Abstract

Objective

To test the hypothesis that caffeine can influence tinnitus, we recruited 80 patients with chronic tinnitus and randomly allocated them into two groups (caffeine and placebo) to analyze the self-perception of tinnitus symptoms after caffeine consumption, assuming that this is an adequate sample for generalization.Methods

The participants were randomized into two groups: one group was administered a 300-mg capsule of caffeine, and the other group was given a placebo capsule (cornstarch). A diet that restricted caffeine consumption for 24 hours was implemented. The participants answered questionnaires (the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory-THI, the Visual Analog Scale-VAS, the profile of mood state-POMS) and underwent examinations (tonal and high frequency audiometry, acufenometry (frequency measure; intensity measure and the minimum level of tinnitus masking), transient otoacoustic emissions-TEOAE and distortion product otoacoustic emissions-DPOAE assessments) at two timepoints: at baseline and after capsule ingestion.Results

There was a significant change in mood (measured by the POMS) after caffeine consumption. The THI and VAS scores were improved at the second timepoint in both groups. The audiometry assessment showed a significant difference in some frequencies between baseline and follow-up measurements in both groups, but these differences were not clinically relevant. Similar findings were observed for the amplitude and signal-to-noise ratio in the TEOAE and DPOAE measurements.Conclusions

Caffeine (300 mg) did not significantly alter the psychoacoustic measures, electroacoustic measures or the tinnitus-related degree of discomfort.Free full text

The effect of caffeine on tinnitus: Randomized triple-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial

Abstract

Objective

To test the hypothesis that caffeine can influence tinnitus, we recruited 80 patients with chronic tinnitus and randomly allocated them into two groups (caffeine and placebo) to analyze the self-perception of tinnitus symptoms after caffeine consumption, assuming that this is an adequate sample for generalization.

Methods

The participants were randomized into two groups: one group was administered a 300-mg capsule of caffeine, and the other group was given a placebo capsule (cornstarch). A diet that restricted caffeine consumption for 24 hours was implemented. The participants answered questionnaires (the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory—THI, the Visual Analog Scale—VAS, the profile of mood state—POMS) and underwent examinations (tonal and high frequency audiometry, acufenometry (frequency measure; intensity measure and the minimum level of tinnitus masking), transient otoacoustic emissions—TEOAE and distortion product otoacoustic emissions—DPOAE assessments) at two timepoints: at baseline and after capsule ingestion.

Results

There was a significant change in mood (measured by the POMS) after caffeine consumption. The THI and VAS scores were improved at the second timepoint in both groups. The audiometry assessment showed a significant difference in some frequencies between baseline and follow-up measurements in both groups, but these differences were not clinically relevant. Similar findings were observed for the amplitude and signal-to-noise ratio in the TEOAE and DPOAE measurements.

Conclusions

Caffeine (300 mg) did not significantly alter the psychoacoustic measures, electroacoustic measures or the tinnitus-related degree of discomfort.

Introduction

Tinnitus is defined as an auditory perception in the absence of an external sound source. An incidence rate of 25.0 new cases of tinnitus per 10,000 person-years in the United Kingdom has been estimated. In the United States, the prevalence of tinnitus among adults is estimated to range from 10% to 15% [1, 2]. The annoyance of the tinnitus was a result of the tinnitus characteristics and the psychological make up of each individual patient [3] and can affect all aspects of life: it can cause personal, professional, social and family issues, and it can have negative impacts on concentration, sleep, reasoning, memory, emotional balance and social life [4, 5].

The American Academy of Otorhinolaryngology recommends that only patients with tinnitus-related discomfort be identified and treated. For this purpose, it recommends the application of a validated questionnaire; the THI is the most used questionnaire across all regions [1, 6, 7]. The visual analog scale is widely used in clinical practice and research because it is a quick and easy to understand tool, although it has not yet been specifically validated to assess tinnitus [8, 9]. Tinnitus, as a subjective sensation, is directly influenced by the individual’s mood [8]. The POMS is the most sensitive questionnaire to assess the effects of caffeine on mood [10].

There are reports of recommendations for performing psychoacoustic measures to assess tinnitus dating back to 1931; however, there is still no consensus on its realization and indication [9]. The European multidisciplinary guideline for the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of tinnitus recommends researching the pitch and loudness of tinnitus as part of the minimum patient assessment [7]. Some authors suggest that this method is an important tool in the characterization of tinnitus and documentation of the efficacy of the adopted therapy [8, 9, 11].

An interruption in the use of caffeine is indicated as part of the treatment for tinnitus. However, the efficacy of this generic treatment lacks scientific evidence [12]. Caffeine is the most commonly consumed psychoactive substance in the world and is found in many products, such as coffee, tea, chocolate, soft drinks, mate herb, powdered guarana, weight loss drugs, diuretics, stimulants, analgesics and anti-allergens. This discontinuation of caffeine use can lead to caffeine withdrawal syndrome, exacerbating symptoms such as headache, irritability and depressed mood [13–15].

Therefore, the present study sought to analyze the influence of caffeine on tinnitus-related discomfort as measured by acoustic, electroacoustic and psychoacoustic assessments. We hypothesize that caffeine use does not change tinnitus-related discomfort.

Methods

Study design, approvals, registration and patient consents

This was a randomized, triple blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial approved by the Institutional Research Board of the faculty of health sciences of the University of Brasília (number: 2.031.285) and registered on the national platform for registration of experimental studies—REBEC Platform (RBR-4CRF4D). All data presented in the studies were deposited in an appropriate public repository (DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.12962684). The authors confirm that all ongoing and related trials for this drug/intervention are registered.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The sample consisted of individuals who came to the doctor’s office reporting tinnitus as the main complaint, of both sexes who were over 18 years of age. Participants who reported objective intermittent or acute tinnitus (less than six months of tinnitus) during a medical consultation [1], those with psychiatric and/or cognitive disorders that prevented the understanding of tests and questionnaires, and those who used illicit drugs were excluded.

Recruitment

Four otolaryngologists from a private otorhinolaryngology institute located in Brazil participated in the recruitment process. All individuals who came to the doctor’s office of this institute with a main complaint of tinnitus between July 2018 and January 2019 were invited to participate in the study. They were informed about the objectives of the study and completed an anamnesis to report the main characteristics of the tinnitus and to provide their contact information. Subsequently, the main researcher contacted them to inform them about all the research phases and to schedule their participation after obtaining written informed consent.

Randomization and blinding

Participants were randomly assigned to receive a placebo or a caffeine capsule in a 1:1 ratio by an independent contributor. A completely randomized design was used for both treatments using RANDOMIZATION.COM, with the "First generator" plan that creates random permutations for the treatments used in research. The same employee placed the appropriate capsules in identical packages marked with continuous numbers. The active ingredient (300 mg caffeine) and placebo (cornstarch) were packed in capsules that were identical in color, size and weight. The evaluator, participants and statistician were blinded to the intervention and groups.

The active ingredient

Caffeine (1, 3, 7-trimethylxanthine) is a central nervous system stimulant belonging to the group of methylxanthines, being fat-soluble and capable of overcoming all biological barriers [16]. It has rapid absorption and 99% is absorbed 45 minutes after ingestion. Plasma concentration in humans is reached 45 to 120 minutes after ingestion and has a half-life of 2.5 to 4.5 hours [17, 18].

Moderate caffeine consumption is classified between 100 and 300mg of caffeine / day, and this consumption is frequently found in individuals around the world [16, 19–21]. Studies suggest that the effects of caffeine start to be observed from 200mg and the toxic effects from an intake of 400mg in healthy adults [22, 23], with reports of previous controlled studies that used doses of 300mg of caffeine [24–26]. Thus, the dosage of 300mg was chosen because it is common in consumers around the world, being pharmacologically active without, however, causing toxic effects.

Procedures

The research participants first completed a clinical anamnesis to assess the characteristics of their tinnitus and a questionnaire about their eating habits to assess the amount of caffeine they ingested daily.

This study consisted of three phases (Table 1).

Table 1

| Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 |

|---|---|---|

| THI | Capsule administration | THI |

| VAS | VAS | |

| POMS | POMS | |

| OAE | OAE | |

| Audiometry | Audiometry | |

| Acuphenometry | Acuphenometry |

A caffeine-free diet was implemented 24 hours before testing. The diet was instructed via telephone contact, providing a detailed list of products that should be avoided via text message or e-mail. The three phases took place on the same day, with an average duration of 4 to 5 hours. In phase 1, the individuals completed the questionnaires and underwent the assessments in the order shown in Table 1. Afterwards, they received the caffeine capsule or the placebo (phase 2). Phase 3 was performed one hour after the ingestion of the capsule with the same procedures and order as in phase 1. All phases of the study were carried out at the same otorhinolaryngologist institute in which recruitment occurred.

Questionnaires and exams

In order to find out the amount of caffeine ingested daily by the participants, the adapted eating habits questionnaire was applied and the parameters of the volume and caffeine content of each product of this study was used [22]. The questionnaire investigates the consumption of coffee, tea, mate herb, chocolate, soda, chocolate powder and food and energy supplements, highlighting the type, quantity, brand, shape and frequency of consumption.

To assess the tinnitus-related discomfort, two questionnaires were applied: the tinnitus handicap inventory (THI) and the visual analog scale (VAS). THI seeks to measure the impact of tinnitus on the patient’s quality of life. It consists of 25 questions with a total score ranging from 0 to 100. For each item one must answer "yes", "sometimes" and "not" being assigned the score 4 for each "yes" answer, 2 for each answer “sometimes” and 0 for each answer “no”. Based on the total score obtained, tinnitus is classified as no handicap (0 to 16 points), mild handicap (18 to 36), moderate handicap (38 to 56), severe handicap (58 to 76) and catastrophic handicap (78 to 100) [27, 28]. The VAS is a black and white scale used to estimate the magnitude that ranges from 0 to 10 divided into three parts: 0–2 (mild), 3–7 (moderate) and 8–10 (intense) [29].

In addition to tinnitus-related discomfort, the individual’s mood at the time of the exams was assessed using the Profile of Mood States (POMS). The questionnaire consists of 65 items that describe feelings, where the subjects must attribute the mentions on a 5-point likert scale: 0—nothing, 1—a little, 2—more or less, 3—a lot and 4—extremely. The results found in each affective state were analyzed: tension-anxiety, depression-discouragement, anger-hostility, vigor-activity, fatigue-inertia and mental confusion-perplexity. In addition, the TMD (Total Mood Disturbance) was calculated, which represents an overview of mood, according to criteria determined by the questionnaire authors [30]. All questionnaires were completed in a silent environment in the presence of the main researcher, who answered any questions the participants had about the assessments. Participants had the necessary time to complete the questionnaires.

Tonal audiometry was performed with the warble stimulus at frequencies of 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 0.5 and 0.25kHz using the descending-ascending technique. Then, high-frequency audiometry was performed at frequencies of 9, 10, 11.2, 12.5, 14, 16 and 18 kHz. These examinations were performed using the AD 229 audiometer from Interacoustics and the HDA 300 headphones, both of which were calibrated annually. Individuals who had hearing thresholds less than or equal to 25dB in all frequencies of conventional audiometry were classified as normal hearing [31].

In acuphenometry, pitch (frequency measure), loudness (intensity measure) and the minimum level of tinnitus masking were evaluated using the same equipment. To measure the pitch, the pure tone stimulus was used if the patient characterized the tinnitus as a whistle, and the narrow band noise was used if patient characterized the tinnitus as a hiss. Two extreme frequencies were presented at an intensity of 10 dBSL until the patient identified the sound that most resembled his or her tinnitus. Then, loudness was investigated, and the frequency indicated by the patient was presented from the audiometric threshold until the patient described an intensity similar to his or her tinnitus. A 1-dB scale was used. Finally, the minimum level of tinnitus masking was assessed by presenting white noise in the ear contralateral to the tinnitus (if the tinnitus was unilateral) or in the ear where the tinnitus was less intense (if the tinnitus was bilateral) until the individual no longer noticed the tinnitus. If there was no masking, the research was interrupted at 80 dBHL to avoid exposure to a very high intensity. In all measures, the level of sensation was considered).

The electroacoustic evaluation was performed by researching the transient otoacoustic emissions and distortion product using the Otoread Interacoustic (Denmark) instrument at an intensity of 80 dB with 1000 presentations. The frequency bands of 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6kHz were evaluated in the transients, and frequency bands of 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6kHz were evaluated in the distortion product bilaterally.

Statistical analysis

The calculation of the sample size was performed using the estimated variability of the THI variable (range 0 to 100) with standard deviation equal to 2.0 and the capacity to detected 3 points in a difference between groups caffeine and placebo, considering the following parameters: an α of 0.05, a test power (1-β) of 0.8, and 10% of loss of collection, it was determined that 39 individuals were needed in each group.

The distributions of the variables were analyzed, revealing nonnormal distributions for all analyzed variables. Thus, the data were presented as medians and analyzed using nonparametric tests.

Baseline measurements in the two groups were compared using the Chi-square test. The analysis of quantitative variables was performed using the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The correlation between variables was assessed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. P <0.05 was considered significant. The analysis was performed using the SAS 9.4 application (SAS Institute, Inc., 1999).

Results

Recruitment and randomization

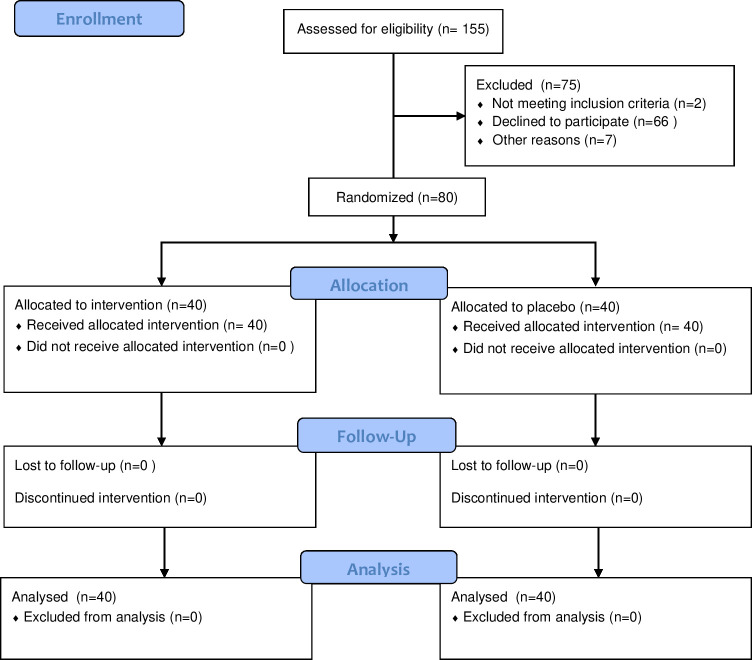

A total of 155 individuals were invited to participate. Of these, 7 did not provide valid contact information, 2 reported having intermittent tinnitus, and 66 declined to participate when contacted; thus, we analyzed data from 80 participants,40 in each group (Fig 1).

Recruitment was stopped when the required sample and a 6-month recruitment period has been reached. All data analyses were performed with 40 individuals from each group.

Sample characterization

The individual characteristics, characteristics of tinnitus and tinnitus-related discomfort were statistically similar in both groups, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

| Caffeine group | Placebo group | ||

| Percentage | p-value | ||

| Gender | 50% Female | 55% Female | 0.654 |

| 50% Male | 45% Male | ||

| Hearing loss | 50% Have | 47.5% Have | 0.502 |

| 50% Do not have | 52.5 Do not have | ||

| Tinnitus type | 82.5% whistle | 75% whistle | 0.412 |

| 17.5% wheezing | 25% wheezing | ||

| Tinnitus location | 50% bilateral | 40% bilateral | 0.693 |

| 12.5% right ear | 25% right ear | ||

| 12.5% left ear | 17.5% left ear | ||

| 20% In the head | 17.5% In the head | ||

| THI classification | 27% No handicap | 22% No handicap | 0.255 |

| 25% Mild handicap | 37% Mild handicap | ||

| 33% Moderate handicap | 23% Moderate handicap | ||

| 15% Severe handicap | 10% Severe handicap | ||

| 0% Catastrophic handicap | 8% Catastrophic handicap | ||

| Median (IQR) | p-value | ||

| Age (yrs) | 52 (42.25–60) | 52 (43–59,5) | 0.855 |

| Tinnitus duration (mos) | 36 (11.25–147) | 48 (17.25–165) | 0.497 |

| Caffeine consumption (mg/day) | 91.5 (28.5–175.75) | 92 (43.5–200.75) | 0.795 |

| Tritonal mean Right ear (dB) | 16.7 (10–25) | 13.3 (8–23) | 0.304 |

| Tritonal mean Left ear (dB) | 15.0 (12–23) | 14.2 (10–17.75) | 0.429 |

| THI total score | 36 (4–74) | 32 (4–82) | 0.603 |

| VAS | 5 (3–7) | 6 (2–7) | 0.645 |

| POMS (TMD) | -9 (-19–12.5) | -8 (-19–15.75) | 0.864 |

Note: * calculation of p-value of the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test

IQR: Interquartile ranges.

Caffeine consumption in the usual diet was not correlated with age, sex, tinnitus duration, or the initial measurements of THI, VAS and loudness (Table 3).

Table 3

| Variables | Value | p-value* |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

Correlation Correlation | 0.15 | 0.181 |

| Gender ** | ||

Male Male | 60 (11,75–168) | 0.378 |

Female Female | 37.5 (14,5–120) | |

| Tinnitus duration | ||

Correlation Correlation | 0.07 | 0.544 |

| THI | ||

Correlation Correlation | -0.02 | 0.846 |

| VAS | ||

Correlation Correlation | -0.04 | 0.755 |

| Loudness | ||

Correlation Correlation | 0.07 | 0.569 |

Note: *p-value of Spearman’s correlation test and

** calculation of median (interquartile ranges)

Comparison of phases 1 and 3

Questionnaires measurements

The assessment of mood through the Profile of Mood States demonstrated a statistically significant difference in the TMD (p<0.001), tension-anxiety (p = 0.009), depression-despondency (p <0.001) and anger-hostility (p = 0.027) states between phase 1 and phase 3 in the caffeine group, with lower values in phase 3 for all states. In the control group, there was a significant difference in the affective states of tension-anxiety (p = 0.026) and mental confusion-perplexity (p = 0.013) between phase 1 and phase 3 with lower values in phase 3.

Regarding the tinnitus-related discomfort measured by the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), there was a statistically significant difference in THI scores between phases 1 and 3 in both groups, with lower values in phase 3. The caffeine group in phase 1 had a median of 36, IQR of 35.5 and a p-value of 0.001, and the placebo group had a median of 32, IQR of 27.0 and a p-value of <0.001. The analysis of questions 8 and 19 of the THI demonstrated that there was no statistically significant difference between phases 1 and 3. In question 8, a median of 4 p-values of 0.18 was observed in the caffeine group and a median of 4 p-values of 0.79 in the placebo group; in question 19, median of 4 and p value of 0.21 in the caffeine group and median of 4 and p value of 0.97 in the placebo group.

There was no difference in the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores between phases 1 and 3 in either group; the caffeine group had a median of 5.0, IQR of 4.0 and a p-value of 0.977, and the placebo group had a median of 6.0, IQR of 5.0 and a p-value of 0.699.

The comparison between the differences found in each group demonstrated that there was no significant difference in any aspect of the questionnaires. When correlating the consumption of caffeine with the results of the questionnaires, there was also no statistically significant difference in any aspect (S1 Appendix).

Psychoacoustic measurements

The evaluation of pitch revealed a high prevalence of individuals with high-frequency tinnitus and substantial differences in the measurements between phases 1 and 3. There was no difference in loudness or minimal masking level (MML) between phases 1 and 3 in both groups. The caffeine group had a median loudness value and a minimum masking level of 6 dB and 15.5 dB, respectively; the placebo group had a median loudness value and a minimum masking level of 5 dB and 15 dB, respectively.

The caffeine group showed a statistically significant difference between thresholds at frequencies of 2, 3 and 4kHz in the right ear. The placebo group showed a significant difference between thresholds at frequencies of 0.25, 3 and 4kHz in the right ear and at frequencies of 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2 and 3kHz in the left ear. High-frequency audiometry did not reveal difference at any frequency in the caffeine group; in the placebo group, there were significant differences at 18 kHz in the right ear and at 14 kHz in the left ear.

The comparison between the differences found in each group demonstrated that had a statistically significant difference in the thresholds only of the conventional audiometry in the left ear in some frequencies as shown in S1 Appendix. A very weak correlation was found between caffeine consumption and the thresholds in the frequency of 8 and 14kHz in phase 3 in the right ear and 0.5 and 14kHz in phase 1 and 14 and 18kHz in phase 3 in the left ear, and the higher the thresholds the higher the habitual consumption of caffeine.

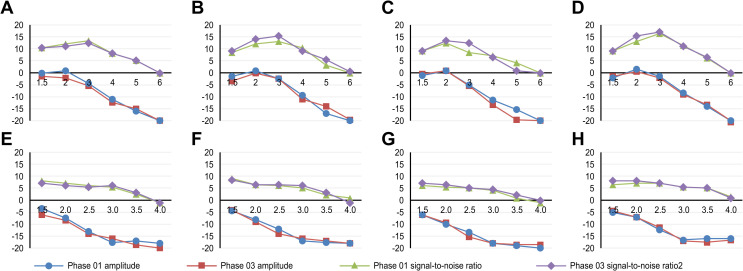

Electroacoustic measurements

For distortion product otoacoustic emission (DPOAE) assessments, the caffeine group showed a statistically significant difference in the signal-to-noise ratio at the frequency of 3kHz in the left ear between phases 1 and 3, with higher ratios in phase 3. The placebo group showed significant differences in amplitude at 4kHz and in the signal-to-noise ratio at 3kHz in the right ear (Fig 2).

A- DPOAE for the right ear in the caffeine group; B- DPOAE for the right ear in the placebo group; C- DPOAE for the left ear in the caffeine group; D- DPOAE for the left ear in the placebo group; E- TEOAE for the right ear in the caffeine group; F- TEOAE for the right ear in the placebo group; G- TEOAE for the left ear in the caffeine group; H- TEOAE for the left ear in the placebo group.

For the transient otoacoustic emission (TEOAE) assessments, the caffeine group showed a statistically significant difference in the signal-to-noise ratio at the frequency of 3.5kHz in the right ear and at 4kHz in the left ear between phases 1 and 3, with higher values in phase 3. The placebo group showed differences in amplitude at 4kHz in the right ear and in the signal-to-noise ratio at 3kHz in the left ear (Fig 2).

The comparison between the differences found in each group demonstrated a statistically significant difference in the signal-to-noise ratio in the left ear at EOA-PD at 3kHz in phases 1 and 3 and at EOA-T at 3.5kHz in phases 1 and 3 and at 4kHz in phase 1. No correlation was found between caffeine consumption and the parameters analyzed in otoacoustic emissions (S1 Appendix).

Harms

When asked about any change in sensation between phases 1 and 3, 74 individuals reported not having noticed any change. Of those who reported change, 4 individuals reported adverse effects, such as palpitation (placebo group), "pressure in the ear" (caffeine group), "headache" (placebo group) and "pressure in the head" (placebo group). One individuals in the caffeine group reported "being more alert", and another individual from the same group reported a lack of headache.

Discussion

The sample profile of the present study is similar to that previously reported in the literature, being representative of this population. The individual characteristics of the sample were similar regarding the number of males and females and an average age of approximately 50 years [8, 32, 33]. The duration of tinnitus was shorter than previously reported [8, 32], and the location of the tinnitus had a similar distribution to that reported in the literature, being more prevalent bilaterally [32, 34, 35]. The THI and VAS values were similar to those previously reported [9, 36].

Hearing loss is believed to be a risk factor for tinnitus [37]. In the present study, a high number of individuals had normal hearing or hearing loss at isolated higher frequencies. A reduction in thresholds was observed at higher frequencies, indicating a cochlear lesion at baseline even in individuals with normal hearing [32].

The median caffeine consumption was 91.5 mg/day in the caffeine group and 92 mg/day in the placebo group, which is considered to be a low level of consumption. Studies using the POMS have shown an increase in TMD [26, 38] and in vigor-activity state [39–41] and a reduction in fatigue-inertia [39–42] and in mental confusion-bewilderment [26, 38], after caffeine consumption. The present study showed an improvement in mood after caffeine consumption and a significant reduction in the tension-anxiety, depression-discouragement and anger-hostility states. The lack of an increase in vigor activity may be associated to the low daily consumption of caffeine among the sample, since an increase in this parameter has only been shown in habitual caffeine consumers [43].

When comparing the results of phases 1 and 3, were observed changes in THI and in all tests performed in both groups: caffeine and placebo. This fact suggests that the effects on tinnitus cannot be directly linked to caffeine, since in the placebo group, there were also changes identified after taking caffeine-free capsules. THI questions 8 and 19 were analyzed individually because, although there is a recommendation in the literature on the use of the total score in research and clinical practice [44], it was demonstrated that these questions appear to be more sensitive to the effects of changes [11, 45]. The non-significant variation between the values of phases 1 and 3 in both groups corroborate the hypothesis that caffeine does not influence the discomfort with tinnitus.

The influence of caffeine on tinnitus-related discomfort has been investigated by other researchers using different instruments. A double-blind pseudorandomized clinical trial in the United Kingdom used four analysis instruments and found that caffeine abstinence did not improve tinnitus-related discomfort. The authors added that caffeine abstinence led to side effects such as headache and nausea [12].

Only two studies that investigated the relationship between caffeine and tinnitus using the THI and VAS instruments. One of them revealed no correlation between VAS scores and caffeine consumption in the usual diet as observed in the present sample however, because it is a retrospective cross-sectional study, it was not proposed to investigate the results of VAS after consuming a certain dose of caffeine. [46]. The other study evaluated the influence of caffeine reduction in the long term (1 month) on VAS and THI results, finding a positive relationship in them; however, that study was not blinded, which may have influenced the patient’s responses to the questionnaire [36].

In the present study, a high prevalence of individuals with high-frequency tinnitus was observed. These data diverged from a previous study where it was found that 68% of the individuals had tinnitus with a pitch of up to 3000Hz [34] and another that reported 6kHz to be the most prevalent pitch [9]. These studies describe the pitch of tinnitus in adult individuals without relating them to caffeine consumption. It is worth mentioning that the mentioned studies do not research pitch at high frequencies. Herein, there was great variability in pitches between phase 1 and 3 measurements in both groups. This low replicability between measurements at different times was noted earlier, suggesting the need for the test to be repeated more times to learn the procedure [35, 47].

The loudness found in the sample was similar to those previously reported, which were up to 3 dB in 61% of individuals and between 4 and 6 dB in 28% of individuals [34]. It has been previously demonstrated that the loudness measured at the frequency of tinnitus presents only a few decibels above thresholds due to the occurrence of recruitment. An abnormally loudness growth occurs leading to the sound being perceived as much higher than their low sensation levels would indicate [47, 48].

There was no statistically significant difference in loudness between phases 1 and 3, suggesting that caffeine had little influence on loudness. It is worth mentioning that although the replicability rate of tinnitus psychoacoustic measurements is variable, loudness tends to have better replicability, with variations of no more than 2dB observed when measurements are replicated on the same day [47].

In both groups, a statistically significant difference was found in the audiometric thresholds between phases 1 and 3 for some frequencies in both conventional and high frequency audiometry. It is known that pure tone audiometry is influenced by endogenous factors such as attention and patient experience [49]; the difference observed herein was not of clinical value since only two individuals in each group showed variation in the degree of hearing loss grade between phases 1 and 3, and this variation in degree was due to the difference of less than 10dB between the measures which is considered a non-significant variation [50]. These data differ from out expectations since caffeine has been shown to improve an individual’s alertness, ability to concentrate, attention and memory and improves transmission in the central brain auditory pathways [51, 52].

The electroacoustic evaluation showed a difference in the measurements of otoacoustic emissions in terms of amplitude and signal-to-noise ratio at some frequencies in both the caffeine group and the placebo group. The amplitude and signal-to-noise ratio decreased with increasing frequencies. However, it has been observed that the absence of responses at 5kHz and 6kHz is not uncommon in adults without tinnitus even with thresholds within the normal range among these frequencies [53].

The limitations of this study involve measurement bias, as the THI is not meant for measuring momentary variations in the sensation of tinnitus and acuphenometry is influenced by repeated measurements. These methods, despite their limitations, were used because there are no other validated and widely used methods in clinical and scientific practice that met the objectives set.

Conclusion

Caffeine at a dose of 300 mg did not significantly alter the psychoacoustic measures, electroacoustic measures or tinnitus-related discomfort among light caffeine consumers.

Supporting information

S1 Appendix

Difference groups correlation with caffeine consumption.(DOCX)

S2 Appendix

Consubstanced opinion in Portuguese (original).(PDF)

S3 Appendix

Consubstanced opinion in English (translated).(DOCX)

Data Availability

All data presented in the studies were deposited in an appropriate public repository (DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.12962684). URL: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Caffeine_and_Tinnitus_xlsx/12962684.

References

Decision Letter 0

31 Dec 2020

PONE-D-20-30851

The effect of caffeine on tinnitus: Randomized triple-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial

PLOS ONE

Dear Dr. Bahmad,

Thank you for submitting your manuscript to PLOS ONE. After careful consideration, we feel that it has merit but does not fully meet PLOS ONE’s publication criteria as it currently stands. Therefore, we invite you to submit a revised version of the manuscript that addresses the points raised during the review process.

Please submit your revised manuscript by Feb 14 2021 11:59PM. If you will need more time than this to complete your revisions, please reply to this message or contact the journal office at gro.solp@enosolp. When you're ready to submit your revision, log on to https://www.editorialmanager.com/pone/ and select the 'Submissions Needing Revision' folder to locate your manuscript file.

Please include the following items when submitting your revised manuscript:

A rebuttal letter that responds to each point raised by the academic editor and reviewer(s). You should upload this letter as a separate file labeled 'Response to Reviewers'.

A marked-up copy of your manuscript that highlights changes made to the original version. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Revised Manuscript with Track Changes'.

An unmarked version of your revised paper without tracked changes. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Manuscript'.

If you would like to make changes to your financial disclosure, please include your updated statement in your cover letter. Guidelines for resubmitting your figure files are available below the reviewer comments at the end of this letter.

If applicable, we recommend that you deposit your laboratory protocols in protocols.io to enhance the reproducibility of your results. Protocols.io assigns your protocol its own identifier (DOI) so that it can be cited independently in the future. For instructions see: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/submission-guidelines#loc-laboratory-protocols

We look forward to receiving your revised manuscript.

Kind regards,

Hong-Liang Zhang, M.D., Ph.D.

Academic Editor

PLOS ONE

Journal Requirements:

When submitting your revision, we need you to address these additional requirements.

1. Please ensure that your manuscript meets PLOS ONE's style requirements, including those for file naming. The PLOS ONE style templates can be found at

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=wjVg/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_main_body.pdf and

2. Please provide references for the THI and VAS questionnaires.

3. In your Methods section, please provide additional information about the participant recruitment method and the demographic details of your participants. Please ensure you have provided sufficient details to replicate the analyses such as descriptions of where participants were recruited and where the research took place.

4.Thank you for submitting your clinical trial to PLOS ONE and for providing the name of the registry and the registration number. The information in the registry entry suggests that your trial was registered after patient recruitment began. PLOS ONE strongly encourages authors to register all trials before recruiting the first participant in a study.

As per the journal’s editorial policy, please include in the Methods section of your paper:

1) your reasons for your delay in registering this study (after enrolment of participants started);

2) confirmation that all related trials are registered by stating: “The authors confirm that all ongoing and related trials for this drug/intervention are registered”.

5. Thank you for including your ethics statement: "This was a randomized, triple blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial approved by the Institutional Research Board (number: 2.031.285) and registered on the national platform for registration of experimental studies - REBEC Platform (RBR-4CRF4D). All data presented in the studies were deposited in an appropriate public repository (DOI: 10.6084 / m9.figshare.12962684).

All participants were informed about the objectives of the study and signed the written informed consent.".

Please amend your current ethics statement to include the full name of the ethics committee/institutional review board(s) that approved your specific study.

Once you have amended this/these statement(s) in the Methods section of the manuscript, please add the same text to the “Ethics Statement” field of the submission form (via “Edit Submission”).

For additional information about PLOS ONE ethical requirements for human subjects research, please refer to http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/submission-guidelines#loc-human-subjects-research.

6. PLOS requires an ORCID iD for the corresponding author in Editorial Manager on papers submitted after December 6th, 2016. Please ensure that you have an ORCID iD and that it is validated in Editorial Manager. To do this, go to ‘Update my Information’ (in the upper left-hand corner of the main menu), and click on the Fetch/Validate link next to the ORCID field. This will take you to the ORCID site and allow you to create a new iD or authenticate a pre-existing iD in Editorial Manager. Please see the following video for instructions on linking an ORCID iD to your Editorial Manager account: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_xcclfuvtxQ

7. Please include a caption for figure 2.

[Note: HTML markup is below. Please do not edit.]

Reviewers' comments:

Reviewer's Responses to Questions

Comments to the Author

1. Is the manuscript technically sound, and do the data support the conclusions?

The manuscript must describe a technically sound piece of scientific research with data that supports the conclusions. Experiments must have been conducted rigorously, with appropriate controls, replication, and sample sizes. The conclusions must be drawn appropriately based on the data presented.

Reviewer #1: No

**********

2. Has the statistical analysis been performed appropriately and rigorously?

Reviewer #1: I Don't Know

**********

3. Have the authors made all data underlying the findings in their manuscript fully available?

The PLOS Data policy requires authors to make all data underlying the findings described in their manuscript fully available without restriction, with rare exception (please refer to the Data Availability Statement in the manuscript PDF file). The data should be provided as part of the manuscript or its supporting information, or deposited to a public repository. For example, in addition to summary statistics, the data points behind means, medians and variance measures should be available. If there are restrictions on publicly sharing data—e.g. participant privacy or use of data from a third party—those must be specified.

Reviewer #1: Yes

**********

4. Is the manuscript presented in an intelligible fashion and written in standard English?

PLOS ONE does not copyedit accepted manuscripts, so the language in submitted articles must be clear, correct, and unambiguous. Any typographical or grammatical errors should be corrected at revision, so please note any specific errors here.

Reviewer #1: Yes

**********

5. Review Comments to the Author

Please use the space provided to explain your answers to the questions above. You may also include additional comments for the author, including concerns about dual publication, research ethics, or publication ethics. (Please upload your review as an attachment if it exceeds 20,000 characters)

Reviewer #1: In this randomized, clinical trial, the authors tested the hypothesis that caffeine can influence tinnitus. Eighty patients with chronic tinnitus were recruited and divided into two groups, one of which received a 300-mg capsule of caffeine, and the other a placebo capsule, after following a caffeine-free diet for 24 hours before testing. Participants completed questionnaires and underwent various assessments before, and one hour following, receipt of the capsule. Tinnitus-related discomfort was assessed using the tinnitus handicap inventory (THI) and the visual analog scale (VAS). Mood was assessed using the Profile of Mood States (POMS), and an electroacoustic evaluation was conducted. Tonal audiometry was performed, and pitch, loudness and minimum level of tinnitus masking were also evaluated.

Although for the most part the authors have done a good job of following the CONSORT guidelines, in some instances, their efforts have not, I feel been sufficient.

Although the authors describe in detail the questionnaires and exams that were administered, it is unclear which of these constitutes the primary outcome on which their sample size calculation was based. This must be clarified. Although it is stated (l.138) that the study is powered for an effect size of 0.5, the authors do not specify to which outcome(s) this applies. In addition to clarifying this information, the authors should justify why this is considered to be a “clinically important” effect.

ll.93-94. Given that the daily amount of caffeine consumption would likely have an impact on the effect of the intervention dose, it would be helpful if the authors were to go into more detail about how they measured this in the participants. As the authors point out, caffeine “is the most commonly consumed psychoactive substance in the world” and is found in many products. Was the questionnaire used to estimate daily caffeine intake previously published and validated? The authors should provide a reference for any materials (surveys, questionnaires, etc.) used to determine caffeine consumption, and perhaps include or summarize the questionnaire in the manuscript. If the authors did not use a validated questionnaire, this should also be discussed and justified.

l.99. Similarly, the authors should provide information as to how the participants were instructed to restrict caffeine consumption for 24 hours preceding the intervention. Were the participants given a list of foods/beverages that they were not to consume?

Given that these constitute important parts of the intervention procedure, they should be described in adequate enough detail to allow replication (CONSORT Item 5).

The trial is very short, with all measurements made on the same day in a short amount of time (with only an hour of time elapsed between ingestion of the capsule and “after” measurements). Could the authors provide some explanation to justify this approach? A brief explanation of the chemical effects of caffeine (e.g., fast-acting? Lasting how long? Peaking at what point?) is warranted here.

Could the authors explain/justify their decision to use a 300mg dose of caffeine? Is this considered a large enough amount to affect habitual consumers of caffeine? What about those who report NO caffeine consumption? It does not appear to have been decided based on the caffeine usage of the participants, nor was the “usual” individual caffeine consumption taken into account in the analysis, although there is a very wide range of use as reported in Table 1.

Medians (Table 1) should be reported with interquartile ranges (IQRs). Ranges are very sensitive to outliers, and do not give an adequate representation of a distribution. IQRs should always be reported instead of, or in addition to, ranges.

Table 2.

• Although the authors describe the tests used for which results are reported here, they do not indicate the range of the possible scores or how these scores are interpreted. This makes their reported results (citing numerical differences) difficult to interpret.

• It is unclear what correlation is being examined. Is it the correlation between estimated daily use prior to the trial?

• It is not clear what is mean by the note for Gender comparison: “calculation of mean (standard deviation) and p-value of the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test.” These values are clearly not normally distributed and should be summarized using medians and IQRs, not means and standard deviations. The authors have appropriately conducted a non-parametric test, while reporting parametric summaries.

l.137. What is the ARE method of sample size calculation? Please provide a reference.

In the Discussion, the authors compare their data and results to a number of other studies. They do not clearly describe, however, why these particular studies are comparable. To say that “the individual characteristics of the sample were similar to those reported in other studies” is not enough; the justification for comparison to these particular studies is needed. Are they also studies of caffeine use and tinnitus? Did they examine interventions of similar dose and duration? The duration of tinnitus is said to be “shorter than previously reported” but does that mean in studies of tinnitus in general? Or in studies of caffeine use in those with tinnitus? It would be helpful if the authors provided enough information about the comparative studies to demonstrate why they should or should not be comparable. E.g., the current study is compared to a study of caffeine abuse (although the participants in the current study are stated to be low consumers) and a study of a month-long reduction of caffeine consumption. These would not appear to be easily comparable to the study reported here.

ll.269-70. Since it is not known why the placebo group improved in THI and VAS scores, the authors should be more cautious in attributing it to “feeling like their tinnitus complaints were being taken seriously.” Similarly, in ll.293-94, the authors state that that the difference observed between the groups “was not clinically significant” (this should be explained) and “can be attributed to the patient’s experience with the exam.” (What does this mean? Perhaps the use of the phrase “might be attributable” would be more cautious here.)

Overall, I found that the discussion section did succeed in logically constructing a story formed by the results of the study. It would benefit from a tighter construction; as it is, it feels like it wanders from one point to another. Some important issues that warrant, but are not given, discussion include the possible differing effects of the caffeine on participants with widely differing caffeine usage, potential difference of effects due to duration of tinnitus, or why such a brief trial would be expected to yield meaningful results. The length and interventions in other trials are not detailed for comparison or justification for the methodology employed here.

The authors point out that a limitation of the study is that they used a measurement (THI) “not meant” for measuring what they purport to measure. Is this a limitation of the study, or of the authors’ design of the study? If they utilized as an outcome measure a scale “not meant for measuring momentary variations in the sensation of tinnitus” and another tool “influenced by repeated measurement,” the use of these less-than-ideal tools should be justified. Did they have no other choices? How can they expect to see results if they use tests that they know cannot adequately detect them?

While the authors are to be commended for conducting a clinical trial largely within the CONSORT guidelines, I feel that a much better job of reporting the justification for their design daecisions, the reasoning behind their methodology and the interpretation of their results compared to other (appropriately chosen) studies ais needed before the study can be published.

**********

6. PLOS authors have the option to publish the peer review history of their article (what does this mean?). If published, this will include your full peer review and any attached files.

If you choose “no”, your identity will remain anonymous but your review may still be made public.

Do you want your identity to be public for this peer review? For information about this choice, including consent withdrawal, please see our Privacy Policy.

Reviewer #1: No

[NOTE: If reviewer comments were submitted as an attachment file, they will be attached to this email and accessible via the submission site. Please log into your account, locate the manuscript record, and check for the action link "View Attachments". If this link does not appear, there are no attachment files.]

While revising your submission, please upload your figure files to the Preflight Analysis and Conversion Engine (PACE) digital diagnostic tool, https://pacev2.apexcovantage.com/. PACE helps ensure that figures meet PLOS requirements. To use PACE, you must first register as a user. Registration is free. Then, login and navigate to the UPLOAD tab, where you will find detailed instructions on how to use the tool. If you encounter any issues or have any questions when using PACE, please email PLOS at gro.solp@serugif. Please note that Supporting Information files do not need this step.

Author response to Decision Letter 0

21 Jan 2021

Response to Reviewers

I would like to thank the considerations made regarding the submitted manuscript. They were taken into account and certainly added quality to the study. Below are the answers to each consideration made.

• The naming of the files has been formatted according to the journal's guidelines

• The recruitment method as well as the recruitment and data collection location was further detailed in the text as requested: Chapter Methods, subtopics "Recruitment" (page 5, lines 89-90) and "Procedures" (page 7, lines 133-134)

• I would like to apologize for the mistake in the article. There was an error writing the foreign language. Registration was made on the REBEC platform in March, being accepted in July. Recruitment started shortly after being "accepted" in July (not in June as previously described in the article): Chapter Methods, subtopics "Recruitment" (page 5, line 91)

• The requested declaration “The authors confirm that all ongoing and related trials for this drug / intervention are registered” has been added in the chapter "Methods" subtopic "Study design, approvals, Registration and Patient Consents" (page 4, line 78-79).

• The full name of the institutional review board has been added in the "Methods" subsection "Study design, approvals, Registration and Patient Consents" chapter (page 4, line 75), as well as in the submission form

• The corresponding author's ORCID ID was added in Editorial Manager

• The caption for figure 2 has been included: page 9, line 195

• Sample size calculation: The description of the sample size calculation has been reformulated in order to make it clearer (Chapter “Methods” subtopic “Statistical analysis”, page 9, lines 174-178).

o For the sample calculation, the THI results were considered as the primary outcome

o The sample size considering that non-parametric tests were used was determined by multiplying the sample size calculated for parmetric tests by a correction factor. This correction factor is ARE (Asymptotic Relative Efficiency), described by Pitman. To calculate the sample size, α equal to 0.05 was used, test power (1-β) equal to 0.8, effect equal to 0.5, using the conservative ARE minimum method. The ARE method reference was: Lehmannn, EL. Nonparametrics: Statistical methods based on ranks. San Francisco, CA: Holden-Day, 1975; Pitaman, E.J.G, (1948), Lecture notes on nonparametric statistical inference, Columbia University.

• The description of the calculation of the amount of habitual consumption of caffeine has been included, as well as its reference: Chapter “Methods” subtopic “Questionnaires and exams”, page 7, lines 137-141 and reference [20].

• The description of how the participants were instructed to restrict caffeine consumption for 24 hours preceding the intervention has been included: Chapter “Methods” subtopic “Procedures”, page 6/7, lines 128-130.

• The subtopic "The active ingredient" was added in chapter “Methods” in order to explain the choice of measures 1 hour after caffeine consumption based on its chemical effects (page 5/6, line 107-111) and the choice of 300mg dose (page 6, line 112-118).

• Table 1:

o Range values have been replaced by IQRs (page 10)

• Table 2:

o In order to allow the correct interpretation of the values presented in "Table 2", the description of the tests used (THI and VAS) was added in the chapter "Methods", sub item "Questionnaires and exams" (page 7, lines 143-144), as well as their references [25,26]

o The title of the table has been adjusted to show that it represents the correlation between caffeine consumption in the usual diet and the characteristics described in the same table (page 11)

o An error occurred in the formatting and layout of the "*" signs. They were reorganized and presented median and interquartile ranges (pages 11/12)

• The "Discussion" chapter has been revised to make it more compact and cohesive in order not to wander from one point to another (pages 14-18). Because of this, a revision of the "Introduction" chapter was necessary (page 3)

o Page 14, lines 276-280: The first paragraph of the discussion was structured in order to verify whether our sample was similar to the profile of patients with tinnitus reported in studies conducted in this population previously regarding sex, age, duration and location of tinnitus and discomfort in relation to it (calculated with the same instrument used in this study).

o The studies to which ours was compared were better described, as proposed, in order to make this comparison clearer: page 16, lines 306-312 and 321-323. A comparison was made between the values found in the VAS in our study with the values found in the only two studies that investigated the relationship between caffeine and tinnitus and that used the same instrument. One of these studies was cross-sectional and retrospectively investigated in 107 individuals whether there was a relationship between the discomfort with tinnitus (assessed by VAS) and the consumption of caffeine in the usual diet. This relationship is not observed. The other study assessed the influence of long-term caffeine reduction on VAS results. Our study was compared to previous studies that presented the pitch and loudness of tinnitus in a sample of adult individuals, without, however, relating these measures to caffeine consumption. These studies were chosen as the studies that linked caffeine to tinnitus showed no such measures

o Some inferences have been restructured to make them more cautious, as recommended: page 16, lines 316-317; page 17, lines 336/339

o Observations on the limitations of the study were added in order to justify the choice of the procedures cited for the study methodology: page 18, lines 351-353

Attachment

Submitted filename: Response to Reviewers.docx

Decision Letter 1

10 Mar 2021

PONE-D-20-30851R1

The effect of caffeine on tinnitus: Randomized triple-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial

PLOS ONE

Dear Dr. Bahmad,

Thank you for submitting your manuscript to PLOS ONE. After careful consideration, we feel that it has merit but does not fully meet PLOS ONE’s publication criteria as it currently stands. Therefore, we invite you to submit a revised version of the manuscript that addresses the points raised during the review process.

The author are expected to fully take into account the reviewers' comments and to substantially revise their manuscript.

Please submit your revised manuscript by Apr 09 2021 11:59PM. If you will need more time than this to complete your revisions, please reply to this message or contact the journal office at gro.solp@enosolp. When you're ready to submit your revision, log on to https://www.editorialmanager.com/pone/ and select the 'Submissions Needing Revision' folder to locate your manuscript file.

Please include the following items when submitting your revised manuscript:

A rebuttal letter that responds to each point raised by the academic editor and reviewer(s). You should upload this letter as a separate file labeled 'Response to Reviewers'.

A marked-up copy of your manuscript that highlights changes made to the original version. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Revised Manuscript with Track Changes'.

An unmarked version of your revised paper without tracked changes. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Manuscript'.

If you would like to make changes to your financial disclosure, please include your updated statement in your cover letter. Guidelines for resubmitting your figure files are available below the reviewer comments at the end of this letter.

If applicable, we recommend that you deposit your laboratory protocols in protocols.io to enhance the reproducibility of your results. Protocols.io assigns your protocol its own identifier (DOI) so that it can be cited independently in the future. For instructions see: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/submission-guidelines#loc-laboratory-protocols

We look forward to receiving your revised manuscript.

Kind regards,

Hong-Liang Zhang, M.D., Ph.D.

Academic Editor

PLOS ONE

Additional Editor Comments (if provided):

Line 21

Define what the placebo is in the abstract.

Line 26.

24 hours does not seem long as control…? Explain what this is.

Line 27.

VAS here and elsewhere

I think by VAS you mean magnitude estimation. In psychophysics when you are trying to estimate the magnitude of something, it is referred to as Magnitude Estimation. There are several psychophysical procedures that can be used to estimate the magnitude. VAS is one. If one is going to use a VAS scale, it is necessary to state the length of the line, what markings and labels are on the line, and what resolution will be used to convert the subjects marking into a number.

I prefer to have subjects provide a number from 0 to 100.

Line 29

Most readers will not know what acufenometry is.

Line 35

How do you know what is clinically relevant?

Line 48

Several parts of the brain will be involved in the representation of the tinnitus and of the reactions to the tinnitus. Treatments can be focused on reducing the tinnitus (e.g. pills) or on reducing the reactions to the tinnitus (eg. Counseling )

Line 52

The THI actually uses a 3 label category scale. (SS Stevens.. often referred to as the father of human psychophysics)

Please discuss in the results, the sensitivity of the THI has been challenged.

Line 53

VAS

I think by VAS you mean magnitude estimation. In psychophysics when you are trying to estimate the magnitude of something, it is referred to as Magnitude Estimation. There are several psychophysical procedures that can be used to estimate the magnitude. VAS is one. If one is going to use a VAS scale, it is necessary to state the length of the line, what markings and labels are on the line, and what resolution will be used to convert the subjects marking into a number.

I prefer to have subjects provide a number from 0 to 100.

Line 60

Measuring tinnitus

The dB sensation level is not a direct measure of loudness.

They highlighted 4 reasons for measuring tinnitus.

1. Confirm to the patient that their tinnitus is real

2. Monitor changes

3. Provide insights into mechanisms

4. Aid in the fitting of some devices

Line 132

Define the duration of the phases.

Line 140

Mate ??

Line 154

Define the protocols so that some can replicate your study, a fundamental of science.

Line 197

Not clear what the 6 month period stands for.

Line 283

Normal hearing..

State how you define this

Normal pure tone thresholds (=< 25 dBHL)

317. changes over time

Line 320

300 Hz. Are you sure??

Please cite Pan et al., whose pitch matching data suggests that most patients do not have a pitch match frequency just below the maximum hearing threshold loss frequency. The argues against the brain reorganization model in most subgroups of tinnitus.

Line 327

dB is not a scale of loudness

Tinnitus sensation level is not a measure of loudness. You might want to consider referencing:

Line 352

[Note: HTML markup is below. Please do not edit.]

Reviewers' comments:

Reviewer's Responses to Questions

Comments to the Author

1. If the authors have adequately addressed your comments raised in a previous round of review and you feel that this manuscript is now acceptable for publication, you may indicate that here to bypass the “Comments to the Author” section, enter your conflict of interest statement in the “Confidential to Editor” section, and submit your "Accept" recommendation.

Reviewer #1: (No Response)

Reviewer #2: (No Response)

**********

2. Is the manuscript technically sound, and do the data support the conclusions?

The manuscript must describe a technically sound piece of scientific research with data that supports the conclusions. Experiments must have been conducted rigorously, with appropriate controls, replication, and sample sizes. The conclusions must be drawn appropriately based on the data presented.

Reviewer #1: Partly

Reviewer #2: Yes

**********

3. Has the statistical analysis been performed appropriately and rigorously?

Reviewer #1: No

Reviewer #2: Yes

**********

4. Have the authors made all data underlying the findings in their manuscript fully available?

The PLOS Data policy requires authors to make all data underlying the findings described in their manuscript fully available without restriction, with rare exception (please refer to the Data Availability Statement in the manuscript PDF file). The data should be provided as part of the manuscript or its supporting information, or deposited to a public repository. For example, in addition to summary statistics, the data points behind means, medians and variance measures should be available. If there are restrictions on publicly sharing data—e.g. participant privacy or use of data from a third party—those must be specified.

Reviewer #1: Yes

Reviewer #2: Yes

**********

5. Is the manuscript presented in an intelligible fashion and written in standard English?

PLOS ONE does not copyedit accepted manuscripts, so the language in submitted articles must be clear, correct, and unambiguous. Any typographical or grammatical errors should be corrected at revision, so please note any specific errors here.

Reviewer #1: No

Reviewer #2: Yes

**********

6. Review Comments to the Author

Please use the space provided to explain your answers to the questions above. You may also include additional comments for the author, including concerns about dual publication, research ethics, or publication ethics. (Please upload your review as an attachment if it exceeds 20,000 characters)

Reviewer #1: Although the authors have improved the paper in response to prior comments, I still feel that a number of points remain to be clarified, as noted below. My primary concern, however, is that all comparisons are made within the two groups (caffeine and placebo) individually, and it does not appear that the two groups were ever compared to one another. In order to determine whether caffeine indeed has an effect, changes in the caffeine group need to be compared head-to-head to changes in the placebo group (before and after intervention). The within group changes are primarily important in terms of their comparison across the two intervention groups (i.e., is there a difference of differences?).

Other comments:

The authors imply in the introduction that the THI is used in the diagnosis of tinnitus; in ll.143-44 they report that the THI has 25 questions with a total score ranging from 0 to 100. However, it is not clear how the scores are interpreted or what constitutes a “change." Are varying degrees of tinnitus defined/categorized from the continuous score? If not, how is the continuous score interpreted, and what constitutes a meaningful change in score? The authors state that the sample size was based on a change of 3 points. This seems like a very small change, and could refer to either a change within severity category, or a change from one severity category to another (if the continuous scores are indeed categorized into severity levels). Could the authors please give more information on this questionnaire, and the interpretation of the scores? This information would be important if the trial were to be replicated.

Could the authors provide more information about the POMS? It appears to be testing different domains; is there an overall score in addition to the individual domain scores?

l. 68: “the influence of caffeine on tinnitus-related discomfort”: the authors should state their hypothesis clearly rather than imply it (e.g., we hypothesize that caffeine use will increase/decrease tinnitus-related discomfort).

ll.82-83: Could the authors be more specific about the eligibility criteria? Clearly the study required not just that individuals “have tinnitus” but that they had experienced it for some length of time and at some level of severity/chronicity. These requirements should be clearly stated.

l.219: What is “TMD” an abbreviation for?

ll. 219-23: I am assuming the numbers reported in parentheses are p-values. To be clear, please report as (p<0.001) rather than (<0.001).

ll.221-23: Were the values in the states of tension-anxiety and mental confusion-perplexity between phase 3 higher or lower than those in phase 1?

ll. 226-27: Are 36 and 33 the medians for the two groups at phase 3 or the median changes from phase 1 to phase 3? Please give IQRs when reporting medians.

ll.229-30: Same question with respect to the VAS. Are these medians or median changes? Please report IQRs.

Table 2 p-values. I believe that the majority of these p-values were derived using Spearman’s Correlation Coefficients (and not the Mann-Whitney test, with the exception of Gender).

I don’t feel that the question of how varying levels of “regular” caffeine consumption might affect the outcome of the study has been addressed, although the authors have added information about the level of the dosage and the effects of caffeine as related to time. Just reporting these levels doesn’t take them into account in the analysis.

I still feel that both the Introduction and Discussion sections need work. Their organization is awkward, and the ideas don't flow easily or logically throughout. I feel that much of the information is there, but it is not well presented or coherently organized. Could the authors perhaps find someone to help them with the actual writing of the manuscript? I feel that while there is interesting information here, it just is not presented well.

Reviewer #2:

Line 21

Define what the placebo is in the abstract.

Line 26.

24 hours does not seem long as control…? Explain what this is.

Line 27.

VAS here and elsewhere

I think by VAS you mean magnitude estimation. In psychophysics when you are trying to estimate the magnitude of something, it is referred to as Magnitude Estimation. There are several psychophysical procedures that can be used to estimate the magnitude. VAS is one. If one is going to use a VAS scale, it is necessary to state the length of the line, what markings and labels are on the line, and what resolution will be used to convert the subjects marking into a number.

I prefer to have subjects provide a number from 0 to 100.

Line 29

Most readers will not know what acufenometry is.

Line 35

How do you know what is clinically relevant?

Line 48

Please cite the Psychological Model, proposed by Tyler, Aran and Dauman (1992), suggested that the overall annoyance of the tinnitus was a result of the 1) tinnitus characteristics and the 2) psychological make up of each individual patient. Several parts of the brain will be involved in the representation of the tinnitus and of the reactions to the tinnitus. Treatments can be focused on reducing the tinnitus (e.g. pills) or on reducing the reactions to the tinnitus (eg. Counseling )

Tyler, R. S., Aran, J-M., & Dauman, R. (1992). Recent advances in tinnitus. Am J Audiol, 1(4): 36-44.

Line 52

The THI actually uses a 3 label category scale. (SS Stevens.. often referred to as the father of human psychophysics)

Please discuss in the results, the sensitivity of the THI has been challenged.

Tyler, R.S., Oleson, J., Noble, W., Coelho, C., Ji, H. (2007). Clinical trials for tinnitus: Study populations, designs, measurement variables, and data analysis. Progress in Brain Research, 166: 499-509.

Line 53

VAS

I think by VAS you mean magnitude estimation. In psychophysics when you are trying to estimate the magnitude of something, it is referred to as Magnitude Estimation. There are several psychophysical procedures that can be used to estimate the magnitude. VAS is one. If one is going to use a VAS scale, it is necessary to state the length of the line, what markings and labels are on the line, and what resolution will be used to convert the subjects marking into a number.

I prefer to have subjects provide a number from 0 to 100.

Line 60

Measuring tinnitus

The dB sensation level is not a direct measure of loudness.

Please reference

Tyler, R. S. & Conrad Armes, D. (1983). The determination of tinnitus loudness considering the effects of recruitment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 26(1): 59 72.

You should also cite:

Tyler, R. S., Haskell, G., Gogle, S., & Gehringer, A. (2008). Establishing a Tinnitus Clinic in Your Practice. Am J Audiol; 17: 25-37.

They highlighted 4 reasons for measuring tinnitus.

1. Confirm to the patient that their tinnitus is real

2. Monitor changes

3. Provide insights into mechanisms

4. Aid in the fitting of some devices

Tyler, R. S. (1985). Psychoacoustical measurement of tinnitus for treatment evaluations. In: E. Myers (Ed.), New Dimensions in Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery (455-458). Amsterdam: Elsevier Publishing Co.

Tyler, R. S. (1992). The psychophysical measurement of tinnitus. In: J-M. Aran & R. Dauman (Eds.), Tinnitus 91 - Proceedings of the Fourth International Tinnitus Seminar (17-26). Amsterdam: Kugler Publications.

Tyler, R. S. (2000). The psychoacoustical measurement of tinnitus. In R.S. Tyler (Ed.), Tinnitus Handbook (149-179). San Diego, CA: Singular Publishing Group.

Tyler, R. S., Oleson, J., Noble, W., Coelho, C., & Ji, H. (2007). Clinical trials for tinnitus: Study populations, designs, measurement variables, and data analysis. Progress in Brain Research, 166: 499-509.

Line 132

Define the duration of the phases.

Line 140

Mate ??

Line 154

Define the protocols so that some can replicate your study, a fundamental of science.

Line 197

Not clear what the 6 month period stands for.

Line 283

Normal hearing..

State how you define this

Normal pure tone thresholds (=< 25 dBHL)

317. changes over time

Please cite Tyler and Baker, who first documented the wide range of problems experienced by tinnitus sufferers and showed that for most patients, the first 6-9 months is the worst.

Tyler, R.S. and Baker, L.J. (1983). Difficulties experienced by tinnitus sufferers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 48(2): 150 154.

Line 320

300 Hz. Are you sure??

Please cite Pan et al., whose pitch matching data suggests that most patients do not have a pitch match frequency just below the maximum hearing threshold loss frequency. The argues against the brain reorganization model in most subgroups of tinnitus.

Pan, T., Tyler, R. S., Ji, H., Coelho, C., Gehringer, A., & Gogel, S. (2009). The relationship between tinnitus pitch and the audiogram. Int J Audiol. 48 (4): 277-294.

Line 327

dB is not a scale of loudness

Tinnitus sensation level is not a measure of loudness. You might want to consider referencing:

Tyler, R. S. & Conrad Armes, D. (1983). The determination of tinnitus loudness considering the effects of recruitment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 26(1): 59 72.

Line 352

Please cite (Tyler et al., 2014) who focused on the four primary reactions to tinnitus, emotions, hearing, sleep and concentration. This has been used to measure tinnitus changing daily.

Tyler, R., Ji, H., Perreau, H., Witt, S., Noble, W., & Coelho, C. (2014). Development and validation of the Tinnitus Primary Function Questionnaire. American Journal of Audiology, 23, 260–272.

I hope you find my comments helpful.

I would be happy to send reprints if needed.

Rich Tyler

The University of Iowa

**********

7. PLOS authors have the option to publish the peer review history of their article (what does this mean?). If published, this will include your full peer review and any attached files.

If you choose “no”, your identity will remain anonymous but your review may still be made public.

Do you want your identity to be public for this peer review? For information about this choice, including consent withdrawal, please see our Privacy Policy.

Reviewer #1: No

Reviewer #2: No

[NOTE: If reviewer comments were submitted as an attachment file, they will be attached to this email and accessible via the submission site. Please log into your account, locate the manuscript record, and check for the action link "View Attachments". If this link does not appear, there are no attachment files.]

While revising your submission, please upload your figure files to the Preflight Analysis and Conversion Engine (PACE) digital diagnostic tool, https://pacev2.apexcovantage.com/. PACE helps ensure that figures meet PLOS requirements. To use PACE, you must first register as a user. Registration is free. Then, login and navigate to the UPLOAD tab, where you will find detailed instructions on how to use the tool. If you encounter any issues or have any questions when using PACE, please email PLOS at gro.solp@serugif. Please note that Supporting Information files do not need this step.

Author response to Decision Letter 1

7 Apr 2021

• Response to Reviewers

More like once again to thank the excellent contributions made about our study. All of them have been taken into account. An additional statistic was performed in order to meet the requests and special attention was given to the writing of the manuscript. Below are the answers to each consideration made.

Reviewer 1:

• The comparison was conducted among groups (difference of the differences) through the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. This analysis has been added in the "Results", pages 13-16, lines 252-255, 2-271-275, 295-299; and in Appendix 2.

• THI was best described in terms of composition and analysis in "Methods" ("Questionnaires and exams"), page 7, lines 147-154. This questionnaire was subdivided into three scales - Emotional, Functional and Catastrophic - (Newman et al., 1996), however, a study carried out seeking to analyze the factor structure demonstrated that the THI total score can serve as a robust measure of tinnitus distress and recommended using only the total score both in research and in clinical practice (Baguley; Andreson, 2003). Thus, the authors decided to perform the analysis of the total score without presenting the values by sub-scale. The classification of degrees of tinnitus has been added (Newman et al., 1996): “Results”, Table 1, page 11. As suggested by one of the reviewers, the analysis of the items corresponding to the "lack of control" (questions 8 and 19 of the THI) was added since this represents the areas which may produce the most dramatic effects if changes are observed: “Results”, page 13, lines 244-248

• The POMS questionnaire was described for composition and analysis in “Methods" ("Questionnaires and exams"), page 8, lines 156-162. The meaning for the abbreviation "TMD" has been added.

• Added a clear description of the study hypothesis: "Introduction", page 04, lines 71-72

• The eligibility criteria were best described: “Methods”, page 5, lines 85-86

• Specification was provided that the value in parentheses referred to the p-value: "Results", page 13, lines 234-239

• Added the description that the values in phase 3 were lower than in phase 1: "Results", page 13, line 239

• The IQR for THI and VAS has been added: "Results”, page 13, line 243 and page 14, lines 250-251

• The test legend used in Table 2 was adjusted: chapter "Results", page 13/14, line 229

• An analysis of the correlation between caffeine consumption and the variables analyzed in the study was added: pages 13-16, lines 252-255, 2-271-275, 295-299; and in Appendix 2.

• Article writing was revised trying to let it more cohesive and clear

Reviewer 2:

• The description of the placebo was added in the abstract, page 2, line 25

• The choice of a restricted caffeine diet for 24 hours before the study was based on the pharmacology of the substance (presented in the chapter "Methods", page 6, lines 109-114 and in previous studies that sought to investigate the action of caffeine (Hughes, 1991)

• A more detailed explanation of the Visual Analog scale (VAS) has been added: "Methods" ("Questionnaires and exams"), page 8, lines 153-154.

• Added the explanation of what is the acufenometry: Abstract, page 2, lines 29-30

• The description of what was considered to be a clinically relevant hearing threshold change was obtained in the chapter "Discussion", page 19, lines 376-379

• Added the Psychological Model of Tinnitus: "Introduction", page 3, lines 45-46