Abstract

Background

Genital powder use is more common among African-American women; however, studies of genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk have been conducted predominantly in White populations, and histotype-specific analyses among African-American populations are limited.Methods

We used data from five studies in the Ovarian Cancer in Women of African Ancestry consortium. Participants included 620 African-American cases, 1,146 African-American controls, 2,800 White cases, and 6,735 White controls who answered questions on genital powder use prior to 2014. The association between genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk by race was estimated using logistic regression.Results

The prevalence of ever genital powder use for cases was 35.8% among African-American women and 29.5% among White women. Ever use of genital powder was associated with higher odds of ovarian cancer among African-American women [OR = 1.22; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.97-1.53] and White women (OR = 1.36; 95% CI = 1.19-1.57). In African-American women, the positive association with risk was more pronounced among high-grade serous tumors (OR = 1.31; 95% CI = 1.01-1.71) than with all other histotypes (OR = 1.05; 95% CI = 0.75-1.47). In White women, a significant association was observed irrespective of histotype (OR = 1.33; 95% CI = 1.12-1.56 and OR = 1.38; 95% CI = 1.15-1.66, respectively).Conclusions

While genital powder use was more prevalent among African-American women, the associations between genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk were similar across race and did not materially vary by histotype.Impact

This is one of the largest studies to date to compare the associations between genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk, overall and by histotype, between African-American and White women.Free full text

Genital powder use and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in the Ovarian Cancer in Women of African Ancestry Consortium

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Genital powder use is more common among African-American women; however, studies of genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk have been conducted predominantly in White populations, and histotype-specific analyses among African-American populations are limited.

METHODS:

We used data from five studies in the Ovarian Cancer in Women of African Ancestry consortium. Participants included 620 African-American cases, 1,146 African-American controls, 2,800 White cases, and 6,735 White controls who answered questions on genital powder use prior to 2014. The association between genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk by race was estimated using logistic regression.

RESULTS:

The prevalence of ever genital powder use for cases was 35.8% among African-American women and 29.5% among White women. Ever use of genital powder was associated with higher odds of ovarian cancer among African-American women (odds ratio [OR]=1.22; 95% CI=0.97–1.53. and White women (OR=1.36; 95% CI=1.19–1.57). In African-American women the positive association with risk was more pronounced among high-grade serous tumors (OR=1.31; 95% CI=1.01–1.71) than with all other histotypes (OR=1.05; 95% CI=0.75–1.47). In White women, a significant association was observed irrespective of histotype (OR=1.33; 95% CI=1.12–1.56 and OR=1.38; 95% CI=1.15–1.66, respectively).

CONCLUSION:

While genital powder use was more prevalent among African-American women, the associations between genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk were similar across race and did not materially vary by histotype.

IMPACT:

This is the one of the largest studies to date to compare the associations between genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk, overall and by histotype, between African-American and White women.

Introduction

The use of body powder in the genital area is a relatively common feminine hygienic practice (1). Women usually report genital powder use in the form of baby or feminine powder for cleanliness, freshness, and dryness of the genital region (1,2). Talc is a common ingredient in many genital powders (3) and has been suggested to play a role in ovarian cancer development (4–6), although uncertainty about this association still exists (7). Beginning in 2014, several lawsuits were filed against companies with talc products on behalf of women with ovarian cancer (8). Use of genital powder use is more common among African-American (AA) women than White women (9), but previous studies of genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk have been primarily been conducted in White populations.

The study with the largest number of AA ovarian cancer cases to examine the association with genital powder use was a pooled analysis which combined the African American Cancer Epidemiology Study (AACES) with 7 case-control studies from the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium (OCAC) with information on genital powder use (10). However, this study examined heterogeneity across all racial groups (i.e. was not focused on comparing AA and White women) and did not examine associations by frequency or duration of genital powder use. Further, five of the eight studies had 24 AA cases or fewer, limiting the ability to assess study heterogeneity specific to AA study participants. The largest study focused on AA women to-date, AACES, reported a significant association between genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk but was limited in power to examine associations by histotype and by frequency and duration of use (11). However, AACES primary analyses included cases diagnosed after 2013 increasing the potential for recall bias in relation to genital powder use.

Thus, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the association between genital powder use and epithelial ovarian cancer risk among AA and White women in the Ovarian Cancer in Women of African Ancestry (OCWAA) consortium overall, by histotype, and examining frequency and duration. These analyses improves on prior studies due to OCWAAs inclusion of studies with at least 40 AA cases which provides the ability to assess heterogeneity across studies (12) while its exclusion of cases diagnosed after 2013 lessens the potential impact of recall bias (8).

Methods

Study Population.

The Ovarian Cancer in Women of African Ancestry (OCWAA) consortium was established with the objective to understand racial differences as they relate to risk factors and outcomes in epithelial ovarian cancer (12). The OCWAA consortium has been previously described (12). In this analysis, we included the five of the eight OCWAA studies that collected data on body powder use. This included four population-based case-control studies (the North Carolina Ovarian Cancer Study [NCOCS], Los Angeles County Ovarian Cancer Study [LACOCS], Cook County Case Study [CCCS], and African American Cancer Epidemiology Study [AACES]), and a nested case-control study within the WHI Observational Study. Controls within four case-controls studies were matched by age and race, with additional matching for ZIP code and geographic residential region for LACOCS and AACES. Six controls were matched for each case in WHI’s nested case-control study based on the following: race, age of diagnosis, and last questionnaire completed before ovarian cancer diagnosis. All OCWAA studies classified race based on self-report. Participants in OCWAA are of non-Hispanic and Hispanic ethnicity. 0.6% of AA participants and 1.5% of White participants are Hispanic (12).

Eligibility for this analyses was restricted to interview year prior to 2014 for case-control studies to reduce recall bias following the class action lawsuits that were filed in 2014 (11).

Tumor characteristics.

Data on cancer diagnoses were abstracted from medical records and cancer registry reports. Only epithelial ovarian cancer cases defined using International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Version 3, were eligible for inclusion. Tumor histotype was determined by combining morphology and grade information that represented the diagnostic guidelines for ovarian carcinomas in 2014 from the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of Female Reproductive Organs (13).

Exposure assessment.

Each study collected data from participants on genital powder use via standardized questionnaires that were either interviewer-administered or self-administered. Harmonized variables of interest were created by comparing questionnaires between the participating studies. Genital powder was defined as any type of powder (baby, talc, deodorizing, cornstarch, or unspecified/unknown) applied directly to the genital, perineal, or rectal area or applied indirectly by sanitary pads, tampons, or underwear. Ever use and duration of genital powder use was assessed in all studies while frequency of use was assessed in four studies (Table 1). The wording of questions assessing lifetime (or adult) genital powder use varied across studies and is detailed in Table 1. Frequency of genital powder use was categorized as no use, ≤once per week, and >once per week. Duration of genital powder use was categorized as no use, <20 years, and ≥20 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in genital body powder use and epithelial ovarian cancer analyses

| Ever use of genital powder | Frequent genital powder use (>once per week) | Long-term genital powder use (>20 years) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Diagnosis years | Exposed Cases and Controls, (% exposed) | Exposure assessment | Exposed Cases and Controls, (% exposed) | Exposure assessment | Exposed Cases and Controls, (% exposed) | Exposure assessment | |||

| AA | White | AA | White | AA | White | |||||

| AACES | 2010–2015 | 119 (37.8%) cases, 202 (33.9%) controls | Have you ever used cornstarch, talc, baby or deodorizing powders in any of the following ways: On your genital or rectal areas, including on your underwear or sanitary napkins, or on birth control devices like diaphragms or cervical caps. Yes, No, NA | 107 (34.0%) cases, 183 (30.7%) controls | How many times per month did you use it? __ __ | 50 (16.3%) cases, 94 (16.2%) controls | How many years total did you use it? __ __ | |||

| CCCCS | 1994–1998 | 14 (31.8%) cases, 15 (18.8%) controls | 53 (22.7%) cases, 75 (17.8%) controls | Have you ever applied powders to your genital area after bathing or at other times? (Genital area includes inner thighs.) Yes, No, Don’t know | 10 (22.7%) cases, 11 (13.8%) controls | 39 (16.7%) cases, 54 (12.8%) controls | How many times per day or per week did you use it at age (AGE)? __ per day __ per week __per month __per year | 4 (9.5%) cases, 6 (8.1%) controls | 15 (6.9%) cases, 7 (1.8%) controls | Age started using powders, age stopped using powders |

| LACOCS | 1998–2002 | 37 (29.1%) cases, 38 (26.2%) controls | 296 (25.1%) cases, 298 (16.5%) controls | Did you ever use talc, baby, or deodorizing powder as a dusting powder to the genital or rectal area? Yes, No | 30 (23.6%) cases, 33 (22.8%) controls | 248 (21.0%) cases, 251 (13.9%) controls | As a dusting powder to the genital or rectal area? Times per month __ _ | 20 (16.0%) cases, 16 (11.2%) controls | 145 (12.4%) cases, 123 (6.9%) controls | As a dusting powder to the genital or rectal area? Years used __ __ |

| NCOCS | 1999–2003 | 40 (30.8%) cases, 57 (29.8%) controls | 220 (27.1%) cases, 200 (23.3%) controls | Please tell me if you used cornstarch, talc, baby or deodorizing powder in any of the following ways: directly to your genital or rectal areas. Yes, No, Don’t know | 35 (30.4%) cases, 45 (23.6%) controls | 181 (22.3%) cases, 170 (19.8%) controls | How often on average did you use it? __days / week | 20 (18.2%) cases, 21 (11.5%) controls | 83 (10.6%) cases, 88 (10.6%) controls | For how long in total did you use this product regularly? __ __years |

| WHI | 1994–2018 | 12 (63.2%) cases, 78 (58.2%) controls | 256 (44.5%) cases, 1515 (41.5%) controls | Have you ever used body powder on your private parts (genital areas)? Yes, No | NA | NA | Frequency of use was not assessed in WHI | 5 (26.3%) cases, 27 (20.2%) controls | 90 (15.7%) cases, 542 (14.9%) controls | For how many years? _____ [use on genital areas, use on sanitary napkin/pad, and use on diaphragm asked separately] |

Covariates.

Demographic, reproductive history, lifestyle, and medical history data were collected from all participating studies. We considered the following known or putative risk factors for inclusion in the regression models: age (continuous), education (high school graduate/GED or less, some college, college graduate, graduate/professional school), duration of oral contraceptive use in months (continuous), family history of breast cancer (yes, no), family history of ovarian cancer (yes, no), tubal ligation (yes, no), number of full term pregnancies (≥ 6 months, continuous), menopausal status (premenopausal, postmenopausal) hysterectomy (yes, no), interview year (continuous), body mass index (BMI in kg/m2) (<25.0, 25.0–29.9, 30.0–34.9, ≥35.0), smoking status (ever smoker, never smoker), and study site (AACES, CCCS, NCOCS, LACOCS, WHI). Patency of the reproductive track was defined as not having had a hysterectomy and no tubal ligation (yes, no).

Statistical Analysis.

Race and study-specific odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were combined using a multi-level random-effects meta-analysis (14–16). Study heterogeneity was assessed by testing the variance of a site x powder interaction random effects term using 95% profile likelihood confidence intervals and tests of variance components. As no significant heterogeneity by study was detected random effects were removed from the model and data from the individual studies was pooled. The association between each genital powder variable (ever use, frequency, and duration) and ovarian cancer risk was estimated using logistic regression models. To investigate potential histotype-specific associations, analyses were stratified by high-grade serous carcinoma (HGS) vs all other histotypes. Tests for linear trend across categories of frequency and duration were performed by assigning the median value to all participants in that group and including as a continuous variable in the regression models. Heterogeneity in the association between genital powder use and ovarian cancer by race and patency was assessed with a likelihood ratio test comparing models with both the main effects and the interaction term to a model with the main effects only.

The population attributable risk (PAR) for ever use of genital powder overall and by race was estimated using the Bruzzi method (17). Details of the analytic methods used for PAR calculation in OCWAA have been described in detail previously (18). Study site interactions with age were included in the PAR% analysis for AA women and study site interactions with BMI, nulliparity, education, and oral contraceptive use were included for White women. In this analyses, the PAR describes the proportion of cases in the population that would not have occurred if the exposure (i.e. genital powder use) was not present, but it does not provide an estimate of the probability of causation. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and R (version 3.6.0, The R Foundation of Statistical Computing).

Results

This analysis included 3,420 cases and 7,881 controls (620 AA cases, 1146 AA controls, 2800 White cases, and 6735 White controls). AA women were more likely to have had a hysterectomy or tubal ligation and to have ever used oral contraceptives compared to White women while White women were more likely to be nulliparous (Table 2). Across most study sites, AA cases and controls had higher prevalence of ever use, frequent use, and long-term use of genital powder than White cases and controls (Table 1). Relative to other studies, WHI participants, were most likely to report ever use of genital powder (cases = 44.5% White, 63.2% AA; controls = 41.5% White, 58.2% AA) and to report more than 20 years of powder use (cases=15.7% White, 26.3% AA; controls =14.9% Whites, 20.2% AA). AACES participants reported the highest frequency of powder use with 34.0% of cases and 30.7% of controls reporting powder use more than once per week. Among all cases, a higher percentage of AA cases ever used genital powder in comparison to White cases (35.8% vs. 29.5%); a similar pattern observed among controls (34.0% of AA controls vs. 31.0% of White controls, respectively) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of OCWAA study participants by race and case status

| African American | White | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics, Mean (SD) or N (%)a | Controls (N=1146) | Cases (N=620) | Controls (N=6735) | Cases (N=2800) |

| Age, years | 55.4 (12.9) | 57.1 (10.9) | 64.7 (12.8) | 61.2 (11.8) |

| Education | ||||

High school graduate/GED or less High school graduate/GED or less | 422 (36.9) | 264 (42.6) | 1182 (17.6) | 590 (21.1) |

Some college Some college | 310 (27.1) | 162 (26.1) | 1922 (28.6) | 752 (26.9) |

College graduate College graduate | 244 (21.3) | 124 (20.0) | 1328 (19.8) | 670 (24.0) |

Graduate school Graduate school | 168 (14.7) | 70 (11.3) | 2285 (34.0) | 785 (28.1) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | ||||

<25.0 <25.0 | 264 (23.0) | 118 (19.0) | 3265 (48.5) | 1458 (52.1) |

25.0–29.9 25.0–29.9 | 341 (30.0) | 173 (27.9) | 2039 (30.3) | 744 (26.6) |

30.0–34.9 30.0–34.9 | 254 (22.2) | 157 (25.3) | 892 (13.2) | 371 (13.3) |

≥35.0 ≥35.0 | 287 (25.0) | 172 (27.7) | 539 (8.0) | 227 (8.1) |

| Tubal Ligation | ||||

No No | 714 (62.4) | 421 (68.1) | 5477 (81.5) | 2371 (84.7) |

Yes Yes | 430 (37.6) | 197 (31.9) | 1241 (18.5) | 427 (15.3) |

| Duration of oral contraceptive use (months) | 49.7 (68.5) | 40.5 (62.7) | 39.0 (62.4) | 33.1 (54.9) |

| Oral Contraceptive use | ||||

Never Never | 340 (29.7) | 226 (36.5) | 3361 (49.9) | 1297 (46.4) |

Ever Ever | 805 (70.3) | 394 (63.6) | 3372 (50.1) | 1501 (53.3) |

| Hysterectomy | ||||

No No | 907 (79.8) | 465 (75.6) | 5708 (85.9) | 2255 (81.1) |

Yes Yes | 230 (20.2) | 150 (24.4) | 937 (14.1) | 527 (18.9) |

| Full term pregnancies | 2.4 (1.8) | 2.4 (1.9) | 2.3 (1.7) | 1.9 (1.6) |

| Nulliparity | ||||

No No | 961 (84.0) | 506 (81.6) | 5395 (80.3) | 2098 (75.0) |

Yes Yes | 183 (16.0) | 114 (18.4) | 1323 (19.7) | 701 (25.0) |

| Patency | ||||

No No | 572 (49.9) | 311 (50.2) | 2112 (31.4) | 903 (32.2) |

Yes Yes | 574 (50.1) | 309 (49.8) | 4623 (68.6) | 1897 (67.8) |

| Menopausal Status | ||||

Premenopausal Premenopausal | 392 (34.2) | 170 (27.4) | 1133 (16.8) | 560 (20.0) |

Postmenopausal Postmenopausal | 753 (65.8) | 450 (72.6) | 5595 (83.2) | 2239 (80.0) |

| Family History of Breast Cancer | ||||

No No | 1001 (87.4) | 490 (79.0) | 5786 (85.9) | 2326 (83.1) |

Yes Yes | 145 (12.6) | 130 (21.0) | 949 (14.1) | 474 (16.9) |

| Family History of Ovarian Cancer | ||||

No No | 1115(97.3) | 581 (93.7) | 6592 (97.9) | 2674 (95.5) |

Yes Yes | 31 (2.7) | 39 (6.3) | 143 (2.1) | 126 (4.5) |

| Cigarette Smoking | ||||

Never Never | 627 (54.8) | 319 (51.5) | 3415 (50.8) | 1414 (50.5) |

Ever Ever | 518 (45.2) | 301 (48.5) | 3303 (49.2) | 1385 (49.5) |

| Sites | ||||

AACES AACES | 596 (52.0) | 315 (50.8) | NA | NA |

CCCS CCCS | 80 (7.0) | 44 (7.1) | 421 (6.3) | 233 (8.3) |

NCOCS NCOCS | 191(16.7) | 115 (18.6) | 859 (12.8) | 812 (29.0) |

LACOCS LACOCS | 145 (12.7) | 127 (20.5) | 1806 (26.8) | 1180 (42.1) |

WHI WHI | 134 (11.6) | 19 (3.1) | 3649 (54.2) | 575 (20.5) |

| Histotype | ||||

High grade serous High grade serous | 402 (65.1) | 1707 (61.5) | ||

Low grade serous Low grade serous | 22 (3.6) | 91 (3.3) | ||

Endometrioid Endometrioid | 51 (8.3) | 209 (7.5) | ||

Clear Cell Clear Cell | 23 (3.7) | 206 (7.4) | ||

Mucinous Mucinous | 40 (6.5) | 150 (5.4) | ||

Others Others | 80 (12.9) | 411 (14.8) | ||

Table 3.

Odds ratios and 95% CIs for the association between ever use of genital powder overall and by race, stratified by histotype

| All cases | High-grade serous | All other histotypes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever use of body powder in genital areas | Controls (%) | Cases (%) | MVa

OR (95% CI)b | Cases (%) | MVa

OR (95% CI)b | Cases (%) | MVa

OR (95% CI)b |

| All participants | |||||||

| No | 5403 (68.6) | 2373 (69.4) | 1.00 | 1451 (68.8) | 1.00 | 900 (70.2) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 2478 (31.4) | 1047 (30.6) | 1.32 (1.17–1.48) | 658 (31.2) | 1.32 (1.15–1.51) | 383 (29.8) | 1.29 (1.10–1.52) |

| African Americans | |||||||

| No | 756 (66.0) | 398 (64.2) | 1.00 | 255 (63.4) | 1.00 | 141 (65.3) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 390 (34.0) | 222 (35.8) | 1.22 (0.97–1.53) | 147 (36.6) | 1.31 (1.01–1.71) | 75 (34.7) | 1.05 (0.75–1.47) |

| Whites | |||||||

| No | 4647 (69.0) | 1975 (70.5) | 1.00 | 1196 (70.1) | 1.00 | 759 (71.1) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 2088 (31.0) | 825 (29.5) | 1.36 (1.19–1.57) | 511 (29.9) | 1.33 (1.12–1.56) | 308 (28.9) | 1.38 (1.15–1.66) |

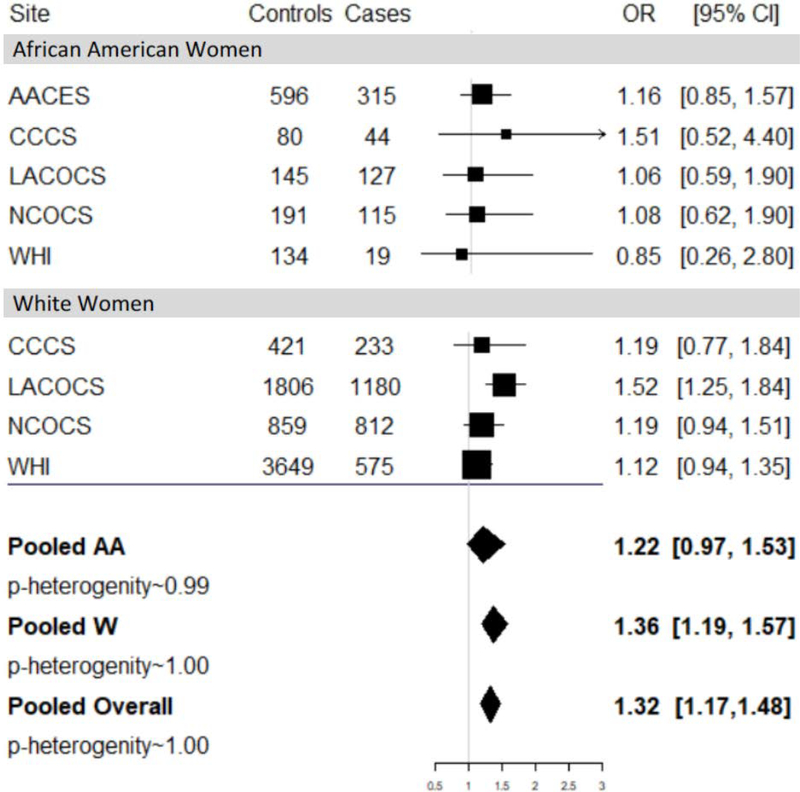

Ever use of genital powder was associated with 32% higher risk of ovarian cancer among all women (pooled OR=1.32; 95% CI=1.17–1.48). When stratified by race, there was a 36% higher risk of ovarian cancer among White women (pooled OR=1.36; 95% CI=1.19–1.57) and a non-significant higher risk among AA women (pooled OR=1.22; 95% CI=0.97–1.53) (Figure 1; Table 3). No evidence of heterogeneity by race was observed (p=0.33). When restricted to women with patent reproductive tracts the OR among all women was 1.27 (95% CI=1.09–1.48). Among women without patent reproductive tracts the corresponding OR was 1.42 (95% CI=1.17–1.72) (phetereogeneity=0.31). When stratified by race the OR among women with patent reproductive tracks was 1.22 (95% CI=0.88–1.69) for AA women and 1.28 (95% CI=1.08–1.52) for White women.

Genital powder use in relation to risk of epithelial ovarian cancer among five studies stratified by race. All models are adjusted for age (continuous), education(high school graduate/GED or less, some college, college graduate, graduate/professional school), duration of oral contraceptive use in months (continuous), family history of breast cancer (yes, no), family history of ovarian cancer (yes, no), tubal ligation (yes, no), full term pregnancies (≥6 months, continuous), hysterectomy (yes, no), interview year (continuous), BMI (<25.0, 25.0–29.9, 30.0–34.9, ≥35.0 kg/m2), menopausal status (premenopausal, postmenopausal), and smoking (ever, never).

In terms of histotype, both AA and White women who ever used powder in the genital area were at a higher risk for high-grade serous ovarian cancer (AA women OR=1.31; 95% CI=1.01–1.71, White women OR=1.33; 95% CI=1.12–1.56). A similar association was observed for all other histotypes combined among White women (OR=1.38; 95% CI=1.15–1.66) while among AA women, no association was observed among all other histotypes (OR=1.05; 95% CI=0.75–1.47) (Table 3).

No difference in the association was observed by frequency of genital powder use (≤ once per week OR=1.34; 95% CI=1.01–1.79 and more than once per week OR=1.31; 95% CI=1.15–1.48; ptrend=0.98). When frequency was examined by race a similar pattern was observed. AA women who used genital powder ≤ once per week (OR=1.23; 95% CI=0.68–2.21) and more than once per week (OR=1.22; 95% CI=0.96–1.55) had a higher risk of ovarian cancer compared to never users, although neither association was statistically significant (ptrend=0.85) (Table 4). Similarly, White women who used genital powder ≤ once per week (OR=1.40; 95% CI=1.00–1.96) and more than once per week (OR=1.34; 95% CI=1.16–1.56) had a higher risk of ovarian cancer compared to never users (ptrend=0.90).

Table 4.

Odds ratios and 95% CIs for the association between frequency of genital powder use and ovarian cancer, overall and by race, stratified by histotype

| All cases | High-grade serous | All other histotypes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of usea | Controls (%) | Cases (%) | MVb

OR (95% CI)c | Cases (%) | MVb OR (95% CI)c | Cases (%) | MVb OR (95% CI)c |

| All participants | |||||||

| No genital use | 3213 (78.4) | 2047 (72.5) | 1.00 | 1229 (72.3) | 1.00 | 796 (72.6) | 1.00 |

| ≤ once per week | 117 (2.9) | 103 (3.7) | 1.34 (1.01–1.79) | 65 (3.8) | 1.34 (0.95–1.87) | 37 (3.4) | 1.29 (0.87–1.92) |

| > once per week | 747 (18.2) | 650 (23.0) | 1.31 (1.15–1.48) | 389 (22.9) | 1.31 (1.13–1.52) | 257 (23.5) | 1.29 (1.09–1.54) |

| ptrendd | 0.98 | 0.88 | 0.79 | ||||

| African Americans | |||||||

| No genital use | 700 (69.5) | 391 (65.6) | 1.00 | 249 (64.7) | 1.00 | 140 (67.0) | 1.00 |

| ≤ once per week | 35 (3.5) | 23 (3.9) | 1.23 (0.68–2.21) | 14 (3.6) | 1.18 (0.59–2.36) | 09 (4.3) | 1.21 (0.64–3.07) |

| > once per week | 272 (27.0) | 182 (30.5) | 1.22 (0.96–1.55) | 122 (31.7) | 1.34 (1.02–1.76) | 60 (28.7) | 1.02 (0.71–1.45) |

| ptrendd | 0.85 | 0.68 | 0.77 | ||||

| Whites | |||||||

| No genital use | 2513 (81.9) | 1656 (75.1) | 1.00 | 980 (75.5) | 1.00 | 656 (74.5) | 1.00 |

| ≤ once per week | 82 (2.7) | 80 (3.6) | 1.40 (1.00–1.96) | 51 (3.9) | 1.42 (1.00–2.12) | 28 (3.2) | 1.32 (0.84–2.08) |

| > once per week | 475 (15.5) | 468 (21.2) | 1.34 (1.16–1.56) | 267 (20.6) | 1.29 (1.08–1.54) | 197 (22.4) | 1.40 (1.15–1.71) |

| ptrendd | 0.90 | 0.68 | 0.66 | ||||

No dose-response trends was observed for duration of genital powder use overall or when stratified by race. Among all women the OR for long-term use (>20 years) was 1.28 (95% CI=1.08–1.51) and the OR for ≤20 years was 1.43 (95% CI=1.22–1.68) (ptrend=0.97). When duration of use was examined among AA women, those who used genital powder for ≤20 years had a higher risk of ovarian cancer (OR=1.44; 95% CI=1.06–1.95) compared to never users, while no association was observed among those using powder for more than 20 years (OR=1.06; 95% CI: 0.78–1.44) (ptrend=0.19) (Table 5). There was a similar risk of ovarian cancer among White women regardless of duration of use, with an OR of 1.42 (95% CI=1.17–1.71) for those who used genital powder for ≤20 years and 1.40 (95% CI=1.14–1.72) for long-term use (ptrend=0.33). Results for frequency and duration were similar when stratified by histotype (Tables 4 and and55).

Table 5.

Odds ratios and 95% CIs for the association between duration of genital powder use and ovarian cancer, overall and by race, stratified by histotype

| All cases | High-grade serous | All other histotypes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of usea | Controls (%) | Cases (%) | MVb OR (95% CI)c | Cases (%) | MVb OR (95% CI)c | Cases (%) | MVb OR (95% CI)c |

| All participants | |||||||

| No genital use | 5403 (69.5) | 2374 (71.1) | 1.00 | 1452 (70.4) | 1.00 | 900 (72.1) | 1.00 |

| ≤20 years | 1443 (18.6) | 534 (16.0) | 1.43 (1.22–1.68) | 334 (16.2) | 1.42 (1.17–1.71) | 198 (15.9) | 1.44 (1.16–1.78) |

| >20 years | 924 (11.9) | 483 (12.9) | 1.28 (1.08–1.51) | 277 (13.4) | 1.32 (1.09–1.60) | 151 (12.1) | 1.19 (0.94–1.50) |

| ptrendd | 0.97 | 0.71 | 0.58 | ||||

| African Americans | |||||||

| No genital use | 756 (67.7) | 398 (66.0) | 1.00 | 255 (65.2) | 1.00 | 141 (67.1) | 1.00 |

| ≤20 years | 196 (17.6) | 106 (17.6) | 1.44 (1.06–1.95) | 67 (17.1) | 1.53 (1.07–2.18) | 39 (18.6) | 1.29 (0.83–2.00) |

| >20 years | 164 (14.7) | 99 (16.4) | 1.06 (0.78–1.44) | 69 (17.7) | 1.19 (0.84–1.69) | 30 (14.3) | 0.83 (0.52–1.34) |

| ptrendd | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0.28 | ||||

| Whites | |||||||

| No genital use | 4647 (69.8) | 1976 (72.2) | 1.00 | 1197 (71.6) | 1.00 | 759 (73.1) | 1.00 |

| ≤20 years | 1247 (18.7) | 428 (15.6) | 1.42 (1.17–1.71) | 267 (16.0) | 1.35 (1.08–1.69) | 159 (15.3) | 1.47 (1.15–1.88) |

| >20 years | 760 (11.4) | 333 (12.2) | 1.40 (1.14–1.72) | 208 (12.4) | 1.40 (1.11–1.77) | 121 (11.7) | 1.36 (1.03–1.80) |

| ptrendd | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.83 | ||||

The PARs for ever use of genital body powder were similar between AA women (7.5%; 95% CI= 6.5%−8.5% and White women (6.2%; 95% CI=5.4%−6.9%). The PAR when AA and White women were combined was 6.4% (95% CI=2.2%−10.0%).

Discussion

In this study, ever use of genital body powder was associated with higher odds of ovarian cancer in both AA and White women and the population attributable risk was similar in the two groups. Use of genital body powder was more strongly associated with the risk of high-grade serous cancer than with non high-grade serous cancer in AA women, while a positive association was observed irrespective of histotype in White women. There was not a dose-response relationship regarding frequency or duration of genital powder use and ovarian cancer among AA or White women.

Most prior observational research examining genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk has been conducted in predominantly White populations and very few studies have compared effect estimates for genital powder use by race (10). Cramer et al., examined the association between genital talc use and ovarian cancer in a population-based case-control study, including analyses stratified by race (19). In this study, the odds of ovarian cancer were higher for AA women than for any other race (OR=5.08; 95% CI=1.32–19.6). The corresponding OR for White women was 1.35 (95% CI=1.17–1.55) and a significant interaction was observed by race (pinteraction=0.002). It is important to note that the findings among AA women were based on small numbers (35 AA cases and 23 AA controls). Peres et. al. pooled data from AACES and 11 other case-control studies in the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium to evaluate racial/ethnic differences in multiple epidemiological factors, including genital body powder use, and epithelial ovarian cancer risk (10). Among the 8 case-control studies with information on genital powder use, AA (OR=1.62; 95% CI=1.32–2.00), Non-Hispanic White (OR=1.30; 95% CI=1.20–1.41), and Hispanic (OR=1.41; 95% CI=0.93–2.13) women who used genital powder had a higher odds of ovarian cancer compared to those who did not use genital powder (10). Asian/Pacific Islanders who used genital powder had a similar odds of ovarian cancer compared to never users (OR=1.02; 95% CI=0.61–0.70). This analysis included predominantly Non-Hispanic White study populations (cases=5,149 and controls=10,256) in comparison to only 698 AA cases and 872 AA controls (10). A limitation of this study was that study heterogeneity could only be assessed for Non-Hispanic Whites due to low numbers of other racial groups in some studies. This is in contrast to OCWAA studies which require a minimum number of AA cases in each study in order to provide the ability to assess heterogeneity across studies (12).

LACOCS and NCOCS, studies included in the current OCWAA consortium analysis, reported an increased risk of ovarian cancer among AA talc users compared to White talc users. In LACOCS, use of talc for one year or more compared to less than one year/no talc use was associated with higher, and similar, odds of ovarian cancer among all racial/ethnic groups; Non-Hispanic White women (OR=1.41; 95% CI=1.41–1.67), Hispanic women (OR=1.77; 95% CI=1.20–2.62), and AA women (OR=1.56; 95% CI=0.80–3.04) (9). The reference group in this analysis included both never use of talc and less than one year which differs from our reference group of never use. In NCOCS, AA women who reported talc use had a higher risk of ovarian cancer (OR=1.19; 95% CI=0.68–2.09) than those who did not, while no association was observed among White women (OR=1.04; 95% CI=0.82–1.33) (20). The current OCWAA analyses included additional NCOCS cases not included in the 2009 analysis.

To our knowledge, AACES is the largest individual case-control study of AA women to examine the association between genital powder use and ovarian cancer with 584 cases and 745 controls (11). In AACES, women who ever used genital powder had a 44% higher risk of ovarian cancer (OR=1.44; 95% CI=1.11–1.86) compared to those who did not report any powder use. When the time period was limited to women who were interviewed prior to 2014, (i.e., before ongoing lawsuits about genital powder use which had extensive media coverage) the results were attenuated and no longer significant (OR=1.19; 95% CI=0.87–1.63). In contrast, a significant positive association was observed among those interviewed after 2014 (OR= 2.91; 95% CI=1.70–4.97) (11). These results highlight the potential for recall bias in case-control studies, especially those conducted after 2013(8). AACES was included in our current analyses with the restriction of cases and controls to those interviewed prior to 2014 in order to avoid possible reporting bias resulting from lawsuits beginning in 2014.

In regards to cohort studies, which are not impacted by recall bias, there have been very few prospective evaluations on genital powder use and ovarian cancer and to our knowledge only one prospective analyses by O’Brien et al, which included four cohort studies, has presented results by race comparing Non-Hispanic White women (n=2061) to women of all other race/ethnicities (n=107) (4).Our study, which included both prospective data from a case-control study nested within the WHI prospective cohort (which was included in the O’Brien study) and retrospective case-control studies restricted to interviews prior to 2014, identified a positive association of borderline significance between genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk among AA women (OR=1.22; 95% CI=0.97–1.53) and a larger significant positive association among White women (OR=1.37; 95% CI=1.19–1.57). This differs from the previous three case-control studies in which AA women who used genital powder had a suggestively higher odds of ovarian cancer compared to White women who used genital powder (9,19,20). However, only Cramer et al., observed a statistically significant interaction by race (19) and in all three studies the confidence intervals between the ORs for AA and White women overlapped.

To our knowledge this is only the second study to examine the association between frequency and duration of genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk among AA women. We observed no clear dose-response trends for frequency or duration of genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk among AA women or White women. In contrast, AACES reported significant trends for both frequency (less than 30 times per month, daily use) and duration (<20 years, ≥ 20 years) of genital powder use (ptrend<0.01, ptrend=0.02), respectively.(11). While different than AACES, our results are consistent with most prior studies that report no significant dose-response association between genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk (5,21–25). AACES cases diagnosed after 2014 were not excluded in the frequency and duration analysis which may explain the difference in ORs between our studies. We did not conduct an analysis that addressed both duration and frequency of application. Some women may use body powder products on a non-daily basis; therefore, the best measure of dose may be the number of applications based on frequency of applications x years of use. However, this measure was not available for most OCWAA studies.

Very few studies have examined the PAR for genital body powder use and ovarian cancer by race. PARs were calculated across four ovarian cancer case-control studies in Los Angeles county for talc use with estimates of 13.0% among non-Hispanic whites (95% CI=8.7%−16.8%) and 15.1% among African Americans (95% CI=10.0%−19.5%) (9). The PARs observed in our study were lower but both studies suggest that differences in ovarian cancer risk between AA and White women are not driven by genital powder use.

The few previous studies that examined genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk among AA women have had limited power to examine the association by histotype, with most prior publications with fewer than 150 total cases among AA women (9,20,26–28). In AACES, genital powder use was significantly associated with serous (OR=1.38; 95% CI=1.03–1.85) and non-serous ovarian cancer (OR= 1.63; 95% CI=1.04–2.55) when compared to never users (11). In our study, genital powder use was associated with risk of both high-grade serous and non-high-grade serous ovarian cancer among White women, while genital powder use was only associated with only high-grade serous among AA women; however given the wide confidence intervals this result should be cautiously interpreted. Previous meta-analyses reported that genital powder use is associated with increased risk of serous and endometrioid histotypes, but not with mucinous (5). Unfortunately, even with our consortium approach, since only five of eight OCWAA studies collected information on genital powder use we did not have adequate power to examine associations by individual histotype except for high-grade serous.

Limitations of our study must be considered. Recall bias was not a concern for the cases and controls included in our study from the prospective study (WHI). However, for case-control studies, recall bias can be a concern for some exposures (8). This is particularly true for genital powder use with the advent of talc related lawsuits in 2014. All our analyses excluded interviews from case-control studies after 2014 in order to address this issue of recall bias. Genital body powder use was self-reported in each of the contributing OCWAA studies. It is possible that there were systematic differences in the way participants remember or report genital body powder and there were differences in the wording of the genital powder questions in the various studies. However, the definition of genital body powder exposure was the same for cases and controls in each of the individual OCWAA studies and we did not observe heterogeneity across studies in the effect estimates, highlighting that the results from our included prospective study (WHI) were not materially different from the 4 retrospective case-control studies. It is likely that with the exclusion of interviews conducted in 2014 and later, any misclassification would be non-differential with respect to the outcome, resulting in bias towards the null.

Strengths of our study include the large number of AA women made possible through the OCWAA consortium, which provided greater statistical power than any previous study to examine associations among AA women, both overall and by histotype and frequency and duration of genital powder use, and the ability to evaluate study heterogeneity. In addition, harmonization of the covariates across the included studies allowed for consistent adjustment for potential confounders.

In conclusion, in this consortium analysis of AA and White women, while the prevalence of ever genital body powder use was higher among AA women in the OCWAA consortium, the association between genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk was similar among AA and White women. Further, there was not a dose-response relationship between frequency or duration of genital powder use and ovarian cancer risk or any significant differences in association by histotype.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This study is supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01-CA207260 to Schildkraut and Rosenberg and K01-CA212056 to Bethea). AACES was funded by NCI (R01-CA142081 to Schildkraut); BWHS is funded by NIH (R01-CA058420, UM1-CA164974, and U01-CA164974 to Rosenberg); CCCCS was funded by NIH/NCI (R01-CA61093 to Rosenblatt); LACOCS was funded by NCI (R01-CA17054 to Pike, R01-CA58598 to Goodman and Wu, and Cancer Center Core Grant P30-CA014089 to Henderson and Wu) and by the California Cancer Research Program (2II0200 to A. Wu); and NCOCS was funded by NCI (R01-CA076016 to Schildkraut). The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute through contracts HHSN268201600018C, HHSN268201600001C, HHSN268201600002C, HHSN268201600003C and HHSN268201600004C. Additional grants to support WHI inclusion in OCWAA include UM1-CA173642-05 (to Anderson), NHLBI-CSB-WH-2016-01-CM and NHLBI-75N92021D00002.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Disclosure Statement: Patricia Moorman has received compensation for work related to litigation in regard to talc and ovarian cancer. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement:

The consortium data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions, however the research team can perform statistical analyses for non-OCWAA investigators of approved research projects with financial support for the analytic activities performed by the research team.

References

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-21-0162

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://aacrjournals.org/cebp/article-pdf/30/9/1660/3100977/1660.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/108008746

Article citations

Intimate Care Products and Incidence of Hormone-Related Cancers: A Quantitative Bias Analysis.

J Clin Oncol, 42(22):2645-2659, 15 May 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38748950

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Genital powder use and risk of ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of 8,525 cases and 9,859 controls.

Cancer Prev Res (Phila), 6(8):811-821, 12 Jun 2013

Cited by: 48 articles | PMID: 23761272 | PMCID: PMC3766843

Association of Powder Use in the Genital Area With Risk of Ovarian Cancer.

JAMA, 323(1):49-59, 01 Jan 2020

Cited by: 21 articles | PMID: 31910280 | PMCID: PMC6990816

First- and second-degree family history of ovarian and breast cancer in relation to risk of invasive ovarian cancer in African American and white women.

Int J Cancer, 148(12):2964-2973, 17 Feb 2021

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 33521947 | PMCID: PMC8353974

Perineal exposure to talc and ovarian cancer risk.

Obstet Gynecol, 80(1):19-26, 01 Jul 1992

Cited by: 60 articles | PMID: 1603491

Review

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

CLC NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: 75N90021D00002

NCI NIH HHS (11)

Grant ID: P01 CA017054

Grant ID: R01 CA058598

Grant ID: UM1 CA173642

Grant ID: R01 CA142081

Grant ID: R01 CA207260

Grant ID: U01 CA164974

Grant ID: UM1 CA164974

Grant ID: R01 CA076016

Grant ID: K01 CA212056

Grant ID: P30 CA014089

Grant ID: R01 CA058420

NHLBI NIH HHS (6)

Grant ID: HHSN268201600001C

Grant ID: HHSN268201600018C

Grant ID: HHSN268201600004C

Grant ID: 75N92021D00002

Grant ID: HHSN268201600003C

Grant ID: HHSN268201600002C

NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: 75N98021D00002

NINR NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: 75N94021D00002

ORFDO NIH HHS (1)

Grant ID: 75N99021D00002