74.6%) | 746 (72.8%) | |

Inappropriately high Inappropriately high | 921 (13.4%) | 143 (14.0%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 522 (7.6%) | 87 (8.5%) | |

| Gravidad | 0.21 | ||

0 0 | 2184 (31.9%) | 350 (34.1%) | |

1 1 | 2031 (29.6%) | 295 (28.8%) | |

2 2 | 1285 (18.8%) | 184 (18.0%) | |

3+ 3+ | 1298 (18.9%) | 190 (18.5%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 53 (0.8%) | 6 (0.6%) | |

| Parityd | 0.17 | ||

0 0 | 2716 (39.6%) | 436 (42.5%) | |

1 1 | 2284 (33.3%) | 325 (31.7%) | |

2 2 | 1164 (17.0%) | 152 (14.8%) | |

3+ 3+ | 651 (9.5%) | 108 (10.5%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 36 (0.5%) | 4 (0.4%) | |

| Adequacy of prenatal caree | <0.001 | ||

Inadequate Inadequate | 356 (5.2%) | 76 (7.4%) | |

Intermediate Intermediate | 970 (14.2%) | 159 (15.5%) | |

Adequate Adequate | 3332 (48.6%) | 442 (43.1%) | |

Adequate plus Adequate plus | 1364 (19.9%) | 200 (19.5%) | |

Incomplete information Incomplete information | 829 (12.1%) | 148 (14.4%) | |

| Mode of delivery | 0.17 | ||

Vaginal Vaginal | 5728 (83.6%) | 833 (81.3%) | |

Cesarean section Cesarean section | 1088 (15.9%) | 186 (18.1%) | |

Not recorded Not recorded | 35 (0.5%) | 6 (0.6%) | |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles); SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

Using an Olmsted County birth cohort of children born 1994–2000, we found multiple perinatal risk factors for ASD-R. Unadjusted analyses revealed male sex, maternal marital status, maternal education level, tobacco use during pregnancy, and inappropriately low weight gain during pregnancy to be associated with ASD-R. In the multivariable model for the full cohort, male sex, maternal age, maternal marital status, and tobacco use during pregnancy were significantly associated with ASD-R. In this cohort, gestational age was not significantly associated with ASD-R in the multivariable model. For the subset of the cohort with maternal psychiatric history available, male sex, maternal marital status, and presence of any maternal psychiatric disorder were associated with ASD-R in the multivariable model. The adjusted risk of ASD-R for preterm compared with term infants was 1.42 (95% CI 0.95, 2.11) for the full cohort and 1.42 (95% CI 0.90, 2.23) for the subset with maternal psychiatric history available.

The incidence of preterm birth was lower than the national average, which may reflect the demographic characteristics of Olmsted County. This may have contributed to power limitations to detect significance in the relationship between gestational age and ASD-R in the multivariable analysis. A similar pattern with the relationship between gestational age and ASD being attenuated in adjusted analyses was observed in a Swedish population-based case-control study. In the Swedish study, the unadjusted odds ratio (OR) for clinically diagnosed ASD was 2.05 (95% CI 1.26, 3.34) for children born <32 weeks’ gestation and 1.55 (95% CI 1.22, 1.96) for children born 32–36 weeks’ gestation, compared with children born 37–41 weeks’ gestation.33 After adjusting for maternal and perinatal characteristics, the adjusted OR for children born <32 weeks’ gestation was 1.48 (95% CI 0.77, 1.96) and for moderate to late preterm children born 32–36 weeks’ gestation was 1.33 (95% CI 0.98, 1.81); the adjusted ORs were further reduced after accounting for neonatal complications. The latter is similar to the adjusted HR 1.42 (95% CI 0.93, 2.15) for moderate to late preterm children in the current cohort. The increased risk of ASD previously reported among children born prematurely may reflect maternal and perinatal characteristics that are more common for children born prematurely and may influence early brain development.

Our multivariable analysis suggested that the risk of ASD-R may be higher for children born moderate to late preterm compared with those born full term. Gestational age in the moderate to late preterm and in the late term or postterm ranges may carry an increased risk for ASD-R as has been previously demonstrated for very preterm children.34,35 Xie et al evaluated singleton births in Stockholm County, Sweden, 1984–2007, for which there were 10,025 individuals with ASD; 24% also had intellectual disability.36 The risk of ASD with and without intellectual disability was higher in individuals born preterm compared with full term. At 27 weeks’ gestation, there were 52.4 cases of ASD/1000 (95% CI 42.3, 64.6) compared with 19.8 cases/1000 (95% CI 19.3, 20.3) at 40 weeks’ gestation and 23.1 cases/1000 (95% CI 21.3, 25.0) at 43 weeks’ gestation. In the Swedish cohort, the risk of ASD appeared to rise for infants born postterm. We did not observe a significant increase in risk for children born postterm, but the study only included 139 (1.8%) children at 42–43 weeks’ gestation.

Some perinatal factors, such as maternal age, associated with ASD-R in this multivariable analysis, have been associated with ASD in other samples. For example, Croen et al identified 4381 children with ASD born in California in 1989–1994; compared with women under 20 years, women over 35 years were three times as likely to have a child affected by ASD (relative risk (RR) 3.4, 95% CI 2.9–4.0).27 Maternal schizophrenia and affective disorders were found to be associated with ASD in Finnish cohort of 4713 children.37 Conversely, other perinatal factors, such as maternal education, that were not significantly associated with ASD-R in the current multivariable analysis, have been associated with ASD previously. In the aforementioned California cohort, women with a post-graduate education were two times as likely to have a child affected by ASD as women with less than a high school education after adjustment for maternal age as well as other confounding factors (RR 2.0, 95% CI 1.7, 2.3).27 The effect of some perinatal factors on ASD may change with time. It is plausible that maternal psychopathology may be associated with greater risk across childhood due to ongoing exposure whereas an association between ASD and gestational age may not change over time.

Strengths of this study include the use of a population-based birth cohort in the United States of America. Another strength is the rigorous identification process of ASD-R using both medical and school records by a multidisciplinary research team led by a child psychologist, two developmental pediatricians, a speech language pathologist, and an epidemiologist. Lastly, the availability of maternal psychiatric history for a substantial subset of the cohort strengthens the analysis.

This study has limitations. First, birth certificate data may underestimate the rate of pregnancy complications, such as drug and alcohol use.38 Second, with observational epidemiologic data, some measurement or misclassification error may be expected for gestational age at birth and other variables. Third, the low incidence of extremely preterm, very preterm, and postterm births and the number of ASD-R cases among those groups restricted our statistical power. Lastly, the birth cohort used the DSM-IV diagnoses for ASD as a starting point as it was the most current version available at the initiation of the study.19 Of note, the process to identify ASD-R based on signs and symptoms documented in medical and educational records may result in a later median age for meeting ASD-R criteria than a clinical diagnosis.18

Although lower gestational age at birth results in a vulnerable developing brain, gestational age was not a statistically significant perinatal risk factor for ASD-R in the multivariable analysis. It is critical to account for multiple perinatal characteristics when identifying risk factors for autism spectrum disorder. Pediatricians must be attuned to multiple perinatal risk factors for ASD-R, beyond gestational age, including those related to maternal psychiatric history, health during pregnancy, and sociodemographic characteristics of the household.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Robert C. Colligan for his insights and collegiality across his years of research in developmental disabilities at the Mayo Clinic. We also thank speech language pathologist Dr Ruth E. Stoeckel, study coordinators Ms Candice Klein and Mr Tom Bitz, and Independent School District No. 535 for their cooperation and collaboration.

This study was made possible using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (R01AG034676). This study was also funded by a research grant from the National Institutes of Health, Public Health Service (MH093522). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

| aHR | adjusted hazard ratio |

| ASD | autism spectrum disorder |

| ASD-R | research-identified autism spectrum disorder |

| CI | confidence interval |

| DSM-IV-TR | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| OR | odds ratio |

| RR | relative risk |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.01.022

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7186146

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.01.022

Article citations

Prenatal Diabetes and Obesity: Implications for Autism Spectrum Disorders in Offspring - A Comprehensive Review.

Med Sci Monit, 30:e945087, 24 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39180197 | PMCID: PMC11351376

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

The association between post-term births and autism spectrum disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis.

Eur J Med Res, 28(1):316, 02 Sep 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37660041 | PMCID: PMC10474756

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Effect of cesarean section on the risk of autism spectrum disorders/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in offspring: a meta-analysis.

Arch Gynecol Obstet, 309(2):439-455, 23 May 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37219611

Incidence and risk factors for autism spectrum disorder among infants born <29 weeks' gestation.

Paediatr Child Health, 27(6):346-352, 10 Jul 2022

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 36200098 | PMCID: PMC9528782

Nutritional Management of Moderate- and Late-Preterm Infants Commenced on Intravenous Fluids Pending Mother's Own Milk: Cohort Analysis From the DIAMOND Trial.

Front Pediatr, 10:817331, 31 Mar 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 35433556 | PMCID: PMC9008239

Go to all (10) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Birth weight and autism spectrum disorder: A population-based nested case-control study.

Autism Res, 13(4):655-665, 13 Jan 2020

Cited by: 13 articles | PMID: 31930777

Out-of-home care placements of children and adolescents born preterm: A register-based cohort study.

Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 34(1):38-47, 22 Dec 2019

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 31867756

Preterm birth and weight-for-gestational age for risks of autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability: A nationwide population-based cohort study.

J Formos Med Assoc, 122(6):493-504, 10 Nov 2022

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 36371297

Association Between Prenatal Exposure to Antipsychotics and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Preterm Birth, and Small for Gestational Age.

JAMA Intern Med, 181(10):1332-1340, 01 Oct 2021

Cited by: 29 articles | PMID: 34398171 | PMCID: PMC8369381

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

NIA NIH HHS (2)

Grant ID: R33 AG058738

Grant ID: R01 AG034676

NIMH NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: R01 MH093522

National Institute of Mental Health (1)

Grant ID: MH093522

National Institute on Aging

National Institutes of Health (1)

Grant ID: R01AG034676