Abstract

Free full text

Management of cholelithiasis with choledocholithiasis: Endoscopic and surgical approaches

Abstract

Gallstone disease and complications from gallstones are a common clinical problem. The clinical presentation ranges between being asymptomatic and recurrent attacks of biliary pain requiring elective or emergency treatment. Bile duct stones are a frequent condition associated with cholelithiasis. Amidst the total cholecystectomies performed every year for cholelithiasis, the presence of bile duct stones is 5%-15%; another small percentage of these will develop common bile duct stones after intervention. To avoid serious complications that can occur in choledocholithiasis, these stones should be removed. Unfortunately, there is no consensus on the ideal management strategy to perform such. For a long time, a direct open surgical approach to the bile duct was the only unique approach. With the advent of advanced endoscopic, radiologic, and minimally invasive surgical techniques, however, therapeutic choices have increased in number, and the management of this pathological situation has become multidisciplinary. To date, there is agreement on preoperative management and the need to treat cholelithiasis with choledocholithiasis, but a debate still exists on how to cure the two diseases at the same time. In the era of laparoscopy and mini-invasiveness, we can say that therapeutic approaches can be performed in two sessions or in one session. Comparison of these two approaches showed equivalent success rates, postoperative morbidity, stone clearance, mortality, conversion to other procedures, total surgery time, and failure rate, but the one-session treatment is characterized by a shorter hospital stay, and more cost benefits. The aim of this review article is to provide the reader with a general summary of gallbladder stone disease in association with the presence of common bile duct stones by discussing their epidemiology, clinical and diagnostic aspects, and possible treatments and their advantages and limitations.

Core Tip: Gallstone disease associated with common bile duct stones is a common clinical scenario. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is considered the gold standard for treatment of symptomatic gallbladder stones; conversely, the best treatment option for bile duct stones remains uncertain and controversial. We discuss herein the epidemiology, natural history, clinical presentations, preoperative diagnosis, management, complications, and different methods of treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Gallstones are a very common condition among the general population[1]. Generally, this situation does not cause symptoms, but 10%-25% of affected people may have specific symptoms, such as biliary pain and acute cholecystitis, and 1%-2% of these may have major complications[2,3]. In most cases, symptoms and major complications occur due to the migration of stones into the common bile duct (CBD) and this circumstance can cause obstruction of the bile flow in the small intestine, resulting in pain, jaundice, and sometimes cholangitis[4,5]. Primary choledocholithiasis refers to stones formed directly within the biliary tree, while secondary choledocholithiasis refers to stones migrated from the gallbladder. Primary stones are generally brown in colour and composed mainly of calcium bilirubinate; these stones are rare in Western populations and more common in Asia, but the exact aetiology and overall prevalence remain unclear. Secondary choledocholithiasis stone composition parallels that of cholelithiasis, with cholesterol as the most common type[6].

Of the total of cholecystectomies performed every year for cholelithiasis, the presence of CBD stones (CBDSs) is 5%-15%; another small percentage of these will develop CBDS after intervention[7]. The management of CBDSs represents an important clinical problem. In symptomatic patients, the primary goal is to obtain complete clearance of the CBD and cholecystectomy; on the contrary, in asymptomatic patients, there is still no shared diagnostic and therapeutic path[8]. In the last 20 years, the development of new technologies has allowed new diagnostic and therapeutic scenarios, with a consequent critical evaluation of management options. All these have led to a more cautious and patient-tailored preoperative workup based on the patient's risk and ultimately to a multidisciplinary approach[9-11]. However, if on the one hand multidisciplinarity has improved the management of patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis, on the other hand it has shown non-unanimous consent in the choice of treatment for choledocholithiasis: Endoscopic or surgical?

Since the early 1990s, laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has been considered the gold standard of treatment for cholelithiasis[12,13], while endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) was chosen for isolated CBDSs[5]; no consensus exists to address choledocholithiasis[14,15]. To date, many therapeutic options are available, including laparoscopic, endoscopic, percutaneous, and traditional open techniques, applied both as a combination in a simultaneous way or as a gradual sequence. The most followed therapeutic options are preoperative ERCP followed by LC; LC plus intraoperative laparoscopic CBD exploration (LCBDE); LC plus intraoperative ERCP (rendezvous technique); and, finally, LC plus postoperative ERCP. The preference between one technique and the other is, most of the time, guided by the presence of professional resources and local skills rather than by its verified effectiveness[16-20].

The aim of this review is to provide practical advice and an overview of how to manage patients with cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis. We take into consideration different diagnostic strategies, as well as the different therapeutic options available.

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL NOTES AND CLINICAL MANIFASTATIONS

Gallstones have a prevalence of 10%-15% in adult Caucasian populations and in the American Indians it can reach up to 70%[1,21]; on the contrary, Asian populations have a very low prevalence[22,23]. The risk factors associated with the most frequent formation of cholesterol stones are female sex, age over 40 years, obesity, and rapid weight loss[24]. The presence of gallstones remains asymptomatic in over 80% of cases, without any complications[21,25]. The risk of developing symptoms or complications varies between 1% and 2.3% per year[2,3,26-29] and in these patients, surgery is necessary.

The most frequent symptom is biliary pain, which is usually constant rather than discontinuous and appears when the gallbladder exit is obstructed by a stone. Most often it occurs in the right upper quadrant but can occur in the epigastrium, retrosternal area, or also the upper left quadrant. This pain has a typical irradiation to the ipsilateral scapula. Pain may be associated with vomiting, and it usually resolves completely but is often associated with other symptoms including flatulence, dyspepsia, and abdominal bloating. If biliary pain persists for more than 12 h, it is very likely that acute cholecystitis is occurring with associated fever, tachycardia, and then systemic inflammation.

Among the classic complications of gallbladder stones, we must remember acute cholecystitis which can resolve spontaneously or result in mucocoele, empyema, gangrenous cholecystitis, and emphysematous cholecystitis. Another complication is chronic cholecystitis, which usually occurs after recurrent episodes of biliary pain associated with phases of acute inflammation that result in fibrosis. Less frequent but not uncommon are Mirizzi syndrome, cholecysto-enteric fistulas, and the risk of malignant transformation in association with chronic cholecystitis. Migration of stones from the gallbladder to the CBD facilitated by gallbladder contractions can also be listed as a complication of gallstones. In the CBD, they can reach the duodenum following the bile flow or they can remain in the choledochus. In the latter case, they can remain asymptomatic or cause a variety of biliary problems. Incidence of choledocholithiasis increases with age, and between 20% and 25% of these patients with symptomatic gallstones have stones in the CBD and in the gallbladder[7,8]. The Swedish registry[30] showed a prevalence of 11.6% of choledocholithiasis detected during intraoperative cholangiography in patients with symptomatic gallbladder stones. Important studies concerning the prevalence of choledocholithiasis in patients with asymptomatic cholelithiasis are currently lacking.

Complications due to the presence of stones of the CBD are biliary pain and obstructive jaundice secondary to obstruction and subsequent dilation of the biliary tree[31], cholangitis due to bacterial infection facilitated by biliary obstruction, and ultimately acute biliary pancreatitis, which together with pain represent the largest percentage of such. Complications that most require endoscopic or surgical intervention are those that occur in the presence of choledocholithiasis.

PREOPERATIVE INVESTIGATIONS

The main issue for the correct management of cholecysto-choledocholithiasis is to arrive at the diagnosis by reducing the useless and invasive diagnostic procedures that are often performed inappropriately following non-linear clinical hypotheses. Generally, suspicion of the disease arises from the presence of specific symptoms associated with an alteration of the cholestasis indexes followed by an abdominal ultrasound (US) examination. Signs and symptoms of these are well known and previously mentioned. Instead, it is necessary to focus on preoperative serological and instrumental diagnostic investigations.

Serology

Normal values of liver function tests are considered predictive of the absence of CBDS. Yang et al[32] in 2008 presented a study conducted on 1002 patients undergoing LC, which confirmed the absence of CBDSs in the presence of normal values of liver function indexes. Total and direct bilirubin and gamma-glutamyltransferase demonstrated the highest sensitivities at 94.7% and 97.9%, respectively. Gurusamy et al[33] in 2015 proposed a systematic review on the diagnostic accuracy of liver function tests, concluding that the sensitivities of bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase were 84% and 91%, respectively, while the corresponding specificities were 91% and 79%.

Therefore, an alteration of total and direct bilirubin, gamma-glutamyltransferase, and alkaline phosphatase[34,35] has always been associated with the suspicion of choledocholithiasis, as well as the presence of elevated hepatic cytolysis values, as it was found in the presence of unrecognized CBDSs[34,36,37]. To date, total and direct bilirubin are considered the most reliable markers for the suspicion of choledocholithiasis, but the other liver biochemical tests should not be underestimated[38].

Radiological examinations

Diagnostic suspicion is essential to select patients to be directed to a more accurate study. Several predictive models have been developed but the association between the presented symptoms, biochemical data, and an US examination of the abdomen is often the most suitable way to identify high risk patients[35,39-42]. Abdominal US is the first non-invasive, inexpensive, and practicable examination to be performed almost anywhere[38,43,44]. This examination is also useful for evaluating the presence of other liver diseases. The high sensitivity of US (96%)[45] for the study of the gallbladder and the identification of stones inside it is due to the proximity of the organ to the abdominal wall and the absence of interposed gas.

Unfortunately, US often fails to confirm the presence of CBDSs because they do not show the characteristic acoustic shading or are located in the distal part of the choledochus, where they can be obscured by gas[46]. In these situations, it is necessary to evaluate the presence of indirect signs of obstruction, such as dilation of the CBD. Even the definition of the concept of dilation of the CBD is not very clear, the most used range is between 5 mm and 11 mm[47-49], bearing in mind that some dilation can also occur after cholecystectomy and with advancing age. Another indirect sign of suspected choledocholithiasis can be provided by the number and size of gallbladder stones[44,50]. US confirmation of small gallstones increases the possibility that they can migrate into the CBD[51,52]. Wilcox et al[53] in 2014 and Qiu et al[54] in 2015 reported two studies that had demonstrated, with different techniques and percentages, the presence of CBDSs in patients who had normal findings on liver function tests and US. For these reasons, abdominal US is certainly to be performed in the first instance, but in the suspicion of choledocholithiasis even with a normal serology and US evaluation it is a good rule to deepen the diagnosis with second-line examinations, which are more expensive and invasive.

Computed tomography (CT) is often done in emergency situations and for abdominal pain assessment. It is considered a second-line examination for the diagnosis of this pathological condition, but the literature expresses heterogeneous judgments regarding its diagnostic value and it is usually considered a non-definitive test. In fact, many gallstones are similar in density to the surrounding bile and lack of calcium; these occurrences limit the visibility of CT and therefore its sensitivity. The CT scan increases exposure of patients to X-rays and leads to higher costs than US. It is considered more accurate than the latter in the identification of CBDSs[55] but certainly inferior to magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC)[56]. Greater diagnostic precision has been achieved with helical CT[38,57] and CT cholangiography[56,58]. CT cholangiography has shown a sensitivity in some studies and a specificity almost comparable to that of MRC[56,58]. The new multi-detector CT has shown a sensitivity of 78% in the portal venous phase and a specificity of 96% in the identification of CBDSs[57]. On the other hand, Kim et al[59] in 2013 reported that in 17% of cases, the 64-detector CT does not visualize CBDSs, due to size of < 5 mm, black/brown colour, and the patient's age. The greater radiological exposure and lower diagnostic power of CT compared to MRC make the latter examination preferable. However, CT examination has reduced execution times and extreme availability and diffusion, and these aspects could in the future assign it a new role in this field.

MRC and endoscopic US (EUS) are currently the radiological examinations used routinely to avoid unnecessary and more invasive procedures, such as ERCP. Specifically, MRC is now considered the most accurate non-invasive procedure for the detection of CBDS, with a sensitivity of 93% and specificity 96%[60]. It is non-invasive, does not require contrast, and can be performed without anaesthesia.

Meeralam et al[61] in 2017 demonstrated that diagnostic accuracy of EUS and MRC was high for both methods: Sensitivity of 97% vs 90% and specificity of 87% vs 92%. This was mainly due to the significantly higher sensitivity of EUS in the identification of small stones, while the specificity was not significantly different. The major limitation is the cost, and routine MRC for biliary disease without positive laboratory tests for CBDSs is not cost-effective[62]. Other disadvantages of MRC are its suboptimal availability in non-tertiary care centres and non-therapeutic purposes of the technique; in fact, in the case of CBDS diagnosis, it will be necessary to use other treatment procedures. Its use is difficult in patients with severe obesity and claustrophobia, and in the presence of metallic foreign bodies or other metallic devices. Small stone diameter (< 5 mm) and peripancreatic oedema have been shown to reduce the accuracy of CBDS identification[63]. Regardless of the overall effectiveness, the points in favour of this diagnostic procedure are its non-invasiveness and higher spatial and three-dimensional resolution, with the use of dedicated software, compared to EUS; in any case, it remains an operator-dependent diagnostic investigation. However, despite some of its limitations and low territorial diffusion, it should always be preferred before referring patients to other more invasive procedures.

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (commonly referred to as PTC) is a procedure that is performed with percutaneous cannulation of the intrahepatic biliary system, with contrast injection monitored by fluoroscopy. This technique can demonstrate biliary anatomy, including the size, number, and position of the stones, in the same way as ERCP. PTC is rarely used for the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis following the advent of modern radiological and endoscopic imaging techniques. However, it can be the initial component of the percutaneous transhepatic therapies for biliary tract disease, including choledocholithiasis, often when ERCP is not feasible.

Endoscopic examinations

All endoscopic procedures are invasive for the patient. They are also diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. ERCP involves cannulation of the ampulla of Vater and then of the CBD; through the injection of contrast medium under fluoroscopy, defects in filling are observed. This method is often used as a procedure of choice for evaluating the presence of choledocholithiasis, but complications can occur in as many as 8% to 12% of patients, usually manifesting as pancreatitis[64-66]. Due to its invasiveness and possible complications, ERCP is recommended for patients with a high probability of choledocholithiasis; this endoscopic examination conducted by expert operators can also be an adequate treatment[38]. Although most endoscopists routinely reach the second portion of the duodenum, there are some situations that can make this manoeuvre difficult. Sometimes, the papilla major is difficult to identify and cannulate; this then represents a time of stress and danger for the operator as well as for the patient, such as when the cannula is placed in a duodenal diverticulum[67]. Previous surgical procedures on the stomach are another frequent cause of ERCP failure. The second duodenal portion is difficult to reach after a Roux-en-Y reconstruction, omega anastomosis, and gastric by-pass, and after gastrectomy with duodenal stump closure and Billroth II reconstruction[68,69]. In those cases, diagnosis and treatment must be conducted surgically.

In the past decades, ERCP has been widely used for the diagnosis of CBDS; today, this procedure is being abandoned, especially in those patients who have a low or moderate risk of disease[70]. ERCP accuracy is lower than that of EUS and MRC, especially in cases of dilation of the CBDS and presence of small stones[71]. Furthermore, this procedure has a non-negligible morbidity and exposes the patient to X-rays and complications such as pancreatitis. The use of sphincterotomy during ERCP is therapeutic and mandatory in high-risk patients, but this procedure in untrained hands can increase morbidity and mortality, possibly causing duodenal perforation or haemobilia. Therefore, the use of ERCP is recommended in those patients with strong suspicion of choledocholiasis; in other cases, the use of EUS or MRC is preferable[38]. The increase of the laparoscopic approach for the treatment of patients with cholelithiasis, which has completely replaced open surgery, has revived the therapeutic role of ERCP. To date, for the management and treatment of cholecysto-choledocholithiasis, the most used approaches are in two sessions or in a single session, and in both cases the ERCP retains a fundamental role.

A further refinement of the classic endoscopic procedures is represented by the endoscopic US, which uses an US probe mounted on the tip of an endoscope. EUS does not use ionizing radiation. In comparison to ERCP, it is more useful for stones smaller than 5 mm and has a complication rate between 0.1% and 0.3%[38]. EUS may not be adequate in patients undergoing gastric surgery, as the anatomical situation would be altered. Like transabdominal US, EUS is not limited by bowel gas, but it is always an operator-dependent procedure. Giljaca et al[72] in 2015 published the results of a systematic review, reporting high rates of diagnostic accuracy for both EUS and MRC for choledocholithiasis. The authors found a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 97% for EUS, and a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 96% for MRC. The choice between EUS and MRCP, for intermediate probability choledocholithiasis, is based on the resource availability, personal experience, and costs[73].

INTRAOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

LC is confirmed as the gold standard for the treatment of symptomatic cholelithiasis[12,13], but the therapeutic choice for CBDS is not clear. For the latter situation, the available strategies, conducted in a minimally invasive way, can be divided into two-session treatments and single-session treatments. The first category includes preoperative ERCP followed by LC, and LC followed by postoperative ERCP; the second category includes LC with LCBDE, and LC with intraoperative ERCP, also called the rendezvous technique.

Two-session options

Preoperative ERCP followed by LC is the most frequently used treatment worldwide[74]. Various studies have shown that this two-session approach is safe and effective[17,75,76]. Its limits are represented by a percentage between 40% and 70% of negative results that expose patients to unnecessary and risky endoscopic manoeuvres[77-79]. The development of diagnostic techniques such as MRC and EUS have increased the anatomical visualization of the biliary tract and have showed a high sensitivity and specificity for preoperative diagnosis of CBDS, all without the aid of special instruments and with less invasive approaches[80,81]. Lefemine et al[82] demonstrated that more than 50% of patients with CBDS have spontaneous passage of the stones, and 12.9% of patients already undergoing ERCP still had CBDSs during LC[83]. These events could be due to an ineffective ERCP or to a further migration of stones during the latency time between endoscopic and surgical intervention. Preoperative ERCP could increase the conversion rate from LC to open surgery, prolong the operating times, and have higher morbidity. It should also be emphasized that the high morbidity mainly translates into postoperative infections and consequently a longer hospital stay[84-86]. Preoperative ERCP followed by LC often requires two rounds of anaesthesia and two hospitalizations, and in the time between the two procedures, some patients may escape LC, being satisfied by the results of the preoperative ERCP[87,88]. Therefore, for this treatment modality, it is a good rule not to delay the LC too much and also to avoid the occurrence of recurrent events[89].

Another option is LC followed later by postoperative ERCP. This technique is rarely performed as the first choice for the treatment of cholelithiasis with choledocholithiasis because in a low percentage of cases it fails the intended purpose. The failure may be due to the operator's lack of experience, the absence of a guide wire, and a site altered by the previous surgery for inflammatory phenomena. The negative result of the endoscopic treatment necessarily leads to surgery, which can be more demanding than if it had been performed before. The postoperative ERCP retains a role when the intraoperative laparoscopic exploration fails or if during a LC, the presence of CBDS is found with the impossibility of performing it intraoperatively. Obviously, also in this case, the patient is subjected to two rounds of anaesthesia, with possible increase in morbidity, lengthening of the hospital stay, and higher costs[90,91].

One-session options

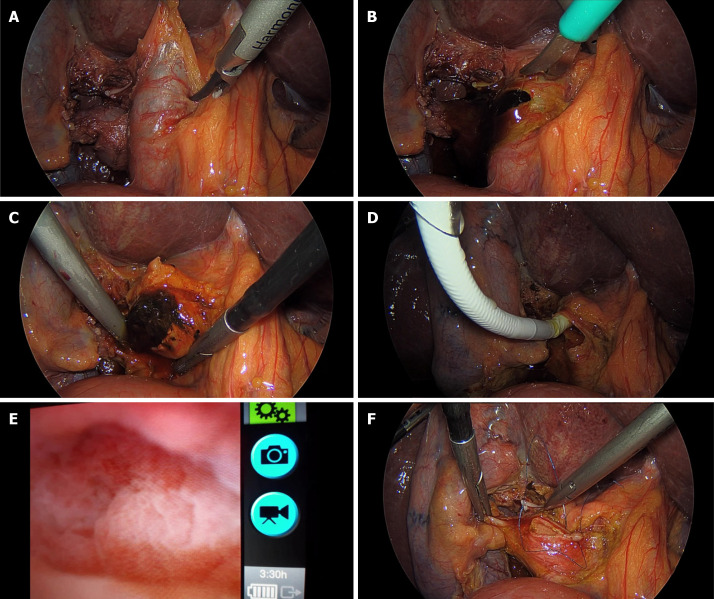

One-session procedures have confirmed benefits now, both in suspected cases and in proven cases of CBDS. These procedures are believed to be efficient, safe, convenient, and well accepted by patients, as the two different pathological conditions are resolved in a single surgery with single anaesthesia[92,93]. Regarding laparoscopic exploration of the CBD (Figure (Figure1),1), some authors have described stone removal rates ranging from 94% to 98%, low morbidity, and a mortality rate of 0%[94,95]. Through laparoscopic exploration, negative events that can occur during endoscopic sphincterotomy, such as pancreatitis, perforation, bleeding, cholangitis, and malignancies of the CBD, are avoided. However, this technique has some drawbacks.

Intraoperative images: Laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct. A: Common bile duct (CBD) dilation; B: CBD section; C: Stone extraction; D: Insertion of the choledochoscope into the CBD; E: Choledochoscopic image of the CBD; F: Suture of CBD.

First, the procedure requires high-level skills in laparoscopic surgery with long learning curves and there is a need for dedicated instruments; it is understandable that these qualities may not be present in all treatment centres[96]. Many surgeons prefer the transcystic approach, which is considered less invasive and less complicated; however, choledochotomy is recommended in cases of dilated CBD, large diameter or multiple stones, impacted stones, and stones with intrahepatic localization[97-99]. The transcystic exploration route is often more challenging, due to a small diameter and tortuous and low-base implant duct. We can affirm that it is logical to start transcystically but in case of difficulty to move on to exploration through choledochotomy[100,101]. During laparoscopic exploration, stone removal can be guided fluoroscopically or by choledochoscopy. The use of a flexible choledochoscope is the most preferred because it increases precision and is under direct visual control. The choledochoscope also presents some criticalities; first of all, it is a fragile instrument that can break during the procedure, thereafter needing a double monitor for laparoscopic and choledochoscopic viewing and causing an increase in costs. Fluoroscopic guidance exposes the patient to radiation, increases the length of the procedure, and requires instrumentation that can hinder the operator's movements. In this regard, Topal et al[102] in 2007 compared the two procedures; the results showed a difference in the duration of the surgical time, being shorter in the group of patients treated with a flexible choledochoscope.

After the choledochotomy, the closure of the CBD can be performed directly or with the positioning of the T-tube endoprosthesis[103,104]. The T-tube provides easy percutaneous access for cholangiography and extraction of preserved stones[105]. However, the T-tube can accidentally detach, promoting CBD obstruction, bile loss, persistent biliary fistulas and skin abrasions, cholangitis from exogenous sources through the T-tube, and dehydration and salt depletion[106-109]. The T-tube also requires long and continuous management, limiting the patient's quality of life[110]. Some authors have concluded that primary closure is preferred over T-tube placement, as the latter increases operative time and hospital stay[111]. The most common complications of this technique are CBD tearing, leakage of bile, stitched T-tubes, and the formation of strictures[99]. The results of three recent studies did not show biliary strictures, and approximately 640 patients were observed undergoing LCBDE with an average follow-up of more than 3 years[112-114]. LCBDE for the treatment of primary choledocholithiasis showed a high rate of stone recurrence (36.4%-41.7%)[115,116], possibly because it does not affect the biliary tract structure and lithogenic environment[117]. Endoscopic and surgical techniques for extracting these stones are equally valid in terms of efficacy, morbidity, or mortality[5]. However, endoscopic sphincterotomy may leave a higher incidence of retained stones (16%) compared to the surgical approach (6%)[31]. Currently, endoscopic sphincterotomy or endoscopic papillary balloon dilation represent the first-line treatment for initial primary choledocholithiasis, while the LCBDE should be performed for large stones, keeping the sphincter of Oddi intact.

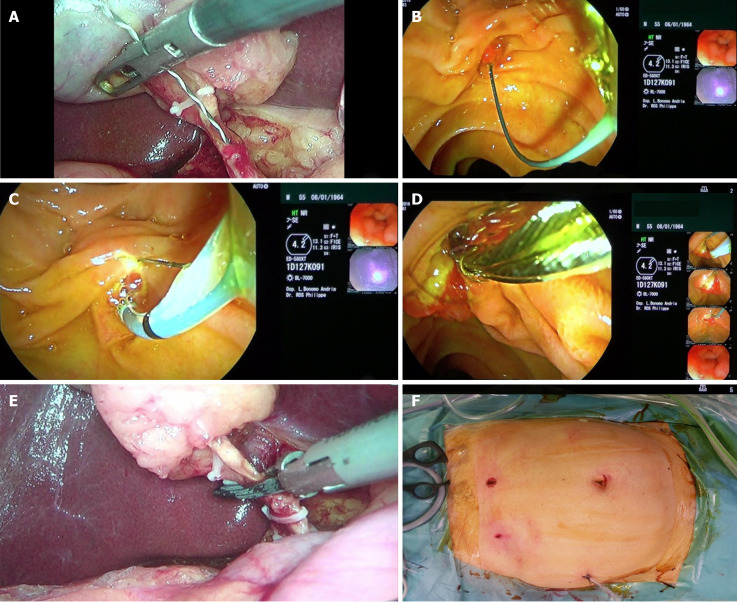

Another single-session minimally invasive procedure for the treatment of cholecysto-choledocholithiasis is ERCP during the LC, also called the rendezvous technique (Figure (Figure2).2). This approach was found by many experts to be safe and effective[77,118-120], and to require single hospitalization and single anaesthesia. For the exploration and extraction of the stones, the CBD is not opened, postoperative ERCP is avoided, and in case of extraction failure, surgical exploration is carried out during the same operation, with cost reduction. Despite these benefits, the procedure is not widespread, probably because operative endoscopy is not present in all treatment centres, and often when this exists, there is no expert operator. Intraoperative ERCP can be conducted in several ways. One of these is that after catheterization of the cystic duct, cholangiography is performed and in the event of a positive result, ERCP is performed and subsequently the LC is completed[121]. Some authors have proposed performing LC as a first step and then intraoperative ERCP[122]. Cavina et al[123] in 1998 proposed the rendezvous technique, a combined laparo-endoscopic approach which, due to its simplicity, has been widely used as a single-session treatment. A guide wire is introduced through the cystic duct and out the ampulla of Vater into the duodenum. Using side-viewing duodenoscope, the protruding guide wire is grasped by a snare or basket and a standard sphincterotome is threaded over it to facilitate endoscopic sphincterotomy and/or stone removal.

Intraoperative images: Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy (“rendezvous technique”). A: Insertion of the guide wire into the cystic duct; B: Guide wire exits through the papilla into the duodenum; C: Endoscopic sphincterotomy on guide wire; D: Extraction of stones from the common bile duct with a dormia basket; E: Section between clips of the cystic duct and subsequent retrograde cholecystectomy; F: Postoperative final scars.

Other authors have proposed further variations to the rendezvous technique[124]. In one, after the endoscopic sphincterotome is passed over the guide wire through the papilla, an endoscopic sphincterotomy is performed under the direct vision of a simultaneously positioned duodenoscope. The rendezvous technique compared to classical ERCP has shown advantages in cannulation in the supine position and lower incidence of postprocedural pancreatitis[125]. The explanation for these results is that during classical ERCP, contrast medium is injected and often inadvertently cannulated into the pancreatic duct[126,127]. However, problems can occur during the rendezvous technique. The insertion of the guide wire may not be easy, due to the valves present in the cystic duct; inside the CBD, it can twist, due to the presence of impacted stones, and can not enter the papilla. During the ERCP, due to the insufflation of air, the bowel can stretch and cause difficulties for the LC. In expert hands, these obstacles can be overcome; the use of an atraumatic laparoscope has been proposed for a clamp positioned on the first jejunal loop or a bowel desufflator[128,129], as well as to completely dissect the Calot triangle and the attachment between the liver and gallbladder or to even remove the gallbladder from the liver bed until the last centimetres are left at the fundus before the starting of the endoscopic phase[130].

There are no definitive indications and contraindications in the literature for two-session or one-session treatment. It is clear that, in those centres that have technical and human resources available, all patients with cholelithiasis and concomitant choledocholithiasis can be treated via a one-session approach. La Greca et al[131] in 2008, after observing 80 consecutive patients affected by cholecystolithiasis and diagnosed or suspected CBDSs treated by the rendezvous technique, evaluated the factors that suggest the preference of the rendezvous technique over other treatments (laparoscopic CBD exploration and sequential ERCP-endoscopic sphincterotomy, commonly referred to as ERCP-ES) (Table (Table11)[131]. On the other end, the advantages and disadvantages of one-session compared to two-session are clearer. The first procedure is associated with a shorter hospital stay, fewer procedures, and less cost, but local resources and expertise must be present. Other factors that can influence its choice are patient fitness, clinical presentation, timing of CBDS diagnosis (preoperative or intraoperative), and the surgical pathology. Finally, patients with acute biliary pancreatitis and septic shock from cholangitis are not ideal candidates for the one-session option, and could benefit from two-session[132,133].

Table 1

Factors that suggest the preference of the rendezvous technique over other treatments

|

Main indications for the laparo-endoscopic RV

|

RV preferable vs laparoscopic CBD exploration

|

RV preferable vs sequential ERCP-ES

|

| (1) CBD stones not easily extractable | (A) Need of higher surgical skill | (a) Risk of synchronization |

| through the cystic duct | (B) Longer operation time | (b) Risk of unnecessary ERCP |

| Positive factor - > (time reduction) | (C) Need of biliary drain | (c) Risk of difficult retrograde |

| cannulation | ||

| (2) Multiple small CBD stones and large friable stones | A, B, C + | a, b, c |

| Positive factor - > (reduction of risk of recurrence) | (D) High risk of residual fragments and recurrence | |

| (3) Any type of CBD stones with delayed passage of the | A, B, C, D + | a, b, c |

| contrast medium during IOC or T-tube-IOC after | (E) High risk of undertreatment of chronic | |

| laparoscopic CBD exploration | papillitis and of maintenance of underlying causes | |

| Positive factor - > (reduction of risk of recurrence) | ||

| (4) CBD stones with previous cholangitis | A, B, C, D + | a, b, c + |

| Positive factor - > (reduction of risk of recurrence) | (E) High risk of maintenance of underlying causes | (d) Avoidance of contrast medium injection |

| at the papilla | with risk of recurrence of cholangitis | |

| (5) CBD stones after recurrent acute biliary pancreatitis | A, B, C, D, E | a, b, c, d + |

| or hyperbilirubinemia | (e) risk of recurrence of ERCP | |

| Positive factor - > (iatrogenic risk reduction) | related acute pancreatitis | |

| (6) Known or unsuspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, | A, B, C, D, E | a, b, c, d, e |

| cholecysto-lithiasis with or without CBD stones | ||

| Positive factor - > (iatrogenic risk reduction) | ||

| (7) CBD stones and/or abovementioned problems in patients | A, B, C, D, E + | a, b, c, d, e + |

| with Billroth Ⅱ during open cholecystectomy | (F) Manual drive of the endoscope by the surgeon | (f) more difficult ERCP |

| Positive factor - > (iatrogenic risk reduction) | in the afferent jejunal loop | |

| (8) CBD stones, SOD, acute pancreatitis in children/CBD | A, B, C, D, E + | a, b, c, d, e, f + |

| stones in patients with normal or thin CBD | (G) difficult laparoscopic CBD exploration and risk | (h) avoidance of |

| Positive factor -> (iatrogenic risk reduction) | of stenosis of the suture | sphincterotomy in children |

| (9) CBD stones and/or SOD after failure of preoperative | A, B, C, D, E | a, b, c, d, e, f |

| ERCP-ES or recurrence of acute biliary pancreatitis | ||

| Positive factor - > (iatrogenic risk reduction) | ||

| (10) Inexperienced surgeon for laparoscopic CBD exploration | A, B, C, D, E, G | a, b, c, d, e, f |

| Positive factor - > (iatrogenic risk reduction) |

Citation: La Greca G, Barbagallo F, Di Blasi M, Chisari A, Lombardo R, Bonaccorso R, Latteri S, Di Stefano A, Russello D. Laparo-endoscopic “Rendezvous” to treat cholecysto-choledocolithiasis: Effective, safe and simplifies the endoscopist’s work. World J Gastroenterol 2008 May 14; 14(18): 2844-2850. Copyright ©The Author(s) 2019. Published by Baishideng Publishing Group Inc[131]”. CBD: Common bile duct; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography; ES: Endoscopic sphincterotomy; IOC: Intraoperative cholangiography; SOD: Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction.

HINTS ON SUPPLEMENTARY TREATMENTS

Through an endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy or a laparoscopic procedure, the extraction of ductal stones may not be completed or be difficult; in these cases, the open surgical approach still retains an important role, like other additional techniques.

Open surgical procedure

Four decades ago, cholelithiasis was treated exclusively by open cholecystectomy and similarly, choledocholithiasis was managed by open CBD exploration, which was performed by duodenotomy and sphincterotomy or bilioenteric anastomosis[134]. Open surgery is now considered obsolete, but the recent literature has shown its superiority over ERCP in the clearance of CBDS, with lower morbidity and mortality rates (20% vs 19% and 1% vs 3%, respectively)[31,135]. Open exploration of the CBD can be conducted through a coledochoenterostomy or a sphincterotomy; the choice depends on the surgeon’s experience[136]. Some authors prefer coledochoenterostomy for CBD with a diameter greater than 2 cm, in order to create a large opening between the bile duct and intestine. An emerging problem is that open biliary surgery is performed increasingly less outside specialized centres in hepato-bilio-pancreatic surgery; this raises new questions regarding the most appropriate management of those patients. Their number is scarce but not negligible, and their complex cases often need conversion or revision using an open approach by skilled surgeons.

During the sphincterotomy, an incision of approximately 1 cm is made in the distal part of the sphincter musculature. A catheter or dilator is passed distally and a Kocher manoeuvre is performed, followed by duodenotomy at the level of the ampulla. The dilator exposes the ampulla in the operating field, where it is sufficiently incised along its anterosuperior border with subsequent removal of the impacted stone[137]. Choledocoenterostomy is commonly performed as a side-to-side choledochoduodenostomy for dilated CBD with multiple stones. These patients require drainage for good long-term results without recurrence of jaundice or cholangitis[138]. The most used technique is that of a side-to-side hand-sutured anastomosis between the supraduodenal CBD and the duodenum[139]. Kocher's manoeuvre is performed to expose the distal CBD. Choledochotomy is performed for 2-3 cm to the lateral border of the duodenum. Anastomosis is performed with interrupted absorbable sutures. The biggest complication that can occur is sump syndrome caused by food or other debris trapped in the distal part of CBD[140]; its management is endoscopic with ERCP/ES. Another option may be choledochidjejunostomy with a roux-en-Y loop, but performed by expert hands.

Lithotripsy

Lithotripsy could be considered the ideal management of CBDS, as it resolves the disease without interruption of the CBD wall and without performing a sphincterotomy. However, this technique cannot be considered definitive in the treatment of cholecysto-choledocholithiasis since the genesis of the stones is secondary to the lithogenic bile in the gallbladder, and for this reason the recurrence rate would be very high. Fragmentation of gallbladder stones would increase the percentage of their migration into the choledochus. Another advantage of this technique is certainly that of being performed in a single application. Lithotripsy is not able to avoid cholecystectomy but it can be a valid therapeutic alternative in those patients already cholecystectomized or for whom it is not indicated. However, it cannot be overlooked that lithotripsy requires dedicated instrumentation and skilled personnel, which are not always available, thus limiting its diffusion. There are various approaches described for stone fragmentation: Mechanical, electrohydraulic, laser, and extracorporeal shock wave[141-143].

Endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy is usually performed after failed endoscopic sphincterotomy for CBDS through a Dormia basket or balloon catheter. CBD clearance is reached in about 80%-90% of cases[143]. Failure may be due to CBDS size exceeding 3 cm, since stones could not be captured, and stone impaction in the CBD[144].

Endoscopic electrohydraulic lithotripsy may be used in cases of difficult CBDS. A large operating channel accommodates a 4.5 Fr calibre probe with an electrohydraulic shock wave generator sending high-frequency hydraulic pressure waves. In order not to cause damage to the surrounding tissue, the probe must be positioned as close as possible to the stone. The stone removal rate ranges from 74% to 98%[145,146]. This procedure requires costly and fragile instrumentation and good coordination of two skilled endoscopists.

Endoscopic laser lithotripsy has been used to fragment large stones under fluoroscopic visualization, because of the risk of heat-induced biliary damage[147]. Today, single-operator steerable cholangioscopy allows the safer use of laser lithotripsy with direct vision[148]. A removal rate of CBDS has been reported of about 93%-97%, with a complications rate of 4%-13%[149,150]. The holmium laser is the newest one, but its use is very expensive[151]. Laser lithotripsy has recently been proposed with laparoscopic, open surgery, or percutaneously approaches.

Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy is also used in cases of difficult CBDS with US or fluoroscopic guidance. Modern lithotriptors employ water-filled compressible bags; because of the discomfort experienced by the patient, general anaesthesia is often required. Contraindications to this technique are portal thrombosis and varices of the umbilical plexus, and it can also cause adverse events, such as transient biliary colic, subcutaneous ecchymosis, cardiac arrhythmia, self-limited haemobilia, cholangitis, ileus, and pancreatitis[152,153]. More sessions are typically required. The recurrence rate during a 1-2 year follow-up period is about 14%[154]. Currently, extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy is not considered the first-line treatment for difficult bile duct stones[155].

CONCLUSION

Management of cholelithiasis with choledocholithiasis must be conducted appropriately. A delay in the diagnosis of this pathological condition can increase morbidity and mortality. Unlike other diseases that have a certain diagnosis, the presence of stones in the CBD is sometimes only suspicious. Historically, diagnosis was achieved through a careful association between clinical symptoms, serology, and radiological images. Today, the development of new radiological imaging, interventional endoscopy, and laparoscopy techniques has allowed us to arrive at a faster and more accurate diagnosis. The management of cholelithiasis with choledocholithiasis has become multidisciplinary, and more professional figures are involved (radiologists, gastroenterologists, endoscopists, and surgeons), and will be increasingly adapted not only to a specific patient but also to the available resources of a specific environment in order to have the best possible management. However, endoscopy and surgery always retain a central diagnostic and therapeutic role.

Many studies and meta-analyses have been conducted by various authors regarding the comparison between one-session and two-session treatments for patients with concomitant gallbladder and CBD stones[17,31,76,92,156,157]. The findings have shown equivalent success rates, postoperative morbidity, stone clearance, mortality, conversion to other procedures, total operation time, and failure rate, but one-session treatment is characterized by a shorter hospital stay and more cost benefits[158]. Consequently, the latter option, when local resources and expertise are available, should be offered as a treatment of choice. However, in cases of incomplete or difficult removal of CBDSs, other additional techniques can also be used, which can be of valuable help in selected patients.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests for this article.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: The European Association of Endoscopic Surgery; Società Italiana di Chirurgia Endoscopica e nuove Tecnologie; Associazione dei Chirurghi Ospedalieri Italiani; and Associate of American College of Surgeons.

Peer-review started: January 24, 2021

First decision: March 7, 2021

Article in press: June 25, 2021

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Azzam AZ, Chen T, Matsubara S, Saito H S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li JH

Contributor Information

Pasquale Cianci, Department of Surgery and Traumatology, Hospital Lorenzo Bonomo, Andria 76123, Italy. ti.oiligriv@1codicnaic.

Enrico Restini, Department of Surgery and Traumatology, Hospital Lorenzo Bonomo, Andria 76123, Italy.

References

Articles from World Journal of Gastroenterology are provided here courtesy of Baishideng Publishing Group Inc

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/111546790

Smart citations by scite.ai

Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been

supported or disputed.

https://scite.ai/reports/10.3748/wjg.v27.i28.4536

Article citations

Diagnostic value of T-tube cholangiography and choledochoscopy in residual calculi after biliary surgery.

BMC Gastroenterol, 24(1):383, 28 Oct 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39468442 | PMCID: PMC11514883

Emodin repairs interstitial cells of Cajal damaged by cholelithiasis in the gallbladder.

Front Pharmacol, 15:1424400, 18 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39359250 | PMCID: PMC11445038

Investigating causal links between gallstones, cholecystectomy, and 33 site-specific cancers: a Mendelian randomization post-meta-analysis study.

BMC Cancer, 24(1):1192, 27 Sep 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39333915 | PMCID: PMC11437614

One-Stage Intraoperative ERCP combined with Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Versus Two-Stage Preoperative ERCP Followed by Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy in the Management of Gallbladder with Common Bile Duct Stones: A Meta-analysis.

Adv Ther, 41(10):3792-3806, 29 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39207666

Percutaneous transhepatic papillary ballooning and extraction for common bile duct stones: a single-center experience.

Quant Imaging Med Surg, 14(9):6613-6620, 12 Aug 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 39281154 | PMCID: PMC11400688

Go to all (43) article citations

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Laparoscopic-endoscopic rendezvous versus preoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy in people undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy for stones in the gallbladder and bile duct.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 4:CD010507, 11 Apr 2018

Cited by: 15 articles | PMID: 29641848 | PMCID: PMC6494553

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev, (9):CD003327, 03 Sep 2013

Cited by: 57 articles | PMID: 23999986

Review

Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev, (12):CD003327, 12 Dec 2013

Cited by: 57 articles | PMID: 24338858 | PMCID: PMC6464772

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Mini-Invasive management of concomitant gallstones and common bile duct stones : where is the evidence ( Review article).

Tunis Med, 97(8-9):997-1004, 01 Aug 2019

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 32173848

Review