Abstract

Importance

Parkinson disease (PD) is an increasingly common neurodegenerative disorder in many aging societies. Although comorbidities with mental disorders are common in PD, whether PD is associated with an increased risk of suicide is unclear.Objective

To use a large national representative PD cohort to compare the risk of suicide in patients with PD and control participants and identify potential risk factors.Design, setting, and participants

This nationwide population-based cohort study used linked data from Taiwan's National Health Insurance data set and Taiwan Death Registry between January 2002 and December 2016. Patients with incident PD diagnosed between January 2005 and December 2014 were followed up until December 2016. Four control participants from the general population were randomly selected by risk set sampling and were matched on age, sex, and residence to each affected individual. Data analysis occurred from June 2019 to October 2020.Exposures

Diagnosis of PD retrieved from the National Health Insurance data set.Main outcomes and measures

Suicide was recorded in the Taiwan Death Registry. Cox proportional models and hazard ratios (HRs) were used to estimate the association between PD and the risk of suicide over the follow-up period.Results

Over 11 years, 35 891 patients with PD were followed up (17 482 women [48.7%]; mean [SD] age, 72.5 [10.1] years) and matched to 143 557 control participants (69 928 women [48.7%]; mean [SD] age, 72.5 [10.1] years). A total of 151 patients with PD (cumulative incidence, 66.6 per 100 000 [95% confidence limits [CL], 78.1-91.7]) and 300 control participants (cumulative incidence, 32.3 per 100 000 [95% CL, 36.2-40.5]) died by suicide. The risk of suicide was higher (HR, 2.1 [95% CL, 1.7-2.5]) in patients with PD than control participants, after adjustment for markers of socioeconomic position, medical comorbidities, and dementia. After controlling for mental disorders, the association between PD and suicide risk remained (HR, 1.9 [95% CL, 1.6-2.3]). Compared with control participants who died by suicide, those who died by suicide in the PD group were slightly younger (mean [SD] age: patients with PD, 74.0 [10.4] years vs control participants, 76.0 [10.2] years; P = .05) and more likely to be urban dwelling (medium urbanization, 39 patients with PD [25.8%] vs 115 control participants [38.3%]; high urbanization, 84 patients with PD [55.6%] vs 136 control participants [45.3%]; P = .03), have mental disorders (depression, 15 of 151 patients with PD [9.9%] vs 15 of 300 control participants [5.0%]; other mental disorders, 12 patients with PD [8.0%] vs 11 control participants [3.7%]; P = .02), and adopt jumping as a method of suicide (21 patients with PD [13.9%] vs 16 control participants [5.3%]; P < .01).Conclusions and relevance

In this population-based cohort study, Parkinson disease, a common neurodegenerative disorder common in elderly persons, was independently associated with an increased risk of suicide. Integrating mental health care into primary care and PD specialty care, along with socioenvironmental interventions, may help decrease the risk of suicide in patients with PD.Free full text

Risk of Suicide Among Patients With Parkinson Disease

Key Points

Question

Is Parkinson disease (PD) associated with an increased risk of suicide, and which characteristics (sociodemographic, clinical, and comorbid) are associated with suicide risk in PD?

Findings

In this large population-based cohort of patients with PD (n =

= 35

35 891) and matched control participants (n

891) and matched control participants (n =

= 143

143 577) from Taiwan who were followed up over 11 years, the risk of suicide was significantly higher in patients with PD than control participants, after considering markers of socioeconomic position, medical comorbidities, dementia, and mental disorders, including depression. Suicide risk remained higher across the follow-up period.

577) from Taiwan who were followed up over 11 years, the risk of suicide was significantly higher in patients with PD than control participants, after considering markers of socioeconomic position, medical comorbidities, dementia, and mental disorders, including depression. Suicide risk remained higher across the follow-up period.

Meaning

Parkinson disease, a common neurodegenerative disorder in elderly persons, is associated with an increased risk of suicide that is not fully explained by higher rates of mental disorders in patients with PD.

Abstract

Importance

Parkinson disease (PD) is an increasingly common neurodegenerative disorder in many aging societies. Although comorbidities with mental disorders are common in PD, whether PD is associated with an increased risk of suicide is unclear.

Objective

To use a large national representative PD cohort to compare the risk of suicide in patients with PD and control participants and identify potential risk factors.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This nationwide population-based cohort study used linked data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance data set and Taiwan Death Registry between January 2002 and December 2016. Patients with incident PD diagnosed between January 2005 and December 2014 were followed up until December 2016. Four control participants from the general population were randomly selected by risk set sampling and were matched on age, sex, and residence to each affected individual. Data analysis occurred from June 2019 to October 2020.

Exposures

Diagnosis of PD retrieved from the National Health Insurance data set.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Suicide was recorded in the Taiwan Death Registry. Cox proportional models and hazard ratios (HRs) were used to estimate the association between PD and the risk of suicide over the follow-up period.

Results

Over 11 years, 35 891 patients with PD were followed up (17

891 patients with PD were followed up (17 482 women [48.7%]; mean [SD] age, 72.5 [10.1] years) and matched to 143

482 women [48.7%]; mean [SD] age, 72.5 [10.1] years) and matched to 143 557 control participants (69

557 control participants (69 928 women [48.7%]; mean [SD] age, 72.5 [10.1] years). A total of 151 patients with PD (cumulative incidence, 66.6 per 100

928 women [48.7%]; mean [SD] age, 72.5 [10.1] years). A total of 151 patients with PD (cumulative incidence, 66.6 per 100 000 [95% confidence limits [CL], 78.1-91.7]) and 300 control participants (cumulative incidence, 32.3 per 100

000 [95% confidence limits [CL], 78.1-91.7]) and 300 control participants (cumulative incidence, 32.3 per 100 000 [95% CL, 36.2-40.5]) died by suicide. The risk of suicide was higher (HR, 2.1 [95% CL, 1.7-2.5]) in patients with PD than control participants, after adjustment for markers of socioeconomic position, medical comorbidities, and dementia. After controlling for mental disorders, the association between PD and suicide risk remained (HR, 1.9 [95% CL, 1.6-2.3]). Compared with control participants who died by suicide, those who died by suicide in the PD group were slightly younger (mean [SD] age: patients with PD, 74.0 [10.4] years vs control participants, 76.0 [10.2] years; P

000 [95% CL, 36.2-40.5]) died by suicide. The risk of suicide was higher (HR, 2.1 [95% CL, 1.7-2.5]) in patients with PD than control participants, after adjustment for markers of socioeconomic position, medical comorbidities, and dementia. After controlling for mental disorders, the association between PD and suicide risk remained (HR, 1.9 [95% CL, 1.6-2.3]). Compared with control participants who died by suicide, those who died by suicide in the PD group were slightly younger (mean [SD] age: patients with PD, 74.0 [10.4] years vs control participants, 76.0 [10.2] years; P =

= .05) and more likely to be urban dwelling (medium urbanization, 39 patients with PD [25.8%] vs 115 control participants [38.3%]; high urbanization, 84 patients with PD [55.6%] vs 136 control participants [45.3%]; P

.05) and more likely to be urban dwelling (medium urbanization, 39 patients with PD [25.8%] vs 115 control participants [38.3%]; high urbanization, 84 patients with PD [55.6%] vs 136 control participants [45.3%]; P =

= .03), have mental disorders (depression, 15 of 151 patients with PD [9.9%] vs 15 of 300 control participants [5.0%]; other mental disorders, 12 patients with PD [8.0%] vs 11 control participants [3.7%]; P

.03), have mental disorders (depression, 15 of 151 patients with PD [9.9%] vs 15 of 300 control participants [5.0%]; other mental disorders, 12 patients with PD [8.0%] vs 11 control participants [3.7%]; P =

= .02), and adopt jumping as a method of suicide (21 patients with PD [13.9%] vs 16 control participants [5.3%]; P

.02), and adopt jumping as a method of suicide (21 patients with PD [13.9%] vs 16 control participants [5.3%]; P <

< .01).

.01).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this population-based cohort study, Parkinson disease, a common neurodegenerative disorder common in elderly persons, was independently associated with an increased risk of suicide. Integrating mental health care into primary care and PD specialty care, along with socioenvironmental interventions, may help decrease the risk of suicide in patients with PD.

Introduction

Older adults are at a greater suicide risk than other age groups globally.1 Paralleling trends in rapid population aging, a rise in the number of suicides is expected over the next decades. Efforts targeting older age groups to reduce their suicide burden are crucial.

Parkinson disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder; the prevalence increases with age.2,3 Parkinson disease is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder after Alzheimer disease.4 In addition to motor symptoms, psychiatric symptoms, such as depression and anxiety, are common over the course of PD.5 Approximately 40% to 50% of patients with PD are affected by depression,5,6 and 30% to 40% are affected by anxiety disorders.7,8 In addition to the long-established associations between mental disorders and suicide,9 the physical limitations caused by PD and the well-known increased risk of suicide in older persons call for attention to the likelihood of suicide in patients with PD.

Research into the association between PD and suicide has not provided a consistent picture.10 Several studies have found high suicide rates in patients with PD,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 whereas others have not,18,19,20 and 1 study21 has shown a considerably lower risk than in the general population. Given that suicide is a rare occurrence, studies with large and representative population-based PD samples are needed to reach a reliable estimate of suicide rates. Parkinson disease causes progressive physical disability, which is an important suicide risk factor in younger and middle-aged populations; whether PD is associated with elevated suicide risk is understudied.22

Over and above the estimation of suicide risk in PD using a large national representative PD cohort within Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (NHI) system, we assessed a plethora of factors possibly associated with suicide risk in PD. We explored (1) differences in characteristics (sociodemographic attributes, medical and mental disorders, and methods of suicide) of patients with PD and control participants from the general population who died by suicide and (2) factors associated with suicide risk (disease duration, PD severity, medical and mental comorbidities) in patients with PD.

Methods

Data

This study is a population-based cohort nested within Taiwan’s NHI data set provided by the Health and Welfare Data Science Center between 2002 and 2016. A universal NHI program has been implemented in Taiwan since March 1995; currently, more than 99% of the Taiwanese population is enrolled in the NHI program.23 Many studies evaluated the validity of diagnostic codes in the NHI data set, and validation studies showed modest to high sensitivity, depending on the disease.24 This study was exempted from informed consent because the analysis was of secondary data, and the study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Taipei City Hospital.

Study Participants

Patients With PD

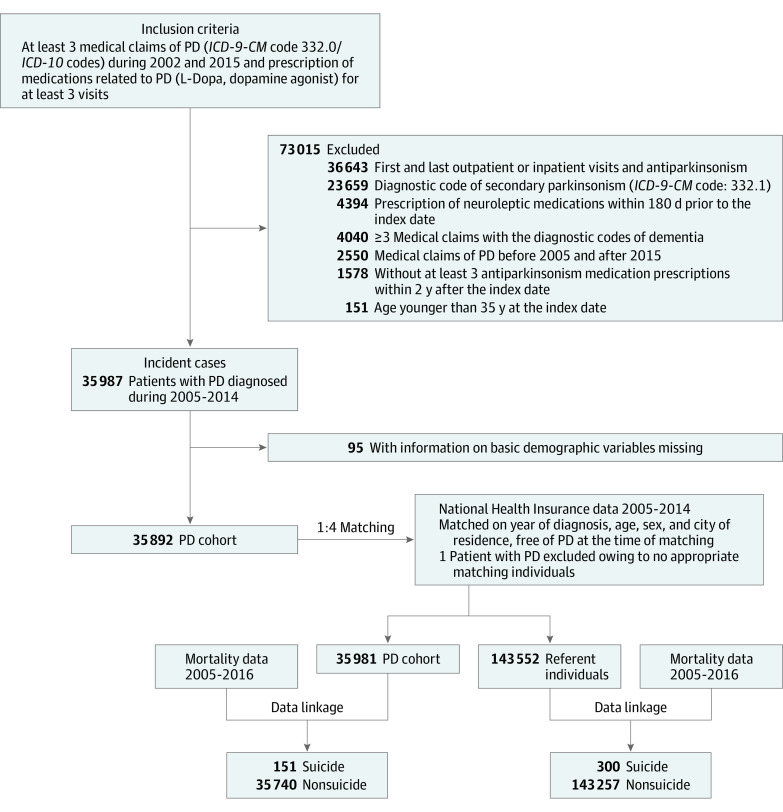

The criteria used to identify incident patients with PD in the current study were validated previously.25 The Figure presents a flowchart for the selection of patients with PD. Detailed sample selection criteria are provided in the eMethods in the Supplement. We retained for our analyses patients with incident PD diagnosed between January 2005 and December 2014. For those with PD, the index date is the date of first inpatient or outpatient record for PD after January 2005.

ICD-9-CM indicates International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision.

Control Participants

We used risk set sampling to match 4 control participants from the general population to each individual with PD on age, sex, year of PD diagnosis, and county of residence at the index date of the PD case. Control participants were alive and free of PD at the index date. If control participants developed PD over the study period, they were censored at the diagnosis date and included as patients with PD and followed up after the diagnosis date. Within each matched set, control participants were assigned to have the same index date as the matched individual with PD.

Outcome Variable: Suicide

The outcome variable was suicide, ascertained through linking the unique National Identification Numbers of study participants to the Taiwan Death Registry during 2005 and 2016. Codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) used to identify suicides, and methods of suicide are listed in eTable 1 in the Supplement.26

Covariates

We evaluated whether dementia, depression, and mental disorders other than depression contributed to suicide risk. Dementia was defined by a list of ICD codes previously determined.27 Mental disorders were defined as receiving a primary diagnosis of mental disorder in at least 3 outpatient visits or 1 inpatient care incident, within 1 year prior to the incidence of PD or after the onset of PD. In the current analysis, we defined mental disorders as mental and behavioral disorders other than organic mental disorders (eg, PD, Alzheimer dementia). Dementia, depression, and other mental disorders over the follow-up were defined as time-dependent variables. The ICD codes used to ascertain the study variables are listed in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Insurance premium and urbanization at baseline were selected as proxy measures of socioeconomic position (SEP). Insurance premium was based on enrollees’ monthly insurance payment: $0 to $36, more than $36 to $650, or more than $650. Urbanization index was categorized into 3 groups: high (metropolitan cities), medium (small cities and suburban areas), and low (rural areas).28,29 The Charlson Comorbidity Index at baseline, a widely used indicator of medical comorbidities, was used to represent physical conditions.21

Disease duration was defined as a time-dependent variable and was categorized as less than 1 year, 1 to 3 years, and 4 or more years. Severity of PD over the follow-up period was modeled as a time-dependent variable based on the annual cumulative levodopa-equivalent dose for levodopa, dopamine agonists, and other PD medications (low, <33rd percentile; moderate, 33rd–<66th percentile; high, ≥66th percentile) after the index date.30,31

Statistical Analysis

Patients with PD and control participants were followed up until the end of 2016, the last date of presence in the NHI system, or death from any cause, whichever occurred first; in addition, patients with PD who received deep brain stimulation were censored as of the date of surgery. Reasons for censoring are described in eTable 2 in the Supplement. We used the Cox proportional risk model to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence limits (CLs) with time since index date as the time scale. The proportional hazard assumption was verified using plots of log (−log[survival function]) as a function of time and by including in the models interactions term between covariates and log(time). A series of Cox models by including covariates were fitted sequentially. A Fine and Gray competing risk model32 was fitted to compare the cumulative incidence of suicide in association with PD after considering risk of death from other causes. We report the cumulative incidence of suicide by PD status estimated from the cumulative incidence function while taking into account competing causes of death. We also compared differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between suicide and nonsuicide outcomes in patients with PD and control participants. In analyses restricted to patients with PD, we used Cox models to assess whether clinical characteristics, including disease duration, severity, and medical or mental comorbidities contributed to the risk of suicide.

Data analyses were completed from June 2019 to October 2020 with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). The significant threshold was set at 2-tailed P ≤

≤ .05 level.

.05 level.

Results

A total of 35 891 patients with PD (18

891 patients with PD (18 409 men and 17

409 men and 17 482 women; mean [SD] age, 72.5 [10.1] years) were included. They were matched to 143

482 women; mean [SD] age, 72.5 [10.1] years) were included. They were matched to 143 557 control participants (73

557 control participants (73 629 men and 69

629 men and 69 928 women; mean [SD] age, 72.5 [10.1] years) from the general population. The median follow-up was 4.95 years (mean [SD], 5.38 [2.77] years) for patients with PD and 5.40 years (mean [SD], 5.78 [2.86] years) for control participants.

928 women; mean [SD] age, 72.5 [10.1] years) from the general population. The median follow-up was 4.95 years (mean [SD], 5.38 [2.77] years) for patients with PD and 5.40 years (mean [SD], 5.78 [2.86] years) for control participants.

Over the follow-up, 151 patients with PD (93 men and 58 women) and 300 control participants (197 men and 103 women) died by suicide. The cumulative incidence of suicide was higher in patients with PD than control participants throughout the follow-up. In individuals with PD, the 11-year cumulative incidence of suicide was 66.6 per 100 000 (95% CL, 78.1-91.7 per 100

000 (95% CL, 78.1-91.7 per 100 000); in control participants, cumulative incidence was 32.3 per 100

000); in control participants, cumulative incidence was 32.3 per 100 000 (95% CL, 36.2-40.5 per 100

000 (95% CL, 36.2-40.5 per 100 000).

000).

At baseline (Table 1), patients with PD were more likely to have physical and mental comorbidities (1 medical comorbidity, 9068 of 35 891 patients with PD [25.3%] vs 25

891 patients with PD [25.3%] vs 25 658 of 143

658 of 143 557 control participants [17.9%]; 2 or more medical comorbidities, 6858 patients with PD [19.1%] vs 20

557 control participants [17.9%]; 2 or more medical comorbidities, 6858 patients with PD [19.1%] vs 20 997 control participants [14.6%]). The prevalence of depression (1269 patients with PD [3.5%] vs 1631 control participants [1.1%]) and mental disorders other than depression (1378 [3.8%] vs 2087 [1.5%]) was higher in patients with PD than control participants.

997 control participants [14.6%]). The prevalence of depression (1269 patients with PD [3.5%] vs 1631 control participants [1.1%]) and mental disorders other than depression (1378 [3.8%] vs 2087 [1.5%]) was higher in patients with PD than control participants.

Table 1.

| Characteristics | Patients with Parkinson disease (n = = 35 35 891) 891) | Control participants (n = = 143 143 557) 557) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | Person-years | Suicide (n = = 151) 151) | Suicide rate/per 100 000 person-years 000 person-years | No. (%) | Person-years | Suicide (n = = 300) 300) | Suicide rate/per 100 000 person-years 000 person-years | |

| Matching variables | ||||||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 72.5 (10.1) | NA | NA | NA | 72.5 (10.1) | NA | NA | NA |

| ≥75 | 17 052 (47.5) 052 (47.5) | 82 997.80 997.80 | 66 | 79.5 | 68 201 (47.5) 201 (47.5) | 360 597.68 597.68 | 144 | 39.9 |

| 65-74 | 11 506 (32.1) 506 (32.1) | 66 050.53 050.53 | 49 | 74.2 | 46 024 (32.1) 024 (32.1) | 284 051.92 051.92 | 100 | 35.2 |

| <65 | 7333 (20.4) | 44 197.71 197.71 | 36 | 81.5 | 29 332 (20.4) 332 (20.4) | 184 632.53 632.53 | 56 | 30.3 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 18 409 (51.3) 409 (51.3) | 95 121.41 121.41 | 93 | 97.8 | 73 629 (51.3) 629 (51.3) | 412 997.21 997.21 | 197 | 47.7 |

| Female | 17 482 (48.7) 482 (48.7) | 98 124.64 124.64 | 58 | 59.1 | 69 928 (48.7) 928 (48.7) | 416 284.92 284.92 | 103 | 24.7 |

| Insurance premium ($/mo) | ||||||||

| 0-36 | 5509 (15.4) | 36 245.27 245.27 | 31 | 85.5 | 20 263 (14.1) 263 (14.1) | 148 630.77 630.77 | 71 | 47.8 |

| >36-650 | 9363 (26.1) | 48 686.88 686.88 | 40 | 82.2 | 37 055 (25.8) 055 (25.8) | 203 546.35 546.35 | 85 | 41.8 |

| >650 | 21 019 (58.6) 019 (58.6) | 108 313.89 313.89 | 80 | 73.9 | 86 239 (60.1) 239 (60.1) | 477 105.00 105.00 | 144 | 30.2 |

| Level of urbanization | ||||||||

| Low | 5436 (15.2) | 28 392.43 392.43 | 28 | 98.6 | 21 703 (15.1) 703 (15.1) | 123 757.70 757.70 | 49 | 39.6 |

| Medium | 11 099 (30.9) 099 (30.9) | 59 405.83 405.83 | 39 | 65.7 | 45 831 (31.9) 831 (31.9) | 262 696.28 696.28 | 115 | 43.8 |

| High | 19 356 (53.9) 356 (53.9) | 105 447.79 447.79 | 84 | 79.7 | 76 023 (53.0) 023 (53.0) | 442 828.15 828.15 | 136 | 30.7 |

| Medical comorbidities per the Charlson Comorbidity Indexa | ||||||||

| 0 | 19 965 (55.6) 965 (55.6) | 111 430.95 430.95 | 83 | 74.5 | 96 902 (67.5) 902 (67.5) | 588 755.94 755.94 | 187 | 31.8 |

| 1 | 9068 (25.3) | 49 317.59 317.59 | 35 | 71.0 | 25 658 (17.9) 658 (17.9) | 142 799.09 799.09 | 57 | 39.9 |

| ≥2 | 6858 (19.1) | 32 497.51 497.51 | 33 | 101.5 | 20 997 (14.6) 997 (14.6) | 97 727.10 727.10 | 56 | 57.3 |

| Mental disorders | ||||||||

| None | 33 244 (92.6) 244 (92.6) | 179 176.94 176.94 | 124 | 69.2 | 139 839 (97.4) 839 (97.4) | 808 973.89 973.89 | 274 | 33.9 |

| Depression | 1269 (3.5) | 6921.14 | 15 | 216.7 | 1631 (1.1) | 9377.32 | 15 | 160.0 |

| Mental disorders other than depression | 1378 (3.8) | 7147.97 | 12 | 167.9 | 2087 (1.5) | 10 930.92 930.92 | 11 | 100.6 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

The risk of suicide in patients with PD was about 2 times higher than in the control group after adjustment for matching variables, SEP, medical comorbidities, dementia, and mental disorders (hazard ratio [HR], 1.9 [95% CL, 1.6-2.3]) (Table 2). The results for sequential modeling are provided in eTable 3 in the Supplement. The HR of suicide in the null model (ie, the model adjusted for matching variables only) was 2.2 (95% CL, 1.8-2.7) (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Adjustment for mental disorders (model 5) had the strongest result, leading to an attenuation of approximately 14% (HR, 1.9 [95% CL, 1.5-2.3]). An additional analysis that categorized mental disorders into schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and other mental disorders yielded similar conclusions (eTable 4 in the Supplement). In stratified analyses, the association between PD and suicide was present in all strata defined by sex, age, insurance premium, urbanization, and mental disorders; the number of patients with dementia was too small to obtain an estimate in that group (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Table 2.

| Characteristic | Regression coefficient (SE) | Hazard ratio (95% confidence limit) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide in Parkinson disease | 0.6 (0.1) | 1.9 (1.6 to 2.3) | <.001 |

| Sociodemographic covariates | |||

| Age at index date, y | 0.1 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.4 to 2.7) | .84 |

| Age2, y | −0.001 (0.003) | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.0) | .80 |

| Sex | |||

| Women | 0 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Men | 0.6 (0.1) | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.2) | <.001 |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 2005 | 0 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 2006 | −0.1 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) | .61 |

| 2007 | −0.2 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.2) | .41 |

| 2008 | −0.3 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.1) | .14 |

| 2009 | 0.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) | .86 |

| 2010 | −0.1 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) | .54 |

| 2011 | −0.4 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.0) | .06 |

| 2012 | −0.6 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.9) | .01 |

| 2013 | −0.3 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.2) | .21 |

| 2014 | −0.3 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.3) | .30 |

| Insurance premium, $ | |||

| 0-36 | 0 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| >36-650 | 0.0 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.3) | .81 |

| >650 | −0.2 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.0) | .10 |

| Level of urbanization | |||

| High | 0 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Medium | 0.2 (0.1) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5) | .04 |

| Low | 0.3 (0.1) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8) | .02 |

| Medical comorbidities per Charlson Comorbidity Index | |||

| 0 | 0 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 1 | 0.1 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.4) | .58 |

| ≥2 | 0.4 (0.1) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) | <.001 |

| Dementiab | −0.2 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) | .31 |

| Mental disorders | |||

| No | 0 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Depression | 1.5 (0.2) | 4.3 (2.9 to 6.3) | <.001 |

| Mental disorder other than depression | 1.5 (0.2) | 4.5 (3.2 to 6.3) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Differences between participants who died by suicide and those who did not are presented in eTable 6 in the Supplement by PD status. Patients with PD who died by suicide were less likely to have dementia (11 of 151 who died by suicide [7.3%] vs 5840 of 35 740 who did not die by suicide [16.3%]; P

740 who did not die by suicide [16.3%]; P =

= .003), more likely to be men (93 of 151 [61.6%] vs 18

.003), more likely to be men (93 of 151 [61.6%] vs 18 316 of 35

316 of 35 740 [51.3%]; P

740 [51.3%]; P =

= .01), and more likely to have mental disorders (depression, 15 [9.9%] vs 1254 [3.5%]; other mental disorders, 12 [8.0%] vs 1366 [3.8%]; P

.01), and more likely to have mental disorders (depression, 15 [9.9%] vs 1254 [3.5%]; other mental disorders, 12 [8.0%] vs 1366 [3.8%]; P <

< .001). Similar to the observations from the general population, control participants who died by suicide were more likely to be men (197 of 300 who died by suicide [65.7%] vs 73

.001). Similar to the observations from the general population, control participants who died by suicide were more likely to be men (197 of 300 who died by suicide [65.7%] vs 73 432 of 143

432 of 143 257 who did not die by suicide [51.3%]), be in lower SEPs (monthly insurance premiums: $0-36, 71 [23.7%] vs 20

257 who did not die by suicide [51.3%]), be in lower SEPs (monthly insurance premiums: $0-36, 71 [23.7%] vs 20 192 [14.1%]; >$36-$650, 85 [28.3%] vs 36

192 [14.1%]; >$36-$650, 85 [28.3%] vs 36 970 [25.8%]; >$650, 144 [48.0%] vs 86

970 [25.8%]; >$650, 144 [48.0%] vs 86 095 [60.1%]; P

095 [60.1%]; P <

< .001; urbanization: low, 49 [16.3%] vs 21

.001; urbanization: low, 49 [16.3%] vs 21 654 [15.1%]; medium, 11 [38.3%] vs 45

654 [15.1%]; medium, 11 [38.3%] vs 45 716 [31.9%]; high, 13 [45.3%] vs 75

716 [31.9%]; high, 13 [45.3%] vs 75 887 [53.0%]; P

887 [53.0%]; P =

= .02), and have mental disorders (depression, 15 [5.0%] vs 1616 [1.1%]; other mental disorders, 11 [3.7%] vs 2076 [1.5%]; P

.02), and have mental disorders (depression, 15 [5.0%] vs 1616 [1.1%]; other mental disorders, 11 [3.7%] vs 2076 [1.5%]; P <

< .001).33

.001).33

Table 3 shows analyses restricted to patients with PD to assess clinical characteristics associated with the risk of suicide in PD. Disease duration was not associated with the risk of suicide. Compared with those who did not receive levodopa, elevated risks of suicide were found in those who were prescribed low doses (HR, 1.6 [95% CL, 1.0-2.6]; P =

= .05) or moderate doses (HR, 1.9 [95% CL, 1.2-3.1]; P

.05) or moderate doses (HR, 1.9 [95% CL, 1.2-3.1]; P =

= .01) but not high doses; there was no association with dopamine agonists and other drugs. Depression was associated with a 3-fold increased risk of suicide compared with patients with PD without depression (HR, 3.3 [95% CL, 1.9-5.8]; P

.01) but not high doses; there was no association with dopamine agonists and other drugs. Depression was associated with a 3-fold increased risk of suicide compared with patients with PD without depression (HR, 3.3 [95% CL, 1.9-5.8]; P <

< .001). Dementia was no longer associated with suicide risk in patients with PD in the models adjusting for covariates.

.001). Dementia was no longer associated with suicide risk in patients with PD in the models adjusting for covariates.

Table 3.

| Sociodemographic covariates | Regression coefficient (SE) | Hazard ratio (95% confidence limit) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at index date, y | 0.1 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.2 to 5.0) | .91 |

| Age2, y | −0.001 (0.006) | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.0) | .83 |

| Sex | |||

| Women | 0 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Men | 0.5 (0.2) | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.4) | <.001 |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 2005 | 0 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 2006 | 0.5 (0.3) | 1.7 (0.9 to 3.4) | .12 |

| 2007 | −0.3 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.3 to 1.7) | .50 |

| 2008 | 0.4 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.7 to 3.2) | .26 |

| 2009 | 0.6 (0.4) | 1.8 (0.9 to 3.6) | .12 |

| 2010 | 0.3 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.6 to 2.9) | .42 |

| 2011 | 0.3 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.6 to 2.9) | .45 |

| 2012 | −0.1 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.1) | .82 |

| 2013 | 0.2 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.5 to 2.8) | .61 |

| 2014 | 0.1 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.4 to 2.8) | .90 |

| Insurance premium, $ | |||

| 0-36 | 0 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| >36-650 | 0.0 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.7) | .87 |

| >650 | −0.1 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.4) | .92 |

| Level of urbanization | |||

| High | 0 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Medium | −0.2 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.2) | .41 |

| Low | 0.3 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.9 to 2.0) | .21 |

| Disease duration, y | |||

| <1 | 0 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 1-3 | 0.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.6) | >.99 |

| ≥4 | 0.1 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.8) | .79 |

| Medication dosage | |||

| Levodopa | |||

| No | 0 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Low | 0.5 (0.2) | 1.6 (1.0 to 2.6) | .05 |

| Moderate | 0.6 (0.3) | 1.9 (1.2 to 3.1) | .01 |

| High | 0.3 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.4) | .22 |

| Dopamine agonists | |||

| No | 0 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Low | 0.2 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.6 to 2.2) | .63 |

| Moderate | 0.2 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.6 to 2.4) | .55 |

| High | −0.3 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.3 to 1.8) | .54 |

| Other Parkinson disease medications | |||

| No | 0 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Yes | 0.0 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.6) | .85 |

| Medical comorbidities (Charlson Comorbidity Index) | |||

| 0 | 0 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 1 | −0.1 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.4) | .75 |

| ≥2 | 0.2 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.8 to 1.9) | .26 |

| Dementiab | −0.4 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.4) | .27 |

| Mental disorders | |||

| No | 0 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Depression | 1.2 (0.3) | 3.3 (1.9 to 5.8) | <.001 |

| Mental disorder other than depression | 0.9 (0.3) | 2.5 (1.4 to 4.6) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

The characteristics of patients with PD and control participants who died by suicide were compared (eTable 7 in the Supplement). Patients with PD who died by suicide were younger (mean [SD] age: patients with PD, 74.0 [10.4] years vs control participants, 76.0 [10.2] years; P =

= .05), had higher rates of mental disorders (depression, 15 of 151 patients with PD [9.9%] vs 15 of 300 control participants [5.0%]; other mental disorders, 12 patients with PD [8.0%] vs 11 control participants [3.7%]; P

.05), had higher rates of mental disorders (depression, 15 of 151 patients with PD [9.9%] vs 15 of 300 control participants [5.0%]; other mental disorders, 12 patients with PD [8.0%] vs 11 control participants [3.7%]; P =

= .02), were more likely to reside in urban areas (medium urbanization, 39 [25.8%] vs 115 [38.3%]; high urbanization, 84 [55.6%] vs 136 [45.3%]; P

.02), were more likely to reside in urban areas (medium urbanization, 39 [25.8%] vs 115 [38.3%]; high urbanization, 84 [55.6%] vs 136 [45.3%]; P =

= .03), and were more likely to adopt jumping as a method of suicide (21 [13.9%] vs 16 [5.3%]; P

.03), and were more likely to adopt jumping as a method of suicide (21 [13.9%] vs 16 [5.3%]; P <

< .01).

.01).

Discussion

Main Findings

In a large national representative population-based cohort, suicide risk was about 2 times higher in patients with PD than the general population, after adjustment for markers of SEP, medical comorbidities, dementia, and mental disorders. The suicide risk elevation in PD was only partially explained by comorbidity with depression and other mental disorders. Parkinson disease in itself markedly escalated the risk of suicide.

Among those who died by suicide, those with PD were somewhat different from the comparison group; they were younger, were more likely to have a diagnosis of mental disorder, resided more often in urban areas, and were more likely to have died by jumping. In patients with PD, risk factors of suicide included low to moderate disease severity and mental disorders, including depression. Disease duration and comorbidity with dementia and medical diseases did not affect suicide risk in patients with PD.

Comparison With Previous Literature and Explanations of Findings

Although the existing literature is often inconsistent, there is evidence in favor of an increased risk of suicide in PD.11,14,15,16 Our estimate of a 2-fold increased risk is close to reports from Denmark in 2015 (men: HR, 1.92 [95% CI, 1.26-2.92]; women: HR, 2.26 [95% CI, 1.25-4.08]) and 2020 (HR, 1.7 [95% CI, 1.5-1.9]),14,34 the UK (adjusted odds ratio, 2.41 [95% CI, 1.15-5.07]),13 and a general hospital sample from Seoul, South Korea (HR, 1.99 [95% CI, 1.33-2.85])12; it was lower than the association estimate from a nationwide population-based cohort from South Korea (HR, 4.73), but this HR had a very wide confidence interval (95% CI, 0.99-11.20).11

Several mechanisms may explain the link between PD and suicide. First, being diagnosed with PD may constitute an acute life event, which is a prominent risk factor of suicide.35 Second, depression, the most prominent risk factor of suicide, is a common nonmotor symptom in PD.5,6,35 We confirmed a prominent direct effect of PD on the risk of suicide, but depression and other mental disorders also played a role. Third, functional decline, a common feature of PD, has been suggested to be an important contributing factor for suicide in elderly persons.36 Functional impairments may lead to disability, dependence, and feelings of perceived burdensomeness and disconnectedness from social networks; these are all risk factors of suicide in late life.36 Finally, suicide risk in PD may be emerge with treatment. Although inconsistent, some studies reported an association between dopaminergic agents and suicide in PD,12 whereas other studies did not support this association.37 We did not find evidence in favor of a strong association between use of dopamine agonists and suicide in patients with PD. Furthermore, some reports suggest an increased risk of suicide and suicide attempt in patients with PD and subthalamic nucleus stimulation,38,39 but whether the link is causal or confounded by disease severity remains unclear. To eliminate the influence of subthalamic nucleus stimulation, patients with PD who underwent deep brain stimulation were treated as censored in observations after surgery.

We did not locate any previous study that had prospectively followed patients with PD over a long period to examine a plethora of risk factors associated with suicide. In this PD cohort, we found that the suicide risk elevation was constant and persistent over time. We did not identify any particular high-risk or low-risk period. Unlike suicide patterns generally observed in Alzheimer disease, namely an initial high risk that decreases subsequently and is lower than the general population at advanced stages,34,40,41 we observed a persistent elevated suicide risk in PD, as a Danish study had.34 Regarding PD severity, we did not have direct information and used the dosage of antiparkinsonian drugs as a surrogate; patients who did not require levodopa probably had fewer symptoms and had significantly lower suicide risk compared with those who had low to moderate symptoms. Those who were prescribed with higher dosages of levodopa may have more severe cognitive and motor function decline and thus were less capable of conducting suicidal acts; alternatively, they may have adapted to their disabilities.

Late-life suicide rates are particularly high in many East Asian countries; the suicide rate ratio of elderly individuals (≥65 years old) to the general population ranges between 3 and 4 to 1.33,42 This finding is in contrast with ratios slightly higher than 1 reported in Western countries.33,42 In Taiwan, suicide rates of those of older ages (≥65 years old) were between 31.2 and 39.3 per 100 000 population during the study period (2002-2016),43 similar to our estimated suicide incidence rate in control participants (32.3 per 100

000 population during the study period (2002-2016),43 similar to our estimated suicide incidence rate in control participants (32.3 per 100 000 population). The corresponding age-standardized general population suicide rates were in the range of 11.8 to 16.8 (ie, less than half of the rates in elderly individuals). These figures suggest that high suicide rates in elderly adults is an important public health concern in Taiwan.

000 population). The corresponding age-standardized general population suicide rates were in the range of 11.8 to 16.8 (ie, less than half of the rates in elderly individuals). These figures suggest that high suicide rates in elderly adults is an important public health concern in Taiwan.

In Taiwan, similar to many East Asian countries, veneration of older age groups is a fundamental cultural value.44 However, rapid industrialization and weakening of traditional family networks may have resulted in paradoxically high suicide rates in elderly individuals.33,45 Elders’ expectations of living with their children are crushed as an increasing number of younger age groups live under nuclear family setups. Their progressive disability combined with disappointment toward their children may foster suicidality in patients with PD. Prevention efforts directed toward increasing family and community connectedness is preeminent.

The debilitating nature and high rates of co-occurring mental disorders in PD may explain the findings that those with PD who died by suicide were younger and more likely to have received a diagnosis of mental disorder. We found that patients with PD who died by suicide were more likely to reside in urban areas and more often adopted jumping as a method of suicide. This is consistent with previous research showing that jumping from a home is a common way of death in older adults with frailty who are dwelling in high-rise buildings in urban areas.46,47,48,49 In fact, for patients with PD and a high risk of suicide (eg, comorbidity with mental disorders), a jump from their own residential buildings can be easy and readily accessible. Hence, home safety assessments should be an integrated part of suicide prevention measures for patients with PD at high risk.

Strengths

The strengths of the current study lie in its large and representative sample with a cohort design. In addition, it had a long follow-up.

Limitations

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the covariates that we assessed were limited by data availability from the data set. Information such as lifestyle behaviors, ethnicity, detailed disease history, and disease staging was not available. Second, we relied on physician-recorded diagnosis in medical claim data; hence, potential disease misclassification may be present. Nonetheless, the methods used to ascertain patients with PD were validated previously.25 Third, the prevalence of depression (1.1%) in the general population comparison group was approximately the same as the estimate from a nationwide epidemiological survey (1.2%).50 The low rate of depression found in our study is likely to be attributable to cultural factors or mental illness stigma that lead to underdiagnosis of depression in many Chinese societies,51 rather than disease ascertainment in the present study. Lastly, although Taiwan’s death records data are considered fairly reliable,52 underreporting and misclassification are more common for suicides than other causes of death.1,26 Based on previous research,1,26 undetermined intent was included in the analyses of suicides to reduce potential underreporting.

Conclusions

Taking advantage of a large and representative PD cohort with 11 years of follow-up, we found that suicide was about 2 times more frequent in patients with PD than in the general population. Although comorbidity with mental disorders contributed partially to their suicide risk elevations, PD in itself was a potent determinant of suicide. Over and above identifying and treating mental disorders in PD, integrating mental health care into primary care, geriatric health care, and PD specialty care might be helpful. Furthermore, socioenvironmental interventions, such as enhancing family and community connectedness and home safety assessment to prevent suicide by jumping, are all potential intervention measures.

High suicide rates among elderly individuals represent a growing concern in many developed countries worldwide. Future studies should explore factors that have not been examined in the current study to better understand the high suicide risk in PD.

Notes

Supplement.

eMethods. Supplementary methods

eTable 1. ICD-codes for study variables

eTable 2. Reasons for censoring in Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients and referent subjects

eTable 3. Hazard ratios of suicide in Parkinson's disease (PD) patients compared to referent subjects from the general population

eTable 4. Hazard ratios of suicide in Parkinson's disease patients compared to referent subjects before and after adjusting for mental disorders

eTable 5. Hazard ratios of suicide in Parkinson's disease patients compared to referent subjects from the general population stratified by their characteristics

eTable 6. Comparisons between socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of suicide and non-suicide in Parkinson’s disease (PD) patient and referent subjects

eTable 7. Characteristics of Parkinson’s disease patients and referent subjects who died by suicide

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4001

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7745139

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Article citations

Loneliness and Risk of Parkinson Disease.

JAMA Neurol, 80(11):1138-1144, 01 Nov 2023

Cited by: 4 articles | PMID: 37782489 | PMCID: PMC10546293

Risk of Suicidal Ideation and Behavior in Individuals With Parkinson Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

JAMA Neurol, 81(1):10-18, 01 Jan 2024

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37955917 | PMCID: PMC10644251

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Differential impact of resilience on demoralization and depression in Parkinson disease.

Front Psychiatry, 14:1207019, 24 Jul 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37559912 | PMCID: PMC10408307

Editorial: Temporal lobe dysfunction in neuropsychiatric disorder.

Front Psychiatry, 13:1077398, 07 Nov 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 36419972 | PMCID: PMC9677554

Prevalence and Risk Factors of Depression between Patients with Parkinson's Disease and Their Caregivers: A One-Year Prospective Study.

Healthcare (Basel), 10(7):1305, 14 Jul 2022

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 35885832 | PMCID: PMC9318994

Go to all (10) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Association of Glycolysis-Enhancing α-1 Blockers With Risk of Developing Parkinson Disease.

JAMA Neurol, 78(4):407-413, 01 Apr 2021

Cited by: 29 articles | PMID: 33523098 | PMCID: PMC7851758

Association Between Burning Mouth Syndrome and the Development of Depression, Anxiety, Dementia, and Parkinson Disease.

JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 146(6):561-569, 01 Jun 2020

Cited by: 30 articles | PMID: 32352482 | PMCID: PMC7193519

Association Between Young-Onset Dementia and Risk of Hospitalization for Motor Vehicle Crash Injury in Taiwan.

JAMA Netw Open, 5(5):e2210474, 02 May 2022

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 35511178 | PMCID: PMC9073564

Association between new-onset Parkinson's disease and suicide risk in South Korea: a nationwide cohort study.

BMC Psychiatry, 22(1):341, 17 May 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 35581575 | PMCID: PMC9115980

1,4,8

1,4,8