Abstract

Free full text

Chlamydomonas proteases: classification, phylogeny, and molecular mechanisms

Abstract

Proteases can regulate myriad biochemical pathways by digesting or processing target proteins. While up to 3% of eukaryotic genes encode proteases, only a tiny fraction of proteases are mechanistically understood. Furthermore, most of the current knowledge about proteases is derived from studies of a few model organisms, including Arabidopsis thaliana in the case of plants. Proteases in other plant model systems are largely unexplored territory, limiting our mechanistic comprehension of post-translational regulation in plants and hampering integrated understanding of how proteolysis evolved. We argue that the unicellular green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii has a number of technical and biological advantages for systematic studies of proteases, including reduced complexity of many protease families and ease of cell phenotyping. With this end in view, we share a genome-wide inventory of proteolytic enzymes in Chlamydomonas, compare the protease degradomes of Chlamydomonas and Arabidopsis, and consider the phylogenetic relatedness of Chlamydomonas proteases to major taxonomic groups. Finally, we summarize the current knowledge of the biochemical regulation and physiological roles of proteases in this algal model. We anticipate that our survey will promote and streamline future research on Chlamydomonas proteases, generating new insights into proteolytic mechanisms and the evolution of digestive and limited proteolysis.

Introduction

Proteolytic enzymes, or proteases, catalyse the cleavage of peptide or isopeptide bonds in proteins. Proteases likely arose early in evolution as merely digestive enzymes necessary for protein degradation and the generation of amino acids in primitive organisms (López-Otín and Bond, 2008). However, apart from being blunt protein distractors, proteases can also act akin to sharp suture scissors by dissecting target polypeptide chains at precise locations into smaller polypeptides, in a process called ‘limited proteolysis’. The result of limited proteolysis is the formation of new post-translationally modified protein species or proteoforms with neo-N- and/or -C-termini (Weng et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020), which may gain, lose, or show altered biochemical activity compared with their precursor proteins. The actual role and importance of limited proteolysis appears to be greatly underestimated, as it may in fact control myriad biological processes, ranging from seed development and photosynthesis in plants to apoptotic cell death and blood clotting in animals. Acting in a cooperative manner, digestive and limited proteolysis sustain continuous modification of the proteome necessary for normal development and fitness (Minina et al., 2017).

While up to 3% of eukaryotic genes encode proteases that collectively represent the protease degradome of a given organism (Quesada et al., 2008), only a small fraction of proteases are mechanistically understood. This is especially true for plants, where most of the knowledge on proteases is derived from the model organism Arabidopsis thaliana (van der Hoorn, 2008). Still, the majority—approximately 86%—of the protease holotypes in Arabidopsis remain uncharacterized biochemically and are known only as sequences (Rawlings, 2020). The monophyletic clade of green plants, consisting of both land plants and green algae, is divided into two evolutionary lineages, the Chlorophyta (chlorophytes) and Streptophyta (streptophytes), that diverged over a billion years ago (Bremer, 1985; Morris et al., 2018). Chlorophyte proteases are largely unknown territory, which limits our mechanistic comprehension of the role of proteolytic mechanisms in plant biology and hampers integrated understanding of how proteolysis evolved.

With these thoughts in mind, we turned our attention to proteolytic enzymes of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (hereafter Chlamydomonas), an ancient unicellular model organism belonging to the Chlorophyta that shares ancestral traits not only with higher plants but also with animals. Thus, Chlamydomonas has been an invaluable reference for studies in the areas of light perception, photosynthesis, chloroplast development, ciliary formation, cell motility, and the cell cycle, among others (Harris, 2001). Whereas the haploid genome of Chlamydomonas expedites functional analysis of genes and proteins of interest, this research is often hindered by the low efficiency of nuclear transgene expression (Salomé and Merchant, 2019). Although the establishment of insertional mutant libraries (Li et al., 2016; Cheng et al., 2017) has aided in some cases, mutants for most genes are still unavailable due to insertion in non-coding regions or a lack of insertion. However, more recent developments of cloning technology (Crozet et al., 2018; Emrich-Mills et al., 2021) and genome editing in Chlamydomonas (Picariello et al., 2020), along with the emerging understanding of transgene silencing mechanisms (Neupert et al., 2020) in Chlamydomonas, should facilitate the functional analysis of various genes of interest in this model alga.

In multicellular plants, a search for protein substrates whose cleavage by a specific protease would be central to its biological function is significantly hampered by the difficulties in standardizing protein terminomics experiments, due to the complex cellular heterogeneity within the samples used for proteome isolation. Along with the inherent differences in cell physiology and morphology among diverse cell types and tissues that contribute to the variation in the expression, compartmentalization, and activation of a specific protease, there is also responsiveness to both experimental conditions and proteome isolation treatments to consider (Demir et al., 2018; Dissmeyer et al., 2018). In contrast, Chlamydomonas represents a beneficial model system for protease substrate identification by virtue of its limited number of cell types and the possibility of synchronizing the cell cycle and response to external factors within a homogenous cell population.

We argue that the simple unicellular life cycle of Chlamydomonas, coupled with the ease of cell phenotyping and the above-mentioned genetic and technical advantages, provide a powerful paradigm for systematic studies of proteases and proteolytic pathways. Here, we share a genome-wide survey and classification of Chlamydomonas proteases, compare proteases in Chlamydomonas and in Arabidopsis by catalytic type, and classify Chlamydomonas proteases based on their relatedness to major taxonomic groups. Furthermore, we summarize and discuss the available evidence for biochemical regulation and/or physiological roles of proteases in Chlamydomonas.

Protease degradome of Chlamydomonas versus Arabidopsis

According to the nature of the nucleophile acting during catalysis, proteases are divided into seven major catalytic types: (i) aspartic, (ii) cysteine, (iii) glutamate, (iv) serine, and (v) threonine proteases, as well (vi) metalloproteases and (vii) asparagine peptide lyases. In addition, there are proteases classified as ‘unknown’ and of a ‘mixed catalytic type’ (Rawlings, 2020). While glutamate proteases and asparagine peptide lyases are found only in pathogenic fungi, bacteria, and archaea, the other types of proteases are spread through all domains of life (Jensen et al., 2010; Rawlings et al., 2011).

We used the major database of proteolytic enzymes, MEROPS, release 12.2 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/merops/index.shtml) and the Chlamydomonas genome annotation, version 5.5 (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html#!info?alias=Org_Creinhardtii), to retrieve all protease genes and classify the encoded proteins in comparison with Arabidopsis proteases from both MEROPS and TAIR (https://www.arabidopsis.org/). Altogether, 352 and 764 protease-encoding genes constitute the Chlamydomonas and Arabidopsis degradomes, respectively (Tables S1 and S2 at Zenodo; https://zenodo.org/record/5347045#.YS46It-xWUk, Zou and Bozhkov, 2021).Table 1 shows the distribution of Chlamydomonas and Arabidopsis proteases among catalytic types. One striking difference between the two species is the predominant occurrence of metalloproteases in Chlamydomonas, accounting for ~35% of its degradome (versus only ~15% in Arabidopsis). Notably, more than one-third of the Chlamydomonas metalloproteases (45 out of 124, or ~13% of the whole degradome) belong to the gametolysin family M11, which is absent in Arabidopsis (Fig. 1) and other higher plants. The main role of gametolysin is algal cell-wall degradation to release gametes of both mating types as a necessary prelude to gamete fusion (Matsuda, 2013).

Table 1.

Number of protease genes in Chlamydomonas and Arabidopsis

| Catalytic type | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Aspartic | Cysteine | Metallo | Serine | Threonine | Unknown | Total |

| Chlamydomonas | 10 (2.8%) | 95 (27.0%) | 124 (35.2%) | 104 (29.5%) | 18 (5.1%) | 1 (0.3%) | 352 (100%) |

| Arabidopsis | 91 (11.9%) | 172 (22.5%) | 117 (15.3%) | 313 (41.0%) | 26 (3.4%) | 48 (5.9%) | 764 (100%) |

Hierarchical distribution of protease-encoding genes among different clans and families in Chlamydomonas and in Arabidopsis. U, uncharacterized.

By contrast, there are relatively more aspartic and serine proteases in Arabidopsis than in Chlamydomonas (Table 1), that is, ~12% and ~41% versus ~2.8% and ~30% of the respective degradomes. This is mainly due to the extensive A1 (pepsin-like; 69 homologues) and S33 (prolyl aminopeptidases; 76 homologues) families in Arabidopsis, which are represented by only a few homologues in Chlamydomonas (Fig. 1). In higher plants, the considerable expansion of A1 and S33 proteases may correlate with the specific developmental stages or a plethora of biotic and abiotic stresses that a plant must withstand given its sessile lifestyle (in comparison with motile aquicolous unicellular algae such as Chlamydomonas). For example, a typical pepsin-like A1 protease, constitutive disease resistance 1 (CDR1), elevates the plant resistance to Pseudomonas syringae (Xia et al., 2004), whereas a member of the same family, promotion of cell survival 1 (PCS1), is essential for embryogenesis (Ge et al., 2005). Another example is the prolyl aminopeptidase AtPAP1, which underlies Arabidopsis tolerance to salt stress and drought (Sun et al., 2013).

Another interesting difference between the degradomes of the two species is the complete absence of certain protease families in one of them. The Chlamydomonas degradome is devoid of aspartic protease family A11 (copia transposon endopeptidase), threonine protease family T2 (glycosylasparaginase precursor), and metalloprotease families M10 (matrixin), M102 (DA1 peptidase), M49 (dipeptidyl-peptidase III, also known as nudix hydrolase 3), and M38 (isoaspartyl dipeptidase), which are represented by one (M49) or more homologues in Arabidopsis (Fig. 1). The presence of the M10 family in Arabidopsis might be associated with defence against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens (Zhao et al., 2017), whereas proteases among the M102 family members are known to be involved in organ size control (Vanhaeren et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017b). In contrast to land plants, the mobile unicellular green algae are capable of evading potential pathogens.

Together with the above-mentioned family M11 (gametolysin), Arabidopsis also lacks the cysteine protease families C11 (clostripain) and C45 (acyl-coenzyme A:6-aminopenicillanic acid acyl-transferase precursor), metalloprotease family M32 (carboxypeptidase), and serine protease family S77 (prohead endopeptidase), which are all present in Chlamydomonas (Fig. 1). However, information about the role of these proteases in the algal life cycle is still lacking.

In contrast to frequently observed gene duplication events, and hence gene redundancy, in higher plants, including Arabidopsis, Chlamydomonas has a simpler genome with much less frequent gene duplications (Merchant et al., 2007). This is also true for protease-encoding genes. Indeed, among 58 protease families present in both Chlamydomonas and Arabidopsis, 41 (~71%) families have more genes per family in Arabidopsis than in Chlamydomonas (Fig. 1). One representative example is family C14, the metacaspases. There are nine metacaspase genes, AtMC1–AtMC9, in Arabidopsis, which are further split into two structurally distinct types, I and II, represented by three (AtMC1, 2, and 3, or AtMCA-Ia, b, and c according to new nomenclature) and six (AtMC4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9, or AtMC-IIa, b, c, d, e, and f) homologues, respectively (Tsiatsiani et al., 2011; Minina et al., 2020). Notably, four type II metacaspase genes, AtMCA-IIa, b, c, and d (formerly named AtMC4, 5, 6, and 7) are products of tandem duplication and are located next to each other within a region of 10.6 kb on Arabidopsis chromosome 1. Additionally, the AtMCA-IIe (AtMC8) gene situated on the same chromosome is related to the tandem repeat of those four genes by a second internal duplication event (Vercammen et al., 2004). This duplication of type II metacaspase genes in Arabidopsis makes it difficult to decipher the whole spectrum of their mechanistic roles and to distinguish between redundant and individual gene-specific functions. In contrast, the Chlamydomonas genome encodes only one member of each type of metacaspase (CrMCA-I and CrMCA-II; Fig. 1), offering an ideal system for studying the ancestral roles of these proteolytic enzymes.

Interestingly, some protease genes are also found duplicated in Chlamydomonas, suggesting that those gene duplication events likely occurred after divergence from its ancestor shared with higher plants. For example, while Arabidopsis has a single-copy gene encoding Deg1 (for Degradation of periplasmic proteins) protease belonging to the Deg/HtrA (for High temperature requirement A) family (S1), its Chlamydomonas orthologue is represented by three copies (Schuhmann et al., 2012). Based on these facts, we conclude that most of the proteases in Chlamydomonas are encoded by single-copy genes, offering a valuable model for genetic studies.

Phylogenetic relatedness of Chlamydomonas proteases

As green algae are believed to share a common ancestor with higher plants, and Chlamydomonas shares some features (e.g. cilia) with animals (Merchant et al., 2007), we wondered how such evolutionary versatility affected the phylogenetic relatedness of the Chlamydomonas degradome as a whole. In this analysis, Chlamydomonas protease sequences were used as queries to search against a non-redundant protein database of the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The protein sequences sharing high similarity (E value <10–10) were collected for calculating the relative distance through phylogenetic analysis. Based on the closest homologues to algal proteins, all Chlamydomonas proteases were classified into six types: animal, animal and plant, plant, bacterial, green algal, and unclassified (Table S1 at Zenodo). Thus, plant-type proteases are the ones that are most similar to homologues from higher plants, and the same principle determines the ontology of other types, except that animal-and-plant-type proteases are close to the cluster consisting of both animal and plant homologues.

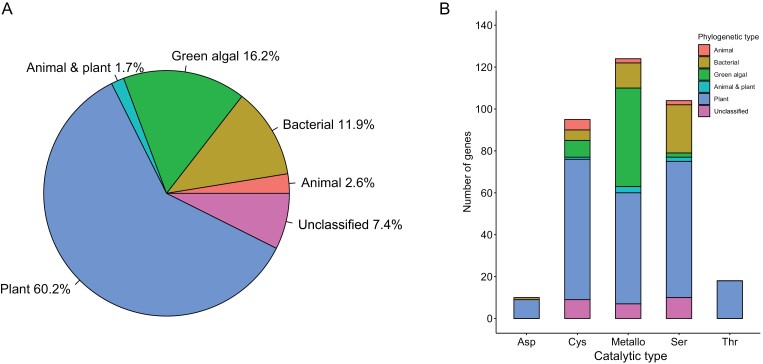

The most abundant (~60%) of Chlamydomonas proteases are of a plant type, followed by green algal type (~16%), and bacterial type (~12%), whereas animal-type along with animal-and-plant-type proteases jointly constitute 4.3% of the Chlamydomonas degradome (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, 7.4% of the Chlamydomonas proteases (26 protein sequences) cannot be ascribed to any phylogenetic type, because they exhibit too high divergence with homologous protein sequences. However, the distribution of all Chlamydomonas proteases into various phylogenetic types presented above does not hold for individual catalytic types. Indeed, all threonine proteases (mostly proteasome subunits) and the vast majority (90%) of aspartic proteases of Chlamydomonas are of the plant type (Fig. 2B). The plant type also predominates among cysteine proteases (~71%), whereas surprisingly large proportions of the metallo- and serine proteases belong to the green algal (~38%) and bacterial (~22%) types, respectively. Finally, the animal type is most frequently found among cysteine proteases (~5.3%; Fig. 2B).

Biochemistry and physiological role of proteases in Chlamydomonas

Animal-type proteases

Nine Chlamydomonas proteases are closely related to animal homologues (Table S1 at Zenodo), but none has been systemically studied to date. However, one zinc carboxypeptidase whose homologues are found in ciliated organisms and not in higher plants was originally discovered in the Chlamydomonas ciliary and basal body proteome (gene locus: Cre13.g572850; Li et al., 2004). Despite divergence more than 109 years ago, Chlamydomonas and animals have structurally and functionally similar cilia (Silflow and Lefebvre, 2001). Therefore, the close relationship of proteases involved in cilia formation or function between Chlamydomonas and animals is not surprising. Based on the notion that algal genes might have contributed to the common ancestor of animal genomes via horizontal gene transfer (HGT) (Sun et al., 2010a; Ni et al., 2012), we cannot rule out the possibility that Chlamydomonas genes encoding animal-type proteases were adopted by the animal ancestor and are conserved in extant animal species. Future work on these animal-type proteases will expedite our understanding of their role in cilia formation and activity, or of specific ancestral traits conserved between green algae and animals.

Plant-type proteases

Plant-type proteases are the most abundant in Chlamydomonas (Fig. 2A), and many are related to the proteasomal and/or organellar protein quality control pathways (Table S1 at Zenodo). Among them are the evolutionarily conserved Filamentation temperature-sensitive H (FtsH), Caseinolytic protease proteolytic subunit (ClpP), DegP, and Lon proteases, which are localized in the chloroplast and/or the mitochondrion and are well known for their role in maintaining organelle homeostasis (Schuhmann and Adamska, 2012; Pinti et al., 2016; Kato and Sakamoto, 2018; Bouchnak and van Wijk, 2021). They digest misfolded proteins and protein aggregates induced by environmental stresses and thus have loose substrate cleavage preference, making substrate specificity screening a challenging task. The ubiquity of these proteases in bacteria and their chloroplastic and/or mitochondrial localization point to their inheritance as a consequence of endosymbiosis, whereas their close intraorganellar co-localization allows them to work cooperatively to degrade common substrates. For example, the cleavage of D1 protein (a core protein in photosystem II) by DegP facilitates subsequent degradation by FtsH under photoinhibitory conditions in Arabidopsis (Kato et al., 2012). Additionally, both ClpP and FtsH degrade the cytochrome b6f complex during nitrogen starvation in Chlamydomonas, although FtsH plays a major role (Majeran et al., 2000; Malnoë et al., 2014; Wei et al., 2014). In the following sections, we consider individual Chlamydomonas proteases with close phylogenetic relationships to homologues from higher plants for which biochemical and/or functional data are available.

FtsH1

FtsH is an evolutionarily conserved ATP-dependent zinc-binding metalloprotease (family M41) that is anchored to the chloroplastic or mitochondrial membrane in higher plants and algae. Most prokaryotes encode only one FtsH, whereas eukaryotes generally have several FtsH isoforms, with twelve and six found in Arabidopsis and Chlamydomonas, respectively. Chlamydomonas has close orthologues to all Arabidopsis FtsH proteases except FtsH12 (Table S3 at Zenodo). In addition to the proteolytically active FtsH isoforms, Arabidopsis and Chlamydomonas respectively possess five and three FtsH-like proteins (FtsHi1–FtsHi5 in Arabidopsis), which lost the conserved zinc-binding motif and are presumably catalytically dead (Table S3 at Zenodo). While Arabidopsis FtsH-like proteins are involved in maintaining cellular redox balance (Wang et al., 2018), seedling establishment, and Darwinian fitness in semi-natural conditions (Mishra et al., 2019), the role of their Chlamydomonas homologues remains unknown.

It was shown that Chlamydomonas FtsH1 and FtsH2 were localized at the thylakoid membrane and formed a hetero-oligomer with a molecular mass exceeding 1 MD (Malnoë et al., 2014). The mutation of a conserved arginine residue in the ATPase domain of FtsH1 prevents the integration of the FtsH1/FtsH2 dimer into large supercomplexes and impairs their catalytic activity of degrading photosynthetic membrane protein D1 and cytochrome b6f complex (Malnoë et al., 2014; Table 2). In addition, the dimerization and oligomerization of FtsH1 and FtsH2 are redox-regulated at the intermolecular disulfide bridges formed between as yet unknown cysteine residues (Wang et al., 2017a). Research in higher plants revealed that the FtsH supercomplex in thylakoid membranes has a major role in photosystem II repair and the biosynthesis of photosystem I (reviewed in Kato and Sakamoto, 2018). However, studies of FtsH proteases in Chlamydomonas extend their role to degrading cytochrome b6f complex (Malnoë et al., 2014), in this way connecting carbon fixation and ATP synthesis.

Table 2.

Proteases functionally characterized in Chlamydomonas

| Protease | Gene locus | Clan | Family | Biological role | Substrates | Functional analysis | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATG4 | Cre12.g510100 | CA | C54 | Autophagy | ATG8 | Chemical modulation | Pérez-Pérez et al., 2016 |

| ClpP1 | CreCp.g001500 | SK | S14 | Chloroplast protein homeostasis | Cytochrome b6f complex, ATP synthase, Rubisco | Reverse genetics | Ramundo et al., 2014; Majeran et al., 2019, 2000 |

| DegP1C | Cre12.g498500 | PA | S1 | Chloroplast protein homeostasis | D1 | Reverse genetics | Schuhmann et al., 2012; Theis et al., 2019 |

|

FtsH1

FtsH2 | Cre12.g485800 Cre17.g720050 | MA | M41 | Chloroplast protein homeostasis | D1, cytochrome b6f complex | Reverse genetics | Malnoë et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2017a |

| Gametolysin | Cre17.g718500 | MA | M11 | Gamete cell wall lysis | Proline- and hydroxyproline-rich proteins | Chemical modulation | Matsuda et al., 1990; Matsuda, 2013 |

| SMT7 | Cre16.g692600 | CE | C48 | Cell division | SUMOylated RPL30 | Reverse genetics | Lin et al., 2020 |

| Sporangin | Cre01.g049950 | SB | S8 | Sporangial cell wall lysis | Sporangial cell wall proteins | Chemical modulation | Matsuda et al., 1995; Kubo et al., 2009 |

ClpP1

The Clp complex shares both functional and structural similarities with the proteasome (Yu and Houry, 2007). The complex in Arabidopsis consists of three components: proteases, chaperones, and modulators (Peltier et al., 2004). The proteases include six catalytically active ClpPs (AtClpP1–6) and four regulatory ClpP-like proteins (ClpRs; AtClpR1–4) lacking the catalytic residues for peptide bond hydrolysis, and all ten of these proteins are classified into family S14. Among them, AtClpP2 forms a single homotetradecameric complex in the mitochondrion, while the others are components of the plastidic ClpP protease core (Peltier et al., 2004), which is essential for chloroplast development at embryonic and post-embryonic stages. Moreover, mutations of several Clp genes (AtClpP3, AtClpP4, AtClpP5, AtClpR2, and AtClpR4) in Arabidopsis are lethal at the embryo or seedling stage (summarized in Olinares et al., 2011).

Based on the presence of a conserved Ser-His-Asp catalytic triad, sequence similarity, and phylogeny (Fig. S1 at Zenodo), four ClpP genes (CrClpP1, CrClpP2, CrClpP3, and CrClpP5) and four ClpR genes (CrClpR1–4) are present in the Chlamydomonas genome (Table S3 at Zenodo). In addition, one Clp homologue, CrClpR6 (gene locus Cre06.g299650), clusters closely with AtClpP6, despite missing a catalytic histidine (Fig. S1 at Zenodo) and hence being predicted to lack enzymatic activity (Majeran et al., 2005). Although ClpP family members are highly conserved among species (Yu and Houry, 2007), CrClpP1, as well as homologues from close Chlorophyceae relatives, contain a 30 kD insertion that is absent in ClpP homologues from other organisms (Huang et al., 1994; Derrien et al., 2009). This insertion can be cleaved to generate a short ClpP1 isoform (Majeran et al., 2005), albeit both the long and short CrClpP1 are found within the ClpP protease core (Huang et al., 1994; Derrien et al., 2009).

A failure to obtain ClpP mutants in green plants suggests an indispensable role for this protease complex. The function of CrClpP1 was investigated by taking advantage of a repressible chloroplast gene expression system in Chlamydomonas (Ramundo et al., 2013). It has been found that gradual depletion of CrClpP1 impairs chloroplast morphology and induces autophagy via an unknown retrograde signalling mechanism (Ramundo et al., 2014; Ramundo and Rochaix, 2014). Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses of crclp1-deficient strains revealed 16 potential chloroplastic substrates (Ramundo et al., 2014) but failed to detect components of the cytochrome b6f complex (Majeran et al., 2000) and two additional recently identified substrates: small subunits of Rubisco and non-assembled subunits of ATP synthase (Majeran et al., 2019; Table 2).

DegP1C

The DegP/HtrA family (S1) members contain an N-terminal trypsin-type protease domain and at least one C-terminal PDZ (from Post synaptic density protein, Drosophila disc large tumor suppressor, and Zonula occludens-1) domain (Clausen et al., 2002). The Arabidopsis genome encodes 16 DegP/HtrA family members (DegP1–DegP16) with different intracellular localizations (Table S3 at Zenodo). The ‘core set’ of DegP proteases typical for green plants includes thylakoid lumen-localized DegP1, DegP5, and DegP8, chloroplast stroma-localized DegP2 and DegP7, nucleolus-localized DegP9, peroxisome-localized DegP15, and mitochondrion-localized DegP10 (Schuhmann et al., 2012). Interestingly, chloroplast-localized DegP proteases are involved in the photosystem II repair cycle by degrading D1 protein at different sites (Kapri-Pardes et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2007, 2010b; Knopf and Adam, 2018).

The Chlamydomonas genome encodes 15 DegP proteins, including duplicated DegP1 isoforms (DegP1A, B, and C). In vitro data show that the proteolytic activity of Arabidopsis DegP1 and Chlamydomonas DegP1C is redox-regulated and pH-dependent (Chassin et al., 2002; Ströher and Dietz, 2008; Kley et al., 2011; Theis et al., 2019), and that DegP1C activity is also regulated by temperature (Theis et al., 2019). In Arabidopsis, high light and heat stress were shown to enhance the transcript and protein levels of DegP1, respectively (Itzhaki et al., 1998; Sinvany-Villalobo et al., 2004). Likewise, Chlamydomonas DegP1C is induced at both the protein and the transcript level by various stresses, such as sulphur and phosphorus starvation and heat stress (Zhang et al., 2004; Moseley et al., 2006; Schroda et al., 2015; Theis et al., 2019). In Arabidopsis, DegP1 knockdown lines exhibit suppressed growth, earlier flowering, and high photoinhibition sensitivity (Kapri-Pardes et al., 2007); however, a Chlamydomonas degp1c knockout mutant shows no discernible phenotype under both normal and stress (high light or heat) conditions (Theis et al., 2019), pointing to functional redundancy of the DegP1 isoforms in the alga. Quantitative shotgun proteomics have identified 115 proteins, which are significantly enriched in the Chlamydomonas degp1c mutant compared with the wild type, indicating that they are potential substrates of DegP1C (Theis et al., 2019). Among them are all subunits of the cytochrome b6f complex (Table 2), which are known substrates of FtsH and ClpP proteases (Majeran et al., 2000; Malnoë et al., 2014; Wei et al., 2014).

Lon

The Lon protease is named after the long filament phenotype of a corresponding bacterial mutant. Prokaryotes and unicellular eukaryotes have a single, mitochondrion-localized Lon, whereas multicellular eukaryotes often contain an extra peroxisomal copy (Tsitsekian et al., 2019). There are four genes encoding Lon isoforms (AtLon1–4) in Arabidopsis. AtLon1 plays an essential role in mitochondrial protein homeostasis (Li et al., 2017), and its deficiency leads to post-embryonic growth retardation, aberrant mitochondrial morphology, and impaired respiration (Rigas et al., 2009; Solheim et al., 2012). The peroxisome-localized AtLon2 facilitates protein import into the matrix and matrix protein degradation to sustain peroxisomal function (Lingard and Bartel, 2009; Farmer et al., 2013). Accordingly, a deficiency of AtLon2 inhibits growth and enhances the autophagic clearance of peroxisomes (pexophagy; Farmer et al., 2013; Bartel et al., 2014). The functions of AtLon3 and AtLon4 remain unknown.

Chlamydomonas has a single mitochondrial Lon (Cre06.g281350), which is absent from the MEROPS database at the time of this writing. The expression level of CrLon is high during light periods and low at night, suggesting a potential light-dependent or circadian mechanism (Zones et al., 2015; Fig. S2 at Zenodo). In contrast, the expression of all four AtLon1–4 genes in Arabidopsis is relatively stable during a 12 h light:12 h dark cycle (Ng et al., 2019; Fig. S2 at Zenodo). While no genetic evidence for CrLon is available, the above data point to divergent regulatory mechanisms of Lon expression in the chlorophyte and angiosperm lineages.

Chlapsin

Chlapsin (Cre04.g226850) is the only studied aspartic-type protease from Chlamydomonas. It belongs to family A1, and features a modified catalytic motif DTG/DSG in contrast to the DTG/DTG typical for A1 family members from higher plants (Almeida et al., 2012). Most aspartic proteases from higher plants are localized in the lytic vacuoles and apoplast, and are active under acidic conditions (Simões and Faro, 2004). While chlapsin shares a requirement for low pH with the higher-plant homologues, it is localized to the chloroplast (Almeida et al., 2012), presumably reflecting different functions. Notably, overexpression of the chlapsin orthologue AtAPA1 confers drought resistance in Arabidopsis (Sebastián et al., 2020), but whether this observation might be relevant to the response of Chlamydomonas living in a humid environment to osmotic stress (Meijer et al., 2001) is still unknown.

ATG4

Autophagy is a conserved catabolic process in eukaryotes for recycling cytoplasmic components and membrane-bound organelles. This process is regulated by ATG (for AuTophaGy-related) proteins and entails the fusion of double-membrane vesicles (termed autophagosomes) that can carry various types of cargo, with lysosomes in animals or lytic vacuoles in fungi and plants (Klionsky et al., 2021; Yoshimoto and Ohsumi, 2018). Formation of the autophagosome is reliant on the ATG8 and ATG12 ubiquitin-like conjugation systems (Mizushima, 2020). Cysteine protease ATG4 (family C54), the only proteolytic enzyme among all known ATG proteins, cleaves the nascent ATG8 at a conserved C-terminal glycine to allow the subsequent conjugation of ATG8 to phosphatidylethanolamine, a necessary step for anchoring ATG8 in the autophagosomal membrane. In addition, ATG4 possesses delipidating activity and can cleave the amide bond between phosphatidylethanolamine and ATG8 for the deconjugation and potential reuse of ATG8 (Abreu et al., 2017; Kauffman et al., 2018).

In Arabidopsis, there are two ATG4 isoforms, ATG4a and ATG4b, with the former isoform being more efficient in processing all nine ATG8 protein family members (Woo et al., 2014). Similar to mammalian and yeast ATG4 (Pérez-Pérez et al., 2014; Scherz-Shouval et al., 2007), the proteolytic activity of both Arabidopsis ATG4 isoforms was shown to be reversibly inhibited by oxidation (Woo et al., 2014). However, the molecular details of this redox regulation and its role in the context of plant autophagy remained unknown. In fact, Chlamydomonas research carried out in the laboratory of José Luis Crespo was pivotal for advancing mechanistic understanding of the redox regulation of ATG4, as a part of the autophagy process (for a recent review, see Pérez-Pérez et al., 2021). In particular, it has been found that a single Chlamydomonas ATG4 shares a conserved cysteine (Cys-400), which is absent in the homologues from higher plants, with the yeast ATG4 for redox regulation (Pérez-Pérez et al., 2016). Thus, the proteolytic activity of ATG4 is tightly associated with the cellular environment, with ATG4 shuttling between three major reversible states depending on the redox conditions and the intracellular redox state. In the reduced condition, ATG4 predominantly exists as a catalytically active monomer. The increase in the intracellular redox potential induces the formation of a single disulfide bond at the regulatory Cys-400 residue that inhibits the activity of monomeric ATG4. As the redox potential increases further, the ATG4 monomers oligomerize to form aggregates devoid of proteolytic activity (Pérez-Pérez et al., 2016). Similarly, in animals, ATG4 oligomerization is also triggered by reactive oxygen species production during LC3 (ATG8 orthologue in animals)-associated phagocytosis; the aggregation of ATG4 proteins inhibits their LC3-delipidation activity (Ligeon et al., 2021). In summary, environmental signals affect the intracellular redox changes, leading to the variation of ATG4 conformation and activity. The level of ATG8 and its lipidated form, the main substrates of ATG4, vary accordingly, thus relaying autophagic (in plants) and phagocytic (in animals) activities.

SMT7

Protein SUMOylation, the process of covalent conjugation of small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) proteins to target proteins, is a rapid, dynamic, and reversible post-translational mechanism regulating fundamental cellular processes such as cell proliferation and death, as well as stress responses (Zhao, 2018). SUMO proteases catalyse two major cleavage reactions: (i) C-terminal processing of the neo-synthesized immature SUMO for its maturation, and (ii) deconjugation of SUMO from the SUMOylated proteins for retrieval of a free SUMO (Hickey et al., 2012; Yates et al., 2016).

A recent study by Lin et al. (2020) has made an interesting attempt to connect SUMOylation to cell-cycle control in Chlamydomonas. Chlamydomonas normally performs cell enlargement during a prolonged G1 phase before undergoing multiple cell fission events in a series of rapid alternating S phases and mitoses (S/M), to produce uniform daughter cells (Cross and Umen, 2015). Mating type locus 3 (MAT3), a retinoblastoma protein, controls the Chlamydomonas cell size for commitment to cell division (Umen and Goodenough, 2001). Correspondingly, mat3 mutants initiate cell fission at a smaller size and exhibit extra rounds of S/M, resulting in much smaller cell size than wild type (Umen and Goodenough, 2001). Genetic suppressor screens of the mat3 phenotype identified MAT3 7 (SMT7; Fang and Umen, 2008), one of the six SUMO proteases (family C48) encoded by the Chlamydomonas genome.

There is evidence that catalytic inactivation of proteolytic enzymes by amino acid substitution can slow down dissociation from the substrates without effecting their binding, and thus can be used as a substrate-trapping method (Elmore et al., 2011). Lin et al. (2020) took advantage of this method to search for SMT7 substrates by overexpressing the catalytically inactive SMT7C928A in smt7mat3 double mutants, leading to the identification of ribosomal protein L30 (RPL30) (Lin et al., 2020; Table 2). The authors demonstrated that SMT7 could cleave the SUMO off from the SUMOylated RPL30. The SMT7-dependent deSUMOylation of RPL30 promotes cell division, contributing to the small size of mat3 mutants (Lin et al., 2020), and provides an explanation for the suppression of the small-cell-size defect of mat3 mutants by the SMT7 deficiency (Fang and Umen, 2008). However, the molecular mechanism connecting the SUMOylation and deSUMOylation of RPL30 with cell-cycle control remains unknown.

Green-algal-type and bacterial-type proteases

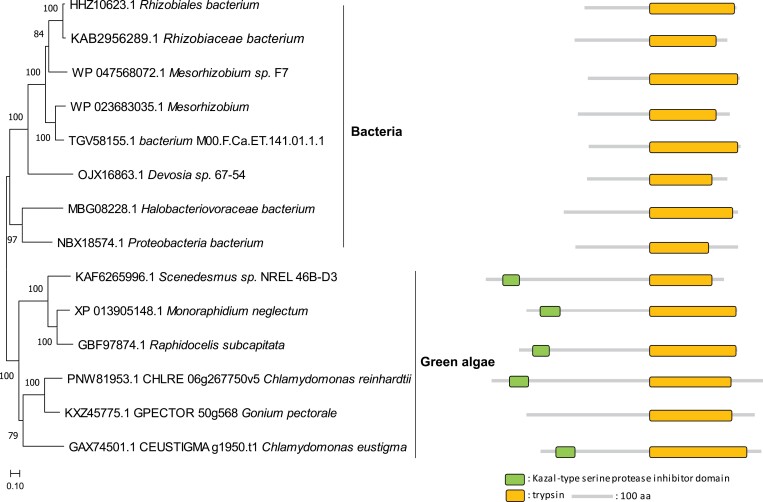

About 16% of all proteases in Chlamydomonas are found exclusively in the green algal lineage (Fig. 2A) and are probably the products of de novo originated genes. Most of the green-algal-type proteases are gametolysin isoforms with conserved zinc-binding sites (Fig. S3 at Zenodo). The remaining 12% of Chlamydomonas proteases have a close relationship with homologues from bacteria (Fig. 2A), pointing to HGT that occurred after the separation between Chlamydomonas and higher plants. Curiously, one Chlamydomonas serine protease from the S1 family (gene locus Cre06.g267750; V8 proteinase) contains a C-terminal trypsin-like domain and an N-terminal Kazal-type serine protease inhibitor domain, while its closest homologues from bacteria contain only the trypsin-like domain (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the Chlamydomonas genome also encodes Kazal-type serine protease inhibitors, small proteins with one or more Kazal domains, each being 40–60 amino acids in length. However, it remains to be seen whether these inhibitors interact with and block the proteolytic activity of the V8 proteinase.

Phylogenetic relationship and domain composition of a trypsin-like peptidase (Cre06.g267750) and related proteases from bacteria and green algae. The search was made against the non-redundant (nr) database from NCBI and protein sequences were used for further alignment and phylogeny analysis. The phylogenetic and domain analyses were performed using MEGA X with the neighbour-joining method (Kumar et al., 2018) and Pfam (El-Gebali et al., 2019), respectively. The scale bar indicates the number of amino acid substitutions per site.

Systematic research on copper regulation in Chlamydomonas identified a Regulator of Sigma-E Protease (RSEP1), closely related to RseP, which is a bacterial membrane metalloprotease involved in transmembrane signalling (Castruita et al., 2011). RSEP1 contains a conserved HExxH motif embedded in a transmembrane helix for metal ion binding. Eukaryotic RSEP1 proteases are found exclusively in Chlamydomonadales, suggesting an early HGT from bacteria. In Chlamydomonas, the expression of RSEP1 is induced by copper depletion in a global copper-sensing transcription factor CRR1-dependent manner (Castruita et al., 2011). It has been suggested that chloroplast-localized RESP1 degrades plastocyanin to release the copper for survival in a copper-deficient environment (Castruita et al., 2011; Kropat et al., 2015), but the genetic evidence for such a role of RESP1 is still missing.

Gametolysin and sporangin

Two cell-wall-digesting proteolytic enzymes, bacterial-type sporangin (family S8 of the SB clan) and green-algal-type gametolysin (family M11 of the MA clan), serve important roles in the accomplishment of Chlamydomonas asexual and sexual cycles, respectively. While sporangins from green algae are closely related to bacterial serine proteases (Fig. S4 at Zenodo) and therefore might be a result of an HGT event, gametolysins are found exclusively in Chlamydomonas and its close but multicellular relative Volvox carteri.

Under favourable growth conditions, Chlamydomonas reproduces itself asexually by fission, when a single mother cell undergoes one to three divisions, producing two, four, or eight daughter cells encircled by the mother (sporangial) cell wall (Fig. 4). Sporangin is capable of breaking down the sporangial cell wall during hatching, and its expression is specifically induced during the S/M phase of the asexual cell cycle (Kubo et al., 2009). Under adverse conditions, Chlamydomonas initiates its sexual life cycle, in which haploid gametes of plus and minus mating types fuse to generate a diploid zygote that will divide into four vegetative cells when growth conditions return to normal. Gametolysin is secreted to digest and remove the gamete cell wall, thus allowing mating to commence (Fig. 4). It is noteworthy that gametolysin also exhibits lytic activity towards the cell walls of vegetative and sporangial cells (summarized in Matsuda, 2013).

Schematic illustration of the roles of sporangin and gametolysin in Chlamydomonas. Depending on the environmental conditions, Chlamydomonas can undergo either asexual (left) or sexual (right) reproduction cycles. The asexual cycle requires repeated alternating light/dark periods and replete nutrients, and is composed of two broad phases: the light-dependent cell growth (or G1) phase and the dark-dependent cell division (or S phases and mitoses, S/M) phase. Following S/M, daughter vegetative cells hatch out of the mother cell wall digested by sporangin (depicted by the black dotted oval). Under adverse conditions, such as nitrogen deprivation (-N) under light, the vegetative cells transform into gametes of mating type plus or minus. Two gametes of different mating types fuse to form a quadriflagellate cell in a process requiring the proteolytic activity of gametolysin, which removes gametic cell walls (depicted by the black dotted ovals). The quadriflagellate cell loses its cilia and becomes a mature zygote with a thick cell wall. Repletion of nitrogen (+N) induces the zygote to undergo meiosis, which will generate four haploid cells, two of each mating type. Whether proteases are involved in the liberation of haploid cells from the zygote cell wall remains unknown.

While there are only six genes encoding sporangin isoforms (Fig. S4 at Zenodo), the gametolysin family contains more than 40 members (Fig. 1). In Chlamydomonas, the sexual cycle represents not only a mode of reproduction, but also a strategy of overcoming adverse conditions (Suzuki and Johnson, 2002). Therefore, a large number of gametolysins present in Chlamydomonas might provide a robust mechanism facilitating cell-wall lysis not only in the secreting gametic cell, but also in surrounding cells, especially those with the opposite mating type, and in this way sustain algal fitness and survival under adverse conditions.

One representative of each of the gametolysin and sporangin families has been studied biochemically in more detail, and they were found to exhibit distinct P1 substrate specificity, potentially accounting for distinct target cell-wall specificity (Table 2). While gametolysin cleaves peptide bonds preferentially after hydrophobic residues (Matsuda et al., 1990), sporangin, similar to many other serine proteases, requires arginine or lysine at the P1 position (Matsuda et al., 1995). Gametolysin is a zinc-binding metalloprotease and requires metal ions for catalysis; accordingly, metal-binding chelators such as EDTA inhibit gametolysin activity (Matsuda et al., 1990). Although metal ions are presumably not required for the catalytic activity of serine proteases, they might be required for stabilization of the active conformation of the proteases. In line with this notion, it has been shown that EDTA inhibits the proteolytic activity of sporangin (Matsuda et al., 1995).

Concluding remarks

Chlamydomonas has emerged as a unique model representing an early diverged ancestor of higher plants and maintaining some features of the last eukaryotic common ancestor, such as cilia. Thus, Chlamydomonas offers a great evolutionary perspective for research on the mechanisms of cell motility and multicellular pattern formation, besides providing a comparable platform for studying metabolic and signalling pathways operating in higher plants. Since these mechanisms and pathways involve proteolytic regulation, and many proteases of Chlamydomonas are encoded by single-copy genes, the value of this model organism for studying proteolysis is difficult to overestimate.

In this review, we have attempted to offer a comprehensive survey of the protease degradome in Chlamydomonas that may be useful for conceiving future research endeavours. The functional studies performed thus far (Table 2) cover just a tiny fraction of Chlamydomonas proteases whose functions still need to be linked to specific proteolytic events. Overall, protease substrates and proteome modifications caused by proteolysis in Chlamydomonas remain unknown. This lack of knowledge calls for future studies of the Chlamydomonas protease degradome, which should be facilitated by the recent advent of N-terminomics (Luo et al., 2019), positional scanning substrate combinatorial library (PS-SCL) screening (Poręba et al., 2014), and methods for live imaging of protease activity (Fernández-Fernández et al., 2019).

Supplementary Material

erab383_suppl_Supplementary_Figures_S1_S4

erab383_suppl_Supplementary_Tables_S1_S3

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Adrian Dauphinee (SLU, Uppsala) for critical reading of the manuscript. Proteolysis research in our laboratory is supported by grants from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (2018.0026) and the Swedish Research Council, VR (2019-04250).

Author contributions

YZ: conceptualization, writing, and visualization (figure preparation). PBV: conceptualization, funding acquisition, and writing.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/record/5347045#.YS46It-xWUk; Zou and Bozhkov (2021).

References

- Abreu S, Kriegenburg F, Gómez-Sánchez R, et al. . 2017. Conserved Atg8 recognition sites mediate Atg4 association with autophagosomal membranes and Atg8 deconjugation. EMBO Reports 18, 765–780. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida CM, Pereira C, da Costa DS, Pereira S, Pissarra J, Simões I, Faro C. 2012. Chlapsin, a chloroplastidial aspartic proteinase from the green algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Planta 236, 283–296. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel B, Farmer LM, Rinaldi MA, Young PG, Danan CH, Burkhart SE. 2014. Mutation of the Arabidopsis LON2 peroxisomal protease enhances pexophagy. Autophagy 10, 518–519. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchnak I, van Wijk KJ. 2021. Structure, function, and substrates of Clp AAA+ protease systems in cyanobacteria, plastids, and apicoplasts: A comparative analysis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 296, 100338. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer K. 1985. Summary of green plant phylogeny and classification. Cladistics 1, 369–385. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Castruita M, Casero D, Karpowicz SJ, et al. . 2011. Systems biology approach in Chlamydomonas reveals connections between copper nutrition and multiple metabolic steps. The Plant Cell 23, 1273–1292. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin Y, Kapri-Pardes E, Sinvany G, Arad T, Adam Z. 2002. Expression and characterization of the thylakoid lumen protease DegP1 from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 130, 857–864. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Liu G, Ke W, et al. . 2017. Building a multipurpose insertional mutant library for forward and reverse genetics in Chlamydomonas. Plant Methods 13, 36. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen T, Southan C, Ehrmann M. 2002. The HtrA family of proteases: implications for protein composition and cell fate. Molecular Cell 10, 443–455. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. 2004. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Research 14, 1188–1190. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Cross FR, Umen JG. 2015. The Chlamydomonas cell cycle. The Plant Journal 82, 370–392. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Crozet P, Navarro FJ, Willmund F, et al. . 2018. Birth of a photosynthetic chassis: a MoClo toolkit enabling synthetic biology in the microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. ACS Synthetic Biology 7, 2074–2086. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Demir F, Niedermaier S, Villamor JG, Huesgen PF. 2018. Quantitative proteomics in plant protease substrate identification. New Phytologist 218, 936–943. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Derrien B, Majeran W, Wollman FA, Vallon O. 2009. Multistep processing of an insertion sequence in an essential subunit of the chloroplast ClpP complex. Journal of Biological Chemistry 284, 15408–15415. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Dissmeyer N, Rivas S, Graciet E. 2018. Life and death of proteins after protease cleavage: protein degradation by the N-end rule pathway. New Phytologist 218, 929–935. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- El-Gebali S, Mistry J, Bateman A, et al. . 2019. The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Research 47, D427–D432. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore ZC, Donaher M, Matson BC, Murphy H, Westerbeck JW, Kerscher O. 2011. Sumo-dependent substrate targeting of the SUMO protease Ulp1. BMC Biology 9, 74. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Emrich-Mills TZ, Yates G, Barrett J, et al. . 2021. A recombineering pipeline to clone large and complex genes in Chlamydomonas. The Plant Cell 33, 1161–1181. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Fang SC, Umen JG. 2008. A suppressor screen in Chlamydomonas identifies novel components of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor pathway. Genetics 178, 1295–1310. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer LM, Rinaldi MA, Young PG, Danan CH, Burkhart SE, Bartel B. 2013. Disrupting autophagy restores peroxisome function to an Arabidopsis lon2 mutant and reveals a role for the LON2 protease in peroxisomal matrix protein degradation. The Plant Cell 25, 4085–4100. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Fernández ÁD, Van der Hoorn RAL, Gevaert K, Van Breusegem F, Stael S. 2019. Caught green-handed: methods for in vivo detection and visualization of protease activity. Journal of Experimental Botany 70, 2125–2141. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Dietrich C, Matsuno M, Li G, Berg H, Xia Y. 2005. An Arabidopsis aspartic protease functions as an anti-cell-death component in reproduction and embryogenesis. EMBO reports 6, 282–288. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Harris EH. 2001. Chlamydomonas as a model organism. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 52, 363–406. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey CM, Wilson NR, Hochstrasser M. 2012. Function and regulation of SUMO proteases. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 13, 755–766. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Wang S, Chen L, Lemieux C, Otis C, Turmel M, Liu XQ. 1994. The Chlamydomonas chloroplast clpP gene contains translated large insertion sequences and is essential for cell growth. Molecular & General Genetics 244, 151–159. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaki H, Naveh L, Lindahl M, Cook M, Adam Z. 1998. Identification and characterization of DegP, a serine protease associated with the luminal side of the thylakoid membrane. Journal of Biological Chemistry 273, 7094–7098. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen K, Østergaard PR, Wilting R, Lassen SF. 2010. Identification and characterization of a bacterial glutamic peptidase. BMC Biochemistry 11, 47. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kapri-Pardes E, Naveh L, Adam Z. 2007. The thylakoid lumen protease Deg1 is involved in the repair of photosystem II from photoinhibition in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 19, 1039–1047. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Sakamoto W. 2018. FtsH protease in the thylakoid membrane: physiological functions and the regulation of protease activity. Frontiers in Plant Science 9, 855. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Sun X, Zhang L, Sakamoto W. 2012. Cooperative D1 degradation in the photosystem II repair mediated by chloroplastic proteases in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 159, 1428–1439. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman KJ, Yu S, Jin J, Mugo B, Nguyen N, O’Brien A, Nag S, Lystad AH, Melia TJ. 2018. Delipidation of mammalian Atg8-family proteins by each of the four ATG4 proteases. Autophagy 14, 992–1010. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kley J, Schmidt B, Boyanov B, Stolt-Bergner PC, Kirk R, Ehrmann M, Knopf RR, Naveh L, Adam Z, Clausen T. 2011. Structural adaptation of the plant protease Deg1 to repair photosystem II during light exposure. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 18, 728–731. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Abdel-Aziz AK, Abdelfatah S, et al. . 2021. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (4th edition). Autophagy 17, 1–382. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Knopf RR, Adam Z. 2018. Lumenal exposed regions of the D1 protein of PSII are long enough to be degraded by the chloroplast Deg1 protease. Scientific Reports 8, 5230. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kropat J, Gallaher SD, Urzica EI, Nakamoto SS, Strenkert D, Tottey S, Mason AZ, Merchant SS. 2015. Copper economy in Chlamydomonas: prioritized allocation and reallocation of copper to respiration vs. photosynthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 112, 2644–2651. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo T, Kaida S, Abe J, Saito T, Fukuzawa H, Matsuda Y. 2009. The Chlamydomonas hatching enzyme, sporangin, is expressed in specific phases of the cell cycle and is localized to the flagella of daughter cells within the sporangial cell wall. Plant & Cell Physiology 50, 572–583. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. 2018. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution 35, 1547–1549. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Li JB, Gerdes JM, Haycraft CJ, et al. . 2004. Comparative genomics identifies a flagellar and basal body proteome that includes the BBS5 human disease gene. Cell 117, 541–552. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Nelson C, Fenske R, Trösch J, Pružinská A, Millar AH, Huang S. 2017. Changes in specific protein degradation rates in Arabidopsis thaliana reveal multiple roles of Lon1 in mitochondrial protein homeostasis. The Plant Journal 89, 458–471. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhang R, Patena W, et al. . 2016. An indexed, mapped mutant library enables reverse genetics studies of biological processes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. The Plant Cell 28, 367–387. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ligeon LA, Pena-Francesch M, Vanoaica LD, Núñez NG, Talwar D, Dick TP, Münz C. 2021. Oxidation inhibits autophagy protein deconjugation from phagosomes to sustain MHC class II restricted antigen presentation. Nature Communications 12, 1508. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YL, Chung CL, Chen MH, Chen CH, Fang SC. 2020. SUMO protease SMT7 modulates ribosomal protein L30 and regulates cell-size checkpoint function. The Plant Cell 32, 1285–1307. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Lingard MJ, Bartel B. 2009. Arabidopsis LON2 is necessary for peroxisomal function and sustained matrix protein import. Plant Physiology 151, 1354–1365. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Törnkvist A, Charova S, Stael S, Moschou PN. 2020. Proteolytic proteoforms: elusive components of hormonal pathways? Trends in Plant Science 25, 325–328. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- López-Otín C, Bond JS. 2008. Proteases: multifunctional enzymes in life and disease. Journal of Biological Chemistry 283, 30433–30437. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Luo SY, Araya LE, Julien O. 2019. Protease substrate identification using N-terminomics. ACS Chemical Biology 14, 2361–2371. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Majeran W, Friso G, van Wijk KJ, Vallon O. 2005. The chloroplast ClpP complex in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii contains an unusual high molecular mass subunit with a large apical domain. The FEBS Journal 272, 5558–5571. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Majeran W, Wollman FA, Vallon O. 2000. Evidence for a role of ClpP in the degradation of the chloroplast cytochrome b6f complex. The Plant Cell 12, 137–150. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Majeran W, Wostrikoff K, Wollman F-A, Vallon O. 2019. Role of ClpP in the biogenesis and degradation of RuBisCO and ATP synthase in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plants 8, 191. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Malnoë A, Wang F, Girard-Bascou J, Wollman FA, de Vitry C. 2014. Thylakoid FtsH protease contributes to photosystem II and cytochrome b6f remodeling in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii under stress conditions. The Plant Cell 26, 373–390. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda Y. 2013. Gametolysin. In Rawlings ND, Salvesen G, eds. Handbook of Proteolytic Enzymes, Vol. 1. London: Elsevier, 891–895. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda Y, Koseki M, Shimada T, Saito T. 1995. Purification and characterization of a vegetative lytic enzyme responsible for liberation of daughter cells during the proliferation of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant & Cell Physiology 36, 681–689. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda Y, Uzaki T, Iwasawa N, Tanaka T, Saito T. 1990. Proteolytic activity against model peptides of the cell wall lytic enzyme from Chlamydomonas. Plant and Cell Physiology 31, 717–720. [Google Scholar]

- Meijer HJ, Berrie CP, Iurisci C, Divecha N, Musgrave A, Munnik T. 2001. Identification of a new polyphosphoinositide in plants, phosphatidylinositol 5-monophosphate (PtdIns5P), and its accumulation upon osmotic stress. Biochemical Journal 360, 491–498. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant SS, Prochnik SE, Vallon O, et al. . 2007. The Chlamydomonas genome reveals the evolution of key animal and plant functions. Science 318, 245–250. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Minina EA, Moschou PN, Bozhkov PV. 2017. Limited and digestive proteolysis: crosstalk between evolutionary conserved pathways. New Phytologist 215, 958–964. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Minina EA, Staal J, Alvarez VE, et al. . 2020. Classification and nomenclature of metacaspases and paracaspases: no more confusion with caspases. Molecular Cell 77, 927–929. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra LS, Mielke K, Wagner R, Funk C. 2019. Reduced expression of the proteolytically inactive FtsH members has impacts on the Darwinian fitness of Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Experimental Botany 70, 2173–2184. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N. 2020. The ATG conjugation systems in autophagy. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 63, 1–10. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JL, Puttick MN, Clark JW, Edwards D, Kenrick P, Pressel S, Wellman CH, Yang Z, Schneider H, Donoghue PCJ. 2018. The timescale of early land plant evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 115, E2274–E2283. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley JL, Chang CW, Grossman AR. 2006. Genome-based approaches to understanding phosphorus deprivation responses and PSR1 control in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eukaryotic Cell 5, 26–44. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert J, Gallaher SD, Lu Y, Strenkert D, Segal N, Barahimipour R, Fitz-Gibbon ST, Schroda M, Merchant SS, Bock R. 2020. An epigenetic gene silencing pathway selectively acting on transgenic DNA in the green alga Chlamydomonas. Nature Communications 11, 6269. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ng JWX, Tan QW, Ferrari C, Mutwil M. 2019. Diurnal.plant.tools: comparative transcriptomic and co-expression analyses of diurnal gene expression of the Archaeplastida kingdom. Plant & Cell Physiology 61, 212–220. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ni T, Yue J, Sun G, Zou Y, Wen J, Huang J. 2012. Ancient gene transfer from algae to animals: mechanisms and evolutionary significance. BMC Evolutionary Biology 12, 83. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Olinares PD, Kim J, van Wijk KJ. 2011. The Clp protease system; a central component of the chloroplast protease network. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1807, 999–1011. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Peltier JB, Ripoll DR, Friso G, Rudella A, Cai Y, Ytterberg J, Giacomelli L, Pillardy J, van Wijk KJ. 2004. Clp protease complexes from photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic plastids and mitochondria of plants, their predicted three-dimensional structures, and functional implications. Journal of Biological Chemistry 279, 4768–4781. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Pérez ME, Lemaire SD, Crespo JL. 2016. Control of autophagy in Chlamydomonas is mediated through redox-dependent inactivation of the ATG4 protease. Plant Physiology 172, 2219–2234. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Pérez ME, Lemaire SD, Crespo JL. 2021. The ATG4 protease integrates redox and stress signals to regulate autophagy. Journal of Experimental Botany 72, 3340–3351. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Pérez ME, Zaffagnini M, Marchand CH, Crespo JL, Lemaire SD. 2014. The yeast autophagy protease Atg4 is regulated by thioredoxin. Autophagy 10, 1953–1964. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Picariello T, Hou Y, Kubo T, McNeill NA, Yanagisawa HA, Oda T, Witman GB. 2020. TIM, a targeted insertional mutagenesis method utilizing CRISPR/Cas9 in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. PLOS ONE 15, e0232594. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Pinti M, Gibellini L, Nasi M, De Biasi S, Bortolotti CA, Iannone A, Cossarizza A. 2016. Emerging role of Lon protease as a master regulator of mitochondrial functions. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1857, 1300–1306. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Poręba M, Szalek A, Kasperkiewicz P, Drąg M. 2014. Positional scanning substrate combinatorial library (PS-SCL) approach to define caspase substrate specificity. Methods in Molecular Biology 1133, 41–59. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada V, Ordóñez GR, Sánchez LM, Puente XS, López-Otín C. 2008. The Degradome database: mammalian proteases and diseases of proteolysis. Nucleic Acids Research 37, D239–D243. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ramundo S, Casero D, Mühlhaus T, et al. . 2014. Conditional depletion of the chlamydomonas chloroplast ClpP protease activates nuclear genes involved in autophagy and plastid protein quality control. The Plant Cell 26, 2201–2222. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ramundo S, Rahire M, Schaad O, Rochaix JD. 2013. Repression of essential chloroplast genes reveals new signaling pathways and regulatory feedback loops in Chlamydomonas. The Plant Cell 25, 167–186. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ramundo S, Rochaix JD. 2014. Loss of chloroplast ClpP elicits an autophagy-like response in Chlamydomonas. Autophagy 10, 1685–1686. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings ND. 2020. Twenty-five years of nomenclature and classification of proteolytic enzymes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. Proteins and Proteomics 1868, 140345. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Bateman A. 2011. Asparagine peptide lyases: a seventh catalytic type of proteolytic enzymes. Journal of Biological Chemistry 286, 38321–38328. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Rigas S, Daras G, Laxa M, Marathias N, Fasseas C, Sweetlove LJ, Hatzopoulos P. 2009. Role of Lon1 protease in post-germinative growth and maintenance of mitochondrial function in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytologist 181, 588–600. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Salomé PA, Merchant SS. 2019. A series of fortunate events: introducing Chlamydomonas as a reference organism. The Plant Cell 31, 1682–1707. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Scherz-Shouval R, Shvets E, Fass E, Shorer H, Gil L, Elazar Z. 2007. Reactive oxygen species are essential for autophagy and specifically regulate the activity of Atg4. The EMBO Journal 26, 1749–1760. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Schroda M, Hemme D, Mühlhaus T. 2015. The Chlamydomonas heat stress response. The Plant Journal 82, 466–480. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmann H, Adamska I. 2012. Deg proteases and their role in protein quality control and processing in different subcellular compartments of the plant cell. Physiologia Plantarum 145, 224–234. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmann H, Huesgen PF, Adamska I. 2012. The family of Deg/HtrA proteases in plants. BMC Plant Biology 12, 52. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastián D, Fernando FD, Raúl DG, Gabriela GM. 2020. Overexpression of Arabidopsis aspartic protease APA1 gene confers drought tolerance. Plant Science 292, 110406. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Silflow CD, Lefebvre PA. 2001. Assembly and motility of eukaryotic cilia and flagella. Lessons from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiology 127, 1500–1507. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Simões I, Faro C. 2004. Structure and function of plant aspartic proteinases. European Journal of Biochemistry 271, 2067–2075. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sinvany-Villalobo G, Davydov O, Ben-Ari G, Zaltsman A, Raskind A, Adam Z. 2004. Expression in multigene families. Analysis of chloroplast and mitochondrial proteases. Plant Physiology 135, 1336–1345. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Solheim C, Li L, Hatzopoulos P, Millar AH. 2012. Loss of Lon1 in Arabidopsis changes the mitochondrial proteome leading to altered metabolite profiles and growth retardation without an accumulation of oxidative damage. Plant Physiology 160, 1187–1203. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Ströher E, Dietz KJ. 2008. The dynamic thiol-disulphide redox proteome of the Arabidopsis thaliana chloroplast as revealed by differential electrophoretic mobility. Physiologia Plantarum 133, 566–583. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G, Yang Z, Ishwar A, Huang J. 2010a. Algal genes in the closest relatives of animals. Molecular Biology and Evolution 27, 2879–2889. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Fu T, Chen N, Guo J, Ma J, Zou M, Lu C, Zhang L. 2010b. The stromal chloroplast Deg7 protease participates in the repair of photosystem II after photoinhibition in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 152, 1263–1273. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Peng L, Guo J, Chi W, Ma J, Lu C, Zhang L. 2007. Formation of DEG5 and DEG8 complexes and their involvement in the degradation of photodamaged photosystem II reaction center D1 protein in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 19, 1347–1361. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Wang F, Cai H, Zhao C, Ji W, Zhu Y. 2013. Functional characterization of an Arabidopsis prolyl aminopeptidase AtPAP1 in response to salt and drought stresses. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture 114, 325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki L, Johnson CH. 2002. Photoperiodic control of germination in the unicell Chlamydomonas. Die Naturwissenschaften 89, 214–220. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Theis J, Lang J, Spaniol B, et al. . 2019. The Chlamydomonas deg1c mutant accumulates proteins involved in high light acclimation. Plant Physiology 181, 1480–1497. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiatsiani L, Van Breusegem F, Gallois P, Zavialov A, Lam E, Bozhkov PV. 2011. Metacaspases. Cell Death and Differentiation 18, 1279–1288. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Tsitsekian D, Daras G, Alatzas A, Templalexis D, Hatzopoulos P, Rigas S. 2019. Comprehensive analysis of Lon proteases in plants highlights independent gene duplication events. Journal of Experimental Botany 70, 2185–2197. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Umen JG, Goodenough UW. 2001. Control of cell division by a retinoblastoma protein homolog in Chlamydomonas. Genes & Development 15, 1652–1661. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hoorn RA. 2008. Plant proteases: from phenotypes to molecular mechanisms. Annual Review of Plant Biology 59, 191–223. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaeren H, Nam YJ, De Milde L, Chae E, Storme V, Weigel D, Gonzalez N, Inzé D. 2016. Forever young: the role of ubiquitin receptor DA1 and E3 ligase BIG BROTHER in controlling leaf growth and development. Plant Physiology 173, 1269–1282. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Vercammen D, van de Cotte B, De Jaeger G, Eeckhout D, Casteels P, Vandepoele K, Vandenberghe I, Van Beeumen J, Inzé D, Van Breusegem F. 2004. Type II metacaspases Atmc4 and Atmc9 of Arabidopsis thaliana cleave substrates after arginine and lysine. Journal of Biological Chemistry 279, 45329–45336. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Qi Y, Malnoë A, Choquet Y, Wollman FA, de Vitry C. 2017a. The high light response and redox control of thylakoid FtsH protease in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Molecular Plant 10, 99–114. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JL, Tang MQ, Chen S, et al. . 2017b. Down-regulation of BnDA1, whose gene locus is associated with the seeds weight, improves the seeds weight and organ size in Brassica napus. Plant Biotechnology Journal 15, 1024–1033. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Li S, Chen D, Xi Y, Xu X, Ye N, Zhang J, Peng X, Zhu G. 2018. Impairment of FtsHi5 function affects cellular redox balance and photorespiratory metabolism in Arabidopsis. Plant & Cell Physiology 59, 2526–2535. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L, Derrien B, Gautier A, et al. . 2014. Nitric oxide-triggered remodeling of chloroplast bioenergetics and thylakoid proteins upon nitrogen starvation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. The Plant Cell 26, 353–372. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Weng SSH, Demir F, Ergin EK, Dirnberger S, Uzozie A, Tuscher D, Nierves L, Tsui J, Huesgen PF, Lange PF. 2019. Sensitive determination of proteolytic proteoforms in limited microscale proteome samples. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 18, 2335–2347. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J, Park E, Dinesh-Kumar SP. 2014. Differential processing of Arabidopsis ubiquitin-like Atg8 autophagy proteins by Atg4 cysteine proteases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 111, 863–868. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y, Suzuki H, Borevitz J, Blount J, Guo Z, Patel K, Dixon RA, Lamb C. 2004. An extracellular aspartic protease functions in Arabidopsis disease resistance signaling. The EMBO Journal 23, 980–988. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Yates G, Srivastava AK, Sadanandom A. 2016. SUMO proteases: uncovering the roles of deSUMOylation in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 67, 2541–2548. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto K, Ohsumi Y. 2018. Unveiling the molecular mechanisms of plant autophagy—from autophagosomes to vacuoles in plants. Plant and Cell Physiology 59, 1337–1344. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Yu AY, Houry WA. 2007. ClpP: a distinctive family of cylindrical energy-dependent serine proteases. FEBS Letters 581, 3749–3757. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Shrager J, Jain M, Chang CW, Vallon O, Grossman AR. 2004. Insights into the survival of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii during sulfur starvation based on microarray analysis of gene expression. Eukaryotic Cell 3, 1331–1348. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P, Zhang F, Liu D, Imani J, Langen G, Kogel KH. 2017. Matrix metalloproteinases operate redundantly in Arabidopsis immunity against necrotrophic and biotrophic fungal pathogens. PLOS ONE 12, e0183577. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X. 2018. SUMO-mediated regulation of nuclear functions and signaling processes. Molecular Cell 71, 409–418. [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Zones JM, Blaby IK, Merchant SS, Umen JG. 2015. High-resolution profiling of a synchronized diurnal transcriptome from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii reveals continuous cell and metabolic differentiation. The Plant Cell 27, 2743–2769. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y, Bozhkov PV. 2021. Data from: Chlamydomonas proteases: classification, phylogeny and molecular mechanisms. Zenodo. https://zenodo.org/record/5347045#.YS46It-xWUk [Europe PMC free article] [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

Articles from Journal of Experimental Botany are provided here courtesy of Oxford University Press

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erab383

Read article for free, from open access legal sources, via Unpaywall:

https://academic.oup.com/jxb/article-pdf/72/22/7680/41505872/erab383.pdf

Citations & impact

Impact metrics

Citations of article over time

Alternative metrics

Discover the attention surrounding your research

https://www.altmetric.com/details/112716865

Article citations

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii-A Reference Microorganism for Eukaryotic Molybdenum Metabolism.

Microorganisms, 11(7):1671, 27 Jun 2023

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 37512844 | PMCID: PMC10385300

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Towards green biomanufacturing of high-value recombinant proteins using promising cell factory: Chlamydomonas reinhardtii chloroplast.

Bioresour Bioprocess, 9(1):83, 13 Aug 2022

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 38647750 | PMCID: PMC10992328

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

Pilot-Scale Cultivation of the Snow Alga Chloromonas typhlos in a Photobioreactor.

Front Bioeng Biotechnol, 10:896261, 09 Jun 2022

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 35757813 | PMCID: PMC9218667

Recent Advances in Understanding the Structural and Functional Evolution of FtsH Proteases.

Front Plant Sci, 13:837528, 06 Apr 2022

Cited by: 13 articles | PMID: 35463435 | PMCID: PMC9020784

Review Free full text in Europe PMC

The Papain-like Cysteine Protease HpXBCP3 from Haematococcus pluvialis Involved in the Regulation of Growth, Salt Stress Tolerance and Chlorophyll Synthesis in Microalgae.

Int J Mol Sci, 22(21):11539, 26 Oct 2021

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 34768970 | PMCID: PMC8583958

Go to all (6) article citations

Data

Data behind the article

This data has been text mined from the article, or deposited into data resources.

BioStudies: supplemental material and supporting data

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Comparison of the chloroplast peroxidase system in the chlorophyte Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, the bryophyte Physcomitrella patens, the lycophyte Selaginella moellendorffii and the seed plant Arabidopsis thaliana.

BMC Plant Biol, 10:133, 28 Jun 2010

Cited by: 22 articles | PMID: 20584316 | PMCID: PMC3095285

The family of DOF transcription factors: from green unicellular algae to vascular plants.

Mol Genet Genomics, 277(4):379-390, 16 Dec 2006

Cited by: 95 articles | PMID: 17180359

Commonalities and differences of chloroplast translation in a green alga and land plants.

Nat Plants, 4(8):564-575, 30 Jul 2018

Cited by: 27 articles | PMID: 30061751

The ATG4 protease integrates redox and stress signals to regulate autophagy.

J Exp Bot, 72(9):3340-3351, 01 Apr 2021

Cited by: 11 articles | PMID: 33587749

Review