Abstract

Free full text

Advances in Understanding the LncRNA-Mediated Regulation of the Hippo Pathway in Cancer

Abstract

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a class of RNA molecules that are longer than 200 nucleotides and cannot encode proteins. Over the past decade, lncRNAs have been defined as regulatory elements of multiple biological processes, and their aberrant expression contributes to the development and progression of various malignancies. Recent studies have shown that lncRNAs are involved in key cancer-related signaling pathways, including the Hippo signaling pathway, which plays a prominent role in controlling organ size and tissue homeostasis by regulating cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation. However, dysregulation of this pathway is associated with pathological conditions, especially cancer. Accumulating evidence has revealed that lncRNAs can modulate the Hippo signaling pathway in cancer. In this review, we elaborate on the role of the Hippo signaling pathway and the advances in the understanding of its lncRNA-mediated regulation in cancer. This review provides additional insight into carcinogenesis and will be of great clinical value for developing novel early detection and treatment strategies for this deadly disease.

Introduction

Cancer is a major disease that threatens human health and life, and its incidence and mortality are increasing rapidly. According to global cancer statistics, approximately 18.1 million new cancer cases were diagnosed and 9.6 million cancer-related deaths occurred worldwide in 2018, and the global burden of cancer has since increased.1 Cancer has the biological characteristics of abnormal cell differentiation and proliferation, uncontrolled cell growth, invasiveness and metastasis, and its development involves genetic alterations in specific genes and their related signaling pathways.2,3 Accumulating studies have identified several canonical signaling pathways that are frequently genetically altered in cancer, such as the Notch, cell cycle, PI3K-Akt-mTOR, RTK-RAS, TGFβ, p53, and β-catenin/Wnt pathways, as well as the Hippo signaling pathway.4 Drugs that target some of these well-known cancer pathways, such as RTKIs that target the RTK-mediated signaling pathways, have been approved and demonstrated clinical efficacy.5 It is hypothesized that signaling pathways play an important role in the development of cancer and provide new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

The Hippo signaling pathway was initially discovered in a genetic screen for genes that inhibit tissue growth in Drosophila.6,7 The Hippo pathway is a conserved signaling cascade that controls tissue growth and organ size during development. Later, studies showed that the Hippo signaling pathway also exists and is highly conserved in mammals.8 Similar to other key cancer pathways, the Hippo pathway is involved in coordinating diverse cellular processes, including cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation. It also participates in stem cell self-renewal and tissue regeneration and mediates immune responses and cell competition, which play a pivotal role in the homeostatic control of multicellular organisms.9–11 However, dysregulation of this pathway appears to be associated with various pathological conditions, especially cancer.12

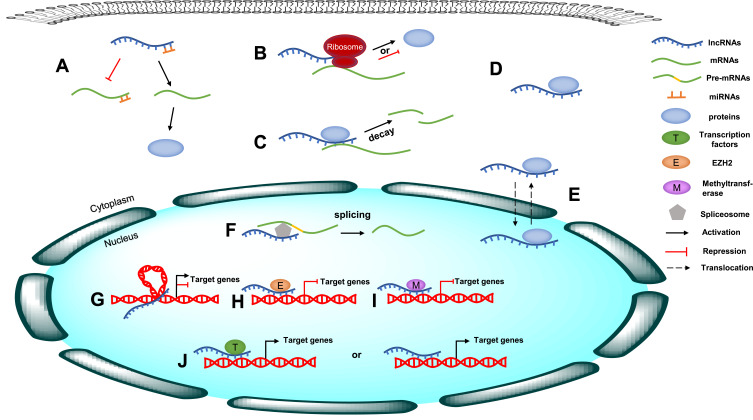

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are defined as a class of RNA molecules that are longer than 200 nucleotides (nt). In the last decade, lncRNAs have been reported to exert crucial effects on multiple biological processes by modulating gene expression via different mechanisms, such as epigenetic, transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation, depending on their subcellular location.13 At the epigenetic level, lncRNAs regulate gene expression through DNA methylation, histone modification, and chromatin remodeling;14 at the transcriptional level, lncRNAs can interact directly with DNA or recruit transcription factors to regulate gene transcription;15 at the posttranscriptional level, lncRNAs usually interact with proteins to regulate their function and localization or with mRNAs to regulate their splicing, translation and stability. In particular, a variety of lncRNAs can act as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) to sponge microRNAs (miRNAs), thus reducing their regulatory effect on target mRNAs16 (Figure 1). In addition, the dysregulation of lncRNAs has been found to be closely associated with the growth, proliferation, invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis of tumor cells.17–19 LncRNAs can function as oncogenes or tumor suppressors to regulate cancer-related signaling pathways either directly or indirectly, thereby influencing the development and progression of various human cancers.20,21 For instance, upregulation of the lncRNA MALAT1 can contribute to the proliferation and cisplatin resistance of gastric cancer cells by regulating the PI3K/Akt pathway.22 Recently, emerging evidence has indicated that lncRNAs are also involved in the regulation of the Hippo signaling pathway,23 but no detailed summary of this role has been presented.

The molecular mechanism of lncRNAs. (A) LncRNAs act as ceRNAs to sponge specific miRNAs, thus reducing their regulatory effect on target mRNAs. (B) LncRNAs interact with mRNAs to regulate their translation. (C) LncRNAs regulate mRNA stability. (D) LncRNAs interact with proteins to regulate their function. (E) LncRNAs regulate the localization of proteins. (F) LncRNAs interact with mRNAs to regulate their splicing. (G) lncRNAs regulate gene expression through chromatin remodeling. (H) lncRNAs regulate gene expression through histone modification. (I) lncRNAs regulate gene expression through DNA methylation. (J) lncRNAs regulate gene transcription through recruiting transcription factors or interacting directly with DNA.

Here, we elaborate on the role of the Hippo signaling pathway and the advances in the understanding of its lncRNA-mediated regulation in cancer. This study provides additional insight into carcinogenesis and will be of great clinical value for developing novel early detection and treatment strategies for cancer.

General Overview of the Hippo Pathway

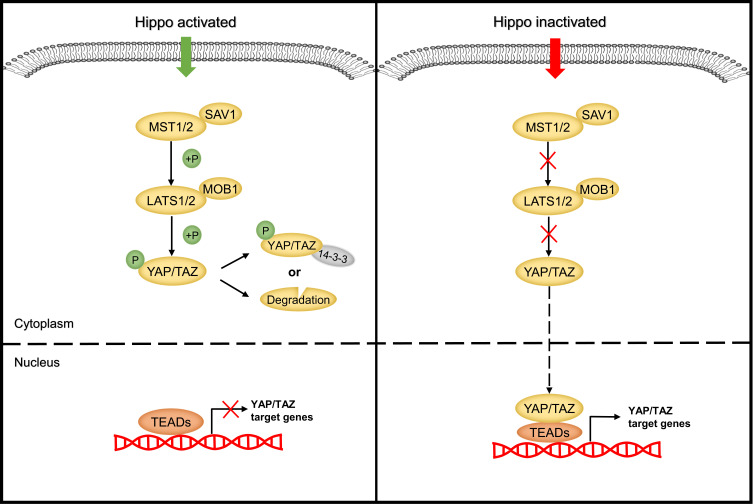

The heart of the Hippo pathway includes the core kinases and downstream effectors. In mammals, the core kinase components of the Hippo pathway comprise the serine/threonine kinases MST1/2 (also known as STK4/3), large tumor suppressor kinase 1/2 (LATS1/2), and their adaptor proteins SAV1 and MOB1.24–26 The downstream effectors of the pathway include two transcriptional coactivators, yes-associated protein (YAP) and its paralog transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ). Due to the lack of a DNA-binding domain, YAP/TAZ mainly interacts with transcriptional factors such as TEA domain family members (TEADs), the key DNA-binding platforms for YAP/TAZ, to regulate target gene expression.27–29 Mechanistically, when the Hippo pathway is activated, MST1/2 complexes with SAV1 to phosphorylate and activate the LATS1/2 kinases, which then form a complex with their regulatory protein MOB1. The activated LATS1/2-MOB1 complex in turn phosphorylates YAP/TAZ and sequesters it in the cytoplasm by promoting its binding with 14-3-3 or degrading it in a ubiquitin-proteasome-dependent manner.30,31 Conversely, when the Hippo pathway is inactivated, dephosphorylated YAP/TAZ translocate into the nucleus, where they bind to and activate TEADs to initiate target gene transcription and promote cell survival, proliferation and self-renewal10,29 (Figure 2). In addition to interacting with TEADs, YAP/TAZ can also interact with other transcription factors, including p73, SMADs, TBX5, Runx1/2, ErbB4, and Pax3, to regulate the transcription of target genes.32 In summary, as the key effectors of the Hippo pathway, phosphorylated YAP/TAZ represent the major players.

The Hippo signaling pathway has been identified as a tumor suppressor pathway, because the loss of core Hippo kinases that suppress YAP/TAZ results in an overgrowth phenotype.33 To date, many studies have confirmed that the expression of YAP/TAZ is upregulated in various cancers and contributes to the tumorigenesis and development of these cancers by regulating cell proliferation, metastasis, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).34–36 However, some studies reported that YAP can be phosphorylated by other kinases to exert the opposite effect. For example, YAP1 phosphorylation mediated by the tyrosine kinase YES1 can induce embryonic stem cell self-renewal.37 Moreover, in some hematological malignancies, YAP promotes cell apoptosis.38 These findings suggest that the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway can exhibit a dual role in carcinogenesis and cancer suppression. Therefore, a better understanding of the upstream regulators of the Hippo pathway is crucial for understanding tumorigenesis.

Studies have shown that the Hippo pathway can respond to a broad range of extracellular and intracellular signals, including cell-cell adhesion, apical-basal polarity, changes in cell shape and size, junctional complexes, G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) stimulation, and the cellular energy status.39–43 To date, more than 20 molecules have been found to regulate the activity of the core components of the Hippo signaling pathway.44 For instance, the apical membrane-associated FERM domain protein Merlin (NF2 in mammals) acts as an important upstream inhibitor of YAP/TAZ, possibly by directly binding to LATS and recruiting it to the cell membrane, where it is activated by the Hippo kinase complex, or by indirectly promoting the assembly of protein scaffolds, for example, by forming a complex with Expanded (Ex) and the WW domain-containing protein Kibra that allows LATS activation.45,46 Moreover, cell junction proteins, such as angiomotin (AMOT) and E-cadherin, have been confirmed to be regulators or interacting partners of Hippo kinases.47,48 In addition, FAT tumor suppressor homolog 4 (FAT4), a member of the atypical cadherin family, can regulate Hippo-YAP pathway activity by acting as a signal receptor to transduce signals produced by extracellular stimulation into cells.49 In addition to the abovementioned regulatory proteins, many other molecules, including MAP/microtubule affinity-regulating kinases 1–4 (MARK1-4), RAS association domain-containing family protein (RASSF), FERM domain-containing 6 (FRMD6), the apical transmembrane protein Crumbs (Crb), the Scribble (Scrib) complex (Scrib/Dlg/Lgl), and so on, have been reported to modulate the Hippo pathway.50–54

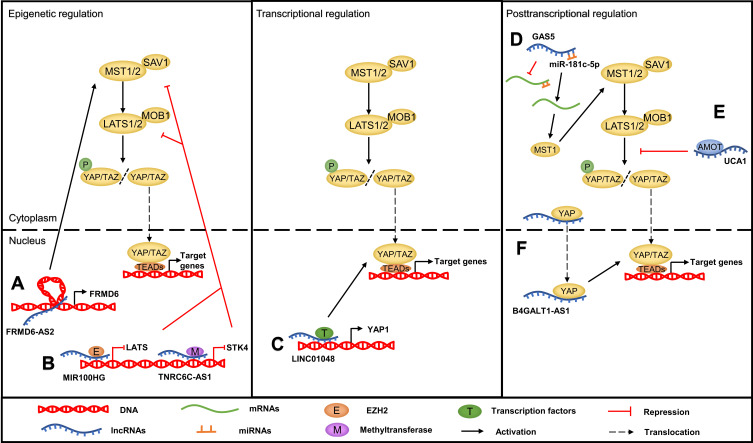

Recently, accumulating evidence has clarified that lncRNAs also participate in Hippo pathway regulation at different subcellular levels depending on their localization. They function as upstream regulators and directly or indirectly target the core components of the Hippo pathway, including MST1/2, LATS1/2 and YAP/TAZ. On the one hand, nuclear lncRNAs can modulate the transcription of the key Hippo kinases or their upstream regulators through diverse mechanisms, including methyltransferase-mediated methylation, chromatin remodeling, and transcription factor recruitment.55–58 On the other hand, cytoplasmic lncRNAs can act as ceRNAs to sponge specific miRNAs, such as miR-200a-3p and miR-497-5p.59,60 In addition, lncRNAs can directly bind to Hippo core proteins to control their subcellular localization or mediate the interactions between them. For example, the lncRNA B4GALT1-AS1 can directly bind to YAP to promote its nuclear translocation, while the lncRNA LEF1-AS1 directly interacts with the LATS1 protein, abolishing the interaction between LATS1 and MOB and leading to inactivation of the Hippo pathway.61,62 LncRNAs can also indirectly influence the Hippo pathway by interacting with the Hippo regulatory proteins. For instance, the lncRNA UCA1 can inactivate the Hippo signaling pathway by binding to AMOT63 (Figure 3).

The mechanism of the lncRNA-mediated regulation of Hippo pathway in cancer. (A) LncRNAs regulate the Hippo pathway through chromatin remodeling, such as FRMD6-AS2. (B) LncRNAs regulate the Hippo pathway through recruiting methyltransferase or EZH2, such as TNRC6C-AS1 and MIR100HG. (C) LncRNA promoting Hippo gene transcription through recruiting transcription factor, such as LINC01048. (D) LncRNAs act as ceRNAs to sponge specific miRNAs, such as GAS5. (E) LncRNAs interact with Hippo pathway components or upstream regulatory proteins to regulate their function, such as UCA1. (F) LncRNAs bind to proteins to control their subcellular localization, such as B4GALT1-AS1.

LncRNAs Regulate the Hippo Pathway in Cancers

Head and Neck Cancers

Thyroid cancer (TC) is one of the most common malignancies in the head and neck and endocrine system.64 The global incidence of thyroid cancer has increased rapidly over the past few decades.65,66 LncRNAs have been reported to play an important role in the development of thyroid cancer, including in the steps of cell growth, survival and metastasis.67 Several studies have indicated that some lncRNAs modulate cell growth via the Hippo signaling pathway. Qin et al68 identified the lncRNA MIR22HG as a prognostic biomarker for thyroid cancer by analyzing data from the TCGA and GEO databases; MIR22HG was downregulated in thyroid cancer, and this downregulation was related to a poor survival outcome. Mechanistically, MIR22HG was shown through bioinformatics analysis to be associated with the Hippo signaling pathway in thyroid cancer. Yang et al69 demonstrated that overexpression of the lncRNA TNRC6C-AS1 promotes the proliferation of thyroid cancer cells while inhibiting their autophagy and apoptosis. A further investigation conducted by Peng et al55 indicated that TNRC6C-AS1 is localized in the nucleus and that its overexpression significantly promotes the methylation of cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) islands in the STK4 promoter region via the recruitment of methyltransferases, thus downregulating the expression of STK4. Simultaneously, the protein expression level of LATS1 and the phosphorylation of YAP were decreased. This finding suggests that TNRC6C-AS1 acts as an oncogene by inactivating the Hippo signaling pathway in thyroid cancer. Moreover, Wu et al59 found that the lncRNA SNHG15 is markedly upregulated in papillary thyroid cancer cell lines and tissues and that interference with SNHG15 can inhibit cell growth and migration. Further mechanistic investigation showed that SNHG15 can bind to miR-200a-3p as a ceRNA to upregulate the expression of YAP1, the downstream effector of the Hippo signaling pathway. In addition, the mRNA and protein expression levels of MST1/LATS1 were downregulated by SNHG15. Recently, Li et al70 reported that overexpressed UCA1 appreciably promotes TPC-1 thyroid cancer cell proliferation and EMT as well as suppresses TPC-1 cell apoptosis by sponging miR-15a, thus inhibiting the Hippo signaling pathway.

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma accounts for 95% of head and neck cancers, among which oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most common.71,72 Zhang et al62 found that expression of the lncRNA LEF1-AS1 was notably higher in OSCC tissues than in adjacent noncancerous tissues and that a high LEF1-AS1 expression level was associated with poor prognosis. Functional studies revealed that overexpressed LEF1-AS1 can promote cell survival, proliferation and migration, as well as inhibit apoptosis, by directly interacting with LATS1. Therefore, the binding of LATS1 to MOB is abolished, leading to Hippo signaling pathway inactivation and decreased YAP phosphorylation. Notably, accumulating evidence has suggested that lncRNAs also participate in regulating multidrug resistance.73,74 For example, Zhu et al75 reported that a high level of the lncRNA MRVI1-AS1 can increase the sensitivity of nasopharyngeal cancer (NPC) cells to paclitaxel in vitro and in vivo. In addition, this group confirmed that MRVI1-AS1 sensitizes NPC cells to paclitaxel by targeting miR-513a-5p and miR-27b-3p to upregulate activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3). Moreover, a positive feedback loop between ATF3 and MRVI1-AS1 has been identified, which promotes the expression of RASSF1, a regulatory factor of the Hippo signaling pathway, further decreasing the expression of TAZ at the posttranslational level. In summary, this finding indicates that MRVI1-AS1 can increase the paclitaxel sensitivity of NPC cells via the Hippo signaling pathway.

Thoracic Cancers

Lung cancer is the most common cancer with high morbidity and mortality.76 Qiao et al77 speculated that lncRNAs may play an important role in lung cancer in nonsmoking female patients. They used GEO2R, an interactive web analysis tool, to screened eight lncRNAs differentially expressed in lung cancer samples from three GEO datasets (GSE19804, GSE31210, and GSE31548). Additionally, 19 miRNAs and 38 mRNAs were associated with these 8 key lncRNAs. Functional and pathway enrichment analyses using the DAVID databases revealed that these target genes were related to the Hippo signaling pathway. Moreover, Zhao et al78 found that the expression level of the lncRNA NSCLCAT1 is elevated in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and that overexpressed NSCLCAT1 can facilitate the proliferation, migration and invasion of NSCLC cells while inhibiting their apoptosis. Further investigation revealed that NSCLCAT1 can inactivate the Hippo signaling pathway by repressing the transcription of the cadherin1 (CDH1) gene, which encodes E-cadherin, a cell-cell adhesion molecule that is expressed in the epithelium and has been determined to be a direct regulator of the Hippo pathway.79,80

Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women worldwide.81 Estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer accounts for approximately 70% to 80% of breast cancers, and antihormone therapy is the major clinical treatment strategy. However, approximately 30–50% of patients develop resistance to endocrine therapy.82,83 Liu et al84 found that breast cancer patients with high expression levels of the lncRNA CYTOR are likely exhibit tamoxifen resistance. The results of RT-qPCR and dual luciferase reporter assays showed that CYTOR can directly bind to miR-125a-5p as a ceRNA to elevate the expression of serum response factor (SRF), which enhances the transcription of the Hippo effector TAZ by binding to its promoter.85 This study revealed that CYTOR contributes to the development of tamoxifen resistance by inactivating the Hippo signaling pathway. Moreover, several lncRNAs have been proven to promote the initiation and development of breast cancer by regulating the Hippo pathway. For instance, Li et al86 reported that the lncRNA ZFHX4-AS1 is upregulated in breast cancer. ZFHX4-AS1 is distributed mainly in the cytoplasm and negatively targets FAT4, which has been confirmed to act as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer.87 Furthermore, RT-qPCR and Western blot analysis showed that ZFHX4-AS1 overexpression decreases FAT4 expression at both the mRNA and protein levels but promotes the expression of both YAP and TAZ. In addition, suppression of ZFHX4-AS1 and the Hippo signaling pathway inhibits the proliferation, invasion and migration of breast cancer cells but promotes their apoptosis. Recently, Qiao et al88 observed that the expression of LINC00673 is elevated in breast cancer tissues and cell lines, while its downregulation can inhibit cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, LINC00673 was found to upregulate MARK4 by competing for miR-515-5p binding and further inactivating the Hippo signaling pathway. Moreover, MARK4 has been reported to function as an activator of YAP and TAZ by binding to MST and SAV.50 Another lncRNA, Linc-OIP5, was reported to act as an oncogenic regulator in breast cancer, and knockdown of Linc-OIP5 was found to significantly inhibit the proliferation, migration and invasion of breast cancer cells but induce their apoptosis via YAP1 downregulation-mediated suppression of the Hippo signaling pathway.89 Additionally, a previous study showed that the lncRNA MAYA participates in the activation of YAP to stimulate the target gene connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), a signature gene that mediates breast cancer bone metastasis.90 The molecular mechanism underlying the effects of MAYA indicates that MAYA can directly bind to both the adaptor protein LLGL2 and the methyltransferase NSUN6 to form an RNA-protein complex. This complex further methylates MST1 at Lys59, which abolishes the kinase activity of MST1 and activates YAP.91 This result indicates the promising therapeutic value of MAYA against breast cancer bone metastasis.

Abdominal Cancers

Gastric carcinoma is one of the most frequently diagnosed cancers and the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide.1 A previous analysis of TCGA data showed that 3 lncRNAs (CYP4A22-AS1, AP000695.6, and RP11-108M12.3) are differentially expressed in gastric cancer tissues compared to adjunct noncancerous tissues and are significantly related to the prognosis of patients with gastric cancer. Among these lncRNAs, AP000695.6 and RP11-108M12.3 are positively associated and CYP4A22-AS1 is negatively associated with OS. In addition, functional enrichment analysis showed that these 3 key lncRNAs are associated mainly with the Hippo signaling pathway and involved in the cellular apoptotic process. This finding provides a useful prognostic biomarker for gastric cancer.92 Similarly, Liu et al60 reported that LINC00662 expression is significantly increased in gastric cancer tissues and that a high level of LINC00662 expression is strongly related to poor prognosis. Moreover, siRNA-mediated silencing of LINC00662 restores the response of gastric cancer cells to 5-fluorouracil (FU) and decreases their proliferation. Functional analysis revealed that LINC00662 can inhibit the Hippo signaling pathway by directly binding to miR-497-5p, which leads to upregulation of YAP1. In contrast, Chen et al93 found that lincRNA-p21 acts as a tumor suppressor in gastric cancer progression; a lower level of lincRNA-p21 was associated with a deeper invasion depth, higher grade, higher incidence of distant metastasis and more advanced TNM stage, suggesting the prognostic and therapeutic potential of this lncRNA in gastric cancer. Further investigation demonstrated that knockdown of lincRNA-p21 promotes proliferation and EMT in gastric cancer cell lines, possibly by increasing the protein and mRNA levels of YAP and facilitating YAP translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in a Hippo-independent manner. Colorectal cancer remains a threat to human health, with increasing incidence rates in many countries.66 To understand the role of lncRNAs in colorectal cancer progression, Zhang et al94 used TCGA data to construct a ceRNA network comprising 62 lncRNAs, 30 miRNAs, and 59 mRNAs. The target genes in this lncRNA-associated ceRNA network significantly involved in oncogenic pathways, including the Hippo signaling pathway, suggesting that this pathway participates in colorectal cancer tumorigenesis. Moreover, a recent study61 reported that the lncRNA B4GALT1-AS1 is significantly upregulated in colon cancer cells. Both the in vitro and in vivo results indicated that knockdown of B4GALT1-AS1 can attenuate the stemness as well as the migration, invasion, and EMT processes in colon cancer cells. Ribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation (RIP) analysis showed that the YAP protein is the direct target of B4GALT1-AS1; its transcriptional activity and nuclear translocation are suppressed by B4GALT1-AS1 knockdown, while its overexpression reverses B4GALT1-AS1 knockdown-induced inhibitory effects on colon cancer cells.

Liver cancer is the second most common cause of cancer-related death in males; HCC is the most common histologic type, accounting for approximately 80% of total liver cancer cases.95 The lncRNA PVT1 is located in the known cancer-related chromosomal region 8q24 and has been reported to function as an oncogene in many different cancers, including HCC.96–98 The results of a comprehensive analysis conducted by Zhang et al99 indicated that PVT1 is upregulated in HCC and is markedly related to patient sex, patient race, vascular invasion and pathological grade. Additionally, the ROC curve indicated the high diagnostic value of PVT1 in HCC. Furthermore, this group clarified that PVT1 may play a carcinogenic role in HCC possibly through modulating the Hippo pathway. Notably, the lncRNA UCA1 is another well-known unfavorable regulator in many malignancies.100,101 Consistent with these previous findings, Qin et al102 demonstrated that the expression of UCA1 is significantly upregulated in HCC tissues, and a meta-analysis showed that patients with a high level of UCA1 are more likely to have larger tumors, more advanced TNM stages and shorter OS times than those with a low level of UCA1. In addition, the results of in vitro experiments and KEGG pathway analysis indicated that UCA1 can promote the proliferation and inhibit the apoptosis of HCC cells via the Hippo signaling pathway. Ni et al103 found that expression of the lncRNA uc.134 is markedly downregulated in HCC samples and that a low expression level of uc.134 is closely related to poor prognosis. The results of in vivo and in vitro experiments indicated that uc.134 exerts suppressive effects on the proliferative, invasive, and metastatic abilities of HCC cells. In addition, the findings indicated that uc.134 (nt 1408–1867) can directly bind to the CUL4A protein (aa 592–759), which is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that mediates the ubiquitination and degradation of LATS1,104 to form a RNP complex and retain CUL4A in the nucleus. Therefore, CUL4A-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of LATS1 in the cytoplasm is inhibited by uc.134, leading to the activation of the Hippo kinase and phosphorylation of YAP at Ser127. Hepatoblastoma (HB) is a common type of liver cancer in children classified into a variety of subgroups.105 By analyzing the GSE75271 dataset, Lv et al106 found LINC01314 overexpression in the subgroups with good prognosis. Further investigation demonstrated that overexpression of LINC01314 can reduce HepG2 cell proliferation, migration, and invasion via the Hippo pathway by increasing the expression of MTS1 and facilitating the phosphorylation of LATS1 and YAP.

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most lethal cancers, with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 5%.107 Zhang et al108 found that consistent with its role in HCC, UCA1 is closely associated with clinicopathological features, advanced clinical stage, and poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer, and functional investigation proved that it could enhance the migratory and invasive abilities of pancreatic cancer cells. Mechanistically, Zhang et al revealed that UCA1 upregulates YAP expression and promotes YAP nuclear translocation by interacting with MOB1, LATS1 and YAP to form a shielding complex, consequently enhancing the luciferase activity of TEAD. Moreover, Western blotting and qRT-PCR results showed the existence of a positive feedback loop between YAP and UCA1. Zhou et al109 claimed that the silencing of lncRNA MALAT1 contributes to the apoptosis of pancreatic cancer cells, accompanied by the attenuation of cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. Mechanistic investigation showed that MALAT1 interacts with the Hippo signaling pathway by downregulating the expression of LATS1 but upregulating the expression of YAP1. In addition, Gao et al110 focused on the impact of the lncRNA GAS5 on the chemoresistance of pancreatic cancer cells. They observed that the expression of GAS5 was markedly decreased in drug-resistant SW1990/GEM and PATU8988/5-FU cells, while miR-181c-5p showed the opposite trend. Further study showed that GAS5 overexpression improved the response of drug-resistant cells to gemcitabine (GEM) and 5-FU treatment and decreased cell viability, possibly by downregulating miR-181c-5p expression, subsequently increasing MST1 expression and YAP phosphorylation. This finding suggests that the GAS5/miR-181c-5p/Hippo signaling axis is a potential therapeutic target for conquering chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer.

Central Nervous System Tumors

Glioma is the most common type of primary brain tumor, accounting for 51.4% of all primary brain tumors, and glioblastoma is the most aggressive glioma, with high mortality in adults.111,112 In the GSE2223 and GSE59612 datasets Wang et al113 screened 712 lncRNAs dysregulated in glioblastoma multiforme compared with normal control tissues. Among these lncRNAs, DLEU1 was found to be significantly upregulated and to interact with 315 miRNAs and 105 mRNAs associated mainly with tumorigenesis-related terms and pathways, including the Hippo signaling pathway. Su et al114 reported that overexpression of the lncRNA BDNF-AS markedly inhibits the proliferation, migration, and invasion of glioblastoma cells while increasing their apoptosis, suggesting that this lncRNA functions as a tumor suppressor in glioblastoma. Furthermore, this group confirmed that BDNF-AS overexpression can decrease the expression level and mRNA half-life of retina and anterior neural fold homeobox 2 (RAX2), a member of the RAX transcription factor family that is essential for vertebrate eye development, through STAU1-mediated mRNA decay (SMD).115 In this process, imperfect base pairing between the Alu elements of BDNF-AS and RAX2 mRNA forms a SBS sequence, which is recognized by STAU1 and results in RAX2 decay. Subsequently, loss of RAX2 induces upregulation of discs large homolog 5 (DLG5), which is involved in maintaining cell polarity,116 further suppressing the malignant biological behaviors of glioblastoma cells by increasing the phosphorylation of YAP. Gong et al117 observed an increased level of the lncRNA KCNQ1OT1 in glioma tissues and cells, and knockdown of KCNQ1OT1 significantly inhibits the proliferation, migration and invasion but induces the apoptosis of glioma cells. In addition, functional studies showed that knockdown of KCNQ1OT1 can enhance the expression of miR-370, thus restoring the suppressive effects of miR-370 on the expression of Cyclin E2 (CCNE2), a member of the Cyclin E family that is involved in G1/S transition of the cell cycle,118 which are mediated by targeting its 3ʹ-UTR. Consequently, suppressed CCNE2 upregulates the phosphorylation of YAP, the core effector of the Hippo pathway. A recent study119 reported that LINC00473 was notably upregulated in glioma and associated with poor survival outcomes. Moreover, that group concluded that LINC00473 downregulated miR-195-5p by functioning as a ceRNA sponge, possibly promoting the expression of YAP1 and TEAD1 and thereby inducing the proliferation, invasion and migration of glioma cells, as well as inhibiting their apoptosis. Based on this finding, LINC00473 and miR-195-5p are believed to be therapeutic targets for glioma. Medulloblastoma (MB) is the most common pediatric malignant brain tumor; MB originates mainly from cerebellar granule neuron progenitors and has a dismal overall prognosis.120 Zhang et al121 found that overexpression of the lncRNA Nkx2-2as can impair the colony formation and invasion abilities and induce the apoptosis of MB cells; in addition, knockdown of Nkx2-2as exerts the opposite effects on these cells. Functional analysis demonstrated that Nkx2-2as functions as a ceRNA to tether miR-103a/107 and miR-548m, resulting in sequestration of these miRNAs from their targets, such as B-cell translocation gene 2 (BTG2) and LATS1/2, which play a tumor-suppressive role in MB.122 Consequently, the protein levels of BTG2 and LATS1/2 are increased in MB tissues and further lead to activation of the Hippo signaling pathway.

Urogenital Cancers

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common form of kidney cancer, accounting for over 90% of renal malignancies.123 Accumulating evidence has shown that the lncRNA TUG1 acts as a tumor promoter in many cancer types, including RCC.124,125 Consistent with these previous studies, Liu et al126 reported that TUG1 is overexpressed in RCC tissues and positively regulates cell proliferation and migration. Mechanistically, TUG1 was proven to elevate YAP expression at both the mRNA and protein levels via a ceRNA mechanism by competing for miR-9 binding but was shown to have no influence on either the nuclear or cytoplasmic distribution of YAP. In addition, Hu et al127 clarified that interference with the lncRNA HOTAIR results in marked reductions in cell proliferation and migration in vitro and inhibits tumor growth in vivo. In addition, high levels of HOTAIR expression are closely related to poor patient outcomes, suggesting that HOTAIR may also act as an oncogenic regulator in RCC. Moreover, this group found a negative correlation between HOTAIR and SAV1. Further investigation indicated that HOTAIR promotes the malignant behavior of RCC cells by inactivating the Hippo pathway through direct binding to the SAV1 protein, the core component of the Hippo pathway.

Epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC) is the most lethal gynecological malignancy, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 50%.128 Lin et al63 confirmed that UCA1 contributes to EOC tumorigenesis and development. Tumor growth was greatly suppressed in mice injected with UCA1 knockout (KO) ovarian cancer cells compared with mice injected with UCA1 wild-type (WT) ovarian cancer cells. Furthermore, this group confirmed that UCA1 can inhibit YAP phosphorylation at Ser127 and enhance YAP nuclear translocation by directly binding to AMOTp130, a known regulator of the Hippo pathway,129 to promote the interaction between AMOT and YAP, whereas the interaction between pLATS1/2 and YAP is abolished. Thus, the expression of YAP downstream target genes involved in tumor growth, such as CTGF and AXL, is increased. Uterine corpus endometrial cancer (UCEC) originates from the endometrial epithelium and is another of the most common gynecological malignancies.128 Bioinformatic analysis conducted by Wang et al56 showed that the expression of antisense lncRNA FRMD6-AS2 is reduced in UCEC, while high expression of FRMD6-AS2 predicts a better OS in patients with UCEC. In addition, the Hippo signaling pathway is dramatically enriched in genes targeted by FRMD6-AS2. Consistent with this finding, functional studies verified that FRMD6-AS2 can activate the Hippo signaling pathway by upregulating FRMD6 expression by promoting chromatin loop formation in the promoter region of FRMD6, thereby inhibiting the growth, migration and invasion of UCEC cells. As an upstream regulator of the conserved Hippo signaling pathway, FRMD6 has been reported to play a tumor-suppressive role in breast cancer and glioblastoma.130,131

Other Cancers

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant proliferative disease of plasma cells and is usually confined to the bone marrow.132 Sun et al133 found that the lncRNA MALAT1 is upregulated in MM and is negatively associated with miR-181a-5p. Moreover, this group demonstrated that in the context of MALAT1 interference, the proliferative and adhesive abilities of myeloma cells were inhibited, whereas apoptosis was promoted; miR-181a-5p overexpression exhibited similar effects on myeloma cells. Mechanistic investigation revealed that MALAT1 can act as a ceRNA to sponge miR-181a-5p, while interference with MALAT1 expression can upregulate miR-181a-5p to increase the expression of LATS1 and phosphorylation of YAP, thereby suppressing malignant behaviors of myeloma cells via Hippo pathway activation. Osteosarcoma is the most frequently diagnosed bone tumor in adolescents.134 Su et al57 observed a high level of the lncRNA MIR100HG in osteosarcoma tissues and cell lines and found that high MIR100HG expression is notably associated with poor prognosis in patients with osteosarcoma. MIR100HG knockdown leads to suppressed cell proliferation, cell cycle arrest, and enhanced apoptosis, but these effects can be partially abrogated by knockdown of either LATS1 or LATS2, implying that LATS1/2 are the underlying targets of MIR100HG. Mechanistically, Su et al confirmed that MIR100HG is localized in the nucleus and can epigenetically silence LATS1/2 by recruiting EZH2, a well-known histone methylation regulator, to the LATS1/2 promoter region, resulting in inactivation of the Hippo pathway. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC), which is derived from keratinocytes, is the second most common cause of nonmelanoma skin cancer, and lncRNAs play an important role in its development and progression.135 By analyzing data from the TCGA database, Chen et al58 found that upregulation of LINC01048 is closely related to a worse survival outcome in CSCC than low expression of LINC01048. The results of in vivo and in vitro experiments indicated that knockdown of LINC01048 negatively regulates the proliferation of CSCC cells but promotes their apoptosis, suggesting the carcinogenic role of LINC01048 in CSCC. Furthermore, mechanistic experiments showed that LINC01048 interacts with the TAF15 protein, which has been identified as a transcriptional activator,136 and upregulates its expression; moreover, LINC01048 increases the binding of TAF15 to the YAP1 promoter, thus activating YAP1 transcription, in CSCC cells. In conclusion, LINC01048 may have prognostic or therapeutic value in CSCC.

Clinical Application of LncRNAs in Hippo Pathway-Related Cancers

Diagnosis and Prognosis

The expression of lncRNAs is highly tissue specific;137 therefore, there has been great interest in the utilization of lncRNAs as potential biomarkers for early detection, diagnosis and prognosis. According to the studies presented in this review, a group of lncRNAs have been identified as dysregulated in Hippo pathway-related cancers. Some of the Hippo-related lncRNAs are significantly correlated with clinicopathological features and clinical prognoses in cancers. For example, in HCC patients, the expression of UCA1 is significantly upregulated and shows a positive association with a large tumor size, an advanced TNM stage and a poor prognosis.102 In contrast, a low level of lincRNA-p21 is closely related to a deep invasion depth, distant metastasis and an advanced TNM stage in gastric cancer.93 As the key downstream effectors of the Hippo pathway, YAP/TAZ have been found to be upregulated in multiple cancers, such as lung cancer and breast cancer, and are correlated with a poor prognosis.36,138 For instance, YAP/TAZ are highly expressed in most NSCLC specimens and associated with lymph node metastasis and short OS.139,140 These findings suggest that YAP/TAZ would be novel prognostic biomarkers.

Treatment

Many of the lncRNAs presented in this review have been reported to participate in cancer development and drug resistance by modulating the activity of the Hippo pathway, making them potential therapeutic targets. Research focused on targeting lncRNAs as cancer treatment is underway. In fact, the direct or indirect silencing of lncRNA expression is the most common strategy. Advancements in biological agents targeting lncRNAs, such as antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), have indicated the feasibility of lncRNAs as a therapeutic target.141–143

Numerous studies have shown that the Hippo signaling pathway not only regulates the growth of tumor cells but is also closely related to the resistance of tumor cells to chemotherapy drugs.75,84 Hence, the core components of the Hippo pathway are considered potential therapeutic targets for cancer. Given that the transcriptional activity of YAP/TAZ is mediated by TEADs, blocking the formation of the YAP/TAZ-TEAD complex may provide a new treatment strategy for human cancers. Recently, Verteporfin (Vp) was identified as an inhibitor of YAP/TAZ-TEAD function. Yu et al144 reported that Verteporfin exhibits an antitumorigenic effect in vitro. This drug can selectively kill uveal melanoma cells with elevated YAP activity. It may also provide another way to limit YAP/TAZ function by modifying the upstream regulatory signals of the Hippo pathway, such as GPCR and F-actin.39,145 However, because these factors are not pathway specific and have corresponding physiological functions, the clinical feasibility of this method still needs further exploration.

Discussion

Cancer is a common disease that seriously threatens human health worldwide. The Hippo signaling pathway has been determined to play a crucial role in tumorigenesis and development in a wide range of cancers, such as thyroid, breast, and gastric cancers. Numerous studies have reported that lncRNAs can modulate the Hippo signaling pathway in cancer. In this review, we described the core signaling cascade of the Hippo pathway and highlighted the important role of lncRNAs in the regulation of this pathway in cancer.

As mentioned above, accumulating evidence indicates that the Hippo signaling pathway plays an important role in the development and progression of human cancers. In mammals, the upstream kinases of the Hippo pathway consist of the tumor suppressors MST1/2 and LATS1/2 and their adaptor proteins SAV1 and MOB1, while the downstream effectors consist of the oncogenes YAP/TAZ.24–26 Similar to other central pathways, the conserved Hippo pathway can respond to diverse extracellular and intracellular signals to regulate the balance between cell proliferation and apoptosis to control tissue homeostasis. However, deregulation of this pathway destroys the balance and leads to an overgrowth phenotype and tumorigenesis.146,147 According to this review, the lncRNA-regulated Hippo pathway can act as both a suppressor and promoter of tumor progression. Therefore, a better understanding of the complex mechanisms underlying the effect of lncRNAs on the Hippo pathway is necessary for their further clinical applications.

As a group of noncoding RNA transcripts, lncRNAs have been confirmed to be functional elements that are involved in diverse biological processes in human malignancies, such as cell survival, carcinogenesis, tumor invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis.148 Studies have reported that lncRNAs are involved in the regulation of multiple key cancer-related pathways, such as the Notch, PI3K-Akt-mTOR, and β-catenin/Wnt pathways.149–151 In this review, we summarized 32 Hippo pathway-associated lncRNAs in different cancers, 21 of which are upregulated and 11 of which are downregulated (Table 1). Similar to regulating other cancer-related pathways, lncRNAs can also regulate the activity of the Hippo pathway at the epigenetic, transcriptional, and posttranscriptional levels by interacting with DNA molecules, RNA molecules or proteins depending on their subcellular localization. Mechanistically, in the nucleus, lncRNAs participate in the transcription of the core Hippo kinases or directly bind to them to control their subcellular localization.55,57 In the cytoplasm, lncRNAs can function as decoys to compete for binding sites on miRNAs or interact with proteins, including Hippo pathway components and their regulatory proteins, to affect their stability and activity.62,63 Compared with other signaling pathways, a certain lncRNA may modulate the Hippo pathway in a different manner. For example, Gong et al152 found that HOTAIR was upregulated in HCC cells. HOTAIR targets the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway by acting as a ceRNA to sponge miR-217-5p, thereby promoting the development of HCC. However, in the Hippo pathway, HOTAIR can directly bind to the adaptor protein SAV1, leading to the inactivation of this pathway and promoting the malignant behavior of tumor cells.127 Additionally, due to the tissue specificity of lncRNAs, the regulatory mechanism of dysregulated lncRNAs in the Hippo pathway in different cancers also differs. As mentioned in our review, UCA1 is upregulated in both thyroid cancer and pancreatic cancer. This lncRNA inhibits the Hippo pathway by sponging miR-15a in thyroid cancer but promotes the activity of YAP by forming a shielding complex with MOB1, LATS1 and YAP in pancreatic cancer.70,108

Table 1

LncRNA-Mediated Regulation of the Hippo Pathway in Cancer

| Cancer | LncRNAs | Expression | Target | Mechanisms | Functions | Clinical Value | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck cancer | Thyroid cancer | MIR22HG | Down | – | – | – | Prognosis | [68] |

| TNRC6C-AS1 | Up | STK4 | TNRC6C-AS1↑-STK4↓ | Promote proliferation, inhibit autophagy and apoptosis | Therapy | [55] | ||

| SNHG15 | Up | YAP1 | SNHG15↑-miR-200a-3p↓-YAP1↑ | Promote cell growth and migration | Therapy | [59] | ||

| UCA1 | Up | - | UCA1↑-miR-15a↓-Hippo inactivated | Promote cell proliferation and EMT, suppress cell apoptosis | Therapy | [70] | ||

| OSCC | LEF1-AS1 | Up | LATS1 | LEF1-AS1↑-abolish the binding of LATS1 to MOB | Promote cell survival, proliferation and migration, inhibit cell apoptosis | Prognosis, therapy | [62] | |

| NPC | MRVI1-AS1 | Down in the paclitaxel-resistant strains | TAZ | MRVI1-AS1↓-miR-513a-5p/miR-27b-3p↑-ATF3↓-RASSF1↓-TAZ↑ | Increase NPC paclitaxel sensitivity | Therapy | [75] | |

| Thoracic cancer | Lung cancer | NSCLCAT1 | Up | - | NSCLCAT1↑-CDH1↓ | Facilitate cell proliferation, migration and invasion, inhibit apoptosis | Therapy | [78] |

| Breast cancer | CYTOR | Up in the tamoxifen-resistant cell lines | TAZ | CYTOR↑-miR-125a-5p↓-SRF↑-TAZ↑ | Promote tamoxifen resistance | Therapy | [84] | |

| ZFHX4-AS1 | Up | YAP/TAZ | ZFHX4-AS1↑-FAT4↓-YAP/TAZ↑ | Promote proliferation, invasion and migration, inhibit apoptosis | Therapy | [86] | ||

| LINC00673 | Up | MST/SAV | LINC00673↑-miR-515-5p↓-MARK4↑-attenuate the binding of MST/SAV to LATS | Promote cell proliferation | Therapy | [88] | ||

| Linc-OIP5 | Up | YAP1 | Linc-OIP5↑-YAP1↓ | Promote proliferation, migration and invasion, inhibit apoptosis | Therapy | [89] | ||

| MAYA | Up | MST1 | MAYA↑-bind to LLGL2 and NSUN6-MST1 methylated | Mediate bone metastasis | Therapy | [91] | ||

| Abdominal cancer | Gastric carcinoma | AP000695.6, RP11-108M12.3 | Down | - | - | - | Prognosis | [92] |

| CYP4A22-AS1 | Up | - | - | - | Prognosis | [92] | ||

| LINC00662 | Up | YAP1 | LINC00662↑-miR-497-5p↓-YAP1↑ | Increase proliferation, decrease the sensitivity to 5-FU | Prognosis, therapy | [60] | ||

| lincRNA-p21 | Down | YAP | lincRNA-p21↓-YAP↑ | Inhibit cell proliferation and EMT process | Prognosis, therapy, invasion depth grade, metastasis, TNM stage | [93] | ||

| Colorectal cancer | B4GALT1-AS1 | Up | YAP | B4GALT1-AS1↑-YAP nuclear translocation↑ | Promote cell stemness, migration, invasion, and EMT process | Therapy | [61] | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | PVT1 | Up | - | - | - | Diagnosis, gender, race, vascular invasion and pathological grade | [99] | |

| UCA1 | Up | - | - | Promote cell proliferation, inhibit apoptosis | Prognosis, tumor size, TNM stages | [102] | ||

| uc.134 | Down | LATS1 | uc.134↓-CUL4A nuclear export↑-LATS1↓ | Inhibit cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis | Prognosis, therapy | [103] | ||

| LINC01314 | Down | MTS1 | LINC01314↓-MTS1↓ | Reduce cell proliferation, migration, and invasion | Prognosis, therapy | [106] | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | UCA1 | Up | YAP | UCA1↑-YAP↑ | Promote migration and invasion | Prognosis, therapy, clinicopathologic-al features, clinical stage | [108] | |

| MALAT1 | Up | LATS1/YAP1 | MALAT1↑-LATS1↓/YAP1↑ | Promote proliferation, migration and invasion, inhibit apoptosis | Therapy | [109] | ||

| GAS5 | Down in the drug-resistant cell lines | MST1 | GAS5↓-miR-181c-5p↑-MST1↓ | Antagonize the development of multidrug resistance, inhibit cell viability | Therapy | [110] | ||

| Central nervous system tumor | Glioblastoma | BDNF-AS | Down | YAP | BDNF-AS↓-RAX2↑-DLG5↓-YAP phosphorylated↓ | Inhibit proliferation, migration, and invasion, increase apoptosis | Therapy | [114] |

| Glioma | KCNQ1OT1 | Up | YAP | KCNQ1OT1↑-miR-370↓-CCNE2↑-YAP phosphorylated↓ | Promote cell proliferation, migration and invasion, inhibit apoptosis | Therapy | [117] | |

| LINC00473 | Up | YAP1 | LINC00473↑-miR-195-5p↓-YAP1↑ | induce cell proliferation, invasion and migration, reduce apoptosis | Prognosis, therapy | [119] | ||

| Medulloblastoma | Nkx2-2as | Down | LATS1/2 | Nkx2-2as↓-miR-103a/107, miR-548m↑-LATS1/2↓ | impair colony formation and invasion, induce cell apoptosis | Therapy | [121] | |

| Urogenital cancer | RCC | TUG1 | Up | YAP | TUG1↑-miR-9↓-YAP↑ | promote cell proliferation and migration | Therapy | [126] |

| HOTAIR | Up | SAV1 | HOTAIR↑-SAV1 activity↓ | promote cell proliferation, migration, and tumor growth | Prognosis, therapy | [127] | ||

| EOC | UCA1 | Up | YAP | UCA1↑-the interaction between AMOT and YAP↑-YAP activity↑ | promote tumor growth | Therapy | [63] | |

| UCEC | FRMD6-AS2 | Down | - | FRMD6-AS2↓-FRMD6↓-Hippo inactivated | inhibit cell growth, migration and invasion | Therapy | [56] | |

| Others | Multiple myeloma | MALAT1 | Up | LAST1 | MALAT1↑-miR-181a-5p↓-LAST1↓ | promote proliferation and adhesion, inhibit apoptosis | Therapy | [133] |

| Osteosarcoma | MIR100HG | Up | LATS1/2 | MIR100HG↑-recruit EZH2-LATS1/2↓ | induce cell proliferation, cell cycle arrest, inhibit apoptosis | Prognosis, therapy | [57] | |

| CSCC | LINC01048 | Up | YAP1 | LINC01048↑-recruit TAF15-YAP1↑ | promote cell proliferation, inhibit apoptosis | Prognosis, therapy | [58] |

From a clinical perspective, several studies have noted that molecules involved in the lncRNA-Hippo regulatory axis (eg, the lncRNA GAS5/miR-181c-5p/YAP axis in pancreatic cancer110) might be candidate therapeutic and prognostic biomarkers. However, it should be noted that there are still many limitations. First, as a prognostic biomarker, it is necessary to determine whether the expression pattern of an lncRNA or YAP is sufficiently stable It is also essential to establish a standard analytical protocol that includes sample extraction, detection methods and standard values. Second, in most cases, lncRNAs may not be the only cause of a dysregulated Hippo signaling pathway. In addition, there is crosstalk between the Hippo pathway and other signaling pathways. How to selectively target the Hippo pathway and ensure its physiological functions makes the clinical application of this therapeutic strategy highly challenging. Therefore, further studies are needed to test whether these molecules can be applied clinically for cancer therapy.

However, we still know little about the regulation of the Hippo pathway by lncRNAs, and additional lncRNAs in the regulatory network of the Hippo signaling pathway remain to be discovered. Studies have indicated that lncRNAs do not regulate Hippo pathway activity through a single molecular mechanism, some of which have been described above. It is noted that the correlation between lncRNAs and the Hippo pathway tend to show cancer type specificity and spatiotemporal differences, and crosstalk with other pathways. Further investigations into the novel molecular signals regulating the Hippo pathway will be of paramount importance for understanding not only this pathway but also carcinogenesis.

In conclusion, we highlighted that lncRNAs are part of the Hippo signaling pathway regulatory network in cancer and summarized the complex underlying mechanisms, providing novel insight into carcinogenesis. In addition, these observations indicate that targeting these lncRNAs or Hippo pathway components is a new strategy for detecting and treating cancer.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81672307, 81871871), Key Research and Development plan (Social development) of science and technology department of Jiangsu Province (No.BE2019760) and the Medical Innovation Team Foundation of the Jiangsu Provincial Enhancement Health Project (No. CXTDA2017021).

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

Articles from OncoTargets and Therapy are provided here courtesy of Dove Press

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.2147/ott.s283157

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://www.dovepress.com/getfile.php?fileID=68268

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Article citations

Relationship between long non-coding RNAs and Hippo signaling pathway in gastrointestinal cancers; molecular mechanisms and clinical significance.

Heliyon, 10(1):e23826, 22 Dec 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38226210 | PMCID: PMC10788524

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Prognostic Value of Immune-Related Multi-IncRNA Signatures Associated With Tumor Microenvironment in Esophageal Cancer.

Front Genet, 12:722601, 30 Sep 2021

Cited by: 11 articles | PMID: 34659345 | PMCID: PMC8516150

The Role of Long Non-coding RNAs in Sepsis-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction.

Front Cardiovasc Med, 8:684348, 10 May 2021

Cited by: 7 articles | PMID: 34041287 | PMCID: PMC8141560

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

GEO - Gene Expression Omnibus (2)

- (1 citation) GEO - GSE31210

- (1 citation) GEO - GSE19804

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

The crosstalk between lncRNAs and the Hippo signalling pathway in cancer progression.

Cell Prolif, 53(9):e12887, 10 Aug 2020

Cited by: 29 articles | PMID: 32779318 | PMCID: PMC7507458

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Relationship between long non-coding RNAs and Hippo signaling pathway in gastrointestinal cancers; molecular mechanisms and clinical significance.

Heliyon, 10(1):e23826, 22 Dec 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38226210 | PMCID: PMC10788524

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Regulation of mTOR signaling by long non-coding RNA.

Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech, 1863(4):194449, 18 Nov 2019

Cited by: 12 articles | PMID: 31751821 | PMCID: PMC7125019

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

The regulatory roles of long noncoding RNAs in the biological behavior of pancreatic cancer.

Saudi J Gastroenterol, 25(3):145-151, 01 May 2019

Cited by: 20 articles | PMID: 30720003 | PMCID: PMC6526735

Review Free full text in Europe PMC