Abstract

Purpose

Donafenib, a novel multikinase inhibitor and a deuterated sorafenib derivative, has shown efficacy in phase Ia and Ib hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) studies. This study compared the efficacy and safety of donafenib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy for advanced HCC.Patients and methods

This open-label, randomized, parallel-controlled, multicenter phase II-III trial enrolled patients with unresectable or metastatic HCC, a Child-Pugh score ≤ 7, and no prior systemic therapy from 37 sites across China. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive oral donafenib (0.2 g) or sorafenib (0.4 g) twice daily until intolerable toxicity or disease progression. The primary end point was overall survival (OS), tested for noninferiority and superiority. Efficacy was primarily assessed in the full analysis set (FAS), and safety was assessed in all treated patients.Results

Between March 21, 2016, and April 16, 2018, 668 patients (intention-to-treat) were randomly assigned to donafenib and sorafenib treatment arms; the FAS included 328 and 331 patients, respectively. Median OS was significantly longer with donafenib than sorafenib treatment (FAS; 12.1 v 10.3 months; hazard ratio, 0.831; 95% CI, 0.699 to 0.988; P = .0245); donafenib also exhibited superior OS outcomes versus sorafenib in the intention-to-treat population. The median progression-free survival was 3.7 v 3.6 months (P = .0570). The objective response rate was 4.6% v 2.7% (P = .2448), and the disease control rate was 30.8% v 28.7% (FAS; P = .5532). Drug-related grade ≥ 3 adverse events occurred in significantly fewer patients receiving donafenib than sorafenib (125 [38%] v 165 [50%]; P = .0018).Conclusion

Donafenib showed superiority over sorafenib in improving OS and has favorable safety and tolerability in Chinese patients with advanced HCC, showing promise as a potential first-line monotherapy for these patients.Free full text

Donafenib Versus Sorafenib in First-Line Treatment of Unresectable or Metastatic Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Randomized, Open-Label, Parallel-Controlled Phase II-III Trial

PURPOSE

Donafenib, a novel multikinase inhibitor and a deuterated sorafenib derivative, has shown efficacy in phase Ia and Ib hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) studies. This study compared the efficacy and safety of donafenib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy for advanced HCC.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This open-label, randomized, parallel-controlled, multicenter phase II-III trial enrolled patients with unresectable or metastatic HCC, a Child-Pugh score ≤ 7, and no prior systemic therapy from 37 sites across China. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive oral donafenib (0.2 g) or sorafenib (0.4 g) twice daily until intolerable toxicity or disease progression. The primary end point was overall survival (OS), tested for noninferiority and superiority. Efficacy was primarily assessed in the full analysis set (FAS), and safety was assessed in all treated patients.

RESULTS

Between March 21, 2016, and April 16, 2018, 668 patients (intention-to-treat) were randomly assigned to donafenib and sorafenib treatment arms; the FAS included 328 and 331 patients, respectively. Median OS was significantly longer with donafenib than sorafenib treatment (FAS; 12.1 v 10.3 months; hazard ratio, 0.831; 95% CI, 0.699 to 0.988; P = .0245); donafenib also exhibited superior OS outcomes versus sorafenib in the intention-to-treat population. The median progression-free survival was 3.7 v 3.6 months (P = .0570). The objective response rate was 4.6% v 2.7% (P = .2448), and the disease control rate was 30.8% v 28.7% (FAS; P = .5532). Drug-related grade ≥ 3 adverse events occurred in significantly fewer patients receiving donafenib than sorafenib (125 [38%] v 165 [50%]; P = .0018).

CONCLUSION

Donafenib showed superiority over sorafenib in improving OS and has favorable safety and tolerability in Chinese patients with advanced HCC, showing promise as a potential first-line monotherapy for these patients.

INTRODUCTION

Liver cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide and in China.1,2 China has the highest global incidence, accounting for more than half of the new cases and deaths caused by liver cancer in the world.1,2 Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents 90% of liver malignancies.3 Most patients are diagnosed at the advanced stage with a median survival of 6-8 months.3 The diagnosis and treatment of HCC is a major public health concern in China.4

In comparison with their Western counterparts, Chinese patients with HCC tend to be younger, have advanced-stage disease, and predominantly hepatitis B virus (HBV)–positive, resulting in poor prognosis.5,6 At present, only sorafenib‐, lenvatinib‐, and oxaliplatin-based systemic chemotherapy have been approved in China as first-line systemic treatment for advanced HCC.7,8

Sorafenib was the first molecular targeted agent approved for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic HCC and remains the standard first-line therapy.3,9 However, sorafenib is associated with several limitations in clinical practice. Sorafenib demonstrated the median overall survival (mOS) of 10.7-14.7 months in patients worldwide and 6.5-11.4 months in Chinese or Asian patients,10-18 with potential for improvement in overall survival (OS) outcomes. Nevertheless, over the past 13 years, no other monotherapy has significantly improved OS compared with sorafenib, although the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab exhibited superior OS outcomes over sorafenib in the recent IMbrave150 trial.11,13-15,19 The 2018 REFLECT study showed noninferiority but not superiority of lenvatinib over sorafenib in improving OS.15 Furthermore, sorafenib treatment commonly results in side effects, such as hand-foot skin reactions (HFSR) and diarrhea.20 There remains an urgent need for new systemic treatments of HCC for improved clinical outcomes and safety, especially in China.

Donafenib is a novel, oral, small-molecule, multikinase inhibitor that inhibits the activity of multiple receptor tyrosine kinases, such as vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, and various Raf kinases, thereby suppressing tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis.9 Donafenib is a modified form of sorafenib with a trideuterated N-methyl group, potentially enhancing molecular stability for an improved pharmacokinetic profile.9 Preclinical, phase Ia and Ib studies have demonstrated good efficacy and safety profile for donafenib.9,21 This phase II-III clinical trial evaluates the efficacy and safety of donafenib versus sorafenib in the treatment of unresectable or metastatic HCC in patients without prior systemic therapy.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This randomized, open-label, parallel-controlled phase II-III clinical trial was conducted in 37 clinical research centers across China. The study enrolled patients who had unresectable or metastatic HCC, with diagnoses confirmed histopathologically, cytologically, or clinically (in accordance with the guidelines by the Chinese Ministry of Health, which are aligned with the international diagnostic criteria for HCC).22,23 Enrolled patients had ≥ 1 measurable lesion, as defined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST 1.1), a Child-Pugh liver function score ≤ 7, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score 0-1, and were HCC systemic therapy–naïve. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are included in the trial Protocol (online only).

The study Protocol was approved by the ethics committees of all participating centers. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, ICH Good Clinical Practice E6, and local laws and regulations. All patients provided written informed consent.

Study Treatment and Assessments

Eligible patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive oral donafenib (0.2 g twice a day) and sorafenib (0.4 g twice a day). Factors used in stratified random assignment included alpha-fetoprotein (AFP, < 400 μg/L v ≥ 400 μg/L), history of locoregional HCC therapy (yes v no), Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage (B v C), and portal vein invasion and/or extrahepatic metastases (present v absent).

Treatment continued until the incidence of progressive disease (PD; as per RECIST 1.1), occurrence of severe toxicity or intolerance, delay in treatment by > 2 weeks, poor compliance, investigator's decision because of new medical information, or pregnancy. A safety examination was performed once every 4 weeks, and an imaging evaluation once every 8 weeks. If the investigator considered a patient who developed radiologic PD but had good tolerance and showed evidence of clinical benefits (ie, obvious tumor necrosis, improved or stable quality of life, and relief of liver cancer–related symptoms), the patient could continue with study treatment after informed consent was obtained, until the criteria for treatment termination were met. In the event of grade 4 hematologic or grade 3 nonhematologic toxicities, according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0, study treatment interruptions and dosing frequency reductions (to once daily and then further to once every other day) were allowed.

Study End Points

The primary end point was OS. Secondary end points included progression-free survival (PFS), time to progression (TTP), objective response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR), survival rates at 6, 9, 12, and 18 months, and safety. PFS, TTP, ORR, and DCR were assessed by the investigator and Independent Review Committee (IRC) according to RECIST 1.1. The final analysis was based on assessment by IRC who were blinded to treatment identity. ORR and DCR were calculated according to confirmed responses (on the basis of two evaluations ≥ 8 weeks apart).

Statistical Analysis

The primary end point (OS) was first tested for noninferiority; hierarchical testing for superiority would follow without multiple comparison adjustments if noninferiority was achieved. On the basis of the phase Ib donafenib study21 and the Asia-Pacific study of sorafenib,12 the assumed hazard ratio (HR) for OS was 0.85. The chosen noninferiority margin of 1.08 corresponds to 50% retention of sorafenib's effect over placebo on the basis of the SHARP trial.24 This was deemed not clinically significant and approved by the China regulatory agency. It was estimated that 553 deaths would be required to have an 80% power to claim noninferiority at a significance level of 0.05 (two-sided). To observe the required number of deaths, a total of 660 patients were planned to be recruited.

An adaptive design was adopted for this phase II-III study. A total of 80 patients were to be enrolled in stage I (ie, phase II). The trial would continue to stage II if any of the following criteria was met: (1) At least 11 patients in the donafenib group achieved disease control (DCR ≥ 27.5%) without statistical difference between the two groups and (2) partial response (PR) was observed in two or more patients in the donafenib group. In stage II, an additional 580 patients would be recruited. The final analyses would be based on all 660 patients from the two stages.

mOS was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. OS comparison was performed using stratified log-rank test with random assignment stratification factors. HRs were estimated using Cox proportional hazards model, with treatment group and random assignment stratification factors as fixed effects and site as a random factor. Noninferiority could be claimed if the upper limit of the 95% CI for HR was < 1.08; additionally, if this was < 1.00, superiority of donafenib over sorafenib for OS could be claimed. PFS and TTP were evaluated in the same way. Differences in ORR and DCR were analyzed using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test.

The primary efficacy analysis was based on the full analysis set (FAS, all randomly assigned patients without major eligibility violation who received ≥ 1 dose of study drug) and the per-protocol set (patients who completed ≥ 1 treatment course, with no major protocol deviation that might have affected efficacy evaluation). The intention-to-treat (ITT, all randomly assigned cases) population was used for supportive analysis. A prespecified subgroup analysis of OS was performed in the FAS. The safety analysis set included all treated patients. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4. An independent third-party data monitoring committee (IDMC) was set up to monitor patients' safety and the study progress.

RESULTS

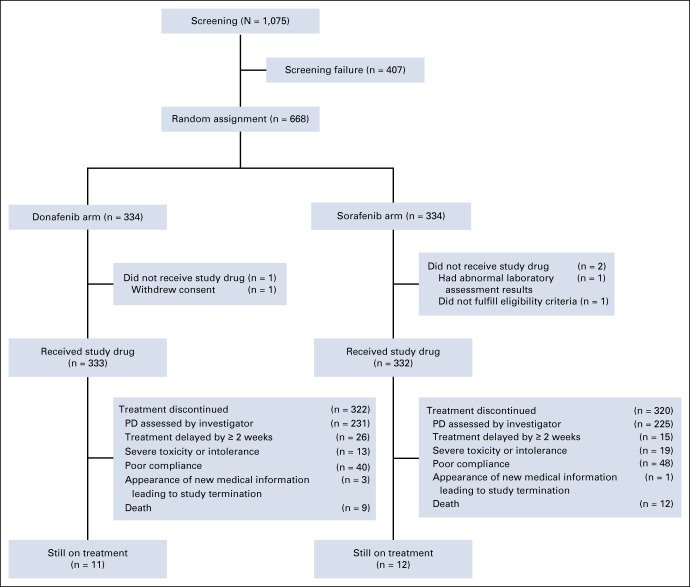

Between March 21, 2016, and April 16, 2018, 1,075 patients were screened, of whom 668 were randomly assigned (ITT, 334 in each arm). By December 28, 2016, among the patients enrolled in stage I, five in the donafenib group had achieved PR confirmed by IRC; this met the criterion of continuing to stage II. The FAS consisted of 659 patients (donafenib, n = 328; sorafenib, n = 331). Six patients in the donafenib arm were excluded from the FAS: one did not receive the study drug and five did not meet major inclusion criteria, three of whom had prior systemic treatment and the other two had received liver transplantation. Three patients in the sorafenib arm were excluded from the FAS: two did not receive the study drug and one did not meet major inclusion criterion (history of liver transplantation). A total of 665 treated patients were included in the safety analysis set (donafenib, n = 333; sorafenib, n = 332). As of September 30, 2019, 642 (97%) of 665 patients had discontinued treatment, including 322 (97%) in the donafenib arm and 320 (96%) in the sorafenib arm (Fig (Fig1).1). Discontinuation of treatment was mainly due to investigator-assessed PD.

Patient disposition from March 21, 2016, to September 30, 2019 (cutoff date). PD, progressive disease.

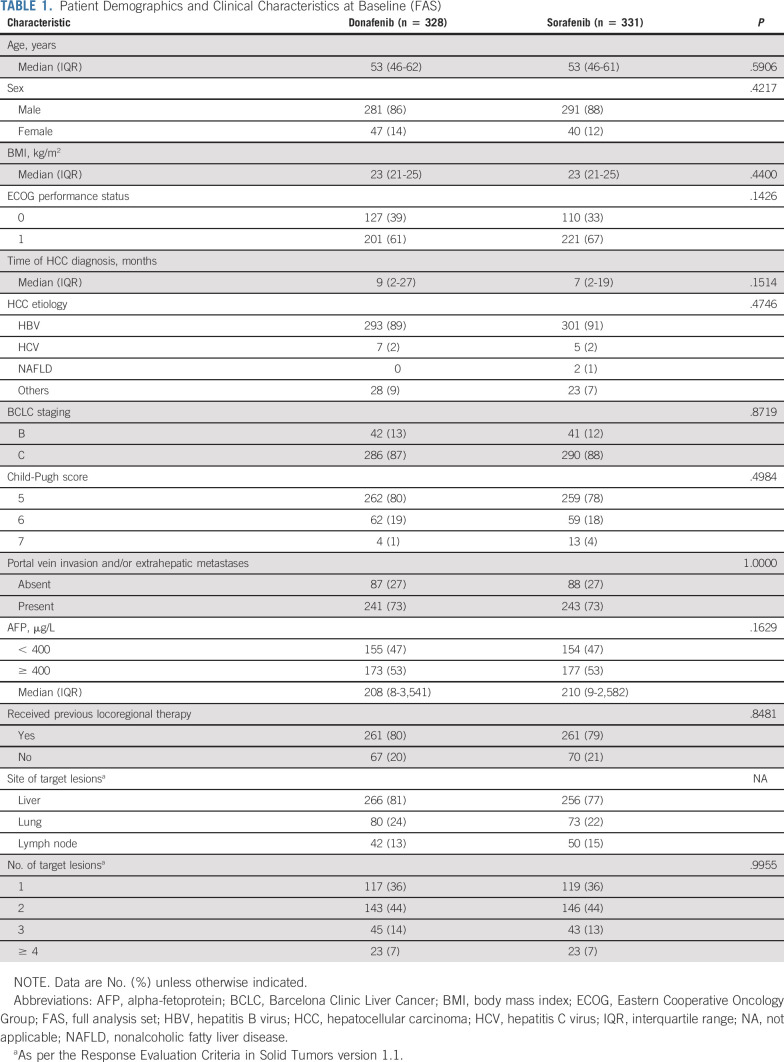

Baseline characteristics were well-balanced between the treatment arms. Among the 659 patients in the FAS, 594 (90%) had HBV infection, 576 (87%) were BCLC stage C, 642 (97%) were Child-Pugh Class A (scores 5-6), 422 (64%) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score of 1, 350 (53%) had baseline AFP ≥ 400 μg/L, and 484 (73%) had portal vein invasion and/or extrahepatic metastases (Table (Table11).

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics at Baseline (FAS)

Efficacy

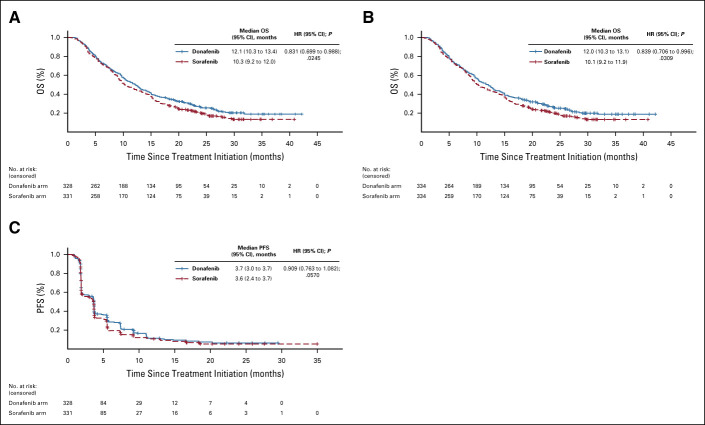

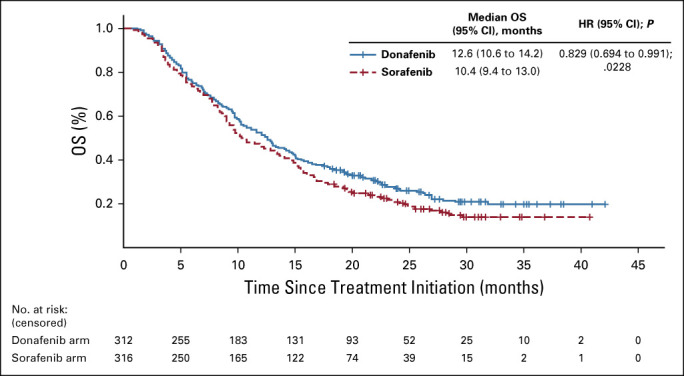

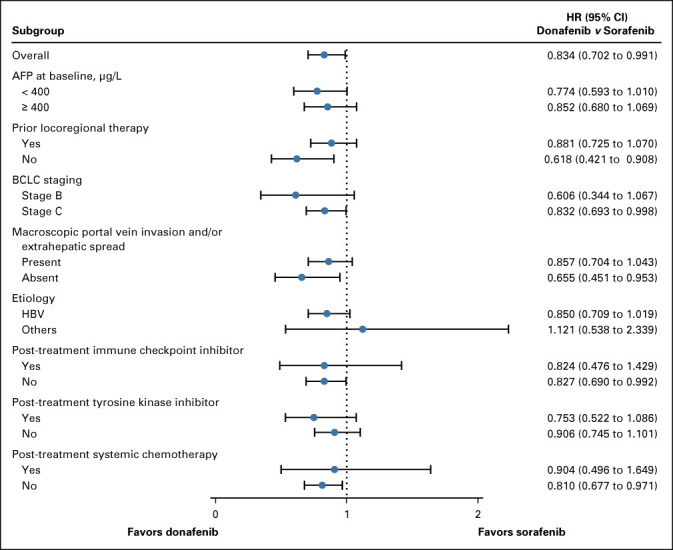

In the FAS, donafenib was associated with a significantly longer mOS than sorafenib (12.1 v 10.3 months; HR, 0.831; 95% CI, 0.699 to 0.988; P = .0245; Fig Fig2A).2A). The upper limit of 95% CI for HR was < 1.08 and < 1.00, indicating that both the noninferiority and superiority hypotheses hold true. The 18-month survival rate was higher with donafenib than sorafenib treatment (35.4% v 28.1%; P = .0460; Table Table2).2). The OS results in the ITT were similar to those in the FAS, with mOS of 12.0 months and 10.1 months for the donafenib and sorafenib arms, respectively (HR, 0.839; 95% CI, 0.706 to 0.996; P = .0309; Fig Fig2B).2B). Similar OS trends were observed in the per-protocol set (Appendix Fig AA1,1, online only). In the FAS, a trend of superior OS benefit with donafenib versus sorafenib was consistently observed across most predefined subgroups and statistically significant improvement in OS was achieved in some subgroups (Appendix Fig AA2,2, online only).

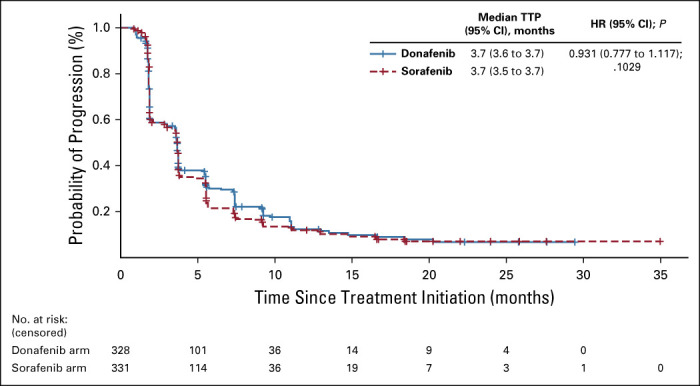

Kaplan-Meier analysis of OS in the (A) FAS and (B) ITT populations, and (C) Kaplan-Meier analysis of PFS in the FAS. FAS, full analysis set; HR, hazard ratio; ITT, intention-to-treat; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

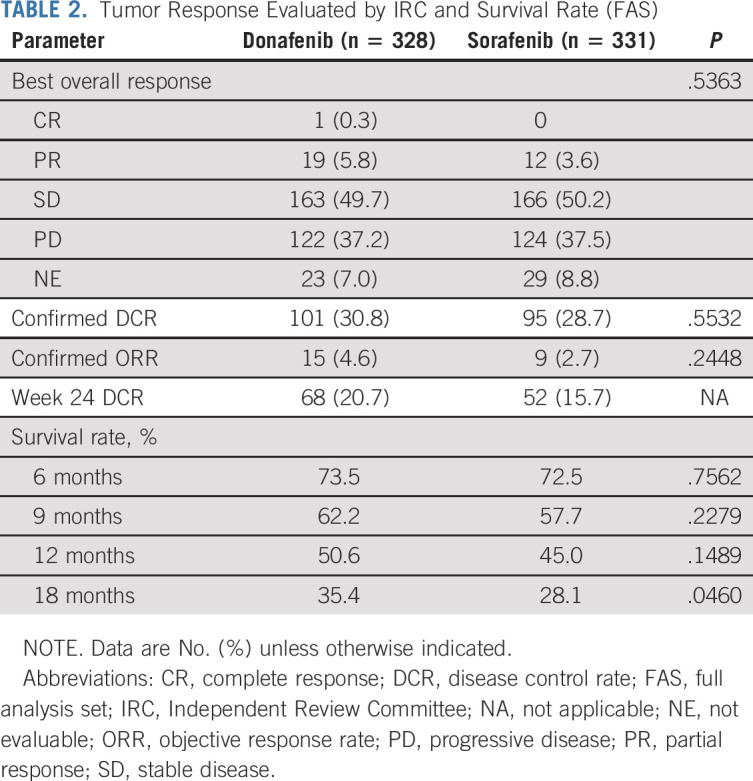

TABLE 2.

Tumor Response Evaluated by IRC and Survival Rate (FAS)

The median PFS (FAS) for donafenib versus sorafenib was 3.7 v 3.6 months (HR, 0.909; 95% CI, 0.763 to 1.082; P = .0570; Fig Fig2C),2C), and the median TTP was 3.7 v 3.7 months (HR, 0.931; 95% CI, 0.777 to 1.117; P = .1029; Appendix Fig AA3,3, online only). For best overall response, one patient (0.3%) achieved a complete response (CR) and 19 patients (5.8%) achieved PR in the donafenib arm, whereas no CR and 12 (3.6%) cases of PR were recorded with sorafenib treatment (Table (Table2).2). The ORRs were 4.6% and 2.7%, and the DCRs were 30.8% and 28.7%, in the donafenib and sorafenib arms, respectively. At week 24, a higher proportion of patients achieved disease control with donafenib (20.7%) than sorafenib (15.7%). Subsequent analyses confirmed that DCR at week 24 had a significant impact on long-term survival (P < .0001).

Exposure and Safety

In the safety analysis set, median exposure times were 110.0 days (interquartile range [IQR] 56.0-205.5 days) with donafenib and 113.0 days (IQR 56.0-213.0 days) with sorafenib treatment. Ninety-six patients (29%) in the donafenib arm and 127 (38%) in the sorafenib arm continued study drug administration for > 28 days after PD. Ninety patients (27%) in the donafenib arm and 111 (33%) in the sorafenib arm had at least one dose interruption. Among patients with dose interruptions, 89 patients (99%) in the donafenib arm and 107 (96%) in the sorafenib arm resumed treatment. Dose reductions were applied for 76 (23%) donafenib-treated and 98 (30%) sorafenib-treated patients.

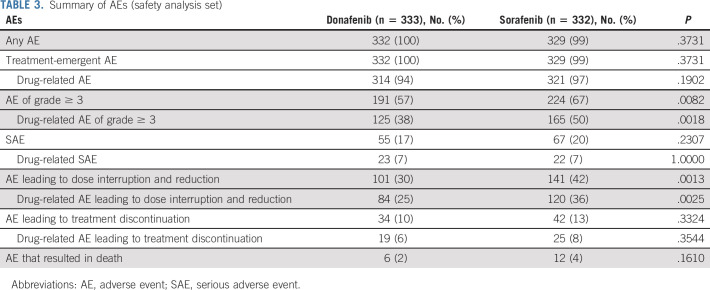

Adverse events (AEs) were reported by 332 (100%) and 329 (99%) patients in the donafenib and sorafenib arms, respectively, with 314 (94%) and 321 (97%) patients reporting drug-related AEs (Table (Table3).3). Six patients (2%) in the donafenib arm and 12 patients (4%) in the sorafenib arm reported AEs that resulted in death. Only two cases of fatal AEs (hepatic dysfunction and pulmonary infection), both in the sorafenib arm, were considered by investigators as possibly related to the investigational drug.

TABLE 3.

Summary of AEs (safety analysis set)

Fifty-five patients (17%) in the donafenib arm and 67 patients (20%) in the sorafenib arm reported at least one serious adverse event (SAE). Among these, 23 (7%) donafenib-treated and 22 (7%) sorafenib-treated patients reported drug-related SAEs. The most common drug-related SAEs were hepatic dysfunction (three [1%] donafenib-treated patients v seven [2%] sorafenib-treated patients), upper GI hemorrhage (three [1%] v four [1%]), and diarrhea (two [1%] v one [< 1%]).

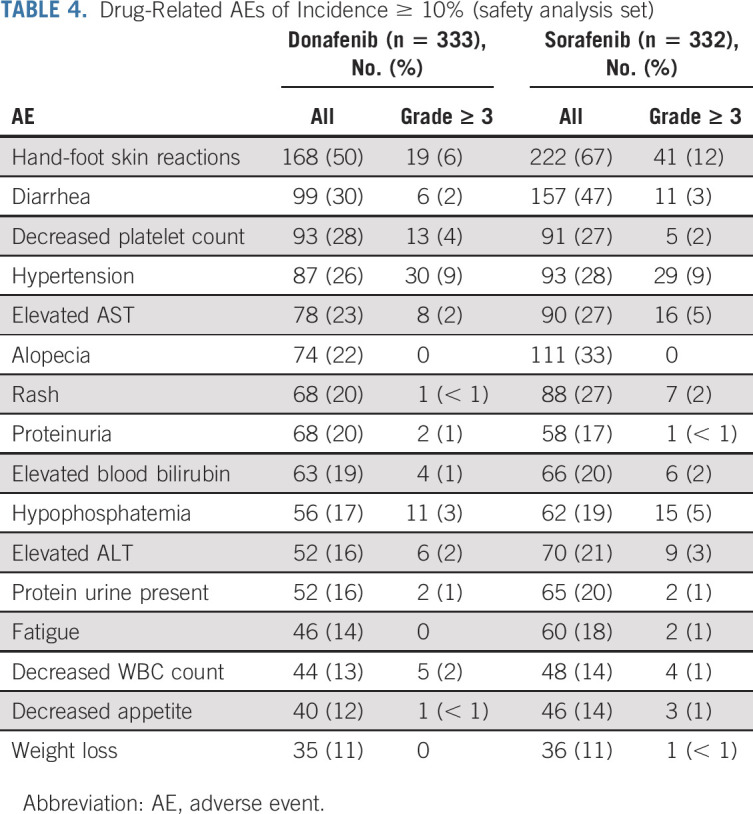

The most common drug-related AEs were HFSR (168 patients [50%] in the donafenib arm v 222 [67%] in the sorafenib arm) and diarrhea (99 [30%] v 157 [47%]; Table Table4).4). A total of 191 patients (57%) in the donafenib arm and 224 (67%) in the sorafenib arm experienced at least one grade ≥ 3 AE (P = .0082). In addition, the incidence of drug-related grade ≥ 3 AEs was significantly lower with donafenib than sorafenib treatment (125 [38%] v 165 [50%]; P = .0018; Table Table3).3). Common grade ≥ 3 drug-related AEs included hypertension (30 [9%] v 29 [9%]), HFSR (19 [6%] v 41 [12%]), decreased platelet count (13 [4%] v 5 [2%]), hypophosphatemia (11 [3%] v 15 [5%]), elevated AST (eight [2%] v 16 [5%]), diarrhea (six [2%] v 11 [3%]), and elevated ALT (six [2%] v nine [3%]) (Table (Table44).

TABLE 4.

Drug-Related AEs of Incidence ≥ 10% (safety analysis set)

A total of 101 patients (30%) in the donafenib arm and 141 (42%) in the sorafenib arm experienced AEs leading to dose interruption and reduction (P = .0013), among which 84 (25%) and 120 (36%) were drug-related (P = .0025). The number of patients reporting AEs that resulted in treatment discontinuation was also lower with donafenib than sorafenib (34 [10%] v 42 [13%]; Table Table33).

DISCUSSION

An improvement in the pharmacotherapy of advanced HCC remains a clinical need.25 To our knowledge, this pivotal head-to-head comparison study is the first to demonstrate noninferiority and superiority of a monotherapy, donafenib, with statistically significant extension in OS over sorafenib for first-line treatment of advanced HCC. The favorable OS benefit of donafenib was consistent across almost all prespecified subgroups. Donafenib also showed trend of improvement in PFS, TTP, ORR, and DCR, although statistical significance was not achieved. Additionally, donafenib exhibited a better safety and tolerability profile.

As far as we know, this remains the largest phase III clinical trial in Chinese patients with HCC. The inclusion criteria were identical to those of the pivotal worldwide (SHARP) and Asia-Pacific trials of sorafenib,12,24 allowing for fair comparisons. Patients enrolled in this study were representative of the HCC population in China: ≥ 90% HBV-positive, relatively poor performance status and liver function, high AFP levels, and a higher proportion of patients with BCLC stage C. Compared with international trials, patients in this study presented with more severe baseline disease states, further emphasizing the positive response observed with donafenib.

Donafenib, a deuterated sorafenib derivative, shows increased stability with reduced susceptibility to hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes, which may result in greater plasma exposure and reduced toxic metabolites.9,26 This improved pharmacokinetic profile of donafenib potentially explains the improved short-term efficacy and safety profile of donafenib over sorafenib, the combination of which may allow patients to obtain superior long-term survival benefit.

In vivo pharmacokinetic studies have indicated that donafenib levels in plasma and tumor tissues were higher than those of sorafenib at the same dose levels (unpublished data). Concordantly, donafenib exhibited stronger antitumor effects in human HCC xenografts compared with sorafenib (unpublished data). Clinically, the steady-state plasma concentration of donafenib (0.2 g twice a day) in Chinese patients with solid tumors, including advanced HCC, was higher (44.0-46.7 h·µg/mL),9 compared with 29.5-36.7 h·µg/mL for sorafenib (0.4 g twice a day) in east Asian patients.27,28 The higher donafenib exposure potentially contributed to the improvement in short-term efficacy observed with donafenib in this study.

Donafenib also exhibited a better safety and tolerability profile than sorafenib, consistent with early clinical studies of donafenib.9,21 A lower frequency of grade ≥ 3 AEs with donafenib contributed to improved patient adherence and decreased levels of drug interruption and discontinuation. The mass balance and biotransformation study using 14C-donafenib (unpublished data) indicated that the proportions of potentially toxic metabolites in stool and urine samples were lower than those previously reported for sorafenib,29 possibly explaining the improved safety profile of donafenib.

Besides showing superiority in OS compared with sorafenib, donafenib demonstrated improvements in PFS and ORR, although improvements in these secondary end points did not reach statistical significance. The survival benefit of donafenib over sorafenib was more apparent in the longer term, likely attributed to not only encouraging response and disease control but also improved tolerability. The superior long-term OS benefit with donafenib over sorafenib was supported by the subgroup analyses on the basis of the different later-line treatments that the patients received; patients who received first-line donafenib potentially continued to show a trend of survival benefits compared with those who received first-line sorafenib, regardless of whether they received later-line systemic treatment or the type received. With favorable efficacy and safety, donafenib monotherapy is a promising alternative in the first-line treatment of advanced HCC, supported by the recent recommendation from the Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology.8

Nevertheless, recent research suggests favorable outcomes for immune checkpoint inhibitors combined with antiangiogenesis therapy for HCC treatment.19 On the basis of the recent IMbrave150 trial, which showed that atezolizumab plus bevacizumab significantly improved OS (HR, 0.58) and PFS (HR, 0.59) compared with sorafenib, this combination has recently been approved as a first-line treatment for patients with advanced HCC.19 However, immune checkpoint inhibitors as a monotherapy have not achieved superior efficacy over sorafenib in HCC trials. In context, donafenib remains the sole monotherapy to show superior OS outcomes versus sorafenib. Moreover, the patients recruited in the IMbrave150 study generally had a better baseline status and the study had stricter exclusion criteria for patients with comorbidities, such as autoimmune disease, immune deficiency, severe hypertension, hemorrhagic tendency, or coinfection with HBV and HCV. Donafenib may provide a potential better option for these patients who are not suitable to receive immune checkpoint inhibitors and/or bevacizumab. In addition, trials exploring the safety and efficacy of donafenib in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors are ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04472858, NCT04503902, and NCT04612712).

This trial adopted an open-label design. Nevertheless, potential biases on outcome analyses have been minimized with OS as the primary end point, blinded assessment by the IRC, and data monitoring by IDMC. Furthermore, as sorafenib is an approved drug with considerable real-world evidence, our observation that more patients in the sorafenib arm continued study treatment after PD may be due to bias. Besides, response to sorafenib was known to be affected by the etiologies of HCC30; as patients from China (predominantly HBV-positive) were exclusively enrolled in this trial, additional studies are required to evaluate the efficacy and safety of donafenib compared with sorafenib in non-HBV or western populations. Finally, most patients enrolled in this study were of Child-Pugh Class A, and the efficacy and safety of donafenib in the Child-Pugh Class B population need further validation.

In summary, donafenib is the first monotherapy agent to achieve superior OS results over sorafenib in patients with unresectable or metastatic HCC and presented improved safety and tolerability, rendering it a new option for the first-line treatment of advanced HCC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank all the patients and their families, the investigators, and the teams who participated in this trial. We would also like to acknowledge Jin Li, Chairman of IDMC, for monitoring and reviewing the data. Xu Zhang from Hangzhou Tigermed Consulting Co, Ltd participated in the statistical analysis of the data. Xiaoyang Zhang (a medical advisor employed by Zelgen Biopharmaceuticals Co, Ltd) provided medical writing assistance in the preparation of the manuscript. Editorial assistance was also provided by Anita Abeygoonesekera, Qing Yun Chong, Rachael Profit, and Tim Stentiford from Nucleus Global, funded by Zelgen Biopharmaceuticals Co, Ltd.

Investigators are listed in Appendix Table A1 (online only).

Appendix

FIG A1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of OS (PPS). HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; PPS, per-protocol set.

FIG A2.

Forest plot of HRs for OS on the basis of subgroups. AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival.

FIG A3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of TTP (FAS). FAS, full analysis set; HR, hazard ratio; TTP, time to progression.

TABLE A1.

Full List of Study Investigators

Notes

Zhenggang Ren

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Roche, Merck Sharp & Dohme

Liqing Wu

Employment: Suzhou Zelgen Biopharmaceuticals Co, Ltd.

Stock and other ownership interests: Suzhou Zelgen Biopharmaceuticals Co, Ltd.

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented in part at the 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology Virtual Scientific Program, May 29-31, 2020, and European Society for Medical Oncology Virtual Congress 2020, September 19-21, 2020.

*S.Q. and F.B. are joint first authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Shukui Qin, Feng Bi, Shanzhi Gu, Zhendong Chen, Yinying Lu, Zhiqiang Meng, Jinlu Shan, Liqing Wu, Feng Chen

Financial support: Zhendong Chen, Jinlu Shan

Administrative support: Feng Bi, Yuxian Bai, Zhendong Chen, Jinlu Shan, Liqing Wu

Provision of study materials or patients: Shukui Qin, Feng Bi, Shanzhi Gu, Zhendong Chen, Zishu Wang, Jieer Ying, Yinying Lu, Hongming Pan, Ping Yang, Helong Zhang, Xi Chen, Aibing Xu, Chengxu Cui, Bo Zhu, Jian Wu, Xiaoli Xin, Jufeng Wang, Jinlu Shan, Junhui Chen, Zhendong Zheng, Li Xu, Xiaoyu Wen, Zhenyu You, Xiufeng Liu

Collection and assembly of data: Shukui Qin, Feng Bi, Shanzhi Gu, Yuxian Bai, Zhendong Chen, Zishu Wang, Jieer Ying, Yinying Lu, Hongming Pan, Ping Yang, Helong Zhang, Xi Chen, Aibing Xu, Chengxu Cui, Bo Zhu, Jian Wu, Xiaoli Xin, Jufeng Wang, Jinlu Shan, Junhui Chen, Zhendong Zheng, Li Xu, Xiaoyu Wen, Zhenyu You, Xiufeng Liu, Liqing Wu

Data analysis and interpretation: Shukui Qin, Feng Bi, Shanzhi Gu, Zhendong Chen, Zishu Wang, Jieer Ying, Yinying Lu, Ping Yang, Helong Zhang, Xi Chen, Aibing Xu, Chengxu Cui, Xiaoli Xin, Jufeng Wang, Jinlu Shan, Junhui Chen, Zhendong Zheng, Xiaoyu Wen, Zhenyu You, Zhenggang Ren, Xiufeng Liu, Meng Qiu, Liqing Wu, Feng Chen

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Donafenib Versus Sorafenib in First-Line Treatment of Unresectable or Metastatic Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Randomized, Open-Label, Parallel-Controlled Phase II-III Trial

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Zhenggang Ren

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Roche, Merck Sharp & Dohme

Liqing Wu

Employment: Suzhou Zelgen Biopharmaceuticals Co, Ltd.

Stock and other ownership interests: Suzhou Zelgen Biopharmaceuticals Co, Ltd.

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

Articles from Journal of Clinical Oncology are provided here courtesy of American Society of Clinical Oncology

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.21.00163

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://ascopubs.org/doi/pdfdirect/10.1200/JCO.21.00163

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/108400197

Article citations

A Gluconeogenesis-Related Genes Model for Predicting Prognosis, Tumor Microenvironment Infiltration, and Drug Sensitivity in Hepatocellular Carcinoma.

J Hepatocell Carcinoma, 11:1907-1926, 05 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39386981 | PMCID: PMC11463187

Clinical significance of upregulated Rho GTPase activating protein 12 causing resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma.

World J Gastrointest Oncol, 16(10):4244-4263, 01 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39473957 | PMCID: PMC11514672

Diversified applications of hepatocellular carcinoma medications: molecular-targeted, immunotherapeutic, and combined approaches.

Front Pharmacol, 15:1422033, 27 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39399471 | PMCID: PMC11467865

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

The Trend of the Treatment of Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Combination of Immunotherapy and Targeted Therapy.

Curr Treat Options Oncol, 25(10):1239-1256, 11 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39259476 | PMCID: PMC11485193

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Advancements in second-line treatment research for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Clin Transl Oncol, 20 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39162977

Review

Go to all (148) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Clinical Trials (3)

- (1 citation) ClinicalTrials.gov - NCT04503902

- (1 citation) ClinicalTrials.gov - NCT04612712

- (1 citation) ClinicalTrials.gov - NCT04472858

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Sintilimab plus a bevacizumab biosimilar (IBI305) versus sorafenib in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (ORIENT-32): a randomised, open-label, phase 2-3 study.

Lancet Oncol, 22(7):977-990, 15 Jun 2021

Cited by: 431 articles | PMID: 34143971

The Cost Effectiveness of Donafenib Compared With Sorafenib for the First-Line Treatment of Unresectable or Metastatic Hepatocellular Carcinoma in China.

Front Public Health, 10:794131, 31 Mar 2022

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 35433574 | PMCID: PMC9008355

Donafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Drugs Today (Barc), 59(2):83-90, 01 Feb 2023

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 36811408

Review

Efficacy and safety analysis of TACE + Donafenib + Toripalimab versus TACE + Sorafenib in the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study.

BMC Cancer, 23(1):1033, 25 Oct 2023

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 37880661 | PMCID: PMC10599044